Volume 12, No. 3, Art. 15 – September 2011

The Rewards of a Qualitative Approach to Life-Course Research. The Example of the Effects of Social Protection Policies on Career Paths

Joan Miquel Verd & Martí López

Abstract: This article highlights the benefits of incorporating the qualitative perspective, and in particular the use of life stories, in studies based on the life-course perspective. These benefits will be illustrated using as an example a study of the effects of social protection measures on career paths based on the theoretical underpinnings of SEN's (1987, 1992, 1993) capability approach.

The life-course perspective is a very good methodological option for evaluating the extent to which social protection systems are adapted to the present situation in labor markets, where many trajectories are non-linear and unstable. Studies adopting such a perspective use research designs in which secondary statistical data are central, whereas qualitative data are used little, if at all. This article will explain how these quantitative approaches can be improved by using semi-structured interviews and a formalized qualitative analysis to identify turning points, critical events, transitions and stages, in which social protection measures and resources play a significant role in redressing or channeling personal and career paths. Paying attention to the person and his or her agency—not only at a given time but in a broader perspective that embraces past episodes and projections into the future—is essential in order to consider how individuals use the resources at their disposal and to effectively evaluate the effects of social protection measures.

Key words: life stories; life-course research; mixed methods; social protection; capability approach

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. Career Paths and Life Course

2.1 The destabilization of biographical trajectories

2.2 Main elements of the life course perspective

3. Life Course, Social Protection and Capabilities

3.1 Longitudinal approaches to the evaluation of social protection systems

3.2 The capability model

4. Methodological Challenges in Combining the Life Course and Capability Approaches

4.1 What does the use of life stories add to the life course perspective?

4.2 What does the use of life stories add to the capability approach?

5. The Research Design and the Articulation of Quantitative and Qualitative Information

5.1 The design and selection of cases

5.2 Interpretation and analysis of life stories

5.3 Data processing

6. Conclusion

The use of qualitative methods is very often restricted to research subjects related to the "inner world" of actors—their motivations, meanings, representations, emotions and other subjective aspects (SCHWARTZ & JACOBS, 1984 [1979], p.22). This world is also studied using life stories, in which an even greater emphasis is placed on the symbolic systems of the actors (DENZIN, 1989) or on identity issues (GIARRACA & BIDASECA, 2004; ATKINSON & DELAMONT, 2006, p.xxiii). [1]

However, the use of the qualitative perspective can go beyond the most purely emic elements. Its unique ability to see and place events in their own contexts (MUNCK, 2004) allows one to address the actions of individuals in interrelation with those external factors whose influence may be outside their own awareness. Furthermore, as highlighted by MILES and HUBERMAN (1994) and MASON (2006), among others, a close view of the qualitative perspective and its holistic approach is the best way to identify the causal mechanisms and relationships between events. These two aspects allow one to establish generalizations (using comparative logic) that go beyond idiographic features and particular contexts. Accordingly, the chance to see social action and experience situated in context makes it possible to develop fine-grained explanations which often articulate, and therefore go beyond, the strictly micro- or macro-sociological level (MASON, 2006, pp.17-18). [2]

These generic principles can be applied perfectly to the use of life stories. Along with the motivations, meanings or representations, life narratives let us see the fabric and texture of events and their longitudinal interrelation (PUJADAS, 1992, pp.44-45). This "objectivist" use requires a realistic principle that not all authors share, though it has been vigorously supported by BERTAUX (1997) and THOMPSON (2004), who defend the relevance of the story as a means of access to "objective" reality beyond the narrator. Thus though one's own account involves mediation, it is always possible to reconstruct "the diachronic structure of situations and events that have marked this [biographical] path" (BERTAUX, 1997, p.37). [3]

This article adopts the realistic approach.1) More specifically, it argues that life stories are a suitable tool for identifying key moments in people's work biographies and for examining in detail the resources that they had at those moments, how the stories were used and with what intentions. We take as a guideline a research project called CAPRIGHT,2) whose final objective is to assess the extent to which social protection policies contribute resources that are valued and useful to the people in developing their own biographies. As noted above, this may not be the most widespread use of life stories today, but we believe that this project exemplifies its benefits. [4]

One of the objectives of the CAPRIGHT project is to make a longitudinal evaluation of the different social protection policies related to employment that exist in different European countries. To this end, as a regulatory framework we used SEN's capability approach, details of which will be presented below. In terms of methodology, we adopted a longitudinal biographical perspective, largely inspired by the life course perspective, which takes into account the trajectories of workers and the type of protection offered at different moments and stages in their careers.3) [5]

As will be seen, the distinctive feature of the research in comparison with the (few) studies that have so far addressed the evaluation of social protection policies from a longitudinal perspective is the use of SEN's capability approach, and a predominantly qualitative perspective. The combination of these two elements involved a set of methodological challenges that were met by means of a mixed design, in which the use of life stories played a central role. The rationale and description of this use form the core of this paper. [6]

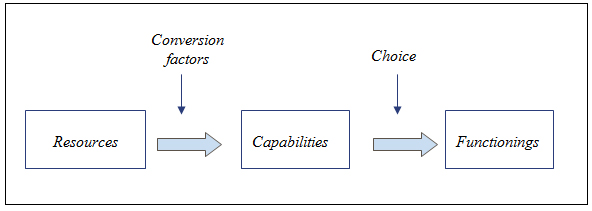

2. Career Paths and Life Course

2.1 The destabilization of biographical trajectories

The changes in the labor markets of Western countries since the eighties have produced work biographies that bear little comparison to the smooth, stable careers typical of the 1950s and 1960s. In addition to the effects of deregulation and flexibilization policies (JESSOP, 2002), in Europe one must add the effects of policies aimed at integrating women into the labor market, in what has been called the "adult worker model" (LEWIS, 2001; ANNESLEY, 2007). Both measures have led to enormous changes to the traditional (and male) sequencing of life in three stages: education, paid work and retirement. Today, these stages have different durations for different people, may overlap wholly or partly and may occur with several transitions from one situation to another (KLAMMER, 2009). [7]

The onset of these changes in biographical paths almost coincided in time with the development of the life course perspective, which is claimed by some authors to be the predominant theoretical and methodological approach in the study of biographical trajectories (ELDER, JOHNSON & CROSNOE, 2004). The reasons for this go beyond the changes in the labor markets, and can be found in the growing interest in studying how persons live their lives in increasingly changing and unstable contexts.4) [8]

Although some precedents can be found in papers published during the 1950s (see GIELE & ELDER, 1998a; MAYER, 2005), there is a certain consensus (ELLIOTT, 2005; GIELE & ELDER, 1998a; MAYER, 2005; SAMPSON & LAUB, 1993) that ELDER's study "The Children of the Great Depression" (1999 [1974]) is one of the seminal works of this perspective. In this study the author identifies "four main factors that shape the life course: location in time and place, social ties to others, individual agency or control, and variations in the timing of key life events" (ELLIOTT, 2005, p.73). These elements prefigure those considered today to be the paradigmatic principles of the perspective, which are presented below. [9]

It is noteworthy that the life-course perspective has come to play an increasingly important role in the design of European Union policies (see KLAMMER, 2004; KLAMMER, MUFFELS & WILTHAGEN, 2008; KLAMMER, 2009). Today, this approach is linked not only to the "economic, employment and labour market policies, but also pension, social and equal opportunity policies, the debate on the quality of life, the aim of active ageing and the European social policy agenda" (KLAMMER et al., 2008, p.5). [10]

Although traditionally the term "life course" has been used more in the United States and the term "life cycle" more in Europe, it is not by chance that the European Union prefers the former. Whereas the life cycle is used in demography and population studies to refer to established and even "biologically" determined pathways, the life course has a more personal and individual connotation, even more closely linked to aspects of agency and reflexivity in the development of a person's life path (ELLIOTT, 2005, p.73; ELDER et al., 2004, pp.4-5). Nevertheless, the concepts used and the methodological approach are largely overlapping. [11]

2.2 Main elements of the life course perspective

Before presenting the principles underpinning the life course perspective, we will offer an initial definition taken from GIELE and ELDER:

"The key building block elements of the new life course paradigm are events combined in event histories or trajectories that are then compared across persons or groups by noting differences in timing, duration, and rates of change. [...] No longer are the principal questions ones of comparing static qualities such as how many and which people are poor; rather, the new dynamic questions focus on both individual characteristics and system properties. For example, typical questions that are encountered in cross-national comparisons of panel studies ask how life experiences differ by gender and cohort, which people are more likely to remain poor, and how the United States compares to other countries in the persistence of inequality" (1998a, pp.2-3). [12]

The perspective presented above is based on five basic principles (GIELE & ELDER, 1998b; ELDER et al., 2004) that can be summarized as follows:

Time and place: the individual situation of each person in historical and cultural terms affects personal experience and the ways of developing the life course.

Linked lives: the social action of individuals interacts with, and is reciprocally influenced by, relationships with others, who share similar experiences.

Human agency: people actively make decisions about their objectives in the context of the opportunities and constraints marked by history and social circumstances.

Timing: similar events and characteristics experienced at different times in life have different consequences on the lives of people.

Life-span development: life-span development can only be understood by taking a long-term perspective, considering substantial periods in people's lives. [13]

The principles noted above are developed through the use of three basic empirical indicators that articulate the analyses, with varying emphasis according to the author: trajectory, transition and turning point. [14]

The idea of a trajectory or pathway5) refers to the succession of situations that occur longitudinally throughout life. As BYNNER (2005, p.379) points out, "each step along [the pathways] is conditioned by the steps taken previously, by the personal, financial, social and cultural resources to which the growing individual has access, and by the social and institutional contexts through which the individual moves." Though it is not always used, the distinction RUNYAN makes between stages and states is interesting. The type of analysis he defends is based on the combination of the two concepts: "A stage-state analysis makes the simplifying assumption that the life course can be divided into a sequence of stages and that a person can exist in one of a limited number of states within each stage" (1984, p.101). The concept transition refers to the changes in state that take place in short spaces of time throughout the biographical trajectory. As SAMPSON and LAUB argue, "some transitions are age-graded and some are not; hence, what is often assumed to be important are the normative timing and sequencing of role transitions" (1993, p.8). The time between two transitions is known as the duration (ELDER et al., 2004, p.8). [15]

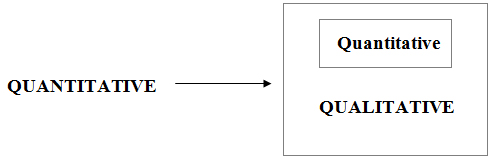

For its part, the concept turning point "involves a substantial change in the direction of one's life, whether subjective or objective" (p.8). Not all transitions involve the existence of a turning point. Citing ELDER (1985, p.35), SAMPSON and LAUB stress that "adaptation to life events is crucial because the same event or transition followed by different adaptations can lead to different trajectories" (1993, p.8). Ultimately, whether or not a change becomes a turning point depends largely on the personal characteristics and the resources available to the person. Turning points also reflect "the effective exercise of agency in both creating and responding to new opportunities" (BYNNER, 2005, p.379). [16]

As can be seen, the life course perspective is interested in particular in the sequence of events that have marked a biographical trajectory. To this end, it usually adopts an aggregate perspective, taking one or more generations or cohorts as the focus of analysis. As RUNYAN (1984, p.82) stated, the approach "puts greater emphasis on the influences of changing social, demographic, and historical conditions upon the collective life course." This involves working mainly—but not exclusively—with quantitative data. Case-centered studies are still a minority compared to variable-centered studies, although the introduction of case-centered information often leads to further refinement in the analysis, thus avoiding an excessively "deterministic" logic (see SAMPSON & LAUB, 1993; SINGER, RYFF, CARR & MAGEE, 1998; and SINGER & RYFF, 2001). [17]

In this article, we defend and exemplify the benefits of using qualitative information. These benefits have also been mentioned by other authors, though still a minority. HEINZ (2003) is clearly in favor of the use of life stories in life course studies, either through biographical interviews or by reconstructing the biographies from survey data (when the wealth of data and number of years covered in panel surveys allow it). Also, though COHLER and HOSTETLER (2004) state that life stories are little used, they clearly illustrate their benefits in life course studies. This is the line followed in the rest of the article, in which we do not take these benefits as being axiomatic, but highlight the theoretical questions that raised the need for qualitative information in the CAPRIGHT project, and show how the use of qualitative materials allowed us to answer these questions. [18]

It is interesting to note that the concept of trajectory is not always considered to be the most appropriate for describing the life course of individuals. HEINZ (2004) rejects it because of its semantic association with the curve of a ballistic missile, which implies a latent meaning of continuity and predictability. In the Spanish language this problem is solved by some authors by using the term itinerary, though more as a synonym than an alternative (GARCÍA BLANCO & GUTIÉRREZ, 1996; MASJUAN, TROJANO, VIVAS & ZALDIVAR, 1996; PLANAS, CASAL, BRULLET & MASJUAN, 1995). BERTAUX (1997, p.33), prefers to speak of a "life line." Here, we will use the habitual term trajectory, which does not (in the sense used) indicate a visible direction, but merely the longitudinal direction and succession of experiences, without necessarily a knowledge or awareness of the direction that is being followed. [19]

3. Life Course, Social Protection and Capabilities

3.1 Longitudinal approaches to the evaluation of social protection systems

Given the instability in career paths (and more generally in life courses) that we mentioned briefly in Section 1.1, it is difficult to design social protection and employment policies without considering their longitudinal dimension. It seems clear that the development of these policies should take into account the multiplicity of career paths that exist today and even the links of these pathways to life areas not connected to the labor market sphere. In this context, it makes sense to ask ourselves which social protection systems best deal with these situations of biographical change and instability. As noted by RUBERY,

"one of the best ways to conceptualize and consider both the differences in current models [of social protection] and the pressure under which they are placed for change is to view these models through the lens of a lifecycle approach" ( 2004, p.1). [20]

As noted in the introduction, one of the objectives of the CAPRIGHT project is precisely to consider, longitudinally and with an evaluative purpose, social protection policies related to employment. A few earlier studies have adopted this longitudinal perspective in the analysis and evaluation of public policies aimed at employment and social protection. SCHMID's works (1998, 2006) are perhaps the best known. His reflections on transitional labor markets are frequently cited, especially as a "guide to the analysis, management and coordination of existing and future labour market policies" (VIELLE & VALTHERY, 2003, p.81). [21]

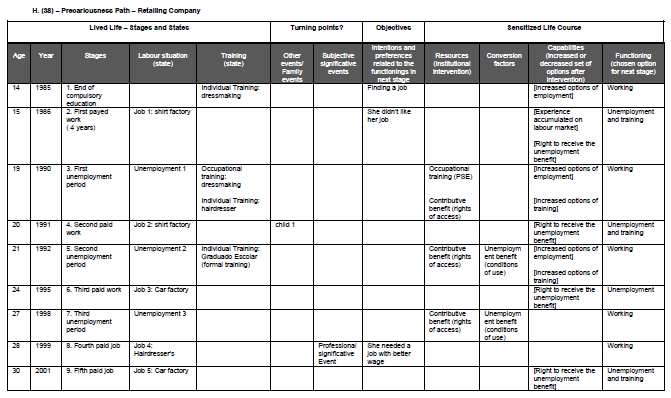

The various studies published by the European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions (e.g. ANXO & ERHEL, 2005; ANXO & BOULIN, 2005, 2006; ANXO, FAGAN, CEBRIÁN & MORENO, 2007; KLAMMER et al., 2008; KLAMMER, 2009) and some of the studies carried out within the DYNAMO project (2007) have been also inspired by the life course perspective.6) In the first group of studies (see a review in KLAMMER, 2009), the idea of a biographical trajectory is used primarily as a way to address the different uses of time between men and women from a longitudinal perspective. In the second group (RUBERY, 2004; ANXO, BOSCH & RUBERY, 2010) the objective is to evaluate social protection systems considering the resources offered in key biographical phases and the forms of informal support from the family environment in these phases. [22]

It is important to note that none of the studies reviewed takes into account one of the key elements in the life cycle perspective: the effective development of agency. In other words, the evaluation exercises do not regard—at least explicitly—either the individual preferences or the degree of possibility of choice that public policies offer to people. Considering this dimension would mean that social protection measures were also evaluated on the basis of the level of constraint imposed on individuals. For example, models based on workfare should be evaluated differently from those that involve no obligation for recipients of the measures (BONVIN & FARVAQUE, 2005). [23]

HEINZ (2004) has highlighted clearly the importance of paying attention to individuals and their choice when dealing with career paths. Herein lies the originality of the CAPRIGHT project's approach: it focuses on the possibility of individuals' choice and the extent to which social policies constrain or extend this choice. [24]

This re-centering of the subject is made in the CAPRIGHT project by taking Amartya SEN's capability approach as an "enriched informational base of judgement" (BARTELHEIMER, MONCEL, VERD & VERO, 2009, p.23) of social protection policies related to employment. SEN's work stands out precisely because it places freedom of individuals' choice at the center of the model. Accordingly, personal welfare or satisfaction is judged not according to the utility provided, but according to a person's ability to lead the life (understood as trajectory) that they consider to be desirable (SEN, 1987, 1999). The capability approach is not an explanatory theory of equality or welfare (or the lack thereof), but a regulatory and evaluative framework that could be applied in several areas. This basic evaluation is based on a notion of equality in a person's capability to achieve what they want to be or want to do—what SEN (1987) calls capability to function. We will now give a brief explanation of this model. [25]

As stated by GASPER (2007), there are four main characteristics that make the capabilities approach interesting for evaluation:

It establishes the intuitively attractive idea that people should enjoy the same real freedom regardless of their formal rights.

It goes beyond subjective satisfaction, recognizing that preferences and values sometimes have an adaptive character, so in certain circumstances it will be necessary to consider the extent to which the choices made have a suitable information base and correct reasoning.

It takes into account individual differences in preferences and goals, so it is not based on general situations that are universally preferable to others.

It is primarily concerned with people's ability to transform their resources into functionings, as compared to models that focus on the amount of resources available to individuals. [26]

In short, the capability approach places "real freedom" of individuals' choice at the center of the model. SEN (2002a, 2006) considers this freedom to have two different aspects: the procedural aspect and the opportunity aspect. The latter refers to the possibility for individuals to become agents, to influence facts that are relevant to their own lives, whilst the former has to do with the possibility of actually achieving the desired situations, even when an outsider to the individual must make the decision (SEN, 2002b [1983]). [27]

The analytical framework of the capability approach is based on three key concepts: resources, capabilities and functionings (see Figure 1). The first basic conceptual distinction is between capabilities and functionings. According to SEN, "The capability of a person reflects the alternative combinations of functionings the person can achieve, and from which he or she can choose one collection" (1993, p.31). Thus, the capabilities reflect the real set of options a person has at hand. Furthermore, the functionings are the set of ways of being and doing that a person ultimately puts into practice. The distinction between capabilities and functionings is the same as that between what is possible and what is effectively carried out.

Figure 1: Analytical framework of the capability approach; relationship between resources, capabilities and functionings7) [28]

The distinction between resources and capabilities is also of great importance. Resources are understood to be the set of rights or entitlements and commodities that are assigned to a person in a given context (SEN, 1999). The focus on capabilities places the emphasis on the conversion factors that can hinder or facilitate the transformation of resources—understood as means—into effective freedom (SEN, 1985). This is the main reason why the evaluation procedures should not focus on resources but on the conversion of formal rights into real rights or capabilities. Therefore, in the capability approach, an appropriate public policy is that which combines the guarantee of rights or goods and services with the establishment of appropriate conversion factors. [29]

It is important to note that in general the capability approach has been developed and applied empirically from a quantitative perspective. This should not be surprising if we remember that SEN and most authors who have applied the capabilities approach come from the field of economics. ROBEYNS states this predominance of quantitative approaches within the capability approach, but also mentions the existence of qualitative approaches oriented towards descriptive analysis and "thick description" (2005, p.193). In our opinion, qualitative approaches have quite a lot more to offer. Qualitative development of the capabilities approach can realize the full analytical potential of SEN's work. We defend this view below. [30]

4. Methodological Challenges in Combining the Life Course and Capability Approaches

As can be seen, the capability model is fundamentally abstract and open. It is therefore suitable for a variety of research problems, but needs to be developed in order to be successfully used in an empirical approach such as that of the CAPRIGHT project. In this section we specify precisely how the CAPRIGHT project combines the potential of the capability approach with a life course perspective aimed at evaluating social protection policies. [31]

It has already been mentioned that the quantitative methodological perspective has dominated both the life course perspective and the capability approach. However, in this section we put forward the need for qualitative development of both approaches in order to achieve the full potential of each perspective and to articulate and integrate them with each other, an objective that lies at the heart of the CAPRIGHT project. It should be noted that our defense of the qualitative approach, and specifically of the use of life stories, does not mean that we underestimate the value of a quantitative perspective. In fact, rather than defending an exclusively qualitative approach we are in favor of a mixed design and the application of the fundamental principle of this type of design (TEDDLIE & TASHAKKORI, 2003, p.16): "Methods should be mixed in a way that has complementary strengths and nonoverlapping weaknesses."8) [32]

4.1 What does the use of life stories add to the life course perspective?

As mentioned above, the career paths of individuals are currently developing in a way that is far removed from the linearity of the 1950s and 1960s. As shown by KRÜGER (2003), HEINZ (2004) and MAYER (2005), among others, this plurality and fragmentation of the modes of production and reproduction of careers can potentially produce greater opportunities to intervene in the definition of biographical trajectories. However, it can only be argued that this fragmentation and destandardization of trajectories increases the degree of individual agency if people are really able to choose from a large number of options for participation in the labor market. To identify this degree of agency it is necessary to determine the influence of institutional and structural factors on individuals.9) It is also essential to address the self-reflective nature of decisions, which involves adjustments and learning that cannot be understood without knowing the individual trajectories and the interpretation of these trajectories made by the actors (HEINZ 2004). [33]

This need to give greater prominence and detail to the role of the individual and his or her agency has not been considered until very recently. DIEWALD and MAYER (2008) consider that life course sociology has moved from the "structure without agency," leaving the aspects most linked to agency "under the sociological radar," to the current notion of "agency within structure." In order to improve the predictive power of the approach, these authors propose "to supplement individual level information collected via surveys, by information about social contexts, like neighbourhoods or work organizations, measured independently from the survey respondents" (2008, p.17). In our opinion this informative complement can be perfectly achieved using qualitative biographical interviews. In life stories we obtain not only all the aspects directly related to agency (objectives, representations, motivations, etc.), but also rich contextual information (BERTAUX, 1997; JOVCHELOVITCH & BAUER, 2000). This contextual information corresponds to what CLANDININ and CONNELLY (1994) call the outward dimension of personal experiences, i.e., living conditions, contexts and events "outside" the subject. [34]

Another way to identify the degree of individuals' agency in their biographical trajectories, is to make an analytical distinction between causalities attributed to circumstances outside the subject and causalities attributed to objectives or desires inside the subject. BERTAUX (1997, p.75), following SCHÜTZ, calls the first type of circumstances "reasons because" and the second type "reasons in order to." These causes must be studied by the analyst, who should use as much contextual information as possible to assess the degree of freedom offered by the subjects' environments. [35]

4.1.2 Transitions and turning points

Another advantage of using life stories is the possibility of identifying without too much trouble the moments of biographical disruption or turning points that are important to individuals. The ideas of a crossroads, bifurcation or "point of no return" are constant in biographical narratives. LAHIRE notes the importance of "drawing out moments of 'biographical disruption', changes or amendments, even slight, in trajectories or careers [...] because they are the moments when provisions can be placed in question or suddenly reactivated when they had previously been dormant" (2002, pp.30-31, our translation, original italics). The use of only quantitative data makes extremely difficult to distinguish between voluntary and involuntary biographical disruptions, and can even be misleading, since transitions can be confused with turning points. Besides, events that objectively would not be qualified as turning points may be constructed subjectively as crises or turning points (DENZIN, 1989, RIESSMAN, 1993). As DIEWALD and MAYER (2008) have argued, the life course tradition in sociology may too often have considered that the trajectories are mostly the result of institutional and structural aspects, whereas individual agency is also a key element in the orientation of a trajectory and its changes in direction. The same authors complain that sociologists working in this perspective "hardly look at individual decision-making, perceptions, and evaluations of the social situation" (p.9). [36]

This almost exclusive consideration of institutional and structural aspects has led researchers studying career paths to consider only factors related to the labor market (and sometimes to social protection and business). This has important consequences in the identification of biographical turning points. As HEINZ (2004, p.196) has stated, current life course research "reflects the dominance of the labour market institutions and neglects the person's involvement in the institutions of family life." There are not many alternatives to using life stories in order to identify turning points that affect the workplace but are caused by events outside it, such as the birth of a child, divorce or death of a close relative. These events are not always reflected in panel surveys targeting labor issues and even when they are reflected (usually in very general surveys), it is difficult to know whether these events have subjectively marked "a before and after" in the biography. [37]

4.2 What does the use of life stories add to the capability approach?

4.2.1 Actors' choices and identification of sets of capabilities

As noted above, adopting the capability approach as an evaluation tool of social protection policies involves analyzing primarily the options that these policies offer to people. Policies that allow actors a greater set of possibilities for action in comparison to the situation prior to the intervention should be the ones most highly valued from a regulatory standpoint. [38]

This objective however, comes up against the problem that it is impossible to observe capabilities (i.e. the whole set of possibilities for action) directly. Figure 1 shows that we can observe the results of the actors' choices and functions, but not the set of options from which they can choose, as we (researchers) do not usually know the possibilities that are available to them. The full set of options may be unknown even to the actors. The classical view in utilitarian economics is that the choice made is the best of the possibilities, but this reasoning follows a model of "revealed preference" that has been criticized by SEN (1999, pp.14-16). One way to avoid this type of inference10) is to examine the "context of choice" and the complete vectors of functions instead of taking isolated cases (SEN, 1992). BURCHARDT and VIZARD (2007) are in favor of a similar procedure: they propose a detailed analysis of individual functions, supplemented by the consideration of the degree of control that individuals have exercised over their choices. However, this examination of the context of choice is extremely difficult, if done using only quantitative data. As SEN himself has acknowledged, considering how the actors would have acted in situations of "real freedom" (without constraints that lead to choices involving an impairment in the well-being) involves a counterfactual analysis (1999, Ch. 3). Qualitative approaches provide the kind of intensive information that is necessary for this type of reasoning. The analysis of counterfactual situations requires knowledge of as many details as possible of the contexts of action, which means in practice performing a thorough analysis of the internal and external reasons that have led the actor to make a particular choice. Indeed, an analysis that uses life stories as the main empirical material places the individuals and their practices and experiences (along with all relevant contexts) at the center of the analysis. The importance given to taking into account actions and their contexts is closely related to the agency issues addressed above, and is a clear interface between the life course and capability approaches. [39]

4.2.2 Resources and conversion factors

An alternative means of identifying the capabilities available to individuals is to study the conversion factors that mediate between the resources that an individual could potentially use and those that can factually use (see Figure 1). This is an avenue rarely transited in studies evaluating public policies. It requires a great deal of contextualization and necessarily involves asking about the factors that produce unequal access to resources. ROBEYNS (2003) divides the conversion factors into three groups: social (social norms, prejudices, cultural and religious factors, etc.), personal (skills, competences, knowledge, etc.) and environmental (place of residence, infrastructure, etc.). Many of these factors are easily identifiable by means of life stories, especially those related to personal matters. However, the identification of social or environmental factors requires a contextualization of the trajectories analyzed and of the stories obtained, which requires the use of information not obtained through the story. This kind of information will be discussed when we deal with the type of design that led to the interviewees' selection. [40]

4.2.3 Introducing the time dimension

Despite the problems identified in the above paragraphs, as yet few authors who have developed SEN's capability approach empirically recognize the need to incorporate qualitative data. ROBEYNS (2005, p.194) indicates its usefulness for dealing with "behaviour that might appear irrational according to traditional economic analysis, or revealing layers of complexities that a quantitative analysis can rarely capture." FARVAQUE recognizes (2008, p.70) that a solely quantitative operationalization is unlikely to capture the processes and conditions of choice, so there is a great risk that the way in which the decisions were made will remain concealed. The need that we have detected may be partly due to the fact that we do a longitudinal adaptation of a model that is initially static. The dynamic nature makes the model more complex and also reveals more clearly this need for qualitative information. [41]

If one wishes to "understand" the subjects' decisions by linking them to key moments or significant biographical transitions, biographical factors must be considered in addition to those that are not strictly biographical. The following statement by ZIMMERMANN also shows the importance of the biographical perspective in attempting to develop a research methodology based on the capability approach:

"Paying attention to the person and her agency not only at a given time but in a broader perspective that embraces past episodes as well as projections into the future, is essential for considering work and employability from a capability prospect. Such a temporal concern designs trajectories and shifting moments as core elements of inquiry" (2006, pp.478-479). [42]

ZIMMERMANN (2006) also notes that preferences and what people value are path dependent. Individuals continuously adapt their preferences based on their past experience. HEINZ (2004, p.193) had already expressed this line of thought: "the experience of job shifts, unemployment, and career breaks is interpreted in the context of the person's work biography." [43]

5. The Research Design and the Articulation of Quantitative and Qualitative Information

As mentioned above, the decision to use life stories as a central technique of data collection in the CAPRIGHT project does not mean that the contribution of quantitative information is neglected. We have already annotated the importance of understanding the institutional and structural constraints in order to correctly assess the relevance of the actors' agency. We have also repeatedly pointed out the significance of correctly contextualizing the trajectories analyzed, as a way to compare the information provided in the story, either as a strategy for achieving a better interpretation of the events described, or even as a means of identifying potential life course developments that are unknown to, or not considered by, the actors in their stories and reflections. The role played by quantitative information in the project has been outstanding in relation to both the overall research design and more practical aspects, such as the selection of the information units and the data analysis. Let us consider these contributions separately. [44]

5.1 The design and selection of cases

As stated by THOMPSON (2004) and ELLIOTT (2005), among others, biographical information is reinforced by the use of quantitative and qualitative data. However, this combination is only meaningful if it is based on a good design. It is not a question of pasting together data of the two types, but of devising a selection of units and a data collection system that follow a certain methodological logic and meet certain theoretical requirements. HEINZ (2003), in his defense of the combination of quantitative and qualitative data in the context of the life course perspective, advocates the use of sequential designs. This was also the type of design that we used, although combined with a concurrent design. [45]

Figure 2 shows the type of design we used in schematic form. To use the terminology proposed by CRESWELL (2003; CRESWELL & PLANO-CLARK, 2007), it can be described as the integration of a sequential design and a concurrent nested design. A sequential design is one that places the acquisition and analysis of one type of data (quantitative or qualitative) in a separate phase and prior to the collection and analysis of another type of data (quantitative or qualitative). Then the two kinds of data are integrated into the interpretation of the results. A concurrent nested design is one that exploits quantitative and qualitative data in the same stage, so each type of information is used to measure different but complementary aspects of the same object of study. It is called "nested" because there are often data that are more central than others (some data are nested in other data), though it is also conceivable that both types of data are of similar importance. In our case, the qualitative information (life stories) of this second phase has greater weight than the quantitative information. [46]

The overall design thus combines the characteristics of a sequential design and a concurrent one. In the first phase we carried out a cluster analysis of the statistical data provided by the Inequalities Panel of the Jaume Bofill Foundation.11) In this analysis we selected persons aged 25 to 65 years, who had been active at some time in the period 2001-2008. We eliminated the population under 25 years to reduce the distortions caused by the limited time spent in the labor market (in many cases less than five years) and by the fuzzy dynamics of integration in the labor market.12) [47]

This initial analysis identified five main types of trajectory: the Linear Trajectory (40.63% of cases), the Professional Trajectory (21.11% of cases), the Female Discontinuity Trajectory (7.72% of cases), the Precariousness Trajectory (21.45% of cases) and the Chronic Temporary Employment Trajectory (9.1% of cases). Subsequently, this typology was used in the second phase to select the interviewees. Concretely, a set of 30 individuals whose characteristics fitted one of the five types was selected to carry out biographic interviews. Also in the second phase, the same quantitative data were used to develop a whole set of multinomial logistic regressions, which revealed the macro-scale causal logics existing in the whole population and complemented the information provided by the interviewees in their life stories. This articulation in the second phase did not strictly seek a mutual validation because the two types of data and their analysis followed different logics. Instead it sought a dialogue that would provide a better interpretation of the stories and an identification of the mechanisms behind the observed statistical correlations.

Figure 2: Design and articulation of methods developed in the research [48]

As shown, the design sought to combine the potential of using intensive and extensive information. Some years ago HARRÉ and De WAELE mentioned the logic of both types of information (1979, p.198): the more deeply an individual is studied, the fewer individuals can be studied. As SARABIA (1985) states, in extensive (i.e. quantitative) designs we ideally examine all the individuals of the same class; if this is not possible, we use a sample from which we obtain a type through averages of characteristics derived from the sample. Intensive (i.e. qualitative) designs involve examination of a typical member, and the extension of the class is derived from the common properties relevant to other members. To take advantage of both designs one must identify a typical member included in a given extension. Once the subject has been selected, he or she may be subjected to an intensive examination that would provide detailed knowledge of the type considered. Obviously this logic is based on the assumption that the extension from which the type is extracted is homogeneous. In our case, as it was impossible to interview the members of the original sample, we performed purposive sampling in which individuals selected for biographical interviews had characteristics coinciding with the prototypical profiles of each of the identified trajectories. These typical cases (FLICK, 2009, p.122) are considered representative of the majority of cases classified in each type of trajectory. [49]

5.2 Interpretation and analysis of life stories

The quantitative information and its analysis were not only useful for selecting and identifying the people that would be interviewed in the second phase. The statistical information and a host of additional information mentioned below also played an important role in the analysis of the biographical accounts. [50]

Let us recall that in the biographical accounts we sought primarily what authors such as ROSENTHAL (2004) and WENGRAF (2001) have called the "lived life," i.e. the sequence of events and actions experienced by the interviewee which constitute the material basis of the story (on this, see also LIEBLICH, TUVAL-MASHIACH & ZILBER, 1998, pp.7-9). The "lived life" can be separated analytically from the "told life," or the way in which the events experienced are narrated. WENGRAF (2001, pp.236-239) stresses the importance of considering "uncontroversial hard biographical data" in the analysis and reconstruction of the lived life. This is the role played by the statistical analyses that were performed. The possibility of placing the interviewees in a certain type of trajectory allowed us to contextualize the stories and reflections made by individuals, and to obtain a scenario with which to compare the factual information if necessary. [51]

In addition to statistical data, this contextualization was achieved by obtaining information on the sectors and companies in which the interviewees worked. This work was facilitated by the fact that, as far as possible, the company in which the interviewees worked was constant. With the exception of the two minority profiles (Chronic Temporary Employment and Female Discontinuity, which together represented only 16.8% of the cases) the interviewees were selected from the workers of only two companies: a chain of supermarkets and a public municipal transport company. This allowed a second level of contextualization: by gathering documentary information and interviewing human resources managers of both companies, we obtained additional information on recruitment policies and labor management. This information was very important for identifying institutional factors related to corporate policies that had influenced the career paths that we were analyzing. Furthermore, having this institutional level as a constant facilitated the comparison of trajectories. [52]

This collection of additional information (quantitative data on the trajectories and qualitative data on the corporate policies and the labor regulations in Spain) allowed us to correctly situate the degree of agency exercised by the actors, and gave us a better understanding of the actions and motivations. Furthermore, we had sufficient institutional and contextual information to identify the influence of these levels on the trajectories analyzed. On this point, we think we are close to the recommendations of HEINZ (2004, p.195) on the analysis of career paths:

"[I]t is important to discern the degree of choice in the timing and sequencing of transitions between jobs, occupations, and firms and the extent to which institutions facilitate or restrict multiple participation in different institutional fields, for example, university and company, family and paid work, retirement and part-time employment. Macro-, meso-, and micro-social analysis is needed to understand the impacts of social change on the coupling of work (re)structuring, labor market participation, and employment careers over the life course." [53]

We end this section by noting the type of data processing that this kind of contextualized and "realistic" interpretation allowed. Let us recall that the ultimate goal of the analysis was to determine the degree to which social protection policies expanded the possibilities available to workers in certain situations of need for support. In the project carried out in Spain, these situations were analyzed mainly on the basis of periods of unemployment. These labor situations, which involve the provision of a particular social protection, are understood to be potential turning points, possibly leading to situations of special vulnerability. Therefore, the objective was to obtain information that was as exhaustive as possible on situations of entitlement to institutional support (occupational training or a contributory or non-contributory benefit). The aim was to see whether and how this support had been used and finally to explore whether the use expanded the choice of the people who received it. In the language of the capability approach, we wished to identify the extent to which institutional support extended the set of capabilities of the people, and the functioning (mediated by the people's choice) resulting from the identified set of capabilities. [54]

The type of data analysis used corresponds to that which LIEBLICH et al. (1998) called categorical-content reading. This type of analysis focuses on the content of narratives, although in our case we took a more holistic approach than that attributed to it by the above authors (LIEBLICH et al., 1998, pp.16-17). In our case, we wanted a picture with the highest possible level of contextualization; more particularly we wanted to obtain the representations, attitudes, motivations and goals that led the actors to make certain decisions about their biographical trajectories. The results of the analysis, in tabular form (see Figure 3), show some similarities with those that BALAN, BROWNING, JELIN and LITZLER (1974 [1968]) used in their approach to the analysis of life stories, although they collected the data by survey and their analysis was also quantitative.13) From the results presented in the tables and all the quantitative and qualitative information mentioned above, the conclusions were drawn up. [55]

The life stories were not transcribed, but their digital recordings were encoded directly using the ATLAS.ti program. The coding was aimed primarily at identifying the various stages and transitions in the career paths of the respondents. After identifying these stages (see Figure 3), we encoded four main dimensions of each stage: 1. states for the stage (employment status, training or other relevant events), 2. whether or not there was an event or events that could be considered a turning point, 3. intentions and preferences of the actor for the immediate future, and 4. resources, conversion factors, capabilities and functionings (choices that give rise to a new stage). [56]

With regard to the above aspects of the encoding, it is important to stress that we decided to identify the turning points defined subjectively (although we could have decided to define them objectively). It is also interesting to note the great complexity of the empirical transfer (the operationalization) of the "conversion factor" concept, even in qualitative terms. As it has been defined by SEN (1999) and ROBEYNS (2003), a conversion factor is a characteristic or circumstance that prevents or facilitates a person's actual use of a potentially usable resource. The problem is that "positive" conversion factors are difficult to be identified by respondents: when a resource available to the person is used, we understand that its use is permitted by the person's whole set of characteristics, although the latter is very difficult to become an exhaustive list. In life stories it is much easier to identify conversion factors that represent obstacles (i.e., those that prevent the conversion of resources into capabilities), since they are experienced as factors that prevent real access to particular resources.

Figure 3: Example of a table of stages in the career path of one interviewee (enlarge this figure here) [57]

This paper has attempted to show how the use of life stories can substantially improve research that, with a more "objectivist" orientation, is concerned with the sequence of events in biographical trajectories. It has highlighted the benefits of a qualitative approach in terms of contextualizing actions and identifying the degree of agency that individuals may exercise. To some extent, context and agency are inseparable, and it is precisely the holistic perspective provided by life stories that allows them to be distinguished analytically. [58]

This use of life stories does not exhaust their possibilities. Our use has focused on what has been called "lived life." The analysis of "told life" is a vast field of analysis, with highly successful applications that we have not considered here. [59]

The exclusive use of life stories does not allow one to address subjects that are beyond the knowledge or subjectivity of persons, such as the potential resources they may have and the institutional or contextual constraints imposed on the action. These issues must be addressed with other types of information that are not necessarily quantitative. In our case we used longitudinal statistical data in addition to qualitative information that identifies the framework of action of workers, both in the job market and in the companies where they work. [60]

This combined use of quantitative and qualitative data cannot be performed without an overriding logic. Only a research design that explicitly grants each type of information its role in the overall study will achieve success. We thus again see the importance of a methodological and epistemological reflection previous to the research design. [61]

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Miguel S. VALLES for his splendid work in organizing the workshop on "Archives and Life-History Research in Europe," held in Madrid (September 21-23, 2009) within the EUROQUAL program , and funded by the European Science Foundation. We also wish to express our gratitude to him and the rest of coeditors for coordinating this Special Issue. Finally, we are in debt with all the colleagues of WP3 (Individual working lives: collective resources and employment quality) of the CAPRIGHT project, for their valuable comments at various stages of the research that we have presented in this article.

1) By making explicit our methodological stance, we want to acknowledge and praise paradigmatic diversity within research methods, and more concretely in biographical research. The variety of papers presented in the workshop on "Archives and Life-History Research in Europe" (see Acknowledgments at the end of the article) is a good indicator of the good health of this paradigmatic diversity. Some of the authors of the book "Doing Narrative Research" (ANDREWS, SQUIRE & TAMBOUKOU, 2008) presented in the workshop excellent pieces of research based on the constructivist approach to biographical research, as opposed to our realistic approach. <back>

2) The CAPRIGHT project ("Resources, Rights and Capabilities: In Search of Social Foundations for Europe") was carried out between January 2007 and December 2010. It was coordinated by Robert SALAIS and funded by the Sixth Framework Programme of the European Commission (contract CIT4-CT-2006-028549). The 24 teams from 13 countries participating in the project were divided into three main subprojects. <back>

3) This methodological approach was not applied by all the research groups participating in the CAPRIGHT project. It was used in the following European countries: Germany, Austria, Spain, France, Italy, Romania and Switzerland. The details of the design and data analysis that will be given later correspond to the specific approach used by the Spanish group. <back>

4) The narrative-biographical turn that has been observed in the last thirty years in qualitative sociology may also be related to similar reasons, although this subject is beyond the scope of this article. On this topic, see BERTAUX (1997) and ATKINSON and DELAMONT (2006). <back>

5) Some authors (ELDER, 1985; PALLAS, 2004) distinguish between trajectory and pathway. PALLAS highlights the socially predefined nature of pathways as opposed to the open nature of trajectories: "A trajectory is an attribute of an individual, whereas a pathway is an attribute of a social system" (2004, p.168). <back>

6) For a fuller review of these approaches, see BARTELHEIMER et al. (2009, pp.40-41) and VERD, VERO and LOPEZ (2009, pp.132-135). <back>

7) Authors adaptation, based on BONVIN (2008). <back>

8) When the goal is international comparison, this quantitative-qualitative articulation is almost essential (although rarely practiced). BYNNER and CHISHOLM (1998) reviewed the problems of using exclusively either quantitative or qualitative data in the international studies on transitions: "Thus national cohort and cross-sectional survey studies will confront problems of interpretation of differences (and similarities) across countries, and biographical and ethnographic studies will confront questions of representativeness and generalizability" (p.146). <back>

9) As BYNNER points out, speaking specifically of the transitions between education and work, "in all countries the rates and forms of transition are strongly dependent both on institutional factors (how the transition from school to work is managed) and on structural factors such as social class, gender, ethnicity and locality" (2005, p.372). <back>

10) There have been some attempts to directly measure the capabilities of individuals, using data from surveys asking about the possibilities and limitations for achieving certain goals (ANAND, HUNTER & SMITH, 2005; ANAND & VAN HEES, 2006). The results were not completely satisfactory, since the individuals themselves have difficulty identifying these constraints or limitations. <back>

11) We analyzed the panel waves ranging from 2001 to 2006. This task would not have been possible without the help of Angels LLORENS, of the Fundació Bofill, who gave us invaluable support in accessing, organizing and processing the data and in the data processing problems that arose during the work. <back>

12) The following variables were considered: 1. frequency of temporary employment, inactivity and unemployment in the period; 2. transitions from temporary to open-ended contracts and from unemployment to employment in the first and last wave; and 3. the increase in educational attainment between the first and last wave, and conducting non-formal training in three of the five waves. The number of cases finally considered was 884. <back>

13) The approach of BALÁN et al. (1974 [1968]) inspired the well-known Life History Calendar technique (FREEDMAN, THORNTON, CAMBURN, ALWIN & YOUNG-DeMARCO, 1988). However, as pointed out by REIMER and MATTHES (2007), retrospective data collection through surveys involves the risk of recall error, and therefore doubts about the validity of the data. These problems are often more important when it comes to remembering episodes of short duration, which do not fit into a coherent life story (REIMER & MATTHES, 2007, p.715), a situation that in our case arose among people with trajectories of Instability, Chronic Temporary Employment and Female Discontinuity. <back>

Anand, Paul, & van Hees, Martin (2006). Capabilities and achievements: An empirical study. The Journal of Socio-Economics, 35, 268-284.

Anand, Paul; Hunter, Graham & Smith, Ron (2005). Capabilities and well-being: Evidence based on the Sen-Nussbaum approach to welfare. Social Indicators Research, 74, 9-55.

Andrews, Molly; Squire, Corinne & Tamboukou, Maria (Eds.) (2008). Doing narrative research. London: Sage.

Annesley, Claire (2007). Lisbon and social Europe: Towards a European "adult worker model" welfare system. Journal of European Social Policy, 17(3), 195-205.

Anxo, Dominique & Boulin, Jean-Yves (Eds.) (2005). Working time options over the life course: Changing social security structures. Dublin: European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions.

Anxo, Dominique & Boulin, Jean-Yves (Eds.) (2006). Working time options over the life course: New work patterns and company strategies. Dublin: European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions.

Anxo, Dominique & Erhel, Chistine (2005). Irreversibility of time, reversibility of choices? A transitional labour market approach. Working Paper No. 2005-07, TLM.NET Thematic Network.

Anxo, Dominique; Bosch, Gerhard & Rubery, Jill (Eds.) (2010). The Welfare State and life transitions: An European perspective. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Anxo, Dominique; Fagan, Colette; Cebrián, Inmaculada & Moreno, Gloria (2007). Patterns of labour market integration in Europe—a life course perspective on time policies. Socio-Economic Review, 5, 233-260.

Atkinson, Paul & Delamont, Sara (2006). Editors' introduction: Narratives, lives, performances. In Paul Atkinson & Sara Delamont (Eds.), Narrative methods (Vol.I, pp.xix-liii). London: Sage.

Balán, Jorge; Browning, Harley L.; Jelin, Elizabeth & Litzler, Lee (1974 [1968]). El uso de historias vitales en encuestas y sus análisis mediante computadoras. In Jorge Balán, Robert Angell.Howard S. Becker, Juan F. Marsal, Harley L. Browning, Elizabeth Jelin, Lee Litzler, James W. Wilkie, L.L. Langness & June Nash (Eds.), Las historias de vida en ciencias sociales. Teoría y técnica (pp.67-85). Buenos Aires: Nueva Visión.

Bartelheimer, Peter; Moncel, Nathalie; Verd, Joan Miquel & Vero, Josiane (2009). Towards analysing individual working lives in a resources/capabilities perspective. NET.Doc, 50, 21-50, http://www.cereq.fr/index.php/publications/Sen-sitising-life-course-research-Exploring-Amartya-Sen-s-capability-concept-in-comparative-research-on-individual-working-lives [Date of access: September 3, 2010].

Bertaux, Daniel (1997). Les récits de vie. Paris: Nathan.

Bonvin, Jean-Michel (2008). Capacités et démocratie. In Jean de Munck & Bénédicte Zimmermann (Eds.), La liberté au prisme des capacités (pp.237-261). Paris: Éditions de l'École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales.

Bonvin, Jean-Michel & Farvaque, Nicolas (2005). What informational basis for assessing job-seekers?: Capabilities vs. preferences. Review of Social Economy, 63(2), 269-289.

Burchardt, Tania & Vizard, Polly (2007). Definition of equality and framework for measurement: Final recommendations of the Equalities review steering group on measurement. CASE Paper 120, Centre for Analysis of Social Exclusion, London School of Economics.

Bynner, John (2005). Rethinking the youth phase of the life-course: The case for emerging adulthood? Journal of Youth Studies, 8(4), 367-384.

Bynner, John & Chisholm, Lynne (1998). Comparative youth transition research: Methods, meanings, and research relations. European Sociological Review, 14(2), 131-150.

Cohler, Bertram J. & Hostetler, Andrew (2004). Linking life course and life story. Social change and the narrative study of lives over time. In Jeylan T. Mortimer & Michael J. Shanahan (Eds.), Handbook of the life course (pp.555-576). New York: Springer.

Creswell, John W. (2003). Research design. Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Creswell, John W. & Plano-Clark, Vicki L. (2007). Designing and conducting mixed methods research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Clandinin, Jean D. & Connelly, Michael F. (1994). Personal experience methods. In Norman K. Denzin & Yvonna S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (pp.413-427). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Denzin, Norman K. (1989). Interpretive biography. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Diewald, Martin & Mayer, Karl Ulrich (2008). The sociology of the life course and life span psychology. DIW Discussion paper 772, Berlin.

DYNAMO (2007). Dynamics of national employment models. Essen: Institute for Work, Skills and Training at the University of Duisburg-Essen (Institut Arbeit und Qualifikation – IAQ).

Elder, Glen H. (1985). Perspectives on the life course. In Glen H. Elder (Ed.), Life course dynamics: Trajectories and transitions 1968-1980 (pp.23-49). Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Elder, Glen H. (1999 [1974]). Children of the Great Depression: Social change in life experience (25th anniversary ed.). Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Elder, Glen H.; Johnson, Monica Kirkpatrick & Crosnoe, Robert (2004). The emergence and development of the life course theory. In Jeylan T. Mortimer & Michael J. Shanahan (Eds.), Handbook of the life course (pp.3-19). New York: Springer.

Elliott, Jane (2005). Using narrative in social research. Qualitative and quantitative approaches. London: Sage.

Farvaque, Nicolas (2008). "Faire surgir des faits utilisables". Comment opérationnaliser l'approche par les capacités?. In Jean de Munck & Bénédicte Zimmermann (Eds.), La liberté au prisme des capacités (pp.51-81). París: Éditions de l'École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales.

Flick, Uwe (2009). An introduction to qualitative research (4th ed.). London: Sage.

Freedman, Deborah; Thornton, Arland; Camburn, Donald; Alwin, Duane & Young-DeMarco, Linda (1988). The life history calendar: A technique for collecting retrospective data. Sociological Methodology, 18, 37-68.

García Blanco, José María & Gutiérrez, Rodolfo (1996). Inserción laboral y desigualdad en el mercado de trabajo: Cuestiones teóricas. Revista española de investigaciones sociológicas, 75, 269-293.

Gasper, Des (2007). What is the capability approach? Its core, rationale, partners and dangers. The Journal of Socio-Economics, 36, 335-359.

Giarraca, Norma & Bidaseca, Karina (2004). Ensamblando las voces: Los actores en el texto sociológico. In Ana Lía Kornblit (Ed.), Metodologías cualitativas en ciencias sociales. Modelos y procedimientos de análisis (pp.35-46). Buenos Aires: Biblos.

Giele, Janet Z. & Elder, Glen H. (1998a). The life course mode of inquiry. In Janet Z. Giele & Glen H. Elder (Eds.), Methods of life course research. Qualitative and quantitative approaches (pp.1-4). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Giele, Janet Z. & Elder, Glen H. (1998b). Life course research. Development of a field. In Janet Z. Giele & Glen H. Elder (Eds.), Methods of life course research. Qualitative and quantitative approaches (pp.5-27). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Harré, Rom & de Waele, Jean-Pierre (1979). Autobiography as a psychological method. In Gerald Phillip Ginsburg (Ed.), Emerging strategies in social psychological research (pp.177-209). New York: Wiley.

Heinz, Walter R. (2003). Combining methods in life-course research: A mixed blessing?. In Walter R. Heinz & Victor W. Marshall (Eds.), Social dynamics of the life course. Transitions, institutions and interrelations (pp.73-90). New York: Aldine de Gruyter.

Heinz, Walter R. (2004). From work trajectories to negotiated careers: The contingent work life course. In Jeylan T. Mortimer & Michael J. Shanahan (Eds.), Handbook of the life course (pp.185-204). New York: Springer.

Jessop, Bob (2002). The future of the capitalist state. London: Polity.

Jovchelovitch, Sandra & Bauer, Martin W. (2000). Narrative interviewing. In Martin W. Bauer & George Gaskell (Eds.), Qualitative researching with text, image and sound (pp.55-74). London: Sage.

Klammer, Ute (2004). Flexicurity in a life-course perspective. Transfer, 2(4), 282-299.

Klammer, Ute (2009). The life course research perspective on individual working lives: Findings from the European Foundation research. NET.Doc, 50, 51-69, http://www.cereq.fr/index.php/publications/Sen-sitising-life-course-research-Exploring-Amartya-Sen-s-capability-concept-in-comparative-research-on-individual-working-lives [Date of access: September 3, 2010].

Klammer, Ute; Muffels, Ruud & Wilthagen, Ton (2008). Flexibility and security over the life course: Key findings and policy messages. Dublin: European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions.

Krüger, Helga (2003). The life-course regime: Ambiguities between interrelatedness and individualization. In Walter R. Heinz & Victor W. Marshall (Eds.), Social dynamics of the life course. Transitions, institutions and interrelations (pp.33-56). New York: Aldine de Gruyter.

Lahire, Bernard (2002). Portraits sociologiques. Dispositions et variations individuelles. Paris: Nathan.

Lewis, Jane (2001). The decline of the male breadwinner model: Implications for work and care. Social Politics, 8, 52-70.

Lieblich, Amia; Tuval-Mashiach, Rivka & Zilber, Tamar (1998). Narrative research. Reading, analysis and interpretation. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Masjuan, Josep Maria; Troiano, Helena; Vivas, Josep & Zaldívar, Miquel (1996). La inserció professional dels nous titulats universitaris. Bellaterra: ICE de la Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona.

Mason, Jennifer (2006). Mixing methods in a qualitatively driven way. Qualitative Research, 6(1), 9-25.

Mayer, Karl Ulrich (2005). Life courses and life chances in a comparative perspective. In Stefan Svallfors (Ed.), Analyzing inequality. Life chances and social mobility in comparative perspective (pp.17-55). Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Munck, Gerardo L. (2004). Tools for qualitative research. In Henry E. Brady & David Collier (Eds.), Rethinking social inquiry. Diverse tools, shared standards (pp.105-121). Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield.

Miles, Matthew B. & Huberman, A. Michael (1994). Qualitative data analysis. An expanded sourcebook (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Pallas, Aaron M. (2004). Educational transitions, trajectories, and pathways. In Jeylan T. Mortimer & Michael J. Shanahan (Eds.), Handbook of the life course (pp.165-184). New York: Springer.

Planas, Jordi; Casal, Joaquim; Brullet, Cristina & Masjuan, Josep Maria (1995). La inserción social y profesional de las mujeres y los hombres de 31 años. Bellaterra: ICE de la Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona.

Pujadas, Juan José (1992). El método biográfico: El uso de las historias de vida en ciencias sociales. Madrid: CIS.

Reimer, Maike & Matthes, Britta (2007). Collecting event histories with true tales: Techniques to improve autobiographical recall problems in standardized Interviews. Quality and Quantity, 47, 711-735.

Riessman, Catherine Kohler (1993) Narrative analysis. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Robeyns, Ingrid (2003). Sen's capability approach and gender inequality: Selecting relevant capabilities. Feminist Economics, 9(2-3), 61-92.

Robeyns, Ingrid (2005). Selecting capabilities for quality of life measurement. Social Indicators Research, 74, 191-215.

Rosenthal, Gabriele (2004). Biographical research. In Clive Seale, Giampetro Gobo, Jaber F. Gubrium & David Silverman (Eds.), Qualitative research practice (pp.48-64). London: Sage.

Rubery, Jill (2004). The dynamics of national social economic models and the lifecycle. DYNAMO Project Meeting, 15-16/10/2004, DYNAMO-Dynamics of National Employment Models, http://www.iaq.uni-due.de/aktuell/veroeff/2004/dynamo01.pdf [Date of access: February 24, 2009].

Runyan, William McKinley (1984). Life histories and psychobiography. Explorations in theory and method. New York: Oxford University Press.

Sampson, Robert J. & Laub, John H. (1993). Crime in the making. Pathways and turning points through life. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Sarabia, Bernabé (1985). Historias de vida. Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas, 29, 165-186.

Schmid, Günther (1998). Transitional labour markets: A new european strategy. Discussion paper FS I 98-206, Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung.

Schmid, Günter (2006). Social risk management through transitional labour markets. Socio-Economic Review, 4, 1-33.

Schwartz, Howard & Jacobs, Jerry (1984 [1979]). Sociología cualitativa. México: Trillas.

Sen, Amartya (1987). The standard of living: Lecture II. Lives and capabilities. In Amartya K. Sen (Ed.), The standard of living: The Tanner lectures on human values (pp.20-38). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Sen, Amartya (1992). Inequality reexamined. New York: Oxford University Press.

Sen, Amartya (1993). Capability and well-being. In Amartya K. Sen & Martha Nussbaum (Eds.), The quality of life (pp.30-67). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Sen, Amartya (1999). Commodities and capabilities. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Sen, Amartya (2002a). Introduction: Rationality and freedom. In Amartya Sen (Ed.), Rationality and freedom (pp.3-64). Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press.

Sen, Amartya (2002b [1983]). Liberty and social choice. In Amartya Sen (Ed.), Rationality and freedom (pp.381-407). Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press.

Sen, Amartya (2006). What do we want from a theory of justice? The Journal of philosophy, 103(5), 215-238.

Singer, Burton & Ryff, Carol D. (2001). Person-centered methods for understanding aging. In Robert H. Binstock & Linda K. George (Eds.), Handbook of aging and the social sciences (pp.44-65). New York: Academic Press.

Singer, Burton; Ryff, Carol D.; Carr, Deborah & Magee, William J. (1998). Linking life histories and mental health: A person centered strategy. Sociological Methodology, 28, 1-51.

Teddlie, Charles & Tashakkori, Abbas (2003). Major issues and controversies in the use of mixed methods in the social and behavioral sciences. In Abbas Tashakkori & Charles Teddlie (Eds.), Handbook of mixed methods in social and behavioral research (pp.3-50). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Thompson, Paul (2004). Researching family and social mobility with two eyes: some experiences of the interaction between qualitative and quantitative data. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 7(3), 237-257.

Verd, Joan Miquel; Vero, Josiane & López, Martí (2009). Trayectorias laborales y enfoques de las capacidades. Elementos para una evaluación longitudinal de las políticas de protección social. Sociología del Trabajo, 67, 127-150.

Vielle, Pascale & Walthery, Pierre (2003). Flexibility and social protection: Reconciling flexible employment patterns over the active life cycle with security for individuals. Dublin: European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions.

Wengraf, Tom (2001). Qualitative research interviewing. Biographic narrative and semi-structured methods. London: Sage.

Zimmermann, Bénédicte (2006). Pragmatism and the capability approach. Challenges in social theory and empirical research. European Journal of Social Theory, 9(4), 467-484.

Joan Miquel VERD is associate professor and researcher at the Department of Sociology of the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona (UAB). He is member of the Centre d'Estudis Sociològics sobre la Vida Quotidiana i el Treball (QUIT) and the Institut d'Estudis del Treball (IET). His research interests include sociology of labor, social network analysis, narrative and life-course analysis, and qualitative text analysis in general.

Contact:

Joan Miquel Verd

Department of Sociology

Centre d'Estudis Sociològics sobre la Vida Quotidiana i el Treball (QUIT-UAB)

Facultat de Ciències Polítiques i Sociologia

Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona

Campus UAB- Edifici B

08193 Cerdanyola del Vallès (Barcelona)

Spain

Tel.: 00 34 935812404

Fax.: 00 34 935812405

E-mail: joanmiquel.verd@uab.cat

Martí LÓPEZ ANDREU is presently finishing his PhD on work trajectories and changes in workers' resources, using biographical interviews. He is an assistant lecturer of Sociology of Labour and researcher at the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona (UAB). His research focuses on changes in employment and social protection and their effects on individual working lives.

Contact:

Martí López Andreu

Department of Sociology

Facultat de Ciències Polítiques i Sociologia

Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona

Campus UAB- Edifici B

08193 Cerdanyola del Vallès (Barcelona)

Spain

Tel.: 00 34 935814457

Fax.: 00 34 935814457

E-mail: marti.lopez@uab.cat

Verd, Joan Miquel & López, Martí (2011). The Rewards of a Qualitative Approach to Life-Course Research. The Example of the

Effects of Social Protection Policies on Career Paths [61 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 12(3), Art. 15,

http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs1103152.