Volume 15, No. 1, Art. 13 – January 2014

The Social Meaning of Inherited Financial Assets. Moral Ambivalences of Intergenerational Transfers

Merlin Schaeffer

Abstract: What do inherited financial assets signify to heirs and testators and how does this shape their conduct? Based on grounded theory methodology and twenty open, thematically structured interviews with US heirs, future heirs and testators, this article explicates a theoretical account that proposes a moral ambivalence as the core category to understand the social meaning of inherited financial assets. In particular, the analysis reveals that the social meaning of inherited assets is a contingent, individual compromise between seeing inherited assets as unachieved wealth and seeing them as family means of support. Being the lifetime achievement of another person, inheritances are, on the one hand, morally dubious and thus difficult to appropriate. Yet in terms of family solidarity, inheritances are "family money," which is used when need arises. Taken from this angle, inheriting is not the transfer of one individual's privately held property to another person, but rather the succession of the social status as support-giver along with the resources that belong to this status to the family's next generation. Heirs need to find a personal compromise between these poles, which always leaves room for interpretation.

Key words: inheritances; meritocracy; wealth; generations; family solidarity; grounded theory methodology; interviews; USA

Table of Contents

1. Introduction: Inherited Assets in Meritocratic Societies

2. Methods and Strategy of Analysis

2.1 Sample and sampling strategy

2.2 Interview type

2.3 Coding and strategy of analysis

3. Results

3.1 Inherited assets: What characterizes a financial transfer as an inheritance?

3.2 Heirs and testators: Who bequeaths and who inherits?

3.3 Boundary conflicts: Who belongs to the family?

3.4 Moral conflicts and anxiety: Problems to appropriate inherited assets

3.5 "Safety net" and capital: Purposes of inherited assets

3.6 Unachieved wealth versus family money: Justifications of inherited assets

3.7 Keeping it invested: Usages of inherited assets

4. Discussion and Conclusion: The Moral Ambivalence of Inherited Financial Assets

1. Introduction: Inherited Assets in Meritocratic Societies

Despite our societies' meritocratic image, the economic impact of inheritances is tremendous. Leading banks are preparing for an "inheritance-wave," because 61 per cent of the world's millionaires are above 56 years of age. According to the "World Wealth Report" (MERRILL LYNCH & CAPGEMINI, 2006), these "high net worth individuals" are worth $33.3 trillion and 92 percent of them plan to bequeath their share of this wealth to their respective family members; this prospective wealth transfer is hitherto unknown in world history. Inheritances are also a socially significant phenomenon in the middle classes (e.g. KOHLI et al., 2005), and encompass succession of family companies (e.g. BREUER, 2009, Ch.9) or passing on of personal objects (e.g. LANGBEIN, 2002). This article focuses on financial assets. While a few existing studies show that such assets are stratified by the usual determinants such as gender, ethnicity and education (e.g. LEOPOLD & SCHNEIDER, 2010; SZYDLIK, 2004), their long-term impact on wealth distribution is a contentious topic in the social sciences (e.g. MORGAN & SCOTT, 2007; WOLFF, 2003). Complementing such research, this study is concerned with the underlying social meaning of these transfers, i.e., what do inherited financial assets signify to heirs and testators, and how does this shape their conduct? [1]

Previous research by economists on bequest motives implicitly suggests three potential social meanings of inherited assets (for a review see FESSLER, MOOSLECHNER & SCHÜRZ, 2008). While some claim that inheritances are simply random leftovers, because of individuals' inability to predict the timing of their deaths (e.g. HURD, 2003), others propose that inheritances are strategic exchanges of assets in return for care and love in old age (e.g. BERNHEIM, SHLEIFER & SUMMERS, 1985). Finally, a third position holds that testators are simply altruistic and care for the wellbeing of loved ones (e.g. BARRO, 1974). In sociology, love and reciprocity have likewise been suggested as motives (e.g. FINCH & MASON, 2000; GOODNOW & LAWRENCE, 2008; KOHLI et al., 2005; KOSMANN 1998). All three approaches make implicit assumptions about the social meaning of inheritances, i.e., if bequests were random financial leftovers, they would have a social meaning that parallels a lottery win—a random unexpected bonus. If they were motivated by an exchange for services or reciprocity, their social meaning would equate that of compensation. Finally, if they were motivated by altruism and love, they would have the social meaning of a gift. [2]

Next to the literature on testators and their bequest motives, there are also highly informative accounts of attitudes to inheritance and will making in the UK (HUMPHREY, MILLS, MORRELL, DOUGLAS & WOODWARD, 2010; ROWLINGSON, 2006), but these do not investigate the underlying social meanings of inheritances that give rise to those attitudes. More informative with respect to the social meaning of inherited assets is Janet FINCH and Jennifer MASON's (2000) study on inheritances as indicator of the state of contemporary family relations in the UK. They argue that because inheritances signify family membership and because there are no legal restrictions on the freedom to testate, bequeathing is a practice of defining who belongs to the family. And yet, they describe the reception of an inheritance as signifying a stroke of luck and a sign of affection, which parallels the above-mentioned implicit assumption of seeing inheritances either as an unexpected bonus or as a gift. Marianne KOSMANN (1998) analyses how women inherit in West Germany and how they fight for equal shares of bequests, since these signify family membership and status. According to her typology of heirs, the meaning of inheritances differs by type of heir and can be seen as safety, luck, responsibility, independence, freedom, gift, exchange for services, or as a legal right. But Marianne KOSMANN does not propose a coherent framework that would account for the different meanings and the conditions under which they arise. While all these accounts of inheritances provide useful descriptions of some inheritance cases and propose different social meanings of inheritances, none represents an explicit investigation of the latter. [3]

Against this background, my aim is to go beyond the implicitly held assumptions about the social meaning of inheritances by conducting an explorative investigation of twenty open, thematically structured interviews with white middle class US heirs, future heirs and testators, covering roughly thirty-eight inheritance cases. The analysis is guided by grounded theory principles in the tradition of Anselm STRAUSS (1987; see also STRAUSS & CORBIN, 1990). Inspired by the above-discussed literature on inheritances, I started my investigation under the guiding assumption that inheritances need to be understood in terms of reciprocity theory. Given the predominant idea that a gift creates debt, I originally assumed inherited assets either to pay off debt that had arisen from received care and love in old age, or that inherited assets create a debt that cannot be repaid because the giver is dead. Hence inheritances establish indirect reciprocity between generations, where parents feel a need to pass to their children what they had been given by earlier generations (HOLLSTEIN, 2005). Yet early on, while conducting and analyzing a first set of five interviews in the Fall of 2007, I realized that a web of reciprocal relations did not govern the feelings and opinions expressed, nor the actions reported by my interviewees. That will become apparent throughout this article. Most importantly, and in stark contrast to the above-mentioned positive connotation of inheritances as gift, compensation or stroke of luck, I also encountered deeply negative accounts of inherited assets as "blood money," "fraud" and "unachieved wealth." In an attempt to develop an alternative approach to the phenomenon, I eventually shifted my attention to two strands of literature which do not deal with everyday heirs and testators in particular, but which helped me break down the overall question of what inheritances signify and how this shapes people's conduct. Three sets of guiding questions emerged which turned out to be fruitful during the second phase of interviewing and explorative analysis in July 2008. Those questions are derived from Viviana ZELIZER's (1994) work on the social meaning of money and Jens BECKERT's (1999, 2008) account of how inheritances have become morally ambivalent with the rise of industrialization and meritocracy. [4]

In her general work on the social meaning of money, Viviana ZELIZER (1994) argues that money is not a universal exchange medium, but that social scientists should recognize the importance of the social meaning of money. Gifts, entitlements and compensations, for example, are not three interchangeable descriptions of a financial transfer between two persons, but are distinct types of transfers that correspond "to a significantly different set of social relations and systems of meaning" (ZELIZER, 1996, p.481). It would be seen as highly inappropriate if bosses left a tip on the desk after discussing a topic with one of their employees, and yet it is common in many businesses to pay a performance related bonus. Because social relations and ways to transfer money are socially linked, different types of transfers work as "tie-signs" (cf. GOFFMAN, 1971, p.188) which imply a certain relation between giver and receiver. Moreover, she claims that the framing of money as tip, bonus, compensation, earning and so on, along with the particular social relation between receiver and giver, such as parent/child, boss/employee or friends etc., determines how people use received money. She gives several examples such as Christmas money not being meant to pay off gambling debts (ZELIZER, 1994, p.111). Viviana ZELIZER does not cover inherited money so that no expectations, let alone hypotheses, with regard to the social meaning of inherited assets arise from her work. But in line with Anselm STRAUSS and Juliet CORBIN's (1990, p.52) suggested use of literature, her work stimulates a guiding question, i.e., what is the nature of relationships within which inheritances occur and what kind of relationship does an inheritance signify to the parties involved? [5]

From a historical perspective, the succession of property rights was central in agrarian societies, where property in land had to stay the property of a farming group if it wanted to sustain its existence over generations, i.e., "inheritance involves the transmission of rights in the means of production (though the allodial right may ultimately be vested in a landlord), a process critical to the reproduction of the social system itself" (GOODY, 1976, p.14). Under these societal circumstances, inherited property was seen as family property and this was its social meaning. Living generations saw themselves as stewards of the group's property and because the family was organized around its economic function, the land represented the family and was treated as "inalienable possession" (WEINER, 1992, p.33). Yet, with the transition from an agrarian to an industrialized economy, land lost its function as means of production for most parts of the population. Against this historical transition from an agrarian to an industrialized economy arises the second guiding question, i.e., where do testators and heirs see the purpose of inherited assets nowadays? [6]

Along with this transition to an industrialized economy went a change in the understanding of property now seen as individual private property (BECKERT, 1999, p.42). This is best explicated in LOCKE's philosophy: "The labor that was mine, removing them [objects] out of that common state they were in, hath fixed my Property in them" (LOCKE, 1988 [1689], p.289). John LOCKE ties property to the idea of meritocracy, meaning that a person establishes an entity as property by means of labor. These individualized values of meritocratic societies contradict the inheritance of social and economic statuses, which is why classic scholars such as Émile DURKHEIM and Max WEBER expected an abolishment of, or at least a strong constraint on, the possibility to bequeath. However, as Jens BECKERT (1999, p.60) points out, both Max WEBER and Émile DURKHEIM overlook the dilemma such a liberal position runs into. While bequests contradict the principle of meritocracy, the prohibition or heavy taxation of bequests runs against the freedom to testate and thereby against the principle of individual private property. This dilemma results in an interesting situation where two opposing moral values need to be negotiated and brought to a historically contingent and constantly contestable compromise. Focusing on the development of formalized, legal inheritance laws, Jens BECKERT (2008) analyses how different moral conceptualizations of inheritances are negotiated and brought to compromise in German, French and US parliamentary debates. Jens BECKERT's work does not tackle the question whether common everyday heirs and testators also recognize any moral dilemma of bequeathing and inheriting in meritocratic societies, and if so, how they deal with these moral dilemmas. This is the third and final guiding question for my explorative investigation. [7]

On the following pages, I will first describe the methodological set-up of this study by giving detailed information about sampling, interview technique and strategy of analysis. Then results are presented along seven categories that turned out to be central during the analysis. The final section integrates the findings by proposing to understand the social meaning of inheritances as being situated in a morally ambivalent way between unachieved wealth and family means of support. [8]

2. Methods and Strategy of Analysis

This is an exploratory, qualitative investigation since little is known about the social meaning of inherited financial assets. The investigation follows the principles of grounded theory methodology (GTM; GLASER & STRAUSS, 1967). The aim is to develop an empirically grounded theoretical account of what inherited assets signify, and how this governs heirs', future heirs' and testators' conduct. In particular, the analysis follows Anselm STRAUSS' (1987; see also STRAUSS & CORBIN, 1990) conception of GTM, which is more favorable with regard to the use of scientific literature. In this respect, it is important to note that the above literature does not provide a priori theories that I seek to test or merely illustrate. Instead, the literature first helped stimulate fruitful guiding questions (p.52), and now serves as a wider hermeneutic framework within which I situate my particular middle-range theory (MERTON, 1968, Ch.2). I believe this use of existing literature to be in line with GTM's three constituting elements, i.e., theoretical sampling, contrasting and theoretical sensitive analysis, and simultaneous data collection and analysis. The contribution of these three constituent elements results in a research process where theoretically important constructs, derived from the analysis of earlier collected data, are taken as criteria to collect further data. Usually the researcher is looking for either maximally or minimally contrasting cases that allow for comparisons. Overall, this enables the researcher to test inductively generated expectations and thus enables a methodological strategy that is both inductive and deductive. [9]

My initial deductive starting assumption of theorizing inherited assets in terms of reciprocity was not supported by a first wave of data collection and analysis. In contrast to the positive connotations of the meaning of inheritances in the existing literature, the category of a moral conflict and related negative connotations of inherited assets was already apparent. Through my parallel analysis of the gathered material and reading of literature on inheritances and meritocracy, I began to understand the importance of asking not only about (family) relations between heir and testator, but also about purpose and justification of inheritances. This insight resulted not only in an adoption of the interview guideline (listed below), but also in a theoretical interest to sample testators and future heirs in addition to heirs. Wherein do people who pass on their estate see the purpose of that money for heirs, and how do they justify these transfers? How about people who are both heirs and testators? The encouragement of such adaptation of data collection instruments and sampling scheme indicates an advantage of GTM in Anselm STRAUSS' tradition. [10]

2.1 Sample and sampling strategy

Research on inheritances faces the problem of approaching a phenomenon which involves three fundamentally private and delicate topics: family relations, personal wealth and, most delicately, death (cf. KOSMANN, 1998, p.170; LETTKE, 2003, p.163). Field access is, therefore, a difficult task. [11]

Initially, I accessed the field by conducting an ethnography of New York City's Surrogate Court (locations New York County and Kings County) in the Fall of 2007. Such an approach has merits in that conflicts, which are negotiated at such courts, are highly informative about actors' understandings of norms, values and expectations. Yet, the proceedings of a public court are not only highly technical, but also scatter a single case over many sessions at various dates, spanning several months. Most importantly, however, heirs are mostly absent from court proceedings, being instead represented by their attorneys. [12]

These reasons speak against an ethnography of inheritance court cases if the aim is to understand what inherited financial assets signify to heirs and testators. Since other "natural" settings where people explain, plan or negotiate inheritances are usually not publicly accessible, I decided against an ethnographic approach. Instead, I started to conduct open (semi) thematically structured interviews (see below) with heirs, future heirs and testators. To do so, high levels of trust cannot be developed during the interview, but need to be established beforehand so that people are willing to talk about this intimate topic in the first place. Herein lies an obstacle to sampling. In order to get into contact with a first set of interviewees, I relied on people whom I had met during my one-year academic visit to the US. A first set of five interviews with heirs I had personal contact with was conducted and analyzed in the Fall of 2007. Starting from personal contacts, I continued in late Spring 2008 by relying on snowball sampling to collect more data, i.e., I asked my interviewees if they perhaps knew other heirs or bequeathers who might be willing to give an interview. Usually, the common acquaintance established the contact to the prospective interviewee via e-mail, which generated the necessary level of trust. The snowball sampling procedure has further advantages with respect to studying inheritances, because it enables interviewing persons who participated in the same inheritance case. Methodologically, the comparison of such interview material is particularly desirable as a form of contrasting analysis of most similar cases. From a substantial perspective, such multi-perspective samples offer the possibility to study family dynamics in a better way (FINCH & WALLIS, 1993; KOSMANN, 1998, p.169). [13]

On the other hand, this sampling procedure has the known disadvantage of most likely creating a biased sample of similar people originating from the same social milieu—birds of a feather flock together (McPHERSON, SMITH-LOVIN & COOK, 2001). In my case this consisted initially of young, Christian and Jewish, highly educated white middle class Americans from the East Coast. GTM's emphasis to sample theoretically can level this bias if applied appropriately, because it calls for sampling of cases that are contrasting in theoretically relevant ways. The memos I wrote after each interview to keep hold of first concepts and expectations helped to purposefully look for interviewees with certain characteristics. Moreover, because the interviews were conducted in two stages, the second phase of data collection could draw on the theoretical insights of the first phase. [14]

Most importantly, this led me to successfully seek interviewees of older age groups and people with varying roles of heir, testator or future heir. The sample includes cases without any financial bequests, to cases where $2000, and finally up to millions of Dollars were, or are going to be bequeathed. The professions of the interviewees reflect their high education, but also show a rather large variation. They are editors, artists, attorneys, real estate agents, publishers, marketing coordinators, managers, musicians and academics. With regard to other dimensions, I was less successful in meeting the demands of theoretical sampling. A single interview each with a person living on the West Coast and an interviewee of Puerto Rican origin do not suggest different patterns for these populations. As the homophily principle would suggest, my sampling strategy did not allow me to interview less-educated persons or those who live in rural areas of the US. People from rural parts of the US might have different views on inheritances since the bequest of land as the means of production might still be of importance (cf. BREUER, 2011, §24). More problematic is the high educational level of my interviewees. Less educated people might be less sensitive to moral dilemmas connected to inheriting, so that the topic of this article might solely be a middle class phenomenon. Methodologically, highly educated interviewees can be expected to easily understand implications of interview questions and formulate coherent answers which makes it more difficult to find out whether an answer was given for reasons of social desirability. In light of this problem, I decided to first ask about the inheritance case and what the interviewees had done with the inherited money in a narrative part, before explicitly approaching the topics of justification and purpose of inherited financial assets, to impede the interviewees from making-up coherent post-hoc stories (see below). [15]

In order to decide about the number of interviews that would be necessary, I looked for theoretical saturation, meaning the researcher realizes that the interviews start to produce repetitive information (GLASER & STRAUSS, 1967, p.60); further interviews do not generate new information but only further cases. This point was reached after about the fifteenth interview. I kept on interviewing because of the variation that I hoped would go along with it. In total, twenty interviews were conducted with US heirs, future heirs and testators. These interviews cover about thirty-eight inheritance cases. Tables 1 and 2 summarize the sample. To guarantee anonymity, I refrain from listing all information or supplementary detailed case descriptions.

|

ID |

Interview location |

Sex |

Family status |

Inheritance role |

Age |

Age at inheritance |

Inherited from |

|

Int101 |

Café |

Male |

Married, one child |

Heir |

45 |

14 25 30 33 |

Father Mother Aunt Grandmother |

|

Int102 |

Home |

Female |

Single |

Heir |

29 |

30 |

Grandfather |

|

Int103 |

Office |

Male |

Single |

Heir |

27 |

23 |

Grandparents |

|

Int104 |

Home |

Female |

Cohabitating, two children |

Heir |

29 |

Future bequest |

Grandmother |

|

Int201 |

Office |

Female |

Single |

Heir |

28 |

(21), (25) & Future bequest |

Grandmother |

Table 1: The Fall 2007 Sample1)

|

ID |

Interview location |

Sex |

Family status |

Inheritance role |

Age |

Age at inheritance |

Inherited from |

|

Int105 |

Café |

Female |

Divorced |

Heir |

39 |

37 38 |

Father Grandmother |

|

Int106 |

Home |

Female |

Married, three children |

Heir, testator |

57 |

47 47 |

Aunt Mother |

|

Int107 |

Skype |

Male |

Married, two children |

Heir, testator |

47 |

21 21 27 39 |

Grandfather Mother Great aunt |

|

Int108 |

Office |

Male |

Married, two children |

Heir, testator |

53 |

46 |

Mother |

|

Int202 |

Skype |

Female |

Single |

Heir |

24 |

(21), (25) & Future bequest |

Grandmother |

|

Int301 |

Home |

Female |

Married, one child |

Heir, testator |

61 |

9 (35) 10 (35) 27 |

Grandfather Father Mother Aunt |

|

Int302 |

Home |

Male |

Married, one child |

Testator |

62 |

Future bequest |

Mother |

|

Int303 |

Home |

Female |

Single |

Heir, future heir |

25 |

Future bequest Future bequest |

Grandmother Parents |

|

Int401 |

Skype |

Male |

Married, two children |

Heir, future heir, testator |

42 |

14 (28) 35 Future bequest |

Grandmother Aunt Parents |

|

Int402 |

Skype |

Male |

Divorced, two children |

Heir, future heir, testator |

44 |

16 (30) 37 Future bequest |

Grandmother Aunt Parents |

|

Int403 |

Skype |

Male |

Married, one child |

Heir, future heir, testator |

46 |

18 (32) 39 Future bequest |

Grandmother Aunt Parents |

|

Int501 |

Home |

Male |

Married, one child |

Heir, testator |

81 |

70 |

Mother |

|

Int502 |

Home |

Female |

Married, one child |

Heir, testator |

65+2) |

49+ 54+ |

Father Mother in law |

|

Int601 |

Café |

Female |

Married, two children |

Heir, testator |

56 |

56 |

Mother |

|

Int602 |

Office |

Male |

Married, two children |

Heir, testator |

60 |

56 |

Father |

Table 2: The Spring 2008 Sample [16]

For this study twenty open, (semi) thematically structured interviews were conducted to collect objective data on inheritance cases (who received what, when and why), but also personal accounts of justifications, emotions or wherein the interviewees see the purpose of inherited assets. Moreover, because GTM relies heavily on contrasting analysis of different cases, I wanted to ensure to have approached certain topics with all interviewees. In keeping with these premises, I developed a guideline that principally divided the interview into a first narrative and a second thematic part. The guideline can be found in the Appendix. [17]

After clarifying the interview conditions (such as giving a guarantee of confidentiality, noting that the interview would be taped, and stating my interests as a researcher), I started an interview by asking the interviewees to give a general picture of themselves, including age, work, education and their family background. The aim of this question was to 1. get a picture of the interviewees' social background for later comparisons to other cases, and 2. making the respondent feel comfortable in the situation of being interviewed. This established the necessary level of trust for the actual topic. Some follow-up questions were asked in order to complete the general picture. Following this introductory part, I started the narrative module of the interview with the opening request to tell me about their personal inheritance experience in detail. While I interrupted as little as possible, follow-up questions ensured that the narration covered thematically important aspects, such as who else inherited, or what the interviewees did with their inherited assets. This guaranteed comparability over the cases. I did not ask about the inherited or testated assets' exact amount. I felt that this very delicate and private question could ruin the interview situation against little substantial benefit, because in one way or the other, people told me about the amount. At least some of the narration made clear whether the bequest involved small savings or large assets, as for example if an interviewer noted that he used parts of his inherited assets to buy a house. [18]

I purposefully started with this descriptive part in order to prevent later topics of justification and moral conflicts which would influence my interviewees' narrations. However, the narratives often introduced a major topic that seemed to dominate the interviewees' inheritance experience, such as a conflict with other heirs. In order to maintain the conversation/interview situation as "natural" as possible, these topics were then explored in detail instead of forcing the interview to follow the guideline's chronology. While doing so, I first continued with narrative follow-up questions on what exactly happened, to only then ask the interviewees to explain and justify their standards and actions. The aim was not to confuse purpose and justifications with narrations of past actions, even though any retrospective of course always entails implicit justifications of one's conduct. But I tried to at least separate implicit justifications of past actions and explicitly stated justifications of owning inherited assets. Subsequently, the topics that had so far not been approached from the guideline were addressed. It is important to note that the interview guideline did not serve as a schedule, but simply helped to cover all topics, while the narrative part served to discover new topics which inspired the subsequent interviews. The aim was to pursue interviews that would limit the potential for producing socially desirable stories in a coherent way, be comparable enough to allow for contrasting analyses, but at the same time open enough to explore new topics and each case's individuality within a comfortable interview situation. [19]

Interviews lasted between thirty minutes to an hour and a half. The length mostly depended on the complexity of the respective inheritance case. Some respondents were the sole children who had inherited from their parents. Others inherited several times, together with their siblings and cousins. Eight interviews took place in the interviewees' homes—in their kitchen or living room—without the presence of other people. Four were conducted in cafés at tables that limited the presence of others. Three interviews took place at the interviewees' work offices. Finally, I interviewed five persons via Skype (without using the video function) because they were living in cities other than New York. The latter interview situation, while seeming suboptimal in terms of interaction, also offered a favorable anonymity to the interviewees. [20]

2.3 Coding and strategy of analysis

GTM involves a complex strategy of analysis, which includes different coding procedures as well as memo writing and designing integrative diagrams. Again, it is important that all these strategies are rules of thumb and researchers need to develop their own style of working with the particular data at hand. My strategy of analysis included the following, recursively applied steps. [21]

After each interview, I wrote a memo on the case which entailed a short summary as well as first ideas about concepts, categories and potentially interesting in-vivo codes (concepts used by the interviewees themselves). In the following days, I started to transcribe relevant passages and summarized the rest of the interview in the same document, so as not to overlook important aspects later on (STRAUSS, 1987, p.266). Indeed, during later stages of the analysis, I oftentimes listened to such passages again and transcribed them when they turned out to be important. After the transcription, I also summarized the whole case on one to two pages, which helped the contrasting comparison later on. For each of the twenty cases, I thus had a first impression memo, transcripted passages and summaries of the interview, and a summary of the case. [22]

I used ATLAS.ti to code the data. GTM emphasizes three different and ideally subsequent types of theoretical coding: open, axial, and selective coding (STRAUSS 1987, p.55; STRAUSS & CORBIN, 1990, p.57). First, I openly coded concepts within each interview, without any constraints on introducing new concepts and without any systematic comparison across interviews. An example of a coded concept is the in-vivo code "blood money," which interviewee Int107 used to describe his feelings towards financial assets he had inherited from his parents as a teenager. Another example of a concept that emerged in this phase was that of responsibility. Note, however, that in addition to human memory, ATLAS.ti offers earlier used codes to ease later comparisons. This and the interviewer's memory compromise a pristine open coding of single interviews. While trying to "open up" the data in this way, I found the coding of dimensions of concepts in terms of duration, frequency and intensity less helpful, as these can best be judged by comparison to other cases. [23]

During the next step of analysis, I reduced the openly coded concepts to a core set of categories, which were compared across cases. The particular category that is compared at a time serves as the axis of the comparison, which is why this kind of contrasting analysis is called axial coding (e.g. STRAUSS, 1987, STRAUSS & CORBIN, 1990). For example, I grouped the two above mentioned concepts ("blood money" and responsibility) under the category of "moral conflicts and anxiety" during this phase of coding. The concept of responsibility also relates to the category of "'safety net' and capital" and thereby links it to "moral conflicts and anxiety." An important part of my work during this phase was to analyze cases that did not fit the theory which started to emerge. The analysis of such cases helped tremendously to explicate the conditions of a certain phenomenon such as facing a moral conflict; why did not all young heirs face a moral conflict? As we will see later on, what creates anxiety and moral conflicts among heirs is insufficient knowledge about the purpose and responsible use of inherited assets. Below, the findings are presented along the explicated categories. The quoted material is illustrative, but also being analyzed within the text, so that my work of pursuing the analysis and deriving at the social meaning of inherited property can be retraced exemplarily. [24]

The final aim of GTM is to find a core category, which integrates the developed theoretical account and clarifies the relations among the various categories (cf. STRAUSS, 1989; STRAUSS & CORBIN, 1990). The coding strategy to generate the core category is called selective coding, because few central categories are analyzed selectively. Since the coding strategies are rules of thumb, the researcher of course codes openly while already thinking about a potential core category for example. The core category of a moral ambivalence that demands for a personal compromise between seeing inherited assets as unachieved wealth or as family means of support is explicated in the discussion and conclusion section of this article. The above-mentioned category of a moral conflict directly relates to the core category, i.e., heirs who cannot find a personal compromise but see inheritances as unachieved wealth exclusively, face a moral conflict. [25]

3.1 Inherited assets: What characterizes a financial transfer as an inheritance?

According to US legal definition, an inheritance is a transfer post mortem, meaning it takes place after the giver's death. But this definition does not characterize the phenomenon that people see as inheritance in the US. The views explicated in the interviews rather support Frank LETTKE's (2003) definition of inheritances as a transfer of resources that is connected to the giver's death, which may well include a future death. For example, one of my interviewees who just finished law school does not define those assets that her still living grandparents put in a trust for her as an inheritance from her professional perspective. Yet, her personal view differs, because the reasons why people set up a trust, saving estate taxes and ensuring an appropriate long-term use of the assets, link the assets to the giver's death. For my interviewees, this qualifies transfers made via trusts as inheritances. Another example is the inheritance case of two brothers in their early forties. Their father supports them in many situations, such as down payments for their homes, renovations, or attorney costs. Usually, we would not consider such support transfers to be examples of inheritances. However, the father told his children about the total amount of his estate, explained to them that he will bequeath in equal shares, and declared that all support given now is credited against their future share of the bequest. For the two brothers the support transfers are inheritances, because they are declared as part of the estate they will inherit when their parents die. [26]

3.2 Heirs and testators: Who bequeaths and who inherits?

Quantitative studies of testaments show that testators usually pass on their property to their spouse, who again passes on the property to the children and grandchildren. The next most likely scenario is a bequest to in-laws, followed by bequests to second grade relatives such as aunts (e.g. FINCH, MASON, MASSON, WALLIS & HAYES, 1996). In surveys, people mostly respond that they inherited from their parents and plan to bequeath to their children (COX, 2003; HUMPHREY et al., 2010; SCHWARTZ, 1996). Why is inheriting from the spouse not reported in surveys, even though it is the most frequent case and obviously connected to death? According to my investigation, the reason lies in the fact that in contrast to seeing modern society as individualized, the household of a married couple is still the fundamental consumption unit. Just as resources are shared, the bequest is planned together and so testators commonly answered in the plural for themselves and their spouse, even though I asked about their individual plans. In their everyday logic, spouses just resume the command over the household's resources; they do not "inherit" the surviving spouse's estate. [27]

Another question that arises from such surveys is why people bequeath primarily to their children and not any other caregivers or loved ones as suggested by theories that see reciprocity or altruism as driving motivators to bequeath. In contrast to altruism or reciprocity as motives, my investigation suggests that there is a social norm that demands a bequest to one's children, given that there are assets that could be passed on:

"I mean I have friends whose mothers died and didn't leave them anything. I mean what a way? What a thing to do? What a slap in the face!" (Int106, heir and testator, age 57) [28]

Concerning US law there is no problem with the case described in this interview, because there is freedom to testate. But the question "What a way?" implies that disinheriting one's children breaks a norm, and is even conceived of as an insult. This suggests that children have a claim to their parents' property, even though we think of it as personally owned. This norm to pass on to one's children is rooted in the solidarity that characterizes the relation between parents and children as members of one family, which is best exemplified by the following quote from a testator. I asked this interviewee whether she plans to bequeath to her nieces and nephews, as an aunt who also has own children:

INT301: "No, no not at all. Nor would [sisters] bequeath to me. I don't feel responsible for [sister's] children. [...] I don't know how I'd feel if one of them was about to die or die straight. I'd be more likely to say: 'Mom why don't you give more money to them', rather than me doing it directly. And honestly, I just wouldn't want [daughter] to take money from [sisters]. It would make me very uncomfortable. It would screw up, you know, it would create an uncomfortable sense of indebtedness I think."

Interviewer: "Indebtedness in which sense?"

INT301: "Just, yeah, we're, you know, we're independent. We're responsible for our children but not for our, my sister's children. Yeah that would—it'd be weird."

Interviewer: "To whom would they be in debt?"

INT301: "I think it would be more that the relationships between me and my sisters would get weird." (Int301, heir and testator, age 61) [29]

This interviewee does not want to bequeath to her nieces and nephews, because she does not feel "responsible" for them. In turn, this implies that people bequeath to their children because they do feel responsible for them. If there were a case of need in one of her sisters' families, the interviewee would ask her mother to bequeath a larger share of her estate to them—a transfer that follows the norm that bequests are given from parents to children. This link between inheritances and support shows that the family in terms of parents and their (grown up) children is a solidarity unit, a group within which members are responsible for each other. "We're independent" signifies that siblings belong to independent families, and supporting members of another family introduces a reciprocal relation in terms of gift and debt. But such a reciprocal relation is explicitly unwanted, which again questions the applicability of reciprocity theory to understand inheritances. In sum, bequests are passed on to people who belong to the family and are linked with support, responsibility and solidarity. For this reason, receiving an inheritance signifies family membership, so that a bequest to nephews and nieces would signify a parent/child relationship that does not exist and would thus mark the transfer as "weird." Another respondent expressed a similar view, after I asked him whether he wished to bequeath to his "relatives":

"Well, yes. I mean that's part of being in a family. Each generation helps the succeeding generation. But you have to watch out when you use the word 'relatives'. In the American sense that could include cousins and you know. And we don't feel any connection to those people, though if one were in trouble we would help them the way we'd help a friend." (Int501, heir and testator, age 81) [30]

Here we clearly see the motive of generational family solidarity. For this respondent, a family is characterized by the support given by the older to the younger generation. But, as a solidarity unit, the family encompasses a household and its offspring and hence the interviewee draws a boundary between his family and other relatives. In terms of support and responsibility, the latter are even seen as no closer than friends. [31]

As discussed above, however, quantitative studies show that sometimes nieces or nephews and even in-laws inherit. How can this be understood within the framework just elaborated? There are two potential explanations which draw on the fact that the aunts of those three interviewees in my sample who did inherit as nieces and nephews did not have their own children. First, aunts and uncles who themselves inherited their estate, can pass on their parents' estate to the next generation. In such situations, nieces and nephews in fact inherit their grandparents' estate, as offspring of the original household. Second, childless couples might develop parent/child kinds of relations with their nieces and nephews, as the following quote exemplifies:

"Neither of them ever had children. And my and my brother's relationships with them has made them feel like we were children in their lives. And there is another set of cousins on another side; they probably feel the same way. And we provide some kind of familial outlet to them in the form of children." (Int402, heir, future heir and testator, age 44) [32]

The answer parallels one of Janet FINCH and Jennifer MASON's main arguments that inheritance "is not so much about who 'counts' as kin but about the commitments associated with each relationship, and especially who is treated as a member of the most intimate family circle" (2000, p.58). In this case, the interviewee and his brothers established parent/child kind of relationships by their affectionate behavior towards their aunts. These relationships normalized the bequests. Similarly, in-laws sometimes inherit, because bequeathing is a tie-sign (cf. GOFFMAN, 1971, p.188) that testators use to express their feelings about the in-law having become a full member of the family. Bequeathing to in-laws thus is a strategy to integrate non-kin to the family, which relies on, i.e. exploits, the meaning of inheritances as a type of transfer that is made between generations of a family. The tie-sign can only be understood against the norm to bequeath to one's children. [33]

3.3 Boundary conflicts: Who belongs to the family?

It is not unproblematic that inheritances function as tie-signs. The norm to bequeath to one's offspring also holds with families that have experienced divorces and remarrying. In line with Janet FINCH and Jennifer MASON (2000, p.36), my investigation suggests that difficulties arise not from divorce, but from remarrying. I call these conflicts boundary conflicts, because the question as to who belongs to the family is being contested. Such conflicts can arise for two reasons. [34]

First, the inheritance might include a person to the family against the will of other family members. Consequently, some family members fear the inheritance will "leave the family." For example, Int102's grandfather married three times. The third time, he married shortly before his death. At this time, his sons (Int102's father and uncle) were already managing his estate. Some members of the family were resentful, because the marriage entitled his new wife to a third of his estate:

"There was a lot of fighting between his third wife and our family. [...] She wanted more and we didn't want her to have more, because we're the family and she has been third wife." (Int102, heir, age 29) [35]

This case is an example of how the household as consumption unit, and the family as solidarity unit fall apart after remarrying, which results in the contentious situation of who represents "real" family. The interviewee draws a clear boundary by which she excludes the third wife from the family. [36]

Secondly, boundary conflicts can arise if persons who see themselves as family members are symbolically excluded by not inheriting. This happened when Int106's childless aunt left her assets to her sister, Int106's mother. Int106 and her brother asked their mother to pass on the assets to them and planned to set up a trust in the mother's benefit. Thereby, the siblings tried to prohibit their father to gain access to the estate, because he had an affair with another woman at the time. They feared he could marry the other woman and thereby entitle the "outsider" to their aunt's estate. Yet, the siblings had underestimated that their action symbolically excluded their father from the family, and he felt deeply insulted. Again, these boundary conflicts can only be understood against the norm to bequeath to one's offspring, and the consequence that inheritances signify family membership so that bequeathing is an act of boundary drawing, with its inclusive and exclusive consequences. [37]

3.4 Moral conflicts and anxiety: Problems to appropriate inherited assets

Boundary conflicts are maybe the stereotypical inheritance conflict in the public eye. Yet my analysis revealed another highly salient personal conflict that is associated with inheritances. Eight out of my twenty-two heirs had difficulties to justify and see a purpose in inherited assets, which is why they faced problems to appropriate their inherited assets—to make them theirs. In stark contrast to generally held positive connotation of inheritances as gift, compensation or stroke of luck, these heirs held deeply negative accounts of inherited assets as "blood money," "fraud" and "unachieved wealth." Among these, the latter was the most common; heirs felt they would enjoy the merits of other people's work:

"I couldn't enjoy it, because it was what these people had worked for. And to really know what to do with it or how—I mean ideally your labor earns you capital and your capital buys you food or whatever. It was, it was—fraud." (Int101, heir, age 45) [38]

In line with meritocratic principles, the interviewee expresses that one's food, which I take to represent the standard of living, should be the product of one's labor, otherwise it is "fraud." Judged against these meritocratic standards, inheriting entitles a person to the merits of other people's labor and thereby designates them as immoral. This moral conflict becomes particularly burdensome if heirs depend on inherited assets to maintain their family's standard of living:

"I work and in some sense I pretend that all that money that has been given to me and will be given to me doesn't exist. Or I don't pretend that I worked and done it all by myself, but I work as though I'm supporting my family. And I am, to a certain extend. I live in this duality, where I think about what we have and what we can do based upon my income." (Int403, heir, future heir & testator, age 46) [39]

A single interviewee who inherited at age twenty-one, after both his parents had died within the same year, faced a related but even more fatal problem to appropriate his inheritance; he felt it was "blood money":

"I felt very guilty about the money. I felt like it was blood money. I felt like everything that I got from it, I got because my parents died. So I would think of me having a cocktail or having a meal and I would think: 'Well, they died, so I could do this'. And that felt awful to me." (Int107, heir and testator, age 47) [40]

The term "blood money" is frequently used to denote money earned by selling weapons or drugs; it is money that is earned on the basis of other people's suffering, i.e. their "blood." Hence this respondent's feelings of guilt about possessing inherited assets do not stem from being entitled to the merits of his parents' work, but from the fact that he benefited financially from their death. This violates his moral standards, according to which other people's suffering or death should not be the basis of personal enrichment. [41]

Particularly in interviews with future heirs, I encountered statements that parallel the depiction of "blood money." Future heirs implicitly face a moral dilemma, when they imagine future gains that result from the inevitably associated death of a family member. This can create anxiety when testators wish to discuss their bequest plans with potential heirs, because the latter feel highly uncomfortable about discussing a future gain with the person who has to die, to realize this gain. Paradoxically, testators wish to talk with the future heirs about the inheritance, because they are well aware of the fact that the appropriation of inherited wealth is difficult. They wish to prevent later anxieties by communicating the purpose of bequests and thereby also hope to ensure a "responsible" use. Such considerations are well advised given that some heirs face problems to appropriate their inheritance because of anxieties about the expectations of a responsible use of inherited assets:

"It's a huge responsibility and you don't quite know what to do with it. And it took me about three years to go and even speak to the bank person of the account who manages it, just because it felt overwhelming to deal with it." (Int202, heir, age 24) [42]

This heir did not know how to use her inheritance, and feared not meeting the demands of the "huge responsibility." Responsibility here means that other people hold expectations about an appropriate use of inherited assets and the heir has to ensure that they are not disappointed. Yet, if the particular expectations are unknown and intransparent, heirs face problems to appropriate inherited assets. In this case, the heir was so overwhelmed that she ignored the assets for years. [43]

What are heirs who are unable to appropriate their inheritance doing with it? As we have already seen, some simply ignore their inheritances. It might seem as if an alternative solution would be to give it away in form of a charity donation. Yet, this is not an option for the heirs interviewed, because the assets were explicitly left to them in person. Not accepting the inheritance would mean to deny the sign of affection along with the relationship implied by the tie-sign:

"I guess my feeling was that I hated the situation and I felt very uncomfortable in it, but I didn't see it as something I could get out of. [...] And I dimly knew that my parents wouldn't want that anyway. As bad as I felt, I didn't feel good about having the money and spending it but wouldn't have felt: 'Well I did the right thing, 'bye mom and dad', if I gave it away' either." (Int107, heir and testator, age 47) [44]

This heir expresses that to donate his inheritance to charity would have meant to devalue his loss. He even goes so far as to compare giving away the inheritance to giving away his parents themselves by saying, "'bye mom and dad." He had to keep or spend the assets, and chose an extreme, i.e., he "burned through it":

"I just burned through the money. I just wanted to get rid of it."

"So I spent two years just hanging around. I had a really good looking girl-friend and I drank a lot, I did drugs, we had sex a lot and I didn't have to do anything. I read a lot of books. I was very depressed and lost. And it was really healthy for me when I went back to school."

"Once I was making my own way, I was glad that it's gone." (Int107, heir and testator, age 47) (These are three separate interview passages) [45]

If there were any behavior that suggested inherited assets had no special social meaning it would be this heir's. It seems as if he treated his inheritance like any ordinary bonus. Interestingly though, he was happy when the short period of ecstasy was finally over. I offer the interpretation that by "burning through" the inherited assets, this heir serves in fact two competing demands. On the one hand, he spends the assets that were meant for him. On the other hand, he spends the money on short-term enjoyments that leave no trace and do not contribute to his long-term standard of living, even though consuming "blood money" and being economically dependent on it was a very depressing experience. Taken from this angle, this heir's behavior looks quite different than wasting an ordinary bonus. And, on the basis of this limited single case, we may assume that the stories about irresponsible and immoral heirs, who spend their inheritance on alcohol and drugs for example, might have more complex and morally integer standards than is generally assumed. [46]

Int107 is certainly an extreme case. Most heirs who are unable to either appropriate or to give away the inherited assets, tend to disregard them. They save the assets in some bank account and some simply wish to pass them on to the next generation. By doing so, heirs do not use the money for their personal gain, while they see it as morally permissible to use them for supporting one's children. [47]

Why does a minority of heirs face moral conflicts? My analysis suggests that heirs who face a moral conflict are not able to define the inheritance as "special money" and that this is a function of young age. Not a single heir who inherited at forty years of age or older reported any of the above-mentioned problems. The driving factor behind age is that young people wish to achieve independence and a social status by their own efforts. But inheritances threaten to undermine such achievements—a problem that older heirs who already did establish themselves do not face. This means that moral conflicts can be overcome when heirs get older and become economically independent. But there is more to age. Young heirs tend not to have their own children for whom they could spend the inherited assets without profiting themselves. Having their own children also puts people in the situation to think about inheritances from the perspective of a testator and to thereby understand the purpose of inheritances. And finally, young heirs have had less time to talk about inheritances with testators and learn about the purpose of inherited assets. [48]

3.5 "Safety net" and capital: Purposes of inherited assets

The majority of my interviewees did not report any problems to appropriate their inherited assets and saw various purposes for them. All these purposes have in common that inherited money is distinguished from wealth, which is seen as an earned reward. Inheritances in contrast are understood as capital:

"To outright spend it without any return is not something I know my family members would do. It's not play money, it's for productive use I would say." (Int202, heir, age 24) [49]

The first sentence of this quote describes an aspect of "burning money," i.e., to spend money on something that does not last. Inheritances in contrast, this respondent formulates, should be spent for things that create a "return." She draws a boundary between "play money" and "productive use," with the former being associated with free time and fun and the latter with work and earning a livelihood. This means, rather than representing returns for care and love, for example, inheritances are financial capital that enables the owner to become productive and generate "returns." Alternatively, some interviewees described inherited assets as "safety net," for emergencies and situations of need. Such inheritances were sometimes even regarded as important for attenuating heirs' risk aversion. It is well known that people who come from lower class families are more risk averse and thus tend not to invest in a lengthy academic education (BOUDON, 1974). Inheritances are also seen as having the purpose of making heirs feel less restrained and strive for their goals. Finally, according to a less frequent view, inheritances were also seen as family-glue that helps to "reinforce the family connection" (Int501, heir and testator, age 81). Int501 achieved this goal by building a country house in which the family frequently meets and which is intergenerationally owned. [50]

Testators express similar views on the purpose of inheritances. From their perspective, however, this translates to expectations on how their assets should be used after their death. While testators purposefully take actions to enforce these expectations by measures such as setting up trusts, they similarly emphasize not to hold any such expectations and declare the heirs' freedom to spend the inheritance however they like. This results in ambivalence between the topics of responsibility and freedom:

INT601: "They can do with it whatever they want. I mean I have my own opinions but there is not gonna be a limit. We don't say in the will we don't want them to do this and that."

Interviewer: "But still you said you don't want them to blow it."

INT601: "If it turns out if that's what they did. They're pretty responsible kids. So, you know if they were drug addicts or something like that I would think differently. If their history was such that I thought they were irresponsible and would be irresponsible then I might change it. But I feel they are fairly responsible so far, so they can do whatever they want." (Int601, heir and testator, age 56) [51]

This interviewee and her husband plan to pass on their estate to their children in two steps: first, when they reach their mid twenties and again during their early thirties. Thereby, they want to assure a certain "maturity" and that their children have money for different life-phases. Yet, she declares not to have any expectations, but that her children can do with the money whatever they want. At a closer look, however, she takes no measures to enforce expectations because her children are "responsible," meaning that they will use the money in an appropriate way without any external enforcement. Another testator similarly denies having any expectations about appropriate usages, but implicitly says the opposite:

"I think that inheritances and things like that, I think they are all money. You can take some portion of the money and enjoy. You know, go on vacation or go on, I mean spend it on something trivial.

But I think that other things, maybe you should invest it in something more meaningful. Whether that be—and I guess maybe my bias is towards to, you know, put it down on a house or a thing that will last. Cause I think that's the intent of an inheritance." (Int108, heir and testator, age 53) [52]

In blank contradiction to the interpretation developed so far, this interviewee suggests to spend inherited money on trivial things such as holidays. However, he qualifies that only "some portion" should be spent in such ways. The rest should be used on something "more meaningful." His example of the "intent of an inheritance" is buying a house. Here we again see the topic of things that last and that are an investment or a financial security, in contrast to those that leave no trace, generate no return, and are thus "trivial." Moreover, a house is maybe one of the strongest symbols of the family, suggesting that the "intent of an inheritance" is to spend it on the family. US testators do not acknowledge holding strong expectations that might be felt as a burden by the next generation. But their language implicitly shows that they do hold such expectations and that these are well in line with the social meaning of inherited assets as safety net, capital and family glue. [53]

3.6 Unachieved wealth versus family money: Justifications of inherited assets

The distinction between inheritances and wealth is important in order to understand how meritocracy is brought to terms with practices of bequeathing and inheriting. Heirs and testators formulate an interesting compromise between the moral virtues of meritocracy and family solidarity. In particular, negative justifications negate that two meritocratic hallmarks are compromised. The productive uses of the inherited assets ensure that the standard of living is self-achieved and the undiminished strive for status achievement proves that the inheritance does not affect the heir's ambition.

"I mean that money allowed me to find a profession I love. But at this point in my life, it's my work that is my income." (Int301, heir and testator, age 61) [54]

This justification reflects the purpose of inheritances to be used as capital. Rather similarly, another heir explicitly states that by saving her inherited assets for her future children's education, she "sort of gotten over the guilt and tried to turn that into something more productive" (Int201, heir, age 28). To describe inheritances as enabling, i.e. to be productive and achieve something, is a frequently recurring topic, particular among those heirs who use the inheritance to finance their education. [55]

Some heirs also formulate positive justifications. These refer to family solidarity as a virtue, which reflects their purpose as financial security. In particular, this meant that my interviewees emphasized to be in a situation of need or that they use the inheritance to support family members. These justifications differ from the ones above because they define situations that qualify for a person to receive financial support in a positive vein. All these justifications involve a notion of inherited assets as "family money" in contrast to personal property. Some heirs mention this explicitly:

"I guess I try not to think of it as mine so much as opposed to family money that you use for now and to preserve the next generation. I think it's a privilege of my grandparents to earn it on the one hand, but also to receive it from the generations before them. And it's a perpetual thing. I guess the way I think of it, is it's not mine.

I think it's probably the only way to handle it. Otherwise there is too many moral dilemmas. I mean maybe it's true in that regard. It's hard to know you have this money and I haven't earned it and I'm not worthy of it or whatever else. But, I just don't think like that, I guess." (Int202, heir, age 24) [56]

In sharp contrast to the earlier quoted interviewees who used words such as "fraud," this interviewee explicitly denies the applicability of meritocratic standards, even though she recognizes the possibility of a moral dilemma. Instead of facing this dilemma, however, she sees her inherited assets as family money and thereby distinguishes them from personal property. She characterizes family money as assets that should be spent for family members and that are a "perpetual thing"; the grandparents gave, just as they received themselves. Hence, we can conceive of family money as financial assets that are used to enable the family to fulfill its solidarity function and that are passed from one generation to the next. The money stays with the group, but is managed by the individual for current appropriate uses. This stands in sharp contrast to existing accounts of inheritances. Janet FINCH and Jennifer MASON (2000, p.98), for example, emphasize that they have found nearly no accounts of family money in their qualitative investigation in the UK. [57]

That said, my interviewees' attempts to justify inheritances involve a fragile balance. Defining inheritances as family money involves a fine-grained distinction between unachieved wealth and support. The distinction is highly contingent, because it can be subject to interpretation:

"You know my son just came to me the other day and asked if I buy him a house one day. I said: 'Sure, I buy you a house'. My wife stepped in and said: 'No you buy your own house. But we're happy to help you.' And if I can help, I will." (Int401, heir, future heir and testator, age 42) [58]

This quote demonstrates the importance of interpretation. First, the interviewee describes the well-explored topic of how it would be inappropriate to finance a grown-up person's standard of living; the son has to buy his own house. Yet, supporting his son is justified as an instance of family solidarity. Thereby, a similar transfer changes its moral status from being inappropriate to being justified. Such quotes should not be interpreted as socially desired post-hoc justifications, but as typical attempts to balance meritocratic ideals and the wish to support family members. [59]

3.7 Keeping it invested: Usages of inherited assets

What do heirs do with their inherited assets? A frequent strategy is to keep it invested, by which inheritances fulfill their purpose as financial security. The investment generates interest that might be used to pay for education, for example. In some cases, heirs put the assets in trusts or bank accounts for their children or grandchildren. When those reach a certain age or when the current holder of the estate dies, the inheritance passes on to the children without having been spent. Some use it to actively support their own children and grandchildren. By interpreting such spending as supportive use of family money, moral conflicts are being avoided. There are, however, also heirs who spend parts of their inherited assets for themselves. Particularly younger heirs spend their inheritances on education. Again, such uses of inherited assets are subject to interpretation. One heir, for example feels bad for using her inherited money on rent:

"Yeah I feel like it's a waste. It's odd, you know if it was going like to tuition, like if the tuition here were $20,000 or $40,000 per year then I might feel differently about it, but this is going to rent." (Int201, heir, age 28) [60]

This heir feels bad for spending her money on rent, but would feel good to spend it on tuition fees. We again see the topic of tuition as investment in the future that generates returns, while rent is not enabling, leaves no traces, and signifies economic dependence. Overall, the interviewee feels bad for spending her inheritances in an inappropriate way. However, there is room for interpretation, as the interview with another student shows:

"I mean basically it allows me, you know, the financial security to be in graduate school and not have to worry too much about—you know I make some money from working, but I have this other money to fall back on. I'm able to live by myself rather than having roommates." (Int103, heir, age 27) [61]

This interviewee also uses his inherited assets to pay rent and even acknowledges affording a comparatively comfortable lifestyle. But in contrast to the earlier quoted student, this heir defines paying rent as a part of his educational expenses and thus does not feel bad about it. This demonstrates how situation specific interpretations leave spaces for individuals to find their personal balance between the two moral virtues of meritocracy and family solidarity. [62]

The same need for interpretation arises in cases where people use their inherited assets to buy a house. Since such use directly increases one's standard of living, it demands justification. But a house is rather interpreted as real estate, and is thus seen as another form of investment. While people do enjoy the standard of living that a house provides, heirs feel that the inherited money itself, the "important parts of the proceeds of a human life" (Int501, heir and testator, age 81), are preserved and passed on to the next generation:

"What we're doing is we're buying an apartment with the money of the trust and some other money. And we gonna rent it to [daughter] and her husband when they get married. But we're basically investing the money as an investment." (Int601, heir and testator, age 41) [63]

In addition to illustrating the point made above, this quote also shows another important aspect of investing inherited assets: the interviewee differentiates between the "money of the trust" and "other money." Most heirs in my sample do not intermingle their inherited money with other financial assets, but "earmark" (ZELIZER, 1994, p.21) inherited assets by investing them in separate bank accounts, trusts or funds. This shows that the justifications given above were not post-hoc answers, which were invented to meet my interview questions. The inherited assets are felt to be special so that a need arises to distinguish them from other money. One couple used its inheritances, which had been invested in separate bank accounts, to buy a country house as a family residence. Upon my question why they wanted to use particularly these inherited assets, the husband answered:

"Because I felt there was a direct connection from that money. It represented the grandparents; that the grandparents had been a part of this whole process even though they weren't alive." (Int501, heir and testator, age 81) [64]

4. Discussion and Conclusion: The Moral Ambivalence of Inherited Financial Assets

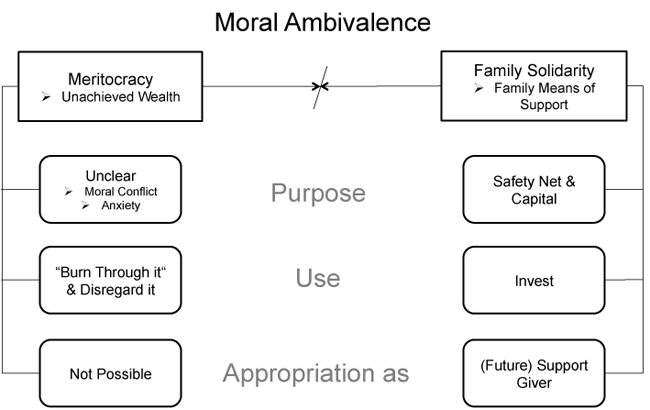

This inquiry raised the question of what inherited financial assets signify to heirs and testators and how this shapes their conduct. Existing social research, mostly done by economists and sociologists, conceptualizes the meaning of inheritances as gifts, compensations or random financial leftovers. Yet, such positively connoted conceptualizations cannot account for a large part of the observations made here. Why would heirs emphasize not to gain personally from inheritances if they were gifts? Why would testators be concerned with an heir's responsibility, if they were seen as earned compensation or as random financial leftover? And why would particularly young heirs face moral conflicts after inheriting and describing their inherited assets in deeply negative terms as "blood money," "fraud" and "unachieved wealth"? This explorative inquiry comes to the alternative conclusion that the social meaning of inheritances is situated between seeing such assets as unachieved wealth and family means of support (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: The social meaning of inherited assets as moral ambivalence [65]

On the one hand, the moral standard of meritocracy demands appropriation of property by means of labor rather than by succession. Inheritances thus represent the achievement of another person, which questions their legitimacy and makes their appropriation difficult. This social meaning of inheritances as unachieved wealth helps to explain many of the observations discussed, most importantly the moral conflicts some heirs face, but also the negative justifications that heirs give to emphasize how they meet the hallmarks of meritocracy, i.e., economic independence and ambition. On the other hand, supporting family members is also seen as a moral virtue. The family is arguably still the most important solidarity unit of our contemporary societies. These supportive bonds remain even when children are grown up. But, bequeathed assets differ from common familial support in that there is not necessarily a situation of need and hence no obvious purpose for which the money should be used. Inherited assets are instead seen as "family money," i.e. a family's collective means of support, which are used when need arises. In this regard, bequeathing still parallels the inheritance institution of agrarian societies, but what is being passed on is not the means of production, but the means of support. Bequeathing is the last act of parenting, as one of my interviewees expressed it, because it is the succession of the status as support giver along with the resources and responsibilities that belong to this status. Seeing financial inheritances as family means of support also helps to understand many observations of this analysis, such as why inheritances signify family membership or why heirs feel badly for spending their inheritance on rent but not for spending it on education. [66]

It is important to note, however, that the social meaning of inheritances is not an either/or dichotomy, but a continuum of moral ambivalence within which heirs need to find a personal compromise. Such a compromise is not static and culturally pre-given. Instead, each heir's actions leave room for interpretation, such as seeing rent as part of one's educational expenses and hence an investment in the future or a waste that leaves no trace. Only heirs who find a compromise between the two poles can successfully appropriate their inheritance, whereas those who fail to find such a compromise face moral conflicts. Testators use the word "responsible" to describe a good balance between meeting the expectations on the use of family money and being individually free enough to actually put the inherited assets to use. [67]

This theoretical account is the result of an exploratory, qualitative investigation. While its theoretical generalization seems plausible, it is empirically questionable because of the limited sample the theory is grounded in. Most importantly, there are concerns with reference to the high education level, and local clustering of heirs on the US East Coast. Future research thus needs to establish whether the patterns unearthed also hold within other US regions and whether the moral ambivalence of inherited assets is felt throughout all social strata of the US population. Another limitation concerns recent economic developments. The interviews were conducted during the very beginning of a financial crisis and private investors such as my interviewees had not felt personal consequences at the time. How did the financial crisis, which crushed so many people's abilities to make a living, affect their relation to inherited assets, or maybe even forced them to use up the family's safety net? These limitations all focus on the US, but another question is how far my theoretical account generalizes to other countries. A principal tension between the standards of meritocracy and family solidarity characterizes many societies, but if we follow Jens BECKERT's (2008) analysis of parliamentary debates on inheritance taxation, the value of meritocracy is stressed not in all countries as much as it is in the US. An international comparison could show whether in other countries heirs experience a similarly strong moral ambivalence between two, or maybe more, competing moral standards. A final topic for future research is how the succession and social meanings of inherited personal items (e.g. LANGBEIN, 2002) and family companies (e.g. BREUER, 2009, Ch.9) relate to that of financial assets. [68]

Acknowledgments

I wish to thank Jens BECKERT, Sarah CAROL, Klaus EDER, John MOLLENKOPF, Doris SCHAEFFER, Nona SCHULTE-RÖMER, Philipp STAAB and Viviana ZELIZER for helpful comments and ideas.

Interview Guideline

Could you please give me a general picture of yourself?

Family: parents, siblings, spouse, children, grandparents etc.

Family's immigration background

Age and place of upbringing

Work and education

Since the topic of the interview is inheritances, I am interested in your experiences. Please tell me about your inheritance experiences.

Age at inheritance

Inheritance from whom

Who else inherited

What was being bequeathed

What do you do with the inheritance

How do you store it

Have there been any conflicts on inheritances?

What was the contentious topic

Who was involved

What were their claims

Was the conflict solved and how

When did the conflict start

Have you also inherited personal property?3)

From whom did you inherit it

Who else inherited objects

Can you give me concrete examples

Why is the piece important to you

Was the object passed on in the family since more than one generation

Is there a story to the object

(Added for the Summer 2008 Sample)

How do you feel about owning property you did not achieve yourself?

Have you thought about your bequest?

To whom

What do you consider when you think about your bequest

Do you have expectations how the bequest should be used

Do you feel an obligation to bequeath