Volume 19, No. 2, Art. 15 – May 2018

Using Ketso in Qualitative Research With Female Saudi Teachers

Dalal AlAbbasi & Juup Stelma

Abstract: New perspectives on education can emerge when the voices of teachers are articulated in the research process. This is especially the case in contexts where teachers' voices have not often been heard. In this article, we provide a data-driven exploration of the potential of Ketso, a visual-tactile focus group method originating in participatory research, to generate female Saudi teachers' views on technology use in education. The design of Ketso is based on a tree metaphor, and it employs written input and group discussion. Our analysis reveals how Ketso enabled the voices of each of the female teachers to be heard and how it helped participants to extend their initial individual views in conversation with others. Moreover, the physical nature of Ketso, with its shared workspace and turn-taking built into the use of colored leaves for asking different questions, kept the participants focused on what was important to them, whilst avoiding shared or strong views to be magnified. We conclude that Ketso can be used beyond its participatory origins as an inclusive data generation tool in qualitative research. We also discuss what additional steps may be taken to make the voices of the female Saudi teachers more visible.

Key words: Ketso; focus groups; mind mapping; voice; Saudi Arabia; research methods; educational technology

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. Eliciting Female Saudi Teachers' Voices

3. Focus Group Methodology

3.1 Ketso as a focus group methodology

4. The Study

5. Exploring the Ketso Focus Group Session

5.1 Giving everyone a voice

5.2 Identifying individual and similar views

5.3 Keeping the participants focused

6. Conclusion

Ketso, a hands-on method of encouraging dialogue in groups, was originally developed within a participatory and action research tradition (FURLONG & TIPPETT, 2013). It has been used in a wide range of contexts, from its roots in community development and environmental planning, to refugee integration, health service delivery, to engineering (TIPPETT, 2013). It is seen to have the "ability to facilitate ... individual 'voice' and group analysis" (McINTOSH & COCKBURN-WOOTTEN, 2016, p.148). In this article, we explore the potential of this method as an inclusive qualitative research tool. The research was conducted with female Saudi teachers. [1]

The decision to use Ketso with female Saudi teachers was motivated by their limited presence in research and policy debate. As a group, they occupy positions on all levels of the educational system and are, therefore, a key resource for the future development of education in Saudi Arabia (JAMJOOM, 2010). Moreover, the anchoring of these female teachers in the day-to-day practices of education gives their voice a particular authority (KIRK & MacDONALD, 2001). A key aim of this article is to show how the Ketso focus group methodology may present these teachers' voices in research and potentially, then, to be more recognized in the Saudi educational system. [2]

In the following, we analyze the use of Ketso in focus group sessions conducted with female Saudi teachers. We start by situating the potential importance of working with female Saudi teachers (Section 2). Next, there is an outline of focus groups as a research methodology, with the use of Ketso contrasted with "standard" focus groups (Section 3). We then introduce the study reported on in this article (Section 4). This is followed by a data-driven exploration of the effects of using Ketso, illustrated with examples from the research process (Section 5). We conclude with a summary of what we believe are the benefits of using Ketso as an inclusive data generation tool in qualitative research, as well as what may be the next steps in making the voices of these female teachers known to wider sets of stakeholders in the Saudi context (Section 6). [3]

2. Eliciting Female Saudi Teachers' Voices

GOODSON (1991, p.36) argued early for "reconceptualising educational research so as to assure that 'the teacher's voice' is heard, heard loudly, heard articulately." GOODSON suggested that the traditional focus on teaching practice is a point of maximum vulnerability for teachers since it usually does not allow them to articulate the reasons behind their choices and is, therefore, unhelpful for understanding teachers' experience. Rather, the focus should be on teachers talking about their own lives as teachers. With this methodological shift, GOODSON proposed that researchers must accept teachers' own judgments about what is important in their teaching, curriculum design and other aspects of education in schools. [4]

Following GOODSON's position, we believe that eliciting the voices of female teachers, who are working and interacting with students, policies, curricula, resources and society, is particularly important for the development of education in Saudi Arabia. The education of females in Saudi Arabia has increased rapidly over the past decades (HAMDAN, 2005). UNESCO reports that the Saudi female literacy rate has risen from 57% in 1992 to 76% in 2004 and estimates this to climb to 85% by 2015, including a rate of 98% among 19-24 year olds (UNESCO, 2013, pp.38-39). With a separate educational system for females, this trend has prompted a number of government initiatives to educate more female teachers. However, research seems to lag behind these developments. The research that has taken place in the female part of the educational system has largely viewed teachers, learning and the curriculum as mutually exclusive entities, thereby preventing any effective interrogation of female teachers' contextualized experience (JAMJOON, 2010). [5]

The feminist-inspired literature on voice provides an additional reason for making the voices of female Saudi teachers heard. BELENKY, CLINCHY, GOLDBERGER and TARULE (1997) argue that if the representatives of authority are male, then women are less likely to identify with this authority. They go on to suggest that this may pertain even if the women sympathize with the positions advocated by the males in authority, and even if they see themselves as part of the socioeconomic and cultural group whose positions are dominant. Finally, BELENKY et al. suggest that women's unique identification with dominant positions may lead to a comparative openness to novel perspectives. This resonates with the authors' view of female Saudi teachers; it lets us see the strengths of these female Saudi professionals and allows for the possibility that female Saudi teachers may sympathize with male educational authorities. Moreover, if the view of these female professionals could be made visible to broader audiences, including policymakers, they could play a role in effecting change. [6]

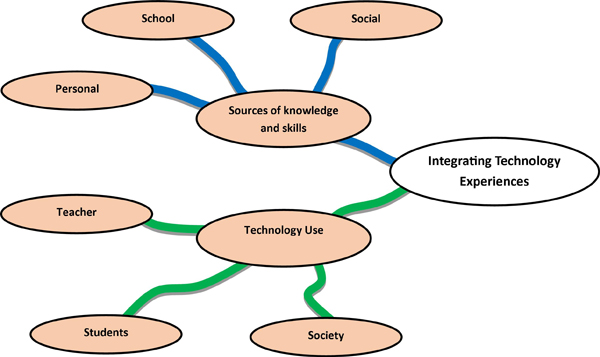

As a final point in this section, we want our approach to eliciting and presenting female Saudi teachers' voices to be sensitive to how groups of women promote female causes within Saudi Arabia. AL-DABBAGH (2015, p.236) describes this as including some groups that "embrace a formal organizational structure that includes committee work, regular face-to-face meetings, and membership fees," while others are "fluid networks without leaders that interact virtually via social media." Yet other groups "form sporadically, appearing in reaction to an event and dissolving quickly." AL-DABBAGH also points out that these groups tend to avoid "exclusively feminist agenda[s]" and that "using language strategically is an important way for groups to retain their independence" (ibid). Hence, these groups will generally avoid terms such as activism [nashita] or feminism [nasawiyya]. Finally, the focus of these groups includes conservative and liberal causes. In the arena of education, we have not come across any organized groups promoting female causes. Following BELENKY et al. (1997), we are open to the possibility that, whilst they may agree with key aspects of education promoted by the authorities, female Saudi teachers may be open to new ways of thinking about education, and that, as insiders who currently do not have much visibility, they may act as a conduit for new ideas that could invigorate education in the Kingdom. This article, then, may be seen as an outline of what initial steps can be made to set in motion such a development, whilst respecting and emulating the caution with which this is happening, in other domains, within Saudi Arabia. [7]

Focus group methodology, broadly defined, is a research process designed to promote group interaction in a safe space. This group interaction may generate insights into group norms, cultural values, and other attitudes and opinions (BLOOR, FRANKLAND, THOMAS & ROBSON, 2001; SIM, 1998). More emancipatory views include those of KITZINGER (1995, p.299), who suggests that "when [focus] group dynamics work well the participants work alongside the researcher, taking the research in new and often unexpected directions," and BIVENS (2014, p.17), who asserts that "through the sharing of challenges and solutions, research participants come to develop a more complete and holistic understanding of their situation." In addition, HARRISON and BARLOW (1995, p.12) argue that sharing experiences in focus groups "empowers group members who feel that their views and experiences are valued." [8]

We also believe that focus group methodology can enable the development of participants' voices. To be effective, this requires space and time for the voices to be heard. In the context of qualitative research, we believe that focus group methodology can act to create this space and time. Writers such as GILLIGAN (1982) and BELENKY et al. (1997) draw on sociocultural theory (LURIA, 1979; VYGOTSKY, 1978) to define voice as "ways of speaking" that facilitates "working things out" (BELENKY et al., 1997, p.33). These sociocultural roots suggest that voice is central in generating participants' own understanding as well as in influencing others and the social environment. BELENKY et al. (p.26) argue that for this reflective and generative form of voice to develop "the oral and written forms of language must pass back and forth between persons who ... speak and listen or read and write—sharing, expanding and reflecting on each other's experiences." This is exactly the sort of interaction that focus groups encourage. BELENKY et al. further suggest that "such interchanges lead to ways of knowing that enable individuals to enter into the social and intellectual life of their community" (ibid.). [9]

One critique of focus group methodology is that it can encourage more confident members of a group to dominate (SIM, 1998). This means that focus groups may be less than ideal for uncovering individual views—especially from more passive participants. It also means that a focus group methodology is unlikely to yield all group members' views on every aspect; hence, the identification of group norms may not be as reliable as is sometimes claimed. Another potential limitation of focus group methodology is the tendency for participants to focus on what they "find interesting to discuss' rather than 'what they think is important" (SIM, 1998, 349). This may be particularly prone to happen if the participants already know each other well (PARKER & TRITTER, 2006). A related phenomenon is the "magnification effect," which CAREY (1995, p.489) describes as a "synergistic, bandwagon effect similar to 'groupthink'." Crucially, CAREY claims that when triangulated with other forms of data, such as questionnaire data, the magnification effect "is always negative" (p.490); that is, focus groups may encourage an inordinate, collective magnification of shared and strong views. [10]

Focus group methodology has been used with Arab female participants. WINSLOW, HONEIN and ELZUBEIR (2002) report on the use of focus group methodology in a project aimed at identifying Emirati women's health needs. They observed unexpected idiosyncrasies, such as the facilitator doing much of the talking, group members talking over each other, and occasionally individuals engaging in one-to-one discussion with the facilitator. They also comment on the impact of seating arrangements, the physical setting of the focus group event, local patterns of interaction, and how the facilitator presented herself. RYAN, AL SHEEDI, WHITE and WATKINS (2015) used focus groups with Omanis completing a UK-based nursing studies program. They decided to separate males and females to "respect traditional customs and encourage people to speak more freely" (p.377), and they found that "issues of place, hospitality and researchers' dress were important" (ibid.). Moreover, they discovered the importance of making sure that the female focus group met in a place that their male relatives would not object to. [11]

Neither of these projects used a facilitator of the same nationality and gender as the focus group participants; but both accounts reflected on the impact of nationality and gender, as well as the broader impact of other research team members. Interesting, in this regard, is how focus group interaction can be structured by more or less indigenous ways of knowing (ROMM, 2015). Finally, neither project overtly conceived of their participants as being members of a larger homogenous Gulf or Arab culture. Instead, they emphasized the particularity of their participants and their settings (see THOMAS, 2008 for a discussion of focus group methodology for Gulf or Arab nationals viewed as belonging to a single larger culture). [12]

One final aspect that we wish to highlight is the contrast that can be made between "focus groups" and "group interviews." PARKER and TRITTER (2006) argue that whilst focus groups are centrally concerned with creating particular group dynamics, with insights generated by group interaction and with the researcher in a facilitative role, in the case of group interviews "the mechanics of one-to-one, qualitative, in-depth interviews ... [are] ... replicated on a broader (collective) scale" (p.26). This distinction is significant for the contribution we develop in this article. As we progress through the analysis of actual Ketso interactive data, we will point to instances where group dynamics resulted in the cumulative or collaborative generation of similar or shared views, as well as to instances where the "mechanics" of qualitative interviewing were employed by the facilitator, and how this altered the focus group methodology as a qualitative research tool. [13]

3.1 Ketso as a focus group methodology

In a typical Ketso session, participants are asked to reflect on their experience, identify positive aspects of situations as well as challenges they face, and respond to challenges by thinking of solutions. This is enabled by the nature of the hands-on kit, with color-coded "leaves" on which participants write their ideas, and a felt surface on which they place their completed leaves alongside thematic branches (see Figure 1). The Ketso developers (TIPPETT & HOW, 2011) state that focus group facilitators may develop their own meaning for the differently colored leaves. However, they give several options for standard meanings for different contexts, which all roughly follow the pattern: brown leaves signify "what works" or "what we have already" (metaphorically corresponding to the soil in which the three structure grows); green signifies "future possibilities" or "solutions" (corresponding to new leaves in the tree); yellow signifies "goals" (loosely linked to the sun driving growth); grey signifies "challenges" (corresponding to clouds that get between us and the sun, but also bring rain—to grow more ideas; for additional uses see pp.15-20).

Figure 1: A Ketso session with a group of female Saudi teachers [14]

The visual structure of Ketso is inspired by the notion of mind-mapping (see BUZAN & BUZAN, 1996) and the suggestion that thinking is aided by placing a main subject in the center of a physical representation of space, with themes branching out from this center. A further assumption is that starting a new mind-map provides a productive "space" for generating new ideas. Mind mapping also emphasizes the use of images and colors to aid creativity and recall. In Ketso, the leaves serve as metaphorical images of ideas, making these ideas feel alive and growing. Ketso places equal emphasis on individual and group knowledge and participation. With multiple individuals able to feed in ideas at the same time, the resulting thematic branches "on the table" act as a "hard copy" of the event for the researcher and the participants. Finally, the visual-tactile aspect of participants deciding where to place leaves on the Ketso branches (FURLONG & TIPPETT, 2013) will, potentially, activate a wider range of cognitive processes than what may be the case with "standard" focus group methodology. [15]

The name "Ketso" means "action" in Sesotho, the language of Lesotho where the tool was first developed by TIPPETT (1998) to encourage local participation in village planning. TIPPETT found that Ketso helped villagers to see how they, themselves, could improve the quality of their lives using their own creativity and locally available resources. Further development of Ketso, as reported in TIPPETT, HANDLEY and RAVETZ (2007), has focused on "new and more effective ways to incorporate participatory processes into ecological planning" (p.9). The UK-based participants in TIPPETT et al.'s project valued "the anonymity of having ideas on the table, disassociated from the person who came up with them [as this allowed] more controversial ideas to be aired, and facilitate[d] a more constructive attitude to group discussion" (p.50). TIPPETT et al. also found that the physical presence of ideas on the Ketso felt helped the participants "to see connections between their thoughts and other people's," and made participants "less apt to take a dogmatic approach to defending their [own] ideas" (ibid.). [16]

The use of Ketso in research is epistemologically anchored in participatory research, where questions around the ownership and co-production of knowledge, as well as returning knowledge to its origins, are being asked. BERGOLD and THOMAS (2012, p.19) define participatory research as "conducted directly with the immediately affected persons" and aiming at "reconstruction of their knowledge and ability in a process of understanding and empowerment." We believe that the mind-set of participatory research is evident also in qualitative research, which increasingly values giving voice to participants (CZYMONIEWICZ-KLIPPEL, BRIJNATH & CROCKETT, 2010). Moreover, Ketso has already been used by research that may be said to span the territory between participatory and qualitative research. This includes research into sustainability skills in the workplace by TIPPETT et al. (2009) and the various studies already reported upon. It also includes the work of WHITWORTH, TORRAS I CALVO, MOSS, KIFLE and BLÅSTERNES (2014, 2015), who used Ketso to empower local action in a Norwegian library setting—the participatory element—as well as to gather qualitative data to be used for generalizing findings about knowledge landscapes in libraries. [17]

Reminding ourselves of the participatory origins of Ketso helps us to move away from seeing focus group methodology as "data collection," where participants "supply" qualitative data to the researcher. It helps us to see more clearly focus group methodology as the "generation" of qualitative data enabled by the co-activity of the participants, the researcher, and the particular focus group methodology used. In terms of the participatory frame, then, our use of Ketso is intended to be inclusive, in the sense that all the participants in the focus group session should have a voice and play an active role in the interaction that generates the data. Our position is similar to BAGNOLI and CLARK (2010), who draw on the participatory research frame "to design research that may be more appropriate to the world-views of potential participants and that consequently has the potential to make change by being better designed research" (p.103). We believe, then, that the participatory origins of Ketso may result in research that is "better" or more able to elicit female Saudi teachers’ voices in an inclusive manner. This, therefore, may enable a step towards the further development of education in Saudi Arabia that is "better" than if the data is "extracted" in a one-way flow from participants to the researcher. [18]

The data we use in this article originates in a larger study, employing interviews and Ketso to explore female maths, science, language and religious studies teachers' experiences with new technology in state primary schools in Saudi Arabia. The larger study is the doctoral project of the first author (ALABBASI, 2016). She is a Saudi female, was born and educated in Saudi Arabia, and has worked as a teacher and teacher educator in Saudi schools and training centers. The second author, STELMA, is a UK-based academic, who has worked with ALABBASI as her doctoral supervisor (and in the case of the present article, as her co-researcher). [19]

The Ketso focus group session that we will explore here took place with six female teachers in a religious school (Tahfeez Quran, مدرسة تحفيظ قران), where, in addition to national curriculum subjects such as maths, science, language, social and religious studies, the female pupils have classes focused on memorizing the Holy book of Islam—the Quran. The fieldwork was done by ALABBASI. She first gained permission from the Saudi Ministry of Education and then met with the school head teacher to explain the aims of the research and how she wished to work with the school's teachers. The head teacher welcomed ALABBASI as a researcher, provided a room for the focus group sessions, and allowed the distribution of information about the research to the teachers. ALABBASI is from the region in which this state primary school is located, but she had no previous relationship with the school, the head teacher or any of the teachers. [20]

Prior to the Ketso session, the teachers received an information pack enabling them to give their informed consent to participate. At an agreed date and time, everyone gathered in the allocated room and sat around a table covered by the Ketso felt surface. The session started with the researcher introducing herself and her project. Based on the researcher's experience of working and living in the Saudi context, as well as comments made by different teachers and head teachers, the expectation was that the female teachers would reject being audio-recorded. However, as soon as the purpose of the recording was made clear—to provide an accurate account of what they said, and to enable their voices to be heard—the female teachers were happy to be audio-recorded. In fact, some even asked the researcher to use their real names when citing them in her research. However, to preserve anonymity, a cited benefit of Ketso (see Section 3), the female Saudi teachers are referred to using pseudonyms. [21]

This particular, positive reception that the researcher received could, in part, be predicted by the literature on facilitating focus groups with female participants in Gulf or Arab contexts (RYAN et al., 2015; THOMAS, 2008; WINSLOW et al., 2002). The teachers appeared to view the researcher as a fellow Saudi and a fellow female teacher, thereby giving her access to indigenous ways of knowing (ROMM, 2015). At the same time, the researcher was viewed as an outsider (her main experience was from the private sector). For instance, when the researcher asked if they bought things with their own money, the teachers responded: "Look we are in state school here, not private. We buy everything with our own money." Finally, perhaps because she was doing her research at a well-known UK university, the teachers seemed to view the researcher as a potential "change agent," as someone who might help change their future. These different identities may well have interacted in the participants' minds over the time of the fieldwork, thereby creating what THOMSON and GUNTER (2011) term a "liquid identity" for the researcher. [22]

The Ketso session was conducted entirely in Arabic and was introduced to the participants using the analogy of a tree. The Ketso felt was placed on the table, with the trunk of the tree representing the focus on "experiences of technology integration," and the two main branches representing two themes: "sources of knowledge and skills" and "technology use." These two predetermined themes were further divided into sub-themes, as evident in Figure 2.

Figure 2: The Ketso branch structure [23]

The colored leaves were used, as originally suggested by Ketso (see previous section), but with the following topic-specific nuancing: brown leaves for experiences of learning and using technology, yellow leaves for positive impacts of using technology, grey leaves for challenges associated with using technology, and green leaves for suggested solutions, i.e., ways to overcome challenges. [24]

The session started with the "sources of knowledge and skills" theme, and the researcher asking, "How do you learn and develop your technology skills?" The teachers were given 3-4 minutes to write their experience on brown leaves; they could use as many leaves as they wished. The researcher provided continual reassurance that there were no right or wrong ideas and encouraged the teachers to focus on their own experiences, rather than any imagined experiences of other teachers. Next, the female teachers took turns to read their leaves, and as a group, they positioned each leaf on one of the three sub-themes (personal, school and social—see Figure 2). Occasionally, this resulted in the writing of yet more leaves as a group. To make transparent shared views, the teachers were asked to place any duplicated or similar statements together. [25]

Next, the teachers were asked, "What are the positive impacts and feelings associated with these experiences?" Each teacher individually recorded positive impacts and feelings using the yellow leaves, and this was again followed by group work to position the leaves on the Ketso felt. The procedure was repeated with the grey leaves, prompted by the question, "What are the challenges for development?" and the green leaves, prompted by, "How can we overcome these challenges?" Note that it may have been unclear to the teachers whether the "we" in this last question included the facilitator, who, as earlier stated, seemed to be viewed as a potential change agent. Towards the end of the article, we will pick up on this point, and more generally, what were the participants' expectations of the facilitator. Returning to the sequence of the questions, the focus on positive feelings before challenges was designed to enhance the participants' later identification of solutions. That is, "creativity can be inhibited by overly critical, negative thinking [and] this tends to limit people from seeing possibilities outside of the existing situation" (DE BONO, 1990, cited in TIPPETT et al., 2009, p.41). [26]

One thing that changed, as the session progressed, was that writing ideas on leaves that started as an individual task became gradually more interactive. Moreover, acting on her instinct as a qualitative researcher, ALABBASI encouraged the participants to voice any disagreements, and she asked follow-up questions: Why did you write this point? Can you explain this some more? Can you give me an example from your practice? In this respect, the Ketso session took on some of the qualities of a group interview, with the researcher adopting an investigative role (PARKER & TRITTER, 2006). However, individual participants retained control over, and continued to identify with, what they wrote on their own leaves. [27]

Next, the Ketso session moved to the second theme, which was "technology use" (the second main branch on the Ketso felt, see Figure 2). This followed the same sequence of individual writing on leaves and group work to sort the leaves into sub-themes (in this case: teacher, students and society). The teachers were asked to record "experiences of using technology in teaching, learning and socially" on brown leaves, "positive impacts and feelings" on yellow leaves, "challenges" on grey leaves, and "solutions" on green leaves. Starting this new theme helped to re-establish the "first individual, then more collaborative" pattern of activity, which is seen in the Ketso literature as an essential element to eliciting individual ideas and developing a group view of the situation (TIPPETT & HOW, 2011). Subsequent to this "reset" the session again gravitated towards a more interactive pattern. The researcher continued to ask follow-up questions as in the earlier part of the session. The following sections, including a more detailed analysis of the Ketso session, will exemplify these various individual and more collaborative ways of generating ideas. [28]

The Ketso session took approximately 90 minutes, and the data generated included the teachers' written leaves, the positioning of the leaves along the branches on the Ketso felt and, in clusters, the ideas perceived to be similar (photos were taken of the completed Ketso felt), the audio-recorded discussion, as well as field notes that the researcher completed immediately after the session. [29]

5. Exploring the Ketso Focus Group Session

This section shows how the Ketso session allowed for inclusive qualitative data generation. This includes discussion of how it: 1. enabled the voices of each of the participants to be heard, 2. allowed the identification of individual views, as well as similar views clustered on the Ketso felt, 3. in some cases, helped participants to extend their initial ideas into new shared ideas, and 4. encouraged participants to talk about what they felt was important, while avoiding the magnification effect (see the previous section). [30]

One challenge of focus group methodology is a tendency for more confident group members to dominate the discussion (CAREY, 1995; PARKER & TRITTER, 2006). Commenting on "standard" focus group methodology, ALBRECHT, JOHNSON and WALTHER (1993) suggest that participants can be asked to write their views in advance before the focus group session, thereby encouraging less confident members to participate more fully. Using Ketso, such writing by participants is a central feature and is built into the session activity, as opposed to happening before the session. Participants write their own ideas on differently colored leaves (or draw their ideas in the case of low literacy levels) before they are built into a picture of the group's thinking on the Ketso workspace. These phases of developing ideas before sharing them allows time for individual reflection. Moreover, all participants read what they have written to the group, thereby encouraging a more equal status in the subsequent interaction. Extract 1 illustrates this progression, with Lamia1) initiating the discussion by reading one of her yellow leaves (Turn 1; a positive impact of using technology). Ghada, who was a more dominant participant, agrees with Lamia's point (Turn 2). This is followed by the researcher prompting the group to expand on the point (Turn 3). This kind of prompt could have been an opportunity for more dominant participants to take over. However, in this Ketso session, the visual ownership of ideas—the leaves—discouraged the other participants from changing the direction of the discussion, and instead seemed to encourage affirming and extending types of comments from the other participants. This, in turn, allowed the participant that originally wrote the point on the leaf, in this case, Lamia, to use the other participants' affirmative and extending comments to develop her own point further. This is demonstrated in Extract 1, where Lamia extends on her own point in Turns 5 and 10. Hence, further discussion (extending also beyond the extract shown) was shaped by what Lamia wrote on her yellow leaf and with other participants (Sara, Ghada and Hanan) adding affirmative and extending observations in a manner that did not challenge Lamia's ownership of the point discussed. The result may be described as a nonjudgmental and cumulative form of interaction, with the participants adding to an accumulating set of ideas focused on the initial point written on the leaf. In addition to the "turn taking," the fact that there is visible representation of the others' ideas on the table, in the form of the leaves that have been written, means that participants can see that everyone has ideas and whether they have had a chance to share them or not. [31]

At a later stage, when the Ketso session moved on to discuss challenges (see Section 5.3), the discussion became a bit more critical, with participants voicing reservations about the use of social media such as WhatsApp. The use of different stages of questioning allowed for the issues to be considered from more than one angle—the positive and the negative—thus building nuance and understanding through the discussion.

Extract 1 [32]

Another way in which the voice of individual teachers was encouraged was through the support participants offered to each other during the individual writing stage. The teachers took writing on the leaves seriously, and from time to time, a participant struggled to express herself. The interaction in Extract 2 took place after the researcher asked the teachers to use the grey leaves to identify challenges. The extract shows how Sara struggled to express her view concisely (Turn 1). This quickly led to a number of suggestions from the other participants (including the researcher). The suggestions added up to a search for meaning, with everyone focused on helping Sara express herself. In the end (Turn 7), Sara explicitly confirmed she knew what to write (she eventually wrote: "wasting time in plugging," تضييع الوقت في التوصيل ).

|

Turn |

Speaker |

Focus Group Dialogue |

|

1 |

Sara |

How do I write this? Sometimes, while I am using technology, the computer stops working. It also takes me long time to plug the equipment, especially if the equipment is not hung from ceiling, for example. I am not sure how to word this. |

|

2 |

Researcher |

Do you mean plugging in the equipment in the classroom? |

|

3 |

Sara |

Yes, yes, in the classroom. |

|

4 |

Ghada |

Just write down "external circumstances" like "breakdown of a machine" or "electricity failure." |

|

5 |

Hanan |

... or write "lack of equipment." |

|

6 |

Solapha |

... or write "time wasted having to plug in the equipment." |

|

7 |

Sara |

Yes, that is what I meant! |

Extract 2 [33]

We need to comment on one further aspect of writing on the leaves. These brief statements seemed to privilege a focus on the "what" of the teachers' experiences. The leaves helped identify "what are the experiences" (brown leaves), "what are the positive impacts" (yellow), "what are the challenges" (grey), and "what are the solutions" (green). Qualitative research is, in addition, concerned with the "how" and "why" of experience. We can see (in Extract 1—Turn 3) that the researcher moved the discussion in this direction by asking, "How do you use technology to communicate with parents?" Again, this kind of follow-up question is what one might expect to see in qualitative individual or group interviews. We are not in a position to comment on how common such follow-up questioning may be when Ketso is used in participatory research (see earlier discussion). However, in the present case we see this kind of extending, through follow-up questions focused on the "how" and "why" of experience, to be a result of the particular use of Ketso as a tool in a qualitative research project. This follow-up was enabled by the physical representation of the earlier ideas on the felt—so that the questions could build upon and probe ideas around the "what." [34]

5.2 Identifying individual and similar views

The key feature of Ketso—of participants writing their individual ideas on differently colored leaves, and then together positioning and clustering them on the felt surface—generates data on individual views and views that are similar across participants. Moreover, by photographing the felt surface at the end of a session, a researcher will have a permanent record of participants' individual views, as well as how similar views have been clustered. [35]

In practice, the writing stage of Ketso was not without social dynamics, as we have noted above; hence, the written leaves were not individual views in a strict sense. Even so, the record of clustered individual statements, especially when viewed alongside audio-recorded data of the focus group interaction, provides unique affordances for further analysis by a qualitative researcher. Identifying shared views was not an explicit aim of the larger project in which the female Saudi teachers participated. The participants were asked to cluster similar views together, but as leaves were added to the felt surface over the 90 minute Ketso session, and with the felt surface looking increasingly crowded (see Figure 3), the clustering was not strictly enforced. However, with a photographic record of the Ketso felt, exploring the shared views retrospectively was possible. Table 1 illustrates this kind of analysis. The absolute frequency of views—the number of similar leaves—is, perhaps, of less interest to a qualitative researcher. However, this clustering of similar views, expressed as frequencies in Table 1, indicates a potentially shared overall view. That is, the clustering indicates the teachers knew technology could save time and effort (positive impact), they pointed out the cost to themselves of paying for the technology (a challenge), and held similar views about schools (and the government) needing to recognize the needs of students and teachers by providing (paying) for appropriate technology (a solution).

|

Stage |

View |

Frequency |

|

Positive Impact (yellow leaves) |

Saving time and effort (اختصار الوقت و الجهد) |

3 of 6 teachers |

|

Challenge (grey leaves) |

Financial cost for the teacher (الكلفة المادية على المعلمة) |

4 of 6 teachers |

|

Solution (green leaves) |

Providing technical equipment to cover the needs of students and teachers in the school (توفير أجهزة تقنية تغطي حاجة الطالبات و المعلمات) |

3 of 6 teachers |

Table 1: Common views about "using technology"

Figure 3: Part of the Ketso felt at the end of the session [36]

The discussion so far, and the fact that the Ketso felt may become very crowded with leaves (see Figure 3), indicates that a few ground rules may be needed if a qualitative researcher intends to explore similar views among participants in a Ketso session. For one, the number of themes and sub-themes may need to be limited, thereby reserving as much space as possible for the participants to neatly cluster similar views. It would also be useful to have participants mark their leaves with a unique identifier (e.g., their initials or a number or simple symbol, or to hand out pre-marked leaves to individuals) if the identification of unique individual views is important to the research aim (the retrospective analysis in Table 1 relied on recognizing the participants' handwriting). Finally, Figure 3 shows the use of a white-on-yellow tick mark that the participants used to highlight the most important or salient experiences they had (brown leaves), and a white-on-red triangle that they used to mark the most important/salient challenges (grey leaves). Just as with the differently colored leaves, the Ketso developers encourage individual project teams to develop their own locally appropriate uses for these additional markers. This provides additional affordances for qualitative researchers to generate data for understanding individual or shared views. [37]

5.3 Keeping the participants focused

In this section, we show how Ketso helped to keep the participants focused on what they thought was important, as well as how the features of Ketso helped avoid the pitfalls of the "magnification effect" (CAREY, 1995; see Section 3). [38]

We begin by showing how the teachers gravitated towards something they clearly liked to talk about. In Extract 3, the teachers are looking at positive impacts of using technology. Hanan has just read one of her yellow leaves ("improve the level of performance"; Turn 1), and the interaction shifts from this to Hanan's next yellow leaf ("collaboration between adults and children"; Turn 3). Here we can see "topic drift" (HOBBS, 1990); there is an opportunity to contrast what teachers might learn from their students ("Now, I like to search for new [software] programs to learn"; Turn 3), and what they might learn from official training events ("The other day we went to a training session"; Turn 3). Note how Hanan's "honestly it was..." at the end of Turn 3 is completed by Sara's "really bad" in Turn 4. Broadly speaking, there was a shared dislike of official training events, and Hanan proceeds to point out a problem with such training events (Turn 5). At this point, the discussion had drifted away from the focus on "positive impacts" (i.e., yellow leaves). Ketso gives the facilitator useful tools to manage a situation like this. In this instance, the researcher reminded the participants that the focus was on the yellow leaves (Turn 6), and quickly handed Hanan a grey leaf on which she could record her dissatisfaction with the official training (Turn 6). This ensured that Hanan would have a later opportunity to voice her grievance. The other participants were clearly in support of this systematic way of working (Lamia and Ghada, Turns 7 and 8), and the interaction quickly returned to the focus on positive impacts (Turn 9).

|

Turn |

Speaker |

Focus Group Dialogue |

|

1 |

Hanan |

I wrote "Improve the level of performance." I noticed that technology increased the sense of collaboration between us as teachers. If one teacher learns a new technology skill, she will train the rest of us in how to use it. |

|

2 |

Lamia |

Also, it decreased the gap between us and our students. |

|

3 |

Hanan |

Yes, Lamia and I learned something from one of our students. I wrote "collaboration between adults and children." Now, I like to search for new [software] programs to learn. The other day we went to a training session about using a specific program; honestly, it was ... |

|

4 |

Sara |

... really bad. |

|

5 |

Hanan |

We didn't take from it the outcomes that we were supposed to learn and achieve; all the trainer did was talk and talk. |

|

6 |

Researcher |

Okay Hanan, now you have started to mention training challenges. Take a Grey Leaf to write down the point that you just raised. We will discuss it in a while. |

|

7 |

Lamia |

Wait, wait Hanan ... |

|

8 |

Ghada |

Write it down Hanan ... |

|

9 |

Researcher |

Okay, what other advantages did you write down? |

Extract 3 [39]

Extract 4 is from later in the session, when the focus was on challenges (grey leaves), and sees the participants returning to the topic of official training events. Their shared dislike for these events may have contributed to the liveliness of the discussion, and we see early signs of the magnification effect (CAREY, 1995). Some of the contributions did include new information, but there is also repetition (italics in Extract 4). This repetition seemed to magnify the points made. Moreover, the use of "also" at the start of Turns 7 (Ghada) and 8 (Sara) shows an eagerness to add additional negative observations.

|

Turn |

Speaker |

Focus Group Dialogue |

|

1 |

Lamia |

... like "the training." You find yourself going to the training without benefiting from it. The trainers don't know how to deliver the information. |

|

2 |

Ghada |

Maybe the trainer is not qualified enough to give the training |

|

3 |

Lamia |

Yes, you find some trainers don't have the skills to deliver the information they are meant to be providing. |

|

4 |

Ghada |

They have to prepare good trainers to be able to deliver the information. |

|

5 |

Hanan |

Not everyone can train others |

|

6 |

Solafa |

On one occasion, I went to a training session, but didn't benefit from it because the trainer didn't know how to deliver the information to us. It was a waste of time. |

|

7 |

Ghada |

Also, the huge number of teachers at one training event. |

|

8 |

Sara |

Also the time that the training is held is not always suitable. We have our classes and curriculum to finish, and it is very bad practice to take a teacher out of the classroom to undertake training during school hours. |

Extract 4 [40]

Extract 5 depicts the interaction immediately following Extract 4, and it again shows how the researcher is able to draw on the features of Ketso to move the discussion in a positive direction (Turn 1); i.e., drawing the participants attention to the relevant green leaves for this challenge. This causes the participants to pause for a minute to read their green leaves and to reflect. When the discussion resumes, the critique of the training system does resurface again (in Turns 4, 5 and 7), but overall the shift to focusing on the green leaves leads to a shared effort to find ways forward to solve the challenges, or problems, that were identified with the official training events. The focus on finding solutions prompted by the green leaves was clearly helpful, presumably because the teachers had thought carefully about what to write on these leaves. Hence, the eventual agreed solutions were foreshadowed by these green leaves, which had recorded solutions such as: "providing online training," توفير دورات تدريبية عن بعد and "providing a mobile trainer," توفير المدرب المتنقل . We can see that the discussion gravitates towards the second of these solutions (Turns 8 through 12).

|

Turn |

Speaker |

Dialogue |

|

1 |

Researcher |

Okay, can you take a few minutes to think of a solution to this problem, by using the green leaves? (approximately one minute pause) |

|

2 |

Hanan |

To take advantage of these days when there are no students, we don't have too great of a workload. As we said, the training needs to be better planned. |

|

3 |

Ghada |

Yes, the solution is good planning. |

|

4 |

Hanan |

They also repeat the same training topics. We already know the content, so we don't want to go over it again. We want to learn something new, more practical. |

|

5 |

Lamia |

Yes, the training is very repetitive. |

|

6 |

Ghada |

The solution is to administer a survey to ask teachers what they want and need in the training. |

|

7 |

Lamia |

The Ministry provides a lot of training sessions to choose from in different disciplines. But go and see the training center; you will be surprised by the huge numbers of teachers at the session. Look, our colleague was there today; she said it was so crowded that she did not benefit from attending. |

|

8 |

Sara |

I suggest that the Ministry sends a trainer to each school instead of us going to the training center. For example, the supervisor could come to the school and train all the 45 teachers at the same time, instead of the 45 teachers leaving the school throughout the year to attend the training sessions. This would save time and a lot of effort and reduce the traffic through the training centers. |

|

9 |

Lamia |

Yes, I do agree, and the training can be tailored to different disciplines. |

|

10 |

Sara |

There will be a mobile trainer. |

|

11 |

Ghada |

Yes, a mobile trainer. |

|

12 |

Solafa |

... and this will reduce all the transportation problems as well. |

Extract 5 [41]

In sum, the researcher's strategic use of the differently colored leaves helped to keep the participants focused, avoided undue magnification of the teachers' dislike for the official training events, and moved their attention to a productive discussion of ways forward. It is not our intention here to suggest when, exactly, researchers should move participants along in this manner. That is a decision to be made in the moment by a focus group facilitator. Our point is that Ketso offers tangible ways to manage the forward progression of focus group interaction. [42]

We believe this analysis indicates the potential of Ketso as an inclusive data generation tool for qualitative research in a context such as that of Saudi Arabia, and possibly more broadly. It is inclusive in the way it provided all the female Saudi teacher participants with opportunities to develop and express their voices. This included individual time and reflection to generate written statements, as well as having these views systematically attended to in whole group discussion. Furthermore, the successive cycles of individual and group work provided repeated opportunities for all of the participating teachers to reflect and develop their voices. Importantly, it gave all the participants a fairly equal chance to be heard. [43]

The data generation potential of Ketso is further strengthened by the positioning and clustering of written statements on the Ketso felt by participants. This adds data points that a qualitative researcher may use, alongside other data such as audio recordings and field notes, in follow-up analysis and interpretation. Ketso's potential as a data generation tool for qualitative research is also enabled by how it can structure and progress focus group interaction. Our analysis showed how having a clearly delineated meaning for each of the differently colored leaves helped the facilitator to move the discussion forward, avoiding situations where the female Saudi teachers focused too narrowly on what they liked to talk about or falling into the interactional dynamic of the "magnification effect" (CAREY, 1995). Moreover, our exploration indicates that a focus on solutions—provided this is retained as the meaning of the green leaves—can encourage cumulative or collaborative development of future possibilities. This future orientation may provide a sense of purpose for focus group participants, adding an ethical dimension to the research gathering process, as the focus group is more likely to produce ideas that are of use to participants. Finally, the data generation potential of Ketso may be further enhanced by the use of follow-up questions that probe the "how" and "why" of participants' experiences, prompted by the ideas built by the group. [44]

We recognize a facilitator may shift the group interaction in ways that can compromise the inclusive qualities emphasized in Ketso's participatory origins. However, finding the right balance between control and freedom of participant expression is a common feature of qualitative data generation tools. That is, whenever a researcher is in interaction with participants, the competence and identity of the researcher is paramount. One critical competence of a focus group facilitator is the ability to adopt a nonjudgmental stance (EDGE, 1992), as this increases the likelihood of the participants being nondefensive in developing their voice. Related to this is the need for the facilitator to attend equitably to all of the participants' views. A facilitator may be tempted to pay selective attention to particular ideas (or written leaves), but this risks inadvertently alienating one or more of the participants. The success with which such a nonjudgmental stance can be developed is also affected by how the facilitator is perceived by the participants. In the present research, the combination of insider and outsider status of the researcher—the particular 'liquid identity' earlier described in the article—appeared to play a role in enabling the inclusive nature of the Ketso session. We hope this detailed description of, and rationale for, using Ketso with a group of female Saudi teachers may contribute to the development of the kinds of competence needed to facilitate Ketso focus group interaction. [45]

We also believe that Ketso was a positive experience for the female Saudi teachers who participated in this research. However, qualitative research using Ketso is only a first step in making the voices of female Saudi teachers visible. The next step is to explore the forms of change Ketso may promote. A first form of change is flagged by the participatory origins of Ketso. This is the suggestion that Ketso may raise the participants' awareness of their own capabilities to take local action, using resources available to them locally (TIPPETT, 1998). This local, on the ground, participatory focus of Ketso is, in part, a way to avoid overreliance on central authorities and systems. From this analysis of the Ketso interaction, we suggest that the method promotes sharing and listening to other teachers and, to some extent, thinking collaboratively about challenges and solutions. It is our hope that this experience may be translated into professional action, perhaps motivated by solutions developed in the Ketso session, or that it may manifest itself as an increased willingness by the teachers to voice their views in future professional encounters. However, to assess the extent to which the teachers' participation in the Ketso session may have had this impact and, perhaps, to reinforce any such impact would require going back to the teachers and asking them what their experience of the Ketso session was, what it meant to them, and what local action, by themselves, it prompted. Such longitudinal analysis and follow-up was outside the scope of the research reported here. [46]

That said, the participants in this study were already taking a great deal of action in their local settings. They worked extra hours, spent their own financial resources to pay for technological equipment, and used technology in creative ways to improve communication and pedagogy. Moreover, the challenges the teachers outlined in the Ketso sessions tended to involve areas of educational activity beyond their own immediate control, such as financial resources to procure technological equipment and training organized by central authorities. Thus, we suspect that the more important action to pursue is to make the teachers' views and suggestions visible to a wider set of stakeholders. In this regard, the fact that the Ketso facilitator, ALABBASI, was perceived as a change agent by the participating teachers, needs consideration. In fact, the female teacher participants gave clear signals that they wished policymakers and higher authorities to know about what they were going through, and expressed some expectation that ALABBASI, as a Saudi with knowledge of the educational system, would facilitate this. [47]

ALABBASI recently started a new academic post inside Saudi Arabia, and is beginning to take steps to make the teachers' views and suggested solutions known within the Saudi educational system. An initial action she took was to write an article, entitled "Education and Setting Priorities" in Albilad (ALABBASI, 2017), a widely circulated Arab language Saudi newspaper, using the insights from working with female Saudi teachers to critique the most recent education budget and associated initiatives by the ministry of education. ALABBASI is also setting up further meetings with groups of female teachers, similar to the teachers who participated in the original project reported on in this article. These meetings may include more targeted Ketso sessions that focus specifically on how to effect change, as earlier mentioned. Such additional Ketso sessions may also allow exploration of how and whether the tangible nature of the data collected by Ketso can add weight to attempts to increase the visibility of female Saudi teachers' voices, and how, then, Ketso may serve as part of a process of educational change. ALABASSI will also pursue additional publication in Saudi print news, and will use social media (e.g., Snapchat, which is widely used in Saudi society) to encourage teachers to share knowledge and ideas. Helped by her academic post, she will be engaging in active networking (online and in person) in various parts of the educational community, for making female Saudi teachers' views and suggestions visible. Finally, as this "larger project" progresses, it may be possible—as suggested by a female teacher—to organize Ketso sessions with policymakers (affiliated with or working within the Ministry of Education), directly focused on how to address the female teachers' concerns. [48]

In parallel, ALABBASI will develop her academic profile in a way that is visible and accessible to Saudi policymakers. This is to give her the necessary "standing" going forward, so to enable her to be an effective advocate for her female teacher participants. This will include making her dissertation available online and, where possible, opting for open-access journal publication (rather than journals requiring subscription fees, and hence less likely to be accessible in Saudi Arabia). Furthermore, there would be a need to write for professional and layperson audiences. This could include peer-reviewed journals affiliated with professional organizations, as well as overtly professionally oriented regional or local publications. [49]

Before we conclude, we wish to comment on how this contribution has been framed and how this relates to the Saudi Arabian context. We are conscious that we have used the participatory and feminist frames with some caution, and this caution may mean that this written version of the research may not fully benefit from the analytical and emancipatory potentially these frames can offer. For us, and especially ALABBASI who is a Saudi female herself, this has been a very deliberate strategy. On the one hand, the carefully calibrated references to the feminist and participatory frames has helped to position this research, including how we understand Ketso interactions and the data that this generates. Moreover, the participatory frame has helped to make transparent how we have used Ketso within the broader arena of qualitative research. We believe that despite uprooting Ketso from its origins, the present use of Ketso retains some of its "participatory DNA." On the other hand, we recognize that a more overt use of these frames would have enabled a more persuasive case for how influential female Saudi teachers can be, or how their experience may compare with Saudi males, women in other parts of the world, or (possibly exogenously defined) ideals of equality and empowerment. However, this might have led us to suggest forms of participation that are in tension with the traditional values of Saudi society. We see our decisions in this regard as an attempt to avoid, even if only by association, what AL-DABBAGH (2015) refers to as a "dominant Western representation of Saudi Arabian women." Our vision is for our contribution to be read by Saudis, in Saudi Arabia, as an authentic project that is sensitive to the cultural particularities of their context. We hope we have achieved this, with our central contribution being the use of Ketso to make visible the voices of female Saudi teachers' in research, and by outlining what further steps may be taken to make these teachers’ voices heard by the educational system more broadly. [50]

We want to thank Katja MRUCK and the anonymous reviewers of FQS for their feedback that contributed positively to the development of this article. We also want thank Joanne TIPPETT for her help in proof-reading and revising the article, and for her encouragement. Last but not least we want to thank the participants, the Saudi female teachers who were willing to participate in this research and who gave this study its strength and depth. Thank you!

1) All teacher participants' names presented in this article are not their real names. <back>

Al-Dabbagh, May (2015). Saudi Arabian women and group activism. Journal of Middle East Women's Studies, 11(2), 235-237.

Alabbasi, Dalal (2017). Education and setting priorities. ALBilad Newspaper, May 7, p.11, http://www.albiladdaily.com/author/dalalalbiladdaily-com/ [Accessed: April 12, 2018].

Alabbasi, Dalal (2016). The experience of Saudi female teachers using technology in primary schools in Saudi Arabia. PhD Thesis, University of Manchester, UK.

Albrecht, Terrance; Johnson, Gerianne & Walther, Joseph (1993). Understanding communication processes in focus groups. In David Morgan (Ed.), Successful focus groups: Advancing the state of the art (pp.51-64). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Bagnoli, Anna & Clark, Andrew (2010). Focus groups with young people: A participatory approach to research planning. Journal of Youth Studies, 13(1), 101-119.

Belenky, Mary Field; Clinchy, Blythe McVicker; Goldberger, Nancy Rule & Tarule, Jill Mattuck (1997). Women's ways of knowing: The development of self, voice, and mind. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Bergold, Jarg & Thomas, Stefan (2012). Participatory research methods: A methodological approach in motion. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 13(1), Art. 30, http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-13.1.1801 [Accessed: August 17, 2017].

Bivens, Felix (2014). Networked knowledge as networked power: Recovering and mobilising transformative knowledge through participate. In Thea Shahrokh (Ed.), Knowledge from the margins: An anthology from a global network on participatory practice and policy influence (pp.14-17). Brighton: Institute of Development Studies.

Bloor, Michael; Frankland, Jane; Thomas, Michelle & Robson, Kate (2001). Focus groups in social research. London: Sage.

Buzan, Tony & Buzan, Barry (1996). The mind map book: How to use radiant thinking to maximize your brain's untapped potential. New York, NY: Plume.

Carey, Martha Ann (1995). Comment: Concerns in the analysis of focus group data. Qualitative Health Research, 5(4), 487-495.

Czymoniewicz-Klippel, Melina; Brijnath, Bianca & Crockett, Belinda (2010). Ethics and the promotion of inclusiveness within qualitative research: Case examples from Asia and the Pacific. Qualitative Inquiry, 16(5), 332-341.

Edge, Julian (1992). Cooperative development. Harlow: Longman.

Furlong, Claire & Tippett, Joanne (2013). Returning knowledge to the community: An innovative approach to sharing knowledge about drinking water practices in a peri-urban community. Journal of Water Sanitation and Hygiene for Development, 3(4), 629-637, http://washdev.iwaponline.com/content/ppiwajwshd/3/4/629.full.pdf [Accessed: August 17, 2017].

Gilligan, Carol (1982). In a different voice: Psychological theory and women's development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Goodson, Ivor (1991). Sponsoring the teacher's voice: Teachers' lives and teacher development. Cambridge Journal of Education, 21(1), 35-45.

Hamdan, Amani (2005). Women and education in Saudi Arabia: Challenges and achievements. International Education Journal, 6(1), 42-64, https://openjournals.library.sydney.edu.au/index.php/IEJ/article/view/6792/7434 [Accessed: August 17, 2017].

Harrison, Karen & Barlow, Julie (1995). Focused group discussion: A "quality" method for health research. Health Psychology Update, 20, 11-13.

Hobbs, Jerry (1990). Topic drift. In Bruce Dorval (Ed.), Conversational organization and its development (pp.3-22). Norwood, NJ: Ablex Publishing.

Jamjoom, Mounira (2010). Female Islamic studies teachers in Saudi Arabia: A phenomenological study. Teaching and Teacher Education, 26(3), 547-558.

Kirk, David & MacDonald, Doune (2001). Teacher voice and ownership of curriculum change. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 33(5), 551-567.

Kitzinger, Jenny (1995). Qualitative research. Introducing focus groups. British Medical Journal, 311(7000), 299-302.

Luria, Aleksandr Romanovich (1979). The making of mind. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

McIntosh, Alison & Cockburn-Wootten, Cheryl (2016). Using Ketso for engaged tourism scholarship. Annals of Tourism Research, 56(C), 148-151.

Parker, Andrew & Tritter, Jonathan (2006). Focus group method and methodology: Current practice and recent debate. International Journal of Research & Method in Education, 29(1), 23-37.

Romm, Norma Ruth Arlene (2015). Conducting focus groups in terms of an appreciation of indigenous ways of knowing: Some examples from South Africa. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 16(1), Art. 2, http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-16.1.2087 [Accessed: August 17, 2017].

Ryan, Jane; Al Sheedi, Yahya Mohammed; White, Gillian & Watkins, Dianne (2015). Respecting the culture: Undertaking focus groups in Oman. Qualitative Research, 15(3), 373-388.

Sim, Julius (1998). Collecting and analysing qualitative data: Issues raised by the focus group. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 28(2), 345-352.

Thomas, Andrew (2008). Focus groups in qualitative research: Culturally sensitive methodology for the Arabian Gulf?. International Journal of Research & Method in Education, 31(1), 77-88.

Thomson, Pat & Gunter, Helen (2011). Inside, outside, upside down: The fluidity of academic researcher "identity" in working with/in school. International Journal of Research & Method in Education, 34(1), 17-30.

Tippett, Joanne (1998). Action speaks: Permaculture in Lesotho. Permaculture Magazine, 17, http://www.holocene.net/action_speaks.htm [Accessed: August 17, 2017].

Tippett, Joanne (2013). Creativity and learning—participatory planning and the co-production of local knowledge. Town and Country Planning, 82(10), 439-442.

Tippett, Joanne & How, Fraser (2011). Ketso user guide, http://www.ketso.com/sites/default/files/docs/KetsoGuide-Aug2012.pdf [Accessed: August 17, 2017].

Tippett, Joanne; Handley, John & Ravetz, Joe (2007). Meeting the challenges of sustainable development: A conceptual appraisal of a new methodology for participatory ecological planning. Progress in Planning, 67(1), 9-98.

Tippett, Joanne; Farnsworth, Valerie; How, Fraser; Le Roux, Ebenhaezer; Mann, Pete & Sheriff, Graeme (2009). Improving sustainability skills and knowledge in the workplace: Final project report. Manchester: Sustainable Consumption Institute, The University of Manchester,https://www.escholar.manchester.ac.uk/uk-ac-man-scw:153506 [Accessed: August 17, 2017].

UNESCO (2013). Adult and youth literacy: National, regional and global trends, 1985-2015. Montreal, Canada: UNESCO Institute for Statistics, http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0021/002174/217409e.pdf [Accessed: August 17, 2017].

Vygotsky, Lev Semyonovich (1978). Mind in society. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Whitworth, Andrew; Torras I Calvo, Maria Carme; Moss, Bodil; Kifle, Nazareth Amlesom & Blåsternes, Terje (2014). Changing libraries: Facilitating self-reflection and action research on organizational change in academic libraries. New Review of Academic Librarianship, 20(2), 251-274.

Whitworth, Andrew; Torras I Calvo, Maria Carme; Moss, Bodil; Kifle, Nazareth Amlesom & Blåsternes, Terje (2015). Mapping collective information practices in the workplace. In Serap Kurbanoglu, Joumana Boustany, Sonja Špiranec, Esther Grassian, Diane Mizrachi & Loriene Roy (Eds.), Information literacy: Moving toward sustainability (pp.49-58). Cham: Springer.

Winslow, Wendy Wilkins; Honein, Gladys & Elzubeir, Margaret Ann (2002). Seeking Emirati women's voices: The use of focus groups with an Arab population. Qualitative Health Research, 12(4), 566-575.

Dalal Omar ALABBASI, PhD, is an assistant professor in the graduate school at Dar AlHekma University in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, specializing in integrating technology with education. Her research interest is educational technology and the implications of technology in learning and teaching, as well as in social and political aspects of society. She is also interested in teachers' development, experiences and presenting teachers' voices, and the use of Ketso especially in the context of Saudi Arabia. Current research includes: using Mind mapping techniques in the process of evaluating students' satisfaction and feedback in higher education.

Contact:

Dalal Omar AlAbbasi

Graduate School

Dar AlHekma University

6702 Prince Majed

AlFayha District, Unit No.2

Jeddah 22246- 4872, Saudi Arabia

Tel: +966-12-6303333 Ext: 248

E-mail: dabbasi@dah.edu.sa

Juup STELMA is director of teaching and learning at the Manchester Institute of Education of The University of Manchester. He teaches courses on language education, as well as research methods in education and the social sciences. His research is focused on dynamical and ecological understandings of language education, research methodology, and researcher development, with a particular interest in how educational and research practices vary across linguistic, national and cultural boundaries.

Contact:

Juup Stelma

Manchester Institute of Education

School of Environment, Education and Development

Ellen Wilkinson Building, The University of Manchester

Manchester, M13 9PL, UK

Tel: +44-161-2753694

E-mail: juup.stelma@manchester.ac.uk

AlAbbasi, Dalal & Stelma, Juup (2018). Using Ketso in Qualitative Research With Female Saudi Teachers [50 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 19(2), Art. 15, http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-19.2.2930.