Volume 19, No. 1, Art. 4 – January 2018

Participatory Research Into Inclusive Practice: Improving Services for People With Long Term Neurological Conditions

Tina Cook, Helen Atkin & Jane Wilcockson

Abstract: People with long-term conditions are intensive users of health services as well as being long term users of social care and community services. In the UK, the Department of Health has suggested that the development of a more inclusive approach to services could furnish benefits to people with long-term conditions and financial savings for service providers.

Researchers with a varied set of expertise and experience (users of neuro-rehabilitation services, staff working in services, people working with third sector agencies and university academics) adopted a participatory research approach to work together to explore what inclusion might look and feel like for people who are long term users of health services. The element of critique and mutual challenge, developed within the research process, disturbed current presentations of inclusion and inclusive practice. It revealed that the more usually expected components of inclusion (trust, respect and shared responsibility) whilst necessary for inclusive practice, are not necessarily sufficient. Inclusion is revealed as a complex and challenging process that requires the active construction of a critical communicative space for dialectical and democratic learning for service development.

Key words: inclusion; participatory research; service user involvement; neuro-rehabilitation; service development; critical

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. The Study: Towards Inclusive Living

3. The Core Research Group

4. Design of the Study

5. The Research in Action: Data Generation and Data Analysis

6. Findings

6.1 Inclusion

6.2 Communication

7. Discussion

In recent years there has been a resurgence of interest in participatory approaches to research (BERGOLD & THOMAS, 2012). Participatory approaches to health research that embed active participation by those with experience relevant to the research focus are now being championed from both the human rights perspective, that people should not be excluded from research that describes and affects their lives, and from a methodological perspective in terms of rigorous research (COOKE & KOTHARI, 2001; CORNWALL & GAVENTA, 2001; INTERNATIONAL COLLABORATION FOR PARTICIPATORY HEALTH RESEARCH, 2013; LING, McGEE, GAVENTA & PANTAZIDOU, 2010). This draws on the long history of worldwide social movements committed to addressing exclusion and marginalization through enacting rights and active participation in democratic process and practice with those less likely to have their voices heard. [1]

The active participation of disabled people in decision making processes about policies and programs is now enshrined in the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities from 2006. In the UK, participatory health research runs alongside a policy driver for the greater engagement of service users in health research as a means of improving both the opportunities to research "on them" (for example engagement as a means of improving recruitment possibilities) and to make research "more relevant to people's needs and concerns, more reliable and more likely to be put into practice" (DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, 2006, p.34). The importance of more embedded engagement which has the potential to affect both research and practice is, however, coming to the fore (DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, 2008a, NATIONAL INSTITUTE FOR HEALTH RESEARCH, 2015). Public involvement in research is now being defined by INVOLVE, as research:

"carried out 'with' or 'by' members of the public rather than 'to', 'about' or 'for' them. This includes, for example, working with research funders to prioritise research, offering advice as members of a project steering group, commenting on and developing research materials, undertaking interviews with research participants."1) [2]

Participatory research forefronts the participation and agency of those whose lives or work are central to the research subject in all aspects of the study. It can be viewed as being

"... a means for achieving positive transformation in society in the interest of people's health, for example by changing the way health professionals are educated, the way health care institutions work, and the politics and policies affecting the health of society" (INTERNATIONAL COLLABORATION FOR PARTICIPATORY HEALTH RESEARCH, 2013, p.3). [3]

In this article, we report on the use of a participatory research approach for a study that sought to bring together understandings of participation in both research and practice. The aim was to develop a participatory approach to research as a means to address how the concept of inclusive approaches to services in neuro-rehabilitation/neuro psychiatry are understood in, and for, practice. [4]

In 2005 the DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH calculated that approximately 10 million people in the UK had a neurological condition and for most people this had life-long consequences. Neurological conditions accounted for 20% of acute hospital admissions and were the third most common reason for seeing a General Practitioner. Due to the complexity of their needs, people with long term conditions (LTCs) are amongst the most intensive users of some of the most expensive services provided by the National Health Service (NHS) and are also long term users of social care and community services (DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH , 2007a; HAM, DIXON & BROOKE, 2012). In addition approximately 850,000 people care for someone with a neurological condition (DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, 2005). For many of these people their experience of engaging with the NHS had been alienating. Lord DARZI, in his report "High Quality Care for All" commissioned by the DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, stated that people with LTCs "feel like a number rather than a person ... [they] lack 'clout' inside our health care system" (DARZI in DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, 2008b, p.6). [5]

The research study "Towards Inclusive Living: A Case Study of the Impact of Inclusive Practice in Neuro-Rehabilitation/Neuro-Psychiatry Services" (COOK, 2011) considered the implications of a National Service Framework (NSF) for LTCs in the UK (DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH , 2005). This NSF had included a specific intention to "put the individual at the heart of care" (DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, 2005, p.5). In 2011, the NATIONAL AUDIT OFFICE (NAO) produced a report on the implementation of the NSF. This report identified serious short comings in how this was being put into practice. These included "lengthy diagnosis; poor information for patients on their condition and services; variable access to, and little integration of, health and social services; and poor quality of care in hospital" (p.5). The report concluded that putting people at the heart of care remained a key element to be addressed as people still felt excluded from decisions about their care and treatment. Literature on the development of a more inclusive approach to treatment and how this might affect the quality of life of people with LTCs, specifically long term neurological conditions (LTNCs) and their carers/family members, is sparse. Whilst there is an aspiration for sustained inclusion and participation in NHS provision in the UK (DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, 2007b), the term inclusion is often used to characterize diverse processes such as consultation, partnership, participation and collaboration. This reflects similar ambiguities in the use and understanding of the word inclusion more widely. For instance, in education, the terms integration and inclusion are often used interchangeably; yet, when they are clearly defined, they start from fundamentally different ways of thinking. Integration, in its most negative connotation, refers to integration by location, the child being in the class but struggling to engage with a variant of the regular curriculum (MEIJER, PIJL & HEGARTY, 1997, p.2). The Centre for Studies on Inclusive Education characterized inclusion by a more radical approach that embraces a philosophy of acceptance, providing a framework where policies and practices respond to diversity in ways that value each child's contribution equally. [6]

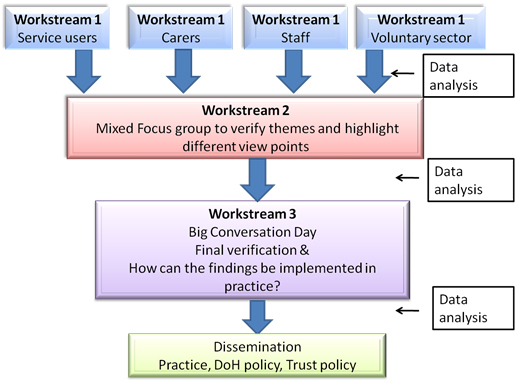

The shared use of common terminology can, however, build illusory consensus (EDELMAN, 1964) with each party believing they are striving towards similar goals. This consensus becomes problematic when the terminology, commonly understood but without shared meaning, is put into practice and endowed with specific, and different, aims and actions by the various parties. As COOK (2004) states, to avoid masking differences between the aims and practices of involved parties, and to achieve effective links between policy and practice, we need to clarify our understandings and begin to develop joint understandings around the concept. This requires "engaging participants in both concept analysis and the development of more streamlined concepts to provide useful insights to advance practice" (p.90). It can be argued that the label "inclusion" has been applied as a way of encouraging more person centered approaches in health research and practice, long before understandings about how the process of working together to achieve this have been developed and clarified. [7]

We know very little about what service users (SUs), carers/family members (CFMs) and indeed professionals understand by inclusive practice and how this relates to notions of effective services for those with LTNCs. In this article we report on the participatory design of a study that sought to bring together understandings of participation in both research and practice. It was a means to address how the concept of inclusive approaches to services in neuro-rehabilitation/neuro psychiatry, within the UK context of policy drivers for increased participation, were understood in, and for, practice. In the following sections we describe the focus of the study (Section 2), the core research group (Section 3), the design of the study (Section 4) and the integrated approach to data generation and data analysis (Section 5) before going on, in Sections 6 and 7, to present and discuss our findings. [8]

2. The Study: Towards Inclusive Living

This study directly addressed one of the key threads running through legislation in respect of LTCs, that of improving the quality of life of people by ensuring they are at the heart of care and that they have opportunities to share in shaping services that affect their own lives. In keeping with the values of a more inclusive approach to service delivery, the research approach would go beyond consultation where patients/the public act as referees, reviewers, panel members; where they sit on committees or are invited to comment on already drafted proposals. It would go beyond the engagement of patients and public in research as an "add-on" to advance current systems and dominant discourses. It was not, then, a "managerialist/consumerist" approach "concerned with including the perspectives and data of service users within existing structures and arrangements of research" (BERESFORD & TURNER, 2005, p.14). The aim was to seek to build, through what WENGER (1998) calls "communities of practice," that is groups of people that actively share concerns and passions about a topic which in turn nurtures positive working relationships and productive communication that can create a space for the dynamic interchange of knowledge and understandings. This involves all participants in co-laboring to forge new approaches and methods for research as well as sharing in carrying out that research. Co-laboring is described by SUMARA and LUCE-KAPLER as an activity that involves "... toil, distress, trouble: exertions of the faculties of the body or mind" (1993, p.393). Such research would challenge people to work together to design what "could be," with an expected outcome of the research process being change in how practice is conceptualized and carried out. Mutual learning with emergent knowledge developed through ongoing relationships was fundamental to the approach. The principle underlying assumption of the study was, therefore, that a shared commitment to understanding issues and processes offers opportunities to construct new ways of conceptualizing practice and developing ideas for improving practice (BORG, KARLSSON, HESOOK & McCORMACK, 2012, COOK, 2004). The research design would seek to provide spaces for ongoing critical discourse, spaces for the "ideal speech situation" (HABERMAS 1975, p.xviii) to build an "embodied network of actual persons" where "issues or problems are opened up for discussion, and where participants experience their interaction as fostering the democratic expression of diverse views" (KEMMIS, 2001, p.100). [9]

Through bringing together different perceptions of effective practice the research held the potential to disturb current rhetoric and beliefs held by those who participate. Such disturbances are the foundations for learning and development as it is here that "reframing takes place and new knowing, which has both theoretical and practical significance, arises" (COOK, 2009, p.277). [10]

In 2008, following the commissioning of a new building for neuro-rehabilitation and neuropsychiatry services in the north east of England, we held what we called a "Listening Event" which was an event intended to involve users in shaping the new building's development. The "Listening Event" included an opportunity for people to discuss what kind of research they thought could improve services. One topic suggested by service users was to investigate the impact on their lives if services were more inclusive. They felt that current practice tended to be dominated by clinical models of effectiveness that did not always reflect their own experience of the impact of services on their quality of life. Their suggestion was that neurological rehabilitation, if shaped around the reality and complexity of their own lived experience, could have a greater impact on their health, wellbeing and skills for independence. [11]

A core research group (CRG) of seven researchers emerged from the nucleus of people at the initial "Listening Event." Two were users of services, one was a person who cared for her family member, three were people who worked in, or with, third sector agencies (for instance Headway a charity that helps and supports people affected by acquired brain injury) and one was a member of staff from neuro-rehabilitation/neuropsychiatry services. An academic researcher with a long standing relationship with the NHS Trust concerned and expertise in inclusive research attended the "Listening Event" and was subsequently invited by the group to facilitate the research process. Most of the CRG had very little experience of research, particularly participatory research so prior to securing funding for the study the group worked together for two years to learn about the nature of qualitative/participatory approaches and how to design a research study. The CRG worked together to develop the research question, methodology and methods, ways of generating and coding data and approaches to dissemination. This long process for development cemented strong relationships that would enable critical inquiry to be central to the research practice. [12]

The nature of the design was to recruit participants to the study who mirrored the constituency of the core research group (SUs, CFMs staff members and people from third sector organizations) and to provide a framework for the research that maximized participation. The CRG had three key principles for the design: it would be inclusive, it would involve critical inquiry and it would be designed to make a difference.

Inclusive: People whose lives or work were affected by the issues in the study would be central to making decisions about how the study was framed, generating data and making meaning from that data. People would not be barred by their impairment from taking part2).

Critical: based on the assumption that when first asked about their experiences, people often have a well-rehearsed reply they offer to those who ask, the researchers would seek ways of going "beyond the already 'expert' understandings which defined their starting points" (WINTER, 1998, p.372) to shape new ways of thinking about working practices. It would offer opportunities for participants and researchers to learn something new through a process of reflecting on their own experiences, articulating and sharing these experiences with others and then working together to interpret and analyze the key themes that emanated from their own data.

Have impact: that through both the processes of the research and its dissemination changes in thinking would occur and such changes would have the potential to affect how people, and ultimately organizations, act. It was recognized that the "ripple effects" (TRICKETT, 2011, p.1354) of this type of research would be likely to continue beyond the end of the funded research period. The starting points for this research were first, the chosen topic (inclusion); second, the type of research approach (participatory); and third, that it needed to offer the potential for change in thinking and acting (it would be transformatory). [13]

The spaces the CRG devised for the research were designed to bring people together to recognize that they had shared interests but may hold different interpretations of practice priorities, spaces where "long-held views shaped by professional knowledge, practical judgement, experience and intuition are seen through other lenses" (COOK, 2009, p.277). The destabilizing of strong beliefs can, however, if not used as a supportive stepping stone for new ways of seeing, leave people feeling deskilled and demotivated. The spaces had to be created with thought and care with the building of relationships a pertinent element. The final design was, therefore, an iterative process, with three distinct but interconnected workstreams. These workstreams were cumulative in nature each having data analysis built into the process to enable the subsequent workstream to build on understandings developed during the previous one. The process was designed in accordance with strategies for robust research as set out by ROSSMAN and RALLIS (1998) who suggested that such research should include:

gathering data over a period of time rather than in a one-shot manner;

sharing the interpretations of the emerging findings with participants;

designing the study as participatory or action research from beginning to end;

drawing from several data sources, methods, investigators, or theories to strengthen the robustness of the work and;

that judgments about the value of participatory research depend on whether they ring true, i.e., those who are affected by the research topic recognize the story being told.3) [14]

The design is depicted below in Diagram 1.

Diagram 1: A participatory approach for critical conceptualization [15]

The diagram illustrates how the design allowed for people involved in the research to return to data and think about its meaning on more than one occasion. This process was integrated with the meaning making (data analysis) carried out by the CRG. It shows how both participants and the CRG came together in the Big Conversation Day (BCD) to check that the meanings that had been developed through this participatory approach for critical conceptualization made sense to those whose lives or work were at the center of the research. This iterative approach allowed for the building of trust and relationships and facilitated the rethinking of ideas, positions and meaning making. Claims for knowing were to be built from the multiple opportunities to contribute to developing knowledge. Data could then be subjected to multiple layers of critique (data analysis) by a range of people with different experiences, the premise being that this is more likely to reveal underlying concerns and meanings than analysis carried out by external researchers with their own perspective on meaning making (COOK, 2009; TSIANAKAS et al., 2012). As BLUMER warned, remaining aloof as a so-called "objective" observer, refusing to take the role of the acting unit is:

"... to risk the worst kind of subjectivism—the objective observer is likely to fill in the process of interpretation with his own surmises in place of catching the process as it occurs in the experience of the acting unit which uses it" (1969, p.86). [16]

Collaborative agency in steering a project both directs the focus of that project to the fundamental concerns of those whose lives or work are central to it, and shapes the appropriate ways for shared engagement. A recursive, critical approach to building understandings of what is known facilitates a process of gathering not only what is currently understood, but also allows for the development of those understandings through dialogical engagement, providing rich and meaningful learning processes. All people involved were learning within the research process through the action of sense making. SCHÖN (1983, p.68) used the term reflection-in-action for the process of reflecting on something that has happened whilst that reflection can still benefit that situation. "When someone reflects-in-action, he becomes a researcher in the practice context. He is not dependent on the categories or established theory and technique, but constructs a new theory of the unique case." [17]

Rather than using preconceived ideas about what should be done in a particular situation, the person reflecting decides what works best at that time, for that unique event/incident, but then goes on to reflect on the underlying essence of that action and what the implications for future practice might be (in SCHÖN's terms, reflection-on-action): "We reflect on action, thinking back on what we have done in order to discover how our knowing-in-action may have contributed to an unexpected outcome" (SCHÖN, 1983, p.26). [18]

In this way, data generation, data analysis and action are interwoven together as they are produced in the same time and space by the same collaborators. All are woven together. As WADSWORTH (1998) stated:

"... while there is a conceptual difference between the 'participation' 'action' and 'research' elements, in its most developed state these differences begin to dissolve in practice. That is, there is not participation followed by research and then hopefully action. Instead there are countless tiny cycles of participatory reflection on action, learning about action and then new informed action which is in turn the subject of further reflection … Change does not happen at 'the end'—it happens throughout" (p.7). [19]

This process has the effect of re-orientating the ideas of those concerned, providing what LATHER termed catalytic validity. Catalytic validity "refers to the degree to which the research process re-orients, focusses, and energizes participants in what Freire (1973) terms 'conscientization,' knowing reality in order to better transform it" (LATHER, 1986, p.67). Her argument was premised not only on the recognition of the reality-altering impact of the research process itself "but also on the need to consciously channel this impact so that respondents gain self-understanding and, ideally, self-determination through research participation" (ibid.). The design of the research purposefully leads to that research process becoming an action in itself. [20]

The systematic re-engagement of participants in both data generation and data analysis within the Toward Inclusive Living (TIL) project was designed to provide this strong base for interwoven, trustworthy research where changes in thinking for acting were inherent in the process. [21]

5. The Research in Action: Data Generation and Data Analysis

An open invitation outlining the nature of the study was sent to:

SUs randomly sampled from the regional NHS Trust electronic database (a confidential database of patient information) of those who had used inpatient, outpatient or community neurological rehabilitation/psychiatry services in catchment area of Trust in the past year, even if they were now discharged;

CFMs, accessed through 1. a supplementary letter included in the invitation letter to service users, 2. third sector and carers' support organizations and 3. telemarketing instigated by a service user researcher with particular skills in this work;

staff across all disciplines and all hierarchical levels recruited through the Trust staff database;

third sector agency volunteers and staff reached through local organizations and supported by the local Neurological Alliance. [22]

Anyone expressing an interest was offered more information. This information was prepared in both written and audio-visual form. People could also request a telephone conversation or a personal visit to discuss the nature of their prospective involvement. A number of home visits were made on that basis. 43 SUs, 23 CFMs, 24 staff and 8 third sector partners consented and took part in the study. All participants were over 18 years of age and able to consent for themselves.4) [23]

Below we describe the three distinctive but interconnected workstreams created with the intention to develop an iterative process. Each workstream was cumulative with data analysis processes forming an integral part. This enabled new understandings to be incorporated into the next stage of the research as they developed. [24]

Workstream 1 began the process of surfacing understandings of inclusion and where it might occur. Methods for generating data were meticulously crafted to allow people, some with impaired communication and processing skills, to participate in a way most suitable to their preferences (based on their own choice, not impairment led). The variety of methods included:

interviews and focus groups, loosely structured to encourage wide-ranging, in-depth conversations;

photography projects, which involved people taking photographs, over a one week period, of places they considered to be inclusive. The photographs taken were then tabled to provide a focus for discussion about why they had taken those particular photographs and what meanings did they attach to them. The aim of the discussion was to find out what made the subject of their photographs inclusive for them, what enabled that inclusion to happen and the impact of that on their lives;

diary keeping: Records were kept for one week, the focus of which was to articulate where people felt included and the impact of that for them. Diaries were recorded either verbally into an MP3 recorder or kept in written form according to preference;

map making of where people felt included in daily life: These were either done as diagrams or drawings. People might draw a church, their friend's house, the local post office, the pub etc. Thinking about where people felt included outside where they worked or received treatment enabled the notion of inclusion to be explored as universal, rather than something specifically related to NHS service delivery or receipt. Their map of inclusive places was then discussed with a member of the core research group and annotated with their narrative about what made places inclusive and the impact of being included in those places on their lives.

taking part in blogs/shared online conversations about inclusion through a password protected site (and using pseudonyms): This offered people the opportunity to engage in the study from their own homes, in their own time and with greater anonymity than could be offered by other methods such as focus groups;5)

the Cott Client-Centred Rehabilitation Questionnaire (COTT, TEARE, McGILTON & LINEKER, 2006) (designed for SUs only) which forefronts a client's perspective as a key component in assessing the performance of rehabilitation services. It was delivered verbally by a service user researcher who also recorded the response and completed the initial qualitative analysis of this data. [25]

To allow for full and frank discussion during Workstream 1, participants were segregated; for example, SUs and staff from the NHS would not be in the same focus group. To further reduce power/hierarchy issues, where possible the facilitating researcher was chosen to avoid conflicts of interest (e.g., SU researchers would not facilitate staff focus groups and vice versa). Data from Workstream 1 were analyzed into key themes (thematic analysis) (FEREDAY & MUIR-COCHRANE, 2006) by the CRG. This was initially undertaken collaboratively, as a learning process, to enable the core group to develop ways of understanding and categorizing data. Once the CRG had gained experience, transcripts were analyzed separately by two researchers with different experience (for instance one service user and one academic staff member) to allow differing understandings from data to be surfaced. The purpose of this was to develop an in-depth and rigorous approach to analysis that revealed both shared interpretations and differing perceptions of the meaning to be drawn from data (data analysis). Some of the key themes that emerged from this stage, and indicators of the narratives around them, are demonstrated in Table 1.

|

Theme |

Narrative |

|

Valuing people and what they know |

All people |

|

Recognizing what is important |

Different people have different priorities |

|

Accepting change |

All people need to be willing the change the usual way they think and work |

|

Choices are important |

The menu for choices needs to be jointly developed, not narrowly defined from one perspective |

|

Responsibility |

All people need to recognize they have responsibility for initiating ideas and thoughts |

|

Attitudes |

Attitudes affect the way people behave, but it is sometimes hard to recognize your own attitudes |

|

Communication |

Communication can be a challenging process: challenge can be positive in the right environment. |

Table 1: Key themes [26]

These interpretations (or emergent themes) were then fed into Workstream 2 for further discussion and critique. Providing opportunities for revisiting information, both individually and collaboratively, offered space and impetus for critical reflection. The aim was not to gather current perceptions and then decide which one was most common (consensus) but to disturb current perceptions to allow new understandings to be shaped that reflected the experience of all those involved in a meaningful way. [27]

Workstream 2 brought together all participants who had chosen to continue beyond Workstream 1 (with no segregation by experience) to discuss and develop the emerging themes. The purpose of this was to generate more in depth data about the themes and consider if new themes needed to be added. The themes from Workstream 1 were presented to the groups connected to snippets of data that illuminated the theme. Participants from all sectors of services (staff, SUs, CFMs and third sector members) discussed whether these themes adequately captured the meaning of that data. Revisiting data with people who had a range of perspectives led to agreement and disagreement, re-consideration and reshaping. It pulled apart rhetoric that can dominate single encounter, individual approaches to data collection. Each group shaped its own communicative space, some telling more stories in relation to the themes, others applying the themes to data already presented. In this way the themes were recursively explored with discussions that engaged with the plurality of perceptions thereby providing opportunities for further nuanced and in depth understandings to emerge. The emergent themes were then prepared for Workstream 3. [28]

Workstream 3 was specifically designed to not capture new data. It was essentially a mass participatory approach to communicating and validating the themes that had emerged through the data analysis processes embedded in the previous workstreams. Everyone who had taken part in the first two workstreams was invited to a Big Conversation Day. 43 of the people (44%) who had taken part in the research attended the event. The BCD was designed as a relaxed space with a focus on finalizing themes and findings emanating from data. Explaining how key themes had been developed from data to a group of people who were vastly experienced in telling their stories but inexperienced in analyzing data was a challenge for the CRG. One way of doing this was by presenting the analyzed data visually. The use of self-reflection as critique to put common understandings to the test in a collaborative forum was designed to support and confirm the unearthing and synthesis of complex and varied meanings from a range of perspectives. A number of approaches for this were used on the day, the key two being film and photography. [29]

Films

Five scenarios that reflected the key themes were transformed into playscripts. The scripts were based on sections of anonymized data already generated and analyzed in previous workstreams. These were acted out and filmed by drama students from the University as a way of allowing the people at the BCD to see that analyzed data. The resultant DVD was shown alongside the themes that had been associated with the scenarios. The data below is an example of one of the stories that was filmed as a short drama.

"[my physio] often wants you to do a certain exercise at home and he will explain it and we both [service user and carer family member] listen to him and when we get home we haven't the faintest idea how to do it! Now whether it will be more inclusive to write down what was wanted I don't know but it's done orally and so we almost always have to go back the next treatment and say 'look can you say it again' you know 'is this what you meant?' ... I don't think [physio] is quite aware of how hard it is to do that [understand and remember] but we do say that we haven't done the exercises because we didn't understand it and he takes that but he doesn't actually vary his procedure the next time" (SU 25, interview6)). [30]

The film showed the SU and physiotherapist in the clinic followed by a short clip of the SU at home. The narrative that was provided after the film was shown to people gathered at the BCD was that:

the SU and CFM appreciated the specialist service provision they encountered;

they liked their physiotherapist who they characterized as a "hands on person." They thought writing down what needed to be done, which would have helped them, was something the physiotherapist might not have been happy with;

they wanted to respect the physiotherapists working approach, so they did not ask him to write things down;

not having written notes rendered the treatment sessions relatively ineffective. [31]

The theme attached to the story at that point was "communication," particularly the importance of honest communication. This had been generated during Workstream 2. Opportunities to revisit their own data as an external watcher, in the company of others who had participated in the project, led to much interesting and animated discussion about whether this was what the scenario revealed. It enabled people to critique the themes/meanings being drawn from data rather than merely retelling their own stories, to confirm current themes and suggest new themes. [32]

Following the viewing of the film there was a general discussion from the floor and then smaller, mixed participant groups were formed to discuss understandings of the data. The key issues, the 'hot discussion topics' that emanated from these groups, were collected as themes. For example, from the data offered above, the issue of "responsibility" was raised as a theme i.e., who had the responsibility to communicate? The rationale for this theme was that the professional had a responsibility to use their professional knowledge for the good of the SU, but it was also the responsibility of SUs and CFMs to explain their health and other needs and preferences in the clearest way possible to the professional. People at the BCD agreed that to enable teamwork to happen and to develop a program that would allow SUs to apply the professional knowledge in a way that achieved the treatment goals, all had to take responsibility to communicate. [33]

Alongside the theme of responsibility, a discussion took place about the role of "deference" as an inhibitor of inclusion. People felt this characterized the stance of SUs and CFM seen in the film, a stance that hindered taking responsibility to develop honest communication for more inclusive practice. This new theme emerged through the process of collectively watching and analyzing the film during the BCD. It linked with, and complemented, earlier analysis of this data as demonstrating the importance of honest communication. It also developed the theme more precisely, recognizing the roles of responsibility in nurturing honest communications and surfacing what might hinder people in being able to take taking that responsibility. [34]

Photographs

A display of photographs taken during Workstream 1 also enabled new understandings to surface. Viewed during the BCD a staff member characterized this photograph as an example of inclusion (see Illustration 1 below).

Illustration 1: Inclusion or exclusion? Photograph taken by a service user at the local swimming pool [35]

The service user who took the photograph saw the chair as something that accentuated difference. She had called it "the ducking stool."7) This disparity in perception led to a disruption in the staff member's perceptions of this equipment, to rethink her own notions of inclusion and how her perspective might differ from that of a service user. Revealing such differences in understandings was a vital step in reshaping thinking and acting (reflection-on-action). [36]

Research that takes a more participatory stance, that seeks to build Habermasian inspired communicative spaces, also builds the potential to disturb. An indicator of success in such a project is, therefore whether this has occurred. Were reconceptualizations, or conceptual shifts, in understandings of both inclusion and the nature of communication made evident? Section 6.1 below addresses how notions of inclusion were disrupted and Section 6.2 the role of communication in developing practice to build a more inclusive approach. [37]

At the outset of the study, when first discussing inclusion, people focused on the importance of places being friendly and welcoming. For instance alongside their high standard of medical knowledge, staff were widely praised by SUs and CFMs for their commitment and friendliness:

"... you're somebody they know because they've remembered little things about your life from last time or they chat to you about their life ... Here you can go in all cheerful and relaxed. You feel you can ask things ... It's lovely" (SU 9, focus group8)). [38]

The conceptualization of inclusion, beyond friendliness was, however, nebulous and difficult to achieve. WILKINSON and McANDREW (2008), in their phenomenological inquiry into carer experiences of exclusion from acute psychiatric settings noted that inclusion was often described by what it was not, or its absence. Perhaps inclusion is hard to describe because when people are included there is nothing to contest or consider: "it's a fact that I don't often think about inclusion until I'm excluded" (Staff 8, focus group). Or perhaps, not having thought directly about the issue, meant that it was an uncontested issue for people until they tried to articulate their experiences. This extract below exemplifies the tone of many interviews, where SUs and CFMs would not describe themselves as dissatisfied, but their experiences with services left them feeling distanced from the focus of their own treatment.

"I have no complaints about the treatment. Do I feel included? I don't feel that we discuss what I am going to do next. I don't feel that we have a plan but then again maybe it just unfolds and it's to see how much progress you make ... I like to know what's happening. I'm told what's happening on a minute by minute basis but I haven't really been told what the expectations are and where I might end up and those sorts of things. I suppose because I like to have control I would like to have more understanding of why we are doing this now, what we might do next week or next month and what I can hope for. So it's not that I mind, it's not that I think anything has gone wrong, I mean I'm not a professional, what do I know? [said with irony] But I don't feel as if I'm empowered to understand fully" (SU 50, interview). [39]

The TIL study revealed that general satisfaction with service provision should not be mistaken for the delivery of effective services (see the example used in the film script, §30). Satisfaction survey approaches to characterizing services can reveal a friendly and welcoming environment but mask both exclusion and wasted resources. The iterative nature of the study allowed conversation and discussion to take place that revealed a conceptualization of inclusion as friendly and welcoming was insufficiently nuanced. The use of the reflexive approach had enabled firstly, more complex understandings (and sometimes even the lack of shared understandings) to be revealed (see the example of the "ducking stool" photograph, Illustration 1) and secondly, demonstrated that a conceptualization of inclusion as a comfortable place was leading to unarticulated dissatisfaction (see the example of SU 50, §39) and ineffective services (see the example of SU 25, §30). The key elements of the research approach, tabling of different perspectives, valuing expertise drawn from different experiences and shared engagement in mutual critique, were also seen as being fundamental to understanding inclusion and being inclusive. The concept of inclusion was thus reframed from one based only on the notion of it being a welcoming, comfortable, familiar space to one that, whilst based on respectful relationships, facilitates and includes mutual critical challenge. A critical communicative space for shared learning is fundamental for inclusion. Without it, one party risks being excluded by the dominance of the (generally well intentioned) perceptions of another, usually the one who has the most power and control in the situation at hand. Inclusion is a necessarily challenging process, where challenge is seen as a positive attribute contained within a strong, communicative relationship between practitioners and those who use services. [40]

For most staff improving communication was not a contested aspiration. Understanding the nature of communicative endeavor for inclusive practice, was, however, complex. A key issue for staff was not lack of intent to communicate, but that they were not sufficiently aware of how the complexities of power, hierarchy, positioning and ownership of the space could influence an encounter. In discussing the nature of inclusion and communication a group of staff members began that journey (see Table 2). Their discussion started with identifying places where they felt included. Some staff said they felt included during their nights out with friends. Recounting their experience of these nights out one or two began to recognize, however, that although the pub had been identified as a place of inclusion, a place with friends, not taking responsibility for communicating feelings could lead to exclusion.

|

Conversation |

Process |

|

"[A] lot of them [friends] have kids and when we go on a night out, sometimes the conversation goes to children. In a way I can relate because I've got nieces and nephews of a similar age, but then I feel excluded when I make comments, you know, like it's kind of dismissed. ... So I'm included in the social event but then when the conversation turns to something that I haven't got as much of an experience with, or if I try to include myself and it's kind of brushed off. Like, 'Oh well, what would you know, you haven't got children' " (Staff 8). |

Recognizing that in the midst of inclusion there can be exclusion |

|

"I am sometimes in that exact same situation; I would say I deliberately include myself by staying. I sit and smile. But I exclude myself as in I don't give an opinion in that situation anymore for that exact reason ... I don't have direct, first-hand experience of having children therefore my opinion isn't valid or grounded on experience" (Staff 3). |

Recognizing how own behavior can maintain/exacerbate the exclusion—that we can give off one signal as a cover to negative feeling |

|

"So do you exclude yourself or do you feel excluded by the ...?" (Staff 4) |

Colleagues ask a more probing question |

|

"I probably feel excluded by past experience and allow that to influence how I behave the next time. I mean I smile and ask questions and listen, but I don't offer opinions about how things are developing or what might be happening because ... the odd times I do spark an idea I don't express it (Staff 3)" |

The critical conversation develops deeper reflexive thinking about the reasons why this person continued to feel excluded |

|

"Exclude yourself. Or assume that you will be excluded?" (Staff 4) "... feel that you are excluded because of past experiences, really" (Staff 3). "You protect against it happening again" (Staff 4). |

The above prompted a set of musing by other staff that continued the inquiry into personal presumptions and responsibilities |

|

"Do you think your friends notice that?" (Facilitator) |

Facilitator asks a proving question |

|

"I don't know. Some people are very receptive and some aren't" (Staff 3). |

The reply leads the staff member to think more deeply, recognizing that they did not know and that it was not straight forward. |

|

"You've raised a very interesting issue there ... what if somebody comes, [a service user to an appointment] and they feel a bit excluded ... but they're politely looking okay about it, how would you ever know?" (Facilitator) |

The facilitator brings professional practice into the frame for discussion |

|

"That's where we all have to take responsibility for ... I know I'm behaving in that way, so either I could address that directly with my friends or I could ... You know, at what point does your own personal responsibility come in if you wish to participate in something?" (Staff 3) |

This member of staff started to answer in relation to practice, but still need to relate it to her own experience |

|

"I mean you're confident enough to say—to make a joke … But it's quite hard to be confident, isn't it? In that situation. And to take charge of it" (Staff 4). |

This was a bridging sentence between the personal and professional |

|

"I think it can become quite upsetting ... certainly after it happened to me I was quite reluctant to speak out but then ... because it was actually my best friend who was carrying the conversation and stuff, I just carried on the way I was and obviously it upset me the way it went on ... but I can see what you're saying about, you know, relating to a patient" (Staff 8). |

This member of staff also made the connection between her personal experience and how difficult it is for service users to articulate their thoughts even in a friendly space. |

Table 2: Example of critical reflection in a communicative space [41]

The conversation in Table 2 above demonstrates how the communicative space offered by the research process allowed staff to delve more deeply and critically into their own thoughts leading to a more nuanced understanding of how exclusion can sit within a perception of inclusion. One aim of the study was to consider how understandings of inclusion have an impact on practice. As their conversations above led them to a more critical engagement with the concept of responsibility, the staff members revealed, for themselves, some of the complex issues about why honest communication might not take place in the clinical environment and how the absence of this can lead to exclusion. Bringing together what WALSETH and SCHEI (2011, p.82) termed the patient's "life world" and the doctor's "system world" revealed the need to let go of some of the perceptions and assumptions that framed their current understandings and to re-shape their thinking. [42]

There were, however, a number of barriers to developing a more critical approach for communication within practice. Firstly, the dominant culture of the UK positions disagreement as conflict rather than it being an expression of diverse points of view that become the opportunity for fostering shared learning. The comment of this staff member on feedback from SUs exemplifies this "... the feedback that we get is not always positive, I think ... it's sometimes they're having a go at the medical staff or the therapist" (Staff 17, interview). The identification of issues to be addressed was constructed as a negative rather than a starting point for shared learning. SUs and CFMs were well aware of the danger of this construction leading to their interactions with professionals being overshadowed, as this man described, by concern that stating your own case might mean you get "on the wrong side" of the professional.

"[my wife] is a little bit 'ooh, I can't upset these people; I more or less depend entirely upon these people. If I get on the wrong side of these people, they can make my life even worse'. So [my wife] will agree, nod, 'yes' and go along with things because of ... the word I'm looking for, it's fear isn't it?" (CFM 3 and SU 13, interview). [43]

When people are uncomfortable in another person's space, and try to "be good" and "fit in" in order to reduce any perceived chance of conflict, the likelihood of shared understandings is diminished. In the UK, going to the doctors has historically been referred to as a "visit" to the doctor. This positions the service user as outsider, they are in someone else's domain and hence on their best behavior. This has a direct effect on the type of communication that takes place. Describing a visit to the doctors BASTIAN highlighted some of the historical difficulties.

"I do remember learning clearly that part of being 'good' at the doctor's was to say whatever he or she wanted to hear ... [the most important thing was to] ... nod and say 'Yes, doctor' no matter how mystified you were—and no matter how far-fetched the advice was" (2003, p.1277). [44]

Historic notions of the professional as the knower and the service user as receiver of knowledge still actively shape how services are configured and delivered. This contributes to the gap between what is needed by SUs and what is provided. As demonstrated in the study, this continuation of a perceived hierarchy of knowing emanates as much from people using services as those who work within them. Communicative spaces challenge the traditionally asymmetric relationship between doctor and patient, shifting the balance away from doctor-led, patient-led or patient-centered care towards an inclusive approach where the focus is on learning together for improved services. As stated by HUGHES, BAMFORD and MAY (2008, p.456) to improve health outcomes, more balanced power and knowledge relationships are needed to improve communication between service users and professionals. [45]

Secondly, the valuing of communication in service delivery, performance management and accountability frameworks was revealed as a major issue for staff. During a focus group a member of staff recounted spending most of a clinic listening to a CFM (attending with their relative) who was in desperate need of help and support. The listening had taken up most of the clinic time but the member of staff concerned felt it had been absolutely necessary to safeguard the health of the CFM. Their concern, however, was that this kind of approach was not part of the NHS required accountability frameworks.

"I rationalised not paying attention to the patient but paying attention to the carer, you know, and running over time [was worth doing]. But it's hard to do that, isn't it? It's hard because ... what can I write in the patient's notes?" (Staff 4, focus group) [46]

As in the United States health service practice in the UK is monitored predominantly by observables and measurable outcomes. It "... concentrates on what can be stated 'objectively', that is visible from the outside, thus tending to miss ... important features of people's actual life-worlds and meaning structures" (PAPADIMITRIOU, 2008, p.366). There was evidence from staff in the study that they felt they had to engage in a processes, termed by the NATIONAL AUDIT OFFICE Report (2011, p.9) as "perverse performance incentives," i.e., doing what could be seen to be done rather than what their professional judgment told them they needed to do, and that this could militate against more communicative approaches and ultimately affect services. Creating space for in depth communication did not fit within current accountability frameworks that predominately require the reporting of the measurable (blood pressure, psychometric testing, physical capability etc.). The overdependence on observable measures as indicators of effective practice needs to be questioned. Policy makers and commissioners of services need to recognize that overuse of accountability measures that value "action" before "in-depth communication" can be detrimental to the development of effective services. [47]

The conceptualization of communication as relationally driven space for disrupting commonly held assumptions and beliefs differs from most conceptualizations of person centered communication. It neither seeks to forefront the SU perspective as a basis for taking forward services nor that of the traditional health expert. Nor does it seek harmony as a means of engagement. It is the shared challenge of bringing together different sets of perception, experience and expertise that forms the basis of communication for inclusive practice and effective services. [48]

Authors such as VERKAAIK, ANNE SINNOTT, CASSIDY, FREEMAN and KUNOWSKI (2010, p.978) have previously argued for "productive partnerships" the aim of which is to facilitate robust, harmonious relationships. SANDMAN and MUNTHE have also suggested the need for a type of communication where "... the professional and patient both engage in a rational discussion or deliberation, trying to get all the relevant preferences, facts and reasons relating these aspects together on the table. In the end the patient decides what option to choose" (2010, p.73). [49]

Building on this work the TIL study revealed the basis of these relationships, finding critical inquiry to be a key element for effective communicative engagement. Putting "critical" and "inclusive" together would generally be seen as oxymoronic but it was clear that if notions of more "harmonious" relationships dominate understandings of inclusion this could be the cause of ineffectiveness within services and the continued domination of professionally led perceptions of inclusion. Watching a film or viewing a photograph had offered people a way to see beyond their usual perceptions and assumptions. Visual representations of data enabled people to revisit thoughts and ideas and delve deeper into practices they experienced when engaging with, or delivering, neuro-rehabilitation service. They provided a way to reflect and debate what otherwise might have been lost in the fleeting moment of talk, or the flatness of the written word on the page, neither of which are easy to share. Building more in-depth evaluative knowledge was seen to take place when people had opportunities to see their thoughts and ideas: the use of films and photographs enabled the collaborative discussion central to the research approach and, as revealed by that approach, also at the heart of inclusion and inclusive practice. [50]

The topic that formed the central pillar of this study, the nature and potential impact of more inclusive services, arose from the shared concerns of a group of people who had direct and ongoing experience of being excluded and who were frustrated by an inability to find ways to influence decisions about their own lives. It would, therefore, have been morally unacceptable to draw on a research approach that mirrored that negative experience, one that researched 'on' rather than "with" and that valued the experience and knowledge of distanced experts above those whose lives and work provided them with a particular set of knowledge and expertise often ignored in research and practice. Derived from the ontological values of the CRG this research could not be value neutral. The values of the CRG, which included being collective, communicative and co-creational, had to be reflected in the principles of the research. Such a relationally driven approach challenges notions of rigor and validity determined by more traditions forms of research, particularly those that champion the distancing of the researcher from those who are to be researched as an indicator of the quality of the knowledge produced. The merit of participatory approaches to research is determined, not by distanced measures, but by localized perceptions of value related directly to real life experience. [51]

The purpose of this relationally based communicative approach to research was to disturb current presentations of inclusive practice, including what counts as evidence of such practice, to reveal where incongruities might exist. To that effect the research needs to be judged in relation to its purpose. The varied opportunities for both data generation and analysis within the study gave strength and (to borrow a word from a more positivist paradigm) validity to our new understanding about how inclusion is perceived and how it can be developed. The participatory, interactive, staged approach used in the study gently, but firmly, opened up spaces for shared critical endeavor, revealing previously hidden issues that mask endemic exclusion. Employing dialectical processes that transcend common forms of bi-directional communication was the starting point for critical inquiry. Constructing communicative spaces where uncertainty, in both research and practice, is conceptualized as positive became a necessary forerunner to developing ways of working that challenge common understandings of inclusion and effective practice. Developing communicative spaces as the process through which practice could be opened up to scrutiny (researched), revealed that such communicative spaces were a key mechanism for developing more in depth understandings of inclusion and inclusive practice. Whilst inclusive practice is a policy objective (DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, 2005, 2007a), there are considerable barriers to implementing this (DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH , 2007a, 2007b; NATIONAL AUDIT OFFICE, 2011, 2015; WINCHCOMBE, 2012). The notion of inclusion is predominantly defined in relation to the treatment of people, as a process of conferring dignity and respect and giving equal access, and even more commonly defined by what it is not. For instance the World Health Organization, under the heading Social Inclusion and Health Equity for Vulnerable Groups opens its explication by defining social exclusion. [52]

The continued reliance on definitions that describe exclusion rather than inclusion, or concepts for inclusion that rely on bestowing elements such as dignity and respect on a person (a delivery model), can perpetuate rather than disrupt current hierarchical and exclusionary practices. The TIL study identified inadequate understandings of the importance of challenge within inclusive practice the impact this can have on the lives of SUs and their families and a potential cost for service providers in terms of untapped potential and less effective use of professional time and expertise. The recognition that foundations for inclusion are built on a form of communicative space that builds in disruptive challenge, offers some insight into why implementation of policies that forefront inclusive practices as welcoming but unchallenging spaces, may be proceeding more slowly than anticipated. To take this work forward, understandings need to move on from the notion of inclusion as "everyone feeling comfortable" to recognizing the need for it to be a process of surfacing diverse perspectives rather than relying solely on the championing of commonalities. Where inclusive practice takes place responsibility for critical reflection is shared in an active, challenging engagement, described within this project as building a "communicative space." A space were inclusion is constructed through critical dialogue, where critical means rigorous, not negative as the following participant describes "... enmesh[ing] together well ... people being prepared to listen to what I have to say and going along with it—or not! Disagreement can be inclusion as well can't it?" (SU 25, interview) [53]

We would like to acknowledge the work of the following researchers who gave their time, energy and enthusiasm to this project. Service users: Ms. Lindsay CARTER (deceased), Mr. Paul MITCHELL and Mr. Phil MOORE, carer/family member: Mrs. Eunice BELL, voluntary service representatives: Mr. Mick BOND, Ms. Christine HUTCHINSON and Mr. Alistair WHITE. Without their amazing commitment and determination this study would not have been possible.

We would like to thank, and acknowledge, the contributions of all participants who engaged so wholeheartedly with the work reported in this article. We would also like to thank Dr. Deborah GOODALL (deceased) and Mrs. Eileen BIRKS, researchers from Northumbria University for their contribution to knowledge generation and Drs. Margaret PIGGOTT and Barbara WILSON, of DeNDRoN (North East) for their ongoing support, interest and indeed participation in this project.

This work was supported by the Department of Health Policy Research Program: Long Term Neurological Conditions (Grant Number 530010).

This article is dedicated to the memory of Lindsay CARTER, musician, disabled activist, sharp thinker and service user researcher. She has been sorely missed by her fellow researchers, and Dr. Deborah GOODALL, a most respected colleague whose careful and insightful contributions, alongside her creative and thoughtful approach, will always be treasured by those who knew her and her work.

1) See http://www.invo.org.uk/posttyperesource/what-is-public-involvement-in-research/ [Accessed: March 6, 2017]. INVOLVE is an organization funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) to support active public involvement in the National Health Service (NHS), public health and social care research. <back>

2) The exceptions to this being if people were considered unable to consent for themselves under the Mental Capacity Act (http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2005/9/contents [Accessed: March 9, 2017]). <back>

3) "Recognising the story being told" has been termed as face validity by LATHER (1986, p.67). <back>

4) The complexity of applying for ethical approval for the inclusion of those who might have more difficulty in understanding the research led to their exclusion. This was a disappointment for the research team and was purely a function of the time-scale for funded research. <back>

5) Nobody chose this option initially, but supported access to computers offered to participants during the Big Conversation Day made this practical and viable.

6) This way of referencing denotes that it was data generated with a Service User (SU), 25 denotes that is was the 25th SU in the study, and in this instance data was generated through an interview. <back>

7) The ducking stool has historical connotations in the UK. It was used in the middle ages to determine whether women were witches. They were ducked into a pond on the stool, if they survived they were witches, and hence burnt at the stake, if they drowned it proved they were not a witch, but they were dead anyway. <back>

8) "SU9" relates to service user number 9 in the study. "Focus group" explains that the data was generated during a focus group. <back>

Bastian, Hilda (2003). Just how demanding can we get before we blow it?. BMJ Online, 326, 1277-1278, https://dx.doi.org/10.1136%2Fbmj.326.7402.1277 [Accessed: October 9, 2017].

Beresford, Peter & Turner, Michael (2005). User controlled research: Its meanings and potential. Final Report. Eastleigh: INVOLVE, http://www.invo.org.uk/find-out-more/user-controlled-research/ [Accessed: March 9, 2017].

Bergold, Jarg & Thomas, Stefan (2012). Participatory research methods: A methodological approach in motion. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 13(1), Art. 30, http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-13.1.1801 [Accessed: March 9, 2017].

Blumer, Herbert (1969). Symbolic interactionism: Perspective and method. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Borg, Marit; Karlsson, Bengt; Hesook, Suzie Kim & McCormack, Brendan (2012). Opening up for many voices in knowledge construction. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 13(1), Art 1, http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-13.1.1793 [Accessed: September 19, 2017].

Cook, Tina (2004). Reflecting and learning together: Action research as a vital element of developing understanding and practice. Educational Action Research, 12(1), 77-97.

Cook, Tina (2009). The purpose of mess in action research: Building rigour though a messy turn. Educational Action Research, 17(2), 277-291.

Cook, Tina (2011). Towards inclusive living: A case study of the impact of inclusive practice in neurorehabilitation/neuro-psychiatry services. DoH Policy Programme Long Term Neurological Conditions, http://nrl.northumbria.ac.uk/5602/ [Accessed: September 19, 2017].

Cooke, Bill & Kothari, Uma (2001). Participation: The new tyranny?. London: Zed Books

Cornwall, Andrea & Gaventa, John (2001). From users and choosers to shapers and makers. Institute of Development Studies Working Paper 127, Brighton, Sussex, https://opendocs.ids.ac.uk/opendocs/bitstream/handle/123456789/3473/Wp127.pdf [Accessed: October 10, 2017].

Cott, Cheryl A.; Teare, Gary; McGilton, Katherine S. & Lineker, Sydney (2006). Reliability and construct validity of the client-centred rehabilitation questionnaire. Disability and Rehabilitation, 28, 1387-1397.

Department of Health (2005). National service framework for neurological long term conditions. London: Department of Health, https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/quality-standards-for-supporting-people-with-long-term-conditions [Accessed: March 9, 2017].

Department of Health (2006). Best research for best health. London: Department of Health, https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/best-research-for-best-health-a-new-national-health-research-strategy [Accessed: March 9, 2017].

Department of Health (2007a). Long term conditions: Message from the national director for primary care & medical adviser, David Colin-Thome, http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20080906003929/http://dh.gov.uk/en/healthcare/longtermconditions/index.htm [Accessed: January 8, 2013].

Department of Health (2007b). Capabilities for inclusive practice. London: Department of Health, https://www2.rcn.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0008/513782/dh-2007-capabilities-for-inclusive-practice.pdf [Accessed: March 9, 2017].

Department of Health (2008a). Real involvement: Working with people to improve health services. London: The Stationary Office, http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/12662/ [Accessed: September 19, 2017].

Department of Health (2008b). High quality care for all: NHS next stage review. Final report. London: Stationary Office, https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/228836/7432.pdf [Accessed: March 9, 2017].

Edelman, Murray (1964). The symbolic use of politics. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press.

Fereday Jennifer & Muir-Cochrane, Eimear (2006). Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: A hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 5(1) 80-92, https://sites.ualberta.ca/~iiqm/backissues/5_1/PDF/FEREDAY.PDF [Accessed: March 9, 2017].

Habermas, Jürgen (1975). Legitimation crisis. Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

Ham, Chris; Dixon, Anna & Brooke Beatrice (2012). Transforming the delivery of health and social care: The case for fundamental change. London: The Kings Fund.

Hughes, Julian C.; Bamford, Claire & May, Carl (2008). Types of centredness in health care: Themes and concepts. Medical Health Care and Philosophy, 11(4), 455-463.

International Collaboration for Participatory Health Research (ICPHR) (2013). Position Paper 1: What is participatory health research?. Berlin: International Collaboration for Participatory Health Research, http://www.icphr.org/uploads/2/0/3/9/20399575/ichpr_position_paper_1_defintion_-_version_may_2013.pdf [Accessed: March 9th, 2017]

Kemmis, Stephen (2001). Exploring the relevance of critical theory for action research: Emancipatory action research in the footsteps of Jürgen Habermas. In Peter Reason & Hilary Bradbury (Eds.), Handbook of action research (pp.91-102). Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Lather, Patti (1986). Issues of validity in openly ideological research: Between a rock and a soft place. Interchange, 17(4), 63-84.

Ling, Andre; McGee, Rosemary; Gaventa, John & Pantazidou, Maria (2010). Literature review on active participation and human rights research and advocacy. Brighton: Institute of Development Studies, https://www.ids.ac.uk/idspublication/literature-review-on-active-participation-and-human-rights-research-and-advocacy [Accessed: September 19, 2017].

Meijer, Cor; Pijl, Sip Jan & Hegarty, Seamus (1997). Introduction. In Sip Jan Pijl, Cor Meijer & Seamus Hegarty (Eds.), Inclusive education: A global agenda (pp1-7). London: Routledge.

National Audit Office (2011). Services for people with neurological conditions: Executive Summary. London: National Audit Office, https://www.nao.org.uk/report/services-for-people-with-neurological-conditions/ [Accessed: September 19, 2017].

National Audit Office (2015). Services for people with neurological conditions. London: National Audit Office, https://www.nao.org.uk/report/services-for-people-with-neurological-conditions-progress-review/ [Accessed: September 19, 2017].

National Institute for Health Research (2015). Going the extra mile: Improving the nation's health and wellbeing through public involvement in research. The final report and recommendations to the Director General Research and Development / Chief Medical Officer (CMO) Department of Health of the "Breaking Boundaries" strategic review of public involvement in the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). London: National Institute for Health Research, http://www.nihr.ac.uk/01-archive/get-involved/Going%20the%20extra%20mile%20flyer%2015%207.pdf [Accessed: March 9, 2017]

Papadimitriou, Christina (2008). "It was hard but you did it": The co-production of "work" in a clinical setting among spinal cord injured adults and their physical therapists. Disability and Rehabilitation, 30(5), 365-374.

Rossman, Gretchen B. & Rallis, Sharon F. (1998). Learning in the field: An introduction to qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Sandman, Lars & Munthe, Christian (2010). Shared decision making, paternalism and patient choice. Health Care Analysis, 18(1) 60-84.

Schön, Donald (1983). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. London: Temple Smith.

Sumara, Dennis J. & Luce-Kapler, Rebecca (1993). Action research as a writerly text: Locating co labouring in collaboration. Educational Action Research, 1(3), 387-395.

Trickett, Edison J. (2011). Community-based participatory research as worldview or instrumental strategy: Is it lost in translation(al) research?. American Journal of Public Health, 101(8), 1353-1355. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3134503/ [Accessed: March 9, 2017].

Tsianakas, Vicki; Robert, Glenn; Maben, Jill; Richardson, Alison; Dale, Catherine & Wiseman, Theresa (2012). Implementing patient-centred cancer care: Using experience-based co-design to improve patient experience in breast and lung cancer services. Supportive Care Cancer, 20(11), 2639-2647.

Verkaaik, Julian; Anne Sinnott, Kathryn; Cassidy, Bernadette; Freeman, Claire & Kunowski Tony (2010). The productive partnerships framework: Harnessing health consumer knowledge and autonomy to create and predict successful rehabilitation outcomes. Disability and Rehabilitation, 32(12), 978-985, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20450407 [Accessed: March 9, 2017].

Wadsworth, Yoland (1998). What is participatory research?. Action Research International, http://www.aral.com.au/ari/p-ywadsworth98.html [Accessed: September 19, 2017].

Walseth, Liv T. & Schei, Edvin (2011). Effecting change through dialogue: Habermas' theory of communicative action as a tool in medical lifestyle interventions. Medicine, Health Care and Philosophy, 14(1), 81-90.

Wenger, Etienne (1998). Communities of practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wilkinson, Claire & McAndrew, Sue (2008). "I'm not an outsider, I'm his mother!" A phenomenological enquiry into carer experiences of exclusion from acute psychiatric settings. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 17(6). 392-401.

Winchcombe, Maggie (2012). A life more ordinary: Findings from the long-term neurological conditions research initiative. London: Publisher Long Term Neurological Conditions, http://www.scie-socialcareonline.org.uk/a-life-more-ordinary-findings-from-the-long-term-neurological-conditions-research-initiative-an-independent-overview-report-for-the-department-of-health/r/a11G000000182W8IAI [Accessed: September, 19, 2017].

Winter, Richard (1998). Managers, spectators and citizens: Where does "theory" come from in action research? Educational Action Research, 6(3), 361-376.

Tina COOK worked with multidisciplinary teams in health, education and social work for 20 years before joining academia. She is now a reader in inclusive methodologies at Northumbria University and visiting professorial fellow at Liverpool Hope University. At the core of her work is a focus on inclusive practice. Using participatory research, particularly collaborative action research, she seeks ways of facilitating the inclusion, as research partners, of those who might generally be excluded from research that concerns their own lives. She has published on both methodological issues and issues related to research in practice. She is an Executive Committee member of the International Collaboration on Participatory Health Research, founder of the UK Participatory Research Network and an Editor of the International Journal Educational Action Research.

Contact:

Tina Cook

Department of Social Work Education and Community Wellbeing

Faculty of Health and Life Sciences

Coach Lane Campus

Northumbria University

Newcastle upon Tyne, NE7 7XA, UK

Tel.: 0044 (0)191 215 6269

E-mail: tina.cook@northumbria.ac.uk

URL: https://www.northumbria.ac.uk/about-us/our-staff/c/tina-cook/

Helen ATKIN worked in the UK health service for over 20 years as an occupational therapist and service user involvement facilitator prior to becoming a senior researcher at Northumbria University. Central to her work is a commitment to participatory and collaborative approaches to both research and practiced that lead to changes and improvements in healthcare. She is a co-facilitator of the UK participatory Research Network and PhD candidate.

Contact:

Helen Atkin

Department of Social Work Education and Community Wellbeing

Faculty of Health and Life Sciences

Coach Lane Campus

Northumbria University

Newcastle upon Tyne, NE7 7XA, UK

Tel.: 0044 (0)191 215 6271

E-mail: helen.atkin@northumbria.ac.uk

Jane WILCOCKSON worked in the UK health service for more than a decade prior to working as a research in the Department of Education at Newcastle University. It is there that her interest in how computer assisted qualitative data analysis software (CAQDAS) can support qualitative researchers in their work was initiated. Jane enjoys a varied research career using a wide range of methodologies both within and out with Northumbria University where she now works.

Contact:

Jane Wilcockson

Department of Nursing Midwifery and Health

Faculty of Health and Life Sciences

Coach Lane Campus

Northumbria University

Newcastle upon Tyne

NE7 7XA, UK

Tel.: 0044 (0) 315 6484

E-mail: jane.wilkcockson@northumbria.ac.uk

Cook, Tina; Atkin, Helen & Wilcockson, Jane (2018). Participatory Research Into Inclusive Practice: Improving Services for People With Long Term Neurological Conditions [53 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 19(1), Art. 4, http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-19.1.2667.