Volume 11, No. 2, Art. 30 – May 2010

Politicizing Precarity, Producing Visual Dialogues on Migration: Transnational Public Spaces in Social Movements

Nicole Doerr

Abstract: In a period characterized by weak public consent over European integration, the purpose of this article is to analyze images created by transnational activists who aim to politicize the social question and migrants' subjectivity in the European Union (EU). I will explore the content of posters and images produced by social movement activists for their local and joint European protest actions, and shared on blogs and homepages. I suspect that the underexplored visual dimension of emerging transnational public spaces created by activists offers a promising field of analysis. My aim is to give an empirical example of how we can study potential "visual dialogues" in transnational public spaces created within social movements. An interesting case for visual analysis is the grassroots network of local activist groups that created a joint "EuroMayday" against precarity and which mobilized protest parades across Europe. I will first discuss the relevance of "visual dialogues" in the EuroMayday protests from the perspective of discursive theories of democracy and social movements studies. Then I discuss activists' transnational sharing of visual images as a potentially innovative cultural practice aimed at politicizing and re-interpreting official imaginaries of citizenship, labor flexibility and free mobility in Europe. I also discuss the limits on emerging transnational "visual dialogues" posed by place-specific visual cultures.

Key words: transnational public spaces; visual analysis; political deliberation; social movements

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. Research Methodology

3. EuroMayday Online Texts and Visual Maps: Politicizing EU Images of Free Mobility

4. Transnational Public Spaces and Potential Visual Dialogues Through Sharing

5. Transnational Publics and Place-Specific Visual Codes

6. Conclusion

Current scholarly and political debates about the democratic deficit of the European Union have argued over whether the EU lacks a "face" for citizens to identify with and a Europe-wide mass media public sphere for them to participate through. It is in this respect that a non-institutional activist network like EuroMayday gains political relevance. In 2005, on the traditional occasion of Labor Day (May 1), hundreds of thousands of citizens and migrants across Europe participated in non-traditional performance street parades and direct actions within a transnational network of local protests for a "free, open and radical Europe." Street parades took place in over 20 cities as far apart as Maribor and Malaga, Berlin and Athens.1) [1]

The organizers of EuroMayday protests are people in their twenties and thirties. Primarily being employees, workers, trainees or students with precarious job and education contracts, EuroMayday participants also include a significant number of undocumented and resident migrants (CURCIO, 2006; PRECARIAS A LA DERIVA, 2004). Originally, EuroMayday was launched as a transnational network by left libertarian Italian protesters who used their contacts in other countries to make the issue of social precarity a topic through which to create a European radical left protest network (MATTONI, 2006; CHOI & MATTONI, Forthcoming). The term precarity is a political concept that has been used by left movements and social scientists in France and Italy since the 1970s/80s (BOURDIEU, 1998; BARBIER, 2008). Precarity, following its definition by EuroMayday organizers, "describes an increasing change of previously guaranteed permanent employment conditions into mainly worse paid, uncertain jobs" (NEILSON & ROSSITER, 2005 quoted by MATTONI, 2006, p.2). With little support from institutional funders such as trade unions and political parties in Italy, local EuroMayday groups decided to spread their claims to other European protesters active in the areas of immigration, and global and social justice (DOERR & MATTONI, Forthcoming). In countries like Germany, EuroMayday mobilizations received a notable media response, though editorials soon re-framed the term "precarity" to distinguish the "precariat" as a self-responsible new underclass of long-term unemployed and migrant youth (FREUDENSCHUSS, Forthcoming). I will work with the term "social precarity" as an activist discourse in the particular network of EuroMayday activists which is in dialogue with scholarly discourses and knowledge production on precarious labor market conditions (ANDALL & PUWAR, 2007). [2]

Young protesters across Europe framed traditional MayDay as a "European" protest event in hundreds of images, maps, and texts shown online on their shared EuroMayday homepage. This is surprising because the activists who created EuroMayday are young people, most of whom are in precarious job situations, while others are migrants or the children of resident migrants—groups previously portrayed as a politically disinterested (DELLA PORTA & CAIANI, 2009). Secondly, the locally-rooted EuroMayday protests are small, resource-poor, groups which nonetheless act as grassroots "imagineers" of European integration who mobilize a wider public to transnational participation (GUIRAUDON, 2001; MONFORTE, 2010). In other words, EuroMayday mobilizations testify to the existence of a process of politicization2) among groups that scholars would not expect to be particularly visible in public deliberation about Europe. For at least these two reasons EuroMayday should attract the attention of European integrationists as well as analysts of public deliberation and democracy in social movements. [3]

The puzzle I want to explore concerns the images and texts that were discussed and exchanged by young people and migrants in the process of founding and engaging in a joint transnational EuroMayday parade network. Unlike right-wing and Eurosceptic platforms (KRIESI, GRANDE & LACHAT, 2008), we shall see that the EuroMayday protesters do not reject the EU, but engage by calling for a "critical Europeanist" political discourse (DELLA PORTA, 2005a). Critical Europeanism, as supported by global justice activists across Europe, describes a political positioning that differs from a Euroscepticist nationalist rejection of a transnational politics in the EU. Critical Europeanism is also distinct and in contest with top-down visions of European integration as neoliberal. What is particularly interesting, and will be discussed below, is that young protesters turned into critical Europeanists when they felt discomfort with the visual images staged in official EU media events which celebrate a distinct kind of citizenship, as related to "flexible" labor mobility in the EU. [4]

One point worth recognizing about EuroMayday protesters is that their public communication platforms on the internet differ from other, more nationally-rooted, and centrally-organized social movement institutions such as the European Social Forum (ESF) (ANDRETTA & REITER, 2009; DOERR, 2008). Relying on smaller material resources than the ESF, EuroMayday brought together only local groups. The mixed composition of EuroMayday participants makes the network a key site for exploring transnationalist practices of deliberation on the issue of citizenship, given that protesters claim social rights for both migrants and EU citizens (SOYSAL, 2001; NANZ, 2006). By making undocumented migrants' claims a key aspect of their mobilization, EuroMayday activists seem to politicize the "closed" character of national citizenship as an "incomplete institution" that needs to respond to new injustices in the context of corporate globalization and labor immigration (SASSEN, 2003). [5]

To analyze the EuroMayday protests as a potential "transnational public space," the theoretical approach proposed in this article builds on a discursive definition of transnational public spaces that connect a multiplicity of local social movement groups on the ground in shared networks constituting various overlapping transnational communication channels (FRASER, 2007). Unlike global corporate media spaces, transnational public spaces created in social movements often communicate over ICT, and in face-to-face meetings outside organized "global civil society" dialogues (DELLA PORTA, 2005b). This understanding of transnational public spaces draws attention to the restrictions on access to discursive participation for those worried by corporate globalization, given multiple structural and linguistic hurdles. Hitherto, research on citizen participation in emerging transnational public spaces has been mainly focused on text-based materials and the analysis of media arenas (DELLA PORTA, 2005a). My point is that visual images created by activists for their transnational public spaces open up a promising field for discursive theories of democracy. Activists may use transnational public spaces to produce novel cultural imaginaries of citizenship beyond the nation state, and do so in communicative practices that involve images as well as text. [6]

Following a discursive theory of transnational publics, I understand visual images as symbolic forms distinct and yet interwoven with other, verbal or written, discursive forms (HABERMAS, 2001, p.11). Visual images (like other discursive forms) may trigger emancipatory processes of communication in interaction with cognitive linguistic communication. In his review of Ernst CASSIRER's theory of symbols, Jürgen HABERMAS calls the communicative potential of visual images their "liberating power," which he assumes to be constrained by—yet also able to change—existing cultural codes in interaction with cognitive linguistic deliberation (HABERMAS, 2001, pp.11, 24-25). In Hannah ARENDT's discussion of "new public space(s)" created in social movements (1958, p.218), we find a reference to the potential dynamic of visual forms that may initiate a political appearance and a shared symbolic language for groups struggling for inclusion in the public realm through "disclosure."3) Philosophers of images in line with this also suggest that visual images may generate the production of new ideas prior to discursive change (BOEHM, 1994). A potential element and trigger of transnational communication and politicization within the EuroMayday network, visual images are a promising subject of analysis. But what exactly is their "actual" communicative potential? Can images "speak"? And what are the cultural constraints on their use by activists for the particular case of transnational communication in social movements? [7]

Since I am interested in EuroMayday as an emerging transnational micro-public, I will explore to what extent distinct visual images were shared and debated in European and local meetings and/or virtual interactions by protesters. I will also consider the potential limits of transnational "visual dialogues" and the sharing of images or texts in the case of EuroMayday, given the importance of place-specific adopters and their cultural frames (STOBAUGH & SNOW, Forthcoming) in denationalized locally grounded protest (SASSEN, 2004). To give an example of how to study visual images in transnational activist discourse, my analysis will explore the basic question of which images and texts were created and shared by EuroMayday activists in order to challenge perceived narrow official conceptions of workers' mobility, citizen rights and flexibility in the EU. [8]

Earlier work by analysts of visual communication and social movements treats images as a trigger for transnational contention in culturally pluralist media publics (MÜLLER & ÖZCAN, 2007; OLESEN, 2005). We know far less, however, about the sharing of images in transnational discursive micro-publics that may institute dialogue among activists across linguistic and geographic borders. It is true that, in previous decades, social movements created visual images to mobilize people in the media and on the streets. Yet today's digital communication technologies offer a novel and potentially relevant pathway for studying how protest movements intervene in transnational political debates on Europeanization and globalization. EuroMayday protesters, for example, created their own online forum for sharing caricatures, posters, and texts. They did this by relying on the experiences of a number of local Mayday participants in Milan, Hamburg and Berlin. As professional graphic designers engaged in struggles against precarious job contracts, these participants knew how to build homepages (MATTONI, 2008). Activists' images on EuroMayday homepages and blogs have been accessed by tens of thousands of protesters. It is worthwhile studying the content of the EuroMayday images shared and the local posters produced, within the context of the multiple boundaries of access to and usage of internet media (COULDRY, 2003). Elsewhere, Alice MATTONI and I have traced media strategies as well as the considerable structural and linguistic constraints on the spreading of the EuroMayday network from Italy to Central and Northern Europe (DOERR & MATTONI, Forthcoming; DOERR 2008). Here, I will deepen this analysis in order to explore the cultural content and the social context of the production of EuroMayday images and texts by local groups of activists in Germany and Italy between 2005-2009. By means of comparing activists' visual statements in public discourse to official images spread by policy-makers, my analysis will show how single official EU media events may inspire activists' creation and distribution of alternative political texts and posters. [9]

After having introduced my methodology, I will go on to discuss activists' discourse, including visual online maps on EuroMayday blogs which re-interpret official maps of the EU. I then show how a sharing of distinct visual images on EuroMayday homepages and in joint meetings has led to transnational deliberation, convergence and discursive innovation at the local level. Prior to concluding, I outline how persistent place specific visual cultures and discursive codes in local movement groups act to translate images and texts shared transnationally. [10]

Writing about transnational public spaces from a discursive perspective, I am particularly interested in the relationship between images and discourse. I want to explore the potential dynamic of visual images to trigger cognitive linguistic deliberation (and new cultural meanings) through transnational interaction between people. Unlike most other discourse analysts, this research interest required me to include visual methods in my analysis of texts, group discussions and interviews. Analysts of collective action may rely on a multiplicity of visual methodologies to study the cultural meaning of ideas processed in "multi-modal" visual and discursive forms of communication and media strategies of protest (MITCHELL, 1994; CLIFFORDS, 2005; DOERR & TEUNE, Forthcoming; FAHLENBRACH, 2002; TEUNE, 2010). To explore the symbolic content and discursive meaning of visual images shared and discussed within the EuroMayday network, I will here combine visual content analysis, iconography, and the analysis of discourse, ethnography and interviews. This follows an interdisciplinary framework derived from visual sociology (ROSE, 2007) and Critical Discourse Analysis (WODAK, 2006). [11]

In the first stage of the analysis, I applied visual iconography as a method through which to explore the complex aesthetic messages and possible misunderstandings within visual images disseminated in multicultural transnational public spheres (MÜLLER & ÖZCAN, 2007). I then analyzed the content of images in the EuroMayday network, looking at motives, color composition and spatial organization, as well as the use of media technologies. I thus undertook a contextualized interpretation (ROSE, 2007) of the genres of the images, placing them within a wider historic context of image traditions, forms and aesthetic backgrounds. I also analyzed activists' text documents on the internet and in calls for action of the main homepage of the EuroMayday network comparing them to selected official campaign texts distributed by the European Commission on its Europa-homepage. Departing from images displayed on EuroMayday homepages and blogs, I explored the production (encoding) of distinct images as well their re-interpretation (decoding) in place-specific settings (ROSE, 2007). [12]

In the ethnographic part of my analysis, I worked with participant observation and interviews with activists in local EuroMayday groups in different countries who produced and shared visual images. I was a participant observer in two European and six local small-group meetings, and I attended three mass parades of the EuroMayday network in Berlin, Hamburg and Milan in the years 2005 – 2009. I conducted in total 30 interviews with EuroMayday designers and participants. In the interviews, I questioned EuroMayday activists as creators of visuals and texts on their homepages on the design meaning of the images they created. I expected activists to be motivated by an ideational logic of counter-hegemonic strategies aimed at giving visibility to specific groups (CHESTERS & WELSH, 2007). In combination, these methods help us to contextualize and verify the relevance of assumptions gained by the iconography and content analysis of visuals displayed online on activist homepages. Take, for example, a joint blog serving protesters as a way of connecting different local micro-publics. The analysis of the content of the visual images displayed in these sites, together with ethnography and interviews, allows me to explore which images are put online, shared, discussed, or refuted, (and why), by (which) local activist groups communicating across joint blogs as well as in separate interlinked homepages. [13]

3. EuroMayday Online Texts and Visual Maps: Politicizing EU Images of Free Mobility

In order to understand how activists use their transnational publics to politicize official EU media events and images of EU citizens, it is necessary to start by looking at the visual and cultural policies of the European Union.. Since the 1970s, the European Commission (EC) has introduced a number of cultural policies in order to promote the positive elements of European Union citizenship (SHORE, 2000).4) In 2006, the EC carried out a new media campaign promoting the first European Year of Workers' Mobility. As we shall see, this official campaign by the EC evoked an unproblematic image of cross-nationally traveling loyal Euro-citizens, after the neoliberal model of "free moving urban professionals" (FAVELL, 2008) and flexible citizens of former EC campaigns (SHORE, 2000). Simultaneously with the launching of the European Year of Workers' Mobility in 2006, EuroMayday protesters held an extraordinary cross-European parade with hundreds of thousands of protesters (on May 1st 2006), which had the aim of putting social precarity on the political agenda of activists and politicians in Europe (DOERR & MATTONI, Forthcoming). Part of the motivation of the EuroMayday protesters was their objection to restrictive EU immigration policies. They expressed their distance toward official positions by contrasting their views of border-free movement with official positive images of free mobility in EU media events or policy discourse. EuroMayday activists also saw another problem, which they aimed to address at the European level: the question of social rights. [14]

A first difference to be noted in the comparison with EuroMayday activists' discourse and the EC's campaign is that the Commission's text did not mention the topic of migration, using the notions of citizen mobility or workers' mobility instead. The Commission frames citizenship in the first paragraph in its press release by announcing the launch of the "European Year of Workers' Mobility 2006" as being closely related to neoliberal discourse. Citizens are invited to take notice of the advantages of "increasing globalisation and the flexibility of the European labor market; the advantages of occupational mobility and increasing cross-border transparency of qualifications; and geographic mobility as a tool for competitiveness and job creation" (EUROPEAN COMMISSION, 2006, p.1). On the Commission's Europa-homepage this text invitation is shown together with a logo showing two moving figures, yellow and blue, on a white background, moving what could be bags as well as passports in the EU flag's colors (see Illustration 1).

Illustration 1: Screenshot EU photo download [15]

I discuss the content of the campaign logo in Illustration 1 later in the article. Before doing so, it is important to note that the text of the EC's campaign was ignored in a still largely nationally oriented mainstream media (cf. TRENZ, 2008). What European TV journalists, from Arte for example, surprisingly did report on was the critical actions by EuroMayday protesters.5) Unlike the Commission, EuroMayday protesters made immigration their central topic. Indeed, EuroMayday texts pleaded for "more Europe," but of a distinctive kind. [16]

Comparing the texts by EuroMayday activists, I found several similarities to official visions of the future of European citizenship and labor mobility. Like the European Commission, and yet with a different political vision, the texts posted by young EuroMayday protesters on their homepage promote the right of free movement between member states and thus a core element of union citizenship (BAUBÖCK, 2007). The EuroMayday protesters, however, claim fuller, universalist rights of free movement and social rights for all inhabitants in the EU, including resident migrants and undocumented migrants.6) [17]

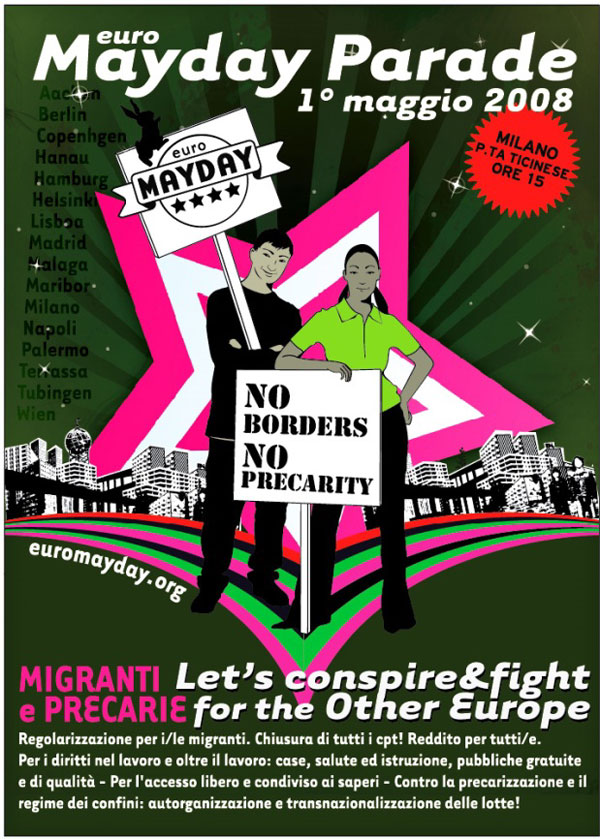

Through participant observation I found that the official EuroMayday texts on the shared homepage were agreed in transnational meetings, several of which I attended. EuroMayday participants also worked out joint calls for action, which were eventually issued on the group's homepage. Early EuroMayday calls in the years 2005 and 2006 constructed the social constituency of Europe not as an EU citizenry but as "the precarious people," described as the precarious people living in the political space of "Euroland."7) An interesting difference is that later calls (from the years 2007 to 2009) make clear that the notion of the "precarious people" includes people across the world in precarious working and living conditions, and not only people in Europe. As will be shown, this distance was in fact the result of internal deliberation and disagreement in the EuroMayday network on the use of a "European" framing of joint protest. Why did that framing change over time? [18]

As a participant observer in transnational meetings, I found that the re-framing of shared texts on homepages were a response to the persistence of disagreements between the plurality of local groups that formed EuroMayday. In the interviews participants explained that after several years of meeting and discussing at the European level, EuroMayday groups had not reached agreement on the usage of the concept of "Europe" in their local campaigns.8) One thing they agreed on, however, was a shared political claim made in 2008, that there should be some form of basic income for all people in Europe, migrants as well as EU citizens. Activists publicized this claim in their joint call issued in different languages on the EuroMayday homepage:

"Migrant workers are the most precarious among the precarious. This is the main claim made by EuroMayDay 2008. […] While our situations are diverse, we are united in the need to find new ways to counter the ever increasing capitalist claims on our lives. […] we ask for unconditional basic income stability, a European living wage, full legalization for migrants, self-organizing and unionizing rights freed from repression, access to culture, knowledge, and skills, the right to cheap housing."9) [19]

Given the difficulties of coming to joint agreements, which I observed in European Mayday meetings, the above call is a highly relevant public statement. The text illustrates the effect of several years of intense deliberation in a transnational micro-public space such as that created within EuroMayday. The text also marks a notable shift from traditional left claims for social rights guaranteed to nationals to claims for fully transnational citizenship and social rights for nationals and non-nationals alike (SOYSAL, 2001; VERTOVEC, 2001). Young EuroMayday activists want more Europe, in contrast with those Eurosceptic left and right wing populist groups mobilizing No-votes in several EU member states (SCHMIDT, 2007). The position of the EuroMayday activists reflects the "critical Europeanist" political ideology of progressive global justice activists in Europe (DELLA PORTA, 2005a). What is remarkable though is that the claims made in this particular text reach beyond those made during the same period by global justice protesters working together in a more classical, deliberative styled, citizen forum such as the European Social Forum.10) For example, the text highlights the daily experiences of labor migrants in post-accession Europe. These groups are called upon to come and stand for a joint activist struggle that includes all people in Europe, labor migrants, denizens, refugees and precarious residents. [20]

Given that activists did not reach agreement on the European dimension (or political identity) for the above call for action, how is it that internal group deliberation led to an agreement on giving migrant workers a central place in that text? Visual analysis is a useful tool to explore this question. Unlike joint texts, activists' shared images on EuroMayday homepages seem to reflect a common theme that is not "Europe" but that re-interprets official EU-symbols from a "critical Europeanist" perspective. Soon after its creation, EuroMayday activists used online spaces to display virtual maps of Europe that symbolically re-interpret the official political frames of Europe as the EU. The use of such "alternative" visual maps of Europe is relevant for discourse analysts of European integration, who have shown that the EU currently holds hegemony over the political framing of Europe as a bordered political space (RISSE, 2003), with a hierarchy of core, candidate and non-European spaces. A first category of visual motives that quotes, responds and re-interprets, official Euro-symbols in a critical Europeanist perspective appears on two EuroMayday online maps created, and used to show the geography of the EuroMayday network in the years 2005 and 2008 (see Illustration 2: for a critical discussion of mapping see: BALL & PETSIMERIS, 2010).

Illustration 2: EuroMayday map on EuroMayday Hamburg homepage [21]

In the map (Illustration 2) produced and put online by the EuroMayday activists no national borders are recognizable, and the EU and its neighboring countries appear as a green land, covered with red dots representing EuroMayday cities. From Huelva and Malaga (Spain) in the south to Maribor (Slovenia) in the east and Jyvaskyla (Finland) in the north, EuroMayday cities are represented by circles, which, together with satellites and a computer, symbolize the network's alternative communication channels via ICT and alternative radio broadcasting. The second interactive map, created by a EuroMayday activist and designer in Milan (Illustration 3), shows Mayday cities that are directly connected to the transnational EuroMayday homepage using ICT.

Illustration 3: EuroMayday interactive online map (designed by Zoe ROMANO, 2008) [22]

Both EuroMayday maps seem to offer an altered visualization of the official European Union "Europe maps" found in schoolbooks and information materials distributed by the European Communities, and in media reporting on EU enlargement in the period studied. See, as an example, the following visual, downloadable on the Commission's Europa homepage (Illustration 4).

Illustration 4: European Commission official map of the European Union [23]

Interviews help to contextualize the visual content and design applied in the above maps produced by Mayday protesters, and their intended political meaning. The first of the two EuroMayday maps above is entitled "Euro First of May Mayday 005" (see Illustration 2). This EuroMayday map highlights the transnational communicative potential, as well as the local and historical grounding, of the public sphere in Europe. Contrasting common-sense representations of the public sphere as national, satellites dishes make visible the possibilities for transnational public discourse on shared social questions such as precarity. In the time-specific discourse context of EU Eastern enlargement, this Mayday map displays visibilities that contrast official, bordered, representations of the EU by a design that relates southern Europe and North Africa by bridging the sea border. [24]

Unlike the official European Union map with its national borderlines shown, the alternative EuroMayday map from 2005 contains visual symbols representing a pluralism of distinct group artifacts and protest characters created by local EuroMayday collectives. For example, on the bottom left hand side of the EuroMayday map there is a small figure designed by Mayday protesters in Malaga and Terrassa ("Nuestra Senora della Precariedad"). "La Nuestra Senora della Precariedad" was one of many "precarious saint figures" used by Mayday protesters to politicize precarity by playing on religious and cultural symbols—inventing "saints" to which precarious people should "pray" and begin political activism where no support by unions or political parties was available (MATTONI & DOERR, 2007). In terms of the political meaning, note that "La Nuestra Senora della Precariedad" in the EuroMayday map from 2005 is positioned geographically in Northern Africa: EuroMayday groups in their texts strongly oppose the EU border policy in Southern Spain, and in 2005 participated in direct actions and no-border camps at the EU-African border area co-organized by Mayday groups in Madrid, Malaga and other Spanish cities. [25]

This mapping reveals the continuing political relevance of a visual styling of protest that re-interprets place-specific historical traditions and popular cultures in an enlarged European dimension of politics (BEREZIN, 2001). It was the southern European Mayday groups in Italy and Spain that introduced Catholic iconography to the transnational public space created within EuroMayday. In the domestic context, the (ironic) message of making Catholic saints heroes of precarious protesters stands for a distancing towards established leftist political actors—unionists who did not listen to the claims of young precarious people (MATTONI, 2006). But, as a visual media distributed over the internet, local precarious saints began to "travel" transnationally. as a visual media. Drawing on situationist and Dadaist precursor movements (SCHOBER, 2009), EuroMayday activists transcended individual isolation with a public ritual of laughter and clelebration. [26]

The EuroMayday map in pink (Illustration 3) was designed by a Mayday activist from Milan for the EuroMayday parade homepage in 2008. The use of the color pink creates a contrast with the official, downloadable EU map for citizens. Its only geographic demarcations are black dots on the pink background. Each black dot is a Mayday city that can be clicked on and accessed through the transnational EuroMayday homepage. Scholars assume that the color pink, used in various global justice protests across the world, stands for "carnivalesque forms of protest" (CHESTERS & WELSH, 2004, p.328). My interviews show that pink has a place-specific political meaning in the case of the EuroMayday online map: Italian EuroMayday founders said that pink stands for queerness as a new radical subjectivity beyond traditional left workers' mobilizations, being inspired by the concept of the multitude by left intellectual Toni NEGRI's writing on Empire.11) [27]

Appealing to the transnational character of the public space within EuroMayday, the use of pink can also be seen as a political symbol to re-appropriate well-known maps of the EU, in which "extra communitarian" countries appear as white or grey, i.e.colorless and on the periphery. Unlike the first EuroMayday map from 2005, the pink EuroMayday map lacks a title and does not use "Europe" as an explicit textual reference frame. My impression, from participant observation and interviews, is that the lack of an explicit text on this map is due to the internal discussion on the geographic scope of EuroMayday. In 2005 and 2006, EuroMayday activists in joint European meetings were controversially discussing whether to use a "European" reference frame in their joint campaign, as some local collectives would have preferred a global reference frame and call the network "MondoMayday." One of the EuroMayday activists from Berlin explained why Berliners preferred a global framing:

"We see Europe as a fortress Europe and therefore we also perceive a notion like "EuroMayday" as a construction of boundaries, of problematic identities, which we reject. We participate as a local struggle within the EuroMayday network, but we certainly don't make it an empathetic thing like some from EuroMayday Milan."12) [28]

Unlike their Italian counterparts, Berlin-based EuroMayday activists saw themselves in clear opposition to the perceived "empathetic" and imaginary work on European politics by Milanese Mayday activists.13) The Italian founders of the Mayday network in Milan saw the debate about the group name also as a chance to continue networking beyond Europe:

"The proposal to call [the network] Mondo Mayday came because we started having connections with mayday in Japan and Canada so we were thinking to connect them to the network in a more visible way."14) [29]

In comparison with the visual maps, the above interviews and EuroMayday texts show that Europe was not a consensual, political theme of the Mayday protests. From this perspective, it appears all the more interesting that there is some convergence in visual forms, which I want to explore through a deeper discussion. Despite their continuing disagreements, EuroMayday groups in different countries shared a visual theme in posters and stickers that refer to migration, and to migrants, as potential protagonists of a citizenship and positive solidarity beyond the nation state. As I have shown, migrants are also the reference group that appears in joint calls for collective action in later years. Intrigued by this puzzle, I will in the following part explore the relationship between transnational "visual dialogues," and the discursive emergence of migration as a shared theme and purpose of EuroMayday texts. [30]

4. Transnational Public Spaces and Potential Visual Dialogues Through Sharing

It should be noted that posters found on homepages put online by local Mayday groups in Italy, Germany and other countries are different. Each time they were created and distributed by protesters themselves. They reflect a plurality of different place-specific subjectivities involved in struggles concerning groups such as migrants, artists, young precarious employees, workers, students and/or single mothers. A shared theme of EuroMayday posters, however, is migration. EuroMayday posters visualize migration as an activity of everyday life within Europe's global cities and their peripheries. This contrasts with the passive state of victimhood provided in mainstream media reports of trafficking or illegal immigration. A good example of protesters' alternative images on migration is provided by a poster designed by EuroMayday Milan in 2008. The visual shows two young figures in front of an urban skyline (Illustration 5).

Illustration 5: Milan EuroMayday poster (2008 designed by Zoe ROMANO) [31]

Through interviews, I found that an official press event preceded the production of the above poster—a press event, however, that is no longer part of the visual that we see in Illustration 5. One of the EuroMayday founders from Milan, herself a professional graphic designer, explains why she put together the poster after intense discussion within her group:

"I made this poster based on a photograph we took [in Milan]. The female figure is a migrant, the male figure is a precarious [worker]. This poster stresses migration as a topic, and the struggles for migrants in our own network, as also written in the text. At the beginning, EuroMayday was very much a network on precarity. In 2008 for the first time, migrants participated actively in the process of constructing the EuroMayday parade [in Milan] so we felt they should be protagonists with us on the poster. Then we talked about the Bossi/Fini legislation against migrants, and new racism. What is politically very important is that the poster shows second generation migrants, who are part of our network […]. This poster does not show our foes, it shows us, our group"15) [My emphasis]. [32]

In the above e-mail interview, this designer of the Mayday poster in Milan 2008 makes a very interesting point which helps us to understand the intersections of visual and verbal discourse in transnational publics. She argues that the deliberative process that inspired her group to produce the above poster was both local and transnational, based on a "visual dialogue" as well as (verbal) group discussion in a multilingual network of migrants and left libertarian activist groups. The interview itself constructs a "we" group in reflecting on that process. First, the interviewee explains that the dialogue and participation of migrants entering the local group in Milan led to a change in the visual self-presentation of the Milan EuroMayday network that produced the poster (Illustration 5). The groups' pluralist composition, and its discussions about restrictive immigration laws by the Italian government, inspired a visual "we-group" poster that symbolizes a joint struggle of labor migrants and other activists previously part of EuroMayday Milan. [33]

Second, we learn that there is also a European element in the above poster. Indeed, the poster was inspired by an official EU event with its own visual symbolic. Because activists in Milan disagreed with the symbolism of the official EU event, they created their own poster through a transnational visual sharing of images with other EuroMayday protesters. What had happened was that Mayday organizers, among them the above interviewee from Milan, had planned a Europe-wide demonstration in the German city of Aachen. EuroMayday chose Aachen as the place for their demonstration with the aim of appropriating an official EU event: the Charlemagne Prize reception with a meeting between Angela MERKEL and Nicolas SARKOZY. The event celebrated German Chancellor MERKEL's work in support of European integration at a time when MERKEL, like French President SARKOZY, was pushing for restrictive immigration policies. The Mayday designers were upset about the celebration of MERKEL's achievement for European integration in this context. Interestingly, then, the interviewee said that her own group in Milan had not agreed on using the same poster as their peer group in Aachen but created their own poster (as shown in Illustration 5):

"In 2008 [EuroMayday] Aachen activists announce[d] that Sarkozy would [hand] Merkel the Charlemagne Prize on the first of May [....] We [in Milan] discussed and then decided to call for [a European-wide] participation to go to Aachen to complain about the prize and the idea of Europe symbolized by that prize. A white and Catholic Europe. That's how the Aachen [EuroMayday] poster with Merkel and Sarkozy was produced. In Milan, EuroMayday posters usually have the people participating in protests as protagonists of the iconography, that's why we decided to make another poster in keeping with the same graphical mood."16) [34]

What is important in the above interview is that disagreement seems to trigger dialogue in visual terms as the exchange of images between activist groups who respond to each other while not taking on all of the content previously shown: EuroMayday activists in Milan created their own local poster based on several steps of re-interpretation of official images of European citizen heroes symbolized in the figures of official politicians. As a first step, the EuroMayday group in Aachen took an official EU press event celebrating MERKEL's Charlemagne Prize reception to create a political counter image (see Illustration 6).

Illustration 6: Screenshot: Indymedia report on EuroMayday demonstration at the Charlemagne Prize reception [35]

The screenshot from an Indymedia report (Illustration 6) shows, on the left, a poster for a European-wide Mayday demonstration on the occasion of the Charlemagne Prize ceremony on May 1 2008 in Aachen. This poster re-interprets a photo of Chancellor MERKEL and President SARKOZY. In a further step, on the right, we see another poster also shown on the main EuroMayday homepage, but this time presented in cartoon-style. That latter poster playfully caricatures the two European leaders in the center of the target circle. The "Euro-couple" MERKEL and SARKOZY now feature as a target. Whereas the target circle itself is a familiar symbol used in previous global justice protests (SCHOBER, 2009), MERKEL and SARKOZY are now found surrounded by an assemblage of skylines of Berlin and Paris and small black figures, which stand for rebellious youth in Europe's "burning" metropolises discussed by EuroMayday intellectuals.17) While the poster text literally rejects European leaders, the visual iconography is ambivalent. Its comic character seems to ridicule politicians as potential representative hero characters of political life (JASPER & YOUNG 2006). MERKEL's and SARKOZY's comic characters wear rabbit ears and dress fashionably, the rabbit being a positive symbol standing for the ironically heroic, queer and carnevalesque style used by EuroMayday protesters to symbolize their own groups' subjectivity in other posters. There is a clear difference between the caricature (Illustration 6) and the Milanese Mayday poster shown in Illustration 5. The Aachen poster is a counter-image showing a rejection of leaders, which was again transformed when re-interpreted by the activist group in Milan. As noted by the interviewee, the presence of migrant groups in the local group in Milan led to a replacement of the Aachen poster by a local Milanese poster. [36]

Together, these impressions suggest that dialogue in a transnational public space between activists creates new meanings through visual as well as verbal interactions that re-interpret and transform official representations of Europe and EU citizens. The visual grammar of a single official EU event, and the shared critique of restrictive immigration policies, inspired the Milan group to imagine itself as a protagonist of citizenship in the enlarged Europe. Discomfort with the existing visual representations of European integration inspired the visual dialogue that led the Milanese EuroMayday group to design the poster shown in Illustration 5. The transnational "image" dialogue, involving visual as well as verbal transformations, changed official hero images portraying leaders in an EU press event by means of placing them in a local context showing precarious youth and migrants in Italy and Milan as everyday heroes struggling with precarity in the New Europe. [37]

5. Transnational Publics and Place-Specific Visual Codes

I have discussed how place-specific differences in the style of visual poster cultures within local EuroMayday groups worked as a trigger for "visual dialogues" in the transnational micro-public space created between EuroMayday activists. In order to deepen this perspective, I want to explore the origin of the relevant local visual codes and cultures of protest. I found that the persistence of distinct local visual cultures, in single EuroMayday groups, was the result of place-specific conflictual group discussions as well as residual transnational disagreements. A useful first example with which to demonstrate this is a comparison of the Berlin Mayday posters with those of the EuroMayday parade in Milan. For both groups, migration was a central issue welcomed jointly in transnational meetings, and reflected as a shared theme in local poster iconographies. As discussed in Section 3, however, the Mayday activists in Berlin disagreed with the explicit European framing of the EuroMayday parade proposed by their Italian colleagues from Milan. This is reflected in the style of poster designs. The posters by the Berlin group, for example, include the word "EuroMayday" but only in very small font (Illustration 7).18) In comparison, the Milan poster discussed above (Illustration 5) follows a European framing in its text and in its visual iconography. Berlin designers in interviews said that they had refused to adopt distinct iconographic elements offered for sharing by other local groups to symbolize the joint transnational space within EuroMayday. Berliners named two motives for rejecting the offer of sharing: a place specific visual poster culture, and the rejection of a positive political reference to the concept of Europe by local group leaders. For their street parade in 2006, Berlin-based Mayday members designed three posters showing a young cleaner, a young white androgynous figure crossing a border fence by cutting it, and an elderly man without stable residence fleeing from the police.

Illustration 7: Berlin Mayday poster triology work/migration/city [38]

Like in the poster created by the Milanese EuroMayday group, a figure of a migrant is at the center of the poster trilogy "work/migration/city" (Illustration 7). The border-crosser figure in the center provides a contrast to conventional media icons of undocumented migrants and seems to visualize the subjectivity and agency of migrants, which activists stressed in their group discussions at meetings I attended in Berlin—discussions similar to those in Milan. The Berlin posters show the border-crosser neither as a black and male icon of "boat people" invading "fortress Europe" (FALK, Forthcoming; GILLIGAN & MARLEY, 2010), nor in terms of "victim images" of trafficked female migrants (AUGUSTIN, 2007). [39]

With respect to these similarities, therefore, the content in visual posters in Berlin and Milan provide evidence of different place-specific political ideas and a very selective sharing of common ideas over transnational public debates: in the above trilogy of Berlin Mayday protests in Illustration 7, the migrant as androgynous border crosser is but one subjective figure among a broader assemblage of precarious people, like the young male cleaner figure (left poster in rose), and the evicted or fleeing old resident of a gentrifying city area (right poster in blue). In the poster from Milan (Illustration 5), a young undocumented migrant is part of a symmetric couple with a young Italian precarious worker. Recall that in Milan, it was following group-internal discussions that the local group promoted a shared European framing of its parade and participated in transnational "visual dialogues" with other groups. Berliners, on the contrary, rejected a joint European framing. A Mayday designer from Berlin explained why he had difficulties in sharing distinctive visual graphics produced by other local groups:

"I personally feel that Europe is not attractive as a topic for Mayday posters (in the specific context of Berlin). We as Image Shift do not want our posters to be adverts or to offer simple identifications with catchy images. Also, we would not design posters that simply caricature politicians. We try to design what we call ‘social images’: images that question existing social relationships, images that come to dance, that are able to ‘swing' the relationship between the viewer and the image. In order words, these images gesture towards a dialogue of inclusion in questions and discourses."19) [40]

Other interviewees noted that members of the Berlin group had discussed and agreed with, their designers' view, which supported a decidedly local visual poster culture that distinguishes itself from images that work like commercial adverts.20) Interestingly, the designers of the Mayday posters in Milan (and Hamburg) had a similar professional background as Berliners, but still saw an advertising of their own ideas through visual images as less problematic. A designer from the Milan group justified her poster design in the following terms:

"The photographer [member of EuroMayday Milan group] reproached me as too marketizing […]. But we are a visual society. You have to show yourself. The way you tell yourself is as important as what you do. If you do not communicate yourself, you stay in the shadow."21) [41]

These comparative impressions reveal the need to further explore the group discussions that led to the establishment of place-specific visual codes in interaction. A more surprising finding is that local visual cultures restrict transnational sharing in situations other than those concerning contested political concepts (such as Europe). Local visual codes, established in group decisions, also seem to constrain the sharing of images of consent topics agreed in principle by all local EuroMayday groups, including that of gender equality. [42]

Gender equality was an important political theme supported by all local EuroMayday groups (see, for example, PRECARIAS A LA DERIVA, 2004). Place-specific discussion processes, however, led to the establishment of very distinct visual codes on gender in posters, which could also act to restrict the sharing of images created by other local groups. The Milan group, for example, produced a sticker album with 20 "super heroes of precarity," many of which were created to visualize representations of gender beyond heteronormative cultural codes (MATTONI & DOERR, 2007). What is interesting is that other EuroMayday groups in Hamburg, Berlin and Vienna adopted only part of the collection of heroic figures for their own local Mayday parades (see, e.g., ALDOPHS & HAMM, 2008). In order to understand the constraints of transnational visual dialogue, I searched for figures that were not transposed to other local contexts. This led me to an unexpected finding when it comes to the visualization of gender: the figures considered by the sticker book’s creators as the most "cutting edge" in terms of gender emancipation were not accepted in other local contexts. One such example was the figure "Wonder Bra" (see Illustration 8).

Illustration 8: Super heroic figures, created by the Chainworkers in Milan [43]

Shown in the above screenshot, the super hero figure "Wonder Bra" (first designed for the Mayday parade in Milan) found few supporters in Northern German Mayday collectives, despite the fact that they shared other figures with their Italian colleagues. The aesthetic style of a super heroic figure such as "Wonder Bra," symbolizing the struggle of sex workers in Italy, created internal conflict in meetings of local groups in Northern Germany. A possible explanation for the rejection of the figure "Wonder Bra" was that local group discussions on the issue of gender were particularly delicate as some group members sought to avoid hegemonic gender representations they saw reproduced in distinctive visuals. A participant in the Hamburg group said that discussions about each individual poster were highly controversial:

"Our Hamburg Euromayday poster for 2005 was designed by some of our friends […]. We controversially discussed it, some did not like it, arguing that it was too ‘aesthetisizing'. We wanted it to be controversial, to actively […] bring the gender topic in. Actually, the poster also has queer elements: the person it shows is based on two photos, one of a man another of a woman. In Hamburg this poster design was particular and distinct from other [groups'] posters […] the poster attracted people's attention."22) [44]

The above interview reveals that both groups in Hamburg and Milan shared a focus on creating new images of gender and used similar visual techniques such as photo collage. The local groups and their members, however, clearly had varying ideas about what makes a good visualization of gender equality and diversity. The EuroMayday collective in Hamburg, as described by the interviewee, created a poster based on a photo collage. This portrayed people of different genders undertaking different types of precarious jobs, who were collectively symbolized in a multi-color figure including a brush for cleaners, a computer for freelancers, a tray for care-workers, and, although it is difficult to recognize on this illustration, a Caro-bag representing immigration (see Illustration 9).

Illustration 9: Screenshot EuroMayday Hamburg poster on Greek Indymedia report [45]

Interpreting iIllustration 9, interviewees' explained that it shows different precarious subjectivities Hamburgers' aimed at bringing together in a single poster assemblage. Among them are the figures of a cleaner, a care worker, a refugee or migrant, and a creative worker. As with the activists in Milan, the Hamburg group members used their personal experiences as migrants, and their intellectual work, to create the above visual poster. As one member noted:

"When we did the photos for the poster, everyone had their own requirements. The Caro bags stand for immigration and anti-racist struggles. E. constructed a big puppet that wears a dress made out of Caro bags. Those in our group who form part of Kanak Attak23) had the idea […]. Eventually, we also constructed wings for the bags symbolizing a very important concept in Kanak Attak's intellectual struggle, that is, the Autonomy of Migration. This puts the emphasis on the desire and the agency of migrants, there is a moment of strength, not only of victimhood. And so, the bags have grown wings." 24) [46]

The EuroMayday activist said, when referring to plastic bags used by global labor migrants in everyday life, that "the bags have grown wings." The symbol of plastic bags has been quoted by activists and artists to construct discursive authenticity representing contemporary nomadism in globalized societies.25) This is an important statement, not only as it further reflects on symbols that re-interpret dominant media images on migration, citizenship and gender in the EU, but also to point to the self-empowering logic of visual production processes in EuroMayday. In Hamburg second generation migrants who are intellectuals of the Kanak Attac network took a key position in proposing progressive visions of citizenship for the local EuroMayday parade. Where EU brochures were conspicuously silent on migration, activists produced visual representations of Europe's people as precariously migrating agents of social change. [47]

In this article I have explored the dialogical potential of visual images created and shared in the EuroMayday parades. Assuming that EuroMayday created a transnational public space to protest against social precarity and restrictive immigration policies in the EU's flexible economy, I traced the visual content and the discursive context of EuroMayday homepages showing activists' locally produced posters and texts. Combining visual methods with ethnography and discourse analysis, I found that "Europe" was not a converging discursive frame used by all the local EuroMayday groups in Germany and Italy I studied. I found only a few direct visual references to official Euro-symbols in EuroMayday's graphic designs on homepages and blogs, such as a caricature of Angela MERKEL and Nicolas SARKOZY (Illustration 6). What I did find is "visual dialogues" that symbolize the potential appearance of a transnationalist citizenship in Europe. With the aim of depicting official visual of EU politicians as heterosexual and white cultural codes of citizenship, some local Mayday protesters resorted to global popular culture, creating super hero characters that belong to everybody. Others chose androgynous representations in order to express their own and/or migrants' desires concerning subjectivity beyond precarity. Contrasting official visions of flexible labor mobility of EU citizens, EuroMayday protesters imagined themselves as pluralist, and citizens as migrants. These migrants appear as ambivalent figures entangled in potentially "flexible" but ironically precarious everyday relationships; they respond neither to the stereotype of "migrant-heroes" nor to that of trafficked victims. Their ambiguity made Mayday sticker book figures travel to other places, but it also constrained the sharing of distinct images if local groups opposed them. [48]

Discursive theorists of democracy might find it interesting that images allowed groups to develop new ideas on European politics, contributing and widening (cognitive linguistic) deliberation in interaction. In this sense, images may trigger, precede and widen the cultural schemes of political deliberation. When commercial national media audiences remained deaf to their claims, young protesters used their backgrounds and experiences as creative workers, writers, photographers and designers in order to build homepages through which to communicate. Rather than rejecting official symbols of EU citizenship, activists' constructed a visual culture that widens the political meaning of what citizenship in Europe may be today, and express solidarity through an exchange of symbols. Interestingly, the content of images such as those created by EuroMayday, depends on local as well as transnational deliberations nourished by invidual groups' internal diversity. [49]

For cultural analysts of politics and protest, these findings show the potential of distinct visual images to work as a trigger as well as an outcome of public deliberation. Where activist groups created new images of their pluralism and struggle for equality, they also appeal to new imaginaries of citizenship that may precede discursive change. To appear in public as a pluralist subject with distinct claims, activists create cultural forms and actual "costumes" that distinguish themselves from already included social groups (ARENDT, 1958). In trying to speak anew, social movements change the familiar or habits of public language use (POLLETTA, 2008). I tried to show that this dynamic may be initiated by visual forms of political dialogue in interaction with cognitive linguistic ones. For example, a single official EU press event inspired local activists to create their own "counter images." Once created, such place-specific "counter images" engendered a transnational ‘visual dialogue' nourished by activists' internal disagreements on representations of citizenship, migration and precarity in Europe rather than by agreement. It seems that a visual dialogue, similarly to a verbal deliberation, is inspired by differences in political ideas that respond to each other. While previous research has focused on the "struggle" or "war" of visual images in transnational media publics, the potential visual dialogues I found emerged in institutional settings that allow for a culture of sharing across distance. Future research should explore the conditions under which disagreement about visions does not end communication but inspires the creation of new images and discussions about who is able to appear and speak in public. [50]

Acknowledgments

I thank the editors of this special issue, Susan BALL and Chris GILLIGAN, the participants in the workshop "Visualizing Migration in Divided Societies," and the two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments. I thank the activists for their views and visions given in interviews. Special thanks go to Alice MATTONI and to Simon TEUNE, for working together on visual analysis in continuing projects. I thank Amelie KUTTER, Ruth WODAK, and the participants in the workshop on "Contentious Images in European Politics" for comments on how to combine discursive and visual analysis, and to Benjamin DRECHSEL, Marion G. MÜLLER and Esra ÖZCAN for their hints on visual theories. I am grateful to Francesca POLLETTA, Beth GARDNER , Bobby CHEN and David SNOW for their points on images in protest. This research was inspired by a dialogue with visual artist Anna VOSWINCKEL. The research was made possible through a postdoctoral fellowship at the Research College "The Transformative Power of Europe" at FU Berlin. The Research College ist funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG), for further information please consult http://www.transformeurope.eu/.

1) The organizers of the EuroMayday Parade in 2006 counted several hundred thousands of participants, e.g. 30,000 EuroMayday demonstrators in Paris, 30,000 in Barcelona, 120,000 in Milan (DOERR & MATTONI, Forthcoming). <back>

2) We have politicization when non-state actors critically intervene in global or European politics to demand justifications and make claims on behalf of social, economic and political justice (ZÜRN, Forthcoming). <back>

3) ARENDT (1958, p.218) refers to the "sans culotte" as a symbol for a struggle for equal recognition and distinction by "laborers" who previously had no place to speak in public and "imagined" their own "costume" as a way of mutual recognition, and distinction. <back>

4) EU campaigns to promote the positive benefits of citizenship can be viewed on the Europa homepage of the EC. This site includes downloadable materials for citizens and journalists, including information guides, maps of the EU, and yearly campaigns on particular issues. It can be accessed at: http://europa.eu/index_de.htm [Accessed: February 17, 2010]. <back>

5) See, for example, the following report in Arte: http://www.arte.tv/de/20050203/844540,CmC=844938.html [Accessed: May 1, 2010]. <back>

6) Interview with Alex FOTI, November 11, 2008, Milan, Italy. <back>

7) See also Alex FOTI "From Precarity to Unemployment: the Great Recession and EuroMayDay", http://info.interactivist.net/node/12334 [Accessed: August 1, 2009]. <back>

8) See, for example, interviews with Alex FOTI, November 11, 2008, Milan; personal correspondence with Frank JOHN, November 2008. Interview with an organizer of the Berlin Mayday, Milan, February 2006. <back>

9) EuroMayDay webpage available at: http://euromayday.org/ [Accessed: August 1, 2009]. <back>

10) For more on discourse, decision-making and conceptions of Europe and European identity in the European Social Forum process and its European assemblies, see DOERR (2010). <back>

11) Interview with Alex FOTI, February 18, 2006. <back>

12) Interview with a Mayday organizer, April 22, 2009, Berlin. <back>

13) Fieldnotes EuroMayday meetings November 2005, Hamburg; February 2006, Milan. See also the interview with Sandy KALTENBORN, February 2, 2010, Berlin. <back>

14) E-mail interview, Zoe ROMANO, September 6, 2009. <back>

15) Interview with Zoe ROMANO, November 6, 2008, Milan. <back>

16) E-mail interview with Zoe ROMANO, September 6, 2009. <back>

17) Interview with Alex FOTI, Milan, February 18, 2006. <back>

18) A copy of the poster trilogy (Illustration 7) is archived online on the homepage of a group from Berlin: http://www.nadir.org/nadir/kampagnen/euromayday-hh/de/2006/04/347.shtml [Accessed: October 1, 2009]. <back>

19) Interview with Sandy KALTENBORN, February 2, 2010, Berlin. <back>

20) Interview with a Mayday organizers, April 4, 2009, interview with a Mayday participant, May 5, 2009, Berlin. <back>

21) Interview with Zoe ROMANO, November 11 2008, Milan. <back>

22) Interview with a participant and with organizers of the Hamburg Mayday parade, November 23, 2005. <back>

23) Kanak Attak is a network of (second generation) young people from migrant families living in Germany. <back>

24) Interview with an organizer of the 2008 Hamburg Mayday event, April 2009, Hamburg. <back>

25) I am grateful to Anna SCHOBER for her hints concerning the role of global fashion and discourse in contemporary protest movements. <back>

Adolphs, Stephan & Hamm, Marion (2008). Prekäre Superhelden: Zur Entwicklung politischer Handlungsmöglichkeiten in postfordistischen Verhältnissen. In Claudio Altenhain, Anja Danilina, Erik Hildebrandt, Stefan Kausch, Annekathrin Müller & Tobias Roscher (Eds.), Von Neuer Unterschicht und Prekariat. Gesellschaftliche Verhältnisse und Kategorien im Umbruch. Kritische Perspektiven auf aktuelle Debatten (pp.165-182). Bielefeld: Transkript.

Andall, Jacqueline & Puwar, Nirmal (2007). Editorial. Feminist Review, 87(1), 1-2.

Andretta, Massimiliano & Reiter, Herbert (2009). Parties, unions and movements. The European left and the ESF. In Donatella della Porta (Ed.), Another Europe: Conceptions and practices of democracy in the European Social Forums (pp.173-203). New York: Routledge.

Arendt, Hannah (1958). The human condition. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

Augustin, Laura (2007). Sex at the margins: Migration, labour markets and the rescue industry London: Zed Books.

Ball, Susan & Petsimeris, Petros (2010). Mapping urban social divisions. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 11(2), Art. 37, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs1002372.

Barbier Jean-Claude (2008). There is more to job quality than "precariousness": A comparative epistemological analysis of the flexibility and security debate in Europe. In Ruud Muffels (Ed.), Flexibility and employment security in Europe (pp.31-50). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Bauböck, Rainer (2007). Why European citizenship? Normative approaches to supranational Union. Theoretical inquiries in law, (8)2, 454-88.

Berezin, Mabel (2001). Emotion and political identity: Mobilizing affection for the polity. In James Jasper, Jeff Goodwin & Francesca Polletta (Eds.), Passionate politics: Emotion and social movements (pp.83-98). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Boehm, Gottfried (1994). Was ist ein Bild? München: Fink.

Bourdieu, Pierre (1998). La precarité est aujord'hui partout. In Pierre Bourdieu, Contre-feux (pp.96-102). Paris: Raisons d'agir.

Chesters, Graeme & Welsh, Ian (2004). Rebel colours: "Framing" in global social movements. Sociological Review, 52(3), 314-335.

Choi, Hae-Lin & Mattoni, Alice (Forthcoming). The contentious field of precarious work In Italy. Political actors, strategies and coalition building. Working USA: The Journal of Labor and Society, 54(13), 2.

Cliffords, Bob (2005). The marketing of rebellion: Insurgents, media, and international activism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Couldry, Nick (2003). Beyond the hall of mirrors? Some theoretical reflections on the global contestation of media power. In Nick Couldry & James Curran (Eds.), Contesting media power: Alternative media in a networked world, (pp.39-56). Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

Curcio, Anna (2006). The new labour actors around Europe: The contentious politics and dealing with the representative political institutions. Conference paper, Alternative Futures and Popular Protest Annual Conference, Manchester Metropolitan University, April 2006.

della Porta, Donatella (2005a). Multiple belongings, tolerant identities, and the construction of "another politics": Between the European Social Forum and the local social fora. In Donatella della Porta & Sidney G. Tarrow (Eds.), Transnational protest and global activism (pp.175-202). Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield.

della Porta, Donatella (2005b). Deliberation in movement: Why and how to study deliberative democracy and social movements. Acta Politica, 40(3), 336-350.

della Porta, Donatella & Caiani, Manuela (2009). Social movements and Europeanisation. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Doerr, Nicole (2008). Deliberative discussion, language, and efficiency in the WSF process. Mobilization, 13(4), 395-410.

Doerr, Nicole (2010). Exploring cosmopolitan and critical Europeanist discourse practices in the European Social Forums. In Simon Teune (Ed.), The transnational condition. Protest dynamics in an entangled Europe (pp.165-182). New York: Berghahn.

Doerr, Nicole & Mattoni, Alice (Forthcoming). Public spaces and alternative media networks in Europe: The case of the Euro Mayday Parade against precarity. In Rolf Werenskjold, Kathrin Fahlenbrach & Erling Sivertsen (Eds.), The revolution will not be televised? Media and protest Movements. New York: Berghahn.

Doerr, Nicole & Teune, Simon (Forthcoming).Visual analysis of social movements. In Kathrin Fahlenbrach, Martin Klimke & Joachim Scharloth (Eds.), The "establishment" responds: Power and protest during and after the Cold War. New York: Berghahn.

European Commission (2006). Information on the European Year of Workers Mobility, http://ec.europa.eu/employment_social/workersmobility2006/index_en.htm [Accessed: April 2, 2007].

Fahlenbrach, Kathrin (2002). Protestinszenierungen. Visuelle Kommunikation und kollektive Identitäten in Neuen Sozialen Bewegungen. Wiesbaden: Westdeutscher Verlag.

Falk, Francesca (Forthcoming). Making visible the invisibility of illegalized migrants. In Benjamin Drechsel & Claus Leggewie (Eds.) United in visual diversity. Images and counter-images of Europe. Innsbruck: Studien Verlag.

Favell, Adrian (2008). Eurostars and Eurocities: Free movement and mobility in an integrating Europe. Oxford: Blackwell.

Fraser, Nancy (2007). Transnationalizing the public sphere: On the legitimacy and efficacy of public opinion in a Post-Westphalian World. Theory, Culture and Society, 24(4), 7-30.

Freudenschuß, Magdalena (Forthcoming). Kein eindeutiges Subjekt. Zur Verknüpfung von Geschlecht, Klasse und Erwerbsstatus in der diskursiven Konstruktion prekärer Subjekte. In Alexandra Manske & Katharina Pühl (Eds.), Prekarisierung zwischen Anomie und Normalisierung. Geschlechtertheoretische Bestimmungsversuche. Münster: Westfälisches Dampfboot.

Gilligan, Chris & Marley, Carol (2010). Migration and divisions: Thoughts on (anti-) narrativity in visual representations of mobile people. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 11(2), Art. 32, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs1002326.

Guiraudon, Virginie (2001). Weak weapons of the weak? Mobilizing around migration at the EU-level. In Douglas R. Imig & Sidney G. Tarrow (Eds.), Contentious Europeans. Protest and politics in an emerging polity (pp.163-183). Lanham, MD: Rowman Littlefield.

Habermas, Jürgen (2001). The liberating power of symbols. Cambridge: Polity.

Jasper, James M. & Young, Michael P. (2006). Political character types: Defining identities in public dramas. Paper presented at the ASA Meetings, New York City, August 2006.

Kriesi, Hanspeter; Grande, Edgar & Lachat, Romain (2008). West European politics in the age of globalization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Mattoni, Alice (2006). Journalists, activists and media activists in the construction of the precarity discourse in Italy. Conference paper, Alternative Futures and Popular Protest Annual Conference, Manchester Metropolitan University, April 2006.

Mattoni, Alice (2008). Organisation, mobilisation and identity: National and transnational grassroots campaigns between face-to-face and computer-mediated-communication. Political campaigning on the Web. In Sigrid Baringhorst, Veronika Kneip & Johanna Niesyto (Eds.), Political campaigning on the Web (pp.201-232). Bielefeld: transcript.

Mattoni, Alice & Doerr, Nicole (2007). Images and gender within the movement against precarity in Italy. Feminist Review, 87(1), 130-135.

Mitchell, William John Thomas (1994). Picture theory: Essays on verbal and visual representation. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Monforte Pierre (2010). Transnational protest against migrants' exclusion: The emergence of new strategies of mobilization at the European Level. In Didier Chabanet & Frédéric Royall (Eds.), Mobilizing against marginalization in Europe (pp.177-197). Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Müller, Marion G. & Özcan, Esra (2007).The political iconography of Muhammad cartoons: Understanding cultural conflict and political action. Politics and Society, 4, 287-291.

Nanz, Patrizia (2006). Europolis. constitutional patriotism beyond the nation state. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Olesen, Thomas (2005). Transnational publics: New spaces of social movement activism and the problem of global long-sightedness. Current Sociology, 53(3), 419-440.

Polletta, Francesca (2008). Culture and social movements. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 619, 1.

Precarias a la deriva (2004). A drift through the circuits of feminized precarious work, RepublicArt.net, http://www.republicart.net/disc/precariat/precarias01_en.htm [Accessed: January 1, 2008].

Risse, Thomas (2003). The Euro between national and European identity. Journal of European Public Policy, 10(4), 487-505.

Rose, Gillian (2007). Visual methodologies. An introduction to the interpretation of visual materials. Los Angeles: Sage.

Sassen, Saskia (2003). Citizenship destabilized. Liberal Education, 89(14), 16-21.

Sassen, Saskia (2004). Local actors in global politics. Current Sociology, 52(4), 649-670.

Schober, Anna (2009). Ironie, Montage, Verfremdung. Ästhetische Taktiken und die politische Gestalt der Demokratie. München: Fink.

Schmidt, Vivien A. (2007). Trapped by their ideas: French elites' discourses of European integration and globalization. Journal of European Public Policy, 14(4), 992-1009.

Shore, Chris (2000). Building Europe: The cultural politics of European integration. London: Routledge.

Soysal, Yasemin (2001). Postnational citizenship: Reconfiguring the familiar terrain. In Kate Nash & Alan Scott (Eds.), The Blackwell companion to political sociology (pp.333-341). Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Stobaugh, James & Snow, David (Forthcoming). Temporality and frame diffusion: The case of the creationist/intelligent design & evolutionary movements from 1925-2005. In Becky Givans, Kenneth Roberts & Sarah Soule (Eds.), Dynamics of diffusion in social movements. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Teune, Simon (2010). Picturing Heiligendamm. Struggles over images in the mobilization against the G8 summit 2007. Paper presented at the workshop The Contentious Face of European Politics: Towards an Analysis of Discursive and Visual Strategies of Transnational Diffusion, Freie Universität Berlin, January 14-16, 2010.

Trenz, Hans-Jörg (2008). Measuring Europeanisation of public communication. The question of standards. European Political Science, 7(3), 273-284.

Vertovec, Steven (2001). Transnationalism and identity. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 27(4), 1 573-582.

Wodak, Ruth (2006). Images in/and news in a globalised world. Introductory thoughts. In Inger Lassen, Jeanne Strunck & Vestergaard, Torben (Eds.), Mediating ideology in text and image (pp.1-18). Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Zürn, Michael (Forthcoming). Politisierung als Konzept der Internationalen Beziehungen. In Michael Zürn & Matthias Ecker-Ehrhardt (Eds.), Die Politisierungs der Weltpolitik. Frankfurt/M.: Suhrkamp.

Nicole DOERR is a Marie Curie postdoctoral fellow at UC Irvine. She holds a Ph.D. of the European University Institute and an M.A. in Political and Social Sciences of the IEP Paris. Her papers appeared in Mobilization, Social Movement Studies, Feminist Review, and the Journal of International Women's Studies. Her theoretical research combines a discursive sociology of democracy and political deliberation with a cultural perspective of transnational relations and public spaces in social movements. Empirically, the author's research interests concentrate on the comparison of face-to-face deliberative democracy experiments and multilingual media practices (with a particular interest in the role of translation, gender and diffusion) in Europe, North America, and South Africa.

Contact:

Nicole Doerr

University of California, Irvine

Department of Sociology

3151 Social Science Plaza

Irvine, CA 92697-5100

USA

E-mail: ndoerr@uci.edu

URL: http://www.polsoz.fu-berlin.de/en/v/transformeurope/team/fellows/Doerr/

Doerr, Nicole (2010). Politicizing Precarity, Producing Visual Dialogues on Migration: Transnational Public Spaces in Social Movements [50 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 11(2), Art. 30, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs1002308.

Revised: 5/2010