Volume 12, No. 3, Art. 14 – September 2011

The Convergence of Historical Facts and Literary Fiction: Jorge SEMPRÚN's Autofiction on the Holocaust

Rosa-Auria Munté

Abstract: There are many testimonies preserved in archives that recount the horror of the Holocaust and that have become resources for historical and social research. In addition to testimonies produced with descriptive intention or in the full awareness of becoming documents for historians, some testimony writers have signed their books with a literary intention, but the very nucleus of their work is to explain the nature of their experience in the concentration camps without resorting to describing their own cases. These works blur the boundaries between history and literature, because, while they present themselves as works of fiction, they feed on testimonial autobiography. The testimony writers want to explain the horror that they experienced by fictionalizing their own experience. These are works which contain truth and which are narrated with a literary intention, works which reach a general audience and have a profound impact. This is the case of the Spanish writer Jorge SEMPRÚN, who attempts to "invent" the truth in his literary work. His autobiographic-novelistic testimony is situated in the ambiguous no-man's-land of autofiction.

Key words: autofiction; life-history; Holocaust; collective memory; Jorge Semprún

Table of Contents

1. Autobiography and Autofiction: Testimonies and Questions of Truth

2. Jorge SEMPRÚN's Autofiction

In memory of Jorge SEMPRÚN

(Madrid, December 10, 1923 –

Paris, June 7, 2011)

1. Autobiography and Autofiction: Testimonies and Questions of Truth

The representation of the Holocaust has always been a problematic issue. After the liberation of the Nazi concentration camps, the survivors realized the intrinsic difficulties that the narration of their experience would involve:

"As of those days, however, we saw that it was impossible to bridge the gap we discovered opening up between the words at our disposal and that experience which, in the case of most of us, was still going forward within our bodies. How were we to resign ourselves to not trying to explain how we had got to the state we were in? For we were yet in that state. And even so it was impossible. No sooner would we begin to tell our story than we would be choking over it. And then, even to us, what we had to tell would start to seem unimaginable" (ANTELME, 1998 [1947], p.3). [1]

The discovery of the horror of the Nazi extermination passed virtually unremarked in the post-war years and only had a significant impact on exiled Jewish intellectuals. Theodor ADORNO (1967 [1955]) postulated the impossibility of representing the horror of the Nazi genocide; Hannah ARENDT (1963) spoke of the banality of evil in a detailed study of the bureaucrat Adolf EICHMANN in the trial in Jerusalem; George STEINER (1967) criticized the literature of the immediate post-war period for not knowing how to approach the cataclysm that had just occurred with the necessary intensity; and Elie WIESEL (1977), among others, specifically stated that literary imagination could not be used to deal with the Holocaust, particularly by those who had not experienced it. [2]

These ideas about the representation of the Holocaust notably marked its representation, above all in the era in which it was infrequently represented, given that no term had as yet even been defined to differentiate the genocide of the European Jews from the rest of the horrors of the Second World War. Little by little, representation of the Holocaust has begun to emerge. In subsequent years, new representations of the Holocaust were accepted, although the concept of the limits of representation of the Holocaust was applied (FRIEDLANDER, 1992), until the end of the 1990s when we can finally speak of the globalization of the Holocaust (HUYSSEN, 2002). [3]

Today, more than sixty years after the liberation of the camps, the silence has been overcome and the Holocaust has been globalized as a potent image of evil. But in spite of the abundance of publications, the problem of how to represent the Holocaust has been present since the very beginning. This is because the Holocaust was a limit event: the sort of event that "before it happened, was not—perhaps could not have been—anticipated or imagined, and one does not quite know what is verisimilar or plausible in its context" (LaCAPRA, 2004, p.133). The fact that it had been so unforeseeable meant that it was particularly resistant to the attempts to represent it. [4]

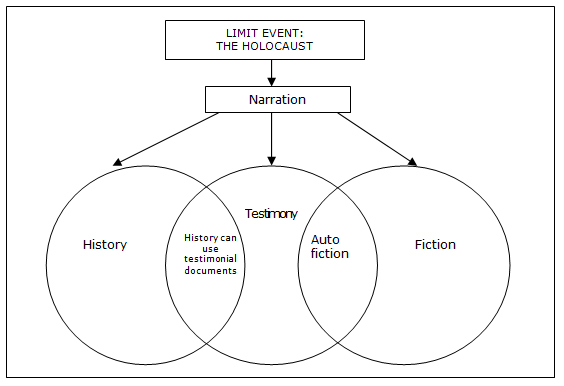

The historian Dominick LaCAPRA establishes a useful triple distinction of different ways in which an event as traumatic as the Holocaust can be represented. The three approaches he defines are testimony, fiction, and history. They may share certain features, for instance on the level of narrative, but they also differ, notably with respect to claims to truth and the way that an account is framed.

"Testimony makes claims of truth about experience or at least one's memory of it and, more tenuously, about events (although obviously one hopes that someone who claims to be a survivor did experience the events in reality). Still, the most difficult and moving moments of testimony involve not claims of truth but experiential 'evidence'—the apparent reliving of the past, as a witness, means going back to an unbearable scene, being overwhelmed by emotion and for a time unable to speak.

History makes claims of truth about events, their interpretation or explanation, and more tenuously, about experience. [...] Fiction, if it makes historical truth claims at all, does so in a more indirect but still possibly informative, thought-provoking, at times disconcerting manner with respect to the understanding or 'reading' of events, experience, and memory" (p.131). [5]

History can use testimonial documents like oral reports, diaries and memoirs, but all of these are clearly different from testimony. Fiction also explores the traumatic experience and the emotional dimensions of that experience: it talks about its emptiness or its fragmentation. [6]

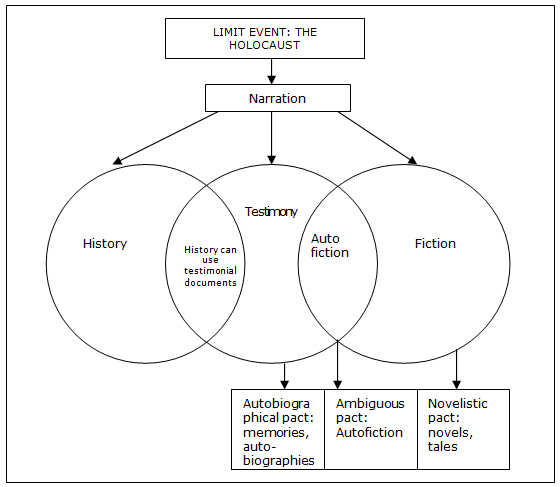

LaCAPRA's generic typology provides us with a clear distinction of different types of Holocaust texts. There are many examples of each text type and they differ widely in relation to who writes them, ranging from the obvious emotive proximity of testimony to the "objective" distance necessary for historical discourse. My objective is not to make a complete analysis of these three types, but to use this typology to discuss a genre where testimony and fiction meet. This genre is autofiction: the domain of the author-eyewitness who, instead of recording his memories, decides to fictionalize his experience in the Nazi camps.

Figure 1: The three approaches to narrate limit events (based on Dominick LaCAPRA's [2004] typology) [7]

The intention of this article is to contribute to an approach to life-history research using autofictional literary texts. Some studies highlight the position of literary criticism in ethnographical experience and in sociological studies (CLIFFORD & MARCUS, 1986). Autofictional texts are vindicated by literature but give a social response to a specific event, which happened at a particular time and from an individual point of view. In this case, Jorge SEMPRÚN speaks to us of the collective of political deportees (Spanish and French) in the Nazi concentration camp of Buchenwald through the eyes of a young deportee. [8]

Many survivors have written about the camps, but few of them have done so from the position of the author of fiction, that is, from the position of a witness who does not want to sign an autobiography but chooses autofiction, a fictional narration of his own biographical experience. But before exploring this ambiguous concept in more detail, let us recap what I have said so far. [9]

The origin of autofiction is related to autobiographical theory. In 1975, Philippe LEJEUNE wrote "Le pacte autobiographique," an encyclopedic work about autobiographical literature. LEJEUNE defines autobiography as a "retrospective prose narrative written by a real person concerning his own existence, where the focus is his individual life, in particular the story of his personality" (p.14). LEJEUNE (2005) subsequently revised his definition of autobiography although this same text also establishes two sine qua non requirements for a text to be considered an autobiography: the name of the author, the narrator, and the main character must be the same and must be verifiable; and the author must sign the work, either with his real name or with a pseudonym. Moreover, in the autobiographical pact, the author constructs his work on the premise of being honest about his own life. The reader must also perceive in the paratext certain truthful elements related to the author's identity. [10]

Identity is essential to the definition of biographical text, whereas the truth is not. Writing about one's own life admits the existence of a gulf between the lived life and the written life. While we are living our lives we do not write about them; when we do write about them, we remember and select what we will tell. This is why, at the very moment when someone writes about their past, they are reconstructing it by means of their memory; even if they mean to be entirely honest, they will not always explain exactly how things happened. Autobiography consists of writing a work about one's own existence, and it is the reader who accepts the facts narrated as real. [11]

Philippe LEJEUNE created a table to define autobiography in relation to reading pacts and the type of character (depending on the name they are given).

|

|

|

NAME OF THE CHARACTER |

||

|

|

|

Different from the author's name |

= 0 (undetermined) |

= Author's name |

|

P |

|

|

|

|

|

A |

Novelistic |

NOVEL |

NOVEL |

|

|

C |

= 0 (undetermined) |

NOVEL |

Undetermined |

AUTOBIOGRAPHY |

|

T |

Autobiographical |

|

AUTOBIOGRAPHY |

AUTOBIOGRAPHY |

Table 1: Table to define autobiography in relation to reading pacts and the type of character (Philippe LEJEUNE, 1975, p.28) [12]

In this table, autobiography occurs in three cases: 1. when, in the autobiographical pact, the name of the author and the name of the character are the same; 2. when, in this same pact, the name of the character does not appear in the text; and 3. when there is no autobiographical pact, but the name of the author and the name of the character are the same. So, LEJEUNE's table defines autobiography, but also leaves two boxes empty because he cannot find examples to illustrate this ambiguity: "Can the hero of a novel which claims to be such have the same name as the author? There is nothing to prevent it happening [...] but in practice, no example of such a thing springs to mind" (p.70). [13]

The empty boxes in LEJEUNE's table caught Serge DOUBROVSKY's eye. DOUBROVSKY used them to create his (auto)novel "Fils" (1977) and, at the same time, he creates the new—and successful—concept of autofiction. [14]

The origin of this concept, as we have explained, is found in LEJEUNE's table. He defines the empty box, the one that DOUBROVSKY will later call autofiction, as a text in which the author, the narrator, and the main character have the same identity. The title of the work is closer to the title of a novel than an autobiographical title. According to PANTKOWSKA (1998, p.14), DOUBROVSKY defines autofiction in these terms:

"Autofiction is the fiction that I as a writer have decided to present of myself, incorporating, in the full sense of the term, the experience of the analysis, not only in the subject matter but in the production of the text. (...) The identity of the author, the narrator and the character are true, but inside a fictional illusion conjured up and provoked by the act of writing. Autofiction, then, is a particular case not of traditional or modernist autobiography, but of the inscription of the biographical inside the text." [15]

In autofiction the author is omnipresent: either under a real name, a pseudonym or a homonym. The characters are real, though they appear in disguise. Finally, autofictional texts are always dominated by the novelistic pact rather than the autobiographical pact: that is, they are more like a novel than an autobiography. This is a crucial element to distinguish autofiction from novelistic autobiography, and it must be evident.

Figure 2: The three types of literary pacts in relation with Dominick LaCAPRA's (2004) typology to narrate limit events [16]

Autofiction exists in a no man's land between "fiction" and "truth," a land between novel and autobiography. ALBERCA shows that one of the most important obstacles to accepting autofiction is that it challenges some of the most widely-held ideas about literature:

"There is almost unanimous agreement that an important part of literary creation sinks its roots in the biographical world, in the experience lived, imagined or dreamed by the author, who normally tries to hide it, to camouflage it or recreate it in an artistic way. Now, autofiction has logic of its own, with other mechanisms, and uses autobiographical experience consciously, explicitly and sometimes deceptively" (1996, p.11). [17]

Fiction feeds on authors' biographies, whereas autofiction creates a hodgepodge of the author's past and his/her imagination. The author searches for confusion, contradiction, insinuation: at the same time, he or she is, and is not, the main character. But, despite the reader's curiosity, it is not important to delimit the autobiographical truth. In the case of autofictional texts by Nazi camp survivors, as we will see with Jorge SEMPRÚN, autobiographical truth does not question the constitutive truth of the autofictional text. [18]

In classic autobiography the subject rummages through his or her past, and writes the story of his or her life, ideas, and experiences, using his "inner look." In autofiction, on the other hand, fictionalization is the only way to understand the existential truth of the subject. The evidence of the erosion of memory has been the object of the reflections of several Holocaust survivors and writers. Autofiction can provide an answer to the complex question "how can one write a truthful text about oneself?" It is a kind of text in which the writer decides to give an explanation both to himself or herself and to others (since he or she decides to publish it), adding a fictional elaboration. [19]

2. Jorge SEMPRÚN's Autofiction

Jorge SEMPRÚN, who died on June 7th 2011, in Paris, was a writer and screenwriter, an anti-Francoist political activist and Minister of Culture of the Spanish government (1988-1991), as well as an honest intellectual who lived through totalitarian Nazism and spoke out against the abuses of Stalinism as a member of the Communist Party. He was a significant intellectual in Spain and France, his country of origin and his host country respectively. Jorge SEMPRÚN exemplifies the ambiguous contract of autofiction. He uses a multiplicity of first persons, and what he writes is between autobiography and novel. Most of his writings are about his past, about Buchenwald and his fight against the FRANCO regime. He considers his survival in Nazi camps as the basic constitutive element of his identity: first and foremost, he is "a deportee to Buchenwald." For this reason, we will analyze four of his books on the theme: "El largo viaje" ["Le grand voyage"] (1994 [1963]), "Aquel domingo" ["Quel beau dimanche!"] (2004 [1980]), "La escritura o la vida" ["L'écriture ou la vie"] (2001a [1994]), "Viviré con su nombre, morirá con el mío" ["Le mort qu'il faut" (2001b [2001]) . But his identity as a writer was also important. Like other testimony writers (for example, Primo LEVI and Ruth KLÜGER), literature gives SEMPRÚN company in the concentration camp, especially in the most critical moments. When his beloved friend Diego MORALES is dying, SEMPRÚN recites César VALLEJO's poem "España, aparta de mí este cáliz" ("Spain, Take this Cup away from Me") (written in 1937 and published in 1939) and when it is the turn of Maurice HALBWACHS, SEMPRÚN recites verses from BAUDELAIRE. Poetry recited from memory gives comfort to the dying and, in a way, to SEMPRÚN as well. He brings literature into the camp and believes that its positive effects will also be healing in the future. In "La escritura o la vida" (2001a [1994]) his most important work, he explains the dichotomy he encountered after his liberation. In the early days of his freedom the young SEMPRÚN believed that writing would be a good way to reintegrate himself into life, but he soon realized that in fact it was dragging him towards death.

"I have nothing but my death, my experience of death, to enable me to tell the story of my life, to express it, and to continue living it. I must fabricate life with so much death. And the best way to achieve this is through writing. That is what I am doing. I can only live by accepting this death through writing, but writing literally forbids me to live" (p.180). [20]

Memories of the camps brought anguish, emptiness, and death rather than life. SEMPRÚN explains how, in draft after draft, he tried to describe his experience in the death camp, but he always started to talk from outside the camp, because inside (the camp), writing had been blocked. The tremendous difficulty that writing entailed even brought him to attempt suicide:

"In fact I had fallen off a train.

It was a miserable local train, in fact: there was nothing significant or heroic about it. But had I actually fallen off that ordinary train, packed with people, or had I deliberately thrown myself off? There were divergent opinions about this; not even I really knew for sure. A young woman, after the accident, said that I had thrown myself out of the open door" (p.226). [21]

Other testimony writers did commit suicide: among them Primo LEVI, Paul CELAN, Tadeusz BOROWSKI, Jean AMÉRY, and Bruno BETTELHEIM. SEMPRÚN fell into silence. Only by leaving his memories to rest could he recover his will to live; in fact, he was silent for so many years that some of his closest friends knew nothing about his past. One day he started to talk and to write about his experience:

"Then, without having taken a decision, so to say—if there was a decision on my part, it was to remain silent—I began to speak. Perhaps because no one asked anything of me, because no one asked me any questions, because I was answerable to no one. [...] Perhaps because the people who return must speak in place of the ones who do not [...] Sometimes, we probably have to speak in the name of those who did not survive. To speak in their name, in their silence, to restore to them the ability to speak" (SEMPRÚN, 2001a [1994], p.154). [22]

During those years of silence, SEMPRÚN talked to other survivors of the camps. He saw that they were unable to communicate their experiences properly (for instance, Fernand BARIZON or Manuel AZAUSTRE, who hid SEMPRÚN in an apartment in Madrid, when he was working underground for the Communist party). BARIZON and AZAUSTRE described their experiences as an accumulation of horrors, like a "Shakespearean delirium"; SEMPRÚN realized that someone can live through a personal limit-experience, but may not be capable of reconstructing it in order to give it sense, to transform it into something communicable.

"Has anyone really lived through something that is impossible to describe, the truth of which, even if it is minimal, cannot be meaningfully reconstructed in order to make it communicable? Is living not transforming a personal experience into consciousness? But can one assume any experience without more or less mastering its language? That is, history, stories, recollections, testimony: life? Text, the same texture, the fabric of life?" (2004 [1980], p.71) [23]

But even while in Buchenwald, SEMPRÚN realized the necessity of fiction, of recreation through literary artifice, as the only way to transmit the essence of experience:

"—I imagine there will be an abundance of testimonies ... Their value will be the value of the acuteness, the perspicacity of the witness ... and then there will be documents... Later, historians will collect them, compile them and analyze them, and will write learned works... Everything will be said, everything will appear there ... And it will all be true ... But the real truth will be missing, the truth that no historical reconstruction, however accurate and all-embracing, can achieve...

The others look at him, nodding, apparently relieved to see one of us able to formulate the problems so clearly.

—Another kind of understanding, the essential truth of experience, is not transmissible ... Or rather, it is only transmissible through literary writing.

He turns towards me, smiling.

—Through the artifice of the work of art, of course!" (SEMPRÚN, 2001a [1994], p.140) [24]

Like Jorge SEMPRÚN, Imre KERTÉSZ considers that literature and imagination played an essential role—an ethical role—in understanding the horrors of totalitarianism in the twentieth century. KERTÉSZ's point of view is clear and he expresses it with a grave contradiction: "only with the help of an aesthetic imagination are we able to create a real imagination of the Holocaust" (2001, p.66). But what we imagine is not only the Holocaust, it is also "the ethical consequence of the Holocaust reflected in the universal conscience" (p.66). [25]

It is at this point that SEMPRÚN talks about the most enduring memory for him. He asks: "What do you do with the memory of the smell of burned flesh? It is precisely for such circumstances that literature exists" (ESPADA, 2000, p.12). Only literature and its imagination can come close to the focus of the horror. But fiction consists not only in inventing, but in selecting, "in cutting, framing, and choosing from among the magma" (MUNTÉ, 2004, p.130). SEMPRÚN distinguishes between truth and fiction. This means that his books about Nazi camps are absolutely truthful, even though he uses fiction to accommodate reality to narration. In reference to his book "El largo viaje" (1994 [1963]) he states that everything is true, even what he had invented. Therefore, his concept of the truth resides in the absolute authenticity of the story, even though it did not happen exactly as it is told. He says, above all, that there is a moral limit in inventio: he has never fictionalized anything to exaggerate real events. And this is an essential point, because negationists have gone to great lengths to find contradictions in the works of testimony writers or any indication of fabrications that would enable them to discredit the entire text. [26]

A literary limit also exists, required by narrativity. In "El largo viaje" he relates an experience that was universal among the survivors of the Holocaust: the long trip in the infamous cattle truck in which he was deported to Buchenwald. The invented figure of the boy from Semur in "El largo viaje" permits the reader to identify with him and also helps the reader to understand the reality. In the book "Viviré con su nombre, morirá con el mío" (2001b), SEMPRÚN explains a real event from his past in Buchenwald, but not in the way it actually occurred; because of the demands of the narrative, he condenses the action into three days (a weekend) although in fact the process took longer. The group of clandestine communists in the camp found out that the Nazis were looking for SEMPRÚN. Just in case, they decided that he had to go into the infirmary in order, if necessary, to exchange his identity with one of the dying and thus save his own life. There he found François, an acquaintance with a parallel life who perished by his side. [27]

In "El largo viaje" (1994 [1963]) he invented the boy from Semur: the main voice, the one which says the most and with whom he relives his deportation to Buchenwald. SEMPRÚN says in "El largo viaje": "I write this story, and I do what I want. I could not talk about the boy from Semur. He made that trip with me; in the end he died; it is a story that does not interest anyone. But I have decided to talk about it" (p.26). However, in "Viviré con su nombre, morirá con el mío" he states that the boy from Semur was an invention and that it was François, his alter ego in that novel, who suggested it:

"'If I survive', he had said to me in the latrine hut, 'if I get out of this alive, I swear that I'm going to write about all this.' 'For a while now', he added, 'it's been an idea, a project for writing which seems to give me strength. But if one day I write, in my account I won't be alone, I'll invent a travelling companion. Someone to talk to after so many weeks of silence and solitude.' [...] Fifteen years later, in Madrid, in a safe house, I followed his advice, and started to describe the long journey. I invented the boy from Semur to keep me company in the train wagon. In the fiction we made that journey together, to erase my solitude in real life" (SEMPRÚN, 2001b, p.179). [28]

This connection between writer and characters, invented figures or alter egos of the author creates a mosaic of identities that makes it difficult to tell who is who. It arouses readers' curiosity, but this is not really important. They are all him: he gives a voice to all those who died. On the same page, SEMPRÚN helps to clarify this multiplicity of first persons:

" 'If I get out of here and write, you'll be in my story,' he said. 'Will you agree to that?' 'But you don't know anything about me!' I answered. 'What use will I be to you in your story?' He said that he knew enough to make me into a fictional character. 'Because you'll become a fictional character, my friend, even if I don't invent anything. [...] Why write books if you don't invent truth? Or something that seems like the truth?' " (p.179) [29]

Everything that SEMPRÚN says about François is invention and truth at the same time. For SEMPRÚN, fiction has the function of inventing the truth, of presenting it in a comprehensible way, and of making sure that his texts do not become a magma of death and pain. Re-creation and reconstruction allow a dialogue with the reader's conscience. For Jorge SEMPRÚN, literary fiction entails ethical and aesthetic truth at the same time: aesthetic because literature allows him to transcend his own experience to talk about the ineffable, and ethical because the author was a direct witness of the Holocaust who establishes a testimonial pact and does justice to the collective memory of all those murdered in the Nazi camps. [30]

SEMPRÚN has a dual persona: he is a survivor and a writer, who believes that literary artifice is necessary for recreation. "Exact" historical truth is not the main purpose of his writing, although all his texts are underpinned by the truth of his life in Buchenwald. All his books have the experiential evidence of which LACAPRA speaks. The power of his books is the power of his signature: he was there, he saw it, he survived; and now he is describing it to us. But not as in a book of memoirs or an autobiography. Literature for SEMPRÚN inspires truth: who but the witness can write of the "stench of the crematorium"? Who but the testimony writer can begin his account of life in Buchenwald with the disconcerting narration of a peaceful Sunday in the camp? [31]

Autofiction became a viable option for some of the most important writer-survivors of the Holocaust, such as SEMPRÚN himself, the Nobel prize-winner Imre KERTÉSZ, and Tadeusz BOROWSKI, for whom literary artifice became the best way of explaining the horror of their experience. In fact, Jorge SEMPRÚN soon realized the necessity of recounting when he encountered Fernand BARIZON or Manuel AZAUSTRE and observed the difficulty they had to recount significantly. In this way, his testimony, his autofictional books, speak of an "I" who wants to give voice to a "we." It is the transmission of a collective: the political deportees at the Nazi camp of Buchenwald. His texts have a great expressive capacity to tell us the anguish and the terrible decisions that the deportees found themselves doomed to make, the contradictions of the concentration camp system, the clandestine organizations and, thus, they hold undoubted interest for life-history research. [32]

References

Adorno, Theodor (1967 [1955]). Prisms. London: Neville Spearman.

Alberca, Manuel (1996). El pacto ambiguo: ¿Es literario el género autobiográfico?. Boletín de la Unidad de Estudios Biográficos, 1, 9-18.

Antelme, Robert (1998 [1947]). The human race. Vermond: Marlboro Press.

Arendt, Hannah (1963). Eichmann in Jesualem: A report on the banality of evil. New York: Viking Press.

Clifford, James & Marcus, George (1986). Writing culture. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Doubrovsky, Serge (1977). Fils. Paris: Galilée.

Espada, Arcadi (2000). Jorge Semprún, escritor. ¿Qué haces con el olor a carne quemada?. El País, August 19, p.12.

Friedlander, Saul (Ed.) (1992). Probing the limits of representation, Nazism and the final solution. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Huyssen, Andreas (2002). En busca del futuro perdido. Cultura y memoria en tiempos de globalización. México: Fondo de cultura económica.

Kertész, Imre (2001). Un instante de silencio en el paredón. Barcelona: Herder

LaCapra, Dominick (2004). History in transit: Experience, identity, critical theory. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Lejeune, Philippe (1975). Le pacte autobiographique. Paris: Seuil.

Lejeune, Philippe (2005). Signes de vie, Le pacte autobiographique 2. Paris: Seuil.

Munté, Rosa-Àuria (2004). Una entrevista a Jorge Semprún. La narración de la vivencia de los campos de concentración en la literatura y el documental. Trípodos, 16, 127-38.

Pantkowska, Agnieszka (1998). Entre l'autobiographie et l'autofiction. Brussels: Université Adam Mickiewicz Poznán.

Semprún, Jorge (1994 [1963]). El largo viaje. Barcelona: Seix Barral.

Semprún, Jorge (2001a [1994]). La escritura o la vida. Barcelona: Tusquets.

Semprún, Jorge (2001b). Viviré con su nombre, morirá con el mío. Barcelona: Tusquets.

Semprún, Jorge (2004 [1980]). Aquel domingo. Barcelona: Tusquets.

Steiner, George (1967). Language and silence: Essays 1958-1966. London: Faber and Faber.

Vallejo, César (1986 [1939]). Poemas humanos; España, aparta de mí este cáliz. Madrid: Castalia.

Wiesel, Elie (1977). The holocaust as literary inspiration. Dimensions of the Holocaust. Evanston: Northwestern University Press.

Rosa-Àuria MUNTÉ RAMOS obtained a bachelor's degree in Humanities from Pompeu Fabra University, Barcelona. After obtaining a research scholarship, she also started working as a lecturer at the Blanquerna School of Communication of Ramon Llull University (Barcelona), where she finished her master's thesis on Holocaust narration. She is currently working on her PhD about literary fiction of the Holocaust. She is a member of the research group "Violence and Media" of the School of Communication of the University Ramon Llull. She has been member of a research group for the Spanish Ministry of Education about "Childhood, Violence and Television. TV Uses and Children's Perception of Violence in TV" She also has participated in the research "Couple Stereotypes Representation in TV Serial Fiction" for the Catalan Women's Institute (ICD) and Audiovisual Council of Catalonia (CAC). She has participated in the development of pedagogic materials for primary and secondary pupils about the mass media and how to use the media, in a public project for Barcelona City Council, and for a project for ONCE (the National Spanish Association for the Blind). She also has participated in an applied research project about video games and multimedia material financed by Abacus and Ethos Cathedra. Her interests include Holocaust narratives, violence in mass media and children's reception, and writing teaching materials.

Contact:

Rosa-Àuria Munté Ramos

Facultad de Comunicación Blanquerna

c/ Valldonzella 23

08001 Barcelona

Spain

Tel: +34 93 253 31 08

E-mail: rosaauriamr@blanquerna.url.edu

Munté, Rosa-Auria (2011). The Convergence of Historical Facts and Literary Fiction: Jorge SEMPRÚN's Autofiction on the Holocaust

[32 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 12(3), Art. 14,

http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs1103144.