Volume 14, No. 1, Art. 14 – January 2013

Navigating the Politics of Fieldwork Using Institutional Ethnography: Strategies for Practice

Laura Bisaillon & Janet M. Rankin

Abstract: Discussion and analysis of characteristics and tensions associated with fieldwork in two projects using institutional ethnography is the focus of this article. Examined in comparison with each other, the first exemplar explores the organization of the Canadian immigration system and the mandatory medical screening for the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) of immigrants within this. The second exemplar looks at how nurses' work in a selection of Canadian hospitals is organized. The argument made is that the politics of deliberately maintaining a standpoint on the side of a set of people (immigrants with HIV and nurses)—where inquiry begins from the experiential knowledge and concerns with the world of these constituents—gives rise to challenges to which the researcher must contend and adapt. Mobilizing examples from our fieldwork, we explore several such challenges and explain the research decisions we made in the face of these. In this article, we present insights and practical strategies for researchers who are preparing to use institutional ethnography as a strategy for critical social inquiry.

Key words: critical methods; epistemology; fieldwork; HIV/AIDS; institutional ethnography; nursing; social organization; sociology; standpoint

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. Institutional Ethnography

3. Standpoint Politic

4. Focus and Characteristics of the Two Projects

4.1 Immigration and HIV policy study

4.2 Nursing work study

4.3 Coherence between two projects and use of texts

5. Fieldwork Challenges (and Strategies)

5.1 Focus on material conditions

5.2 Dissonant knowledge claims

5.3 Following analytic threads and gaining access

5.4 Tense interviews and the standpoint politic at work

5.5 Visual aid

6. Unexpected Opportunities (and Challenges) for Collecting Data

6.1 Time and waiting work

6.2 Busy-ness and pragmatics of professional time

7. Conclusion

1. Introduction1)

This article results from our methodologically focused discussions that have taken place during the last two years. Our association began as a student-mentor relationship, where one of us, Janet RANKIN, a nursing academic, provided methodological guidance to the other, Laura BISAILLON, an interdisciplinary social scientist, during her doctoral training. While our fields of research are not the same, and, the theoretically informed empirical projects we discuss represent two distinct programs of research (that is, we were not co-investigators), the common ground on which we tread in this article is our choice to use institutional ethnography as a method of inquiry for the work examined. Institutional ethnography, the main tenets of which are detailed in the following section, is a theoretically informed research strategy through which knowledge about how the social world is coordinated and organized is uncovered. Explication of social processes is the analytic endpoint and product (CAMPBELL, 2010; CAMPBELL & MANICOM, 1995; DOBSON, 2001; MAKING CARE VISIBLE GROUP, 2002; WALBY, 2007). [1]

A dominant and recurring theme in our discussions (and debates) was the thorny issue of challenges we experienced during the conduct of our research. In particular, our exchanges took the shape of sharing, comparing, and exploring—with a view to understanding—challenges that, we came to discover, were manifest for both of us during our immersion in the field. After significant reflection, we came to understand, and were able to articulate, that a key organizer of numerous fieldwork challenges common to our projects was the politics embedded in the method of investigation, institutional ethnography. [2]

In what follows, we list and discuss some of these fieldwork challenges. To do this, we provide illustrations from our respective projects. We also engage in comparisons between them. The argument advanced is that the politics associated with maintaining a standpoint on the side of a particular set of people—where inquiry begins from their experiential knowledge of and concerns with the world—gives rise to challenges during field immersion. We do not identify and discuss all the challenges we encountered during the course of our projects. Rather, we focus on challenges reasoned to stem from the politics of standpoint; what we refer to as a standpoint politic. Adopting a standpoint position from which to begin is a central commitment in and starting point of most projects using institutional ethnography. Exploring how a standpoint politic shapes fieldwork practices is the challenge taken up in this article. [3]

Standpoint is a social position within the bodily experience, relevancies, and everyday knowledge of people in a designated group or social location. Those relevancies, knowledge and experience are the starting points informing the research design of an institutional ethnography. The researcher is interested in explicating the socially organized and coordinated character of society's institutions and the implications of these arrangements for this group of people.2) Knowledge from any standpoint is partial because people know the world from the particular social location they inhabit. In an institutional ethnography, the social relations connecting people's activities are uncovered and described. Importantly in institutional ethnography, standpoint is not standpoint epistemology, where knowledge of one group of people is favored over that of another. Rather, standpoint is an empirical affair that can be ethnographically described. (The substance of feminist critiques of Dorothy SMITH's approach to social investigation dating from the 1990s was her use of standpoint [CLOUGH, 1993; MANN & KELLEY, 1997; D. SMITH, 1997]. Direct engagement with these conversations is beyond the scope of this article.) [4]

We advance that social scientists using institutional ethnography, and particularly neophytes, are likely to experience some of the challenges that we experienced during our fieldwork as explored herein. For example, standpoint politic entered into and shaped the access to research settings in both of our projects, including the tenor of interviews and participant observations. Following the logic that other researchers will grapple with similar challenges, we assume that fellow researchers can usefully employ the strategies we developed to contend with and adapt to these. For this purpose, in this article we explain the research decisions we made to respond to and work with unexpected features of fieldwork. For example, we identify and discuss apparent obstacles as valuable features of how the institutions we investigated function. We offer new and practical tools that researchers can adopt to carry out rigorous and successful institutional ethnographic fieldwork. [5]

Critical reflection on the characteristics and tensions associated with institutional ethnographic fieldwork—and discussion of research practices in response to these challenges—is useful for several reasons. First, we aim to engage with social scientists from around the world; persons who are trained variously, and who work in a variety of languages. We do this in the interest of piquing their interest of using institutional ethnography to carry out critical social science inquiry. [6]

Second, such an examination contributes to the methodological literature by extending sociologist's Marjorie DeVAULT and Liza McCOY (2004) and Liza McCOY's (2006) seminal work that discusses how the orientation to research and the research process in institutional ethnography are distinctive from other critical social science approaches. This article also adds to the methodological exchange initiated by sociologists Peter GRAHAME and Kamini GRAHAME (2009), in which the authors examined, in conversation with one another, fieldwork experiences and impediments in their projects using institutional ethnography. Their comparative examination of fieldwork practices produced a thoughtful exploration and critique of the social relations governing their fieldwork practices. [7]

Last, we link with "immanent critiques" of social science research that neglects to join the personal and political (MYKHALOVSKIY et al., 2008, p.195). Institutional ethnography is a research tool that opened up the opportunity for both of us to systematically explore and critique the socially organized and coordinated features (and consequences) of complex, modern institutions articulated around an immigration system (Laura BISAILLON) and a hospital system (Janet RANKIN). Both of our inquiries started within people's subjective experience, but they did not stay there because an institutional ethnography is not about people per se. Rather, focus is on elucidating and understanding connections between people where these institutional arrangements are the objects of analysis. This particular analytic emphasis on social and organizational arrangements produces research findings that stretch beyond any one person's subjective experience, which makes results generalizable beyond individual accounts. These heuristic devices enter the personal into the sociopolitical world of which subjective experience is invariably a part. In this way, our institutional ethnographies generated findings that stretch beyond any one project, and hold the promise of being used by civil society advocates in their work of redressing social inequalities and inequities. [8]

This article is organized into seven sections. In Sections 1 through 3 we explain institutional ethnography and define standpoint politic as used in this article. In Section 4, we provide overviews of and explain the relationship between the two projects that inform this article. In Section 5, we identify and discuss challenges that we experienced while in the field, and in Section 6, we explore and analyze the social organization and consequences of these challenges. Before moving to conclude this article, we analytically discuss the research decisions and strategies we coined to adapt to unexpected features of fieldwork. [9]

Institutional ethnography is a theoretically informed research approach that explicates the socially coordinated character and organization of people's lives. Institutional ethnography is a project that took shape during the 1970s, originating in the work of sociologist Dorothy SMITH (1977, 1999, 2002). It is a critical research strategy located within a post-positivist paradigm. Institutional ethnography is a "formal, empirically based [and] scholarly" (MYKHALOVSKIY & McCOY, 2002, p.20) approach that draws on Marxist and feminist theorizing to uncover how society's institutions regulate people's lives (CARROLL, 2006; GUBA & LINCOLN, 1994; MARX & ENGELS, 1970 [1846]; D. SMITH, 1977; see Marie CAMPBELL & Ann MANICOM, 1995, and Liza McCOY, 2008, for overviews of the approach's intellectual lineage and antecedents). [10]

In this form of critical inquiry, data collection techniques are largely consistent with those of qualitative approaches, and commonly include interview, observation, and textual analysis. Analysis is an iterative and inductive process that begins in the first interview and continues through write-up of results. The goal is to build an empirically informed argument based on material practices occurring in the institutional settings explored. In both of our analyses, we both moved through the data examining taken-for-granted features of people's practices; considering contradictions and tensions in informants' experience; and, identifying clues about the relations connecting people's practices. In institutional ethnography, there is no proscribed number of informants. Emphasis is instead placed on features of experience, diversity, and social location. It is important that informants have first hand experience with the issues or processes being studied, and it is analytically useful if persons represent various diversities. For practical guidance on how to carry out institutional ethnographic work, including the method's epistemological and ontological commitments, we refer readers to the practitioner's guide "Mapping Social Relations: A Primer in Doing Institutional Ethnography" by Marie CAMPBELL and Frances GREGOR (2004). [11]

In the approach offered by institutional ethnography, the skills and capacities of ethnography are turned towards describing and addressing the ruling arrangements that are embedded in society's institutions. The aim is to unearth social organization and social relations; moving past interpretation to produce faithful representations of how things work in people's lives. Sociologist Kevin WALBY (2007) notes the "humanist approach" of institutional ethnography: where analytic attention is on understanding how society's institutions govern people's lives, and where explications of how things are socially coordinated are key endpoints (p.1018). Understandings about how things happen are generated from an empirically observable rather than a theoretically determined place. This is a central ontological commitment and organizer in institutional ethnography. This orientation to research stems from the assumption that ideas and concepts are produced through—and not independent of—people's practices (see MARX & ENGELS, 1970 [1846]). [12]

The understanding of texts as coordinators of people's activities distinguishes institutional ethnography from much anthropological or sociological ethnography. That said, extended case method (BURAWOY, 2009), global ethnography (BURAWOY, 2000), multi-sited ethnography (MARCUS, 1998, 2012), and, political ethnography (SCHATZ, 2009) are ethnographic approaches that share some common epistemological and methodological features with institutional ethnography. For example, researchers using all these approaches set out to explore the world from within people's activities; they are concerned with understanding power asymmetries; and, they use relations of imbalance as entry points into investigations of social processes and ruling arrangements that stretch beyond and through local and interactional settings. Institutional ethnography's distinctive contribution is the commitment to staying closely connected to the material features of people's practices, which are the sources of data. In this approach, people and the material features of their activities replace theoretical understandings of these. [13]

Over the last thirty years, institutional ethnography has been used as a tool to investigate an assortment of organizational processes. These include, but are not limited to, administration of bodily hygiene by nurses (DALE, ANGUS, SINUFF & MYKHALOVSKY, in press); workplace integration and access for persons with disabilities (DEVEAU, 2012); injured nurses' return to work (CLUNE, 2010); citizen engagement in municipal government policy making (D. SMITH & HUSSEY, 2007); professional expertise (MYKHALOVSKIY, 2001); and, gay men's high school experience (G. SMITH, 1998). Researchers in the English-speaking world have made most frequent use of institutional ethnography. Recent advances into and applications within the Chinese- and French-language realms are, however, noted (see Laura BISAILLON, 2012a, p.75, Note 12). [14]

Standpoint politic refers to the intent of creating "knowledge from [people's] standpoint that provides maps or diagrams of the dynamic of macrosocial powers and processes that shapes their/our lives" (D. SMITH, 1996, p.55). This perspective explicitly informs research design and decisions in institutional ethnography. Such a starting place for inquiry establishes a subject position, and it also offers an alternative starting point to "the objectified subject of knowledge of social scientific discourse" (D. SMITH, 2005, p.228). In essence, an abstract or a theoretically deterministic starting place is eschewed (FRAMPTON, KINSMAN, THOMPSON & TILLECZEK, 2006). Conventional practices of theorizing the social are understood as social practices that are "constructed within historically bounded contexts and ... applied in specific ways" (CHABAL, 2009, pp.2-3). The usefulness of beginning within the standpoint of oppressed or disadvantaged people is that this position carries the promise of revealing aspects of the social world that are invisible from other social locations (D. SMITH, 1987, 2005). [15]

Investigating from a standpoint outside of authoritative or official ways of knowing, and also outside the frame of dominant institutions (CROTTY, 1998; HOLMES, MURRAY & RAIL, 2008), is a research commitment and political decision.3) Indeed, "research that has not been commissioned by the organization [under inquiry], and is not under its control, may be seen as potentially disruptive of the smooth operation that it is aimed at" (CAMPBELL & GREGOR, 2004, p.63). In what follows, we identify and discuss consequences of our shared research decision to maintain a perspective on the side of immigrants with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) in Canada in the case of Laura BISAILLON's project, and nurses working in Canadian hospitals in the case of Janet RANKIN's work. During the course of our two year methodologically centered discussions, we coined the terms standpoint informants and extra-local informants to refer to and distinguish between our research participants (BISAILLON, 2012b). In this article, these terms are used to distinguish between people in whose interests our work was carried out (standpoint informants) and those people who were identified as playing a key function in the lives of standpoint informants (extra-local informants). [16]

4. Focus and Characteristics of the Two Projects

4.1 Immigration and HIV policy study

Laura BISAILLON (2012a) produced an exploration and critique of the organization of the Canadian immigration system and the practices associated with mandatory HIV screening within this institutional complex. She explored federal government practices associated with medical screening and assessment of prospective immigrants with HIV. She described the consequences of these practices on this group of immigrants from within the material conditions and activities of their lives. Laura BISAILLON's point of departure was early observations she made in her capacity as caseworker in an acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) service organization that served immigrant women in Canada. Reports from these women about happenings associated with an HIV-positive diagnosis during immigration procedures contrasted, sharply, with authoritative or official claims of the same procedures (BISAILLON, 2011). Laura BISAILLON wondered, "How are these knowledge claims organized as dissonant?" In the end, her research produced a corrective to the authoritative or official claims about practices and procedures associated with mandatory immigration HIV screening in Canada. [17]

Laura BISAILLON conducted two tranches of sequential fieldwork over twelve months in three Canadian cities. She first arranged interviews with HIV-positive immigrants who were her standpoint informants. In all, Laura BISAILLON interviewed thirty-three women and men who were nationals of twenty-two countries. All of these people had been mandatorily screened for HIV and were found to be living with HIV. Laura BISAILLON gathered information from many people and about a variety of HIV screening experiences because she was interested to know if and how these were organized differently in relation to where in the world the person was tested for HIV for the purposes of applying to immigrate to Canada. The problematic organizing Laura BISAILLON's project was the difficulties and contradictions experienced by prospective immigrants with HIV with state practices occurring (or not) at positive diagnosis during the immigration medical examination.4) [18]

In-person interviews with standpoint informants were conducted in informal, home-like settings. Calm settings such as homes or quiet, after-hour spaces in AIDS service organizations were places that proved conducive to listening and learning. Exchanges in these milieus were routinely longer than planned. The intimacy afforded by these sites made way for easy silence, contemplation, description, and clarification. Laura BISAILLON learned about the tensions and problems these informants experienced during their immigration to Canada. Informants were asked to bring the various documents they used as part of their immigration process to the interview. The pace of interview conversation in these milieus was relaxed, which made ample time for close review of informant texts; a meticulous and time consuming part of the research process; an experience shared by both Laura BISAILLON and Janet RANKIN. Through people's descriptions of the activities stemming from their immigration process, and the texts they used for this purpose, Laura BISAILLON learned about the intersections between the work that was required of them to immigrate and the work of a considerable range of extra-local informants. In this way, standpoint informants led Laura BISAILLON to identify extra-local informants whom she approached for an interview in the second phase of her fieldwork. [19]

Laura BISAILLON engaged in participant observation, focus groups, textual analysis and interviews to collect data (DeVAULT & McCOY, 2004; McCOY, 2006). She completed twenty-eight extra-local informant interviews during phase two of her project. Interviews with these persons generally occurred in informants' workplaces. Informants included immigration doctors, HIV physicians, social workers, refugee shelter personnel, public health workers, border services personnel, immigration and legal aid lawyers, case workers in AIDS service organizations, and government employees. All of these actors were identified as playing a key role in the immigration application process of standpoint informants (e.g., HIV screening, assessment for in/admissibility on medical grounds, adjudication of refugee claim, other). Examples of texts examined include computerized case notes, correspondence, public education materials, government presentation slides, government forms, and work manuals and guidelines, among other artifacts. [20]

Laura BISAILLON audio recorded and transcribed the sixty-one interviews. After each interview, she promptly audiotaped her observations and reflections on these sessions. She took notes on analytic threads that were useful to follow up on in subsequent interviews. This strategy complemented her extensive note taking, successfully helping her manage and offset fatigue resulting from lengthy interviews. Standpoint informant interviews were between one and three hours in length. Interviews with extra-local informants were generally shorter in duration than those conducted with standpoint informants, but Laura BISAILLON nevertheless took written notes and dictated audio recordings to herself in all cases to produce the thick, rich description that results from and is emblematic of ethnographic fieldwork in its various incarnations (BURAWOY, 2000; GEERTZ, 1983; MARCUS, 1998, 2012; MELHUUS, MITCHELL & WULFF, 2010; NGUYEN, 2010; TABER, 2010). [21]

Janet RANKIN (Janet RANKIN & Marie CAMPBELL, 2006) produced an explication of how the work of nurses employed in Canadian hospitals is socially organized. She explored the work nurses do with patients in these settings. Janet RANKIN's point of departure was the knowledge nurses have and put to use when caring for people. She investigated activities engaged in by nurse activists. Focusing on components of nurse activist work brought competing knowledge about the quality of nursing care into view. Hospital managers, administrators, and government employees understood quality in a way that was distinctly different than how nurses described quality. Moreover, there was significant difference between what happened in the material conditions of nurses' work and the facts and statistics that managers used to make decisions. Like Laura BISAILLON, Janet RANKIN set out to explore and correct, where necessary, the organization of dissonance in knowledge claims. Her research established an empirical ground for legitimizing nurses' knowledge about what occurs in their work settings. [22]

Janet RANKIN's fieldwork was also conducted in sequential tranches that were comprised of both interview and observational forms of data collection. Similar to the conduct and cadence of Laura BISAILLON's interviews with standpoint informants, Janet RANKIN's interviews with her standpoint informants were structured as relatively informal conversations. Conducted over eighteen months, participant observations with nurses included interviews that took place during and after a work shift. The substance of these interviews was recorded in field notes. Janet RANKIN interviewed eight extra-local informants including an admissions clerk; a health records manager; a nursing unit manager; two nursing executives; a chief administrative officer of a hospital; a ministry of health employee; and, finally, a health services scientist employed in a large tertiary care center. These interviews were audio recorded and selectively transcribed. Textual data were indiscriminately collected whenever and wherever they were discovered. As it turned out, some of these texts proved to be crucial data sources, while others did not contribute to analysis in a significant way. [23]

Preliminary observational work in Janet RANKIN's study began with her attendance at regularly scheduled meetings of a nurses' action group. The nurses met informally in one another's homes to discuss workplace issues of mutual concern. Janet RANKIN sat in on these gatherings, capturing exchanges in written field notes; often engaging in on one-on-one interactions with nurses. In discussions with informants, Janet RANKIN explored the forms of knowledge informants mobilized in their work practices (Janet RANKIN & Marie CAMPBELL, 2006). To this end, Janet RANKIN investigated questions such as: Why were nurses engaging in certain practices? How did they know what to do in certain circumstances? [24]

In the next phase of her fieldwork, Janet RANKIN entered nurses' work places to observe their practices. Extra-local informant interviews occurred in professional places of work. While waiting to interview extra-local informants such as nurse managers, hospital administrators, and ministry of health personnel, Janet RANKIN regularly sat in reception areas near clerical personnel. In these spaces, she watched clerks work, and paid attention to their conversations. Through such waiting and observation, Janet RANKIN's attention sharpened to the proliferating use of managerial technologies that—she was told by both standpoint and extra-local informants—were deployed with the idea of improving patient care, promoting efficiency, and fostering accountability. Like in Laura BISAILLON's work, Janet RANKIN's extra-local informants came into view iteratively as she analyzed data. Interviews with extra-local informants were sometimes difficult to arrange because these informants juggled demanding schedules that included many administrative duties. [25]

4.3 Coherence between two projects and use of texts

There was clear analytic coherence in the purpose and organization of our projects despite that they were conducted separately, during different periods of time, and that the field settings in which we collected data looked nothing alike. Ultimately, we both aimed to elucidate the workings of large, complex institutions, and to explicate their functioning. Until our projects, the institutional settings that we investigated had not previously been explored or critiqued in the way that we embarked on doing so. In taking on the social problems and struggles experienced by HIV-positive immigrants (Laura BISAILLON) and nurses (Janet RANKIN), we worked to "reorganize the social relations of knowledge of the social so that people can take that knowledge up as an extension of [their] ordinary knowledge of the ... actualities of [their] lives" (D. SMITH, 2005, p.29; italics in original). [26]

In conducting interviews for our respective projects, we followed many of the conventions expected of rigorous and ethical qualitative research practice. That is, we received ethical approval, secured informed consent, shielded the identity of our informants, and, established rapport with informants to produce focused, relevant data (CRESWELL, 2007; EAKIN & MYKHALOVSKIY, 2005; GILLIES & ALLDRED, 2002; PAWSON, BOAZ, GRAYSON, LONG & BARNES, 2003). Consistent with institutional ethnography, we paid particular attention to junctures in conversations that carried institutional language. This is because taken-for-granted features of informants' daily work practices—the quality and character of which people talk easily and casually about—hold clues about how institutions work; the very sort of information that constitutes good institutional ethnographic data. When nurses talked about producing a shift handover, for example, Janet RANKIN queried the nurses about the constituent parts of the documents they used because she knew that shift handover required time and skill. Janet RANKIN explored nurses' interactions with such a report and other texts because they provided insight into under-examined features of how the hospitals she examined worked. [27]

For both of us, an important organizer of our fieldwork was the focus on gathering information about the material conditions of informants' lives. We did this by inquiring into the empirically observable activities in which our informants regularly engaged. Importantly, this included an emphasis on informants' textual practices. From the outset in both studies, a key methodological decision was made to integrate texts into data collection and analysis. In this way, people's knowledge about how texts work was a key line of questioning in interviews. For example, Laura BISAILLON asked her informants to bring their immigration files to their interview. The significance of texts in institutional ethnography is in uncovering details about how people's textual practices are sources of data that inform about connections between sites and places that are geographically distant. [28]

In institutional ethnography, texts are analytically useful for their role as material artifacts carrying standardizing messages. Texts can include, but are not limited to, print, film, photographs, television, mass and electronic media, and radio sources (see DeVAULT & McCOY, 2004; McCOY, 1995; WARREN, 2001 for other examples of texts). Legislation, regulations, policies, and instructions are texts that came into view in our respective projects. For example, Laura BISAILLON studied Canadian government issued immigration forms and manuals, and Janet RANKIN reviewed hospital forms and electronic nursing charts in her project. [29]

Texts are integral parts of what people do every day, and in institutional ethnography, what people do with texts—their textual practice—is closely studied. In contemporary societies, texts are replicated across time and place, and they appear in many places simultaneously. This connects people's local settings with those of people outside their local, interactional world. It is the examination of this replication and coordination across time and place that is of analytic interest because an assumption is that the circulation and reproduction of texts, and the standardizing messages they carry, are key organizers of how societies work to rule and regulate people's lives. In institutional ethnography, "texts are like a central nervous system running through and coordinating different sites" (DeVAULT & McCOY, 2004, p.765). [30]

During our interviews, we sought to draw attention to how our informants integrated texts to meet the demands of their daily activities. For example, in Laura BISAILLON's project, she asked prospective immigrants with HIV to identify and discuss the range of texts they used to file an application for immigration to Canada. Janet RANKIN explored how nurses used various texts that the nurses identified as being integral to the accomplishment of their work in clinical care settings. One of the most analytically fertile interviews Janet RANKIN conducted was with a hospital manager. Her exchange with this informant took the shape of discussing how this person worked with a particular statistical reporting tool. The line of inquiry on the materiality of this person's practices focused dialogue on empirically observable details of the informant's administrative work. Understanding how people make use of texts is important because texts are understood to tell stories about how issues people discuss are framed. Texts "establish terms and concepts, and ... serve as resources that people draw into their everyday work processes" (D. SMITH, 2005, p.45). In both of our projects, we carefully explored how texts "mediate relations of ruling and organize what can be said and done" by people (p.45). [31]

5. Fieldwork Challenges (and Strategies)

5.1 Focus on material conditions

In both of our projects, a common analytic goal was to build understandings of how things happened on the ground and as people experienced them. As we found out through our fieldwork, maintaining an ontological commitment of staying focused on the material conditions of people's lives, including their textual and other practices, proved challenging to both our informants and ourselves as researchers. We argue that this is in part a function of the orientation of conventional and dominant forms of social science research, where emphasis is placed on examining informants' inner, emotive experiences; research that does not necessarily or routinely transcend the "micropolitics" of the interview setting (MYKHALOVSKIY et al., 2008, p.195). When interviews are pulled off track, valuable opportunities to explore connections between the personal, social, and political worlds we inhabit can be overlooked (LOCK & NGUYEN, 2010). We suggest that informants' propensity to veer away from the knowledge they have of the material conditions of their lives is partly because these are familiar and ordinary to them. At the same time, informants are generally more familiar with interview conventions of conventionally framed social science research.5) [32]

In both of our projects, we conceived our informants as expert knowers of the material conditions and events of their lives because "only the experiencer can speak of her or his experience" (D. SMITH, 2005, p.224). At the same time, we understood that how and what people know (including what we, as researchers, know) is also organized within discursive social relations. So, while informants know the world through their "ordinary good knowledge of how things are put together in [their] everyday lives," at the same time, they also know the world through conceptual or ideological understandings (D. SMITH, 2006, p.3).6) These latter understandings might—or might not—coincide with the actual, material conditions of their lives. Because of this, informants' accounts are not in and of themselves good accounts or evidence of how things are socially organized to happen in research using institutional ethnography. In both of our projects, therefore, we were attentive to the ideological forms and conventions of informants' speech, because resident in their language were important analytic traces of the ways in which their thinking was discursively organized. [33]

Laura BISAILLON (2012a, p.137) developed an aide memoire as an analytic device to ward off informant and researcher drifts into conceptual or ideological talk during interviews (Table 1). Therein are eight central methodological concepts connected to their analytic function. Laura BISAILLON created this tool to remind herself of the focus she needed to maintain to carry out useful institutional ethnographic work. This resource also proved helpful during her ethics application process and the write-up and analysis phases of her research.

Table 1: Characteristics of interviews using institutional ethnography [34]

To Laura BISAILLON's surprise, Table 1 proved to be further useful when endeavoring to gain access to certain extra-local informants such as government employees and health practitioners. Laura BISAILLON learned that these informants were most accustomed to reviewing an interview guide as part of their decision about whether (or not) to accept the invitation to participate in a study. In Laura BISAILLON's project, when she was asked to present an interview guide, Table 1 suited this purpose. Prospective extra-local informants understood this as a loosely formulated guide. They learned from it that the intended analytic focus of an interview with them would focus on features of their work practices and their knowledge of the organizational setting in which they worked. The research objective—unearthing details about the minutia of the informant's work to shed light on broad organizational processes and functioning—proved acceptable to the extra-local informants who accepted Laura BISAILLON's invitation to be interviewed. [35]

5.2 Dissonant knowledge claims

Interviews in both of our projects were framed within the dialogic tradition in institutional ethnography of "talking to people" (DeVAULT & McCOY, 2004, p.756) in a "familiar manner" (DeVAULT, 1990, p.99). The lines of inquiry that we pursued in interviews were shaped by the standpoint we maintained on the side of immigrants with HIV (Laura BISAILLON) and nurses (Janet RANKIN). In neither project was standpoint politic explicitly discussed with informants. Nevertheless, a particular tone was shaped by the presence of this politic; fashioned by the concepts in Table 1. The organizing presence of a standpoint politic also meant that standpoint and extra-local interviews were substantively different. For example, standpoint and extra-local interviews were positioned differently within the knowledge relations about what happens through mandatory immigration HIV screening procedures and activities involved in nurses' clinical work. Immigrant persons physically undergo an HIV test and nurses physically do the work of nursing; their knowledge of what is involved is embodied, experiential, and daily; filled with the subjective expertise of being there. [36]

In contrast, the knowledge about the same practices that government immigration medical officials and hospital administrators hold, respectively, is arms length to the everyday practices and experiences of immigrants and nurses; their knowledge mediated by how these practices are described or "written up" in reports (DARVILLE, 1995, p.254). A "yes" to the question "Was HIV counseling provided?" on a government form submitted by an immigration doctor, for example, becomes evidence that counseling practices occurred (even where standpoint informants in Laura BISAILLON's project reported the systematic absence of counseling). What has occurred in this case is a transformation and abstraction of lived experience. Authoritative or official reports that HIV test counseling practices actually occur in professional practice are made possible through these sorts of textual responses on forms; despite that there is no empirical ground for such claims as per Laura BISAILLON's findings. Similarly, what a nurse in direct practice knows about the needs of patients is different than how a hospital administrator understands the same needs; the latter "written up" in reports as measurements of time and labor costs detailing lengths of stay and hospital wait times (DARVILLE, 1995, p.254). [37]

When a line of interview conversation with an extra-local informant pointed to dissonance in knowledge between their understandings and those of standpoint informants, this created tensions. For example, in dialogue with a hospital administrator, Janet RANKIN was assured that recent (at the time) integration of hospital departments delivering pharmacy, dietary, and physical and occupational therapy services had not, to quote the informant directly, " impacted on nursing very much." However, Janet RANKIN's fieldwork with nurses, and the analysis she generated, showed how nurses did, actually, and in practice, adapt their work activities in response to the hospital's organizational restructuring efforts. Similarly, it was difficult for Laura BISAILLON to confront her extra-local informants with the flaws she identified in the way HIV test counseling was carried out (or not). It was during such contradictory moments that the standpoint politic was readily palpable, and the interviews were difficult to navigate. In some instances, Janet RANKIN and Laura BISAILLON explained to extra-local informants the basis for dissonant knowledge claims. [38]

5.3 Following analytic threads and gaining access

Based on our fieldwork experiences during interviews, we note the frequency with which accounts of how things occur on the ground do not match authoritative, official or "speculative accounts" about the same (G. SMITH, 1990, p.635). When this is the case, the researcher must be ready to deploy particular sets of skills, because such dissonance in knowledge will, in our experience, be contested. These can produce tensions that stand to threaten the research process unless the researcher is mindful of such a possibility. The matter of how to gather information about dissonant forms of knowledge while at the same time circumventing defensive exchanges with informants deserves close attention. As identified and discussed below through an example from each of the two studies, such challenges might also be highly instructive and analytically relevant: they provide insights into how the institutional settings under scrutiny are organized and coordinated to function. [39]

The example of how Laura BISAILLON went about gaining entry into offices where doctors involved in carrying out immigration HIV screening—as prospective extra-local informants—provided her with useful insights into how these institutional settings were organized. The letters of introduction and consent forms associated with Laura BISAILLON's project were, as it turned out, difficult to circulate prior to interviews. This was because the medical world in Canada relies largely on fax transmission of texts; something she did not know or plan for in advance of heading into the field. Most physicians she planned to interview were unaccustomed to e-mail communication (at least for professional purposes in this context). Laura BISAILLON puzzled over this apparently old-fashioned adherence to hardcopy texts. Direct communication with physicians was rarely possible because administrative assistants were skilled at prioritizing texts for physician attention. Additionally, because Laura BISAILLON acknowledged that her project represented yet another form of work for the doctor, she found that her study was, at times, a difficult "sell" to prospective interviewees. In sum, the matter of acquainting physicians with her project proved challenging for Laura BISAILLON. While she was initially inconvenienced, as her fieldwork advanced, Laura BISAILLON acknowledged that the textual practices of extra-local informants—both prospective and eventual—offered insights (and opportunities for exploration) into the organization of their workplaces and day-to-day working conditions. [40]

Like Laura BISAILLON, Janet RANKIN's immersion in the hospital in which she conducted interviews and engaged in participant observation afforded her opportunities for learning about how the site was organized. In particular, from the early inception of her project, Janet RANKIN faced challenges communicating with extra-local informants who occupied senior administrative positions in the hospital. Janet RANKIN's fieldwork took place during a time where there was broad reorganization of the hospital's nursing services. Changes in the way things were run in the facility resulted in frequent staff turnover. Janet RANKIN's standpoint informants led her to extra-local informants who played defining roles in their direct nursing practice. However, more than once when she attempted to contact these informants, they had left the job. Due to such changes, Janet RANKIN had difficulty following through on the clues that she had picked out of her interviews and observations with nurses. At first she experienced these barriers as frustrating delays and setbacks in the research. However, once she recognized that the managerial turnover was integral to the reorganization of the hospital's nursing services Janet RANKIN framed the challenges as data and used that to inform further data collection and analysis. [41]

5.4 Tense interviews and the standpoint politic at work

During a difficult to arrange interview Janet RANKIN carried out with a senior administrator in the primary research hospital where she collected the bulk of her observational data, the politics and tensions stemming from the institution's restructuring process impacted on the cadence and content of the interview. This threatened to entirely jeopardize her study. The senior administrator being interviewed was the person who had approved Janet RANKIN's access to research in the hospital. Janet RANKIN's university ethics clearance stipulated that this administrator must vet all institutional texts—such as statistical records and policies—cited in Janet RANKIN's analysis. Before meeting with this extra-local informant, Janet RANKIN had secured a copy of a consultant's report that reviewed the restructuring of nursing services in the hospital. Janet RANKIN set out to discuss the report's findings and recommendations. As such, she introduced the report as a topic of discussion with the senior administrator in an effort to seek permission to use the document as a data source. [42]

To Janet RANKIN's surprise, rather than learning more about the report and being given permission to use it as data, she found herself being interrogated about her study design and procedures. Her approval to research in the hospital was officially revisited from this point. Janet RANKIN's position on the side of her nurse informants placed her outside of authoritative or official knowledge claims that the administrator was vested in upholding. Janet RANKIN's line of questioning had inadvertently made the administrator uncomfortable. This informant understood Janet RANKIN's project to be "making trouble" for and of potential harm to the hospital. [43]

Shortly after their interview, the administrator, who was positioned as gatekeeper, resigned from his professional functions. Janet RANKIN worked more effectively with this person's replacement by cultivating a collaborative relationship. This informant approved Janet RANKIN's use of the consultant's report in her study. After some thought, Janet RANKIN reasoned that this scenario, which brought with it considerable tension and challenge, was analytically meaningful to her analysis. Along with the rapid turnover of managers, this interview crisis offered enormous insight into the precarious positioning of nursing administrators. This experience supported Janet RANKIN's understanding of the tensions generated by reorganizations in health care. [44]

This example from Janet RANKIN's project serves to illustrate frustrations and sensitivities that can be associated with collecting data from persons who hold senior positions in large and hierarchical bureaucracies. If Janet RANKIN had not succeeded in dealing with the challenges discussed above, she would have had to forgo the opportunity to use an important source of data. Perhaps even more troubling was that the research could have been jeopardized had access to the hospital been revoked. As a result of this experience, Janet RANKIN became increasingly attuned to how a person's social location shapes what she or he can know and say about the world. In extra-local informant interviews subsequent to the one showcased here, Janet RANKIN took care to inquire about informants' work practices with greater authenticity and empathy. She did so with a newfound realization and sensitivity that—like the nurses whose standpoint she maintained—senior administrators face socially organized workplace challenges, including competing professional demands, budget cutbacks, and various accountability measures. [45]

As our fieldwork among extra-local informants progressed over time, both of us gained understandings of workplaces challenges faced by well-intentioned administrators. We paid particular analytic attention to these challenges that were products of the professional roles these informants fulfilled, and the social locations they occupied. [46]

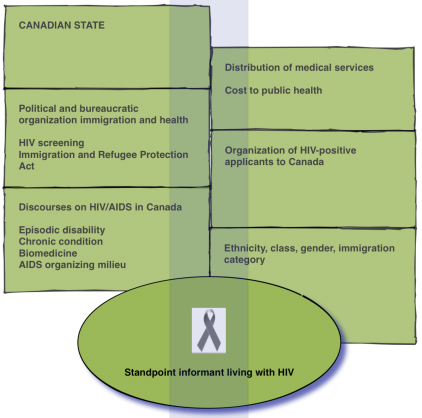

A device that Laura BISAILLON (2012a, p.153) created to support fruitful interviews with extra-local informants is the pictorial representation of her project depicted in Figure 1. The illustration shows the standpoint of HIV-positive immigrants to Canada and the numerous "institutional fields" that circulate and organize them (McCOY, 2006, p.113). This diagram, an adaptation from Dorothy SMITH (2006, p.3), proved useful in conversations with extra-local informants who were reluctant to participate in her study, and/or who wanted additional details about the project's aim. An example of how Laura BISAILLON deployed the tool was in an interview with a caseworker in an AIDS service organization serving non-white persons who was hesitant to support Laura BISAILLON's access. This person explained that members of "her" community, to quote her directly, that is, non-white persons living with HIV, had been amply researched. She expressed skepticism about Laura BISAILLON's motivation for conducting research among people of color living with HIV given that Laura BISAILLON is white and, the informant assumed, not living with HIV. The informant questioned Laura BISAILLON's knowledge about issues faced by people living with HIV, and queried her proposed uses of findings. The caseworker was concerned that results might have negative consequences on and for immigrant persons with HIV in Canada.

Figure 1: Standpoint informant diagram in Laura BISAILLON's study [47]

The watershed moment in securing this informant's participation in her project was when Laura BISAILLON showed her Figure 1. The illustration provided a material basis for a detailed exchange about the study and its method of inquiry. It became clear that the informant understood the project through her own understandings of participatory action and community-based research frameworks (though Laura BISAILLON was clear that her research was not within these traditions). Ultimately, the pictorial helped this caseworker make sense of Laura BISAILLON's research on her own terms, which presumably shaped her decision to participate. In other interview settings, too, standpoint and extra-local informants with various literacy, language skills, and educational training reported relating well to the associations they discerned from the diagram's colors, shapes and text that gestured to relationships under study. [48]

In preparing Figure 1, Laura BISAILLON made use of normative or dominant discourses circulating in Canada relating to immigration, the law, HIV, and the organization of health care and service delivery. She knew how to do this because she had learned about the discursive properties of each in academic, advocacy, and research milieus. Laura BISAILLON's knowledge and the "organizational literacy" it informed supported the success of extra-local informant interviews she conducted (DARVILLE, 1995, pp.254-257). She also sometimes used these discourses as a tactic to engage informants in conversation. For example, when the AIDS service organization caseworker referred to above asked Laura BISAILLON what she knew about issues facing non-white immigrants with HIV in Canada, Laura BISAILLON talked about numerous concepts including vulnerability; anti-oppression, anti-colonial, and anti-racist frameworks; and, stigmatization, marginalization, and discrimination. In proceeding in this way, Laura BISAILLON deliberately situated topical issues within discursive traditions familiar to this informant because they were in active circulation in the organizational environment in which this informant worked. [49]

6. Unexpected Opportunities (and Challenges) for Collecting Data

Both Laura BISAILLON and Janet RANKIN pursued analytic clues or threads that presented serendipitously during data collection. We framed these clues as opportunities to more fully understand the functioning of the institutions and organizations we set out to explicate. An objective of research using institutional ethnography is to gain understanding about the activities that people undertake in the day-to-day conduct of their lives, and participant observation opens up opportunities for in situ learning about features of people's lives in ways that are not possible in orchestrated and manicured interview settings. Observational work has the researcher experience people in direct interaction within the institutions that are the subjects of investigation and analysis. Sociologist Timothy DIAMOND suggests, "in insisting on bodies being there, [we are sensitized] to bodies as part of the data ... It's not about just words, but [about] how the words live in embodied experience" (in DeVAULT & McCOY, 2004, p.758). The point is that in institutional ethnography, people's physical actions and everyday social conditions are important sources of data. As such, it is useful for the researcher to cultivate a generous conception of what constitutes data and move beyond what anthropologist Inger SJØRSLEV calls "ethnography by appointment" (MITCHELL, 2012, p.9). [50]

Observations of people as they went about their situated, interactional, and everyday work routines had the advantage of providing both of us with data to support later stage interviews that were conducted more knowingly and with sharper analytic acumen as a result. In some cases, observational opportunities arose from personal relationships that existed before we embarked on our research. At other times, opportunities for observational work presented during the period of time we carried out interviews and other observations. To include additional field sites in the fieldwork, Laura BISAILLON and Janet RANKIN made re-applications for ethical approvals to their respective universities. From her institution's ethics board, Laura BISAILLON obtained permission to spend observational time in immigration hearing rooms, HIV clinics, and immigration and legal aid offices, for example. Therein she considered the physical space and conversed with people working there; gathering data about the features of the social organization of people's work life. [51]

Janet RANKIN sought ethics re-approval to include conversations with nurses, observations of nursing care work, and texts that came to her attention during an unplanned set of circumstances as data sources in her project. The unexpected circumstance was the hospitalization of a relative. Janet RANKIN accompanied her relative during this hospitalization, and during this time, she maintained a journal cataloguing experiences related to the organization of patient care. After her discharge from hospital, Janet RANKIN's relative received survey materials in the mail on which Janet RANKIN did textual analysis. This included two formal interviews: one with a nursing manager, and the second with the author and administrator of the survey. Janet RANKIN's analysis of these survey texts was the material basis and starting point for interviews with these two informants through which she garnered data about how the tool was developed and deployed (Janet RANKIN, 2003; Janet RANKIN & Marie CAMPBELL, 2006). [52]

Parallel to and complementing participant observation, we both paid analytic attention to interactions situated within the fieldwork process itself. To illustrate this, we discuss two examples related to the organization of time or what we identify as waiting work; reflecting on the consequences of these arrangements for our respective projects. [53]

To interview extra-local informants, Laura BISAILLON often found herself waiting in the same waiting rooms that her standpoint informants had described waiting in to see the same persons. It was not uncommon for Laura BISAILLON to be seated in the same chair and on the same side of an immigration physician's desk as her standpoint informants, as per their accounts to her, for example. The materiality of this positioning—within similar social relations that organized both standpoint informants' and her own actions—was particularly noticeable in the offices of health practitioners such as social workers, HIV specialists, and immigration doctors. In these locations, Laura BISAILLON, like her standpoint informants, had to (learn to) conduct herself in a highly disciplined way in what were securitized, formal, and regimented settings that included examining rooms in hospitals and waiting rooms in federal immigration offices.7) [54]

As discussed, Laura BISAILLON engaged in considerable effort to communicate with extra-local informants, and this was particularly the case with physicians. As she came to find out, challenges she faced in successfully communicating with these practitioners matched standpoint informants' descriptions of challenges they also faced with these same persons. When an interview with an extra-local informant physician was delayed, canceled, or pre-empted, like her standpoint informants before her, Laura BISAILLON was faced with negotiating a new appointment with office administrators. Here again, Laura BISAILLON realized that these were some of activities that standpoint informants had talked to her about having to do to succeed in seeing practitioners. In the end, negotiating the logistics of date, place, and time of interviews and participant observations required that Laura BISAILLON negotiate with administrative personnel who proved to be highly skilled at mediating her access to extra-local informants. Laura BISAILLON had not anticipated that data collection with extra-local informants would require such patience and persistence. [55]

Through time and immersion in the field, Laura BISAILLON recognized that there was analytic value in paying close attention to the situations and surroundings where her extra-local interviews were conducted. When she was asked to wait in reception areas; invited into workplace lunchrooms; guided through a federal immigration office; introduced to senior decision-makers; and ushered into professional worksites, Laura BISAILLON saw these as important moments to pay close ethnographic attention to what happened in these places. This was because what people did there provided clues about the organization of the broader institution. After making this connection, and with this understanding, Laura BISAILLON took detailed field notes on what receptionists did; where public health educational materials were placed; what memos were posted on hospital lunchroom bulletins (and what they instructed). She did this because from these texts, in addition to revealing clues about workplace organization, there was something to be gleaned about how the work of people employed in these sites was coordinated. [56]

The following excerpt from Laura BISAILLON's (2012a) field notes relates details of her visit to Canadian immigration offices. These reflections supported a strong material basis for various lines of inquiry, which were possible because of observational work.

"Some of the most useful ethnographic observations from the ten minute or so walkabout tour came from sources other than human interaction. For example, in rounding a corner in the Health Management Branch office, my guide and I came nose-to-nose with stack after stack of immigration application files. In that instant, because of the visual impact of the thousands of catalogued files, it occurred to me just what a huge and hugely regulated machine Citizenship and Immigration Canada is. I became aware of just how extensive and complex an institutional world I had entered. I wondered: Is how things get done in this workplace, in direct association and connection with the many Canadian immigration offices around the world, as mysterious to employees as it is to the standpoint and extra-local informants I interviewed who are baffled by the internal working of this department?" (p.200) [57]

6.2 Busy-ness and pragmatics of professional time

A characteristic that distinguished standpoint from extra-local informant interviews was what we term the "pragmatics of professional time" (Laura BISAILLON, 2012a, p.149). These pragmatics shaped interviews in ways that were sometimes frustrating for us both. At the same time, they provided insights into the organization and dynamics of the institutional sites in which we were immersed. Within the pressures of scheduling among professionals, time routinely took on a distinct character and urgency in extra-local informant interviews. For example, an HIV physician Laura BISAILLON interviewed glanced at his watch every few minutes during their interview. A standpoint informant who was a patient of this same doctor had described to her a similar experience with this physician saying, to quote him directly, "Something that made me uncomfortable was that the doctor was looking at his watch while he was dealing with me." [58]

Perhaps related to the exigencies of scheduling, extra-local informants seemed less consistently engaged during interviews Laura BISAILLON conducted as compared to interviews with standpoint informants. In general, time pressed down considerably on interviews with extra-local informants. Because of this, Laura BISAILLON managed and navigated extra-local and standpoint informant interviews quite differently. For example, she was more conscious of choosing deliberate lines of inquiry with the former because her time with them was, in general, quite hemmed. It happened that interviews with extra-local informants scheduled to be one-hour in length, for example, were unexpectedly compressed, either because the informant responded to a sudden request from a colleague, or the informant's timetable was revised from when Laura BISAILLON negotiated the logistics of the interview; something she only learned about on presenting at the informants' place of work. [59]

Laura BISAILLON paid close attention to the ways in which extra-local informants talked about their work schedules. She learned that within the competing demands on extra-local informant time—research, clinical practice, university teaching, administration, community involvement, and advocacy—there resided avenues for relevant inquiry. And, while the inconvenience of curtailed interviews, and the demands on extra-local informants time, initially seemed outside of the scope of her project, Laura BISAILLON came to recognize that she was experiencing the tightly choreographed character of carrying out fieldwork among professionals who self-described as busy. Their self-descriptions using this adjective were commonplace, officious, and distinctly dissimilar to the language standpoint informants used to self-describe. (Although, as Laura BISAILLON's findings show, her standpoint informants led equally busy lives to those of extra-local informants.) This difference was analytically interesting because it points out the ways in which standpoint and extra-local informants are organized differently within the social relations of appointments and waiting. A challenge and objective in Laura BISAILLON's analysis, therefore, was to unpack and explicate how informants' busy-ness was socially organized. [60]

In this article, we presented insights that resulted from our discussions and reflections over the last two years about characteristics and challenges associated with fieldwork using institutional ethnography. We extended the existing methodological literature by focusing on the specific matter of how the politics embedded in a standpoint position shapes fieldwork in institutional ethnography. The central argument we develop is that the standpoint politic, an integral feature of the method of inquiry, gives rise to particular fieldwork challenges. This is an empirically supported argument that draws on experiences and insights from our interview, participant observation, and textual analysis fieldwork. [61]

We began our investigations into the organization of the Canadian immigration system (Laura BISAILLON) and the organization of nursing work (Janet RANKIN) by learning from people who know what the everyday practices involved in doing this work entails: our standpoints informants. This starting point—both a research technique and a political position—produced fieldwork challenges that were shaped by features of the organization of our research practices. These challenges also took shape in relationship to our epistemological claims (standpoint) and ontological commitments (focus on the material conditions of people's lives). [62]

In response to the fieldwork challenges explored in this article, we modified features of our projects and research processes to take advantage of unexpected opportunities for collecting data. For example, Laura BISAILLON developed a working tool listing key analytical methodological concepts, which served as an aide memoire. She also developed a pictorial explaining the conceptual organization of her project. This proved helpful for fieldwork and analysis. We encourage researchers using institutional ethnography to integrate these devices into their fieldwork practice. Beyond their usefulness in Laura BISAILLON's project, these tools underscore the point that innovation and adaption are necessary ingredients of fieldwork practice. [63]

There are generalizing effects of the standpoint politic that organizes fieldwork in institutional ethnography. It is likely that other researchers who use this approach will see their fieldwork organized in similar ways. Prior to immersing in fieldwork, we suggest that it is relevant for researchers to reflect on this organization and to give thought to the strategies to address these challenges. Zeroing in on fieldwork challenges can support those who use institutional ethnography as they convert unexpected frustrations and tensions in fieldwork into productive sources of data to develop and support strong lines of analysis; expanding what can be said about how complex and organizationally opaque institutions work. By reflecting critically on and appraising the organization of the approaches that guide us, we contribute to the task of sidestepping orthodoxy or fetishism of social science research practice. [64]

We thank the informants who took part in our projects. We are grateful to members of the McGill Qualitative Health Research Group and two anonymous reviewers for their feedback on drafts of this article. Laura BISAILLON thanks Laurie CLUNE for earliest discussions about some of the issues explored herein. Laura BISAILLON disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research reported in this article: Canadian Institutes of Health Research [grant number 200810IDR-198192-172991] and les Fonds de la recherche en santé du Québec [grant number 16588].

1) Laura BISAILLON presented "Dialogue Differences in Disability: Interviews with Primary and Secondary Informants" as an early version of this article in Janet RANKIN's panel at the Society for the Study of Social Problems Annual Meeting on August 15, 2010, in Atlanta, Georgia, USA. <back>

2) To explicate is to describe peoples' practices that are usually obscure. In doing this, new and explicit forms of knowledge are generated. The explication of ruling relations as found in the data is the goal of an institutional ethnography (see Marie CAMPBELL & Frances GREGOR, 2004, pp.8 and 86). <back>

3) Authoritative or official knowledge describes a process of knowing produced and sanctioned by an authority, which can include a governing body such as the state, among other actors. <back>

4) A problematic is a problem arising in relations between people and the world, where the problem resides in the manner in which the social world is organized. The problematic shaping an institutional ethnographic inquiry becomes evident to the researcher through her or his immersion in the field. A problematic "organizes inquiry into the social relations lying 'in back of' the everyday worlds in which people's experience is embedded" (D. SMITH, 1981, p.23). <back>

5) In a same line of thought, sociologist Marjorie DeVAULT (1990) noted that in her research building from Dorothy SMITH's sociological approach, her informants "were prepared to translate [their talk] into the vocabulary they expected from a researcher, and [they were] surprised that we were proceeding in a more familiar way [within interview dialogue]" (p.99). <back>

6) In this usage, ideology is a form of knowledge that is uprooted from the social circumstances in which it was produced. As per Mikhail BAKHTIN's (1981 [1975]) understanding of this idea, our use "is not to be confused with its politically oriented English cognate. [I]t is simply an idea-system" (p.429). <back>

7) In a discussion about fieldwork practices, anthropologist Jon MITCHELL (2012) refers to this process through which a researcher adapts to and learns about common social practices in a particular milieu as "social learning" (p.5). The researcher does this to "fit in" and better understand what happens in the particular setting (p.5). <back>

Bakhtin, Mikhail (1981 [1975]). The dialogic imagination: Four essays by M.M. Bakhtin (ed. by M. Holquist, trans. by C. Emerson & M. Holquist). Austin: University of Texas Press.

Bisaillon, Laura (2011). Mandatory HIV testing and everyday life: A look inside the Canadian immigration medical examination. Aporia, 3(4), 5-14, http://www.oa.uottawa.ca/journals/aporia/articles/2011_11/Bisaillon.pdf [Accessed: November 12, 2012].

Bisaillon, Laura (2012a). Cordon sanitaire or healthy policy? How prospective immigrants with HIV are organized by Canada's mandatory HIV screening policy. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, http://www.ruor.uottawa.ca/en/handle/10393/20643 [Accessed: November 12, 2012].

Bisaillon, Laura (2012b). An analytic glossary to social inquiry using institutional and political activist ethnography. International Journal of Qualitative Methods (in press).

Burawoy, Michael (2000). Introduction: Reaching for the global. In Michael Burawoy, Joseph Blum, Sheba George, Zsuzsa Gille, Teresa Gowan, Lynne Haney, Maren Klawiter, Steven Lopez, Seán Ó Riain & Millie Thayer (Eds.), Global ethnography: Forces, connections, and imaginations in a postmodern world (pp.1-40). Berkeley: University of California Press.

Burawoy, Michael (2009). The extended case method: Four countries, four decades, four great transformations, and one theoretical tradition. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Campbell, Marie (2010). Institutional ethnography. In Ivy Bourgeault, Robert Dingwall & Ray de Vrier (Eds.), The Sage handbook of qualitative methods in health research (pp.497-512). Los Angeles: Sage.

Campbell, Marie & Gregor, Frances (2004). Mapping social relations: A primer in doing institutional ethnography. Walnut Creek: AltaMira Press.

Campbell, Marie & Manicom, Ann (Eds.) (1995). Knowledge, experience, and ruling relations: Studies in the social organization of knowledge. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Carroll, William (2006). Marx's method and the contributions of institutional ethnography. In Cecile Frampton, Gary Kinsman, Andrew Thompson & Kate Tilleczek (Eds.), Sociology for changing the world: Social movements/social research (pp.232-245). Black Point: Fernwood Press.

Chabal, Patrick (2009). Africa: The politics of suffering and smiling. London: Zed Books.

Clough, Patricia (1993). On the brink of deconstructing sociology: Critical reading of Dorothy Smith's standpoint epistemology. Sociological Quarterly, 34(1), 169-182.

Clune, Laurel (2010). When the injured nurse returns to work: An institutional ethnography. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Toronto, Ontario, Canada, https://tspace.library.utoronto.ca/bitstream/1807/29519/1/Clune_Laurel_A_201106_PHD_thesis.pdf [Accessed: November 12, 2012].

Creswell, John (2007). Qualitative inquiry and research design. Choosing among five approaches (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Crotty, Michael (1998). Positivism: The march of science. In Michael Crotty, The foundations of social research: Meaning and perspective in the research process (pp.18-42). London: Sage.

Dale, Craig; Angus, Jan; Sinuff, Tasnim & Mykhalovskiy, Eric (in press). Mouth care for orally intubated patients: A critical ethnographic review of the nursing literature. Intensive and Critical Care Nursing, 28(6).

Darville, Richard (1995). Literacy, experience, power. In Marie Campbell & Ann Manicom (Eds.), Knowledge, experience and ruling relations: Studies in the social organization of knowledge (pp.249-262). Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

DeVault, Marjorie (1990). Talking and listening from women's standpoint: Feminist strategies for interviewing and analysis. Social Problems, 37(1), 96-116.

DeVault, Marjorie & McCoy, Liza (2004). Institutional ethnography: Using interviews to investigate ruling relations. In Jaber Gubrium & James Holstein (Eds.), Handbook of interview research: Context and method (pp.751-776). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Deveau, Jean Louis (2012). Workplace accommodation and audit-based evaluation process for compliance with the Employment Equity Act: Inclusionary practices that exclude. An institutional ethnography. Canadian Journal of Sociology, 36(3), 151-172, http://ejournals.library.ualberta.ca/index.php/CJS/article/view/10479/9018 [Accessed: November 12, 2012].

Dobson, Stephan (2001). Introduction. Studies in Cultures, Organization and Societies, 7(2), 147-158, doi 10.1080/10245280108523556.

Eakin, Joan & Mykhalovskiy, Eric (2005). Teaching against the grain: The challenges of teaching qualitative health research in the health sciences. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 6(2), Art. 42, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs0502427 [Accessed: September 23, 2012].

Frampton, Caelie; Kinsman, Gary; Thompson, Andrew & Tilleczek, Kate (Eds.) (2006). Sociology for changing the world: Social movements/social research. Black Point: Fernwood Press.

Geertz, Clifford (1983). Local knowledge: Further essays in interpretive anthropology. New York: Basic Books.

Gillies, Val & Alldred, Pam (2002). The ethics of intention: Research as a political tool. In Melanie Mauthner, Maxine Birch, Julie Jessop & Tina Miller (Eds.), Ethics in qualitative research (pp.32-52). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Grahame, Peter & Grahame, Kamini (2009). Points of departure: Insiders, outsides, and social relations in Caribbean field research. Human Studies, 32(3), 291-312, doi 10.1007/s10746-009-9121-5.

Guba, Egon & Lincoln, Yvonna (1994). Competing paradigms in qualitative research. In Norman Denzin & Yvonna Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (pp.105-117). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Holmes, Dave; Murray, Stuart & Rail, Geneviève (2008). On the constitution and status of "evidence" in the health sciences. Journal of Research in Nursing, 13(4), 272-280.

Lock, Margaret & Nguyen, Vinh-Kim (2010). An anthropology of biomedicine. West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell.

Making Care Visible Research Group (Michael Bresalier, Loralee Gillis, Craig McClure, Liza McCoy, Eric Mykhalovskiy, Darien Taylor & Michelle Webber) (2002). Making care visible: Antiretroviral therapy and the health work of people living with HIV/AIDS, http://chodarr.org/sites/default/files/chodarr1501.pdf [Accessed: November 12, 2012].

Mann, Susan & Kelley, Lori (1997). Standing at the crossroads of modernist thought: Collins, Smith, and the new feminist epistemologies. Gender & Society, 11(4), 391-408, doi 10.1177/089124397011004002.

Marcus, George (1998). Ethnography through thick and thin. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Marcus, George (2012). Notes from within a laboratory for the reinvention of anthropological method. In Marit Melhuus, Jon Mitchell & Helena Wulff (Eds.), Ethnographic practice in the present (pp.69-79). New York & Oxford: Berghahn Books.

Marx, Karl & Engels, Frederick (1970 [1846]). The German ideology, Part 1. New York: International Publishers.

McCoy, Liza (1995). Activating the photographic text. In Marie Campbell & Ann Manicom (Eds.), Knowledge, experience and ruling relations (pp.181-192). Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

McCoy, Liza (2006). Keeping the institution in view: Working with interview accounts of everyday experience. In Dorothy Smith (Ed.), Institutional ethnography as practice (pp.109-126). Oxford: Rowman & Littlefield.

McCoy, Liza (2008). Institutional ethnography and constructionism. In Jaber Gubrium & James Holstein (Eds.), Handbook of constructionist research: Context and method (pp.701-714). New York: Guilford Press.

Melhuus, Marit; Mitchell, Jon & Wulff, Helens (Eds.) (2012). Ethnographic practice in the present. New York: Berghahn Books.

Mitchell, Jon (2012). Introduction. In Marit Melhuus, Jon Mitchell & Helena Wulff (Eds.), Ethnographic practice in the present (pp.1-15). New York: Berghahn Books.

Mykhalovskiy, Eric (2001). Troubled hearts, care pathways and hospital restructuring: Exploring health services research as active knowledge. Studies in Cultures, Organizations and Societies, 7(2), 269-296, doi 10.1080/10245280108523561.

Mykhalovskiy, Eric & McCoy, Liza (2002). Troubling ruling discourses of health: Using institutional ethnography in community-based research. Critical Public Health, 12(1), 17-37.

Mykhalovskiy, Eric; Armstrong, Patricia; Armstrong, Hugh; Bourgeault, Ivy; Choiniere, Jackie; Lexchin, Joel; Peters, Suzanne & White, Jerry (2008). Qualitative research and the politics of knowledge in an age of evidence: Developing a research-based practices of immanent critique. Social Science and Medicine, 67(1), 195-203, doi 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.03.002.

Nguyen, Vinh-Kim (2010). The republic of therapy. Triage and sovereignty in West Africa's time of AIDS. Durham: Duke University Press.

Pawson, Ray; Boaz, Annette; Grayson, Lesley; Long, Andrew & Barnes, Colin (2003). Types and quality of knowledge in social care. London: Social Care Institute for Excellence, http://www.scie.org.uk/publications/knowledgereviews/kr03.pdf [Accessed: November 12, 2012].

Rankin, Janet (2003). "Patient satisfaction": Knowledge for ruling hospital reform. An institutional ethnography. Nursing Inquiry, 10(1), 57-65.