Volume 19, No. 3, Art. 3 – September 2018

Autobiographical Notes from Inside the Ethics Regime: Some Thoughts on How Researchers in the Social Sciences Can Own Ethics

Will C. van den Hoonaard

Abstract: The medical model of research ethics codes operates from a privileged perspective. The reaction of social researchers spans the broad spectrum, from deference to rebellion. In this contribution, I explore an approach that would yield a move away from adversarial relationships that have come to characterize the discourse between the upholders of the medically framed research ethics codes and those who see no relevance in those codes in terms of their own research. The path away from this adversarial approach is to maintain the institutionalized ethics codes for medical research, but to insist that researchers in the social sciences use their own well-established disciplinary codes for conducting ethical research. Once we have moved away from this adversarial relationship, researchers in the social sciences will have no need to "other" themselves in research ethics review; they can now own their own ethics in research. These views represent my autobiographical reflections from my position as a founding-member of Canada's Panel on Research Ethics as a qualitative sociologist with extensive experience who has participated in the debate since 2001.

Key words: ethics codes; medical ethics; social-science ethics

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

1.1 The medical model of research ethics codes

1.2 Composing a chapter on qualitative research

2. A Culture of Critique around Research Ethics Review

3. The Prestige of Medicalism in Research Ethics Review

4. Paternalism and Colonialism

5. Are Medical Ethics Codes Inhospitable to Social-Science Research?

6. The Importance of Reflecting on One's Research

7. Piecemeal Changes in Research Ethics Codes

8. The Formal Creation of Ethics Codes for Social Sciences

9. Abandoning any Formal Research Ethics Regulations

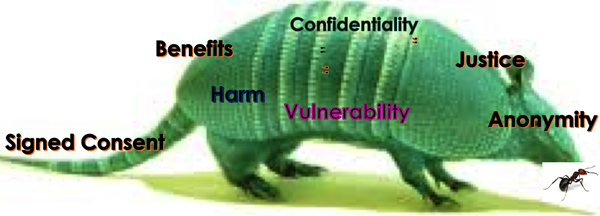

For some 20 years the rule of ethics regimes has grown by leaps and bounds around the world. In this article, I explore the elements of opposition and reconstruction undertaken by researchers in the social sciences that would allow the ethics regimes to be relevant to these researchers and their work. At this stage of the evolution of ethics regimes, one encounters a patchwork of approaches. [1]

Research ethics review is filled with paradoxes. The regime of ethics review has a fixed and permanent structure, but there are not many policy-making initiatives that are more subject to fads and fashions, temporary dislocations, and arbitrary decisions than research ethics review. We can trace its origins to medical research, but we now see it branched out to a large number of non-medical fields that includes cultural and social science research including narrative research, oral history, ethnography, linguistics, visual sociology, and more. Arrows that are intended to strike at the heart of this ethics regime are clothed as suggestions for minor, piecemeal changes. The whole regime leaves me and many others perplexed, wandering in the desert of research, and failing to find any familiar ethical disciplinary signposts. [2]

A significant ingrained impact of formal research ethics codes runs deeply into how researchers in the social sciences practice their work. Their range of methods has been curtailed, homogenizing their research topics and pauperizing their methodology (VAN DEN HOONAARD & CONNOLLY, 2006). The point is that typically in many Anglophone countries, it is the paradigm of medical ethics that govern research ethics in the social sciences, and that puts research in the social sciences at a disadvantage because the social sciences are not allowed to resort to using their own perspectives on ethics in their research. Distrusting the researcher runs as a central theme in the deliberations of many ethics committees (VAN DEN HOONAARD, 2011, pp.44, 106). [3]

Despite the promotion of medically based ethics codes in the social sciences, there are newly emerging sentiments about what might or might not work for researchers in the social sciences. Martin TOLICH, for example, has been experimenting with different modes of research ethics review in New Zealand, including a volunteer program of sorts (MARLOWE & TOLICH, 2015). He has moved across the spectrum—and he came to our Ethics Rupture conference in 2012 (VAN DEN HOONAARD & HAMILTON, 2016) where he contributed to the deliberations, leading to creating the New Brunswick Declaration on Research Ethics. The Declaration averred that ethics committees should treat researchers with the same respect as the committees expect researchers to treat research participants. [4]

1.1 The medical model of research ethics codes

The medical model of research ethics codes operates from a privileged perspective. The reaction of social researchers spans the broad spectrum, from deference to rebellion. I explore an approach that would yield a move away from adversarial relationships that have come to characterize the discourse between the upholders of the medically framed research ethics codes and those who see no relevance in those codes in terms of their own research. The path away from this adversarial approach is to maintain the institutionalized ethics codes for medical researchers but insist that researchers in the social sciences use their own well-established disciplinary codes for conducting ethical research. Once we have moved away from this adversarial relationship, researchers in the social sciences will have no need to "other" themselves in research ethics review (VAN DEN HOONAARD, 2017a). [5]

Research ethics codes are now present in numerous universities around the world. Their legal or mandatory status allows them a free hand to dictate the ethical requirements of research. The source of the difficulty is that the prevailing ethics regulations are based in medical conceptions of ethical research. Steve OLIVIER and Lesley FISHWICK (2003, §3), among others, "debate the applicability of the commonly applied biomedical ethics model for qualitative research, and take the perspective that judgements cannot simply be applied from a positivist perspective." Research in the social sciences and even some in the humanities are governed by these same codes. The reader should have no fear that I will disparage medical research ethics codes; medical researchers themselves have adequate means to adjudicate any problems surrounding their own conceptions of ethics in their research. By way of analogy, the medically based perspectives on research are the cathedrals while the social sciences inhabit the nearly invisible local corner store. Occasionally, a frustrated social scientist from the corner store throws a rock at a stained-glass window, but the cathedral remains standing. [6]

1.2 Composing a chapter on qualitative research

During my brief tenure as founding member of the Canadian Interagency Panel on Research Ethics,1) I never realized how pervasive the power of medically oriented research ethics codes is in taking ownership away from the social sciences of their own ethical conceptions of research. Researchers in the social sciences were persuaded to believe that their approach to research ethics was either insufficient or inappropriate. Still believing that it was possible to integrate social science ethics into the medical framework of ethics, the Canadian Panel on Research Ethics asked its Working Group on the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Ethics to compose a chapter on qualitative research to be incorporated into the Tri-Council Policy Statement on Research Involving Human (TCPS2). I was both enthusiastic and eager to develop such a document (which eventually became Chapter 10 in TCPS2). It was probably thought that qualitative researchers represented some of the noisiest complainers about the Tri-Council Policy Statement on Research Involving Humans. After all, they used ethnography, narrative research, and research that relied heavily on reflection and other approaches that stood outside of the conventional medical research ethics paradigm. Still, by having a special chapter on qualitative research, the "rest" of the social sciences was left captive in the hands of research ethics as conceived from a model of doing medical research. [7]

I now realize that the actual placement of Chapter 10 in TCPS2 may have had the unintended effect of leaving researchers in the social sciences still in the embrace of medical ethics. The first eight chapters of the TCPS2 are so thoroughly grounded in medical ethics that any questions about ethical research would naturally gravitate towards medical ethics. From my conversation with researchers in the social sciences, it seems that they are not so alert to Chapter 10 as they should be; they hardly know it exists. Chapter 10 offers a different model of ethics in research. As it turns out, the placement of qualitative research as Chapter 10 of TCPS2 would also lead research ethics boards in Canada to believe that all guidelines about research ethics could be found in the main chapters preceding that particular chapter. This gravitational pull exercised a significant influence in the formation of ethical concepts by both researchers and research ethics boards in Canada. [8]

The following sections underscore a number of elements in research-ethics codes that evokes a culture of critique around research-ethics review. I also draw attention to the prestige of medicalism with its emphasis on promoting quantitative concepts with their inherent paternalistic and colonial assumptions. The next section, I argue, suggests that medical ethics codes inhospitable to social-science research. While the next section avers that it is important to reflect on one's research, the final sections consider the advantages and disadvantages of piecemeal changes in research ethics codes, the formal creation of ethics codes for the social sciences, and, finally, the abandonment of any formal research ethics regulations. [9]

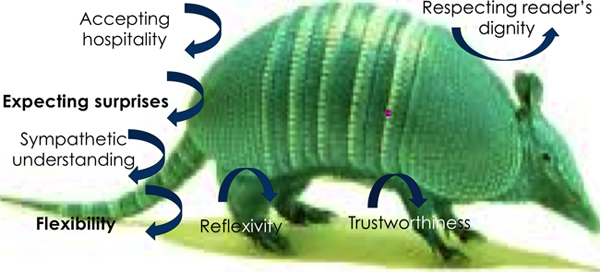

2. A Culture of Critique around Research Ethics Review

Research ethics review has become an industry. It is a practice that I would estimate at costing $500 million per year around the world. SPECKMAN et al. (2007) estimated a cost of $443,822. WHITNEY and SCHNEIDER (2011) estimate a higher cost, namely $1,359,596 per IRB. Thus, in the United States alone, the IRB system costs an estimated $45 million/year. This figure does not include the holding of national and international scholarly workshops on research ethics.2) [10]

Researchers have developed a culture of critique around research ethics review. My personal bibliography (regularly made available through ResearchGate) includes these critiques and shows a sum total of nearly 940 authors who have produced over 840 articles and some books. My collection of papers pertains to those appearing in the English language: Indeed, the main thrust of these criticisms comes from the imposition of ethics codes in Anglophone areas. One might say that there are 44 scholars who, sometimes as first authors, have significantly contributed to this discourse. Of these 44, I would aver that six have firmly left their mark on the field during the whole course of the debate since before 1998 to the present. Another nine or so already seem in line to contribute to future debates on the topic. It is also clear, however, that many others have become fatigued by these struggles, or simply retired. [11]

More significant for researchers in the social sciences is the question of the future pathway of ethics in social science research. Should we as social scientists formally and unhesitatingly adopt the pre-eminent model offered by our medical colleagues as our own? Or, should we engage in piecemeal changes so the ethics regime will be more suitable for the social sciences? Or, should we formally create our own system of research ethics review? Or, finally, should we abandon altogether any formal system of research ethics review and follow the lead of journalists? Which of these possibilities represent the best way to resolve the current adversarial relationship? [12]

3. The Prestige of Medicalism in Research Ethics Review

Why do these codes occupy such a very privileged status in the ethics adjudication of research in all fields—even beyond medical research itself? We all know the original history of accentuating the need for ethics in research highlights the faltering of medical research, whether Tuskegee Experiment, Chester SOUTHAM's cancer cell injections in the Jewish Chronic Disease Hospital, Saul KRUGMAN's hepatitis experiments at the Willowbrook School, and, in the UK, the work identified by Maurice PAPPWORTH as abusive. Interestingly, social scientists consider the MILGRAM study of obedience and the ZIMBARDO experiment as falling outside of what social scientists do: they were psychological experiments (for a historical discussion of some of these experiments see the contribution by YANOV & SCHWATZ-SHEA, 2008). And while there were a few moments in social-science research that quavered ethically speaking, they were very few. The ethical lapses in medical research led to an outcry to establish formal rules. [13]

The Belmont Report was the outcome of such an outcry. The committee charged with developing the Belmont Report included many high-profile researchers in the medical field, mostly men. There is not much in their work that resonates in a compelling way with the social sciences. It focused on research on the fetus, prisoners, children, psychosurgery, the institutionalized mentally infirm, and delivery of health services. Developing ethics policies for all medical researchers was deeply ingrained in the fight against racism, especially in the selection of human subjects. [14]

The Belmont Report formally reiterated the canons of ethical research in medicine: respect for persons, beneficence,3) and justice. These canons involved the need to seek informed consent, maintain confidentiality, do no harm, pay attention to vulnerable individuals, and attach the notion of justice when selecting research subjects, both to spread the risk, but also to ensure that many could benefit from the research. These concepts, to many bystanders, including those charged with overseeing research make eminent sense. The privilege accorded to medical researchers makes the codes more prominent and very acceptable. [15]

The author of the Belmont Report was the 1974 Belmont Commission (NATIONAL COMMISSION FOR THE PROTECTION OF HUMAN SUBJECTS OF BIOMEDICAL AND BEHAVIORAL RESEARCH, 1978). It was composed of eleven members: three MDs, one biologist, one social activist, one from the field of bioethics, three attorneys, one trained in Christian ethics, and one psychologist.4) The 26 authors of Belmont Report reflected the composition of the national commission (in addition, another 100 people provided comments): ten MDs, two legal experts, four philosophers, five psychologists, two sociologists, one policy analyst, and one of unknown professional identity,5) one woman and 25 men. The two sociologists represented mainstream research: Bernard BARBED at Harvard studied the science of warfare, government, education, industry and power (RESTIVO & DOWTY, 2008). His mentors included Talcott PARSONS, Robert MERTON and Pitirim SOROKIN—all giants in the field of science who would have loved no better than sociology's being affiliated with scientific medicalism. Albert REISS had an international reputation, starting with a study of police behavior. He was frequently associated with the National Institute of Justice. [16]

Carrying the weight of status and prestige, medical ethics codes did not require any further evidence of their usefulness or defense. It was self-evident from the very beginning. These ethics codes enshrined ethical principles that seemed "to make sense." To deviate from those principles was heresy and counter-intuitive. The self-protective nature of medical research ethics codes resembles the armor of an armadillo (Figure 1).6)

Figure 1: Ethics Armadillo A [17]

With such universal acceptance of these codes, one may well conclude that these (medical) research ethics codes have colonized research ethics in virtually all fields. The colonizing aspects are so pervasive that medical-research discourse has supplanted those terminologies that were prevalent in the social sciences and the humanities: "protocol" instead of "research plan," "rigor," "research study" instead of "study" or just "research," and "investigator" instead of "researcher." I strongly suspect that we can attribute the resorting of these medical terminologies to the vast increase in the social sciences of health research. The term "justice" has no equivalence in social research. Terms like "generalizability" and "hypothesis" represent a quickly diminishing corner of qualitative social research.7) Strange as it may seem, even such terms as "informed consent" is not part of our lexicon although it is hard to conceive of most social research without the explicit involvement and cooperation of research participants in research. These are terms that medical researchers are so intimately familiar with that they take them for granted. The power of these terms is like the armor of the armadillo (Figure 1). The concepts are tightly woven into the fabric of contemporary ethics codes. Together, these ethics codes constitute the Trojan horse that brings quantitative research into the fortress of qualitative research. Quantitative research brings in positivism and implies a deductive approach. Qualitative health research disavows positivism and advocates an inductive approach. [18]

The concepts of needing a signed consent form, of research producing benefits, avoiding harm, maintaining the confidentiality and anonymity of research subjects, promoting justice in terms of everyone's having the same probability of being chosen as a subject, considering the vulnerability of research subjects, are all issues that find resonance and agreement in society, at least on the surface. The following paragraphs summarize some essential differences between medical ethics and social-science ethics. I do not wish to elaborate too long on those differences: many researchers are familiar with them. [19]

Over the past 15 years, there are some 40 scholars, such as Kirsten BELL (2014, 2015) and Charles BOSK (2001), who have demonstrated the awkward and counter-productive uses of signed consent forms. Several issues pertain to the question of confidentiality, and even consent forms. While research ethics committees insist on researchers' maintaining confidentiality, police agencies and companies know the existence of consent forms and therefore often want researchers to surrender their confidential findings. In Canada, there have been two instances where authorities, through the courts, demanded researchers surrender confidentiality. Russell OGDEN (2004; see also LOWMAN & PALYS, 2014) was engaged in seeking out cases involving euthanasia. In another case, this time in Quebec, the courts were seeking the confidential records garnered by a researcher pertaining to crime (ANONYMOUS, 2013). To the relief of the researchers, these cases were thrown out of court. Anonymity suffers a different fate. As a rule, ethics committees take pride in advocating anonymity as a deeply held principle in research. In practical terms, anonymity becomes an impossibility in actual field research settings (VAN DEN HOONAARD, 2003). A researcher's visit to homes in villages or small towns quickly becomes known throughout the setting. I recall doing research in one Icelandic home when the next day, while I was interviewing someone, that person informed me what kinds of things the earlier person had told me (VAN DEN HOONAARD, 1972, 1992). To make a point, an Icelandic author, Guδmundur DANIELSSON (1972) incorporated my fieldwork in a south Icelandic fishing village into his novel about that village. Apparently, according to a recent source, only a few villagers were annoyed, some dismissed their mention in the novel, while others saw it as another form of light entertainment during Iceland's dark winters.8) [20]

The question of "benefits" is more difficult to dismiss as an integral part of research. The term evokes a high value, but in the context of medical ethics codes, it has a narrow and specific meaning. The codes in the context of medical trials strongly suggest that the research must benefit society. Many social scientists would not disagree with the assertion of benefits-producing research, but in the world of the social sciences, it is more challenging to predict how research can produce immediate benefits. What kind of benefits would compare the changing roles of airline flight attendants in the current security-prone institutions with earlier times bring (SANTIN & KELLY, 2017)? The two authors examined the emotional culture of flight attendants 32 years after Arlie Russell HOCHSCHILD's (1983) study, "The Managed Heart." Flight attendants are now more empowered and more assertive by institutional changes in security policies. Safety procedures over courtesy are now the norm. [21]

The notion of justice is also one that appeals to the trustees of research ethics regimes. It is intended to spread both the burden and benefits of research. Everyone has an equal random chance of being selected as a subject: women have an equal chance as men to be selected as subjects. This chance, however, becomes awry in social research. Would Deborah VAN DEN HOONAARD's (2001) social research on widows have to include men? Would the study of a men's biker gang (see, e.g., WOLF, 1991) have to include a women's biking group? [22]

Under the umbrella of what constitutes benefits, there is no agreement that even sharing findings from one's narrative research will benefit those for whom the research was done. ALLEMANN and DUDECK (2017) shared their experiences about "bringing back" stories to an Arctic community in Russian Lapland that dealt with boarding school experiences. They had to gingerly protect any stories that might have revealed intimate details present in those stories. [23]

4. Paternalism and Colonialism

The notion of harm was inherently attached to the physical harm borne by subjects in medical research. Closely allied to harm is vulnerability. Since then, the term has catapulted into several other realms, namely emotional, social, and cultural. What has stayed, however, is the paternalism that has guided decision-making by ethics committees (GARRARD & DAWSON, 2005). More particularly, the paternalistic decision become de rigueur when research subjects involve children, old people, the disabled, captive populations such as prisoners, sick folks, Holocaust survivors, and so on. The paternalism persists despite research that shows that people are far more resilient and able to cope with harm than imagined. Nancy CAMPBELL co-wrote an article with Laura STARK (2015, p.825) on the imaginary qualities attached to being vulnerable that affected people's self-understandings "while foreclosing paths of historical inquiry and interpretation." Mark CASTRODALE's research (2017) shows that disabled/vulnerable people want to be interviewed and treated in the same manner as "normals" and should not encounter ableist exclusionary research practices. There appears to be "a need to critically (re)consider space and place in research practices in ways that value the subjugated voices and socio-spatial knowledge(s)" of disabled persons (p.45). The conceptions that researchers have of vulnerable or disabled people vary considerably from those held by these people and their friends. [24]

Haily BUTLER-HENDERSON, 23, a Toronto woman with spina bifida who walks with forearm crutches, was meeting a friend for drinks at the Pentagram Bar and Grill on 19 August 2016 when she asked to use the washroom, but an attendant at the bar refused her access because the washroom was in the basement and the bar did want to be held liable in case she fell down the stairs. Hailey left, but walked back inside "towards the washroom kind of hoping [the attendant] wouldn't notice, but she did and jumped in front of the stairwell and got in my face." She did get to use the washroom, but "the experience was enough for her to pursue a human rights complaint against the bar ... [u]nder Section One of the Ontario Human Rights Code, [where] everyone has the right to equal treatment with regard to goods, services and facilities without discrimination on the basis of disability" (BROVERMAN, 2016, p.1). The case of Haily BUTLER-HENDERSON and the judgment of the Ontario Human Rights Code demonstrate the growing sense in society that the so-called "vulnerable" people want to see themselves as "normal" while medical research ethics codes still highlight "vulnerability" as a key factor when considering certain research subjects. [25]

These experiences illustrate the role medical research plays in the life of research ethics review systems. We can well assert that the codes have exercised a colonizing influence on research on the social sciences. But in what ways does medical ethics differ from ethics in social science research? [26]

5. Are Medical Ethics Codes Inhospitable to Social-Science Research?

Let us explore some of the key ideas in social research. WILLIAMS (2017), in his research on teenagers and suicide notes, beautifully sums up ethnographic research:

"The ethnographic approach and perspective is a personal art form, requiring integrity, stealth, perceptiveness, improvisation, courage, and compassion. Ethnography provides a way for people to tell their stories and for the ethnographer to interpret those stories in a way that renders the participants human. It is a sensitive method, in which the researcher tries to see the world as other people see it. Because ethnography involves attempts to provide a detailed portrait of people in their own settings through close and prolonged observation, [one] also spend time in the life of the neighborhood, learning about its peer groups, its informal organization, and its social structure as opportunities arises during the course of daily life (p.xxiv)." [27]

As sketched here, Figure 2 represents some of the ways that research in the social sciences is incongruous with those in medical research. Not all of the issues that cannot penetrate the armadillo are characteristics shared by all research in the social sciences.9) They merely highlight a few examples that researchers expect to practice while doing interviews, or participant observation, field work, focus groups, data analysis, narratives, or oral history, and so on. A number of these practices are held in conjunction with each other, making it more difficult to arrive at a template of research virtues. [28]

Embedded in the armadillo's shell are "protocol" and "subjects."10) These terms do not typically define the work of social science researchers. No doubt, there is some research that employs these positivist terms, but they may do so out of deference to the ethics committee that is more acquainted with those terms. The term protocol invites the researcher to stay the course, to plan something and find data that cannot be subject to interpretation. "Subjects" is a more common term in medical research but is seldom-used term in social research where "participant" is a more frequently used term. In social research, it is the researchers, especially ethnographers that see the research participant as the more powerful in the research relationship, certainly not the researcher.

Figure 2: Ethics Armadillo B [29]

Much of the research in the social sciences involves human relationships, especially when conducting fieldwork and related methodological perspectives. Accepting hospitality, for example, is a key question when it comes to strengthening the bonds of human affection. Showing up as promised conveys a respect for the dignity of the research participant and instils trustworthiness. These ingredients alone make the researcher stand out in good faith and give the research participant confidence in the purpose and results of the research. Contrary to what Wesley J. SMITH (2001, p.5) of Oakland, California, observed in medical trials, namely that "patients themselves continue to cling to the doctor as a professional rather than as a ‘resource' like drowning persons cling to a life raft," social scientists and research participants have an entirely different relationship. [30]

6. The Importance of Reflecting on One's Research

Because the researcher's notions will inevitably bump against previously held positions or approaches, it is essential for the researcher to reflect deeply on one's work and data-gathering exercise. Reflexivity not only entails thinking deeply about one's own attitudes and behaviors, and but also about the data one has collected and what new directions may unfold in the research. As VON UNGER, DILGER and SCHÖNHUTH (2016) already noted, qualitative researchers find it far more relevant to promote flexibility and ethical reflexivity than to introduce the guidelines of ethics review boards. Some researchers must wrestle with the idea of being a critical sociologist and how that idea measures up against the notion of the extent to which the researchers "represent" the research participant. What seems paramount for researchers in the social sciences is to view research participants as equals. Moreover, it is acceptable for research participants to show emotions. Researchers in the social sciences are not in the business of fixing the person, but ultimately to fix the system.11) [31]

More to the core of one's research as a sociologist is the relationship one holds to the research itself. Who are the funders of the research and what does that imply for the research? Does the researcher's commitment to the topic lead him or her to be a spokesperson for the group and individuals under study? Is the researcher aware that research participants see him or her as the source for explanations? How well can a researcher suss out the difference? Will the researcher, in the end, become a public relations cog? [32]

More to the point (and particularly in critical research), the ethical extension of enquiry touches on the tone and manner of writing up one's findings (VAN DEN HOONAARD, 2017b). The art and aim of good writing in this instance is to leave the dignity of the reader intact. While being persuasive, the researcher must allow readers to make up their own mind. This form of disciplined writing cannot be abandoned just because of a researcher's fervent belief in the findings. After all, the endpoint of critical enquiry is not the researcher's own analysis, but the manner of how to convince the reader of one's assertions or findings. The dignity of the reader means that the researcher must leave enough room for such independent assessment of the enquiry and its findings. This situation became quite apparent to me (VAN DEN HOONAARD, 1987) when I read an ethnographic study about the seal hunt near Newfoundland (Canada). The ethnographer (WRIGHT, 1986) was detailed and convincing in his findings, and would have had me on his side of his argument, except that towards the final stage of his book he started to castigate those who were against the seal hunt. In that one, brief section of the book, he "kidnapped" my own judgment, leaving me no choice to make up my own mind. Falsifying data does not constitute the unethical crux in social research as it does in medical trials because social data implicate a complex order of things: some are embodied in varying social and personal contexts (including the researcher's!) and are collected, interpreted, and analyzed in admittedly inductive and labyrinthic styles. Data are not merely "facts." [33]

It is not possible to develop a whole catalogue of terms that do not fit the biomedical paradigm our armadillo rejects or is unfamiliar with. When one diligently follows the training courses in these varying fields of research, a larger plethora of other distinctive terms open up. The medical armadillo does not capture all of these terms. The history and practical purposes of all concepts that originate in medical research are all well-reasoned out by speaker after speaker; there is no room left for additional concepts to fill the armory of medical research ethics. [34]

7. Piecemeal Changes in Research Ethics Codes

Whether deference or rebellion, social researchers react in many ways to the imposition of mandated research-ethics review. A historical frame contextualizes the reaction by researchers in the social science. Faced with the emerging legal or mandatory structure of how to conduct ethical research, social researchers have scoffed at that structure, have rebelled against it, or were determined to make peace with it. Some see rebellion as praiseworthy—a virtue in its own right. But the rebellion had to be muted. After all, one did have to go through an ethics committee to qualify for a grant. And, in Canada, the researcher who tries to conduct research without ethics review may put the funding of every researcher at the university at risk. Thus, many of the criticisms are couched in the language and terms of piecemeal changes, pulling at this or that to make the ethics provision fit one's particular discipline. For the past 20 years, over 800 articles and some books represent the criticisms or make suggestions for improvements. Many criticisms are empirically and factually real, but they are lodged in the debate of how one can "reasonably" take small detours from the principal ethics road. [35]

Given the diverse interpretations of ethics codes by research ethics boards, and even the diversity of social science methodologies, it became a difficult task to spell out how medical codes could serve social scientists. There have been numerous attempts. Granted, some boards have accommodated researchers in the social sciences, and some researchers have been able to articulate their specific ethics contours using the language and concepts already promulgated in the research ethics codes. But, on the whole, this was a highly unsatisfactory solution. New chairs of ethics committees, novice researchers, and the arrival (and disappearance) of ethics-review fashions resulted in inconsistencies across the board (ABBOTT & GRADY, 2011). [36]

A significant ingrained impact of formal research ethics codes ran deeply into how researchers in the social sciences would practice their work. As mentioned earlier, the range of methods has been curtailed, pauperizing the methodology. The range of topics became limited because the criteria for approving topics of research were circumscribed by such notions as safety, perceived vulnerability of research participants, and legal liability, and so on, thereby homogenizing diverse research topics (VAN DEN HOONAARD & CONNOLLY, 2006). A third major impact includes sending social researchers back into the chains of positivist research. No less significant is the widely held belief that "ethics committees may be distorting or frustrating useful research," leading to a culture of "mindless rule" (ALLEN, 2008, p.105). Moreover, chairs of research ethics committees would play a heavy role in helping those who were applying for "ethics approval" to select "appropriate" methods of research—in some cases, the heads of REBs became de facto informal supervisors in the conception of the methodology to be used by the student. One could argue that all of these elements of research ethics review would lead new researchers in the social sciences to forget the rich histories of their own discipline. [37]

When early proponents committed their thinking to make ethics review work, they were at a fairly early stage of research ethics review. They sensed the discrepancies, but there was no overarching sentiment to outright reject the (medical) ethics codes. It was all so new. Following a widely held axiom, Simon WHITNEY reasons that because ethics committees believe the scientist's interests run counter to the research subject's. According to WHITNEY (personal e-mail communication, November 24, 2017), this distrust is not only why ethics committees disregard what the researcher says, "but seem inclined to assume the opposite, and in any case are anxious not to yield a millimeter, since they believe that they care about subject protection and the investigator does not." "One of its unpleasant consequences," as WHITNEY (ibid.) further avers, "is the inclination of ethics committees to be brutal with scientists." I have often the statement, "trust, but verify" a near-universal sentiment shared by ethics committees across Canada. [38]

But as time has moved on, some veterans are becoming impatient, while the novices still sleepwalk into research ethics review (although they do get a rude awakening), often relying on procedural templates. As social researchers are discussing "new" ethics concepts, it is difficult to get past the armadillo of medical ethics concepts. Some researchers such as McGINN and BOSACKI (2004, §45), however, advocate the idea (and goal) in graduate research courses, that the struggles and questions of students should hopefully indicate that "they were beginning to develop virtuous research habits on an individual and a collective basis [and] to explore their responsibilities as researchers and critically reflect upon matters of intellectual freedom and moral judgment." Moreover, McGINN and BOSACKI (§45) found that "[m]any students were aware that they were caught between the, often contradictory, expectations of themselves as morally responsible researchers and the demands of institutional and professional guidelines." [39]

8. The Formal Creation of Ethics Codes for Social Sciences

Facing the difficulty of integrating medical and social science conceptions of ethics in research, one might consider the establishment of a separate regime for the social sciences. If that were possible, it would go a long way towards dismantling adversarial relationships. Each perspective might possibly find security on its own side. I argue that even with the creation of a separate regime for the social sciences, it is not possible to safeguard the integrity of social science research. The next paragraphs explore the role and functioning of ethics committees as problematic and look into the usefulness of professional codes and membership in the relevant associations as a step in the right direction. [40]

Research on the functioning of ethics committees does not hold much promise in terms what they can deliver as nurturers of ethical researchers. The research ethics committees themselves are honored with the privilege of scoping research proposals—and rejecting them or delaying their approval. The novices on these committees find themselves in good company: other respected researchers, astute and seasoned administrators, buttressed by the institutional devotion to formal, powerful, legitimatizing rules. It is common now to have researchers always include in their research posters, their publications, and other work, the statement, "This research has been approved by the University Research Ethics Committee," but it simply confirms the power and authority of the ethics regime. All these routines developed over several decades served the idea that the "best" ethical solution has been found. For researchers to follow those routines means that their applications carry a higher degree of approval.12) [41]

9. Abandoning any Formal Research Ethics Regulations

But, here is the rub: the diversity of social scientific methods and topics beyond medical research prevents critics from making for a uniform system of protest and criticism of research ethics review. In short, there is no social-science template that can serve all social scientists, who find themselves in a cross current of career goals. Scott BURRIS (2008) offers us three approaches to regulatory reform. We either recognize the limitations of research ethics committees as an oversight body, or we narrow the range of risks the system is tasked to control, or we disentangle "the conflicting regulatory logics of behavioral standard-setting and virtue promotion" (p.65). Others, like Dale CARPENTER (2006, p.699), also favor modest reforms, expecting such changes occurring in the membership and structure of ethics committees, in altering substantive IRB jurisdiction, and institutional liability. He is, however, very pessimistic about disbanding the ethics-review system for the social sciences. He avers that, a more radical series of proposals—like ending IRB supervision of social science research not involving physical risk to human subjects or even eliminating IRBs altogether—might be sound in principle, but they seem unlikely to be adopted given the bureaucratic momentum behind the regulation of research. For all of its inherent political and bureaucratic inertia, I am still in favor of disentangling the system. [42]

The contemporary urge to use "templates" denotes a tempting, but facile solution when dealing with complex issues. The fast-food chain uses templates to cook its two dozen varieties of hamburgers. Airplanes rely on a template to land aircraft. Hotels resort to using a template in every step of their operation, from registering guests to keeping rooms clean. There are templates for handling calls from irate customers. And ethics committees use checklists. Many conferences initially resort to using a template that organizers best abandon if they must deal with the needs of the program and of the mostly bizarre conference participants. Templates may have the effect of deskilling, taking away the power of imagination and thinking for oneself. The template of research ethics review cannot be easily cast aside: the prestige of medical ethics codes and the mandates that are attached to those codes make it quite impossible to abandon it at the whim of a complaining social scientist, even where more have joined the choir of complaints. Still, I believe the time has come to strip the medical ethics codes of their colonizing influence and let each field be guided by its time-proven and time-tried professional or academic ethics codes. It is time for researchers in the social sciences and the humanities to make a covenant with the ethics codes within each of their associations and professional associations. [43]

It might be instructive to take the example of the Netherlands as their chosen means to control floods. Rather than creating water barriers to protect the land from occasionally rising water levels, they create flood plains that are consistent with the realities of the actual flow of water. Similarly, it would be far more effective (and less costly) to introduce an ethics course entirely meaningful for the social sciences. Put in other words, rather than having a weight-measuring scale in your home, why not get rid of the scale altogether and learn about eating healthier foods? The scale of ethics in medical research cannot be used to measure the ethics in the social sciences. Why not try healthful ethics education? [44]

In the final analysis it is important to remember that we are not seeking to decolonize the medical research ethics codes themselves. We leave them intact. Rather, we seek to decolonize the research ethics review system itself so that the social sciences can find again their own voice in ethics. [45]

A many-year exchange with Simon WHITNEY of the Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas, has sharpened my understanding of ethics in research. I am grateful for these numerous exchanges. This paper is revised from the one that was presented as "Moving Away from Adversarial Relationships: The Strength of Diversity in Research-Ethics Review" at the International Scientific Workshop. University of Haifa, Israel, December 7, 2017. I also extend my appreciation to Wolff-Michael ROTH who worked through the initial digital and other problems of this manuscript. A number of colleagues provided comments on the early drafts of the manuscript, especially Igor GONTCHAROV and Ron IPHOFEN.

1) I was member of the Panel for several years, starting in 2001. Under my tenure, I chaired the Social Sciences and Humanities Ethics Special Working Committee that authored the Qualitative Research Chapter in the Tri-Council Policy Statement on Research Involving Human (TCPS2).The TCPS2 became the lead document for all Canadian universities and researchers. <back>

2) These figures are my estimates, but I used the budget set aside in Canada for research ethics review and multiplied that amount by the number of countries also engaged in research ethics review. The costs cover the bureaucracy and its conferences, and the cost of publications. They also cover the activities of local research ethics boards. They exclude costs related to scholarly conferences on the subject. The costs seem higher for individual United States ethics committees. In any case, the overall figures are an overwhelming indication of the total, global costs. <back>

3) Beneficence" is not the same as "benefits." Following SCHROEDER and GEFENAS' work (2012), Ron IPHOFEN informed me that beneficence "is well-meaning though it appears the former is patronizing the latter entails ensuring those ‘being studied' establish what ‘benefits' are appropriate" (personal e-mail communication, November 2, 2017). Because it is the highly privileged group of medical researcher who defined what constitutes "beneficence" (and not the research subjects themselves), we can speak of a patronizing attitude. <back>

4) Kenneth John RYAN, M.D., Chairman, Chief of Staff, Boston Hospital for Women; Joseph V. BRADY, Ph.D., Professor of Behavioral Biology, Johns Hopkins University; Robert E. COOKE, M.D., President, Medical College of Pennsylvania; Dorothy I. HEIGHT, President, National Council of Negro Women, Inc.; Albert R. JONSEN, Ph.D., Associate Professor of Bioethics, University of California at San Francisco; Patricia KING, J.D., Associate Professor of Law, Georgetown University Law Center; Karen LEBACQZ, Ph.D., Associate Professor of Christian Ethics, Pacific School of Religion; David W. LOUISELL, J.D., Professor of Law, University of California at Berkeley; Donald W. SELDIN, M.D., Professor and Chairman, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Texas at Dallas; Eliot STELLAR, Ph.D., Provost of the University and Professor of Physiological Psychology, University of Pennsylvania; and Robert H. TURTLE, LL.B., Attorney, VomBaur, Coburn, Simmons & Turtle, Washington, D.C. <back>

5) The ten M.Ds are: Robert J. LEVINE, H.Tristram ENGELHARDT, Jr., Alvan R. FEINSTEIN, Donald GALLANT, Gerald KLERMAN, David SABISTON, Lawrence C. RAISZ, Alasdair MACINTYRE, Jeffrey L. LICHTENSTEIN, Robert VEATCH; two legal experts: John ROBERTSON and Joe Shelby CECIL; four philosophers:Kurt BAIER, Tom BEAUCHAMP, James CHILDRESS (also theologian), Maurice NATANSON; six psychologists: Donald T. CAMPBELL, Israel GOLDIAMOND, Perry LONDON, Gregory KIMBLE, Diana BAUMRIND, and Leonard BERKOWITZ; two sociologists: Bernard BARBER and Albert REISS, Jr.; one policy analyst: Richard A. TROPP; and one of unknown professional identity: LeRoy WALTERS (Source: https://videocast.nih.gov/pdf/ohrp_appendix_belmont_report_vol_2.pdf [Accessed: April 10, 2018]). <back>

6) Google provided the image of this particular armadillo. There are nearly 16 million references to this animal in Google, along with countless photos and other images. Because URLs are constantly drifting away and shifting, I was unable to find this exact image. I would be much obliged if a reader can identify the exact source of this image. <back>

7) Laurel RICHARDSON (1990) speaks about how researchers write in an author-evacuated manner to have their work accepted in mainstream publications rather than in a way that is more natural to qualitative researchers. The ubiquitous detached of writing, with its objective tone, is something that she warns writers in the social sciences about. <back>

8) Article 10.4 in TCPS 2 states that, "in some research contexts, the researcher may plan to disclose the identity of participants. In such projects, researchers shall discuss with prospective participants or participants whether they wish to have their identity disclosed in publications or other means of dissemination. Where participants consent to have their identity disclosed, researchers shall record each participant's consent" (http://www.pre.ethics.gc.ca/pdf/eng/tcps2-2014/TCPS_2_FINAL_Web.pdf [Accessed: April 10, 2018]). My assurance to the research participants that I would anonymize them and the village, was undone by the publication of this novel. <back>

9) These semi-elliptical arrows indicate the resistance of the "armadillo" (i.e., the medical research ethics paradigm) to some research ethics ideas emanating from the social sciences. <back>

10) The reason why the terms "protocol" and "subjects" do not appear in any of the images is because these terms are not associated with ethical principles, but with methodology. <back>

11) Sule TOMKINSON (2015) has reflected on the challenges of doing research on state organizations, including democratic ones which would lead to critical accounts. <back>

12) Wolff-Michael ROTH (2004, §1) has shown what characterizes the actions of REBs is "restriction and control, and therefore the exercise of power over research," rather than the ethical conduct of qualitative research involving human beings. <back>

Abbott, Lura & Grady, Christine (2011). A systematic review of the empirical literature evaluating IRBs: What we know and what we still need to learn. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics, 6(1), 3-19.

Allemann, Lucas & Dudeck, Stephan (2017). Sharing oral history with Arctic indigenous communities: Ethical implications of bringing back research results. Qualitative Inquiry, Online First.

Allen, Gary (2008). Getting beyond form filling: The role of institutional governance in human research ethics. Journal of Academic Ethics, 6(2), 105-116.

Anonymous (2013). uOttawa criminologists go to court to protect research confidentiality. CAUT Bulletin, 60(1), 1 and 7.

Bell, Kirsten (2014). Resisting commensurability: Against informed consent as an anthropological virtue. American Anthropologist, 116(3), 511-522.

Bell, Kirsten (2015). Abandoning informed consent?. American Anthropological Association Ethics Blog, February 28, http://ethics.aaanet.org/abandoning-informed-consent/ [Accessed: April 10, 2018].

Bosk, Charles L. (2001). Irony, ethnography, and informed consent. In C. Barry Hoffmaster (Ed.), Bioethics in social context (pp.199-220). Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

Broverman, Aaron (2016). Woman with spina bifida filing human rights complaint against Danforth Bar. 21 August. Now Newsletter, https://nowtoronto.com/news/woman-with-spina-bifida-filing-human-rights-complaint-against-danforth-bar/ [Accessed: April 8, 2018].

Burris, Scott (2008). Regulatory innovation in the governance of human-subjects research: A cautionary tale and some modest proposals. Regulation and Governance, 2(1), 65-84.

Campbell, Nancy & Stark, Laura (2015). Making up "vulnerable" people: Human subjects and the subjective experience of medical experiment. Social History of Medicine, 28(4), 825-848.

Carpenter, Dale (2006). Institutional Review Boards, regulatory incentives, and some modest proposals for reform. Northwest University Law Review, 101(2), 687-706, http://scholarship.law.umn.edu/faculty_articles/352 [Accessed: April 8, 2018].

Castrodale, Mark Anthony (2017). Mobilizing dis/ability research: A critical discussion of qualitative go-along interviews in practice. Qualitative Inquiry, 24(1), 45-55.

Daníelsson, Guδmundur (1972). Járnblómiδ [Weather vane]. Reykjavik: Isafoldar Prentsmiδja.

Garrard, Eve & Dawson, Angus (2005). What is the role of the research ethics committee? Paternalism, inducement, and harm in research ethics. Journal of Medical Ethics, 31, 419-423.

Hochschild, Arlie Russell (1983). The managed heart: Commercialization of human feeling. Oakland, CA: University of California Press.

Lowman, John & Palys, Ted (2014). The betrayal of research confidentiality in British sociology. Research Ethics, 10(2), 97-118.

Marlowe, Jay & Tolich, Martin (2015). Shifting from research governance to research ethics: A novel paradigm for ethical review in community-based research. Research Ethics, 11(4), 178-191.

McGinn, Michelle K. & Bosacki, Sandra L. (2004). Research ethics and practitioners: Concerns and strategies for novice researchers engaged in graduate education. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 5(2), Art. 6, http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-5.2.615 [Accessed: April 8, 2018].

National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research (1978). The Belmont Report Ethical Principles and Guidelines for the Protection of Human Subjects of Research: Appendix Volume II. DHEW Publication No. (OS) 78-0014, https://videocast.nih.gov/pdf/ohrp_belmont_report.pdf [Accessed: April 4, 2018].

Ogden, Russell (2004). When research ethics and the law conflict. Presentation at the Annual Meeting of National Committee on Ethical Human Research, Aylmer, QC, March 6, 2004.

Olivier, Steve & Fishwick, Lesley (2003). Qualitative research in sport sciences: Is the biomedical ethics model applicable? Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 4(1), Art. 12, http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-4.1.754 [Accessed: April 8, 2018].

Restivo, Sal & Dowty, Rachel (2008). Obituary: Bernard Barber and Mary Douglas. Social Studies of Science, 38(4), 635-640.

Richardson, Laurel (1990). Writing strategies: Reaching diverse audiences. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Roth, Wolff-Michael (2004). (Un-) political ethics, (un-) ethical politics. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 5(3), Art. 35, http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-5.3.573 [Accessed: April 8, 2018].

Santin, Marlene, & Kelly, Benjamin (2017). The managed heart revisited: Exploring the effect of institutional norms on the emotional labor of flight attendants post 9/11. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 46(5), 519-543.

Schroeder, Doris & Gefenas, Eugenijus (2012). Realising benefit sharing: The case of post-study obligations. Bioethics, 26(6), 305-314.

Smith, Wesley J. (2001). Revisiting the Belmont Report. Hastings Center Report, 31(2), 5.

Speckman, Jeanne L.; Byrne, Margaret M.; Gerson, Jason; Getz, Kenneth; Wangmo, Gary; Muse, Carianne T. & Sugarman, Jeremy (2007). Determining the costs of institutional review boards. IRB: Ethics and Behavior, 29(2), 7-13.

Tomkinson, Sule (2015). Doing fieldwork on state organizations in democratic settings: Ethical issues of research in refugee decision making. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 16(1), Art 6, http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-16.1.2201 [Accessed: April 8, 2018].

van den Hoonaard, Deborah K. (2001). The widowed self: The older woman's journey through widowhood. Waterloo: Wilfrid Laurier University Press.

van den Hoonaard, Will C. (1972). Local-level autonomy: A case study of an Icelandic fishing community. M.A. Thesis, Department of Sociology, Memorial University of Newfoundland, St. John's, Newfoundland.

van den Hoonaard, Will C. (1987). Book review of "Guy D. Wright, Sons and seals". Anthropologica, 29(2), 214-216.

van den Hoonaard, Will C. (1992). Reluctant pioneers: Constraints and opportunities in an Icelandic fishing community. New York, NY: Peter Lang.

van den Hoonaard, Will C. (2003). Is anonymity an artifact in ethnographic research?. Journal of Academic Ethics, 1(2), 141-151.

van den Hoonaard, Will C. (2011). The seduction of ethics: Transforming the social sciences. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

van den Hoonaard, Will C. (2017a). About "othering" ourselves in a system with discrepant values: The research ethics review process today. In Ron Iphofen (Ed.), Finding common ground: Consensus in research ethics across the social sciences (pp.61-75). London: Emerald.

van den Hoonaard, Will C. (2017b). Critical enquiry in the context of research ethics review guidelines: Some unique and subtle challenges. In Catriona Macleod, Jacqueline Marx, Phindezwa Mnyaka & Gareth Treharne (Eds), Handbook of ethics in critical research: Stories from the field (pp.1117-130). Milton Park: Palgrave/Macmillan.

van den Hoonaard, Will C. & Connolly, Anita (2006). Anthropological research in light of research-ethics review: Canadian masters theses, 1995-2004. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics, 1(2), 59-70.

van den Hoonaard, Will C. & Hamilton, Ann (12016). The ethics rupture: Exploring alternatives to formal research-ethics review. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

von Unger, Hella; Dilger, Hansjörg & Schönhuth, Michael (2016). Ethics reviews in the social and cultural sciences? A sociological and anthropological contribution to the debate. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 17(3), Art. 20, http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-17.3.2719 [Accessed: April 8, 2018].

Whitney, Simon N. & Schneider, Chris E. (2011). Viewpoint: A method to estimate the cost in lives of ethics board review of biomedical research. Journal of Internal Medicine, 269(4), 396-402.

Williams, Terry (2017). Teenage suicide notes: An ethnography of self-harm. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

Wolf, Daniel R. (1991). The rebels: A brotherhood of outlaw bikers. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Wright, Guy D. (1986). Sons and seals: A voyage to the ice. Halifax: Formac.

Yanow, Dvora & Schwartz-Shea, Peregrine (2008). Reforming Institutional Review Board policy: Issues in implementation and field research. Political Science and Politics, 41, 483-494.

Dr. Will C. van den HOONAARD, Professor Emeritus at the University of New Brunswick in Fredericton, has conducted field research on a variety of topics, including Icelandic marine resource management, the Baha'i Community of Canada, the Dutch of New Brunswick, gender issues, inductive research, and a 700-year history of women mapmakers. Research ethics are the focus of six of his books. He is Founding Member of the Canadian Interagency Panel on Research Ethics. He was raised in the Netherlands, France, and Canada. A Woodrow Wilson Fellow, he obtained a PhD in sociology from the University of Manchester.

Contact:

Will C. van den Hoonaard

Department of Sociology

University of New Brunswick

PO Box 4400, Fredericton NB, E3B 5A3

Canada

Tel.: 1-506-472-9465

E-mail: will@unb.ca

van den Hoonaard, Will C. (2018). Autobiographical Notes from Inside the Ethics Regime: Some Thoughts on How Researchers in the Social Sciences Can Own Ethics [45 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 19(3), Art. 3, http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-19.3.3024.