Volume 16, No. 3, Art. 11 – September 2015

Analyzing the Qualitative Data Analyst: A Naturalistic Investigation of Data Interpretation

Wolff-Michael Roth

Abstract: Much qualitative research involves the analysis of verbal data. Although the possibility to conduct qualitative research in a rigorous manner is sometimes contested in debates of qualitative/quantitative methods, there are scholarly communities within which qualitative research is indeed data driven and enacted in rigorous ways. How might one teach rigorous approaches to analysis of verbal data? In this study, 20 sessions were recorded in introductory graduate classes on qualitative research methods. The social scientist thought aloud while analyzing transcriptions that were handed to her immediately prior the sessions and for which she had no background information. The students then assessed, sometimes showing the original video, the degree to which the analyst had recovered (the structures of) the original events. This study provides answers to the broad question: "How does an analyst recover an original event with a high degree of accuracy?" Implications are discussed for teaching qualitative data analysis.

Key words: expertise; analyzing aloud; conversation analysis; relational analysis

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. Background

3. Method

3.1 Participant

3.2 Context

3.3 Task

3.4 Data

3.5 Data analysis

4. Reconstructing an Event From a Transcription: The Documentary Method at Work

5. Objective Features

6. The Viewpoints of Actors and Witnesses

6.1 The actors' point of view

6.2 Formulating

6.3 Relational analysis

7. Hypothesis Generation and Testing

8. Discussion

9. Implications for Teaching Qualitative Data Analysis

10. Reflexive Coda

Appendix: Sample Transcription

Analysts rarely analyze their own activity (ANTAKI, BIAZZI, NISSEN & WAGNER, 2008). How do they ascertain the quality of their analyses? In this contribution to the FQS Debate on Teaching and Learning Qualitative Methods, I provide an answer to the question: How does an experienced researcher go about her task of analyzing data when she knows that someone else knows the story that produced the data and can therefore judge the extent to which the analysis matches the real events? [1]

Data analysis is an integral and defining aspect of science. Although methods sections in research articles are intended to exhibit what the authors have done to arrive at the findings reported, these descriptions often are insufficient, even in the hard sciences, to allow investigations to be reproduced in other contexts (COLLINS, 2001; JORDAN & LYNCH, 1998). Although there are some who denounce methods courses favoring instead practical teaching methods at the elbow of experienced researchers (BOURDIEU, 1992), research methods courses continue to constitute a mainstay in graduate-level university courses. The quality of data analysis is an important issue in textbooks of research methods (e.g., BERG, 2004), but in much of ("constructivist") social science research "the idea of isomorphism between findings and an objective reality is replaced by isomorphism between constructed realities of respondents and the reconstructions attributed to them" (GUBA & LINCOLN, 1989, p.237). This is often taken as a license to analytic freedom, because in the social sciences, more so than the natural sciences, research results are the outcome of "social construction" under the best conditions and as "'mere' story-telling" (ANDERSON & SHARROCK, 1984, p.104) in other instances more critical to qualitative approaches in social science (GROSS & LEVITT, 1994). [2]

The task of data analysis in the social sciences can be viewed differently, that is, in analogy to police / detective work or inquiries in courts of law. Just as the police officers and judges cannot just construct something and inculpate a person, which would mean many innocent individuals might end up in prison or on death row, we might hold social science researchers accountable and require that they "get their story right," to the extent that this is possible. The purpose of this study is to provide an answer to the question posed in the opening paragraph. To model rigor in data analysis, the instructor of an introductory graduate-level course in qualitative research for the social sciences invited her students to transcribe video clips with contents of their interest. The transcriptions were to contain as few clues as possible about the original source. The instructor told students she would analyze the data aloud in real time, without any background information, in the attempt to reconstruct the situation that produced the verbal protocol. But she did not say that she was using any specific method of interpretation. In the subsequent class discussion, the owner of the data would then judge the degree to which the instructor had achieved the self-imposed task, often presenting the original video. In all 20 sessions videotaped (n = 11) or observed (n = 9), the instructor had not just constructed something but indeed arrived at identifying the type of social situation (school class, talk show, interview, broadcast, outdoor science center), nature and relation of participants (e.g., interviewers, teachers, students, journalists, staff). The protocol includes evidence for the analytic work conducted and formulations of this work for the purpose of teaching analytic methods. [3]

Data analysis is the bread and butter of research in all sciences. Learning how to analyze verbal data is an integral aspect of graduate training in the social sciences. The mode by means of which graduate students learn about and acquire data analysis practices differs. Having taught and supervised graduate students in different parts of the world, I know first-hand that in North American universities methods courses tend to be integral to the required program of studies, graduate training in other parts of the world often does not include course work so that the students learn research methods while doing research. Readers of methods textbooks or of special journal issues devoted to research methods—tend to read, at best, about data analysis. Readers of empirical articles are provided with a posteriori descriptions of what researchers have done. In both instances, they are in the same predicament as natural scientists, who may not be able to reproduce the analysis from the descriptions of method (e.g., COLLINS, 2001; JORDAN & LYNCH, 1998). In these and similar studies, the natural scientists come to reproduce the work of other laboratories only when actually doing analysis with the members of these laboratories. When graduate students work at the elbow of experienced researchers, they tend to learn data analysis in a tacit mode (e.g., BOURDIEU, 1992); in textbooks and journal articles on method or by reading empirical research, students tend to read about methods and may gain some experience by analyzing data in class or as part of assignments. They do not tend to get first-hand experience of how an expert analyses data. In this study, I investigate how an experienced researcher analyzes data aloud for the purpose of making the analytic process visible and, thereby, instructing graduate students. This type of instruction is known as the first step in cognitive apprenticeship, where experts model their practices by exhibiting learners to their expertise (COLLINS, BROWN & NEWMAN, 1989; VAN SOMEREN, BARNARD & SANDBERG, 1994). Because the graduate students had provided the transcriptions, and because analyzing aloud was part of the teaching strategy, this is a naturalistic study of expertise in data analysis including naturalistically produced (rather than researcher-designed) protocols. What are the features of expertise in verbal data analysis and which aspects of expertise are formulated for the audience? [4]

How experts reason while interpreting data, texts, or diagrams tends to be investigated using the protocols generated while experts do aloud what they normally do without externalizing their thoughts. Thus, for example, there are investigations on how scientists analyze graphs (e.g., TABACHNECK-SCHIJF, LEONARDO & SIMON, 1997), medical experts read electrocardiograms (GILHOOLY et al., 1997), pilots analyze the videotaped performances of peers (ROTH & MAVIN, 2015), how translators treat linguistic aspects during the translation of texts between two languages (KUNZLI, 2009), or expert historians interpret historical texts (WINEBURG, 1998). However, (interpretive) social science research that (reflexively) investigates (interpretive) social scientists at work is much more rare; and, to my knowledge, there has been no study of this kind. These expertise studies focusing on interpretation tend to highlight the considerable role that content area knowledge plays in the interpretation of graphical and textual information. When such background knowledge is unavailable or not easily accessible, such as when experts are unfamiliar with graphs even when these are from introductory university courses of their own domain, then the performance levels drop considerably (e.g., ROTH & BOWEN, 2003). In such instances, a lot of the work is spent on identifying those aspects of the visual or verbal text that actually serve as a sign that expresses something about the situation of interest. But whether visual or textual feature actually is a useful sign depends on the structures of the possible referent situation. Thus, for example, whether the actual values or the slope of a curve is to be read is a function of the hypothesized phenomenon that has possibly given rise to the graph. However, even when given a specific phenomenon as the referent of a population graph, experienced scientists may focus on the wrong graphical feature in their explanations. [5]

What is the kind of knowledge brought to work by a social scientist whose work is concerned with constructing knowledge about the (functioning of the) social world? [6]

A classic study of researchers at work investigated how sociology graduate students coded the information in nearly 1,600 folders of an outpatient clinic (GARFINKEL, 1967). The purpose of the research was to find out, from an analysis of the folders, the trajectories of patients through the institution ("careers") given the characteristics of these patients, the clinical personnel, their interactions, and a given decision-making tree. The analysis shows that rather than abstractly matching folder contents with coding criteria, the coders were using and indeed "assuming knowledge of the very organized ways of the clinic that their coding procedures were intended to produce descriptions of" (p.20). That is, these coders used the actual folder contents as forms of documentary evidence of the ways in which a clinic works, and familiarity with the clinic practices was an integral aspect to ascertaining the sense of the folder contents. Moreover, the relationship—between familiarity with clinic practices and the records to be coded—was used to find the sense of the coding instructions. [7]

GARFINKEL provides descriptions of several other contexts to suggest that the documentary method of interpretation is a pervasive method in lay as in professional sociology generally and in fact finding more specifically. In one experiment, undergraduate students "interacted" with a counselor to obtain advice about personal problems. They could only ask questions that were to be answered by a yes/no reply. Although the "counselor" produced the yes/no replies at random, the students nevertheless took each as the document of a motivated, coherent and honest response even when there were contradictions were evident. [8]

In the two previous examples, the lay/professional analysts were confronted with forms of evidence (records, yes/no responses) and their task was to determine the system or thought that produced the pieces of evidence. That is, these analysts treated the pieces of evidence as accounts of something that has happened, and the analysts had to find out what happened. GARFINKEL also describes another type of situation, in which some final outcome is given and a search has to be conducted for pieces of evidence that provide a reasonable account of how this state was brought about. A coroner tends to be confronted with a dead person and then has to identify the mode of death. The coroner will collect materials that can be collected or photographed or recorded in some other fashion, including (written, taped) recordings of verbal statements. Here, again, the method works reflexively, selecting among materials those that are consistent with a particular mode of death, and taking the body to be expressing a mode of death consistent with the material evidence of a particular sequence of events. [9]

In ethnomethodology, a particular form of reflexivity is recognized (LYNCH, 2000). The very methods by means of which ordinary people (ethno-) make the social world appear in a structured way are prerequisites for studying the social world. This is so not only for ethnomethodologists who make this work their object of investigation (this ethnomethodology) but especially for all those researchers using formal (qualitative or quantitative) methods to study social/psychological phenomena (GARFINKEL, 1996). That is, other than the stance that inductively oriented studies tend to take, investigations of social-psychological phenomena presuppose the very competencies and practices at the heart of the study. As a result, the social scientist "is literally beleaguered by [the preconstructed], as everybody else is" (BOURDIEU, 1992, p.235). The social scientist therefore is

"saddled with the task of knowing an object—the social world—of which he is the product, in a way such that the problems that he raises about it and the concepts he uses have every chance of being the product of this object itself" (ibid.). [10]

BOURDIEU is concerned with the identification of objective structures of the social world and recommends the investigation of the methods of construction. Although the sociologist is critical of ethnomethodology, it appears that the practitioners of this field are pursuing precisely the type of studies required by doing a methodology, focusing on the mundane methods of making and accounting for the social world as it appears in everyday practice, scientific practice included. In fact, ethnomethodologists tend to be critical of reflexivity as it is used in other social sciences, where it often is an expression of academic virtue and a source of privileged knowledge (LYNCH, 2000). In ethnomethodological practice, reflexivity is presupposed between the work of producing the orderly properties of the social world and the accounts of this work that are its result (GARFINKEL & SACKS, 1986). An investigation of the analytic work was done in one recent conversation analytic study grounded in the ethnomethodological spirit, which not only focuses on the work of the analysts at work but also suggests that there is a paucity of such studies (ANTAKI et al., 2008). [11]

This study was designed to investigate analytic processes exemplified by a social science analyst in the course of instructing graduate students on qualitative research methods. There are two aspects to the data. First, the instructor externalizes an analysis of transcriptions the origin of which are unknown; second, in this naturalistic setting of graduate courses, the instructor not only analyzes but also formulates what she is doing or has been doing. [12]

The participant is a known scholar publishing the results of qualitative studies and on research methods. She has about 20 years of experience in academia. She tends to teach courses in qualitative research methods. On average, there are 5+ peer-reviewed journal articles per year; and she has a number of books on a variety of topics to her record. The studies tend to use ethnographic and applied linguistics methods, including discourse analysis and conversation analysis. The participant does not claim to be a (core) member of the communities of practice that do discourse analysis or conversation analysis/ethnomethodology. The audience for the analyzing aloud sessions are graduate students, generally at the Masters level, registered in an introductory qualitative research methods course. The parts of the protocol concerning the method of analysis are directed towards this audience, whereas the analyses themselves take the transcriptions as their objects as if the instructor was conducting her own research. [13]

The interpretation-aloud sessions and observations were conducted in the context of introductory qualitative research methods courses at the graduate level. To introduce students to the methods of analysis, to get students started on their course assignments, and to support her repeated reminder that "not anything goes," the instructor invites students to bring transcriptions of their interest and that they intended using for their final assignment. She likens her job of qualitative analysis to the work of detectives, using the sleuths Agatha CHRISTIE's "Ms. Marple" and Kathy REICH's "Temperance (Tempe) Brennan" or their male equivalents as examples, who must attempt to get the story right to prevent an innocent to be imprisoned or given the death penalty. The instructor framed the task as recovering from the transcription as much as possible about the situation. The owner of the transcription could then determine the extent to which the reconstruction corresponded to the actual video. In most instances, the class then watched the actual video of the transcribed excerpt. In class as well as during the analyses, she has already introduced students to the idea that they should not use high-level concepts and categories, but should be suspicious of them. The exercise actually prevents the introduction of categories because the reading of the data has to reconstruct the relations between the protagonists and their possible status based on the verbal interactions and any gestural/body movement information provided. Almost like a mantra, the instructor impresses upon students not to speculate but to use incontrovertible evidence that they can place their finger on or point to. She discourages students to speculate about contents of the minds ("s/he thinks, feels, intends, etc.") or about social aspects ("power over") and to concentrate on exhibiting the processes by means of which the mental or social come to be constituted in the chosen arena. She suggests, for example, "analyzing a transcript where we don't know much about the people forces us to look at what's going on," thereby emphasizing that the analyst is forced to investigate processes ("what's going on"). She emphasizes "not [having] talked about power" but instead "looking for pairs, question | response pairs." In this game, the analyst cannot draw on institutional relations to explain behavior but rather has to take the relations, verbal interactions, to hypothesize how power/knowledge differentials are actually produced. Similarly, she points out that knowing the gender of the speaker might lead the analyst to import presuppositions about the role of gender in relations into the analysis rather than showing how the interaction actually produces any differences ("If I can figure out from the discourse that there are differences that would be much stronger"). [14]

The instructor projects the transcriptions that she has received at the beginning of the lesson onto screen. She points to or highlights parts of the text currently read, or she gets up and actually points to relevant places in the transcript standing next to the screen. [15]

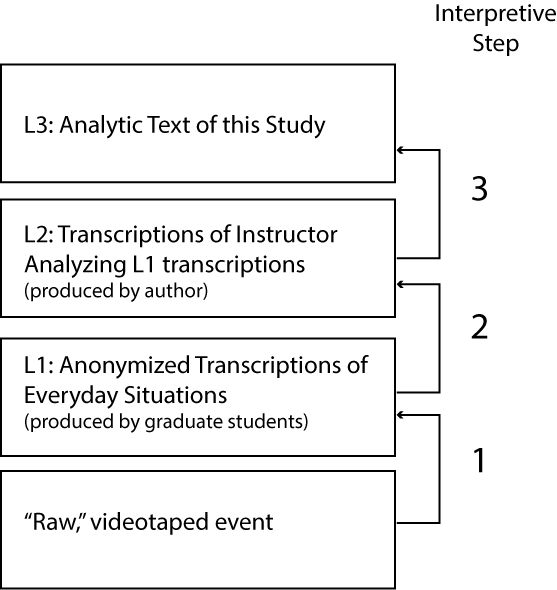

As a result, there are three levels of text that feature in this study (Figure 1). First, there are the anonymized transcriptions that the graduate students brought to the seminars (Figure 1, L1). The instructor analyzes these transcriptions aloud for the purpose of allowing the graduate students to observe an experienced analyst at work. I transcribed the videotapes of this work, thereby producing a second level of text (Figure 1, L2). It is this text that is the focus of the analysis in this study, which constitutes a third level of text (Figure 1, L3).

Figure 1: Interpretive levels and associated levels of text [16]

Importantly, the three levels constitute three levels of interpretation. The graduate students, in transcribing videotapes, already produce a form of interpretation: the transcription reflects their hearing and seeing of the episode as a whole. In fact, the analyst uses this in the interpretation of the transcriptions. On the second level, the instructor interprets the transcriptions; and on the third level, this author interprets what the instructor says analyzing the data. To make these three levels explicit, there are three corresponding levels of indentation: indented twice for the data students provided, once indented for the protocol as recorded, and normal text. [17]

The tasks for the protocols for the purpose of investigating expertise tend to be selected by the researcher, such as when they select a set of graphs from undergraduate science courses and present them to successful scientists (e.g., ROTH & BOWEN, 2003). In those (relatively few) instructional settings where an expert analyzes aloud for the purpose of exhibiting the practices of the discipline in instructional settings (e.g., FREY & FISHER, 2008), instructors themselves select the task, which, in fact, may prime their performance. The present is a naturalistic study where the instructor sets herself up to do analyzing-aloud sessions where she does not know beforehand the materials to be used. Because the students in these graduate classes constitute a diverse audience, there was a broad range of material transcribed. The materials included talk shows, comedy shows, congressional hearings, documentaries, broadcasts, school lessons, interviews, and parent-children interactions. For example, there were transcriptions from 1. a documentary produced and animated by David SUZUKI, 2. a kindergarten class in which Vivian PALEY, a well-known early childhood educator demonstrates a particular storytelling technique, 3. an interview and part of broadcast on a school that encourages rough-and-tumble play on school grounds. In some instances, the students deliberately used video and transcriptions with the (subsequently declared) intention to make the task of reconstructing the original event more difficult to the analyst. A sample transcription can be found in the Appendix. [18]

The graduate students preparing the transcriptions were not experts. Thus, the transcripts sometimes contained more information than what the instructor had indicated as to be included. In such instances, she tended to point to such facts and to how these might mislead the analyst in articulating identifying relations rather than imposing these. For example, she pointed out that using "teacher" might lead analysts to import "power" to explain what is going on rather than identifying forms of interaction that exhibit the differential institutional positions of the participants. In another example, a student had included "David SUZUKI" (a Canadian scientist, broadcaster, and environmentalist taking children to the Badlands in Alberta) as the name of a participant. As the instructor repeatedly pointed out, this might lead unsuspecting analysts to see interactions through a lens shaped by presuppositions of how a well-known scientist, broadcaster, and environmentalist is treated, regarded, and related to in interactions. [19]

The transcripts are non-technical, that is, not produced by specialists. They do not contain turn numbers or special formatting features. (Graduate students learn to do this as part of the course.) The instructor takes this into account, considering the transcriptions to be the result of mundane, commonsense reasoning that operated during their production. There were instances where the transcribers had used the same letter when in fact there were two different speakers, two speakers and one speaking in direct and voice-over mode, or used different speaker denotations to refer to the same person (e.g., "Vicky" and "teacher"). [20]

The database consists of 11 videotaped and 9 observed sessions during which the instructor analyzes transcriptions that students provided and that she had never seen before. Each session lasts about 30 minutes for a total of 6:11 hours of recording. Nine additional sessions, each lasting about 30 minutes, were observed. All student-produced transcriptions entered the database. The recordings were transcribed verbatim. [21]

The data analysis, informed by ethnomethodological and conversation analytic studies of work (LYNCH & BOGEN, 1996; SCHEGLOFF, 1996), makes use of the very methods that are the object of study. It first and foremost takes the transcribed lectures in which an instructor conducts public analyses of data and formulates some of the practices for the purpose of teaching methods for what they are: public displays of methods of analysis. The approach treats the data in an unmotivated and disinterested way, thereby contrasting common forms of analysis that make use of "a politically and socially charged description of, the speakers or the subject of the talk being analyzed" (ANTAKI et al., 2008, p.4). [22]

In this study, each video recording generally and the transcription more specifically is taken as natural protocols of data analysis activities, which are "seen as organized to produce the products they do" (ANDERSON & SHARROCK, 1984, p.103). With the data at hand, I engage in what is often recommended but much more rarely done: the application of a research method to its own practices (ANTAKI et al., 2008; ASHMORE & REED, 2000). I take the same attitude to my data as the instructor in the videotapes to the transcriptions that the students provided. The instructor both analyses and talks about the analysis for the benefit of graduate students in a course where they are to learn, among others, how to analyze data; the instructor's purpose is to encourage students to do such analysis with a high degree of rigor. The protocols, therefore, are representative of forms of data analysis in which rigor is exhibited and pointed to (in reflexive, formulating stretches of the talk). [23]

The present analyses and analytical stance are characterized by an acknowledgment of the structure of practical action, which can be articulated as the relation between some form of work and the notational particulars that constitute its accountable text or gloss (GARFINKEL & SACKS, 1986). These authors propose expressions such as "doing [playing chess according the rules]," where the first term "doing" refers to the lived work being accomplished and the bracketed term "[playing chess according the rules]" is a gloss or verbal account of that work. In this approach, therefore, any transcription can be viewed as a protocol or account of the work actually done. The transcriptions of the instructor-analyst's analyzing aloud then are accounts of her work, which we may gloss as "analyzing transcriptions for the purpose of exhibiting and teaching forms of rigorous data analysis. [24]

4. Reconstructing an Event From a Transcription: The Documentary Method at Work

Previous research concerning data analysis shows that the analysts make use of their familiarity with a setting to categorize and interpret the documents that had been produced therein (GARFINKEL, 1967). Thus, as described above, sociology graduate students tasked with the categorization of hospital records for the purpose of deriving patterns that describe practices of outpatient treatment actually used their knowledge of hospital practice to categorize the files. That is, in their classification work, the research goal to inductively derive hospital practices was circumvented because the analysts used familiarity with the very practices that the research was to induce from the classification of the hospital records. In this instance, the situation that had produced the records as one form of account of what has happened was known, as was the nature of the data, that is, the records were known to be records produced by a hospital. Another type of situation discussed above constitutes the coroner's problem, where the coroner, faced with a corpse, attempts to reconstruct a possible sequence of events, based on existing data, that could have led to the death of the person (ibid.). Again, the situation is known (i.e., corpse), and the context is searched for data consistent with a possible eventual trajectory that would have led to a corpse. The present situation differs from both of these situations, as the instructor knows neither the situation that produced the transcription nor what in the transcription might provide clues to the type of situation that it would be a document of. [25]

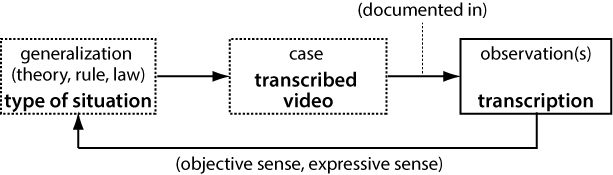

Globally, we may describe the analyst's work in this way: She assumes that the transcript is a document of some kind of social situation all the while being (initially) "in the dark" about which aspect constitutes a specification of the general, that is, the concrete that will lead her to the type of situation. The analyst recognizes that there is a kind of bootstrapping process necessary, because she "does not have a good starting point." She does, and formulates it as such, describe what is happening in terms of talk. That is, we observe forms of structuring of the generally linguistic material, in terms of objective characteristics, such as the relation between speaking turns, grammatical characteristics, special word choices, and so forth. From this emerge different forms of possible joint actions expressed that provide clues to the possible situations that might have led to this transcript (Table 1). That is, for the analyst there is an objective sense (factual aspects in the transcription, which is a protocol of the situation), an expressive sense (what the practical and discursive actions do), and a documentary sense (the type or types of situation that might produce the objectively given, indisputable facts). Table 1 lists, for the 11 recorded sessions, some of the objectively givens that the instructor-analyst highlights in each session, the different expressive senses she articulates, and the situations she hypothesizes as the sources of the transcribed protocols. Even without knowing situational specifics—i.e., the "thick descriptions" often asked for by peer reviewers—the analyst reconstructs types of situations based upon 1. factual materials taken from the transcriptions and 2. the intentions that (verbal) actions appear (are perceived by participants) to express. In the sessions, she tends to express what a situation "feels like," in an atheoretical or pre-theoretical way; and, through the structured, data-driven analysis she exhibits the invariants that situations like this one have in common. This requires the identification of transcription aspects that are invariant across situations rather than being specific to this situation, the specific one from which the transcription had actually been abstracted. In the following, I provide an account of how the instructor analyst moves through a transcription and ultimately arrives at a (subsequently judged as correct) situation description for the purpose of identifying invariants of rigorous data analysis (rather than identifying particulars about this analyst).

|

Dataset |

Objective |

Expressive |

Documentary |

|

1 |

- Names (David, Heidi, Amanda, Michael, Ashley), gender - Rocks = amazing landforms (camel-, pyramid-shaped) - Questioners and respondents - Most talk by David and Heidi |

- Preformatted-answer questions - Teaching-to-see questions - Teacherly discourse - Questioner knows the answer - David and Heidi "in cahoots" |

Do-you-see-what-I-see game Outdoor-center-guide-taking-visitors-around-a-park |

Table 1: Three levels of sense characteristic of rigorous data analysis [26]

Ethnomethodologists and conversation analysts emphasize that the members to the setting exhibit to each other what is required to pull off the social situation at hand. That is, members do, for example, the work required in a sequentially ordered, triadic turn-taking routine that assigns one person (often teacher) the first (initiation) and third (evaluation) turn and another person (often students) the second, response-producing turn. The members may not recognize, however, such an order in their turn-taking sequences, just as the children do not identify in their language-use the grammatical features. Analysts, such as the instructor participating here, especially when somewhat familiar with conversation analysis, will more easily recognize the routine and use this to postulate / hypothesize a possible situation. The purpose of the analysis is "to piece together the story from the materials, by eliminating some alternatives and leaving open others." (In the following, the source of the data that the analyst talks about is identified in parentheses, i.e., "Transcription 1.")

Fragment 1 (Transcription 1)

|

09 |

Heidi |

When we get around here, you want to take a look around and see if there's any landforms that look like something that would be familiar to you, not just like a rock. So what do you think that landform over there is? Does this one look, look like anything to you? |

|

10 |

Amanda |

Hmm. Oh! That rock right there looks like a camel. |

|

11 |

Heidi |

Oh ... no ... that's it! We actually have a name for this guy. We call him Fred the camel ... see the hump ... see the big droopy lips pointing to the left. And if you look off in the back, can you see anything else? |

The analysis

"So what do you think that landform over there is like?" You probably all play this as kids looking at the sky, "Oh, a sheep, oh, something else." That's what I kind of, what this generates the ideas. And if I am blank with the analysis, these are the kind of things that I build from. So I describe to get myself started. So, "What do you think that the landform over there is? There's one look like anything to you?" If I stop now, again, and I think about what kind of relations are there. Well the three, they haven't talked yet at all, they, whatever I said, the image I have. I haven't seen the video. The image I have maybe people unfamiliar with the wilderness and maybe younger people. There is David and there is someone functions in a situation where the kinds of questions seem to presuppose that the person already knows the answer. "So what do you think? What do you think that that landform over there is? Does this one look like anything to you?" It's a question that seems to already. There is something in this question that makes me think that the person already knows the answer or knows an answer. But it is not asked like, it's not like in a situation where a person says: "oh that looks like a sheep to me" or, you know, a question "what time is it?" And well and you respond. Whereas in teacherly discourse you will have: "what time is it?" And it is asked in a way where the person already has the right answer. And this seems to be the kind of a question and the person, the relation of the person to the others. So you see how even without having seen the video how, I am attempting to provide a description of the situation what's happening here. "Hmm. Oh. That rock there looks like a camel." "Oh, no, that's it!" I haven't been there, but the person saying, "that's it," confirms that the answer was the one that's prefigured, preconceived in the question. So "What do you think that landform over there is?" There is a children's game. Do you know what I think? Or you look at the some cloud: "I see. What do I see?" [27]

In this part of analyzing the transcription, the analyst reads what is grammatically structured like a question, "Does this one look, look like anything to you?" and then provides a description of the kind of situation that she associates it with the children's game "Do you see what I see?" She uses this, as she formulates, to generate ideas for the analysis. She reads the two questions again, and stops to orient her audience to the relations in play. She then describes a global situation that might have been the source of such a transcript, "people unfamiliar with the wilderness," and then specifies, "maybe younger people." She then articulates the nature of the data underlying the hypothesis: "The kinds of questions seem to presuppose that the person already knows the answer." The instructor elaborates that it is a kind of question where a person provides a possible description of the landform or where a person (genuinely) asks for the time. It is, she states, typical of "teacherly discourse," "where the person already has the right answer." After reading the next two turns, the reply to the question and what will turn out to have been the evaluation, she states having a confirmation that the question had a prefigured response. The turn "Oh, no, that's it" allows her to hear the earlier question as one with a prefigured answer. Here, the analyst did not just state the question to be of a particular kind but took it as a hypothesis about the possible nature of the question that was confirmed in and through the eventual evaluation turn. In fact, she first states several possible types of questions, suggesting that among these possibilities the question type with a prefigured answer appears more likely. The subsequent reading of the evaluative turn makes the alternatives—genuine questions where the questioner does not already have the answer against which the reply is to be judged—less likely. This approach bears similarities with Bayesian hypothesis testing, where evidence in favor and against two competing hypotheses is brought to bear on the change in probabilities. [28]

We see here a form of analysis that the instructor presents as a "first-time-through," where she generates hypotheses as she goes along, attempting to find confirming / disconfirming evidence. She points out that there is an initial sense that the locution might be of the type that presupposes the answer, and it is what "appears later on shows that [Heidi] already has the answer, this answer in mind." In contrast typical of confirmation bias, where individuals identify situations as confirming previously made taken-to-be factual statements, the analyst here explicitly articulates multiple possible forms of questions, though assigning higher probabilities to the one with prefigured answers, and using subsequent information to weigh on the relative probabilities of alternative hypotheses. This is evident when she arrives at the end of the third turn in the transcribed fragment, "And if you look off in the back, can you see anything else?" She says, "The question is of the kind that in the literature has come to be called by some 'preformatted'." [29]

In this instance, the analyst identifies an interactional feature, a form of question and the sequential ordering of turns, which fit the initiation-reply-evaluation (IRE) pattern she is familiar with. Although this is identified as a teacherly form, it is not used to specify the type of situation from which this transcription may have been derived. There are formal properties of the statements (locutions), semantics and syntax, and of interaction sequences. These are characterized in terms of expressive sense, teacherly discourse or person who knows the answer (e.g., "Do you see what I see?"). In other transcripts, she identifies the same type of sequence where she points to evidence that the questioner already knows the answer, such as in a staged interview of eighth-grade students invited to demonstrate how they use a smart board or when parents read with their children, read images, and, thereby, teach them reading images ("Do you see the bird?"). [30]

She derives that two of five participants in a situation are "in cahoots" from the fact that one (Heidi) asks a question and another (David) formulates providing a clue to the answer when the other three do not immediately respond.

Fragment 2 (Transcription 1)

|

18 |

David |

Very good! Has Fred changed that much while you've been here Heidi? |

|

19 |

Heidi |

Not that much although he did get a bit of a facelift, he's lost his double chin. But, uh, we're really concerned that the cap rock on the hump of Fred may fall off. That ironstone. And if that falls off the hump could erode away very quickly. |

The analysis

So David asks Heidi, "has Fred changed that that much while you've been here Heidi?" So David appears to know that Heidi is here or has been here more than once. The question also shows that Heidi has been here more than once. David knows; and David may actually be less frequently there. So because he, "while you've been here," if he says "while you've been here" it could be that Heidi has been working in that area. [31]

Without pointing directly to the grammatical feature, the prepositional conjunction while and the description "you've been here," the analyst uses it as a document for 1. Heidi has been in the location more than once, 2. David knows that Heidi has been in this location more than once, 3. David may be less frequently in this location, and 4. Heidi is permanently working in the (geographical) area. That is, there is a specific landscape feature, which David knows about and, as can be taken from his earlier giving a clue, has been in the location more than once. The grammatical features are consistent with Heidi's permanently working in the location for some time so that she would be knowledgeable about specific changes in the landforms that David may not be familiar with. In fact, she points out that there are multiple hearings of the utterance as a genuine question to which David does not know the answer, or one that is designed to instruct the children about something by having Heidi respond to a pertinent question. The question then is not to set Heidi up in an IRE-type sequence but to expose something unknown to the others present without doing so in person. It is a staging question to which David might already know the answer, but the purpose of which is not to test Heidi but to have her provide an answer for the other individuals' benefit. [32]

The analyst notes that it is Heidi who earlier had introduced the name of the camel, which now can be heard to be consistent with the fact that Heidi is more familiar with the place. The analyst points out that the "we" (in "we call him Fred") probably does not actually include David but to others working, like she does, in the location. The instructor points to the very fact of having given a name to a landform points to familiarity with the place. And because she talks to (for) the three others, they are definitely not included in the "we," for this would be stating the self-evident. [33]

The analyst then formulates bringing together the present information with the fact that David (SUZUKI) is a known environmentalist and what she has identified as the type of questions with preformatted replies that are being asked. She further points to the (grammatical) clues that Heidi has been working in the area for a while, and to those that Heidi is in their particular location more than once. She describes a possible scenario that could have led to the transcript at hand:

The analysis

I could for example hazard a guess that Heidi is something like a ranger or a naturalist working in a particular area. There are three visitors to that park, and David is there. David works with Heidi for some time, they are in cahoots. This is my data: They know the questions and the answers that come. But David also gives away clues that Heidi has been there for a while. They actually be ... there more frequently than David. And he asks the question, "Has he changed?" [34]

With this description, the instructor-analyst has captured the essence of the situation, which the class subsequently ascertained by watching the clip. How does the analyst accomplish reconstructing an event based on the transcription without any more or less thick ethnographic description (often required by the reviewers during the peer review process)? She does so, as shown in this example, by treating the transcriptions as naturalistic protocols that exhibit aspects of the accountable work people do to produce the situation currently unknown to the analyst. That is, without acknowledging it as such, her analysis uses the transcription as an account that glosses the work done by the speakers. The analyst's self-posed problem is to find the problem that the speakers are solving. The protocol is the solution, the work that the participants did to do what they were about to do. The people in the transcription are solving some problem, and the transcription is the protocol of how they are doing and achieving it. So the analyst has the solution to the problem that her participants are solving and have solved, and she has to find out what the problem was in the first place (e.g., Heidi and David pointing out the children the special features of the Badlands). The analyst tends to take each locution as a piece of documentary evidence of a conversation in the making, where the participants themselves do not know what they will ultimately have said. The analyst's declared intent is to work up the sense that participants have for what is happening and what they are producing. For this reason, she focuses on turn sequences to see how the participants themselves react to and act upon the previous (discursive) actions. [35]

In the analyst's work, we may observe three levels of statements, which are actually the three levels of sense that constitute what has been called the documentary method of interpretation (MANNHEIM, 2004 [1921-1922]). Although the documentary method initially was attributed to sociological work intended to derive the worldview of an era, subsequent work suggests that the documentary method of interpretation, at least partially, is an everyday method common to laypersons as much as to professional sociologists (GARFINKEL, 1967). MANNHEIM's notion of the documentary method of interpretation is narrower than GARFINKEL's (BOHNSACK, 1983), but it is precisely in the former's version that the instructor-analyst appears to operate. One difference is that GARFINKEL is concerned with the holistic sense of a situation, in which there is no segregation into three levels; professional analytic work, such as that investigated here, does indeed make such distinctions (e.g., ANTAKI et al., 2008). Pertaining to the analysis of transcriptions, at a first level the analyst takes note of the objective features such as what the participants actually name and reveal in their talk (Table 1). Any verbal articulation, such as "How are you today?," constitutes an action that points to and reflects an in-order-to orientation. However, it acquires its sense only in a shared system of anticipations and understandings (BOHNSACK, 1983). The greeting will function differently when uttered by the doctor in a consulting session, a person addressing a neighbor, or a rock star orienting to the audience during a concert. [36]

The names David, Heidi, and Amanda when participants address each other tend to give away the gender of the individuals; because the participants point to phenomena that they refer to as "landforms" and "rocks," very specific features of the setting become objectively and immediately available to the analyst. However, any one fact, such as in the preceding "How are you today?" may not point to a specific type of social situation. The other two levels are available to the analyst in a mediate, derived way (therefore ">" in columns 2 and 3 of Table 1). At a second level, there is the (intended) expressive sense. Thus, the statement "How are you today?" may be part of a meeting opening or a part of a question | response pair about a person's health status etc. It pertains to the analyst's sense of what some action actually does. For example, hypothesizing that a particular phrase may be heard as a question, assertion, or command refers to the sense expressed in and through a verbal or described physical action. At a third level, there is the documentary sense.1) In the documentary sense, what is given in the situation is taken as document (evidence) of something that exceeds what is objectively available or (intended to be) expressed. That is, the situation as a whole is co-expressed in the concrete locution. It is this third sense that integrates the objective and expressive senses, because even though these may change, they all point to the same phenomenon. This something may be as narrow as a form of activity or a type of event (GARFINKEL, 1967) or as wide as the spirit of an era (MANNHEIM, 2004 [1921-1922]). For example, the types of questions that David and Heidi ask typically are found in didactical situations, which are also characterized by other features. Even though the features and the objective aspects are different for different classroom situations, they are different documents (manifestations) of the same (type) of situation. MANNHEIM suggests that an analyst's capacity to capture homologies in the face of very different objective and expressive forms is something special that has nothing to do with addition, synthesis, or abstraction of common features. The capacity is based on seeking and recognizing part-whole relations, where the parts, though they may be very dissimilar are manifestations of the same whole (e.g., different physical and psychological characteristics of the members of the same family). In the present instance, the instructor-analyst treated the transcriptions as documents of societal events (a guided tour in an outdoors nature center, a lesson teaching storytelling, an interview subsequently featured as part of a broadcast). That is, the analyst takes the objectively available features articulated by the members to the specific setting to hypothesize a range of forms of individual and social actions, and then takes both as documents of one or more types of situations that might have given rise to the transcription, which, thereby would be a verbal protocol of the former. [37]

Cultural objects and social situations are—like material objects—characterized by what is objectively available to participants. The objective sense related to what is indisputably given, constitutes the basis upon which everyday life and its interpretation is built (MANNHEIM, 2004 [1921-1922]). It is not surprising, therefore, that the instructor-analyst points to what can be identified as indisputably given in and through a transcription (Table 1). For example, in the following two excerpts, the analyst takes the gender of the individual talked about as indisputably given, as is the fact that whoever "she" is can be seen on the part of the intended recipients of the statement, and that she does look or intends (is intended) to look like a little girl.

Fragment 3 (Transcription 2)

|

04 |

P |

Does she look like a little girl? |

Fragment 4 (Transcription 10)

|

14 |

I [46] |

here may be some people, some parents who think, "hmm, I don't want my children, my little girls, playing bullrush!" What do you say to those people? |

|

15 |

M1 [47] |

Well, if you think you can't handle it, well then, don't play ... that's just pretty much it. [38] |

To derive what the statement is intended to do, its intended expressive sense, the instructor-analyst always identifies what is objectively given and can be pointed to. It is the basis of the data-driven method of interpretation that she encourages students to emulate and formulates to be an instructional goal. Names constrain hypotheses about the gender and cultural origin of a speaker or person talked about. Adjectives such as "little" that modifies "girl" further provide objective constraints on participants, things and persons, and events. [39]

The analyst points out that the slightest descriptions may influence analysts in the way s/he reads the data. Thus, a description such as "little girl" may lead the analyst to read the data in terms of "little girl" rather than taking actions and talk for what they are. Thus,

"as soon as we look at little girl, then we might look at it as 'little girl' rather than as another speaker. And as soon we look at someone as the 'little girl' then all our other cultural understanding of 'little girl' comes in." [40]

She recommends rendering the familiar strange as one of the strategies to break with the cultural habits that come when such descriptors as "little girl" and "teacher" are used. [41]

The language-in-use (or lack thereof) provides clues to the age of the participants, such as when in the conversation involving three individuals one of them says "Fern when she first got Wilbur he was too small to get selled and when he got bigger they selled." She comments that an experienced English teacher would be able to estimate the age more precisely from the type of grammatical error made in this situation. In that same context, one of the individual's used the word "inference," which troubled the hypothesis about the age of the participants, because it is more typical of teacher talk. Yet in the interaction, the person was in the position of a student, responding to another one who had a special role of supporting the generation of possible future events in the text being read and discussed. But the person who used the word "inference" also made a prediction about what might happen in subsequent chapters, which is inconsistent with the role of a teacher who already knows the story. Language also was highlighted in an instance where three individuals appeared to be discussing a book that they are in the course of reading. The participants hypothesize about what might happen in the next chapter and use words such as "inference" and "prediction," and are reflexive about the use of questions ("My question to you was ..."). The analyst uses these pieces as documents for a particular type of societal situation: A teaching strategy to get children read critically ("this may be a teaching strategy for teaching kids to read, and to read critically. Then what you want to have is them to anticipate, just what might happen"). [42]

The analyst attends to grammatical features such as the differences between a definite and an indefinite article, especially when these occur side by side. The definite article points her to something that those in the situation already share and can orient to. The same is the case for the use of the demonstrative pronoun "those." The analyst suggests, "We seem to be in the middle of something. Not at the beginning because there is something about "like some of those questions you can answer.' So it's about the questions they can answer." An example where the in/definite article arises in the transcription is provided in the following excerpt.

Fragment 5 (Transcription 2)

|

08 |

P |

Would you be the little house? |

The Analysis

So Would you be the-the little house? Now it's not Would you be a little house. It's the little house. Here's Does she look like a little girl?, Would you be a little boy?' And here it's the and that might actually turn out to be significant in the sense that "a boy" [Turn 06] and "a girl" [Turn 03], it's indefinite. But here it's a definite article. And if the teacher uses the definite article whatever is to come may already be pre-figured or known to the participant namely there has to be, there is some house ... to be involved. [43]

She describes the use of the definite article as "striking her interest," because "there is something definite about what is to come." This subsequently is taken up as a clue to the fact that Mikayla is not telling a story unknown to everyone else, such as frequently during "show and tell" or "circle times," but that the teacher already knows the story, which she assists the girl to tell. The instructor offers "a hypothesis": "The teacher somehow knows Mikayla's story already, and what is to come, and so she appears to be scaffolding or whatever, Mikayla's story to be enacted, in that situation." [44]

Objective features are important in the sense that they allow a reconstitution of the world that has given rise to a protocol through the eyes of those involved. However, the analyst does not consistently point out the same types of objective fact; instead, what facts come to be highlighted is a function of the sense about the situation as a whole, which, in turn, is a function of the objective sense that is associated with individual words or statements. That is, the analysis scours transcriptions for anything that is available to the participants and that they take to be undisputed as factual; but this scouring process itself is determined by the overall, documentary sense that is in the process of developing as the analysis proceeds. If there was evidence that the factual nature of something is actually contested, it is this contest itself that can be objectively pointed to, for example, by means of alternative naming or describing of whatever is the object at hand. Reconstructing the viewpoint of the actors or witnesses in the situation or as available from the transcriber is perhaps the most important aspect characterizing the analyzing-aloud sessions. [45]

6. The Viewpoints of Actors and Witnesses

Whereas in many theoretical approaches, (social) relations are the result of individuals entering in an interaction, the cultural (societal)-historical approach takes societal relations as the phenomenon that constitutes all higher psychological functions, consciousness, and personality (LEONT'EV, 1983; VYGOTSKIJ, 2005). Anything that can be attributed to mind is a societal relation (first) and, therefore, enacted in relation. From the ethnomethodological perspective, it is in the relation that institutions become accountably rational (LYNCH, 2000). We do not therefore need to know institutional relations beforehand, but, as FOUCAULT (1975) suggests, differential knowledge and power are effects of relations. In the present study, the instructor-analyst enacts what might be considered a backward analysis, where institutional positions such as between teacher and student are the result of the relational work articulated rather than the conditions of this work. The expressive sense therefore is derived from the ways in which the participants in the transcriptions related to each other (Table 1). The analytic perspective taken here also characterizes the work of the instructor-analyst, who reconstructs the situation based on what the speakers exhibit to each other and what they and their witnesses make available. [46]

The analyst may in fact hypothesize a particular type of situation, for example, irony, but then set the hypothesized in relation to another turn to see whether what can be heard as ironical was in fact heard in the situation as such. As part of the analysis, a first step might actually be a form of nontechnical appreciation—e.g., identifying a situation as rudeness. But to do so "is very definitely meant to be a first characterization of something in front of you, into which you then drill down and excavate, to discover its structure and its connections to the terrain around it" (ANTAKI et al., 2008, p.26). This statement reflects the fact that we do not generally experience situations in terms of three layers of sense but instead we experience situations as wholes.

Fragment 6 (Transcription 4)

|

05 |

Kent |

why did he want to exercise when he could make someone happy ... by making bacon |

The analysis

Okay here is a sort of a reflexive comment: Why would you want to exercise when you could become bacon and make someone else happy eating bacon? So that's my hypothesis, maybe he wants to exercise, so there wasn't much exercising, and then this may be heard as an ironical comment, Why would you exercise if you could become bacon? And here, maybe he wants to lose weight, and so he doesn't have to become bacon? [47]

There is a focus on pairs of turns rather than on the individual turn, for the orientation to the individual turn might lead to inferences that do not actually matter to the unfolding event. In one instance, for example, she points out that "one may hear ... as almost ironical," a hearing to be discarded because the following turn "does not play with it," so that irony does not have an explanatory role "in the conversation." [48]

The actors participating in the production of an activity of which the transcription constitutes the protocol do not know what will come of their doings. What their (discursive) actions bring about will have been known to them only after the fact (SUCHMAN, 2007). Analysts interested in recovering a situation as it appeared to the original situation follow a strategy of "first time through." In this mode of working, "the objects worked on in the first time through are novel and thus fluid and indeterminate" (ASHMORE & REED, 2000, §37). The analyst both followed this strategy (e.g., as shown above) and formulated the need of doing so for the purpose of her audience. Thus, she points out how a statement such as 'The grade eight students [are] explaining how they use a smart board" is possible only a posteriori. For at the time someone starts to speak it cannot be known whether s/he will have explained anything in the end. She further suggests, "first-time through means that nothing that has happened after, nothing that I knew only afterwards can be used in the analysis" and "I use the method to show what is going on, what people actually make available to each other." Although the analyst begins to "overhear" the conversation somewhere in its course, the first-time-through perspective still gives her the sense of an unfolding project that captures the participants' own uncertainty about precisely what it is that they will have produced once everything is said and done. [49]

Reading the transcription with the correct temporal order is important for hearing speakers in particular ways. For example, in a transcription where a teacher apparently assists children in play-acting a narrative, the precise temporal order of action and text matters. The statement, "Okay, little house" can be heard differently when it precedes a girls representation of a house, accompanies it, or follows it; and it also depends on the intonation, for produced with a rising intonation it may be heard as a question, whereas with a falling intonation, as a confirmation. If, for example, in a situation where a teacher is saying something that can be heard as an invitation ("Okay, a little house") but a child has moved or moves with the beginning of the locution, then she may takes this as "only the indication that there is a shared anticipation of what is to come. And even though the teacher seems to provide a main narrative, the children act as if they already knew what was coming." The temporal relations allow her to attribute different probabilities to the hypotheses concerning the function of a statement as running commentary of an observable event, invitation/instruction, or after-the-fact description/affirmation of what has happened (see below). [50]

An important ethno-method for making aspects of social life visible is denoted by the term formulating (GARFINKEL & SACKS, 1986). Formulating occurs when a member to the setting says with a limited number of words what is, was, or will be happening. Formulating contributes to making "activities ... accountably rational" (LYNCH, 2000, p.43). When an interviewer begins by saying, "Let me ask you a question," then what will come after already has been formulated. Formulation also occurs when replies to a statement saying that she felt insulted and the original speaker says that he was only joking. In such instances, there are alternative descriptions of precisely what has been done. Formulating occurred at three levels: 1. in the situation by participants for participants, 2. in the situation by a participant for a different audience, and 3. in the transcription by means of punctuation and other features. [51]

6.2.1 In situation for other participants

Picking out formulations is a pervasive aspect across all sessions where and when this occurs. That is, the instructor-analyst picks out statements as formulating what can be seen or how a situation can be seen. Sometimes even a statement such as "Okay, a little house" may be heard as a formulation of what is currently happening: a child is enacting a little house. The analyst encourages her graduate students to focus on formulations rather than to speculate on inaccessible intentions, thoughts, or beliefs. The very fact that something is formulated provides her with clues as to the kind of social situation that she is in the process of attempting to uncover because the formulations render problematic or articulate what was, is, or will be happening.

Fragment 7 (Transcription 4)

|

01 |

Sophia |

?? was that a question? |

|

02 |

Kent |

(no no - ) |

|

03 |

Kent |

(yeah, no), that was like an inference |

The analysis

Was that a question? So someone appears to have asked a question, this was a question whether there was a question, uh no no yeah no, that was like an inference. Okay, here we have a question | response. We don't know who spoke before, but you see the question | response, negative, and here yeah, no, that was like an inference. So perhaps Kevin might have said something; and it was not actually a question but an inference. So yeah no it was, so there it's both a question and not a question. And then we see an elaboration of what it was. [52]

In another transcription, when she comes across a statement such as "wait a minute, let me finish the freekin' sentence," the instructor-analyst takes this to be a formulation of the fact that the person has been cut off by the preceding speaker and prior to having finished saying whatever she was in the process of doing so. Formulations do not only occur in the forms of verbs, where the nature of an action is named and thereby brought to attention. Adjectives, too, formulate the nature of a (material) aspect of the situation. Thus, in the statement," What it shows is brainwave activity basically. It's a very simple but fairly accurate machine" (01, K, Fragment 8, Transcription 6), an aspect of the context, a device showing brain wave activity, is characterized as a type of device that shows something "basically," that is, in general. Further descriptions of the device as being "very simply" and "fairly accurate" become, in the reading of the analyst, formulations of the type of device being used and what the situation then might constitute (i.e., a demonstration rather than a real experimental setting). The instructor-analyst points out that the use of these adjectives "co-articulate something, for example, that this is a demonstration, a lesson for the specific audience of the talk. [53]

Formulations may appear in the form of narratives of what is presently happening. In the following fragment, the analyst hears "Okay. A little house" as a running commentary of events unfolding before the eyes of those present.

Fragment 9 (Transcription 2)

|

08 |

LG |

[walks towards LG2 and stands beside LG2] |

|

|

LG3 |

[stands up, body swinging, hand to mouth] |

|

|

LG2 |

[grabs dress, looks at LG3,walks away from LG3 behind LG to stand beside LG] |

|

09 |

P |

Okay. A little house. How should Mikayla since it's your story how … should she make herself? |

The analysis

So we have uh, we will have a pairing and the little house and is the third. Grabs dress, looks towards LG three and walks, stands up, body swinging from side to side, hand up to mouth, okay a little house. So, whatever has happened, we can see this as an event and the commentary. This ((A little house)) describes what has happened here, so whatever this configuration tells us, is being described. A little house. Okay then a little house has been formed in this particular situation; and those present, they'll understand that the little house has been formed. So it's both as a description of what was happened and a description of what was supposed to be, Would you be a little house? So these events have produced the little house. [54]

The analyst notes that the teacher invites children, and she comments on how the story plays. There are two levels to teacher's contributions: one organizes whatever event is (to be) unfolding and another one comments what the children are playing out in the situation. Similarly, a locution such as "Would you do that?" without further information is ambiguous, for the "you" might be a specific person in the situation, who, by means of a body movement and orientation may be the selected recipient, or it may be a general "you" in place of "one," "Would one do that?" ("Oriented, she addressed a particular person, not just generally.") [55]

6.2.3 Narrative commentary from outside

There are repeated instances in the database where the transcriptions contained two different audiences without being marked as such: a video 1. shows a teacher and then shifts depicting the teacher talking about her teaching, 2. features a talk show where the host engages the guest and then the audience, or 3. is a broadcast showing the situation being reported on and the anchor's commentary. In these instances, although the transcriptions that the students produced do not indicate the different level—sometimes for the after-the-fact stated intention to make the task more difficult—the analyst detects such differences in the audience for which a stretch of talk is designed. If this is so, then the talk itself (self-referentially) exhibits features that allow participants and analysts alike to know what kind of situation they are in. [56]

In one instance, for example, she points out three different levels, where the "I:" in turns 16, 18 and 20 actually refers to two different individuals (as it subsequently turns out to be). In fact, the instructor hypothesizes there to be three different registers, one between 16 and 18, who might be the same person whereas 20 is a different person speaking in a third register.

Fragment 10 (Transcription 10)

|

16 |

I |

So what do the parents think? |

|

17 |

P |

Some parents have come and asked about it. They've wanted to be reassured ... but I think generally, I've had really good support from them. [Kids yelling and waving their arms in front of the camera.] I think our understanding of what is safe really means, is changing. And actually, kids are safe doing things, that, maybe we have thought, weren't safe ... for quite a few years |

|

18 |

I |

For these educationalists, the risks involved with a bit of rough and tumble, are far less than the risks associated with an activity. |

|

19 |

P |

The only time they get into trouble is when they're bored ... and they really don't get a chance to be ... [laughter] |

|

20 |

I |

And yes, before you ask, the kids do go back in the class after playing bulrush, with a bit of mud ... but the full on mud sliding, well, that's before they head home ... to the washing machine I presume. |

The analysis

[T]he interesting thing is that up there above ((Turn 16)), the person was in a questioning position. As if he or she was interviewing. Whereas here, this ((Turn 20)) is a statement that is as if the person knew. So, this ((Turn 16)) seems to be a different register than this one ((Turn 18)), and this one is again a different register ((Turn 20)) that was spoken to a different audience. The audience that followed the camera, and the other is oriented towards the people. Do you see how this feels different than this ((Turn 20)), this one ((Turn 16)) and this one ((Turn 18)), this one ((Turn 20)) is about that situation ((above Turn 20)), and this person I: ((in Turn 20)) must be familiar with the situation and now is talking for someone else. Because it is not a question, because the person knows that after playing bulrush the kids are going back. So the person already found out, from previous parts of that, or even before the camera turned on that person has found out and is now explaining, to whoever the audience, the recipient is of that this explaining that yes. May be a commentator. [57]

In another situation, the analyst repeatedly articulates "Let's look at first impression" as a key turning point where the voice changes. She first gives the example of the change of voice in novels, and points to the quotation marks that one might find there to distinguish the two levels. She then focuses on Vicky as setting "us" up. The analyst then articulates a situation in which such a set up might occur: A teacher telling others about how to teach. Vicky prepares the students for a demonstration "to give a first impression," and then talks at a different level, where she explains to other teachers as the audience ("we're the teachers, we listen to Vicky").2) She subsequently uses that there are two levels of talk from the fact that a second voice talks about Vicki: "Vicky's using traffic lights together with the controversial no hands up, policy." She takes this as the voice of a commentator talking about what Vicki does, who, in other parts of the transcripts, is actually shown teaching a lesson ("perhaps a voice-over, there seems to be an explanation of what's going on, if this is the case and here ((Turn 01)) we're in a real classroom, and there's ((Turn 04)) a commentator explaining to us what is happening." She actually hypothesizes three levels of talk, Vicky teaching, Vicky talking about teaching, and someone else commenting on what Vicky does. Focusing on the two turns "Does anyone know the relevance of that question? Hands down." and "Vicky's using traffic lights together with the controversial no hands up policy," followed by further "classroom talk," the analyst notes "the commentator commenting on this teaching lesson might tell the audience, 'Now you need to watch-watch, it's a hands down policy,' and the next instance what we see [is] the teacher implementing a no hands up policy." [58]

6.2.4 Transcriber as witness

The graduate students had been instructed to prepare transcriptions that contained "no clue" as to the situation. But during these sessions, the analyst repeatedly points out that there are in fact clues that students had not thought about as such. In these situations, the instructor-analyst treats the transcriber as a witness of the original situations. She treats something like a question mark in the situation as an index to the expressive sense on the part of the witness, who might have heard a question; and this is taken as an indication that the original statement could be heard as such ("You have an exclamation mark, which ... is sort of made as an assessment"). For example, she points out that a student "ha[s] an exclamation mark, which points [out] that this [was heard] as sort of, made as an assessment." That is, the analyst makes use of the ethno-methods of observers—here the transcribing student—to understand situations in particular ways and draws clues about the data drawing on the cultural competence of the student. She explicitly points to the uses of question marks, pointing out that the transcriber has heard a question, and then suggests that this does not mean that in the transcribed event the locution has functioned as a question.

Fragment 11 (Transcription 2)

|

04 |

P |

Does she look like a little girl? |

The analysis

We also see the question mark here and what I suspect is that the transcriber is a competent speaker of the language and here is a question [mark] if there's a there's a question. Does she look like a little girl? Uh grammatically we grammatically that one is like a question. But the question mark also could mean that the prosodic feature, I mean, that the pitch has gone up. [59]

The punctuation is indirect evidence, where the analyst draws on the mundane analytic competencies of the people transcribing the video to articulate their understanding of what is being observed: a question, exclamation, statement. In the following example, she takes into account the quotation marks that appear in the student-provided transcription.

Fragment 12 (Transcription 4)

|

18 |

Kevin |

Yea, cause it said ah I got a plan [60] |

The analyst comments, "Yea cause it said I got a plan." So this student is generating a hypothesis or uses some evidence from the text. Actually, the transcriber gives us a clue that this was a quote. You can hear whatever was said as a quote. The transcriber knows that this is from the book or can hear that it's a quote." She then goes on explaining how she had abandoned in another session the hypothesis about possibly missing quotation marks, which would have provided a clue about two levels of talk. In the present situation, the quotation mark is consistent with the hypothesis of two levels of talk, one pertaining to the hypothesized situation of a book that students are reading and discussing. [61]

"[The] inference-making machine ... can deal with and categorize and make statements about an event it has not seen. And the first thing about the sort of events it can handle is that they can be sequential events" (SACKS, 1992, p.115).

6.3.1 Focus on ordered and ordering turn sequences