Volume 16, No. 1, Art. 20 – January 2015

Strangers but for Stories: The Role of Storytelling in the Construction of Contemporary White Afrikaans-Speaking Identity in Central South Africa

P. Conrad Kotze, Jan K. Coetzee, Florian Elliker & Thomas S. Eberle

Abstract: This article explores the application of an integral framework for sociological practice to a case study of White Afrikaans-speaking identity in South Africa. In addition to the introduction of the framework, identity is conceived as a multi-dimensional phenomenon which is formed and shaped biologically, psychologically and socially. Using the empirical examples of the case study, the socially constructed aspects of identity are interpretively investigated. The stories and their narrative repertoires, structures and contents are integrally reconstructed and analysed by means of an approach that includes in-depth interviews, a hermeneutical interpretation and the contextualisation of these stories within the broader meta-narrative of South African history. The analysis demonstrates that White Afrikaans-speaking identity has diversified since the end of apartheid in 1994, i.e. the self-definitions and self-understandings of White Afrikaans-speakers do not (exclusively) refer anymore to the formerly dominant notion of the Afrikaner. The analysis concludes that there exist three contemporary White Afrikaans-speaking identities in South Africa, namely the Afrikaners, the Afrikaanses, and the Pseudo-Boers.

Key words: integral sociology; ontological dimensions; epistemological modes; identity; narrative repertoire; storytelling; phenomenology; hermeneutics; Afrikaner; Afrikaanse; Pseudo-Boer

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. A Framework for Integral Sociological Practice

2.1 Conceptualising identity as a multidimensional phenomenon

3. A Theoretical Foundation for Studying the Intersubjective Ontological Dimension of Identity

3.1 A phenomenologically informed approach to the study of social reality

3.2 The role of storytelling in the construction of identity

4. Methodological Considerations/Methods Used

4.1 Sampling and ethical considerations

4.2 Data collection and analysis

5. The Case of White Afrikaans-Speaking Identity

5.1 The Afrikaanses

5.2 The Pseudo-Boers

5.3 The Afrikaners

6. Conclusion

This article represents the conclusions arrived at during a full-time study carried out at the University of the Free State (South Africa) during 2013. Conrad KOTZE served as primary investigator and conceptualised the ontological and epistemological frameworks introduced in Section 2. Jan COETZEE was the research supervisor and directs the postgraduate programme "The Narrative Study of Lives" at the same university's Department of Sociology. Along with Florian ELLIKER, who served as co-supervisor, he was responsible for assistance and guidance during the development of the theoretical and methodological foundation that was put into practice during the study. Thomas EBERLE is an external examiner in the programme and provided significant editorial input, especially relating to phenomenological theory and practice. [1]

In the spirit of interpretive sociology the contents of this article are not presented as universally valid "facts", but as plausible conclusions arrived at by means of a reflexive attempt to integrate various aspects of social reality as it manifests itself to everyday perception. One particular aim was to develop an integral understanding of identity as manifested in the socially shared realm of paramount reality. This was done by considering the interplay between subjectively experienced perceptions of reality and objectivated interpretations thereof during the intersubjective construction of identity. Such an approach called for an integral conceptualisation of identity as being constituted biologically, psychologically and socially, the outlines of which are presented in Section 2. After this introduction to the multidimensional nature of identity we conduct an interpretive investigation of the socially constructed aspects of identity in Section 3. Section 4 explores methodological and ethical considerations that played a role in the implementation of a recent study of White Afrikaans-speaking identity, while Section 5 presents the conclusions arrived at during the course of this study. [2]

The article aims to illustrate the implementation of an integral approach to sociological research. This integral approach attempts to include what are argued to be universally present dimensions of experienced reality within a meta-theoretical approach to the investigation of a given phenomenon (in this case identity). The article further aims to illustrate ways in which complementary modes of knowledge generation (objective description, intersubjective understanding, and subjective witnessing) can be acknowledged and utilised in the field of sociological research. These divergent ways of generating knowledge represent foundational modes of consciousness that each play a role in the daily construction and maintenance of social reality. We argue that acknowledgement can be given to each of these epistemological modes by adopting a reflexive praxis that includes the empirical collection of objectivated "facts" (in the form of historical, demographic, economic, etc. data), intersubjective investigation (a hermeneutic approach to understanding the narratives of others), and phenomenological reduction (the researcher's subjective interpretation of the nexus of "facts" and meanings collected during the research process). Thus the main aim of this article is to contribute to the debate regarding the nature of an integral sociological practice grounded in a holistic foundation of human knowledge. It is because of this motivation that the argument encountered in Section 2 of this article is not limited to issues pertaining to qualitative sociology, but explores meta-sociological issues that are relevant to this stated purpose. [3]

2. A Framework for Integral Sociological Practice

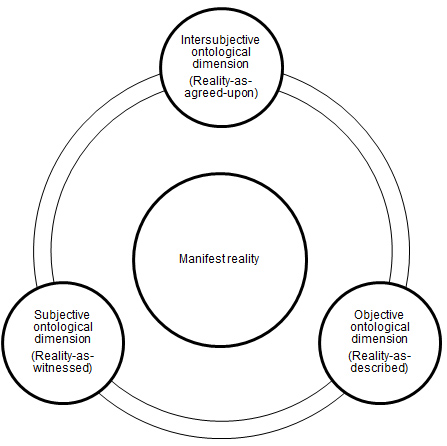

For the sake of the logical cohesion of the following arguments, it is necessary to briefly illustrate an integral framework for the study of social reality developed by the primary author of this article. Although various models for an integrated sociological paradigm exist (see especially the work of RITZER, 1975, 1981, 2012), they have all been largely limited to what this framework refers to as the objective ontological dimension of reality. This means that these models are limited to the acknowledgement of a single sovereign pathway to knowledge, namely the positivistic collection of empirically measurable "facts" concerning social reality. Any alternative sources of knowledge are instantly discarded. The framework illustrated in Figures 1 and 2 indicates that most of our scientific knowledge, though earned through disciplined toil in the realm of empirical description, can ultimately generate only partial truths. As has been made clear by the various constructivist and relativist movements of the 20th century, the collection of "social facts" from within the objective ontological dimension of reality, however "reflexively" defined, entails reducing the holon1) of manifest reality to one of its constituent ontological dimensions and mistaking this one-dimensional abstraction for the whole. [4]

The intersubjective ontological dimension is seldom tapped into, while the subjective has practically been lost due to the widespread devolution of phenomenology into a mere scientific methodology through its co-optation by social scientists. Phenomenology can never be reduced to a sociological (or any scientific) methodology, due to the fact that the practice of phenomenology is geared toward investigating the pre-reflexive constitution of reality through the supposedly universal structures of human consciousness. This intrasubjectively situated endeavour is irreconcilably unempirical and clearly contrasted to the study of the intersubjective construction of social reality, which is what most so-called phenomenological sociologists are actually engaged in (DREHER, 2009; EBERLE, 2014). The main premise of the primary author's integral framework is that reality as naïvely perceived represents a holon of manifestation that simultaneously envelopes three ontological dimensions that dialectically and undivorcibly inform the nature of any object's being-in-the-world. These ontological dimensions are referred to as the subjective, intersubjective and objective ontological dimensions respectively, and can be illustrated as follows:

Figure 1: The three ontological dimensions [5]

Embracing such an integral model of reality allows for the problematic break between objectivity and subjectivity in sociological research, most concretely manifested in the ongoing debate between the scientistic2) reductionists and relativist constructivists (LETHERBY, SCOTT & WILLIAMS, 2013), to be mended. Instead of blindly following either the path of scientistic reductionism, the treading of which tends to lead one away from all questions of meaning, or that of extremist constructivism, which often argues in favour of absolute relativism and universal variability, such an integral framework allows one to be reflexively aware of the fact that reality extends beyond the empirically measurable, but that it is never completely divorced from it. An integral view of reality allows the researcher to investigate a given phenomenon holistically by reflecting not only on what is true about that phenomenon (objective ontological dimension, empirically given), but also on its goodness (intersubjective ontological dimension, constructed through mutual understanding) and its beauty (subjective ontological dimension, grounded in the consciousness of the individual subject). These three dimensions of reality have been latently present in Western thought since the dawn of Greek philosophy (in the form of ARISTOTLE's "transcendentals"), right through to the work of Immanuel KANT (1998 [1789], 2000 [1790]), whose critiques of pure reason, practical reason and judgement are oriented to each of these aspects in turn, and those who have built on his philosophy (REATH & TIMMERMANN, 2010). Of contemporary philosophers, Jürgen HABERMAS (1984 [1981]) has done the most to highlight the need for an active acknowledgement of the interrelated questions of objective truth, subjective truthfulness and intersubjective justice when interpreting reality. The framework presented above makes such an integral approach possible and does so in a manner that we argue to be inductively informed by the conclusions of various thinkers throughout the history of philosophy and science. [6]

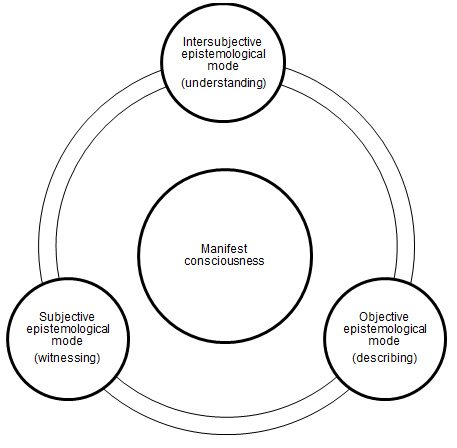

When focusing on a single ontological dimension of a given phenomenon's manifestation, as we stress the intersubjective ontological dimension of identity throughout the remainder of this article, the other dimensions remain as irreducible aspects of reality. This is the case because consciousness in turn manifests as an irreducible holon comprising three complementary epistemological modes. Consciousness seems to be structured correlatively to phenomenal nature, which leads to the existence, correlating to the three "outside" ontological dimensions of manifestation, of three "inside" epistemological modes of consciousness. Thus objectivity, subjectivity and intersubjectivity exist not only as ontological dimensions of being, but also as correlative epistemological modes of knowing. These epistemological modes are encountered in the possible orientations of human consciousness to the universe that it constantly perceives. During everyday perception, the relationship between consciousness and perceived reality alternately adopts the peculiar epistemological character of subjective witnessing, objective describing or intersubjective understanding. The epistemological modes, which describe modes of "knowing" in a similar way that the ontological dimensions describe dimensions of "being", can be illustrated as follows:

Figure 2: The three epistemological modes [7]

Just like the three ontological dimensions represent irreducible aspects of reality, the epistemological modes represent irreducible modes of consciousness. They dialectically constitute the structure of the unitary "lens" through which human beings perceive reality. Only by reflexively activating all three of these modes simultaneously can empirical knowledge (obtained by means of the objective epistemological mode) be enriched by incorporating issues concerning the justice or social goodness of knowledge, as well as the relationship of knowledge to normative issues like morality, aesthetics and the desirability of the effects of knowledge. Applying either one of these epistemological modes to the neglect of the others will always result in partial knowledge, condemning the researcher either to the realm of metaphysics (overemphasis on subjective witnessing), impotent relativism (overemphasis on intersubjective understanding) or scientistic reductionism (overemphasis on objective description). The skeleton of such a truly integral approach applied to the generation of sociological knowledge can be found in the works of Pitirim SOROKIN, whose writing on altruistic love, virtue and solidarity transcends the empirically measurable domain of the objective ontological dimension into that of the intersubjective (JEFFRIES, 2005). SOROKIN (1948, 1954) however argued for the development of different sociologies oriented to these different realms, whereas the primary author assumes the possibility of a single ontological and epistemological framework that can be modified at the theoretical and methodological levels in order to make any phenomenon the object of integral analysis. The rest of this article illustrates an attempt to do just that, as contemporary White Afrikaans-speaking identity is firstly acknowledged as a multidimensional phenomenon, after which its intersubjective ontological dimension is integrally investigated. [8]

2.1 Conceptualising identity as a multidimensional phenomenon

Contemporary sociology finds itself in the midst of an "identity crisis", a phrase referring to the use of the term "identity" for a vast range of often mutually irreconcilable conceptions (BRUBAKER & COOPER, 2000). Part of this state of affairs is a one-sided focus on either the so-called "hard" or "soft" dimensions of identity. For an integral sociological approach interested in taking into account objectivating processes, a radically one-dimensional view of identity as purely subjective conceives it as too ephemeral to be the subject of fruitful sociological analysis. Such a biased understanding of identity leaves sociologists ill-equipped to interpret the often coercive ways in which identity is manifested in the political and cultural realms. The well-documented influence of physiological factors on the manifestation of identity, by means of processes that are currently envisioned as taking place beyond the intervention of reflexive consciousness, is similarly ignored (FAUSTO-STERLING, 2010). Thus the concept of identity could not merely be deployed as a concept of analysis during this study, but had to be seen as itself representing a problematic aspect of social reality. However, since identity is the term colloquially applied to the nexus of phenomena that represent this article's object of study, we are in need of at least some degree of definition before an integral sociological investigation thereof can commence. [9]

With no universally accepted definition available, this section represents an attempt to develop a conceptualisation of identity that is in line with the ontological and epistemological frameworks previously discussed. We thus argue that an adequate understanding of identity is an integral understanding that acknowledges the various insights offered by fields ranging from neuroscience to psychology, sociology and beyond. Before we move on to our main focus, the intersubjective ontological dimension of identity, we thus put forward a brief definition of identity as a concept capable of being subjected to integral sociological analysis. Such a definition must acknowledge not only the social, but also the biological and psychological aspects that play a role in its manifestation as an experienced constituent of reality. While such a discussion may seem superfluous in the context of a study focusing on the socially constructed aspects of identity that represent the phenomenon's intersubjective ontological dimension, we would like to remind the reader of the indivisible nature of reality. Thus the unitary nature of the holon needs to be acknowledged even as its parts are studied in "isolation"; even if such a situating of the object of study serves only to raise reflexive awareness of the dangers of dislocated abstraction and serves to inform future research into the other ontological dimensions of identity. [10]

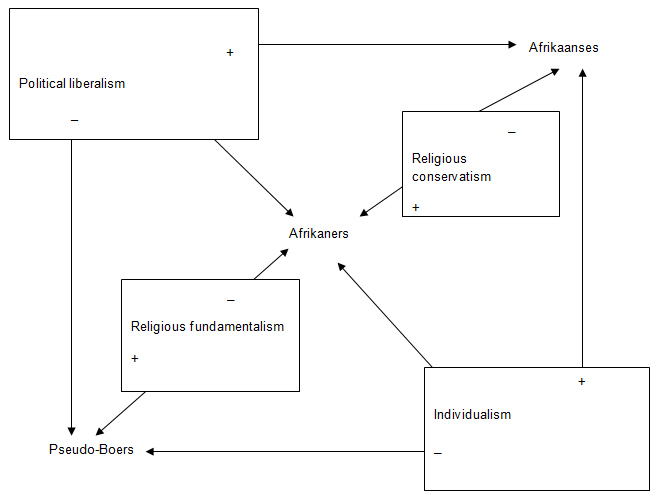

Firstly, the evolutionarily emergent (and thus at least partially biological) nature of identity needs to be acknowledged (NELSON, 2005; SHEEHAN & TIBBETTS, 2009). Human personal identity gradually emerged out of the ongoing interplay between biological evolution, the emergence of higher consciousness, and the development of complex modes of social organisation during the history of Homo sapiens and its antecedent species (BREWER & CAPORAEL, 2006; LUCKMANN, 1983). Thus, identity is historically embedded in a nexus of biological, psychological and social factors. This combination of factors gives rise to that peculiar set of relatively stable, but modifiable perceptions regarding an individual's place in his or her life-world that we call identity (JOHNSON, 2000). Though personal identity seems to be present to various degrees among many non-human species, exhibiting exceptional complexity especially in the case of certain cetaceans and other primates, it has reached a typical state of development in Homo sapiens. This typically human case of identity, manifested experientially in the perception of a relatively clearly delineated, subjectively perceived "me", correlates with the degree of development of both the physical structure of the triune human brain and the increasingly complex social structure of human collectivities (LUCKMANN, 1983; SEDIKIDES, SKOWRONSKI & DUNBAR, 2006; TOMASELLO, 2009). Thus, identity can be analysed within various ontological dimensions of its manifestation ranging from the subjective when contemplating the nature of "self" through the intersubjective, wherein this study of the socially constructed aspects of identity falls, to the objective when describing physiological structures and processes that correlate with observable behaviour and experienced states of consciousness. Likewise the epistemological modes engaged during the analysis of identity may range from subjective contemplation, through more intersubjective modes such as those used in narrative studies and other branches of interpretive sociology, to the collection of relevant empirically measurable "facts". This article develops an argument in favour of reflexively including all three epistemological modes in any investigation, even when enquiry is limited to a single ontological dimension of a given phenomenon, as is the case in this example. [11]

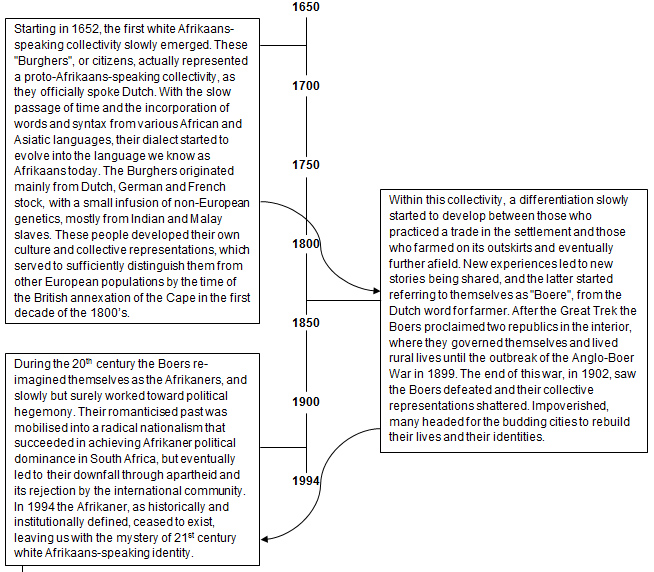

As mentioned earlier, the remainder of the article represents an attempt to integrally investigate the intersubjective ontological dimension of identity (HOWARD, 2005). Intersubjectively, identity manifests through communication with others by means of language, behaviour and other forms of communication, while simultaneously being constructed out of the shared experiences of socially related individuals. We argue that this identity is informed by an intricate intertwinement of subjectively constituted experiences with socially prescribed ideal interpretations of the life-world, along with the interaction of this ever evolving nexus of self-experience with the simultaneously emergent biological human organism, which is also continuously evolving and developing, and its environment (PHIPPS, 2012). Thus, the constitution of identity is seen to be guided by three sets of factors correlated to the three ontological dimensions, namely the subjectively experienced notion of who a person "is" (subjective ontological dimension), relevant socio-culturally situated interpretations of who they "ought to be" (intersubjective ontological dimension), as well as certain biologically informed continua delineating who they "are able to be" (objective ontological dimension). It should be noted that this emphasis on the biological aspect of identity is not unreflexively included, nor is it intended to provide a foundation for determinist or racist reasoning. While the case can and has been made that characteristics of the body influence the nature of consciousness and identity formation in handicapped persons and members of marginalised racial groupings for instance, the role played by the organic aspect of the human being is rather acknowledged in line with recent research that includes newly discovered and little understood subtle energy fields in its conception of the human body (SHELDRAKE, 2013). The possible correlations between the properties of these energy fields, which vary considerably from one person to the next, and perceptual experience are raising exciting new possibilities in the newly emerging science of consciousness. Ground-breaking work is opening up the possibility that various levels and altered states of consciousness, as widely accepted by the great spiritual traditions of the world, may be scientifically (or at least phenomenologically) investigated from within the context of an integrally informed post-metaphysics (CHALMERS, 2010; WILBER, 2007). Nevertheless, this nexus of self-experience (made manifest as a whole only by means of the interplay between the physical environment [including the body], socially shared meaning-frameworks and individuated consciousness) is continuously communicated to others through behaviour, language and other means. Our sense of self is also maintained and modified according to feedback from various ontologically situated sources. These sources range from personal insights, through office gossip, to scientific data and divine revelation (HECHT & HOPFER, 2010). The individual body, as its material correlate, also continuously acts upon and reacts to the opportunities implicit in its constitution and present in its environment. [12]

In full light of this multiplicity it is necessary to analyse identity both phenomenologically and structuralistically. The manifestation of identity is informed both by subjective experience and intersubjectively shared meaning-frameworks, accompanied by a correlating degree of evolutionary development of physiological structures. To successfully navigate the multidimensional nature of identity, it is thus necessary to develop theoretical and methodological frameworks that are sensitive to ontological dimensions of reality ranging from the subjective to the objective. Such a theoretical foundation for the study of identity can be constructed out of the tenets of Alfred SCHÜTZ's phenomenology of the social world and the sociology of Pierre BOURDIEU, as will be illustrated in Section 3.1. [13]

3. A Theoretical Foundation for Studying the Intersubjective Ontological Dimension of Identity

Though the influence of both subjective (orientation to reality that radiates out from the isolated experiencing subject) and objective (orientation to reality that seeks to establish the inherent characteristics of "outside" phenomena, free from subjective interpretation) orientations to reality are acknowledged, this study is conceptualised to integrally investigate the intersubjective ontological dimension of identity3). When focusing on the socially constructed aspects of identity, it becomes necessary to affirm the ontological primacy of the intersubjectively constructed world-as-agreed-upon over both empirical science's world-as-described and the individually subjective world-as-witnessed, both of which are dealt with in greater detail by other fields of epistemology. However, it should be noted that even as we are focusing on the intersubjective ontological dimension of identity, the methodological approach must remain anchored in all three epistemological modes in order to gain integral insights. Thus, from here on the various subjectively and objectively tinged tendencies occurring within the intersubjectively constructed world-as-agreed-upon, instead of the pure ontological dimensions of subjectivity and objectivity per se, are meant wherever these terms are used. [14]

Underlying this ontological shift toward intersubjectivity is a phenomenological definition of the self. This definition holds that, rather than being merely another physical object in a universe full of physical objects, the self also constitutes the very datum of experience through which meaning is ascribed to the universe and the objects perceived within it (SCHÜTZ, 1972 [1932]). Such a conceptualisation of the self necessitates a contextually informed focus on the pragmatic interpretations of ordinary individuals going about their daily lives within the natural attitude. This is the only justifiable focus of a phenomenologically informed sociology that, in lieu of its being integral, also avoids a reactionary shift of the ontological balance toward the empirically unsatisfying position of transcendental subjectivity. For the remainder of this article there will be no further reference to subjectivity and objectivity in their capacity as sovereign ontological dimensions. Rather, the appearance of certain processes and structures encountered within the intersubjective ontological dimension as tending more towards either objectivity or subjectivity represent the focus of analysis. [15]

3.1 A phenomenologically informed approach to the study of social reality

Phenomenology's foundational proposition is that, in everyday life, consciousness is permanently directed at an object of some sort, be it a directly perceived physical object or an abstract phenomenon engaged through memory, fantasy or contemplation (OVERGAARD & ZAHAVI, 2009). This hypothesis proves to be a blow to the Cartesian divorce of consciousness from matter that underlies the crippling dualism of modern science. Contemporary science, being institutionally limited to analysis of the objective ontological dimension by means of the objective epistemological mode, has problematically attempted to overcome the difficulties raised by this inherent dualism by denying the existence of its own subject. Phenomenology makes it possible to reconceptualise the relationship between subject and object, thus refining the relationships between perception, meaning and action. Where social action or social structure invariably represent the focal points of the classical sociological paradigms, the insights of phenomenology pave the way for intersubjectively constructed meaning to emerge as the focus of a reinvigorated sociology geared toward the unassuming understanding of social reality. [16]

Fundamental to the phenomenology of society, also referred to as protosociology (DREHER, 2012), is the concept of the life-world, defined as that world to which all that is pre-scientific belongs. The life-world may be conceptualised as a holon, which in this case includes various worlds of dreams, fantasy and altered phenomenal fields4) as possible realms of experience. Enveloped by this more general life-world, conceived of as the entire universe of possible experience, is the world of everyday life, or paramount reality. This is the sphere of reality that is collectively accepted as paramount by human beings operating from within a natural and unscientific perspective (SCHÜTZ & LUCKMANN, 1974). A phenomenological analysis of this world of everyday life rejects the view of consciousness accepted by the scientistic reductionists, namely that it represents nothing more than an illusory epiphenomenon accidentally generated during the computation of sensory inputs. It also rejects many of the methods used by natural scientists during the analysis of a cosmos thusly defined (SOKOLOWSKI, 2008). Phenomenology's attempt to acknowledge reality as being at least partially constructed by experiencing subjects through their meaningful interaction with each other stands in contrast to positivism's quest for abstract objects and conditions removed from everyday experience. [17]

The historical trajectory of modern science has led to the counterintuitive argument that consciousness is a meaningless by-product of physical processes, not to be pragmatically trusted or scientifically acknowledged. It is however clear from everyday experience that consciousness is an indispensable part of reality. Indeed, the possibility of its presence ontologically preceding that of the physical universe becomes plausible to those who have taken the practice of phenomenological reduction to its transcendental stage or who have seriously engaged in transcendental meditation as practiced in certain schools of Eastern philosophy (BÖHME 2014; HUSSERL, 1960 [1931]). Attaining a deeper level of understanding of the dynamic relationship between subjective perceptions and objectivated socio-cultural structures that underlies the intersubjective construction of identity is given preference above attempts at universal description and the prediction of over-simplified variables. Such attempts are associated with methodologies situated exclusively within the objective epistemological mode and which inherently tend to deny the existence, or at least relevance, of any aspects of reality situated outside the objective ontological dimension. Phenomenologically informed sociology's focus on intersubjectivity also guards against an undesirable foray into metaphysics, which is a symptom of unreflexively venturing into the subjective ontological dimension, where all perception has the character of true and complete revelation. Whenever the interpretive sociologist speaks of meaning, he or she should be careful to point out that said meaning refers neither to the inherently unsharable contents of pure subjectivity, nor to any objectively self-existent thing-in-itself. Rather, meaning in the context of this study refers to an intersubjectively constructed phenomenon that is itself the result of socially related subjects attempting to make some kind of collective sense out of often incongruent subjectively experienced realities. We, as integrally informed sociologists, are still primarily interested in uncovering socially shared meaning-frameworks that are a defining constituent of reality-as-agreed-upon, or the intersubjective ontological dimension of reality. As Alfred SCHÜTZ (1962) clarified, the phenomenologically informed sociologist is concerned with a social reality which has been collectively pre-interpreted by the human beings whose meaning-frameworks represent the target of analysis. Interpretive sociologists thus create constructs of constructs, or constructs of the second degree, whenever social reality is meaningfully analysed. The presence of intersubjectively shared meaning differentiates the study of social reality from both that of the physical universe and that of subjective consciousness, which necessitates the development of novel methodological and theoretical frameworks. To this end SCHÜTZ (1970), applying HUSSERL's phenomenology to analyse the social world, conceptualised various pre-reflexive structures of consciousness underlying the social construction of reality. These structures are embedded in the temporal reality of the stream of consciousness and thus rest on the basic human postulates of "and so forth" and "I can do it again". The specific contents of these assumptions are informed by the dialectical interaction between an individual's stock of knowledge and his or her biographically determined situation. Both serve to orient subjectivity cognitively, affectively and temporally, thus representing the structures through which meaning is internalised and externalised and a relational sense of identity developed by the experiencing subject. These structures are widely accepted and as such were not taken as problematic during the study that is dealt with in Sections 4 and 5 of this article. The focus of inquiry in this case is the mechanism through which meaning is intersubjectively shared. [18]

The fundamental mechanism through which subjectivity is externalised, and eventually objectivated, is language (BERGER & LUCKMANN, 1967). It is through language that the products of the human mind most commonly come to be expressed as tangible elements of paramount reality. Language represents the primary mechanism by means of which social reality is constructed and maintained, and social life is first and foremost "... life with and by means of the language I share with my fellowmen" (p.51). It is primarily through adopting shared meaning-frameworks mediated by language that individual subjects coalesce into collectivities. In the context of this article collectivities denote intersubjectively constituted groups in which membership is largely dependent on the internalisation of certain socially shared interpretations of reality, along with a consequent externalisation of adequate behavioural patterns and attitudes. Upon closer inspection of the role of language in the construction of social reality, the process of storytelling emerges as a phenomenon of fundamental importance. In all documented societies storytelling serves as a method of sharing meaning, one that serves to construct a shared sense of history and reality through drawing in tellers and listeners and linking them through time and space. Dan McADAMS (1993) developed this insight into a novel theory of identity that conceptualises the individual self as playing the role of protagonist in a life-long story centred on the self and its experiences. According to him a sense of "story grammar" is universally developed early in the human lifespan. This universal orientation to a certain pattern of unfolding allows young children to distinguish between a story and any other verbal or textual passage based on their understanding of the constituent elements and chronology of a "plot". It is also a characteristic of stories that, apart from their contextual and situational fictionality, they conceptually and structurally mimic reality so closely that the experience of "losing oneself in a story" is readily available to subjective perception. Intriguingly, an individual's biographically determined situation grows "... plausibly out of what has come before and point[s] the way to what might reasonably come next" (BERGER & QUINNEY, 2005, p.4), in a process akin to the unfolding of a story. An analogy between a lived human life and a told story thus provides fertile ground for qualitatively exploring the social construction of reality through analysing the contents and circulation of the stories shared by socially related individuals, an idea that is explored in Section 3.2. [19]

In line with the arguments for holism as outlined earlier, it should be noted that an exclusively phenomenological analysis of stories, even when focusing on intersubjectively shared aspects thereof, is not sufficient for gaining an integral understanding of the intersubjective ontological dimension of identity. Apart from subjective experience, the objectivated nature of socio-cultural institutions and shared meaning-frameworks need to be given due attention as well, a course of action that is in line with the integral approach developed throughout this article. The ever-present dichotomy of subjectivity and objectivity encountered during the analysis of social reality thus needs to be taken into account at the methodological level as well. This can be done by making use of Pierre BOURDIEU's (1989) conceptual approach to what he called "total social science". His search for "structural constructivism" was rooted in the realisation that the structures of the life-world lead a "double life": They exist both as objects of the first order, independent of the interpretations of subjective consciousness, and as objects of the second order, as interpreted and symbolised by socially situated subjects (WACQUANT, 1992). [20]

This "double life" necessitates a "double reading", or the need to engage social phenomena from two complementary perspectives, which he called social phenomenology and social physics respectively (BOURDIEU, 1990). While social physics emphasises the quantitative analysis of macro-social structures, the phenomenological reading highlights a qualitative exploration of the meaningful experiences of the individuals who constitute said structures. Both of these approaches are insufficient when used in isolation and BOURDIEU attempted to avoid such methodological monism by emphasising the primacy of relations. One-sided analysis of either structure or agency is thus rejected in favour of a focus on the existing, readily observable relationships between subjectivity and objectivity, or in BOURDIEU's terminology that between the subjectively specific habitus and the objectively general field (JENKINS, 2002). Focusing on existing relations between so-called micro and macro-sociological factors facilitates an approach to sociological inquiry that emphasises the role of intersubjectively constructed meaning-frameworks above that of either subjective experience or objectivated social structures. Such a methodological approach is congruent with the argument we have developed throughout this article. [21]

Within the context of a narrative study, such methodological relationalism entails two interrelated endeavours. These are a hermeneutical interpretation of the stories of individual participants and a grounding thereof in the objectivated "meta-narratives" presented by social institutions, politics, religion and history. These meta-narratives represent the "objects" according to which individuals' stories are oriented and contextualised. Due attention must be paid to objectivated phenomena such as collective representations and intersubjectively shared interpretations of history and social reality, as well as the relationship between these meaning-frameworks and individual experience during the construction of identity (DURKHEIM, 1984 [1893]; MANDELBAUM, 1938). With all this in mind, it is possible to construct a methodological framework for investigating the aspects of identity that are intersubjectively constructed and maintained by the telling of stories. [22]

3.2 The role of storytelling in the construction of identity

Keeping the above mentioned factors in mind allows for a reflexive relationship between the analysis of individual stories and the identification of collectivities based on the presence of shared meaning-frameworks in the stories of various participants. A conceptualisation of identity as intersubjectively informed by the process of storytelling allows for the successful modification of identity into a concept of sociological analysis that can be studied in a qualitative manner. This can be done by comparing the contents, structure and circulation of stories encountered during fieldwork. This process is rendered meaningful by the widespread incidence of shared themes, acting as the vessels of intersubjectively shared interpretations of reality, found in the stories of socially related individuals. The presence, absence or mutation of certain character types, plots and genres, and their circulation within a society can serve to shed light on some of the intricacies of social affiliation and group formation. Every individual has access to a "narrative repertoire" (FRANK, 2012). The narrative repertoire consists of stories and story elements drawn from social sources, and it plays an important role in the development of axiological orientations and perceptions regarding belonging, the "other", and what exactly is desirable in social interaction and life in general. Thus, shared stories represent a foundational element in the construction of the intersubjective ontological dimension of identity. When envisioning storytelling as a central process in the constitution of identity, the following aspects can be seen as guiding the process:

The stories known to an individual, i.e. their content in terms of genre, plots and characters. This nexus is known as an individual's "narrative repertoire".

The sources of these stories, or where individuals hear or get their stories or the underlying elements from. These sources may include individuals, organisations or even texts (especially in the case of history and religion).

The resources available to an individual during the construction of his or her own story. Apart from the internalised stories mentioned above this includes momentarily variable aspects informed by the individual's stock of knowledge and biographically informed situation, which may range from factual knowledge to experienced emotion.

The audience to whom the individual tells his or her story. The active inclusion and exclusion of listeners gives us a glimpse into storytellers' perceptions of community and the "other", and the reactions of listeners serve to further mould the stories told by individuals.

The ways in which stories are used to justify certain actions or the desirability of certain traits, and how stories are used to convey values and norms within and between collectivities. [23]

By being aware of the above mentioned when listening to people's stories the tales are transformed from mere entertaining anecdotes to meaningful windows into the individual's daily experience of social reality. Stories bring to light powerful socially shared interpretations that influence a given individual's perception of social reality and the ways in which they interact with it. Thus, through tracing the distribution of shared stories or elements thereof, greater insight into the relationships between individuals and collectivities may emerge. This is the very way in which the conclusion was arrived at that contemporary White Afrikaans speakers form at least three broad collectivities, each related to and differentiated from the others by virtue of the contents, structure and circulation of the stories told by its members (KOTZE, 2013). This conclusion is discussed in Section 5. [24]

4. Methodological Considerations/Methods Used

The most important characteristics of the data collection and analysis phases of this study were an inductive logical approach, a contextualised qualitative investigation of the issue at hand and the implementation of a research process that was fundamentally emergent and open-ended in nature (CRESWELL, 2014). Considering our focus on the object of study's intersubjective ontological dimension, White Afrikaans-speaking identity was conceptualised as representing a hermeneutically interpretable "mystery" rather than an empirically solvable problem (ALVESSON & KÄRREMAN, 2011). The most important reason for this conceptualisation is the fact that the question of White Afrikaans-speaking identity can under no circumstance be made into an objectively resolvable problem. This is due to the simple reason that the constitution of the principal investigator's life-world created a research setting in which he was "... caught within the situation with no possibility of escape, and no possibility of clear-cut solutions" (GALLAGHER, 1992, p.152). Thus the relationship between the researcher and the object of study is one of mutual interpenetration. The researcher's own subjective experience of White Afrikaans-speaking identity, along with its intersubjectively constructed manifestations and the objectivated social structures that mediate and in turn are affected by these manifestations, all intertwine to the extent that complete detachment from the phenomenon to the point of becoming an "objective" observer is impossible. [25]

The ontological framework introduced in Section 2 allows us to acknowledge that, before the well-worn pathways of dualistic thinking guide consciousness into distinguishing between "self" and "not-self", such an interpenetration of observer and observed is the natural way in which reality manifests itself to consciousness. It is in the light of this realisation that the methodological approach applied during this study of White Afrikaans-speaking identity took on the form of what may be called a mixed-methods approach (CRESWELL, 2014). The fact that the study was grounded in an ontological framework that emphasises the irreducible nature of reality necessitated the avoidance of relying on a single methodology. The divergent evolution of sociology's various theoretical and methodological schools over the last century has led to the existence of a vast range of methods to choose from when it comes to investigating social reality. However, as these methodologies are nearly always rooted in the ideologies and assumptions of a given sociological paradigm they tend to obscure the bigger picture by unconsciously fracturing the holon of reality. In this way ungrounded phenomenological methods run the risk of confusing delusion with revelation while overemphasising the subjective ontological dimension. Most empirical methods in their turn exalt the objective ontological dimension over the layers of subjectively constituted and socially constructed meaning that have an equally large impact on the eventual nature of paramount reality. One-dimensional abstractions of this kind underlie many of our most heated debates, often leading to the illusory appearance of outright contradiction and in effect rendering them irresolvable. As mentioned earlier, the simplest way to guarantee the epistemological integrity of an integral approach aimed at overcoming this impasse is to include methods representational of each epistemological mode (subjective witnessing, intersubjective understanding and objective describing) in the process of data collection and analysis. Interestingly, when we focus on the intersubjective ontological dimension of a given phenomenon its subjective and objective ontological dimensions are rendered temporarily opaque. In other words, as we "zoom in" on the socially constructed aspects of identity, as opposed both to its subjectively constituted and empirically measurable aspects, the subjective and objective ontological dimensions are abstracted to a degree. Strictly speaking a given social reality, and the intersubjective ontological dimension of reality, in general, is not constituted of objectively given facts. Neither is it grounded primarily in subjective experience. The intersubjective dimension of reality gains its unique ontological status from the fact that its nature rests on consent and compromise in an interconnected, multidirectional network of "subjects" and "objects". Subjective experience loses its ontological centrality in the intersubjective ontological dimension, as is clear in the fact that social reality is not experienced as a shared dream-world consisting of incompatible individual fantasies. On the other hand, objectivated social structures never acquire the "solidity" of truly objectively given phenomena, instead tending to exhibit an asymptotical relationship to true objectivity. Simply put, the objectivated structures and institutions encountered in any society, whilst infinitely tending toward objectivity through the processes of internalisation and externalisation, never quite "get there". [26]

The singular power of the intersubjective ontological dimension lies in its ability, through the process of internalisation, externalisation and objectivation (BERGER & LUCKMANN, 1967), to trump both subjective intuition and objective description of the universe with an intersubjectively negotiated "consensus reality". This opacity of subjective and objective factors when focusing on the intersubjective ontological dimension need not however be a reason for concern. What is seen to be appearance by the sociologist is naïvely accepted as reality by the human beings who construct and maintain a given life-world (SCHÜTZ & LUCKMANN, 1974), creating a clearly demarcated ontological discontinuity that actually facilitates the investigation of that life-world. What are actually socially sanctioned interpretations of reality often masquerade as both subjective convictions and objective facts to the individual perceiving the world from within the natural attitude. This ontological discontinuity is encountered whenever a given social reality (or world-as-agreed-upon) is phenomenologically entered and made the object of scientific study (and converted into a world-as-described), and is readily navigable as long as the researcher remains aware of the encountered meaning-frameworks as being essentially arbitrary. The navigation of this ontological discontinuity represents one of the main challenges to gaining understanding of the experiences of others, and is explored in Section 4.2. Before we discuss the processes of data collection and analysis however, let us briefly turn to the preceding process of sampling and the ethical considerations applied during the course of this study of White Afrikaans-speaking identity. [27]

4.1 Sampling and ethical considerations

At the start of the study certain prerequisites were set in order to avoid undue complexities in the data analysis process and scale the study so as to conform to the parameters set for a postgraduate study of this kind. The first was that only White Afrikaans speakers were to be included in the study, as the inclusion of Afrikaans speakers of colour would have added an additional facet to the study, necessitating a longer timescale in order to complete a broader literature review. Issues around gender and sexual orientation merited similar considerations. A reflexive investigation of the experiences of White Afrikaans-speaking women in particular would have required the consideration of an imposing body of gender-specific literature, and working with people who identify as part of the LGBT (Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender) community would have called for an in-depth consideration of queer theory literature. It was simply not conceivable to responsibly conduct such an expanded study within the given time constraints. Though future investigation may consider the experiences of these members of South African society more expressly, this study focuses on adult White Afrikaans-speaking men of various ages, vocations and socio-economic backgrounds. [28]

A process of non-probability sampling was used to draw a workable sample from the target population. Thus participants were chosen on the merit of their compatibility to the project due to constraints on sample size and the duration of the study. Specifically, a purposive sampling strategy was used (BABBIE & MOUTON, 2010). This was appropriate for the study given our prior knowledge of the target population, gained through ethnographic observation. A heterogeneous group of six participants was eventually decided upon. Their ages ranged from the late teens to early fifties and among their ranks were included students, blue-collar workers and academics. The sample was drawn from Kimberley and Bloemfontein, the largest cities in central South Africa, and also Orania, a self-sufficient Afrikaner settlement situated close to both. This particular sample offered an opportunity to collect rich qualitative data through access to stories with a large amount of variance regarding their contents and circulation. [29]

Participants were briefed regarding the potentially sensitive nature of the study before any data was collected. An informed consent form was signed after the participant was made aware of the process to follow, after the signing of which participants were still allowed to withdraw their data from the study. Care was taken to protect participants from legal, physical and psychological harm, while confidentiality of all collected information and the resulting data was assured. No deception was used and the nature and scope of the study was explained to each participant before data was collected. [30]

4.2 Data collection and analysis

In order to comply with the theoretical prerequisites stated earlier, the data collection and analysis processes comprised three interrelated endeavours. The first was a historicist collection of social "facts" in the guise of a review of White Afrikaans-speaking history. This process represented an application of the objective epistemological mode, as an empirically given object, namely institutionalised Afrikaner history, was described in lieu of an empirical investigation. Here it is important to keep in mind the ontological discontinuity discussed earlier. This account of history was treated as objective due to the fact that it is experienced as objective by those whose life-worlds were under investigation. In this vein various historical sources were analysed, resulting in the excavation5) of a meta-narrative that could serve as a contextualising backdrop to the stories of individual participants. This meta-narrative is briefly discussed in Section 5. [31]

The second process, representing an application of the intersubjective epistemological mode, was a hermeneutic engagement with the stories of individual participants. This process involved hermeneutically spiralling between the stories of participants, the contextualising meta-narrative, and the primary researcher's interpretation of the nexus of meaning confronting him. Unlike the excavation of the meta-narrative, which involved the collection and cataloguing of "facts", this procedure had intersubjective understanding as its aim. The procedure closely followed the tenets of the theoretical approach outlined in Section 3.1., and focused on the presence of socially shared meaning-frameworks in the stories of individual participants. These stories were collected by means of modified in-depth individual and group interviews. These "involved conversations", as the authors prefer to call them, were based on an amalgamation of the phenomenological interview (ENGLANDER, 2012; GROENEWALD, 2004) and the "Socratic-hermeneutic inter-view" (ROULSTON, 2012). The former technique encourages the generation of rich descriptions of experienced reality in the participant's own words, while the latter nurtures the development of a relationship of co-inquiry between the researcher and researched. This resulted in an interview method that was characterised by a semi-structured open-endedness, allowing the participant to enjoy a high degree of expressive freedom that guarded against entrapping him or her in meaning-frameworks and terminology brought into the session by the researcher. [32]

In keeping with the intended naturalistic nature of the interviews, they were also characterised by a mild degree of confrontation, a natural characteristic of many everyday conversations. The primary investigator was aware of the fact that "... caring interviews [often] neglect real power relations" (BRINKMANN & KVALE, 2005, p.170). Utilising a sensible degree of stimulating confrontation, through reflexively challenging the participants' accounts of reality, facilitated the uncovering of data that would not be generated had the researcher simply feigned understanding (BRINKMANN, 2012; KVALE, 2007). The interview sessions were conducted in Afrikaans in order to comply with the necessary sensitivity toward language as the primary vessel of intersubjectively shared meaning-frameworks. Collecting data in the participants' first language and sharing a native proficiency therein with them ensured sensitivity toward the nuances of shared metaphors and subtleties that are often overlooked by second-language speakers. This, along with the supportive use of group conversations (that were conceptualised similarly to the individual interviews), also allowed for a focus on patterning, conversational power dynamics and intersubjective learning. These are all factors that delineate the sociological nature of the study from the psychological tinge brought about by a focus on individual memory and other more intrasubjective aspects (TONKIN, 1992). [33]

The third process, which took the study into the data analysis phase, was a thematic analysis and phenomenological consideration of the collected data by the principal investigator. Building on aspects of Arthur FRANK's "dialogical narrative analysis" (2012), the stories shared by the participants were grouped according to the incidence of shared and overlapping themes and narrative repertoires and their relationship to the meta-narrative provided by the previously excavated historical overview. This process represented the application of the primary author's own subjective epistemological mode and was meant to reflect the way in which he "witnessed" the data yielded during the course of the study. The result is the typology presented in Figure 4. Participants' stories were thematically analysed in order to discover intersubjectively shared orientations toward especially the themes of race, religion and nationalism. These themes were selected due to their pervasive presence in the stories told by the participants, along with their centrality in the meta-narrative of White Afrikaans-speaking history. The resulting typology represents conclusions that the first author regarded as contextually plausible and confirmable, and which were agreed to be contextually valid by the co-authors upon contemplation of the presented data. The conclusions arrived at thus resulted from the integral application of various existing theoretical schools of thought and methodological practices, guided by a holistic ontological and epistemological framework. The reflexive integration of these approaches produced data that are sensitive to all three of the epistemological modes illustrated in Figure 2 and are presented to the sociological community in the form of an interpretive account intended to stimulate intellectual debate around the practices employed during the study, as well as its results. [34]

5. The Case of White Afrikaans-Speaking Identity

As discussed in Section 4.2, the study consisted of engaging White Afrikaans-speaking men of various ages, backgrounds, socioeconomic positions and ideological orientations in multiple in-depth interviews. As a preliminary undertaking before entering the field however, a review of White Afrikaans-speaking history was launched. This review served to contextualise the historical development of White Afrikaans-speaking identity. It also drew the primary investigator's attention to certain themes that seemed to underlie past expressions of White Afrikaans-speaking identity, and that still play an important role during the constitution of identity among White Afrikaans speakers. As elaborated in Section 4, a reflexive historicism allows for the inclusion of an "objective" measure with which to contextualise intersubjectively constructed stories of identity, as certain versions of history tend to be unproblematically experienced as "objective" by members of given collectivities. Through focusing on the emergence and development of collective representations as embedded in various historical sources, we could excavate a meta-narrative of the historical development of White Afrikaans-speaking identity in its collective manifestation. Figure 3 illustrates the resulting reconstruction of the evolution of the collective identity of European settlers at the Cape of Good Hope through three distinct stages, the Burghers of the 17th century, the Boers of the 1800's and the development into the Afrikaner collectivity of the mid-20th century (see Figure 3). [35]

This meta-narrative was necessary to support the phenomenological inquiry into lived experience with an empirically observable correlate representing the objective epistemological mode, as discussed in Section 4.2. This was done in order to facilitate the integral analysis advocated throughout the course of this article. This multi-dimensional approach allowed for the emphasis of inquiry to be directed at the relationships between the everyday experiences of White Afrikaans speakers and the institutionalised meta-narrative presented by their documented history as a collectivity. But before we turn to the collected stories, let us take a very simplified look at mainstream White Afrikaans-speaking history, as it serves as the backdrop according to which many White Afrikaans speakers construct their stories of identity.

Figure 3: The evolution of White Afrikaans-speaking identity: 1652-1994 (KOTZE, 2013, p.63) [36]

As can be seen in Figure 3, the well documented history of White Afrikaans-speaking identity comes to an abrupt end around 1994, when the Afrikaners' collective representations crumbled with the loss of political dominance. Little formal research has been done on White Afrikaans-speaking identity since then (DAVIES, 2009) even though the possibilities regarding the construction of individual and collective identities seem to have led various groups of White Afrikaans speakers down diverging, often antagonistic paths. When ethnographically observed it becomes clear that there no longer exists one coherent White Afrikaans-speaking collectivity. Rather, various collectivities have emerged to fill the vacuum left by the sudden disappearance of a highly institutionalised and formalised collective identity (KOTZE, 2013). The ensuing comparison between collected personal stories and the historical meta-narrative reconstructed at the beginning of the study yielded three main themes that seem to be present wherever White Afrikaans-speaking identity is discussed. These themes are race, religion and nationalism. Contemporary White Afrikaans speakers exhibit a wide range of orientations toward these themes. By phenomenologically gauging the various orientations toward these themes it becomes clear that three broad White Afrikaans-speaking collectivities exist in contemporary South Africa. These are primarily distinguished from each other according to the contents and circulation of their collective representations, which stand in dialectical relation to the narrative repertoires of their members (ibid.). Figure 4 offers the primary author's interpretation of the nexus of White Afrikaans-speaking identity in contemporary South Africa, thus finally acknowledging the subjective epistemological mode and completing an integral sociological analysis of the phenomenon. Intricate socially shared interpretations of the themes of race, religion and nationalism are significantly simplified in terms of the widely understood concepts of individualism, religious fundamentalism/conservatism and political liberalism. These everyday concepts serve to illustrate the relationship between these collectivities without hindering understanding of the data by individuals operating from within the natural attitude.

Figure 4: A typology of 21st century White Afrikaans-speaking identity (KOTZE, 2013, p.101) [37]

Before going into a detailed description of the data, it is necessary to briefly elucidate the terms used to refer to the various White Afrikaans-speaking collectivities in Figure 4 and the following sections. During the height of apartheid and up to 1994, an Afrikaner was rather rigidly defined as "... white, an Afrikaans speaker of West European descent who votes for the NP [National Party], belongs to one of the three Dutch Reformed Churches and shares a distinctive history with the rest of the Afrikaner group" (LOUW-POTGIETER, 1988, p.50). This definition still carries weight when referring to Afrikaners today and most people who self-identify as Afrikaners would accept such a definition. In this article, the term Afrikaner is thus applied to those white Afrikaans speakers who consciously choose to develop a collective identity along the evolutionary trajectory inherited from the Afrikaners of the 20th century. Apart from contemporary Afrikaners, who actively practice traditional Afrikaner culture and have changed little in terms of the content of their shared narrative repertoires, at least two significant alternative branches of white Afrikaans-speakers have emerged since the fall of apartheid. [38]

The first, calling themselves Boers, have sought to reject much of the cultural evolution of the 20th century and seek to maintain a life-world built around fundamentalist interpretations of religious scriptures and often ahistorical tribalist interpretations of history. Because of the fact that the historical Boers naturally evolved into the Afrikaner collectivity, and many Afrikaners in fact still lead rural lives that are not much different from those of the 19th century Boers, we refer to this extremist subgrouping as Pseudo-Boers. Many Pseudo-Boers do not in fact lead lives resembling those of their historical predecessors but have turned to embittered and hateful worldviews due to a variety of social, political and psychological factors, which are explored in Section 4.2. The second collectivity that has developed parallel to the Afrikaner grouping is that group of White Afrikaans speakers referred to as Afrikaanses throughout this article. The term Afrikaanse was first used by Arrie ROUSSOUW, former editor of Die Burger (a widely circulated Afrikaans newspaper), as a more inclusive term for Afrikaans speakers that has no racially exclusive connotations (DAVIES, 2009). It is also used in that sense in this article, and refers to White (and people of other ethnicities) Afrikaans speakers who for various reasons have rejected the more constricting monikers of Afrikaner and Boer. [39]

The previous section introduced the three main White Afrikaans-speaking collectivities whose contemporary existence become apparent when individual participants' stories are analysed and categorised according to their content, structure, circulation and relative relationship to the meta-narrative of White Afrikaans-speaking history. Of these three, the Afrikaanses represent the most thoroughly postmodern group of contemporary White Afrikaans speakers. The majority of this collectivity's members share an Afrikaner heritage, but membership is not formally limited to those of European descent. The primary requirement for inclusion into the Afrikaanse collectivity is the presence of Afrikaans as first language and, in the case of White members, an active rejection of the more restrictive labels of "Boer" and "Afrikaner", the other two groups in our typology. The Afrikaanses in effect represent a kind of anti-category which primarily rests on the rejection of membership within both of the other groups, and to that extent this group does not represent a collectivity in the traditional sense of the term. Membership within this group is not dependent on any shared sense of identity or patterns of behaviour, and is quite flexible in practice. Some Afrikaanse viewpoints regarding the question of "Afrikaner" identity include the following (all participants used self-assigned pseudonyms):

"The only Afrikaner in Africa is a breed of cattle. I don't think we live in a time where that line of thinking is relevant. It's relevant to people who force themselves to be Afrikaners according to certain criteria of what an Afrikaner is supposed to be. To me the term Afrikaner has lost its value, because today we live in a world where we have so many other worlds available to us" (Atropos).

"I feel myself to be a South African, it feels as if the lines are getting blurred. There aren't pure Afrikaners anymore, and I'm fine with that. Personally I feel that creates a problem. We already have enough problems, to throw race into the mix as well is to create a concoction that's ready to explode. That's what I believe, and I want to stay in this country ..." (Joe Black). [40]

Afrikaanses generally accept the secular scientific and economic values of the globalising world, and as such are basically world citizens who happen to speak Afrikaans. As soon as the language is lost, membership is terminated. There is no self-identification present among members and Afrikaanses tend toward the development of highly individualistic identities and the avoidance of collective associations, especially those defined in terms of religion, politics and culture. These themes are of more importance to more conservatively inclined White Afrikaans speakers. The Afrikaanses who were encountered during the course of this study also had access to a wider narrative repertoire than their Afrikaner and Pseudo-Boer counterparts. The sources of their stories, and possibilities for the construction of identity, are limited only by the individual's personal interests and tend to be dominated by the contents of the subjective stock of knowledge and biographically determined situation. Likewise, the circulation of Afrikaanse stories has no formal limitations, even though certain levels of disclosure tend to be reserved for individuals of similar persuasion. There are no prescribed parameters as to an Afrikaanse's social affiliations, allowing members of this group to be exposed to stories that seldom reach the awareness of members of the more insular collectivities. Their stories also reach a more diverse audience, which basically refers to the people with whom they engage in social interaction and, in doing so, exchange stories. The most important difference between the narrative repertoire of Afrikaanses and those of the Afrikaners and Pseudo-Boers is its open-endedness. This flexibility supports a degree of personal freedom during the construction of identity that is not readily available to members of more formal, "objectively" oriented collectivities: "It's too easy to go with the flow, I tend to avoid that kind of thing" (Atropos). [41]

This characteristic open-endedness can be seen clearly in the attitude of Afrikaanses toward the three themes identified during the review of White Afrikaans-speaking history, namely race, religion and nationalism. Afrikaanses' perceptions of race vary dramatically between individual cases for instance, with some assuming orientations more reminiscent of that of one of the other collectivities. The following quote, firstly expressing an awareness of colonialism as the root cause of much of the suffering of South Africa's poor and then reprimanding the same people for not being industrious enough, reveals an almost schizophrenic relationship toward issues of race in a young man who has largely cast off Afrikaner tradition and operates within a multicultural social environment, but remains situated within a larger socio-cultural milieu where issues of race are always pertinent:

"The white man doesn't own anything in Africa, we don't own anything in Africa. It's like a guest that comes into your house and then drinks all your coffee, or uses all your sugar, and then sleeps in your bed. But they [black people] shouldn't turn their backs on the people who gave them all the opportunities. When I talk to guys from Ghana and Cameroon, it all boils down to one thing; our blacks are lazy, they just take, they get everything and they don't give anything back. Then they moan about it" (Atropos). [42]

This phenomenon provides support for the argument that the typology presented earlier should not be seen as a rigidly exclusive system of categorisation. Rather, it should be seen as highlighting nodes of individual concentration along a continuum of possibilities regarding the internalisation of intersubjectively informed meaning-frameworks, especially regarding the issues of race, religion and nationalism. Even though certain attitudes expressed by Afrikaanses converge with those of members of the other collectivities, the difference is that the interpretation tends to be derived from personal conclusions in the case of Afrikaanses, rather than social expectations as in the case of the Afrikaners and Pseudo-Boers. Regarding religion, a similar tendency toward individuality can be seen. While membership within the Afrikaanse collectivity and the practice of organised religion do not exclude each other, Afrikaanses generally tend toward highly personal expressions of spirituality. Spirituality is seen as a personal matter, and the socio-cultural concerns that often underlie religious expression among members of the other groups, are of less consequence to Afrikaanses. [43]

A subtle worldview, in which hypocrisy is found more abhorrent than social dissent, is often found among Afrikaanses. This state of affairs indicates an example where subjective interpretation trumps the more "objective" pressure of the social context when it comes to the construction of identity. Concerning nationalism, this tendency toward individualism often leads to members of the Afrikaanse collectivity rejecting any notion of an ideologically unified "volk". As illustrated in Figure 4, the Afrikaanses represent the most individualistically oriented segment of contemporary White Afrikaans speakers. There is little visible connection to collective loyalties or group identities, especially of a national, political or cultural nature. Rather, social relationships are rooted in personal convictions and choices, and externalised behaviour is variable and highly individualistic in nature. [44]

The Pseudo-Boers represent a subgroup of contemporary White Afrikaans speakers that is characterised primarily by its members' self-identification as Boere, instead of Afrikaners. We do not refer to this group as Boers, simply because their narrative repertoires bear very little resemblance to those of the historical Boer collectivity. As illustrated in Figure 3, the Boers are conceptualised as representing an evolutionary predecessor of the historical Afrikaners, one whose collective representations largely fell away by the end of the 19th century. The narrative repertoire of the average Pseudo-Boer tends to be limited, in extreme cases to a few fundamentalist publications based on the Old Testament and the prophecies of Niklaas VAN RENSBURG, a 19th century seer. This group appears to be growing though, recruiting primarily from the working classes, but also from a growing group of youth with tertiary qualifications. This tendency most likely represents a reaction to the present political and economic climate. In fact, an underlying current of perceived victimisation is present in many of the stories told by members of this collectivity:

"My parents separated and I started to investigate religion and history for myself. In this way you meet people, you come across people who give you certain historical sources and so forth. You start forming your religion according to your viewpoint. Basically, I flopped at the College, I didn't make it, because their course fell away, or whatever. So that was their problem over there. Now I'm just sitting at home, trying to find a job, because my religious setup isn't compatible with today's government and political system, so ..." (Jisraeliet). [45]

Their narrative repertoires tend to be the most linear and oppressive of the three collectivities. Science and transformation are largely rejected, and any change is regarded with suspicion:

"In liberal thinking, or Greek thinking, everything changes. Democracy, evolution, nothing stays the same. In Hebrew thinking, everything works in cycles. Bananas produce bananas, monkeys produce monkeys. I follow the word of Father, and steadily become better at it. We have no need of high doctors, or Pharisees" (Judeër). [46]

The most extreme Pseudo-Boer worldview acknowledges only three human character types. These include 1. those who have been preselected to rule over the earth, the so-called "Adamites", 2. the "snake seed", who were created by Satan and are destined for irreconcilable damnation, and 3. the "traitors", those Adamites who betray Yahweh/God and the Boervolk/Israel through their uncouth liberalism. Identity possibilities are thus rigidly outlined from the get-go and depend on a given individual's biological race, which serves as a master status when deductions regarding issues of religion and nationalism are made. It is impossible to modify this state of affairs without forsaking membership within the group. Of the three groups, the issues of race, religion and nationalism are most closely intertwined in the case of the Pseudo-Boers. They form a meaning-framework that is representative of the most extreme racist orientations found among White Afrikaans speakers today. There is a widespread understanding that the "Boervolk" are a chosen people, with some radical groups claiming the nations of Western Europe to be the direct descendants of Biblical Israel. It is noteworthy that this belief is shared by similar groups in Europe and America, like the British Israelism movement and the various Christian Identity denominations in the U.S. (BARKUN 1997; WILSON 1968):

"The Israelites were banished from Jerusalem and the city was left empty of inhabitants. We believe that during this time the Edomites, descendants of Esau, who mixed with the descendants of Cain in Mongolia, the Kazaks, moved into Jerusalem while the true Israelites were in banishment. They bought priests from Israel, who taught these mongrel people the religion that is known as Judaism today" (Judeër). [47]

During the process of data collection the researcher was distrusted as being a wetsgeleerde (someone who is learned in the ways of the world) rather than a skrifgeleerde (one who studies the scriptures). To the Pseudo-Boers the researcher was a Pharisee, a potential serpent. However, the apparent similarity with mainstream Christianity stops here. As soon as this group of participants was made to acknowledge the existence of countless Christians of colour, they retorted that Christianity itself was a tool designed by the Jews to sow division among the true tribes of Israel. To them Christianity is a front, and faith is not determined by choice, but by blood: "All Adamites can become Israelites. No one of any other race, be it Chinese or whatever, can become an Israelite, only a white Adamite" (Jisraeliet). [48]