Volume 19, No. 3, Art. 1 – September 2018

A Transactional Approach to Research Ethics

Wolff-Michael Roth

Abstract: Constructivist (constructionist) epistemologies focus on ethics as a system of values in the mind—even when previously co-constructed in a social context—against which social agents compare the actions that they mentally plan before performing them. This approach is problematic, as it forces a wedge between thought and action, body and mind, universal and practical ethics, and thought and affect. In this contribution, I develop a transactional approach to ethics that cannot be developed within constructionism. In a once-occurrent world, every act is ethical because it has consequences for the agent (who affects and is also affected), and the world as a whole. However, whereas many in the social sciences continue to articulate a theory of action and thus the practical nature of ethics in terms of the individual's act, in this contribution I show that the act always already is spread across people and things and, thus, is an integral and constitutive part of a transaction. This utterly relational take on human behavior thus undermines approaches to ethics that are based on the individual as unit of analysis. Most controversially perhaps, I exhibit how those who may feel hurt by the actions (talk) of others are themselves agents affecting those others and, thus, answerable. This approach is illustrated in the context of power-knowledge, which is the result of an always ongoing, only once-occurrent situated and situational struggle rather than something a priori distributed between people.

Key words: transaction; translocution; joint action; reflexivity; postcolonialism; responsibility; answerability

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

1.1 Problem and purpose

1.2 Self-action and interaction

1.3 Transaction

2. Toward Translocution as Model of Social Action

2.1 Self-action, interaction, and ethics

2.2 Translocution and associated ethics

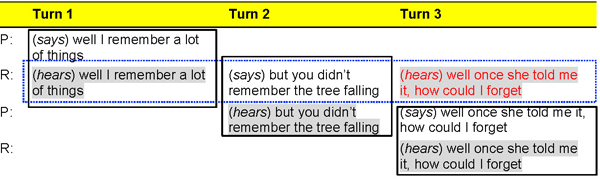

3. The Transactional Approach and the Question of Power

4. Transactional Ethics: From Analysis to Praxis

5. Coda

"The summons is understood only through the response and in it" (CHRÉTIEN, 2007, p.39).

"One cannot separate response from responsibility" (p.3).

"The one has no sense other than the-one-for-the-other: the diachrony of responsibility constitutes the subjectivity of the subject" (LEVINAS, 1971, p.45).1)

These three introductory quotations constitute the sketch of a program. The first quotation states that some phrase is not understood on its own—i.e., does not "have" one "meaning" or several "meanings"—but only through the response it calls forth. Every action is a response to the summons of another person on situation. The second quotation adds that the response, and therefore every action, comes with responsibility. Finally, the third quotation elaborates the issue of responsibility, always for the other, and thus constitutes the very sense and essence of subjectivity. In this approach, ethics is not something added from the outside onto a previously conceived (planned) act but a quality inherent in person-acting-in-the-world-and-toward-others (i.e., in transacting). This quality cannot be legislated and enforced however much a research plan is vetted and shaped by passing the judgments of human research ethics committees. It forces us to move beyond ethics commonly conceived and move toward an approach grounded in collective responsibility and solidarity of researchers and participants (e.g., ROTH, 2006). After introducing and critiquing individualist and weakly social approaches to theory of actions, I present translocution as a model for acting in the social world. Translocution not only takes us to directly the inseparability of responsibility from the response that follows and affirms a summons but also to the diachrony of responsibility, that is, responsibility that is spread across speaker and recipient, agent and patient, humans and their world. The central point to be worked out in this contribution is this: research ethics works two ways rather than in the one way presupposed in current institutional processes of research ethics review. [1]

In qualitative research, ethics generally is considered through the lens of the researcher-agent. In countries where they exist, institutional ethics procedures are designed to protect the participant-patient. The position is apparent when—e.g., in formal, institutional ethics review processes—the responsibility for the well-being of research participants is the responsibility of the researcher. This standard position of institutionalized ethics follows a Kantian logic that considers judgments and actions theoretically and detached from their immediate contexts and the actors' motives (e.g., ROTH, 2008). As a result, "the actual deed is cast out into the theoretical world with an empty demand for legality" (BAKHTIN, 1993, p.26). Ethics committees consider the (research) act theoretically and thus fail to comprehend "the actually performed act, which is once-occurrent, integral, and unitary in its answerability" (p.28). The approach of thinking ethics through the agency of the researcher may be the case even for those who articulate a much more differentiated (e.g., feminist) view that use relational concepts, such as when women are said to "define themselves in terms of caring and work their way through moral problems from the position of one-caring" (NODDINGS, 2003 [1984], p.8). The problem with the individualist and formal take on research ethics is that it first becomes an issue of the mind, which makes up plans of actions consistent with or against ethical standards that are subsequently implemented. The introductory quotations direct us toward and guide us along the way toward an ethics that does not first exist in the mind to be subsequently grounded in and made relevant to practical action. In the same way as the concordance of actions with the plans that initiated them can be assessed only after the fact (e.g., SCHÜTZ, 1932; SUCHMAN, 2007), so the concordance of the practical ethics with any formal ethics can be determined only after the fact. In the relational (transactional) approach, we are summoned by the words and deeds of others. This already places us in an obligation to answer and answer for (something and ourselves); and it does so in a way so that there exists a diachrony of responsibility. The purpose of this article is to show how a different form of (practical) ethics emerges when we consider the world from a transactional perspective with irreversible consequences for all involved (persons and things). In a transactional world, actions cannot be assigned to individuals (e.g., DEWEY & BENTLEY, 1999 [1949]) so that the responsibility for an act (blaming) cannot be attributed to them (ROTH, 2013, 2018). As the presentation and discussion below shows, the transactional approach implies ethics to be a quality of the situation as a whole. Thus, while not relieving qualitative researchers from responsibility, the approach makes it a quality of the historical situation as a whole. Before turning to exemplify and elaborate the transactional approach by means of a concrete situation, I distinguish it from the vastly more common self-actional and interactional approaches. [2]

1.2 Self-action and interaction

In this study, the adjective constructivist refers to the use of the term in the educational literature, where it denotes epistemologies according to which individuals are the authors of (their own) knowledge (VON GLASERSFELD, 1989); it is a core presupposition of the self-actional approach. This knowledge, some of which exists in the form of sensorimotor schemas (VON GLASERSFELD, 2001), is the origin and cause of the action that the individual displays. The view therefore constitutes a self-actional theory of behavior—similar to what a cognitivist perspective yields. The individual act, arising from thought, is evaluated theoretically in terms of accepted rules and laws external to it. Social constructivists and others using the adjective social as a defining characteristic, while accepting the individual construction of conceptual knowledge and sensorimotor schemas, attribute to relations a certain force that regulates the nature of knowledge in the social arena before individuals internalize this knowledge for themselves. Although self-action is integral to such theories, the social is recognized in the role researchers attribute to the interactions between members of a group. Interaction means that one action follows another reacting to the one(s) preceding it; and the members of the group orient toward the possible reactions of others. Interaction thus means that individual (self-) actions come to be juxtaposed and chained, such as when replies are said to follow questions, each taken as existing in their own right. In so doing, constructivist theories take the social to be a contingent factor in the construction of knowledge and action. Approaching the social as a contingent factor, constructivism (constructionism) constitutes the social in a weak sense (LIVINGSTON, 2008). What comes to be an accepted and dominant form of knowledge, theory, or discourse is the result of the interplay (e.g., in negotiation) of different positions that individuals take in the public arena. The outcomes of the social processes, interactions, are the results of social constructions. The social (constructivist) constructionist positions give primacy to these interactions—but do not (tend to) abandon the individual as the origin of actions. A lot of qualitative research takes precisely this epistemology as foundational. [3]

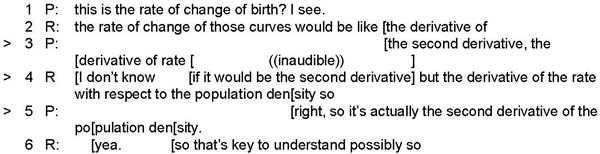

Philosophers and social scientists from very different traditions have critiqued this take on actions in the social world. From a Spinozist-Marxian position, for example, there is no sense to ground actions in the thoughts of individuals, for "all talk of thought first arising and then 'being embodied in words,' in 'terms' and 'statements,' and later in actions, in deeds and their results ... is simply senseless" (IL'ENKOV, 1977, p.44). Similarly, there is very little sense to reducing social action to the sequencing of individual actions to make them interactions: "Collective action, in its modes, possibilities, and laws cannot be reduced to a sum of individual actions" (CHRÉTIEN, 2007, p.194). [4]

In the transactional approach, actions are inherently rather than contingently social (e.g., MEAD, 1938). The adjective transactional is used here to denote a theoretical approach that no longer accepts the primacy of the individual in interaction with others but instead takes a transactional world as its ontological starting point. Every act is recognized to be cooperative, requiring two or more individuals working in concert. Some readers may find this idea difficult to grasp because we are so used to ascribing actions to individuals (e.g., the content of statements individuals make are said to be their beliefs, opinions, or knowledge). But the consideration of a simple situation shows that more needs to be done theoretically than adopting the common sense position. Consider the case where an intended act (e.g., to make a joke) differs from its effect (e.g., a person is hurt or insulted). The effect will be that the pair (group) now is confronted with the reality and problem to be addressed. This shows that the act cannot be conflated with the intention of the agent, as self-actional and interactional approaches do, for what actually happened also is a function of the recipient (patient). But in other situations, the same phrase (action) may indeed be heard as intended (i.e., as a joke). In the transcription of the event from the actual world to the narrative, something that depends on all participants comes to be ascribed to one of the individuals. [5]

The recognition that something important happens in the "transcription" of actions is not new. The predicative nature of (Western) language separates the agent from the action according to the principle that there is a cause to every change. "But this conclusion already is mythology: it separates that which effects from the effecting. When I say 'the lightening flashes,' I have posited the flash once as an activity and a second time as a subject" (NIETZSCHE, 1922 [1885/1886], p.43). In the processes, a new and different form of Being has been attributed to the event. The subject is and remains but no longer becomes. In attributing actions to agents, we are misrepresenting the transactional nature of the world: "To set the event as cause: and the cause as Being: this is the double error, or interpretation, of which we are guilty" (ibid.). In other words, the event is decomposed into an effect and a cause, and the effect is attributed to the cause as a property. The alternative position is to take properties of persons and things as effects upon other persons and things, the result of which would be that if the other persons and things do not exist or are imaginatively eliminated, then persons and things no longer have the property. That is, "there is no thing without other things" and "there is no 'thing in itself'" (p.61). [6]

An action only becomes a thing that can be ascribed to an individual under the condition that it has been objectified; and this objectification occurs in a process that resembles the transcription of a translocution into a sequence of locutions (RICŒUR, 1986). It is in the process of fixing the (speech) act to the individual that it becomes objectified. Thanks to this objectification, "the action is no longer a transaction" (p.191) but ascribed to an individual agent who is said to be the cause of the action. In the same move, the signification ("meaning") of the act is detached from the action as event. This also is the conclusion within a very different philosophical tradition according to which individual "properties" really are the effects of relationships, which are not internal to or characteristic of individuals. Thus, "it is nonsense to talk about 'dependency' or 'aggressiveness' or 'pride,' and so on. All such words have their roots in what happens between persons, not in some something-or-other inside a person" (BATESON, 1979, p.133). In many aboriginal languages, the relational nature is part of naming—such as when Palauans change denoting snapper by the generic term richoh to hatih, hard to find; when they denote a fish species as Hari merong, always bites, takes any bait; or when they use the term yetam, travels with the father, for a fish that generally accompanies larger fish (JOHANNES, 1981). In this language, therefore, the concept nouns express the relation of the fish to the fisher or the fish to the bait. To work out a number of aspects that arise from a transactional perspective on research ethics, I develop and exemplify translocution as a model of joint, inherently (rather than contingently) social action. [7]

2. Toward Translocution as Model of Social Action

Text has been shown to be a useful model for the social sciences interested in the understanding of action that makes sense [action sensée] (RICŒUR, 1986). In the preceding section, I refer to the position that the world inherently is transactional. Because spoken language occurs in the event of translocution, the latter can be used as a model for relations that make the human social world. Theorizing the act in terms of translocution comes with the affordance of a pairing and co-implication of response (answer) and responsibility (answerability). This pairing and co-implication exists in many other languages as well, including and exemplified in the pairs Antwort-Verantwortung (Ger.), réponse-responsabilité (Fr.), and otvet-otvetstvennost' (Rus.). In the following, I begin by exemplifying the common (self- and interactional) approach to conversation (thus action) and proceed to present a translocutional model of social action. This model serves as the basis for developing a transactional position on ethics. [8]

2.1 Self-action, interaction, and ethics

"Formal ethics provides no approach to a living act performed in the real world." (BAKHTIN, 1993, p.27)

Fragment 1 derives from an interview, where a researcher (R) interviews three individuals who, one year earlier, had been part of a special school science curriculum designed such that young students can contribute to the environmental activism in their community. One of the three interviewees (P) was the chaperon of one group of students in the teaching of the curriculum.

Fragment 1 [9]

The first feature to be noted is the attribution of each turn to an individual: always that individual, from whose mouth the phrase or phrases have come. This attribution of the phrase to the individual allows researcher to speculate what the speaker means to say—often without explicitly saying so—and what the speaker is doing. For example, the participant may be said to "claim" that he remembered a lot of things about the science lessons that had taken place one year earlier. Then, the researcher, who is assumed to have interpreted what the preceding speaker has stated, might be said to be "critiquing" or "questioning" the preceding claim by noting that the participant had not (previously) recalled an incident involving a falling tree. Finally, the participant might be described as "admitting" that he had forgotten, which also means admitting that the case was overstated, and then phrasing his position that also "saves face." The individualistic approach is apparent in this quite standard reading of the fragment. Qualitative researchers are in the business of making statements about the "meanings" that the individuals "make," and about the differences between that might be the cause for misunderstandings. Other qualitative researchers, interested in the concept of identity, may even write about positioning, and how the participant attempts to construct an aspect of his identity, as an individual who remembers past events very well. But there are also interactional elements to the story in the sense that the participant partially retracts and modifies his position in reply to the critique (Turn 2). This may lead researchers to conclude that the identity of an individual is not merely the result of a personal construction but indeed is the result of a negotiation in a third, public space different from the original and elementary spaces that are but mobilized in the production of meaning (BHABA, 1994). In this view, the participant tries to position himself in a particular way but is forced to reposition when the researcher, by means of her critical comment, undermines the specific positioning move. [10]

Some readers may be familiar with speech act theory (AUSTIN, 1962) and conversation analysis (SACKS, 1992); others may have had opportunities to observe an interactional approach to dialogical theory (BAKHTIN, 1981). All these theoretical takes emphasize the need to consider pairs of turns as a unit. Thus, for example, a question is a question because there is a reply; and a reply is a reply because there is a question. In the fragment, the pairing {Turn 1 | Turn 2} may be described as a {claim | rejection} or {claim | critique} pair. Drawing on these theories, qualitative researchers attempt to put together what previously was taken apart. But these attempts generally fail because, for example, the illocutionary act—what the speaker tries to do—still belongs to the individual speaker. The turn pairs become social because there are two individuals participating in the exchange. Claim and critique still are attributed to the individuals. The ethical dimension of the critique (Turn 2) may still be attributed to the researcher. And it is not far-fetched at all but rather common to read research reports where such a turn at talk then is interpreted in the context of the idea of power-over: here, the researcher in a power-over the researched situation. [11]

The theory of (self- and inter) action developed here is associated with a particular approach to ethics. In the metaphysics of morals, a single imperative is sufficient to deduce all imperatives of duty. This imperative therefore is categorical: "only act according to that maxim by which you simultaneously can will that it should become a general law" (KANT, 1956 [1785], p.51) or, in other words, "act such that by your will the maxim of your action could become a general law of nature" (p.51). In this formulation, the categorical imperative embodies an individualist subjectivist approach. A maxim governs what the individual does. It is a subjective rule of action that could become an objective law and, thus, is contrasted with the objectivity of the latter. This subjectivist element makes the Kantian approach suitable as a formulation of ethics within (radical) constructivism, or it constitutes a personal formulation of how to act that does not involve the coercion on the part of others. It is the most foundational rule on the basis of which all "subjective rules of action" may be generated (VON GLASERSFELD, 2009, p.118). This approach may be combined with the subjective construction of the other to whom are attributed rules of action similar to our own. This then leads to a more viable approach to ethics, where the individual also takes into account the rules of actions it attributes to others. Thus, the (radical) constructivist position "suggests that if actions of 'others' that you have constructed—a construction that is not ad lib but is constrained by facts of experience—can be interpreted as similar to your own, they may confirm a second-order viability" (p.119). Formal ethics constructed on the grounds of reason fails the subject of the ethics of the real, once-occurrent act because, as the introductory quotation to this section states, it does not provide us with an avenue to the living act. This is so because developing exclusively within the bounds of Kantianism, formal ethics "conceives of the category of the ought as a category of theoretical consciousness, i.e., it theoretizes the ought, and, as a result, loses the individual act or deed" (BAKHTIN, 1993, p.25). Formal ethics based on a constructivist theory of action therefore does not provide us with the means of grasping the ethical dimensions of the real, living act as it unfolds and plays itself out in the social world. [12]

2.2 Translocution and associated ethics

The common form of transcribing a conversation constitutes an insidious reduction of complex social world into a simple give and take. A different picture about actions and the relation between human beings emerges when we include the recipient (listener), as shown in the revised Fragment 1. It is acknowledged that this does not lead us to a transcription of the event as a whole, which alone could avoid "los[ing] the very sense of its being an event, that is, precisely that which the performed act knows answerably and with reference to which it orients itself" (BAKHTIN, 1993, p.31). But the revised transcription allows us to see enough to institute the move to the transactional perspective advocated here. Thus, if there were no recipient, there would not be a relation at all but two independent producers of sounds that have nothing to do with one another. However, rather than approaching the fragment from the perspective of two individuals, whose actions build on the actions of the other, we may "begin to think of the two parties to the interaction as two eyes, each giving a monocular view of what is going on and, together, giving a binocular view in depth. This double view [then] is the relationship" (BATESON, 1979, p.133). Saying inherently is contact with the other, always associated with a wound or caress (LEVINAS, 1971). The revised transcription represents the sound-words, not individual meanings, intentions, feelings, and so on.

Fragment 1, revised [13]

The revised transcription takes into account that each phrase not only exists in the mouth of the speaker but also rings in the ears of the recipient (words against grey background). These are the same sound-words in the two cases—a fact that is marked here by means of a solid box. This box does stand for a joint, social event: corresponding. There are two ways of hearing the term corresponding, both of which are pertinent here. First, corresponding signifies participating in a communicative exchange—traditionally this has been in the form of sending letters, but today occurs more frequently in the forms of email, text messages, and other electronic forms. There is an exchange, and what is exchanged, the word or phrase, is common to the pair. This leads us directly into the second issue: corresponding as "to be in accord" or "to agree with." Corresponding, because it always involves two or more individuals, inherently is a social event in which two or more people are involved. The concept is consistent with a pragmatic philosophy of ethics and the act according to which there is nothing subjective and psychological about the act considered "from within the act itself, taken in its undivided wholeness" (BAKHTIN, 1993, p.29), where each act is understood to be only a phase in the life process so that its sense in a strong sense depends on the world as a whole (cf. DEWEY, 1938; MEAD, 1932; VYGOTSKIJ, 2002 [1934]). It also allows us to understand that there is an unavoidable asymmetry, which arises not because of the different roles that the participant and the researcher take, but because "appeal and reply do not converge onto a common" (WALDENFELS, 2006, p.66). [14]

We may indeed deepen our analysis by taking a closer look at the phenomenon of corresponding. It consists, on the one hand, of speaking and, on the other hand, of the simultaneous actively attending to and receiving. That is, the constitutive parts of corresponding are several actions, which are spread over the group (here pair). The social act of corresponding, in technical terms, is diastatic and dehiscent, that is, it is one whole spread out over two or more parts that constitute a unity despite a gaping, abyssal separation. There is no corresponding of just one person. It takes the joint action of several persons to realize an event of corresponding. We may also speak of the coming and going that is involved within corresponding. Thus, whereas we may envision a movement from the speaker to the recipient, there would be no effect unless recipients were actively directing their attention toward speakers—there is a movement from recipients (patients) to speakers (agents). In addition, on the part of the recipient, the orientation (movement) toward the speaker is paired with an (active) opening up and willingness to receive (i.e., a movement from speaker to the listener). [15]

In many and perhaps most social situations, the standard maximum silence between two speakers is of the order of one second (JEFFERSON, 1989), but often times, as in schools, it is even shorter. This leaves far too little time between the end of the saying—at which instant the said is constituted—and any possible interpretation that the listener could have produced, made up a reply in the mind, and prior to the resulting speaking. We know this to be the case because research in the cognitive sciences shows that even the mental rotation of a very simple object composed of between one and five squares followed by an action on this object takes more than one and one half seconds (KIRSH & MAGLIO, 1994). This has two important implications. First, recipients are affected prior to knowing by what they are affected (WALDENFELS, 2006), that is, before knowing the content of the act as the result of interpretation. Second, the reply is beginning to form before the Saying has ended (e.g., VOLOŠINOV, 1930); that is, it is forming before the recipient is able to know the (content of the) Said with any precision. [16]

In Turn 2, for example, the recipient (male) does not know what is coming at him. When the "but" sounds, he does not know the said of the phrase that is in the course of unfolding; and he cannot know it right up until the instant when saying has ended, which is the earliest point at which such knowledge could exist. In fact, numerous scholars have pointed out that the speaker is in the same position, knowing the result of her thinking only when speaking has ended, for thought becomes itself in speaking (e.g., MERLEAU-PONTY, 1945; VYGOTSKIJ, 2002 [1934]). This has a radical consequence: if the content of the act cannot be known by agent and patient alike, its ethical dimension (e.g., conformity with rules and laws) unfolds in practice but cannot be known and evaluated with any certainty until after the social act has been completed. Any ethical consideration from outside the act will have to assume it as already completed, on a theoretical plane and in contemplated form (typical for some discussions in institutional ethics committees). Such considerations cannot account for the actual, concrete historicity of the act, characterized by a specific emotional-volitional tone (BAKHTIN, 1993). The example also shows that the recipient, far from merely being affected, contributes to being affected by opening up. He opens up, and in so doing, makes himself vulnerable. That is, the researcher (female) does not just act upon him; she does not just doing something to him (e.g., enact a critique or accuse him of lying) with her words. He opens up and thus exposes himself. But more so, whatever the interviewer's intentions (if she had formulated them for herself prior to opening the mouth to sound the phrase), the hearing contributes to the nature of the social act. But this means that the speaker has exposed herself: Saying constitutes exposition and exposure of one to another. This is so because "being-for-the-other, in the manner of the Saying, is therefore exposing to the other that signification itself" (LEVINAS, 1971, p.42). What is being done is the outcome of their joint doing rather than the doing of one (who critiques, accuses) or the other (who interprets). Turn 2 also allows us to see the evaluative accent that comes with each actualized word. On the one hand, the content of the phrase simply is a factual statement about what has or has not occurred in the preceding part of the conversation: the participant did not remember the event with the falling tree. The phrase begins with the connective "but," which, as the unfolding event shows, is employed and taken in its contrastive function: the "I remember a lot" comes to be contrasted by "but you didn't remember." That evaluation is taken up and directly addressed in the reply (Turn 3). [17]

There is a second, horizontal dimension in the revised fragment that has not yet been considered. The blue, dotted box pulls together into one: 1. the origin of the spoken phrase (Turn 2) in the word of the other, 2. the phrase (locution), and 3. its affect on the other. It is apparent that important aspects of both the origin and the effect of the locutionary act lie outside of the speaker. The blue box (Fragment 1, revised) marks another social act: responding. This act is spread over an extended period of time and over the (social) situation: from its beginning (active attention to the other, reception) to its execution and to its effect. Technically, therefore, responding is diachronic (WALDENFELS, 2006), consisting of the couplet {actively attending & receiving | replying | affecting}. Responding therefore does not belong to the researcher, and, as a Marxian-Spinozist analysis reveals (IL'ENKOV, 1977), the thinking associated with the speech act reaches from its initiation from outside the person to the realization of its effect in the world. There cannot be a cause and effect relation between thought (or thinking) and the act. The speaker, as all "thinking things in the world of all other things" (p.52), is part of a whole situation. To understand "her" thinking, one has to go beyond inside her body (brain) "and examine the real system within which [speaking] is performed" (p.52). Responding thus is dehiscent and diachronic in nature. The diachrony, which is coincidence of the non-coinciding, makes visible an incessant dispossession of individual intention in the face of the collective act. With this dispossession, "nothing remains: neither clothing, nor peel, nor shell, nor even the cover conferring identity. Dispossession right to the core, ab-solution—this diachrony signifies the absolutely one" (LEVINAS, 1971, p.43). This one does not have to be reconstructed but, in the transactional approach, is the original point of departure. The latter two parts—i.e., replying and affecting—also are part of the next irreducible triplet of actions that constitute another act of responding. Responding not only implies taking up the appeal on the part of the preceding speaker, responding to the other [répondre à], but also a form of vouching for [répondre de] the other: from whom the word has come, for whom the word is designed, and to whom the word returns (see blue box). [18]

3. The Transactional Approach and the Question of Power

Institutional ethics procedures often simplistically assume researchers to have power or to have one up in a power-relation with participants. There are suggestions that the notion of power should be distrusted, as it is the most dangerous of all quasi-physical metaphors used in the social sciences (BATESON, 1979). The view of the researcher as in power over the research participant is simplistic because, in protocols and agreements that retain the participants' rights to withdraw at any time, the researcher no longer is in unilateral control over the data. If a participant withdraws after the data collection has been completed, all the effort expended in creating the data has been in vain. The effect is particularly dramatic if the participant is an institution leading to the deletion of the data from all participants that are also members of the institution. We thus need to move beyond simplistic notions of power—which, in this section, is treated in an exemplifying manner for showing how the transactional approach changes the way in which research ethics might be approached. [19]

The framework worked out in the preceding section has considerable consequences for how we think about research ethics. The problem with a Kantian approach to ethics lies in the way that the norm (rule) applying to the act has to be justified as capable to serve as universal law. This justification is accomplished "by way of purely theoretical determinations: sociological, economic, aesthetic, scientific" (BAKHTIN, 1993, p.26). The purely theoretical ground of the justification fails to live up to the real act, which, as shown above, always and irreducibly has consequences for all parties involved. It is precisely here that the gap between the formal ethics of institutional ethics review regimes and practical ethics comes to the fore. Paraphrasing RICŒUR (1990), we might say that the practical wisdom in research collaborations (researchers and participants) exists in inventing conduct that will best satisfy any exception that caring and affective attention (i.e., solicitude) requires while betraying any stated formal rule to the smallest possible extent. Turn 2 in the fragment constitutes a more benign case of considering practical ethics in actual conduct, for the possibility is given for participants to get hurt if they are "accused" of "overstating," "being inconsistent," or indeed of "lying" when a contradiction in their narration becomes apparent. But we do have to go further than RICŒUR in our considerations, because the preceding position still allows us to lapse into an individualist position. Whereas the researcher in the preceding fragment did formulate the phrase, which indeed constitutes a true statement of facts, it contains an evaluation that is not just hers (whatever she might have intended) but also receives part of its content from the response. A first step in our analysis is to acknowledge that "a performed act is active in the actual unique product it has produced" (BAKHTIN, 1993, pp.26-27). [20]

As soon as we think about actions that make sense from a transactional perspective, all those taking part in an event are and become responsible prior to and transcending any intention. In Turn 2, the speaking researcher is responsible for what she says even though the recipient cooperates in the constitution of (the content of) the said. She is responsible even though she is not in control and even though the completion of (the content of) the act lies in the future direction from the point of her speaking. The participant, too, partially is responsible for the content of the saying, that is, the said. From this exemplary analysis, we therefore come to the same conclusion that has resulted from a philosophical analysis: "Responsibility ... always simultaneously is co-responsibility, a practical and collective responsibility. For responsibility always remains a response to that what precedes us and to what surrounds us" (CHRÉTIEN, 2007, p.195). That is, in the take on research ethics developed here, the "victim" of the critique (of overstating a case) or accusation (of lying) is an integral part in the constitution of the event and, therefore, in the very nature of his being a victim. Such a perspective, therefore, radically changes ethics generally and the issue of power-over specifically. As apparent and exemplified in a quotation above, in some theoretical frameworks it makes no sense to take about something such as aggressiveness as a characteristic (property) of an individual. In the same way, power is not a property or characteristic of an individual, who somehow appropriates it, but is instead the result of a microphysics that has effects on the human body (FOUCAULT, 1975). This microphysics is to be studied in terms of an inherent "network of relations, constantly in tension, in activity, rather than a privilege that one might possess" (p.35). Power, or rather, the distribution of power-knowledge, is the result of relations, is exercised collectively rather than possessed as a privilege (e.g., by some "dominant" class or its members). The victims of power are integral and thus irreducible part of the phenomenon of power:

"this power is not solely and simply applied, as an obligation or interdiction on those who 'do not have it'; it invests them, is transmitted by and through them; it rests upon them just as they, in their struggle against it, in turn rest upon the grip that it has on them" (ibid.). [21]

Once we begin thinking power or rather power-knowledge in terms of relations, where those subject to power are as integral to and active in the phenomenon as those who are seen to have a hold on it, then we have to reconsider how we think about ethics and responsibility. Responsibility in the transactional take presented here is radical in the sense that instead of allowing us to discover in it the essence of subjectivity and identity, we take it as not stopping to dispossess the individual. It dispossesses the individual to the point of a unity that cannot be constituted on the basis of individual persons. Individuals cannot be said to have or have not responsibility. Ethics and responsibility are to be investigated in the same way as power-knowledge relations the (qualitative) researcher; they are aspects of the power-knowledge relations. These relations have to be studied as a phenomenon sui generis, for "only if you hold on tight to the primacy and priority of relationship can you avoid dormitive explanations" (BATESON, 1979, p.133). [22]

The need to reconsider power in research arose for me in a project where my research team conducted think-aloud protocols with experts (scientists) talking about graphs. In one part of the project involved physicists. An undergraduate student majoring in physics and anthropology collected the data. This configuration created an interesting complication to the question of power that may not be solvable from the classical perspective. Thus, as a member of the research team, the undergraduate student may be said to be in a power-over situation with respect to the physics professors—indeed, by asking the undergraduate student whether they were right, they treated him as if he knew and was in control over the correct answer (cf. ROTH & MIDDLETON, 2006). But simultaneously, these professors are in a power-over situation with respect to the undergraduate student in their department. To complicate the matters a little further, the data was collected in the offices of the department rather than on some neutral ground that some researchers might chose in the attempt to disrupt the power relations that they presuppose. In the concrete case to be considered here, the question is related to the one about knowledge. Who is an expert in relation to the graphs that the research team presented to the participants? Is there a difference for those graphs that come from the discipline of physics and those that come from the discipline of biology? It turns out that this question cannot be answered based on an abstract analysis; or, if such an analysis were conducted, it likely would not describe the situation that was actually observed. For example, in one situation a professor, apparently having some trouble to make sense, begins asking the researcher to provide him with a clue. What then happens in the videotape best is described as a form of struggle: the videotape makes apparent the effort of the assistant to avoid providing assistance or answers—as per the research protocol—while simultaneously making apparent the physicist's attempt to get some help. In the end, the undergraduate student-researcher tutors the physicist in reading the graph. However, on the way, one can observe continued struggles over who knows and what the relevant knowledge is, such as in the description of a graph as a simple mathematical derivative or a second derivative of some population function (see Fragment 2). That is, even though the professor repeatedly has asked for help (e.g., "give me a hint," "give me a clue," "is that correct?" and "where is your hints?"), thus indicating a lack of knowing-how to read the graph, in the actual working through there are continued struggles over the correct way of describing the graphs and determining the pertinent signifieds.

Fragment 22) [23]

From a practical perspective on ethics, the ethical question may be rested on the researcher's behavior (RICŒUR, 1990). He would be put in the position to develop behavior that corresponds to the solicitude of the situation while minimally breaking the rules of research method and ethics. On the one hand, there is an apparent request for help; on the other hand, the research protocol states that the only researcher actions to take place while participants are solving the task should be those encouraging the latter to think aloud (when they have fallen silent). In the present study, a different take is suggested, on in which the questions of ethics and their solutions are the result of the joint transactional work of the pair. There are suggestions that social science methods need to account for these (researcher-participant, observer-observed) transactions or they miss the very nature (essence) of the phenomenon of interest (BATESON, 1979; DEVEREUX, 1968; DEWEY & BENTLEY, 1999 [1949]). [24]

The discussions of power-over often concern the questions about the ownership of knowledge, beneficiaries of the research project, and the relevant forms of interpretational expertise. The discussions tend to be classical even in cases where authors strive toward developing postcolonial positions where knowledge is described as something (indigenous) peoples have (and own) and power (control) that others have over knowledge in imposing their interpretations. The tensions are apparent in phrases such as this: "despite the fact that all peoples have knowledge, the transformation of knowledge into a political power base has been built on controlling the meanings and diffusion of knowledge" (BATTISTE, 2008, p.500, emphasis added). In the approach proposed here, there is no place for knowledge and power to be had and owned like an object, especially not by individuals and individual institutions. [25]

The question of benefits—e.g., "What knowledge is produced?" and "Where does it become a resource?"—does not have simple and simplistic answers. The same research project then may produce different knowledge resources for different communities benefiting participants and researchers alike. Thus, one of my projects included collaborating with an airline. We agreed beforehand to have two forms of outcome: a report to the company with forms of evidence that it could use in their decision-making processes and the concurrent possibility to contribute to the scientific literature in communities interested in the relation between cognition, technology, and work. As a result of my investigation, the airline decided not to have the same pilots fly two versions of the same aircraft based on an analysis of pilot errors and a generic description of how to locate possible trouble spots in company procedures (MAVIN, ROTH, SOO & MUNRO, 2015). At the same time, I prepared a text to be submitted for publication in a scientific research journal, which took an ecological perspective on the question of how a cockpit (not the pilot!) forgets speeds and speed-related events (ROTH, MAVIN & MUNRO, 2015). [26]

4. Transactional Ethics: From Analysis to Praxis

A transactional approach allows us to grasp the ethical dimension of the irreducible social act. Although not conceived in terms of ethics, methodological reflection on the researcher-participant relation has revealed the dual direction of its effects, as captured in the conceptual couplet of transference (redirection of the participant's feelings to the researcher) and countertransference (DEVEREUX, 1968). Every research project also is an observation performed on the researcher. Accordingly, as noted in the introduction, research ethics works two ways rather than in the one way presupposed in current institutional processes of research ethics review. Research in the social sciences gives rise to anxieties, which remain even when a pseudo-methodology attempts to ward off the effect of countertransference—the redirection of the researchers' feelings toward the participant. A transactional approach is necessary. Thus, "the behavioral scientist cannot ignore the interaction between subject and observer in the hope that, if he but pretends long enough that it does not exist, it will just quietly go away" (p.xviii). [27]

Research is a form of institution. Institutions are just when they work out in concrete practice the ethical intention to work with and for others may arise only when form and content of the ongoing conversation between researcher and participant are dialogic, that is, open to continual development. Some of my work has taken place in schools, which traditional approaches would describe in hierarchical terms with power in the hands of those higher up on a ladder constituting the institution. The idea underlying our work was that institutions are not just in themselves. Instead, just institutions are those that continuously become, oriented toward an ideal that is forever to come (Fr. à venir) because it forever lies in the future (Fr. à-venir). This is but another way of formulating ethics in a transactional, dialogical way such that ethics, as everything else, ends "when dialogue ends," for "dialogue, by its very essence, cannot and must not come to an end" (BAKHTIN, 1984, p.252). Research ethics, therefore, is not a concept but something to be continuously achieved—in a strong sense, it remains one of the unfinalizable projects of humanity. [28]

A transactional ethics, dialogical in form and content, cannot ever be achieved, is not, and never is: a transactional ethics always is becoming, a "(future) transactional ethics to come." An exemplary research project in which such an approach to ethics is consequently pursued took place in the context of an inner-city school of Philadelphia, where nearly 90% of students lived below the poverty line (e.g., ROTH & TOBIN, 2002). The schools we were working in and with are characterized by violence, absenteeism, and dysfunction. When their students were subjected to statewide testing procedures, these schools tended to end up on the bottom of the performance rankings. [29]

Initially conceptualized along the lines of empowerment, the researchers involved worked with students, teachers, administrators, and teachers in training. The research literally involved participating in schooling such that we did not allow ourselves to "observe" a lesson without actually contributing to teaching it. All researchers and observers were becoming integral part to the situation observed, practitioners among practitioners. We developed a set of guidelines that in essence constituted a non-additive, collective responsibility for teaching and learning (ROTH & TOBIN, 2002). Our research was to assist all involved in transforming the conditions. Thus, for example, following a lesson we (a researcher and responsible teacher educator) met with teacher, teacher-in-training, and student representatives. Sometimes the department heads were also involved. We discussed what worked, what did not work, and how to institute changes to turn things for the better. The discussions were very open and frank, where students articulated problems of teaching to the same degree that teachers might be in articulating issues of attention and behavior; or teachers and students alike acknowledged having behaved in ways that aggravated the problems during the lesson. As a result of this research the teaching-learning situation improved in the participating classes. In this situation, the research was indistinguishable from the effort of changing the conditions that the participants held together. These changes were based on the knowledge generated in the course of dialogue, which, because of its characteristics, we rightfully termed cogenerative dialogue; metalogues—a metalogue is a conversation about some problematic subject ... such that not only do the participants discuss the problem but the structure of the conversation as a whole is also relevant to the same subject" (BATESON, 1987, p.13)—served to articulate and represent, in a dialogical way, conclusions in the matter of arising within our researcher-practitioner team. [30]

The change in the condition of schooling certainly was a desirable outcome. But our work did not stop there. We also worked toward contributing to the research literature. However, rather than leaving publication to the academics, our writing process that followed our classroom-transforming cogenerative dialogue sessions also included all its members. Thus, for example, after investigating what could be learned from a lesson where a teacher had "screwed up" according to his own account, we published a research report that included a high school student, her teacher, a teacher-in-training, her supervisor, and the visiting researcher (ROTH, TOBIN, ZIMMERMANN, BRYANT & DAVIS, 2002). In that article, the two academics did not usurp and ventriloquize the voices of the other participants. Instead, choosing the transcription of cogenerative dialogues, emails, and other productions, all participants in the writer collective presented their own voices. In another instance, a teacher and his student had clashed in such a severe manner that an expulsion from school of the otherwise well-intended students was considered. Again, the researcher came together with the student, a teacher-in-training and master-of-arts-in-teaching student, her supervisor, the teacher, and a post-doctoral fellow who had worked with the student (ROTH et al., 2004). After having conducted interviews with the different stakeholders, all came together for a long meeting as a result of which the issue was resolved, the student could return to the classroom and continue on his trajectory toward academic success. In the published research paper, the key participants (i.e., teacher and student) spoke with and in their own voice rather than having others (e.g., academic researchers) speak for them. [31]

In all of this work, both in relation to teaching and research, co-responsibility was non-additive: with any one's failing, we all failed, and with any one's gain, we all gained. For example, with respect to teaching, actions manifested not only willingness to make place for the contributions of others but also willingness to take the place that was created. We conceived of a conductor-less orchestration of the lessons characterized by mutual respect. Students not only accepted a role as learners but also a role as teachers of teachers (e.g., on how to teach kids like them); teachers accepted their role as teachers as much as that of learners. The cogenerative dialogue sessions also had an associated list of heuristics—not formal ethical laws—that allowed participants to check whether the collective behavior provided evidence for mutual respect, rapport, inclusion of all stakeholders, constitution of an equitable playing field, and search for transformative potentials. [32]

Institutional ethics reviews of qualitative research projects fall short of the phenomenon of practical ethics—or, in other words, ethics in the mundane conduct of everyday life—because of their focus on researchers considered as elements imbued with certain characteristics rather than approaching the ethical relation as an irreducible unit. I exhibit an example of this failure in the way that institutional ethics committees approach the question of power, unilaterally attributed to the researcher. The position developed here situates ethical questions in the praxis of doing research, always involving researchers and participants alike. The questions concerning such a practical approach to ethics no longer can be answered by a researcher's institutional ethics committee because participants in general are not part of the institution but integral to the ethical praxis. Having been a member of an institutional research ethics committee and having served as its chair for three years, I am aware of the (collective) fear of some that individual researchers might be irrational. But such fears tend to be unfounded, for "the actually performed act in its undivided wholeness is more than rational—it is answerable" (BAKHTIN, 1993, p.29). As a community, we have to work harder to move further in working through the questions posed by a radical reformulation of ethics proposed here. [33]

The transactional perspective developed here certainly is not unfamiliar to many indigenous peoples, especially those with verb-based languages. Verbs manifest the relation between things in world continuously in progress (TRIPPETT, 2000). Associated with this way of articulating and thinking about the world is the co-thematization of the observer, which is integral to the transactional perspective as noted above. This is so "because when people understand their surroundings as comprising relationships between things, they cannot speak about the relationships without speaking about themselves" (p.15). What if we began to speak about researchers and participants using a verb-based discourse, which characterizes stakeholders in terms of what they do and situates all of them and their discourse in a relational world? The transactional perspective allows us to move beyond the anachronistic versions of ethics grounded in individuals and their interactions. Among others, the ethics and politics of institutional review boards—often unattended to by institutional review boards themselves (e.g., ROTH, 2004)—come into the focus in the transactional approach. [34]

1) All translations from other languages into English are mine. <back>

2) The square brackets "[" and "]" mark the beginning and ending of overlapping features in consecutive turns; the caret ">" marks turns of special interest; and transcriber comments are enclosed in double parentheses—e.g., "((inaudible))." <back>

Austin, John L. (1962). How to do things with words. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Bakhtin, Mikhail M. (1981). The dialogic imagination. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Bakhtin, Mikhail M. (1984). Problems of Dostoevsky's poetics. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Bakhtin, Mikhail M. (1993). Toward a philosophy of the act. Austin, TX: University of Austin Press.

Bateson, Gregory (1979). Mind and nature: A necessary unity. New York: E.P. Dutton.

Bateson, Gregory (1987). Steps to an ecology of mind. Northvale, NJ: Jason Aronson.

Battiste, Marie (2008). Research ethics for protecting indigenous knowledge and heritage. In Norman K. Denzin, Yvonna S. Lincoln & Linda Tuhiwai Smith (Eds.), Handbook of critical and indigenous methodologies (pp.497-510). Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Bhabha, Homi K. (1994). The location of culture. London: Routledge.

Chrétien, Jean-Louis (2007). Répondre: Figures de la réponse et de la responsabilité [Responding: Figures of response and responsibility]. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France.

Dewey, John (1938). Inquiry: The logic of scientific method. New York, NY: Henry Holt.

Dewey, John & Bentley, Arthur F. (1999 [1949]). Knowing and the known. In Rollo Handy & Edward C. Harwood (Eds.), Useful procedures of inquiry (pp.97-209). Great Barrington, MA: Behavioral Research Council.

Foucault, Michel (1975). Surveiller et punir: Naissance de la prison [Discipline and punish: Birth of the prison]. Paris: Gallimard.

Devereux, Georges (1968). From anxiety to method in the behavioral sciences. The Hague: Mouton.

Il'enkov, Evald V. (1977). Dialectical logic: Essays on its history and theory. Moscow: Progress.

Jefferson, Gail (1989). Preliminary notes on a possible metric which provides for a "standard maximum" silence of approximately one second in conversation. In Derek Roger & Peter Bull (Eds.), Conversation: An interdisciplinary perspective (pp.166-196). Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

Johannes, Robert E. (1981). Words of the lagoon: Fishing and marine lore in the Palau district of Micronesia. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Kant, Immanuel (1956 [1785]). Grundlegung zur Metaphysik der Sitten. In Immanuel Kant, Werke Band IV (pp.7-102). Wiesbaden: Insel Verlag.

Kirsh, David, & Maglio, Paul (1994). On distinguishing epistemic from pragmatic action. Cognitive Science, 18, 513-549.

Levinas, Emmanuel (1971). Le dit et le dire [The saying and the said]. Le Nouveau Commerce, 18/19, 21-48.

Livingston, Eric (2008). Ethnographies of reason. Aldershot: Ashgate.

Mavin, Timothy J.; Roth, Wolff-Michael; Soo, Kassandra & Munro, Ian (2015). Towards evidence-based decision making in aviation: The case of mixed-fleet flying. Aviation Psychology and Applied Human Factors, 5, 52-61.

Mead, George Herbert (1932). Philosophy of the present. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Mead, George Herbert (1938). Philosophy of the act. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Merleau-Ponty, Maurice (1945). Phénoménologie de la perception [Phenomenology of perception]. Paris: Gallimard.

Nietzsche, Friedrich (1922 [1885/1886]). Nachgelassene Werke: Der Wille zur Macht. Drittes und viertes Buch (2nd ed.). Leipzig: Alfred Kröner Verlag.

Noddings, Nell (2003 [1984]). Caring: A feminine approach to ethics and moral education. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Ricœur, Paul (1986). Du texte à l'action: Essais d'herméneutique II [From text to action: Essays on hermeneutics 2]. Paris: Éditions du Seuil.

Ricœur, Paul (1990). Soi-même comme un autre [Oneself as another]. Paris: Éditions du Seuil.

Roth, Wolff-Michael (2004). Un/political ethics, un/ethical politics. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 5(3), Art. 35, http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-5.3.573 [Accessed: February 10, 2018].

Roth, Wolff-Michael (2006). Collective responsiblity and solidarity: Toward a body-centered ethics. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 7(2), Art. 37, http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-7.2.123 [Accessed: February 10, 2018].

Roth, Wolff-Michael (2008). Auto/ethnography and the question of ethics. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 10(1), Art. 38, http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-10.1.1213 [Accessed: February 10, 2018].

Roth, Wolff-Michael (2013). Toward a post-constructivist ethics in/of teaching and learning. Pedagogies: An International Journal, 8, 103-125.

Roth, Wolff-Michael (2018). Autopsy of an airplane crash: A transactional approach to forensic cognitive science. Cognition, Technology & Work. DOI: 10.1007/s10111-018-0465-3

Roth, Wolff-Michael & Middleton, David (2006). The making of asymmetries of knowing, identity, and accountability in the sequential organization of graph interpretation. Cultural Studies of Science Education, 1, 11-81.

Roth, Wolff-Michael & Tobin, Ken (2002). At the elbow of another: Learning to teach by coteaching. New York: Peter Lang.

Roth, Wolff-Michael; Mavin, Timothy J. & Munro, Ian (2015). How a cockpit forgets speeds (and speed-related events): Toward a kinetic description of joint cognitive systems. Cognition, Technology and Work, 17, 279-299.

Roth, Wolff-Michael; Tobin, Ken; Zimmermann, Andrea; Bryant, Natasia & Davis, Charles (2002). Lessons on/from the dihybrid cross: An activity theoretical study of learning in coteaching. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 39, 253-282.

Roth, Wolff-Michael; Tobin, Ken; Elmesky, Rowhea; Carambo, Cristobal; McKnight, Yameer & Beers, Jen (2004). Re/making identities in the praxis of urban schooling: A cultural historical perspective. Mind, Culture & Activity, 11, 48-69.

Sacks, Harvey (1992). Lectures on conversation 1964–1972, Volume I & II. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Schütz, Alfred (1932). Der sinnhafte Aufbau der sozialen Welt: Eine Einführung in die verstehende Soziologie. Wien: Julius Springer.

Suchman, Lucy (2007). Human-machine reconfigurations: Plans and situated actions (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Trippett, Fran (2000). Towards a broad-based precautionary principle in law and policy: The functional role of indigenous knowledge systems (TEK) within decision-making structures. Master's thesis, Dalhousie University, Halifax, Canada, https://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/obj/s4/f2/dsk2/ftp03/MQ62360.pdf [Accessed: February 10, 2018].

von Glasersfeld, Ernst (1989). Facts and the self from a constructivist point of view. Poetics, 18, 435-448.

von Glasersfeld, Ernst (2001). Scheme theory as a key to the learning paradox. In Anastasia Tryphon & Jacques Vonèche (Eds.), Piaget: Essays in honour of Bärbel Inhelder (pp.141-148). Hove: Psychology Press.

von Glasersfeld, Ernst (2009). Relativism, fascism, and the question of ethics in constructivism. Constructivist Foundations, 4, 117-120.

Vološinov, Valentin N. (1930). Marksizm i filosofija jazyka: osnovnye problemy sociologičeskogo metoda v nauke o jazyke [Marxism and philosophy of language: Essays on its history and theory]. Leningrad: Priboj.

Vygotskij, Lev S. (2002). Denken und Sprechen. Weinheim: Beltz Verlag.

Waldenfels, Bernhard (2006). Grundmotive einer Phänomenologie des Fremden. Frankfurt/M: Suhrkamp.

Wolff-Michael ROTH is Lansdowne Professor of Applied Cognitive Science at the University of Victoria. His empirical works focuses on knowing, learning, and development across the lifespan, especially with respect to mathematical and scientific dimensions of life. His recent works include "Concrete Human Psychology" (Routledge, 2016) and, with A. JORNET, "Understanding Educational Psychology" (Springer, 2017).

Contact:

Wolff-Michael Roth

Faculty of Education

University of Victoria

MacLaurin Building A567

Victoria, BC, V8P 5C2

Canada

Tel.: +1-250-721-7764

Fax: +1-250-721-7598

E-mail: mroth@uvic.ca

URL: http://web.uvic.ca/~mroth/

Roth, Wolff-Michael (2018). A Transactional Approach to Research Ethics [34 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 19(3), Art. 1, http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-19.3.3061.