Volume 18, No. 1, Art. 15 – January 2017

Telling Stories in Pictures: Constituting Processual and Relational Narratives in Research With Young British Muslim Women in East London

Cigdem Esin

Abstract: In this article, I explore the possibility that a narrative research methodology, which focuses on the processes that bring together multiple narrative modalities, could be used to gain insight into the ways in which young residents of East London construct and tell stories about their lives and negotiate their positioning as members of immigrant communities. Drawing on research undertaken with a group of young British Muslim women at the Keen Students' School in East London, I discuss the multimodal methodological approach arising within the relational, imaginative and spatial contexts of the research. I also describe how the zone of this multimodal narrative methodology facilitates an understanding of the positioning of storytellers as mobile, multiple and sometimes contradictory.

Key words: processual narrative; co-construction; positioning; narrative-led visual method; narrative modality; East London

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. Research Process

3. Methodological Approach

4. Identities and Belonging in East London: The Sociocultural Context of the Research

5. Researching in a Contact Zone

6. Complex Interactions Between Socio-Spatial Contexts and Transnational Positioning

6.1 Alex's poster featuring the Olympics and the Queen's Jubilee

6.2 Samoya's imagined landscape: A space of freedom and resistance

7. Conclusion

The broad spectrum of approaches to narratives and narrative methods in research across disciplines and cultures (ANDREWS, SQUIRE & TAMBOUKOU, 2013; HOLSTEIN & GUBRIUM, 2011) has increased the number of ways in which knowledge can be obtained from a variety of modalities beyond spoken and written narratives. Contemporary narrative research addresses the plethora of ways in which personal and grand narratives can be understood through examining stories that emerge in, for instance, visual forms and everyday objects, and by investigating the processes in which narratives are constructed (see DE FINA & GEORGAKOPOULOU, 2015; HYVÄRINEN, HYDÉN, SAARENHEIMO & TAMBOUKOU, 2010; RIESSMAN, 2008; RYAN, 2004). In this article, I report on research carried out with a small group of young British Muslim women in East London. I suggest that a multimodal narrative methodology could contribute towards an in-depth understanding of the mobility and relationality in the life stories of young people within the multilayered cultural and spatial context of East London. Engaging with the arguments on the contact zone as a methodological space (ASKINS & PAIN, 2011; TORRE et al., 2008), I propose that processual narratives generated by a multimodal method in the zone of the research workshops could open up a space for both storytellers and researchers to explore the interrelations between personal and cultural resources from which self-narratives were constituted. [1]

In its design, the research was linked to the "Visual Autobiographies in East London" study, which Corinne SQUIRE and I conducted (ESIN & SQUIRE, 2013; SQUIRE, ESIN & BURMAN, 2013) together with Chila Kumari BURMAN, Leverhulme Artist in Residence at the Centre for Narrative Research. This former project drew on a series of art workshops in which a diverse group of people who lived, worked and spent leisure time in East London made visual autobiographies contoured by life-size body shapes. Additionally, participants were interviewed about their images and image-making process. The study focused on exploring the visual autobiographies as co-constructed narratives across a number of contextual levels. The analysis focused on the visual narratives' symbolic, personal and interpersonal construction rather than on broader contextual narratives. [2]

The small-scale study on which this article is based followed a similar course. It drew on visual life story workshops with a group of five young British Muslim women aged between twelve and fourteen. Participants were asked to tell visual life stories and were subsequently interviewed about the stories they created. The workshops ran in the Keen Students' School, which had been one of the sites featured in the Visual Autobiographies research (ESIN & SQUIRE, 2013). In this follow-up study, visual storytelling was treated as a technique that would give participants more space and a specific device with which to tell their stories as opposed to the normativity involved in co-constructing life narratives in research interviews. The aim was to explore the emancipatory possibilities that visual narratives could provide for the participants (SQUIRE et al., 2014, p.43), particularly in transnational cultural spaces (O'NEILL, 2008), where life stories are heterogeneous and relational. [3]

My aim here is to take up some of the questions raised in a previous paper by ESIN and SQUIRE (2013) in relation to the role of co-construction and interaction in the constitution of visual narratives. In the former analysis, the focus was on the visual autobiographies, while verbal narratives were analyzed supplementary to the visual narratives. In this article, I examine a different set of visual stories shaped by the participants' cultural resources. The analysis moves beyond what is told in still images and focuses on the interrelations between verbal, visual and interactional narratives as part of the narrative process. The interrelations under analysis include participants' individual and familial stories, their experiences of urban spaces and their stories of transnational communities and research relations. Here, I develop the analysis in the former paper to argue that multiple modalities enabled the mobility and relationality generated within the zone of the workshops and shaped both the individual narratives and positioning of the participants. [4]

My approach to process focuses on multiple components of narrative co-construction. It involves a social space and relations that were configured through interaction between the research team and the participants, between the local context and the broader socio-cultural context of life stories. After elaborating on the methodology of the research, I discuss the broader socio-cultural context of East London that brings together biographical, relational, emotional, cultural and socio-political elements in the construction of its residents' identities. It is within this context that life stories were told and listened to in this research. [5]

I then reflect on the complex and multi-layered interactions that emerged within the contact zone of the research workshops. This section engages with arguments that consider the contact zone a methodological space, such those of ASKINS and PAIN (2011) and TORRE et al. (2008), who draw on PRATT's (2008) conceptualization of contact zone as "a social space where disparate cultures meet, clash and grapple with each other, often in asymmetrical relations of power" (p.6). Considering the research process as a methodological zone, I propose that working across multiple narrative modalities expanded the space of the contact relations and thus enabled the participants to consider the broader context of the asymmetrical power relations in which they live. [6]

I conclude with a discussion on the relational and processual constitution of individual narratives in this research by focusing on the stories of two research participants. The fragment of analysis that I offer draws on the assembly of visual, verbal and interactional narratives that emerged in the research process. It considers the links between the transnational lives of the research participants, their imagination and their mobile positioning as storytellers. [7]

The workshops ran on weekly basis at the Keen Students' School (KSS) over summer and autumn 2012. A group of five young women aged between twelve and fourteen regularly participated in the workshops. Four of the participants were from British Bangladeshi families and one was from a British Somali family. All of the participants were born and raised in East London. The research team comprised Corinne SQUIRE, Amina BEGUM, Ellie CARR, Mikka Lena PERSS and Cigdem ESIN. SQUIRE and ESIN are narrative researchers with experience in transcultural research. SQUIRE is a British academic. ESIN is an academic who migrated from Turkey to the United Kingdom. She participated in the Visual Autobiographies study and reflexively analyzed her own visual autobiography (ESIN & SQUIRE, 2013). BEGUM and CARR were undergraduate students at the University of East London at the time and were both recruited for this project as part of UEL's undergraduate internship scheme. The scheme was introduced to offer undergraduate students short-term paid professional experience. Academic members of staff were invited to submit proposals for small research in which undergraduate interns could be employed and trained. ESIN and SQUIRE proposed the project for this scheme. Both BEGUM and CARR were employed by UEL as research interns specifically for this project. The positions were advertised to all undergraduate students at UEL. BEGUM and CARR applied for the positions, were shortlisted by a panel and offered the positions after being interviewed. BEGUM lived in the neighborhood and used to be a student at the KSS. CARR had had previous experience working with young people in a community organization. PERSS was on a research internship funded by the University of Copenhagen at the time. She participated in some of the workshops as a member of the research team. BEGUM, CARR, SQUIRE and ESIN ran the weekly workshops together. They all participated in the workshops, engaged in conversations with the research participants and conducted interviews in pairs. BEGUM and CARR reported on their project experience and produced poster presentations as part of their internship. Working with research assistants made the research team diverse in terms of age, educational background and research experience. [8]

Whilst researcher and participant groups were distinct from each other on a number of demographic variables (e.g., age, nationality and educational background), both groups met to conduct activities that were new to all of them—albeit at the instigation of the researchers. They worked in an environment that brought them together weekly for a dedicated and extended time. The regular and consistent meetings of the group enabled the participants and researcher-participants to develop a relationship within the zone of the workshops. [9]

As the focus of this project was on young people's life stories, the Keen Students' School (KSS), a community-founded organization based in Tower Hamlets, was selected to run the visual stories workshops. The organization runs after-school classes in order to support students from immigrant communities in their education. It was one of the sites in which workshops for the Visual Autobiographies project ran. The participants of the workshops were recruited from after-school attendees of the KSS. [10]

The school's administration team facilitated the organization of the workshops. They agreed that the workshops could run at the same time as other study groups, with the library space being provided for the workshops. The team, who had long-term communication with the families of students, liaised with the families to advertise the content and aim of the workshops and to provide information on the researchers who would be working with the students. [11]

Students at the KSS need the permission of their families to be able to attend any class or workshop. The researchers obtained ethical approval for the study from the University of East London, and this required a consent procedure. Participants and their parents were provided with information about the research and it was made clear to participants that they held the right to withdraw from any or all aspects of the research. With the exception of one research assistant, the researchers were not members of the local community, even though SQUIRE had worked with KSS students previously. This might have created trust issues for families. Contacting families facilitated the recruitment of the workshop participants; their questions were answered and further information about the workshops and research was provided. [12]

To recruit participants, research team made a poster and distributed it to the students who attended the after-school groups that term. The poster provided basic information about the workshops. The research team was described as a group of researchers from the University of East London who were interested in life stories, including visual ones (see Illustration 1). All the students who responded to the advertisement were welcomed to the workshops.

Illustration 1: Visual Life Stories' workshop poster for research participants

Illustration 2: Desk with workshop material [13]

Participants were provided with a range of image-making resources such as acrylic paint, colored pencils, crayons and craft materials. The participants were asked to create visual images about any aspect of their lives. They were not given any specific instructions, although ESIN and SQUIRE suggested that participants could, for example, make a poster for an imagined movie of their lives or a cover image for a book about their life. The research team facilitated and participated in the workshops by engaging in conversations with the group about various aspects of everyday life such as life at school/university, families and friends. Each member of the research team also made one or more images about their life. The research team kept field notes about activities in the workshops. They also photographed the image-making process in order to document the ways in which participants shaped and appropriated the social space of the workshops. [14]

The research team interviewed the participants using a narrative approach (RIESSMAN, 2008). Participants were invited to talk about the details in their images, their participation in the workshops and their interaction with other workshop participants. The interviews took more of a conversational form than a formal question and answer exchange. The particular focus of the interviews was on the ways in which the participants constructed their images and their interactions within the workshops. All participants were interviewed either in their family home or in the KSS library where the workshops took place, except one, who did not want to give an interview because she felt that her images spoke for themselves. Additional written consent was obtained from participants and their families before each interview. [15]

The method used in this research was a narrative-led dialogical approach, an extended version of RIESSMAN's (2008) dialogic narrative analysis model. This approach enabled the research team to examine both the processes of dialogue—within the research group and with the broader narrative resources—and the visual stories. It also made it possible to consider the positioning of storytellers. The dialogical approach draws on the argument that stories are co-constructed in various interrelated contexts—interactional, historical, institutional and discursive (p.105). In this model, narratives are interpreted at two connected levels. On one level, narratives are analyzed as being co-constructed in the interactional movements between stories within any one text, including between stories of different kinds. On another level, stories are approached as being dialogically constructed (BAKHTIN, 1982) in order to stress the constantly changing constituents of narratives rather than considering them solely as finished products of particular circumstances that may change over time. As discussed in detail elsewhere (ESIN & SQUIRE, 2013), my understanding of co-constructed narratives does not presume a dialogue between equals but, rather, refers to negotiations across multiple positionings shaped by relations of power. Therefore my analysis of narratives in this study pays particular attention to positioning in narrative constructions. [16]

Exploring positioning in the analysis of narratives is one of the ways in which the multiplicity and complexity of meaning-making processes can be understood. As DAVIES and HARRÉ (1990, p.46) point out, storytellers draw upon both cultural and personal resources in constructing their stories. The conversation between and across the personal and cultural resources of both storytellers and listeners creates a discursive space in which narratives are co-constructed. Within this process, it is through the positioning of both storyteller and listener that their personal, social and cultural worlds come together in interaction. Having taken up a particular position as one's own, a person inevitably sees the world from the vantage point of that position and in terms of the particular images, metaphors and storylines that discursively shape their lives. [17]

DAVIES and HARRÉ further argue that individuals do not construct their narratives from one single position. As they draw on storylines, grand discourses and others' stories, storytellers' positions continuously change in relation to what resources they deploy. This does not mean that storytellers move freely between subject positions. While the notion of positioning may suggest that people are choosing subjects, it is in actuality the interconnections between personal, cultural, social and political resources that shape the storytellers' choices. In this article, I consider positioning as a process through which participants shape their visual stories by both varying social and cultural positions and by building up relational positions as teenagers living in inner city East London. In line with TAMBOUKOU's (2008, p.284) argument, I approach the process as an organizing plane in narrative analytics that focuses not on what stories are but on how their meaning is reconfigured by bringing in the heterogeneity of space and time connections that shape the narratives. [18]

In addition to context and positioning, I look at interconnections across narrative modalities in the process of co-construction (ESIN & SQUIRE, 2013; RYAN, 2004). I refer to narrative in a broader sense that involves verbal and visual storytelling, interaction within the visual story workshops and interviews with participants. This broader perspective enables me to analyze narrative constructions by moving between the process and the visual story in this study. With a focus on this mobility, I approach visual narratives as being constituted by interrelations between individual and cultural geographies (DOLOUGHAN, 2006), and as a space for narrative imagination, which involves continuous negotiation and interaction between the self and the other and between personal and collective thinking, not only reaching out to the future but also deeply rooted in the past (ANDREWS, 2014, pp.7-9). The recognition and contextualization of multiple resources in this space is a useful tool for exploring the processes of self-making and world-making (BRUNER, 2001). [19]

In the following sections, I first review studies on identity and belonging in East London to frame the broader sociocultural context in which visual stories emerge. I then discuss the heterogeneous and mobile exchanges that take place within the zone of the workshops. Finally, I will look into interactions between the socio-spatial context of the city and the narrative positioning of the participants, combining the visual, verbal and interactional narratives of two participants. I focus on these two particular participants because their narratives, perhaps more than those of the other participants, emerged across different narrative modalities, allowing me to assemble multiple moments in their storytelling within and across all modalities. It was through these assemblages that I was able to analyze the mobility of the participants' positioning. [20]

4. Identities and Belonging in East London: The Sociocultural Context of the Research

Narrative researchers who analyze meaning-making processes in personal narratives consider the social, cultural and political contexts part of the narrative research process (PHOENIX, 2013; SQUIRE, 2013). Depending on the research question and its disciplinary foundations, researchers' approaches to the notion of context vary. Some researchers analyze how personal narratives use and draw upon cultural context (SQUIRE, 2013); others focus their analysis on the multiplicity in the relational and societal construction of biographical narratives. These researchers do not only examine the connection between personal and cultural narratives but also consider how local and societal contexts that constitute the narratives as well as the research space are interlinked (PHOENIX, 2013, pp.77-79). [21]

In this article, context refers to multiple relations of power that shape both the micro-space of the research and the broader sociocultural context of East London. East London constitutes the transnational context in which the participants told their stories. The cross-national connections constitute heterogeneous power relations, which are shaped by culture, migration histories, personal identities, urban interactions as well as constantly changing interconnections between the local and global (BHABHA, 1994). [22]

A settlement area for generations of immigrants, East London has a history of socioeconomic inequality, changing modes of social difference and political mobilization (BEGUM, 2008; EADE, 2002). EADE, FREMEAUX and GARBIN's (2002) research into identity and the construction of imagined communities among Bangladeshi residents of East London points out the complex and contested understandings of local places and belonging in contemporary London. EADE et al. argue that East London-based Bangladeshis' lives should be understood through imagined communities that transcend national boundaries because these communities refer to their country of origin but also include a global, supranational religious community as well as multicultural elements of global London. For second and third generation British Asian residents of the area in particular, identity issues become more dynamic and multi-layered as their sense of belonging to both their communities and London consists of transnational and global elements. The identity claims of young people and their right to citizenship, resources and space are configured by this particular context. It is also crucial to look at the relational construction of their personal narratives because this produces a nuanced understanding of their experiences of the transnational and local cultures (ELLIOTT, GUNARATNAM, HOLLWAY & PHOENIX, 2009). [23]

GUNARATNAM's (2013) research on British Bangladeshi Muslim mothers' narratives about their experiences of street life in the aftermath of the 2005 suicide bombings in London delivers a nuanced analysis of the citizenship experiences of British Muslim women in the racialized space of East London. GUNARATNAM argues that the racialization of Muslims as suspicious, dangerous and disloyal citizens in the post-London bombing era has affected the limits of citizenship, matters of belonging and the right to occupy public space for Muslim citizens (pp.250-251). The heightened surveillance of Muslim citizens within this context affects gendered experiences of the city for both Muslim men and women. Anti-Islamic suspicion is projected onto the everyday lives of British Muslim women on the streets, where they find themselves under public surveillance and scrutiny in multiple ways. In her analysis of focus group exchanges between British Muslim mothers, GUNARATNAM identifies the precarious and temporal positions of the research participants in their negotiations of living in situations marked by the reconfigured racism and multiculturalism. [24]

BEGUM (2008) focuses on yet another related aspect of gender relations within British Bangladeshi communities in her study on geographies of inclusion and exclusion in East London. BEGUM points to the fact that the growing numbers of British Bangladeshi women in education and work have not necessarily led to transformations of gender relations, particularly in ethnically inscribed public spaces in East London. The bodies and behaviors of some young immigrant women are regulated by the collective norms of their communities around gender roles in society in addition to the broader anti-Islamic scrutiny in the aftermath of the 2005 bombings. Yet, BEGUM's research with young British Muslim women in this area demonstrates that they use the public space in a tactical way so as to tackle these constraints. They re-constitute their femininity in ways that challenge the dominant views of minority women as obedient members of the patriarchal-religious communities, caught in conflict between the religious and secular traditions that shape their life in London. BEGUM also argues that the strategic positioning of women members of the British-Muslim communities contributes to the constitution of a culturally and politically heterogeneous space in East London. [25]

The body of research focusing on the schooling of South Asian Muslim girls in the UK suggests that gender identities and experiences of South Asian Muslim girls remain embedded within racialized discourses that draw on stereotypical understandings of South Asian Muslim womanhood (SHAIN, 2003); for example, SHAIN (pp.7-8) argues that South Asian girls' identities at school are constructed by a number of stereotypical images that position these girls as victims of family decisions that encourage them to abandon education and consider arranged marriage. SHAIN (pp.2-4) states that in educational settings as well as other social contexts, ethnic and cultural difference remains the key to the construction of South Asian Muslim womanhood even though the girls are in the process of re-working religious and cultural aspects of their gender identity. [26]

In this space, the identities and lives of younger generations of immigrant communities need to be understood through recognition of their heterogeneity. In their research with refugee communities in East London, YUVAL-DAVIS and KAPTANI (2009, pp.57-58) point to the problematic construction of refugees in media and popular imagination in fixed and stereotypical ways. They argue that processes of identity construction follow more than one pathway and should be considered both dialogic and relational. YUVAL-DAVIS and KAPTANI suggest that the relationality between the individual and collective processes of identity construction involve both the reiteration of racialized discourses on refugee identities and more contested, shifting and multiple processes of constitution (pp.64-65). [27]

Belonging, which involves social locations, identifications and emotional attachments in transnational contexts (YUVAL-DAVIS, 2011), should also be considered a constituent of the multiplicity and relationality of the identities in East London. ANTONSICH (2010, p.645) defines belonging as a discursive resource that constructs, claims, justifies or resists forms of socio-spatial inclusion/exclusion. As I discuss in relation to the narratives of the research participants, urban interactions with the transnational and local are interlinked with the politics of belonging and how individuals respond to them. My discussion of the interactions within the zone of the workshops therefore considers the intersectional context of East London that brings together biographical, relational, emotional, cultural and socio-political elements. [28]

5. Researching in a Contact Zone

In this research, I considered the visual storytelling workshops to be a methodological zone in which the participants constructed visual narratives in the urban setting of East London, with reference to their transnational and local connections. I was also interested in the relations of the zone, the ways in which the participants responded to the idea of configuring visual narratives, the ways in which they appropriated the social space to collaboratively create their images and the way they used the space of the workshops to talk about their identities and lives in East London. [29]

Here, I borrow the notion of the contact zone as a methodological space from ASKINS and PAIN (2011) and TORRE et al. (2008), whose methodological approaches draw on that of Mary Louise PRATT (2008), who defines "contact zones" as "[s]ocial spaces where disparate cultures meet, clash, and grapple with each other, often in highly asymmetrical relations of domination and subordination-like colonialism, slavery, or their aftermaths as they are lived out across the globe today" (p.8). [30]

In their methodological approach, both ASKINS and PAIN (2011, pp.806-807) and TORRE et al. (2008, pp.24-25) use the notion of contact zone in an extended way to describe how a textured understanding of human interaction across power differences beyond simplified binaries such as oppressor/oppressed can be examined through social relations in contact zones. [31]

Since PRATT introduced the term "contact zone" in her 1992 critique of imperial encounters, it has been expanded to include the interactions between global and local, transnational and national, identity and difference and space and time. In studies of transculturation, the term is particularly useful in accommodating critical questions about the reception and appropriation of dominant cultures. In her argument, PRATT (2008) defines transculturation as the phenomenon of the contact zone to describe how subordinated and marginal groups select and invent from resources "transmitted to them by a dominant or metropolitan culture" (p.7). Within this context, an important feature of a contact perspective is that

"the interactive, improvisational dimensions of colonial encounters so easily ignored by diffusionist accounts of conquest and domination ... A contact perspective emphasizes how subjects get constituted in and by their relations to each other ... often within radically asymmetrical relations of power" (p.8). [32]

As TORRE et al. (2008) argue, designing and working within a methodological contact zone underlines the ways in which subjects and relations are configured in research. Following a similar approach, I consider the methodological contact zone of this research as constituted in an interaction between multiple contexts that shape the research relations across layers of power differences. [33]

The "Visual Life Stories" project brought together a group of researchers and participants with diverse ethnic, class, generational, educational and disciplinary backgrounds. There were numerous exchanges that reflected the social context of lives and identities within the zone of the workshops. Throughout conversations, collective drawing, image-making and photo-taking experiences, all participants including the researchers told stories about their complex and sometimes contradictory transnational lives. The complexity of contact relations in the research emerged across power differences between participants, between researchers and participants and between researchers. The conversations within the group about going to school and working in multilingual East London also revealed the ways in which difference and otherness can be experienced in relation to the dominant culture and social scrutiny on women within immigrant communities. [34]

In their research with refugee communities, using participatory theatre as a method, YUVAL-DAVIS and KAPTANI (2009) discuss how their method opened up a space for participants not only to express their recognition of otherness but also to challenge the constitution of ideas about "us and them" within the broader relations of power. The contact zone that we constituted collectively in the workshops similarly functioned as a discursive space in which experiences of otherness were discussed openly. Moreover, these conversations led to further questions around the availability of resources that the participants could use to contest the asymmetrical power relations in which they lived. Although recognition of their otherness or the collective regulations in their communities can be read as a challenge to a certain extent, the ability of the participants to consider broader inequalities is dependent on their access to social and political resources. The opportunity to access these resources is directly linked to the politics of inclusion/exclusion that operate on British Asian young people, particularly in the educational system. Although the system was designed on the principle of equality, the construction of the system does not always accommodate the heterogeneity of students' identities and interests in multicultural contexts such as East London. [35]

Within such a context, given their age and social class background, which may have had limiting effects on their movements, the participants could not always have access to material and discursive resources that would enable them to negotiate their will to be more included into those activities, even though they were able to link their limited participation in certain school activities to their "difference" (see discussion of data, below). [36]

The ability of the participants to see themselves through the eyes of others was embedded in many of the stories. The participants referred to the subtle ways in which the boundary between being English and non-English shaped their everyday life. For example, they believed that there were certain school activities such as school plays in which their chance to take part was slim. Even though they all perceived English as their first language, the immigration history of their families and their Islamic dress code highlighted their difference in social and institutional environments. In some other exchanges, their desire to 'become English' became an exercise in negotiating their differences; for example, in one conversation, there was an exchange between one of the participants and myself about why she would not take part in a play that was staged in her school. The play was A Midsummer Night's Dream by William SHAKESPEARE (2008 [1605]). It was going to be performed on an outdoor stage, which the participant thought was a nice idea. When I asked her whether she would have liked to have a role in that play, she responded by saying that it was an English play: it was not about her culture. I encouraged her to tell me more about the differentiation she made. I mentioned that she was British born and more culturally British than someone like myself, who migrated to the UK as an adult. She replied that she was British but did not feel culturally English and that even though she spoke the language and lived in London, her looks (indicating her headscarf) and her belief were different from those of English people. By this response, the participant constructed a nuanced position that demonstrated how she simultaneously felt included in and excluded from English society. [37]

A space for contact is not always free of differences, complications or "messiness," as ASKINS and PAIN (2011, p.809) underline. Relations, understanding and interactions between differently situated members of a research group such as the one in the Visual Life Story project create a messy and unpredictable contact zone. The forms of interaction and the use of time and space are negotiated in varied ways, even if the space and activities of the contact zone were pre-defined for this research; power differences across ethnic biographies and communities, generations and social classes already shaped the zone of the workshops from the moment the participants entered the library. [38]

During the first session, when the participants and researchers each introduced themselves, the tone of the interaction was formal. Generational differences in addition to the power difference between the researchers and participants were the main constituents of the zone, particularly in that first week. The idea of telling visual life stories or having conversations about life did not make much sense to the participants until we started making images together and exchanging comments on each other's visual stories. During the following weeks, the participants mirrored the way in which we initiated conversations with them by asking questions about the details of our images. These little exchanges, which focused on the visual narratives, expanded to include questions about our lives, our teaching, our students and our families. Stories about the participants' lives at school and at home were exchanged, including my story about my mother living in Turkey, SQUIRE's story about her daughter's studies and CARR's story about her cat. [39]

One important constituent of the research relations was the way in which the participants appropriated the space of the workshops and claimed a kind of ownership of it. At the beginning, the research team suggested forms such as a poster for an imagined autobiographical movie or novel and a collage. The aim of these suggestions was not to define the limits of visual storytelling but to help the participants comprehend the idea of a visual life story. The participants did not use any of the forms that were suggested, instead producing their images as they liked. In this way, they resisted positioning themselves as research participants who would contribute to the research by following the guidelines set by the researchers. The participants responded to our initial invitation to tell a visual life story in varied ways. The forms used ranged from abstract illustrations and landscapes to more graffiti-type drawings and posters. Visual storytelling turned into a practice of narrative co-construction, which involved conversations not only about the piece under production but also about other aspects of life. [40]

This resistance/appropriation encompassed both the material and the discursive space of the workshops; for example, a large desk was set at the center of the room to encourage the participants to work on their visual narratives together. Each of the participants chose her own working space in the room from the beginning of the workshops. Some of them preferred to work on the floor while others chose different corners of the room. In some sessions, some participants worked on their visual pieces and chatted in pairs while others worked individually and chatted with the researchers and other participants. [41]

This appropriation made it possible for both the participants and researchers to find out about each other through stories about families, life at school and life outside home and school. The tone of the conversations and questions about cultural backgrounds and belonging in the British culture revealed many assumptions about the British way of living. These assumptions included aspects of everyday life ranging from eating habits and dressing to the appropriate behavior of young people, particularly in East London; for example, while there was a consensus within the group about the tastelessness of English food, the participants also considered pizza and pasta to be English food, which they preferred to the Asian home cooking of their mothers. This narrative about the perception and choice of food that emerged during the interactions illustrates the strategic positioning of the participants' generation in relation to both cultures. They carefully distanced themselves from both cultures and picked up an already appropriated aspect of everyday culture such as the perception of Italian food as popular English food in order to re-configure a discursive location for their generation. [42]

From a contact perspective, using the workshops as a methodological zone worked to mediate a form of transculturation beyond the spoken language in a group where the level and use of language varied due to differences in age, education and linguistic backgrounds. The visual stories were made through a process of exploration. One theme which emerged from these explorations was the hybridity embedded in the individual narratives of the participants, which was linked to living in East London. This hybridity reflected the transnational and local relations, particularly in relation to their experiences of the city, where multiple gendered power relations were at play. Doreen MASSEY (1994) addresses the processual and relational construction of place-based identities, arguing that even among long-term residents, the gendered experiences of the city cannot be defined or compared in any straightforward way. MASSEY argues that the complexity of spatial experiences is linked to issues of power and inequality and their effects on mobility and access to resources. These inequalities do not always refer to materiality but also to control over social spaces, where "space" refers to social relations. [43]

In the following section, I will explore the narrative given by Alex (a pseudonym chosen by the participant), which emerged through her picture, interview and our conversations with her in the workshops, to discuss experiences of young women in the transnational space of East London. [44]

6. Complex Interactions Between Socio-Spatial Contexts and Transnational Positioning

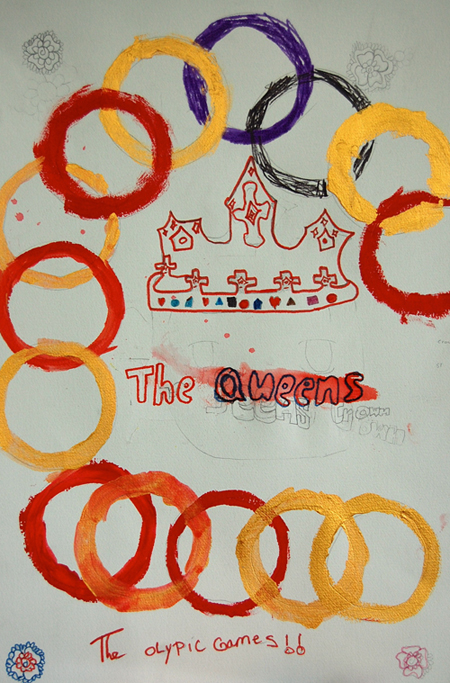

6.1 Alex's poster featuring the Olympics and the Queen's Jubilee

The art workshops constituted a site in which participants constructed narratives about their multilayered connections with the social world around them. Participants constituted narratives of their urban belonging with links to social regulations of their local communities, the public scrutiny on their British Muslim identities and their lives in East London. Alex's narrative is an exemplar.

Illustration 3: Alex's image combining the Olympics with the Queen's Jubilee

"Alex: Err, and, like, the Olympics was after it so I just got the idea of combining both of them together, so, yeah, I did those things. So, I drawed[sic] the circles of the Olympics around the crown Jubilee. I thought I would draw it like a picture of the Queen but I couldn't 'cause yeah it's gonna take, erm, like big space, so, yeah.

Researcher 1: So were you seeing a lot of images of the Jubilee and Olympics around you? Is that what ...

Alex: Oh yeah, like every time I put it on a channel on TV, yeah, like you see people talking about the Jubilee and stuff like that so just the idea came to me.

Researcher 2: Were you interested in the Jubilee? Did you watch it or was it just more that it was in your head 'cause it was all around you?

Alex: No, I [saw] it everywhere so that's just, yeah, I wasn't very interested in it.

Researcher 1: What about the Olympics, was that more interesting or the same?

Alex: Oh yeah, the Olympics, yeah, I've been waiting for that, like, for so long so ...

Researcher 1: Mm. Did you watch a lot of it?

Alex: Oh, yeah, yeah, yeah ... (Laughter)

Researcher 1: Yup, it was very good. There were quite a lot of people from London or even East London who got medals, I think.

Alex: Oh no, not that [many] of them got medals and stuff. Only, I remember Mo Farah getting one and Usain Bolt1)." [45]

Alex's visual story was an illustration that combined the Queen's Jubilee and the Olympics, which were on the public agenda in the UK at the time she made her image. She decided to make a poster featuring these two events, although she was not sure whether her artistic skills would be up to par. In her interview, Alex described her relation to the two events in an ambiguous way. When asked if she was particularly interested in the Jubilee, Alex mentioned that she was not necessarily engrossed by it but went with the theme due to the massive amount of publicity it was receiving on television that summer. However, this was not the case with her second theme, the Olympics, which she had been waiting a long time to watch. [46]

Alex was interested in these two events because they affected the social lives of residents of East London in summer 2012. She was quite reserved while talking about her level of engagement in the events; yet, in her visual narrative, she positioned herself as a young Londoner who was interested in British popular culture, sport and the public agenda of the city. [47]

Her reluctance to express her enthusiasm for the Olympics may have been partly linked to her family's expectations of her. Alex was the daughter of parents of Somali origin. Her family wanted her to have an institutional education that would provide her with security in the future. The family monitored her behavior at school and in after-school classes. Her brother came into the workshops once or twice to check how she was doing. Throughout the conversations, she told the group that she had been given a choice of subjects that she could study at school. Some subjects, such as science and English, were more acceptable than others. She was allowed to attend the visual workshops because her family thought that art was a suitable addition to a girl's education that would develop her feminine side. Even though she was interested in sport, her interest was not taken seriously. Her family thought that sport was not appropriate for a girl's academic and social education. Alex was aware of the fact that what she was allowed to do at school or in her spare time was linked to her family's ties with the Somali community in the neighborhood. Although her family wanted her to be academically strong, she was expected to be educated within the social regulations set for a girl, particularly in relation to her appearance in the public space, where she reflected upon the reputation of the family. [48]

Despite the restrictive expectations of her family and the social regulations shaping her femininity, Alex was in the process of negotiating her position as a British Somali young person with a strong individuality. She respected her family's traditions and appreciated their support for her education; however, she did not tell her story from a position of being caught between cultures and traditions, which is the dominant view of young immigrant women in East London (BEGUM, 2008). Alex voiced her enthusiasm for sport. She thought that she was not good at drawing but did not perceive this as a weakness. On the contrary, she took the opportunity to do the activity anyway and used her picture to constitute a self-narrative that brought together her interests in and her relation to the social world surrounding her. [49]

Visual storytelling proved useful in providing a space for narrative imagination in which the participants could challenge the fixed understandings of what the life stories of young people in East London should be. It also worked as a constituent of a narrative space, which made it possible to explore the relationality of the narratives of the self in depth. In the section that follows, I will focus on Samoya's narrative to discuss multimodal storytelling, through which it is possible to negotiate positioning and becoming beyond the limits of a single narrative modality. [50]

6.2 Samoya's imagined landscape: A space of freedom and resistance

In her reading of the artist Joanne LEONARD's photo-memoir, which is an assemblage of textual and visual narratives, TAMBOUKOU (2014) elaborates on the possibility of mediating multiple meanings without pinning down the storyteller "in a fixed subject position or encasing her within the constraints and limitations of her story" (p.31). In this context, the storyteller becomes a "narrative persona" whose story can be followed in the pursuit of understanding her multiple positions, rather than being considered the account of a unified subject (p.32). [51]

Similarly to TAMBOUKOU, I read Samoya's picture as an invitation from her narrative persona allowing me and others to explore her landscape, wherein she positioned herself as traveling to a "flamboyant, dreamful and peaceful" place, in her words, moving away from the busy, constraining spatiality of her life in London. Similarly to Alex, Samoya used the site of her artwork to constitute her imagined self-narrative and gave meaning to various components of her life story through a relational storytelling in the zone of the workshops.

Illustration 4: Samoya's landscape

"Samoya: I really like it, like, it's more peaceful and 'cause we live in the city and where it's so busy, you can see that picture and it's really calm.

Researcher: And if you we were going to use three words to describe the piece, what would they be?

Samoya: Flamboyant, dreamful, and peaceful." [52]

Samoya's artistic talent had been praised since she was at primary school. Seeing her enthusiasm and potential, her British Bangladeshi family also encouraged her to pursue art as an academic subject. She was planning to choose art as one of her A-level subjects at the time of the workshops. When she started attending the workshops, she had already made a plan about what she would draw. She wanted to make a large blue landscape, which she would put up on the wall of her room—an enlarged and, it turned out, changed version of an image she had already made. In the first few weeks of the workshops, Samoya focused solely on drawing the landscape and did not engage in much conversation with other participants or the researchers. As the relations in the zone of the workshops developed over the subsequent weeks, she joined the conversations, although she remained reserved while telling stories about her life to the group. [53]

In some of the sessions, particularly when gender differences in using the public spaces of the neighborhood were discussed, Samoya told us the difficulties that she experienced on streets when she was out in the evening. Samoya was aware of the constraining reality of young women's socio-spatial lives in British Muslim communities in East London, where there was a social monitoring system that watched girls' behavior. There was a tendency in the community to talk negatively about young women if they did anything inappropriate. Samoya, however, never made sense of what made any behavior appropriate or inappropriate for girls. Her family aimed to raise her as a modest woman who internalized conservative values about women's role in society. Similarly to other young women in the community, she needed to be accompanied by her brother if she went out in the evening. Even though she wanted to explore other parts of the neighborhood, where there were galleries and art workshops, she was not allowed to wander around without any appropriate purpose such as going to school or visiting relatives. [54]

None of the participants made reference to the public scrutiny on their British Muslim identities on the streets when talking about their families' intentions to monitor their movements. Rather, the participants' narratives of the family rules that restricted their movement on the streets were shaped by the gender regime in which families raised their daughters. GUNARATNAM's (2013, pp.257-259) analysis of British Bangladeshi Muslim mothers' concern with protecting their children in the racialized public spaces of East London in the aftermath of the 2005 bombings may, however, shed light on the reason behind these families' behavior. Similarly to the mothers in GUNARATNAM's research, the families of the young participants in this research might have intended to protect their children from the racialized threats that they may face when they set the rules for their daughters about how to use public spaces. [55]

Samoya remained reserved while describing her picture in the follow-up interview. Similarly to other participants, Samoya mentioned dreams, freedom and happiness while describing her artwork but avoided making direct connections between the artwork and her personal life; yet, she positioned her piece in relation to the busy life of the city and described it as "flamboyant, dreamful and peaceful." Considering the interactional narratives in which Samoya told us about her limited spatial movement in her daily life, I read the landscape and her description of it as a narrative construct of an imagined space of freedom, perhaps her "technology of resistance" (TAMBOUKOU, 2003, pp.94-102). TAMBOUKOU defines technologies of resistance as sets of practices in the cultivation of the female self with the capacity to act and resist the power relations imposed upon them at the same time as they are subjected to certain systems of power to craft precarious ethical positions in fashioning new forms of subjectivities. Samoya's narratives across different modalities are similarly constructed as a technology of resistance, shaped by her careful positioning between her dream of freedom and her restricted socio-spatial experiences as a young British Muslim woman living in East London. [56]

In this article, which draws on research undertaken with a small group of young British Muslim women in East London, I have discussed how a multi-modal narrative methodology could be used to gain insight into the complex and mobile ways in which life stories are constructed in a multilayered transnational context. This methodological approach focuses on the process in which multiple narrative modalities, such as visual, verbal and interactional, form a layered relational web in which the personal narratives can emerge. It was within this relational web that multiple narratives were configured through the nuanced interconnections between the individual and collective and between personal and public components of socio-spatial belonging. [57]

I described the relational context of a series of visual storytelling workshops by engaging with the arguments on the contact zone as a methodological space ASKINS and PAIN (2011) and TORRE et al. (2008) that extend PRATT's (2008) definition of contact zone. Similarly to TORRE et al. (2008), I considered the relations in the contact zone of the workshops as a methodological device to examine the textured interaction between the participants and researchers across power differences. Throughout the conversations and collective and individual image-making experiences, multiple interactions reflected racialized assumptions about transnational identities. The interaction within the group also functioned as a tool to challenge these assumptions. Within the zone of the workshops, visual storytelling expanded contact relations so as to lead to further exchanges about the broader relations of power and inequalities embedded in the lives of East London's residents. [58]

Considering narratives as relationally constructed within the zone of this research made it possible to explore the participants' multiple discursive positions in their self-narratives. Exploring the mobility of the storytellers' positioning is significant in examining storytelling, which moves beyond the limits of coherence to constitute processual narratives that could accommodate the complexity of transnational experiences. Approaching narratives as being processual also opened up a path towards a more nuanced understanding of self-narratives that does not encase them within the limitations of one told story or the storyteller within one fixed subject position. [59]

The movement across different narrative modalities (visual, verbal and interactional) allowed me to create a relational space for the co-construction and analysis of the individual narratives in a mobile way. Making assemblages using moments of storytelling within different modalities enabled me to consider narratives beyond what one single narrative modality can possibly offer. These assemblages can also widen the research space by making some of the narrative resources, which may not be evident in the immediate research setting, recognizable to both storytellers and researchers. Within the context of this research, these resources include the conversations with families and friends in various social environments, in relations of education, actual and imagined experiences of the streets and dialogues with the self and others. It was these resources that guided us, the researchers, into the nuanced positioning of the storyteller-participants. [60]

Another possibility that a multimodal narrative methodology can offer is the discursive contact space, wherein researchers and participants can develop relations in non-linear ways, opening up new, maybe unexpected, paths through which storytellers can negotiate the potential of processual narratives in crafting ethical positions to challenge the hegemonic discourses. Alex's narrative, which reflected a strong individuality and resisted taking up a position of being caught between cultures and traditions, and Samoya's positioning in her landscape, an imagined space of freedom, are examples of such ethical positions that have been crafted processually. [61]

I would like to thank all the young women who participated in the "Visual Life Story" workshops. Their stories and questions guided my development of the idea of processual narrative.

1) Mo Farah is a British athlete with Somalian origin. He was a gold medalist and one of the popular athletes in 2012 London Olympics. Usain Bolt is a Jamaican athlete and an Olympic gold medalist. He was one of the mediatic athletes of the 2012 Olympics with his statement victory pose which refers to a popular dancehall music move in Jamaica. <back>

Andrews, Molly (2014). Narrative imagination and everyday life. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Andrews, Molly; Squire, Corinne & Tamboukou, Maria (Eds.) (2013). Doing narrative research. London: Sage.

Antonsich, Marco (2010). Searching for belonging—An analytical framework. Geography Compass, 4, 644-659.

Askins, Kye & Pain, Rachel (2011). Contact zones: Participation, materiality, and the messiness of interaction. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 29(5), 803-821.

Bakhtin, Mikhail (1982). The dialogic imagination. Austin, TX: Texas University Press.

Begum, Halima (2008). Geographies of inclusion/exclusion: British Muslim women in the east end of London. Sociological Research Online, 13(5), Art. 10, http://socresonline.org.uk/13/5/10.html [Accessed: November 25, 2016].

Bhabha, Homi (1994). The location of culture. London: Routledge.

Bruner, Jerome (2001). Self-making and world-making. In Jens Brockmeier & Donal Carbaugh (Eds.), Narrative and identity: Studies in autobiography, self and culture (pp.25-37). Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Davies, Bronwyn & Harré, Rom (1990). Positioning: The discursive construction of selves. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 20, 43-63.

De Fina, Anna & Georgakopoulou, Alexandra (Eds.) (2015). The handbook of narrative analysis. Sussex: John Wiley & Sons.

Doloughan, Fiona (2006). Narratives of travel and the travelling concept of narrative: Genre blending and the art of transformation. In Matti Hyvärinen, Anu Korhonen & Juri Mykkänen (Eds.), The travelling concept of narrative (pp.134-144). Helsinki: The Helsinki Collegium for Advanced Studies.

Eade, John (Ed.) (2002). Living the global city: Globalization as local process. London: Routledge.

Eade, John; Fremeaux, Isabel & Garbin, David (2002). The political construction of diasporic communities in the global city. In Pamela Gilbert (Ed.), Imagined Londons (pp.159-176). New York: State University of New York Press.

Elliott, Heather; Gunaratnam, Yasmin; Hollway, Wendy & Phoenix, Ann (2009). Practices, identification and identity change in the transition to motherhood. In Margaret Wetherell (Ed.), Theorising identities and social action (pp.19-37). Basingstoke: Palgrave.

Esin, Cigdem & Squire, Corinne (2013). Visual autobiographies in East London: Narratives of still images, interpersonal exchanges, and intrapersonal dialogues. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 14(2), Art. 1, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs130214 [Accessed: November 10, 2015].

Gunaratnam, Yasmin (2013). Roadworks: British Bangladeshi mothers, temporality and intimate citizenship in East London. European Journal of Women's Studies, 20(3), 249-263.

Holstein, James & Gubrium, Jaber (Eds.) (2011). Varieties of narrative analysis. London: Sage.

Hyvärinen, Matti; Hydén, Lars-Christer; Saarenheimo, Marja & Tamboukou, Maria (Eds.) (2010). Beyond narrative coherence. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Massey, Doreen (1994). Space, place and gender. Cambridge: Polity.

O'Neill, Maggie (2008). Transnational refugees: The transformative role of art? Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 9(2), Art. 59, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs0802590 [Accessed: November 10, 2015].

Phoenix, Ann (2013). Analysing narrative contexts. In Molly Andrews, Corinne Squire & Maria Tamboukou (Eds.), Doing narrative research (pp.72-87). London: Sage.

Pratt, Mary Louise (2008). Imperial eyes: Travel writing and transculturation. New York: Routledge.

Riessman, Catherine (2008). Narrative methods for the human sciences. New York: Sage.

Ryan, Marie Laure (2004). Narrative across media. Lincoln, NB: Nebraska University Press.

Shain, Farzana (2003). The schooling and identity of Asian girls. Staffordshire: Westview House.

Shakespeare, William (2008 [1605]). A midsummer night's dream (ed. by j. Bate). London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Squire, Corinne (2013). Experience-centred and culturally oriented approaches to narrative. In Molly Andrews, Corinne Squire & Maria Tamboukou (Eds.), Doing narrative research (pp.47-71). London: Sage.

Squire, Corinne; Esin, Cigdem & Burman, Chila (2013). "You are here": Visual autobiographies, cultural-spatial positioning, and resources for urban living. Sociological Research Online, 18(3), Art. 1, http://www.socresonline.org.uk/18/3/1.html [Accessed: November 10, 2015].

Squire, Corinne; Davis, Mark; Esin, Cigdem; Andrews, Molly; Harrison, Barbara; Hyden Lars-Christer & Hyden, Margareta (2014). What is narrative research? London: Bloomsbury.

Tamboukou, Maria (2003). Women, education, and the self: A Foucauldian perspective. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Tamboukou, Maria (2008). Re-imagining the narratable subject. Qualitative Research, 8(3), 283-292.

Tamboukou, Maria (2014). Narrative personae and visual signs: Reading Leonard's intimate photo memoir. Auto/Biography Studies, 29(1), 27-49.

Torre, Maria Elena; Fine, Michele; Alexander, Natasha; Bilal Billups, Amir; Blanding, Yasmine; Genao, Emily; Marboe, Elinor; Salah, Tahani & Urdang, Kendra (2008). Participatory action research in the contact zone. In Julio Cammarota & Michelle Fine (Eds.), Revolutionizing education: Youth participatory action research in motion (pp.23-44). New York: Routledge.

Yuval-Davis, Nira (2011). The politics of belonging: Intersectional contestations. London: Sage.

Yuval-Davis, Nira & Kaptani, Ereni (2009). Performing identities: Participatory theatre among refugees. In Margaret Wetherell (Ed.), Theorizing identities and social action (pp.56-74). Basingstoke: Palgrave.

Cigdem ESIN is a senior lecturer in psychosocial studies and co-director of the Centre for Narrative Research, at University of East London, UK. She has been involved in research on gender, employment, women's movements and organizations and sexuality of young people in Turkey and the UK. Her research interests are in the interconnections between micro and macro narratives, narratives of migrants and refugees, multimodal narratives and visual storytelling within transcultural and multilingual contexts. She is the author of "Narrative Analysis: the Constructionist Approach" in The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Data Analysis (with Mastoureh FATHI and Corinne SQUIRE, 2014) and "What Is Narrative Research?" (with Corinne SQUIRE, Mark DAVIS, Molly ANDREWS, Barbara HARRISON, Lars-Christer HYDEN, and Margareta HYDEN, Bloomsbury, 2014).

Contact:

Dr Cigdem Esin

Psychosocial Studies & Centre for Narrative Research

School of Social Sciences

University of East London

Docklands Campus,

London E16 2RD, UK

Tel.: +44 (0)208 223 4280

E-mail: c.esin@uel.ac.uk

URL: https://www.uel.ac.uk/Staff/e/cigdem-esin

Esin, Cigdem (2017). Telling Stories in Pictures: Constituting Processual and Relational Narratives in Research With Young

British Muslim Women in East London [61 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 18(1), Art. 15,

http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs1701155.