Volume 12, No. 3, Art. 16 – September 2011

The Dilemma of Closeness and Distance: A Discursive Analysis of Wall Posting in MySpace

Lewis Goodings

Abstract: MySpace is an online social network site (SNS) where users regularly communicate via a particular part of the profile page known as "the wall". This article uses a discursive approach to study the construction of identity in communication on the wall. The analysis shows that wall communication constitutes a set of relational positions that need to be discursively organised in order to manage the presence of a mediated community of other MySpace users. Drawing on the work of Celia LURY, the paper explores this issue in terms of a set of practices for managing the dilemma of closeness and distance that stems from the new forms of individualism that is inherent to a "prosthetic" culture. The article is concerned with the way MySpace users negotiate the issue of distance and closeness as part of the process of identity construction in MySpace. A broader discussion in terms of discourse, community and technology is included.

Key words: identity; social network sites; discourse analysis; distance and closeness; mediated community; individualism

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. Identity

2.1 Virtual community and identity

2.2 Identity in mediated communities

3. Method

3.1 Participants and design

3.3 Analytic procedure

3.3 Ethics

4. Results

4.1 Negotiating identity positions

4.2 Distance and closeness

4.3 The "experimental individual"

5. Discussion

MySpace.com is an online social network site (SNS) that allows a global network of members to share discussions, photos, videos and blogs1). Many online groups (forums, listservs etc.) are collected around a particular issue (e.g. a political opinion, an organisation or a collective passion). However, MySpace and other SNSs (Facebook, Bebo, LinkedIn etc.) are designed to predominantly facilitate social interaction. COMSCORE (2009) found that 29.4 million UK users visited one of the top SNSs in May 2009 (i.e. Facebook, MySpace or Bebo) demonstrating that a large number of people use SNSs. COMSCORE also found that 6.5 million of these users specifically visited MySpace. [1]

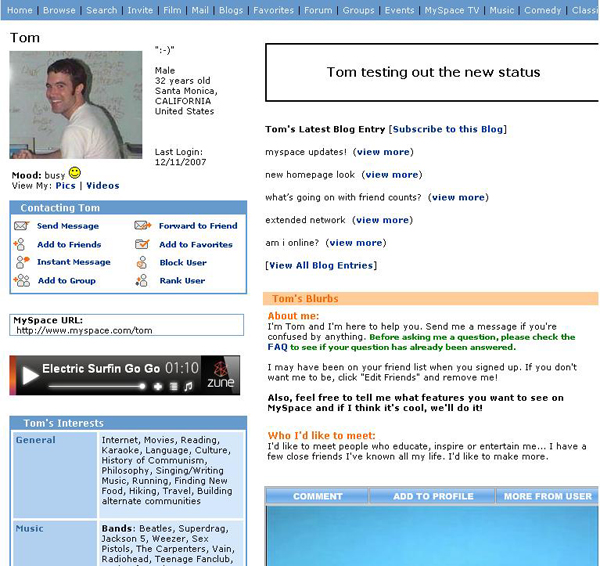

MySpace users log-on to a global network of online users using a self-styled personal profile that forms the gateway to communication with the other members. These profiles contain a variety of different features including: a photograph or image (typically of the profile owner), a list of personal information/interests, colourful graphics, other miscellaneous information, and a section of the page that is dedicated to short text messages known as "the wall" (for an example of a profile page see Figure 1). It is this final aspect of MySpace—"the wall"—that is of particular interest to this article2) (see Figure 2). MySpace users regularly visit their "friends' " profiles and leave messages3). This form of conversation is essentially "asynchronous" as there is no emphasis on the other members of the communication being present at the time of a wall post. This is instantly different to "synchronous" forms of communication where all members are present in the conversation.

Figure 1: Screenshot of Tom ANDERSON's profile page4) [2]

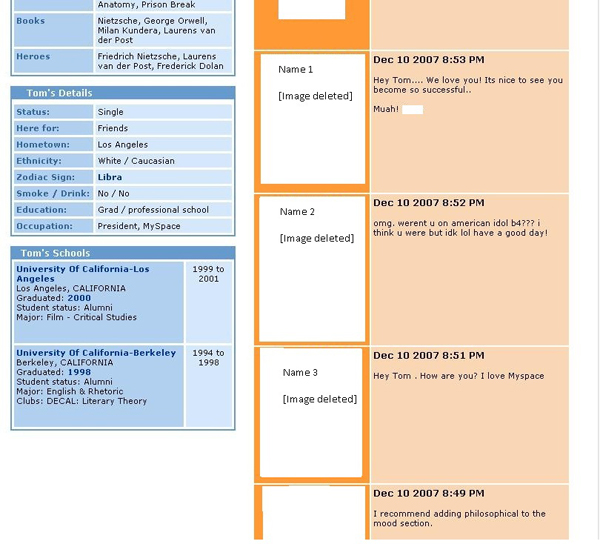

Wall posts appear on the profile in a pre-defined area of the screen and are publicly accessible to all MySpace users who list their profile as "public". MySpace users will regularly visit the profile pages of their online friends and leave a post on their wall. The conversation builds as the users switch back-and-forth across the profiles and leave messages. The wall is a popular way for people to communicate in MySpace and it is immediately visible to those people who share a network of friends. It is perhaps for this reason that MySpace and other SNSs have been labelled as a "public identity performance" (BOYD & HEER, 2006). The use of MySpace page is clearly a space for a number of new identity practices. The following section will give a brief review of some of the important points in the study of identity that will inform this investigation of MySpace.

Figure 2: Screenshot of the wall section of Tom's profile5) [3]

Identity has always been a pivotal area of discussion in the broader field of social psychology (HOGG & ABRAMS, 1988; TAJFEL, 1974). As a main proponent in social psychology, social identity theory (TAJFEL & TURNER, 1979) is based on a cognitive explanation of identity that involves identifying a division between our social and personal needs that relies on the ability to select the most advantageous position for self-conception. From this perspective, identity rests on a steady process of categorisation that allows for an explanation of recent actions in terms of a positive self-categorisation (HOGG, 2001). [4]

However, discursive psychology focuses on the way identity is socially produced, on-going, and managed at an everyday level (BILLIG, 1987; BENWELL & STOKOE, 2006; EDWARDS & POTTER, 1992; WIDDICOMBE & WOOFFITT, 1995). Within constructionist perspectives, identity is still recognised as the basic relationship one forms through the multiple relations of work colleagues, religious groups, neighbours, political groups and other relational connections, but what becomes of central importance is the way that all of these realities are created together and are constituted through their own practices of relating. Understanding identity in this way, relies on an acknowledgement that people construct "who they are" through the ability to collectively perform what it means to be a part of a particular group. The way people are able to promote a certain kind of identity category is known as "social positioning" (DAVIES & HARRÉ, 1990; HARRÉ & LANGENHOVE, 1999). The concept of positioning explains the way people are different from one identity category to the next (e.g. a school child may act very differently when in the presence of a teacher as opposed to his/her friends) and explicates the way that this action is managed in language and interaction (as opposed to being a cognitive function). [5]

Furthermore, from a constructionist position, identity is frequently understood as a form of self-identity as an attempt to incorporate an understanding of the self in everyday practices of identity construction (ABELL & STOKOE, 2001; GERGEN, 1994; WILKINSON, 2000). Following this tradition, BURR (1995) argues that we should think of the self and identity as inextricably linked and that we make sense of ourselves through the negotiation of different identity positions. This paper accepts the subtle intertwining of the two concepts and aims to develop an understanding of the duel process of self and identity in MySpace interaction. The question is then what to make of this form of identity theorising in term of MySpace? And in order to answer this question I must first address another conceptual point of reference that is at stake in this issue—community. [6]

2.1 Virtual community and identity

RHEINGOLD (1993) uses the term "virtual community" to define an online network of people who are associated with the positive feeling of being in a community and this definition intentionally avoids an attempt to define online communities in terms of their essential properties (e.g. size or shape). RHEINGOLD (1994, p.6) argues that the virtual community directly relates to the disappearance of "informal public spaces" and explains the Internet as an opportunity to disconnect from the dissatisfaction with everyday life and explore a positive, technically-driven form of community (see also DIBBELL, 1998). In terms of identity, RHEINGOLD (1994, p.147) argues that the freedom and choice that come with the virtual community "dissolves the boundaries of identity". From this perspective, the virtual community (which also has links to a history of "cyberspace") is explained as a space where the confines of our rigid identity are swapped for an imaginative realm of limitless identities and a space in which to embrace the possibilities of post-modernity (see also PLANT, 1993; LEARY, 1999). [7]

Sherry TURKLE (1995) famously wrote about how online communication offers the opportunity to "re-invent" oneself. TURKLE describes, from her own experience, how the computer becomes an opportunity to form a "second self" (see also STONE, 1995, 1996). Psychological studies typically embrace this theory as an intellectual point of departure and this work predominantly incorporates the literature on "presentation of self" (GOFFMAN, 1959). For example, this is shown in research that explores the distinction between an online self and a "true" self (BARGH, McKENNA & FITZSIMONS, 2002); how the self is presented in Internet home pages (WALKER, 2000); and most relevantly, how the use of GOFFMAN's work can be used to understand the actions in social network sites (KRAMER & WINTER, 2008; TUFEKCI, 2008; SIIBAK, 2010). Therefore, new technologies are providing another form of computer-mediated communication that can be adapted to a particularly sociological version of self and identity. [8]

However, the notion of the second self was formulated during the first generation of computer mediated communication and may warrant a revival in terms of the new technologies such as MySpace and Facebook. The difficulty with the decision to use this theory for new technologies is, as with the notion of virtual community, that there is a tendency to view the phenomena in terms of a "doubling of reality" (WITTEL, 2001, p.62). WITTEL argues that the focus should be on the "mediation" of everyday practices as opposed to treating the online community as somehow virtual or separate. Therefore, I aim to explore the notion of identity in MySpace by conceptualising MySpace as a mediated community. [9]

2.2 Identity in mediated communities

All communities are in some way mediated. SNSs represent a new way of connecting with a network of members as they provide an electronic community where there are a range of culturally/technically specific practices for mediating a shared experience. The term mediated community is chosen to define MySpace as opposed to that of virtual community or just online community—not because these definitions are not all applicable in their own right—but because the term mediated community accurately describes the specific practice of belonging to community in MySpace. Mediated community is a particularly useful terminology as it captures the way MySpace users are constituted form both online and offline friends. MySpace, as with many other SNSs, can be understood as a network of smaller communities where users a connected through a shared sense of community. Each of these members has a particular specific community that is mediated through MySpace and it is the relative degree of mediation that is of particular importance. Mediated community is then something which is felt or experienced through a shared sense of belonging. [10]

Mediated community defines a selection of people who are subject to a similar set of community practices (WENGER, 1998). This concept allows the possibility to incorporate Benedict ANDERSON's (1983) notion of "imagined community" to describe the sense of connection that members feel through a community membership where, even though many of the members may never have met or will ever meet, there is a perceived presence of other members. This notion of imagined community is not considered to be "in the minds" of the individuals but in the social practices of the community. [11]

However, this does not mean that the community has any control over the members or that the community exists beyond just being there. MySpace users have to act into the community in order to create meaning. In this sense, the community is just there because we can never know or interact with all of those with whom we share a community but we still structure each conversation to communicate with our imagined set of relations. We can then look at the way that this mediated community is created and performed through the discursive ability to constitute a shared sense of identity and community. [12]

This article is looking at how these issues of identity and community are present in a set of wall post conversations. In doing so this intends to contribute to the knowledge of MySpace practices through the study of actual interactions from the site. This will require the analysis of communication which is taken directly from MySpace and will explore the way that identity and community are deployed in different ways. This is focussed on the way that the text is able to "position" the author in a particular way. The main research question is then: How do people manage, organise and structure their identity through the interactions via the action of wall posting in MySpace? [13]

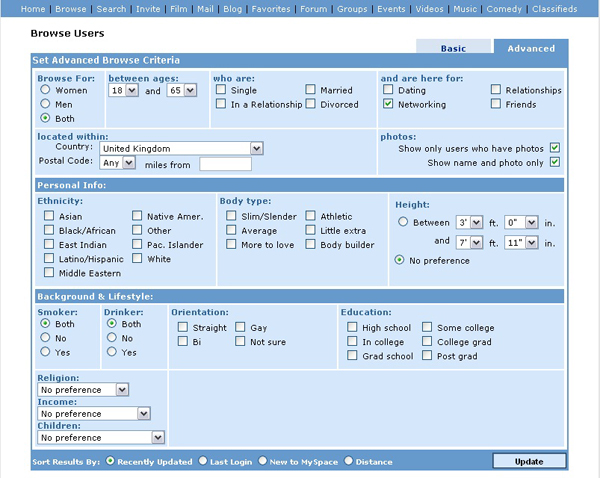

The data for this research was gathered from publicly accessible MySpace pages. A total of 100 MySpace profiles were observed for a period of one month. The 100 profiles were gathered from a search using the internal MySpace "browse" function, which initially returning over 3,000 hits. In this search all of the MySpace search criteria was aligned to the default settings except for "location" and "[what are you] here for" at which point the categories were appropriately set to "UK" and "networking" respectively (the search criteria is shown in Figure 3). The browse function uses a complex algorithm to align search criteria based on a unique MySpaceID (a number that is assigned to each profile). The study used the first 100 profiles returned in from a search as a way of selecting the participants semi-randomly.

Figure 3: Screenshot of the search criteria used to gather the profiles [14]

In aligning the search to those interested in "networking" the study was focussed on MySpace users who were "active" members in terms of use and who were likely to visit their profile regularly. Each of the 100 profiles was observed for one month and any changes to the profile page were documented with a screenshot of the page6). The period of one month was chosen in order to guarantee a sequence of communicative action and allow for a reasonable amount of conversation on the wall. If the data had been gathered over a longer period, for example one year, the conversation may have been difficult to follow due to the possibility that the link might "break" or become inactive. [15]

This data was able to answer the research question by giving actual examples of MySpace communication that could be analysed in terms of the discursive displays of identity and community. Each screenshot could be re-enacted at a later date in order to analyse the communication from wall-to-wall. This is due to the way that the conversation is technically divided into two sections, in which each profile only showing the posts from other users. The analysis required linking each of the posts together using the unique time signature that is assigned to each post. The act of using data directly from MySpace accesses a natural form of communication where each statement is not couched in the interview process or potential researcher bias (for discussion on the limitations of interviewing see POTTER & HEPBURN, 2005, 2007). These observations produced detailed accounts of MySpace conversations which could then be analysed for discursive processes, themes and meanings. [16]

The data was analysed using discourse analysis (DA). DA is a methodology for examining how people use language to "construct" specific versions of events (see EDWARDS & POTTER, 1992; EDWARDS, MIDDLETON & POTTER, 1992; WILLIG, 2001). DA focuses on the social functions that are achieved through the specific use of the talk, where it is pertinent to ask why the speaker has formulated in one way as opposed to another. There is also a tendency to explore the contradictions in talk; for example, where a person might describe themselves in seemingly contradictory ways in the same conversation. For example, POTTER and WETHERELL (1987) show the impact of the discursive power of switching between the use of the term "terrorist" or "freedom fighter" depending on the current shape of the conversation. In DA there is a focus on the resources that people use (descriptions, rhetorical resources etc.) and the way that these resources accomplish social actions in talk. DA concentrates on the power of "talk-in-interaction" (PSATHAS, 1996). Therefore, DA will provide a way of view how the MySpace users construct their identity in the wall post conversations. [17]

The analysis will also focus on the way that people begin and end their conversations in MySpace. This connects with the conversation analytic tradition (which is similar to DA) in terms of an interest in "openings" and "closings" (PATTERSON & POTTER, 2009; SACKS 1992; SCHEGLOFF, 1986, 1989; SCHEGLOFF & SACKS, 1973). In looking at the beginning and end of a conversation it is possible to see the way that people organise their relational connections through these pivotal aspects of the communication. This will further show the way that identity is conceptualised as a social process that becomes visible at the site of communication. [18]

The study was limited to users aged over eighteen and under sixty-five in order to maintain a high ethical standard. This was achieved by refining the search criteria to MySpace users who were between these age ranges. The safety of the MySpace users is paramount to this investigation and as a result all names have been concealed and protected from the analysis. Each of the MySpace users were also sent an e-mail to their MySpace account shortly after the research was completed which gave the participants the opportunity to withdraw from the study. None of the MySpace users asked for their information to be removed. Many studies of MySpace now use this non-invasive form of data collection to explore this new phenomenon (see also MORENO, PARKS & RICHARDSON, 2007; THELWALL, 2009). [19]

This paper will explore three separate examples taken from the data. These examples are representative of the sample as a whole and follow a set of social practices that were exhibited by a high proportion of the participants. The data will be presented in a conversational pattern (as opposed to the reverse-order in which it appears on the wall) in order to aid the analysis of the interaction in sequence. The results section will be organised into three themes: negotiating identity positions, distance and closeness, and the "experimental individual". [20]

4.1 Negotiating identity positions

Extract 1:

"Liam7): Hello Jane how's things? How's life in sunny old [Town A]?

Jane: heya not bad thanks, got a day off today but its not sunny :-( u back from [Country A] yet? X

Liam: Yeah im on leave for a month. I'm so bored! I'm thinking of coming down at some point. I'm fed up with this place it's doing my head in! aaahggghh!

Jane: where u 2? back up in [Town B] with your family? its not much better down here! Bet it was well hot out there by the time you had left!

Liam: Yeah just in little old [Town B]. I would rather be in [Town A] right now. Yeah, the temp was up to 57 I think when I left. It was really unbearable heat! And now im back in the freezing cold again woo hoo!

Jane: god thats so hot!! i went to [Country B] in may with a friend when ads was away an the hottest it got there was 37 an that was me sat by a pool an i found that too hot coudlnt imagine working in it!

Liam: nah it's not nice at all! I think the humidity was 90% as well which didnt help one little bit! Whats ad's up to today?

Jane: yeah i cant even begin to imagine what its like, i have no idea what hes doing.

Liam: Ok then, what are you upto on this fine day? Lol8)

Jane: Not very much, gona go shopping in a little while. Its my birthday next week so im trying to plan what to do for next weekend just having a bit of chill out day really, u up to anything exciting??

Liam: This is as exciting as my leave gets really. Apart from wasting my money on big pissups all the time. Ive got a night out on friday planned but thats about it. What date is your birthday?

Jane: haha oh dear! well its the 22nd august ive got the day off but ill probably save going out until the weekend i think. Was trying to plan a trip to [Town C] but it just became mission impossible too many different people that live in different places so thats out the window ill probably just end up in [Town D] or [Town E] as per usual!!

Liam: Fair enough but just remember it's your birthday noone elses. You enjoy yourself no matter where you end up going!

Jane: Cheers hun, hope you have a good day x." [21]

Extract 1 shows a passage of communication that begins with a reference to "sunny old [Town A]" and performs a shared knowledge of this place as a way of invoking an interactional relevance for both parties. The use of this reference is able to geographically locate the position of one another in a known relationship to place which works to discursively locate the conversation in a set of known identity relations (for further discussion on the importance of place see GOODINGS, LOCKE & BROWN, 2007). The first reply from Jane echoes this function and the return post is orientated to Liam's reference to the weather ("heya not bad thanks, got a day off today but its not sunny :-( u back from [Country A] yet?"). The use of paralanguage (":-(" = depicting a sad face) constructs a connection that defends against any possibility over-investment in the conversation. This shows the ability to perform an identity positioning based on a known set of offline/existing relations where there is the ability to protect against any over-investment in the conversation. [22]

Liam continues that he is on "leave for a month" and here we begin to see the overall shape of the communication, which is predominantly in terms of the joint discussion around meeting up face-to-face ("I'm thinking of coming down at some point"). This is embedded within the discussion of the weather and would typically be seen as a "nested question" (SCHEGLOFF & SACKS, 1973). In this example, the conversation is premised with the distinct problematic (being "bored") that simultaneously raises the possibility of the trip as a way-out of such boredom. However, Jane's reaction is not one that supports this narrative as she writes "where u2? back up in [Town B] with your family" and this shows a resistance to the construction of boredom in which she also performs an equally powerful narrative of the limited amount of time Liam has with his family. Jane reinforces this narrative by adding that "its not much better down here" that acts to bolster the claim that a trip would not resolve his problem of boredom. In talking about the weather, Jane performs a continuing interest in Liam's recent activities while also protecting from any negative reactions to not accepting the reasons for the trip (i.e. that they are not friends). [23]

Liam continues to accept the topic of weather but widens the decision to visit Jane to include the benefits of visiting her location ("Yeah just in little old [Town B]. I would rather be in [Town A] right now"). This performs a different set of identity relations in which there is a focus on [Town A] as the purpose for the visit as opposed to being entirely concerned with visiting Jane. This also includes a reference to the safety topic of the weather ("was up to 57 I think when I left") and keeps the conversation open whilst still trying to stress the significance of the visit. In these posts social accomplishments have been set against the innocuous conversational backdrop of the weather and shows that the construction of identity using the wall is a delicate practice that requires a negotiation of identity positions due to the felt presence of a mediated community (i.e. the other MySpace members). [24]

Jane gives a short narrative about a trip to [Country B] that also manages to normalise the category of [Town A] (and hence Jane) as being "not exciting" and subsequently providing no reason to take a trip to [Town A]. This post also shows the introduction of a new character in the shape of "ads", which prompts the question "Whats ad's up to today?" Jane's reply appears to clarify her relationship with ads as in a previous post Jane states that she went to [Country B] "while ads was away", which seems imply a close proximal relationship (i.e. Jane was able to go away because ad's was away). However, in this post it appears that Jane is keen to construct her position as one that is not dependent on his location and as an amplification of this position, this post contains no self-protecting weather discourse and communicates a powerful message to Liam and the rest of her mediated community. [25]

In response, Liam appears to be more light-hearted with his next post and returns the focus back to Jane's activities by stating "what are you upto on this fine day? Lol". This appears to recognise the boldness of Jane's previous statement (in relation to ads) and once more the weather forms an ordinary topic for communication. Jane's reply to this question is orientated towards keeping the discourse at a more generic level and includes the discussion of a shopping trip and her upcoming birthday arrangements. What is interesting is that neither of these activities seems to be communicated in a way that would signal involvement from Liam. [26]

In the later stages of the communication, Liam again displays his dissatisfaction with his current position ("This is as exciting as my leave gets really") as even the prospect of "big pissups" seem to be thwarted by the way that it wastes his money. This can then be linked with the way he finishes the message—"what day is your birthday?" In the reply to Liam's question, Jane provides a rationale for why Liam would not want to go to Jane's party and constructs the reasons for avoiding a trip ("too many people that live in different places"). It presents a situation where the only reason why he should make such a long trip would be if it was a special occasion—and this is definitely not such an occasion ("ill probably just end up in [Town D] or [Town E] as usual"). [27]

The conversation appears to be drawing to a close as the continuation of the narrative has exhausted the content of both strands of the communication (the weather and the possibility of a trip). Each narrative has been subtly moved into a position where the end of the conversation is immanent. Liam performs the end of the conversation with a statement that shapes the public appearance of the conversation ("fair enough but just remember it's your birthday noone elses"). This post constructs a position that avoids any negative accountability of his attempts to plan a trip to [Town A] and shows a ramped-up attempt to connect with the mediated community in the final stages of the wall conversation. [28]

Example 1 shows the way that Liam and Jane are in the process of negotiating their identity in MySpace. This subtle identity positioning is managed by different language practices that are marked by a dilemma of closeness and distance, where different potential actions (e.g. the trip) have to be managed against the intention to maintain the friendship. The imagined aspect of community also leads to range of interactional complexities (e.g. take the reference to "ads" in the conversation) that are continually being negotiated and re-negotiated in light of the current context. Therefore, this distance and closeness is perpetuated by the potential experience of the other community members. In the following extract the analysis continues to explore this issue of distance and closeness. [29]

Extract 2 follows the interaction between Sally and Dave. In the first stages of this extract it is clear that Dave has posted on Sally's wall four times before he receives a response:

Extract 2:

"Dave: Hello, hows it going how was your weekend hope it was good hope your doing ok

Dave: lol just realised something else you will know my little brother as well he was in your year as well then ha ha

Dave: cant believe you was in his year at school he comes out with us on a sunday rofl9)

Dave: how we doin you have been quiet for a few days what you been upto

Sally: am not bad ta10). you? whos your bro11) then?

Dave: im fine ta my brother is Alan said he knows you apparently when we have been out he said hello to you and i was with him but dont remember

Sally: no way!!! lol. i dont remember seein him since school, my memory aint that good atm12) though. hows he doin? your kids are so cute btw13)

Dave: he is doing good full of muscles now i took him the gym when he was 17 and now he practically lives there the oh btw the kids get there cuteness from me lol

Sally: which gym14)? i know a few ppl15) that use [name of gymnasium]" [30]

In the first of the four posts Dave uses a fairly generic tone when he states "how was your weekend?" A post of this kind could easily be overlooked by a casual observer and, perhaps as a result, in the second post Dave uses a more direct approach to initiating communication ("lol just realised something else you will know my little brother as well he was in your year as well then"). The third post in the first sequence continues the sentiment and further develops the connection to his brother ("he comes out with us on a sunday rofl") and this performance is bolstered by the post containing a compliment to Sally's age ("cant believe he was in your year at school") where there is the discursive creation of two categories of "young" and "old" to which Dave is therefore complimenting Sally by orientating her to the younger group. The fourth post makes relevance to the fact that Dave has yet to receive a reply to any of his posts as he states "how we doing?" The use of the term "we doing" as opposed to the typical question "how are you doing" shows a need to clarify the connection between the two people. Put more simply, the last post literally asks "how are we doing" or "are we still friends?" The impact of these posts could be compared to the discursive principle of "try marking" (SACKS & SCHEGLOFF, 1979; SCHEGLOFF, 1996) where speakers typically offer a number of potential strands of communication in order to develop a conversation. The use of the consecutive posts could be seen as an electronically mediated form of try marking. This shows that conversations do not always occur as simply as the data in Extract 1 would suggest. [31]

In "Prosthetic Culture", Celia LURY (1997) explains how identity (or self-identity) is based on a "potential" form of experience that is made possible by new prosthetic technologies. LURY focuses on the issue of photography and shows how different forms of self-identity are made possible through a changing relationship with our notions of individualism. LURY describes how the prosthetic culture allows for a form of individualism that is characterised with a process of "experimentation". Here, "aspects that previously seemed fixed, immutable or beyond will or self-control are increasingly made sites of strategic decision-making, matters of technique or experimentation" (p.1). Therefore, self-identity is not shaped by working on a set on internal dispositions but through the modification of the self-image. It is looking through the use of a prosthetic culture (MySpace etc.) the people are able to experiment with who they can be through the modification of the image of the self-identity. [32]

This process of experimentation is characterised by a blurring of the public and the private. For LURY, following BARTHES (1981), the changes to individualism leads to a high amount of "interiority without intimacy". Here, individualism includes the commodification of private characteristics at a public level that results in an "interiority" of the individual. The individual is interiorised and made available through the prosthetic culture, whereby self-identity can be continually negotiated and re-negotiated through the mobilisation of the interior in different ways. This public display of interiority also obscures the relationship between the two and fuels the continual need for the negotiation between the interior and exterior. Put more simply, in trying to understand ourselves through technology there is the need to constantly readdress who we are. [33]

Extract 2 presents an opportunity to explore this issue of interior and exterior, distance and closeness. The first reply from Sally shows very little content compared to the four posts Dave produced earlier in the stages of conversation ("am not bad ta. you? whos your bro then?") The post constructs a somewhat rushed image where little care has been taken for grammar and term of address, giving the impression of a chaotic lifestyle that accounts for the earlier distance in the four missed posts. Only when Dave further clarifies information about his brother ("said he knows you apparently") is there a marked difference in Sally's involvement in the conversation—"no way!!! lol. i dont remember seein him since school, my memory aint that good atm though. hows he doin? your kids are so cute btw". Sally confesses to not remembering seeing Dave's brother since school in the use of the phrase "my memory aint that good atm" which could be seen as a further performance of her earlier distance. The end of the post keeps the conversation open through asking the question "hows he doing?" and the formation of the compliment "your kids are so cute btw"16). This repays the earlier compliment and performs a sense of closeness. [34]

Dave uses the narrative of his brother going to the gym to show something about his own interests and abilities (e.g. the use of "I" in the first line: "I took him to the gym"). The pronoun use positions Dave as accountable for his brother's fitness and constructs accountability for his kids "cuteness" ("the kids get their cuteness' from me lol"). Each of these discursive moves is an opportunity for Dave to position his identity in his communication with Sally. However, the final post shows that most of this work on cuteness goes unnoticed as Sally focuses on the importance of the gym itself ("which gym? i know a few ppl that use [name of gymnasium]"). In the final post, Sally has reverted back to a relation connection with Dave that is personified by distance and separation and where Dave's attempt to invoke a conversation that incorporates personal facts is greeted with a neutral response ("the gym"). The huge potential of MySpace interaction immediately poses a problem for those who have lots of friends in how they manage the everyday connection with other users. In this example Sally seems to control her relations by keeping many interactions at a periphery. It is clear that as the conversation pulls more of the private into the public that there is a high amount of "intimacy without interiority". Whereby, in making a number of new identities possible (through the relations with other users), there is an instantaneous production of distance. [35]

4.3 The "experimental individual"

The following extract will explore the notion of closeness and distance in terms of identity in MySpace. This dilemma is shown in the interaction between Ki and Ani-24:

Extract 3:

"Ani-24: Kiiiii!! heya! what's up? it's been too long you know, way too long! Hope everything is good ... i'm back in [Country C] for a few days and then i'm coming to [Country D]! i'm excited!! anyways i'll be back later to terrorize you ... take care!

Ani-24: oh by the way ... i like the song you got on ur page ... =)

Ki: i heard u are coming to visit soon, thats really nice, i am going to be 21 so we can go out together hahalol i cannt wait to see you!!!

Ki: where are u? now

Ani-24: still home in [Country C] ... well until tomorrow morning and then i'm off to the [Country D] ... staying with erin for the weekend and then it's [Name of College] time ... woohoo!

Ani-24: so back in [Country C] ... sorry i didn't say bye but i left kind of in a hurry due to the storm coming in! but i had a really good time and it was soooooo nice to see you again! stay in touch love! talk to you later. *hugs*

Ki: its alright i am sorry i was kinda so out of it anyways, how;s ur trip back home. I wish I can visit you but i am poor hahalol as u know. keep in touch alright miss u and love you

Ani-24: the trip home wasn't too bad at all actually...didn't sleep at all but that's okay! haven't done much while i've been home, should work on an assignment but can't really get myself to do it you know ... anyways love you and miss you too! Ttyl17)" [36]

The first post in Extract 3 shows Ani-24 performing a high expectation of an upcoming trip to see Ki ("Kiiiii!! heya! what's up? it's been too long you know, way too long"). This can be seen in the exhaustive use of exclamation marks and the extension of Ki's name (which is typically read as if it is being shouted in netspeak terms). In an initial attempt to recognise the relationship between Ani-24 and Ki, the use of the term "terrorize" seems to perform their relationship in a way that invokes a positive shared history. Ki's response acknowledges the trip and reifies the optimistic performance of their relationship: "I am going to be 21 so we can go out together hahalol". This discursive strategy is staking a claim on closeness—"we can go out together" where the discussion of the trip also acts as a way of bolstering their levels of intimacy ("I cannt wait to see you!!!"). Each of these practices acts to perform a sense of closeness between the two people. [37]

The next turn in the conversation is from Ki and directly orientates to Ani-24's location ("where u?now"). This post is lexically different to "where are you now?" (which could be interpreted as a call to account in a fairly generic way) and the "u?now" performs a construction that is almost overly keen to learn Ani-24's whereabouts. And, almost immediately, Ki is provided with a response in which Ani-24 is specific about her location as she writes "still home in [Country C] ... well until tomorrow morning and then i'm off to the [Country D] ... staying with erin for the weekend and then it's [Name of College] time ... woohoo!" The reference of Ani-24's friend "erin" marks a known acquaintance that performs a shared relation whereby the use of this shared relation strengthens their friendship. The friendship is performed in a positive fashion and there seems to be a number intersecting modes of experience (e.g. online and offline). [38]

However, there is then an extended gap in the communication (potentially the trip itself) and the conversation is resumed several weeks later. In this later turn, Ani-24 orientates towards her potential accountability of not having done the actual partying well. This relates to the prior constitution of their relation in MySpace as being entirely positive and the post appears to fix-up a sense of distance that is left over from the trip. It is clear that this is not an entirely easy process as the experience of time passing also provides another layer of complexity in terms of the ability to begin the post ("so back in [Country C]"). This is also shown in the performance of the reason for leaving as outside of her control; "sorry i didn't say bye but i left kind of in a hurry due to the storm coming in!" Their connection is then reconstructed through MySpace as Ani-24 writes "[it was] sooooooo nice to see you" and the post is also finished with an affectionate form of closing through the use of the affectionate closing—"*hugs*". [39]

From Ki's reply we learn that the trip was not a complete success from his perspective either—"sorry i was kinda so out of it anyways". This shows that they both use the wall as a space to reconstruct their actions during the trip and the message ends with a performance of sincerity in the form of "keep in touch alright miss u and love you". This sentiment is unlike that which we have seen in the two previous examples and performs a process re-establishing the connection between the two people. In the final post of the extract, Ani-24 mimics Ki's construction of sincerity in the use of the line "love you and miss you too!" [40]

Extract 3 shows how distance and closeness are part of the identity process in MySpace. Identity is then rooted in the way users continuously connect and re-connect with other users as a way of making sense of who they are (and who they can be) through the technology. In technologising and interiorising the gaze, there is an automatic distrust for the presentation of the individual that results in the need to continually renegotiate self-identity. This is a reaction to the fluid nature of the prosthetic culture. Subsequently, identity formation in MySpace includes a sense of closeness through the need to publicise the personal, which is coupled with an equal amount of distance and detachment. [41]

Extract 3 shows that an individual cannot simply upload certain characteristics to their profile in order to state who they are in MySpace. Instead, the users are able to see who they can be through the experimentation with different identity positions. The data shows how the MySpace have to act into the mediated community in order to create meaning through the production of the external interior, the private made public. These different subject positions carry the potential for new identities to be developed in the conversations on the wall (and other parts of the page) where the blurring of the public and private imbues the "experimental individual" with a juxtaposition of closeness and distance, of interiority without intimacy. [42]

This article furthers the discussion of identity in online spaces by adopting a discursive approach to studying conversations via the wall. In so doing, the analysis has revealed the dilemma of closeness and distance. This dilemma can be understood as the reaction a prosthetic culture where the blurring of the public and the private has instilled a problematic of "interiority without intimacy". This function is part of the process of identity construction in MySpace and shows the way that new technological capabilities expand the way our seeing ourselves through new practices of the self. [43]

Identity in MySpace is highly dependent on the mediated aspects of the community. The analysis shows that the communication is shaped by the perceived level of community and connection with the group. In each of the extracts, the mediated community appears as a symbolic resource in the management of the problems associated with closeness and distance. Identity also includes a number of modes of experience (e.g. online and offline) that intersect at the point of communication. Therefore, the use of MySpace (and other SNSs) can lead to a new set of interactional complexities that should not be treated as a virtual or separate set of concerns from those that people encounter in other forms of experience. It is the subtle practices that develop to manage these complexities that should be of particular interest in the future. [44]

The main limitation to this research is the "natural" status of the data. Even though there is a natural sense to the way that this data is gathered, there is also something artificial in the way that the data is organised and analysed. For example, the data goes through a number of changes between the actual site of the communication and the reporting of the findings (i.e. taking a screenshot of the data, moving to a file on a computer, putting the data into sequence). Each of these transitions has the potential to impact on the interpretation of the data. Therefore, future research should focus on exploring the data in action, possibly with the use of ethnographic methods. [45]

Furthermore, in looking at any profile on a social network site it is clear that the textual forms of communication are only one aspect of the communication that is taking place in MySpace. It is also necessary to look at the visual forms of communication are part of the ever-changing social landscape in SNSs. This could further explore how the visual aspects of this profile are involved in the process of individualism, interiority and identity. [46]

I would like to thank Professor Steven D. BROWN and Dr. Abigail LOCKE for their comments on the analytic direction of this article. I would also like to thank the editors and reviewers at FQS for their insightful commentary on an earlier version of this article.

1) Weblogs or just "blogs" are a diary-style form of writing where people write blogs about seeing a recent event, their views on a particular subject, or more typically, they are just "about me". <back>

2) Even though MySpace terms this function "friends comments" it is known to the users as "the wall" due to the same feature being called the wall in a different SNS. <back>

3) The term "friend" describes the link between two profiles were both members have accepted the friendship. This process links the two profiles together and allows parts of the profile page to become visible. It is through the act of friending that the MySpace network grows. <back>

4) Tom ANDERSON is one of the co-founders of MySpace and his site is public access. It is now used as a form of help portal for people to discuss their problems with using MySpace. This screenshot was captured late 2007 and shows the general layout of the profile where it is noticeable that there is a profile photograph in a top left-hand corner and a number of other boxes that contain different activities (e.g. blogging, personal information, likes and dislikes etc.). <back>

5) The screenshot shows the wall section of the profile on the right-hand side of the screen. The names of the people who have written on the wall (plus their photographs) have been deleted in order to protect their identity. Each of the orange boxes represents a wall post made by another MySpace user. The wall posts would appear on this section of the page in reverse chronological order. This screenshot was captured alongside the data in 2007. <back>

6) A screenshot is a basic computer function that records everything on the screen in a picture file. The collection of screenshots captured in this study could be analysed by looking at the series of screenshots over time and noticing the changes. The word posts were also saved to a word file to aid the analysis. <back>

7) All names have been anonymised. <back>

8) "Lol! is generally accepted to mean "laugh out loud". <back>

9) "Rofl" is generally accepted to mean "Roll on the floor laughing". <back>

10) "ta" means "thank you". <back>

11) "bro" is short for "brother" in this example. <back>

12) "atm" stands for "at the moment". <back>

13) "btw" stands for "by the way". <back>

14) "gym" is short for "gymnasium". <back>

15) "ppl" is short for "people". <back>

16) This reference could be based on the visual aspects of the communication where Dave is pictured with a child in his profile photograph. <back>

17) "Ttyl" stands for "Talk to you later". <back>

Abell, Jackie & Stokoe, Elizabeth (2001). Broadcasting the royal role: Constructing culturally situated identities in the Princess Diana Panorama interview. British Journal of Social Psychology, 40, 417-435.

Anderson, Benedict (1983). Imagined communities: Reflections on the origin and spread of nationalism. London: Verso.

Bargh, John A.; McKenna, Katelyn Y.A. & Fitzsimons, Grainne M. (2002) Can you see the real me? Activation and expression of the "true self" on the internet. Journal of Social Issues, 58, 33-48.

Barthes, Roland (1981). Camera lucida: Reflections on photography (trans. R. Howard). New York: Hill and Wang.

Benwell, Bethan & Stokoe, Elizabeth (2006). Discourse and identity. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Billig, Michael (1987). Arguing and thinking: A rhetorical approach to social psychology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Boyd, Danah & Heer, Jeffrey (2006). Profiles as conversation: Networked identity performance on Friendster. Paper presented at the proceedings of the Hawai'i International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS-39), Persistent conversation track. Kauhi, HI:IEEE computer society, January 4-7, 2006, http://www.danah.org/papers/HICSS2006.pdf [Date of Access: August 15th, 2010].

Burr, Vivienne (1995). An introduction to social constructionism. London: Routledge.

ComScore (2009). Nine out of ten 25-34 year old U.K. Internet users visited a social networking site in May 2009, http://www.comscore.com/Press_Events/Press_Releases/2009/7/Nine_Out_of_Ten_25-34_Year_Old_U.K._Internet_Users_Visited_a_Social_Networking_Site_in_May_2009 [Date of Access: October 27th, 2010].

Davies, Bronwyn & Harré, Rom (1990). Positioning: The discursive production of selves. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 20(1), 44-63.

Dibbell, Julian (1998). My tiny life: Crime and passion in a virtual world. New York: Henry Holt and Company.

Edwards, Derek & Potter, Jonathan (1992). Discursive psychology. London: Sage.

Edwards, Derek; Middleton, David & Potter, Jonathan (1992). Toward a discursive psychology of remembering. The Psychologist, 5, 56-60

Gergen, Kenneth J. (1994). Realities and relationships: Soundings in social construction. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Goffman, Erving (1959). The presentation of self in everyday life. New York: Penguin Books.

Goodings, Lewis; Locke, Abigail & Brown, Steven D. (2007). Social networking technology: Place and identity in mediated communities. Journal of Community and Applied Social Psychology, 17, 463-467.

Harré, Rom & Langenhove, Luk van (Eds.) (1999). Positioning theory. Oxford: Blackwell.

Hogg, Michael A. (2001) Social categorization, depersonalization, and group behaviour. In Michael A. Hogg & Scott R. Tindale (Eds.), Blackwell handbook of social psychology (pp.56-85). Oxford, UK: Blackwell.

Hogg, Michael A. & Abrams, Dominic (1988). Social identifications: A social psychology of intergroup relations and group processes. London: Routledge.

Kramer, Nicole C. & Winter, Stephan (2008). Impression management 2.0: The relationship of self-esteem, extraversion, self-efficacy and self-presentation within social network sites. Journal of Media Psychology: Theories Methods and Applications, 20(3), 106-116.

Leary, Timothy (1999). Turn on, tune in, drop out (6th ed.). Berkley: Ronin Publishing.

Lury, Celia (1997). Prosthetic culture: Photography, memory and identity. New York: Routledge.

Moreno, Megan A.; Parks, Malcolm & Richardson, Laura P. (2007). Why are adolescents showing the world about their health risk behaviours on MySpace? MedGenMed, 9(4), 9, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2234280/ [Date of Access: July 13th, 2008].

Patterson, Anne & Potter, Jonathan (2009). Caring: Building a "psychological disposition" in pre-closing sequences in phone calls with a young adult with a learning disability. British Journal of Social Psychology, 48, 447-465.

Plant, Sadie (1993). Beyond the screens: Film, cyberpunk, and cyberfeminism. Variant, 14, 12-17.

Potter, Jonathan & Hepburn, Alexa (2005). Qualitative interviews in psychology: Problems and possibilities. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 2(4), 281-307.

Potter, Jonathan & Hepburn, Alexa (2007). Life is out there: A comment on Griffin. Discourse Studies, 9(2), 276-282.

Potter, Jonathan & Wetherell, Margaret (1987). Discourse and social psychology: Beyond attitudes and behaviour. London: Sage.

Psathas, George (1996). Conversation analysis: The study of talk-in-interaction. London: Sage.

Rheingold, Howard (1993). The virtual community: Homesteading on the electrical frontier. Reading: Addison Wesley.

Rheingold, Howard (1994). The virtual community: Finding connection in a computerised world. London: Secker and Warburg.

Sacks, Harvey (1992). Lectures on conversation, Vol. 1 and 2 (ed. by G. Jefferson). Oxford: Blackwell.

Sacks, Harvey & Schegloff, Emanuel A. (1979). Two preferences in the organisation of reference to persons in conversation and their interaction. In George Psathas (Ed.), Everyday language: Studies in ethnomethodology (pp.15-21). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Schegloff, Emanuel A. (1986). The routine as achievement. Human Studies, 9, 111-152.

Schegloff, Emanuel A. (1989). Reflections on language, development and the interactional character of talk-in-interaction. In Marc Bornstein & Jerome S. Bruner (Eds.), Interaction in human development (pp.139-312). Hillside, NJ: Erlbaum.

Schegloff, Emanuel A. (1996). Turn organisation: One intersection of grammar and interaction. In Elinor Ochs, Sandra Thompson & Emanuel A. Schegloff (Eds.), Interaction and grammar (pp.52-134). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Schegloff, Emanuel A. & Sacks, Harvey (1973). Openings and closings. Semiotica, 7, 289-327.

Siibak, Andra (2010). Constructing masculinity on a social networking site: The case study of visual self-presentations of young men of the profile images of SNS Rate. Young, 18(4), 403-425.

Stone, Allucquere R. (1995). Sex and death among the disembodied: VR, cyberspace, and the nature of academic discourse. Sociological Review Monograph, 42, 243-255.

Stone, Allucquere R. (1996). The war of desire and technology at the close of the mechanical age. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Tajfel, Henri (1974). Social identity and intergroup behaviour. Social Science Information, 13, 65-93.

Tajfel, Henri & Turner, John C. (1979). An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In William G. Austin & Stephen Worchek (Eds.), The social psychology of intergroup relations (pp.33-47). Monterey, CA: Brooks/Cole.

Thelwall, Mike (2009). MySpace comments. Online Information Review, 33(1), 58-76.

Tufekci, Zaynep (2008). Can you see me now? Audience and disclosure regulation in online social network sites. Bulletin of Science Technology and Society, 28(1), 20-36.

Turkle, Sherry (1995). Life on the screen: Identity in the Age of the Internet. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Walker, Katherine (2000). "It's difficult to hide it": The presentation of self on internet home pages. Qualitative Sociology, 23(1), 99-120.

Wenger, Etienne (1998). Communities of practice: Learning, meaning, and identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Widdicombe, Sue & Wooffitt, Robin (1995). The language of youth subcultures. Prentice Hall.

Wilkinson, Sue (2000). Women with breast cancer talking causes: Comparing content, biographical and discursive analyses. Feminism and Psychology, 10(4), 431-460.

Willig, Carla (2001). Qualitative research in psychology: A practical guide to theory and method. Buckingham: Open University Press.

Wittel, Andreas (2001). Toward a network sociality. Theory, Culture and Society, 18(6), 51-76.

Dr. Lewis GOODINGS is a lecturer in social psychology at Roehampton University. His research is dedicated to the area of computer-mediated communication from a qualitative perspective. Dr. GOODINGS uses a constructionist approach to new forms of online communication and is interested in classic notions of identity, community and the self. He is currently working on developing an approach to new forms of social media, including social network sites and other new forms of communication mediums. He is also interested in the broader social dynamics of technology, discourse and organisation from a social psychological viewpoint.

Contact:

Dr. Lewis Goodings

Department of Psychology

Roehampton University

Whitelands College

Holybourne Avenue

London, SW15 4JD

UK

Tel.: + 44 (0)208 392 3553

E-mail: lewis.goodings@roehampton.ac.uk

URL: http://www.roehampton.ac.uk/staff/LewisGoodings

Goodings, Lewis (2011). The Dilemma of Closeness and Distance: A Discursive Analysis of Wall Posting in MySpace [46 paragraphs].

Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 12(3), Art. 16,

http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs1103160.