Volume 9, No. 3, Art. 30 – September 2008

The Emergent Production of Analysis in Photo Elicitation: Pictures of Military Identity

K. Neil Jenkings, Rachel Woodward & Trish Winter

Abstract: This paper takes a radical view for the application of a reflexive approach to the analysis of interview data. It suggests that, if adopted, such an approach allows us to see in our data the use of an ongoing reflexivity of the researcher in the interview. As such, this permits us to observe analysis being undertaken during the interview process—not, as is reported in the literature, as a separate stage. Importantly, if we look at the work of the interviewees, we can also appreciate that they are themselves applying a reflexive approach to their interaction with the interviewer. Indeed, they also undertake a reflexive analysis of the emergent interview and collaboratively contribute to the analytic aspects of the co-produced data which is the research interview.

What we suggest is that this being the case, we need to reappraise our view of where analysis of interviews begins, recognize the reflexive nature of interview data production and the contributions of both the interviewer and interviewee to this process in order to recognize and understand the interactional and collaborative practices involved. With respect to photo elicitation we need to recognize that the photograph is not simply a source of information, of details that can be read by the informant. Rather, it is part of a collaborative interaction between the interviewer and interviewee in the production of analysis and data.

Key words: photo elicitation; reflexivity; reflexive interviewing; military identity

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

1.1 Reflexive origins of this paper

1.2 Negotiating identity and representation in the mediated armed forces

2. Photographs in Social Research

2.1 Analysis in photo elicitation

2.2 Focusing on the collaborative interaction

2.3 Presentation of data photo elicitation (autodriving)

3. The Collaborative Nature of Analysis in Photo Elicitation

3.1 Confirming emerging photographic categorization

3.2 Contributing to emerging hypotheses

3.3 Collaboration through theoretical analysis

4. Discussion

Appendix 1: The Photograph and the Interview Beyond Photo Elicitation

This paper takes a reflexive look at data collected by the authors as part of a photo elicitation project. We begin with an explanation of what triggered this reflexive return by the authors and a brief description of the research project which is its source. Following this we look broadly at the use of photographs in social research and suggest that their use requires closer inspection. We then focus on the issue of analysis in photo elicitation and suggest that the early work of the COLLIERs (COLLIER & COLLIER, 1986) notes the central issue of collaboration between interviewer and respondent. We suggest that, so far, there has been a focus on the role of the photograph in photo elicitation, which has obscured the centrality of the collaborative interaction of the interviewer and respondent. We argue that the presentation of research findings in photo elicitation tends towards writing out the role of the researcher in the production of data, and conversely writing out the role of the respondent in theorizing. Focusing on the collaborative nature of analysis, we then present three examples of photographs and extracts from data transcripts which illustrate both the collaborative work of the interview and the input into the analytic process by the respondent. We argue that a radical reflexive review of data collection and production suggests a more complex interactive set of activities by both the interviewer and respondent than is generally recognized. Additionally, we suggest that taking true cognizance of this complexity requires us to reappraise the way in which we report our research activities and findings. [1]

1.1 Reflexive origins of this paper

While working on a book chapter (WOODWARD, WINTER & JENKINGS, forthcoming) presenting analysis from a photo elicitation study we were struck by one section in which we had reproduced the following text and section of interview transcript:

"In his exchange with the interviewer, they [the respondent] discuss the wider symbolism of this [a photograph of an Irish Republican mural in Belfast, Northern Ireland]:

Interviewee: […] it is a trophy, isn't it, because there is people there, the people live in that house, you don't know, but you assume that they have okayed this sort of painting, so they are very pro IRA, and you are right, I am saying 'look at me, I am not scared of you'. Just standing next to the wall, and me mates taking a happy snappy of me, I am not scared of you.

KNJ: And you are almost taking the picture off them by saying, look this is a really [Catholic] thing, I am standing in front of it, having my photograph taken, to take it home, and it is my photograph of somewhere. 'Cause you've almost taken something, they didn't put it there for you to take a photograph in front of.

Interviewee: It was their sort of trophy, their trophy and I've gone in and taken it away from them, I suppose. I hadn't thought about that, that is very much the case.

This photograph, then, personalizes a bigger geopolitical act and by so doing extends and consolidates it." [2]

There are a number of aspects we want to draw attention to: Firstly, "and you are right, I am saying"; secondly, the interviewer's "and you are almost taking the picture off them by saying ..."; and thirdly, their reformulation of this in the third turn "It was their ... I hadn't thought about that, that is very much, the case." There is also a major fourth aspect to this when the paper produces a theorized interpretation of the transcript segment and states: "This photograph, then, personalizes a bigger geopolitical act and by so doing extends and consolidates it." [3]

At first, when we looked at what we had produced, we were initially concerned that we had corrupted our data through poor interview technique. Of course it certainly looks this way from a conventional perspective, but even from the stance of "active interviewing" (HOLSTEIN & GUBRIUM, 1997) there is a lot of collaborative work going on. On reflection, this collaborative work, we concluded, provided some insight into our methodological approach and the potential of reflexivity in photo elicitation for expanding an analysis (and understanding the production of that analysis). Whereas in active interviewing:

"The goal is to show how interview responses are produced in the interaction between the interviewer and the respondent, without losing sight of the meanings produced or the circumstances that condition the meaning-making process. The analytic objective is not merely to describe the situated production of talk, but to show how what is being said relates to the experiences and lives being studied" (HOLSTEIN & GUBRIUM, 1997, p.127). [4]

While not contradicting this approach, we felt there were issues about the reflexive work in this collaboration, which were important for our understanding of analysis in photo elicitation. [5]

1.2 Negotiating identity and representation in the mediated armed forces

Before introducing this paper in terms of its substantive concerns, photo elicitation and its modes of analysis, we shall comment about the research project from which the data we use originates. "Negotiating identity and representation in the mediated armed forces"1) was a study using photo elicitation data collection as one of its main methods. Interviewees were self-selecting respondents to local newspaper articles and a project specific web site. Respondents were primarily resident in the north-east of England, a former industrial region with a strong tradition of military recruitment. Interviewees included both men and women across the ranks from Private to Captain, with varying lengths of service across a range of military occupations. There was a slight skew in the sample towards former Royal Marines Commandos; we have no reason why this may be the case but informal correspondence has suggested that this is not unusual. Each interview was structured, following a "potted personal history" around a small sample of photographs (about ten) chosen by the interviewee prior to the interview from their own collections. The instructions for selection demanded only that the photographs be meaningful to the respondent as a representation of their military life. In every interview, each photograph was discussed in turn to explore its content, its history and social life, and its significance to the interviewee. Copies of each photograph were made after the interview, which was audio-recorded, transcribed and formed the material database of the project. (For end of award report see JENKINGS, WINTER & WOODWARD, 2007.) [6]

2. Photographs in Social Research

Photographs are increasingly used in social research. This is not only because of the transformation in the costs and quality of reproduction, but also because of a definite growth in interest in visual culture within the social sciences, evidenced by the number of texts being published. Visual research in the social sciences employs various research methods or techniques and one cannot discern a single, or even dominant, research method in this area. This paper looks at one of these methods, photo elicitation, and asks how that method is to be understood in practice, i.e. how its data is actually collected, analyzed and reported, rather than how it is described methodologically and abstractly. [7]

What distinguishes photo elicitation in academia from similar uses of photographs in other areas of media production such as photo journalism (see Appendix 1) is undoubtedly its methodological rigor and, usually, its aim of theorizing from the data. However, even with a single method such as photo elicitation there are a number of variants (HURWORTH, CLARK, MARTIN & THOMSEN, 2005), and standardization for the analysis of photo-elicitation data (HARPER, 1986) is non-existent. The version we examine is often described as "autodriven" photo elicitation. However, we believe that our observations are applicable to photo elicitation more generally, and also beyond into other areas of visual research, especially those methods which explicitly engage with respondents. We do refer to the projects of other researchers in the field, but in essence we apply a radical reflexivity to our research and suggest its applicability to others. The approach we adopt is largely an interactional approach where we look back at the transcripts and analysis of our research, post analysis, in order to re-inspect our own practices and techniques. [8]

A reflexive approach to photo elicitation is timely not only because of the growth of interest in visual studies and their methods. Photo elicitation, we suggest, is significant methodologically because of the scope of this method to address the limitations of the use of research interviews the social science. Research interviews can be problematic: "When respondents are asked to recall their actions, intentions, or understandings, their memories may be incomplete or inaccurate. They may give shortened or simplified accounts of complex events or reasoning. And their reports may be influenced by their perceptions of the researchers' expectations" (VAN HOUSE, 2006, p.1464). Photographs and photo elicitation methods are able potentially to mitigate against this problem, and as a consequence have a value in social science research beyond their use as a visual studies tool (although failures of this method have been reported, see KANSTRUP, 2002). Photo elicitation has been acknowledged to be especially useful when interviewing children where traditional verbal interviewing techniques are seen as potentially limiting, even exclusionary (EPSTEIN, STEVENS, McKEEVER & BARUCHEL, 2006). However, we suggest that it is necessary to view photo elicitation not as simply adding photographs to the research interview. Such a limited view of the method can overlook some of the complexity that needs to be considered, and it is this complexity that this paper seeks to address. [9]

2.1 Analysis in photo elicitation

Usually research (data collection) and analysis are described separately, both in method books and in research reports, but as Sarah PINK (2004) states, in practice:

"… it is difficult to separate research and analysis. Analysis is often on-going as research proceeds and researchers develop understandings of informants and their social and cultural worlds, even if this involves no formal or overt analytical methods. This might include reflexive analysis of the process and relationships through which knowledge is being produced, viewing of photographs and videotapes as a basis from which to develop further questions for the research and for the informants… The analysis of such materials will then feed back into research, enriching the knowledge base upon which the project can proceed and inspire new questions" (p.370). [10]

We agree that this is the case in practice, although not usually described in research accounts. PINK exhorts us to be reflexive about our methods of data collection and analysis and to use this in order to develop our research. We are not told what this reflexivity consists of in any detail, but it can be seen as an analytic approach to adopt towards our data. However, if one takes a more radically reflexive approach and looks at one's data, we can see that this reflexive approach already exists and is captured when for example we have audio recordings and/or transcripts of interviews. Consequently, the reflexive process does not only occur after the fact (after the interview), as a separate analytic method to be applied to data to get further results and ideas from existing data, but also during it. In fact we would go further and suggest that if one takes a reflexive look back at the data, other aspects of the research and theorizing process come to light. [11]

In what follows we make the argument for a clear, honest and participatory description of photo-elicitation research and analysis, which recognizes the role of the informant not only as data resource, but also as a resource of analysis. This is not to shift the credit from researcher to respondent, but to recognize that the data generation process also includes data analysis production, and this production is a collaborative endeavor. Furthermore, this collaborative work is usually omitted from research reporting, particularly any detailed elaboration of such collaboration. Using some examples from our own research and analysis we will illustrate this collaborative work in photo elicitation. We do not suggest this is only occurring within photo elicitation studies, but it is more likely to occur in photo elicitation research, because in these studies agency is seemingly attributed to the photographs, drawing attention away from the collaborative work of the interviewer and interviewee. Without a reflexive understanding of this process of emergent collaborative analysis and its role in our research practices is, we suggest, we would neglect the insights about the use of photographs first developed in the pioneering work of John COLLIER. [12]

The main reference point for the work of John COLLIER today is his "Visual Anthropology": Photography as a Research Method (Revised and Expanded Edition, John COLLIER, Jr., and Malcolm COLLIER 1986). The adoption of the use of photography and the development of its application in anthropology, aimed to achieve both "further and more dependable data" (p.153). Although the authors refer in this text to "photo-interviewing" and "photo interpretation by the subject of the photograph" (p.108), they are primarily concerned with a broad spectrum of uses of photography in anthropology. The issue with photographs used as data for the COLLIERs was:

"If researchers are without reliable keys to photographic content, if they do not know what is positive responsible evidence and what is intangible and strictly impressionistic, anthropology [Social Science] will not be able to use photographs as data, and there will be no way of moving from raw photographic imagery to the synthesized statement." (COLLIER & COLLIER, 1986, p.13) [13]

The COLLIERs realized that photographs can be used to elicit information from the informants that the research may not have been able to access otherwise. They also realized that one of the results of their involvement could be a "development" of the informant's self-awareness, which the researcher can utilize for new insights and improved data. The COLLIERs are not explicit as to how to apply this photographic method, or what the methodological implications could be, but they were sensitive about developing a reflexive awareness on the part of the respondent and this would be beneficial to the data collection. The COLLIERs believed that this data would lead to generalizable findings, although the status of those findings was left under-explored. [14]

The COLLIERs were aware that "Photography is an abstracting process and as such it is in itself a vital step in analysis" (pp.69-70) but recognized that "Photographs by themselves do not necessarily provide information or insight … It was when the photographs were used in interviews that their value and significance was discovered" (p.126). They knew that it was in the interview where "the action is," with photographs being seen as allowing respondents to feedback which enables "them to share in the progress of the study as they see the documents of their skill" (pp.70-71). The COLLIERs had recognized the benefits to the research of what we now call the reflexive engagement in the study of the participants. Not only have the COLLIERs become conscious about the benefits of their own reflexivity towards their use of photographs, as evidenced in their development of photo elicitation, but also of the benefits of reflexivity on behalf of the respondents. Respondents, by attending to the photographs taken and understanding what is and is not captured, can engage actively in the research, complete gaps in the research proactively, and participate in the progress of the study as "co-researchers." They make an active contribution to the direction of the data collection and its content, and possibly its analysis too. While the COLLIERs were working largely before the reflexive turn in the social sciences, and prior to micro analysis of audio recordings, it is understandable that the nature of the reflexive practices of the photo elicitation were not taken up by them. In addition, we suggest they have not been attended sufficiently to until now, at least not in a detailed fashion. [15]

We would claim that photo elicitation studies have not focused on the reflexive detail of collaborative interaction in producing the photo elicitation act, but on the photographs per se. The COLLIERs noted that photographs can be bridges between strangers, facilitating communication that may lead to "unfamiliar, unforeseen environments and subjects" (p.99). This is the message people have taken and used from their research, and in so doing ignored the less colorful verbally based social interaction and collaborative reflexive practices that underlie the power of the photographs in the interview. This collaborative work was recognized by the COLLIERs: "We were asking questions of the photographs and the informants became our assistants in discovering the answers to these questions in the realities of the photographs. We were exploring the photographs together" (p.105 italics in original). It is this collaborative aspect, which we believe gets written out of research accounts, but which is important to understanding and getting the most from photo elicitation. [16]

2.2 Focusing on the collaborative interaction

In photo elicitation, regardless of who has taken the photograph, its special role is seen as facilitating a solution to the problem of all in-depth interviewing, that of "establishing communication between two people, who rarely share taken-for-granted cultural backgrounds because it is anchored in an image that is understood, at least in part, by both parties" (HARPER, 2002, p.20). While we agree with the spirit of this statement we would be cautious about assuming the mutual understandability of the photograph by both parties. Both may understand the photograph, but it cannot be assumed that those understandings correspond. Indeed, we suggest that part of the role of the photo elicitation interview is a resolution of interpretations, a partial coming-together of understandings. [17]

The complexity of this process should not be easily passed over. The life-world depicted in the photograph may not be unambiguously obvious, even after elicitation. But significantly the elicitation of the photograph is not the task of one or the other party alone. Both are aware that that is what they are there to do. But how they are to do that is not predetermined by the method, or known in advance in detail by either party. It is something that they will collaborate in achieving, and for the interviewee especially it will be steep leaning curve—but a leaning curve that will be captured in our audio recordings if we look for it. Nevertheless, this is collaborative; the respondents understanding may not be conveyed without the in-put of the interviewer's collaborative work, much of which will not be made explicit. [18]

For the interviewer they too will be on a steep learning curve, especially when the questions they ask and discussions they produce in the photo elicitation interview move beyond the contents of photographic representation to the "life-worlds" of the interviewee and those represented, i.e. the larger phenomena, which the photographs are being used to explore or access. For both parties new information will be emergent and requires assimilating and utilizing, not just about the photograph and the elicitation process, but about how this relates to the research agenda. The researcher has to be reflexive to the information that is emerging from the interview, how that relates to the research and, broadly speaking, what direction to take the interview. At the same time, the interviewee is not some sort of cultural dupe simply responding to the triggers that the photograph produces or being blindly directed by the interviewer. They learn what the interview is in terms of a form of collaborative interaction. After a short while they begin to understand their role, start to be able to anticipate the types of questions they will be asked about the photograph, and its wider meaning. Not only can they anticipate and respond to these in advance, they may have views of what the research is attempting to understand. They can proffer not just facts or answers to questions; they can undertake their own analysis. There are complex activities underway, activities which research accounts fail to relate—and perhaps even comprehend. [19]

We do not intend to investigate why this does not occur, although it may be due to the emphasis on the role of the photograph. There is of course no disputing the potential power of the photograph. But the respondent's realization, from the use of photographs in the interview, that the interviewer does not understand the respondent's taken-for-granted "life-world"—and thus making them reflect upon it (HARPER, 2002)—is an interactional achievement. This is not a criticism of HARPER, who recognizes that a product of photo elicitation is "deep and interesting talk" (HARPER, 2002, p.23). It is merely to point out that we may attribute much to the role of the photograph, or even to the respondent in explicating it, when in fact much of the work and outcome of photo elicitation is collaborative. The consequence of this, we suggest, is an omission of the possibility for a reflexive understanding of the research method. [20]

Most reports of photo elicitation tend to gloss over the details as to the relational and contextual meanings which emerge from the photo elicitation interview which may otherwise not have occurred through the use of other methodologies (CLARK-IBAÑEZ, 2004, p.1516). Both the deductive and inductive approaches put theorizing in the work of the interviewer/researcher before or after the interview respectively, ignoring the emergent theorizing, and joint theorizing, which occurs in the interview. So while we agree that "photographs can generate data that illuminate a subject invisible to the researcher but apparent to the interviewee" (SWARTZ, 1989 quoted in CLARK-IBAÑEZ, 2004, p.1516) we must not forget that the researcher has to facilitate this, draw them out in the interview and also help the interviewee frame their responses, indeed even formulate them, perhaps even sociologize them! This is all work, which we suggest is not reported in the photo elicitation literature. [21]

As we have stated, we are concerned that the descriptions in the literature of photo elicitation may omit significant details as to how the method has been applied in practice. One area of concern is around theory building and development. We have already stated that it appears to be either prior (theory testing) or post interview in inductive analysis of the interviews. By theory building we mean the process by which "[t]he researcher builds towards theories of how and why things happen by putting themes together that appear to explain related issues. The implications of the emerging theory are examined with further questions and asked to both the original interviewees and to others." (RUBIN & RUBIN, 1995, p.59) [22]

Again we wish to suggest that just as photo elicitation does not make clear the interactive construction of the photographic based data, there is a tendency not to make explicit the researcher's impact on the photo elicitation interaction. Descriptions of photo elicitation process are simplified. As Primo LEVI (1989) warns:

"This desire for simplification is justified, but the same does not apply to simplification itself. It is a working hypothesis, useful so long as it is recognized as such and not mistaken for reality; the greater part of historical and natural phenomena is not simple, or not simple with the simplicity that we would like." (p.23) [23]

2.3 Presentation of data photo elicitation (autodriving)

There are a number of ways of using photographs in a photo elicitation interview. The term given to the way in which we used them most closely is autodriving. Of course, there are also variations within this, but in photo elicitation autodriving is a term often applied when the respondent/informant is the subject, or has taken the photographs, usually on a topic requested by the researcher (VAN HOUSE, 2006, p.1464). HEISLEY and LEVY suggested that autodriving can be traced to the film Chronicle of a Summer (1961), a cinema verite film about Parisians in 1960. It shows them being interviewed, and their responses after viewing their own interviews—this being the work on the film by the filmmaker Jean ROUCH and the sociologist Edgar MORIN (HEISLEY & LEVY, 1991, p.257). They note that "The autodriving method highlights the informant's views of ordinary realities. As they observe the moments fixed in time by the photographs, informants distinguish among elements of the typical, the unusual, the ideal." (p.269) [24]

HEISLEY and LEVY's (1991) autodriven study used photographs of informants going about their evening meals as stimuli for projective interviewing, also employed by the COLLIERs (COLLIER & COLLIER p.257). The projective interviewing in "autodriving allows [to a certain degree] informants to interview themselves, to provide a perspective of action, and to raise issues that are significant to them" (p260). It was intended that there were two rounds of informant interviewing: about the pictures, and about the pictures and their initial interview. This method, it was argued, could also provide a check on the validity of the researcher's findings. Interestingly, they found that the single round interviews worked best, and we suggest that this may be explained, in part, due to the reflexive position of interviewee (and interviewer) within the ongoing interaction of the initial interview. This being the case—and this seems also implicit in the comments of the COLLIERs—a second "reflexive" interview would become unnecessary: indeed awkward and less productive than anticipated, as reported by HEISLEY and LEVY. [25]

Another variation of autodriven photo elicitation is when "participants take photographs, choosing images and representations of themselves… it enables researchers to look at the participants' world through the participant's eyes" (NOLAND, 2006, p.2). Our autodriven photo elicitation was similar to this "projective approach" adopted by NOLAND, but rather than having the informants produce photographs specifically for the interview/research project, we asked them to select from photographs they already owned. Our study was retrospective, in having respondents show us who they were, rather than who they are. However, they are also doing a certain amount of who they are, through who they were, when selecting their photographs and telling their stories. This is a practice grounded in the "present," or "now," of the interview, and inescapably so, so our claiming to have accessed who they "were" could be mistaken. If anything we would access who they think they were "then"—but from the situation of the present, rather than at the time the photograph was taken. Our autodriving proceeded through the use of respondents' own photographs, each photograph viewing encompassing a reflexive discussion. We did not just ask about the content of the photograph but also about their explanations when, in the interview, the interviewees talked about them. So all the data was mediated by the interaction and collaboration of both parties in the research interview, and inescapably so (RAPLEY, 2001). [26]

Considering the inevitable role of the collaborative action of the interview in the production of what will become the research data, it is notable how little reference is made to it in research accounts. In their data HEISLEY and LEVY (1991) do not show any of their prompting, instead they present edited transcript sections with dotted lines illustrating that they have been edited. At least this shows they have been edited, and while this is no doubt done to show their "meaning" with greater clarity, this removes their role in the production of data. This writing out of the researcher is significant, especially as they do indicate, when discussing the merits of the method over participant observation, that

"through autodriving, informants can be asked the questions that a participant observer would normally interrupt to ask. The informant and the researcher can then examine the visual record to explore the process together, taking time with each aspect of the event, to arrive at a negotiated version of it"(ibid., p.268). [27]

So they are explicit about the collaborative nature of the method, but this collaboration gets written out of their account, or at least their presentation of data. Elsewhere VAN HOUSE (2006, p.1467) elaborates on this role of collaborative practice: "Viewing the images with the participants gave us details and meanings that we could not have developed on our own." However, almost without exception, this collaboration is made invisible in the research account. [28]

While the interviewer is made invisible in the production of data, the respondent is written out of the theory construction. Yet the collaborative nature with regards to the theorizing is alluded to when HEISLEY and LEVY state that: "Autodriving provides a type of member check to increase the credibility of the researcher's interpretation. Thus, autodriving is a positive step toward achieving the negotiated understanding that contemporary social research emphasizes as desirable" (HEISLEY & LEVY, 1991, p.269). While this negotiated understanding no doubt occurs, we would suggest it is hard to locate this in the resultant literature. We believe that the interviewee is written out of the co-constructed theory development and theory construction—or at best they are shown as merely making statements that are then theorized by the researcher. Yet at the same time we say things such as, and we use the inclusive pronoun "we" deliberately, "Autodriving leads informants into expressing and analysing the nuances of their family roles" (HEISLEY & LEVY, 1991, p.269) where we admit they theorize in the interview, but do not ascribe to it either the collaborative work that it is done on the researchers part, or the import of the interviewee in subsequent theory activity stemming from it. So, while we agree that: "Autodriving makes it possible for people to communicate about themselves more fully and more subtly and, perhaps, to represent themselves more fairly" (ibid., p.269), we believe that this is to understate their contribution to the research findings. It is rather an exploration of both the collaborative nature of data production and theorization by both parties in the photo elicitation interview that we now turn. [29]

3. The Collaborative Nature of Analysis in Photo Elicitation

That the research interview is an interactional accomplishment is not a new idea, and is indeed built into interview methods such as "active interviewing" (HOLSTEIN & GUBRIUM, 1997). The case has also been made for reflexivity when researching military topics (HIGHGATE & CAMERON, 2006), although not with a focus on analyzing interview transcripts. A discourse analytic approach of war memories collected by an oral history project, have been analyzed with the focus on their collaborative construction (FRATILA & SIONIS, 2006). These research interviews where original interviews, not undertaken by the discourse analysts and not with a view of a reflexive analysis. ROULSTON (2006) in her review of the literature precisely states that the purpose of ethnomethodological (EM) and conversation analytic (CA) analyses of research interviews "has been to explicate how descriptions and accounts are produced and co-constructed by researchers and participants" (p.515). She stresses that a substantial number of researchers have used EM, CA and Membership Categorization Analysis approaches to examine interview data; "and this number is growing" (p.516). We want to supplement this literature by looking at photo elicitation as a specific interview type and by looking at the collaborative nature of analysis. On this latter point ROULSTON quotes SHARROCK as stating that:

"[t]he correct interpretation of ethnomethodology's lesson is that professional sociological theorists and ordinary members of the society have much more in common than the traditional (professional) sociological contrast between analyst and member makes out. However, that is not because ordinary members have been found to be engaged in theorizing comparable to that conducted in the professional mode, but, instead, because the professional sociologists are (without acknowledgement) much more like the members than they take themselves to be—themselves extensively involved in operating as members immersed in the order of 'practical sociological reasoning'." (SHARROCK, 2001, p.249 quoted in ROULSTON, 2006, p.516) [30]

While accepting this, we would also accept the reverse, the complementary view suggesting that the respondent produces and contributes to sociological constructs. [31]

CEDERHOLM (2004) states that photo-elicitation in interviews is both a data collection technique and a mode of analysis, but only explains this by declaring that it is achieved through "eliciting both subjective emotions, thoughts and reflections, as well as patterns in the cultural and social construction of reality." (CEDERHOLM, 2004, p.240) By focusing on the co-construction that is taking place turn-by-turn in the interview and the reflexive practices of both parties, we can see the construction of the analytic themes. We are therefore arguing that analysis is being done in the interview, with agency by both parties and to this end we now turn. [32]

Below there are a series of examples from our data of the collaborative co-production of analysis in photo elicitation. In line with our position above, there is a focus on the work that the interviewee does in contribution to the analytic and theoretical work, which we believe can be seen as occurring in the interview. For each example, an interview photograph will be presented followed by a section of transcript from the interview, after which will be a summary of what it illustrates. It is intended that these singularly and cumulatively support the discussions above. [33]

3.1 Confirming emerging photographic categorization

Illustration 1: Liberation

Extract 1: Interview 6: 9; 191

I: Were they hanging around for food?

R: Yeah, and obviously because you are there moving around at night, they bark at everything dogs. The kids used to vanish at night, and appear when it became daylight. They had nothing either, I think when you look at my own kids, a lot of these will be, it was '91. So that was 15 or so years ago, a lot of these, he must be 8 or 9 there, late 20s now, it would be interesting to see, which goes on to my last photo really. But these are all mid-20s now, grown adults aren't they? And where they all ended up, and what is their life like now, as opposed to what it was then? It would be interesting, I would really like to be able to go back there, to see how life has changed? Because we as a nation have spent millions of pounds putting money in, and investing troops, you know, the second war that has gone on in Iraq now. It is certainly the situation in Iraq is a lot different to when I was there. It'd be interesting to see, take some of these photos back to Iraq, and see what has changed if anything. If you are able to do that, I don't know what the security situation would be like.

I: A bit rough. So you chose that one because …

R: The circumstances you know. A lot of these kids had been in to the mountains as well. So a lot of people had started to return to the cities and the towns. It is almost, they see us as their saviours really.

I: So this is a bit of a liberation photo?

R: Yeah, I think so, yeah, may be a little bit of that yeah. They were certainly pleased we were there. [34]

One of the common questions in the photo elicitation was why that particular photograph was chosen. In this example it follows an interview turn by the respondent where they have initially talked about the presence of dogs barking at night at the site in the photograph. Mentioning the absence of children during the night brings the respondent (R) to reflect that the children he is talking of would now be grown up. Noting the possibility of change in their situation now from when the photograph was taken, the investment of money, troops and a second war, the respondent suggests it would be interesting to return with the photographs, and see what if anything has changed. The interviewer (I) makes a brief comment, that the current situation of the place would likely be "a bit rough," then asks why he chose that particular photograph. The response is that it was because of the circumstances that the photograph has captured, the facts behind the presence of the children, i.e. their return from the mountains, and the memories evoked of their response to the soldiers that the respondent can also still see in the photograph—that of saviors. In the next turn the interviewer suggests a category (liberation photograph) which could describe the photograph. Noticeable is that the category is not taken directly from the description provided by the respondent, although it does illustrate their following of the description prior to and following the question of why the respondent chose that photograph, suggesting a reflexive listening to the account and how this fits with the research interview and project aims. The response to the suggested categorization of the photograph is a rather tentative agreement "Yeah, I think so, yeah, may be a little bit of that yeah. They were certainly pleased we were there." [35]

This tentativeness displays that the agreement is not total and an additional, yet positive comment is made. The respondent does not contest the category, but significantly he does not contest the need to give it a category either, he is aware that this imposition of a category by the researcher is part of the activity of doing interviewers. He is reflexively attending to what he is participating and collaborating in, even if at times passively. [36]

Initially during the photo elicitation interview our respondents did not engage in the research orientated categorization of their photographs, instead providing a more picture specific description such as "this is me at Basra Airport." A reported practice is for the researcher to use this description in their post interview analytic categorization (NOLAND, 2006).2) What we illustrate above is the researcher doing this analytic work in the interview. Additionally, respondents would pick up on the work that the interviewer was doing in their situated descriptions of the photographs and facilitate its development, often suggesting "more appropriate categories."

I: That's "jungle clearing" that

R: End-ex or whatever [37]

Here the respondent suggests that "end ex" (end of exercise) is a more appropriate category for a photograph, one based on social activity rather than on a geographical setting. This suggested category by the respondent was then applied by them as a locally co-constructed category applicable to other photographs later in the interview (and to photographs in subsequent interviews with other respondents by the interviewer). Thus the respondent directly contributed to analytic categorization of project data—not just within the interview but the project as a whole. [38]

3.2 Contributing to emerging hypotheses

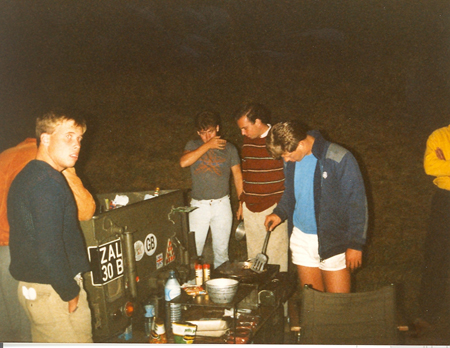

Illustration 2: End of exercise

Extract 2: Interview 6: 9; 183

R: That is the one end-ex. And the webbing there again, I think, when you have been in the military, I think it was the old 58 webbing we wore. That doesn't go anywhere without you attached to it, cause that has got everything you need to survive in, and it becomes part of your body.

I: Part of your identity

R: It is yeah, almost such, and it is your own little, you know people have got their own houses, and some people have got their own flats, and that is my flat there really, that is my personal belongings that are important to me at the time. My wife used to say to me, when I met my wife and went to the wedding, I never had anything, I had a pair of jeans and a t-shirt, and a pair of desert wellies to go out in civvy street in, because all my world at that time, and my money was spent on little bits of extra kit and beer. I didn't really need anything out in the big civvy street, because I was almost, looked after by the military, institutionalised you could say couldn't you. Horrible at the time, horrible I mean it was hard work, but I loved it. Now I love it even more looking back on it, then I did at the time I suppose. Maybe because of my age. [39]

In this segment we see the respondent has picked up the categorization of the photograph and labels it "end-ex" (end of exercise). They he continues to describe the importance of the webbing that he is wearing, that it is key to survival and becomes part of his body. The researcher is reflexively aware of the potential of this description to the research and suggests/questions its relationship to their identity: "Part of your identity." This is taken up affirmatively, with a hint of tentativeness, and the respondent then describes in what way it is part of his identity, in the same way that some people have flats and houses that contain their belongings and promote an identity. This sense of identity with just enough equipment for survival, and a change of clothes for going out of camp drinking (in civvy street) is then stressed as a minimalist one, through the view of his wife. This identity is also stressed as military with its contrast with "civvy street" as being somewhere one visited, not lived, just as one did not have a house to live in as a civilian. [40]

The significance here in photo elicitation is the collaborative nature of the interview, and not just in producing a description of the photograph and its contents etc. The interviewer may have introduced a working hypothesis that he is picking up from what the respondent is telling him, he has brought this into the discussion for "testing" its applicability by the respondent, in this case the nature of one's equipment to one's identity. What we see is that this is not just confirmed or negated by the respondent but considered and elaborated upon by the respondent giving the hypothesis some experiential meaningfulness and thus collaborating and developing a sociological construct. Of course sociological constructs may be not always responded to in a technical language, but they are responded to in a reflexive manner in terms of their contribution of the collaborative endeavor they are engaged in. [41]

3.3 Collaboration through theoretical analysis

Illustration 3: Normalization

Extract 3: Interview 2: 7; 66

R: It shows sort of from beginning, through towards the end of my army career, and it shows the changes in emphasis. You go from rugged hero diving out of helicopter to rugged hero trogging across the, across the countries. To coming slowly a bit more normal. It is quite plain from the situation, that there is nothing normal about it. It shows an interesting change in my own attitude towards my situation.

I: So in some ways it shows that the military life is really, initially heroic, camouflage, jumping around with guns in your hands. But actually …

R: A few years later, it is the lads having a barbie on holiday.

I: Yeah

R: I dunno, it'll need a psychologist to make sense of that one. I suspect it is normalisation.

I: Yeah and of course, the earlier photographs are more typical of what you might see in the newspapers, in fact the first one being from the newspaper of course. [42]

In this segment we see the respondent discussing his photograph selection in the context of earlier photographs he has selected and discussed. What is striking here is that it is the respondent leading the development of a theoretical analysis rather than the researcher. He has not been asked about the meaning of his selection as a whole, but he has become reflexive about the photographs and his collaborative work in the photo elicitation project. As part of his reflexive collaboration he engages in an analytic contrast across the photographs and, while adding a caveat about not being a psychologist or qualified to do analysis as such, nonetheless proceeds to do so. He applies a theoretical concept, that of normalization, to the analysis of the photographs and what he represents as having happened to the respondent during their time in the armed forces. This conceptual practice has not been introduced previously in the discussion. It is the result of the reflexive practices of the respondent, but also a result of the collaborative interaction in the photo elicitation interview. While collaborative, it can also be seen as the work of the respondent more than the researcher as the researcher does not initially pick up on this as they are following their own working hypothesis of the nature of press and private photographs. However, it is exactly this type of contribution of the respondent that will be picked up in the subsequent analysis of the transcript in the "formal analysis" stage. [43]

One reason for the selection of this segment is because rarely, if ever, have we seen such a contribution by a respondent get acknowledged in final reporting of the research. Yet at the same time, this sort of theorization by the respondent as a contribution to the collaborative work of the reflexive and situated analysis of collaborative interview, traditional and well as "active interviews," is unlikely to be unique. This suggests that the collaborative nature of situated analysis within the collaborative interaction of the photo elicitation and other research interviews is consciously or unconsciously written out of the research report. Instead the report of the research will follow the "traditions" of methodological accountability. [44]

Using a radical reflexive review of our own interview data we have shown how this approach highlights the reflexive collaboration in the locally situated practices of both the interviewer and respondent in the photo elicitation interview. We have argued that this approach is to our knowledge, not present in photo elicitation research literature to anywhere near a sufficient extent, and that this may be in part due to a fixation with the role of the photograph. In photo elicitation research much focus is given to what the photograph adds to the research interview. While we do not contest that the photograph does indeed bring a new dynamic to the interview, the interview is still an interactive and collaborative accomplishment, and much can be learned by taking a reflexive analytical look at that interaction. [45]

We have also argued that many research reports have a tendency to write the researcher out of their contribution to the generation of interview data. At the same time, the research reports seem to write the respondent out of any contribution to the theorization process. To an extent this may be a result of the fixation on the photograph and its contribution to the dynamics of the photo elicitation interview. However, we would argue that it is largely due to a lack of radical reflexivity to the phenomena of the photo elicitation interview itself, and that this also applies beyond photo elicitation interviews to qualitative research interviews more generally. One of the reasons for this, we argue, is the traditional separation of the data collection and data analysis processes, especially in the writing up of research. We have shown that such a separation is in fact to impose an incorrect template on research processes and practices. If one returns to the original data of the research interview in a reflexive review of the data, it is possible to locate the work of analysis being done during the interview. If this reflexive analysis is taken further, what it reveals, we argue, is that researchers are already undertaking a reflexive review of the interview while they are engaged in it. Significantly, when the research interview is taken seriously as a collaborative activity engaged in by both the researcher and the respondent, we see that the respondents themselves are no mere cultural dopes but collaborative partners, who are also reflexively attending to the research interview. The respondent is on a steep learning curve about what constitutes a research interview and how to participate. This participation can be much more than it is often credited for in the research literature, and certainly more than it is credited with in the research reports and subsequent literature. As we have illustrated from our own data, the respondents too are reflexively analyzing the research interview and undertaking their own theorizing. Of course, we wish to stress that their "own" theorizing is also part of the collaborative production of the research interview. Further, as we have seen from our examples, respondents can contribute ideas that the research has not introduced. As SHARROCK (2001) has argued, too much can be made of the theoretical competences of the researcher, we would add that too little can be made of the theoretical competences and contributions of the respondent. [46]

Whereas a reflexive approach to interviews can give us another view of our research material and stimulate new aspects of the research investigation, it may also require us to re-evaluate both the sites of theoretical activity and who is making contributions to those theoretical activities. Taken seriously, as it should be, this brings us to reconsider how we report our research activities and, we would argue, how we teach them. We suggest that these finding are not just applicable to photo elicitation interviewing, but to all similar research activities. [47]

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Ben HEAVEN and Tim RAPLEY for their observations and comments on this paper.

Appendix 1:

The Photograph and the Interview Beyond Photo Elicitation

It is worth mentioning that the use of photographs in this way is not the province solely of the social sciences—although its methodological rigor might be. For instance, in the area of the substantive topic of our photo elicitation project, military identity, there already exist texts, which apply the use of photographs in a similar way. In "This Man's Army," Martin FIGURA (1998) uses a series of posed photographs taken during his service in the British Army to illustrate military life. Not even captioned they stand textually silent apart from three short "essays" by Billy BRAGG (ex-soldier), Anthony BEEVOR (military expert) and Liz WELLS (photographer and cultural studies author) based on their viewings of the photographs. These proceed and follow the photographs alongside a biography of the photographer. In another example, where military personnel have taken photographs, but this time commenting on them themselves, is BOWDEN's (1984) "Changi Photographer: George Aspinall's Record of Captivity." Here BOWDEN (1984) has publish a text based on a television documentary where George ASPINAL discusses the photographs he took as a Japanese prisoner of war. More recently the photographer Jeffrey WOLIN published "Inconvenient Stories: Vietnam War Veterans" (2006) where he presents portrait photographs of veterans, usually at home, with a short description, using their own words from interviews describing their time in Vietnam and its impact on them. Inset into the text, where the interviewer's voice is absent, is a photograph of each interviewee from their service in Vietnam, provided by the sitter/interviewee. They do not discuss these older photographs and the reader has no idea what role they had in the interviews. In "Pictures From Far Away: A photographic record of the Falklands War, taken by members of the task force" edited by David MacCREEDY (2007) we are presented with a selection from over 700 photographs sent to him by veterans. These photographs are not co-terminus with interviews and not all are presented with a descriptive text. Those accompanied by a textual narrative either a brief catalogue of the contents or tell a story about the photograph. More recently Andrew O'HAGAN (2008) in his essay "Iraq, 2 May 2005" about one English and one American serviceman's deaths in Iraq, interviews friends and relatives of the two men and the interviews make explicit use of, and reference to, photographs of the deceased servicemen. O'HAGAN's journalism is very close to photo elicitation methods, but is analytically distinct from the photo-journalism of which Andy GRUNDBERG (1999). In "Crisis of the Real" commenting upon the photographs of Colonel Oliver NORTH from the Iran/Contra Hearings in his essay on their use by Life Magazine, GRUNDBERG states that "It suggests that photojournalism is as much artifice as actuality. It even suggests that in terms of representing history, photography is better at reproducing preconceptions than it is at revealing behind-the-scenes truths." (p.177)

1) This ESRC funded study (RES-000-23-0992) "Negotiating identity and representation in the mediated armed forces" was carried out in two parts. Part one does not pertain to this paper and involved the collection and coding of newspaper articles and photographs relating to the British Armed Forces. Part Two included sixteen photo-elicitation interviews conducted with serving and former British soldiers and Royal Marines. <back>

2) "I labelled the photographs to begin data analysis. I was able to label the data by using the answers that women reported to such questions as 'What is this?’ In the same way, I attempted to analyze the data by finding pertinent images. Next, I looked for categories by grouping concepts that seem to pertain to the same phenomena. Next, I named 'the categories and developed the categories in terms of their properties and dimensions' (Strauss and Corbin, 1990, p.69)" (NOLAND, 2006, p.10). <back>

Bowden, Tim (1984). Changi photographer—George Aspinall's record of captivity. Sydney: Australian Broadcasting Company.

Cederholm, Erika Anderson (2004). The use of photo-elicitation in tourism research—Framing the experience. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 4(3), 225-241.

Clark-Ibañez, Marisol (2004). Framing the social world with photo elicitation interviews. American Behavioural Scientist, 47(12), 1507-1527.

Collier, John (Jr.) & Collier, Malcolm (1986). Visual anthropology. Photography as a research method (revised and expanded edition). Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

Epstein, Iris; Stevens, Bonnie; McKeever, Patricia & Baruchel, Sylvain (2006). Photo elicitation interview (PEI). International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 5(3), 1-9, http://www.ualberta.ca/~iiqm/backissues/5_3/HTML/epstein.htm [accessed: August 14, 2008].

Figura, Martin (1998). This man's army. Stockport: Dewi Lewis Publishing.

Fratila, Andrea & Sionis, Claude (2006). Activating memories in interviews: An instance of collaborative discourse construction. Discourse Studies, 8(3), 369-399.

Grundberg, Andy (1999). Crisis of the real: Writings on photography since 1974 (2nd edition). New York: Aperture.

Harper, Doug (1986). Meaning and work: a study in photo elicitation. Current Sociology, 34(3), 24-45.

Harper, Doug (2002). Talking about pictures: A case for photo elicitation. Visual Studies, 17(1), 13-26.

Heisley, Deborah D. & Levy, Sidney (1991). Autodriving: A photoelicitation technique. Journal of Consumer Research, 18, 257-272.

Highgate, Paul & Cameron, Ailsa (2006). Reflexivity and researching the military. Armed Forces and Society, 32(2), 219-233.

Holstein, James A. & Gubrium, Jaber F. (1997). Active interviewing. In David Silverman (Ed.), Qualitative research: Theory, method and practice (pp.113-129). Sage: London.

Hurworth, Rosalind; Clark, Eileen; Martin, Jenepher & Thomsen, Steve (2005). The use of photo-interviewing: Three examples from health evaluation research. Evaluation Journal of Australasia, 4(1&2), 52-62.

Jenkings, K.Neil; Winter, Trish & Woodward, Rachel (2007). Negotiating Identity and representation in the Mediated Armed Forces. ESRC end of award report, http://www.esrc.ac.uk/ESRCInfoCentre/index.aspx [accessed: August 27, 2008].

Kanstrup, Anne Marie (2002). Picture the practice—using photography to explore use of technology within teachers' work practice [32 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 3(2), Art. 17, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs0202177 [accessed: August 27, 2008].

Levi, Primo (1989). The drowned and the saved. London: Abacus.

MacCreedy, David (2007). Pictures from far away: A photographic record of the Falklands War, taken by members of the task force. Whitney, UK: Recycler Publishing and Events.

Noland, Care M. (2006). Auto-photography as research practice: Identity and self-esteem research. Journal of Research Practice, 2(1), 1-24.

O'Hagan, Andrew (2008). Iraq, 2 May 2005. London Review of Books. 6th March 2008.

Pink, Sarah (2004). Visual methods. In Clive Searle, Giampietro Gobo, Jaber F. Gumbrium & David Silverman (Eds.), Qualitative research practice (pp.391-406). London: Sage.

Rapley, Timothy John (2001). The art(fullness) of open-ended interviewing: Some considerations on analysing interviews. Qualitative Research, 1(3), 303-323.

Roulston, Kathryn (2006). Close encounters of the "CA" kind: A review of literature analysing talk in research interviews. Qualitative Research, 6(4), 515-534.

Rubin, Herbert J. & Rubin, Irene S. (1995). Qualitative interviewing: The art of hearing data. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage.

Sharrock, Wes (2001). Fundamentals of ethnomethodology. In George Ritzer & Barry Smart (Eds.), Handbook of social theory (pp.249-59). Thousand Oaks. CA: Sage.

Van House, Nancy A. (2006). Interview Viz: Visualisation-assisted photo elicitation. In Gary M. Olson, Robin Jeffries (Eds.), Extended Abstracts Proceedings of the 2006 Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, CHI 2006, Montréal, Québec, Canada, April 22–27 (pp.1463-1468). New York: ACM Press.

Wolin, Jeffrey (2006). Inconvenient stories: Vietnam war veterans. New York: Umbrace Editions, Inc.

Woodward, Rachel; Winter, Trish & Jenkings K. Neil (forthcoming). Soldier photography: The negotiation of military and national identity. In Klaus Dodds; Fraser MacDonald & Rachel Hughes (Eds.), Observant state: Geopolitics and visuality. London: IB Tauris.

K. Neil JENKINGS is a Senior Researcher at Newcastle University, UK.

Contact:

K. Neil Jenkings

Institute of Health and Society

Medical School

Framlington Place

Newcastle University

NE2 4HH, United Kingdom

Phone: +44 (0)191 222 3806

E-mail: neil.jenkings@ncl.ac.uk

URL: http://www.ncl.ac.uk/ihs/people/profile/neil.jenkings

Rachel WOODWARD is a Reader in Geography at Newcastle University, UK.

Contact:

Rachel Woodward

School of Geography, Politics and Sociology

Daysh Building

Newcastle University

NE1 7RU, United Kingdom

E-mail: r.e.woodward@ncl.ac.uk

URL: http://www.ncl.ac.uk/gps/staff/profile/r.e.woodward

Trish WINTER is a Senior Lecturer at Centre for Research in Media and Cultural Studies, School of Arts, Design, Media and Culture, University of Sunderland, UK

Contact:

Trish Winter

The Media Centre, St. Peter's Campus

Sunderland

SR6 0DD, United Kingdom

Phone: +44 (0)191 515 3431

E-mail: trish.winter@sunderland.ac.uk

URL: http://seacoast.sunderland.ac.uk/~as1sth/trish.htm

Jenkings, K. Neil; Woodward, Rachel & Winter, Trish (2008). The Emergent Production of Analysis in Photo Elicitation: Pictures of Military Identity [47 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 9(3), Art. 30, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs0803309.