Volume 21, No. 1, Art. 5 – January 2020

The Experience of Power Relationships for Young People in Care. Developing an Ethical, Shortitudinal and Cross-National Approach to Researching Everyday Life

Hélène Join-Lambert, Janet Boddy & Rachel Thomson

Abstract: Across national contexts, research shows that young people who live in child protection facilities often have negative experiences of power relations. In this article we look for a suitable method which takes account of power relations while investigating young people's perspectives on their everyday lives. We first present the results of an international methodological literature review concerned with the study of everyday life of young people, including ethical discussions arising among researchers. Drawing on this, our own research devised a shortitudinal, qualitative and cross-national approach which was designed to empower young participants during the research process. Sixteen young people living in care in France and in England participated in this project. Here we discuss the ways in which this approach functioned to give participants control—over the use they made of the research tools, over the topics that were discussed, and over the spaces in which research data were generated. Some of the data show how young people's choices reflect the areas where they feel powerful. We argue that using this method enabled insights into the ways in which young people were able to create or protect agentic spaces within the constrained everyday lives of child protection.

Key words: mobile methods; shortitudinal approach; power in research; everyday life; out-of-home placement; child protection; France; United Kingdom

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. Lessons From Previous Research

2.1 Disempowerment of young people in care

2.2 Research can develop methods that empower young people in care

2.3 Approaches to explore young people's everyday life

3. Young People's Power in the Research and in Everyday Life

3.1 A qualitative approach

3.2 How the cameras gave control to participants

3.3 The shortitudinal approach and empowerment

4. Conclusion: A Cross-National Approach to Power Relationships

Child welfare research internationally reveals poor outcomes in the transition to adulthood, relative to the general population (STEIN & MUNRO, 2008). There are several factors to explain these difficulties. Before entering care, some young people suffer violence or neglect by their own parents from an early age, creating psychological disorders which may lead to repeated disruptions in out-of-home placements and hinder successful adaptation after care (FRECHON & ROBETTE, 2013; POTIN, 2012). After leaving the system that has completely cared for them, these young adults find themselves without any support from parents or practitioners (BODDY, BAKKETEIG & ØSTERGAARD, 2019; HEDIN, HÖJER & BRUNNBERG, 2012; STEIN, 2012). [1]

Furthermore, while they are in care, young people grow up in contexts that are determined by the absence of their parents and the importance of legal, administrative and institutional rules. Young people who grow up away from their parents face a number of issues; some of which are common to all children and young people while others are specific to growing up in care. Whether they are in residential care or in foster families, their everyday lives are often different from the lives of the majority of young people. In his definition of social pedagogy, Hans THIERSCH (2005) emphasizes the everyday as a central concept in the theory and practice of work with vulnerable young people. The everyday, he argues, is a product of society, policy and institutions, and it builds the dynamic context in which upbringing happens. According to THIERSCH, we need to understand these everyday experiences in order to address young people's needs and agendas. [2]

In order to understand how the context of care affects young people's future plans and their transitions to adult lives, we decided to study young people's everyday lives while in care in two countries, England and France. Our cross-national approach was designed to illuminate layers of context in individual biographies, thus illuminating the lived experience of child welfare systems (BODDY et al., 2019; BRANNEN & NILSEN, 2011). The purpose of our research was to hear from young people themselves what was important to them. We developed a research method which aimed to be sensitive to ethical aspects of interviewing young people in care and appropriate for gathering comprehensive data about all aspects of their day-to-day lives. Through this article we will demonstrate the strength of a qualitative, cross-national longitudinal approach while addressing these objectives. [3]

In this article we will first present the lessons from previous research in a range of countries regarding the power relationships experienced by young people in care (Section 2.1), and ways in which researchers have addressed the power issue when asking young people in care to participate in research (Section 2.2). Second, we will present findings from international research showing specific methods that have been developed to study young people's day-to-day lives (Section 2.3). Based on this literature review, we will describe the approach we have followed (Section 3.1) and show how it contributed to empowering participants during the investigation process (Section 3.2.). Finally, some of the data will be used to provide evidence about how young people's everyday life contributes to empowering them, and how our approach has revealed this (Section 3.3). [4]

2. Lessons From Previous Research

2.1 Disempowerment of young people in care

Scholars in childhood and youth studies have for many years highlighted the ways in which intergenerational justice and injustice is shaped by the structural vulnerability of children, "which is not a biological reality but rather children's lack of power and status within our societal structures" (POWELL & SMITH, 2006, p.135). SPYROU (2019) has argued for attention to materiality, complicating understandings of childhood agency by recognizing intra-activity, and the interdependent relationalities of all our lives. Such concerns are arguably particularly acute for children and young people in care, because the affordances for agency in their lives are shaped in distinctive ways by their dependence on the state. As Judith BUTLER observed:

"Once groups are marked as 'vulnerable' within human rights discourse or legal regimes, those groups become reified as definitionally 'vulnerable', fixed in a political position of powerlessness and lack of agency. All the power belongs to the state and international institutions that are now supposed to offer them protection and advocacy. Such moves tend to underestimate, or actively efface, modes of political agency and resistance that emerge within so-called vulnerable populations" (2016, pp.24-25). [5]

Her comments prompt us to consider what this marking as "vulnerable" means for young people in care—and for their encounters with research. Research using qualitative methods has highlighted the kind of power relations young people in care are involved in. Twenty years ago, Klaus WOLF has shown how children and young people living in child protection care were put in a position where they were not listened to when they expressed their feelings or wishes: "the belief that these children have behavioral disorders, deficits due to their social background or learning disabilities easily lead to their experience not being seen as important and especially their critiques being interpreted as signs of their disorders" (WOLF, 1999, p.22; our translation). WOLF's research showed that young people "had often experienced that others made decisions about their place of living, while they were not involved in these decisions and decisions had not been explained to them" (ibid.). At the same time, they felt they were unable to control themselves, so they needed carers to control them, had low self-esteem and were scared of life after the end of care. [6]

Since WOLF's initial research, non-participation of children and young people in decisions about their own lives has been pointed out as an issue in child protection internationally. This relates to decisions ranging from everyday issues to long term decisions (JOIN-LAMBERT, 2006). In their everyday life in a residential home, for instance, research has evidenced young people's feeling of over-regulation of the use of time and space as well as restrictions on their autonomy in areas such as privacy and negotiation processes (SCHAFFNER & REIN, 2013, p.73). Another typical situation where young people cannot make their own decisions is when they want to see their friends in the evening while they live in a foster family. In France, because the parents still have parental authority, a young person would need to get authorization from their parents or social worker prior to making a late visit, which means these kinds of plans need to be made well in advance, rather than spontaneously like most young people like to do. The same is true when young people want to visit their parents: depending on the placement order, contact with parents and siblings might be regulated very strictly and children and young people cannot make their own decisions about when they want to visit them—which they sometimes experience as disempowering (POTIN, 2012, p.157). [7]

Long-term decisions typically include choices in education and changes in the care setting. Sonia JACKSON and Claire CAMERON's cross-national study showed that young people's wishes are not taken into consideration when deciding about their future plans. "They lacked career guidance and were often given poor advice. They are under pressure to opt for short-cycle occupational training in order to become economically independent as soon as possible" (2011, p.8). [8]

Often educational pathways of young people in care are influenced by decisions about their place of living—whether they would stay in the same place, change placement or go back to live with their parents. One of the young people interviewed by Emilie POTIN described her feeling of not being listened to: "I am obliged to change all my plans again only because my father makes a claim on me. This means that, actually, they don't really take account of what I say. I'm not listened to much, either" (2012, p.187; our translation). Because adults and young people do not have the same agenda, "while the social workers believed they were listening, and could describe detailed efforts they had made to elicit children's views, the young people, in the main, did not feel they had been heard" (McLEOD, 2007, p.280). [9]

Comparing participation of children and young people in evaluation procedures in France and Germany, Pierrine ROBIN (2013) shows how little influence her interviewees remember having on care decisions. The young people say they were not informed about the reasons for their placement, and it took them a long time to understand. Those who had initially asked for help remember having been listened to and helped, with some exceptions leading to young people running away from home to avoid danger. Even when they are asked about their opinion, young people find it difficult to be listened to, because adults tend not to believe them. As a result, ROBIN writes, children and young people in child protection tend to just resign themselves and keep silent. Several researchers have come to the same conclusion: "the lack of opportunities made available to them to make decisions about their own lives" leads to "feelings of helplessness, low self-esteem and poor confidence" (LEESON, 2007, p.268). Similar results were found among Russian young people about to leave care: in Gania ZAMALDINOVA's (2010) research, almost all young people said they were scared and anxious about leaving the care institutions. [10]

As researchers who are looking into young people's lives, it is crucial that we acknowledge the lack of agency and participation that is experienced by young people in care even more than by other young people. If we aim to discover how young people's lives are shaped and what influences them, we need to create spaces where they will feel listened to. [11]

2.2 Research can develop methods that empower young people in care

Narrative scholars such as Catherine RIESSMAN (2000) and Michelle FINE (2016) have written about the importance of open methods that allow the researcher to hear counter stories, challenging the claims of dominant narratives. RIESSMAN observes that, "in the empirical world, there are countless instances in which individuals disavow dominant perspectives" (2000, p.114). As researchers, we have an ethical responsibility to enable that disavowal. For example, the historian Carolyn STEEDMAN (2000) has written about "enforced narratives" (p.25)—the stories that can be told about the lives of the marginalized and stigmatized. She writes:

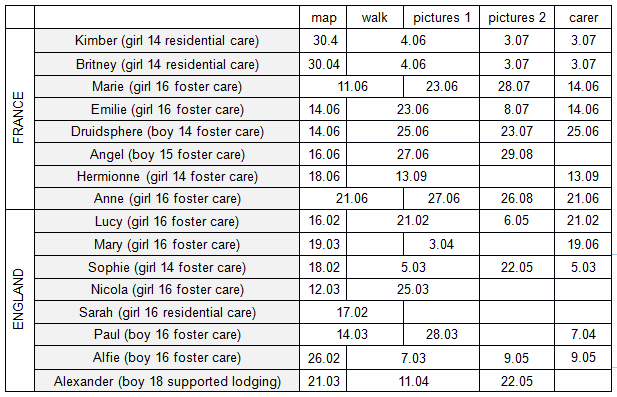

"Is the possession of a terrible tale, a story of suffering, desired, perhaps envied, as a component of the other self? [...] to do with a bourgeois self that was told in terms of a suffering and enduring other, using the themes and items of other, dispossessed and difficult lives" (p.36). [12]

In this we see what Michel FOUCAULT (1982) described as a dividing practice—a practice of exclusion and objectification. The "other self" is constructed through the terrible tale, a construction that highlights difference, rather than mutual recognition. As researchers, in a position of relative privilege and power, we must recognize the risk of dehumanizing the "other" when we focus only on their vulnerability or problems. STEEDMAN (2000) was writing about Victorian philanthropy, but her account of documenting "the themes and items of other, dispossessed and difficult lives" (p.36) evokes a practice very familiar to social researchers. And, as scholars such as McLEOD (2007) and WOLF (1999) have noted, a situation where an adult interviews a child or a young person is influenced by the inequality of power between them, even more so if the child is dependent on the child welfare system. When researching with groups—such as young people in care—whose characteristics or circumstances lead them to be defined as vulnerable, there is a heightened ethical imperative for methodologies aim to rebalance power, and create space to hear a different story. FINE (2016, p.53) quotes W.E.B. DuBOIS, asking in 1903 "How does it feel to be a problem?" A number of researchers have chosen to organize their data collection in ways that can be understood as a response to this challenge. [13]

One way is to combine ethnographic observations and interviews, so the interviews are part of a longer process allowing the researcher to build a rapport with young people. With this method, "people who are being studied are seen as acting independently in the research process and not only as objects" (WOLF, 1999, p.27; our translation). This classical ethnography was used in studies in different countries. The observations of the dynamics of group relationships in a Scottish home conducted by Ruth EMOND lasted for a whole year. She was living in a room just like the young people in care, who had invited her to do so with the aim of understanding "what it was like to live in a children's home" (2005, p.123). As in other observation-based studies (OSSIPOW, BERTHOD & AEBY, 2014), the relationships she was building with young people were central to her investigation. According to her, "that young people have a level of control over the pace of the research appears to make a significant impact on the success of the ethnographic relationship" (EMOND, 2005, p.133). [14]

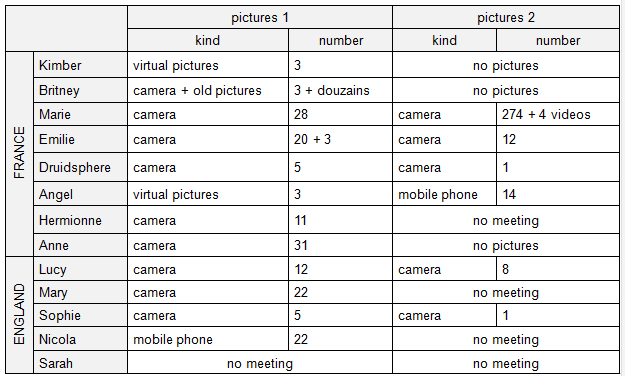

Ethnographic observation allows the investigation to follow the flow of events as driven by participants. The researcher does not give any specific direction regarding what young people might talk about. This addresses McLEOD's conclusion that "if we want to truly hear young people's voices we have to find out what is on their agenda rather than impose our own" (2007, p.284) because "powerlessness can shape the responses of those who are marginalized" (p.285). [15]

Innovative ways of doing ethnography with young people in care have been developed in the (Extra)Ordinary Lives study (ROSS, RENOLD, HOLLAND & HILLMAN, 2009). Here, the methodological approach makes young people's perspectives on their lives visible. The relationships that are built with the researchers over time, as well as their strong commitment to ethical considerations, allow trust, supporting young people in making decisions about sharing and reflecting on sensitive issues. In this study, young people made use of their right to stop recordings, and to listen to them prior to accepting that they would be analyzed by researchers. The study involved long-term (one year and longer) relationships between the researcher and young people. [16]

The multi-faceted approach is not only important ethically and practically, but also aids substantive understanding. For instance, the way in which it records dialogues between young people rather than young people giving an interview gives voice to young people's own issues:

"Keely and Jolene's shared experiences of having contact with their birth families and then returning to foster carers creates a very different dynamic than the conversations that occurred between the researchers and the participants. A phrase such as being 'back off contact', between Jolene and Keely, needs no further explanation" (HILLMAN, HOLLAND, RENOLD & ROSS, 2008, p.6). [17]

In Sarah WILSON's and Elisabeth MILNE's (2013) study, sensory prompts such as music, sound and visual images scaffold young people's articulation of their relationships with people and places, bringing insight into the dynamic complexity of experiences that may otherwise be reduced to static "outcomes." [18]

Other attempts to address power imbalances have been made through a peer research approach in the cross-national study of SOS Children's Villages (STEIN & VERWEIJEN-SLAMNESCU, 2012), as well in a French study (ROBIN, MACKIEWICZ & ACKERMANN, 2017). In both cases, peer researchers were involved at all stages: to design suitable methodology, to decide upon topics to investigate, to conduct peer-to-peer interviews and to analyze the data. The underlying idea is that "young people are likely to feel more comfortable being interviewed by a peer who is of similar age and care background than by an adult" (STEIN & VERWEIJEN-SLAMNESCU, 2012, p.7). In ROBIN and colleagues' (2017) research, participants could choose who would interview them: man or woman, same age or older, and so on. Peer researchers were also involved in sampling, as participants were chosen not only from lists given by service providers but also from the peer researchers' own networks. These examples show the potential of peer-research methodology to address ethical as well as practical issues such as engagement and involvement of young people over time. [19]

The end of the research is an important moment with regard to young people's participation. The first aspect pointed out by researchers is that the end of a trustful relationship built between the researcher and the young people must be well-prepared:

"These children were likely to have experienced a number of changes in carers and indeed many of their relationships. It was therefore vital that the ending of the project, and our relationship, were as planned and structured as the earlier part of the work" (EMOND, 2005, p.131). [20]

In order not to create a feeling of abandonment among participants, the researcher needs to make things clear before the end. It is also important to give the young people an opportunity to see the results of the research they have contributed to. Often, researchers will provide feedback to participants in the last phase of the study, as did Melanie MCCARRY:

"The research team returned to the Young People's Advisory Group with the edited version and they were astonished that some of their suggestions had been incorporated. This proved to be a critical point in our relationship because it demonstrated our commitment to listening and valuing their contributions" (2012, p.62). [21]

Power is a critical aspect of relationships between adults and young people, specifically in a public care context. Qualitative methods offer many ways of taking the issue of power relations into account when investigating children's and young people's life in care. [22]

2.3 Approaches to explore young people's everyday life

Recent studies on transitions from youth to adulthood in the general population tend to investigate everyday lives from the perspective of young people, in order to uncover themes such as identity building and political citizenship. Two examples of research show how everyday lives can be approached with different methodologies. Aufwachsen in Deutschland: Alltagswelten (AID:A) [Growing Up in Germany: Everyday Worlds] is a large-scale survey conducted by the German Youth Institute in 2009 on a panel of 25,000 participants. The aim is to examine the everyday lives of young people at different ages and focuses on how young people become independent, take on responsibilities, participate in decisions in private and public life, and make the change from school to the world of work (RAUSCHENBACH & BIEN, 2012). Inventing Adulthoods started in 1996 in the UK as a multi-method and multi-layered study working with young people aged 11-17 years. The researchers used a questionnaire with 1,800 respondents, alongside 62 focus groups involving 356 young people, research assignments with 272 participants and interviews with 57. Ten years later, some of the young people had been interviewed up to seven times by the team, using qualitative methods such as lifelines and memory books in order to gather detailed data about the everyday lives of the participants at different times (HENDERSON, HOLLAND, McGRELLIS, SHAPRE & THOMSON, 2007). [23]

Through both studies, we get insight into the contexts of growing up, the people and institutions involved in young people's lives, their experiences in the areas of leisure, media, community life, education, work, partnerships and family-building, as well as the everyday structures of family lives. In the AID:A survey, data was gathered at one point in time for all the participants, and analyzed separately for different age groups (RAUSCHENBACH & BIEN, 2012). This contrasts with the design of following up young people over time using repeated interviews (THOMSON, 2003) which not only needs a longer period of fieldwork but also involves the practical and conceptual work required to link together the different episodes of fieldwork into a synthetic account of change and continuity over time (THOMSON & HOLLAND, 2005). The individual case studies of Inventing Adulthoods give an insight into what and who are important to young people, how these priorities change over time, and what factors determine young people's choices. This takes into account individual trajectories as well as contexts of family, community and society more globally (THOMSON, 2007). Despite their differences in approach, both studies show the salience of a focus on everyday practices for gaining an understanding of the transition to adulthood. [24]

Another longitudinal study—Young Lives—was conducted with children and young people living in poverty in four different countries. It investigated 12,000 children using both a quantitative and a qualitative approach. The qualitative part was designed to gather participants' perspectives and aspirations:

"How does poverty interact with other factors at individual, household, community and intergenerational levels to shape children's life trajectories over time?' The qualitative research is explicitly based on the premise that children's experiences and perceptions are a major resource for providing answers to this question" (MORROW, 2017, p.2). [25]

As in research with children in care: "the asymmetries of power between adult researchers and young participants living in conditions of poverty has required careful consideration" (CRIVELLO, MORROW & WILSON, 2013, p.6). Together with semi-structured interviews and observation, creative tools were used for collecting children's perspectives and narratives, including a community time-line, community mapping and guided tours, networking activities, and various creative tools for involving children in the research, linked to specific themes explored by the researchers. [26]

Very little research has been undertaken to specifically explore the day-to-day life of children and young people living in child protection custody. Most research on this population focuses on the outcomes of care, more specifically in early adulthood. However, as HOLLAND, RENOLD, ROSS and HILLMAN remind us: "Prioritising futures and 'outcomes', however, neglects children's everyday, 'now', experiences and the complex relationship between their past, present and future" (2008, p.4). [27]

In a few studies mentioned above on the present-day experiences of children and young people in care, the most common method was ethnographic observation. The ethnographic approach in its classic version urges the researcher to identify what is meaningful in people's and groups' lives by observing them rather than projecting one's own priorities onto the research. Thus, OSSIPOW, AEBY and BERTHOD (2013) had initially started a study on identity building processes and the feeling of belonging in residential care in Geneva. During the observation, however, it turned out that the issue of autonomy of young people was what young people and carers were talking about all the time when asked about identity. As a result, autonomy became a major focus of the research. [28]

The approach which was developed in the (Extra)ordinary Lives project aimed at understanding the meanings children attached to their stories, "how they understand themselves and their relationships with others" (HOLLAND et al., 2008, p.7). This study ran over one year, during which pictures and video were used to give young people the opportunity to present themselves. During this time, researchers built relationships with young people and recorded what they had to say about their lives, at different times: "At the beginning of our research fieldwork most of the young people answered our questions briefly and politely. After a period of time they talked in much more depth about their everyday experiences. They were also much less polite!" (p.20) [29]

Innovative, playful methods where young people in care are asked to be creative and choose what they wish to talk about have been used in the past. These methods are helpful in terms of giving participants a choice over the topics they want to talk about, in order not to impose the researcher's view on their narratives. Investigating the everyday lives of young people over time allows for an understanding of the relationship between previous and present experiences in terms of key aspects of everyday lives such as relationships, life skills and recognition. [30]

3. Young People's Power in the Research and in Everyday Life

The ELTA (Everyday Lives: (Re)Conceptualizing Transitions to Adulthood for Young People in Care) project which is presented here was conducted at the University of Sussex (UK). One of the main objectives of this project was a methodological experiment designed to examine the everyday lives of young people in care in France and England, in a way that would acknowledge the power imbalance that young people might experience as part of their life in care, and avoid stigmatization through the research process itself. [31]

The case study methodology developed to study the everyday lives and relationships of young people in public care was derived from the literature review briefly presented above. In addition, informed by methods devised for a study of everyday family lives (PHOENIX, BODDY, WALKER & VENNAM, 2017), it included activities like social mapping, guided walks, and digital photos. The purposes were to get young people to choose the topics, places, people, and objects that were relevant to their everyday lives and that they wanted to talk about, to make the research experience enjoyable and interesting to them and to keep in touch with them over time. Within the project, case studies of 16 young people in care were conducted in England and France, including three interviews with each young person within a time frame of 6 to 12 weeks and one with their caregivers. We called this repeated interviewing over a short period of time "shortitudinal." Altogether, 74 interviews (including consultation interviews) were conducted between December 2013 and September 2014. The methodology included interviews based on social mapping, guided walks, and digital photos as supports for narrative interviews, and texting as a way of keeping in touch. Social mapping consisted of drawing a map with places that are important in their everyday life, while commenting on these places. For the guided walks, or "walking interviews," young people were asked to choose places that were important to them. These walks provided a space for informal discussion, and for giving young people opportunities to take some control over the data generation process (VAN DER VAART, HOVEN & HUIGEN, 2018). This also enables the interviewer to ask for more narratives on their everyday life. Photos are taken with a digital camera given to the young person during the first interview. The camera was a gift which could be kept after the end of the research. Young people chose what they wanted to take pictures of, and at the next interview they showed the photos, or some of them, and commented on them to describe what is important in their everyday life. This not only gives insight to their lives but also gives participants more power within the research relationship: "By enabling the co-researcher to produce the images that are the focal point for discussion, the method creates the space for the co-researcher to build the context and provide the setting for research questions" (WOODGATE, ZURBA & TENNENT, 2017, §3). In this research, young people could construct the image they wanted to share with the researcher (JOIN-LAMBERT, 2017). According to previous ethnographic research, it thus contributes to "a levelling of the power imbalance between researchers and participants" (KOLB, 2008, §12). All places, those for the guided walk as well as those for the other interviews, were chosen by young people, as "a small opportunity to empower participants in the research process" (ECKER, 2017, §10). Furthermore, this is a way of researching young people's lives through the places they feel connected with, which allows for an analysis of the spatial dimension of their experience (BECKER, 2019). Texting was one of the ideas developed in order to keep in touch with young people between the rounds of interviews, following a method developed by HEDIN et al. (2012). Additionally, Facebook turned out to be useful for contacting some of the participants. In the following data, all names have been replaced by pseudonyms, some of which were chosen by the young people themselves.

Table 1: Overview of the data collection with young people [32]

At the beginning of the first individual meeting with each young person, information about the purposes of the research, the rights of the participants, and the tasks included in their participation, were explained to them in great detail. Although they all had received an information sheet and some of them had attended information meetings, these reminders were crucial in order to make sure that they had understood the implications of their participation before signing the consent sheet. [33]

The tool that best allowed the young people to choose the topics they wanted to talk about and allowed the researcher to follow up over time was digital photos. For this reason, we will describe the use made of it by the participants in more depth. At the end of the first meeting, the young people were given digital cameras with memory cards and batteries and they were asked to take pictures of things, people, and places that were important to them in their daily lives. They were asked to bring the camera to the next meeting in order to show the pictures of their choice and to talk about them. If they wanted to take pictures of other people, they needed to ask them for permission before showing the pictures to the researcher. They were also reminded that pictures would not be published by the research team in any way. [34]

3.2 How the cameras gave control to participants

All but one participant agreed to meet at least a second time, and out of those (15), 13 showed some pictures at the second meeting. The pictures had been taken on the research-camera in 12 cases, and on their mobile phones in one case. The two others talked about "virtual pictures." Eleven young people agreed to meet a third time. After one meeting where a young person had forgotten to bring their camera, the researcher then systematically reminded young people, via a text message, to bring their camera to the meeting. However, only six young people actually showed pictures on the research-camera the second time. One other showed pictures from their mobile phone, and four did not show any pictures at all. The three young people who did not bring the camera to the second meeting did not bring it to the third one either, so of the 15 cameras handed out in the first interviews, three never appeared again.

Table 2: pictures shown by participants [35]

The number of pictures young people took with the "research camera" ranged from 0 to 274 for each meeting. In cases when there were too many pictures to look at within the framework of the interview, young people were asked to choose those they wanted to talk about. The topics chosen by young people varied. Sofas, beds and bedrooms were selected by nine, while five took pictures of their school buildings, and bus stops appeared in three cases. Friends appeared only in two cases, while brothers and sisters were present in three cases and the foster families or young people from the foster home also in three cases. Four young people did not take any pictures of people, although they took some that were closely linked to important people in their lives, for example, presents from their mother. Several of them showed pictures of themselves when they were small: one 14-year-old English girl had her picture hanging on the wall of her room, a 14-year-old French girl had stored pictures of her childhood on a memory card, which she allowed the researcher to look at with her during the interview. [36]

These numbers and the variety of topics in the pictures reveal that this tool was very effective. The fact that the research was done using a camera—a familiar yet creative tool—made it enjoyable and unusual. Young people felt free to take none, few or many pictures, and to talk about the topics they wanted. Nevertheless, the topics they chose were all related to the question they had been asked initially: about what was important to them in their everyday life. [37]

In some cases, they decided not to bring the camera to the meeting, although they did agree to talk about pictures they had taken or thought of for the research, or to show pictures taken with their mobile phones. In two cases when young people did not bring the camera to the second meeting, they agreed to describe the pictures they had taken (or would have taken). This "virtual picture" approach appeared to be productive in both cases. One boy had taken pictures but had forgotten to bring the camera to the meeting, saying that he did not think his pictures were really interesting. One girl said she did not take the pictures because she thought that, as the researcher was going to her place for the meeting anyway, she had better show her the rooms rather than taking pictures of them. They mentioned three pictures each, with one of the three being the bed or the bedroom. [38]

Angel (boy, foster care, France, 16 years old) describes the two pictures he took, but did not bring to our meeting. The first one was his bed: "because my bed, it's my friend. My big friend forever; even though it changes all the time."1) The second picture he describes is the rabbit, which was in the garden at that moment because of the warm weather. He says: “there are no more”, he only took these two pictures. But then he adds: "I could have taken another picture of the garden: Because in the garden, I play football and basketball and when the weather is nice, we have dinner in the garden. We chat and all the family is there." So, although he did not show these pictures, the way Angel describes them says a lot about what is important in his everyday life, which is very valuable for the research. [39]

In a similar way, while we were going to the room where the interview would take place, Kimber (girl, institutional care, France, 14 years old) showed me the computer room, the living room, and her bedroom, were she pointed more specifically at her bed (there were two beds in the room) and at a picture of her beautiful mother hanging on the wall. She then commented on the importance of these places during the interview. In these cases the cameras were handed out in the first meeting and were never seen again. However, without the cameras these two young people possibly would not have anticipated the pictures they wanted to take, so the camera did serve as a tool to get the descriptions of the virtual pictures as well. [40]

In the cases when the young people used their mobile phone, it became clear that the pictures they showed during the study were not taken for this purpose. These were common photos: pictures of themselves, of people they love, the kind of pictures you want to keep with you. Nicola (girl, foster care, England, 16) is one example: "They always take pictures together" (Nicola's friend talking about Nicola and her mum). [41]

However, there are also pictures of unusual situations and places. In the following example, the picture taken with the mobile phone is that of an unusual event in the girl's life, when she was next to a horse:

Researcher: So this is half of you?

Nicola: No, it's so you can get the horse in. [42]

When asked to go back to this picture to talk more about it, she did not talk about the horse (the unusual element), but about friendships:

Researcher: Whose horse is it?

Nicola: I don't know, it's just a random horse because my friend lives on xxx Farm and there was a horse.

Nicola's friend: There's loads of horses there.

Researcher: What's the name of this friend?

Nicola: Mary.

Nicola's friend: We're not friends anymore. [43]

In this sequence we understand that the picture of Nicola and a horse, which she took because it is untypical of her everyday life, gave rise to a discussion about the relationship with the former friend. This highlights the importance of friendships in her daily life, and is therefore completely relevant within the framework of the study. [44]

The use young people make of the pictures stored in their mobile phones is the same in France and in England: they show them very quickly, jumping from one to the next, often not really giving the researcher a chance to see it properly, let alone to ask questions about the link between the picture and their daily lives. As in this other discussion with Nicola:

Nicola (describes a picture in her mobile phone): Me, ready for my job interview.

Researcher: Wait a minute please, can you go back? Nicola: For my job interview.

Researcher: You're very beautiful. Nicola: Thanks.

Researcher: So when was that? Do you mind just taking them one after another so we can talk about each one?

Nicola: Wait, can I just show you this one? [45]

Apart from the comments young people made on some of these pictures, what became evident is that the use of the mobile phone is in itself a crucial part of their everyday life, just like taking and showing pictures with it. The good thing about pictures is that you can make and show them even when you run out of credit. The way in which some of the young people addressed the request to take pictures of their everyday life and to talk about them was not always as we had planned it. However, their reaction is an indicator of the control they felt they had about their participation in the study. By asking young people to take pictures with the camera, we were asking them to do something that is not a part of their everyday life. Furthermore, those who decided to show us pictures from their mobile phone instead were allowing us to see what actually plays a great part in their everyday life. So this method was an efficient way of giving control over the topics they wanted to discuss. [46]

3.3 The shortitudinal approach and empowerment

During the research, young people first met in groups when the project was presented to them so that they could decide whether they wanted to participate or not. Those who agreed were then met up to three times within a period of three months. At each meeting they were reminded about the purpose of the study. At the two first meetings they were asked to get prepared for the next meeting by taking pictures and choosing a route for the guided walk. The repeated meetings over a short period of time, which we later called the "shortitudinal" method, gave young people the opportunity to anticipate the topics they wanted to discuss with the researcher. Even though this anticipation was not necessarily conscious, their choices were not made randomly. In answer to our question "what is important in your everyday life?" many of the pictures, places and people they showed and talked about highlighted areas where they felt confident and powerful. [47]

At the first meeting, when asked to describe one of the places she mentioned during the social mapping phase, Lucy, a 15-year-old English girl living in foster care said:

Lucy: They are a training corps. We're part of a training corps at ... it's just like a huge ... don't really know how to describe it (...) We do 5-aside football as well, and each have a squadron versus another squadron and we just do every squadron against each other and then it leads to a pointing structure and then at the end of the year we have like the best sports squadron and [our squadron] keeps coming second to [other squadron], which is another squadron, but recently [the other squadron] did quite poorly.

Researcher: So you're the best?

Lucy: We're kind of edging up. So hopefully in 2014 we'll be the best sports squadron. [48]

After a long description, she added: "Actually I got promoted on Thursday to Caporal." At the second meeting, she showed pictures of the uniforms she wears when she goes to the training corps: "that's my blues. And then that's a brassard and those shoes and the brassard I wear with the blues." Wearing the uniform appeared to be very important in Lucy's everyday life; she cared a lot about her clothes and shoes, and enjoyed getting dressed for the training corps. She had three different uniforms for that:

Lucy: With the blues, there's also light blues which is a Wedgewood blue shirt that you do up to the neck and it chokes you, and a black tie that goes with it instead of the dark blue, and that's seen as the number ones. And you make sure your shoes are extra shiny when you wear them. (...)

Researcher: So does it take you a bit of time to get dressed before you go [there]?

Lucy: About 20 minutes because I've got to get my hair properly in a bun and I've got to pin it all up and get rid of any like little funny bits and then get into that uniform and put my boots on which takes about five minutes just for the boots because they're quite big and they've got quite a lot of mess. (...)

Researcher: Everybody goes dressed up like that?

Lucy: Yeah. It is a big thing and it's part of obviously the [training corps], and we represent them and it's part of looking all as one and looking really smart.

Researcher: And you like it?

Lucy: Yeah, I like it. [49]

Being promoted was one of the reasons for Lucy to feel recognized. Another reason was that this was the place where she met her boyfriend. Also, she enjoyed "looking really smart" when she went there. The repeated meetings in a short time, and the use of the pictures led Lucy to talk about this organization on several occasions and to let us know how much she enjoyed it. [50]

Druidsphere, a 14-year-old French boy living in foster care, was not very talkative, answering most of the questions with "mmm" or "yeah." The only exception was when talking about his tablet and all the activities linked to it. In the first meeting, the social map showed that the most important place in his life is his room, where he says he spends a lot of time on his tablet. Although he also watches movies and plays the piano with his tablet, the most important activities are playing video games and chatting online with his mum and his sisters. Playing games is important because it gives him the opportunity to chat online with playmates, and it also gives a topic to talk about with schoolmates:

Researcher: So what do you talk about then with your friends?

Druidsphere: About games. [51]

Games facilitate Druidsphere's communication with his peers, whether at school or online. At the third meeting, when asked to explain the rules of his favorite game, his answers show that this is an area where he is really in control. He is also good at playing the games:

Druidsphere: No, actually, I'm at level 22 and I need level 24 (...)

Researcher: So you're not bad if you have level 22?

Druidsphere: Yeah. [52]

To get ready for the second and third meeting, Druidsphere took six pictures, two of them pictures of his tablet. Several times over the three meetings, the tablet gave Druidsphere opportunities to show how bright he was. Whereas most of the other questions were answered with one word, he spent three sentences explaining how he managed to connect to the Wi-Fi:

Researcher: Are you allowed to use the internet as much as you like?

Druidsphere: It's not my carer's internet; actually, it's Wi-Fi.

Researcher: So you caught the neighbors' Wi-Fi?

Druidsphere: No, I have exchanged access codes.

Researcher: You have exchanged codes?

Druidsphere: Yeah.

Researcher: Come on, tell me!

Druidsphere: I took a SFR2) code from a website I found, then I went on Facebook, on a page where they were exchanging codes. I published some stuff saying that I was exchanging an SFR against a Free. Then someone answered and I exchanged. [53]

The tablet is also a symbol of how Druidsphere managed to keep control over his life when adults tried to stop him. He spends a lot of time on it, including at night, which was a concern for his caregiver and for his éducateur spécialisé [case worker]:

Researcher: Did they never forbid you having a tablet?

Druidsphere: It happened once. Mr. xxx didn't want me to.

Researcher: He didn't want you to?

Druidsphere: No

Researcher: Did he tell you why?

Druidsphere: Because I was spending too much time on it.

Researcher: So what did you tell them? How did you get them to give it to you in spite of this?

Druidsphere: I sat down on the stairs.

Researcher: You just stayed on the stairs?

Druidsphere: Yeah. (...)

Researcher: So what did you do? Were you angry?

Druidsphere: No, I waited (...)

Researcher: How long?

Druidsphere: Dunno. I stayed for a long time though.

Researcher: In the end, did they give it back to you?

Druidsphere: They made a contract, after that they gave it to me. [54]

The examples quoted here, as many other parts of his interviews, show that the tablet is where Druidsphere has control over things; he knows the rules, is a good player, was able to get access to the Wi-Fi, nobody can keep him from chatting with his mother, and he even managed to keep his tablet against the will of his social worker. Video games and the training corps are spaces where Druidsphere and Lucy felt they were recognized and in control of things. Through the repeated meetings over a short time, and with the help of social maps and digital cameras, Lucy and Druidsphere, like many other of the young people we met, gave us insights into areas where they felt powerful, and able to resist decisions that disempower them. [55]

4. Conclusion: A Cross-National Approach to Power Relationships

A high proportion of young people who live in public care face more difficulties than the average citizen when they have to leave care and start living independently. If we are to improve this situation, it is necessary to understand not only what happens after they turn 18, but also their everyday experience while in care. Researchers in different European countries have called for further research into the everyday life of young people in care, in a way that gathers their own perspective on their life (WOLF, 2018). [56]

The qualitative, picture-based approach we have used in this research aimed at gathering the everyday experience of young people through their own eyes. This allowed us to find out what seemed important to them, rather than imposing our own topics for discussion. The "shortitudinal" approach consisted of interviewing young people two or three times over a period of three months. This helped to create a rapport and also gave the respondents the time to decide what they wanted to talk about. This allows the researcher to see how young people identify their own strengths, instead of stigmatizing them. [57]

In the first part of the article, we put together results from previous research internationally, which show that in many European countries young people in public care still seem to share similar feelings of not being listened to. However, in our study, young people in France and England described different ways of how they had power over their lives. Handing out cameras to participants and look at the pictures they chose to show us a few weeks later was a way of listening to individual young people's own encounters of their lives, highlighting their own vision of themselves rather than imposing images of vulnerability on them. This method drove us to capture dysfunctions in the different systems, and what consequences this has on young people's feeling of power. Rather than comparing the French and English care systems, these elements suggest that systems could be further explored in the light of power relationships. Thus, the cross-national qualitative shortitudinal approach raises the power issue as an overlapping feature of growing up in care. It links the everyday experience of young people with the feeling of identity and power—or powerlessness—over their lives, and identifies opportunities for change. [58]

The ELTA project (Everyday Lives: (Re)Conceptualising Transitions to Adulthood for Young People in Care), which this article is driven from, was funded under the FP7-Marie Curie Intra-European Fellowships actions.

1) The quotes from the interviews taken in French have been translated by us. <back>

2) SFR and Free are internet providers. <back>

Becker, Johannes (2019). Orte und Verortungen als raumsoziologische Perspektive zur Analyse von Lebensgeschichten. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 20(1), Art. 12, http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-20.1.3029 [Accessed: February 28, 2019].

Boddy, Janet; Bakketeig, Elisiv & Østergaard, Jeanette (2019) Navigating precarious times? The experience of young adults who have been in care in Norway, Denmark and England. Journal of Youth Studies, http://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2019.1599102 [Accessed: November 18, 2019].

Brannen, Julia & Nilsen Ann (2011). Comparative biographies in case-based cross-national research: Methodological considerations. Sociology, 45, 603-618.

Butler, Judith (2016). Rethinking vulnerability and resistance. In Judith Butler, Zeynep Gambetti & Leticia Sabsay (Eds.), Vulnerability in resistance (pp.12-27). Durham: Duke University Press.

Crivello, Gina; Morrow, Virginia & Wilson, Emma (2013). Young Lives longitudinal qualitative research. A guide for researchers. Technical note, Young Lives project, Oxford, UK, https://www.younglives.org.uk/sites/www.younglives.org.uk/files/TN26-qualitative-guide-for-researchers.pdf [Accessed: November 25, 2019].

Ecker, John (2017). A reflexive inquiry on the effect of place on research interviews conducted with homeless and vulnerably housed individuals. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 18(1), Art. 5, http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-18.1.2706 [Accessed: February 28, 2019].

Emond, Ruth (2005). Ethnographic research methods with children and young people. In Sheila Greene & Diane Hogan (Eds.), Researching Children's experience (pp.123-139). London: Sage.

Fine, Michelle (2016). Participatory designs for critical literacies from under the covers. Literacy Research: Theory, Method, and Practice, 65, 47-68.

Foucault, Michel (1982). The subject and power. Critical Inquiry, 8(4), 777-795.

Frechon, Isabelle & Robette, Nicolas (2013). Les trajectoires de prise en charge par l'Aide sociale à l'enfance de jeunes ayant vécu un placement [Trajectories of children taken into care by Aide sociale à l'enfance]. Revue Française des Affaires Sociales, 1, 122-143, http://www.cairn.info/revue-francaise-des-affaires-sociales-2013-1-page-122.htm [Accessed: October 4, 2019]

Hedin, Lena; Höjer, Ingrid & Brunnberg, Elinor (2012). Jokes and routines make everyday life a good life—on "doing family" for young people in foster care in Sweden. European Journal of Social Work, 15(5), 613-628.

Henderson, Sheila; Holland, Janet; McGrellis, Sheena; Shapre, Sue & Thomson, Rachel (2007). Inventing adulthoods. A biographical approach to youth transitions. London: Sage.

Hillman, Alex; Holland, Sally; Renold, Emma & Ross, Nicola (2008). Negotiating me, myself and I: Creating a participatory research environment for exploring the everyday lives of children and young people "in care". Qualitative Researcher, 7, 4-6.

Holland, Sally; Renold, Emma; Ross, Nicola & Hillman, Alex (2008). The everyday lives of children in care: Using a sociological perspective to inform social work practice. Working Paper, Qualiti/WPS/005, 3-26, eprints.ncrm.ac.uk/466/ [Accessed: November 29, 2018].

Jackson, Sonia & Cameron, Claire (2011). Young people from a public care background: pathways to further and higher education in five European countries. Final report, YiPPEE projectWP12, https://bettercarenetwork.org/library/strengthening-family-care/education-programmes/yippee-project-young-people-from-a-public-care-background-pathways-to-further-and-higher-education [Accessed: November 29, 2018].

Join-Lambert, Hélène (2006). Autonomie et participation d'adolescents placés en foyer (France, Allemagne, Russie) [Autonomy and participation in decisions by adolescents placed in care (France, Germany, Russia)]. Sociétés et Jeunesses en Difficulté, 2, https://journals.openedition.org/sejed/188 [Accessed: October 21, 2018]

Join-Lambert, Hélène (2017). Enquête et images: recueillir le point de vue d'adolescent-e-s vivant en situation de placement [Inquiry and images: Exploring young people's perspectives when living in out-of-home care]. Sociétés et Jeunesses en Difficulté, 18, https://journals.openedition.org/sejed/8341 [Accessed: September 23, 2019].

Kolb, Bettina (2008). Involving, sharing, analysing—potential of the participatory photo interview. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 9(3), Art. 12, http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-9.3.1155 [Accessed: February 28, 2019].

Leeson, Caroline (2007). My life in care: Experiences of non-participation in decision-making processes. Child and Family Social Work, 12, 268-277.

McCarry, Melanie (2012). Who benefits? A critical reflection of children and young people's participation in sensitive research. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 15(1), 55-68.

McLeod, Alison (2007). Whose agenda? Issues of power and relationship when listening to looked-after young people. Child and Family Social Work, 12, 278- 286.

Morrow, Virginia (2017). A guide to Young Lives research. Methodological guide, Young Lives project, Oxford, UK, https://www.younglives.org.uk/sites/www.younglives.org.uk/files/GuidetoYLResearch_0.pdf [Accessed: September 24, 2019].

Ossipow, Laurence; Aeby, Gaelle & Berthod, Marc-Antoine (2013). Trugbilder des Erwachsenenlebens. In Edith Maud Piller & Stefan Schnurr (Eds.), Kinder- und Jugendhilfe in der Schweiz. Forschung und Diskurse (pp.101-128). Wiesbaden: Springer.

Ossipow, Laurence; Berthod, Marc-Antoine & Aeby, Gaelle (2014). Les miroirs de l'adolescence [Mirrors of adolescence]. Lausanne: Antipodes.

Phoenix, Ann; Boddy, Janet; Walker, Catherine & Vennam, Uma (2017). Environment in the lives of children and families: Perspectives from India and the UK. Bristol: Policy Press.

Potin, Emilie (2012). Enfants placés, déplacés, replacés: parcours en protection de l'enfance [Children placed, moved, placed back: Pathways in child protection]. Toulouse: Eres.

Powell, Mary Ann & Smith, Anne B. (2006). Ethical guidelines for research with children: A review of current research ethics documentation in New Zealand. Kōtuitui: New Zealand Journal of Social Sciences Online, 1, 125-138.

Rauschenbach, Thomas & Bien, Walter (2012). Aufwachsen in Deutschland. AID:A—Der neue DJI-Survey. Weinheim: Beltz Juventa.

Riessman, Catherine Kohler (2000). Stigma and everyday resistance practices. Childless women in South India. Gender and Society, 14(1), 111-135.

Robin, Pierrine (2013). L'évaluation de la maltraitance, Comment prendre en compte la perspective de l'enfant? [Assessing child maltreatment. How to include the perspective of the child?]. Rennes: Presses Universitaires de Rennes.

Robin, Pierrine; Mackiewicz, Marie-Pierre & Ackermann, Timo (2017). Des adolescents et jeunes allemands et français confiés à la protection de l'enfance font des recherches sur leur monde [German and French teenagers and youngsters in care research their world]. Sociétés et Jeunesses en Difficulté, 18, journals.openedition.org/sejed/8385 [Accessed: October 21, 2018].

Ross, Nicola; Renold, Emma; Holland, Sally & Hillman, Alex (2009). Moving stories: Using mobile methods to explore the everyday lives of young people in public care. Qualitative Research, 9, 605-623.

Schaffner, Dorothee & Rein, Angela (2013). Jugendliche aus einem Sonderschulheim auf dem Weg in die Selbständigkeit – Übergänge und Verläufe. Anregungen für die Heimpraxis aus der Perspektive von AdressatInnen. In Edith Maud Piller & Stefan Schnurr (Eds.), Kinder- und Jugendhilfe in der Schweiz. Forschung und Diskurse (pp.53-78). Wiesbaden: Springer.

Spyrou, Spyros (2019). An ontological turn for childhood studies?. Children & Society, 33(4), 316-323.

Steedman, Carolyn (2000). Enforced narratives. Stories of another self. In Tess Coslett, Celia Lury, & Penny Summerfield (Eds.), Feminism and autobiography: Texts, theories, methods (pp.25-39). London: Routledge.

Stein, Mike (2012). Young people leaving care. Supporting pathways to adulthood. London: Jessica Kingsley.

Stein, Mike & Munro, Emily (Eds.) (2008). Young people's transitions from care to adulthood. International research and practice. London: Jessica Kingsley.

Stein, Mike & Verweijen-Slamnescu, Raluca (2012). When care ends, Lessons from peer research. Insights from young people on leaving care in Albania, the Czech Republic, Finland, and Poland. Research report, SOS Children's Villages International, Innsbruck, Austria, https://www.sos-childrensvillages.org/news/eu-told-how-care-leavers-as-young-as-14are-abandon [Accessed: October 4, 2019].

Thiersch, Hans (2005). Lebensweltorientierte soziale Arbeit. Weinheim: Juventa.

Thomson, Rachel (2003). When will I see you again? Strategies for interviewing over time. Seminar "Reflexive Methodologies: Interviewing Revisited", October 30-31, 2003, Helsinki Collegium for Advanced Studies, Finland, http://www.restore.ac.uk/inventingadulthoods/downloads/when_will_I_see_you.pdf [Accessed: October 21, 2018].

Thomson, Rachel (2007). The qualitative longitudinal case history: Practical, methodological and ethical reflections. Social Policy & Society, 6(4), 571-582.

Thomson, Rachel & Holland, Janet (2005). Thanks for the memory: Memory books as a methodological resource in biographical research. Qualitative Research, 5(2), 201-291.

Van der Vaart, Gwenda; Hoven, Bettina van & Huigen, Paulus P.P. (2018). Creative and arts based research methods in academic research. Lessons from a participatory research project in the Netherlands. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 19(2), Art. 19, http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-19.2.2961 [Accessed: February 28, 2019].

Wilson, Sarah & Milne Elisabeth (2013). Young people creating belonging: Spaces, sounds and sights. Research briefing, University of Stirling, UK, https://dspace.stir.ac.uk/bitstream/1893/12942/1/SightsandSoundsfinalreportweb.pdf [Accessed: November 29, 2018].

Wolf, Klaus (1999). Machtprozesse in der Heimerziehung. Eine qualitative Studie über ein Setting klassischer Heimererziehung. Münster: Votum.

Wolf, Klaus (2018). Interdependency models to understand breakdown processes in family foster care: A contribution to social pedagogical research. International Journal of Child and Family Welfare, 18(1/2), 96-119.

Woodgate, Roberta L.; Zurba, Melanie & Tennent, Pauline (2017). Worth a Thousand words? Advantages, challenges and opportunities in working with photovoice as a qualitative research method with youth and their families. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 18(1), Art. 2, http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-18.1.2659 [Accessed: February 28, 2019].

Zamaldinova, Gania (2010). Interaction between state and public bodies providing social and educational support to social orphans. Izvestia: Herzen University Journal of Humanities and Sciences, 121, 97-100.

Hélène JOIN-LAMBERT is maître de conference in education at the University Paris Nanterre (France). She holds a PhD in sociology and a habilitation in education. Her research focusses on family welfare and child protection systems, more specifically on tensions between perspectives of young people in care, their parents and their carers. Cross national perspective is a major aspect of her work.

Contact:

Hélène Join-Lambert

Centre de Recherches en Education et Formation

UFR SPSE

Université Paris Nanterre

200 avenue de la République, 92000 Nanterre, France

E-mail: helene.join-lambert@parisnanterre.fr

URL: https://www.parisnanterre.fr/mme-helene-join-lambert--697494.kjsp

Janet BODDY is a professor of child, youth and family studies and was until recently the director of the Centre for Innovation and Research in Childhood and Youth (CIRCY) at the University of Sussex. Her research is concerned with family lives and with services for children and families, in the UK and internationally.

Contact:

Janet Boddy

Centre for Innovation and Research in Childhood and Youth

Essex House

University of Sussex

Falmer, Brighton

BN1 9QQ, UK

E-mail: J.M.Boddy@sussex.ac.uk

URL: http://www.sussex.ac.uk/profiles/287143

Rachel THOMSON is professor of childhood and youth studies, her research interests include the study of the life course and transitions, as well as the interdisciplinary fields of gender and sexuality studies. She is a methodological innovator and is especially interested in capturing lived experience, social processes and the interplay of biographical and historical time.

Contact:

Rachel Thomson

Centre for Innovation and Research in Childhood and Youth

Essex House

University of Sussex

Falmer, Brighton

BN1 9QQ, UK

E-mail: R.Thomson@sussex.ac.uk

URL: http://www.sussex.ac.uk/profiles/285568

Join-Lambert, Hélène; Boddy, Janet & Thomson, Rachel (2020). The Experience of Power Relationships for Young People in Care. Developing an Ethical, Shortitudinal and Cross-National Approach to Researching Everyday Life [58 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 21(1), Art. 5, http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-21.1.3212.