Volume 14, No. 1, Art. 7 – January 2013

Designing a Tool for History Textbook Analysis

Katalin Morgan & Elizabeth Henning

Abstract: This article describes the process by which a five-dimensional tool for history textbook analysis was conceptualized and developed in three stages. The first stage consisted of a grounded theory approach to code the content of the sampled chapters of the books inductively. After that the findings from this coding process were combined with principles of text analysis as derived from the literature, specifically focusing on the notion of semiotic mediation as theorized by Lev VYGOTSKY. We explain how we then entered the third stage of the development of the tool, comprising five dimensions. Towards the end of the article we show how the tool could be adapted to serve other disciplines as well. The argument we forward in the article is for systematic and well theorized tools with which to investigate textbooks as semiotic mediators in education. By implication, textbook authors can also use these as guidelines.

Key words: cultural historical theory; history textbook analysis; analytical dimensions; grounded theory methodology; inductive coding; deductive coding

Table of Contents

1. Introduction: Searching for Guidelines

2. The Three Stages of the Tool Design Process

2.1 A grounded theory approach to (open) data coding

2.2 From grounded theory back to the literature: Towards finding a workable heuristic frame

2.3 Towards the principles for the five-dimension tool

2.3.1 The dimensions

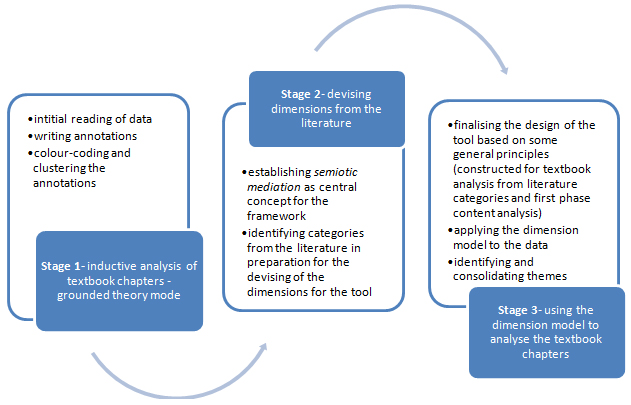

2.3.1.1 Dimension A: Making own/personal historical knowledge

2.3.1.2 Dimension B: Learning empathy

2.3.1.3 Dimension C: Positioning a textual community

2.3.1.4 Dimension D: Fashioning stories

2.3.1.5 Dimension E: Orientating the reader

3. Application of the Tool to Other Subjects

4. Some Limitations

5. Conclusion: The Need for a Systematic Tool for Analysis

1. Introduction: Searching for Guidelines

This article describes the process by which the design of a tool for analysis of textbooks came about. The impetus for devising such a tool was the clear message in the literature that "we do not yet have instruments and processes at hand for the dimensioning, categorization and evaluations of textbook research" (WEINBRENNER, 1992, p.34; our translation). What is available in more recent literature is some practical advice for textbook reviewers (see PINGEL, 2010) or a list of possible questions to ask when examining textbooks (see NOGOVA & HUTTOVA, 2006), as well as descriptions of the type of analysis possible when using different theoretical lenses (see NICHOLLS, 2005). How exactly the content of textbooks based on these analyses is to be evaluated, or how the criteria put forward in these lists are to be assessed or "measured" is not clear. It points to the problem that the methodological principles that underpin textbook research are not well developed and the area remains under-theorized (FOSTER & CRAWFORD, 2006, p.11). [1]

According to the seminal work done by PINGEL (2010) the main distinction in textbook analysis is between didactic and content analysis; the former being concerned with the pedagogy implied by the text, whereas the latter is concerned with examining the content of the text itself (PINGEL, 2010 p.31). PINGEL (p.72) provides a comprehensive list of possible questions and approaches, e.g. quantitative and qualitative, inductive and deductive, including some examples of how history text analysis could be conducted. He describes hermeneutic, contingency and discourse analyses, among others. However, even though useful, his guide offers more in the way of overall approaches and epistemologies to choose from, rather than a single example of a how a theoretically-founded tool for analyzing textbooks could be put to practice. Hence our aim was to consider the various theoretical strands available for the design of an explicit tool, including those offered about the discipline of history itself, such as the work on assessing historical thinking by SEIXAS (2006). We also aimed to design a single tool that would be comprehensive, holistic, discipline-specific and practically usable. It would be a tool that does not try to be everything to everyone, but a particular example of how one type of theoretical orientation can be used to design a particular tool for a particular discipline. Nevertheless, we believe that by describing the process of this design, other researchers could apply the principles we offer here to devise their own tool to meet their particular textbook analysis needs. [2]

This article was written from part of a PhD study, the aim of which was, among others, to find a suitable approach to textual analysis that could be utilized to construct a model for textbook analysis in general. This was accomplished through the analysis of 10 grade 11 history textbooks. Only certain parts of the books were selected for analysis. These parts related to the curriculum topic of "theories of race and racism and their historical impact." This topic is of relevance not only in South Africa, where the legacy of apartheid continues to make itself felt in every sphere of life, but also in other countries grappling with racial and cultural diversity, difference, prejudice and tolerance. Thus, while addressing this topic seems so central in modern heterogeneous societies, at the same time it may also present limitations: Given its temporal relevance, it may be approached in a manner different from other historical topics that are further removed. In other words, there may be more heated and controversial responses towards this topic than, say, to the industrial revolution. Nevertheless, we believe that the model we present here can be applied to an analysis of any topic in history textbooks and that its principles can be transposed to cognate disciplines such as social studies and civics education. Towards the end we provide an example of how this could be done. [3]

In this article we focus on the methodological principles and are thus not going to present findings of the analysis of the topic itself, which has already been reported elsewhere (see MORGAN, 2010 and MORGAN & HENNING, 2011). Rather, we will present the processes of the tool design, arguing for systematic and theory-based design of instruments that are used to evaluate textbooks, more specifically, history textbooks. [4]

One of the key presuppositions from which the design process started was that textbook research is an interdisciplinary process (see PINGEL, 2010, p.43; COLE, 2010; JOHNSEN, 1997, p.25; and ISSIT, 2004, p.684). In this study, the disciplines involved were history, psychology, sociology, education, and linguistics. From history it derived the subject matter and unit of analysis (chapters in history textbooks). Moreover, the methodology of the didactics of history "can use established methods of psychology and sociology and restructure them to the peculiarity of the historical consciousness" (RÜSEN, 1987, p.286). An historical approach situates the researcher and the object of investigation in a distinctive temporal and changing sociocultural context, which is the basis for using a Vygotskian cultural historical approach. Even though VYGOTSKY was not only a psychologist (he studied a range of topics while attending university, including law, history, and philosophy, as KOZULIN [1990, p.21] explains), in current disciplinary schemas he would probably have been described as a cognitive developmental psychologist as well as a semiotician (see GOPNIK, 2008). The field of semiotic mediation, which forms the basis of the theoretical frame for this study, can also be understood to be both psychological and sociological in nature and also as a linguistic theory. [5]

Linked to history, is also the discipline of psychology. LERNER (1997, p.200) talks about history-making as a function in the healing of pathology. For example, "forgotten" trauma is brought to light through therapy "and in the retelling it is robbed of its evil power, implying that history-making is an essential part of personal growth and healing." Another psychological approach to how texts are appropriated is put forward by GROLNICK (in WERTSCH, 2002, p.43) through "self-determination theory." It involves exploring adaptations to social requirements so that children accept certain values as their own, even if they do not necessarily endorse them. Education as a field of inquiry would provide the practical applicability or purpose of the study through its involvement with a major agency of socialization: the school. [6]

At the outset, trying to incorporate all these disciplines into the design of the tool seemed somewhat overwhelming, but it also motivated the study to find points of interdisciplinary intersection, much as KELLE (2005, p.21) suggests when he discusses the notion of "sensitizing concepts" in grounded theory analysis and the merging of ideas from different theoretical origins in a heuristic framework for such analysis: "[U]sing such a heuristic framework as the axis of the developing theory one carefully proceeds to the construction of categories and propositions with growing empirical content." [7]

Thus, in using this theoretical "axis" we argue that the analysis tool that we devised (arguably the "grounded theory" emanating from the study) was constructed from a deep engagement with data and an interweaving with the points/concepts. The latter coalesced in a central tenet of the work of Lev VYGOTSKY, namely the notion of semiotic mediation (1986), which, in this study, can be seen as the core of the "axis" in grounded theory terms. [8]

In this article we will first set out the different phases of the design of the tool, showing how we followed a hybrid grounded theory procedure after the first phase. Thereafter the five dimensions of the tool (the "grounded" theory) are discussed in some detail. We show how these dimensions could be adapted to analyze textbooks in cognate disciplines. Finally, in the conclusion of the article some reflection is offered on the reliability and validity of the theoretical principles that have been put forward. [9]

2. The Three Stages of the Tool Design Process

The three phases, or stages, of the tool design and development proceeded from 1. a typical grounded theory approach of (open) data coding to 2. a deliberate activity of "going back to the literature," to search for theoretical principles for textbook analysis that would speak to the data that we had come to know closely, to 3. the blending of the first two chronological activities into the third stage, which comprised the formulation of the five dimensions of the analytical tool, or our grounded theory offering. These stages are described next.

Figure 1: The three-stage process—from data to literature to a tool and back to data [10]

2.1 A grounded theory approach to (open) data coding

To begin the coding process, we wanted to first become familiar with the sampled texts. The sample was described within case study methodology. A "case study is defined by individual cases, not by the methods of inquiry used" (STAKE, 1994, p.236). These cases are captured by their "boundedness." In this way, it is different from theoretical sampling offered by grounded theory methodologies. Theoretical sampling "means that the sampling of additional incidents, events, activities, populations [in this case additional text], and so on is directed by the evolving theoretical constructs" (DRAUCKER, MARTSOLF, ROSS & RUSK, 2007, p.1137). By contrast, in this research the sample was selected and bounded before the theoretical constructs were identified. Within a case study design the investigators identify the boundaries, and these boundaries, what is and what is not a case, are continually kept in focus (ROBERT WOOD JOHNSON FOUNDATION, 2008). Applied to this study, the case was bounded by an interest in the topic of issues around difference, stereotype, ostracization, prejudice, injustice, race and racism, and Nazism in particular, as foundations for learning possibilities of overcoming them, as represented in history textbooks. For this purpose one topic was selected in all ten textbooks. As these books followed a specific curriculum, there were also specific chapters on these topics. [11]

These chapters from the ten textbooks were coded initially in an open way in grounded theory mode, as described by TITSCHER, MEYER, WODAK and VETTER (2000, p.79). This part of the research process was the most creative/interpretive because there was freedom to identify units of meaning and to code and annotate/"memo" them in a non-determined way. In this first encounter with the data (the text of the sampled chapters) we thus coded units of text from the books inductively, writing memos/annotations in the "open-coding" fashion that STRAUSS and CORBIN (1998) and HENNING, Van RENSBURG and SMIT (2004) describe. This inductive part of the analysis laid the foundation for the eventual design tool, constructed during a process which, as STRAUSS and CORBIN (1998) explain, we searched for regularities in the data, working from a wide variety of instances/cases/examples to specific topics that would ultimately capture patterns or themes across these instances. In practice it meant that extensive notes about the texts were written in free-style. This was the first stage of the process as shown in Figure 1. [12]

To drive progression from the first to the second stage of the process we color-coded the annotations that we had made during Stage 1. As we were developing concepts and looking for some patterns, we needed more and more "colors." At this stage we were considering using Atlas.ti software for qualitative analysis but we did not want to introduce a new and unfamiliar analysis tool when we had just become familiar and confident with the color-coding process. By the time we got to Book 4, we could identify another four components for analysis, or "colors" to use for highlighting. This coding process was very effective in helping us to see what analytical categories the book analysis would require. It brought the content of the books to the surface in a systematic way and the annotations reflected our interpretation of the content. For example, we noted that there were standard and easily identifiable features to compare across all books. Some of these were the naming the actors; gauging the space allocation to certain sub-topics; examples of specific discursive uses of language; conceptual connections that we could see with the literature that we had consulted; and theoretical propositions that we had noted. [13]

We were now working in two parallel lanes of analysis, the coded and clustered contents and notes, and the literature. This literature included BAIN (2006); VAN LEEUWEN and SELANDER (1995), LaSPINA (1998, 2003), RAVITCH (2003), OSBORNE (2003), MARSDEN (2001), JOHNSEN (1997), SELANDER (1990), BREDEKAMP and ROSS (1995), RÜSEN (1993), and, of course, the two primary VYGOTSKY texts (1978 and 1986). The readings at that point pertained to both content-related matters and to more abstract-theoretical/methodological ones. As the process continued we noted questions that related to differences, similarities and problems that we had come across in the data notes and also to what we were encountering in the literature. For example, we noticed that in some books a gender theme was prominent while in others it was absent. Or, in some books the history content in question was narrated from multiple perspectives, using primary sources, while in others only the same secondary sources were used repeatedly. We noticed, as well, that history content presented from a single perspective focused largely on the assumed "perpetrators" of injustices in a macro-sociological way. In sum, the process of color-coding the annotations that we had made amounted to some form of grounded theorizing in this early stage through the process of comparison and abstracting (PUNCH, 2005, p.204). [14]

Following this mode of coding meant that the annotation notes were becoming bulkier with each addition of a textbook chapter. We struggled to order the notes into patterns while trying to theorize. We also struggled to see whether we were doing inductive or deductive coding in some instances. We were pleased to find that STRAUSS in TITSCHER et al. (2000, p.78) alleviated this problem by explaining that during the coding process the investigator is permanently switching between inductive and deductive thinking (see also KELLE, 2005). In fact, this constant alternation between setting up and testing concepts is one of the essential features of grounded theory methodology (STRAUSS & CORBIN, 1998) and we experienced it firsthand. BERGMAN (2009, winter school lecture notes taken) comments the following on early stages of text analysis:

"You are already analyzing when you pay special attention to specific aspects of your data. In your data gathering you are already doing a pre-analysis. All the results will be a function of the selection you made at the beginning already—this is the first level of analysis. Then you select from this selection based on what your focus or question is. No piece of information is important unless it relates to your focus. Then a formal analysis: for example thematic clustering must follow. And finally you must interpret the themes: where do they come from, what does it mean for South African education reform (for example), i.e. link it back to your theoretical framework." [15]

Seeing that the annotations were getting too bulky for pattern-finding, we needed to find a way to reduce, or to shrink the data. By the time we had made extensive annotations and color highlights on the data in the 10th book in the sample, we realized that we had, almost unknowingly, systematically prepared the text for thematizing. We now knew that we would need specific, guiding theory in order to conceptualize what we had clustered inductively, specifically to avoid naïve empiricist work and also not to fall into the trap of "emergence." [16]

As KELLE (2005, p.18) proposes:

"Experts with longstanding experience may be able to choose the right heuristic concept intuitively thereby drawing on rich theoretical background knowledge. In contrast to that novices may benefit from an explicit style of theory building in which different 'grand theories' are utilised in order to understand, explain and describe phenomena under study. A systematic comparison of the results from the use of different heuristic concepts is by all means preferable to an 'emergence talk' which masks the use of the researcher's pet concepts." [17]

We needed a framework from which to work with the coded data as we had not been able to find patterns that made sense, despite the intuitive use of our theoretical knowledge. We decided to consult authority voices that could provide specific, theoretical categories against which to offset the categorized data. We needed these voices because the data were disparate and it was challenging to further abstract from our "grounded" work thus far. We wished to make this explicit, taking cognizance of the GTM caveat to include theoretical perspectives in the process of analysis, whether in building the "axis" or going further than that. These would have to come from the disciplines in which we had been reading. This was the beginning of Stage 2 (see Figure 1). [18]

2.2 From grounded theory back to the literature: Towards finding a workable heuristic frame

At this point the study could have gone in various directions, each, possibly, leading to different outcomes. But, because of our claim that textbooks are primarily semiotic mediators, and because they are aimed at the activity of learning in the activity systems of schools and classrooms, we therefore employed the notion of "semiotic mediation" as used by VYGOTSKY and as expanded by the literature that was spawned by his work (KOZULIN, 1990; WERTSCH, 1985, 2002; and KARPOV, 2005). Admittedly, what also motivated us was KOZULIN's assertion that VYGOTSKY's writings "offer little in terms of ready-made answers to scientific puzzles" and that "his skill was turning apparent puzzles into new and profound questions" (KOZULIN, 1990, p.2). Hence the influence on his writings on this study was not so much an application of a readily available theory, but providing a way of thinking about the approach to the research in more general terms, thus a more general "gaze." His work also provided a lens through which to view textbooks as signs that perform as tools in learning and as such are powerful artifacts in education. [19]

In Stage 2 of the process of developing the now emergent tool for textbook analysis/evaluation we searched for principles of text analysis that would fit the central principle, namely that these texts are semiotic in a very specific way—they mediate learning in a school context. School learning implies the development of higher order thinking or mental skills. That is why the "psychological tools" that function as mediating agents in the development of higher mental processes in children and adolescents are also the heuristic base of the underlying theory of cognitive development espoused by VYGOTSKY and researchers who work with his theories. The signs, or semiotic mediators, are utilized as auxiliary means of solving given psychological problems such as remembering, comparing something, reporting, choosing and so on, and are analogous to the invention and use of tools in physical activity. Such use of tools or signs affects humankind's behavior (VYGOTSKY, 1978, pp.52-54). It is for this reason that textbooks can play a vital role in shaping development and thus behavior. This is especially significant in the wake of the "social constructivist rush," where, in our view, too little is made of the semiotics of mediation, and the work of Lev VYGOTSKY is often glossed over and simplified. This is why we chose the core concept of semiotic mediation as the axis in the development of the analysis tool. It also resonated with some of the literature we had consulted on textbook research: WERTSCH (2002), SELANDER (1990) and LaSPINA (1998), for example, have drawn on this concept of semiotic mediation when studying empirical phenomena such as the relationship between culture and remembering; theory development for pedagogic text analysis; and visual design of textbooks, respectively. [20]

At the same time, we could also apply the concept of semiotic mediation to the research process itself: the signs in this research were the textbook content. During the research process this content was also coupled with the first interpretive activity as captured in and manifested by the annotative notes and the color codes during the reading of the chapters (see Stage 1 in Figure 1). The research thus continued to proceed on two levels. These first interpretations manifested as signifiers of meaning, with our own thinking as the interpretant. The work at this stage was, thus, simultaneously proceeding on a cognitive- and a metacognitive level. But our thoughts and reflections were not yet, by any reach, the final signifying object that we were pursuing. In research terminology, one could say that the object was still "latent," we had not yet been able to make it tangible or to show it in operationalized form. [21]

For further "operationalization," the textbook analysis process needed to be captured in a way that would show how we moved from thinking about the history book content and making interpretive notes about it, to finding some cross-over to the literature, to further refine it. This, we believed, would make the meaning more tangible for the eventual use of the tool as an instrument that others could also find useful. Stage 2 thus included identifying categories from the literature on semiotic mediation in preparation for devising of the dimensions for the tool. We focused mainly on the work of WERTSCH (2002), KRESS and Van LEEUWEN (2006), TITSCHER et al. (2000), THORNTON and BARTON (2010), LaSPINA (1998); and BAIN (2006). The outcome of the second stage of the process was the consolidation of the findings from the inductive analysis in Stage 1 with the categories identified from the literature, using "semiotic mediation" as the primary "sensitizing concept" (BLUMER, 1954, cited in KELLE, 2005, p.15) across the stages. Finally, during the third stage, the analytical tool design was completed, based on those principles and then applied to the "data," which by now consisted of the notes that we have described as Stage 1, together with raw data. [22]

2.3 Towards the principles for the five-dimension tool

The combination of reading from a variety of disciplines, while keeping the VYGOTSKIAN concept of semiotic mediation at the center, and while keeping in mind the initial grounded theory mode of open coding, resulted in an important discovery about the process itself. There was a somewhat surprising goodness of fit between the outcomes of the two processes. We surmised that we could develop analytical dimensions from this fit. But before we did that, we put together a set of principles for textbook analysis. These principles came from the overall insights gained from the various strands of interdisciplinary literature and represent an attempt to pin down the essence of what should be considered when analyzing educational texts. Hence these principles are exploratory and present a "working model":

As a starting point, text analysis requires some standard or guide in which there are criteria that can be applied in the analysis. This could be the curriculum, or a "best practice" type of document available in a specific field. An example is a best practice guide to Holocaust education (BERMAN CENTRE FOR RESEARCH AND EVALUATION IN JEWISH EDUCATION, 2006) which outlines a range of expert educational principles for teaching emotionally demanding content that could be generalized to other, non-Jewish historical topics. Another example is the World Movement for Democracy website which is a collection of international resources connected to a range of topics; one of them being Teaching Civic Education In and Outside of School. The point is that researchers should get a feeling for what the international standards are before being narrowed by their own country's educational policies.

In order to devise a methodological model, it is necessary to find a common theoretical link, or to build a conceptual bridge, between the texts to be analyzed and the standard or guide by which to assess them. This we established with the concept of semiotic mediation. Textbooks mediate by way of specific signs that act as discursive, semiotic tools. Thus the curriculum must be analyzed for concepts and abstractions derived from the theory. For example, "making words one's own" (BAKHTIN, 1982, p.294) is the abstract concept behind the skills-driven aims of the curriculum, such as "communicating an argument," "coming to independent, critical conclusions," "evaluation of a broad range of evidence," or "critically understanding socio-economic system" (DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION, 2003). The values/attitudes aspect of the curriculum could be abstracted under the general category of "creating a usable past" (WERTSCH, 2002, p.33), or to be more specific, being able to use an interpretation of the past for democratization purposes: "advancing democracy," "personal empowerment" or "changing the world for the better" (DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION, 2003).

In order to manage the many layers of meaning, the text analysis, requires optimal structure in the heuristic tool. Such a tool should be usable as a plotting mechanism with which textbook content and appearance can be "mapped." This is because usually it is a matter of degree of mediation of a specific skill or attitude in the text that needs to be assessed. Here our focus is on text contained in textbooks, such as words and their contextualized images, maps, assessment activities and "model" answers in teacher guides. An obvious limitation is that the analysis of electronic and visual media such as photo, presentation or video data are for now excluded since they may need different approaches (see KNOBLAUCH, BAER, LAURIER, PETSCHKE & SCHNETTLER, 2008). Of course as we mention electronic data, the use of data analysis software must be also considered. If researchers wish to go this route, there are many factors to take into account when choosing a package. EVERS, SILVER, MRUCK and PEETERS (2011, p.12) mention the key ones: from "the research design; type and amount of data; the approach to data analysis; the dynamics of project (e.g. individual, team); personal style of working; to time and financial resources; etc." These authors alert us to the fact that while software may enhance the quality of our projects, they will not do so merely through their use. The quality of thinking will always be the responsibility of the researchers as software use should not be seen as a method.

KUHN (2000 [1962]) pointed to the utter impossibility of interpreting scientific facts out of the context of dominant mindset of the scientific community or "paradigm." For designing dimensions for the analytical tool this means that there must be a relationship between the dimensions and the discipline on which the text is based. There is no point in analyzing history texts using criteria for what is valued in the scientific community of, say geography. This is complicated by the fact that, as mentioned, textbook research is interdisciplinary. For example, we have identified that we need to draw from such disciplines as history, sociology, psychology, linguistics and education. When the tool for analysis is designed, it becomes important that it incorporates some elements from each of these disciplines and not only be driven by the data itself. This principle will ensure that the analysis is as multi-dimensional as textbook research is multi- or interdisciplinary.

Some notable features of the texts will be excluded by the nature of the analytical questions and the theoretical lens through which it was conceived. This is an inevitable but acceptable limitation and is important to consider if text analysis is done by multiple researchers.

The analyst must decide on a content focus—it cannot be everything. Methods must be applied to specific content because content separated from pedagogy is an incomplete metaphor for knowledge (SEIXAS, 1999, p.318). This could be achieved by employing a case study design, specifying the "bounded system" (STAKE, 1994) of the case as was done in this study. [23]

These six principles formed the basis for developing the five-dimensional tool; however, there is no relationship between the number of principles and the number of dimensions. What follows is an explanation of how these principles were put into action in the construction of the analytical tool. [24]

2.3.1.1 Dimension A: Making own/personal historical knowledge

The way in which the textbooks mediate historical knowledge, we argued, would be identified through the analyst asking questions about them as catalyzing agents for "higher order mental functions" (VYGOTSKY, 1978). These could include: What are the discipline-specific, "scientific" areas of knowledge that the textbooks mediate and how do they do it? How do they exemplify historical scholarship in the texts? What tools do textual resources provide that could enable learners to make evidence-based, reasoned judgments about the topics covered in the books? In other words, what are the semiotic mediating tools contained in the texts that allow the user to develop a sense of agency by making own, personal knowledge and not simply by remembering information? [25]

These questions are similar to LEVSTIK's characterization of a dichotomy in teachers' views of students as either "producers" or "consumers" of historical understandings. Teachers who view students as producers seek to have them use the tools of historiography and act as history detectives. Those who see them as consumers of history might emphasize "origin myths over interpretation, and consensus over controversy" (LEVSTIK cited in SAWYER & LAGUARDIA, 2010, p.1996). On this view we developed the idea that textbook authors are similarly positioned to view their readers as consumers or as producers. [26]

2.3.1.2 Dimension B: Learning empathy

This is the humanizing dimension of the analysis and involves "historical perspective-taking [which] is the cognitive act of understanding the different social, cultural, intellectual, and even emotional contexts that shaped people's lives and actions in the past" (SEIXAS, 2006, p.10). It thus is an off-shoot from Dimension A in that it involves cognition but with an added possibility for experiencing an affective response to the text content and presentation. This component of the tool is aimed at identifying opportunities for the readers to experience empathy, coupled with rational thought and metacognitive reflection. Such a reflection is central to the discipline of history, which may be thought of as "an organized metacognitive tradition in that it insists on its practitioners reflecting on what they say" and why they say things (LEE, 2011, p.66). It is closely linked to the idea of reflexivity, which is a type of "epistemological subjectivity: using (self-) reflexivity as an important tool to access and to develop scientific knowledge" (BREUER, MRUCK & ROTH, 2002, p.2). This part of the tool is aimed at identifying those content elements that could elicit emotional, affective responses in readers because the text requires them to take different perspectives. [27]

One way of thinking about this dimension would be to compare the reader's response to a relationship between what WERTSCH (2002, p.46) describes as "re-experiencing" and "remembering," both of which are intra-psychological processes. WERTSCH explains that the difference between remembering and re-experiencing concerns the distance or separation that people experience between their current lived world and an event from the past. He explains that remembering presupposes such a separation and that the textual mediation, although difficult to detect, on the one hand functions to create a degree of separation. Re-experiencing, on the other hand, assumes that a person or group merges with, or is part of the past event. "In its extreme form, [re-experiencing] may be a way of representing the past that seems to involve no textual mediation at all, the result being that the distance between the observer and the event dissolves" (p.46). From this, the main analytical concern is to ask what the degree of proximity is that textual mediation achieves. This is sometimes discussed in terms of a memory being "experience-far" or "experience-near" (CONWAY, cited in WERTSCH, 2002, p.46). Different texts thus mediate memories—in this case historical events in textbooks—in different ways, either allowing a reader to have a "being there" experience, or reporting on events in ways that create a wide distance between readers and events. For example, primary sources, or "traces" (SEIXAS & PECK, 2004, p.110) tend to mediate more “experience-near” accounts of the past than secondary ones. [28]

One of the tools that can trigger re-experiences would first and foremost be narratives. KEATING and SHELDON (2011, p.7) note that narratives in history education can stimulate the student's imagination, and "in putting himself in another's place sympathy is born." The term used in this type of experience is empathic literacy, or to read with empathy. This dimension therefore asks what kind, if any, empathetic learning the texts mediate. [29]

2.3.1.3 Dimension C: Positioning a textual community

This dimension presents a way to look at how positioning of the subject (RIBEIRO, 2006) occurs in communicative actions and events as encountered in the textbooks. It is the counterpart of the intellectual, epistemological aspects of Dimension A of the tool in that it looks at the kinds of "uses" the past is being put to, rather than the kinds of historical skills that are mediated. Or, to use LEE's terminology, the tool would look at authors' disposition to "plunder the past to produce convenient stories for the present" (2011, p.65, emphasis in the original). The notion of textbook composition as an act of deliberately creating "uses" of the past, or by "plundering the past" for utility value in the present, is related to a discourse view of texts. FAIRCLOUGH (2003) and other authors, such as KRESS and Van LEEUWEN (2006) argue that texts are produced in a social context and are in themselves also social action. With this dimension of the tool the analyst wants to find out what the social consequences of knowledge consumption might be when history facts may be presented in a specific/biased fashion, and when observable ideological positions are espoused by the authors (see MORGAN & HENNING, 2011). [30]

So, while this dimension of the tool is informed by a sociological approach, the way findings are gleaned from it also requires a linguistic, semiotic approach (KRESS & VAN LEEUWEN, 2006 and FAIRCLOUGH, 2003). Such an approach posits that in all interactions, users of language (and other sign systems) bring with them different dispositions towards that language or system, and these are closely related to their social positions (VÄISÄNEN , 2006, p.300). From a social semiotics perspective, signs are always "motivated by the sign-maker's interests" (KRESS & VAN LEEUWEN, 2006, p.8). By way of this dimension the analyst tries to get to the bottom, or the subtext, of "the sign maker's interest," as identified by some of the clues in the text. For example, if a certain word is used in an overly-repetitive manner, or if stories are broken up and separated into units to fit certain themes and arguments, or if images are extracted from their original context to illustrate a definable point of view, then such discourse markers can inform the analyst of the positioning of the authors to the subject matter and in turn to their readers. [31]

2.3.1.4 Dimension D: Fashioning stories

Stories, or narratives, have already been implied in the discussion of Dimension B, because it is in the stories and the characterizations that empathy is evoked. WERTSCH, a leading cultural historical theorist in the Vygotskian tradition, argues that narratives are the principal sociocultural tool for understanding the past: "Narrative form is taken to be a cultural tool for grasping together a set of events, settings, actors, motivation, etc. into a coherent whole in a particular way" (WERTSCH, 2002, p.61). Few would disagree that narrative texts are the primary vehicle for presenting history knowledge because they rely on the universal qualities of stories, one of which is the temporal ordering principles (TITSCHER et al., 2000, p.23). One knows that a story will have a beginning, a middle, and an end, that there will be a discernible plot and prominent characters. Readers of history textbooks are usually more inclined to read a text if there is a story and if it utilizes the style and techniques of story-telling, for which readers are prepared because they know story grammar. Also, the themes are so much more appealing when they are presented in narrative rather than, for example, in an information timeline or in a chronological list. The element of drama is inherent in them and hence they are sometimes seen as "the creative conversion of life itself into a more powerful, clearer, more meaningful experience. They are the currency of human contact" (McKEE, n/d). [32]

On this dimension the analyst can look at all aspects of stories and conduct a basic narrative analysis, as suggested by TITSCHER et al. (2000, p.128) in order to understand story structures as the fundamental values and norms which underlie a story. To appreciate the richness of how narratives function as cultural tools, WERTSCH (2002) uses the concept of a "schematic narrative template" to show that there are also categories of stories with socially constructed frames. Such templates involve "generalized plot structures that underlie a range of specific stories" (BARTON & McCULLY, 2010, p.145). These authors explain that, for example, the story of the September 11 attacks often relies on a template involving "'terrorists' threats to the innocent United States" to explain a wide range of events (p.145). [33]

There may thus be an inherent danger in the way narrative templates are used. A textbook analyst needs to take cognizance of the fact that such templates are the underlying "meta" pattern of the narrative and that they can be abused by involving grand narratives that are no more than ideological positions. For example, when pre-cast characters function as constant, stable elements of a tale, independent of how and by whom they are embodied in a specific story (p.145), the characters are "flat," rather than "round." They become simply tools to convey a position. In the South African history textbooks that we examined there was, for example, generally one type of "European colonist," one type of "colonized person," or one type of "racist." [34]

Questions that can be posed in this dimension are: what, if any, is the master narrative or pre-cast plot in the stories, with "master narratives" referring to a dominant and overarching template that presents the literature, history, or culture of a society (ALRIDGE, 2006, p.681) in a specific way. Who are the characters and do they develop authentically or do they remain "flat," serving a specific purpose of the template? Are the characters thus "characters" or rather (arche) types (stereotypes)? What are the functions of characters in the plot? What are the narrative gaps? Are there any counter-narratives? [35]

2.3.1.5 Dimension E: Orientating the reader

After handling the books many times over, we knew that we also needed to look at form, space and the art of design and composition of the textbooks. Dimension E was constructed as a result of this. In addition, we had also learned about the Formalist influence on VYGOTSKY's work, namely how the materials of art stand in relationship to the form of art (KOZULIN, 1990, p.38). We found that we could apply it to the analysis, asking questions such as, what are the physical features (form) of the textbooks and what does this imply about the relationship to the content (material)? The design and layout features orientate and scaffold the reader like a good webpage or smart phone application does. This includes elements such as structure of the content page, language level, use of symbols such as exclamation marks, translation of non-English content, format (size), text flow, layout, user-friendliness, ease of orientation (such as including an index, glossary and headers for example), quality of images, and so on. These artefactual features can be seen as cognition tools, because form and content are related, as UHRMACHER (2009, p.615) attests. [36]

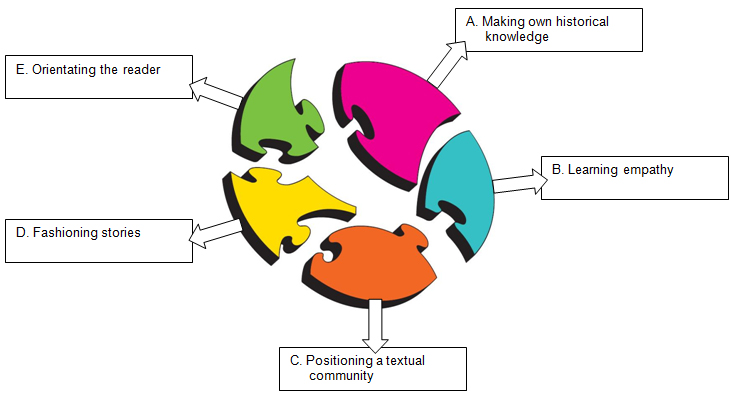

Examining the physical features of the textbooks would of course include an analysis of the sampled images, maps, cartoons or other illustrations in order to try and identify what their main functions are. This can be assessed by looking at the relationship between language text and images and how the two text types function together, for example in the captions of pictorial, image illustrations. The aim is to see if the form and the content of the two cohere. A central assumption here is that images, as a resource of representation, like language, display regularities which can be made the subject of relatively formal description or picture "grammar" (KRESS & Van LEEUWEN, 2006, p.20). The main aim with this dimension was to find out how the sign-makers, the authors, position themselves in the mediation of history through the use of images and related captions and representation in the language text. Arguably this dimension of the analytic tool has a strong relationship to Dimension C or "positioning a textual community." In Figure 2 below the different components of the tool are shown.

Figure 2: The five dimensions of the analytical tool [37]

This graphic representation is not meant to imply that these five dimensions exhaustively interrogate all aspects of the data. One or more of the components of the analytic model may not be required for some books, such as biology textbooks, for which the author would seldom use full narratives, but would utilize simulations or metaphors. Neither is this diagram meant to imply that data can be categorized neatly into those puzzle pieces. Rather, the pieces should be imagined to be dynamically shifting, moving clusters that overlap and whose boundaries are not as neatly defined as the diagram suggests. As part of one tool, these five dimensions also have to cohere; we have attempted to map out some of the relationships that indicate coherence. [38]

In conducting the analysis of the ten books, this tool proved to be fruitful. We found the contents and pedagogic implications of one textbook to exemplify a strong mediation of learning of a higher order. Two of the books had many of the elements that we have now begun to formulate in criteria for textbook analysis, one of which is that it needs to be multi-dimensional, as in the model presented here. The other books, based on the sampled chapters, were found to be, at best, sources of some information, and at worst, compromisers of history education. [39]

3. Application of the Tool to Other Subjects

The methodological implication for textbook research is that similar analytical dimensions could be created for data pertaining to other subject textbooks. This is because the theoretical approach is flexible enough to allow for the seeking and naming of those tools of the text that fulfill those dimensions. For example, one could devise a similar analytical model for a related subject, namely "life orientation," which is a compulsory subject for all learners in all grades in South African schools. It is a type of citizenship education. It "is the study of the self in relation to others and to society" and "addresses skills, knowledge, and values about the self, the environment, responsible citizenship, a healthy and productive life, social engagement, recreation and physical activity, careers and career choices" (DEPARTMENT OF BASIC EDUCATION, 2011, p.8). [40]

Text analysis could still focus on "making own knowledge"—how do texts allow students to create knowledge about the listed topics and what are the implications for cognitive development and conceptual change in children and youth? In other words, what abstract, logical, deductive reasoning is the text mediating? [41]

Secondly, "learning empathy" could be captured with questions like "How do texts mediate concepts of 'responsible' and 'social engagement'?," whereby the focus would be on how to not think primarily about the self and one's own self-preservation. It would ask what kind of "social sympathies and antipathies are formed" (VYGOTSKY, quoted in KARPOV, 2005, p.205) as a result of the textual mediation? [42]

Thirdly, "positioning a textual community" could be addressed by a question like "What kind of understanding do texts mediate about 'healthy', 'productive' or 'citizenship'?," constantly asking what kind of imagined community, if any, is being created. Are differences "glossed over" by "imagining that we can transpose values across cultures through the transcendent spirit of a common humanity" (BHANBHA, quoted in MATTSON & HARLEY, 2003, p.301)? How is language used to mediate the topic? Such questions would allow a researcher to find and name the textual features that mediate the different types of positionings. [43]

The fourth dimension, "fashioning stories," is a bit more challenging to translate, given that life orientation is not an established scientific field of enquiry and that, unlike the narrative acting as the primary tool in historical scholarship, it is not clear what the typical methods for mediating knowledge are in life orientation. One must look at other disciplines. The life orientation curriculum repeatedly stresses the need to make "informed and responsible decisions." An analytical dimension could be developed to address this; perhaps from management science or business motivational literature. This could be brought into relationship with discipline-specific concepts from psychology or sociology, such as motivation, given that life orientation is concerned with the relationship between self and society. Thus an example of Dimension D could be "motivating students," or "learning to make decisions," which would still achieve a practical component similar to how narratives act as practical tools in historical enquiry. [44]

Finally, Dimension E—orientating the reader—would have as much relevance for a life orientation textbook as for any other, since the aesthetic and spatial features of a textbook apply across disciplines. [45]

There are of course limitations of this study. One of the major ones is that we chose only textbooks as the (semiotic) mediating artifacts and that we did not supplement the research with classroom observation, or interviews with teachers and pupils, and that therefore we did not gain any insight into the various pedagogical issues at play in a classroom. Nevertheless, we contend that textbooks are stand-alone artifacts and that they are a public form of knowledge, indicative of the general and overall discourse permeating a society at a given time. Thus, analyzing textbooks comprises a historical study in its own right and we found this to be good enough reason for studying them "in isolation." This is not to say that we do not recognize not only the possibility, but the likelihood, that teachers may not use these books, or that they modify and supplement their contents with their own materials. [46]

Linked to this is another limitation, which is, as alluded to already, that we concentrated only on printed textbooks. We recognize that increasingly learning takes place through e-books, presentations, video, drama, interactive sites (both physical and virtual), and so on. In the light of this, such media should also be included when designing tools for text analysis. Testing our analytical model on and adapting it for use with educational films, websites or museum exhibitions could become exciting possibilities for future research. [47]

5. Conclusion: The Need for a Systematic Tool for Analysis

What concerned us at the outset of this study, and it still does, is whether the construct of a tool for analysis, which would suggest a certain methodology, could manifest from theoretical principles, and thus, ultimately, explore such theory. The problem at the outset was the interdisciplinary nature of this type of work and how a central theoretical position could hold. In this study such a central construct was used, namely VYGOTSKY's idea of "semiotic mediation." Although the latent construct manifested in specific indicators in the various dimensions of the tool, they are, by far, not complete. To truly validate the tool and to establish its reliable use across more chapters in the books and also more books in comparable disciplines, much more research needs to be conducted. [48]

In a way, then, this study was a comprehensive pilot study. Limited by the usual obstructions of subjective interpretation and no inter-rater reliability, and composed from a specific epistemological position of the researchers themselves, it is a beginning. We would argue that the audit trail of the design and development of the tool, specifically as set out in the full PhD study, is confirmable. In other words, the steps of the design can be repeated and other books and chapters can be used to show how reliable the tool can be and also how the process of its construction can be tested for reliability. [49]

Ultimately, though, a tool is a heuristic that has to be used idiosyncratically, and that is what we hope other researchers will do, so that the tool, like a new substantive theory, can be tested and validated. What we can say with more certainty, though, is that the VYGOTSKIAN tenet of "semiotic mediation" has been found to be a valid construct with which to work when looking for a way to make a tool for textbook analysis. [50]

The PhD study on which this article is based was conducted at the University of Johannesburg from 2008 to 2011. The financial assistance of the National Research Foundation towards the costs of this research is hereby acknowledged. The opinions expressed and the conclusions arrived at are those of the authors and should not necessarily be attributed to the National Research Foundation. We would also like to thank the anonymous peer reviewers for their very insightful and helpful comments and suggestions.

Alridge, Derrick (2006). The limits of master narratives in history textbooks: An analysis of representations of Martin Luther King, Jr. Teachers College Record, 108(4), 662-686, https://www.tcrecord.org/Content.asp?ContentID=12365 [Accessed: November 6, 2012].

Bain, Robert (2006). Rounding up unusual suspects: Facing the authority hidden in the history classroom. Teachers College Record, 108(10), 2080-2114.

Bakhtin, Mikhail (1982). The dialogic imagination: Four essays. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Barton, Keith & McCully, Alan (2010) You can form your own point of view: Internally persuasive discourse in Northern Ireland students' encounters with history. Teachers College Record, 112(1), 142-181.

Bergman, Manfred, M. (2009). Qualitative data coding methods. Lecture held at the University of Johannesburg, Social Sciences Methodology Winter School, June 2009.

Berman Centre for Research and Evaluation in Jewish Education (2006). Best practices in Holocaust education, http://www.sfjcf.org/pdf/SFJCEF-JESNA-Holocaust-Education-Full-Report.pdf [Accessed: February 5, 2012].

Bredekamp, Henry & Ross, Robert (Eds.) (1995). Missions and Christianity in South African history. Johannesburg: Witwatersrand University Press

Breuer, Franz; Mruck, Katja & Roth, Wolff-Michael (2002). Subjectivity and reflexivity: An introduction. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 3(3), Art. 9, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs020393 [Accessed: June 25, 2012].

Cole, Michael (2010). What's culture got to do with it? Educational research as a necessarily interdisciplinary enterprise. Educational Researcher, 39(6), 461-470.

Department of Basic Education (2011). National Curriculum Statement (NCS), Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement (CAPS) Grades 10-12 Life Orientation, Pretoria and Cape Town, South Africa, http://www.education.gov.za/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=JH5XiM7T9cw%3d&tabid=420&mid=1216 [Accessed: November 6, 2012].

Department of Education (2003). National Curriculum Statement Grades 10-12 (general) history, Pretoria, South Africa.

Draucker, Clair; Martsolf, Donna; Ross, Ratchneewan & Rusk, Thomas (2007). Theoretical sampling and category development in grounded theory. Qualitative Health Research, 17(80), 1137-1148.

Evers, Jeanine; Silver, Christina; Mruck, Katja & Peeters, Bart (2011). Introduction to the KWALON experiment: Discussions on qualitative data analysis software by developers and users. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 12(1), Art. 40, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs1101405 [Accessed: June 25, 2012].

Fairclough, Norman (2003). Analysing discourse. Textual analysis for social research. New York: Routledge.

Foster, Stuart & Crawford, Keith (2006). What shall we tell the children? International perspectives on school history textbooks. Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing.

Gopnik, Alison (2008). The theory as an alternative to the innateness hypothesis. In Louise Antony & Norbert Hornstein (Eds.), Chomsky and his critics (pp.283-245). Oxford: Blackwell.

Henning, Elizabeth; Van Rensburg, Wilhelm & Smit, Brigitte (2004). Finding your way in qualitative research. Pretoria: Van Schaik.

Issit, John (2004). Reflections on the study of textbooks. History of Education, 33(6), 683-996.

Johnsen, Egil Børre (1997). In the kaleidoscope. Textbook theory and textbook research. In Staffan Selander (Ed.), Textbooks and educational media: Collected papers 1991-1995 (pp.25-44). Stockholm: The International Association for Research on Textbooks and Educational Media (IARTEM).

Karpov, Yuriy (2005). The Neo-Vygotskian approach to child development. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Keating, Jenny & Sheldon, Nicola (2011). History in education—trends and themes in history teaching, 1900-2010. In Ian Davies (Ed.), Debates in history teaching (pp.5-17). London: Routledge.

Kelle, Udo (2005). "Emergence" vs. "forcing" of empirical data? A crucial problem of "grounded theory" reconsidered. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 6(2), Art. 27, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs0502275 [Accessed: June 18, 2012].

Knoblauch, Hubert; Baer, Alejandro; Laurier, Eric; Petschke, Sabine & Schnettler, Bernt (2008). Visual analysis. New developments in the interpretative analysis of video and photography. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 9(3), Art. 14, http://www.qualitative-research.net/index.php/fqs/article/view/1170 [Accessed: June 18, 2012].

Kozulin, Alex (1990). Vygotsky's psychology—A biography of ideas. Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

Kress, Günther & Van Leeuwen, Theo (2006). Reading images—the grammar of visual design (2nd ed.). London: Routledge.

Kuhn, Thomas (2000 [1962]). The structure of scientific revolutions. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

LaSpina, James Andrew (1998). The visual turn and the transformation of the textbook. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

LaSpina, James Andrew (2003). Designing diversity: Globalization, textbooks, and the story of nations. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 35(6), 667-696.

Lee, Peter (2011). History education and historical literacy. In Ian Davies (Ed.), Debates in history teaching (pp.63-72). London: Routledge.

Lerner, Gerda (1997). Why history matters. New York: Oxford University Press.

Marsden, William (2001). The school textbook—geography, history and social studies. London: Woburn Press.

Mattson, Elizabeth & Harley, Ken (2003). Teacher identities and strategic mimicry in the policy/practice gap. In Keith Lewin, Michael Samuel & Yusuf Sayed (Eds.), Changing patterns of teacher education in South Africa (pp.284-305). Sandown: Heinemann.

McKee, Robert (No date). Robert McKee quotes, http://www.goodreads.com/author/quotes/27312.Robert_McKee [Accessed: February 5, 2012].

Morgan, Katalin (2010). Scholarly and values-driven objectives in two South African school history textbooks: An analysis of topics of race and racism. Historische Sozialforschung / Historical Social Research, 35(3), 299-322.

Morgan, Katalin & Henning, Elizabeth (2011). How school history textbooks position a textual community through the topic of racism. Historia, 56(2), 169-190.

Nicholls, Jason (2005). The philosophical underpinnings of school textbook research. Paradigm-Journal of the Textbook Colloquium, 3(3), 24-35.

Nogova, Maria & Huttova, Jana (2006). Process of development and testing of textbook evaluation criteria in Slovakia. In Éric Bruillard, Bente Aamotsbakken, Susanne Knudsen & Mike Horsley (Eds.), Caught in the web or lost in the textbook? (pp.333-340). Basse-Normandie: IARTEM, IUFM.

Osborne, Ken (2003). Teaching history in schools: A Canadian debate. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 35(5), 585-626.

Pingel, Falk (2010). UNESCO guidebook on textbook research and textbook revision (2nd revised and updated ed.). Braunschweig: Georg Eckert Institute for International Textbook Research.

Punch, Keith (2005). Introduction to social research—quantitative and qualitative approaches (2nd ed.). Newcastle: Sage.

Ravitch, Dianne (2003). The language police: How pressure groups restrict what students learn. New York: Knopf.

Ribeiro, Branca (2006). Footing, positioning, voice. Are we talking about the same thing? In Anna De Fina, Deborah Schiffrin & Michael Bamberg (Eds.), Discourse and identity (pp.48-82). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (2008). Case study, http://www.qualres.org/HomeCase-3591.html [Accessed: June 18, 2012].

Rüsen, Jörn (1987). The didactics of history in West Germany: Towards a new self-awareness of historical studies. History and Theory, 26(3), 275-286.

Rüsen, Jörn (1993). Studies in metahistory. Pretoria: Human Sciences Research Council.

Sawyer, Richard & Laguardia, Armando (2010). Reimagining the past/changing the present: Teachers adapting history curriculum for cultural encounters. Teachers College Record, 112(8), 1993-2020.

Seixas, Peter (1999). Beyond "content" and "pedagogy": In search of a way to talk about history education. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 31(3), 317-337.

Seixas, Peter (2006). Benchmarks of historical thinking: A framework for assessment in Canada. University of British Columbia: Centre for the Study of Historical Consciousness, http://historicalthinking.ca/sites/default/files/Framework.Benchmarks.pdf [Accessed: November 6, 2012].

Seixas, Peter & Peck, Carla (2004). Teaching historical thinking. In Alan Sears & Ian Wright (Eds.), Challenges and prospects for Canadian social studies (pp.109-117). Vancouver: Pacific Educational Press.

Selander, Staffan (1990). Towards a theory of pedagogic text analysis. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 34(2),143-150.

Stake, Robert (1994). Case studies. In Norman K. Denzin & Yvonna S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (pp.236-247). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Strauss, Anselm & Corbin, Juliet (1998). Basics of qualitative research techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (2nd ed.). London: Sage.

Thornton, Stephen & Barton, Keith (2010). Can history stand alone? Drawbacks and blind spots of a "disciplinary" curriculum. Teachers College Record, 112(9), 2471-2495.

Titscher, Stefan; Meyer, Michael; Wodak, Ruth & Vetter, Eva (2000). Methods of text and discourse analysis. London: Sage.

Uhrmacher, Bruce (2009). Toward a theory of aesthetic learning experiences. Curriculum Inquiry, 39(5), 613-636.

Väisänen, Jaakko (2006). Visual texts in Finnish history textbooks. In Éric Bruillard, Bente Aamotsbakken, Susanne Knudsen & Mike Horsley (Eds.), Caught in the web or lost in the textbook? (pp.297-304). Basse-Normandie: IARTEM, IUFM.

Van Leeuwen, Theo & Selander, Staffan (1995). Picturing "our" heritage in the pedagogic text: Layout and illustrations in an Australian and a Swedish history textbook. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 27(5), 501-522.

Vygotsky, Lev. S. (1978). Mind in society (ed. by M. Cole, V. John-Steiner, S. Scribner & E. Souberman). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Vygotsky, Lev. S. (1986). Thought and language (rev. and ed. by A. Kozulin). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Weinbrenner, Peter (1992). Grundlagen und Methodenproblem sozialwissenschaftlicher Schulbuchforschung. In Peter Fritzsche (Ed.), Schulbücher auf dem Prüfstand – Perspektiven der Schulbuchforschung und Schulbuchbeurteilung in Europa, in Studien zur internationalen Sculbuchforschung (pp.33-54). Braunschweig: Schriftenreihe des Georg-Eckert-Instituts.

Wertsch, James (1985). Culture, communication and cognition: Vygotskian perspectives. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wertsch, James (2002). Voices of collective remembering. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Katalin MORGAN is currently a lecturer in the Curriculum Division of the School of Education in the Humanities Faculty at the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. Her research interests include educational media design; history curricula, teaching and learning; qualitative research methodology, and Holocaust studies.

Contact:

Katalin Morgan, Ph.D.

University of the Witwatersrand

27 St Andrews Rd, Parktown, 2193

South Africa

Fax: +27 (0)86 765 4177

Tel.: +27 (0)11 717 3497

Cell: +27 (0)83 473 0774

E-mail: Katalin.Morgan@wits.ac.za, katalinmorgan@gmail.com

URL: http://www.wits.ac.za/staff/katalin.morgan.htm

Elizabeth HENNING is professor of Educational Linguistics in the Faculty of Education at the University of Johannesburg. Her current research focus is teacher development and literacy education, specifically education in the early school years.

Contact:

Elizabeth Henning, Ph.D.

Professor of Educational Linguistics

Centre for Education Practice Research

Faculty of Education, Soweto Campus

University of Johannesburg, South Africa

Cell: +26481 1249644 or +2772 4057281

E-mail: ehenning@uj.ac.za

URL: http://www.uj.ac.za/cepr/

Morgan, Katalin & Henning, Elizabeth (2012). Designing a Tool for History Textbook Analysis [50 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 14(1), Art. 7,

http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs130170.