Volume 17, No. 2, Art. 27 – May 2016

Conceptualizing Quality in Participatory Health Research: A Phenomenographic Inquiry

Jane Springett, Kayla Atkey, Krystyna Kongats, Rosslynn Zulla & Emma Wilkins

Abstract: Participatory approaches to research are gaining popularity in health and wellness disciplines because of their potential to bridge gaps between research and practice and promote health equity. A number of guidelines have been developed to help research-practitioners gauge the quality of participatory health research (PHR). In light of the increasing popularization of this approach in the field of public health, there is a need to check in with current practitioners to see if their practices are still reflective of past guidelines. The aim of this study was to understand how research-practitioners currently conceptualize the quality of participatory health research in particular. Using phenomenographic inquiry, we interviewed 13 researchers who described their experience of PHR. We identified 15 categories of description and visually represented the relationship between the categories using an outcome space. Our findings suggest that conceptualizations of what is considered high quality PHR have remained consistent. This reliability bodes well for the development of quality criteria for participatory health research. We discuss implications for scaling up this study to compare quality criteria beyond a North American context.

Key words: health and wellness; participatory action research (PAR); phenomenography; research quality; validity

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1 Participants and recruitment

2.2 Data generation

2.3 Analysis

3. Results

3.1 Categories of description

3.2 Outcome space

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Participatory approaches to research are gaining popularity in health and wellness disciplines because of their potential to bridge gaps between research and practice, promote social justice and create the conditions necessary to facilitate individuals' control over the determinants of health (CARGO & MERCER, 2008). In this article, we use participatory research (PR) as an umbrella term that covers a variety of participatory approaches to research including participatory action research, community based participatory research, participatory rural appraisal, popular epidemiology, collaborative research, appreciative inquiry and many more (INTERNATIONAL COLLABORATION FOR PARTICIPATORY HEALTH RESEARCH [ICPHR], 2013). [1]

The term or concept of "quality" has been largely discussed in the context of guidelines that can be used to assess a particular study in regards to the nature of the knowledge produced (MAYS & POPE, 2000) and its set of methods used to obtain such knowledge (BERGMAN & COXON, 2005). As suggested by MAYS and POPE (2000), assessing quality is important to distinguish "good" and "poor" research. Quality can be assessed at the end or throughout the study (REYNOLDS et al., 2011). According to Uwe FLICK (2007), concepts of quality will have different meanings for novice researcher (e.g., How do I trust my results? Have I applied the methods in a correct way?), for funders (e.g., Have the results of the study been consistent and adequate for what is to be studied?), for journal editors (e.g., How was the research reported and are results transparent?) and for readers (e.g., Can I trust what I have read?). The issue of quality has been largely focused on the nature of knowledge (MAYS & POPE, 2000). Assessing quality has been challenging given the multiplicity of research approaches and their diverse backgrounds, intentions and strategies (FLICK, 2007). Debates have centered on whether 1. criteria for qualitative studies should follow post-positivist/realism conceptions (i.e., reliability and validity) or interpretivist/constructivist conceptions (i.e., credibility and transferability) (MAYS & POPE, 2000); 2. indicators (i.e., a checklist) or guidelines (i.e., considerations that can be taken into account and be reflected on throughout research) should be used (HAMMERSLEY, 2007), and 3. such criteria can be used across different approaches or only created within a specific research approach (FLICK, 2007). [2]

Participatory forms of research (e.g., participatory research, participatory action research, action research, community-based participatory research) can be perceived as approaches instead of techniques and methods: illuminating that knowledge is co-constructed relationally and through dialogue (SPRINGETT, WRIGHT & ROCHE, 2011). Accordingly, Jane SPRINGETT and colleagues suggest that issues of the quality of practice in participatory research can be assessed according to the degree that it aligns with the core values and principles of which participation is at the center: a perspective that is adopted by researchers within action research (see BERGOLD & THOMAS, 2012; REASON, 2006). Jane SPRINGETT and colleagues (2011) assert that quality is a product of maintaining a core set of values and principles that in themselves are negotiated in different contexts. [3]

Given this complexity, it can be difficult to assess the quality of participatory research projects (BERGOLD & THOMAS, 2012). However, a number of guidelines have been developed to help researchers gauge PR quality. The most well-known and often cited criteria for assessing PR quality in a health context are those developed by Lawrence GREEN and colleagues (1995), revised by Shawna MERCER et al. (2008), and by Barbara ISRAEL, Amy SCHULZ, Edith PARKER and Adam BECKER (1998). There is a need to revisit such criteria in light of the changing landscape and growth in popularity of participatory research over the last ten years (SPRINGETT et al., 2011). There is a concern that the label "participatory" is generously attributed to cover a diversity of approaches (BARRETEAU, BOTS & DANIELL, 2010). As such, the diversity of approaches can produce confusion. For instance Robin McTAGGART (1991) has observed that despite some considerable agreement about what participatory action research is, literature searches for terms, "participatory research," "action research" or "participatory action research" yield diverse research approaches that can be confusing and meaningless. Further, in 1995, Andrea CORNWALL and Rachel JEWKES remarked that "participation" was becoming a cliché, and the concept could be mobilized to co-opt local people to the agendas of others. They called for greater discipline in the qualification of the meaning of participation. Jarg BERGOLD and Stefan THOMAS (2012) echo the need for further consideration in assessing the quality and rigor of participatory projects stating "a more intense discussion of quality criteria will be of central importance" (§86). Accordingly, creating "an ongoing dialogue between practitioners ... on the quality, validity and ethics of what they are doing ... guards against slipping standards, poor practice and the abuse or exploitation of the people involved" (McGEE, 2002, p.105). Such continued reflexivity contributes to important modifications in methodology (COOKE & KOTHARI, 2001) and thus helps to bridge gaps between theoretical and practical tenets of PR. [4]

This phenomenographic study provided an opportunity for academic researchers in Alberta, Canada to reflect on the ways in which they gauge quality in participatory health research (PHR). In doing so, we strived to attain a collective understanding of aspects that characterize PHR (i.e., core values and principles) and thereby deepened our understanding of how PHR is practiced by a group of public health researchers. The term, PHR is used as an umbrella term to encompass a variety of participatory approaches in a health and wellness context. In exploring quality, Jarg BERGOLD and Stefan THOMAS (2012) suggest that discussions of quality will be addressed differently by diverse groups and thus it is pertinent to examine the discursive contexts that shape research-practitioners perceptions' of good participatory practice. [5]

This exploratory study shares our findings from Alberta, Canada as part of a wider international investigation by the International Collaboration for Participatory Health Research (ICPHR), which aims to capture international variation and patterns on the conceptualization of the quality in participatory health research (PHR), or PR in a health and wellness context. The ICPHR is focused on systematically bringing together the knowledge and experience of PHR from around the world to enhance the quality and credibility of this approach, and the subsequent impact on policy and practice. For this article, we use the term participatory health research (PHR), popularized by the ICPHR, to encompass the various approaches that fall under the umbrella of participatory research (e.g., participatory action research, participatory research, action research, community-based participatory research) specifically within a health and wellness context. [6]

In the subsequent sections, we describe our exploration of quality in PHR within an Alberta context. Using phenomenography, we present aspects that characterize PHR based on an analysis of the practices of academic researchers. In doing so, we present strategies to measure quality of PHR and subsequently discuss the complexity of defining quality. In particular, we discuss how indicators of quality in PHR can be similar and dissimilar to standards of quality that are established within qualitative research. Further, we consider how standards of quality can be shaped by broader discursive contexts (e.g., institutional contexts). In the end, we offer recommendations on how to assess quality within PHR. [7]

Phenomenography originated as an empirical approach in educational research. However, researchers have applied the approach to a variety of health related fields, such as nursing and health care (BARNARD, McCOSKER & GERBER, 1999; STENFORS-HAYES, HULT & DAHLGREN, 2013). Phenomenography aims to investigate "the qualitatively different ways in which people experience or think about various phenomena" (MARTON, 1986, p.31). Key to phenomenography is recognizing that it aims to understand the world not as it is, but how people conceptualize it (MARTON, 1986). Conceptions form the basic unit of analysis in phenomenography. According to Ference MARTON, a careful account of such conceptions, in turn, can help to facilitate the transition from one way of thinking to qualitatively better conceptions of reality (p.33). Categories of description are the primary outcome of phenomenography, representing whole conceptions and the qualitatively different ways that a phenomenon is understood and experienced (BARNARD et al., 1999; MARTON, 1986). In addition to understanding the different ways a phenomena is understood, phenomenography also seeks to explore how understandings are related structurally (STENFORS-HAYES et al., 2013). This is commonly represented in the form of an outcome space, which presents the logical relationship between categories of description (BARNARD et al., 1999; STENFORS-HAYES et al., 2013). [8]

To explore quality within PHR, the experiential practice of PHR must also be explored. The rationale for this is that a sole focus on the PHR literature base may have led to a situation whereby "[m]ost of the story is missing" (TRICKETT, TRIMBLE & ALLEN, 2014, p.180). In other words, it is essential to determine if what is presented in the literature is reflective of how PHR is practiced. PHR research designs "do not easily fit the language or procedures of traditional social science research" (p.366), and are compounded further by the "typical constraints on how such research can be legitimized through the research criteria imposed by scholarly journals" (ibid.). Accordingly, we chose to use phenomenography because this approach is rooted in the rich experience of the practitioner (BARNARD et al., 1999). In particular, we chose to examine the attitudes of practitioners practicing PHR in order to delineate their conceptions of PHR. This is in line with Andrea CORNWALL and Rachel JEWKES (1995) who propound that a key element of participatory research is the attitude of the researcher. [9]

2.1 Participants and recruitment

Prior to recruitment, we obtained ethical approval for the study from Research Ethics Board 1 at the University of Alberta. Purposeful sampling of participants that have experience with the phenomena being explored is commonly used in phenomenography (YATES, PARTRIDGE & BRUCE, 2012). We identified potential participants involved in PHR within a research or practice capacity (i.e., those who do research within a university or community-based setting, respectively). Our resulting list of research-practitioners were obtained by reviewing relevant PAR literature and/or membership in a provincial participatory research network. We contacted authors identified through the literature if they were working in Alberta and had published at least two articles using PHR approaches from 2007 onwards. Additional participants were added if they were currently or recently practicing PHR for approximately five years or more and resided in the province of Alberta. [10]

Participants were sent a recruitment letter via e-mail, followed by a detailed information letter outlining the study background and procedure. In total, 13 research-practitioners from across Alberta were recruited to the study. Keith TRIGWELL (2000) and John BOWDEN (2005) advise that variation among participants and manageability of the resulting data should influence sample size (YATES et al., 2012). Our sample size is consistent with other studies given the geographic boundaries of inquiry (e.g., EBENEZER & ERICKSON, 1996; TAN, METSALA & HANNULA, 2014). In terms of variation, all participants were women and primarily academic researchers. In future iterations, a more diverse range of research-practitioners is recommended, both in terms of demographics and communities of practice, including the voice of community members. [11]

We used the story dialogue method developed by Ronald LABONTE, Joan FEATHER and Marcia HILLS (1999) to inform the development of the semi-structured interview guide. The story dialogue method was a useful framework to guide interviews because it helped achieve a rich understanding of PHR and participants' conceptualization of quality rooted in their experiences, a key goal of phenomenography (MARTON, 1986). [12]

Semi-structured interviews were conducted in person, when possible, as well as over the phone. On average, interviews lasted approximately one hour. The goal of the interview was to understand how participatory researchers and practitioners in Alberta conceptualize participatory approaches specifically in a health and wellness context. Participants were encouraged to describe their experiences using the specific approach they practice. This open-ended strategy was our attempt to acknowledge the wide diversity of participatory research traditions in which participants engaged. [13]

After each interview, the research assistant conducting the interviews wrote a detailed field note to reflect on the interview, record ideas brought up, and track potential issues with the interview guide. Development of field notes and reviewing of data helped to inform future interviews. [14]

We analyzed the data using six steps originally developed by Lars-Ove DAHLGREN and Margareta FALLSBERG (1991) and adapted by Björn SJÖSTRÖM and Lars Owe DAHLGREN (2002). These steps include familiarization, compilation, condensation, comparison, naming, and contrastive comparison. Consistent with the phenomenographic approach (ibid.), analysis involved 1. reading through the transcripts, 2. grouping content into overall themes, 3. reducing themes into statements that represent the central parts of dialogue, 4. grouping statements into categories based on similarities and differences, 5. naming categories, and 6. comparing them to understand their unique characteristics and overall relationship to one another. After Step 3, we sent study participants a compilation of responses to ensure participants were in agreement with the initial compilation of themes and to provide an opportunity to modify responses. Only four participants responded to this feedback stage and all were in general agreement. [15]

Fifteen categories of description were identified, which represent the qualitatively different ways that the quality in PHR is understood. [16]

3.1.1 Category 1: Participatory

Participants collectively described their experiences of PHR as an approach that seeks to achieve meaningful participation, where non-academic and community members are given opportunities to engage in the research, make decisions and perform leadership roles. They also noted that participation should "ideally be in all phases of [the] research" (002)1). Considering this, an important role for researchers was to engage the community in dialogue regarding how to maximize participation and how to address barriers to engagement. [17]

Participants viewed participation as a foundational component of PHR. However, they also recognized that there were challenges pertaining to the achievement of meaningful participation. For example, there was recognition that everyone in the participatory story is busy and that community members have competing priorities that might limit their participation. Considering this, participants recognized that it was okay for PHR projects to have different levels of participation. They also stressed the need to provide community members with opportunities to choose their level of engagement, as well as to respect community members' time and what they were able to offer. For example, one participant commented that "there's other things going on in their lives ... Even if they think something's important, they might just not have the resources to be able to participate" (004). [18]

Participants further emphasized PHR as a relational process. Throughout interviews, participants referred to relationship building as a highlight of their involvement with PHR and a key indicator of quality in PHR. For some participants, this involved "taking time ... to get to know each other as individuals, not just in the official roles" (008). Relationship building, in turn, was seen as helping to accomplish a number of goals, such as building trust, overcoming frustrations, facilitating collaboration and facilitating long term engagement. In addition, participants related the benefits of long term or sustained engagement as an opportunity to address challenging issues:

"if [community members] didn't have a belief that by working together we could make things better, I think that they would not continue to spend so much time and energy in coming together several times a year for several hours, reading emails, planning meetings" (009). [19]

Although participants highlighted the importance of relationships, some participants recognized that relationships have boundaries and "there [has] to be understanding about where the relationship begins and ends" (003). [20]

Participants described ethical considerations as an important component of PHR. During interviews, participants seemed to discuss ethics in two ways. First, a number of participants viewed PHR as an approach or framework for conducting research in an ethical way. For example, one participant described participatory research as challenging the "long history of [certain communities] being research subjects, and not having any control over how they're written about or how data's used" (009). Second, participants described ethics in terms of conducting ethical research. From this perspective, the concept of "do no harm" was viewed as a foundational principle for guiding research (001). [21]

3.1.4 Category 4: Community oriented

Participants characterized PHR as community oriented, highlighting the importance of research being community driven, as well as the researcher being committed to the community and embedded in the community context. [22]

Community-driven research was described as the community playing an active role in all stages of the research, from development of the research question to the dissemination of findings. In particular, a number of participants saw community involvement in the development of the research question as an integral part of generating outcomes relevant to the community. With that said, participants also recognized that community driven research was not always possible at all stages of the research given constraints on PHR, such as funding:

"The ideal is always that the issues and the questions are community driven. But as academics, and if not an academic, as somebody who has access to funds or resources other than funding ... Sometimes the broad theme or the bigger question is not as community driven as you would like" (010). [23]

Participants also described the need for researchers to be committed to the community. This was highlighted when one participant stated that researchers should have an "explicit commitment to the values and goals" of the community in recognition of the fact that "the systems can work against the trust of certain communities" (002). Further, other participants discussed this commitment in terms of being in service to the community, taking the extra steps necessary to ensure research and project outcomes that are meaningful to the community and focusing on community strengths. [24]

In addition, participants highlighted the importance of the researcher being embedded in the context of the community. For participants, this meant different things, such as getting to know the specific context of the community, engaging informally with community members and attending community events. Participants saw this as contributing to a variety of goals and desired outcomes, such as helping to plan for the future, achieving overall understanding and building and maintaining relationships. For example, one participant mentioned that "researchers really need to be involved in community, know what's going on in the community to be able to be aware of those things that are up and coming so that you can start planning for the future" (005). From this perspective, one way to gauge the quality may be to ask the community to reflect on their experience. For example, one participant stated that you could determine if community members thought the project was a worthwhile process by asking them: "Would you do a community based or PAR project again? ... Would you do it with the other partner again? ... How did your organization benefit from doing this project?" (007) [25]

3.1.5 Category 5: Power shifting

Participants described PHR as involving power shifting. Within this category, aspects related to power shifting include a critical lens on power, the co-creation of knowledge and consciousness raising. Participants discussed the importance of incorporating a critical lens on power by considering power dynamics at play in the project, reducing power differentials between different partners involved and creating opportunities for power shifting to take place. Practically, participants spoke of "power shifting" in terms of how the research question is identified and in ensuring equity among team members by building capacity to support participation for example. With that said, there was also recognition that doing so could be challenging. For example, one participant commented that successfully negotiating power differentials ultimately "depends on who the players are" and "whether they're willing to relinquish that power" (001). [26]

In addition, participants emphasized the importance of co-creating knowledge and privileging diverse voices and skills throughout the research process as one way to counteract power differentials. For example, they recognized the importance of creating knowledge that is "socially constructed by the diversity of expertise and experiences of the partners involved" (008). Tied to this, participants highlighted the need to integrate different forms of knowledge, skills and voices into all phases of the research process. This was highlighted by the following participant when discussing the essence of a participatory approach:

"Not just bringing together people who have very diverse perspectives and strengths, but privileging that diversity through all phases. So there are some stages in a project where the most important voice at the table, in the meeting, in the process, is a community voice ... There are other times where, when we have to write like a budget for what this might look like, and what it might cost, there is a different expertise that needs to be privileged and brought in front" (010). [27]

Last, participants described PHR as a consciousness raising experience, whereby the process of participating helps participants realize their own capabilities so that they could come to "see that they have the power to do something about their situation" (004). [28]

3.1.6 Category 6: PHR involves capacity building and co-learning

Participants experienced PHR as a process involving capacity building and co-learning. During interviews, participants provided a number of different ways in which this could take place. Examples include personal growth, developing new skills, transferring skills within the group, increasing critical awareness, shifting assumptions, and helping to increase a community's ability to advocate for change and speak on its own behalf, linking to project sustainability.

"If we need facilitators, we will employ the facilitators, but also, set an expectation that those facilitators then will be left as trained people in your community for employment. So trying to set up when we're gone, the most sustainable approach to the program that we can" (010). [29]

Furthermore, for many participants, capacity building was something that should take place among everyone involved in the project, including community members and academics. [30]

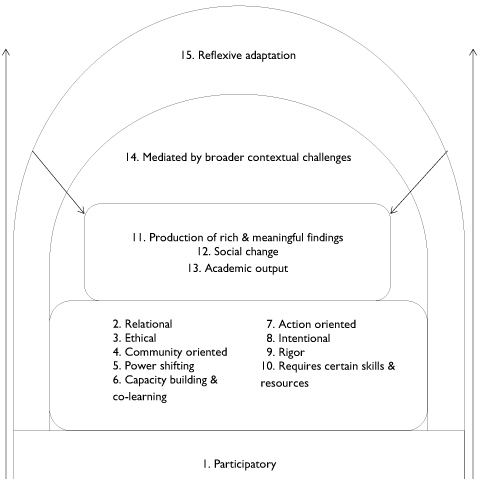

3.1.7 Category 7: PHR is action oriented

Many participants conceptualized action as an important component of PHR. Participants described the importance of engaging in action to reduce structural inequities and address the root determinants of health as opposed to focusing on individual behavior change. Participants also highlighted the importance of involving the community in identifying actions that they would benefit from. This is described in the following excerpt:

"Not changing the individual so that they can cope with the problem, but changing the actual source of the problem, is always ... an issue. And ... you need to engage people in that, because you can't just come out with this pro forma solution and impose it on a group of people, if you don't understand their experience" (006). [31]

However, a few stakeholders raised questions about action as an explicit goal of PHR considering action at broader levels could not always be guaranteed. This is described in the following excerpt:

"Well most of my research ... there's a hope that there's going to be action come out of it and that's why it's essential to have community groups participate ... sometimes I'm looking at policy changes and you're trying to influence policy changes, but there's no guarantee that some organizations are going to change their policies" (007). [32]

3.1.8 Category 8: PHR is intentional

Participants highlighted PHR as an intentional process. This involved paying attention to how "partners are coming together," "assessing participation and collaboration ... through all stages of the research" and being "open, honest, and transparent" while doing so (010). It also meant articulating research roles and maintaining open lines of communication. Moreover, researchers talked about the need to discuss ownership of data and authorship details early on in a project given challenges that could arise regarding data management, such as questions over who owns the data, negotiating representations of data, and navigating uses of publication of data inside the community. [33]

Related to intentionality, a number of participants felt that establishing a memorandum of understanding (MoU) was useful for addressing "some of the issues that might arise" (007) and developing a plan for managing and navigating conflict. Nevertheless, one stakeholder suggested that the need for an MoU depended on the type of community you were working with (formal or informal, structured or unstructured) and that such agreements do not work for all communities (002). [34]

During interviews, participants identified scientific rigor as another aspect of PHR. Participants indicated that although a PHR approach comes with its own set of principles and practices, it was still important for research to be scientifically rigorous. Attached to this, academic researchers were viewed as having the responsibility of ensuring scientific rigor and following guidelines for rigor based on the research methods employed within a study. [35]

3.1.10 Category 10: Requires certain skills and resources

Participants described PHR as requiring certain skills and resources. For example, participants emphasized the importance of possessing participatory qualities, such as listening and communication skills, humility, going into the community with the mindset of a learner, active engagement, and cross-cultural skills. In addition, participants discussed the importance of understanding principles related to community development and being able to tailor their methods and strategies to different community contexts. [36]

Participants also described the importance of self-awareness and reflection throughout all stages of the research process. Such reflection might involve considering whether you are ready to "be participatory" at the beginning of a project (001), capturing your "own biases, and assumptions" (004), and considering "am I doing more harm than good?" (010). Indeed, among some participants, there seemed to be a sense that some people "are inherently participatory" (001), whereas others are not. Last, participants highlighted the need for open mindedness and flexibility to adapt to new contexts and new ways of working. [37]

In terms of resources, participants underscored the importance of having adequate resources to conduct PHR. For instance, participants highlighted the need for funding to be adequate and flexible enough to allow for enough time to be spent in the community and to involve the community in all stages of the research. A number of participants also stressed the need for appropriate human resources. For example, one participant discussed the importance of having a research coordinator who "knows all the players, wherever they come from ... they're the person who never gives up" (003). [38]

3.1.11 Category 11: Production of rich and meaningful findings

Participants described PHR as having the potential to produce rich and meaningful data. As one participant stated, when using a PHR approach, participants might have "less reticence to participate and tell their full story, because the trust is greater than if it's just ... an academic exercise and you don't have the relationships" (007). The same participant also went on to say that "community participants can often provide clarification when you're doing analysis and interpretation that is insightful and rich, that you might not have as a non-practitioner or as a researcher" (007). Along these lines, when PHR was done well, it was seen as creating an "intensity of reflection and connection with the topic that allows for ... deeper understandings to emerge" (011). Such collaboration, in turn, also helped to produce more meaningful data. As one participant stated,

"I think that the whole research process itself, when it's led by people who aren't part of that context, can tell and uncover a very different story ... by default I want everything to be participatory ... that's just my personal value ... I think it leads to better answers" (002). [39]

3.1.12 Category 12: Social change

For participants, addressing health issues and achieving social change was an important outcome of PHR. For the most part, it was ideal if such changes moved beyond individual behavior change to influence broader levels, such as the community, institutional or policy level. Indeed, for a number of participants, seeing actual social change result from a project was a highlight of their PHR experience. For example, one participant recalled working with a low income population to successfully lobby the government around policy change. [40]

However, participants recognized that achieving change at broader levels takes significant time and resources, and that the ability to actually affect such change "[m]ight be variable" given the specific project context (004). Given difficulties associated with broader action and social change, there was an understanding that "small things can be a success" (003). For participants, examples of these small changes included changes in organizational dynamics, capacity building and personal growth. [41]

3.1.13 Category 13: Academic output

During interviews, participants also spoke of academic output as an outcome of PHR. Even though researchers often described community related impacts as a highlight of PHR, they also mentioned the need for academic related outcomes, such as publishing in academic journals, particularly given the university context in which many PHR projects are embedded. This dynamic is captured in the following excerpt:

"Publishing in a journal ... which, we certainly want to do. We want to – to you know, impact the academic world as well as the policy and practice world, but in publishing in a journal would not have had the same impact as the community participation" (007). [42]

Tied to a recognition of the need for academic output was an acknowledgment that community members should have the opportunity to be coauthors if they wish to be and that findings should be disseminated in ways that are relevant to all partners, not just academics. [43]

3.1.14 Category 14: PHR is mediated by broader contextual challenges

Participants described wider contextual factors that posed challenges to participatory projects, such as funding constraints, institutional dynamics, wider societal values and time. [44]

First, participants discussed a number of issues related to funding constraints that challenged the quality practiced in PHR. For instance, a number of participants stated that PHR projects are not funded richly; "there is not a whole appreciation for community research, so you don't really get a lot of funding" (001). [45]

Participants also outlined constraints placed on research by funding sources. Although a few participants seemed to have access to more flexible funding structures, others described funding sources and the grant cycle as dictating the research question and length of time researchers had to accomplish tasks. Participants also recognized that grant cycles did not provide a realistic amount of time for relationship building, which meant that such work often happened outside of the grant funding cycle. [46]

For many participants, funding issues, such as those described above, had a significant influence on the quality of PHR projects. For example, participants described difficulties with relationship development, involving community members in all stages of the research, hiring necessary project staff, engaging community members in the dissemination of findings and evaluating project impact. As one participant stated: "My approach is really to let the community drive the question ... but I'm also very cognizant of the fact that I'm going in with something that's been imposed by a funding source, at the same time" (010). [47]

Second, participants described institutional dynamics at the university level that pose a challenge to PHR. For example, participants felt that aspects of the university ethics process were problematic. The process was described as time consuming, which, when paired with the length of time to get funding, made it difficult to "jump on those really great opportunities that communities bring forth" (005). Participants also mentioned tensions between ethical requirements and community interpretations of research and frustration over the need to overlay PHR with more traditional forms of research to make it amenable to ethics committees. [48]

Further related to institutional challenges, a few participants felt that university bureaucracy and institutional requirements posed a challenge to the PHR process. In addition, some participants felt that the nature of PHR made academic reward and evaluation difficult. As one participant explained, "if you try going forward for tenure, and you haven't done mixed methods, and you're in a faculty that values that type of method, it's very hard" (003). [49]

Third, participants described broader societal challenges that permeated through their work at the university. For example, one participant felt that our society lacked awareness of the value of "different kinds of knowledge, and what that could contribute" (004). Another described society's consumerist and managerial approach as posing a challenge to the practice of PAR in an academic setting:

"It's very challenging because academia ... it's [a] mode which is – it is a competitive and hierarchical kind of a structured system. And [PHR] is asking academics to move from that competitive hierarchical expert model ... to a shared democratic model where there are many experts involved ... not just from academia" (008). [50]

Last, participants experienced challenges related to time. There was acknowledgment that PHR projects take a significant amount of time and that recognition of the actual time needed to devote to PHR was lacking among key actors, like funding bodies. One stakeholder elaborates: "it takes a long time to do well, and I don't think, despite our pleas as community based researchers, research agencies really take us seriously that we need money in place to build relationships" (009). In addition, participants recognized that the desired outcomes of PHR, such as wider social change, takes time and cannot always be realized within the span of a three year project. One participant, for example, discussed how their partnership was only beginning to see change after more than a decade. [51]

3.1.15 Category 15: Reflexive adaptation

Participants conceptualized PHR as requiring a level of flexibility in approach. For example, one participant recognized that "because of other obligations" it is not always possible for community members to "participate in a way that would be pure [community based participatory research] ... and if we do our best that's okay" (009). Additionally, one participant who described practicing PHR in challenging circumstances suggested that there were benefits to being "PARish [sic]," "particularly if you can't mount a project that is true to the principles of PAR throughout the whole process" (011). In response, however, another participant felt that this was only the case "if the power dynamics in a group are addressed and all ... the players are willing to participate" (012). [52]

For these participants, this flexibility or adaptability seemed to be derived from their experience engaging in PHR. It also seemed to require a level of reflexivity to ensure community needs are met and that outcomes are meaningful to the community. [53]

Overall, some participants seemed to adopt a realistic or pragmatic approach to PHR, focusing less on practicing PHR in a textbook fashion and more on providing community members with opportunities to participate and ensuring that outcomes meet the needs of the community. As one participant explained, "I don't get hung up on the process being so pure as much as the outcomes truly serving the community that they were meant to serve" (006). Nevertheless, there was an indication that there were limits to this flexibility for some participants. For example, one participant described leaving a partnership that did not reflect the elements of PHR, stating that it was a "pretty grounding experience ... realizing okay it may not work every time (008)." [54]

The outcome space, is a diagrammatic representation of the relationships between the categories of description (BARNARD et al., 1999). In this study, the outcome space describes participants' understanding of PHR and its quality within a community-university setting. According to Alan BARNARD and colleagues, the outcome space includes both referential and structural aspects, which articulate the "what" and "how" of understanding and experience. The referential aspect represents different insight into PHR and its quality, the foundation of which is the experience of PHR as a participatory process (ibid.).

Figure 1: Outcome space [55]

The structural aspect describes how conceptions are related (ibid.). In this study, we found that the categories of description were structurally related, building on each other and interrelating to form a whole. As depicted in Figure 1, we placed Category 1, "participatory," as the foundation of the outcome space. This is because participants conceptualized participation as a core component of PHR, which weaved throughout the categories. Categories 2 to 10 expand on participation to outline key components and goals of PHR. Categories 11 to 13 expand on this to highlight outcomes of the quality practiced in PHR. [56]

We placed categories 14 and 15 at higher levels because they represented increased awareness related to the practice of PHR, derived through experience engaging in participatory approaches within a community-university setting. Category 14 presents wider contextual challenges that mediate categories 1 to 13. Category 15, in turn, builds on participants' understanding of PHR and can be seen as influenced by the sum of the previous categories. [57]

In their paper on developing quality criteria for PHR, Jane SPRINGETT et al. (2011) argued that PHR is not a method but rather an approach to research which used eclectic methods. They suggested any framework for quality should consider certain key elements. These included the underlying epistemology and ontology: knowledge is co-constructed relationally and through dialogue, ensuring research is with not on and has an impact beyond the production of academic knowledge. Other elements included the primacy of local context, reflexivity and expanded notions of validity and credibility as well as the relational skills of the researcher, particularly in terms of understanding power dynamics and facilitation. One approach to understand how quality is practiced is to reflect on the experiences of PHR and ascertain whether practices adhere to the core values and principles of which participation is at the center. However, to continually improve a field, ongoing reflection on conceptualizations of quality is needed and as such, reflexive techniques remain instrumental in improving methodology (COOKE & KOTHARI, 2001). As Martyn HAMMERSLEY (2007) asserts, reflection on previous judgments of guidelines on quality enable researchers to learn from their own and others' experiences. David BOUD, Rosemary KEOGH, and David WALKER (1985) add that this type of reflection can transform into future possibilities for action. Research as a participatory practice will always be constrained by institutional context. Indeed, Robert CHAMBERS (1998) has argued that a repeated experience in action research in general has been the tension between top down bureaucratic standardization, simplification and control, and the complexity of a local context where local discretion is paramount. In this particular study that context is academic and Canadian, that is, framed by the funding and academic requirements of Canadian universities. [58]

In our study, we found different categories of description that collectively represent participants' conceptions of their experience in practicing PHR. In total, thirteen out of the fifteen categories of description align with the quality guidelines developed by Lawrence GREEN et al. (1995, revised by MERCER et al., 2008), and the principles, facilitators and barriers identified by Barbara ISRAEL et al. (1998). These categories are participatory, relational, community oriented, power shifting, capacity building and co-learning, intentional, rigorous, requiring certain skills and resources, action oriented, leading to social change, production of rich and meaningful data, mediated by wider contextual challenges, and reflexive adaptation. This consistency strengthens the reliability of our findings and bodes well for the development of PHR quality guidelines. Our findings suggest that amongst participatory health researchers within the academic community in Alberta, there is a high level of consistency in their collective understanding of their own practice of PHR. Accordingly, such categories of description have practical implications in guiding a variety of stakeholders in their conceptions of PHR. For instance, these categories of description can provide guidance to help navigate graduate and postdoctoral students who wish to do a PHR project. As well, they may be used as a resource for potential community individuals and partners to inform their expectations of being involved in a PHR project. [59]

Some of the categories seem hardly distinguishable from those you would find in good quality qualitative research, such as rigor, for instance. Other categories of description in our study that were less explicitly highlighted in previous criteria of the quality in PR include "ethical" and "academic output." Even though these were not as prominently discussed as others, participants discussed the ethical components of PHR as a means to challenge the perspective of "research on" versus "research with," as well as an approach to research guided strongly by the concept of "do no harm." This confirms the role of principles and the location of power as important in defining quality in PHR (CORNWALL & JEWKES, 1995; SPRINGETT et al., 2011). It again underpins what distinguishes PHR from qualitative health research are its specific relational ethical principles that in turn flow from its primary epistemological and ontological perspective (SPRINGETT et al., 2011). Social justice is seen as central to those ethics, especially by those who see PHR having potential for transformational change. By contrast the category "academic output" highlighted as important in PHR in our study, suggests a more pragmatic approach driven by self-preservation within the system. Anders JOHANSSON and Erik LINDHULT (2008) distinguish between two types of action research pragmatic or workable and critical. They argue that the two orientations suit different research contexts and cannot easily be combined. The pragmatic orientation is well suited for contexts where concerted and immediate action is needed, whereas the critical is preferable where transformative action needs to be preceded by critical thinking and reflection. In the former, power to act is a desired outcome, and in the latter, unequal and invisible power relations need to be unveiled before they can be transformed. They further argue that is the responsibility of the researcher to decide which is appropriate for the context. [60]

The origin of the majority of participants in our study were from academic settings where performance criteria and research impact still remains framed in terms of publications. Although previous quality criteria discuss dissemination of findings (e.g., MOORE 2004), participants in our study linked dissemination of findings with the need for academic related outcomes, such as publishing in journals. Participants did acknowledge that community members should have the opportunity to be coauthors if they wish. Whereas current PR guidelines emphasize that the dissemination process must be mutually beneficial (see ISRAEL et al., 2008, or MERCER et al., 2008) through an ongoing negotiation process between the researcher and the community of interest, current guidelines (ibid.) have neither specified types of output nor illuminated the value of each output for the researcher or community of interest. Given potential job pressures, academic-practitioners may strive towards developing outputs that meet both academic and community needs. Unfortunately, present literature illuminates that this task may be challenging to address. For instance, in her reflection about a study that focused on increasing access to services for Aboriginal people who suffered from AIDS, hepatitis C or substance abuse, Jennifer MULLETT (2015) highlights that the team chose to disseminate knowledge to the Aboriginal community through a booklet as her team recognized that the production of funding reports do not carry a lot of value for the Aboriginal communities. [61]

Given these tensions between pragmatic and transformational, it remains important to determine if the "ethical" and "academic output" categories of description remain consistent across geographical and cultural contexts and types of researchers (academic, practice, or community) and if the weight given to the different categories over all reflect local negotiation of those tensions. Future studies incorporating a diverse group of stakeholders can explore these tensions and further contribute to conceptualizations of the quality in PHR. Further, similar studies implemented in international contexts are necessary to shed light on similarities and differences and thus contribute to the development of international standards for PHR. Experiences of participatory action research in non health contexts might also reveal some insights (SPRINGETT, forthcoming). [62]

As participatory research in a health and wellness context continues to grow in popularity, there is a need to explore the key components that contribute to the quality of research and practice in this field to ensure continued clarity concerning the key features of the science and the approach. In our study, we explored research-practitioners' conceptions of PHR and compared these conceptions to current PR guidelines identified within the health literature. Exploring which aspects of researcher-practitioners collective experience are and are not reflected in current guidelines could inform future guidelines and potentially invite new areas (e.g., indices of quality) that require further exploration both in terms of research and practice. The results of our present study indicate that the majority of PHR conceptions identified are reflective of current North American PR guidelines: suggesting that conceptions may potentially remain consistent over time within the context of Alberta, Canada. Further, discussions with participants in our study revealed both ethical and academic output conceptions of PHR that have not been so explicitly highlighted in previous literature. [63]

In relation to participatory action research, Yoland WADSWORTH (1998, p.7) writes that although there are conceptual differences between participation, action and research, "in its most developed state these differences begin to dissolve in practice." The same can be said for any exploration of the quality in PHR when trying to delineate its essential components. Future studies will explore how research-practitioners conceptualize PHR in other settings within North America and internationally to compare similarities and differences on an international scale. Mapping out these conceptions across contexts can then contribute to the development of an international set of criteria that can strengthen the scientific rigor and acceptability of participatory research in a health and wellness context. [64]

1) The number refers to the respective participant, in this case Participant #2. <back>

Barnard, Alan; McCosker, Heather & Gerber, Rob (1999). Phenomenography: A qualitative research approach for exploring understanding in health care. Qualitative Health Research, 9(2), 212-226.

Barreteau, Olivier; Bots, Pieter W.G. & Daniell, Katherine A. (2010). A framework for clarifying participation in participatory research to prevent its rejection for the wrong reasons. Ecology and Society, 15(2), Art. 1, http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol15/iss2/art1/ [Accessed: July 1, 2015].

Bergman, Manfred Max & Coxon, Anthony P.M. (2005). The quality in qualitative methods. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 6(2), Art. 34, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs0502344 [Accessed: August 24, 2015].

Bergold, Jarg & Thomas, Stefan (2012). Participatory research methods: A methodological approach in motion. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 13(1), Art. 30, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs1201302 [Accessed: August 24, 2015].

Boud, David; Keogh, Rosemary & Walker, David (1985). Reflection: Turning experiences into learning. London: Kogan Page.

Bowden, John A. (2005). Reflections on the phenomenographic team research process. In John A. Bowden & Pam Green (Eds.), Doing developmental phenomenography (pp.11-31). Melbourne: RMIT University Press.

Cargo, Margaret & Mercer, Shawna L. (2008). The value and challenges of participatory research: Strengthening its practice. Annual Review of Public Health, 29, 325-350.

Chambers, Robert (1998). Beyond whose reality counts? New methods we now need. Studies in Cultures, Organizations and Societies, 4(2), 279-301.

Cooke, Bill & Kothari, Uma (2001). Participation: The new tyranny?. London: Zed Books.

Cornwall, Andrea & Jewkes, Rachel (1995). What is participatory research?. Social Science & Medicine, 41(12), 1667-1676.

Dahlgren, Lars-Ove & Fallsberg, Margareta (1991). Phenomenography as a qualitative approach in social pharmacy research. Journal of Social and Administrative Pharmacy, 8(4), 150-156.

Ebenezer, Jazlin V. & Erickson, Gaalen (1996). Chemistry students' conceptions of solubility: A phenomenography. Science Education, 80(2), 181-201.

Flick, Uwe (2007). Managing quality in qualitative research. London: Sage.

Green, Lawrence W.; George, M. Anne; Daniel, Mark; Frankish, C. James; Herbert, Carol J.; Bowie, William R. & O'Neill, Michael (1995). Study of participatory research in health promotion: Review and recommendations for the development of participatory research in health promotion in Canada. Ottawa: Royal Society of Canada.

Hammersley, Martyn (2007). The issue of quality in qualitative research. International Journal of Research & Method in Education, 30(3), 287-305.

International Collaboration for Participatory Health Research (2013). What is participatory health research?. Position paper 1, http://www.icphr.org/uploads/2/0/3/9/20399575/ichpr_position_paper_1_defintion_-_version_may_2013.pdf [Accessed: August 24, 2015].

Israel, Barbara A; Schulz, Amy J.; Parker, Edith A. & Becker, Adam B. (1998). Review of community-based research: Assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annual Review of Public Health, 19, 173-202.

Johansson, Anders W. & Lindhult, Erik (2008). Emancipation or workability? Critical versus pragmatic scientific orientation in action research. Action Research, 6(1), 95-115

Labonte, Ronald; Feather, Joan & Hills, Marcia (1999). A story/dialogue method for health promotion knowledge development and evaluation. Health Education Research, 14(1), 39-50.

Marton, Ference (1986). Phenomenography—a research approach to investigating different understandings of reality. Journal of Thought, 21(3), 28-49.

Mays, Nicholas & Pope, Catherine (2000). Qualitative research in health care: Assessing quality in qualitative research. British Medical Journal, 320(7226), 50-52.

McGee, Rosemary (2002). Participating in development. In Uma Kothari & Martin Minogue (Eds.), Development theory and practice: Critical perspectives (pp.92-116). Houndmills: Palgrave.

McTaggart, Robin (1991). Principles for participatory action research. Adult Education Quarterly, 41(3), 168-187.

Mercer, Shawna L.; Green, Lawrence W.; Cargo, Margaret; Potter, Margaret A.; Daniel, Mark; Olds, R. Scott & Reed-Gross, Erika (2008). Reliability-tested guidelines for assessing participatory research projects. In Meredith Minkler & Nina Wallerstein (Eds.), Community-based participatory research for health (2nd ed., pp.407-433). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Moore, Janet (2004). Living in the basement of the ivory tower: A graduate student's perspective of participatory action research within academic institutions. Educational Action Research, 12(1), 145-162

Mullett, Jennifer (2015). Issues of equity and empowerment in knowledge democracy: Three community based research examples. Action Research, 13(3), 248-261.

Reason, Peter (2006). Choice and quality in action research practice. Journal of Management Inquiry, 15(2), 187-203.

Reynolds, Joanna; Kizito, James; Ezumah, Nkoli; Mangesho, Peter; Allen, Elizabeth & Chandler, Clare (2011). Quality assurance of qualitative research: A review of the discourse. Health Research Policy and Systems, 9:43, http://health-policy-systems.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1478-4505-9-43 [Accessed: July 1, 2015].

Sjöström, Björn & Dahlgren, Lars-Owe (2002). Applying phenomenography in nursing research. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 40(3), 339-345.

Springett, Jane (Forthcoming). The impact of participatory health research. What can we learn form participatory evaluation? Educational Action Research.

Springett, Jane; Wright, Michael T. & Roche, Brenda (2011). Developing quality criteria for participatory health research. an agenda for action. WZB Discussion Paper SP I 2011-302, Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung, Berlin, Germany.

Stenfors-Hayes, Terese; Hult, Hakan & Dahlgren, Madeleine A. (2013). A phenomenographic approach to research in medical education. Medical Education, 47, 261-270.

Tan, Amil K. J.; Metsala, Eija & Hannula, Leena (2014). Benefits and barriers of clown care: A qualitative phenomenological study of parents with children in clown care services. European Journal of Humour Research, 2(2), 1-10.

Trigwell, Keith (2000). A phenomenographic interview on phenomenography. In John A. Bowden & Eleanor Walsh (Eds.), Phenomenography (pp.63-82): Melbourne: RMIT University Press.

Trickett, Edison J.; Trimble, Joseph E. & Allen, James (2014). Most of the story is missing: Advocating for a more complete intervention story. American Journal of Community Psychology, 54(1-2), 180-186.

Wadsworth, Yoland (1998). What is participatory research?, Action Research International, http://www.aral.com.au/ari/p-ywadsworth98.html [Accessed: August 24, 2015].

Yates, Christine; Partridge, Helen & Bruce, Christine (2012). Exploring information experiences through phenomenography. Library and Information Research, 36(112), 96-119.

Jane SPRINGETT, PhD, MA, is director of the Centre for Health Promotion Studies and professor at the School of Public Health at the University of Alberta in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada.

Contact:

Dr. Jane Springett

Centre for Health Promotion Studies, School of Public Health

University of Alberta

#3-289 11405-87 Ave, Edmonton AB T6G 1C9

Canada

Tel.: +1 780-492-0289

Fax: +1 780-492-0364

E-mail: jane.springett@ualberta.ca

URL: https://uofa.ualberta.ca/public-health/about/faculty-staff/academic-listing/jane-springett

Kayla ATKEY, MSc, is a policy analyst with the Alberta Policy Coalition for Chronic Disease Prevention in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada.

Contact:

Kayla Atkey

Alberta Policy Coalition for Chronic Disease Prevention

#4-343 11405-87 Ave, Edmonton AB T6G 1C9

Canada

Tel.: +1780-492-0493

Fax: +1 780-492-0364

E-mail: atkey@ualberta.ca

Krystyna KONGATS, MPH, is a PhD candidate in the School of Public Health at the University of Alberta in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada.

Contact:

Krystyna Kongats

Centre for Health Promotion Studies, School of Public Health

University of Alberta

#3-035 11405-87 Ave, Edmonton AB T6G 1C9

Canada

Tel.: +1 780-492-9280

Fax: +1 780-492-0364

E-mail: krystyna.kongats@ualberta.ca

Rosslynn ZULLA, MEd, is a PhD candidate in the School of Public Health at the University of Alberta in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada.

Contact:

Rosslynn Zulla

Centre for Health Promotion Studies, School of Public Health

University of Alberta

#3-035 11405-87 Ave, Edmonton AB T6G 1C9

Canada

Tel.: +1 780-492-9280

Fax: +1 780-492-0364

E-mail: rzulla@ualberta.ca

Emma WILKINS, MPH, is a research coordinator with the Centre for Health Promotion Studies, School of Public Health at the University of Alberta in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada.

Contact:

Emma Wilkins

Centre for Health Promotion Studies, School of Public Health

University of Alberta

#3-035 11405-87 Ave, Edmonton AB T6G 1C9

Canada

Tel.: +1 780-492-9279

Fax: +1 780-492-0364

E-mail: emma.wilkins@ualberta.ca

Springett, Jane; Atkey, Kayla; Kongats, Krystyna; Zulla, Rosslynn & Wilkins, Emma (2016). Conceptualizing Quality in Participatory

Health Research: A Phenomenographic Inquiry [64 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 17(2), Art. 27,

http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs1602274.