Volume 18, No. 1, Art. 2 – January 2017

Worth a Thousand Words? Advantages, Challenges and Opportunities in Working with Photovoice as a Qualitative Research Method with Youth and their Families

Roberta L. Woodgate, Melanie Zurba & Pauline Tennent

Abstract: Photovoice, a popular method in qualitative participatory research, involves individuals taking photographic images to document and reflect on issues significant to them. Having emerged in the mid-1990s, its popularity has been related to several advantages of working with the method associated with enhanced forms of expression and accessibility, as well as a strong alignment with participatory research principles. We explore the advantages, challenges and opportunities in working with photovoice in qualitative research through gleaning insights from the literature and from studies that were part of IN•GAUGE®, a research program that has used photovoice and other visual methods for doing research with youth and families for over 15 years. The insights provide guidance for the evolution of photovoice and the development of ethical protocol assessments that are necessary for enhancing the participatory and empowering aspects of photovoice.

Key words: participatory research; photovoice; qualitative research; youths; families; visual methods

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. Photovoice as Tool for Expression and Empowerment in Qualitative Research

3. Procedural, Ethical and Relational Challenges in Working with Photovoice

3.1 Activating and implementing photovoice with research co-researchers

3.2 Authenticity and validity

3.3 Interpretation and dissemination

3.4 Opportunities for the advancement of photovoice as a qualitative participatory methodology

4. Conclusions

Since the mid-1990s, creative participatory approaches in qualitative research have grown in popularity towards facilitating the authentic expression of the complex realities of people engaged through research (FRASER & al SAYAH, 2011; MILLER, 2015; RATHWELL & ARMITAGE, 2016; WANG, 1999; WANG & BURRIS, 1997), as well as the more affective connections between people, their environments, and life situations (POWER, NORMAN & DUPRÉ, 2014; ZURBA & FRIESEN, 2014). Photovoice has become situated among the most common creative participatory approaches in qualitative health research (COOPER & YARBROUGH, 2010; HOGAN et al., 2014; JORGENSON & SULLIVAN, 2010), and has been found to be especially valuable when doing research with youth and families (STRACK, MAGILL & McDONAGH, 2004; WOODGATE & BUSOLO, 2015; WOODGATE & KREKLEWETZ, 2012; WOODGATE & SKARLATO, 2015; WOODGATE, EDWARDS & RIPAT, 2012; WOODGATE, EDWARDS, RIPAT, BORTON & REMPEL, 2015; WOODGATE, EDWARDS, RIPAT, REMPEL & JOHNSON, 2016). This popularity has been related to several advantages of working with the method associated with enhanced forms of expression and accessibility, as well as a strong alignment with participatory research principles (RIPAT & WOODGATE, 2012; WANG, 1999). Given the popularity of using photovoice, its increasing diversity of applications, and some of the questions emerging in research around the representation through the method (EVANS-AGNEW & ROSEMBERG, 2016), we contend that the time is right to conduct an evaluation of photovoice relating to participatory health research. Towards achieving this, our article explores the advantages and challenges of using photovoice in qualitative research by bringing forward examples from the literature and photovoice projects that were part of IN•GAUGE®, an on-going15-year research program developed by Roberta WOODGATE. Through IN•GAUGE®, she contributes to building insights into the health and illness experiences of youth through exploring the multiple perspectives of youth, their families, policy makers, and service providers. The research conducted through IN•GAUGE® is designed to provide critical information for understanding youth‘s perspectives and lived experiences of health and illness (e.g., health promotion, cancer and cancer risk, and chronic physical and mental illness) as well as the perspectives of their families towards developing better policy and services. Co-researchers1) of IN•GAUGE® studies are frequently given options for how they can participate in the research process and often chose to express themselves visually (instead of only verbally through interviews) with regards to their illness/health condition(s) or those of their loved ones. The many insights about photovoice which have been gained through IN•GAUGE® projects are used here towards the consideration of new opportunities for furthering photovoice as a participatory method in qualitative health research with youth and their families. [1]

In the following sections we explore the advantages, challenges and opportunities in working with photovoice in qualitative research through gleaning insights from the literature and from studies that were part of IN•GAUGE®. We begin by highlighting how photovoice has been used as a powerful tool for expression and empowerment for participants engaged through qualitative research. In the following section, we deal with the procedural, ethical and relational challenges in working with photovoice at various stages from activation to interpretation and dissemination. This section also considers some of the issues with photovoice relating to data validity and authenticity. In the final section, before our conclusions, we focus on opportunities for the advancement of photovoice as a qualitative participatory methodology. [2]

2. Photovoice as Tool for Expression and Empowerment in Qualitative Research

Photovoice is a participatory method that involves individuals taking photographic images to document and reflect on issues significant to them and how they view themselves and others (KELLER, FLEURY, PEREZ, AINSWORTH & VAUGHAN, 2008; MITCHELL, 2011; STRACK et al., 2004; WANG & BURRIS, 1997). It is viewed as a useful strategy for prompting dialogue between the interviewee and the co-researcher that may result in thick descriptions in phenomenology (VAN MANEN, 1990). Photovoice has been heralded as an unobtrusive way of entering the worlds of individuals, providing strategies for co-researchers to define the problem of interest, revealing what might be uncomfortable or unknown (JORGENSON & SULLIVAN, 2010; KELLER et al., 2008; PRUS, 1996; SZTO, FURMAN & LANGER, 2005). It was first pioneered in community-based participatory research with marginalized populations in the mid-90s by Caroline WANG and Mary Ann BURRIS (1997; see also FAYVAN, 1995; HOGAN et al., 2014; WANG, 1999). With photovoice, the camera is put in the hands of the co-researcher. Photovoice, therefore, is a significant evolution from "photo elicitation," an approach where the interviewer uses photos as symbolic points of reference to guide the interview (BUCKLEY, 2014). By enabling the co-researcher to produce the images that are the focal point for discussion, the method creates the space for the co-researcher to build the context and provide the setting for research questions (HERGENRATHER, RHODES, COWAN, BARDHOSHI & PULA, 2009; MILLER, 2015). [3]

Participatory visual approaches such as drawing and photography enable the co-researcher to have a conversation with themselves by thinking through how they want to represent their own perspectives and experiences around a given topic (WOODGATE, WEST & TAILOR, 2014). Through participatory visual methods, co-researchers may produce powerful metaphors or literal depictions of their lived realities (KANTROWITZ-GORDON & VANDERMAUSE, 2016). Working with visuals was found to be powerful for youth who participated in several of the IN•GAUGE® studies. For example, the visual representations of experiences provided by co-researchers in the Meaning-Centred Symptom Experiences by Children with Cancer study2) revealed the power of visual media for accessing youth's (8-17 years) conscious and unconscious feelings about difficult life situations, such as illnesses causing pain, sorrow and existential crises (WOODGATE et al., 2014). Using the media platform, youth were able to express themselves through interacting with characters and moving through universes that were designed to help them express the complex emotions that they were experiencing as a result of illness. Another example is an Adolescent Cancer Prevention study where youth (11-19 years) used photovoice to depict their concern, hurt, resentment and detachment with regards to their families' smoking habits, highlighting the connection between smoking habits and interfamily relationship dynamics (WOODGATE & KREKLEWETZ, 2012). [4]

Procedurally, photovoice involves individuals taking photographs and providing captions to those images in order to document and reflect on issues significant to them and how they view themselves and others (SZTO et al., 2005; KELLER et al., 2008). Photovoice interviews and focus groups that are conducted through IN•GAUGE® follow the SHOWeD method. The SHOWeD method is a common set of protocols for photovoice research (CATALINI & MINKLER, 2010), involving leading individuals through a set of interview or focus group questions with the assistance of photos (DAHAN et al., 2007; STRACK et al., 2004). The SHOWeD method consists of five questions: "What do you see here?," "What is really happening here?," "How does this relate to our lives?," "Why does this situation, concern, or strength exist?," and "What can we do about it?" (WANG, CASH & POWERS, 2000, p.84). The questions progressively challenge co-researchers to explore the deeper meanings of the image towards providing insights about the determinants of issues and ways forward for the development of solution and/or interventions (STRACK, et al., 2004; WOODGATE & KREKLEWETZ, 2012; WOODGATE et al., 2015). Another question used at the end of all interviews is "Were there any photos you wish you could have taken?" This gives co-researchers a chance to explore their thoughts and visions about life beyond their realities (e.g., wishing to take a photo of a person that is since passed or another life situation that is impossible). As a research process, photovoice also includes several steps beyond interviewing, including choosing photos for sharing, discussions with stakeholders, presentations and exhibits, and reflections and decisions for next steps (LORENZ, 2010; LORENZ & CHILINGERIAN, 2011). [5]

When participating in photovoice, people take photos for different reasons, including artistic expression (GRAY, de BOEHM, FARNSWORTH & WOLF, 2010), the promotion of social justice (MOLLOY, 2007), the seeking of connection and understanding of lived realities, however diverse (FRISBY, MAGUIRE & REID, 2009), and to express at times complex emotions (WOODGATE et al., 2012, 2015). The photographs constructed by the co-researchers are at times literal representations of their experiences (e.g., receiving treatment) or the objects or places affecting their lives (e.g., a hospital or health clinic). Frequently, however, the images captured by co-researchers are metaphors for their life situations, experiences, and/or emotions. In such cases, the co-researchers' verbal interpretations of the images are particularly important for understanding the meaning(s) of photos, especially when the images are deeply symbolic. Images can also often have and/or can trigger multiple meanings (GENOE & DUPUIS, 2013). The following youth co-researcher explored her reality of living with a bleeding disorder (Von Willebrand's disease) through symbolic representation (Figure 1) and explained that her photo reinforced that there was more to her than her chronic illness and that while the photo made her feel proud and confident, it also evoked feelings of sadness. The youth felt that her participation would contribute to enhancing discussions and hopefully understanding about what it is like to be a youth living with a chronic illness.

Figure 1: I am more than my chronic illness. Photo taken by a female co-researcher (age 26 years) in the Living with and Managing Hemophilia and other Bleeding Disorders study.

"There's more to a person than just their disease, there are passions that you don't see when I'm at worst in the emergency department. Um you know you, obviously you see the worst, you don't see the best, and this is, this is my best, this is my, this is my confidence, this is what I'm confident in, this is what I excel in, this is my happy place. So no one, no one sees that when I'm really sick and that makes me sad because as an artist and as an illustrator you want to share that, you want to show everyone" (Female co-researcher, age 26 years, from the Living with and Managing Hemophilia and other Bleeding Disorders study). [6]

Describing an image can evoke a variety of emotions within co-researchers. Co-researchers involved in research through IN•GAUGE® often commented on the research process and expressed that it afforded them opportunities to explore in ways that they had not been able to previously. One co-researcher expressed this in terms of her enjoyment of the process and how photovoice brought up intense and beneficial thoughts and feelings.

"I just really enjoyed the photovoice. I found it really eye-opening. I didn't think I could you know come up and have so many intense feelings just over pictures, but it does, it made me feel really good. It was a really good way to do some stress relief and self-care" (Female co-researcher, age 30 years, from the Aboriginal Youth Living with HIV study). [7]

Numerous cultures throughout history have acknowledged the healing power of interacting with images (BOYDELL, GLADSTONE, VOLPE, ALLEMANG & STASIULIS, 2012; KREITLER, OPPENHEIM & SEGEV-SHOHAM, 2004; KUNZENDORF, 1991). Co-researchers often expressed that their experience of the photovoice process was therapeutic and that such benefits were facilitated through the less-rigid structure and safe space for expression created by the researcher during the interviews. The therapeutic nature of the method was reflected in the dialogue with a co-researcher from the Living with and Managing Hemophilia and other Bleeding Disorders study who was able to express how his "stuffies" [stuffed animal] made him feel safe when attending hemophilia camp, and when asked how his "stuffies" handle his pokes, he said: "They're stuffies! They always handle their pokes!"

Figure 2: Stuffies. Photo taken by a male co-researcher (age 12 years) in the Living with and Managing Hemophilia and other Bleeding Disorders study.[8]

Another youth co-researcher from the Youth's Voices study expressed that she wished that visual expression was a part of her therapy sessions, and that she felt she could communicate better with the adults in her life (including parents) through and with the assistance of photographs. This enhanced ease of communication that can be attained through producing and engaging with visuals is a common result of working with photovoice (CARLSON, ENGEBRETSON & CHAMBERLAIN, 2006; GENOE & DUPUIS, 2013). Similarly, parents of IN•GAUGE® study co-researchers often echoed the benefits of using photography for promoting reflection and communication. Some parents have stated that photovoice was a way for their children to express themselves without the "clinical labeling" that they felt came along with other types of discussions about their child's illness. Parents also often see the photovoice process as being something that could cultivate creativity and positive interests in their children's lives. [9]

The photovoice results with youth from several of the IN•GAUGE® studies reflected the positivity that parents expected as an outcome. In addition to youth saying that they enjoyed the process and that it provided therapeutic benefit, they also used the process to reflect on the most positive aspects of their lives and things that they were most proud of (e.g., drawings that they had made or symbolic representations of their other achievements, such as school graduation). It was especially important for researchers to keep in mind the participatory quality (i.e., that co-researchers play a role in guiding themes) of the interview when co-researchers presented photographs that seemingly did not fit with the research topic, but instead were a reflection of everyday life or aspects of life that the co-researcher particularly enjoyed. Photos representing the "ordinary" can be overlooked in photovoice interviews over those that depict more dramatic scenes or metaphors that highlight particular points of interest or reflect a sense of "poetry" in the data. Researchers have to keep in mind that photovoice interviews are highly interpretive, that dramatic effect does not necessarily communicate more, and that a photo or series of photos about something seemingly trivial or unrelated to the research topic could in fact provide meaningful data once interpreted by the co-researcher. An example of this is when co-researchers from the First Nations Children with Disabilities study and the Children Living with Complex Care Needs study would take multiple photos of family outings when the broader research questions were about their experiences with an illness. Though the photos did not illustrate the illness in a literal sense, they did provide a powerful platform for talking about the "good days" and "bad days," what was meaningful in life, and the support systems that were important for maintaining well-being. [10]

The data coming through photovoice in qualitative research have the potential to generate information for meaningful changes to systems of care by informing policy-makers of assets and deficits relating to particular issues (STRACK et al., 2004; WANG, 2006). A co-researcher from the Children Living with Complex Care Needs study took a series of photos of the barriers she had to deal with respect to her accessing the washroom in a health care facility where she would go weekly for treatment (e.g., Figure 3). She had terminal cancer and her main focus in her last year of her life was advocating for youth with cancer. Inaccessible buildings were just one of the many issues she would talk about.

Figure 3: Barriers. Photo taken by a female co-researcher (age 16 years) in the Children Living with Complex Care Needs study.

"Each time we get smacked with barriers ... But we were so frustrated, we couldn't believe it, a brand new washroom and they're doing the same things again. Like I don't know where people's brains are" (Youth and mother of youth in the Children Living with Complex Care Needs study). [11]

The insights coming through IN•GAUGE® provide further evidence for the advantages of working with photovoice as a qualitative research method. The insights not only demonstrate that photovoice can be an empowering approach, but that it can also positively impact co-researchers, as well as those who are close to them (i.e., parents and carergivers). Such insights also shed light on the potential for photovoice and other visual approaches to be extended into therapies and other clinical practices that help youth understand and manage suffering and facilitate healing and positive existential development (WOODGATE et al., 2014). If we are to develop photovoice further as an approach in research and within systems of care, it will be important to consider the commonly occurring procedural, ethical and relational challenges that can influence the quality of future photovoice approaches (SCHWARTZ, 2011). The next section presents some of the challenges that emerged in the literature and through IN•GAUGE®. [12]

3. Procedural, Ethical and Relational Challenges in Working with Photovoice

The following sections of our article contribute to understanding the applications of photovoice and provides an evaluation of photovoice as a method employed in health research through exploring the procedural, ethical and relational challenges that have been highlighted in the literature on photovoice, as well as through the experiences through IN•GAUGE®. [13]

3.1 Activating and implementing photovoice with research co-researchers

In activating and implementing qualitative research that uses photovoice, it is important to pay close attention to why and how photovoice is being used, and if photovoice is an appropriate method for the research or for engaging particular co-researchers. When initiating photovoice it is important to consider the lives of the study co-researchers and if taking photos outside of the interview time will be burdensome (ROYCE, PARRA-MEDINA & MESSIAS, 2006; WANG, YI, TAO & CAROVANO, 1998). Several different aspects of photovoice can make the approach prohibitive. Co-researchers may not be familiar with the artistic or technical aspects of photography. Towards overcoming such hurdles, training in the use of equipment and technique should be built into photovoice protocols, often providing co-researchers with enriching and educational experiences (LENETTE & BODDY, 2013). Training is built into IN•GAUGE® research project protocols to make co-researchers feel comfortable with what was being requested of them. This also includes sharing with co-researchers in advance the types of (SHOWeD) questions that would be asked during photovoice interviews. Nonetheless, in IN•GAUGE® studies that have used photovoice, there were some co-researchers who were not comfortable with the process and found that photovoice was difficult to accomplish due to its unfamiliarity, or counter to what they expected from the research process (i.e., even when the process and research questions were shared in advance). The following quote is an example from the Youth's Voices study where a co-researcher (female, age 17 years) explained why she did not want to participate in photovoice because she did not feel familiar with photography and felt that it was not an appropriate way for her to contribute to the study.

Interviewer: "Okay. Um now you mentioned that you do have the camera, correct."

Co-researcher: "Yeah, I already have it."

Interviewer: "But you ..."

Co-researcher: "But I don't want to do the photography thing."

Interviewer: "Okay."

Co-researcher: "I just, I don't know how that contributes, I don't, I don't think it will ‘cause I don't know what I would take pictures of and I don't know why it would be relevant."

Interviewer: "Okay."

Co-researcher: "I'm not much of a photographer (chuckle)." [14]

IN•GAUGE® co-researchers are always given the option to decline the photovoice portion of the interview with other options offered. For example, in the Living with and Managing Hemophilia and other Bleeding Disorders study, there were some younger children who found drawing pictures really helped them to express their feelings, especially depicting a good/bad day. IN•GAUGE® interviewers also noted that the questions from the SHOWeD framework were not always as helpful in cases where co-researchers would take photos of the everyday aspects of their lives. There were instances when co-researchers expressed frustration with SHOWeD, explaining that they could not go into detail due to the nature of the questions which required further or different styles of probing. [15]

Protocols for initiating photovoice should involve co-researchers in determining if photovoice is appropriate and/or desired (MACLEAN & WOODWARD, 2013). Through the collaborative development of protocols, co-researchers can have a say about when, where and how photovoice is conducted. By determining appropriateness in the early stages of research it may also be possible to determine the level of obtrusiveness that might come through working with visual representations of a co-researcher's life. A trial run may be a suitable approach in situations where it is not easily determined if photovoice is appropriate or if it will pose undue challenges that could possibly be remedied at the start of a project (CHONODY, FERMAN, AMITRANI-WELSH & MARTIN, 2012). As is the case with all types of research (visual or non-visual), regardless of the point of entry for co-researchers, it should be made clear that co-researchers need share only what they feel comfortable with. This is especially important when asking questions about those experiences that cause emotional pain and may be very personal (e.g., experiences with illness and treatment). [16]

Important aspects of the photovoice research design include the interview space and the interview procedures, which can determine how safe co-researchers feel to reflect and express their perspectives (MANNAY, 2010). For IN•GAUGE® studies, less formal spaces (e.g., a co-researcher's home) tended to be more effective for creating relaxed and comfortable settings for co-researchers than did formal spaces (e.g., hospitals or clinics). The way in which questions were designed and how researchers reacted to co-researcher responses were also important for promoting an environment where co-researchers felt safe to reflect deeply and respond authentically. It is important that interviewers not privilege their own voice over their co-researchers' or impose their own interpretations of metaphors symbolic language (BUETOW, 2013). Furthermore, being open and non-judgmental, and not asking overly personal questions or limiting responses can be critical for supporting open and authentic responses (SOPACK, MAYAN & SKRYPNEK, 2015). The next section explores question(s) around authenticity and validity of photovoice in greater detail. [17]

Authenticity and validity are issues with all research (i.e., qualitative and quantitative). With respect to qualitative research, WHITTEMORE, CHASE and MANDLE (2001) contend that distinctions in validity criteria need to be made "with credibility, authenticity, criticality, and integrity identified as primary validity criteria and explicitness, vividness, creativity, thoroughness, congruence, and sensitivity identified as secondary validity criteria" (p.522). Criteria such as explicitness, vividness and creativity can be influenced by social pressure that can be experienced by co-researchers during an interview, especially where there are creative elements (e.g., photography) that are meant to promote transformative outcomes such as changes to health policy (RYDZIK, PRITCHARD, MORGAN & SEDGLEY, 2013). Over the years, Roberta WOODGATE has found that the experience of social pressure to produce something meaningful and impactful is especially strong in qualitative health research because co-researchers often see their participation in studies as a way to help others who are experiencing similar challenges. Social pressure was also reflected when IN•GAUGE® co-researchers would sometimes say that they "were not photographers" or when co-researchers would describe their photos as "not very good." The desire to create something beautiful or powerful was a strong factor for some of the IN•GAUGE® co-researchers, particularly those who had an appreciation for photography or the arts in general. During several interviews, it became obvious that co-researchers were also clearly aiming to meet the expectations of the researchers instead of using photovoice to explore their own personal interpretations. This was particularly detectable during the Youth Health Promotion study. During the photovoice interviews many youth took photographs of fruits and vegetables "because they are healthy" (WOODGATE & LEACH, 2010; WOODGATE & ZURBA, under review). Photos of foods that are commonly known as being "healthy" and photos portraying exercise did not come with rich descriptions of meanings relating to health, as did other photos that had more personal and symbolic meanings. Youth's photos from the Youth Health Promotion study that were accompanied by the most authentic and enthusiastic responses were those representing their experiences with friends, community, and especially with "being outside" in the environment (WOODGATE & SKARLATO, 2015). This difference in the amount of expression between what might be expected and the unexpected illuminates how enthusiasm within responses can enhance the secondary validity of the data (WHITTEMORE et al., 2001). [18]

Parameters for participation are important to consider when designing photovoice protocols. Limitations such as not permitting the inclusion of older photos or photos found on the Internet are common research protocols with photovoice. Such protocols are meant to encourage co-researchers to compose their own images, but often lead to dissatisfaction due to not being allowed to use an image that best represents what a co-researcher wants to express (DEALE, 2014; GARRETT & MATTHEWS, 2014). The protocols that have been developed for IN•GAUGE® studies are set up so that limitations are not imposed on how photos are acquired. IN•GAUGE® co-researchers have brought forward older images or images/screenshots from the Internet to express happier times in their lives, inspiration or different realities that they had hoped for. On a few occasions IN•GAUGE® co-researchers took the liberty of staging scenes towards theatrically constructing their photographs. For example, a co-researcher from the Adolescent Cancer Prevention study involved her family members in creating scenes that reflected her concerns with cancer and cancer prevention (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Staged scenes. Four examples of photos taken by a female co-researcher (age 12 years) from the Adolescent Cancer Prevention study. [19]

Through permitting staged photos co-researchers are able to produce depictions of the types of events (e.g., recreations of the past) that they might not have otherwise been able to capture, making photos snapshots of different thoughts and times in their lives enabling them to discuss their realities more authentically. Similarly, it is important to be conscious of the fact that photographs may not be able to provide the whole story that a co-researcher may want to share, and that space is created within the interview where co-researchers are encouraged to "fill in the gaps" orally if they so wish. [20]

Research Ethics Boards (REBs) play a strong role in determining the protocols for photovoice from beginning (i.e., recruitment) to end (i.e., dissemination) (MILLER, 2015). Limitations are placed on the types of photos that can be taken by co-researchers, such as not being able to take photos of people's faces, objects or places that make it possible to identify individuals. As a requirement by university REBs (COHEN, 2012), researchers must implement common practices and protocols such as advising co-researchers not to include people even when they consent (RUIZ-CASARES & THOMPSON, 2016), to refrain from other attributes of life which may depict potential “illegal” activity and to blur any faces that are included in the images. However, blurring and not being able to include faces is problematic for supporting the empowering aspects of photovoice, and can create negative connotations around people and their life situations (i.e., that something is wrong with that person). A father of a youth with cerebral palsy in the Children with Complex Care Needs study commented on how not including his son's face would "ruin the whole point of the picture" because "his face is the only part of his body that is mobile and expressive." This example clearly illustrates a significant challenge with limiting what co-researchers can include in photovoice. The example also begs the question, what does it mean to not include people in photos, meant to be representations of a person's life experiences and meaning constructs? This question also strongly emerges when co-researchers opt to take "selfies" (hand held self-portrait) as a way of expressing their positions within their different worlds. On several occasions, IN•GAUGE® co-researchers commented on how taking a "selfie" was a means of assuring that they were seen and that their voice was being heard through the images and helped to control how they were perceived. Co-researchers also expressed that "selfies" were being used as a modality for maintaining/building self-confidence. Including selfies can drastically shift the focus from external objects to the co-researcher, in turn changing the power dynamics in the construction of visuals (SHARE, 2015). Ethical challenges relating to the inclusion of people in photos produced through research ultimately are focused on how photos become research products that are eventually shared with wider audiences (i.e., beyond researchers and co-researchers). The next section explores some of the challenges with photovoice data interpretation and dissemination. [21]

3.3 Interpretation and dissemination

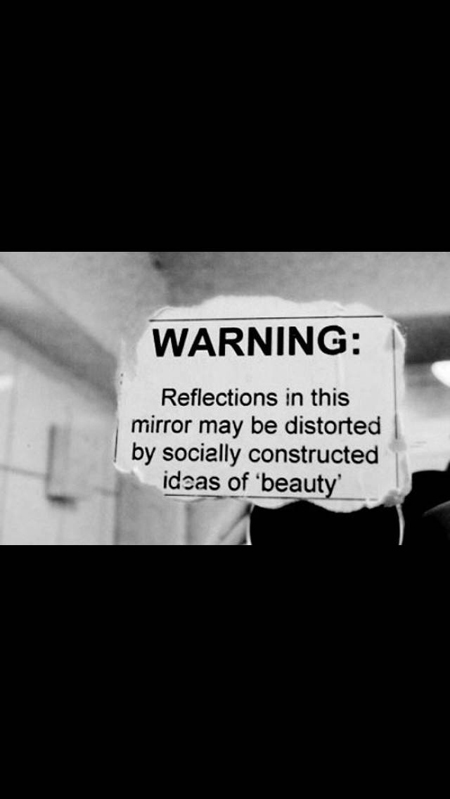

There is a growing literature on the interpretation of visual data in qualitative research (BANKS, 2001; EMMISON & SMITH, 2000; ROSE, 2007; STURKEN & CARTWRIGHT). GUILLEMIN and DREW (2010) contend that researchers should be especially concerned with the role of the co-researcher in the interpretation of visual data. Interpretations can be highly reflexive and hold multiple meanings, as is the case with all qualitative data. In interpreting their visual data, IN•GAUGE® co-researchers provide meanings for their photovoice image and then consider additional meanings through building discourse in the interview space. A co-researcher from the Youth's Voices study (female, age 17) talked about the meaning of her photograph as being something that was a trigger for thoughts on self-image (Figure 5), and then reflected further in the interview that her perception of the photo could change in the future as her self-image changed (i.e., not needing external validation).

Figure 5: A trigger for thoughts on self-image. Photo taken by a female co-researcher (age 17 years) in the Youth's Voices study.

Interviewer: "And would you change anything about it?"

Co-researcher: "I think I really like the picture, I think I really like the way it turned out."

Interviewer: "It's amazing."

Co-researcher: "Thank you (chuckle). Um I would hmm I don't know, I don't think I would change the picture, I think I would change my perception of it, like I know I can't really change the way I view myself in the mirror but just the idea that um I shouldn't have had to see this to remember so, but yeah." [22]

GUILLEMIN and DREW (2010) also maintain that researchers have a central role in interpreting the data through discerning patterns and applying theory. In this sense, the ability of the researcher to work with visual data will depend on their qualitative research skills and understanding of theory, but will also be highly dependent on their experience in working, and aptitude with, understanding visual materials. In interpreting visual data researchers must rely on their ability to see patterns, symbols, points of interest, and themes towards synthesizing data into coherent accounts of the research (SALDAÑA, 2015). Furthermore, issues around standardization can be more complex than with other forms (i.e., written) of qualitative data due to the highly interpretive attributes of visual data (WHITE & DREW, 2011). Additionally, by virtue of the process or through intention in the research design, photovoice interviews typically produce narratives, which at times are not easily triangulated with other data (PERLESZ & LINDSAY, 2003). [23]

How data will be disseminated may also depend of the level of sensitivity that is required in handling the stories shared through photovoice. Ownership and modes for dissemination can have great influence over the types of responses given by co-researchers in photovoice interviews, and ethical considerations need to be given to co-researchers' understandings of how dissemination will take place (HANNES & PARYLO, 2014). Co-researchers may feel embarrassment from sharing their images the same way that people often do not like listening to their own voices on audio recordings. A variety of considerations must go into the development of final products from research involving photovoice. The choice of final products and how they will be disseminated are essential components of the early stages of photovoice research design because they can influence participation (i.e., if people want to be part of the study or not), as well as the types of photos that are taken. [24]

Issues of privacy and ownership with visual data can be complex (GUILLEMIN & DREW, 2010). REBs may be concerned about the permanence of photographs and the implications of such permanence. This is similar to the concerns that come with the permanence of images on social media that can later have consequences for peoples' lives in, e.g., finding future employment. Some of the issues around ownership can be mitigated by giving greater control to co-researchers through establishing protocols for co-ownership of the data (i.e., the co-researcher can retract their data at any point, including when the study is over). Protocols can also be established for seeking explicit permissions for different types of images (e.g., showing faces) and different types of uses and knowledge translation (e.g., academic publications and reports vs. popular formats). [25]

People often feel strong connections to images that they produce (GOTSCHI, FREYER & DELVE, 2008). IN•GAUGE® co-researchers asked more frequently for copies of their photographs than they would for copies of interview transcripts and they expressed more interest in the final research products when visuals were part of different types of dissemination products (i.e., conference presentations, videos, exhibits). Youth and Family Advisory Councils are integral for guiding research through IN•GAUGE® and where most of the thoughts about final research products are expressed. For example, councilors for the Children Living with Complex Care Needs study and Youth Health Promotion study expressed strong interest in extending the photos towards becoming videos depicting the major themes in the research. [26]

3.4 Opportunities for the advancement of photovoice as a qualitative participatory methodology

The virtues and challenges that are associated with photovoice as a qualitative participatory methodology point to the potential for advancements based on insights from past research. Advancing photovoice as a methodology involves maintaining and enhancing those attributes that are working, as well as developing new protocols and approaches for field work and dissemination. Photovoice has been used in research predominantly to explore the thoughts and experiences of co-researchers as moments or a "snapshot in time." Some researchers have extended the temporal aspect of photovoice by asking co-researchers to take photos at various stages of a project or throughout different phases of an experience (e.g., receiving treatment for an illness). The temporal aspect of photovoice, however, is rarely extended in such a way that it is applied to reflect upon the research itself. [27]

There were several times when IN•GAUGE® photovoice co-researchers would bring insights to the research about the methodology that could affect future projects. This feedback provided insights for subsequent projects, but did not directly benefit the co-researchers within the project in which they were participating. This illuminates the necessity for a more didactic approach to be built into the structure of photovoice projects where the contributions of co-researchers are documented by researchers in such a way that lessons learned can build capacity and directly benefit the co-researchers sharing the insights. Similarly, photovoice could be carried forward into the follow-up phases of research. Researchers often struggle to find ways to effectively debrief and care for the well-being of co-researchers who may have shared deeply personal or emotional stories during (photovoice or other types of) interviews. Co-researchers as such may be left to cope with any thoughts and emotions that may have emerged during the research (e.g., talking about one's own illnesses, the illnesses or deaths of a loved one). Under the right circumstances (i.e., when the co-researcher is interested and it is not burdensome to do so), photovoice may provide a vehicle for exploring co-researchers' experiences with research and any resulting emotions that are a product of the research experience. Photovoice applied at the end of the data collection phase of research could generate crucial information that could be directed towards helping co-researchers communicate their needs. Such information could in turn help researchers put into place tools and resources for safely exiting the research. [28]

REBs have a major role to play in the ability of researchers to realize the full potential of photovoice as a participatory tool for qualitative research (MILLER, 2015). It is important that REB review protocols continue to evolve along with developing approaches to participatory and arts-based methods towards ensuring that co-researchers and researchers are safe, while not being overly restrictive to the reflexivity and emancipatory components of research process. How effectively this can be achieved will largely depend on the possibility of extending participatory and arts-based research protocols towards involving co-researchers in the setting of parameters for what is ethical and desirable in research. BOYDELL et al. (2012) reinforce that there is a need for discourse among arts-based researchers about the unique and shared ethical challenges faced by them and, in turn, communicating their discussions with policymakers and REB members. We contend that REB protocols should be adapted so that ethics and research protocols acknowledge the agency of co-researchers (including youth) and their capacity for decision-making within the research process (i.e., as is integral to research that aims towards being truly participatory in nature). Acknowledging ownership is also paramount to creating photovoice protocols that are empowering for co-researchers. As such, REBs should have protocols for enabling co-researchers to determine how materials like photographs will be used and shared in the long-term, and where they will reside following the completion of the project. This would differ from the current norms for dealing with data following the completion of a project, which usually involves full destruction of all data. [29]

Advantages, challenges and opportunities in working with photovoice in qualitative research were revealed through the literature and from studies that are part of IN•GAUGE®, a research program that has used photovoice and other visual methods for doing research with youth and families for over 15 years. Despite the popularity of photovoice, the research sheds light on the importance of giving careful consideration to the study population and the research topic towards determining if photovoice is appropriate, as well as different approaches to employing photovoice with co-researchers. We provide evidence that supports the involvement of co-researchers planning for the research and the development of protocols for all stages of a photovoice project. This includes involvement in the development of ethical guidelines for research to protocols for interpretation and knowledge translation. Additionally, options for participation should be built into guidelines due to the individual nature of co-researchers' responses being engaged through photovoice. The insights derived from the literature and through IN•GAUGE® provide touchstones for the evolution of photovoice as a participatory method in qualitative research. Enhancements to the didactic quality of the research, and considerations for extending photovoice into care following the completion of research are two areas where photovoice could be developed with great promise. Institutional support will be essential to the development of photovoice as a qualitative method. As photovoice develops, REBs will also need to put strategies into place that are capable of assessing the sophisticated approaches for photovoice, including supporting the participatory development of ethical guidelines. [30]

We would like to thank the youth and families who participated in the studies. Roberta L. WOODGATE (2011-2017) is supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research Applied Chair in Reproductive, Child and Youth Health Services and Policy Research (Grant # CIHR Applied Chairs in Reproductive, Child & Youth Health Services & Policy Research [APR] 126339).

Funded studies discussed in this article:

Woodgate, Roberta L., Principal Investigator (PI) & Pirnat, Milena (2013-2016): Living with and managing hemophilia disorders from diagnosis and through key care transitions: The journey for families of children with hemophilia (abbrev: Living with and Managing Hemophilia and other Bleeding Disorders). Canadian Hemophilia Society (CHS).

Woodgate, Roberta L.(PI); Dean, Ruth; Migliardi, Paula; Payne, Mike; Cochrane, Carla & Mignone, Javier (2013-2015): Aboriginal youth living with HIV: From diagnosis to learning to manage their health and lives (abbrev: Aboriginal Youth Living with HIV). Canadian Institutes of Health Research Operating Grant, Priority Announcement (PA): First Nations, Inuit and Metis Health from the Institute of Aboriginal Peoples' Health (Grant #: CIHR Operating Grant, PA: First Nations, Inuit and Metis Health [IPH] 131574) and Canadian Institutes of Health Research-Manitoba Regional Partnerships Program Funding (Manitoba Health Research Council).

Woodgate, Roberta L. (PI); Altman, Gary; Walker, John & Wener, Pamela (2012-2016): Youth's voices: Their lives and experiences of living with an anxiety disorder (abbrev: Youth's Voices). Canadian Institutes of Health Research (Grant #: CIHR Operating Grant [MOP] 119277).

Woodgate, Roberta L. (PI); Rempel, Gina; Ripat, Jacquie; Elias, Brenda; Moffat, Mike; Halas, Joannie; Linton, Janice & Martin, Donna (2009-2014): Understanding the disability trajectory of first nations families of children with disabilities: Advancing Jordan's principle (abbrev: First Nations Children with Disabilities). Canadian Institutes of Health Research Emerging Team Grant: Children with Disabilities (Bright Futures for Kids with Disabilities) [TWC]. (Grant #: CIHR TWC 95046).

Woodgate, Roberta L. (PI); Hallman, Bonnie; Ripat, Jacquie; Borton, Barb; Rempel, Gina & Edwards, Marie (2008-2014): Changing geographies of care: Using therapeutic landscapes as a framework to understand how families with medically complex children participate in communities (abbrev: Children Living with Complex Care Needs). Canadian Institutes of Health Research (Grant #: CIHR MOP 89895).

Woodgate, Roberta L. (PI); Halas, Joannie & Schultz, Annette (2007-2014): An ethnographic study of adolescents' conceptualization of cancer and cancer prevention: Framing cancer and cancer prevention within the life-situations of adolescents (abbrev: Adolescent Cancer Prevention). Canadian Institutes of Health Research (Grant #: CIHR MOP 84398) and Manitoba Regional Partnerships Program Funding (Manitoba Health Research Council).

Woodgate, Roberta L. (PI) (2007-2010): Youth speaking for themselves about health within their own life-situations: An ethnographic study of youth's perspectives of health and their own health interests (abbrev: Youth Health Promotion). Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council Research of Canada (Grant #: 30715).

Woodgate, Roberta L. (PI); Irani, Pourang; Degner, Lesley; Yanofsky, Rochelle; West, Christina & Watters, Carolyn (2006-2012): Development and testing of a computer video-game approach designed for self-assessment and management of meaning-centred symptom experiences by children with cancer (abbrev: Meaning-Centred Symptom Experiences by Children with Cancer). Canadian Institutes of Health Research (Grant #: CIHR MOP 79263).

1) "Co-researcher" is used here instead of "participant" in order to reflect the participatory nature of the research program. <back>

2) Full names for studies are listed in the Acknowledgments section. <back>

Banks, Marcus (2001). Visual methods in social research. London: Sage.

Boydell, Katherine M.; Gladstone, Brenda M.; Volpe, Tiziana; Allemang, Brooke & Stasiulis, Elaine (2012). The production and dissemination of knowledge: A scoping review of arts-based health research. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 13(1), Art. 32, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs1201327 [Date of access: June 26, 2016].

Buckley, Liam (2014). Photography and photo-elicitation after colonialism. Cultural Anthropology, 29(4), 720-743.

Buetow, Stephen (2013). The traveller, miner, cleaner and conductor: Idealized roles of the qualitative interviewer. Journal of Health Services Research & Policy, 18(1), 51-54.

Carlson, Elizabeth D.; Engebretson, Joan & Chamberlain, Robert M. (2006). Photovoice as a social process of critical consciousness. Qualitative Health Research, 16(6), 836-852.

Catalani, Caricia & Minkler, Meredith (2010). Photovoice: A review of the literature in health and public health. Health Education & Behavior, 37(3), 424-451.

Chonody, Jill; Ferman, Barbara; Amitrani‐Welsh, Jill & Martin, Travis (2012). Violence through the eyes of youth: A photovoice exploration. Journal of Community Psychology, 41(1), 84-101.

Cohen, Barry B. (2012). Conducting evaluation in contested terrain: Challenges, methodology and approach in an American context. Evaluation and Program Planning, 35(1), 189-198.

Cooper, Cheryl M. & Yarbrough, Susan P. (2010). Tell me—show me: Using combined focus group and photovoice methods to gain understanding of health issues in rural Guatemala. Qualitative Health Research, 20(5), 644-653.

Dahan, Rhonda; Dick, Ron; Moll, Sandra; Salwach, Ed; Sherman, Deb; Vengris, Jennie & Selman, Kim (2007). Photovoice Hamilton 2007: Manual and resource kit. Hamilton: Hamilton Community Foundation, http://www.sprc.hamilton.on.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/photovoicetoolkit.pdf [Date of access: October 31, 2016.]

Deale, Cynthia S. (2014). Students' photo perceptions of hospitality and tourism in a community: A scholarship of teaching and learning case study. Journal of Teaching in Travel & Tourism, 14(1), 1-21.

Emmison, Michael & Smith, Philip D. (2000). Researching the visual: Images, objects, contents and interactions in social and cultural inquiry. London: Sage.

Evans-Agnew, Robin A. & Rosemberg, Marie-Anne S. (2016). Questioning photovoice research: Whose voice? Qualitative Health Research, 26(8), 1019-1030.

Fayvan, Gao (Ed.) (1995). Visual voices: 100 photographs of village China by the women of Yunnan Province. Yunnan: Yunnan People's Publishing House.

Fraser, Kimberly D. & al Sayah, Fatima (2011). Arts-based methods in health research: A systematic review of the literature. Arts & Health, 3(2), 110-145.

Frisby, Wendy; Maguire, Patricia & Reid, Colleen (2009). The "f" word has everything to do with it: How feminist theories inform action research. Action Research, 7(1), 13-29.

Garrett, H. James & Matthews, Sara (2014). Containing pedagogical complexity through the assignment of photography: Two case presentations. Curriculum Inquiry, 44(3), 332-357.

Genoe, M. Rebecca & Dupuis, Sherry L. (2013). Picturing leisure: Using photovoice to understand the experience of leisure and dementia. The Qualitative Report, 18(11), 1-21, http://nsuworks.nova.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1545&context=tqr [Date of access: October 6, 2016].

Gotschi, Elisabeth; Freyer, Bernhard & Delve, Robert (2008). Participatory photography in cross-cultural research: A case study of investigating farmer groups in rural Mozambique. In Pranee Liamputtong (Ed.), Doing cross-cultural research (pp.213-231). Dordrecht: Springer.

Gray, Norma; de Boehm, Christina Oré; Farnsworth, Angela & Wolf, Denise (2010). Integration of creative expression into community based participatory research and health promotion with Native Americans. Family & Community Health, 33(3), 186.

Guillemin, Marilys & Drew, Sarah (2010). Questions of process in participant-generated visual methodologies. Visual Studies, 22(2), 175-188.

Hannes, Karin & Parylo, Oksana (2014). Let's play it safe: Ethical considerations from participants in a photovoice research project. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 13(1), 255-274, http://ijq.sagepub.com/content/13/1/255.full [Date of access: October 6, 2016].

Hergenrather, Kenneth C.; Rhodes, Scott D.; Cowan, Chris A.; Bardhoshi, Gerta & Pula, Sara (2009). Photovoice as community-based participatory research: A qualitative review. American Journal of Health Behavior, 33(6), 686-698.

Hogan, Lindsay; Bengoechea, Enrique Garcia; Salsberg, Jon; Jacobs, Judy; King, Morrison & Macaulay, Ann C. (2014). Using a participatory approach to the development of a school‐based physical activity policy in an indigenous community. Journal of School Health, 84(12), 786-792.

Jorgenson, Jane & Sullivan, Tracy (2010). Accessing children's perspectives through participatory photo interviews. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 11(1), Art. 8, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs100189 [Date of access: June 26, 2016].

Kantrowitz-Gordon, Ira & Vandermause, Roxanne (2016). Metaphors of distress: Photo-elicitation enhances a discourse analysis of parents' accounts. Qualitative Health Research, 26(8), 1031-1043.

Keller, Colleen; Fleury, Julie; Perez, Adrianna; Ainsworth, Barbara & Vaughan, Linda (2008). Using visual methods to uncover context. Qualitative Health Research, 18(3), 428-436.

Kreitler, Shulamith; Oppenheim, Daniel & Segev-Shoham, Elsa (2004). Fantasy, art therapists, and other expressive and creative psychological interventions. In Shulamith Kreitler, Myriam Weyl Ben-Arush & Andrés Martin (Eds.), Pediatric psycho-oncology: Psychological aspects and clinical interventions (pp.351-388). London: John Wiley & Sons.

Kunzendorf, Robert G. (1991). Mental imagery. New York: Plenum Press.

Lenette, Caroline & Boddy, Jennifer (2013). Visual ethnography and refugee women: Nuanced understandings of lived experiences. Qualitative Research Journal, 13(1), 72-89.

Lorenz, Laura S. (2010). Brain injury survivors: Narratives of rehabilitation and healing. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

Lorenz, Laura S. & Chilingerian, Jon A. (2011). Using visual and narrative methods to achieve fair process in clinical care. Journal of Visualized Experiments, 48, e2342, http://www.jove.com/video/2342/using-visual-narrative-methods-to-achieve-fair-process-clinical [Date of access: October 8, 2016].

Maclean, Kirsten & Woodward, Emma (2013). Photovoice evaluated: An appropriate visual methodology for aboriginal water resource research. Geographical Research, 51(1), 94-105.

Mannay, David (2010). Making the familiar strange: Can visual research methods render the familiar setting more perceptible? Qualitative Research, 10(1), 91-111.

Miller, Kyle (2015). Dear critics: Addressing concerns and justifying the benefits of photography as a research method. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 16(3), Art. 27, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs1503274 [Date of access: June 26, 2016].

Mitchell, Claudia (2011). Doing visual research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Molloy, Jennifer K. (2007). Photovoice as a tool for social justice workers. Journal of Progressive Human Services, 18(2), 39-55.

Perlesz, Amaryll & Lindsay, Jo (2003). Methodological triangulation in researching families: Making sense of dissonant data. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 6(1), 25-40.

Power, Nicole G.; Norman, Moss E. & Dupré, Kathryne (2014). Rural youth an emotional geographies: How photovoice and words-alone methods tell different stories of place. Journal of Youth Studies, 17(8), 1114-1129.

Prus, Robert (1996). Symbolic interaction and ethnographic research. Albany, NY: State University of New York.

Rathwell, Kaitlyn J. & Armitage, Derek (2016). Art and artistic processes bridge knowledge systems about social-ecological change: An empirical examination with Inuit artists from Nunavut, Canada. Ecology and Society, 21(2), 21-35, http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol21/iss2/ [Date of access: October 6, 2016].

Ripat, Jacqui & Woodgate, Roberta L. (2012). Self-perceived participation among adults with spinal cord injury: a grounded theory study. Spinal Cord, 50, 908-914, http://www.nature.com/sc/journal/v50/n12/abs/sc201277a.html [Date of access: October 11, 2016].

Rose, Gillian (2007). Visual methodologies: An introduction to the interpretation of visual materials (2nd ed.). London: Sage.

Royce, Sherer W.; Parra-Medina, Deborah & Messias, DeAnne Karen Hilfinger (2006). Using photovoice to examine and initiate youth empowerment in community-based programs: A picture of process and lessons learned. California Journal of Health Promotion, 4(3), 80-91.

Ruiz-Casares, Mónica & Thompson, Jennifer (2016). Obtaining meaningful informed consent: Preliminary results of a study to develop visual informed consent forms with children. Children's Geographies, 14(1), 35-45.

Rydzik, Agnieszka; Pritchard, Annette; Morgan, Nigel & Sedgley, Diane (2013). The potential of arts-based transformative research. Annals of Tourism Research, 40, 283-305.

Saldaña, Johnny (2015). The coding manual for qualitative researchers. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Schwartz, Sharlene (2011). "Going deep" and "giving back": Strategies for exceeding ethical expectations when researching amongst vulnerable youth. Qualitative Research, 11(1), 47-68.

Share, Jeff (2015). Cameras in classrooms: Photography's pedagogical potential. In Danilo M. Baylen & Adriana D'Alba (Eds.), Essentials of teaching and integrating visual and media literacy (pp.97-118). Dordrecht: Springer.

Sopack, Nicolette; Mayan, Maria & Skrypnek, Berna J. (2015). Engaging young fathers in research through photo-interviewing. The Qualitative Report, 20(11), 1871-1880, http://nsuworks.nova.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2396&context=tqr [Date of access: October 6, 2016].

Strack, Robert W.; Magill, Cathleen & McDonagh, Kara (2004). Engaging youth through photovoice. Health Promotion Practice, 5(1), 49-58.

Sturken, Marita & Cartwright, Lisa (2001). Practice of looking: An introduction to visual culture. New York: Oxford University Press.

Szto, Peter; Furman, Rich & Langer, Carol (2005). Poetry and photography: An exploration into expressive/creative qualitative research. Qualitative Social Work, 4(2), 135-156.

van Manen, Max (1990). Researching lived experience: Human science for an action sensitive pedagogy. London, ON: University of Western Ontario.

Wang, Caroline C. (1999). Photovoice: A participatory action research strategy applied to women's health. Journal of Women's Health, 8(2), 185-192.

Wang, Caroline C. (2006). Youth participation in photovoice as a strategy for community change. Journal of Community Practice, 14(1-2), 147-161.

Wang, Caroline & Burris, Mary Ann (1997). Photovoice: Concept, methodology, and use for participatory needs assessment. Health Education & Behavior, 24(3), 369-387.

Wang, Caroline C.; Cash, Jennifer L. & Powers, Lisa S. (2000). Who knows the streets as well as the homeless? Promoting personal and community action though photovoice. Health Promotion Practice, 1(1), 81-89.

Wang, Caroline C.; Yi, Wu Kun; Tao, Zhan Wen & Carovano, Kathryn (1998). Photovoice as a participatory health promotion strategy. Health Promotion International, 13(1), 75-86.

White, Julie & Drew, Sarah (2011). Collecting data or creating meaning? Qualitative Research Journal, 11(1), 3-12.

Whittemore, Robin; Chase, Susan K. & Mandle, Carol Lynn (2001). Validity in qualitative research. Qualitative Health Research, 11(4), 522-537.

Woodgate, Roberta L. & Busolo, David (2015). A qualitative study on Canadian youth's perspectives of peers who smoke: An opportunity for health promotion. BMC Public Health, 15(1301), http://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-015-2683-4 [Date of access: October 31, 2016].

Woodgate, Roberta L. & Kreklewetz, Christine M. (2012). Youth's narratives about family members smoking: parenting the parent-it's not fair!. BMC Public Health, 12(1), 965-978, http://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2458-12-965 [Date of access: October 6, 2016].

Woodgate, Roberta L. & Leach, Jennifer (2010). Youth's perspectives on the determinants of health. Qualitative Health Research, 20(9), 1173-1182.

Woodgate, Roberta L. & Skarlato, Olga (2015). "It's about being outside": Canadian youth's perspectives of good health and the environment. Health & Place, 31, 100-110.

Woodgate, Roberta L. & Zurba, Melanie (Under review). The "good," the "bad," and the food choices youth make: Urban Canadian youth's perspectives on "being healthy". Journal of Youth Studies.

Woodgate, Roberta L.; Edwards, Marie & Ripat, Jacquie (2012). How families of children with complex care needs participate in everyday life. Social Science & Medicine, 75(10), 1912-1920.

Woodgate, Roberta L.; West, Christina H. & Tailor, Ketan (2014). Existential anxiety and growth: An exploration of computerized drawings and perspectives of children and adolescents with cancer. Cancer Nursing, 37(2), 146-159.

Woodgate, Roberta L.; Edwards, Marie; Ripat, Jacquie D.; Borton, Barbara & Rempel, Gina (2015). Intense parenting: A qualitative study detailing the experiences of parenting children with complex care needs. BMC Pediatrics, 15(1), 197-212, http://bmcpediatr.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12887-015-0514-5 [Date of access: October 6, 2016].

Woodgate, Roberta L.; Edwards, Marie; Ripat, Jacquie D.; Rempel, Gina & Johnson, Sara F. (2016). Siblings of children with complex care needs: Their perspectives and experiences of participating in everyday life. Child: Care, Health and Development, 42(4), 504-512.

Zurba, Melanie & Friesen, Holly A. (2014). Finding common ground through creativity: Exploring Indigenous settler and Métis values and connection to land. International Journal of Conflict & Reconciliation, 2(1), 1-34.

Roberta L. WOODGATE is a Canadian Institutes of Health Research Applied Chair in Reproductive, Child and Youth Health Services and Policy Research and a professor at the Rady Faculty of Health Sciences, College of Nursing, University of Manitoba.

Contact:

Roberta L. Woodgate

College of Nursing, Rady Faculty of Health Sciences

University of Manitoba

89 Curry Pl., Winnipeg, MB, R3T 2N2

Canada

Tel.: (+1) 204 474 8338

E-mail: Roberta.Woodgate@umanitoba.ca

URL: http://umanitoba.ca/faculties/nursing/research/woodgate_chair.html

Melanie ZURBA is a research associate at the Rady Faculty of Health Sciences, College of Nursing, University of Manitoba.

Contact:

Melanie Zurba

College of Nursing, Rady Faculty of Health Sciences

University of Manitoba

89 Curry Pl., Winnipeg, MB, R3T 2N2

Canada

Tel.: (+1) 204 474 1051

E-mail: Melanie.Zurba@umanitoba.ca

Pauline TENNENT is a professional associate at the Rady Faculty of Health Sciences, College of Nursing, University of Manitoba.

Contact:

Pauline Tennent

College of Nursing, Rady Faculty of Health Sciences

University of Manitoba

89 Curry Pl., Winnipeg, MB, R3T 2N2

Canada

Tel.: (+1) 204 474 8220

E-mail: Pauline.Tennent@umanitoba.ca

Woodgate, Roberta L.; Zurba, Melanie & Tennent, Pauline (2017). Worth a Thousand Words? Advantages, Challenges and Opportunities

in Working with Photovoice as a Qualitative Research Method with Youth and their Families [30 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 18(1), Art. 2,

http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs170124.