Volume 10, No. 2, Art. 27 – May 2009

Spaces, Times, and Knowledge for a Reflective Subjectivity in the Bellaterra Primary School

Alejandra Bosco & Montserrat Rifà-Valls

Abstract: In this article we present the results of a narrative inquiry into the construction of subjectivity in primary schools. In this study the researchers' own subjectivities came under the same scrutiny as those who were the focus of the research, and were placed in relation to them. We will discuss the doubts that arose as we carried out our research as well as how our positions as researchers changed over the course of the study. We will also describe our attempts to give voice to teachers and learners through our narratives. This goal led us to produce an account of subjectivity that was relational, process-based, and, sometimes, fragmented. Our interpretation of the representation of childhood/learners and learning in school is based upon how the teachers we have worked with shared a reflective, integral, cooperative, and community view of learning. We will also discuss how learners develop forms of positioning, identification, and differentiation depending on their relationships with others. In this way we have been able to reconstruct the way in which learners' subjectivities are formed by narrating scenes observed in classrooms with different groups of peers, and in other areas of the school where these groups carry out different activities.

Key words: children's subjectivity; narrative inquiry; case study; primary school education; research subjectivity; constructing subjectivity

Table of Contents

1. Narrating Reflective Subjectivity in Childhood: Focusing the Gaze

1.1 Methodological strategies in the narrative inquiry of children's subjectivity

1.2 The categories of analysis arising from the study: Narrating the subject in different scenes

2. The Construction of Space and Time in Bellaterra Primary School

2.1 The organization of learning space and time

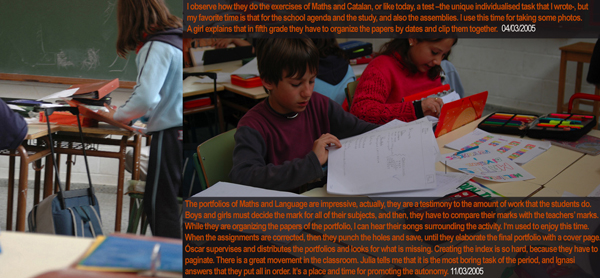

2.2 Space and time as subjective reconstructions

3. Expressing Oneself versus the Importance of School Knowledge

4. Cooperation, Self-management and Co-education

5. Conclusions

1. Narrating Reflective Subjectivity in Childhood: Focusing the Gaze1)

"A fundamental aspect of Clandinin and Connelly's approach is the idea of the researcher as someone who is inside, who sustains stories rather than just collecting them, a character who is vulnerable and necessarily in crisis. Seen from this point of view, what is generated with narrative inquiry is not strictly speaking knowledge as such, but a text that someone reads; and it is precisely here where a new and critical level of relationship lies: telling a story that allows others to tell yours. The goal is less that of capturing reality than of producing or triggering new stories."2)

This article presents a selection of texts that resulted from a narrative inquiry that explored the process of learners constructing their subjectivity in the context of involvement with various groups in the Bellaterra Primary School.3) The quotation that opens this article, written a year before the field work began, sums up one of the main purposes of our inquiry: to produce texts that represent the different subjectivities involved in the process of an educational study from a narrative perspective–researcher's, educator's, and learner's–in order for them to be reinterpreted by our readers' subjectivities. From this perspective, far from positioning ourselves as academics seeking to capture reality, we are laying claim to an exploratory subjectivity by adopting a position of not knowing; i.e., considering every observation as potentially significant. Another goal of this research is to emphasize the social and cultural contexts of the stories we collect and relate as scientists, and to recognize them as types of social action that arise from the same research (ATKINSON & DELAMONT, 2006). [1]

1.1 Methodological strategies in the narrative inquiry of children's subjectivity

In contrast to studies aimed at drawing a portrait of the learner as a subject who is promoted from grade to grade in primary schools, we endeavored to avoid objectifying and fixating the subject by putting forward a relational, process-based, and sometimes even fragmented view of subjectivity. The theories of children's subjectivity on which this study is based are related to the social constructionist approach (see HERNANDEZ, 2005; RIFÀ-VALLS & TRAFÍ, 2005). Related to this approach, we believe that there is a need to deconstruct childhood as a discursive object, and to analyze how history and science has molded it, in order to adopt a position that will enable us to consider a host of childhoods (WALKERDINE, 2007), especially in a context as prone to homogenization as school. [2]

The results presented in this article relate to ethnographies written during field work carried out during the last phase of a more extensive research project. The phases that preceded the field work were: (a) reviewing the conceptualization and theoretical frameworks for constructing subjectivity in primary schools; (b) writing our personal stories about how we believe that subjectivity is constructed; (c) analyzing public discourses on how to form subjectivity (mainly in terms of legislation and education policies and in pre-service teacher education); (d) holding discussion groups with teachers, families, and children in order to reconstruct their perceptions and understandings regarding this topic. At the conclusion of this process ethnographic field work was carried out in three different schools. The members of the research group, comprised of Alejandra, Montserrat and Laura, chose to conduct their ethnographic research in the Bellaterra Primary School because it is a state school located on the campus of the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona. Historically this school also has links with the Faculty of Educational Science, where we carry out our teaching and research activities. [3]

This ethnographic study was undertaken as a narrative inquiry; an approach that has its own rules and strategies. CORTAZZI (2001) presents four reasons justifying the idea of carrying out a narrative analysis as part of an ethnographic study: (a) narratives make it possible to share the different meanings given to experience and promote an ever-varying interpretation of events; (b) importance is given to the representation of the voices of the participants in the study, to how they live the situations and experiences recounted, in a process characterized by sharing the experiences of various groups; (c) the portrait or description as a form of interpretation in narrative inquiry is built up from the point of view of the participants, as it often takes into account qualities, values, and ways of communicating that arise from the stories, which remain invisible in other research perspectives; (d) the ethnographic study is itself presented as one of the possible accounts. Attention is paid to how the researchers construct reality, their meta-narrative and reflection strategies, and also how the researchers confront any ethical dilemmas encountered. [4]

We conducted our ethnographic fieldwork in the Bellaterra Primary School over a period of 4 months. We made observations and carried out interviews which we recorded in our field journals. During this period, and the months following our stay at the school, we collated the contents of our journals, a process that gave rise to a study report that was constructed on the basis of dialogue among the three of us. At the same time, the individual who is the focus of the research is positioned as narrator and represents one of the voices of the study, a completely different position to that assumed in traditional research. In this article we set out to challenge the colonizing view taken by many educational researchers by pursuing a narrative inquiry model in which "instead of the level of erasure that the researcher typically operates under, the researcher takes on the role of a social subject in relation to others" (LATHER, 1999, p.90). In this sense, the writing demonstrates the attempts to include others in the representation, the motives guiding the selection of narrative scenes, the moments of doubt and uncertainty, and the process of decision-making, in order to reveal the interruptions and changes of direction in our positions as researchers. It is assumed knowledge consists of narratives—in this context, stories that individuals tell in school about school—consequently, there is a type of knowledge about the school that only exists on the basis of what is recounted about it (SCHANK & BERMAN, 2006). One of the main functions of narrative inquiry is to convert knowledge based on experience into narrative, and this process is deemed complete when the story is re-transformed into knowledge by means of narrative analysis (CORTAZZI, 2001). [5]

1.2 The categories of analysis arising from the study: Narrating the subject in different scenes

The focus of our observations was on the children/learners and instruction, and the day-to-day practices of the school. The teachers we worked with share a reflective, comprehensive, co-operative, and common vision of their students; something which is quite unusual and different from practices focusing on instructing the learner based on what is dictated from the curriculum. Spending time in these teachers' classrooms allowed us to observe how individual learners develop forms of positioning, identification, and differentiation based on their relationships with others. In this way we were able to reconstruct how learners' subjectivity is formed by narrating various scenes that we observed: fourth-grade learners (9-10 years old); fifth-grade learners (10-11 years old); in the musical education class with groups of learners from different grades (6-12 years old); and in other spaces outside of the classroom where these groups engage in different activities. The narrated scenes have been selected, taking into account how our understanding of the places, processes, and forms involved in constructing the children's subjectivity improved over time. [6]

From a methodological point of view, triangulating stories from a dialogue-based perspective of ethnography has allowed us to contrast and to put together the different ways of narrating what occurs in school, while using the stories to discover continuities and discontinuities. This dialogue reveals the complementary nature of the methods that we have used (GREEN, CAMILLI & ELMORE, 2006). We constructed a final report after a process of dialogue in which different narratives interacted. We produced these narratives from the perspective of arts-based educational research, discourse analysis, and collaborative ethnography. The three different narratives interacting in the research were: (a) a narrative constructed using visual ethnography; we promoted the writing of a visual field journal and the development of participative photography with the aim of representing the school situations in postcards from the perspective of post-modern ethnography. (b) a critical ethnographic narrative brought together the situations recounted in the field journals resulting from participant observation and critical analysis; it included the voice of the researcher in the first person, transcription of interactions, graphics that described places and resources; (c) a narrative based on constructive dialogue was created with the aim of including the analysis of conversations and interviews, because cooperation between all of those participating in the research was encouraged; this led to a polyphonous narrative. [7]

Categories of analysis emerged from the research process itself, and in our specific case, they were constructed from writing and reading the journals and from the process of dialogue between and among researchers that led to writing the collective report. The ethnographic journals not only contained information to be analyzed, but also stories that represented ways of seeing how learners were present in school. Thus, observing the various areas and practices involved in the construction of subjectivity gave rise to issues needing to be interpreted. These have been ordered as follows:

Re-interpreting the learner as being someone who learns from his or her own experiences and those of others requires a permanent re-conceptualization of time and space. In the Bellaterra Primary School we observed how the typical spatial and temporal fragmentation of knowledge (i.e., the distribution of time within classrooms during learning) is subverted by tuning in to individuals' life experiences and biographies, those of the learners and of the teachers. We also observe this subversion in the procedural and experimental practices of learning, the aim of which is to promote learning based on complexity.

The learner is instructed in the spaces of liminality, which are transitional spaces for the construction of identities defined by ambiguity, openness, and change, and they are characterized by the tensions of the subject who negotiates the limits between the individual and the group identity. We have explored how individuals express themselves in different places and times, and especially the role these expressions play in constructing learners' subjectivity. In the Bellaterra Primary School, the classroom represents the place where learners relate to others, not only in ways that contribute to self-affirmation and reflect individual needs, but also represent ways of recognizing others. Taking responsibility for one's own actions, revealing personal desires, feeling part of a group with a shared culture, responding to the daily routine inside and outside of the school, are some of the actions that have allowed us to study how individuals relate to each other in school.

The forms of participating, experiencing, reflecting, and self-managing within the school enable learners to understand and to define themselves as members of a society. In the Bellaterra Primary School participation and self-management promote a vision of education and learning that considers learners' experiences and biographies as things not foreign to the curriculum and school-based knowledge. This approach means that learners do not feel restricted to a particular positioning and learn to negotiate their relationships with their peers, with teachers, with knowledge, and with the school. This gives them the opportunity to take part as learners and as members of the society of the school in which they learn to make decisions, just as they would in a democratic society. [8]

2. The Construction of Space and Time in Bellaterra Primary School

The personal and collective construction of space and time is an important factor in analyzing subjectivity in the Bellaterra Primary School. In the different contexts analyzed the technical-rational view of time, so typical of formal education, disappears, as HARGREAVES (1996) has also noted. That is, its recognition as a target resource, in the sense of equal time for every person or group, and something that is managed in order to fulfill certain educational goals which are the same for everyone involved, is replaced by a more subjective approach (HARGREAVES). Thus, what emerges is a phenomenological, subjective time, one that is lived by each individual and whose internal experience of temporality varies from person to person, in particular with regard to learning. The same happens with space In contrast to the traditional classroom, in this school a complex order reigns (TRILLA & PUIG, 2003). That is, variable and multifunctional spaces exist where different activities are carried out, which include other spaces in addition to the classroom. Both considerations promote the idea of a learner who plays a leading role in constructing and reconstructing school time and space, and who therefore has a much greater freedom to behave and to develop according to his or her needs and those of the group. [9]

2.1 The organization of learning space and time

In contrast to the definition of classrooms as places decorated and arranged to demonstrate the teacher's erudition and in which the learners are represented as empty containers waiting to be filled with academic knowledge (GAROIAN, 2001), our accounts describe spaces that engender subjective time and that promote learning through collaboration. Our description of time in these spaces does not correspond to the linearity of teachers' time. We emphasize, for instance, how the grouping of the tables in the fourth-grade classroom allows collaboration that is centered on learning rather than on instruction, in which the teacher functions more as a guide than as the main source of knowledge.

[Field journal: The organization of space and work in a fourth-grade group]

"In these classes, the tables are arranged so that the pupils are grouped into two, three, four, or five, allowing the teacher to move easily between them, since most of the time the work focuses on the pupils and his/her role is more one of monitoring the activities than of ‘presenting information' from the blackboard, although there are often moments when the work done in the groups has to be brought together and shared. In addition, although group work tends to occur regularly, it is not always the same members of the group that coincide with those with whom they share the table, which involves even more movements (both physical and social). Therefore, regardless of whether the work is done in groups or not, this spatial arrangement allows the possibility of sharing the work, the doubts, the comments, the looks, etc.; in short, life in the classroom being lived with those that are most at hand. [That is] even when they are not working in a group, the keynote is to count on others, to seek intellectual and/or affective support in others, while still developing individual activities." [10]

The way spaces are organized allows tasks to be carried out in parallel, thus turning learning time into a multi-temporality that enables different actions and situations to take place in the same space, and where students self-manage their learning. This can be clearly seen in the weekly job of arranging folders and compiling portfolios. By observing how learners in the fifth-grade index and arrange their extensive school output, we acquire a snapshot of the plurality of lived time and the fragmentation of space. In addition, these images emphasize how the creation of times and spaces in the classroom, in which the production line has been halted and a retrospective and reflective outlook is encouraged in arranging the records of the learners' own efforts, allows them to feel jointly responsible for their education.

Graphic 1: Field journal: Postcard No.6 front and back. The weekly job of organizing the folder [11]

The density of the times for performing the complex tasks of deliberation, decision-making, and collaboration co-exists with a view of school time that is divided and characterized by academic subjects. In the fourth and fifth-grade groups the learners have a weekly chart on which they make a note of the tasks, work, and projects to be carried out. This chart, decided upon by the group alone or in collaboration with the teacher, is a variable weekly schedule. Yet the simultaneity of tasks and the forming of co-operative groups in the classroom allows learners in the same class to work on different activities related to different subjects. The time for subjects taught by other teachers –such as English– is more delimited, although it is also flexible if there are special events or other more important or urgent tasks to be done. Sometimes it is the learners themselves who help to negotiate the time devoted to an activity where other teachers are involved; something that means arranging less inflexible periods of time for learning during the school day, thus allowing for conversation, problem solving, organizing, or assembling folders. [12]

The tensions between school time, learning time, and subjective time, influence learners' and teachers' ways of being at school. For example, in music classes, being limited to one hour a week per group makes it almost impossible to carry out the complex activities organized by the teacher. Based on observations in music classes we see the different factors, actions, and variables that the teacher has to co-ordinate in the same space and time to teach learners to sing and play a Christmas carol, and how they complicate the freedom needed in tasks of this type.

[Field journal: The complex management of space and time in learning music]

"After playing a song on the piano, the teacher, Juana, goes out of the classroom. In the passage there is a small cupboard opposite the door, where she keeps the instruments. She comes back carrying some metal and wooden xylophones. Some are large, others are small. She comes back saying: 'Do you remember how we play these instruments'? Juana explains how the keys represent different musical notes. While she is explaining this, the child who was earlier playing with a sausage, whom we will call Genís, has thrown himself onto the floor to arrange the keys that have been spread out. All of us watch what he is doing.

Juana marks out the notes of the song 'la sol', 'la sol' on the keys. When they hear the question: 'Who wants to come and play?' as if they were all re-connecting, many of the children want to get up and play. Juana sings a melody designed to choose the child who will go and play. María is chosen and goes over. The teacher does the same in the other corner of the semicircle and Mariona goes over. The instruments are placed on the floor, more or less in the middle of the classroom. The girls kneel down in front of them, facing their classmates. Juana leans forward and explains to them how to play. She is expressive, she points out, marks the beat, hums the song without words, only with the notes, and watches how the girls do it. Their classmates look on attentively.

The previous situation is repeated. While they are deciding who will go out this time, Genís has gotten off his chair and goes towards one of the xylophones. He plays with a key. Juana asks him what he is doing. He tells her that he wants to make a catapult with a key (...). Juana carries out individual monitoring until the children are able to play the keys that correspond to the scale, more or less well. The attention begins to flag and the children start talking to each other and they do not all pay attention to those who are playing and to the explanations. I start seeing some children acting in complicity with those who are sitting on the other side of the classroom and in these situations they speak back and forth to each other loudly." [13]

On other occasions, when the music teacher organizes complex projects, such as the Christmas Concert, the Carnival Parade, or the Floral Games, there is always a need to find more time to learn the music (for example, during break time, at midday, or at tutoring times). Therefore there were certain times and spaces that were not observed in which music learning continued, and where the teacher promoted a subjectivity designed to promote and construct individual and collective experiences collaboratively beyond the space of the classroom. [14]

2.2 Space and time as subjective reconstructions

As previously noted, space is not accepted as something given; rather it is constructed based on the practices that develop within it. Thus, in the fourth-grade classes we see how the mobility encouraged by the teacher in terms of exploiting space in the classroom also helps to recreate social relationships and offers the possibility of gaining understanding from others, something that at the same time involves reconstructing previous preconceptions and negotiating relationships.

[Field journal: Changes of location and socialization in the classroom]

"The regular changes allow the pupils to share work and every day contacts with different classmates. This involves interacting with different kinds of people, and the way each of these acts clearly also changes. In addition, occupying different places in the classroom space also affects ways of acting and of working. In fact, some places are much more convenient for working than others, and it seems to be important that the use of those places that are in an inconvenient position is 'shared' (...). It is a question of every child 'occupying' different places in a 'social' as well as a physical sense, since it is not the same to be with the person who is considered 'the cleverest in the class ' than with someone 'I get on well with', or that 'I am on very bad terms with' ...

... Every three or four weeks the work groups are changed ... In this way, the children can work on their relationships ... Conflicts are brought out into the open so that solutions can be found. This is an important exercise in thinking about themselves and about others ... Why do I want to be with this boy or girl, or why not? Why are the groups made up of just boys or just girls? The question that arises obviously depends on the conflict involved ... yet it is a case of 'finding my place' and finding one's place involves doing so with regard to others...

... It is important to understand that in this routine of changing places, the slogan is 'today it's my turn to change place', and although there is no obligation to change, there is an understanding of how important it is to change, to occupy different places, to try to work with a range of people, with those 'I don't get on with' or 'I don't really like all that much' ..." [15]

In another example of subjective reconstruction of space and of time by learners, taken from the study's visual journal, we can see how the photographic rhetoric of framing, freezing, focusing, and enlarging allowed us to visualize and to understand the relationships between a planned and constructed place, and a space that is occupied and lived in. The freezing and fragmenting of time that leads to the photographic image allows "photography to capture the uncapturable, the fragmentation of reality itself" (OROBITG, 2004, p.35).

Graphic 2: Field journal: Postcards No.3 front, and No.5 front. Outside of the classroom [16]

If we look at these postcards of the school, we can see how they recreate scenes of the transit of third and fourth-grade learners in the playground. The images reveal to us spaces in the school, as in case of the photograph on the right, where it is possible to see five girls from the fifth-grade class having their morning snack while they dance on the basketball court before the Carnival Parade begins. If we also compare these images to others that we have shown previously, which illustrate the process of arranging folders, this allows us to understand how the temporal-spatial fragmentation of the school situation makes it impossible to represent a stable subjectivity. In this way, by using our research texts we have tried to show how the children occupy multiple positions as learners in school. [17]

3. Expressing Oneself versus the Importance of School Knowledge

In many of the situations observed we found evidence of the importance the school gives to expressing oneself; that is, what the learners have to say about their everyday experiences in the school. Learners discover themselves by means of their relationships with others, relationships which are filled with experiences and memories, motivated by desires, and by others who speak to them. A self that allows learners to move forward based on experiences, not only from what has already been experienced but also what is yet to come (PEREZ DE LARA, 1998). In the fourth-grade classes, self is manifested in those spaces where decisions are made about the work to be done. These expressions include such things as: (a) Who should I work with in the course of my days at school? (b) Which group should I organize to carry out a certain project? (c) What project should I undertake? (d) How should we take part in the carnival celebrations? The school offers learners the possibility to express themselves and somehow be able to do what they wish to do, as is reflected in this comment by the fourth-grade teacher who reproduces her conversation with a girl about arranging groups by work table:

[Interview with the fourth-grade teacher: Setting up new groups]

"And now I have the following problem, now four girls have joined up here together and don't want to be separated, and other children want to join the group and they don't want to let them join ... So, in school, I always tell them that it's important for them to be ok, but also that they mustn't forget that we come here to work... These are two things that go together and one compensates and balances out the other one: 'if I am happy and don't do anything, then something is not right, and if I just work and am not happy in school, then there is also something wrong ... '. In this case they didn't want to be separated this time ... I asked the person who has been the longest in the group—'Neus, there are people ... who want to change places, I have asked you about it several times ... you have spent more time in the group ... (there is quite an important reason why I'm asking you ... because another Neus has just come, Celia has just come, Beatriz has been less time than you, and you are the one who has been the longest in this group and you haven't moved), so what do you want? Do you want to change'? And of course she is a bit like that, and she clammed up straight away, and so I said to her: 'you don't have to tell me now. Just think it over, and tomorrow you can tell me something' I say, 'and if the answer is no, then no it is, but now I'm just asking you, I'm not trying to force you' ..." [18]

In the fifth-grade group it is also very important to be able to express preferences, and even fears. We can see this, for example, in physical education (PE) classes; students protested at the beginning of the term against having to play rugby, since they had the idea that it was a very rough game. At that time the teacher tried to convince them that, unlike other sports, in rugby it is necessary to co-operate in order to play, and that far from being a rough game as the students had defined it, it is a sport in which they could have fun playing as a team, although they have to make an effort not to upset others. In the case of music classes, self-expression is observed, above all, when the teacher encourages students to create their own music by learning to construct small rhythmic sequences based on other musical compositions, and by experimenting with instruments. This is a type of work that is especially in tune with an aspect of active learning practice that encourages free choice as a way of self-control and individual development. Nevertheless, learning by focusing on action and being free to choose what I like, what I feel and what I think, is not only regulated by the self, but is often determined by: (a) the leading role that the teacher plays in the different interactions involved in joint decision-making about different courses of action; (b) the control exercised by the group itself on each individual; (c) the school culture, where each learner is expected to occupy a certain place. [19]

If we return to the example of the fourth-grade group, we can see that the teacher plays an important role in controlling the actions carried out and the decisions taken. When Rosa, the teacher, asks the learners to suggest things and provide reasons, this favors the type of learners for whom things make sense when they can act by analyzing the consequence of their behavior; i.e.: "I express myself and make a choice, but I do so bearing in mind how my actions will affect both me and the group" (from Rosa's interview). The teacher's intervention is sometimes explicit and sometimes tacit in almost all the situations in which different courses of action have to be chosen. Her or his interpretation and reasons have an important influence, as can be seen from the following fragment, in which the group, having set out to analyze the tasks they have accomplished thus far, make suggestions about what they should do next.

[Field journal: Reflections on tasks and the time devoted to them]

"Anna: More time for studying

Rosa: But we have two days, from 2 to 3 p.m. to do the homework in school ... At home you can play, you can go to the cinema, you can do a lot of things that you can't do in school, that's why we have timetables in school ... but if we don't accept the responsibility ... The timetable is there. If you need help you can ask for it, but it is now your responsibility in the fourth-grade whether you do it or not ... [The teacher is trying to find out what this proposal for more time to study means for some children]

[The pupils are not using the timetable that they have been assigned ... A small argument arises on this matter. It seems that the study hour coincides with the only hour they have when they can go and play with the computer. Another problem seems to be that some of them monopolize the computer during break-time ... Rosa tells them that they have to solve this with Montse (the monitor in charge of computers ...)]

Rosa: The point is that in study time we do other things ... perhaps you don't understand what study time means, it needs a special approach, concentration ...

[A child makes another suggestion]

Pol: More PW (personal work). In the other class they have more personal work ...

[The teacher explains that the timetable for the other course shows personal work instead of tutoring, but that the amount of PW assigned is the same ... and that's why they are confused about it ...]

Irene: I put more PW, but I meant harder things ...

Rosa: ... the problem is that if I make it harder then you won't do it ... but your parents will have to be there with you, you will have to do it with their help ... Also, if you do it badly ... after it's been marked, you won't do it again, you won't even look at it ...

[Rosa is trying to explain or give a better idea of the meaning of the different suggestions ...]

Rosa: What we can do is make the supplementary or non-obligatory tasks more difficult ...

[Paula says that she does not want any more PW, that she does other activities out of school and that she doesn't have any more time left, not even hours ...]" [20]

On other occasions it is the group that controls the situation, either allowing each learner to express herself or himself freely or not. In the music classes this can be seen in the activities where learners have to create their own music. The tension between individualism and cooperation in the group affects the way learners participate, relate to each other, and control relationships. In this activity in particular, certain members of the group appropriate the rhythm instruments. As a consequence, it is difficult to see a harmonic view of music creation and freedom of choice, because not all learners take part in groups in the same ways and with the same opportunities. In fact, this is an argument that can be extrapolated to the majority of group activities that involve experimentation and free choice in the framework of any group. As VIRURU maintains (as cited in CANNELLA, 1997), the conception of the free individual involves a view of the subject as being focused on himself or herself, independent from the surrounding world or context, having an apparently wide field of action and an unlimited access to resources when this is not always the case. [21]

It is possible to analyze the regulatory role of the school by examining the large number of artistic events that are organized to celebrate different festivities. On these occasions, while creating situations that encourage free expression, performances are staged that have been extensively prepared and controlled by the adults, and therefore these are not necessarily situations where learners are able to think and feel.

[Field journal: The Christmas concert performed by the sixth-grade learners in the kindergarten class]

"It is clear that the event has been carefully planned by the adults: the group tutors, the English teacher, the music teacher and the school practice students, and the coordinator and the teachers from the infant school. The spaces occupied by the older and the younger children are all set out: entries and exits of each of the sixth-grade pupils, the seats and the order of the youngest children, the order of the songs, how the different instruments and voices were included and coordinated, the moments for applause ... everything followed a pre-planned ritual in which there seemed to be little place for improvisation or spontaneous relation between boys and girls ... The concert also provided an opportunity to see when the children were acting with complicity, enjoying themselves, agreeing and identifying with their actions, and when the boys and girls did what the adults wanted but without knowing clearly how or why." [22]

What seems clear is that this self-expression and consideration of existential aspects of the school, which leads to everything being considered from the point of view of the self, encouraging the learners to express their opinions and feelings on one topic or another, or thinking about the group work they have carried out, means that academic content comes to take second place. One important reason for learning is to acquire knowledge about a specific subject; however, it is more important how learners approach the subject matter rather than facts themselves. This is based on the premise that learning is more closely related to daily life and to the discussion of current topics in society at a given moment, and not with things that have been stipulated by education authorities. There is clearly an effort to connect learning with the interests and lives of the learners themselves; where learning means attempting to be, to act, to live, to be involved, to have an opinion. Above all, this is learning that is situated in the broadest social context in which students participate, as a way to go beyond the classroom and to think about the world.

Graphic 3: Field journal: Postcards No.9 and No.10 front. Organizing the portfolio and the weekly assemblies in fifth-grade

"[The first day I observed the group they were holding an assembly to discuss racist insults on the football fields. In the conversation between the children and the teacher I was surprised by the spontaneity with which they raised their hands to comment on news items appearing in the newspaper: 'The Islamists intended to commit an outrage in Madrid, including the Bernabeu stadium'. Oscar, the form teacher, invites them to interpret the news item—a common practice in this class]

Arnau: These Islamists are real nutters!

Oscar: Let's look at this a bit closer and try to look critically at the person who is saying this to us, because when it is a case of criminals from here, they don't usually say what their nationality is, but if they are foreign, then yes, it is mentioned. Who are the Islamists?

Raúl: They are the ETA people [he says it quietly, and the teacher cannot hear it]

Oscar: Is Islam a country? What is Islam?

Laia: It's a religion." [23]

The previous excerpt also illustrates the type of topics that were often examined in the fifth-grade classes, where the teacher used conversation to encourage learners to analyze and deconstruct the headlines in the mass media in order to understand how these discourses affect how we form our opinions about the world. In terms of the analysis performed, we believe that the subjectivity promoted in the Bellaterra Primary School integrates learners' expressions and their biographies as much as possible, allowing learning to arise from the way they feel and think as individuals about the different situations and in the different social contexts that form a part of their actual lives in the school. [24]

4. Cooperation, Self-management and Co-education

In this section we will take a closer look at the ways learners' subjectivity is formed by adopting strategies of participation in group work as elements that encourage relationships. In the fourth-grade class being observed, as has already been noted, the arrangement of the tables in the classroom changes every three or four weeks. In addition, the groups are larger or smaller depending on how the work is organized, and it is an explicit intention of the teacher to encourage interaction and to work on relationships. As we have observed, organizing the groups involves a reflective exercise, both if the changes and regroupings are caused by the learners' desire to occupy another position physically (where they have a better view of the blackboard or are in a better place) or socially (where they choose who they want to be with) or not. This process of changing places or classmates is carried out by a shared process of decision-making in which no one forces anyone to change, and each one makes decisions according to different suggestions that they make or are made to them, and which result in a new map of spaces and relationships being formed which is very different from the map they began with. Depending on their position with regard to the suggestions for change and the moves taken arguments break out and negotiations take place. In such cases the teacher acts as mediator, and this in turn leads to new changes and positions. [25]

The systematized practice that we have just described governs the relationships in the classroom, where the boundaries between the expression of desire and the forms of subjection are not defined (see BUTLER, 1997), since it is a place where students learn to relate to and be recognized as part of a group. From a constructivist standpoint (GERGEN, 1992) this allows us to recognize the process of identity-construction as something associated both with the self and with relationships with others, and with the formation of subjectivity in the multiple contexts and power relationships in which we take part as individuals. In this way, subjectivity is not seen as something that happens within individuals but rather as something that is constructed in a dialogue with others, on the outside, which is formed by negotiating meanings between how individuals perceive themselves, the way they relate to others, the immediate environment, and the larger context.

[Field journal: Social and collective identity as a point of reference]

"How does this practice influence and affect the processes of subjectivization, where being in the group takes on an important role, and where the group or groups are what regulates the relationships between individuals, as well as the teacher on a secondary level, intervening when he or she believes it necessary or when asked to? Up to what point is every child capable of expressing their desire to be in one place or another and of finding ways of achieving this? Up to what point are the rules of the most skillful not imposed in order to play with them? Each of the children, with his/her desires, motivations, interests, etc., adopts very different positions when faced with this situation. The interesting thing to be learned here is the possibility of becoming aware of these desires, motivations, stories, feelings that this practice offers every individual ... The teacher's aim is to encourage a more self-sufficient individual, to develop a certain autonomy in the group in terms of deciding where to go, who to work with ... to be more or less independent, depending on what the group is capable of doing. Lastly, this practice can be understood as a small area of decision, where every pupil takes responsibility for him or herself, in a dialogue with the world; a world that limits them in the group but that also allows them to define themselves in diverse social frameworks." [26]

In various situations and settings we have been able to verify the importance that the Bellaterra Primary School places upon relationships in childhood and its view them as productive. Forming subjectivity is interconnected with learning about social relationships, both in daily life (inside and outside the classroom) and when socializing is encouraged to facilitate the learning of a specific task or skill. In both cases learners are encouraged to form groups, and the teacher works to ensure that these are highly cohesive. In the music classroom and in the rugby sessions, the learners have to act in a coordinated way, whether to play a song in a concert or to play in a match. The subjective positions that arise as a result of these suggestions are diverse and sometimes difficult to perceive: whether mobility and change is provoked by emotional or rational motives, whether it arises from the learners' conscious desire or the teacher's will. The school challenges individualization by constantly creating spaces for socializing and democratic participation, and cooperation is a part of an ideological model that drives the education and learning situations, despite the fact that random factors and the unexpected sometime intervene in these processes. This is something that the entire teaching staff has taken up, as can be seen from the fragment below. Teamwork is a philosophy shared by the teachers, who draw up timetables, share situations and decisions, and also train as a group. The school's discourse promotes a forming of subjectivity in which great importance is given to belonging to the community, both for teachers and for learners. As a consequence, constructing a personal and social identity thus takes on a political dimension.

[Field journal and interview with the teacher Juana: Cooperating in order to learn and learning to cooperate]

"For instance, coordinating a group to sing a song in the Christmas concert may mean that one group of children are singers and another group instrumentalists, and that they have to be coordinated. The decision of who occupies one position or another is based on drawing straws, and the final result may mean that the position of instrumentalists may be won by children who find this work harder than others, as perhaps in the case of Miquel ...

... [T]he defense that Juana puts forward for her approach to teaching and learning music, in spite of the difficulties that arise in the classroom, is based on her reluctance to adopt an instruction-type model for learning music. Juana feels committed to encouraging a special contribution of music in forming a social, participative, intergenerational pupil within the school community. She admits that in order to promote this type of school subjectivity, music teaching must be based on promoting situations that are existentially significant for the groups:

'Sharing experiences with other music teachers from schools that are more of the chair, table and pencil variety, and where the children do not move around much in the classroom, I see that the children here accept music very well, because it is an opportunity to rethink spaces and relationships in a different way. Yet in addition to the music, here they are very used to learning in more all-embracing situations that are not restricted to the table and chair format'." [27]

From the point of view of the equality of gender relationships, fourth-grade and fifth-grade teachers worry about the equal training of the groups. The number of boys or girls in the same group often breaks down, resulting in an unequal number of boys and girls, encouraging the forming of equally mixed groups in the work tables or games. In the fifth-grade class, and in the various music education groups that we observed, it seemed that situations arose where boys and girls played different roles, they play and learn differently; power gender relationships are visible in situations where to retain either instruments or balls can generate a conflict. In the music education classes some girls feel that their training as instrumentalists gives them authority to take part actively in the group; whereas, on other occasions they are rejected by some of the learners and pass unnoticed. [28]

Nonetheless, when the tasks were being carried out, the boys and girls in the fifth-grade were just as likely to argue with each other as they were to help each other to take the initiative and come to agreements, regardless of the individual's sex. We observed numerous spontaneous situations marked by inequalities and conflicts among the learners, inside and outside classroom, with all of these being resolved in a different way each time, where the same boy might respond with a sexist comment. [29]

Tackling the opportunities and the difficulties that arise during group work involves giving importance to social relationships and sex roles taken on by girls and boys; accepting, for example, the need to look for a balance between co-education and cooperation. During the research process we realized the need for re-conceptualizing FREINET's idea of cooperation at present, in all its didactic, cultural, and social forms (RIZZI, 1996). FREINET (1896-1966) defined cooperation according to the creation of a practical environment that promotes collaborative work between teacher and students in the classroom, and a shared construction of knowledge and self-expression. In addition, co-operative life in classrooms and between classes requires a type of organization and training based on deliberation, voting, shared reflection, responsibilities, group work, assemblies, memory, collectivization of material, forms of solidarity, and so forth, all situations that we observed throughout the study.

Graphic 4: Field journal: Postcards No.4 and No.11 front. Participating in a group as individuals subject to social and gender

relationships [30]

In order to re-conceptualize cooperation, we assume that working as part of a group encourages the construction of mobile subjective positions and allows for understanding that subjectivity is relational. According to the notion of post-modern childhood (WALKERDINE, 2000), which suggests that hybridization and performance are dynamic processes in the construction of identity, we observed that children do not always occupy the same position of dominator or dominated. Despite the fact that power relationships are no static and that students performed different social roles, they sometimes reproduced gender-based power relationships and stratifications. These situations emerged from the analysis of the activities engaged in outside the school tasks and the regular curriculum. If we analyze the Carnival fancy dress costumes chosen by the boys and girls in the fifth-grade to reflect desired identities from the perspective of power and gender relationships, we can see how the social and gender order is reproduced and altered: boys dressed as girls or old women, boys who carry guns or who dress up as war wounded, or as Charlie Chaplin; girls who dress up as angels or demons, skaters, or wear Asian costumes, etc. These roles are as diverse as are the topics that the learners comment on in class assemblies, which reinterpret FREINET's idea of cooperation as a means of feeling committed to the world in order to carry out complex tasks in the current primary school. We observe this, for instance, in a discussion about taxes and the role of the Spanish Central Government with regard to Catalonia, and how this affects pension, education, and health systems; we observe it in a conversation on racism on football fields, but also in analyzing play situations in the playground, from the perspective of being a boy or girl, of belonging to one grade or another. As ethnographers, we have learned that future research must focus on the analysis of children's power relations in transforming the process of cooperative learning in a postmodern context. [31]

We began the article by pointing out that the voices making up this narrative inquiry were vulnerable and in crisis, and we see that in the excerpts we provide to create the narrative analysis. Thus, instead of affirming the self of the researcher through the process of writing in our journals and reports, we preserved the different modes of telling others our ethnographic experiences during the dialogical process of writing a narrative analysis. We also noted that one of the study's aims was to tell a story that would allow others to tell theirs. From our own account as researchers there emerges some issues that we believe to be fundamental regarding the contribution that the Bellaterra Primary School has made to constructing children's subjectivity, and these represent the central themes of our study. [32]

Learners' self expression is made visible in the school by means of their experiences, feelings, activities, desires, fears, and perceptions, and simultaneously constitutes the school's basic raw material for promoting any type of learning by creating a subjectivity that is aware of its needs, feelings, and potentials. [33]

This self expression has a number of limits, which range from the local to the general: the needs of the group as a set of subjectivities, the acquisition of knowledge that they are committed to, the culture of the school and the world in which they live. All these components regulate a process that would otherwise be unsustainable, and which leads to a constant need to negotiate the limits between self and others, from which a reflective subjectivity emerges. This negotiation encourages different ways of participating in school life, helping the learners to develop their knowledge and skills and learn to be members of society, to make their own decisions, to share these with others, and to find a consensus, just as in a democratic society. [34]

The aforementioned premises lead them to question and personalize their individual learning and their way of being-in-school. In this sense, we have narrated practices that reconstruct space and time, which are transformed so that they become better suited to the needs of learning and, also, practices that re-select the contents of learning and activities, all common practices directly promoted by the school. [35]

The subjectivity that the Bellaterra Primary School constructs is that of learners who think about themselves and practice self reflection, understanding that in order to shape a learning community, they must take part and make decisions collectively, many of which involve transforming what is given (e.g. curriculum and timetables) in order to create something new, resulting in an improved learning experience for everyone. [36]

We also believe that, from a methodological point of view, our study's contribution rests particularly on the use of complementary methods to narrate what happens in the school, adding a narrative constructed from visual ethnography to the ethnographic narrative represented by the field journals, and to the narrative based on dialogue and represented by conversations and interviews in a constructive and co-operative dialogue. The combination of these three methods will improve the exchanges between the various researchers, as will the inclusion of the viewpoint of all those involved in the study. On occasion, something related by one researcher would appear reflected in a photograph taken by another, or in the voices of the learners. During this process we learned from each other, and we also felt involved in collaborative writing. Thus we decided do not distinguish the authorship of the several journals we wrote, the reader can identify different styles and modes of writing, as well as different ways of understanding and representing the construction of children's subjectivity at school. Exchanging different documents in order to write all of the study's reports has been a shared exercise that made us even more aware of our positions and biases in the field of education, since this exchange proved highly complex on occasion, revealing widely different viewpoints of the same event. [37]

Nonetheless, and despite the richness in using all of these narratives, we cannot help feeling that we should have made an even greater effort to promote what we outlined as one of the goals of this narrative inquiry: that is the fact that every participant could recount his or her own history from our history. In carrying out the study there was a need for more instances to promote these other narratives, both from the teaching staff and from the learners who took part. In this sense, we believe that one of the ways of continuing this work in the future and in other school contexts should involve taking the construction of these new narratives into account in a proactive way; in other words, empowering the writing of teachers' and learners' narratives as a main goal of the research. [38]

1) The case study analyzed in this article was carried out within the study The Role of the Primary School in the Construction of Subjectivity, funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (ref. BS02003-06157) and coordinated by Dr. Fernando Hernandez in association with the consolidated research group FINT (Formació, Innovació i Noves Tecnologies) at the Universitat de Barcelona, directed by Dr. Juana Ma. Sancho Gil. We would also like to thank Laura TRAFÍ for her participation in constructing the cases, since without her texts and daily encouragement it would not have been possible to carry out this study. <back>

2) This fragment is extracted from the records of meetings of the research group FINT that Isaac Marrero wrote during the 2003-2004 academic year. <back>

3) Infant and primary education schools are known as CEIP (Centros escolares de Educación Infantil y Primaria). We would like to thank the teaching staff and the students of CEIP Escola Bellaterra for their close collaboration throughout the study. Sharing and writing about their experiences and reflections has given us a better understanding of how subjectivity is formed in a primary school. Although we publish the name of the primary school in this article, we will protect the students' and teachers' identities as research participants by replacing their real names with pseudonymous. <back>

Atkinson, Paul & Delamont, Sara (2006). Rescuing narrative from qualitative research. Narrative Inquiry, 16(1), 164-172.

Cannella, Gaile S. (1997). Deconstructing early childhood education. New York: Peter Lang.

Cortazzi, Martin (2001). Narrative analysis in ethnography. In Paul Atkinson, Amanda Coffey, Sara Delamont, John Lofland & Lyn Lofland (Eds.), Handbook of ethnography (pp.384-394). London: Sage.

Garoian, Charles (2001). Children performing the art of identity. In Yvonne Gaudelius & Peg Speirs (Eds.), Contemporary issues in art education (pp.119-129). Upple Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

Gergen, Kenneth (1992). El yo saturado. Dilemas de la identidad en el mundo contemporáneo. Barcelona: Paidós.

Green, Judith L.; Camilli, Gregory & Elmore, Patricia B. (Eds.) (2006). Handbook of complementary methods in education research. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, published for the American Educational Research Association, Washington DC.

Hargreaves, Andy (1996). Profesorado, cultura y posmodernidad. Madrid: Morata.

Hernández, Fernando (2005). Cómo se ven y cómo se sienten. El papel de la escuela primaria en la subjetividad infantil, Cuadernos de Pedagogía, 350, 56-60.

Lather, Patty (1999). ¿Seguir la estupidez? Resistencia estudiantil al currículum liberador. En Marisa Belausteguigoitia & Araceli Mingo (Eds.), Géneros prófugos. Feminismo y educación (pp.89-115). México: UNAM-Paidós.

Orobitg, Gemma (2004). Photography in the field: Word and image in ethnographic research. In Sara Pink. Lásló Kürti & Ana Isabel Afonso (Eds.), Working images. Visual research and representation in ethnography (pp.31-46). London: Routledge.

Pérez de Lara, Núria (1998). La capacidad de ser sujeto. Más allá de las técnicas en educación especial. Laertes: Barcelona.

Rifà-Valls, Montserrat & Trafí, Laura (2005). La producción de narrativas pedagógicas de la subjetividad y la diferencia en los discursos visuales de la infancia. En Paulí Dávila & Luís M. Naya (Eds.), La infancia en la historia: espacios y representaciones (pp.63-73). Donostia: Espacio Universitario Erein.

Rizzi, Rinaldo (1996). La cooperación en educación. Sevilla: MCEP.

Schank, Roger & Berman, Tamara (2006). Living stories. Designing story-based educational experiences. Narrative Inquiry, 16(1), 220-228.

Trilla, Jaume & Puig, Josep Maria (2003). El aula como espacio educativo. Cuadernos de Pedagogía, 325, 52-55.

Walkerdine, Valerie (2000). La infancia en el mundo post-moderno: La psicología de desarrollo y la preparación de futuros ciudadanos. En Tomaz Tadeu da Silva (Ed.), Las pedagogías psicológicas y el gobierno del yo en tiempos neoliberales (pp.83-108). Sevilla: M.C.E.P.

Walkerdine, Valerie (2007). Hay una multiplicidad de infancias, entrevistada por Inés Dussel, http://www.me.gov.ar/monitor/nro10/dossier5.htm [fecha de acceso 28.05.2008].

Alejandra BOSCO is an assistant professor in the Faculty of Educational Science, Department of Applied Pedagogics, at Universitat Autónoma de Barcelona. In her research work she has experimented with the use of various methodological strategies linked with qualitative research, as applied mainly to the study of curricular innovations in educational centers, and their role in the development of the subjects involved.

Contact:

Alejandra Bosco

Deptartamento de pedagogia aplicada

Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona

Edifici G6

Campus de Bellaterra (Cerdanyola del Vallès)

Spain

Tel. +34 93 581 2635

Fax +34 93 581 3052

E-mail: Alejandra.Bosco@uab.cat

Montserrat RIFÀ-VALLS is an assistant professor in the Faculty of Educational Science, Department of the Didactics of Music, Visual Arts, and Physical Education, at Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona. In her research she experiments with the use of visual methodologies to narrate the curriculum as a process, and the construction of subjectivity and diversity in schools.

Contact:

Montserrat Rifà-Valls

Deptartamento de pedagogia aplicada

Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona

Edific G6

Campus de Bellaterra (Cerdanyola del Vallès)

Spain

Tel. +34 93 581 2635

Fax +34 93 581 3052

E-mail: montserrat.rifa@uab.cat

Bosco, Alejandra & Rifà-Valls, Montserrat (2009). Spaces, Times, and Knowledge for a Reflective Subjectivity in the Bellaterra Primary School [38 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 10(2), Art. 27, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs0902273.