Volume 20, No. 3, Art. 3 – September 2019

A Millennial Methodology? Autoethnographic Research in Do-It-Yourself (DIY) Punk and Activist Communities

Nathan Stephens Griffin & Naomi Griffin

Abstract: In a recent MailOnline article, CLEARY described millennials as "entitled, narcissistic, self-interested, unfocussed and lazy" (2017, n.p.). The language echoed DELAMONT's (2007) critique of autoethnography, an approach to research that examines the social world through the lens of the researcher's own experience (WALL, 2016), a form of academic "selfie" (CAMPBELL, 2017). We offer two case studies of autoethnographic projects, one examining punk culture, the other examining the practice of veganism. We highlight the challenges we faced when producing insider autoethnographic research, drawing a parallel with criticism frequently levelled at the so-called millennial generation, specifically notions of laziness and narcissism (TWENGE, 2014). We argue that, though often maligned and ridiculed based on its perception as a lazy and narcissistic approach to research, autoethnography remains a valuable and worthwhile research strategy that attempts to qualitatively and reflexively make sense of the self and society in an increasingly uncertain and precarious world. Using case study evidence, we offer empirical support to WALL's (2016) call for a moderate autoethnography, which seeks a middle ground between analytic and evocative autoethnographic traditions.

Key words: autoethnography; Do-It-Yourself; punk; activism; veganism; millennials

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. Autoethnography

2.1 Understanding DIY punk as activism

2.2 Understanding veganism

3. Challenges of Autoethnography

3.1 Laziness

3.1.1 Ethics

3.1.2 Validity

3.2 Narcissism

4. Conclusions: A Millennial Methodology?

4.1 Autoethnography must be ethical

4.2 Autoethnography must be analytical

4.3 Autoethnography must be theorised

Autoethnography examines the social world through the lens of the researcher's personal experience (WALL, 2016). SPRY (2001) defines it as a "self-narrative that critiques the situatedness of self with others" (p.710), and ANDERSON (2006) highlights the "narrative presence" (p.375) of the researcher in the autoethnographic text. In practice, this usually entails introspective first-person accounts of the research process, often including emotional, personal, and self-conscious accounts of lived experience, rooted in a social, cultural, and historical context (ELLIS & BOCHNER, 2000; HOLT, 2003). Despite its critics, autoethnography continues to grow in popularity (DELAMONT, 2013; HOLMAN JONES, 2019; HURST et al., 2018; MUNCEY, 2010; WOODWARD, 2018). Whilst difficult to ascertain, it appears to be a particularly popular approach among PhD students (ATKINSON, DELAMONT & HOUSLEY, 2008; DENSHIRE, 2009; DOLORIERT & SAMBROOK, 2011; ELLIS, 2016; GRIFFIN, 2015; HAMOOD, 2016; STEPHENS GRIFFIN, 2015, 2017). Given the rapid encroachment of neoliberal values and audit culture within academia (SPARKES, 2007), the doctorate is perhaps becoming a last chance saloon for weird, risky, innovative, creative and challenging social science research, where post-doctoral opportunities skew towards safer, conventional, and politically neutral work. [1]

In this article, we provide a guarded defence of this popular but embattled research approach. To do this, two doctoral research projects are discussed as case studies. Each explored underground communities, in which we were participants, with each utilising autoethnography in different ways. The first example focussed on Do-It-Yourself (DIY) punk and other forms of cultural activism. The second examined veganism and animal advocacy from a situated vegan perspective. Autoethnography has been criticised from various quarters within the academy and beyond; it clearly sits in tension with more traditional, positivist research strategies, posing questions over rigour and validity (DOLORIERT & SAMBROOK, 2011), and wilfully breaking the rule that the scholarly work must always attempt to remain objective and dispassionate (CHARMAZ & MITCHELL, 1996). However, it has also been criticised by qualitative social-scientists, who worry it extends too far into solipsism (DELAMONT, 2013). It is also pertinent to note that autoethnography has been described as a punk method (ATTFIELD, 2011). [2]

We provide our initial justification for the use of autoethnography in each project, explaining how it was used and outlining findings and conclusions (Sections 2.1 and 2.2). We then discuss some significant challenges faced when conducting autoethnographic research, drawing a deliberate parallel with common criticism of the so-called millennial generation; these are split into two sections: laziness (Section 3.1) and narcissism (Section 3.2), each beginning with a provocation based on a combination of comparable critiques millennials and autoethnographers have faced. These provocations are designed to help illustrate our thesis. We describe how we addressed these challenges. To conclude, we argue that autoethnography is a valuable and worthwhile approach within qualitative research. We echo WALL's (2016) call for a "moderate autoethnography" (p.1), that is, an approach to autoethnography which attempts to balance the positive potentiality of innovation, imagination, and the representation of diverse perspectives with the pragmatic necessity to sustain "confidence in the quality, rigor, and usefulness of academic research" (p.2), arguing that this is achieved through ensuring autoethnographic work is ethical, analytical, and theoretical. [3]

ELLIS, ADAMS and BOCHNER (2011, §1) describe autoethnography as "an approach to research and writing that seeks to describe and systematically analyze personal experience (auto) in order to understand cultural experience (graphy) and personal experience (ethno)". Autoethnography, therefore, combines the principles of autobiography with ethnographic research techniques and is perhaps best understood as both an approach to, and product of, social research. It places the author within a project, providing a means of investigating the social world which is "grounded in everyday life" (PLUMMER, 2003, p.522). SPRY (2001) defines it as "a self-narrative that critiques the situatedness of self with others" (p.710). It is research in which "the self and the field become one‟ (COFFEY, 2002, p.320). Autoethnography "accommodates subjectivity, emotionality, and the researcher's influence on research, rather than hiding from these matters or assuming they don't exist" (ELLIS et al., 2011, §3). Autoethnography, arguably, sits comfortably with MERTON's notion of "sociological autobiography", which he defines as "sociological perspectives, ideas, concepts, findings, and analytical procedures to construct and interpret a narrative text that purports to tell one's own history within the larger history of one's times" (1988, p.18, in STANLEY, 1993, p.43). [4]

In practice, under the banner autoethnography, research can encompass a myriad of approaches (ELLIS & ELLINGSON, 2008). ANDERSON (2006) identifies two traditions. The first and most dominant tradition is "evocative autoethnography", which developed from a post-modern tradition and takes a descriptive literary approach. This is exemplified in ELLIS and BOCHNER's (2000) claim that within autoethnography "the mode of storytelling is akin to the novel or biography and thus fractures the boundaries that normally separate social science from literature ... the narrative text refuses to abstract and explain" (p.744). This necessitates a critique of the kinds of realist epistemological assumptions that typically underpin ethnography and social science research. The second tradition attempts to reconnect autoethnography with these traditional principles of social science research. ANDERSON describes this tradition as "analytic autoethnography", resting upon what would be typically understood as symbolic interactionist epistemological assumptions (2006). WALL (2016) succinctly summarises analytic autoethnography as "traditional ethnography with the personal commitments of the ethnographer made explicit" (p.2). [5]

Building on ANDERSON's work, LEARMONTH and HUMPHREYS (2012) highlight the potential dangers associated with each tradition. For example, the assertion within evocative autoethnography that storytelling should supersede analysis, so that the power of the writing is not sacrificed in the name of rigour, carries a risk of dispensing with the very reflexivity that autoethnographic approaches seek to establish. Telling autoethnographic stories about personal goals and values, without an analytic sense of their social and cultural situatedness, can depoliticise the social world under investigation, indirectly establishing normative conceptions of objectivity and neutrality (ibid.). However, an over-riding concern for analysis has the potential to sacrifice the evocative power of autoethnographic writing. [6]

As DELAMONT (2009) suggests, it is useful in light of these debates to return to BECKER's (1967) classic challenge to social scientists: "Whose side are we on?" (p.239) The question somehow simultaneously justifies, whilst also proscribes, autoethnography in practice. It challenges the idea that we can be objective in research, and therefore calls for sociologists to side with the oppressed and marginalised. Indeed, it follows MARX's (1994 [1845) assertion that philosophers have "only interpreted the world ... the point is to change it" (p.101). In embracing subjectivity, we facilitate reflexive research. In embracing epistemological uncertainty, we look beyond the search for a singular understanding of truth and acknowledge the messiness of the social world (LAW, 2004). But in embracing self-reflection and sacrificing rigour for creative writing, we risk silencing the voices of the very people BECKER was asking us to side with. [7]

Focusing on the purpose of research, autoethnography can be a means to amplify marginal or misrepresented voices or experiences. RICHARDS (2008) argues that non-normative or abnormal lives are controlled in how they are written about. People who exist outside of dominant social norms (such as disabled people) are often represented inaccurately. For example, as SULLIVAN describes, newspaper reporting of illness has a tendency to reduce individuals to the disease itself, instead of stories of how a disease has affected a person's life or biography (as cited in RICHARDS, 2008, p.1720). RICHARDS (p.1726), argues that autoethnography is therefore suited to addressing this problem of representation, and can also open up academic accounts of particular groups and experiences to laypersons, particularly where an academic belongs to a marginal or non-normative group. [8]

Autoethnography also shares characteristics with research traditions within queer studies. Autoethnographic research and queer studies each entail a deliberate focus on fluidity, intersubjectivity and the particular, and each questions and challenges dominant hegemony and normative discourse (GIFFNEY & O'ROURKE, 2009; HOLMAN JONES & ADAMS, 2010). Furthermore, HOLMAN JONES and ADAMS have argued that autoethnography is a queer method. Both refuse received notions of orthodox methodologies and focus on fluidity, intersubjectivity and responsiveness to particularities (PLUMMER, 2005; RONAI, 1995). In addition, they both place selves at their centre, whilst acknowledging the fluidity of self and experience as well as a critical political stance, challenging normative discourses and the status quo (DENZIN, 2006; WARNER, 1993). [9]

Having established autoethnography as a methodological approach, the following section outlines two autoethnographic case studies. These case studies share commonalities, in that they each were conducted as part of multi-methods PhD projects, and each involved research on communities within which the researchers regarded themselves as insiders. However, the case studies differ methodologically: the first case study on the topic of DIY punk reflects a more analytic approach (WALL, 2016), while the second, a study of veganism, takes a more evocative visual approach (ANDERSON, 2006). [10]

2.1 Understanding DIY punk as activism

This project was an autoethnographic study of DIY punk in North East England. It combined and integrated the disciplinary approaches of sociology, cultural studies and geography in a multi-methods research project. The autoethnographic approach adopted in this study aligns more closely with the analytic tradition summarised by WALL (2016) as "traditional ethnography with the personal commitments of the ethnographer made explicit" (p.2). A criticism of autoethnography has been that there is a lack of detailed guidance within the literature on how to actually do it, with a tendency toward "highly abstract" instructions on methods (WALL, 2006, p.152). Clearly and explicitly stating the way methods were used allows other researchers to establish a more systematic and rigorous approach in adopting similar methods. This does not have to be prescriptive but instead can serve as a starting point for finding an autoethnographic approach that works depending on the context. [11]

For Naomi's project, the use of autoethnography involved turning the spotlight on herself as a researcher to develop a better understanding of herself in relation to the research and to strengthen her findings, rather than a research goal being an attempt for her to understand herself. In practice this involved keeping a reflective analytic research diary, detailing her embodied experiences during the research process, as well as her emotional reflections through the course of the fieldwork. These data were then presented in the form of a number of autoethnographic vignettes. Traditionally, vignettes are used as a means of eliciting qualitative data from participants (BRAUN & CLARKE, 2013). Instead, Naomi included vignettes based on her own autoethnographic reflections in the final write-up to better contextualise the study, for example, by providing a vignette of a typical DIY punk show she attended during her fieldwork. This follows closely with the analytic autoethnographic tradition of producing ethnography with the personal reflections and standpoint of the ethnographer made explicit (WALL, 2016). [12]

The research explored the tactics that DIY punk participants employ in attempts to realise DIY ethics through the creation of DIY punk culture. DIY can be understood as an ethic, as well as a rallying call for autonomy and creativity, encouraging people to take political and cultural matters into their own hands. Participants are involved in the production of culture according to alternative criteria that the participants choose, for example, through art, crafts, music, and literature. The project's findings supported an understanding of DIY as championing an inherently anti-capitalist ethic that critiques corporate culture industries, such as the mainstream music industry, refusing to let profit-motivated imperatives dictate what cultural products are available and who is able to access cultural opportunities (DALE, 2009; HAENFLER, 2012; MOORE & ROBERTS, 2009). [13]

DIY, as an anti-capitalist ethic and movement, manifests in many forms and proponents of DIY employ numerous political and cultural tactics. The research also explored the significance of community in a DIY punk context. A coherently definable punk community does not exist as community itself remains a contested concept (FURNESS, 2012; GRIFFIN, 2012; O'CONNOR, 2008). However, the concept of a punk community remained meaningful to the research participants, even when participants highlighted its limitations. The research engaged with the concept of imagined communities (ANDERSON, 1991) through data analysis, proposing a definition which emphasises the importance of place, to account for DIY punk's complex geographies of space, global connections and local specificities. The research highlighted the complexity of cultural production and the interconnectedness of ethics, identity, community, and activism, which happen through DIY punk in multi-layered and multi-scalar ways. [14]

Naomi employed autoethnography, alongside ethnographic and interview methods. Due to her relationship with the field of study, and insider status as a punk participant, Naomi felt it important that she adopt a reflexive research strategy to interrogate her own positionality vis-à-vis the research. In practice, this entailed keeping an autoethnographic research diary, alongside fieldwork notes, interview notes and transcriptions. Naomi used this diary to document the process of the research, identifying emerging themes, complications encountered, new avenues for exploration, and personal experiences, feelings and concerns. This facilitated reflection during the process of data gathering and further reflection at different stages of the research. The benefits of keeping a reflexive research diary include recording "practical difficulties, emotional and intellectual concerns, and feelings of cultural and academic guilt" (PUNCH, 2012, p.86). The diary helped Naomi work through some of the anxieties and dilemmas she confronted whilst doing intimate insider or reflexive research. [15]

As discussed, autoethnography differs from more traditional ethnography with its attention to self-reflection by the researcher, and by placing the researcher within the research (CHANG, 2008). Here, Naomi reflected on her experiences as an active participant in the social phenomena that she was researching; she used observations, conversations and interviews typically found in ethnography, but also included personal experiences and reflections in data collection. For example, Naomi used experiences of organising a show to support the findings of her observations and interviews. Still, her experiences were not at the centre of the data collection and analysis. Through her insider position, Naomi also developed techniques to utilise autoethnographic methods within a broader ethnographic approach to acknowledge and utilise the benefits that autoethnography can provide. This navigated the criticisms of autoethnography, by combining it with other ethnographic methods. Naomi was able to reflect on her own experience as part of a DIY punk scene, using these reflections to support her research.

"I became interested in punk when I was about 14. After attending a few more corporate punk shows at larger venues, when I was a little older I discovered that regular hardcore punk shows were being held in my small town. These shows were held in a small community venue and were well attended. The shows would always get really raucous and were intensely exciting for me. Seeing something that seemed so wild and exciting happening in a town that I had always complained about being boring had a huge and long-lasting influence on me, and my relationship with the town. Since about the age of 17, I have been involved in organising shows" (Excerpt from Naomi's autoethnographic diary). [16]

The second project was a mixed multi-method study of veganism. It adopted a form of autoethnography that fits more closely into the tradition of evocative autoethnography (ANDERSON, 2006). Vegans eschew animal products like meat, dairy, eggs, and leather for ethical reasons (STEPHENS GRIFFIN, 2017), and is an increasingly significant and visible social phenomenon. Since 2014 the number of vegans in the UK has quadrupled (from 150,000 to 600,000) amounting to over half a million adherents (VEGAN SOCIETY, 2018). Veganism is also notable because of the scale and dominance of the system it seeks to reject (JOY, 2011). For example, over 1 billion animals are killed every year in UK slaughterhouses (VIVA!, 2013). Animal industries are so thoroughly embedded in almost every aspect of British daily life, it is difficult to imagine a world without them. And yet this is what vegans do. Academic research highlights a tendency for vegans to face hostility and ridicule (COLE & MORGAN, 2011; MacINNIS & HODSON, 2015). [17]

In this context, the project attempted to examine the experience of vegans from a reflexive, visual and biographical standpoint. Nathan explored the events and experiences that were significant in shaping the biographies of vegan animal advocates. He employed biographical interviews in which vegan participants had an opportunity to tell their life stories. He supplemented these lengthy interviews with visual methods and autoethnography. As well as being interviewed in depth about their experiences, participants were asked to produce comics about their lives. Comics are broadly defined, but can perhaps best be understood as a narrative juxtaposition of words and images, a form of sequential art (EISNER, 1985). In the study, comics were first used as a means of accessing visual and narrative accounts of veganism and vegan lives. O'NEILL and HARINDRANATH (2006) stress the importance of the visual to the field of biographical research, especially in representing the "unsayable". Biographical work, represented visually as well as textually, can help to illuminate the experience of individuals, and "bring us into contact with reality in ways we cannot forget" (pp.49-50). This, in turn, can provide a forceful counter-narrative to the hegemonic understandings of power and knowledge in society, and thus might allow the transgression of dominant understandings of veganism and animal advocacy, and potentially human-animal relations more broadly. [18]

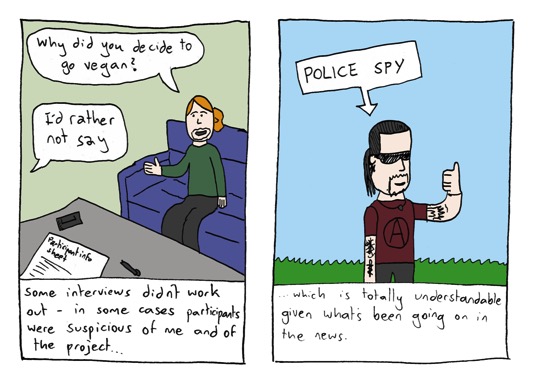

The use of comics also allowed the project to experiment with their value and potential in social sciences. In addition to participants producing comics, Nathan produced his own autoethnographic comic based on his experiences as a vegan, and as an account of the autoethnographic research diary he kept during the fieldwork (see Figure 1). The creation of a comic aligns more closely with the evocative autoethnographic tradition in which "the mode of storytelling is akin to the novel or biography and thus fractures the boundaries that normally separate social science from literature ... the narrative text refuses to abstract and explain" (ELLIS & BOCHNER, 2000, p.744 ). In doing so, the comic inhabited a space between research document and a creative, storytelling document. In producing a comic, Nathan visually underlined his own subjectivity, as a vegan, conducting the research. It also allowed him to explore his own reflections on the project in a non-typical medium, producing insights and ideas that might otherwise be absent. Furthermore, the comic aimed to promote participation and collaboration between researcher and participants. Hence, everyone produced a comic, as a visual account of their veganism.

Figure 1: Excerpt from Nathan's autoethnographic comic [19]

The main research findings were that simple definitions often overlook the complex biographical and social dynamics of veganism. In contrast to the very fixed rules that veganism is often reduced to, as a practice vegan identity is necessarily fluid across social situations. Examples of this were the "coming out" narratives participants presented, which illustrated the stigma and hostility they faced when divulging their veganism to others. Participants move in and out of vegan identity in social interactions. The research also found that vegan identity is performed and achieved in various embodied ways and that these processes intersect with other social structures such as gender and sexuality. The research found that having access to positive cultural narratives about veganism was also significant in participants' experiences, especially in prompting their initial interest in and eventual adherence to veganism. Finally, the research found that despite some difficulties, comics can function as both a means of representing research, as well as a legitimate method in social research. [20]

3. Challenges of Autoethnography

Having outlined two examples of the use of autoethnography in insider research projects, next we draw out some challenges associated with its use. We identify a conceptual link with dominant discursive understandings and criticisms of the millennial generation (TWENGE, 2014). More specifically, we address the twin accusations of laziness and narcissism. We deliberately frame the discussion under these headings to enable us to later question whether autoethnography can be understood as a "millennial methodology". The challenges of this methodology are outlined with a recognition of criticisms levelled at the use of autoethnography, alongside suggestions for how these problems can be addressed. [21]

Provocation: Like the lazy millennial lying in bed all day scrolling through Instagram on their iPhones, watching Netflix on their laptops, never having known the true meaning of hard work, the autoethnographer is by definition the bone-idle social scientist ...

A key criticism, made by DELAMONT (2009), is that autoethnography is lazy, both literally and intellectually. It allows the researcher to spend less time doing the difficult and time-consuming labour of fieldwork, and more time in the comfort of their home thinking about themselves. Furthermore, from an intellectual perspective, it is more difficult and time-consuming to theorise and parse data collected in the field from others, than it is to study oneself. Argued thus, the logic of the criticism is clear. [22]

However, this argument walks a tightrope in terms of arbitrating the labour of critical thought. Is simply thinking about something tantamount to being lazy? Is it more difficult to think about other people than oneself? The implicit assumptions underpinning this critique have also been used to denigrate qualitative research in comparison to quantitative research, through the assertion that qualitative approaches lack rigour (NOBLE & SMITH, 2015). Similar logic has been applied to disparage the social sciences compared with physical sciences, e.g., the notion of social science as a "micky mouse" degree (BROCKES, 2003). To dismiss autoethnography as intrinsically lazy is reductive. Invoking laziness risks reproducing two highly problematic tropes. The first is the right-wing populist trope of laziness variously levelled at intellectuals, students, academics, activists, trade unionists, migrants, disabled people, welfare recipients, and so on (GARTHWAITE, 2010; GILDERSLEEVE, 2017), the second being the trope of the neo-Calvinist culture of competition enshrined in the neoliberal academic sector, in which academics performatively compete over questions of whose workload is biggest, who is answering emails during the night, who has the least time for a social/family life. Instead of fighting a system which increasingly pays us less and treats us worse whilst demanding more, we compete over who is working the hardest. The slow scholarship movement explicitly rejects these trends (MOUNTZ et al., 2015) and broader issues relating to the neoliberalisation of academia in the UK were creatively identified and critiqued during the University and College Union Higher Education pension strike of 2018 (BERGFELD, 2018; CLARE et al., 2018). Nevertheless, it is worth applying the laziness critique in greater detail, through a discussion of laziness in relation to ethics. [23]

Autoethnography has been described as ethically problematic (DELAMONT, 2007). This is chiefly because, unless the author writes under a pseudonym, details about their autobiography will compromise the anonymity of those close to them. As WALL (2016) notes "there are always other characters in the story beyond the author, and it is important to consider how they are represented and included in the story" (p.4). For example, in Nathan's comic autoethnography, he described being raised as vegetarian by "hippy" parents. Whilst his parents did not object to him writing about his upbringing and their influence, he did not seek formal approval through them giving informed consent, and, in this sense, his ethical duty of care was arguably breached. Perhaps this is a case of ethical laziness. Nathan could have, once he had completed his autoethnographic account, asked for every person to give their informed consent to be mentioned (people mentioned in Nathan's autoethnography include his grandmother, his PhD supervisors, his close friends). In practice, Nathan made a judgement call; there was nothing defamatory or so personal as to not be public knowledge. Nathan did obtain informed consent from each of the people he conducted life-history interviews with, all of whom were anonymised. The distinction between those formally interviewed as part of the project and those who were part of its story can be understood as a grey area. Ultimately, the question of other characters in the story is a fairly fundamental challenge that autoethnographers face. [24]

It is worth remembering that no project is perfect, and no research is perfectly ethical. To carry out ethical social research, researchers need to resist box-ticking bureaucracy and adherence to rigid procedures and protocols as a way of eschewing their on-going responsibilities. They must instead aim to become ethical thinkers, who can appropriately respond to the often unanticipated ethical situations and dilemmas encountered in fieldwork, even after formal approval has been granted (CLARK & WALKER, 2011; DOWNES, BREEZE & GRIFFIN, 2013). Ethical considerations should be paramount throughout a project's duration, from inception to publication and beyond. Ethics is therefore best conceptualised as a continuing process. In Naomi's research, her role as a researcher was not always (or even often) easily distinguishable from her role as a punk participant (including her roles as a band member, show promoter and friend); different aspects of her life, identity and personality were intertwined. Though she attempted to draw distinctions between when she was and was not researching, there were occasions where events or conversations became more meaningful later, in relation to other data she collected subsequently, and so became data (DOWNES et al., 2013). This poses a challenge to traditional notions of informed consent and requires utmost care to protect the anonymity of those involved. As always, the academic value of such insights must be measured against one's duty of care to participants. Examples of these consent grey areas highlight the ongoing dynamic and negotiable nature of informed consent in ethnographic research, especially when the researcher is an insider, as these situations have the potential to arise unpredictably. TAYLOR (2011) explains that insider researchers need keen intuition to understand what information, provided by participants, could or should be deemed "off the record", and this is especially true of autoethnographic research. [25]

Whilst duty of care to others must always be an ethical priority, a further concern, which may be heightened due to the nature of autoethnographic research, is risk to the well-being of researchers themselves. This is something that applies more broadly, but it rarely discussed in methodology texts, nor do ethics boards tend to focus on it (DOWNES et al., 2013). Along with general safety concerns involving practical assurances that the researcher remains physically safe, there are also affective and emotional aspects of research. Autoethnographers open themselves to vulnerability by sharing personal stories. Before Naomi started her project, she was unprepared for the emotional turmoil that resulted from researching a field within which she was so embedded. Feelings of anxiety and conflict came from the ethical issues discussed above, as well as concerns about how to represent what she observed, especially if it might not be how the participants would have represented it. At various points throughout the research process, Naomi felt conflicted about researching people and spaces that she knew personally, feeling a degree of guilt due to her position as a researcher and the potential personal benefits that she may enjoy from the research. Also, the complexity of her "insiderness", as discussed above, caused her, at times, to feel "at once connected and estranged from one's social setting" (TAYLOR, 2011, p.5), which was difficult to navigate. In lieu of preparedness and academic texts advising about such inner feelings of conflict and stress, she found discussions with academic and "subcultural" peers to be invaluable. Perhaps this is why so much autoethnographic work becomes characterised by narratives of personal anguish (DELAMONT, 2007). [26]

In practice, good autoethnographers should be constantly weighing ethical questions. For example, during the course of Naomi's research, there were various instances of conflict within the community she researched. In some, Naomi knew people involved directly. When describing and discussing those conflicts, Naomi chose not to include autoethnographic reflections to preserve the anonymity of participants. If others were aware that Naomi knew people involved, they might be able to identify them. This is the kind of decision-making that goes into autoethnographic work; the author must weigh the ethical dimensions of a particular reflection. In Nathan's autoethnography, a key moment came in the form of a public argument he had with a senior academic from his institution, who Nathan decided not to name for ethical reasons. It might therefore be argued that, rather than being a case of encouraging intellectual and/or ethical laziness, autoethnography encourages a form of constant self-reflection and continual ethical appraisal which can benefit a project. Those wishing to use autoethnography must pay particular attention to ethics and not assume that because a project focuses on the self, it is exempt from ethical scrutiny. [27]

Traditional understandings of validity in social science research might challenge autoethnographic approaches as being lazy in terms of ensuring validity. Naomi necessarily engaged with issues around validity while conducting her highly reflexive analytic autoethnographic project. As ELLIS et al. (2011) discuss, "for autoethnographers, validity means that a work seeks verisimilitude; it evokes in readers a feeling that the experience described is lifelike, believable, and possible, a feeling that what has been represented could be true" (§34). [28]

The benefits of reflexivity as a methodological tool have become well recognised across social research in recent years, particularly in feminist scholarship. Reflexive research requires the researchers to place themselves within the work; it acknowledges that "all experiences, texts and ideas are open to multiple interpretations" (MAXEY, 1999, p.199) and it recognises the role of the researcher and respondent in the production of knowledge and development of the process (BERGER, 2015). For MAXEY (1999), reflexivity is necessary to understand and study real world concerns, as it does not claim authority for experience. When relating her own experiences, McLAREN (2009) illustrates both the meaning and benefits of being reflexive. Reflexivity strengthened her analysis by "... broadening my own discursively formed views by exposing how my constructions and subjective experiences interacted with my research" (p.2) Thus, it is essential that we recognise the part we play in the discourses and social phenomena that we explore to strengthen findings and validity. [29]

Again, as with ethics, a processual approach can be beneficial in questions of validity. Social researchers do not study a passive world, so reflection on the research process itself is required throughout for greater understanding and deeper analysis. WHATMORE (2003) proposes rethinking the research stage, regarding research as a process that seeks to contribute to understanding through the creation of knowledge events, rather than being about knowledge discovery or uncovering pre-existing truths. This requires recognition of the always limited, partial and iterative nature of the research process. Both WHATMORE (2003) and McLAREN (2009) support engagement with the unavoidable, like unpredictable factors that are beyond the researcher's control, yet have an impact on the research process. McLAREN (2009) maintains that reflexivity heightened their awareness of "the 'outer' social, cultural and discursive contexts of the research which strengthened the research findings" (p.1). [30]

In Naomi's research, she found herself needing to continually reflect on her influence on the research process. Given her embeddedness in the field, it was important for her to ensure that she maintained criticality throughout. Reflexivity is essential for ethical research (BERGER, 2015; GREGSON & ROSE, 2000; SULTANA, 2007) and can be utilised as a tool to increase its validity, by regularly critiquing and checking the researcher's positionality and influence. If we reflect on and try to critically engage with the research processes, then we can better assess its impact and strengthen validity. Reflection throughout acknowledges the influence of location, sensitivity of the topic, power relations and the social interaction between the ethnographer and those being researched, and strengthens the validity of the findings (HAMMERSLEY & ATKINSON, 1995). The use of reflexivity strengthened the validity of Naomi's research in several ways, including ensuring disclosure (that participants understood the research project and were happy to be involved), assessing the potential impact of their involvement and of the findings on the participants, and trying to uncover and reflect on Naomi's own impact on the research process. She sought to maintain a level of criticality by actively stepping back from the data to allow time to approach the transcriptions and observation notes with greater neutrality. She chose a reflexive and somewhat open research question to allow the research process to be guided by the themes emerging through literature and fieldwork rather than setting rigid aims from the start. She continually endeavoured to stay reflexive about her role and the expectations and influence of others through regular discussions with participants, returning to participants to clarify any uncertainties and speaking to others within the sub-cultural context. As well as this, she consulted with academic peers and supervisors who were less familiar with the subject matter at different stages of the research process. [31]

The following section discusses the charge of "Narcissism", which has been levelled at autoethnographic research approaches. [32]

Provocation: Millennials are the most vain, coddled and self-centred generation, constantly seeking external gratification, constantly over-sharing. What is autoethnography if not the social research equivalent of TMI?

A key criticism that those who pursue autoethnographic work must engage with is the charge of narcissism. As FINE (1999) has argued, using a highly reflexive approach can turn "the intensive labour of field research into the armchair pleasures of 'me-search'" (p.534). There is concern that using autoethnography as a data-gathering and analysis tool may lead to self-indulgent research outputs. There are risks in trying to reconcile analytical self-reflection with too much focus on the researcher (BRADLEY & NASH, 2011). ATKINSON (2006) maintains that autoethnography privileges experience at the expense of analysis, while ANDERSON (2006) argues that although autoethnography claims to be research, topic of study is only the researchers themselves. Such critiques deny the potential of autoethnography, which positions researchers within the research, and utilises personal experiences, knowledge, and position to study a topic or situation reflexively, rather than the researchers themselves (DENZIN, 2006). [33]

Various other problems can be attributed to the use of self as a data source (HOLT, 2003). Potential confusion over practical data produced in an autoethnographic research project is a key challenge. Writing up qualitative research always includes difficult decisions about what to include and what to leave out, and adopting an autoethnographic approach further complicates this tension. If everything personal is potentially relevant, how do you decide what makes it into the write-up? [34]

Acknowledging DELAMONT's (2007) observation that autoethnography tends to be about personal anguish, in writing his thesis Nathan decided to include data about his experiences with depression and anxiety. These mental health issues had been greatly exacerbated by the pressures of the PhD process. Mental health crisis appears to be increasingly common within academia, especially postgraduate students (FAZACKERLEY, 2018). Hence to counteract the silencing of experiences of mental illness, and to underline the connection between his own subjectivity, illness and the research itself, he felt it pertinent to discuss it. Nathan did so in a separate chapter of his autoethnographic comic, where he discussed a panic attack he had experienced at an academic conference, his feelings of embarrassment and humiliation, worries about his reputation, that other professionals would perceive him as mentally unequipped for an academic career and that it would impair his future employment prospects. He also discussed his subsequent decision to start taking medication to ease his symptoms. This afforded him an opportunity to discuss the pressures of research and be transparent about how mental illness had affected the project. Nevertheless, Nathan left out other personal problems, such as physical health issues, and aspects of his personal life and relationships even though each had potentially affected the research. This mirrors potential challenges in deciding which aspect of participants' narratives were worth including and which were cut. [35]

Thus, a concern in analysis, when researching communities and relationships we have a personal stake in, is the dilemma of making decisions about what to include. DeLYSER (2001) warns that researchers, with a prior level of familiarity with participants or the area of study, can become flooded by data due to the amount of their experiential and descriptive knowledge. Data collection is complex and embedded when one is researching in familiar territory. Having an overwhelming amount of data to work through can make analysis difficult, particularly initially. In an autoethnographic project, these problems are arguably more significant. Every thought, feeling, and experience within and outside of the research field is potentially relevant, so the researcher must decide what is significant, what is relevant and what to prioritise for discussion. This is further complicated by what the researcher finds is important to participants, competing with what may be significant or of interest to an academic audience and to those who fit both those criteria. The wealth of data gathered in familiar settings, which are not well researched, is reflected in analysis and write-up, through the need for detailed context setting. There are no simple solutions, and ultimately decisions over inclusion and exclusion of data and the subsequent justifications are the researcher's responsibility. These will differ, based on the nature of the project. [36]

In summary, we have outlined some challenges associated with the use of autoethnography, in particular, the charges of laziness and narcissism, as they relate to criticism of millennials, and ways in which the challenges associated with autoethnography can be mediated. As academics, our subsequent work has been informed by our experiences conducting autoethnographic research. For example, through the autobiographical reflections included in Nathan's book, which was otherwise based on empirical data from others (STEPHENS GRIFFIN, 2017). It is perhaps also interesting to consider that, as criticisms, laziness and narcissism seem intuitively compatible. For example, excessive self-interest can logically engender a degree of laziness around social relationships. Similarly, laziness in social relationships can logically provide a path to isolation and solipsism potentially feeding narcissism. Furthermore, it might be suggested that laziness, and narcissism are characteristics that people find easy to identify in others, but less so in themselves. [37]

Acknowledging GALE's (2018) focus on what writing does as opposed to what it means, we are interested to see where this article, as a synthesis of our autoethnographic case studies, will take us, and any subsequent conversations it opens up around the conceptual link between autoethnography and wider socio-economic contexts. [38]

4. Conclusions: A Millennial Methodology?

It is notable that the key criticisms of autoethnography, such as laziness and narcissism, parallel key criticisms of millennials in popular discourse. Academic interest in the millennial generation has highlighted labour market precarity as a distinctive problem facing millennials (MILKMAN, 2017) as well as providing evidence of declining concern for others among millennials compared to earlier generations (TWENGE, CAMPBELL & FREEMAN, 2012). In popular discourse, the millennial generation has been variously criticised as narcissistic, lazy, over-confident, self-obsessed, entitled and miserable (CLEARY, 2017; TWENGE, 2014). Arguably, in contrast to the preceding generation, millennial experience is characterised by existential uncertainty, financial insecurity, employment precarity, and overarching feelings of instability (BROWN, 2017; ROBERTS, 2018). Millennials work for less money, on increasingly unstable contracts, with fewer workplace rights, and with less chance of securing what were previously achievable aspirations, such as homeownership (BROWN, 2017; ROBERTS, 2018). Furthermore, they have become a go-to discursive scapegoat for all kinds of issues, from killing the institution of marriage (STEVERMAN, 2017) to killing off the sport of golf (SCHLOSSBERG, 2016). Millennials are so frequently maligned that the website Market Watch recently hosted an article compiling 17 things that "Millennials have been accused of killing" (PAUL, 2017: n.p.). While we draw this rhetorical comparison, in a somewhat "tongue-in-cheek" manner, it might be argued that a method rooted in acknowledging subjectivity, epistemological uncertainty and preoccupied with the self, has particular appeal and value in the present day. [39]

In an era of social media, it is commonplace for people to broadcast their often mundane, day-to-day biographies via the internet, be it selfies, pictures of food, videos of pets, or venting everyday frustrations. As participants, we observe mediated lives and project representations of our own lived experience into online social worlds. This continues the process by which we increasingly engage in viewing the constructed, possibly fictionalised, representations of other real lives through the internet and even reality television programmes. Autoethnography can perhaps be understood in this context, as an academic iteration of the necessity for critical reflection on the self, a form of scholarly selfie (CAMPBELL, 2017). Scholars can subject themselves to reflexive consideration and can do so with rigour and validity. It might, therefore, be useful to understand autoethnography as a quintessentially millennial methodology, preoccupied as it tends to be with the self, identity, and underpinned by existential uncertainty, perhaps even a sense of ontological precarity. Rather than damaging social sciences with navel-gazing, autoethnography can allow greater honesty and validity and, in some cases, a more robust and rigorous approach to self-reflection. Autoethnography has its place in a qualitative social science paradigm, and offers real benefits, especially in terms of creativity, imagination and creating better worlds and ways of living (BOCHNER, 2000) [40]

WALL (2016) argues that if the authors of autoethnographic work "wish to use them to make linkages between the micro and the macro, which is the stated purpose of autoethnography, there is a need for thick description, analysis, and theorizing" (p.6). To conclude, we support and echo WALL's call for a moderate autoethnography, in which the rigour of analytic tradition can be coupled with the creativity of the evocative tradition, to produce an autoethnographic approach that exemplifies the best of both worlds. Building on WALL's conclusions, some key ways in which this can be ensured are summarised as follows. [41]

4.1 Autoethnography must be ethical

Ethical considerations must be paramount in autoethnographic research, and like autoethnography itself, ethics can be best understood in processual terms. Careful consideration must be given to the other characters in the story being told and questions over what to leave out are as important as what to include. Alongside being ethical in terms of the research process, we would argue that autoethnography must also endeavour towards a common good. We agree when DELAMONT (2009) argues that sociology should focus on the less powerful not the more powerful and that many sociological research projects, including autoethnographic ones, risk looking in the wrong direction and benefiting the wrong people. Those considering conducting any kind of research, including autoethnographic research, should ask themselves qui bono? Who benefits from this research? Whose voices are heard and whose are not? [42]

However, it is wrong to assert that autoethnography is uniquely the endeavour of the privileged. DELAMONT's (2007) claim that "sociologists are a privileged group ... We are not paid generous salaries to sit in our offices obsessing about ourselves" (p.5) may be true sometimes. But DELAMONT's assertion is also instructive insofar as it carries assumptions about the lifestyle of those in academia. Since 2007, when this statement was made, it is fair to say that the character of society and academia has changed, and there has been a growing acknowledgement of intersectional dynamics of privilege in and beyond academia (CRENSHAW, 1989). Eight years into the harmful political project of austerity (COOPER & WHYTE, 2017), many find themselves struggling to get by, even in the academy's hallowed halls. There are many people working within academia or, perhaps even more importantly, seeking regular work in academia, who do not fit a picture of privilege and whose reflexive accounts of the social world can greatly benefit our understanding of society. The presupposition of a high salary appears a little reductive with today's growing acknowledgement of exploitation, casualisation, and precarity within the neoliberal academy. Furthermore, it is also possible to simultaneously inhabit a position of privilege in some regards, whilst not in others. The point being that autoethnographic accounts of the self can allow us to understand the social, and these can and should give voice to the experience of the marginalised. [43]

4.2 Autoethnography must be analytical

Autoethnography can be understood as the process of inter-relating fieldwork findings with the analysis of personal experiences, in a "combination of analysis and self-observation" (ATTFIELD, 2011, p.3). The approach recognises the researcher's limits and the embodied and experiential nature of the data gathering elements of research, rather than seeking and claiming objectivity and detachment. It might be reasonably assumed that the more creative and imaginative an autoethnography becomes, the greater the sacrifice regarding analysis. Indeed, in Nathan's autoethnographic comic, far more space was devoted to reflexively documenting the researcher's experience and the research process, than to detailed analysis of the topic of study. This visual autoethnography was part of a more conventional multi-method study (involving semi-structured interviews and autoethnographic observations), allowing Nathan space to expand elsewhere; but the lack of detailed academic examination of the topic within the comic limits its value as a stand-alone piece of academic work. There must be space within any autoethnography for in-depth systematic scrutiny of the topic, even if it is largely focussed on the self. This might, therefore, require that firm distinctions are made between, for example, an experiential account, and detailed analysis of this experience. How researchers reconcile this in practice, given the diversity of work is open to debate, but analysis allows autoethnographic work to flourish. Considering BOCHNER's (2017) vision of qualitative inquiry as an artful science which is concerned more with originality than rigour, the need to balance creativity with rigorous analysis is brought into question. The notion of scientific rigour is itself a social and cultural construct laden with problematic assumptions around objectivity and science. Indeed, "excessive focus on rigor impedes and distracts from talking about other, more important, problems such as the ethical commitments, moral importance, and artfulness of qualitative inquiry" (p.359). While BOCHNER's stance on rigour is compelling, an approach which does away with concern for rigour altogether may not suit all autoethnographers. In our projects there was a need to evidence rigour in the methods applied, done so through a reflective process of self-checking and drawing from other methods, such as qualitative interviews and ethnographic observations to support findings. The solution for autoethnographers may, therefore, lie not in a prescriptive, criteriological conception of rigour, but in an honesty and openness in relation to the creative reflections of the researcher, and to how those creative reflections have been produced and represented. [44]

4.3 Autoethnography must be theorised

As WALL (2016) discusses, poetry and storytelling are valuable established mediums, which have existed through human history and have done what evocative autoethnography seeks: to help us understand society and individual experience in a situated social context. However, these mediums have done so without an underpinning social scientific conceptual framework. Social scientists are, of course, free to create art and poetry, to write autobiographical stories informed by their academic research and expertise. If there is no theory and no analysis in the text itself, it is difficult to differentiate conventional forms of poetry and creative writing from autoethnographic work beyond examining an author's disciplinary background. Carolyn ELLIS (2004) famously stated, in defence of her own approach to evocative autoethnography, that

"I decided that it didn't matter whether my work was viewed as social science, or even sociology, and that I was as interested in the creative, artistic possibilities of what I was doing as I was in the scientific ones" (p.42). [45]

SPARKES (2007) similarly argues that autoethnography can set aside "conventional social scientific preoccupations in favour of factors like personal meaning, empathetic connection and identification to tell stories about 'embodied struggles'" (p.521). These arguments might suggest that theory is not important in autoethnographic work, but the opposite is true. Social and methodological theory has been crucial to the production of each of these author's work. Sociological theory is precisely what differentiates evocative autoethnographic work from traditional storytelling and creative writing, but a problem arises where theory is implicit. In terms of methodological theory, any well-constructed piece of research rests on the framework of a strong consistent and coherent theoretical framework. Furthermore, the outcomes and findings of a good piece of research will build upon and be linked back to social theory or, at the very least, will have implications for social theory. We all stand on the shoulders of those who came before us, and autoethnography is stronger when it is well theorised. [46]

We hope that in this article we have effectively illustrated some of the challenges faced when adopting autoethnographic approaches, especially in relation to broader questions about the approach's value. In offering these case studies, our intention has been to contribute to the debate constructively by providing empirical support for WALL's (2016) argument. In posing what might seem like a flippant question—Can autoethnography be understood as a millennial methodology?—we hope we have opened up a potential discussion around what it means to produce highly reflexive qualitative research, in what feels like an increasingly fractured and uncertain social world. [47]

We would like to thank the peer reviewers for their thoughtful and thorough feedback, as well as all the editorial team at FQS, particularly Dr. Katja MRUCK. We'd also like to thank Dr. Michaela GRIFFIN and Thomas RISELY for their valuable input.

Anderson, Benedict (1991). Imagined communities: Reflections on the origin and spread of nationalism. London: Verso.

Anderson, Leon (2006). Analytic autoethnography. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 35(4), 373-395.

Atkinson, Paul (2006). Rescuing autoethnography. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 35(4), 400-404.

Atkinson, Paul; Delamont, Sarah & Housley, William (2008). Contours of culture: Complex ethnography and the ethnography of complexity. Walnut Creek, CA: Altamira Press.

Attfield, Sarah (2011). Punk rock and the value of auto-ethnographic writing about music. PORTAL Journal of Multidisciplinary International Studies, 8(1), 1-11, https://epress.lib.uts.edu.au/journals/index.php/portal/article/view/1741 [Accessed: September 9, 2018].

Becker, Howard S. (1967). Whose side are we on?. Social Problems, 14, 239-248, https://www.sfu.ca/~palys/Becker1967-WhoseSideAreWeOn.pdf [Accessed: November 15, 2018].

Berger, Roni (2015). Now I see it, now I don't: Researcher's position and reflexivity in qualitative research. Qualitative Research, 15(2), 219-234.

Bergfeld, Mark (2018). "Do you believe in life after work?" The university and college union strike in Britain. Transfer: European Review of Labour and Research, 24(2), 233-236.

Bochner, Arthur P. (2017). Unfurling rigor: On continuity and change in qualitative inquiry. Qualitative Inquiry, 24(6), 359-368.

Bradley, DeMethra L. & Nash, Robert (2011). Mesearch and research: A guide for writing scholarly personal narrative manuscripts. Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing.

Braun, Virginia & Clarke, Victoria (2013). Successful qualitative research: A practical guide for beginners. London: Sage.

Brockes, Emma (2003). Taking the mick. The Guardian, January 15, 2003, https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2003/jan/15/education.highereducation [Accessed: January 30, 2019].

Brown, Jenny (2017). Millennials: The unlucky generation?. House of Commons Library, https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/social-policy/housing/millennials-the-unlucky-generation/ [Accessed: September 10, 2018].

Campbell, Elaine (2017). "Apparently being a self-obsessed c**t is now academically lauded": Experiencing twitter trolling of autoethnographers. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 18(3), Art. 16, http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-18.3.2819 [Accessed January 24, 2018]

Chang, Haewon (2008). Autoethnography as method. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press.

Charmaz, Kathy & Mitchell, Richard G. (1996). The myth of silent authorship: Self, substance, and style in ethnographic writing. Symbolic Interaction, 19(4), 285-302.

Clare, Nick; Field, Richard; Forsyth, Isla; Freeman, Cordelia; French, Shaun; Jewitt, Sarah; Langmead, Kiri; Legg, Steve; McGowan, Suzanne; Morris, Carol; Norcup, Jo; Seymour, Susanne & Soccorsy, Ellie (2018). Demanding the impossible: A strike zine, http://eprints.nottingham.ac.uk/51556/1/Nottingham%20Geographers%20Strike%20Zine.pdf [Accessed: February 15, 2019].

Clark, James J. & Walker, Robert (2011). Research ethics in victimization studies: Widening the lens. Violence Against Women, 17(12), 1489-1508.

Cleary, Belinda (2017). Millennials are entitled, narcissistic and lazy—but it's not their fault: Expert claims "every child wins a prize" and social media has left Gen Y unable to deal with the real world. MailOnline, January 6, 2017, https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-4093670/Millennials-entitled-narcissistic-lazy-s-not-fault-Expert-claims-child-wins-prize-social-media-left-Gen-Y-unable-deal-real-world.html [Accessed: November 6, 2018].

Coffey, Amanda (2002). Ethnography and self: reflections and representations. In Tim May (Ed.), Qualitative research in action (pp.313-331). London: Sage.

Cole, Matthew D.D. & Morgan, Karen (2011). Vegaphobia: Derogatory discourses of veganism and the reproduction of speciesism in UK national newspapers. The British Journal of Sociology, 62(1), 134-153.

Cooper, Vickie & Whyte, David (2017). The violence of austerity. London: Pluto Press.

Crenshaw, Kimberle (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex. University of Chicago Legal Forum, 139, 57-80.

Dale, Pete (2009). It was easy, it was cheap, so what?: Reconsidering the DIY principle of punk and indie music. Popular Music History, 3(2), 171-193.

Delamont, Sarah (2007). Arguments against auto-ethnography. Paper presented at the British Educational Research Association Annual Conference, Institute of Education, University of London, 5-8 September, http://www.leeds.ac.uk/educol/documents/168227.htm [Accessed: September 28, 2018].

Delamont, Sarah (2009). The only honest thing: Autoethnography, reflexivity and small crises in fieldwork. Ethnography and Education, 4(1), 51-63.

Delamont, Sarah (2013). Performing research or researching performance? The view from the martial arts. International Review of Qualitative Research, 6(1), 1-18.

DeLyser, Dydia (2001). "Do you really live here?" Thoughts on insider research. Geographical Review, 91(1/2), 441-453.

Denshire, Sally (2009). Writing the ordinary: Auto-ethnographic tales of an occupational therapist. Doctoral thesis, education, University of Technology, Sydney, Australia, https://opus.lib.uts.edu.au/handle/10453/21897 [Accessed: October 20, 2018].

Denzin, Norman (2006). Analytic autoethnography, or déjà vu all over again. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 35(4), 419-428.

Doloriert, Clair & Sambrook, Sally (2011). Accommodating an autoethnographic PhD: The tale of the thesis, the viva voce, and the traditional business school. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 4(5), 582-615.

Downes, Julia; Breeze, Maddie & Griffin, Naomi (2013). Researching DIY cultures: Towards a situated ethical practice for activist academia. Graduate Journal of Social Sciences, 10(3), 100-124, http://gjss.org/sites/default/files/issues/chapters/papers/Journal-10-03--05-Downes-Breeze-Griffin_0.pdf [Accessed: January 12, 2019].

Eisner, Will (1985). Comics and sequential art. Tamarac, FL: Poorhouse.

Ellis, Carolyn (2004). The autoethnographic I: A methodological novel about autoethnography. Walnut Creek, CA: Altamira

Ellis, Carolyn (2016). Preface: Carrying the torch for autoethnography. In Stacy Holman Jones, Tony Adams & Carolyn Ellis (Eds.), Handbook of autoethnography (pp.9-12). New York, NY: Routledge.

Ellis, Carolyn & Bochner, Arthur P. (2000). Autoethnography, personal narrative, reflexivity. In Norman K. Denzin & Yvonna S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (2nd ed., pp.733-768). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Ellis, Carolyn & Ellingson, Laura L. (2008). Autoethnography as constructionist project. In James A. Holstein & Jaber F. Gubrium (Eds.), Handbook of constructionist research (pp.445-465). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Ellis, Carolyn; Adams, Tony E. & Bochner, Arthur P. (2011). Autoethnography: An overview. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 12(1), Art. 10, http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-12.1.1589 [Accessed: July 14, 2018].

Fazackerley, Anna (2018). Universities' league table obsession triggers mental health crisis fears. The Guardian, June 12, 2018, https://www.theguardian.com/education/2018/jun/12/university-mental-health-league-table-obsession [Accessed: September 10, 2018].

Fine, Gary A. (1999). Field labor and ethnographic reality. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 28(5), 532-539.

Furness, Zack (2012). Introduction: Attempted education and righteous accusations. In Zack Furness (Ed.), Punkademics: The basement show in the ivory tower (pp.5-24). Brooklyn, NY: Minor Compositions.

Gale, Ken (2018). Madness as methodology: Bringing concepts to life in contemporary theorising and inquiry. Abingdon: Routledge.

Garthwaite, Kayleigh (2010). "The language of shirkers and scroungers?" Talking about illness, disability and coalition welfare reform. Disability and Society, 16, 369-372.

Giffney, Noreen & O'Rourke, Michael (Eds.) (2009). The Ashgate research companion to queer theory. Surrey: Ashgate.

Gildersleeve, Ryan E. (2017). The neoliberal academy of the anthropocene and the retaliation of the lazy academic. Cultural Studies, Critical Methodologies, 17(3), 286-293.

Gregson, Nicky & Rose, Gillian (2000). Taking Butler elsewhere: Performativities, spatialities and subjectivities. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 18(4), 433-452.

Griffin, Naomi (2012). Gendered performance and performing gender in the DIY punk and hardcore music scene. Journal of International Women's Studies, 13(2), 66-81, https://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws/vol13/iss2/6/ [Accessed: May 10, 2019].

Griffin, Naomi (2015). Understanding DIY punk as activism: Realising DIY ethics through cultural production, community and everyday negotiations. Doctoral thesis, sociology, Northumbria University, UK, http://nrl.northumbria.ac.uk/30251/ [Accessed: May 10, 2019].

Haenfler, Ross (2012). Punk ethics and the mega-university. In Zack Furness (Ed.), Punkademics: The basement show in the ivory tower (pp.37-48). Brooklyn, NY: Minor Compositions.

Hammersley, Martin & Atkinson, Paul (1995). Ethnography: Principles in practice (2nd ed.). London: Routledge.

Hamood, Tariq (2016). An autoethnographic account of a PhD student's journey towards establishing a research identity and understanding issues surrounding validity in educational research. The Bridge: Journal of Educational Research-Informed Practice, 3(1), 41-60.

Holman Jones, Stacy & Adams, Tony E. (2010). Autoethnography is a queer method. In Kath Browne & Catherine J. Nash (Eds.), Queer methods and methodologies: Intersecting queer theories and social science (pp.373-390). London: Ashgate.

Holman Jones, Stacy (2019). Living an autoethnographic activist life. Qualitative Inquiry, 25(6), 527-528.

Holt, Nicholas L. (2003). Representation, legitimation, and autoethnography: An autoethnographic writing story. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 2(1), 18-28, https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/160940690300200102 [Accessed: May 6, 2019].

Hurst, Samantha; Macauley, Karen A.; Awdishu, Linda; Sweeney, Kathleen M.; Hutchins, Sophie S.; Namba, Jennifer M. & Zheng, Amy M. (2018). An autoethnographic study of interprofessional education partnerships. Journal of Research in Interprofessional Practice and Education, 7(1), 1-13, https://www.jripe.org/index.php/journal/article/view/262/144 [Accessed: May 10, 2019].

Joy, Melanie (2011). Why we love dogs, eat pigs, and wear cows: An introduction to carnism. San Francisco, CA: Conorai Press.

Law, John (2004). After method: Mess in social science research. Oxford: Routledge.

Learmonth, Mark & Humphreys, Michael (2012). Autoethnography and academic identity: Glimpsing business school doppelgängers. Organization, 19, 99-117.

MacInnis, Cara C. & Hodson, Gordon (2015). It ain't easy eating greens: Evidence of bias toward vegetarians and vegans from both source and target. Group Processes and Intergroup Relations, 20(6), 721-744.

Marx, K. (1994 [1845]). Theses on Feuerbach. In Lawrence H. Simon (Ed.), Karl Marx: Selected Writings (pp.98-101). Indianapolis, IN: Hackett Publishing Company.

Maxey, Ian (1999). Beyond boundaries? Activism, academia, reflexivity and research. Area, 31(3), 199-208.

McLaren, Helen J. (2009). Using "Foucault's toolbox": the challenge with feminist post-structural discourse analysis. Paper presented at Foucault: 25 years on. Centre for Post-colonial and Globalisation Studies, Adelaide, The Hawke Research Institute, University of South Australia, http://www.unisa.edu.au/siteassets/episerver-6-files/documents/eass/hri/foucault-conference/mclaren.pdf [Accessed: May 10, 2019].

Milkman, Ruth (2017). A new political generation: Millennials and the post-2008 wave of protest. American Sociological Review, 82(1), 1-31.

Moore, Ryan & Roberts, Michael (2009). Do-It-Yourself mobilization: Punk and social movements. Mobilization: An International Quarterly, 14(3), 273-291.

Mountz, Alison; Bonds, Anne; Mansfield, Becky; Loyd, Jenna; Hyndman, Jennifer; Walton-Roberts, Margaret & Curran, Winifried (2015). For slow scholarship: A feminist politics of resistance through collective action in the neoliberal university. ACME: An International E-Journal for Critical Geographies, 14, 1235-1259, https://acme-journal.org/index.php/acme/article/view/1058 [Accessed: May 10, 2019].

Muncey, Tessa (2010). Creating autoethnographies. London: Sage.

Noble, Helen & Smith, Joanna (2015). Issues of validity and reliability in qualitative research. Evidence-Based Nursing, 18, 34-35.

O'Connor, Alan (2008). Punk record labels and the struggle for autonomy: The emergence of DIY. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

O'Neill, Maggie & Harindranath, Ramaswami (2006). Theorising narratives of exile and belonging: The importance of biography and ethno-mimesis in "understanding" asylum. Qualitative Sociology Review, 2(1), 39-53, https://minerva-access.unimelb.edu.au/handle/11343/34604 [Accessed: May 6, 2019].

Paul, Kari (2017). Here are all the things millennials have been accused of killing- from dinner dates to golf. Market Watch, October 12, 2017, https://www.marketwatch.com/story/here-are-all-of-the-things-millennials-have-been-accused-of-killing-2017-05-22 [Accessed: September 6, 2018].

Plummer, Ken (2003). Intimate citizenship: Personal decisions and public dialogues. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press.

Plummer, Ken (2005). A note from the editor. Sexualities, 8(1), 5-6.

Punch, Samantha (2012). Hidden struggles of fieldwork: Exploring the role and use of field diaries. Emotion, Space and Society, 5(2), 86-93.

Richards, Rose (2008). Writing and the othered self: Autoethnography and the problem of objectification in writing about illness and disability. Qualitative Health Research, 18(12), 1717-1728.

Roberts, Yvonne (2018). Millennials are struggling. Is it the fault of the baby boomers?. The Guardian, April 29, 2018, https://www.theguardian.com/society/2018/apr/29/millennials-struggling-is-it-fault-of-baby-boomers-intergenerational-fairness [Accessed: September 15, 2018].

Ronai, Carol R. (1995). Multiple reflections of child sex abuse: An argument for a layered account. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 23(4), 395-426.

Schlossberg, Mallory (2016). Millennials are killing the golf industry. Business Insider, July 1, 2016, http://uk.businessinsider.com/millennials-are-hurting-the-golf-industry-2016-7?r=US&IR=T [Accessed: September 10, 2018].

Sparkes, Andrew C. (2007). Embodiment, academics, and the audit culture: A story seeking consideration. Qualitative Research, 7, 521-550.

Spry, Tami (2001). Performing auto-ethnography: An embodied methodological praxis. Qualitative Inquiry, 7(6), 706-732.

Stanley, Liz (1993). On auto/biography in sociology. Sociology, 27(1). 41-52.

Stephens Griffin, Nathan (2015). Queering veganism: A biographical, visual and autoethnographic study of animal advocacy. Doctoral thesis, sociology, Durham University, UK.

Stephens Griffin, Nathan (2017). Understanding veganism: Biography and identity. Cham: Palgrave.

Steverman, Ben (2017). Young Americans are killing marriage. Bloomberg, April 4, 2017, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-04-04/young-americans-are-killing-marriage [Accessed: September 10, 2018].

Sultana, Farhana (2007). Reflexivity, positionality and participatory ethics: Negotiating fieldwork dilemmas in international research. ACME: An International E-journal for Critical Geographies, 6(3), 374-385, https://www.acme-journal.org/index.php/acme/article/view/786 [Accessed: October 31, 2018].

Taylor, Jodie (2011). The intimate insider: Negotiating the ethics of friendship when doing insider research. Qualitative Research, 11(1), 3-22.

Twenge, Jean M. (2014). Generation me—revised and updated: Why today's young Americans are more confident, assertive, entitled—and more miserable than ever before. New York, NY: Atria Books

Twenge, Jean M.; Campbell, Keith W. & Freeman, Elise C. (2012). Generational differences in young adults' life goals, concern for others, and civic orientation, 1966–2009. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 102(5), 1045-1062.

Vegan Society (2018). Statistics. Vegan society, https://www.vegansociety.com/news/media/statistics [Accessed: February 21, 2019].

Viva! (2013). About us. Viva international voice for animals, https://www.viva.org.uk/what-we-do [Accessed: May 2, 2014].

Wall, Sarah S. (2006). An autoethnography on learning about autoethnography. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 5(2), 146-160, https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690600500205 [Accessed October 31, 2018]

Wall, Sarah S. (2016). Toward a moderate autoethnography. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 15(1), 1-9, https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1609406916674966 [Accessed: May 10, 2019].

Warner, Michael (Ed.) (1993). Fear of a queer planet: Queer politics and social theory. Minnesota, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Whatmore, Sarah. (2003). Investigating the field: Introduction. In Michael Pryke, Gillian Rose & Sarah Whatmore (Eds.), Using social theory: Thinking through research (pp.67-71). London: Sage.

Woodward, Kath (2018). Auto-ethnography. In Carol Costley & John Fulton (Eds.), Methodologies for practice research: Approaches for professional doctorates (pp.137-148). London: Sage.

Nathan STEPHENS GRIFFIN is a lecturer in criminology at Northumbria University. His research interests include animal advocacy, environmentalism, and other forms of political activism, with a particular interest in the criminalisation of political protest. He is also interested in biographical, visual and graphic narrative approaches to social research.

Contact:

Nathan Stephens Griffin

Department of Social Sciences,

Northumbria University,

Newcastle upon Tyne, NE1 8ST, UK

Tel.: +44 (0)191 243 5083

E-mail: nathan.stephens-griffin@northumbria.ac.uk

Naomi GRIFFIN is a researcher in the Department of Sport and Exercise and the Department of Sociology at Durham University. Her research interests include social justice movements and activism, identity, inequality, children and young people & education, social policy and animal advocacy. She also has an interest in discourse analysis.

Contact:

Naomi Griffin

Department of Sociology,

Durham University,

Durham, DH1 3HN, UK

Tel.: +44 (0)191 334 1231

E-mail: naomi.c.griffin@durham.ac.uk

Stephens Griffin, Nathan & Griffin, Naomi (2019). A Millennial Methodology? Autoethnographic Research in Do-It-Yourself (DIY) Punk and Activist Communities [47 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 20(3), Art. 3, http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-20.3.3206.