Volume 11, No. 2, Art. 35 – May 2010

Visualising Social Divisions in Berlin: Children's After-School Activities in Two Contrasted City Neighbourhoods

Olga den Besten

Abstract: The article raises the issue of interconnectedness of social and spatial divisions, and addresses this issue through considering the phenomenon of urban segregation. The study explores children's and young people's experiences in two socially contrasted neighbourhoods in Berlin through subjective maps drawn by the children. The article focuses on major differences between children's representations of their "subjective territory" in the two segregated areas. Such territory looks larger and better explored in the drawings of children from a socially advantaged area, who picture a dense network of after-school "enrichment" activities and friends' homes. In contrast, children, mostly migrant, from a socially disadvantaged area depict rather few places for spending time after school, one of the most important of them being a free-access youth club. The article argues that children's social exploration of their neighbourhood is activity-bound and depends on financial resources and cultural capital available to these children.

Key words: migrant children; social divisions; visual methods; subjective maps; children's drawings; activity theory; urban segregation

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. Putting Social Divisions on the Map (of a City)

3. Divided Childhoods

4. The Study: The Choice of Locations and Sampling

5. Research Methodology and Methods

5.1 Children's subjective maps: Advantages of the method and the procedure

5.2 Methodological limitations and solutions

5.3 Methods for the analysis of children's subjective maps

6. Results and Discussion

6.1 Places for after-school activities of children in Kreuzberg

6.2 After-school activities and networks of children in Zehlendorf

7. Conclusions

During the years which have followed the fall of the Berlin wall in 1989, Berlin has been on the road of turning from a "divided city" into a "fragmented city" (HÄUSSERMANN & KAPPHAN, 2000/2002, 2005). This means that the pre-1989 major division of Berlin into Eastern and Western parts, whose political and economic systems were opposed to each other, has been gradually replaced by "fragmentation"—the division of the city into several areas different in their socio-economic characteristics. Still, this process of fragmentation is largely based on the socio-spatial inequalities existing prior to 1989, like the concentration of arriving "guestworkers" (labour migrants) towards the end of 1960s only in certain neighbourhoods of West Berlin. Today such city "fragments" are constituted by the advantaged city suburbs, on the one hand, and a growing concentration of disadvantaged groups in the inner city plus several social housing estates in the eastern part, on the other hand. Authors consider this "fragmentation" to be even more significant nowadays than the remaining socio-economic division between East and West Berlin (see e.g. SLEUTJES, 2008). [1]

Berlin, like other major Western European cities, is also particularly interesting for research on social divisions and migration because of the diversity of types of international migration that are present there. For example, along with children and grandchildren of Turkish labour migrants who came to Germany in the 1960s-1970s, there are also young immigrants of the more recent wave of migration from the Soviet Union, as well as children from high-skilled "transnational" families. Certainly, some groups of migrants are more or less privileged than others, and this is reflected also on the spatial level—city areas where this or that migrant group is concentrated. This article draws on a qualitative research which has explored experiences of children from several school classes in two contrasted urban areas of Berlin, where two socially different groups of migrants reside. To explore children's subjective geographies of their neighbourhoods—and through them, the children's social world—this research uses the method of participant-drawn maps. [2]

2. Putting Social Divisions on the Map (of a City)

This article utilises the definition of "social division" as "a classification of a population (i.e. taxonomy of persons) and a range of systematic social processes which relate to that taxonomy, and which then serve to produce socially meaningful and systematic...practices and outcomes of inequality" (ANTHIAS, 2001, p.837). Although Floya ANTHIAS admits that the term "social division" is very broad and can include many types of "difference" such as age, health, religion, styles of life etc., she argues that it is class, gender and ethnicity that are "the primary divisions from the point of view of stratification in modern societies" (p.843). Of course, the impact of social divisions on human life is multi-dimensional, as "people do not only have a class, or only a gender, or only an ethnicity. They have all these things at the same time, and lots of other social characteristics too" (PAYNE, 2007, p.907). It is in various spheres of human activity that the impact of social divisions—"practices and outcomes of inequality"—can be seen and studied. One of such spheres where inequality reveals itself is the spatial arrangement—in our case, spatial segregation of areas in one city. [3]

Segregation is seen as a very complex, multi-faceted phenomenon (see MASSEY, WHITE & PHUA, 1996; GORARD & TAYLOR, 2002). JAMES and TAEUBER define segregation as "the differential distribution of social groups among social organizational units" (1985, p.24). Speaking about residential segregation—which is the case of my research—this means uneven distribution of social characteristics, such as ethnicity and class, between different urban areas. In Berlin, several inner-city areas are known for a particularly high concentration of an immigrant population, whose ethnicity is different from the dominant one in Germany. In southern Kreuzberg, northern Neukölln, northern Wedding, western Tiergarten and northern Schöneberg such a population reaches 30 per cent (SLEUTJES, 2008, p.75). At the same time, in the western suburbs the share of the immigrant population does not exceed 10 per cent (ibid.). These areas also have particularly high rates of unemployment. In Kreuzberg, for example, more than 12 per cent of the whole population and one third of the immigrant population is unemployed (HÄUSSERMANN & KAPPHAN, 2000/2002). The choice of locations for the study—two socially contrasted areas of Berlin—is explained further on. [4]

This study views children's and young people's immediate geographical environment—such as, in this case, their neighbourhood—as a concrete site of their everyday practices and social interactions which forms their competencies and shapes their worldview (see e.g. FORSBERG & STRANDELL, 2007; ROSS, 2007; HANCOCK & GILLEN, 2007; PIKE, 2008; DEN BESTEN, forthcoming/2010a). In this, it relies on the academic literature in sociology of space, childhood studies, and children's geographies—an interdisciplinary field which has developed out of a subdiscipline of human geography. [5]

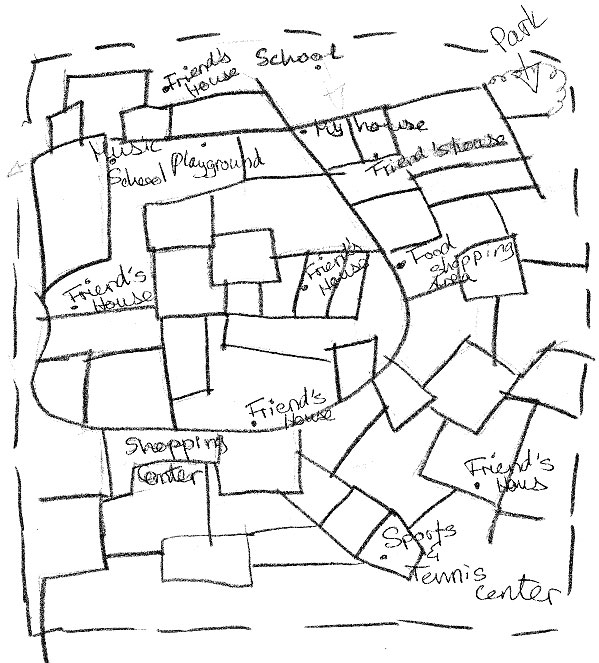

There has been increasing attention in childhood studies to the research of diverse childhoods on various scales: local, national, and global, as well as at cross-overs and intersections between them (see, for example, the seminal work of: KATZ, 2004; NÍ LAOIRE, CARPENA-MÉNDEZ, BUSHIN & WHITE, 2010/forthcoming). Numerous research efforts have been put into studying childhood from a comparative perspective (see, for example: CHISHOLM, BUECHNER, KRUEGER & BROWN, 1990; DU BOIS-RAYMOND, SUNKER & KRUEGER, 2001; OLWIG & GULLØV, 2003). Children's experiences in different countries and cultures have been compared to each other. Within these efforts, attempts have been made to explore a variety of childhoods co-existing within one country or even within one city. Such literature sheds light on social distance between different groups of children and young people, which often coincides with spatial distance, and vice versa. For example, drawing on the case of Berlin (before the re-unification), authors write that "[e]thnic minorities live on the margins of West German society, with few links into the indigenous culture" and that "West German children rarely have much contact with minority group children unless they live in specific areas (for example, Kreuzberg in West Berlin) ..." (CHISHOLM et al., 1990, p.2). The assumption that this article makes is that growing up in segregated urban neighbourhoods—whose population is different in social, economic and cultural terms and whose architectural and infrastructural fabric is also different—may mean having very different childhoods and prospects for the future. [6]

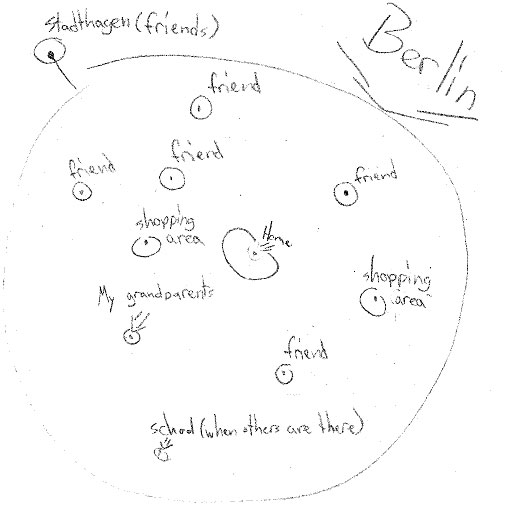

4. The Study: The Choice of Locations and Sampling

This article compares children's experiences of their neighbourhoods in two segregated contrasted administrative districts of Berlin: Kreuzberg and Zehlendorf. The choice of these two contrasted neighbourhoods relies mostly on statistical and descriptive information on these areas in the literature. [7]

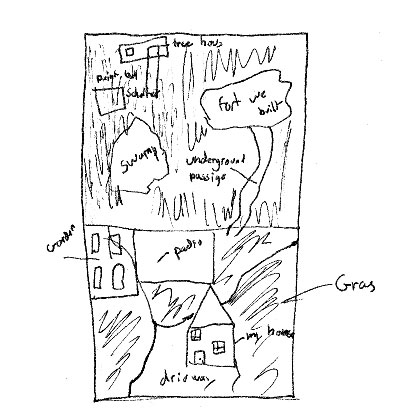

The contrast between the two areas is best summarised by describing them as "advantaged" (Zehlendorf) and "disadvantaged" (Kreuzberg). Kreuzberg (see Plates 1a and 1b) is an inner-city district in West Berlin which historically used to be a lower-middle-class neighbourhood. Since the end of the 1960s, it has become home for immigrants from several waves of migration, mostly from Turkey, starting with the "guestworkers" (HÄUSSERMANN & KAPPHAN, 2005). Although parts of Kreuzberg have recently been undergoing a process of gentrification, the particular micro-area where the research was carried out—Wrangelkiez—scores poorly on indicators of social well-being, such as; unemployment rate, poverty level, life expectancy rate, and level of education (BERLINER SENATSVERWALTUNG FUER GESUNDHEIT, SOZIALES UND VERBRAUCHERSCHUTZ, 2004). As an area in difficulty, it has also been targeted by the "District with Special Development Needs—the Socially Integrative City" programme initiated by the Department of Urban Development of the Senate of Berlin.1) [8]

At the same time, Kreuzberg looks idyllic (see especially Plate 1a). As the ECONOMIST (2008, p.31) has described it, "[h]eavily Turkish Kreuzberg, once on the periphery of West Berlin and now at the centre of the united city, feels more like Greenwich village than the South Bronx ..." But, as the article goes on, "migrants and Germans lead largely separate lives" and inequality is transmitted by the education system. There is a high proportion of immigrants in Wrangelkiez (ibid.). In this area, the study was conducted in two schools—a primary school and a secondary one. The pupil population of both schools is predominantly (up to 100 per cent) of foreign origin, mostly from Turkey, but also (about 15 per cent) from Arabic countries, according to the school statistics provided by the head teachers (see also BECKMANN, 2004). The secondary school is Oberschule—one of the disadvantaged types of school in Berlin. Wrangelkiez is often associated in the press with incidents of violence and conflicts between delinquent immigrant youths and other local populations as well as the police (see e.g. KOPIETZ, 2006; PLARRE, 2006; SOBOSZYNSKI, 2006).

|

|

|

Plate 1a (left) and Plate 1b (right): Kreuzberg, Wrangelkiez (Source: author) [9]

The contrasted area—Zehlendorf—is an outlying district in the south-west of Berlin. The micro-area around the school where the study was carried out has a distinctive suburban look, with spacious single-family houses and gardens (see Plate 2). Zehlendorf also has vast public green spaces renowned for their natural beauty, such as the Grünewald forest. Since reunification, Zehlendorf has become one of the areas for suburbanization—a process which was not characteristic of Berlin before (HÄUSSERMANN & KAPPHAN, 2005). The school that took part in the study is a bilingual school. During the Cold War, Zehlendorf was one of the areas in West Berlin where American forces were centred, and nowadays it is still home to many American expatriates. According to the school's statistics, 57 per cent of its pupils are German citizens, 33 per cent American, and the other 10 per cent come from various countries. Languages of instruction in the school are both German and English, and the school is of a university-preparatory type (Gymnasium), as opposed to the above-mentioned school in Kreuzberg. According to the children's and parents' questionnaires used in the study, most of the children come from families who live in their own rather large houses. A prevailing majority of children have their own room, in contrast with the children in Kreuzberg.

Plate 2: Zehlendorf (Source: author) [10]

This article draws on a part of the data which was obtained by the author in October-December 2006. This particular part of the data set is built with the purpose of comparing children's perceptions of their neighbourhoods in two contrasted areas of Berlin. On the whole, this set contains questionnaires and drawings of 103 Berliner schoolchildren (see Table 1). The pupils who took part in the study were either in their last year (or, in one case, two last years) of primary school, or in the first year of secondary school. This way, the sampling has focused on children/young people of the age range of mainly 11-13 years old—the age which many children's geographers consider as the one by which basic environmental competencies (or "street literacy"—see CAHILL, 2000) have been acquired and a certain level of "outdoor spatial freedom" (see DEN BESTEN, forthcoming/2010b) has been achieved by the large majority of children/young people. At the same time, such sampling was destined to capture the experience of the transition period from primary to secondary school. Because of this age range between childhood and adolescence, I refer to the research participants as "children/young people".

|

City area Level of schooling |

Kreuzberg (a "disadvantaged" area) |

Zehlendorf (an "advantaged" area) |

|

Primary |

A class of 23 pupils (11-12 years old) |

A class of 24 pupils (10-11 years old) and a class of 23 pupils (11-12 years old) |

|

Secondary

|

A class of 16 pupils (13 years old) |

A class of 17 pupils (12-13 years old) |

Table 1: The sampling: distribution of the schoolchildren by area and level of schooling [11]

5. Research Methodology and Methods

5.1 Children's subjective maps: Advantages of the method and the procedure

The main method used in the research is subjective maps—also called "cognitive" or "mental" maps. Many studies in children's geographies and childhood research more generally are based on maps drawn by children. Children's subjective maps have been widely utilised not only to reveal children's environmental competence (see MATTHEWS, 1992), but also to determine what places are important to children and how they use city spaces (e.g. HALSETH & DODDRIDGE, 2000; TSOUKALA, 2001, 2007; YOUNG & BARRETT, 2001a, 2001b; HOERSCHELMANN & SCHAEFER, 2005; ELSLEY, 2004). The map-drawing activity is a fun, "task-oriented" method (PUNCH, 2002) and is situated within child-centered and "child-friendly" research methodologies (e.g. BARKER & WELLER, 2003). Most children in the study enjoyed drawing the maps, although there were a few children who chose to write words instead of drawing. Moreover, using children-produced maps solved a methodological issue raised by YOUNG and BARRETT (2001a, 2001b): that for a researcher as an outsider it is almost impossible to observe directly—through ethnographic fieldwork—children's use of city spaces. A systematic observation of a particular group of children in a public space would be problematic in terms of access and ethics. Most importantly for this study, the method of mapping has proved appropriate in doing research with immigrant children. Children in the study were of diverse ethnic backgrounds and many of them did not speak, read or write the language of the recipient country or the researcher's language(s) well enough to be interviewed. [12]

In the present study, children were asked to produce two maps: first, to draw their way home from school and all the objects that attracted their attention on the way. This task was chosen because all the children went to school, so the way home from school was their everyday, routine trajectory (see also ROSS, 2007). Coming back home from school was chosen because of the supposedly more relaxed, unhurried character of this trajectory and more opportunities for deviations from this way, like, for example, popping in to shops or playing in a park after classes. Second, the children were asked to draw their "neighbourhood" or "territory", i.e. a city area which they knew rather well and where they "felt at home". This drawing activity was done at school during one lesson. As in the study by HOERSCHELMANN and SCHAEFER (2005), children were given a relatively free range regarding how to draw their maps, and their locational accuracy was not considered to be important. This paper draws mostly on the maps produced through accomplishing this second task—that is, on the drawings of the children's subjective territory. [13]

To obtain data on the children's "micro-geographies of emotions"—their emotional perception of their neighbourhoods (see DEN BESTEN, forthcoming/2010a)—I introduced what I called "emoticons". These are special symbols which would be used by children to mark their visual representation of a place with a certain emotional attitude. Four "emoticons" were used in the study: children were asked to use a symbol of a heart to mark places they liked, a big dot to mark places where they hang out, a cross inside a circle to mark places they disliked, and finally, a square to mark places they fear. [14]

5.2 Methodological limitations and solutions

A major limitation of visual methods considered by a number of authors is the possibility that the researcher would rely too heavily on his or her own interpretation (see YOUNG & BARRETT, 2001a, 2001b; HOERSCHELMANN & SCHAEFER, 2005). The most common solution to this issue is to use a verbal backup along with the visual data. Most often it is the post-drawing interview that is used as a means to generate the respondent's explanation of the drawing, and to confirm or reject the researcher's initial interpretation of the visual material (see e.g.: KUHN, 2003). In this research, such a verbal backup was a short questionnaire accompanying the drawing, as well as the children's labelling the objects pictured on their drawings/maps directly beside those objects. A more detailed explanation of this procedure is as follows. The children drew their maps on a piece of standard A4 paper as part of a questionnaire. On the next page of the questionnaire, they were asked to explain why they liked, disliked or feared the places they had marked on their maps. Verbal explanation proved very useful to help understand the exact meaning and function of objects pictured on children's maps. The questionnaires were in German or English, depending on the official language of the class. Children attending a bilingual class could choose to fill in the questionnaire in either of the languages (for example, children in bilingual classes in Berlin could choose between German and Russian, or German and English). Children's answers, quoted in the results, were either translated into English by myself or originally given in English. [15]

Moreover, the children's questionnaires were incorporated into a broader ethnographic work, which included observations in the urban areas and in the schools, as well as talking informally to pupils, teachers, and some parents (parents also completed their own questionnaires). These ethnographic observations have also been useful for the interpretation of children's maps and I refer to them in the discussion of results. [16]

A potential limitation of what concerns studying socio-spatial divisions can be found in the way of setting the drawing task for child-research participants. One thing is that the problem of "social divisions" may be too abstract for children to address; and when it is translated as various "everyday" descriptions of the outcomes of inequalities, this may raise an ethical problem. As an example, should children be asked to draw parts of the city or their neighbourhood where they do not go, because they feel "different"? Such a question risks raising (perhaps false) awareness of their difference, bringing some painful reflections or even leading to conflicts with their peers inside the class. If such a task is set, it should be accompanied by a solid and accessible explanation of the subject and the possibility of psychological work with the child afterwards. So, in my opinion, it is better to find out about socio-spatial divisions indirectly and by framing questions in a more general and positive way, for example: "Please draw an area in your neighbourhood, which you know well and where you feel at home (even if you are outdoors)." Therefore, this study is close to using children's drawings of their area as a projective technique, assuming that children's usual activities and related feelings are "projected" onto their subjective maps. [17]

5.3 Methods for the analysis of children's subjective maps

In this study, the main method of analysis of children's mental maps is inspired by activity theory. In this, I am following Kiryaki TSOUKALA (2001, 2007) who applied this theory to the study of children's subjective maps. Activity theory originated in the Soviet Union in the 1920s in the works of Lev VYGOTSKY (see e.g.: 1962) and was developed, in particular, by Alexei LEONTIEV (see e.g.: 1975, 1979). According to this theory, human consciousness is developed through activity, which is object- and goal-oriented, and can be internal (mental) or external. Human activity is profoundly social, so that even when a person is not engaged in an activity with anybody else at a given moment, his or her activity is mediated by the society's symbolic tools (e.g. language). For our analysis, this implies that children choose to draw a particular object or place on the subjective map because they have had a certain experience with it. Let us take, for example, the most widespread element of children's maps (in the author's data set): a park or a public garden. According to the children's questionnaires, most of them like such places because they play there or "just" hang out and communicate with their peers. Even if they like the place because of its aesthetic values, that means that they have been engaged in an activity—that of mental comparison of shapes, colours and symbols, for example. The character of activity will give us information about the character of the children's sense of belonging to their locality—their socio-spatial connections and their personalised use of space (see DEN BESTEN, forthcoming/2010a). [18]

In practice, the qualitative analysis of the children's drawings in this study proceeded as follows. All the elements of the children's maps representing particular places or objects were grouped into categories, such as architectural landmarks, cafés and stadiums. For the purposes of this paper, the drawings of both groups of children (from Kreuzberg and Zehlendorf) were checked for the elements that are only present in one group, but not in the other. For instance, a youth club was drawn and mentioned in the questionnaires of children in the Kreuzberg group, but not the Zehlendorf group. And on the contrary, a friend's house appears on the maps of children from Zehlendorf, but not from Kreuzberg. Comparing children's activities in the two groups, this paper draws on such contrasts between these groups and not on what they have in common (this would be, for example, the representations of shops, parks, home, and school). Each individual place or object was also carefully studied in relation to other objects on the map. There was constant cross-checking between the two types of data: visual (the drawings) and verbal (the questionnaires) to find out, for example, why this or that place had been marked with the "emoticon" of like, dislike or fear. Beside such analysis on the level of one element of a map, maps were also studied as a whole, from the point of view of their structure: how the elements are organised on the map, how they are distributed and interconnected. [19]

6.1 Places for after-school activities of children in Kreuzberg

When undertaking the task of mapping their subjective territory, or neighbourhood, children/young people in Kreuzberg often picture one place, and sometimes two or three. For many of the boys a football ground is often mentioned (Figure 1a, see also Figures 1b and 3a). As is evident from the children's questionnaires, such a place is associated with one major activity, so this type of map can be called a "mono-activity map". A 12-year-old boy, self-reportedly German, pictured a football field and a mosque within a confined territory (Figure 1b). In his questionnaire, he confirmed that he "has training" on the football ground, "reads Koran" in the mosque and is "attracted by the cinema"—which is pictured just outside the borders of his subjective territory—because "there are good films".

|

|

|

Figure 1a (left) and 1b (right): Subjective maps of "territory" of boys aged 11 (left) and 12 (right) in Kreuzberg. Source: author's data set [20]

Another type of drawing of children/young people from Kreuzberg that can be distinguished reveals a theme of conflict arising from the absence of places where children could engage in age-appropriate activities. A 13-year-old girl of Turkish origin writes that she does not like a certain square with a playground in it "because there are a lot of small children". However, she still makes a rather detailed drawing of the playground (Figure 2a). She obviously knows the place quite well and would like to spend time there. The decision to draw the place, which, according to the girl, she dislikes, can be indicative of the fact that there is no other public place in her living area where a girl of her age can and wants to spend her free time. Similarly, a 12-year-old boy of Turkish origin says that he does not like a disco and a nightclub in his area because he is not allowed in, but he draws them nevertheless (Figure 2b).

|

|

|

Figure 2a (left) and 2b (right): Drawing 2a (by a Turkish girl aged 13 in Kreuzberg) features a playground, with a slide, swings, and sand; drawing 2b (by a Turkish boy aged 12 in Kreuzberg) shows his "way to school" with the school in the foreground, the building where he lives and a park that he likes, as well as a disco and a nightclub marked with the "emoticon" of dislike (Source: author's data set) [21]

Some drawings made by children/young people in Kreuzberg feature an object which does not appear anywhere else in the data set—a youth club (Jugendklub) (see Figure 3a). In their questionnaire, 12- and 13-year-olds from Kreuzberg write that in youth clubs, they can hang out after school, play table tennis and table football, and talk to each other. Other research has also found that youth clubs are a key place for disadvantaged youth in Germany (HOERSCHELMANN & SCHAEFER, 2005), although as these authors write (and my data confirms), young people "almost never do anything meaningful there" and "do little more than playing games or chat" (p.229). I would argue, however, that "just" chatting to each other is a meaningful activity, especially for teenagers. In this age range, communication with peers is a leading type of activity which influences adolescents' identity formation. Moreover, in the absence of other opportunities for leisure and extracurricular learning, free youth clubs are a valuable resource for disadvantaged youth. Previous research (REN, 2006) also highlighted the high social importance of public youth clubs for young immigrants in Berlin. REN writes about the important role of youth clubs in the development of a "Berliner identity", which, although different from a cosmopolitan identity of children from the Zehlendorf school (ibid.), helps children overcome ethnic boundaries (for example, it is in these clubs that Turkish, Arabic and German children get to communicate and to play together).

|

|

|

Figure 3a (left) and 3b (right): Drawing 3a (by a Turkish boy aged 14 in Kreuzberg) features a youth club and a football field; drawing 3b (by a 13-year-old girl from Syria living in Kreuzberg) shows an Internet café. Source: author's data set. [22]

On the structural level, what is characteristic of the maps of the children/young people in Kreuzberg is the "islandic" nature of the places drawn on them. The football-playing grounds (Figures 1a, 1b and 3a), the mosque (Figure 1b), the youth club (Figure 3a) and the Internet café (Figure 3b) are all pictured as if they were in the middle of nowhere and as if there were no roads or other links connecting them to each other or to other infrastructure in the area. The children's questionnaires show that by putting a football ground or a youth club on their maps, the children have particular places in mind. This type of representation of a place for an activity as isolated and unconnected, has been mentioned by Colin WARD who has called such places "islands of activity" (WARD, 1990 [1978], p.29) and by ZEIHER who has called them "islands on the map of the city" (ZEIHER, 2003, p.66). [23]

6.2 After-school activities and networks of children in Zehlendorf

Contrary to the children/young people from a disadvantaged neighbourhood in Kreuzberg, the children/young people from a bilingual school in Zehlendorf (an advantaged neighbourhood) draw designated places for specialised after-class learning activities, like a music school (Figure 6), a skate park, a tennis centre (Figure 6), and a horse-riding ground (Figure 4). This can be explained by the fact that these children engage in various extracurricular activities, as their parents consider this important and have the financial means to provide their children with supplementary learning. This is evident from the parents' questionnaires used in the study and is also reflected in other studies of middle-class parents. For example, VINCENT & BALL write about "the enthusiasm for "enrichment" activities, extra-curricular sports and creative classes in which respondent families enrolled their children" (2007, p.1062) with the "parent presenting a myriad opportunities and support for the child to have a range of learning experiences" (p.1065; see also LAREAU, 2002). The authors come to the conclusion that activities play an important role in parental strategies for class reproduction.

Figure 4: A map of her "subjective territory" by a 13-year-old German-American girl from the school in Zehlendorf (Source:

author's data set) [24]

Another frequently-drawn object on the maps of children in Zehlendorf is a friend's house (see Figures 4-6). Some children even indicated several friends' houses on their maps (Figures 5 and 6). This, together with places for after-school activities and play, makes a picture of the dense social networks that these children have. The "islands of activity" on their maps are connected to each other by transport roads (Figure 4) or otherwise interconnected (Figure 6). On the whole, as in the findings of HOERSCHELMANN and SCHAEFER, mental maps of these children from an advantaged neighbourhood "show a wide selection of places across the city and beyond" (2005, p.231) as opposed to the "narrow activity space" (p.230) of youth from disadvantaged areas, such as, in our case, young immigrants in Kreuzberg. I would disagree with HOERSCHELMANN and SCHAEFER, however, that such youth necessarily have an alternative to this "withdrawing into a narrowly confined local space" (p.237), because most "meaningful" (as these authors put it) extracurricular courses and activities are costly (see also VINCENT & BALL, 2007, p.1068).

Figure 5: A drawing of her "subjective territory" by a 10-year-old German girl from Zehlendorf (Source: author's data set)

[25]

The subjective maps of schoolchildren from Zehlendorf depict a larger territory than those of children in Kreuzberg. This is clear through a comparative analysis of "objective", geographical maps of the neighbourhoods and children's drawings of them. Sometimes the children's drawings are enough to establish this. For example, Figure 4 shows that the teenage German-American girl who studies in the school in Zehlendorf, uses the space in different administrative districts in Berlin (Kreuzberg and Zehlendorf) and outside of them (Brandenburg), and is engaged in a specific activity in each of these areas. Similarly, a 10-year-old German girl represents entire Berlin as her "subjective territory" (see Figure 5). Her Berlin is full of friends (with friends living in a suburb outside as well) with her home being the centre of this universe. It also contains her grandparents' home, her school and two shopping areas.

Figure 6: A map of the "subjective territory" of a 12-year-old English-German girl living in Zehlendorf (Source: author's

data set) [26]

A new element, which appears only on the maps of the children in Zehlendorf, is the drawing of their own garden (see Figure 7). Indeed as families of these children live in private houses, gardens are a very safe and enjoyable place to play for the children. One girl wrote that she likes her garden because "it's overgrown and adventurous". This allows the children not only to imaginatively use their environment, but also to change it; for example, the children draw "tree houses" that they build in their gardens (Figure 7). Moreover, as the children's drawings and questionnaires have shown, the environment outside of private family space in Zehlendorf is also favourable to children's exploration. One girl drew "little posts perfect for leapfrogging" on her way to the playground; another girl—a "Womping Willow—a large tree good for climbing"; and a boy drew a "fort we built" in the neighbouring wood (Figure 7).

Figure 7: The "subjective territory" of a German boy from Zehlendorf (13 years old) (Source: author's data set) [27]

This paper has explored children's experiences in two socially contrasted districts of Berlin and studied children's complex "micro-geographies" using the method of subjective maps. Activity theory served as a framework for the analysis of the visual data. The analysis has mostly focused on the type of the places/objects that the children chose to draw to represent their "subjective territory". The children also often marked places/objects on their maps with an "emoticon" which has helped in understanding the children's emotional experiences with these places or objects. [28]

The results of the study confirm that children's socio-spatial worlds are different in the two segregated city areas. Depending on the area where they live—which corresponds to the social status of the families where they are being brought up—children have different access to resources. For example, while children from expatriate or binational (mostly German-American) families in the Berliner district of Zehlendorf are engaged in enriching extracurricular activities (including such expensive sports as horseback riding), second-generation immigrant children of mostly Turkish origin living in Kreuzberg struggle to find a place for an activity that would be interesting and challenging enough for their age. This difference is reflected in children's subjective maps. As in the study of HOERSCHELMANN and SCHAEFER (2005), drawings of children/young people from an advantaged area, in comparison to a disadvantaged one, are much more elaborated, represent a larger space, and show a dense network of after-class activities and places where the young people's friends and relatives live. According to HOERSCHELMANN and SCHAEFER, this may be because such young people actively develop their individual life projects and "openly embrace [the advance of globalisation] as a means of personal development and encounter it with curiosity" (2005, p.237). Although, following a by-now well-established tradition in childhood studies, I agree that young people are not passive objects of socialisation and are capable, to a certain degree, of choosing and making decisions over their own lives (see e.g. PROUT & JAMES, 1990; for an overview see also NIKITINA-DEN BESTEN, 2009), I would argue that this openness to opportunities and this ability to engage in self-developing educational projects is deeply rooted in family upbringing which is classed and gendered. Extracurricular education opportunities available to one family may not be available to another. As VINCENT and BALL write, "[w]hat is ... important ... is to recognize that there are particular "conditions of acquiring" involved here—the class, the teacher, the equipment—conditions that are only available to those who can afford them" (2007, p.1074). [29]

The necessity of extra-curricular activities for children/young people is debated in the literature. While SWANSON's study (2002) demonstrates that strategically engaging in activities may be a crucial factor enabling young people to realise their long-term life goals, VINCENT and BALL are more critical of "the phenomenon of enrichment activities" (2007, p.1062) especially in what concerns very young children. On the one hand, the findings of my study give an alternative perspective on childhood in disadvantaged areas, compared to the impression one would get from popular media. The drawings show, for example, that children in Kreuzberg, like in other places in our larger study of children in Paris and Berlin (see NIKITINA-DEN BESTEN, 2008; DEN BESTEN, forthcoming/2010a), enjoy playing sports (especially boys, who often picture a football field) and hanging out with their peers. But on the other hand, drawings of children/young people from the disadvantaged area in this study reveal much less engagement with specialised after-class activities, and this coincides with a much "poorer" spatial world. The space on these children's maps looks much less used and explored, than on the maps of children/young people from an advantaged area. I thus make the point that extra-curricular activities are also important for the development of children's social and spatial identities and that, in the absence of financial resources and cultural capital (BOURDIEU, 2004) in families in disadvantaged areas, it is public policies that need to address the problem of children's after-class activities more strategically and follow it more closely. [30]

This research was made possible by a scientific scholarship from the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD). I am particularly grateful to Prof. Hartmut HÄUSSERMANN in Berlin for inviting me to Humboldt University to carry out this study. I would also like to thank all the pupils, teachers and parents who took part in the research, and all the people who helped to gain access to the schools. Many thanks also go this issue's editors, Susan BALL and Chris GILLIGAN, and two anonymous referees for their helpful comments and suggestions.

1) Socially Integrative City programme: http://www.stadtentwicklung.berlin.de/soziale_stadt/index_en.shtml, http://www.quartiersmanagement-berlin.de/english/ and http://www.sozialestadt.de/en/programm/ [Accessed: October 20, 2009]. <back>

Anthias, Floya (2001) The concept of "social division" and theorising social stratification: Looking at ethnicity and class. Sociology, 35, 835-854.

Barker, John & Weller, Susie (2003). "Never work with children?": The geography of methodological issues in research with children. Qualitative Research, 3(2), 207-227.

Beckmann, Christa (2004). Hier sind wir Lehrer die einzigen Ausländer. Berliner Morgenpost, 10 June 2008, http://www.morgenpost.de/printarchiv/berlin/article383871/Hier_sind_wir_Lehrer_die_einzigen_Auslaender.html [Accessed: May 25, 2010].

Berliner Senatsverwaltung fuer Gesundheit, Soziales und Verbraucherschutz (2004). Sozialstrukturatlas Berlin 2004. Berlin: Berliner Senatsverwaltung fuer Gesundheit, Soziales und Verbraucherschutz, Pressestelle.

Bourdieu, Pierre (2004). Forms of capital. In Stephen J. Ball (Ed.), The RoutledgeFalmer reader in sociology of education (pp.15-29). London: RoutledgeFalmer.

Cahill, Cathleen (2000). Street literacy: Urban teenagers' strategies for negotiating their neighbourhood. Journal of Youth Studies, 3(3), 251-277.

Chisholm, Lin; Buechner, Peter; Krueger, Heinz-Hermann & Brown, Philip (Eds.) (1990). Childhood, youth and social change: A comparative perspective. London: Falmer Press.

den Besten, Olga (forthcoming/2010a). Local belonging and "geographies of emotions": Immigrant children's experiences of their neighbourhoods in Paris and Berlin. Childhood.

den Besten, Olga (forthcoming/2010b). Negotiating children's outdoor spatial freedom: Portraits of three Parisian families. In Louise Holt (Ed.), Geographies of children, youth and families: An international perspective. London: Routledge.

du Bois-Raymond, Manuela; Sunker, Heinz & Krueger, Heinz-Hermann (Eds.) (2001). Childhood in Europe: Approaches—trends—findings. New York: Peter Lang.

Economist (2008). Two unamalgamated worlds: Germany's Turkish minority. The Economist, 3(April), 31.

Elsley, Susan (2004). Children's experience of public space, Children and Society, 18(2), 155-164.

Forsberg, Hannele & Strandell, Harriet (2007). After-school hours and the meanings of home: Re-defining Finnish childhood space. Children's Geographies, 5(4), 393-408.

Gorard, Stephen & Taylor, Chris (2002). What is segregation? A comparison of measures in terms of "strong" and "weak" compositional invariance. Sociology, 36(4), 875-895.

Häussermann, Hartmut & Kapphan, Andreas (2000/2002). Berlin: von der geteilten zur gespaltenen Stadt? Sozialräumlicher Wandel seit 1990. Berlin: Opladen.

Häussermann, Hartmut & Kapphan, Andreas (2005). Berlin: From divided to fragmented city. In F.E. Ian Hamilton, Kaliopa Dimitrovska Andrews & Nataša Pichler-Milanović (Eds.), Transformation of cities in Central and Eastern Europe: Towards globalization (pp.189-222). Tokyo: United Nations University.

Halseth, Greg & Doddridge, Joanne (2000). Children's cognitive mapping: A potential tool for neighbourhood planning. Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design, 27(4), 565-582.

Hancock, Roger & Gillen, Julia (2007). Safe places in domestic spaces: Two-year-olds at play in their homes. Children's Geographies, 5(4), 337-352.

Hoerschelmann, Kathrin & Schaefer, Nadine (2005). Performing the global through the local-globalisation and individualisation in the spatial practices of young East Germans. Children's Geographies, 3(2), 219-242.

James, David R. & Tauber, Karl E. (1985). Measures of segregation. In Nancy Tuma (Ed.), Sociological methodology (pp.1-32). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Katz, Cindi (2004). Growing up global: Economic restructuring and children's everyday lives. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Kopietz, Andreas (2006). Einzelfälle oder Trend? Berliner Zeitung, 17 November, p.18.

Kuhn, Peter (2003). Thematic drawing and focused, episodic interview upon the drawing—A method in order to approach the children's point of view on movement, play and sports at school. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 4(1), Art. 8, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs030187 [Accessed: April 20, 2010].

Lareau, Annette (2002). Invisible inequality: Social class and childrearing in black and white families. American Sociological Review, 67, 747-776.

Leontiev, Alexei (1975). Deyatelnost', soznanie, lichnost' [Activity, consciousness, personality]. Moscow: Progress.

Leontiev, Alexei (1979). The problem of activity in psychology. In James V. Wertsch (Ed.), The concept of activity in Soviet psychology (pp.37-133). Armonk, NY: M. E. Sharpe.

Massey, Douglas S.; White, Michael J. & Phua, Voon-Chin (1996). The dimensions of segregation revisited. Sociological Methods Research, 25(2), 172-206.

Matthews, Hugh (1992). Making sense of place: Children's understanding of large-scale environments. Hemel Hempstead: Harvester Wheatsheaf.

Ní Laoire, Caitríona; Carpena-Méndez, Fina; Bushin, Naomi & White, Alex (2010/forthcoming). Childhood and migration: Mobilities, homes and belongings. Childhood.

Nikitina-den Besten, Olga (2008). Cars, dogs and mean people: Environmental fears and dislikes of children in Berlin and Paris. In Katja Adelhof, Birgit Glock, Julia Lossau & Marlies Schultz (Eds.), Urban trends in Berlin and Amsterdam (pp.116-125). Berlin: Humboldt Universität.

Nikitina-den Besten, Olga (2009). What's new in the "new social studies of childhood"? The changing meaning of "childhood" in social sciences. INTER: Interaction, Interview, Interpretation, 5, 25-39.

Olwig, Karen Fog & Gulløv, Eva (Eds.) (2003). Children's places: Cross cultural perspectives. London: Routledge.

Payne, Geoff (2007). Social divisions, social mobilities and social research: Methodological issues after 40 years. Sociology, 41, 901-915.

Pike, Jo (2008). Foucault, space and primary school dining rooms. Children's Geographies, 6(4), 413-422.

Plarre, Plutonia (2006). Polizei löst Krawall auf. Die Tageszeitung, 17 November, p.25.

Prout, Alan & James, Allison (Eds.) (1990). Constructing and reconstructing childhood: Contemporary issues in the sociological study of childhood. Basingstoke: Falmer Press.

Punch, Samantha (2002). Research with children: The same or different from research with adults? Childhood, 9(3), 321-341.

Ren, Julie Y. (2006). "Immigrant" teenagers in Berlin youth centers: Transformation of public spaces. Washington, DC: Fullbright Commission.

Ross, Nicola J. (2007). "My journey to school ...": Foregrounding the meaning of school journeys and children's engagements and interactions in their everyday localities. Children's Geographies, 5(4), 373-392.

Sleutjes, Bart (2008). Dealing with social segregation: The "Rotterdam approach" versus the "Berlin approach". In Katja Adelhof, Birgit Glock, Julia Lossau & Marlies Schultz (Eds.), Urban trends in Berlin and Amsterdam (pp.69-81). Berlin: Humboldt Universität.

Soboczynski, Adam (2006). Fremde Heimat Deutschland. Die Zeit, 12 October, p.17-21.

Swanson, Christopher (2002). Spending time or investing time? Involvement in high school curricular and extracurricular activities as strategic action. Rationality and Society, 14(4), 431-471.

Tsoukala, Kiryaki (2001). L'image de la ville chez l'enfant. Paris: Anthropos.

Tsoukala, Kiryaki (2007). Les territoires urbains de l'enfant. Paris: L'Harmattan.

Vincent, Carol & Ball, Stephen (2007). "Making up" the middle-class child: Families, activities and class dispositions. Sociology, 41(6), 1061-1077.

Vygotsky, Lev (1962). Thought and language. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Ward, Colin (1990/1978). The child in the city. London: Bedford Square.

Young, Lorraine & Barrett, Hazel (2001a). Adapting visual methods: Action research with Kampala street children. Area, 33(2), 141-152.

Young, Lorraine & Barrett, Hazel (2001b). Issues of access and identity: Adapting research methods with Kampala street children. Childhood, 8(3), 383-395.

Zeiher, Helga (2003). Shaping daily life in urban environments. In Pia Christensen & Margaret O'Brien (Eds.), Children in the city: Home, neighbourhood and community (pp.66-81). London: Routledge/Falmer.

Olga DEN BESTEN (NIKITINA) is an independent researcher in social sciences based in Paris. She was awarded her PhD in 2002 from Moscow State Pedagogical University and has worked on various research projects in Russia, France, Germany, and the UK. Since 2005, Olga has been working mainly in the field of childhood studies. This work has focused on the relationship of migrant children with their urban environment, as well as how children can contribute to changing their environment through participating in school-building projects. Her other research interests include gendered biographical patterns and strategies, wartime experiences and memories, career and entrepreneurship, and non-market economic activities. In her research, Olga DEN BESTEN uses qualitative methodology and is especially interested in visual and participatory research methods.

Contact:

Olga den Besten

Independent Researcher

Paris, France

E-mail: ol.nikitina@gmail.com

URL: http://ssrn.com/author=1060356 and http://www.linkedin.com/in/olgadenbesten

den Besten, Olga (2010). Visualising Social Divisions in Berlin: Children's After-School Activities in Two Contrasted City Neighbourhoods [30 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 11(2), Art. 35, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs1002353.