Volume 12, No. 1, Art. 2 – January 2011

Hyphenated Research

Francesca Bargiela-Chiappini

Abstract: This article is about methodological and personal stock-taking from a specific vantage point. The immediate inspiration for it was a joint conference presentation on the concept of "whole lives", towards which a Japanese academic and I worked together over a period of time. In my case, this collaboration became a catalyst for a process of re-evaluation of a long engagement with qualitative research. Besides the advantages and limitations of a (distance) dialogic approach to collaboration over the conference presentation, extended conversations with my Japanese colleague instigated a re-appraisal of the inventory of understandings, concepts and practices that I had accumulated over the years. Even though self-reflexivity had characterised much of my work, the need to approach familiar topics differently, prompted a radical examination of my self-positioning as a re-search-er.

In this article, I will trace the emergence and the features of a mode of being in the field, and in life, which I have labelled "hyphenated-research". I will illustrate this with reference to the process of conceptualising "whole lives", for which I collaborated with Hiromasa TANAKA.

Key words: reflexivity; philosophical hermeneutics; "re-search-ing whole lives"

Table of Contents

1. The End

2. Questioning

3. Implicating

4. Extricating

5. Another Way of Understanding "Understanding"

6. Retelling the End: The Pre-text

7. A European Finding for a European Quest: Meeting (Philosophical) Hermeneutics

8. Asking "the Question" and "Questioning"

9. Staying in the Circle

I will begin this paper from the end, from the most recent event in my personal research chronology. Conceptualising "whole lives" in our respective socio-historical settings is the task that Hiromasa (Hiro) TANAKA and I undertook in May 2008, not only with a view of submitting an abstract to a critical management studies conference (BARGIELA-CHIAPPINI & TANAKA, 2009) but also as a way to experiment with researching "across cultures and across languages". From the earliest planning stages, concern for process was as important, if not more important, than outcome, at least for this author. How we were going to do what we set out to do, what trajectories our explorations would take, what experiential resources we would draw upon and what associations we would exploit were the tacit concerns of our joint project. "Tacit" because I initially proposed to Hiro TANAKA that we could try to develop our narratives separately, and then bring them together dialogically in the conference paper. At that point I (naively) thought this would be the best approach to capturing the essence of "difference"—in thinking, arguing, writing—that supposedly characterised us as representatives of "western" and "eastern" discourses. [1]

"Whole lives", then, became a metaphor for an experiment in collaborative research which eventually unravelled into, among other things, an anti-essentialist re-appraisal of the concept of "culture-s", a topic that had cropped up at regular intervals in my earlier research. This anti-essentialist mood also challenged the (western?) self-other dichotomy predicated on the independence of the individual (see BARGIELA-CHIAPPINI, 2009). In the same anti-dichotomic spirit, the "whole lives" paper gave me the opportunity to question the "life-work balance" as oxymoronic: work is in life, in fact, it is a substantial component of it. In the end, reflection on the contents of the conference paper produced another dichotomy, that of "active life-contemplative life". But there is a difference between the two dichotomies mentioned thus far, in that the first usually implies an unresolved conflict, whereas the second emphases complementarity. As I went on to argue at the conference, all forms of activity, including work, require moments of contemplation, i.e., times of in-activity, reflection and attentiveness to serendipity and creative promptings. [2]

By the time the two separate abstracts were developed and my co-author and I agreed to submit them as parallel texts in a two column document, the whole lives project had begun to reveal at least two distinct, if intimately connected papers: one on the process of working out a definition of the concept and the other on the outcomes of such process. A two-fold journey towards "whole lives" as seen from the author's perspective is the object of the current paper. [3]

For me, the main mode of being within the whole lives project has been one of continuous questioning: of self, of my assumptions and their origins, of the "knowledge" accumulated over years, of my current status as a re-searcher. Here, the hyphenation captures the iterative nature of the process of re-search. Inevitably, questioning extended to my co-author, in the e-mail threads running into thousands of words that Hiro TANAKA recovered and which provide a partial map of the dialogic work of noticing, probing, exploring, associating, recalling, reflecting, debating, etc. of which our virtual collaboration consisted. We agreed before the start of the project that ours would be two separate narratives thus almost inevitably leading to separate conceptualisations of "whole lives", which would be based on our respective "cultural traditions". The final act, the conference presentation, would demand that we came together to "agree" on a joint text, which however still consisted of two embedded yet individual stories. [4]

The start of the whole lives project found me already steeped in an enquiring mode as a consequence of becoming involved in another publication project with a colleague who, like me, thought it possible to write "something different" on qualitative research in organisations. Having jointly to fill the space of a book forced me to operate in rewind mode: my research vocabulary, my conceptual inventory, the discourses of which I had partaken, the qualitative method(ologie)s which I had applied during two decades of research, everything was exposed to scrutiny. [5]

By comparison, the more modest "whole lives" project acted as a temporary gelling agent and became a sounding board for various streams of thought inspired by as many concepts, each embedded in multiple layers of disciplinary discourses and debates. [6]

From my early days in the field, my understanding of research-ing, which later became re-search-ing—to reflect the iterative and processual nature of this particular way of being in the world—included a heightened awareness of the presence and importance of other people in my work, be they the managers who agreed to be interviewed, or the colleagues from various corners of the globe with whom I published, or the myriad of voices from occasional encounters outside academia. It is only when the dust of experience begins to settle and eventually sediments into layers and patterns of understanding that one realises how much qualitative research in the social sciences depends on human encounters, and on involving oneself with others and involving others in one's own life. In this sense, my qualitative research experience has always been plurivocal; it was always with some apprehension that I was obliged to set artificial temporary boundaries around it, in the form of publications and research projects, only to find that what was left out, the unwritten, the ephemeral, was probably more important than what went forth for peer evaluation and academic dissemination. [7]

Working with British and Italian managers and executives as a language tutor and later as a researcher intent on analysing organisational life as a temporary outsider was my first experience of fieldwork in the late eighties. As a linguist with a modicum of discourse analysis, as well as an associate alongside managers in their quest for the elusive competencies that intercultural contact demands I repeatedly faced the challenge of responding to limiting textbook knowledge and prescriptive approaches; what I had learned from the academic literature did not seem to make much sense in the "real world" of work. The "dos and don'ts" approach was too crude for the needs of British senior managers expected to engage socially and professionally with their Italian counterparts. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, in Europe the gap between (communication) doctrine and practice was huge; (applied) linguistics, if it had engaged with workplace communication at all, had been left behind by discourse analysis and pragmatics, which, in turn, had not yet met management and organisation studies (MOS). [8]

Getting involved in other colleagues' disciplines and puzzling out managers' worldviews was more than just satisfying intellectual curiosity. After the first timid approach to organisational life, it became obvious to me that analysing excerpts of meeting discourse out of context could no longer be justified; neither in terms of good research, nor in terms of a deeper understanding of human interaction. Making sense of what research by a linguist-turned-organisational-ethnographer meant to the people involved, insiders as well as outsiders, called for engagement with a social constructionist ontology. Sensemaking, in the Weickan tradition (WEICK, 1993, 1995)1), seemed at the time the best interpretive approach to workplace lives while I was intent on watching and analysing employees' discursive practices. [9]

After a period of exposure to different corporate settings, it became apparent that all discourse forms, whether oral or written, were enmeshed in the semiotic web that we called "organisation", or rather, in the process of "organising". A pragmatics understanding of "organising" was "language as action" where work was the writing and speaking that animated organising. By this time, my research had already become markedly hyphenated, in the sense that it had come to rely on exchange with non-academics, on disciplines other than linguistics, on mixed methods, if not methodologies, and on increased contact with cultures other than the British and the Italian. [10]

"Intercultural communication" was home to some of my research work during most of the 1990s and the early 2000s. Within this scholarly tradition, I was hoping to find theories that explained how human beings socialised in different geo-historical contexts and negotiated their positions in business interactions. By then, US crosscultural communication research had produced a large body of literature (for an overview, see, for example: GUDYKUNST & MODY, 2002, especially GUDYKUNST & LEE, 2002; also: TING-TOOMEY, 1994) including theories that sought to explain, and at times (over)simplify, the outcomes of an interplay of often elusive influences and factors. Meantime, in Europe we were doggedly pursuing the discourse route, adding more analyses of recordings painstakingly extracted through relatively hard to obtain contacts with industrial partners. In northern Europe, especially in Finland, collaborative research between academics and industry supported teaching and training programmes in business communication that have become a model for the sector. [11]

Outside Europe, in the 1990s Australia and New Zealand were building a reputation for discourse-based research in organisations while some qualitative American researchers concentrated on comparative analysis of US-Japanese interactions (e.g., MILLER, 1994; YAMADA, 1992, 1997). The "Far East" was still some distance away from the reach of European business discourse analysts until the surge of the economies of South Korea, Hong Kong, Singapore and Taiwan ( the "Asian tigers" phenomenon) brought a new group of countries within their observation range. When (European) business discourse finally met "Asia", in the early 2000s, I and others in the field became aware of pocket of research activities in countries like Malaysia and Japan, and were also alerted to the politics of assimilating very different local perspectives under a postcolonial label such as "Asian Business Discourse(s)" (BARGIELA-CHIAPPINI, 2010). [12]

At this point, "implicating" as a research attitude gave way to "extricating", a critical assessment of the field and of my own involvement in it in the light of the newly-formed links with South and South-East Asian colleagues. [13]

Writing about "culture" as an abstract analytical concept and working with people from "cultures" other than one's own are very different experiences; as different as reading about business communication in textbooks and watching communication "happen" within a multinational company. The culture shock is primarily a difference shock—the difference between one's assumptions or expectations of, for example, what a Chinese manager's job entails, or how a Korean might act in a first meeting with a western partner—and the personal experience of observing western managers at work or in a meeting with their Japanese counterparts. [14]

Cultural stereotypes and prescriptions may be a starting point, if anything to help one be aware of what not to use in intercultural analysis. Beneath the surface of prescribed behavioural repertoires to be found in many textbooks, the more insidious essentialist vocabularies of "culture" and "cultures" must be exposed for scrutiny. The labels "Asian" and "European" may be useful shorthand, but what do they really tell us about the individuals and groups subsumed under them? For example, what are the tacit assumptions behind the "western" indexical used by Malaysian scholars at an international research seminar held in Kuala Lumpur? It is dangerous even to attempt a guess without knowledge of the context of production. The meaning of such form will be different when the same indexical is used in a Japanese business meeting, or a multicultural conference taking place in Europe. [15]

There is little doubt that we will continue to use ambiguous cultural indexicals in everyday speech and writing: their elasticity makes them items of a vocabulary of convenience in many contexts, including academia. In qualitative research, the terminology we use should be a matter of continuous re-evaluation; even if we do not believe in the statement that we are what we say, the unreflective use of language becomes an epistemological challenge whenever we are confronted by different ways of doing and thinking. Geographic "cultures" represent one such domains of embodied difference; but working across social classes in a class-conscious Britain or collaborating with business managers in an industrial setting also pose a challenge engendered by difference. [16]

Extricating oneself from the taken-for-granted value system that we unwittingly support through mind-less use of familiar categories requires systematic stripping of apparently neutral vocabularies. The vocabulary of geographic power positionings, for example, deploys dichotomies such as East(ern)-West(ern), Oriental-Occidental, West-the Rest, North(ern)-South(ern), Asian-American/European etc. Contact with real-life manifestations of "difference" prompts classification of individuals and groups by (our own) categories, in the effort to turn unknown entities into analysable ones. By so doing, we reify the "other" through essentialisms that permit description according to stable features (usually our own). Cultural vocabularies are born, new boundaries are set in addition to often questionable geographic ones and our efforts to understand the strange "other" from our standpoint becomes scholarly research. [17]

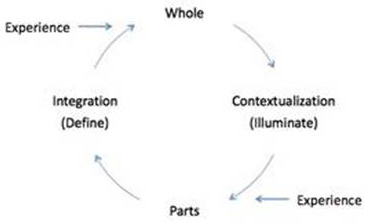

The circulation of knowledge generated in intercultural communication research is largely mono-directional: from west to east and from north to south. We tell others outside our cultural circle, be it the Anglophone circle, or Europe, or the West, how the rest of humanity looks and behaves. What is more, we do so in English, through journals and publishers usually located within our (western) circle of activity (CANAGARAJAH, 2002). The process and challenges of collaborative research across "cultures and languages" seldom appear to be the object of critical reflection (but see BARGIELA-CHIAPPINI & TANAKA, in preparation); provided the (western) standards of scholarship are adhered to in the production of the abstract, the conference presentation, or the article, acceptance will ensue that will confirm our place in the research world. The fact that one or more of the contributors might have had to adapt his or her writing style or mode of thinking or ideological stance to fit with the ideological environment in which the research project is located is not raised as a valid methodological issue. [18]

The process of (self) "extraction" from our own comfort zone, from the discourses with which we surround and protect ourselves and in which we often unwittingly entrap those who may happen to think differently, turning them into foreign "other", requires serious re-examination of the taken for granted quality of our research: its contents, its mode of operation and dissemination, its impact on the people we write about and we write with. It also demands that we look for forms of understanding that allow our "other"—business partner, colleague, co-author, reader—to come to (self-) understanding through the resources available to them in their own socio-historical locales. Rather than proposing western paradigms and theories as benchmarks in comparative and collaborative research, let us listen to what other traditions have to offer us. When we have been given the opportunity to learn from the other, let us not appropriate and expropriate their knowledge; rather, let us preserve what is "true to the other" in the form that the other chooses to share it with us. [19]

We should also always be aware of what is lost in translation: not only in the mediating role of the other but also in our own mediating role as privileged learners. Issues of incommunicability through non-native language use come to mind here. The intercultural communication arena is steeped in multilingualism and whereas language proximity may feed (the illusion of) empathic understanding, for example in cross-European research collaboration, when distant languages co-exist alongside English as a lingua franca, empathy requires a more conscious effort on the part of the participants; in this effort the lingua franca may be both a bridge and an obstacle. How to reach out to the meanings in the other language(s) for which the lingua franca can only provide surface translation is a major challenge. On the other hand, encouraging "native" understanding, however it is perceived and realised by the other, is the second move away from "culturalism", the first being the rejection of essentialist notions of culture-s. The collaborating others, who come from different socio-historical locales and bring to the project their worldviews and their life experience, may be our industrial partner from the other side of town, or our colleagues from Thailand or South Africa. The common language that we develop, which at times will require meaning negotiation in a lingua franca, is one of mutual respect. Respect for what individuals and groups bring to the project also implies questioning dominant disciplinary or ideological paradigms and western research formats of collaboration, knowledge production, and dissemination. [20]

5. Another Way of Understanding "Understanding"

As already mentioned, the process of reading and reflection in preparation to the "whole lives" conference paper led to a critical appraisal of my use of analytical concepts and categories, which many in linguistics and communication studies still take for granted. To reiterate the point, it seems to me that what is required is an appreciation of "difference", which begins with a dialogue with the other in his/her own terms, and seeks to connect self with the others' own understanding of their experience. Interpreting difference—and the different other—becomes possible through an understanding of the other's understanding of self, which in turn leads to renewed self-understanding. [21]

The meeting with (philosophical) hermeneutics as a methodology represents a major landmark in my qualitative journey of discovery; especially attractive is hermeneutics' emphasis on understanding based on the historicity of human experience and the associative processes of interpretation that characterise research in the hermeneutic tradition. I suggested to my co-author, Hiro TANAKA, that we should try to develop our understanding of the concept of "whole lives" from within our own individual "traditions", to use GADAMER's (2004 [1975]) vocabulary, and we could only do so from within the horizons of our personal experience. Disregarding for a moment the almost reluctant e-mail thread, ours was intentionally a "minimalist dialogue" where the research partners do not seek to influence each other's experiential search. The hope behind the self-imposition of "distance" was that it might allow distinct voices to recount personal journeys of discovery; the e-mail trail tells a different story. Curiosity and a bilateral traffic of queries effectively flouted the self-imposed principle of "independent searching". [22]

6. Retelling the End: The Pre-text

As this article makes amply clear, a certain qualitative project—i.e., the conceptualisation of "whole lives" in Japan and in Britain—became a pre-text for personal stock-taking. And the word pre-text is quite appropriate here. The "whole lives" project acted both as a temporary crystallisation of interests and a point of departure for this article; in other words, it worked as a "pre-text". [23]

In the reminder of this narrative, I am finally going to give account of the "whole lives project" in the more formal register of the scholarly article. A joint account is also planned where the voices of the two authors will be give comparable space (BARGIELA-CHIAPPINI & TANAKA, in preparation). [24]

In her monograph, "The Human Condition", the German political philosopher Hannah ARENDT (1906-1975) writes: "No human life, not even the life of the hermit in nature's wilderness, is possible without a world which directly or indirectly testifies to the presence of other human beings" (1958, p.22). The inherent sociality of human life, the awareness of the presence, though not necessarily co-presence, of others in our world shapes our notion of human identity. The lives that each of us are grow out of this condition of co-existence and derive their meaning from it. When we are invited to think about "whole lives", which in the contemporary British social context may be suggestive of certain debates around work-life balance, the first reaction is a terminological question: "whole lives" as opposed to fragmented lives, partial lives, conflicting lives? Lives divided between work and home, or between work and life itself? At the time, the work-life dichotomy struck me as an oxymoron; surely work is part of one's life, whether a person is in employment and/or runs a household? Arguably, the debates in sociology and organisation studies (e.g., MAXWELL & McDOUGALL, 2004; TIETZE & MUSSON, 2005) suggest that work may be swallowing up "life"; there is little "life" left outside paid work for many people in full-time employment; for example, in the case of many women working outside the home and bringing up a family "life" may be lost between periods of paid and unpaid work. [25]

It was probably the vaguely philosophical quality of the concept of "wholeness" that caught my attention in the call for papers launched by the convenors2) of the stream on "Whole lives" for the 6th Critical Management Studies conference (July 13-15, 2009, Warwick, UK). My first move on receipt of the call was to analyse and interrogate the text: Do the convenors truly believe in the validity of this concept? Do they ask potential contributors to believe in it, at least until their abstracts have been accepted? Is it a speculative journey they are enticing us into? Have they reached some kind of landmark in their own personal explorations or experiences of "wholeness"? In other words: What are the convenors' motivations for inviting other colleagues to consider the topic of whole lives? [26]

To balance the ideological overtones of what I thought was possibly a very "western" theme, I invited a colleague with whom I had had the opportunity of spending many hours in conversation on a whole range of research and life issues. Hiromasa TANAKA spent a sabbatical at my former university in the UK and was just the ideal collaborator for a project that required "differing perspectives". The "cross-cultural + cross-linguistic" angle of the proposed joint paper was going to be relatively rare at a critical management studies conference; Hiro's native context of Japan, which is known for a distinctive and pervasive work ethic was an additional relevant facet. [27]

The pragmatician and philosopher of the language John SEARLE in an essay on the ontological primacy of language, observes that

"social ontology is prior to methodology and theory ... in the sense that unless you have a clear conception of the nature of the phenomenon you are investigating, you are unlikely to develop the right methodology and the right theoretical apparatus for conducting the investigation" (2008, pp.443-44). [28]

On starting work on the extended abstract for the whole lives paper, I systematically excluded the interpretive approaches that I had used in earlier projects. The literature on flexi-work, work-life balance and tele-working attracted my attention as possible sources of inspiration for the otherwise elusive concept of "whole lives". Not only did I not find anything particularly relevant in them but it also became apparent that such a concept could have more than one disciplinary home: ethics, philosophy, social theory, sociology, psychoanalysis ... . Additionally, I had suggested to Hiro that we could perhaps try to look for "whole lives" separately, within our respective disciplinary and cultural traditions. On hindsight, this (artificial) attempt to preserve the indigenous nature of the process of conceptualisation, proved impractical. "Intercultural leaks" were inevitable whenever we exchanged emails on impressions, hunches and findings. [29]

7. A European Finding for a European Quest: Meeting (Philosophical) Hermeneutics

While looking up the organisation studies and social theory literatures for "traces" of a western conceptualisation of "whole lives" I came across Hannah ARENDT and her concept of vita activa [active life] and eventually approached her monograph "The Human Condition" (1958). The Latin phrase vita activa attracted my attention for the potential (negative) opposites that it implied. In ARENDT, vita activa was juxtaposed to vita contemplativa [contemplative life], which in turn pointed me to PHILO of Alexandria's essay De vita contemplativa [On the contemplative life]. These preliminary yet significant discoveries left me with two "lives" (active and contemplative) on which to mull over; the temptation was irresistible to bring them together in a complementary tension, similar to the Chinese yin-yang, where the components stand in a creative opposition of interdependence. This process was partly inspired by a meeting with the work of Hans-Georg GADAMER and philosophical hermeneutics (see KINSELLA, 2006). [30]

Philosophical hermeneutics, in the GADAMERian tradition, with its emphasis on interpretation as a dialogic achievement, presented itself as an attractive epistemology for conceptual exploration from a situated, socio-historical vantage point. In the hermeneutic perspective, past and present experiences blend in the stream of unconsciousness, from which they are brought into relevance and significance by new instances of understanding. In GADAMER's language, a new understanding emerges from experiential engagement with "tradition", with what has come before us and in which we are immersed. [31]

Unlike classical approaches to hermeneutics where engagement in dialogue is primarily with the text (cf. GADAMER, DERRIDA and RORTY), in hyphenated re-searching understanding concentrates primarily, though not exclusively, on others' beings, doings and sayings; in this sense, understanding and interpretation are conceived as "practical-moral activities" (SCHWANDT, 1999, p.455), which entail "learning" rather than "reading". The existential, rather than exegetical, quality of understanding as conceived by philosophical hermeneutics, means that all understanding is relational. Finally, a hermeneutic concept of understanding entails the risk of "misunderstanding", and this is because the outcomes of dialogue cannot be predicted. Examining possibilities for failure does not provide criteria for determining the correctness of an interpretation. The researcher therefore can only engage in the "act of construing meaning as risky, situated, disturbing, and relational" (p.463). In so doing, he or she can never be far from experiencing practice-in-the-happening; he/she can never stop understanding while dwelling in the life world. [32]

In hermeneutics, our grasping of what is new in the present depends on what was already understood in the past; the historicity of human understanding is represented by the hermeneutic circle in which a continuous flow of information prevents it from becoming a vicious circle (BENTEKOE, 1996, p.2).

Figure 1: The basic form of the hermeneutic circle (reproduced from BONTEKOE, 1996, p.4) [33]

The hermeneutical inquiry is by definition incomplete because its final and elusive aim is that of understanding the entire world as an integrated world (p.7). [34]

GADAMER's circle has been described as "the constant process that consists of the revision of the anticipations of understanding in the light of a better and more cogent understanding of the whole" (GRONDIN, 2002, p.47). This is a credible graphic description of "re-search-ing", especially, if not exclusively, within a qualitative paradigm, one which captures the endless quality of the re-search-er's task. The exploration of ideas in new projects broadens and deepens the experiential basis but also gives rise to new questions which require branching out into unknown territory in search of answers. In this sense, qualitative researching is naturally interminable and therefore demands humility; it also involves the whole person as well as a suitable methodology (BONTEKOE, 1996, p.10). [35]

As a trained linguist, I found the centrality afforded to language by hermeneutics immediately attractive. GADAMER speaks of the inherent "linguisticality" of interpretation. The role and importance of language in the hermeneutic process of understanding/application/translation, almost equivalent terms for GADAMER (GRONDIN, 2002, p.43), poses continuous challenges to a linguist interpreting verbal interaction as a "foreign" experience; the articulation of understanding can be painfully slow and inadequate. The inadequacy becomes progressively more acute when the interpreter engages with others from different native locales through a lingua franca, usually English. [36]

The linguisticality of interpretation means that the "the listener [is] taken up by what he seeks to understand, that he responds, interprets, searches for words or articulation and thus understands" (p.42). The responsibility resting with the researcher as interpreter and translator is significant: the burden of interpretation in the awareness of its inevitable limits and potential distortion (not always attributable exclusively to language), makes understanding essentially open, as well as risky; continuous learning becomes a necessity of "application" in the sense of the Aristotelian phronesis, or practical wisdom (p.39). [37]

8. Asking "the Question" and "Questioning"

GADAMER notes how the "question" is often used as the guiding principle in research, while the process is either taken for granted or ignored. He goes on to state that in hermeneutics, questioning is an art and as such it cannot be taught (2004 [1975], p.360). GADAMER's reference here is to the practice of dialectic, which involves questioning and seeking truth. Whilst "truth" has long been swept away by the winds of postmodernity, questioning remains the basis of thinking and of a dialectic which does not seek to win over the other but remains open to answers from the other in real dialogue (pp.360-361). [38]

Questioning and dialogue permeate re-search-ing; Socratic dialogue is described by GADAMER (p.361) as the "art of using words as a 'midwife', as facilitator of the expression of opinion". Concepts are formed in dialectics with texts and people "through working out the common meaning" (ibid.). These statements belie the complexity of the hermeneutic enterprise; I would not lay claims to having mastered its rules and resolved its contradictions but the appeal of a dialogic approach to interpretation surpasses hesitation. At the start of my unilateral pursuit of "whole lives", my preliminary value kit consisted of:

The value of dialogue: as a method of discovery of self and of the other;

the value of difference: as an intellectual stimulus for the ongoing conversation (between my co-author and myself);

the value of experimentation: which is only possible as multi-vocality (two or more voices). [39]

With this rudimentary apparatus, I embarked on the task of conceptualising "whole lives" through immersion in tradition, which hermeneutics argues, is the condition for our existence (FREITAG, 2002; GADAMER, 2004 [1975]). [40]

In the experiment of parallel re-search-ing in which Hiro TANAKA and I were looking for our separate narratives for the "whole lives" paper—a somewhat paradoxical approach given the subject matter—the initial question was not "what is 'whole life'?" but rather the twofold "what is whole life in Britain" and "what is whole life in Japan". This further enactment of the hyphenated condition reflects the research approach—each of us independently finding his or her own trajectory while remaining aware of each other's work—but also the presumed existence, if not discovery, of different socio-historically situated forms of "whole life". In hindsight, we asked the "question" (what is whole life?) but did not think of questioning its authenticity, if not indirectly: in the preamble to our parallel abstracts, we said we were going to interrogate the stream convenors' understanding of "wholeness", but eventually did not have the opportunity to do so. A second assumption then was that the convenors (all three working in business schools) were inspired for the title of their stream by the critical MOS (management and organisation studies) literature, which exposes work lives in the West as fragmented, divided, polarised and generally in need of "healing". [41]

This is the assumption on which I based my reflections when preparing to draft the abstract. Hiro and I also exchanged e-mails on some of the findings of the MOS work-life balance literature (e.g., TIETZE & MUSSON, 2005; MAXWELL & McDOUGALL, 2004; KOSSEK & LAMBERT, 2006; GUEST, 2002) in the West and the fewer studies available on "death from over-work" in Japan (karōshi, 過労死)3). The former were found to be too narrow in scope, the latter too specific and lacking socio-cultural depth. Hiro decided to turn to the history of his country, including the history of education and management, for traces of a possible answer to the conditions of work and overwork in Japan. My historical escapade into western history led me quite accidentally to Hannah ARENDT and her conceptualisation of the "active life" to which she gives prominence over the "contemplative life". The "findings" of the two searches are the subject of a separate paper (BARGIELA-CHIAPPINI & TANAKA, in preparation). [42]

The hermeneutic re-search-er is not a privileged individual with superior knowledge or skills. The open-endedness of her/his activity is a constant reminder of her/his human limits but also of the impossibility of any understanding other than in dialogue with others, be they "other" in textual or embodied form. Extended contact with collaborators in the field, company employees or academics, suggests the need for three actions: 1. the demythologisation of the researcher as final arbiter in the process of understanding; 2. the de-professionalisation of re-search-ing as an exclusive activity of trained scholars; 3. the relinquishing of the status of "experts" by academic researchers. [43]

(Self-other-mutual) understanding is an activity between humans, a distinctively human activity is the work of dialogue that we share with others, within and beyond academia. The ethical import of re-search-ing calls for reflection on the process of self-manifestation to the other, which elsewhere I have discussed as an encounter with "difference" (BARGIELA-CHIAPPINI, 2009), and which I would like to extend here to describe the encounter with humanity, to emphasise the commonality that binds the I and the Thou. [44]

In this dialogic framework, temporal frames (past and present) as well as spatial frames (native and non-native experiences) were brought together in the one, "now" space of the "whole live" project, where understanding is conceived as relational and existential. "Familiarity and strangeness are not simply cognitive or rational assessment of aspects of our experience, but ways in which we actually experience being in the world" (SCHWANDT, 1999, p.457). In particular, the experience of "strangeness" as "disorientation, exile or loss" (KERDEMAN, 1998, p.2523, cited in SCHWANDT, 1999, p.457), captures my self-understanding as hyphenated re-search-er, as I move across disciplines for native understandings of "otherness" that can replace the legacy of restrictive and restricting culturalism. [45]

In its practical-moral nature, hermeneutic dialogue does not guarantee the achievement of understanding: misunderstandings and errors are not only possible but likely. The researcher is "construing meaning as risky, situated, disturbing and relational" (SCHWANDT, 1999, p.463) and this is part and parcel of a hermeneutical phenomenology of understanding that cannot be translated into a set of methods and of criteria of opposition of right and wrong. Hermeneutic re-search-ing is a condition of being in the world, a messy, multiple "presencing" that no amount of reflexivity, by self and by others, can make more presentable and easier to write about. [46]

As a researcher trading in reflexivity and self-reflexivity (ROTH, 2001), I have been attracted by experiences of "bricolage" (KINCHELOE, 2001, 2005); I have engaged in cultural acts such as "labelling", in other words, I have participated in "our divided ways of talking about unified natural events" (MOERMAN, 1988, p.33). The apparent solidity of the researcher's self-positioning, like the apparent solidity of everyday reality as seen through the anthropological gaze, "stems from the shoring up and re-plastering we constantly give it as we talk about the world and inspect it for the materials that talk requires. Beneath our busy scaffolding there may be nothing at all" (p.120). [47]

The experience of dissolution of the researcher in the act of "re-search-ing"—when the research object seems to be fading from sight and the research design is no longer anchoring the labour of understanding—is an aspect of the dynamic and fuzzy ontology of hyphenated researching. Consequently, the language of re-search-ing is less reassured and reassuring, less prescriptive and more questioning: it reflects the shift from research as application of methodology(ies) to research-ing as "understanding", where understanding is an existential philosophy (SCHWANDT, 1999). [48]

In the dialectic of explanation and understanding (ROTH, 2001) in which Hiro TANAKA and I were caught up, the initial explanatory assumption of the "cultural difference" separating us showed up as limiting, if not spurious. Clearly, our frames of reference, world-views, shared assumptions etc. were, and largely remain, different but in the course of our collaboration something describable as incremental "intersubjective understanding" (SCHROER, 2009) took place. Within this new and evolving condition, hyphenation is experienced as a creative tension, seeking to preserve subjectivities-in-contact, valuing sparks of intuition and puzzling over, while accepting, incomplete or, at times, failed understanding. Perhaps the most cutting yet sobering realisation of the hermeneutic experience is the un-attainability of the other's (and of self-) awareness that accompanies the inevitability of dialogue. [49]

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Hiro TANAKA for his comments and questions on an earlier draft of this paper. I am also grateful to the anonymous reviewers whose suggestions have helped me realise that I was trying to write two papers in one.

1) In his 1995 monograph, Karl WEICK writes: "To talk about sense-making is to talk about reality as an ongoing accomplishment that takes form when people make retrospective sense of situations in which they find themselves and their creations. There is a strong reflexive quality to this process. People make sense of things by seeing a world on which they already imposed what they believe" (p.15). <back>

2) Incidentally, three female convenors, all of which involved in research on work ethics, although from different epistemological angles. <back>

3) The phenomenon of karōshi, glossed as "work to death" (KANAI, 2008, p.209) has been documented since the 1980s and is a "potentially fatal syndrome resulting from long work hours". See also ONO (2003) and TUBBS (1993), among others. <back>

Arendt, Hannah (1958). The human condition. Chicago: Chicago University Press

Bargiela-Chiappini, Francesca (2009). Introduction: Business discourse. In Francesca Bargiela-Chiappini (Ed.), The handbook of business discourse (pp.1-15). Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Bargiela-Chiappini, Francesca (2010/forthcoming). Asian business discourse(s). In Jolanta Aritz & Robyn Walker (Eds.), Discourse perspectives on organizational communication. Madison, NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press.

Bargiela-Chiappini, Francesca & Tanaka, Hiromasa (2009). Conceptualising "whole lives" across cultures and languages: An experiment in dialectic. Paper delivered at the 6th International Critical Management Studies Conference, Warwick (UK), July 13-15.

Bargiela-Chiappini Francesca & Tanaka, Hiromasa (in preparation). Conceptualising whole lives: An experiment in undeclared dialogue.

Bontekoe, Ronald (1996). Dimensions of the hermeneutic circle. Atlantic Highlands, NJ: Humanities Press International.

Canagarajah, A. Suresh (2002). A geopolitics of academic writing. Pittsburgh, PA : University of Pittsburgh Press.

Freitag, Michael (2002). The dissolution of society within the "social". European Journal of Social Theory, 5(2), 175-198.

Gadamer, Hans-Georg (2004/1975). Truth and method (2nd ed.). London: Continuum.

Grondin, Jean (2002). Gadamer's basic understanding of understanding. In Robert J. Dostal (Ed.), Cambridge companion to Gadamer (pp.36-51). West Nyack, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Gudykunst, William B. & Lee, Carmen M. (2002). Cross-cultural communication theories. In William B. Gudykunst & Bella Mody (Eds.),The handbook of international and intercultural communication (pp.19-23).Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Gudykunst, William B. & Mody, Bella (Eds.) (2002). The handbook of international and intercultural communication. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Guest, David E. (2002). Perspectives on the study of work-life balance. Social Science Information, 41, 255-279.

Kanai, Atsuko (2008). "Karoshi (Work to death)" in Japan. Journal of Business Ethics, 84(2), 209-216

Kincheloe, Joe L. (2001). Describing the bricolage: Conceptualizing a new rigor in qualitative research. Qualitative Inquiry, 7(6), 679-692.

Kincheloe, Joe L. (2005). Critical constructivism. New York: Peter Lang Publishing.

Kinsella, Elizabeth A. (2006). Hermeneutics and critical hermeneutics: Exploring possibilities within the art of interpretation. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 7(3), Art. 19, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs0603190.

Kossek, Ellen & Lambert, Susan (Eds.) (2006). Work and life integration: Organizational, cultural and individual perspectives. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Maxwell, Gillian A. & McDougall, Marilyn (2004). Work-life balance. Public Management Review, 6(3), 377-393.

Miller, Laura (1994). Japanese and American indirectness. Pragmatics, 4(2), 221-238.

Moerman, Michael (1988). Talking culture. Ethnography and conversation analysis. Philadelphia: University of Philadelphia Press.

Ono, Masakazu (2003). Karoshi karou jisatsu no shinri to shokuba [Psychology and workplace of Karoshi and Karo-suicide]. Tokyo: Keikyu-sha.

Roth, Wolff-Michael (2001). Review essay: The politics and rhetoric of conversation and discourse analysis. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 2(2), Art. 12, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs0102120.

Schröer, Norbert (2009) Hermeneutic sociology of knowledge for intercultural understanding. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 10(1), Art. 40, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs0901408.

Schwandt, Thomas A. (1999). On understanding understanding. Qualitative Inquiry, 5(4), 451-464.

Searle, John (2008). Language and social ontology. Theory and Society, 37(5), 443-460.

Tietze, Susann & Musson, Gill (2005). Recasting the home-work relationship: A case of mutual adjustment? Organization Studies, 26, 1331-1352.

Ting-Toomey, Stella (Ed.) (1994). The challenge of facework: Cross-cultural and interpersonal issues. SUNY series in human communication processes. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Tubbs, Walter (1993). Karoushi: Stress-death and the meaning of work. Journal of Business Ethics, 12(11), 869-877.

Weick, Karl E. (1993). The collapse of sensemaking in organizations: The Mann Gulch Disaster. Administrative Science Quarterly, 38, 628-652.

Weick, Karl E. (1995). Sensemaking in organization. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Yamada, Haru (1992). American and Japanese business discourse: A comparison of international styles. Norwood, NJ: Ablex Publishing Co.

Yamada, Haru (1997). Why American and Japanese misunderstand each other. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Francesca BARGIELA is currently working on a co-authored monograph entitled Researching Practice as it Happens (Sage). She is honorary associate professor at the University of Warwick, UK.

Contact:

Francesca Bargiela

The Centre for Applied Linguistics

University of Warwick

Coventry

CV4 7AL

UK

E-mail: f.bargiela@warwick.ac.uk

Bargiela-Chiappini, Francesca (2010). Hyphenated Research [49 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 12(1), Art. 2, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs110122.