Volume 14, No. 1, Art. 6 – January 2013

Situations, Networks and Culture—The Case of a Golden Wedding as an Example for the Production of Local Cultures

Christian Stegbauer

Abstract: The article focuses on the way events are connected with preceding events of the same type carrying out a participatory observation on a golden wedding celebrated in a small village in the middle of Germany. Events are formally connected by their participants. In contrast to participant networks, the chronological order of event-event networks is evident. Different models for the connection of events are discussed with reference to a classic dataset of the "Deep South" study DAVIS, GARDNER and GARDNER (1941). A stability of forms (in the sense of SIMMEL's "formal sociology" [1908]) was found with a variation of some elements. The main reason for the stability is the uncertainty that arises when people temporarily change their position from that of guest to host. They fall back on approved forms for their celebration. Professionals are the other important position. They ensure that events will take place as they did in the past. It is proposed that an analysis of the chronological order of networks between events can lead to a renaissance in the cultural analysis of forms. The analysis presented is an approach to an investigation of the development of culture.

Key words: network research; situations; local cultures; two-mode networks; event-event networks; uncertainty reduction; participatory observation; network dynamics; production and analysis of culture

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. Two-mode Networks and the Interconnection of Events

2.1 Actor-actor networks form actor-event networks

2.2 Event-event networks from actor-event networks

3. Models of the Interconnectedness of Events

4. An Example: Interpretation of a Golden Wedding in the Vogelsberg Mountains (Germany)

5. How Can Uncertainty Be Handled?

5.1 Uncertainty reduction in the position of "host"

5.2 Uncertainty reduction in the position of guests

5.3 The position of innkeeper?

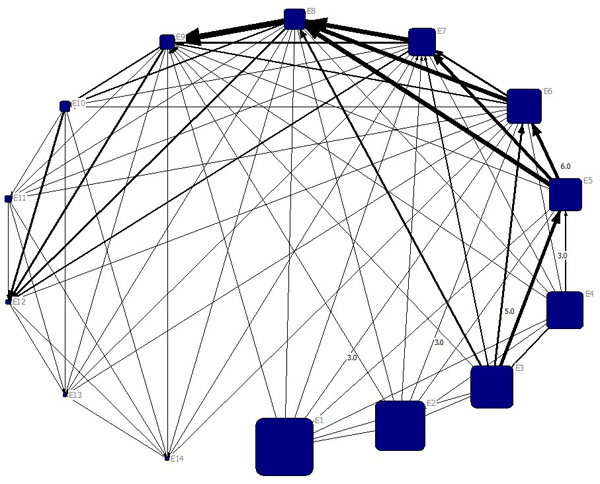

6. Interconnection of Events

7. Conclusions

People celebrate anniversaries, they organize parties, hold celebrations for a wedding and meet each other frequently in different circumstances. The impression is widespread that the way a celebration is held can be predicted. Participants are aware of differences in the variety of these events. They have the impression that events of the same type are very similar. The article presents explanations for the similarity between these events. [1]

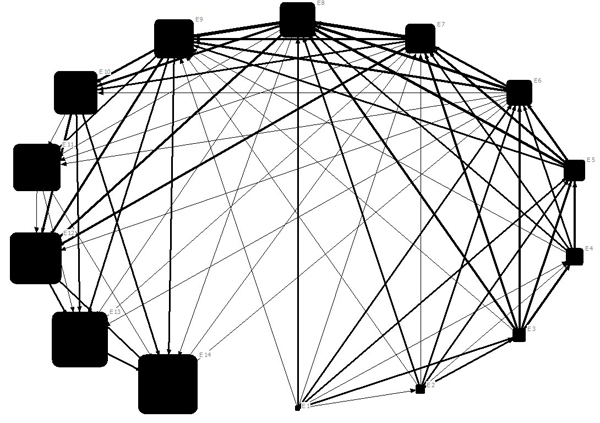

Two different modes of explanation are introduced in the article: First it is asked how events are connected to preceding ones. Different formal models are introduced to explain the way events are connected with others in a time line. Secondly, research on different types of events is presented and the way the connection to their predecessors is socially accomplished. It is argued that uncertainty in all kinds of participants is the most important driving force for adjusting the forms in which an event is carried out and for the behavior of the people involved in this event. [2]

It is shown why uncertainty regarding the organization of events evolves and how people deal with it. In this connection orientation on past events is most important. An event can be broken down into different "form elements," such as the way the reception, the food and the music are celebrated. Some of these elements appear to be stable, others are variable and can be recombined in different ways for a specific event. These form elements, which are part of culture, tie events to former, similar events. Some of these elements are transferred from one event to another by collective memory and by peers who have attended such events before. [3]

It is argued that one crucial reason for the stability of common form elements is uncertainty, which derives from a change in the position from guest to host1). Hosts are former guests and guests sometimes become hosts for some events. This allows them to change the perspective cognitively .Such a change of perspective is described by the label "reciprocity of perspective" (LITT, 1926; SCHÜTZ, 1981; STEGBAUER, 2002). Thus, hosts can imagine how guests will speak about the way an event is organized. [4]

The network theory of Harrison WHITE (1992, 2008) focuses on situations and on the negotiation of positions in such situations. Events in that context can be interpreted as an ensemble of situations. When negotiations about structure and positions are made, people apply parts of the common cultural tool kit (SWIDLER, 1986, 2001). The term culture is always enigmatic. The conceptualization of the term culture in this article is inspired by Ann SWIDLER's idea of the connection between culture on the macro level as common knowledge and the use of this knowledge in situations, which is used for situational negotiations. Cultural tools include habits, skills and styles from which people construct strategies of action (SWIDLER, 1986, p.273). For SWIDLER (1986), culture is a tool on the level of action and at same time a system in which the cultural tools are embedded. Such tools comprise the different elements of which events are composed. These elements can be seen as products of culture. In other words, the investigation of events and their development in networks is nothing but a proposal for the development of methods for an approach to the discussed branch of cultural analysis2). The aim is to combine structural analysis considerations with a qualitative approach towards analyzing both the structure (the network) and the event itself. In this respect it is necessary to combine quantitative analysis with the contexts. This means that qualitative analysis3) also seems necessary for an understanding of the evolution of such cultural tools (see BREIGER, 2000). [5]

The main analysis is based on a participatory observation of a golden wedding celebration (50th wedding anniversary) conducted in 2009. Furthermore, a group of my seminar students carried out 14 semi-structured interviews with attendees and organizers of very different events. The events include: a funeral, golden wedding anniversary, wedding (wedding organizer), Abitur ceremony (German matriculation or university entrance qualification), Jugendweihe (youth consecration), party plan marketing (perfumed candles and costume jewelry), celebration of Father‘s Day on Ascension Day in Germany (which men use as an excuse to get very drunk), the opening of an exhibition, and a 30th birthday party. [6]

The article begins with some thoughts about two-mode networks. When the connection between events is conceived as a chain, they are in touch through the same participants of different events. This is crucial because it is the key to understanding how different traditions for the same type of events can develop over time. In other words, the genesis of cultural traditions is dependent on people who learn these traditions in the context of sequences of events and come back to them when they have to organize events themselves. In the next section, the significance of the interconnection of events is explained. This is followed by a discussion of structural models and the consequences of event-event networks derived from actor-event networks. Subsequently, the case of a specific event, the organization of a golden wedding anniversary, is presented. This leads to a section on how uncertainty is tackled by different positions: i.e. the host, the guests and the professionals. Finally a model combining the qualitative and the structural approach is introduced. [7]

2. Two-mode Networks and the Interconnection of Events

2.1 Actor-actor networks form actor-event networks

From the standpoint of a network researcher, the structure can be reviewed by two-mode networks. Two-mode networks can be analyzed by focusing on the connection of the participants involved or on the interrelation of the events they are based on. Examples of the analysis of two-mode networks are numerous, for instance the entire research on interlocking directorates (LEVINE, 1972; MARIOLIS, 1975; SCHOORMAN, BAZERMAN & ATKIN, 1981; SCOTT, 1991; VEDRES & STARK, 2010) or research on Wikipedia, in which participation in the construction of an article is often used as a type of tie.4) [8]

When considering these two examples, such networks can be constructed if persons are members of more than one corporate board or have worked on more than one article in Wikipedia. Networks conducted in this way are referred to as two-mode networks or actor-event networks. In the case of Wikipedia, articles are interconnected with each other when the same individuals have worked on them. The interconnection between two articles can be measured—the more people have edited the same two articles, the stronger the relationship. In the case of interlocking directorates, two companies are related if one person is a member of both boards. [9]

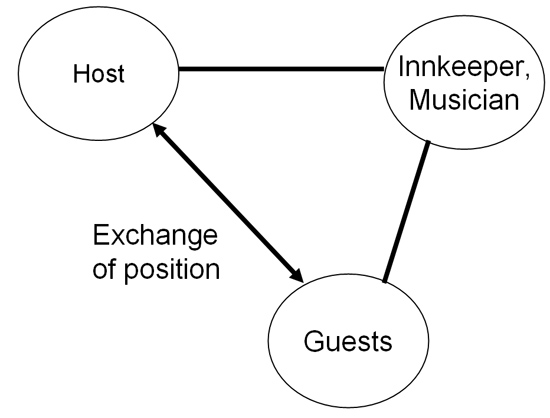

While, in most cases, two-mode networks are interpreted only as actor-actor networks, in this study the connection between events is considered. Some ideas on the cultural analysis of the interconnection of events are introduced here to demonstrate how important it is to go beyond traditional two-mode analysis: it is shown that the number of people who attend two events is not sufficient for an understanding of the similarity of events. Events are composed of different form elements. Form elements are small components of a larger arrangement. They apply to certain functions in this arrangement. Some of the elements have equivalents, which means that they can be interchanged. They can be shaped by specific contents. For example, one of the form elements discussed here is the aperitif that is served to welcome the guests. The element is fixed for a celebration like the golden wedding under study, but what exactly is served can vary. In the region where the golden wedding took place, it will mostly be sparkling wine, Prosecco or a more modern variant of soft drinks. The content of this form element can also vary in respect to the food served, an example being finger food, a starter which can be eaten while standing. These elements can be repeated or recombined when a future event is organized. Events are linked by people who transfer their experience from prior events to more recent ones. [10]

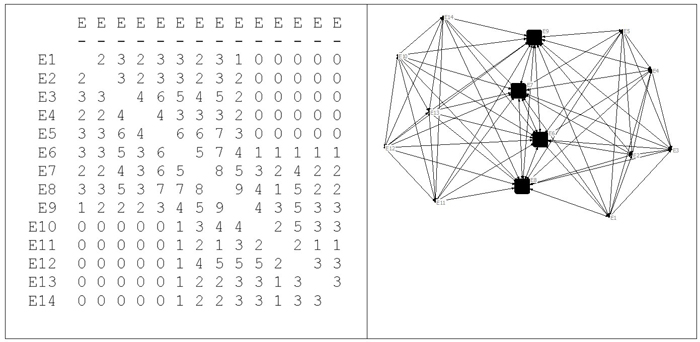

In the field of social network analysis one example is often cited with regard to actor-event networks. It stems from DAVIS, GARDNER and GARDNER's (1941, p.148) "Deep South" study (BORGATTI & HALGIN, 2011; DOREIAN, BATAGELJ & FERLIGOJ, 2004; FREEMAN & WHITE, 1993; FREEMAN, 2003; RAUSCH, 2010). Many attempts have been made to analyze these data. FREEMAN (2003) did meta-research on 21 of these studies. All 21 tried to specify the group structure in a single data set (see also the analysis of FIELD, FRANK, SCHILLER, RIEGLE-CRUMB & MULLER, 2006). DAVIS et al. (1941) collected data on the social activities of 18 women who had met in a series of 14 informal social events. For data collection they used interviews, records of participant observers, guest lists and newspapers. The data were originally used to reveal two cliques. From HOMANS (1950, p.82), who took the DAVIS et al. study as one of his famous examples, we learn that the events were very heterogeneous. They range from work behind the counter of a store, to a women's club meeting, a church supper, a card party, a supper party through to a meeting of a parent-teacher association. In the classic example (Fig.1) the only question asked was: Who shared the event with whom? It was concluded that persons who share more events with each other are more closely connected.

Figure 1: The classics: Two-mode analysis [11]

Nobody in FREEMAN'S meta study (2003) thought about the interconnection of events.5) Normally the connection of participants through attending events is investigated—but in the case discussed later it could be said that events are interconnected by their participants. On scrutinizing this statement, it is necessary to distinguish between different positions and many uncertainties which vary according to the positions. [12]

2.2 Event-event networks from actor-event networks

The interconnection of events is relatively seldom considered in sociology. Some examples can be found in the field of network analysis in bibliometrics (HAVEMANN & SCHARNHORST, 2010), which focuses on the question which journals are a forum for debates in a certain scientific field. The research group headed by the German sociologist Thomas MALSCH was the first to try to model the network of communications in a similar way (HARTIG-PERSCHKE, 2009; ALBRECHT, 2008; MALSCH, 2005). Event-based business networks are investigated by HEDAA and TÖRNROOS (2008), but their definition of the term "event" is different: it just means that something that has happened. By contrast, in this article the term is used in connection with repeated activities and the persons who attend these activities6). Another example of the event-event perspective is the investigation of themes in narrations (CUNNINGHAM, NUGENT & SLODDEN, 2010). The case of their study was the shooting to death of five people in North Carolina in 1979. The authors of the study found out how the content of the narrations vary over time. The relations between events were investigated in a more complex setting by MISCHE and PATTISON (2000). They explained how events, organizations and projects worked together in an impeachment movement against the then Brazilian president. The examples mentioned here apply a dynamic perspective: the first deals with two different periods, the second with three. CORSARO and HEISE (1990) applied a specific approach—they studied prior events which were essential to the current event. When, as in the present case, the routines of a golden wedding anniversary celebration are investigated, most of the persons in the same positions have participated in two other, prior events in the history: first in the row, the wedding as the initial event with the same people in the position as hosts, and secondly their Silver Wedding Anniversary when the couple had been married for 25 years. Hence, the wedding couple has had experience in organizing events of the same class, but with a long time-gap in-between. BEARMAN, FARIS and MOODY (1999) presented an approach to applying network analysis to historical social science. They used multiple narrations to construct networks. [13]

The interconnectedness of events has to do with the sociology of forms. This is an old theme in classical, non-individualistic sociology (represented, for instance, by Georg SIMMEL) and it is becoming increasingly popular in modern relational sociology. In the classic example the events are heterogeneous. It can be assumed that the way people behave is negotiated and transferred (KIESERLING, 1999)7) from one event to the next. By orientating their behavior towards similar situations or different people, uncertainty is reduced. In situations, positions are negotiated as well (WHITE, 1992). Once established, positions among the same participants make them expect that people will behave as in previous situations. Negotiations are dependent on the cultural tool kit (SWIDLER, 1986). In situations people negotiate specific forms (SIMMEL, 1908) which can be transferred to new and different situations like events. For instance, the form (the way) in which people prepare food and take it to a party can be transferred to a charity event. The positions of participants are connected to the delicacies in former situations. Hence, it will be expected that Mr. and Mrs. Xyz will bring the same food as in a similar situation in the past when they were praised for their cooking and asked for the recipe. Heterogeneous events are also interconnected by the fact that they provide an opportunity to plan further events. As Georg SIMMEL (1908) mentioned, individuality is shaped by crosscutting social circles—but social circles are crosscut by people as well. Social circles become visible through events. People who share different events can transfer cultural tools (forms) from one event to the other. In the example presented later in this article the events are more homogeneous. First different models for the interconnection of events are discussed. [14]

3. Models of the Interconnectedness of Events

The first model of three introduced models is the event-event network. This network is constructed by the shared participation of people in different events. The first model is referred to as the "number of participants model" (Fig. 2). The more events the same participants share, the closer is the relationship between the events. The outcome is: events which have more participants in common are more similar than those with fewer. The more people share an experience, the greater the influence on following events. What supports this idea? When we consider events as an ensemble of routines (or form elements), the greater the number of participants, the more people share the experience of the event. In subsequent events they have an opportunity to implement the same elements that they have experienced before. They are familiar with the elements and how they were appraised in the previous situation. [15]

Typically event-event networks are constructed symmetrically, but, as can be seen here, in reality they are not symmetrical. They depend on the direction of time. While persons as entities persist over a longer period (except in mortality, relocation, etc.), events are transient, therefore they can be arranged temporally. Event 1 occurs before Event 2; this means that potential influence has only one direction: it is only possible for a preceding event to influence the succeeding one, not the other way round. As mentioned earlier, the events investigated in the "Deep South" study were heterogeneous. The character of an event can change if there are more participants than usual because the opportunity for negotiations is less than in the case of an event with only few participants. Many parts cannot be negotiated with all the attendees, so the event will be more oriented towards common conventions. Guests at a bigger event will probably behave in accordance with social norms to a lesser extent than in the case of a smaller event. Relatively individually negotiated positions with their relatively unique spectrum of behavior can have a greater influence on succeeding events than conventional ones with many participants. A smaller event with only a few participants reduces the influence of the attendees because they have only a limited range of opportunities to behave in the same manner as on previous occasions. Therefore it is not clear whether events with a small number of attendees or those with a large number of attendees will have more influence on following events.

Fig. 2: Number of participants model: Event-event network data (DAVIS et al., 1941)8) [16]

Two alternative models are shown in the next two figures. The first is referred to as the time-influence model (Fig. 3). In the time-influence model, the most important factor is the first event in a chain of events. The older an event, the potentially greater is the chance of its influencing later events. With every new event, the impact of the older one increases (given the same participants). When we consider how forms (SIMMEL) develop, they are negotiated at the beginning and tend to become stable. More recent sociological network theorists focus on the dynamic character of networks (WHITE, 1992, 2008, PADGETT & ANSELL, 1993; EMIRBAYER & GOODWIN, 1994; PADGETT & POWELL, 2010) as a reaction to the critics of structuralism as a theory that cannot handle historical change.9) [17]

EMIRBAYER and GOODWIN (1994) called the ideas of structuralistic network research "structural determinism." When considering the relation of events in this context, it is clear that there must be a connection: for instance, nobody will invite somebody they do not know. When a person organizes an event he or she has to use elements from former events. This does not imply that the relation is deterministic. Elements from former events have a greater chance of being used in a succeeding event. Such elements or forms are similar to the tools Ann SWIDLER (1986) described as the "cultural tool kit": many people know about them and they can be combined with each other. To say the relation is deterministic would be rather stretching the point. The events are, however, linked together in a direction. When considering the establishment of forms, the first event should be the most important one. One problem with this model is that there is no real beginning10). In the case of the "Southern Women" which is part of the "Deep South" study of DAVIS et al. (1941), the first event is the first the researchers have conducted. In reality the chain of events is much older than the people who attend it and it will probably never end. Moreover there is the problem of possible limits to observation. All the attendees of a chain of events have participated in other events which remain unknown to us.

Fig. 3: Time-influence model: Event-event network11) [18]

In the memory-distance model, the most recent event is the most important one. This model deals with the tendency to forget details over time. When taking into account the memory of the participants, it can be maintained that the longer an event is over, the weaker the memory about it is. This is the converse argument of the time-influence model. Is this really contradictory? It is not: the event (directly) preceding the next one will be most present in the memory. However, some of the forms of the preceding event will have been established over time. They stem from former events and have now maybe become a consensus, which means that no-one will give any thought to their origin12). This seems more like what ZERUBAVEL (1997, p.8), citing Karl MANNHEIM, mentioned. Cognitive sociology or the sociology of knowledge asks how people think. The answer is that the basis of all of their thoughts is what all the others have thought and communicated before. The only possibility is to think further on the basis of what others have thought before. In the case of the time-influence model it is possible that very similar participants and hosts of such events are captured in the form elements others have introduced before. The only freedom they have is to recombine established form elements. Under these circumstances, in most cases new elements can only be introduced with a great deal of caution. This leads to the present considerations about the invention of cultural forms in an analysis of the interconnection of events. Not only the overlapping of guests between events is important, but also cultural form elements which are known in common or in the group in which the event will take place. Older elements stemming from events far in the past (Fig. 3) can be updated in every case in which they are applied. Hence, all the models discussed can be justified to a certain extent. In fact, a combination of the models is desirable.

Fig . 4: Memory-distance model: Event-event network data (DAVIS et al., 1941)—directed13) [19]

As mentioned before, there is little information (neither in DAVIS et al., 1941 nor in HOMANS, 1950) about the types of events in the case of the "Southern Women." In the present investigations into the interconnectedness of events several examples were found of elements which were very old or of some which were invented due to an incident. One element of the main event studied is a menu card found on the internet. The menu featuring different courses stemmed from a wedding in 1909.14) It looks very similar to the menu used for the Golden Wedding Anniversary except that it was handwritten. The main difference to the newer menu is that most of the dishes at that time came from local produce. Mediterranean vegetables, for instance, were not available in those days. Hence this is an element which is transferred from events a long time before the case under study took place. The example of an introduction of a new element stems from an Abitur (German matriculation) ceremony of a high school in Thuringia, Germany. Some years ago, during the ceremony one of the students had hidden backstage with his guitar. After the principal's speech he came out and sang a humorous song about the teachers of the school. The act was not planned officially and the organizer was not amused because the ceremony had been organized by a teacher—and the song was about the idiosyncrasies of some of the teachers, which made it embarrassing for them. In the situation, the teachers had no chance of stopping the performance because the other attendees enjoyed it so much. Nowadays the organizers try to avoid such a situation. Since that time, every year the organizers keep an eye on the backstage to avoid a repetition of the episode. The first element, the menu, is part of the common cultural tool kit—nearly everybody is familiar with menus of this type which inform guests about the meal. The second element, the song of the student, was introduced locally, but all the teachers and all the students of that school and of many others in the city where it happened know about it. Narrations about the incident circulate—they are part of the cultural tool kit in this city only and only for this kind of event. It can be forecast that the incident will be forgotten over time, it will be erased from the common memory. These two examples explain the different modes of operation of all three models introduced. The participants are able to transfer their knowledge to the next similar event (parents, siblings and teachers). The song represents the introduction of a new element. The result is a form of behavior which will probably be repeated as long as the memory of the organizers last. [20]

A further example of the introduction of a new element in a special type of event is the presentation of kids' pictures during a Jugendweihe (youth consecration). One of the organizers of the ceremony hit on the idea of asking the adolescents for pictures from their childhood and projecting them during the ceremony. The organizer got much positive feedback for this new element. Since its invention five years ago, the element has found widespread distribution. We were informed that this element has established itself in this type of event almost throughout Germany. The organizers try to invent new form elements from time to time. If the feedback is not good enough they abandon them and revert to tried-and-tested elements. [21]

The wedding organizer interviewed reported the trend to celebrate weddings at special venues, such as castles. Such cases reveal an element of competition for the most romantic venue. But in this case, only one element is varied and it is done with the aid of a professional. The concept behind it remains untouched: a marriage should be a romantic event and meet the guests' expectations. [22]

The impression is that, in most cases, innovation only arose from the invention of one or very few new elements. Often they are taken from one type of event and are transferred to another, current type of event. [23]

The models discussed here are formalized, but they do not provide information about how and why events are interconnected. We know nothing about the transfer of forms, and why forms are interconnected. We have no information about the importance of the connection between the participants for the shape of the event. Furthermore, we know nothing about how the interconnectedness forms the behavior of the participants. It can be seen that formal explanations imply a lack of cultural content. It will be shown how form elements which are negotiated in a specific culture link events to other events. [24]

Despite all the criticism, the models introduced are not useless. Events are interrelated by their participants. Due to the compromises made between all those involved in a new event, older events with the negotiated traditions are always present. Form elements and content are negotiated in a specific context, therefore this is crucial to understanding the development of a specific culture. Admittedly, it does not explain the underlying processes sufficiently, but it helps to establish a basis for the way people behave in their positions. Hardly any of the participants involved in an event will know anything about the relationships discussed here; however, this affects the behavior of all of them. [25]

4. An Example: Interpretation of a Golden Wedding in the Vogelsberg Mountains (Germany)

The main basis of the argumentation is a participatory observation of a Golden Wedding anniversary. This work is not a network analysis, but it was inspired by considerations about two-mode networks. In this example the hosts had to deal with approximately 60 (invited) guests. The celebration was justified by recourse to previous events: since the hosts had often been invited to similar events (birthdays, wedding anniversaries, etc.), they thought that they had to invite the former hosts to a similar event as a form of reciprocity (STEGBAUER, 2002). An invitation and a return invitation show that one event depends on a former one. The explanation is similar to MAUSS' (1954) "The Gift": Invitations establish a system of "debts" which hold society together, each equalization creating new debts15). [26]

Invitations to friends for dinner at home are relatively common, but the case of celebrating a big event like a golden wedding causes far more problems with regard to organization. These problems come with uncertainty. As Georg SIMMEL (1908, pp.50-51) stated, one aspect of uncertainty is the number of guests and the need of support: compared to an invitation to one or two persons, an invitation to 30 people at the same time radically changes the organization requirements. [27]

The golden wedding was celebrated in a small village in the Vogelsberg Mountains in central Germany. It was held in a village inn, specializing in family celebrations. The celebration involved at least three different positions (Fig. 5), some of which changed over time.

Fig 5: The constellation of influence between positions: Uncertainty triad (arrowheads show the exchange of positions)16) [28]

Normally our network research experience shows that positions tend to consolidate over time. In the present context only the positions of innkeeper and musician were consolidated. These positions can be called external positions because, in general, they would not be members of the (golden-wedding anniversary) party. Internal positions (host and guest) do change from event to event (the host is a guest in most other event situations). Thus, the host position will only be taken once in a few years, sometimes only once in a decade. Most of the attendees were guests. Guests have more experience of their position than the host. The host only changes his position for the short time in which he organizes the event. In the present case, "positions" stands for clusters of formal structurally equivalent participants. In contrast to network analysis (WHITE et al., 1976; WHITE & BREIGER, 1975), positions in this article are derived from the observation of their formal position. [29]

To understand what is going on in the interconnection of events, we can ask why forms are so relevant. One reason for the relevance of forms (like traditions of celebrating an event in a specific way) is uncertainty. Uncertainty is related to control (WHITE, 1992). Control efforts can be seen as universal behavior for the reduction of uncertainty. The analysis presented here deals with uncertainty as a trigger for control efforts. From this perspective, the organization of the event is nothing but an attempt to gain control. Social forms are routines. Orientation towards routines is a possibility to enhance control. [30]

A distinction should be made between the hosts, the guests, and one further position, the professionals (innkeeper, musician). [31]

The host has the greatest uncertainty because he very rarely takes this position. Normally he is in the position of guest. One source of uncertainty and the desire for control stems from previous experience of the host. Guests speak about events behind the host's back—so he is aware of the existence of a difference in the way the guests speak to him and what they say about him to other guests. If anything goes wrong, it will be associated with the host. Some of these uncertainties are: Will the guests have happy memories? Will the guests like the food? Is the context appropriate? How should the guests be entertained after eating? Would it be a good idea to have musicians? What kind of musicians should we have? Where should the event take place? How should the guests be accommodated? The host has to deal with his own expectations of guests' expectations. All decisions made influence the general positional system of the host in the different foci who meet at the event. [32]

The hosts of different events reported some signs of uncertainty. In the case of the Golden Wedding anniversary they began with the planning more than a year in advance. Other events investigated, like a wedding, the Abitur ceremony, Jugendweihe (youth consecration), etc., also required a lot of planning time. One reason for the long planning time is the number of guests, the need to book an appropriate banquet hall, send out invitations, etc. All the different aspects of an event have to be coordinated. All those involved have to do what is expected of them. [33]

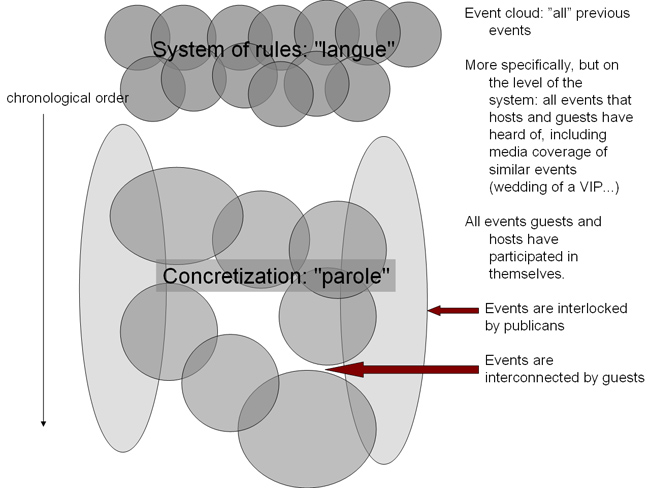

There is another source of uncertainty. With smaller events, like a birthday party after training at the local jogging club, the guests are homogeneous. Over time they will have developed their own identity with their own tradition of celebrating such events. In the case of the golden wedding, however, many different clusters of people with their own celebration traditions come together. The event is a kind of meeting between different social circles: peers from the local soccer club, skittles friends, neighbors, the family, other relatives who live in other cities. Some of them are also members of the same circles. For instance, one of the neighbors was also in the jogging club and the husband of the host’s goddaughter played soccer with the host. Nevertheless, the majority of the guests stem from different social circles/foci (SIMMEL, 1908; FELD, 1981). One means of mitigating the problem is to select a seating arrangement which is oriented towards the foci the guests belong to. It is not possible to shape the event according to the celebration style of one of the foci—the character of the event has to be compatible with the traditions in all foci. It is not only the tradition in celebrating events, a common focus will also take shape. In such a focus the way people behave and think will adapt itself accordingly. FELD and GROFMAN (2009, p.536) stated that "people associated with one focus of activity are pulled in various directions by the different other foci with which they are associated." Not only the hosts, but also the guests will anticipate the pull of the different foci, which can also trigger uncertainty. The application of traditional form elements which are accepted by the majority is a possibility to reduce the uncertainty stemming from the meeting of different foci. [34]

In the second position the guests are also uncertain. Uncertainty in the position of guests can be interpreted as a struggle for control. They do not meet so many people at the same place every day. It is very unusual for them to be watched by all the other attendees. They do not know exactly who the other guests are. They are unsure about who will sit next to them. Maybe they will have to sit next to a boring person the whole evening, while their friends sit at a different table chatting and laughing all the time. Other questions they have to answer are: Are my clothes suitable? Have I bought an appropriate gift? [35]

Last but not least, the professionals who have more routine than the other positions, but there is also some residual uncertainty: Will they acquire a reputation, thus ensuring further bookings? Can the musicians heat up the vibe? [36]

When uncertainty and the search for control are crucial to the interconnection of events, what can the different positions do to handle these problems? [37]

5. How Can Uncertainty Be Handled?

The different identities can seek for control (WHITE, 1992). The search for control makes them orient themselves towards experiences they have had in earlier, similar situations. Hence, former events (in both positions, as a guest and a host) are crucial when a forthcoming event is planned. The fear of experiments causes them to choose a form of the event which is similar to other celebrations in the past. They may know the venue from attending other events there. They take advice from the experts around them, the experts being persons who have experience in organizing events: the hosts of former celebrations and the professionals, such as innkeepers and musicians. [38]

Professionals will recommend approved forms in the range they can offer. The outcome is a minimum variation of forms because the more a situation is an exception, the greater the uncertainty. The greater the uncertainties, the more people will resort to more familiar forms. [39]

5.1 Uncertainty reduction in the position of "host"

The host has to decide on the venue for the celebration. He can choose one where uncertainty will be reduced. The idea of holding the golden wedding celebration in their own garden was not pursued by the hosts because it constituted an additional uncertainty. They did not know anyone who had organized a celebration like this in their own garden before. Furthermore the organization of the event in their garden would have required additional organizational efforts: renting a suitable marquee, finding a good caterer and arranging for additional restrooms. Hence, this idea was not calculable and the hosts did not know whether the guests would appreciate it. That was why they decided to assign the organization of the event to an innkeeper who had the necessary experience, and where the host had experience as a guest. [40]

The hosts had to decide which of the two different banquet halls to choose: the inn had a winter garden and a banquet hall. Both were appropriate. The winter garden had a capacity of about 80 persons, the banquet hall of 120. The second room was maybe a bit too big. The winter garden was the first choice because the date of the event was July 1, thus the hosts could count on good weather and the guests would be able to go out and sit outside. After some weeks of thoughts about this decision the hosts revised their first choice and booked the banquet hall. They argued that they had never celebrated an event in the winter garden of the inn before. The innkeeper said the winter garden would be all right, but the hosts were unsure about the space for the buffet and the musicians. All the other events they had attended there had been in the banquet room. Additionally the host feared the guests would disperse inside and outside. They wanted to ensure that the attendees remained together in one room for most of the evening. The reversal of their first decision can be interpreted as control enhancement. The host was on safe ground with the usual environment. In the chosen banquet hall it was very warm because of the hot weather on the day of the celebration. So the hosts discussed the decision to take that room instead of the atrium with the guests. The guests confirmed the decision of the hosts to take the banquet hall. To an observer the impression was that the decision of the hosts followed a local tradition. They had attended almost a score of events at this venue. None of the other hosts had chosen the winter garden, although other parties often chose it. The decision for the banquet hall can be interpreted as following the tradition of the crowd they belong to. [41]

The innkeeper knew she could not serve a sit-down meal for the main course so she suggested a buffet because she had had years of experience in buffets. For the first course and the dessert, the host could choose between a buffet and having these courses served at the table. In the preliminary talk with the innkeeper, she fetched a collection of menus from past celebrations and threw them on the table: "This is what former guests ordered for their celebrations." The hosts already had some ideas because they had participated in several similar events at this inn. The innkeeper stressed that she would serve everything she knew the guests would like to have. But the imagination of the hosts was limited to their experience of former celebrations there. Their picture of the meal was also governed by the limitations of the menus she showed. [42]

The innkeeper commented on the context of the menus: "These people are living there," "You will know them, too," "This was a nice event," "Venison is always popular," "People like eating salmon and pike-perch." In the preliminary talk, therefore, food became stories about former celebrations. [43]

Eating is an essential part of an event (STEGBAUER, 2006) like a golden wedding. A meal reduces uncertainty because the form is well known and it structures the evening. It is an integral part of such a celebration. The meal is scheduled to follow the aperitif which is necessary to welcome the guests and to bridge the time until everybody has arrived. [44]

When planning an event, the hosts recourse to proven form elements. These elements have been successfully applied in similar events in the past. They are based on a series of past experiences and their social valuation. The hosts endeavor to avoid experiments. [45]

5.2 Uncertainty reduction in the position of guests

The host and the closest relatives had assembled in the reception room of the inn half an hour before the celebration was scheduled to start. Some of the guests seemed hesitant to enter the room alone. They waited in the parking lot for their friends who had also been invited. When their friends had arrived they entered the banquet hall together and handed over their gifts. This behavior reduces the initial uncertainty of the situation. A further function of this behavior is to try to ensure that guests can sit next to their friends. [46]

Other sources of uncertainty are the choice of suitable clothes for the occasion and the gift, which should be appropriate. One of the younger women was improperly dressed. Some people could be heard commenting on her too short black dress and her ultrahigh heels. This departure from the norm was an obvious topic of conversation. It was the first time the young woman had taken part in an event in this social context. Probably the transfer of experiences from other events and their specific tradition line to this location was not entirely appropriate. [47]

Doubt can be reduced by making a joint gift with others or by choosing a proven gift. An example of a joint gift was a "money tree." The guests from the sports club bought a houseplant and hung rolled euro notes wrapped with floral wires on the tree. Every member of the group gave the same amount of money, which solved the problem of the gift. Many other guests gave the host a golden wedding card with a present of money. In such cases guests usually ask others what sum is appropriate. [48]

The hosts made a list of all the gifts they received. One reason is that the hosts can later personally thank the guests for the corresponding gifts. Another reason for the list is that it serves as a mental aid to reciprocate the gifts in future, similar situations. Therefore, gifts are one of the components to be borne in mind for events in the future. [49]

Guests who have neither experience nor a list can ask other invitees with experience from similar occasions about a suitable sum for a present. With the exception of a money plant, money gifts are given and received discreetly. Other gifts are displayed on a special table in the banquet hall, so the guests can admire the presents and also get ideas for similar presents for events of the same type in the future. The behavior and planning of the involvement of the guests is also based on experiences and a rating of the situational elements used. [50]

5.3 The position of innkeeper?

In the position of the professionals (innkeeper or musician) the uncertainty is limited by experience and routine, both of which have been acquired from similar events in the past. They have tested different forms and have only selected forms that have worked over time. [51]

It can be assumed that in all positions the amount of uncertainty can be reduced with increasing experience. Most of the participants, however, do not have much experience in organizing events like a golden wedding celebration. Normally the position of host is unfamiliar to most of them. The relatively certain position of the innkeeper helps the host to acquire a greater amount of certainty in terms of expectations. Uncertainty can be reduced by applying proven form elements. In most circumstances an innovation or trying out something new is only introduced with caution. More often we only find a new combination of proven elements. [52]

The hosts planned the event based on their memory. Golden bride and bridegroom considered together how the golden weddings of other acquaintances and relatives had been celebrated. What was a success on those occasions and what was not a success? During this planning phase narrations (stories) were generated. This enabled the couple and others to speak about the upcoming event. [53]

The rare change in position from guest to host allows reflexivity about the way the involved people act in reciprocal roles (host vs. participant), but it also creates further uncertainty. The hosts know what was said about previous comparable events in front of and behind the backs of former hosts, so they can estimate that there is a difference. They also know which events were judged the best. [54]

Like the aperitif and the meal, the event can be decomposed into its elements. The elements in turn can be rated as good or not satisfactory and exchanged for others, concerning the form and the content, within certain limits. It would be possible to serve a dry white wine or maybe beer instead of champagne. It would also be possible to hold the reception in the garden of the hosts at the beginning and to move to the restaurant later, etc. Such elements can be rated and negotiated in the planning phase. Some of these elements are relatively stable. We can assume that such stable elements are necessary to identify the event as a celebration of this rank. An event of this kind is structured by an aperitif and a meal. The meal should be very good, but not too select. Other necessary elements are festively decorated tables and a menu card. When 60 persons come together, nobody (except the hosts) will know all the others. Eating and drinking, therefore, function as a catalyst for communication. They make conversation easier. Homer described this ceremony of the ancient Greeks in the Odyssey: when a guest arrived they had to sacrifice, drink and eat before the narration could begin17). [55]

Variable elements include seating arrangements. Tables can be arranged in a horseshoe, in rows or guests can be seated at round tables with or without place cards. The hosts had attended a similar event at the inn around six months before. At that celebration the hosts had arranged the seating in rows. In the present example the hosts decided to seat the guests at round tables to facilitate conversation. Place cards arranged the guests around social foci (FELD, 1981), which was criticized by some guests who could not sit near their friends. After the celebration, the hosts discussed the critique, but in that situation they no longer had to make any decision for a future event. As discussed above, a sit-down meal can be served or the guests can serve themselves at a buffet. In many cases guests offer some entertainment or some of them will have prepared a speech. A musician or two can be engaged. [56]

Some elements of competition are also involved. This can be with former hosts by the selection of the venue (as usual or more up-market?) and the musicians (one, two or more?). During the planning phase, the hosts often spoke about other events and what changes they would make for their own celebration. [57]

As mentioned above, Ann SWIDLER (1986, 2000) introduced the idea of a cultural tool kit, tools being resources from which people can construct diverse strategies of action. This can take the form of "selecting certain cultural elements (both such tacit culture as attitudes and styles and, sometimes, such explicit cultural materials as rituals and beliefs) and investing them with particular meanings in concrete life circumstances" (SWIDLER, 1986, p.281). [58]

All elements used in the organization of an event stem from the cultural tool kit. The tool kit allows a variation of the elements used in constructing an event. Some variation is necessary to differentiate the event from previous events, it should not just be a replica. In fact, it is part of a second process which WHITE (1992, 2008) called the "pecking order," a competition within a position of relatively equal persons. This competition can be understood as an element of rivalry for a position in a hierarchy. [59]

The variation of elements can distinguish hosts from one another. Another form of competition in the instance of a celebration is cited by Marcel MAUSS (1954) in his description of potlatch where aborigines on the coast of British Columbia destroy their tangibles. The distinction18) in the case of the celebration of a 50th wedding anniversary can be seen as a very mild form of potlatch. [60]

By distinguishing between the different positions it becomes evident that not only the number of persons is meaningful, but, even more so, the different positions are crucial to the continuation of the form (Fig. 6). [61]

Consistent with the classical structuralist view, a distinction can be made between the system of rules: the langue and their concretization as parole (DE SAUSSURE, 1974). The langue in the case analyzed can be conceived as the whole tool kit that can be used in a society. Not all the content can be used by everybody, however, because it has to be used appropriately in a social situation. The usable part of the tool kit (corresponding to "parole") varies among the different milieus. Differences in the form of celebrating events may be caused by negotiations in a cultural setting over time.

Fig. 6: Interconnection model [62]

In the new model (Fig. 6) guests make a connection between different events by transfer. KIESERLING (1999) asked how people know how to behave when they are invited to a party. His answer was that they have learned from previous parties they have visited. Therefore, elements of behavior can be transferred from one event to another. This constitutes a limitation in the range of behavior. It means that the behavior of the participants is rooted in similar events they have attended before. This principle interlocks event types in a time chain. [63]

Transfer from one event to another can be mediated: if someone lacks experience, he will ask others or observe their behavior. Even without previous participation, former events can have an effect. [64]

Another principle of the connection of events is the mutual adjustment of dress code. Knowledge about the appropriateness of dress stems from experience of former events. Other parts of the event, like the collective preparation of show pieces (speeches, sketches, etc.), are also transferred. [65]

In the case observed, only two sketches were performed. The first was a rhyming sketch in the local dialect about getting drunk. Six of the guests came in with a cart dressed with ancient clothes. After every verse with the chorus they had to drink a "Korn" (a German spirits). It is a funny sketch in which the actors have to act getting drunk in a short time. The sketch had been performed in similar cases several times before. Once one of the hosts had acted in it with some of the present group. In another act, three men had to act while singing a love song to playback music. The men all wore dark suits, white shirts and sun glasses. They had ski shoes on their feet which were mounted by bindings on planks. The highlight was when they sang they were able to lean forward and backward at very unnatural angles. The performance was new for an event like the Golden Wedding, but it had been presented twice before, one of the occasions being the presentation of a new model by a local car dealer. Some elements like the last seem to be appropriate for various types of events. Another possibility is the local invention of elements which are communicated through the media, for instance when famous people marry and their wedding is broadcasted and finds a wide audience. Such probably new elements also become the subject of stories. These stories are necessary to open up the possibility of adapting the elements to the local framework. [66]

The stories told about events may be more important than the overlapping of guests. Stories establish and refresh the mutual knowledge about the chain of events: each celebration is an occasion to reflect on former celebrations. For instance, at the golden wedding one guest remarked to another: "They celebrated their silver wedding here, too—did we meet each other there then?" [67]

Stories are also used for a review: by referring to stories, it is decided how the next event should be celebrated (which elements can be varied and which should be retained unchanged). In fact, the people who have participated in an event together may be less important than the stories about the events. [68]

Circulating stories can broaden the knowledge about what has happened. Stories can be diffused independent of the participants when there is something out of the ordinary to tell, for instance an unusual incident. However, stories are not the truth, they are provisional (WAGNER-PACIFICI, 1996) and they are modified for every narration in respect to the social circumstances in which they are told (similar to Charles TILLY's 2006 description of giving reasons). [69]

First, events are linked by persons who are able to transfer their former experiences to future events. The switch in position from guest to host and vice versa represents an important influence in the chain. Second, a further significant mechanism which is responsible for stability is the position of the master of ceremonies. Hence it can be seen that not all participants are equal in their ability to transfer the form of events: some positions, like the innkeeper, musicians, etc., can be viewed as that of the master of ceremonies. They connect many events and play a more important role in the transfer of forms when events are organized. When they are involved in an event, they are oriented towards relatively invariant rules. These rules and forms hover over their concretization in an event as possibilities. They can be understood as a system of rules or langue, as SAUSSURE verbalized it in his structuralist theory of languages. Only some of the rules and forms are selected for a concrete situation. Here there is a similarity to SWIDLER's (1986) thoughts: only certain cultural tools are chosen for a specific situation. [70]

The slant of this study was to gather information about the interconnection of events, hence the main interest lay in comparing events from a diachronic viewpoint. From one event to the next culturally developed elements can be changed, but overall there is little difference between one event and the one that succeeds it. Changes which occur over a period of time will be included in the cultural tool kit of other hosts. [71]

A further conclusion is that not all participants are equal—professionals are responsible for a larger share of the stability, although all other positions contribute to it as well. [72]

By inquiring into the origin of the shape of events and their remarkable stability, we learn that each event is based on numerous predecessors. One important reason is the uncertainty of the participants. Many social forms are linked to other forms; "coquetry" (SIMMEL, 1917) is not conceivable without the form of the bourgeois reception. [73]

Events are interconnected by stories and participants, but it is not only the number of participants that interlock events. When a participant changes an element, it may not necessarily change the general way in which celebrations are held, but merely add a new element to the general form. [74]

Formal network models were not only the trigger for the idea of the research presented here. It is helpful to understand the structure of the distribution of stories. Stories are necessary to adapt forms proven in other contexts a specific cultural setting and their socially negotiated arrangements. How and why form elements can be used is not just a question of culture, it is also an agreement in a network which produces a culture of its own. In this respect, the network approach is very useful. [75]

What can be concluded in respect to the models of interconnection of events presented? The models have to be modified: if a larger number of persons are invited, the host needs support and the character of the event has to be changed. This means that the form is changed. The older forms are more persistent than recently made innovations. New forms have not had a chance to spread through networks or media. They are always a risk, because many guests will not know them. To avoid risks, it is safer to maintain, or revert to, established forms19). [76]

Individual memory is limited by cognitive capacity (MILLER, 1956; DUNBAR, 1993). However, memories are collective and are shaped situationally; they are vibrant and flexible. They will be modified from one narration to the next. Our interviews left the impression that it is not the most recent event that is most important for the memory and the construction of the next event. Unusual incidents are more firmly anchored than the previous event. Such incidents are often the subject of stories. And these narrations fit in with the particular situation in which they are told. An occurrence is not only something that has happened several times, it is also formed anew each time a story is told about it20). [77]

Unusual incidents are recalled and recounted, and are feared by the hosts. Efforts are made to prevent unforeseen occurrences. But such happenings make an event unique and unforgettable. As shown by the models at the beginning of the article, formal modeling alone neglects the importance of the different positions described. Two positions are crucial to the stability of the way events are celebrated: first the masters of ceremonies (professionals) are crucial to the orientation of the hosts and the framing of the events. Second and more important is another reason that could only be revealed by the procedural character of our research: it is the change in position from guest to host that leads to different experiences and many uncertainties. Efforts to control such contingencies (WHITE, 1992, 2008) lead to the orientation towards preceding forms. [78]

It may be criticized that the innkeeper, publican, musician, the host and the guests only follow social roles. To follow their roles, a network approach is not necessary. This article puts forward the idea that, because of the characteristics of situations, they need negotiations requiring the cultural tool kit, since behavior cannot be standardized by social roles. The way people decide and how they behave is an outcome of these situations. Experience from the past is an important part of this process. To cite SWIDLER's (1986) thoughts, it could be said that role behavior is a tool (a very important one) in the tool kit of the different persons involved. It cannot explain variations between different parties who have the same roles (see NADEL's paradox: DiMAGGIO, 1992). The term "position" refers to the different roles which vary from network to network. Local cultural forms cannot be explained by the role concept without a network component. This explanation has to include the context of a series of events with their participants in the past. [79]

Further research will address the recombination of form elements which are applied. If the research is important for cultural analysis, the form elements, which may be common or unique, must be considered. One possibility is the construction of three-mode models. In a chain of events, events as well as persons are connected to these elements. It was not possible to draw such a network for the "Southern Women" because of the lack of data. Moreover, the examples introduced can only make statements based on the memory of the persons interviewed. Future research, however, should take this into account. [80]

A shift in perspective from persons (and their relations) to events (and their contexts) reveals the causes of the stability of behavior. Thus, a look at the interconnection of events can be much more informative about how society works and the way people behave than the network of the participants. What can be learned from this? By exchanging nodes and edges, we hit on different and interesting findings. [81]

By shifting the perspective from the relations of persons to events and their contexts, it is possible both to reveal the causes of the stability and to explain changes in behavior. This opens up a new field for network research and network thinking: the analysis of social forms in the tradition of Georg SIMMEL, and it can also be linked to modern cultural sociology (BREIGER, 2010; FUHSE & MÜTZEL, 2010). [82]

1) The aim to reduce uncertainty is described as striving for control (WHITE, 1992). <back>

2) BREIGER (2000) demanded this with his thoughts on network analysis. <back>

3) In a similar manner, SCHWEIZER (1993) demands the use of "mixed methods" when he introduced his "flesh-and-bones" model for social network analysis. <back>

4) One reason for this is that, belonging to a group, memberships, etc. are often represented in accessible lists. Such lists make network analysis easier. <back>

5) BREIGER (1974) mentioned it, but he was not really interested in the relationship between events. <back>

6) Other different uses of the term "event" can be found in the article of MORGAN and MARCH (1992) who wrote about the impact of live events (like the death of a spouse) on their personal relationships. <back>

7) KELLER (2006) introduced investigations called "transfer research." This research focuses on the transfer of cultural elements between different countries. <back>

8) The size of the nodes represents the degree of centrality of the events (the greatest numbers of pairs of people who attended the same events). Central events are more important because the memory of events is potentially collectivized. <back>

9) DE SAUSSURE (1974) explicitly argued that people who use language at one point of time can only orient themselves on the set of current rules (synchrony)—what took place long before or what will come later is not of interest in situations where they are required to behave (diachrony). <back>

10) Problems of beginnings and ends in historical network research are discussed in BEARMAN et al. (1999). <back>

11) All events are shown—the size of the nodes corresponds to the influence—the further an event lies in the past, the greater the influence it has on the sequence of events. <back>

12) For examples of this process, see GEERTZ (1975), SWIDLER (1986). <back>

13) The size of a node corresponds to the "memory" distance to the preceding event. Generally, it can be stated that the most recent event should have a greater influence on the following one than the one preceding it, etc. <back>

14) http://www.freienohler.de/alte%20fotos/speisekarte_1909.htm [Accessed: August 22, 2011]. <back>

15) In the situation of the event it is not easy to distinguish between the giver and receiver roles. "The host thanks his guests for coming to his party. The guests respond that the pleasure was theirs" (LEIFER, 1988, p.873). Guests will receive entertainment and food and they give a gift. In the situation, giving and receiving will be balanced. In the longer run an imbalance will arise from the differentiation of the role as guest and as host. <back>

16) The triad presented here is not a Simmelian triad. It is a visualization of the structure of positions derived from the block image matrix which is known from block model analysis (see WHITE, BOORMAN & BREIGER, 1976). After clustering persons into blocks in respect to structural similarity the relationships between the blocks is regarded. <back>

17) Claude LÉVI-STRAUSS (1969) wrote about similar behavior when he recounted the exchange of wine among truck drivers in southern France. <back>

18) Distinction in this connection means that participants will outperform their peers, but only in the accepted range (BOURDIEU, 1984). <back>

19) HONDRICH (1995) called this "Methusalem principle." <back>

20) For another example of the variation of narrations, see CUNNINGHAMet al. (2010). <back>

Albrecht, Steffen (2008). Netzwerke und Kommunikation. Zum Verhältnis zweier sozialwissenschaftlicher Paradigmen. In Christian Stegbauer (Ed.), Netzwerkanalyse und Netzwerktheorie. Ein neues Paradigma in den Sozialwissenschaften (pp.165-178). Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Bearman, Peter; Faris, Robert & Moody, James (1999). Blocking the future: New solutions for old problems in historical social science. Social Science History, 23, 501-533.

Borgatti, Steven P. & Halgin, Daniel (2011). Analyzing affiliation networks. In John Scott & Peter Carrington (Eds.), The Sage handbook of social network analysis (pp.417-433). London: Sage.

Bourdieu, Pierre (1984). Distinction. A social critique of the judgement of taste. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Breiger, Ronald L. (1974). The duality of persons and groups. Social Forces, 53,181-190.

Breiger, Ronald L. (2000). A tool kit for practice theory. Poetics, 27, 91-115.

Breiger, Ronald L. (2010). Dualities of culture and structure: Seeing through cultural holes. In Jan Fuhse & Sophie Mützel (Eds.), Relationale Soziologie. Zur kulturellen Wende der Netzwerkforschung (pp.37-47). Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Corsaro, William A. & Heise, David R. (1990). Event structure models from ethnographic data. Sociological Methodology, 20,1-57.

Cunningham, David; Nugent, Colleen & Slodden, Caitlin (2010). The durability of collective memory: Reconciling the "Greensboro Massacre." Social Forces, 88,1517-1542.

Davis, Allison; Gardner, Burleigh B. & Gardner, Mary R. (1941). Deep South: A social anthropological study of caste and class. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

DiMaggio, Paul (1992). Nadel's paradox revisited: Relational and cultural aspects of organizational structure. In Nitin Nohria & Robert Eccles (Eds.), Networks and organizations: Structure, form, and action (pp.118-142). Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Doreian, Patrick; Batagelj, Vladimir & Ferligoj, Anuška (2004). Generalized blockmodeling of two-mode network data. Social Networks, 26, 29-53.

Dunbar, Robin I. M. (1993). Coevolution of neocortical size, group size and language in humans. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 16(4), 681-694.

Emirbayer, Mustafa & Goodwin, Jeff (1994). Network analysis, culture, and the problem of agency. American Journal of Sociology, 99(6), 1411-1454.

Feld, Scott L. (1981). The focused organization of social ties. American Journal of Sociology, 86,1015-1035.

Feld, Scott L. & Grofman, Bernard (2009). Homophily and the focused organization of ties. In Peter Hedström & Peter S. Bearman (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of analytical sociology (pp.521-543). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Field, Sam; Frank, Kenneth A.; Schiller, Kathryn; Riegle-Crumb, Catherine & Muller, Chandra (2006). Identifying social contexts in affiliation networks: Preserving the duality of people and events. Social Networks, 28, 97-123.

Freeman, Linton C. (2003). Finding social groups: A meta-analysis of the Southern Women data. In Ronald L. Breiger, Kathleen M. Carley & P. Philippa Pattison (Eds.), Dynamic social network modeling and analysis: Workshop summary and papers (pp.39-979). Washington, DC: National Research Council, The National Academies Press.

Freeman, Linton C. & White, Douglas R. (1993). Using galois lattices to represent network data. In Peter Marsden (Eds.), Sociological methodology (pp.127-146). Cambridge, MA: Blackwell.

Fuhse, Jan & Mützel, Sophie (Eds.) (2010). Relationale Soziologie. Zur kulturellen Wende der Netzwerkforschung. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Geertz, Clifford (1975). Common sense as a cultural system. The Antioch Review, 33, 47-53.

Hartig-Perschke, Rasco (2009). Anschluss und Emergenz. Betrachtungen zur Irreduzibilität des Sozialen und zum Nachtragsmanagement der Kommunikation. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Havemann, Frank & Scharnhorst, Andrea (2010). Bibliometrische Netzwerke. In Christian Stegbauer & Roger Häußling (Eds.), Handbuch Netzwerkforschung (pp.799-823). Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Hedaa, Laurids & Törnroos, Jan-Åke (2008). Understanding event-based business networks. Time & Society, 17(2-3), 319-348.

Homans, George Caspar (1950). The human group. New York: Harcourt Brace.

Hondrich, Karl Otto (1995). Modernisierung – was bleibt? In Heinz Sahner & Stefan Schwendner (Eds.), Gesellschaften im Umbruch. 27. Kongress der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Soziologie in Halle an der Saale, Band II (pp.799-823). Opladen: Westdeutscher Verlag.

Keller, Thomas (2006). Kulturtransferforschung: Grenzgänge zwischen den Kulturen. In Stephan Moebius & Dirk Quadflieg (Eds.), Kultur. Theorien der Gegenwart (pp.101-114). Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Kieserling, André (1999). Kommunikation unter Anwesenden. Studien über Interaktionssysteme. Frankfurt/M.: Suhrkamp.

Leifer, Eric M. (1988). Interaction preludes to role setting: Exploratory local action. American Sociological Review, 53, 865-878.

Lévi-Strauss, Claude (1969). The elementary structures of kinship. Boston: Beacon Press.

Levine, Joel H. (1972). The sphere of influence. American Sociological Review, 37, 14-27.

Litt, Theodor (1926). Individuum und Gemeinschaft. Grundlegung der Kulturphilosophie (3. erw. Aufl.). Leipzig: Teubner.

Malsch, Thomas (2005). Kommunikationsanschlüsse. Zur soziologischen Differenz von realer und künstlicher Sozialität. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Mariolis, Peter (1975). Interlocking directorates and control of corporations: The theory of bank control. Social Science Quarterly, 56, 425-439.

Mauss, Marcel (1954). The gift. Forms and functions of exchange in archaic societies. Glencoe, ILL: Free Press.

Miller, George A. (1956). The magical number seven, plus or minus two: Some limits on our capacity for processing information. Psychological Review, 63(2), 81-97.

Mische, Ann & Pattison, Philippa (2000). Composing a civic arena: Publics, projects, and social settings. Relational analysis and institutional meanings: Formal models for the study of culture. Poetics, 27, 163-194.

Morgan, David L. & March, Stephen J. (1992). The impact of life events on networks of personal relationships: A comparison of widowhood and caring for a spouse with Alzheimer's disease. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 9, 563-584.

Padgett, John F. & Ansell, Christopher (1993). Robust action and the rise of the Medici, 1400-1434. American Journal of Sociology, 98, 1259-1319.

Padgett, John F. & Powell, Walter W. (2010). The emergence of organizations and markets. Chapter 1: The problem of emergence, http://faculty.chicagobooth.edu/workshops/orgs-markets/archive/pdf/Chapter1ProblemofEmergenceJan2010.pdf [Accessed: August 25, 2010].

Rausch, Alexander (2010). Bimodale Netzwerke. In Christian Stegbauer & Roger Häußling (Eds.), Handbuch Netzwerkforschung (pp.421-432). Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Saussure, Ferdinand de (1974). Course in general linguistics. Glasgow: Collins.

Schoorman, F. David; Bazerman, Max H. & Atkin, Robert S. (1981). Interlocking directorates: A strategy for reducing environmental uncertainty. The Academy of Management Review, 6, 243-251.

Schütz, Alfred (1981). Der sinnhafte Aufbau der sozialen Welt. Eine Einleitung in die verstehende Soziologie (2. Aufl.). Frankfurt/M.: Suhrkamp.

Schweizer, Thomas (1993). Perspektiven der analytischen Ethnologie. In Thomas Schweizer, Margarete Schweizer, Waltraud Kokot & Ulla Johansen (Eds.), Handbuch der Ethnologie (pp.79-113). Berlin: Reimer.

Scott, John (1991). Networks of corporate power: A comparative assessment. Annual Review of Sociology, 17, 181-203.

Simmel, Georg (1908). Soziologie. Untersuchungen über die Formen der Vergesellschaftung. Leipzig: Duncker & Humblot.

Simmel, Georg (1917). Grundfragen der Soziologie. Individuum und Gesellschaft. Berlin: Göschen.

Stegbauer, Christian (2002). Reziprozität. Einführung in soziale Formen der Gegenseitigkeit. Wiesbaden: Westdeutscher Verlag.

Stegbauer, Christian (2006). Geschmackssache? Eine kleine Soziologie des Genießens. Hamburg: Merus-Verlag.

Swidler, Ann (1986). Culture in action: Symbols and strategies. American Sociological Review, 51, 273-286.

Swidler, Ann (2000). Talk of love. How culture matters. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Tilly, Charles (2006). Why? What happens when people give reasons ... and why. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Vedres, Balazs & Stark, David (2010). Structural folds: Generative disruption in overlapping groups. American Journal of Sociology, 115, 1150-1190, http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/abs/10.1086/649497 [Accessed: October 11, 2012].

Wagner-Pacifici, Robin (1996). Memories in the making: The shapes of things that went. Qualitative Sociology, 19, 301-321.

White, Harrison C. (1992). Identity and control. A structural theory of social action. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

White, Harrison C. (2008). Identity and control. How social formations emerge. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

White, Harrison & Breiger, Ronald L. (1975). Pattern across networks. Society, 12, 68-73.

White, Harrison; Boorman, Scott & Breiger, Ronald L. (1976). Social structure from multiple networks: I. Blockmodels of roles and positions. American Journal of Sociology, 81, 730-799.

Zerubavel, Eviatar (1997). Social mindscapes. An invitation to cognitive sociology. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Christian STEGBAUER, Lecturer in sociology at the University of Frankfurt. He is the speaker and cofounder of the Sociological Network section of the German Sociological Association. Research interests: Investigating the fundamentals of sociology with the aid of network analysis, internet sociology, communications sociology and cultural sociology

Contact:

Prof. Dr. Christian Stegbauer

Goethe-Universität Frankfurt

Fachbereich Gesellschaftswissenschaften

60054 Frankfurt

Germany

Tel. ++49 6979823543

E-mail: stegbauer@soz.uni-frankfurt.de

URL: https://sites.google.com/site/netzwerkforschung/

Stegbauer, Christian (2012). Situations, Networks and Culture—The Case of a Golden Wedding as an Example for the Production

of Local Cultures [82 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 14(1), Art. 6,

http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs130167.