Volume 13, No. 1, Art. 16 – January 2012

Tricks of the Trade—Negotiations and Dealings between Researchers, Teachers and Students1)

Veronika Wöhrer & Bernhard Höcher

Abstract: We introduce several social research projects carried out by five junior researchers and 17 11-13-year-old pupils at a secondary modern school in Vienna. We describe processes of negotiations between researchers, pupils and the teacher about the framework, time, data, methods, spaces, attention, dedication and financial matters, i.e. about many crucial aspects of a research process. In these discussions and negotiations the students proved to be good observers and users of social science knowledge. A closer analysis of our own positions in these encounters leads us to elaborate on two critical moments of participatory action research (PAR) projects at school. The mixing of different roles, tasks and expectations in working with children in a school context can produce disappointment on the part of the students and difficulties and excessive demands on the part of the trained researchers. A second problem is that the knowledge produced in such cooperative projects is not easily recognised and valued—either at school or in academia. We conclude with our own definition of participation, action and research in this context and discuss the fact that a commonly reached understanding of conclusions and goals might not be possible in PAR projects. We nevertheless think that PAR is a fruitful research practice, because we perceive the negotiations and the mutual convergences and learning efforts that were made by all participants as enrichment for the students, the teacher and the trained researchers.

Key words: participatory action research; children's research; social science knowledge; negotiation; boundary object; mutual learning

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. Background

3. Research Process

4. Negotiations and Dealings

4.1 Framework and time

4.2 Time and data

4.3 Data and method

4.4 Method and space

4.5 Space and attention

4.6 Attention and dedication

4.7 Dedication and money

5. Conclusions

6. Discussion

In this article we describe our own research process in a participatory action research project with 11-13-year-old pupils at a secondary modern school in the capital of Austria (the Austrian term of this type of school is Kooperative Mittelschule [KMS]). Our main research interests were examining intersectional aspects of acquiring knowledge at school as well as the methodological issue of how to do social scientific research with children of this age from a working class and migrant background. We elaborate on some of our results, but mainly we use our own research as empirical data to make some analysis of participatory action research (PAR) and action research (AR). [1]

We introduce and analyse the positions of the trained researchers, the teacher and the students in our research process. In the course of the project (and later on in the course of writing this text) trained researchers, students and the teacher were subjects as well as objects of research: Analysing our own social practices and our research practices became integral parts of our social research groups. Even though we mainly worked with and focused on the students, the teacher was an important person in our fieldwork too. She not only organised and guaranteed the framework for our research on the part of the school, but she also partly participated in the research, gave feedback and wrote texts for the main textual output, the project's homepage. [2]

Accordingly, this text is meant as a methodological analysis of PAR as well as a contribution to the question of how teenage pupils use, perform and contextualise social-science knowledge. We therefore give an account of several incidents from our research process. We focus on processes of negotiations between researchers, teachers and students. Negotiations are often described as crucial in ethnographic as well as (participatory) action research (NOFFKE & SOMEKH, 2008; FLICK, 1991; WOLFF, 2004). In our case, negotiations covered the issues of framework, time, data, methods, spaces, attention, dedication and financial matters, in short: the most vital aspects of a regular research process. This is especially interesting as the questions "What is social research?" and "How is social research done?" were always implicit and explicit topics in our common undertakings. So our negotiations on these topics simultaneously showed two things: they not only meant that a lot of our fieldwork was contested and commonly discussed, but they also showed that the students (and the teacher) had decoded the main points of a research process. [3]

Among other things (e.g. an ambition to change social practices) being "active" in the field is an agreed upon characteristic of PAR as well as AR. Nevertheless, we think that the many facets, enrichments and constraints produced by the intensive involvement in the field are not fully explored in the literature on PAR. While a lot of literature on qualitative research methods deals with field entry, going native, field involvement etc. in great detail (e.g. LÜDERS, 2004; WOLFF, 2004), some PAR texts seem to be rather quick to assume a "first-person perspective", research conducted by "us" without describing who "us" precisely is or how "us" was formed. Stephan KEMMIS and Robin McTAGGART (2000, p.585) for example write: "The researcher is therefore predisposed to regard such people as members of a group understood as 'us'—that is, in the first person." Unfortunately, it remains unclear how exactly a group of co-researchers and researcher(s) become a common research group and how far they perceive themselves as "us" (and who might be perceived as "them"?). [4]

How and when do "I" and "you" or "I" and "I" (McNIFF & WHITEHEAD, 2006) actually become "us"? Considering our experiences, we think that this process is difficult, and sometimes it is not possible to reach common understandings or goals. Accordingly, when we speak of "we" or "us" in this text this refers solely to the authors of this text and not even to all trained researchers in our team, as we repeatedly differed in our opinions, estimations and actions. However, we do not think that this should lead to rejection of PAR. We think that it is possible to work together and follow a common research process without necessarily agreeing on common goals or conclusions. We want to use the concept of "boundary objects", developed by Susan L. STAR and James R. GRIESEMER (1989) in their analyses of the foundation of the Berkeley Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, to illustrate this idea. STAR and GRIESEMER show that objects that inhabit several social worlds and have meaning in each of them may function very well as communication tools in processes of knowledge production—even when all parties involved have different understandings of these objects. We appreciate the recognition of materials and the approval of heterogeneity in this concept. (We will come back to a more substantial explanation of this concept in Section 4.4) [5]

In the following chapters we will describe the background and the setting of our research project. We will illustrate the research process and indicate some negotiation processes in the course of establishing research topics and time frame. We will then go into more detail about seven different processes of negotiations with (different) students and the teacher. We will show that these negotiations covered many important aspects of a research process. Furthermore we will see that in their discussions and negotiations the students proved to be good observers and users of social scientific knowledge. We identify two critical moments of carrying out PAR at school: one aspect is inter- and intra-role tensions on the part of all participants; another problem seems to result from the hybridity of the knowledge that is commonly produced. (Re-)tying it to the fields and institutions the (co-)researchers come from (family, school, university, etc.) needs further translation and reduction processes. We nevertheless think that PAR is possible and fruitful. We agree with Donna HARAWAY (1997, p.36) that: "The point is to make a difference in the world, to cast our lot for some ways of life and not others. To do that, one must be in the action, be infinite and dirty, not transcendent and clean." In our process of dirty knowledge production we began to perceive boundary objects as helpful agents in a common process of discussion and mutual learning. [6]

The findings presented here result from the two-year research project "Tricks of the trade: field research with pupils", which was financed by the Austrian Ministry of Science and Research in the course of the "Sparkling Science" programme. The subtitle of the programme is Wissenschaft ruft Schule. Schule ruft Wissenschaft [Science Calls School, School Calls Science] and its main issue is to fund projects in which students and professional researchers do science together. As its most important goal is to improve the crossover from schools to universities most research projects in fact work with high schools or other schools leading to general qualifications for university entrance. We liked the idea of doing scientific research with students: we had done a research project about a children's museum before and had found that children very well knew what they liked and why, that they created their own explanations and theories (HARRASSER et al., 2011) and we thought it would be a challenging project to integrate students into a social science research process as co-researchers. However, we wanted to work with pupils who will not necessarily have the chance to go to university and study social sciences later in their lives. So we decided to work with a secondary modern school. In the Austrian context this is a school for 10-14-year-old children, ending with a secondary general school certificate, which mainly enables pupils to attend vocational training. Our hopes behind this were that these experiences would be enriching for the students and enlightening for us. We thought that it might be rewarding for the students to analyse and question social realities: trying and learning to discuss and challenge seemingly "given" societal structures and options were important experiences for us during our studies of social sciences. We wanted to work on such experiences with students who will most probably not go to university themselves. We also hoped to learn a lot from the students: their ideas and points of view on education and (social) research are rarely heard in the literature and might provide new and thought-provoking insights. [7]

There have been several participatory action research projects carried out in school contexts, but mostly they are embedded in "teacher research" initiatives and/or focus on school reforms (ALTRICHTER & POSCH, 1998; ANDERSON, 1998; ANDERSON, HERR & NIHLEN, 2007; COCHRAN-SMITH & LYTLE, 1992; ERICKSON & CHRISTMAN, 1996; McNIFF & WHITEHEAD, 2006; WAGNER, 1999). In teacher research projects, teachers conduct research in their own classes; sometimes they work with researchers from "outside", sometimes they exchange with other teachers (COCHRAN-SMITH & LYTLE, 1992). In studies on school reforms (conducted as teacher research or with trained researchers from outside school) one or several schools as institutions are the main topics of the research and researchers almost exclusively work with teachers and/or parents as co-researchers. Students were mostly integrated as objects of research or addressed as co-researchers only in later stages of the research process (ERICKSON & CHRISTMAN, 1996). Accordingly, Susan NOFFKE and Bridget SOMEKH (2008, p.93) state that "very few educational action research projects look at issues from the standpoint of the students." [8]

On the other hand there are attempts to do "children's research", i.e. to educate children to do their own social scientific research projects (KELLETT, 2005; see also the Children's Research Centre, Milton Keynes, UK). Some of these projects address able children. Mostly the working sessions were extracurricular, after school, some took place on a university campus. Accordingly, they mostly reached middle-class children and Mary KELLETT (2005, p.17) concludes:

"Diversity issues also loomed large as the problems outlined above [she refers to access problems (transport arrangements for getting children onto campus), children being tired at the end of a school day (concentration and energy levels) and competing constraints on their time (e.g. homework, exam revision, other extra-curricular activities)] had greater effects on children from disadvantaged backgrounds. Clearly, there is a long way to go before diversity issues can be fully and inclusively addressed." [9]

The structure of the Austrian school system and our intention to work with students who are sometimes described as "educationally deprived" shaped our research setting. In Austria there are no comprehensive schools, but students are separated very early: At the age of 10 they (or their parents and/or the class teacher) have to decide whether they will attend grammar school, can do A levels and continue to higher education or if they will go to secondary modern school (KMS), where many of them move out of the education system into vocational training or unskilled work at the age of 15. Many students from working class and/or migrant backgrounds attend the second type of school. This means that in Austria many pupils from a working class and/or migrant background do not attend school after the age of 15 or after nine years of obligatory school attendance (ERLER, 2007; WEISS, 2007). This local specificity results in a contrast to another set of PAR studies with students: there have been research projects on participatory research with students from minority backgrounds, which have very similar goals and methods to ours. Social scientists went to schools, worked with students as co-researchers and researched their everyday lives, their communities or school conditions. In these settings teachers were in charge of the basic conditions at the school; they were mediators and sometimes also co-researchers (e.g. OLITSKY & WEATHERS, 2005; RIECKEN, STRONG-WILSON, CONIBEAR, MICHEL & RIECKEN, 2005). However, students in these projects were 16-18 years old and therefore had different interests, motivations and capacities to the 11-13-year-old pupils in our study. [10]

Conceptually, our research was located at the borders of the sociology of science, children's research and participatory action research at school. We were not "asked" to come to the school to change things, but we were welcomed. The desire for changes that we met differed between different participants. Our definitions of PAR varied for all of us (among the trained researchers, among the co-researchers and among the co-researchers and researchers) and changed during the research process. [11]

Our co-researchers were 16 or 17 students, all in the same school class, between 11 and 13 years old, and their class teacher Ms Schmidt. We accompanied the students for two years. Two thirds of the class were boys: 10 boys, 6 girls in the first year, 10 boys and 7 girls in the second. We found a high fluctuation of pupils changing class or school: about a third of the pupils changed. Almost all of them were from a migrant background (first or second generation), mostly Turkish, but also Bosnian, Serbian or Chechen. In each year there was one boy with a German-speaking Austrian background. Some children faced difficult situations in their families (e.g. parents had died, parents had been assaulted, alcoholism, unemployment). As we wanted to give all of these children a chance to participate in the research project, we made social research a class project. This means that the students did not have to spend extra time, travel effort or money to participate in the project. Some of them, who wanted to participate more intensely and continue research when the school project was finished, were regularly picked up at school and invited to come to our office and use its resources. This setting enabled more children to participate, but meant that the trained researchers did additional organisational work (picking up children, ensuring office space, providing lunches etc.). As discussed and recommended within children's research as well as disability research, we tried to allow for "informed dissent" (MORROW & RICHARDS, 1996, p.102) or "differing degrees of participation" (MERCER, 2002, p.241). In the first part of the project, which took place at the school, the students could choose art lessons instead of research and in the second part in our office their participation was completely voluntary. [12]

According to the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child our co-researchers are perceived as "children", which is also the term the teacher most frequently used. We mostly called them "pupils" or "students", and at the end of the project "teenagers". MORROW and RICHARDS (1996) as well as THOMAS and O'KANE (1998) both refer to a conference paper by Allison JAMES in their articles on ethics of (participatory) social research with children. JAMES worked out four overlapping ideal types of ways in which children are perceived: the developing child, the tribal child, the adult child and the social child (MORROW & RICHARDS, 1996, p.99). Our own approach started with a perception rather close to the "adult child", where children are seen as "competent participants in a shared, but adult centred world" and moved closer to the "social child" perspective in the course of our project. The latter model suggests that children are comparable with adults but have different competences (p.100). The change in our perception was not so much regarding appropriate research methods (we tried to consider the students' age and some of their reluctance to "just sit and talk" or "write all the time"), but in our increasing recognition of the limited rights and competences they were given in the school context. [13]

Basically, we agree with THOMAS and O'KANE (1998) that a participatory approach can reduce ethical problems in research with children. In our research the students were seen and addressed as competent actors whose ideas are important, they could choose the degree and form of their participation (research question, methods, groups they wanted to work with, etc.), they were involved in analyses and they could co-determine the dissemination of the results. Nevertheless, we want to stress MORROW and RICHARDS' point that "ethical considerations need to be situational and context specific and, above all, ongoing throughout the process of research, from inception to dissemination of findings" (1996, p.96). This holds true for all types of research—participatory or not. We experienced that difficult situations with regard to ethics (e.g. punching, conflicts, violence, etc.) can arise in all stages of the project and the researchers should be prepared to handle such situations. [14]

The five trained social researchers in this project were four women and one man, all of us were rather young researchers, four trained sociologists and one historian. All of us were on short-term, part-time contracts with a small research association. Three researchers had experience of training and education (partly with children), two did not. Coming from different class backgrounds, some of us have had non-linear educational paths ourselves (secondary modern school, school for kindergarten pedagogics, secondary technical college, etc.), others followed the "typical path": graduating from grammar school and attending university. All of us were born in Austria and belong to the ethnic majority. In the team we often discussed ethical issues and how to approach the students. We tried to support each other when difficult situations arose. But as we were working alone or in teams of two and our interventions had to be spontaneous, it turned out that all of us developed different ways of dealing with sensitive issues. [15]

We had intended to work with the same teacher and pupils for two years. We wanted to meet the students regularly and spend some extra "project days" every semester. Our initial plan was to investigate learning institutions together. In the first year we wanted to focus on the school, in the second year we would visit a university laboratory in which animals are raised. [16]

In the first year in fact we met the students every other week for two afternoon lessons throughout the school year and had one more intense "project day" in spring. All the sessions were recorded on audiotape and all researchers involved wrote observation notes on these sessions.2) Further to this we observed and worked with the pupils on three additional excursions, which were organised by the teacher, and wrote observation notes on these days too. [17]

In the first months of the project we started with a few sessions working on questions such as: What is (social) research? What are social categories? What are rules at school? In this period we were mostly working with the whole group of students. In one of these sessions before Christmas the children expressed doubts. The researchers who conducted this unit were confronted with open scepticism and resistance to their suggested inputs and exercises. Hence the two researchers tried to channel these perceived reservations onto a poster. The students wrote (and asked) questions like: Why is research always that boring? Why don't we do anything? Why are we always talking? etc. [18]

In the following team meeting we discussed this event a lot and planned individual interviews for after the Christmas holidays. We wanted to find out more about the needs and interests of the students—and we also shared their perception that at least the latest sessions had been more talking than doing research. [19]

After carrying out the interviews and checking the outcomes of the "box for research questions", we had set up in class in early December, we organised their various questions under more abstract topics, categorised and transformed them into possible research topics and at the beginning of the second semester we went back to school with a new plan. We organised a kind of "exhibition" in the classroom, decorated each research topic with artefacts, pictures, publications, methods and tools we associated to them. We had four research topics arranged into four physical stations, each looked after by a researcher. The stations were called "School—a wondrous place", "Spaces & places for pupils?!", "Feelings and other relational things", "Where do we come from and where are we going?" (the last title was to hint at migration, but neither necessarily nor exclusively at transnational migration). The students were invited to move around, look, pick things up, try, ask questions and finally decide individually for one of the topics, which they would research for this semester. [20]

The children wandered around and in the end formed two gender-segregated groups:3) a boys' group on "Spaces & places for pupils", which later became "(No) Space for boys?" and a girls' group on "Feelings and other relational things", which later became two groups researching "Places for love at school" and "Chatting". [21]

These groups then worked independently for the whole semester, each of them accompanied by one or two trained researchers. The teacher provided the framework and organised one day of excursion, where all groups came to our office and worked there. She was only rarely present at the research lessons as she had to teach other children. [22]

In the second year the teacher and the researchers wanted to change the setting: we decided to have more concentrated time for research. This meant that there were a few meetings with the students and then one project week of research. As a lot of pupils were new and the others had grown, we wanted to check what they were interested in afresh, so we carried out individual interviews again. We asked (among other things) what topic they would be interested in and what children they would want to work with, or would not want to work with at all. As most of the students had already remarked at the end of the first year, none of them was interested in the animal lab or in biology more generally. So we decided to shelve our plans and carry on with researching issues the pupils themselves were interested in. This time the proposed research groups were on "football", "vocation and research", and "migration". We had originally planned to do gender-segregated groups, as most students wanted to be with others of their own gender, but it turned out that two girls wanted to be in football (and later founded their own subgroup on "women's football") and that the group on vocation became co-educative for organisational reasons (which will be explained in Section 4.5). The research group on migration remained as planned, as it consisted of girls who had explicitly stressed that they wanted to work with girls only.4) A week later the students presented the results of the project week at school informing the others about what they had researched. [23]

After the presentation our official school cooperation came to an end. Neither the school year nor our project time was over, but the teacher thought that she should go on with her ordinary teaching. She expressed the feeling that analysing love, chatting or football (to give the most controversial of the research topics) was not of much use for the students, as they in fact face hard realities: almost all of them are in the weakest "ability group" in all main subjects. This means that when they finish this school (when they are 14 years old), they will not be able to go to attend grammar school or any other further school education, but have to do another year of obligatory school training [Polytechnischer Lehrgang] and then do vocational training. Not all of the students will manage to graduate from the KMS (just recently we learned that this applied to one third of the students), which means that they will not even have the lowest of all possible school certificates. Their only chances on the (official) labour market are as unskilled workers. The teacher therefore thought that it made more sense to teach them things they might "really need". The teacher and the researchers agreed that many students had liked these "research lessons" and had started to understand what analysing one's own environment is all about. Besides these more abstract things, they had the chance to learn skills such as interviewing, presenting in front of groups, using special software etc. Even though the teacher and the researchers saw that some students had benefited from this project a lot, the teacher thought that, due to the way the school system and restricted access to education are structured, other things were more important for the students than learning how to do social research. [24]

The trained researchers therefore decided to ask the students if they wanted to spend some of their spare time working on the main output of the project together—a project homepage—and it turned out that many did. Between March and June we met almost every second Friday afternoon. We picked up the students from school, accompanied them to our office, prepared lunch for them and worked in small groups on various aspects of the homepage (structure, design, pictures, film, etc.). About ten students came to the first meetings, after which numbers fell. The motivations and enthusiasm for working together differed, but three of them attended every meeting, seemed to enjoy our work together and in the end regarded the homepage as "theirs". [25]

From the very beginning of our research projects we entered into negotiations with the teacher and the students. The first deeper step "into the field" was a meeting with the teacher in a café, where she told us about her school class and school conventions and where we discussed how and when we could come to school and work with the students. Ms Schmidt5) did not want us to come in that week but rather a week later and agreed that we could come every other week in the afternoon lesson on fine arts. We did not regard this as being very often, as it was less that we had expected and promised in the project proposal. Even though the teacher had seen the proposal in advance and had not objected to the idea, it turned out that she had remembered our first discussions and interpreted the proposal differently. She had thought that the project primarily meant trips and excursions to museums or other institutions where we would support her activities. Accordingly, we did not do any extra project days in the first semester and only one in the second. Occasionally, afternoon sessions were skipped (e.g. when holidays were too close to the date, when the teacher was sick or on training). In the following one and a half years there were such negotiations about time with the students and between (some of the) researchers and the teacher. Whenever we wanted to change our timetable with the students we feared that Ms Schmidt might disagree, and whenever she wanted to change the arrangement she had to face discussions with us, the trained researchers. In the second year we changed the afternoon arrangement into a more intense setting: we had an opening session in October then a project week in December and a session for presentations before Christmas. What we only later realised was that we actually had been given quite a lot of time with the students compared to similar projects in other schools. So we basically started with misunderstandings and mutual disappointments about the intensity of the project and our collaboration. We and the teacher only gradually came to understand how intense our collaboration would (nevertheless) be and how difficult it was for Ms Schmidt to spare time for the project. A more intense collaboration would have meant attending our sometimes very long and exhaustive meetings, discussing our sessions in class in more detail, reading and discussing (scientific) texts, etc. In short, she would have had to spend a lot of her spare time on our project. Her concern is reminiscent of what both James F. BAUMANN (1996) and Marilyn COCHRAN-SMITH and Susan L. LYTLE (1992) describe for teacher research: "time" is a crucial issue in many teachers' working lives. They never seem to have enough time to manage all the organisational and preparatory tasks besides their time in the classroom. Very similar to what COCHRAN-SMITH and LYTLE describe in their paper, Ms Schmidt said that there is never enough time to consult with her colleagues, to properly exchange estimations or experiences (about students, subjects, school matters, etc.) beyond small talk. She never asked for any kind of compensation money (which had been calculated within our budget), but she would have liked her efforts to be implemented and recognised within in her workplace description, her profession. She would have needed to be given time off from teaching in order to do research. Unfortunately, we were not in the position to negotiate this with school (or ministerial) bureaucracy, nor was this an element of the ministerial research programme. So we tried to minimise her workload, but at the cost of a much lower participation rate than we had with most of the students. [26]

In summary, we negotiated the organisational and legal framework of our work in school with the teacher (e.g. responsibility issues, forms the students needed to have signed, school regulations we had to respect etc.). We also negotiated our understanding of class and migration issues, of what useful research is and mutual approval. The most crucial issue that shaped and partly hampered our common research project was time and the lack of it. [27]

Time was also an important subject of negotiation with the students—but here it was not the amount of time we spent with them, but rather how we used the time we had together. They were at school anyway and instead of an art lesson, they had a "research lesson". They were interested in using the time they had to spend at school as enjoyably and interestingly as possible. They quickly realised that our time together was significantly different from "ordinary" school lessons: we were at least two (sometimes up to five) young people, rather informal, listening to all their ideas, mostly without judging or correcting their remarks or behaviour. Besides this, we were not so strict on what we were going to do together. Our "teaching"6) designs were rather flexible and it was possible to convince us to (slightly) depart from our plans. [28]

One example of this type of negotiation happened in the research group on chatting on the Internet. The research question was decided to be "Why do pupils chat?" The group's second session was dedicated to showing related studies to the students, getting inspiration about research methods and coming to a decision for a certain method to investigate the chosen question. In the beginning the trained researchers asked the girls about the last session (four weeks previously, due to holidays), in which social-science methods were discussed theoretically and illustrated as a toolbox. One researcher reported in her observation note: "She can remember a suitcase on the poster, but the message about the 'tools', the methodological tools, was not appreciated. None of the girls remembers 'methods'."7) [29]

The researchers were slightly disappointed, but tried to summarise the last session themselves and continued with the examples from literature. The following discussion was dominated by a lot of personal stories and experiences of which chat rooms the girls liked, what happens in chat sessions, who they chat with etc. Looking at two master theses and a dissertation on the topic of chatting impressed them, but the most interesting part was a printed version of a chat observation note given in the dissertation. This immediately provoked new stories of how it feels when someone "writes this to you". [30]

From the very start of the research lesson the researcher in charge was asked, "Can we go to the computer room?"8) The first explicit refusal was accepted ("No, today we focus on methods. We go there next time"). In the course of the class each girl asked this question at least once, strategies of persuasion were tried ("But, please, let's go today, because Güle is leaving school next week. She will not be able to go to the computer room with us next time!"), and arguments were given ("We will answer the research question in the chat room: We simply post this question and then a lot of students will answer the question. Please, let's go to the computer room!"). In the end the researcher tried to make the best of it: "Ok, we will go to the computer room and print out chat protocols." She intended to check whether the chat protocols might be useful data for this research question. [31]

This example illustrates that the interests of the students lay in having a good time at school or more precisely in chatting with colleagues and friends, while the researcher's interests were in collecting good data and continuing with the research process that had started in the previous session. The compromise was that the students were allowed to chat, but simultaneously had to collect data. Similar compromises were reached in other research groups: talking about love and friendship was combined with analysing emotions and relations in more general terms; playing football and admiring certain football clubs and stars was combined with research on the clubs and interviewing, for example, an A-league-player, fans and a social scientist concerned with football etc. [32]

We can see here that the girls were skilful negotiators: they tried to argue with personal preferences, with friendship and group dynamics and last, but not least within a research logic. They had seen that chat protocols can serve as proper data in the dissertation and argued that their group could do the same. They could use chatting directly as a source of data. This showed that they had understood more than they had seemed to in the first part of the session, where no one could remember the methods we had discussed two weeks before and no one remembered what methods were all about. While theoretically they did not remember or at least could not reproduce what methods were and how they were used, they practically integrated this knowledge into their negotiations about the computer room. [33]

Another girls' group enacted a similarly confident handling of research methods a few weeks later. The topic of this group was "love" (or "love and friendship" as the group proceeded) and the focus was on "Places for love at school". Karin SCHNEIDER, the researcher, had suggested doing participant observation at the school, but interviews with other students were also an option that was discussed. As the day of field work approached, two girls in the group, who had started to distance themselves from the issue of "love" and the girl who had suggested this topic, and chose their own priorities:

"Milena insisted (again) that this is hers and Azra's project, but that Susanne does not belong to them. I say that Susanne had interesting contributions with the posters she wanted to write, etc. ... Milena says that she can do this, but not the observation, which is hers and Azra's project."9) [34]

In this discussion the girls used social scientific methods for boundary work. Boundary drawing between these girls was an important activity in this group: Milena and Azra felt that Susanne had been too dominant in talking them into her own interest (love) and that they were actually not interested in it. Remarkably, they also used research methods to these ends. What these girls negotiated here was friendship, emotional boundaries and ethical belonging, but they discussed them (among others things) by using the research topic and sociological methods. They thereby showed that they knew how to use the repertoire offered by the researcher to position themselves. Besides this, they also performed a handling of methods that is not unfamiliar in the social sciences. Emotional discussions about the validity of methods are widely known, and boundary work through methods and methodology is done within institutes, journals, handbooks etc. With regard to the German Sociological Association, for example, Reinhold SACKMANN (2007) mentions that two sections on methodology were introduced that "battle against each other" with arguments.10) Without knowing about such discussions and disputes within professional sociology, the girls in this research group used methods to distinguish themselves from the third girl over who could do posters or interviews. When Susanne returned to the research group about a month later, she in fact wrote an interview-essay all by herself which she called "interview with myself", but was not allowed to interpret the notes of the observation carried out by the others. [35]

After having decided on the method, Karin, Milena and Azra decided on the site of observation: they wanted to observe their classmates during a break. Hence the researcher discussed observations and research focus with the girls. Karin (not a trained social scientist, but a historian and a professional communicator of art for children) remarked in her observation note that she would have felt slightly insecure if she had really told the girls enough about participant observation. She told them, among other things, about the importance of making notes and that everyone on the team should make their own observations. When she came to school to meet the students to do participant observation, they appeared ready with pens and paper and a few changes to the design. At the beginning of the break, i.e. at the very last minute, the girls had decided to move to another floor of the school building, to write the observation note together and—something the researcher did not know beforehand—to do covert observation. The girls argued that they were afraid that observing their own classmates—especially if they were to do it openly—would not work. And in fact their hypothesis that open observation would give rise to a lot of nonsense by some students to make fun of them and to subvert observation turned out to be correct. Karin remained in their own floor and did open observation, and a large part of her observation note was about a few boys coming up to her and asking what she was doing and trying to see if she would really write down all their remarks and swearwords. At the same time, the girls were in another part of the building, observing what their colleagues were doing, went to the bathroom to write notes on it, returned to their scene, went to the bathroom again etc. At the end of the break they gave their notes to the researcher.11)

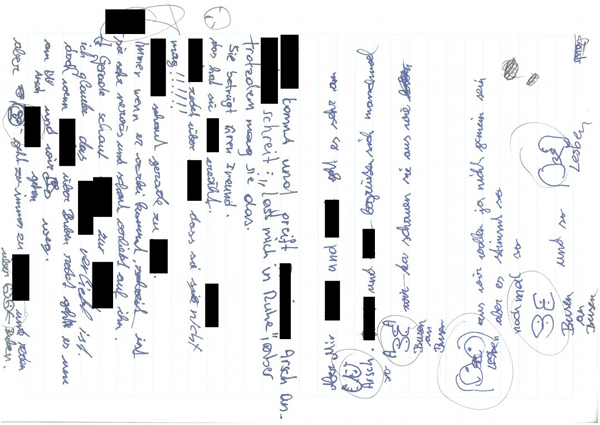

Figure 1: Observation note by Milena and Azra [36]

The researcher's observation note looked more familiar to a sociologist's eyes:

"After a short time some boys, who are big and look quite 'cool', come over and want to know what I am doing here. I try to explain to them that we are doing a research project about their school and the break (lying a bit) and that I am writing down all I can see and that two girls are doing the same at the moment; but this doesn't interest the boys at all. Instead they are very interested in what I am writing down and if I really write down everything. They ask me what they have to do to appear in this observation note. A small boy with a short haircut tells me, 'Write: I love shaved vaginas'. I am writing it down and both boys check if I really wrote it down. 'Where does it say vagina?' 'Here' I say, pointing to the word."12) [37]

The next time they met, the two girls and the researcher had their observation notes and started comparing them. Karin's consisted of an unbelievable amount of writing, as the two girls told her, maybe a bit surprised. On the other hand, there was Milena and Azra's observation note, which was framed and supplemented by various drawings, which seemed related to the scenes observed. The researcher saw a lot of observations written in their note, but, also a lot of names, presumptions, value judgements etc. These were clearly things Milena and Azra seemed to have known in advance, things they had assumed, but not observed. So the two girls did something that most of us reading this probably learned very early in their lessons on empirical social science research—one should try to avoid (making analytical) summaries and interpretations (especially without marking them as such) when writing observation notes (e.g. BECKER, 1998, pp.76-83). However, Karin was not disappointed; she used these differences for further analyses. The first step she initiated was a transcript of the girls' observation note in the computer. Their transcript gave a more abstract picture, one that could be worked with without "destroying" the comments and paintings. Then she suggested systematically marking different types of comment in this observation note in different colours. They marked three different categories: theses, knowledge and observations. The two girls asked her to read some more passages from her observation note, which she did. Hearing Karin's different experiences, Milena started thinking about what might change if she were to observe another school, where she would be a complete stranger. They decided to create a poster on this topic. When we listen to the audiotape of this session, we hear that all three people involved contributed words and sentences to this poster; Milena was the one who wrote them down:

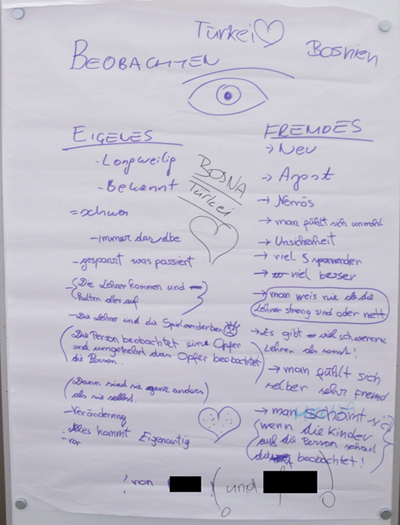

Figure 2: Observation poster [38]

They split the poster into two columns and discussed in a kind of "what if" mode what might change if one were observing: own/strange places/people, etc.:

|

Own |

Strange |

|

boring known = difficult always the same what will happen? (teachers come and slow down everything) teachers destroy the game the person observes a victim and vice versa, the victim observes the person Then everyone acts differently to usual (not themselves) Change Everything seems strange |

new Angst (fear) nervous one feels strange insecurity much more exciting much better one never knows if teachers are strict or friendly There are many more difficult teachers than usual one feels very strange one is embarrassed (if the children look at the observer) |

Table 1: Translated and transcribed observation poster [39]

This example shows that the girls are quite competent with regard to social-science methods: In the process of data collection it became clear that they know a lot about their colleagues and the school setting. They were able to adapt the chosen method according to this context. They decided for a short-term change in procedure in order to be able to collect more interesting data. A comparison with the researcher's observation note shows that their hypothesis was right and their adaptations were very useful. They handled research methods flexibly and confidently. [40]

Furthermore, the poster they created on observation covers many of the issues found in methodological textbooks: alienation, distant approach, going native, objectification etc. Not all of this is so explicit, and most of it is not in sociological terms, but the issues are covered. Milena added the sentence: "The person observes a victim and vice versa, the victim observes the person." Shortly afterwards she remarks: "Oh, now I wrote 'victim'—well, whatever, it is victim now."13) [41]

Before discussing their observation together, Milena had observed insulting situations ("Hans comes and touches Tamara's butt" or "Ivan, who is in class 2c, fouled a boy, who is now lying on the floor"), and the word "victim" seems appropriate in such a context. Interestingly, she seems to draw an analogy between these boys or what they did and her own task of observing these insults. So she articulates a feeling that observation is not an innocent practice: she indicates a process of objectification and subjugation, maybe even of complicity. [42]

This corresponds with discussions in the academic fields of (feminist) art history and film theory, post-colonial theory or social sciences, where an objectifying gaze is a widely discussed issue. Feminist and other cultural theorists mostly refer to Jacques LACAN (1987 [1964]) and analyse how women become objects of the "male gaze" in film and art. Christiane RIEKE (1998) for example writes that the gaze at another person always implies aspects of power: While the person who is looked at becomes objectified, the person who gazes is in the position of a powerful subject or positions him/herself as such. Accordingly, aspects of power and dominance are implied in a gaze. Feminist theorists speak of a "male gaze" that is dominant in our society (MULVEY, 1975), post-colonial theorists of an "imperial gaze" by Western metropoles on large parts of the non-Western world (CONNELL, 2007). We assume that it is no coincidence that theorising about the gaze became most important in contexts in which aspects of power, subordination and violence have been dealt with, such as in feminist and post-colonial theory. [43]

Social scientists have also discussed the objectifying aspect of observation or social research more generally. Objectification of research participants and "othering" (a process of distancing oneself from others which includes objectification and devaluation) is an issue that is repeatedly discussed in feminist methodological debates. These debates are motivated by finding ways of minimising othering and objectification in feminist research (e.g. COLLINS, 1998; WILKINSON & KITZINGER, 1996; FINE, 1994). [44]

Without knowing about these discussions, Milena had felt and realised that observation and objectification in the process of research are powerful instruments that can even harm the observed. She did not elaborate this in more detail, but she indicates this by using a term that is very expressive (victim). She continues that the observed have another kind of power, they can "look back"—an issue that is also well elaborated in academic discussions. Jean-Paul SARTRE (1995 [1943]) or WALDENFELS (2000) have written on the power of the other who is looking at us. Feminist theorists have analysed the threatening effect of a female gaze (e.g. in film and art production) and the elimination of a female gaze in these genres (e.g. DOANE, 1994). [45]

As Milena implies with her word choice, those who are observed and can look back are nevertheless not as powerful as those who have the power to gaze, notice and interpret. Their attempts to "look back" can be ignored or eliminated, they nevertheless become objectified or the "victims" in processes of research. [46]

So in negotiating friendship, methods and procedures these girls were showing an embedded understanding of social research, including knowledge about structural effects, relations of power inscribed in research processes, problematic aspects of going native etc., which surprised us. [47]

Another interesting point in this example of negotiation is that this handling of the different observation notes produced a successful communication and common methodological analysis. Using STAR and GRIESEMER's (1989) concept of the boundary object we may better understand what happened here. Their concept was developed in order to understand communication and collaboration in knowledge production between different "social worlds". Boundary objects are described as "those scientific objects, which both inhabit several intersecting social worlds [...] and satisfy the informal requirements of each of them" (p.393) They "come to form a common boundary between worlds by inhabiting them both simultaneously" (p.412). Accordingly, boundary objects are often internally heterogeneous, "simultaneously concrete and abstract, specific and general, conventionalised and customised" (p.408). They argue that due to translations, standardised methods and boundary objects, very different people and social worlds (scientists, amateur collectors, trappers, university administration) could work together and succeed in establishing a museum and research site. [48]

STAR and GRIESEMER defined four different types of boundary objects (repositories, ideal types, coincident boundaries and standardised forms) stressing that these are analytical distinctions for actually more heterogeneous systems of boundary objects. Altogether the model is slightly more complex, but what is of interest here is their observation that these objects never had the same meanings for all the different people involved. Nevertheless, they were able to cooperate successfully: boundary objects formed spaces that everyone could somehow identify or work with. Without having a common understanding of their meanings or of the expectation or goal of the whole enterprise, they established an innovative museum collection together. [49]

This is similar to the process in our research group. Even though none of the people involved changed their habits in writing observation notes, and the girls' interests and foci in observing their classmates differed from the researcher's, they nevertheless had interesting discussions and analysis sessions together and produced a common "product" of this methodological analysis. [50]

One idea accompanying our project week in the second year of research was to leave the school and change our working environment. This was based on impressions from working with the students outside school in the first year. Our initiative was also strongly supported by the teacher, who told us that such outings are relatively rare for the students, among other things because of their relatively high cost. One research group (on football) was therefore planned to work in our office (a setting that had proved to be inspiring the year before) and additional rooms were rented for the other groups. One of these was a privately organised meeting room for children in the city centre. The place consisted of a main room with big windows, some couches and mats, and lot of space and toys to play for mainly younger children. A political youth group, that stores e.g. Marxist literature, stickers, etc. in the shelves, also uses this place. There is a second, smaller room at the back, which is now mainly used as a kitchen. The researchers had arranged with the owners that the toys would be hidden when the research group was there. Nevertheless, when two girls, five boys and two researchers arrived on the first morning, a big box with plastic balls stood in the middle of the room and immediately caught the boys' attention. The two girls were both a year older than the boys and were not interested. Nevertheless they soon became targets of the boys, who threw the plastic balls at them and at each other. After some discussion and intervention the researchers managed to stop them and establish some kind of working process. They took the balls into the small room and made a deal with the boys: if they would concentrate on their shared work, they would have enough time for a longer break afterwards, where they would be allowed to play with the plastic balls again. The boys agreed and for approximately two hours all of them focused on working together. However, at the end of the first session the boys had finished their task faster the girls, who had started later and took their work very seriously. Hence the boys became bored, the room too small and the plastic balls more and more interesting. It became very difficult for the researchers to keep the working environment stable for the two girls. After a while the researchers gave up and decided on a break. They hoped that after running around for a while, the boys would be more focused again, and that they could continue their work. But it turned out differently: after a long break of about half an hour their various attempts at talking, advising, disciplining, pleading and begging were not listened to and they were not able to start work again. The fun with throwing balls at each and everyone appeared nearly unstoppable and the girls, who wanted to start their work again, became the preferred targets. The researchers felt lost and actually quite helpless. They decided to split the group into a girls' and a boys' group, working in separate rooms. In these smaller groups the researchers slowly managed to establish working atmosphere again—but it was difficult to get the girls' attention back to research issues and it was hardly possible to work at all in the boys' group. One researcher and the two girls made some progress and designed a questionnaire for the day after. Nevertheless, the researchers had the feeling that the girls were disappointed that they had put them in this situation, where they were attacked by the boys beyond the limits of having a bit of fun. Both of the girls—and two boys—did not come the next day and never carried out the interviews themselves. Even though these girls were known for playing truant a lot, the researchers felt that this time their absence was at least partly connected to their failure to provide a tolerable (working) atmosphere. [51]

This is an example of a situation in which negotiations did not work out the way the researchers had hoped and planned. The first deal with the boys had worked (their attention in the session in return for having fun during break time). On the second occasion, however, they could not resist the temptation of extending their fun and break time to a point that was no fun for the girls and the researchers any more. This example hints at two points: Firstly, the researchers underestimated the necessity to discipline a group of students of this age. In this situation they were not primarily called upon to be researchers, but rather to be teachers, or at least adults taking responsibility for a group of young students. They had to be active and involved to an extent, they did not feel prepared for. As social scientists and researchers they are primarily trained to observe, to interpret and to analyse, but they do not have appropriate training for intervention and disciplining. This was one of the situations where researchers in our team felt that the expectations they faced and roles they had in this project were manifold. [52]

Secondly, we can see here the importance of structures, settings and artefacts, which the researchers had misjudged. Recognising the interactions between actions and structure—as subtle as they might be—seems to be significant in planning and conducting such a project. In this case the room's architecture, the objects and materials in it were not appropriate to the practices the researchers had planned to realise. A room that is regularly inhabited by smaller children (partly small-size furniture, bright colours on the walls, etc.) and the balls that were in sight were materials that made it comparably harder to establish a concentrated working environment than the materials of "proper offices", such as computers, printers, book shelves etc. in other research groups. Accordingly, one of our colleagues who worked with some of the boys who were said to be "troublemakers" was surprised how concentrated and "well-behaved" they were in our office. She started calling our office and its equipment a "disciplining machine". In the event described above, the research group had left the school setting with all its structuring (and disciplining) elements (school classes, teachers, benches, time frame, school bell etc.), but it had not come to a research environment, either: no desks, computers, printers, copy machines, files, etc. The materials in this room probably resembled a place for fun and leisure time to such a great extent that the students' associations of being at a playground strongly interfered with the researchers' efforts to concentrate and do research together. [53]

As we had originally planned to spend another semester at school and some of the students were sad that they would not be doing research any more, we offered voluntary working sessions to jointly produce the project's homepage. We had thought a great deal about possibilities of publishing the project and its different results and materials and finally decided to create a homepage. This seemed to be the best medium to present our diverse and heterogeneous materials (audio, video, text, drawings, posters, photos etc.) and to provide the easiest access to all the different readers (students, teachers, educators, researchers). Additionally, the creation process of a homepage appeared promising to us, because the Internet is the students' closest, most used medium. We planned to use web 2.0 programming, as it supported interactive and collaborative usage. [54]

Not all the students came to our first editorial meeting to present our ideas for a project-homepage and to ask for their cooperation, but it was more than we had hoped for. We started with different working steps organised as separate working groups, e.g. sorting and selecting existing materials (presentations, posters, photos, explanatory YouTube videos etc.) or creating and deciding on important design elements. Soon it became clear that the visions and wishes of the students were shaped by the site designs they visit every day. In our impression they had a strong bias towards YouTube and web 2.0 sites, mostly presenting pop-musicians (some US or UK based, some from Turkey), or organising social networks. These sites are often very colourful, consist of different media (video, audio) and present themselves in a rather messy way—at least to the untrained eye. We discussed these elements a lot and asked for technical expertise to estimate our chances of implementation. These discussions strengthened the decision for the web 2.0 formats, but at the same time fostered the researchers' worries about aiming at a scientific and serious appearance of such a homepage (minimal designs, discreet use of colour etc.). How and by whom would it be read? At this point our different interests surfaced clearly. The students oriented themselves towards their preferences and peers, the researchers did the same—but the preferences and peers differed. Furthermore, the researchers were interested in engaging the teacher again, to hear her opinion and impressions, experiences and professional evaluation of our collaborative attempts. The conclusion was to split the homepage after a shared front-page into the more colourful presentation of the students' projects and the more scientific (and restraint) presentations and documentations of the researchers' texts. So our final product was not a "joint" presentation in a narrow sense, but a collectively produced structure that was the best solution for all participating (co-)researchers. This seemed the best way to respect all the different orientations and goals related to differing interests and to different imagined groups of readers. [55]

Another negotiation in the process of creating the homepage suggests aspects of understanding and change in the course of our project. One piece of material we, the trained researchers, wanted to present on the homepage was a radio feature that four girls had created for the "students' radio"—a programme funded by the Austrian Ministry for Education, Arts and Culture (Bundesministerium für Unterricht, Kunst und Kultur [BMUKK])—about eight months earlier. When we asked these girls if we could present this as an audio stream on the homepage, they vehemently forbade us from doing so. During the following discussion the girls argued that they could not stand the sound of their own voices, an argument we had already heard before. Additionally, the pupils argued that at that time they had not known what working scientifically meant. In the meantime they had learned to work on research questions, research literature, carry out interviews, compare and analyse interviews etc. In this respect, they argued, this feature had been made before they understood what doing scientific research meant and therefore they could not allow us to publish this kind of preliminary work. Hence we lost interesting material for the presentation, but we were happy about this interesting discussion and convinced by their arguments. [56]

With regard to the new working arrangement in the students' leisure time, we were dealing about attendance, attention, collaboration and fun. We negotiated design, structure and contents of the homepage. Another interesting point was our discussion of the concept of "research". Obviously the students' understanding had changed in the course of our project. [57]

Coming back to the concept of the boundary object of STAR and GRIESEMER (1989), we might say that "research" served as a boundary object in our project, it was a type of "coincident boundaries" (p.410), a term that seems crucial in the project, which everyone used and could somehow identify with, but that meant very different things for different people involved. [58]

The term "research" was part of the title of our project and part of the description of the ministerial programme. It is rather prestigious and it was used and useful for many of us, even though we all understood different things by it: The director of the school found it useful to have a "research project" carried out in his school. The school could hope for enhanced prestige and therefore (implicitly) for more or better students. The teacher tried to use the project to argue for resources for herself (lessons she did not have to teach in other classes when we had project days) or for the class—in the name of research. Altogether, she was very ambivalent about such projects. She used the term research to describe the project, but was at the same time sceptical about her participation in a ministerial programme that is actually planned for 16-18 year old high school students. Her understanding of research was close to a positivist paradigm of collecting facts and finding out truth about the world we live in, but it changed in the course of our project. We, the trained researchers, used the term to describe our project, to describe our profession in general and tried to gain acceptance of our work in academic as well as school contexts by using the term research.14) Coming from an interpretative research paradigm, we were interested in the construction of knowledge and scientific practices by the students. All these definitions developed and changed in the course of our common undertaking. While some of the trained researchers had started with the idea of doing research projects together that we might be able to present at conferences together with the students (e.g. finding out something "new" about love, migration, vocation, etc. in the world of teenagers), we began to define research rather as discussing and analysing our own experiences and trying to formulate hypotheses (more on this in Section 6). At the beginning the students were curious. In our first encounters they associated research rather with natural sciences than with social sciences, but quickly realised that social research might mean researching ourselves in our environments and called it Uns-Forschung ["us-research"]. In later stages of the project they saw research as something that was "hard", where you have to think a lot, that does not simply answer questions, but rather makes issues more complex. They also experienced it as something that is more fun than ordinary school lessons. And as we described above, at the end of the project they distanced themselves from earlier stages of our research process, where they "had not fully understood" what research can be. [59]

So what we can see here is that the understandings and usages of the term research differed between the different actors of our project. We would like to stress and add to STAR and GRIESEMER (1989) that our understandings of the term research were not stable, but changed. And it was exactly these developments and changes that made it a useful boundary object: a term that was object of discussions and negotiations, something that we repeatedly had to think about and refine with the students and the teacher. The term (and concept) research was therefore a very useful tool in our joint work, even though or maybe because the different protagonists never really agreed on the nature of its importance or meaning. [60]

As our homepage production came slowly to an end due to the summer vacation, the three most active students in our afternoon sessions launched salary claims—rather surprisingly to us. They had decided that they did not want to do this work for free, that they wanted to have presents (mobile phones or laptops) from us to "pay" them for their work. They argued that their work was essential for our project, that we could not have done participatory research without them, that their contributions were valuable and that we, the trained researchers, also had fun and nevertheless got paid for our jobs, so why should they not be paid for their fun? We told them that we had paid for their expenses and for food and drinks, that they had used our resources for their own issues, too (chatting with friends, watching YouTube-videos, etc. in between working sessions), that they would get a certificate, as we had regarded them as volunteers. We had not included this asset in our (very small) budget; we had only part-time contracts ourselves and were not paid for all of our work either. The teacher was strongly against any remuneration for the students—and legally they were perceived as children, so we were not allowed to "pay" children for their work. There were a number of reasons why we could not pay our co-researchers, but nevertheless, we had the impression that they had a point: if their work was so important for us, why did we take it for granted that they would do it for free? These last negotiations about financial issues, about salaries, showed (again) that they had understood a lot about the world of research. They had comprehended that their work and contributions were essential for us, for our work and therefore also for our income. They had understood that our jobs (as underpaid or precarious as they might be compared to regular positions at university) meant that we were paid for something that we enjoy doing (unlike the jobs of some of their parents or siblings) and accordingly that being paid for something that is fun is not a contradiction. And they reminded us of the fact that we had not taken them as seriously as we should have: we should have been more explicit about the position of volunteers, about the benefits they can expect from us and about the limits of our equality with regard to finance. [61]

They argued not only for finance and salaries, but also their importance in the project and our recognition of their work. Furthermore, they posed the question of what sociology as a vocation might be in this context. They had observed our work very well. They had realised that sociological work is not paid too well—at least for junior sociologists: "Researchers do not earn much money, do they?" was a question they had asked the teacher quite early in our common research process. They must have guessed this from our appearance and behaviour, as they had never directed such questions at us. Besides this, they noticed that this type of work is a regular occupation for the trained researchers—even though it does appear as "fun" to them and they asked questions like "Is this really work, there are only computers here?" or "Do you live here too?" when they first saw our office in the first year. And they had realised that they are important in the project and that our work in this project depends on them: "You would not be able to pay for your apartment without us, you would live under the bridge, and you, too, and you, too", was one boy's laughing remark, when he told us, why he wanted a laptop. [62]

Interestingly, the students had again pointed at a crucial moment in social research: negotiations about salaries are always delicate issues, but in the (social) sciences they have become even more so in the last years. As contract research, short-term-contracts, externally funded projects based at universities etc. are on the rise, the literature on working conditions in the (social) sciences and their effects is increasing (e.g. GOODE, 2006; FELT, 2009; PERNICKA, LASOFSKY-BLAHUT, KOFRANEK & REICHEL, 2010). [63]

The empirical examples given above show that a main part of our collective work was to negotiate important issues of social research with the different participants in our project. Negotiations were part of every interaction in the field and they covered all aspects of a research process: framework, time, data, methods, space, attention, dedication and financial matters. We negotiated with the teacher, with the students and amongst ourselves. [64]

The examples also show that the children developed ideas and ways of doing research that in many ways resemble professional research. They understood many of the principles of everyday research life and used them in their negotiations. They argued with data collection, they drew boundaries through research methods, they analysed the impact of certain methods, they challenged our competence, questioned previous research and negotiated remuneration. In many of these negotiation processes the trained researchers were surprised, stunned, sometimes overstrained, sometimes happy. Only in the process of analyses did we realise how much the students had understood of research life—most of these things, without our explicit "teaching". In contrast, even when they seemed not to remember the things we had taught them before, they used the tools we had given them. Their knowledge about social sciences and social-science research processes changed and developed over the course of the project and seems to be more implicit and tacit (POLANYI, 1958) than explicit. They probably did not learn much factual knowledge, but they obtained new skills. They learned them by doing. And even though hardly any of them will ever become social scientists themselves, they nevertheless learned a lot of things about how to analyse their own environment and their own assumptions, and they learned things about (precarious) working life in a middle-class job.15) [65]

Another (maybe less optimistic) reading of these examples shows that we, the trained researchers, repeatedly struggled with different expectations and the different roles and positions ascribed to us in this research process. All kinds of social research rely on negotiations to some extent, and all kinds of social research have to be careful about field entry, (personal) involvement in the field and field exit. Even though literature on ethnography and other types of qualitative research discusses negotiations and field involvement in great depth (e.g. LÜDERS, 2004; WOLFF, 2004; HAMMERSLEY & ATKINSON, 1995; LAINE, 2000), this kind of research differs from PAR in some respects. We do not wish to suggest that PAR would be substantially different from other types of qualitative research, but we think that there are gradual differences between different types of research and between the amount of personal and professional involvement in the production of data. What the researchers in our project did at school differed from ethnography as it is described in textbooks (e.g. FLICK, von KARDORFF & STEINKE, 2004) and as we had experienced it in previous research projects. In this research process neither a "distanced approach" nor even a possibility to concentrate on observing was possible. Martin HAMMERSLEY and Paul ATKINSON for example write:

"In its most characteristic form it [ethnography] involves the ethnographer participating, overtly or covertly, in people's daily lives for an extended period of time, watching what happens, listening to what is said, asking questions—in fact, collecting whatever data are available to throw light on issues that are the focus of the research" (1995, p.1). [66]

In our case watching, listening and asking seemed hard as we were constantly expected to show, speak and tell stories: We had to "teach", to care for the ability to work with the research groups, to take responsibility for the students when they were with us and to deal with simultaneous requests and different kinds of "disturbances" (by violent students, by angry parents, by teachers from neighbouring classes etc.). This means that we constantly intervened and structured what we were simultaneously trying to observe. Later on, when we got home, we wrote memos, memorising situations of what we did and how the students reacted to our actions and how we reacted to their actions. Our memos differed from typical observation notes, they were rather personal memories and reflections. They resembled entries in a field diary. At the level of data production this was only problematic if our audiotapes were ruined (which happened a few times; the quality was also sometimes very poor). On the level of our own ambitions as social researchers, however, this was more difficult. [67]

Our positions in the field oscillated between being researchers, teachers, mediators, social education workers, older friends or role models, or several of these at once. We realised that we (as sociologists) were only trained for a few of them. David E. WONG (1995a, 1995b) and Suzanne M. WILSON (1995) had a discussion on the issue of "role conflicts" of teacher/ researchers in the Journal "Educational Researcher" in 1995, which was commented on by James F. BAUMANN (1996) a year later. While WONG argues that the roles of teacher and researcher being carried out simultaneously by the same person results in a lot of difficulties and conflicts, which might hinder either research or teaching, WILSON says that she does not experience "tensions", but aims for synergies between these activities. BAUMANN agrees with WONG that there are tensions involved in teacher research, but not in "conduct or purpose" (agreeing with WILSON in this point) but in "time and task" (BAUMANN, 1996, p.30). He analyses his own research as a teacher, saying that there was often too little time for research tasks. Interestingly, before he concludes that he did not face any tension regarding conduct and purpose, he states that his "first principle" is "primacy of teaching and students", which means that "research can never interfere with or detract from a teacher's primary responsibility to help students learn and grow." (p.30) So in fact he eliminated any possible interference between teaching and researching by setting strict priorities: teaching is more important than research. As reasonable as this priority is, it nevertheless shows that he did feel contradictions between these two tasks, otherwise such a priority would not have been necessary. [68]

We come from different positions than WONG, WILSON and BAUMANN. We are trained researchers and some researchers in the team had experience of working with children and students, but nobody had been a professional schoolteacher before. So as similar to teacher research as our experiences sometimes might seem, we were rather "researchers sometimes acting as teachers" than teacher researchers. Nevertheless, our position in the question on the conflict or compatibility between teaching and researching resembles BAUMANN's in some respects. In contrast to WONG, we would not want to separate "theory" from "practice", nor "research" from "action". Even though we do not support these dichotomies, we agree with him that differing expectations of the fields (as well as of ourselves) and heterogeneous tasks, which we felt had to be fulfilled at the same time, were often very difficult for us. In contrast to WILSON (and partly BAUMANN), we do not think that it is so easy to combine these demands with regard to time, tasks and conduct. Rather we want to argue for more discussion around these issues, for an acknowledgement and for careful reflection and analysis of differing demands and expectations (by different co-researchers and by the researchers themselves), for ideas of how to work with heterogeneity and contradictions. [69]