Volume 13, No. 2, Art. 27 – May 2012

A Methodological Approach to the Study of Urban Memory: Narratives about Mexico City

Martha de Alba

Abstract: This article serves a dual purpose. On the one hand, I seek to understand social representations and the collective memory of a sample of older adults, resident in the metropolitan area of Mexico City. On the other hand, I wish to reflect on the methodology used to achieve that objective, placing special emphasis on the combination of two complementary techniques: Atlas.ti, a tool used to carry out a semantic analysis of the interviews, and Alceste, a program that makes it possible to observe a classification of the terms used by respondents based on a statistical analysis of co-occurrences.

The article is structured in the following order. Firstly, I explain the theoretical presuppositions that sustain the study. Secondly, I look at the methodology used, the reasons why I decided to use the software in question, and the analysis strategies for the interviews. Finally, I present the results obtained, and close with a final discussion on the relevance of the general methodology of the study for analyzing urban memory.

The results indicate different levels of analysis of extensive narratives about the past experience of a great city like Mexico City; from the individual level that allows Atlas.ti up to a collective level (gender differences, location or socioeconomic status) that prioritizes Alceste. I discuss the limitations of these software tools to analyze experiences that have continuity in time and space, as well in the incorporation of space as a complex category of analysis.

Key words: urban memory; Mexico City; sociospatial representations; life course; elderly; qualitative computing

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. Social Representations, Collective Memory and Urban Experience

3. Subject/Object of Representation: The Elderly and the City

4. Method: Studying the Subjective Aspects of the City and the Life Trajectories

4.1 Interview guide

4.2 Respondents and their neighborhoods

5. Combining Atlas.ti and Alceste Software: A Complementary Text Analysis

5.1 Atlas.ti: A tool for thematic analysis

5.2 Alceste: Analysis of the co-occurrences of the statements in a text

5.3 Urban modernization versus sociocultural life of the city

5.4 Urban modernization and daily mobility

5.5 Nostalgia for the sociocultural life of the city: Youth, consumption and family

6. Final Discussion

1. Introduction1)

The purpose of this article is to make a methodological exploration in regard to the combination of software tools, such as Atlas.ti and Alceste, in order to study urban memory in elderly people in an effort to answer the following questions: How these methods contribute to analyze narratives about ancient experiences of the cities? What are their limits approaching psychosocial processes that have continuity in time and space, as the memory of life in a big city? [1]

I will present some results of a qualitative study (in narratives of the city) conducted with 40 elderly adults over 60 years, residing in four neighborhoods of the metropolitan area in Mexico City. The main objective was to analyze urban collective memory, the experiences and social representations of the people who have lived in this city for the last five or six decades. [2]

Before tackling the methodological aspects and the strategies of analysis, I will define concepts basic to the study, such as the notion of experience, the representation, and the memory of the city that I used in the research. [3]

2. Social Representations, Collective Memory and Urban Experience

The social representations (MOSCOVICI, 1961) of space (MILGRAM & JODELET, 1976) allow to understand the meanings of places, according to the characteristics of the social identity of the actor, who can take different positions in the social structure. In that matter, space as an object of social representation involves the knowledge of the essential characteristics of the territory analyzed, as well as the individuals or social subjects that constructs that representation, according to their interrelationship (their occupational shape, legal status in relation to space in question, etc.). [4]

In this way, the focus resides on the elderly people's representations of the city. These representations differ in regard to different positions in the social structure (socioeconomic status), places of residence (located in the center and periphery neighborhoods), and value patterns associated with gender differences. The social status, geographic location, and gender differences are the anchors and, according this theory, restrict the construction of the representations of individuals. [5]

The relationship between social representations and practices should be seen as dialectic and changing over time. Our ideas support, generally, our actions, while we can enrich our thought system. In the case of territory, social practice makes reference to the uses that individuals and groups make of spaces and social the inner activities. I use the term "experience" instead of "practice" to denote the set of behaviors and uses of space, as actions, taking their definition in the context of the meanings that space and actions have for the social subjects occupying it. [6]

The concept of experience, in this case, relates to the phenomenology of the everyday life of SCHÜTZ (1962), not only by the fact that the action is significant, but because, for SCHÜTZ, the everyday accumulated experience constitutes the knowledge roots and the biographical situation of the subject, the main starting point for their location in the world (physical and social) and their interpretation. We could say that the experience is going to be integrated by the social representational system of the subject through his life. Nonetheless, in SCHÜTZ's case, the social representations, such as sociocultural determinants, are handled by the subject according to the manner in which he/she is located in the here (spatial) and now (temporality). An individual plans his/her actions in the world based upon the interpretations they make of that world, which are deeply embedded in their particular biographical context, meaning cultural background, accumulated experiences, pre-established patterns of action, social position, means of social learning, etc. [7]

In this research, in particular, I would say that each person has constructed social representations of the city from several sources (other social representations, specialized information, media etc.), constituting the personal biography. This personal biography has been enriched by their lived experiences of the city, as a whole or fragmented including the many spatial and temporal realms in which one's life takes place (neighborhoods, work places, and major affective moments). Likewise, the individual's role in the city has been related to his/her biographical situation, located in an urban context in each life phase. [8]

The description of the relationship of the citizen-city as a life experience is not new. It has been the object of study and reflection for those sociologists or philosophers who witnessed the growth of the industrial cities in the late nineteenth century, such as SIMMEL, SPENGLER or HEIDEGGER (CHOAY, 1965), for example. For the representatives of the Chicago School, the city experience led to an urban personality or a way of being and thinking, specifically of the inhabitants of the city. The street or neighborhoods were conceived of as laboratories where the lifestyles of different social groups that made up the increasingly diverse U.S cities could be observed (GRAFMEYER & JOSEPH, 1979). [9]

In defining the urban experience, LEDRUT (1973) dismisses the separation between city-object and inhabitant-subject, because he considers that the experience of living in a city includes both, the city and the inhabitants. The significances do not exist in the city by themselves, but depend on the people's practices in the urban space in certain times and cultures. [10]

Using HALBWACHS's (1925, 1950) notion of collective memory as theoretical framework allows to reconstruct the past experience of the city from a narrative in the present. HALBWACHS's theory of social memory shows how social structures shape subjective experience and memory. This dual perspective, individual and social, is what I wanted to address in this research by studying the stories of the senior residents who lived the transformations of the city in the last decades. Their life trajectories are personal and social at the same time; not only do they include socially shared memories, but the sociocultural possessions have also shaped each individual's representations, feelings and experiences, throughout his life. [11]

Telling the story of the place where people have lived is telling the story of their lives. In this paper I am interested in the overlap between the story of a person's life (from the past to the present) and their memories of the city. The question, then, is how to study the city's collective memory? I believe that the theory of social representations (MOSCOVICI, 1961) can help to answer this question if I consider that the collective memory of the city is a form of social representation in which the individual reconstructs his past. [12]

There are at least three ways in which the link between theories of collective memory and social representations is important. First, the collective memory works similarly to the social representation, in the sense that it is a symbolic construction anchored in different social groups and culture. Secondly, collective memory gives continuity to the social categories of performance at the moment of building a social representation of an object. Third, MOSCOVICI (1961) proposes that social representations are addressed from the definition of a subject and an object of representation: Who represents what? In the case of the study of the collective memory, I can establish the same starting point: Who remembers what? From here comes the central question of this work: What social representations and collective memories of Mexico City have elderly adults constructed from their life experiences? The city is an object of representation and memory; elderly adults are those who build representations and memories of it. [13]

3. Subject/Object of Representation: The Elderly and the City

The city as object of representation or as a central theme of the residents' memory is considered here as the product of societies and their modus operandi, not only as the material frame of existence. The objective of this research is the study of the representations, experiences and memory of Mexico City from a subjective point of view. Nevertheless, I cannot obviate the economic, political, demographical or cultural dynamics that have marked the development of this metropolis, particularly during the last five decades where have taken place the adult life of this residents over 60 years old. My intent is not to make a deep analysis of the urban space of the capital city in this period; my interest lies in highlighting the general characteristics of Mexico City, that are widely recognized in the literature about it, focusing on: 1. economic growth at the industry level, 2. political centralism and social co-opting by the Partido Revolucionario Institucional (PRI), 3. the process of modernization of the city, and d) Population growth and urban expansion. [14]

The memory of Mexico City in the twentieth-century has been studied from several different points of view and disciplines: modernist spaces (DE GARAY, 2002, 2004; BALLENT, 1998; ZAMORANO, 2007), village anchored in the metropolis (SAFA, 1998; PORTAL, 2006; LICONA, 2003), nineteenth-century working class residencies (BOILS, 2005), and, peripheral neighborhoods (LINDON, 1999; NIETO, 1998; NIVÓN, 1998). Most of these studies address the urban memory rooted in a particular territory and bounded in Mexico City. Some others, see GARCIA CANCLINI, CASTELLANOS and ROSAS (1996), for example, are about the memory and the imaginary of the metropolis as a whole. [15]

This article aims to study representations and memory of the city as a territorial entity, focusing on the specific experiences of residential places at the level of neighborhood division or working class residencies. By following the individual's life path in its various components (residential, education, and labor), I will observe such representation and memory. [16]

Among the many actors involved in building the memory of the city, I chose the "elderly" residents (adults over 60 years), because they have accumulated a long experience of city life. [17]

4. Method: Studying the Subjective Aspects of the City and the Life Trajectories

The methodology used is qualitative. I think that the study of memories of the city, linked to the individual's life trajectory, requires a methodological perspective that makes it possible to observe an urban experience, built up over the years, at the center of the various social and institutional groups in which the life of the resident took place. Older adults' narratives of the city definitely describe their urban experiences, social representations and collective memory. For this reason, the in-depth interview is the main tool of study. [18]

Below, I present details on the preparation of the interview, sample selection and the interview process. [19]

After a number of pilot interviews with older adults, where I tested the life-story technique and biographical narratives, I decided that the open interview, structured in accordance with the individual's life trajectory and urban spaces where it took place, would be the most appropriate methodological strategy to achieve the objectives of this study. The interviews were done on an individual basis as it gives importance to the individual's life trajectory for this research. [20]

The concept of life trajectory is retaken from CAVALLI and LALIVE D'EPINAY (2006), to whom studying the parcours de vie, involves analyzing the development of human life in its temporal extension and its sociohistorical contexts. The life trajectory of an individual can be found in a set of specific trajectories corresponding to different fields or areas in which the person develops. Such paths may be more or less related, they are presented in a relatively orderly sequence, reflecting positions, transitions or events experienced by the subject. [21]

I drafted an interview script which began with two projective techniques that are frequently used for the study of social representations of urban spaces: word association (word stimulus: "Mexico City"), and drawing maps. At a later stage, the interview progressed from the past up to the present experience of the city, allowing the respondents to express themselves openly on the following topics: 1. current family situation, 2. residential history from birth up to the time of the interview, trajectories of the family, education, work or any other aspect that has marked the person's life. Questions were always asked about the places where these trajectories took place, 3. social representations of the current area of residence and Mexico City, and 4. family genealogies including the places where their children and siblings live. [22]

The interview script sought to deal with the following aspects of collective memory and social representations of the city held by adults of over 60 years of age:

Social frames of memory (HALBWACHS, 1950):

Time: personal (life stages) and historical (city past);

Space: city, neighborhoods, particular places;

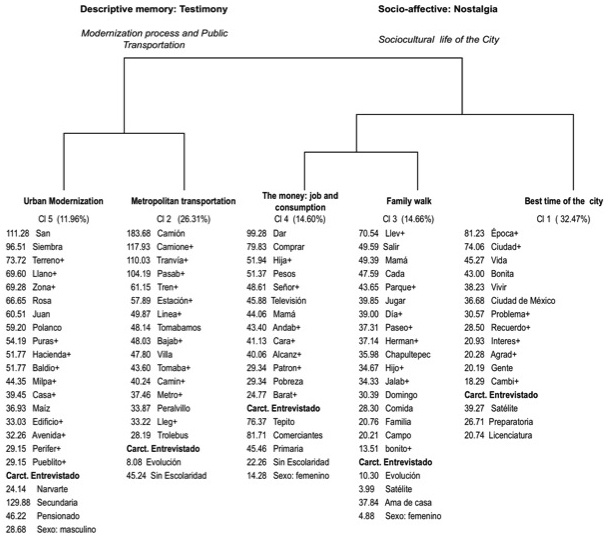

Groups: family and community context, education and job trajectory;

Sketch map of the spatial memory;

Social representations of the city (experiences, opinions, stereotypes, attitudes, knowledge, emotions, urban practices in current daily life). [23]

4.2 Respondents and their neighborhoods

The criteria used in the neighborhoods and informants chosen, matched the hypothesis of the existing differences of the social representations construction, memories of the city and urban experiences according to three social and geographical aspects: socioeconomic resources, the gender and geographic location (center-periphery). [24]

As the first point, a member of our research team, Dr. Salomon GONZALEZ2), conducted a sociospatial analysis consisted, at first, in locating AGEB3) of the metropolitan area of Mexico City according to INEGI4) which had a high proportion of elderly adults. These AGEB were categorized according to levels of marginalization (CONAPO5)), used as an indicator of social differentiation. The results of these tests were projected on a map of the metropolitan area, allowing to locate the AGEB suburbs and municipalities. [25]

The location criterion was governed primarily by the decade of incorporation of the suburb and municipality, where AGEB were located in the previous classification. To do this, I relied on the results of NEGRETE, GRAIZBORD and RUIZ (1993), they show the process of "physical expansion of the metropolitan area and gradual annexation of surrounding political-administrative units" (p.13). I selected two of the most discriminating AGEB marginalization levels (high and low) by district and municipality from the forties to the eighties. From the choice of two AGEB in five districts or municipalities (Central City, Coyoacán, municipalities of Naucalpan, Nezahualcoyotl and Ixtapaluca), I proceeded to observe the correspondence between AGEB and neighborhoods. I considered more appropriate to work per neighborhoods, because this concept, similar to the working class residencies refers to a social life within its territory, where they can be more easily identify. [26]

The field observations led us to select the following neighborhoods: Tepito, Narvarte (central city), Pueblo de los Reyes, Romero de Terreros (Coyoacán, incorporated into the metropolitan area in early 1950), Bosques de Moctezuma, Satellite City (Naucalpan, incorporated municipality in 1960), Evolución, Bosques de Aragon (Nezahualcoyotl municipality incorporated in 1970), La Cañada and Unidad Habitacional Los Héroes (Ixtapaluca municipality incorporated in 1980). [27]

I decided to do ten interviews per neighborhood, five men and five women, mainly due to the type of interview and their duration; minimum of 45 minutes and a maximum set by the informant's own speech and their availability (there were interviews of approximately four hours). [28]

The interviews were carried out by previous appointment in the homes of the respondents, or in cultural, health or social centers where they could be contacted in each neighborhood. The 100 interviews were recorded in a digital format and transcribed for processing. The interviewers were two men and seven women, most being Social Psychology graduates from the Metropolitan Autonomous University, campus Iztapalapa. Field work was carried out between 2008 and 2009. [29]

Here, I present the preliminary results of the analysis of 40 interviews conducted with 20 residents over 60 years old, living in to central neighborhoods, one popular (Tepito) and other middle class (Narvarte), and 20 living in two periphery districts, popular (Evolución) and middle class (Ciudad Satélite) also. Half men and half women. [30]

5. Combining Atlas.ti and Alceste Software: A Complementary Text Analysis

The complexity of the biographical interviews conducted presents special challenges for analysis. The first of these is the treatment of temporality in different life trajectories (family, residential, educational and work) that develop simultaneously during life's various stages. It shows the difficulty of separating the analysis of one history from the others. The second challenge is to analyze the memory of the city (as a whole, or broken down into fragments in specific urban spaces) that gradually appears in the narratives of the different life trajectories, for example, how the childhood memory of the city is constructed during the development of the different activities characteristic of that age (neighborhood life, games, family life, school, etc.). The third challenge is presented by the drawings of mental maps. This is a technique that worked with some respondents, but not with all, because they either did not understand the technique or refused to carry out it. In the majority of cases, the drawings generated interesting narratives about the city, which is why I decided to include them in the analysis as memories or current social representations of the metropolis. [31]

5.1 Atlas.ti: A tool for thematic analysis

The complexity of the material obtained has led me to use a variety of analysis techniques. At first, I read through the interviews to get a general impression of the main topics and detect a general structure of the narratives that were common to the group of respondents. From this first reading a list of codes and sub-codes aimed at giving an answer to the research objective arose: to analyze collective memory and social representations of Mexico City. The next step was to apply this broad code to the set of 100 interviews, using Atlas.ti software 6.2:

Collective memory of urban space

Mexico City past experiences and descriptions

Neighborhood narratives

Residential trajectories

Trajectories

Job

Education

Family

Life stages

Child

Young

Adult

Senior citizen

Mexico City today

Social representations of the city

Daily life

Health

Family network [32]

I decided to use the Atlas.ti program because it makes it possible to deal with a large number of interviews that generate wide-ranging narratives, as well as the possibility of analyzing the codes either separately or together. For example, the code "city memory" can be analyzed by itself, independently of the stage of the person's life, or alternatively, it can be separated for each stage, "childhood " or "old age." These were the main functions of Atlas.ti used for this article. [33]

In addition to the broad topical coding, I also established variables or case data codes that allowed me to track specific characteristics that would need to be compared in the study. These included sex, place of residence, life stage and social status. [34]

This analysis allowed to observe the speeches about the city for each stage of life, for each person as a member of a neighborhood or gender. I found, for example, there were differences by gender and social status in the city's past experiences related to the neighborhood of residence. The upper middle class women, for example, had greater access to education and most of them were devoted to the home after marriage. Women of the working class neighborhoods combined always precarious works and the care of the house and children. The men recalled the city from their job trajectory, in terms of educational attainment. [35]

Using Atlas.ti helped to complete a semantic analysis based on the researcher's interpretation of text contents by a codification process. This allowed to keep a "deep open knowledge" of the material, responding to this kind of questions: What are the topics that set up the urban memory of the "old" residents? How these topics correlate among themselves? How do women who have lived in the metropolitan area during its recent decades of growth and expansion narrate their life experiences? [36]

The search for meanings that Atlas.ti makes possible via the codification of the interviews establishes a kind of dialogue between the investigator and the interviewee that goes beyond the moment of the interview. The researcher adopts the task of analyzing the explicit language and that which is unsaid but is read between the lines. The work of interpretation, guided by the research questions, means that the researcher will participate deeply in the process of analysis. According to the literature on qualitative research methods, this is a valid and enriching procedure for understanding the social phenomena under study. [37]

However, the existence of another type of method, focused on analyzing the vocabulary used by respondents without the intervention of any codification of the text, presented the possibility of enriching the results already obtained. [38]

In this study, I carried out a complementary analysis of the interviews using the Alceste program, whose functioning I will explain below. [39]

5.2 Alceste: Analysis of the co-occurrences of the statements in a text

The French software Alceste (Analyse lexicale d'ennoncés simples d'un texte) helped to realize a statistical analysis using word co-occurrence frequency. While this program classifies the text by word co-occurrence, independently of the researcher's category system, I thought this method could be useful to discover words' associations, suggesting new themes that cannot be observed on a semantic discourse analysis, such as that which I carried out previously using the Atlas.ti program. [40]

This exploratory lexical analysis respond to the following questions: What is the type of vocabulary each group has? Which memory of the city matches with each group vocabulary? The differences by gender, socioeconomic status or geographic area, are linked to the groups detected by the software? [41]

The complementarity of the Atlas.ti and Alceste programs helped in the analysis of the study's results in two senses. In the first place, Atlas.ti was useful for carrying out the codification of long narratives into large themes. It made it possible to preserve the broad descriptions that the respondents gave of the city and their subjective experiences. Instead of subjecting these large interview fragments to new codification in Atlas.ti, I decided to use them as a text to carry out an analysis of co-occurrences, using the Alceste program. [42]

To carry out the Alceste analysis I selected the text corresponding to Atlas.ti code "Mexico City past experiences and descriptions," in order to observe memories of the city from childhood up to just before 60 years of age. [43]

Alceste carried out successive splits of the text (corresponding to Mexico City past experiences and descriptions coming from previous Atlas.ti analysis), distinguishing principal words (nouns, verbs, adjectives ...) from secondary words (articles, prepositions ...). Then the software took only the root of the principal words, excluding the declensions. After that, the program created UCE, elementary context units, which are composed by series of about ten principal words, recognizing sentences ending with a dot, comma dot. For instance, the next sentence is a UCE composed by five principal words: "The best time of the city was my youth." [44]

From the words co-occurrences in the UCE, the program classified vocabulary through a descendent hierarchical analysis, based on BENZÉCRI's statistical theory. Alceste's main principle is that each class shares the same discursive "universe" or semantic context (REINERT, 1993). [45]

Alceste made it possible for me to observe the way in which the vocabulary elements used by the respondents are related among themselves, forming a structure based on the most frequent co-occurrences. The software produced a number of results that were important for this study. [46]

The top-to-bottom hierarchical analysis (see Figure 1) made it possible to observe the relationship between the classes based on co-occurrences. This result provides evidence of the degree of proximity or distance among the groups of words that spoken by respondents.

Figure 1: Hierarchical descendent analysis [47]

Figure 1 summarizes the hierarchical structure given by the descendent analysis, adding the list of words ordered by their degree of association of each class (chi-square value). I also added the resulting labels from the interpretation of the contents of the classes, made from the lists and the most representative UCEs, where there are fragments of the discourse in which the words of the class are inserted. Figure 1 also includes the percentage of UCE that includes every class, allowing to observe the amount of text that occupied each universe of discourse. At the end of each listing are the socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents, with their degrees of association to the class. [48]

Alceste categorized into five classes all UCE (elementary context units) contained in the 40 interviews on the memory of the city of senior adults, corresponding to the Atlas.ti code "Mexico City past experiences and descriptions." Within each class, I was able to observe the terms that were most representative of these via the frequency of their appearance in the classes related to their frequency in the text as a whole, as well as via the calculation of Chi-square, used as a measurement of association from the word to the class. The meaning of the terms is observed in the Alceste complementary analyses, particularly in the one that provides the listing of the most representative UCE (elementary context units) of each class, where the inserted words appear in the interview fragments that they were taken from by the program. [49]

The content analysis of the classes (word lists and UCEs) allowed to interpret the contrast between the first ramification of the tree, and the gap of the next level of ramification, seen, for example, the close relation of Classes 3 and 4, while Class 1 is a subset of words in itself. [50]

The hierarchical descendant analysis related vocabulary of Class 2, corresponding to the metropolitan transportation, to vocabulary of Class 5 which refers to urban modernization terms (see list of words below Class 2 and Class 5 in Figure 1). The analysis of the list of words and the fragments of interviews (UCE) corresponding to these two classes allowed to observe that they are testimonies about urban transportation and modernization process of the city. This kind of discourse is opposed to the "universe of discourse" (REINERT, 1993) formed by the vocabulary of Classes 1, 3 and 4 (see lists of words below Class. 1, Class 3 and Class 4), which recalls the sociocultural life of the city using affective terms to talk about family walks, earning money and consumption on the last decades, best time of the city. [51]

Below, I will present the interpretation of the Alceste results, starting from the general structure of the discourse that resulted from the descending hierarchical analysis (reading the graph from top to bottom). Subsequently, I will analyze the content of the classes, based on the vocabulary contained in these and in the interview fragments that correspond with the most representative UCE (elementary context units) of each class. More information about how these two tools work together will be presented in the final discussion. [52]

5.3 Urban modernization versus sociocultural life of the city

As I have already said, our first observation is that Alceste separated the vocabulary that corresponds to the urban modernization and the creation of new forms of daily mobility (Classes 5 and 2), from another different vocabulary, the subset of Classes 1, 3 and 4, refers to the sociocultural life of the city. [53]

This exploratory analysis shows that the experience of the transformations of urban structure, of their resources regarding on housing, transport and services correspond to a descriptive memory, where the resident rebuilds his memory of the city as a witness of the environment changes, as someone who witnessed the transformation of a rural landscape in urban and the technological transformation of the routes: from tram to bus, bus to subway. [54]

In contrast to this descriptive or testimonial memory, appears a vocabulary that speaks of the sociocultural life of the city's past with nostalgia. In the discourse emerges a socio-affective memory that locates the best of the city in the past, mainly in the stages of childhood and youth. It is a memory focusing on tours of the city with the family, in the forms of entertainment and consumption of past decades. [55]

Are these memories so far apart as indicated by this analysis? Both are part of general discourse about the past of the city. My interpretation is that elderly respondents used a different vocabulary to talk about one aspect and another of the metropolis who lived in the past. I will describe in detail the contents of the descriptive urban memory, in contrast to the socio-affective memory of nostalgia; trying to observe what separates and connects them. [56]

5.4 Urban modernization and daily mobility

Between the oldest (born in 1918) and the youngest (born in 1950), elderly residents experienced Mexico City's strong process of expansion and modernization during the 20th Century. Between 1920 and 1940, the city grew from 906,063 to 1,757,530 habitants. From 1940 the population increment was accelerated and vertiginous, reaching the 5,392,809 habitants in 1960, to 14,454,925 in 1980 (PENICHE, 2004). The 2000 census reported 18,396,677 million of habitants, increasing to 20,137,152 in 2010. The greater growth in the city took place between 1940 and 1980, not only in population but also in territorial extension. The new housing sectors were given, either legally (residential developments) and illegal (invasion of communal lands) in increasingly distant to the center. [57]

In this context, a question arises: What memory has been recreated by the senior adults who witnessed this urban transformation? The testimonies of urban modernization contained in Class 5 refers to the process of construction and city growth in past decades, the memory of the people who were involved in the urban area, the gradual disappearance of a rural landscape, haciendas, farms , stables and ranches, which kept farming activities (see vocabulary of Class 5 in Figure 1). [58]

In this memory appear the names of some streets as urban development axes: San Juan de Letrán, which underwent several name changes and stretches from "calle de niño perdido" to the technical "Eje Central Lázaro Cárdenas" which lead to the current fast route of five lanes. Insurgentes Avenue pushed the urban expansion and prestige to the south (modern buildings, facilities and neighborhoods of middle-high status) and north of the metropolitan area. Insurgentes is popularly known as the longest avenue in the world. Periférico is referred as the symbol of the fastest circulation roads that were dominating the urban landscape of Mexico City. [59]

The software also shows relevance of the memory of residential neighborhoods which were the symbol of modernity at that time; some have become areas of prestigious business offices and, less residential land use. Polanco is associated to the city's Jewish population. La Zona Rosa as a center of entertainment, bars, restaurants, boutiques, from the seventies. Lomas de Chapultepec is mentioned as the first suburb of the city for entrepreneurs and politicians from the forties. Satellite City was a project controlled of planning urban development by Mario PANI, one of the most renowned architects. The new city became a simple middle class residential subdivision, city style bedroom, for obscure reasons of corruption (DE GARAY, 2000). [60]

The socio-demographic characteristics of respondents who are most associated with Class 5 (see Figure 1) indicate that the testimonial memory development and modernization of the metropolis is typical of men, who had an intense daily mobility for work or study. [61]

Class 2 contains speech expressing the metropolitan travel experiences itself, linking them to the changing urban landscape described on Class 5. The experiences of travel within the city that inspired urban memory are described in four types of vocabulary: transport (buses, trams, trains, subway, subway lines, stations, walking), the destinations in the city (Virgen de Guadalupe's Church, Peralvillo, La Viga, Xochimilco, Zócalo, Tacubaya, Obregón, Universidad, Facultad, Observatorio, Anaya, Monumento, Iztapalapa, Lecumberri, centro, Chapultepec, Candelaria, neighborhoods, suburb, Merced), roads (avenues, streets, driveways, Circunvalación, Jesus Carranza, Calzada de los Misterios) and the city dweller mobility actions (went, came, back, took). [62]

It is important to notice that the avenues and places of destination or origin which marked the paths are within the limits of the Distrito Federal and surrounding municipalities in the Estado de Mexico, although metropolitan area occupied the territory of these municipalities since the late fifties. The absence of the territory of the Estado de Mexico in the memory of the city is not due a lack of experience in that territory; 20 of the respondents come from there. The kind of places remembered as a destination suggests that memory is focused on trips to emblematic places such as the walking places, locations of consumption, labor and education, all located in Mexico City. The travels to metropolitan areas linked to the everyday experience seem forgotten in the city's past. [63]

Modernization of transportation becomes relevant in the memory of the city, as shown by fragments of UCE in this class:

"There were some iron wagons, those were the wagons, they went to La Villa and there they had their station beside of La Villa, and made the tour again, from La Villa to Zócalo and from Zócalo to La Villa."

"When I arrived to the city there were cobbled streets, the sidewalks of cement but half street was cobbled, here in front the bus passed that was the Circuito Hospitales, there were the Roma-Mérida, the terminal was here in the corner ..."

"After that came the trolley, it was all electric because the train was electric but like slower and after they put in those which are like buses, trolley, then they take off the trams, the buses of that line of Peralvillo-Cozumel."

"One of the first subway stations was Pino Suárez." [64]

It is emphasized that the most associated variable to class 2 belongs to respondents who did not have any instructions. It means that elderly adults who mentioned public transportation were those who tended not to have formal education and were often in less stable and lower paying jobs. This prevents them from owning a car and forced to use public transportation. The thematic analysis by Atlas.ti also showed the educational trajectories of respondents are related to career paths and upward social mobility. By this means, those who had higher education or graduate school, had access to well-paying stable jobs that allowed them to acquire a car and gradually move away from public transport. Private car became a sign of status in the context of the city's modernization process. [65]

5.5 Nostalgia for the sociocultural life of the city: Youth, consumption and family

The step of 5 to 18 million people in 40 years (1960-2000), the increase of vehicles and the opening of fast roads, the changing rhythms of everyday life, joined with the aging process of the interviewees, seem to have created a rift between the past and present in their urban experience. The memory of the old city dwellers became nostalgia. [66]

Nostalgia, according to HALBWACHS (1925), beautifies the past to escape from the present situation of who builds the memory. Analyses using Atlas.ti about the experiences of the city of seniors in this area suggest that the current metropolitan area of Mexico City is an aggressive environment for them. Our respondents opposed an actual city less favorable with the past city that was more beautiful and enjoyable in their minds. However, Alceste's results indicate that nostalgia (see Classes 1, 3, 4 in Figure 2) is not equal for all respondents, but differs according to the neighborhood, sex and education levels. [67]

The women's city memories are associated with the topics of money (how to earn and spend, poverty, Class 4) and family outings in the city (Class 3). In turn, there is another differentiation in terms of these female memories: while the memories of family outings are not related to the residents of any neighborhood in particular, the memory over economic resources is more important for older residents of Tepito. [68]

It does not seem strange that the residents of a working class neighborhood with a commercial vocation rooted in decades rebuilt the memory of the city from the purchasing power of the cost of living the different ways to earn money. The ten respondents in Tepito carried on trade activity throughout their lives within the streets. These respondents, like others who also contribute memories in this category, described a social landscape of migration and poverty, not just in their division, but the city in general. They remembered the arrival in the city of poor peasants in search of better opportunities. Many were employed as laborers, or developing various trades on their own. In fact, informants recalled the transition of economic activity in Tepito, which increased from a mix of trade and crafts to concentrate on an intense commercial activity that invaded the streets with imported, in recent decades, products from China. [69]

Respondents generally perceived a loss of purchasing power, less opportunities for young people to find employment, and a deterioration of living conditions. They attributed the causes of this situation to political corruption and mismanagement of the economy. Corruption is not only mentioned with respect to government employees and politicians, but in daily practice for every citizen. Senior respondents had the impression that Mexican people at that time were more honest, the city was "more beautiful," there was less crime; and even the thieves and drug users had more respect, they were more discreet, robbed the rich only and without violence. [70]

References to the electrical appliances to which the respondents had access throughout their life were also important in this Alceste class of terms. For example, mention that the radio and television were not available to most people, much less the poorest. Over the years these devices "were getting cheap and everyone had a radio," and later television. There are stories of those who were able to buy TV in the fifties or early sixties, allowing the neighbors to see the news. Some of them paid to watch popular shows or football games. [71]

Family outings in the city, at different life phases, from childhood until the time that respondents had young children, are other aspects of city life that respondents remembered with nostalgia. It is primarily about recreational activities on weekends during holidays, when respondents went to parks (Alameda and Chapultepec are the most common) to have picnics or outdoor play. Also mentioned were the cinemas, theaters and evening activities such as ballroom dance or visits to the traditional Garibaldi Square. Socioeconomic characteristics most associated with this class (3) belong to housewives, mostly uneducated. [72]

Finally, the memories of the most beautiful time of the city evoked in Class 1, belong to the youth of the elderly respondents: "the best years of the city are the best years of my life." "The time that I remember as the most wonderful was when as a teenager, I suffered everything that I could ever possibly from 12 to 16, I always have been in the streets." "Because there I had the love of my life, I wish return to live that time again, when I was 18 years old, I would like that really, and change some things." [73]

Respondents from upper middle class of the division of Satellite City are the ones who remember their youth combined with certain forms of entertainment: dancing, soccer, bullfighting, inns and block parties made in the street with the participation of neighbors. They miss a city where greater unity and cordiality were celebrated among people circulating in the street. In the view of interviewees, people dressed more elegantly at an earlier time before denim and long hair for men became fashionable. [74]

The purpose of this paper has been to consider a combination of methods for the study of urban memory observed through biographical interviews. Bringing together these methods expands the knowledge about the qualitative data analysis. [75]

The Atlas.ti software allowed to order the long free narratives about the city in categories and codes, and later focusing the analysis according to the time (development stages, life phases of the senior people), space, (city, neighborhood, areas or specific places) and the biographical trajectories (work, family, education, housing). [76]

To carry out a deeper and detailed analysis of the major topics that comprise the memory and the representations of the city, I decided to conduct a quantitative analysis of co-occurrences using the Alceste software. To do this I only took fragments of discourse corresponding to the memory code of the city from Atlas.ti previous analysis. As I have pointed out, this second method allowed me to distinguish socio-affective memory from a descriptive memory. The first, more feminine, is linked to nostalgia for the sociocultural life of the city lived in past decades, particularly at the stage of youth. The second, more masculine, refers to the witnessing of the modernization process. There was evidence also of differences of urban memory by urban residential zone, socioeconomic status and educational attainment. [77]

The Atlas.ti program helped to carry out a thematic analysis of the discourses about the city's past and present, which were interpreted as expressions of representations and memories of the city, constructed by adults of over 60 years of age. It made it possible to capture the complex experience of life in different times and spaces, expressed in narratives constructed at the time of the interview, based on memories, knowledge (both specialized and common sense), beliefs and emotions. Use of this analysis was aimed at respecting the respondents' mode of free expression, via a reading of the direct meaning of what they said, as well as what their words implied. Atlas.ti is thus a technique similar to various theoretical approaches that analyze discourse in the search for social meanings, such as grounded theory, discourse analysis, social representations or the imaginary. [78]

In this logic of the qualitative analysis of the narratives, it would seem contradictory to approach the analysis of memories of the city through quantitative techniques. However, I consider that lexicometric analysis tools, such as Alceste, throw up a new vision of the discourse, allowing the researcher to explore them from another perspective. These techniques make it possible to think about different questions on the analysis and interpretation of the discourse: why is the frequency of one group of words high or low in the discourses of one or several respondents? What does it mean when a group of terms are co-occurring in certain interviews, groups of them or in the whole corpus? [79]

In my experience, combining the two techniques has complemented the analysis of interviews or texts (newspaper articles), carried out with the purpose of observing social meaning, social representations, collective memory and imaginary. In my opinion, when using the two techniques, the thematic or categorical analysis, which can be carried out via Atlas.ti, should always precede the analysis of co-occurrences via Alceste. The reason is that in the first type of analysis, the researcher acquires a deep and detailed knowledge of his data, which will make it possible to interpret the results from Alceste without bias, based essentially on listings of groups of words (classes), such as those I presented earlier. [80]

Despite their advantages, both methods are limited in the urban memory study. This has to do with the difficulty in understanding the complexity and dynamism of the city. For instance, space has suffered a major transformation to be capable to analyze it. Its geographical nature was transformed on oral descriptions. These limitations can be overcome by new Atlas.ti and MAXQDA version incorporating the spatial dimension in the analysis through georeferencing via Google Earth. [81]

However, the temporal dimension of the discourses and the processes that they describe, like the memory of the city, is still pending in the methodologies used in this work, such time is static. How can we give to the discourses of the stages of life continuity in time? [82]

Alceste software has additional limitations: loss of a percentage of the analyzed text when a great amount of text is required and it can analyze words only, images and geographical data are excluded. [83]

Finally, it should be stressed that the two programs used for this study offer many more tools of analysis than those presented here. They were not mentioned in this article as, so far, not all were necessary for the treatment of the interviews. [84]

1) This article is part of a larger project "Experiences, Representations and Memory of the City: The Case of Elderly People Living in Mexico City Metropolitan Area," with financial founds of CONACYT, Mexico. I should like to thank the reviewers of this article for their valuable comments on improving the original version. <back>

2) Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana-Cuajimalpa, Mexico City. <back>

3) Areas geoestadísticas básicas [Basic geostatistic areas] in Spanish. <back>

4) National Institute of Statistics and Geography: http://www.inegi.org.mx/. <back>

5) The marginalization levels were created by the Consejo Nacional de Población [National Population Council] in order to design public policies and social programs: http://www.conapo.org.mx/. <back>

Ballent, Anahí (1998). El arte de saber vivir. Modernización del habitar doméstico y cambio urbano, 1940-1970. In Néstor García Canclini (Ed.), Cultura y comunicación en la ciudad de México (pp. 65-131). Mexico City: UAMI-Grijalbo.

Boils, Guillermo (2005). Pasado y presente de la colonia Santa María la Ribera. Mexico City: UAMX.

Cavalli, Stephano & Lalive D'Epinay, Christian (2006). Parcours de vie et changement: un état de la question. In Stefano Cavalli, Gaelle Aeby, Mélanie Battistini, Corinne Borloz, Geraldine Bugnon, Ivan de Carlo & Emilie Rosenstein (Eds.), Ages de la vie et changements perçus (pp.21-29. Genève: Université de Genève.

Choay, Françoise (1965). L'urbanisme, utopies et réalités. Paris: Editions du Seuil.

De Garay, Graciela (2000). Mario Pani. Investigaciones y entrevistas. Mexico City: Instituto Mora, CONACULTA.

De Garay, Graciela (2002). Rumores y retratos de un lugar de la modernidad. Mexico City: Instituto Mora, UNAM.

De Garay, Graciela (2004). Modernidad habitada: Multifamiliar Miguel Alemán, ciudad de México 1949-1999. Mexico City: Instituto Mora.

García Canclini; Néstor; Castellanos, Alejandro & Rosas, Ana (1996). La ciudad de los viajeros, Travesías e imaginarios urbano: México 1940-2000. Mexico City: UAM-Grijalbo.

Grafmeyer, Yves & Joseph, Issac (1979). L'Ecole de Chicago. Naissance de l'écologie urbaine. Paris: Aubier.

Halbwachs, Maurice (1925). Les cadres sociaux de la mémoire. Paris: Albin Michel.

Halbwachs, Maurice (1950), La mémoire collective. Paris: P.U.F.

Ledrut, Raymond (1973). Les images de la ville. Paris: Anthropos.

Licona, Ernesto (2003). Producción de imaginarios urbanos. Dibujos de un barrio. Puebla: BUAP.

Lindón, Alicia (1999). De la trama de la cotidianidad a los modos de vida urbanos. El Valle de Chalco. Mexico DF: Colmex/Colegio Mexiquense.

Milgram, Stanley & Jodelet, Denise (1976). Psychological maps of Paris. In Harold Proshansky, William Ittelson & Leanne Rivlin (Eds.), Environmental psychology: People and their physical settings (pp.104-124). New York: Holt Rinehart and Winston.

Moscovici, Serge (1961). La psychanalyse, son image et son public. Paris: PUF.

Negrete, María; Graizbord, Boris & Ruiz, Crescencio (1993). Población, espacio y medio ambiente en la Zona Metropolitana de la ciudad de México. Mexico City: Colmex.

Nieto, Raul (1998). Experiencias y prácticas sociales en la periferia de la ciudad. In Néstor García Canclini (Ed.), Cultura y comunicación en la ciudad de México (pp.234-277). Mexico City: UAMI-Grijalbo.

Nivón, Eduardo (1998). De periferias y suburbios. In Néstor García Canclini (Ed.), Cultura y comunicación en la ciudad de México (pp.204-233). Mexico City: UAMI-Grijalbo.

Peniche, Luis (2004). El centro histórico de la ciudad de México. Una visión del siglo XX (Serie Ensayo, 79). Mexico City: UAM.

Portal, María (2006). Espacio, tiempo y memoria. Identidad barrial en la ciudad de México: el caso del barrio de la Fama, Tlalpan. In Patricia Ramírez & Miguel Angel Aguilar (Eds.), Pensar y habitar la ciudad (pp.69-85). Barcelona: Anthropos-UAMI.

Reinert, Max (1993). Les mondes lexicaux et leur logique à travers l'analyse statistique d'un corpus d'un récit de cauchemars. Langage et société, 66, 5-39.

Safa, Patricia (1998). Vecinos y vecindarios en la ciudad de México. Mexico City: CIESAS-Porrúa.

Schütz, Alfred (1962). El problema de la realidad social. Escritos I. Buenos Aires: Amorrortu.

Zamorano, Claudia (2007). Los hijos de la modernidad: movilidad social, vivienda y producción del espacio en la ciudad de México. Alteridades, 34, 75-91.

Martha DE ALBA is professor of social psychology in the Department of Sociology at the Autonomous Metropolitan University, Iztapalapa Campus, Mexico City. She gained her Ph.D in social psychology from the Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales in Paris, France.

Contact:

Martha de Alba

Department of Sociology

Social Psychology Area

Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana-Iztapalapa

Av. San Rafael Atlixco 186, Colonia Vicentina

09340, Mexico City.

Mexico

Phone: +52 +55 580 44 790

E-mail: mdealba.uami@gmail.com

De Alba, Martha (2012). A Methodological Approach to the Study of Urban Memory: Narratives about Mexico City [84 paragraphs].

Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 13(2), Art. 27,

http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs1202276.