Volume 13, No. 1, Art. 8 – January 2012

Survivor-Controlled Research: A New Foundation for Thinking About Psychiatry and Mental Health

Jasna Russo

Abstract: Survivor-controlled research in the field of mental health can be perceived as the most extended development of participatory research. This is not only because it does away with the role of research subjects, but because the experiential knowledge (as opposed to clinical) acquires a central role throughout the whole research process—from the design to the analysis and the interpretation of outcomes stages.

The first part of this article provides some background information about the context and development of user/survivor-controlled research in the UK. In the second part, the discussion focuses on the first two German studies which apply this research methodology in the field of psychiatry. Both studies are used as examples of the approach, which favors closeness to the subject as opposed to "scientific distance."

The overall objective of this paper is to outline the general achievements and challenges of survivor-controlled research. Arguing for the value of this research approach I hope to demonstrate the ways in which it raises fundamental issues related to conventional knowledge production and challenges the nature of what counts as psychiatric evidence.

Key words: survivor-controlled research; user-controlled research; service user involvement; experiential knowledge; researcher's identity

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. Background of Survivor-Controlled Research

2.1 Origins

2.2 Involvement vs. control: Who owns the research?

2.3 Values and underlying principles in survivor-controlled research

3. Survivor-Controlled Research in Germany

3.1 Taking a stand. Homelessness and psychiatry from survivor perspectives

3.2 Evaluation and practice project: Person-centered care from the users' perspectives

4. The Prospects for Survivor-Controlled Research

4.1 Barriers from the outside

4.2 Facing up to barriers from the inside. Taking on the challenge

Mainstream psychiatric and mental health research to date remains overwhelmingly dominated by the biomedical model. It also includes the efforts to emulate the natural sciences by conducting large-scale, cost-intensive, randomized controlled trials that treat human experiences as predictable and measurable reactions to be observed in isolation. Although never scientifically proven, the theory of madness and distress as matters of a "broken brain" (WEBB, 2010, p.94) continues to undergird modern psychiatric research. Another distinctive characteristic of this research, which applies to qualitative studies as well, is the unquestioned and "natural" division of research roles into those of research subjects, on the one hand, and the ostensibly objective, value-neutral researchers on the other. The researchers are usually clinical academics and studies are often conducted within the context of treatment. The decisive ways in which such research scenarios affect the outcomes of these studies, which then constitute the evidence in psychiatry, remain largely unaddressed (RUSSO & WALLCRAFT, 2011). [1]

Survivor-controlled research1) in mental health emerges as a radical critic of these two traditions—the biomedical model of madness and distress and the conventional understanding of research roles. So far, this research approach has been much more successful in developing viable alternatives to traditional research roles. There are good reasons for the failure of survivor-controlled research to date to disrupt the dominant biomedical model. However before entering that discussion, I will first briefly outline the historical context in which survivor-controlled research emerged as well as its core values and principles. This short background sketch is not intended to be comprehensive nor complete, and I strongly recommend consulting the referenced literature. The outline of the development of survivor-controlled research will be principally limited to the UK context because of the decisive achievements of British survivor research and its impact on the first German research projects of this kind. These German projects are the topic of the second part of this article. Finally, I will discuss the main challenges and barriers which survivor-controlled research faces and then contemplate its future. This paper aims at showing the potential of this research approach to acquire a crucial role in shifting the dominant perspectives in mental health and shaping radically different social responses to madness and distress. [2]

2. Background of Survivor-Controlled Research

Survivor research2) is rooted in the political movement of people who have been subjected to psychiatric treatment or identify themselves as current or former users of mental health services. The first collective protests of psychiatric patients are documented at the beginning of the 17th century (HORNSTEIN, 2008, p.23)), but UK survivor research really emerges from the movement of the 1980s (SWEENEY, 2009, p.29). Despite a number of common issues, the international service user/survivor movement divides into two main groups, which are mirrored by their distinct terminologies. "Service user" (Europe) or "consumer" (Australia, New Zealand and USA), on the one hand, and "survivor of psychiatry," on the other, are expressions of two different perspectives on psychiatry: the first one focuses on reforming the existing system, while the second puts the entire psychiatric system in question, including the very premise of mental illness. Summarizing the research among UK user/survivor organizations that she co-conducted, Angela SWEENEY (p.23) provides the following description of the movement: "[...] the user movement doesn't constitute a single voice that represents all users/survivors on all issues. This has led to the philosophy of the movement that prizes choice, self-determination and individual and collective empowerment." [3]

Survivor-controlled research shares the core principles of the user/survivor movement (p.23). Above all, it values first-person experience which it considers a true and legitimate source of evidence. The service user/survivor movement and survivor research both aim at restoring credibility and authority to those who have been historically deprived of it through psychiatric labeling. Contemporary survivor research challenges such continued deprivation in a particularly powerful way. The Australian survivor researcher David WEBB (2010, p.108) argues for the necessity of first-person knowledge:

"If we limit our inquiry to just third-person data and knowledge then we will only ever achieve at best a partial understanding of whatever we might be studying. [...] In the postmodern era of first-person, subjective dimensions of all knowledge must at all times be part of the research agenda." [4]

I concur with WEBB's abandonment of the knowledge attributes "subjective" and "objective," which he sees as heavily loaded in the research context. Instead, he distinguishes between "third-person knowledge for traditional, so called scientific knowledge and the first-person knowledge of phenomena that can only be known through subjective, lived experience of them" (p.102). [5]

Despite taking people as its central subject of interest, psychiatry is a discipline based on the exclusion of first-person knowledge. UK survivor researcher Jan WALLCRAFT (2009, p.133) describes the consequences of such tradition:

"Mental health service users have traditionally been excluded from creating the knowledge that is used to treat us, and many of us have suffered from the misunderstanding of our needs by people who have been taught to see us as by definition incapable of rational thought." [6]

Survivor research is a way for those of us who have insider knowledge of living through severe mental crises and receiving psychiatric treatment voluntarily or against our will—for those of us "who have been there" (STASTNY, 1992, n.p.) and back—to take part in knowledge production and to contribute to the creation of different responses to human crises. [7]

In her foreword to the book "This is Survivor Research," New Zealander Mary O'HAGAN (2009, p.i) observes how survivor research develops a new foundation, which "[i]s planting itself deep and cracking the bedrock of the most fundamental beliefs traditional mental health systems rest upon." [8]

O'HAGAN considers survivor research a challenge to the biomedical belief system—

"in a myriad of ways—by its very existence, its curiosity and respect for subjectivity, it reluctance to distance the researcher from the research, its critique of knowledge, power, value-free research and the standard hierarchy of evidence, and its empowering methodologies. All these challenges, implicitly or explicitly, rest on the revolutionary idea that madness is a full human experience" (p.i). [9]

I share the conviction that survivor research has the strong prospect of enduringly putting psychiatric premises into question. However, in practice, it faces severe constraints to developing its full potential. The most limiting obstacle is the improbability of survivor-controlled research to attract funding whereas the trend towards participation in mental health research known as "user involvement" is booming. [10]

2.2 Involvement vs. control: Who owns the research?

The main difference between service user involvement and survivor-controlled research lies in the role designated to experiential knowledge as opposed to clinical and academic knowledge. In survivor-controlled research, knowledge and values of those having direct, personal experiences with the topic under investigation guides the whole research process—from formulating the research questions to drawing conclusions. In distinction, what is known as service user involvement in research remains just an optional, add-on component, meant to extend the dominant perspectives (clinical and academic ones) with those of direct experience. [11]

There are different ways in which mental health service users can be involved in research and different degrees of involvement (SWEENEY & MORGAN, 2009, pp.32f.; BERESFORD; 2009, p.182; LINDOW, 2010, p.140). The common sense view that research participants are more likely to open up to people they feel closer to is entering psychiatric and mental health research as well, being the most frequent motivation for involving service users in research. In addition to becoming interviewers, data collectors and recruiters, service users can advise on the research process or take part in different kinds of collaborations with clinical academics. Some countries are more supportive of such research collaborations than others. For example, the UK government promotes public involvement in research, including the involvement of mental health service users (DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, 2001) and this requirement can also often be found among funding criteria. [12]

Service user involvement can also constitute added value in some EU-funded research programs. What at first sight seems to be an encouraging development, has proven to engender such adverse effects as tokenism, ad hoc partnerships just for the purpose of submitting an application, and various mechanisms by which the participation of those directly affected becomes just another box to tick. In their comprehensive investigation of user-controlled research, Michael TURNER and Peter BERESFORD (2005, p.vi) report: "User involvement in research tends to be compared unfavorably with user controlled research because the former is seen to embody inequalities of power which work to the disadvantage of service users." [13]

Some academics and clinicians practicing this approach also acknowledge the limitations of user involvement in research. Mark GODFREY (2004, p.224) writes: "[…] user involvement, in the main, tends to stop at the participation level, and it does not change the balance of power." [14]

Similarly, looking back at his collaborative experiences with service users the USA psychiatrist Peter STASTNY critically observes: "This newly found collaboration between the most and the least powerful players in the mental health system generated excitement, insights, new alliances, but little change in actual power structures" (RUSSO & STASTNY, 2009, p.62) [15]

Without entirely eliminating this research option as a whole I would like to stress that service user involvement in mental health research provides no guarantee that an equitable dialogue will take place and that the research outcomes will be co-produced in partnership: "There are several ways to involve users in research without really letting them in—either for their own good or in order to improve some of the research technicalities." (p.66) [16]

The UK experience with user involvement in research has now gone on for long enough to bear some reflection. Among the outcomes of some reviews is a growing distinction between the consumerist and democratic approaches to user involvement, and an acknowledgment that this trend has the potential to be not just liberating but also regressive (BERESFORD, 2002; SWEENEY, 2009, p.24). The recently published "Handbook of Service User Involvement in Mental Health Research" (WALLCRAFT, SCHRANK & AMERING, 2009) offers valuable accounts and reflections on the potential, achievements and contradictions of collaborative and participatory approaches in mental health research. In comparison to survivor-controlled research, service user involvement in research might sound like a more realistic and easier practice to grasp, but I believe that this research direction still has a long way to go if it is to become authentic and true to its self-description. [17]

This article focuses on those rare research projects in which the whole process, from design to dissemination, is fully owned by service users/survivors. The competition for funding and recognition may foster the expansion of the terms "service user" and "user control," because they seem less negative and less threatening than "survivor" and "survivor control." [18]

Although sometimes used interchangeably, the term "user-led" is at the weaker end of the spectrum with blurred borders. This absence of clearly defined terminology in survivor research mirrors the fluid character of an approach that is still taking shape and establishing itself somewhere near participatory and action research with the closest affinity to emancipatory disability research (BERESFORD & WALLCRAFT, 1997). It could also be that those who have personally experienced the consequences of psychiatric labeling have become extremely careful and reluctant when it comes to categorizing anything. In their inquiry into what constitutes user-controlled research, Michael TURNER and Peter BERESFORD (2005, p.5) aimed at "supporting further discussion and exploring variations" rather than proffering a single answer. They give the following explanation: "We thought it was important not to seek to create new orthodoxies in research. Service users are often on the unhelpful receiving end of such orthodoxies" (p.5). [19]

Survivor control is often described as the highest degree of survivor involvement in research (GODFREY, 2004, p.224; SWEENEY & MORGAN, 2009, pp.28-30; LINDOW, 2010, p.140). Survivor-controlled research refers to research projects in which all stages of the research (from its design to the production of final reports, including the management of funds) are in the hands of researchers who have direct experience of psychiatry or as users of mental health services. I fully agree with TURNER and BERESFORD (2005, p.16) that early engagement in the project is central to the concept of control and would import their citation of EVANS and FISHER (1999, p.103) in this context: "It is the difference between engaging in a self-generated activity and being invited, with whatever degree of humanity, to join an activity already underway." [20]

The answers to questions such as "Who is inviting whom to whose project? At what stage and with what kind of intention?" are the most likely to hold the key to understanding the differences between participation and control:

"Collaboration usually starts by academics inviting user researchers to contribute to their projects and not the other way around. [...] Users are invited at various stages of someone else's project. They are rarely invited to plan and seek funding for the research and to define the roles and responsibilities" (RUSSO & STASTNY, 2009, p.63) [21]

The clear words of representatives of the Wiltshire and Swindon Users' Network (WSUN) about their experience of being "made use of by academic researchers in order to collect our views for research which they would publish and gain credit and recognition for" (quoted in TURNER & BERESFORD, 2005, p.16) are an accurate description of the experiences of many service users/survivors in research. First-hand experience of participatory methodologies that attempted to involve us in an "empowering" way and for our own good inspired many of us to start our own research. [22]

In contrast with service user involvement in research which is likely to take place at universities4), survivor-controlled projects are usually conducted outside of academia and are also far less likely to be published in peer-reviewed journals. They are often hosted by user/survivor organizations or mental health NGOs and funded by charities or from lottery money. Their reports are usually not exclusively aimed at an academic audience, but instead use language accessible to a broader readership. [23]

The information that service users/survivors have full control and responsibility for the research process is certainly not enough to explain the nature of that process and its main features. Survivor-controlled research defines itself much more through its core values and principles than its allegiance to any particular methodology. [24]

2.3 Values and underlying principles in survivor-controlled research

Survivor research is more often likely to apply qualitative methods such as semi-structured interviews and focus groups, without eschewing a quantitative approach. A combination of both methods or the development of new ones is also common. But whatever the methods applied, the most distinctive characteristic of this approach is the key role of experiential knowledge. This is first expressed in the composition of the research team, and subsequently in the ways in which participants are enabled to shape the research outcomes. There are far more comprehensive accounts of the values and principles of survivor research than the brief snapshot that I can provide here. I strongly recommend Alison FAULKNER's "The Ethics of Survivor Research" (2004) and TURNER and BERESFORD's report "User Controlled Research: Its Meanings and Potential" (2005), which each extrapolate a list of key values and principles of survivor research. Further essential reading is the first book publication about this research approach edited and written by the UK leaders in the field—"This is Survivor Research" (SWEENEY, BERESFORD, FAULKNER, NETTLE & ROSE, 2009). For the purpose of this article, I will limit my consideration of this major subject to the issues of identity and understanding of the research process. [25]

2.3.1 Shared identity and closeness to the research topic

Like participatory research, survivor research aims to equalize power relationships in the research process, but it does so in quite a different way. Survivor-controlled research acknowledges the fact that we are all part of the social reality we are exploring and that who we are will always affect our interactions, including those in the research process. The identities of researchers, their knowledge, experiences and beliefs have an effect on all research, not just survivor-controlled projects. However survivor research is transparent about its researchers' standpoints and willing to work with them instead of pretending that these are neutralized as soon as academic degrees are conferred. Instead of espousing a notion of "scientific distance," it promotes closeness to the subject as beneficial to the quality of the research. This closeness to the subject in survivor-controlled research is not a tool produced for the sake of research as in some anthropologists' (ESTROFF, 1981) and psychologists' (HORNSTEIN, 2009) attempts to "go native" and thereby come closer to the service user/survivor community. Considering the ethics of playing an insider in order to collect data and perform the research, as well as the overall purpose and quality of such studies would go beyond the scope of this article. At this point I just want to draw a clear line between these approaches and survivor-controlled research which actually imparts an insider perspective to research. [26]

The openness about where we come from and what motivates our work also makes survivor-controlled research subject to accusations of being unscientific and biased. Our response in pointing out where many other researchers in the field of psychiatry come from and what motivates their work, and in reviewing the outcomes they report and identifying biomedical or pharmaceutical industry biases, can make us even less popular.

"User controlled research has been honest and transparent about its particular allegiance and political relations, while traditional research has tended to be framed more in neutral technicist terms, as 'neutral', 'scientific' and 'objective'. Service users, however, argue that it is also partial, in its priorities, focus and process" (TURNER & BERESFORD, 2005, p.72). [27]

In addition to their empirical research, Michael TURNER and Peter BERESFORD have also conducted a comprehensive literature review on user-controlled research. They have identified a remarkable gap between the criticism that is leveled at service user/survivor-researchers by mainstream research organizations on the one hand, and a telling absence of any negative statements about their research approach in the formal literature on the other.

"Service users made clear in the project that they felt there were negative often discriminatory responses to user controlled research. But these rarely surface in formal discussions and published literature. They are instead part of a hidden history of user controlled research, usually only finding expression in informal and unrecorded discussions among researchers or with service user researchers, or in the confidential and anonymized statements of peer reviewers, grant assessors and so on. Hopefully in the future it may be possible to get a more accurate and systematic picture of such opposition to user controlled research" (p.11). [28]

I will come back to the reception of survivor research by mainstream circles in the concluding part of this article. At this point, I would like to close this brief outline of the appreciation and transparency of the researcher's identity in survivor research—a position which inspires accusations of bias—by drawing on Peter FERNS's statement: "Good science will always be conducted within a social context which is clearly defined and understood" (2003, p.23). [29]

2.3.2 Joint analysis and interpretation

One of the participants of Alison FAULKNER's inquiry into the ethics of survivor research argues: "Research shouldn't be done if there's no intention to get back to the participants" (2004, p.27). [30]

Parallel to its attention to the researcher's identity, survivor-controlled research concentrates on the experience of those taking part in the research and their role in it. This approach to research can also be characterized as a constant re-defining and enlargement of the role of participants in the research process. What started as a criticism of the traditional division of roles into the researcher and the researched now extends far beyond abolishing the role of passive "research subjects." Survivor-controlled research has proven to be quite fast and creative in figuring out methodologies not only to invite but also to enable participants to take part in the analysis, interpretation and dissemination of the findings. These are the areas traditionally reserved for researchers, no matter how participatory or user-involved their approach may be. These parts of the research process (dissemination in particular) are also subject to institutional hierarchies and intellectual property rules. In this sense, the concept of "empowerment," which is considered a key feature in both service user-involved and survivor-controlled research, acquires quite a different meaning and refers to different practices. In survivor-controlled research, empowerment is not done for the participants by anybody else, and nor is it something that can occur only for the participants: "[...] it is often stressed how users can acquire new knowledge and abilities, increase their self-confidence and in distinction to academics, might also experience 'empowerment' through having a role in research" (RUSSO & STASTNY, 2009, p.66) [31]

In survivor-controlled research, empowerment is not a goal declared at the beginning of the project implying that the research is being conducted for the participants' own good or in their interest, and therefore merits their participation. Neither is empowerment intended to be therapeutic. Participants are invited to join the process on the grounds of their knowledge and experience—that is, in order to improve the quality of the research and not so that they may get better. Feeling better and empowered comes as an added benefit, a natural outcome of an interaction in which we are valued and respected as persons, are able to give and take, assume new roles and above all, exert control over the outcomes of our participation: "Information-giving by research participants should be a positive and empowering (rather than mechanical) experience. It may also entail a two way reciprocal relationship of information exchange with the researcher" (TURNER & BERESFORD, 2005, p.vii). [32]

In his critical article "Should service user involvement be considered history?" Theodore STICKLEY (2006, p.574) emphasizes the role of the broader context in which empowerment takes place:

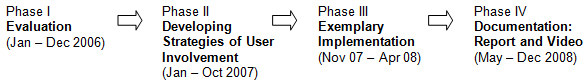

"Empowerment, however, is defined within the existing hierarchies of power inherent within the psychiatric system. For as long as statutory workers empower their clients, actual power is retained (the worker empowers the client). Empowerment therefore as a concept, in spite of its virtuous appeal, reinforced the power position of those who were doing the empowering and maintained the dominant order. Emancipation, however is the potential for individuals to take power, rather than to have it given." [33]

The sense of ownership of the research process is probably the most empowering and emancipatory aspect of survivor research, and this can apply to participants, researchers and the community at large. [34]

Providing continuous feedback to the participants is the key in this process. In their outline of good practice in user-controlled research, TURNER and BERESFORD (2005, p.vii) emphasize feedback to the participants as an aspect of research accountability: "Appropriate feedback and reporting on the research should be ensured to participants at all its stages. They should be kept fully informed of progress and developments (unless they indicate otherwise). This is part of the process of ensuring accountability." [35]

There are different ways to invite participants to engage in analysis and interpretation and to verify the outcomes together. The most common is to convene focus groups of participants after the first stage of the analysis where they become familiar with the initial outcomes of the study as well as with the ways in which the researchers have dealt with the information the participants had provided. Conducting focus groups serves a similar purpose to the communicative validation method used in qualitative research (FLICK, 2010, pp.398-400); however the two approaches also differ significantly. Focus groups are an opportunity to meet other participants and the rest of the research team and to discuss and reflect on the outcomes together. In contrast with communicative validation which takes part with each research participant separately, focus groups are not only a validation method; they aspire to do more than verify the data or assess the analysis. Focus groups in survivor-controlled research set off a collective process whereby participants start to take ownership of the research. Reports of survivor-controlled research usually offer detailed descriptions of the steps taken in these directions, and the best way to explore them is to look at concrete project examples, as I will do in the second part of this article. Alison FAULKNER (2004, pp.26-27) suggests measures that researchers can take to display their approach to data analysis and how they arrived at their conclusions; she also outlines guidelines on how to give feedback to participants throughout the research process. [36]

However the ways in which participants can shape the research are not limited to receiving and providing regular feedback. According to various study designs, they can also take part in conceptualizing further stages of inquiry or joining the research team in a different role. To what extent this occurs is a matter of participants' personal interests and of the project schedule and resources rather than determined by limits or assumptions imposed on the participants' role. [37]

In this very brief outline of the principles of survivor-controlled research, I have left out some other essential elements such as the payment of participants as due acknowledgment of their contributions, and the commitment to propelling change and follow-up action that is integral to this approach. I will address these issues using the example of two German projects below. [38]

3. Survivor-Controlled Research in Germany

To date, there have been two survivor research projects conducted in Germany, both in Berlin. The first of these, carried out back in 2002, can be characterized as a survivor-led project. It was a small scale qualitative study with homeless psychiatric survivors. The second project was a three-year (2006 – 2009) large investigation about service users' experiences of person-centered care. This project was survivor-controlled. Both studies took place outside of academic settings, and to the best of my knowledge, neither survivor-controlled research nor service user involvement in research have yet entered German universities and research institutes in any form. In contrast to the situation in the UK, I am aware of only one single research project that involved service users in the context of psychiatry in Germany (TERPORTEN et al., 1995). This deep neglect of experiential knowledge does not apply only to research but also to the design and reform of psychiatric services. [39]

The appreciation of service user involvement as a valuable strategy to improve mental health services or provide corrective input to psychiatry is just starting in Germany. Despite a vocal movement of service users/survivors (with a national and a number of local and regional organizations), involvement beyond one's individual care is still a very slow process. In recent years, different institutions in charge of psychiatric services have increasingly declared their openness to dialogue with users/survivors, but so far such dialogue has been neither guaranteed nor funded. At the same time, there are noticeable achievements by a very small number of independent survivor-controlled organizations which have succeeded in developing and sustaining their own projects. Their focus is primarily on the provision of non-medical alternatives to psychiatric care, including alternatives to psychiatric community services (HÖLLING, 1999), and not on research. [40]

Research foundations are the main source of funding in German mental health research, and their rules about institutional affiliations and the minimal academic requirements for researchers—a PhD doctorate—make it highly unlikely for psychiatric survivors to obtain funding as principal investigators and project managers. The success of the two early survivor research studies in accessing alternative funding sources gave us the advantage of not needing to compromise our research approach in order to meet funding criteria. [41]

Before I briefly describe these projects, I need to emphasize that they would not have been possible without the UK survivor research experience to inspire, guide, and underpin them. Both German projects were built upon a dialogue with UK survivor researchers which gave them a context and a research community to belong to. Being able to refer to the achievements of specific survivor-controlled research projects and the wider spread of user involvement in research in the UK strengthened our position vis-à-vis funders and throughout the stages of developing methodology and conducting research. A number of factors contributed to the development of German survivor research; for example the direct communication with UK initiatives like the Strategies for Living project, the organization Shaping Our Lives, and the Survivor Researcher Network, as well as my personal work experience at the Service User Research Enterprise, based at the Institute of Psychiatry in London. However a major element was (finding out about) the published works of UK survivor researchers.

Besides the two reports already mentioned (FAULKNER, 2004; TURNER & BERESFORD, 2005), this lively and ongoing process has included some older outstanding project reports (FAULKNER, 1997; FLEISCHMAN & WIGMORE, 2000; FAULKNER & LAYZELL, 2000; ROSE, 2001; NICHOLLS, WRIGHT, WATERS & WELLS, 2003; SHAPING OUR LIVES, 2003) as well as two essential readings for survivor researchers—"The DIY Guide to Survivor Research" (FAULKNER & NICHOLLS, 1999) and "Doing Research Ourselves" (NICHOLLS, 2001). [42]

The following two project outlines will focus primarily on the research process drawing attention only to certain key outcomes. I will try to demonstrate the impact of this research approach and the way both studies significantly broadened and also questioned the existing knowledge of the subjects under investigation. Where relevant, commonalities in the research process of the two studies are also highlighted in the individual project descriptions. [43]

3.1 Taking a stand. Homelessness and psychiatry from survivor perspectives

Conducted over the course of eight months in 2002, this was actually the first German inquiry into homelessness based on interviews with people who are or had been homeless themselves. Its report Taking a Stand: Homelessness and Psychiatry from Survivor Perspectives (RUSSO & FINK, 2003) emerged from 25 such interviews and four focus group discussions held with people who had experienced psychiatric treatment and were using services for the homeless (mostly overnight emergency shelters) at the time of the study. The report states: "We didn't want to talk on behalf of survivors, but with them. This report is the outcome of that dialogue" (p.7). [44]

The study was designed and its funding obtained by a non-survivor (Thomas FINK), who was at that time coordinating a working group that included providers of homeless and mental health services in the city of Berlin. This working group, responsible for assessing service provision and developing new strategies, was hosted by the lead German umbrella organization of independent charities (Der PARITÄTISCHE). The latter, in particular its Department for Psychiatry in Berlin, has proven to be incredibly supportive of German survivor research, beginning with the full funding of its first study with a small grant which also covered the print publication of the research report. [45]

Inspired by the UK study "Nowhere else to go" (FLEISCHMAN & WIGMORE, 2000), Thomas FINK designed an inquiry to address homelessness and psychiatry from a perspective of those directly affected—a perspective that had been completely absent from the working group. He planned to include two survivors of psychiatry as co-workers, but because of changed circumstances affecting both of these persons, I was invited to join, and became the sole survivor-researcher and co-worker on the project. This happened after the project had already been approved and all decisions about the budget had been made. Even though the two members of the research team in this project had equivalent educational backgrounds in psychology, the fee assigned to me as survivor researcher was half that of the non-survivor. Despite this financial inequality, we agreed to conduct the project in an equitable partnership, sharing all the tasks, including data analysis and writing up the report. We tried to compensate for the disparity in payment by assigning all transcription work to the non-survivor. As this was not really a satisfactory or proper solution, we addressed this issue in our report, strongly recommending joint planning from an early stage as well as equal payment for survivor and non-survivor researchers (RUSSO & FINK, 2003, p.104). The second characteristic that made this work a survivor-led rather than a survivor-controlled investigation was the fact that although one of us researchers had personal experience of psychiatric treatment, neither of us had experienced homelessness. Reflecting back on our research work, we were certain that including a researcher with such experience would have improved the study substantially (pp.7, 104). [46]

This study set out to explore, in particular, why despite a considerable number of social and community psychiatric services, some people remained on the street. We wanted to reach those whom services had failed to help and to report on their experiences and opinions: "Our focus was to explore the ability of the care system to adjust to clients' individual circumstances and needs" (p.7) [47]

From the beginning, we were looking for people interested in expounding on these issues with us beyond an initial individual interview. Our description of the study given to the interview partners included an invitation to do further work via focus groups:

"It is important to us to work together with you. This means that we would like us to stay in contact, if you want, after this interview. We would like to invite you to develop proposals together with us about how care could be improved. [...] After we complete the interviews, we would like to discuss certain topics in groups, develop proposals together and publish them in a form of a brochure. We warmly invite you to join us" (p.109). [48]

In both German projects, the initial semi-structured interviews were a place to establish contact with participants while introducing our personal backgrounds and explaining the project and its aims. Each participant was always offered a transcript of his or her interview. Some people were not interested in this transcript while others valued it considerably. Providing each person with a written record of the information she/he contributed is considered good practice in survivor-controlled research. This gesture indicates that the information belongs to the participant and not only to the researcher, and marks the post-interview phase of the research. The participants are invited to take part in further processing of the information they provided and to reflect and interpret the outcomes together with other participants and researchers. This usually takes place via focus groups. In both German projects, focus groups were the place where participants got to know each other and the rest of the research team while exchanging their experiences and opinions. They got to know the interim outcomes of the research and learned about the way researchers were treating the collected material. For the researchers, focus groups are an invaluable opportunity to check whether the analysis and interpretation are going in right direction e.g. addressing issues raised by the participants and thereby remaining accountable and truthful to their experiences. [49]

After the initial rough analysis of 25 interviews in the first project, four focus groups took place. The first focus group started by presenting the main outcomes of the interviews to participants, with a strong emphasis on experiences with shelters for the homeless. A written summary of the previous focus group discussion was distributed at all subsequent meetings, to remind everyone of its main outcomes and to give them a chance to amend, comment, and approve the summary. For us researchers, this was a way to deepen or correct our understanding of the main outcomes of each discussion. The second focus group in this series concentrated on participants' views about psychiatry and psychiatric community services; the third concerned their visions and proposals for ideal housing and crisis support. The final group was dedicated to the format in which the outcomes should be presented. We brought very concrete questions about the ways to present the outcomes including longer extracts of interviews that we wanted to publish but still had concerns about. Participants also made proposals for the layout and photos of the final publication. [50]

The weakest point in our planning was the time gap between completing the interviews and the date of the first focus group. This is an issue for all process-oriented research which aims to build up the next research stage from the outcomes of the previous one: there are periods when analysis needs to be done very quickly in order to be shared and improved with the participants. Berlin shelters for the homeless where we found the majority of our interview partners are only open in the winter time (until the end of March). Having completed transcription and the first round of data analyses rather quickly, we managed to schedule the first focus group two days before the annual closure of the winter shelters. However, all subsequent focus groups had to take place at a time when the participants had already dispersed in many directions and consequently had become much harder to reach, a development that we unfortunately did not foresee in our planning. Even though the attendance of the last three focus groups substantially decreased, the intensity and value of the joint work improved with each group. These discussions enhanced the analysis in a number of ways, mostly by helping us interpret the outcomes correctly, sharpen the focus and set priorities for the report. By the time the first draft of the final report was written we were only able to reach three persons who took part in the whole research process. However, despite this small number, the feedback we received in individual appointments with participants was very valuable. One person gave us a written contribution which we published in the report. [51]

As already mentioned, the focus of this article is primarily on describing the process rather than the findings of the research work. Yet the value of this study is also in certain outcomes that no other study on homelessness in Germany has revealed. I see these outcomes in direct connection not only with the fact that we chose to interview service users instead of professional workers, but also with the overall research approach we have taken. Generally speaking, participants articulated substantial criticism and disappointment with services. The negative role of social services and their potential contribution to people's loss of housing also became clear. One of the most surprising outcomes was the fact that about one-third of the participants used services for the homeless (including overnight shelters) even though they had been allocated flats. The poor quality of that housing and their unfriendly surroundings were often triggers for further mental health crises. Looking for someone to talk to during a crisis, people turned back to shelters for the homeless because of their anonymity and easy access and because they did not require proof of a mental health-related "treatment need." The most attractive feature of the shelters was that they didn't actually provide psychiatric treatment. Despite numerous complaints about the physical conditions at the shelters, people took comfort in the fact that they could just be there, find a non-professional to talk to and feel some protection from the threat of hospital admission. [52]

This outcome clearly indicated a need for non-medical and easily accessible crisis support services. Other findings from the study offered further guidance for improving and re-conceptualizing services. Nevertheless, despite the fact that this report was widely read and acknowledged by policy makers, no effort to reform services in Berlin to this day has taken the outcomes of this study seriously. Its greatest practical value remains the fact that it explained the premise of survivor research for the first time in the German language. Secondly, the potential of this approach to produce outcomes different from conventional studies on homelessness and to retain the language of first-hand experience was clearly demonstrated. [53]

Even though this study was survivor-led rather than survivor-controlled, it proved to be remarkably helpful as a reference in the funding application for a large scale survivor-controlled research project one year later. [54]

3.2 Evaluation and practice project: Person-centered care from the users' perspectives

The philosophy behind person-centered care suggests that the community mental health system should adjust to individuals and their personal needs rather than the other way around. Due to changes in legislation, the main instrument of person-centered care, known as the Treatment and Rehabilitation Plan (Behandlungs- und Rehabilitationsplan), was introduced into community psychiatric services in Berlin in 2001. The new law also brought about a fundamental change in service funding: mental health service providers no longer received public money based on a set number of their users, but on the amount of care provided to each service user. Theoretically, the introduction of the Treatment and Rehabilitation Plan was meant to enhance the rights of service users who were now seen as partners in their own care. A 12-page form to be filled out together with the client and signed by her/him took the place of the previous annual Progress Report that mental health service workers had to issue for each of their clients. [55]

The implementation of person-centered care in Berlin was scientifically evaluated by two different research institutes (INSTITUT FÜR FORSCHUNG, ENTWICKLUNG UND BERATUNG GmbH, 2002; GÖRGEN & OLIVA, 2005). Both evaluations were based exclusively on questionnaires and interviews with professional service workers and service providers. [56]

The idea for the "Evaluation and Practice Project" on person-centered care which aimed to place service user's experiences at the heart of the investigation was developed by a group of people interested in research and affiliated with one survivor-controlled organization in Berlin (Für alle Fälle e.V.). Our motivation was the complete lack of service user involvement in the planning and introduction of person-centered care in Berlin as well as in the monitoring of progress toward this goal. [57]

In order to conduct this research, we successfully applied for funding from a big German foundation for social projects (Aktion Mensch) which manages lottery money. Further support came through the aforementioned lead German umbrella organization of independent charities (Der PARITÄTISCHE), which raised the remaining 25% of our budget among its members—the community psychiatric service providers that we planned to evaluate. As a result, we could begin our work in 2006. [58]

The ensuing three year project was conducted by a non-hierarchical team of four researchers, three of whom had experienced psychiatric treatment. We all had different university degrees and were paid on an equal base. This research qualifies as survivor-controlled since our team designed the study and remained in charge of all project decisions, including funds management. [59]

Our research project aimed to explore the reality of person-centered care and its main tool (the Treatment and Rehabilitation Plan) from a user perspective. At the end of the first project year we issued a report "Aus eigener Sicht. Erfahrungen von NutzerInnen mit der Hilfe" ["From Our Own Perspective. Service Users' Experiences with Person-centered Care"] (LORENZ, RUSSO & SCHEIBE, 2007). However, unlike most evaluation studies, our investigation was meant to go beyond this report. Our work on person-centered care is closely aligned with the features described in Michael TURNER and Peter BERESFORD's investigation of user-controlled research (2005, p.47):

"[…] user controlled research can be seen as a form of 'action research' or of research and development combined, where the goal of making change is built into the research approach, rather than something that is separate and may or may not follow." [60]

The evaluation was just the first phase of our study. Departing from its outcomes, the research team and interested research participants proceeded to develop strategies to intervene in the processes that were subject to the evaluation. Finally, we dedicated the remaining time to propose feasible ways to bring the main findings from the evaluation into the practice of care facilities. [61]

Over the final six months, three of the developed strategies were applied. The research team and the interested research participants worked with two direct service providers and with members of a regional decision-making body. In our final report "Versuch einer Einmischung. Bericht der Praxisarbeit" ["Interference Attempt. Report of the Practice Work"] (RUSSO, SCHEIBE & HAMILTON, 2008) and in the accompanying video documentary "Auf Augenhöhe. Beteiligung von Nutzern und Nutzerinnen an der Hilfe" ["At eye level. User involvement in care"] (SYNOPSIS-FILM, 2008), we reflected on these processes. These materials describe the ways in which we let concrete strategies for user involvement emerge from the research findings. They also give an account of our successes and failures in attempting to actively intervene in psychiatric community services. The following chart shows the main phases of the research.

Illustration 1: Evaluation and practice project, outline [62]

For the purpose of this article I will offer a brief description of the research process divided into the evaluation and practice phase only, rather than all four phases listed above. [63]

Preliminary informal conversations with two service users helped us design a topic guide for a semi-structured interview which covered four main areas:

experiences of care,

experiences with the treatment and rehabilitation plan,

experiences with "case-conferences," and

user's overall opinion on person-centered care. [64]

We distributed project information and invitations to the initial interview at large majority of community psychiatric services of Berlin. Service users interested in taking part contacted our team directly. The interviews took place at participants' preferred venues and lasted for about an hour. All service users who initially gave us an interview were offered the ongoing opportunity to join us in further steps and shape the research. Eighteen of 33 persons joined the focus groups regularly in the first year; 12 participants remained with us for the whole two and half years of the project taking different roles and tasks in research phases after the evaluation. [65]

The results from the interviews were reported back to participants in two focus groups. Based on those outcomes and their discussions and reflections in these groups, the research team drafted a questionnaire aiming to reach larger numbers of service users. We wanted to produce an instrument that addressed issues directly relevant to service users, and hoped to quantify the qualitative outcomes in this way. Besides multiple-choice answers, the questionnaire allowed the option of providing individual answers. It was tested, revised and adopted in the course of the next two focus groups. The final version comprised 36 questions structured under the following four headings:

Your road to services: Information and choices;

Your perspectives on services;

Treatment and rehabilitation plan: Your participation and possibility of co-determination;

A few closing questions. [66]

The research team collected questionnaires during more than 80 visits to different community psychiatric services in Berlin. The outcomes of this survey as well as the main conclusions from the evaluation were again discussed in the focus groups. [67]

The evaluation report (LORENZ et al., 2007) comprises both qualitative and quantitative findings that emerged from the total of 33 interviews, 533 questionnaires, and six focus groups with service users. [68]

The outcomes we reported were quite different from those of the two previous evaluations of person-centered care. One of those evaluations, which addressed the issue of the practical involvement of service users in filling out their own Treatment and Rehabilitation Plan, reported a 93% rate of user involvement (INSTITUT FÜR FORSCHUNG, ENTWICKLUNG UND BERATUNG GmbH, 2002, p.17). This high rate was based on the service workers' answers (n = 391) on a five-option scale to the question "Do you think that clients are sufficiently involved in filling out their Treatment and Rehabilitation Plan?" (quoted in LORENZ et al., 2007, p.114). Our evaluation showed that one-third of the participants (32%; n = 514) were not even aware of their own Treatment and Rehabilitation Plan or could no longer recall it. Users frequently reported that they felt pressure to sign the Treatment and Rehabilitation Plan in order to safeguard their place in a service. This finding was of particular concern since most community services also provide housing. Our investigation made it clear that service users' signatures did not necessarily imply their agreement with everything that the official plans contained. Some other key findings included:

an unambiguous negative correlation between guardianship and the degree of choice that people experienced on their road to services,

the most important aspect of care for participants is being able to talk to the staff,

a clear correlation between users' attitudes to medication and the extent to which they felt able to talk to the staff about this: those people who experienced medication as helpful felt far freer to broach this topic with staff than those who were unhappy about it or were contemplating coming off drugs. [69]

Even though these findings might not be surprising, especially to service users, this study marked the first time in Germany that they had been systematically explored and documented in the form of a research report. The outcomes of this evaluation are hard to ignore, not only because of the quality and comprehensiveness of the report but also because of the size of its sample. In the project application, we had announced the intention to collect 150 questionnaires, but after receiving funding, we immediately decided to triple this number. In the end, a total of 566 service users took part in the evaluation phase. Despite the fact that 13 of the 41 Berlin service providers denied us access to their clients, we were able to reach more than 10% of Berlin service users. Because of the interest the report aroused, we received additional funding to publish it as a hard copy. As expected from the project design, the evaluation report marked a turning point rather than the end of the project. [70]

The phase following the evaluation marked a shift in roles: from this point onwards, the focus groups were more than the place where the outcomes were jointly verified, discussed, and analyzed. In the practice phase, the participants were invited to shape the rest of the research; the focus groups, thus, provided an opportunity to prioritize the areas for practice work and to conceptualize the interventions in services that we would initiate on the basis of the evaluation outcomes. From this stage, the co-work of research participants no longer took place only via the focus groups. The following outline of the practice work includes a description of new roles, acquired by both the participants and the researchers. [71]

We started by jointly developing questions for service workers. Together with the participants we designed a structured interview schedule. The interview with the researchers offered professional staff the chance to engage with users' perspectives on central issues of care while also sharing their own experiences and opinions. The research team conducted 25 individual interviews with staff members and five group interviews with teams of mental health workers. Following the same principles as in our work with service users we invited staff who gave us an interview to learn about the findings, discuss and reflect them in two focus groups. The initial intent of this small scale investigation into professional workers' perspectives was to help us prepare interventions in services and figure out what would be viable. Knowing, however, how rarely surveys with professionals comprise questions developed by service users and having gained further valuable insights into the reality of person-centered care, we decided to publish an interim report on these outcomes as well (RUSSO & SCHEIBE, 2008). [72]

After presenting the staff perspectives to the service user participants in the focus groups, we jointly set priorities for potential areas of intervention in services. In this phase, we also initiated working groups which we called expert rounds. These consisted of project participants, both service users and staff who did not have any previous relationships with each other in the context of treatment or care provision. These meetings were prepared and facilitated by the research team with the purpose of jointly elaborating concrete strategies for interventions during the practice phase. Besides aiming at developing feasible and realistic intervention strategies, we initiated the expert rounds in order to rehearse the working partnership between service users and professional staff in a context which is separate from their usual role divisions in services and where their different experiential backgrounds and expertise are equally valued. [73]

Our evaluation of person-centered care revealed many potential and urgent areas for intervention, which could barely be touched during our short practice phase. The agenda we developed in the course of four expert rounds comprised three different strategies for further trials:

Internal evaluation of one occupational day center: service users of the center would develop standards for quality assessment of the contents of the day program offered in this center as well as the work of individual staff members. Subsequently, our team, enhanced by one service user project participant, conducted an internal inquiry into the quality of this day center according to user-defined criteria.

A series of three survivor-led training sessions for the residents and the staff of a therapeutic shared living facility. The overall topic of these joint trainings was non-medical crisis support.

Direct dialogue between the project participants and a decision-making body of the Berlin state government responsible for the introduction of person-centered care (applying the methodology of the three expert rounds). [74]

Service user participants in the project took on concrete tasks and responsibilities during the practice phase. I have to emphasize here that participants were at all times paid for their involvement. Although their involvement at all stages of research was planned, our team could not predict what the practice phase would look like or what roles the participants might take. Their increased involvement required a re-structuring of the budget, however the fact that survivor researchers were also in control of finances enabled us to make flexible decisions according to the project's needs. [75]

Our most difficult practice intervention was the attempt to discuss crisis support within a particular service. Personal conflicts and attempts to clarify past situations where the service workers had admitted clients to a psychiatric hospital seemed unavoidable. We considered the dialogue with governmental representatives (the last strategy listed above) to be the most successful part of our practical work. This was the first time since the introduction of person-centered care in Berlin that the underlying "theory" had been checked against the way care was experienced by service users. Furthermore, this was the only part of our work that continued after the research project had been completed. It also resulted in some concrete changes in the next revision of the Treatment and Rehabilitation Plan. [76]

Apart from demonstrating the value and potential of survivor-controlled evaluation, this project is important for exposing the lack of service user involvement into purportedly "person-centered" care and introducing such involvement retroactively. This refers to the kind of involvement that goes beyond a person's individual care and engages the areas of service development, delivery and evaluation. Our work did not have the formal power to affect any systemic changes, but we noticed that reflective processes began in many different places and with different stakeholders. [77]

Above all this project was a learning experience for everyone involved, including our research team. A research process in which people who initially gave us an interview were consulted throughout the study as foreseen but were also able to acquire different roles at later stages of the project and thereby shaped the research has demonstrated that we cannot talk of survivor-controlled research in terms of any readymade formula or pre-defined technique. Survivor-controlled research is also more than trust and closeness between the researchers and the participants grounded in their shared identity. The values and principles implicit to this approach do not allow for strict predetermination of participant roles and a set level and direction of their involvement. Survivor-controlled research invites participants into a collaborative process in order to enhance the truthfulness and capture the complexity of the outcomes. While the roles of researchers and participants remain different throughout the course of the research, the ownership of the whole process and its outcomes becomes increasingly shared. This growing sense of the participants' ownership over this project was expressed in the fact that a large majority of those who wrote a contribution to the final report wanted their full names published. Project participant Barbara BORTZ wrote in the final report (RUSSO et al., 2008, pp.79f.):

"Perhaps your work will contribute to service workers being scrutinized more critically in the future. It gives me great satisfaction that our statements are being brought to the public! Furthermore, I wish there existed an objective body to critically monitor the work of psychiatry. Still, medication can no longer be administered on such a massive scale, and it can't be that there is no other approach to people across the board. One hopes that the intensive work of so many people on this project will open doors and that the many legitimate concerns of survivors will finally be heard and not 'psychologised'." [78]

The fact that this evaluation and practice work took place at the initiative of a survivor-controlled NGO ensured our independence; it also gave us the freedom to conceptualize the work according to our own values rather than on the basis of somebody else's interests and expectations. Less favorable aspects of the experience were that the organization in question did not really have an interest in research and that working in a non-hierarchical team also turned out to be very difficult. The workload was very large, and all the survivor researchers left the organization after completing the project. So there is a real danger that possible future interest in these kinds of evaluations may not be able to rely on an independent survivor-controlled organization with the capacity to carry out this work. As certain parallels can be observed with some of the UK projects, it is worth thoroughly exploring the question of—why it is that survivor-controlled research may risk turning into a one-time event and face limited future. In my closing remarks on prospects of survivor research I will take on only some of the related issues. [79]

In conclusion of this brief overview of survivor research in Germany I find it important to highlight that this research approach has produced its own publicly available outcomes prior to entering any potential collaboration with academics. These projects have delivered high quality reports that demonstrate that while survivor-controlled research takes a different position, this does not affect its professionalism. The fact that these reports are qualitatively commensurate with mainstream publications will hopefully determine the nature of future partnerships in German mental health research. I am convinced that the inclusion of first-person knowledge is an unavoidable stage in the development of psychiatric and mental health research but I am also aware that there are different ways in which this process might begin. The course it takes will depend on the different systems of health care and service provision in place and the nature of their funding, as well as on historical and cultural factors. I would like to believe that the fact that the first two German survivor research projects took place wholly independently of established research foundations and their institutional rules, will prove decisive in establishing an equal footing for our future dialogue with mainstream researchers. [80]

4. The Prospects for Survivor-Controlled Research

Challenging established power relations in research and employing radically different approaches, survivor-controlled studies have proven capable of revealing perspectives that have been historically excluded from mental health and psychiatric research practice. The potential of these studies to produce different outcomes to those generated by conventional research is clear. Such outcomes can moreover fundamentally question mainstream practices. Nevertheless, despite its considerable progress, this research direction faces major barriers in the effort to gain acknowledgment and secure a future. [81]

Part of these barriers certainly comes from the external circumstances and the broader scientific context in which survivor-controlled research attempts to establish itself. At the same time, they derive from the philosophy of the movement that survivor-controlled research is rooted in, or to be more precise—the lack of such a philosophy. [82]

In terms of external obstacles—no matter how appealing and encouraging the initial discovery of research done by survivors might have seemed to some academics—their rapid co-optation of our perspectives in order to extend and enrich their own has inhibited further autonomous development of survivor-controlled research. The participatory approach promoted by the UK government and many funding bodies has certainly led to the acknowledgment of experiential knowledge as a valuable source of evidence; it has probably also improved the quality of some mainstream psychiatric studies. Ultimately I believe that it has also helped diminish what started as service user/survivor control of research to mere user involvement. Michael TURNER and Peter BERESFORD (2005, p.x) report:

"There has been a much greater focus in research on user involvement in research, although service users have highlighted its significant limitations. In addition most funding has been devoted to supporting user involvement in research and proportionately very little to take forward user controlled research." [83]

I would like to believe that survivor-controlled research will find a way to avoid being squeezed into so-called collaborative projects, which often prove to be unequal partnerships and do not necessarily challenge the biomedical premises of psychiatric and mental health research. [84]

Even in countries where survivor-controlled research is no longer a foreign concept, it has been subject to some worrisome and sad developments:

"Paradoxically, user-controlled research almost certainly has the longest history of any form of user involvement in research (Turner and Beresford, 2005a; Branfield et al. 2006). Yet there are strong reasons to believe that it remains the most marginalized and insecure expression of such research. This contradiction perhaps highlights both the strengths and weaknesses of user-controlled research. For its exponents, it may represent the strongest and most developed expression of user involvement in research. In the broader context of research overall, however, it can expect to be treated with the greatest caution and subject to most formidable barriers" (BERESFORD, 2009, p.181). [85]

As a frequent funder of mental health and psychiatric research, the pharmaceutical industry has a powerful and determining influence over the research agenda. Irrespective of whether such research has a service user-involved or service user-informed element, it remains incompatible with the topics and principles central to survivor-controlled research. It is my strong opinion that survivor-controlled research in opposition to a large share of mainstream mental health research can maintain its freedom to express its views and to question the dominant perspectives in mental health only by virtue of its independence from pharmaceutical funding. [86]

Service users/survivors and their organizations run into considerable difficulties when they try to obtain public funding for their independent projects, especially those with substantial budgets. Just as individual service users/survivors face discrimination and denial of their ability to think and act rationally over the long term, we are similarly confronted with a stigmatizing attitude when applying for funding. The fact that most of our organizations can not demonstrate a track record of managing larger budgets or have no co-funding capacity turns our competition with well established research institutes into a mission impossible. [87]

Survivor researchers remain under great pressure to obtain the highest possible academic degrees as a minimum if they are to stand a chance of obtaining a decision-making position in research. Due to our interrupted educational paths and careers, it usually takes us longer to achieve the formal requirements for gaining access to such roles. UK survivor researcher Heather STRAUGHAN (2009, p.108) provides a powerful and honest account of her personal motivation to complete a PhD:

"Effectively, to win them over or to beat them, I had to join them. I had to achieve the similarly highly held status of a 'doctor'. In order to influence change, I had to take the account of the perspective they had in evaluating the research they considered worthy. […] I had to ensure a presence amongst them." [88]

Even when academic titles are achieved, the training involved usually does not include the values and principles of survivor-controlled research. One of the obstacles to the development of survivor research certainly comprises the lack of accessible specialist training (TURNER & BERESFORD, 2005, pp.ix-x). [89]

Before commenting explicitly on the obstacles for survivor research from within, I would refer to the telling statement by Peter BERESFORD and Jan WALLCRAFT about the context in which survivor research now struggles to achieve recognition and a future: "As far as the dominant debate is concerned, survivors and the survivors' movement still seem to be primarily seen as a source of experiential data, rather than creators of our own analysis and theory" (1997, p.72). [90]

4.2 Facing up to barriers from the inside. Taking on the challenge

Any attempt to distinguish between external and internal obstacles for survivor-controlled research is certainly oversimplified; in fact, these issues cannot easily be distinguished as they prove to be quite interconnected. What I perceive to be a particular difficulty from within relates to the user/survivor movement from which survivor-controlled research emerges as a way of "developing survivors' own knowledge collectively" (p.75). The fact remains that we have never developed our own theory of madness and distress to underpin our research work. In its absence, different theories about us continue to be created, some of which come closer to understanding our experiences than others. We tend to favor some of these and to reject others but none of these theories have come from a systematic and thorough investigation of our own knowledge. However different they may be from each other, all established theories of madness and distress have in common the fact that they were neither developed nor authored by the owners of those experiences. In their comprehensive comparison of survivor and emancipatory disability research, Peter BERESFORD and Jan WALLCRAFT write:

"The survivors' movement therefore doesn't have a clear philosophy of its own. This has long been seen by many of its members as one of its strengths and attractions. It has had the appeal of being a broad church, where people of very different experience, background, education and politics, could co-exist. [...] There has been no pressure to confirm a particular belief system" (p.68). [91]

Further on, they explain:

"This does not mean that the movement is not informed by values and ideals. [...] Survivors know that psychiatric judgments on and interpretations of them do not rule. In this sense, there is a challenge to the dominant ideology, but so far it has not developed into a shared alternative analysis and vision of distress" (p.68). [92]

There have certainly been many reasons why the survivors' movement has not reached far beyond pointing out what is wrong with the biomedical model as well as with other frameworks focusing on pathology. I have already mentioned that those who have undergone psychiatric labeling of their life experiences and personalities are likely to be very resistant to and skeptical about any kind of theoretical model. In addition, there are many obstacles to developing our own knowledge within a movement that still places the fight for human rights at the forefront of its agenda. We are not well-resourced and, in particular, lack any independent survivor research institutes with the capacity to conduct comprehensive and systematic investigations of survivor knowledge. In the meantime, this research topic has begun to be attractive and accessible to non-survivor academics. Obtaining funding to take exploratory journeys through our movement, these researchers have again imposed their perspective on us, keeping us silent once again (see HORNSTEIN, 2009). I perceive these recent survivor-friendly efforts as a continuation and repetition of traditional role divisions in mental health research and would draw here on Peter BERESFORD's (2005, p.4) powerful call for a rethinking the role of distance in knowledge production:

"Traditionally, conventional research and researchers appropriated the experience of research participants arguing that they themselves were better equipped to interpret it because of their own 'distance' from the experience. It is perhaps now time for mental health and other service users to question such assumptions that:

the greater the distance there is between direct experience and its interpretation, the more reliable it is

and explore instead the evidence and the theoretical framework for testing out whether:

the shorter the distance there is between direct experience and its interpretation (as for example can be offered by user involvement in research and particularly user controlled research), then the less distorted, inaccurate and damaging resulting knowledge is likely to be." (Italics in the original) [93]

My perspective on internal obstacles for survivor research is in no way intended as criticism in hindsight of the survivor movement for not being clear or focused enough. Nor does it amount to a proposal to establish a "stronger party line." I believe that any such turn would result in the loss of a valuable dialogue not only among the two main streams of the movement, but also among its many diverse members. Even so, I do maintain that the achievements of the movement so far, which includes the accomplishments of survivor-controlled research, are posing new demands on us. If our accumulated knowledge is not to be appropriated by anyone whatsoever for their own purposes, than it is high time to develop our own framework. Peter BERESFORD refers to survivor-controlled research as "a truly new departure" and urges that

"[…] unless we can make a strong case for the differences it embodies, ultimately it may be marginalized. We need to look more carefully at where it comes from and what it may be able to offer. It is unlikely to be enough to make the moral case for it, important though this is, yet so far this has been the main argument offered" (p.6). [94]

If survivor research has found ways to enable so many silenced voices and devalued experiences to be heard and comprehended, then it must be capable of coming up with its own framework that does justice to this knowledge and permits its further expansion. In this way, its collective echo may become louder, stronger and impossible to ignore. [95]

The author warmly thanks Debra SHULKES for her extensive editing work on the first draft of this article and Peter STASTNY for all his support with the revision.

1) The expression "survivor-controlled research" throughout this article refers also to the work known as user-controlled research. <back>

2) The expression "survivor research" is applied as a shorten form of survivor-controlled research but means the same throughout the text. <back>

3) "Petition of the Poor Distracted Folk of Bedlam" from 1620; also cited in The Opal Project's Ourstory of Commitment: A Living History. <back>