Volume 21, No. 2, Art. 4 – May 2020

Image Clusters. A Hermeneutical Perspective on Changes to a Social Function of Photography

Michael R. Müller

Abstract: Photography can be used for a wide variety of social functions. The hermeneutic method of image cluster analysis presented deals with a comparatively new social use and understanding of photography: as digital montage forming intricate compilations. At the methodological heart of this approach is the 1. figurative analysis of the compositional principles of particular image compilations, i.e., their expressive meaning. This ideographic perspective is expanded and supplemented by 2. investigating the structure of the mediated field of perception and action of each image cluster, as well as the styles of observing and knowing that they predicate. Methodologically speaking, the approach relies on an assumption that far from being an invention of technological media, the "game" (WITTGENSTEIN) which is constitutive of iconic image clusters, complete with relationships of similarity and difference, has its anthropological basis and primary social expression in people's body language and in minor social distinctions. According to this hypothesis, in recent image clusters photography is no longer necessarily understood as depicting or documenting occurrences in the lifeworld, but is instead consolidated as a collectively shared means of expression which can be repeatedly recombined to form new figures of expression—in other words, it achieves a decidedly idiomatic quality.

Key words: image analysis; image clusters; figurative hermeneutics; sociology of knowledge; visual sociology; visual studies; visual communication; digital photography

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. A Methodological Approach to the Problem

3. Structural Characteristics and Methods

3.1 Principles for composition and montage

3.2 Frames for reception

4. Towards a Social Theory of Images

4.1 The types and principles of image compilation

4.2 A brief digression on iconicity

4.3 Iconic means of the social display

1. Introduction1)

The title says it all: this essay deals with changes to a social function of photography (BOURDIEU, 1990 [1965]). Rather than being about photography or the photographic genre in itself, it analyses from a social-science perspective how photographs in everyday society and over the course of time have, now and again, been used and understood in very different ways. In the early 1980s, Roland BARTHES believed that the essence of photography was its optical and technical relationship to the event and the object (its that-has-been) (1981 [1980], p.76). A sociology of photography which seeks to comprehend the more recent, contemporary expressions of photographic activity, however, would have to consider that photographs in the lifeworld are used in various mediated forms and social constellations (as paper prints, as digital series of images, as uniquely relevant forms of expression, as "anonymous photographs" (KELLER, 2016, p.118)2), or as real-time social media) and are consequently understood and evaluated very differently in terms of their expressive meaning and value (STIEGLER, 2009). One of these potential uses and ways of understanding photography is the digital image cluster—in other words, compiling numerous photographs to create a new visual whole—and its presentation amidst changing media routines and symbolic relationships of social exchange. The theoretical commentary and case studies below are concerned with analyzing a hermeneutical approach to these digital image clusters. [1]

Discussing the question "What is an image?" in the first section, in the second section of this article I explore basic structural features of iconic image clusters as well as possible methods of image cluster analysis. In the third and final section I conclude with some general theoretical remarks both on the genesis of representational pictorial forms in communicative action in general (MÜLLER, 2019) and on iconic image clusters as a changed social use of photography in particular. [2]

2. A Methodological Approach to the Problem

My understanding of an "image cluster" (MÜLLER, 2012, p.156) in what follows is that images are compiled to form a greater whole, however this may be achieved: it is literally a pile of photos. Widely known manifestations of photographic image clusters are ancestral galleries, photo albums, exhibitions, but also fashion or advertising features in magazines. Digital variants take the form of blogs, streams, or albums on assorted Web 2.0 platforms. The term cluster has been carefully chosen with reference to picture compilations and presentations of this kind, because even in its original meaning—group, collection, bundle, mass or clump—it denotes a distinct structural characteristic which on the one hand makes analyzing these image compilations more complex than the classical analysis of individual images, yet on the other is also constitutive of the appearance of these particular symbolic forms; this might be ideological and discursive, or seeking to promote relationships, or solemn and impassioned. [3]

The difficulties of analyzing image clusters from a social science perspective soon become clear, namely in determining the pictorial quality we are dealing with, and which analytical principles and methods are consequently methodologically appropriate. Are we concerned in each case (see Plate II.1) with a whole image or with (very) many individual images? Or is it a multitude of images which is more as a whole than the sum of its parts, which in turn is an image (or a kind of image)? And what results from this in analytical terms? Should we begin with the iconic unit which represents the whole, or with the images which we would like to identify individually? How could one be related to the other? [4]

These questions and methodological uncertainties might only be clarified when we bear in mind that the traditional understanding of an image (a panel painting, a painting, a photographic print) reflects an extremely special and narrowly defined concept of an image. In discussing prehistoric finds and non-European art history, Gottfried BOEHM, for example, states that "our—often unspoken—prejudice to evaluate the picture in comparison to a painting or panel painting, leads us to a dead end" (1995, pp.37f.). Not only panel paintings, paintings and photographs have a pictorial quality, but also writing, architecture, functional objects, and last but not least, the human body modulated by cultural techniques such as decoration, painting, and clothes (BELTING, 2011; EMMISON, SMITH & MAYALL, 2012). Moreover, if we follow Michael TOMASELLO's investigations into the "Origins of Human Communication" (2008), we can state that the primary medium used by people to produce images is representational gesticulation (the "iconic gesture"): the direct physical simulation of, for example, absent objects, opaque links, or actions which have not yet been carried out (see Fig. 1).

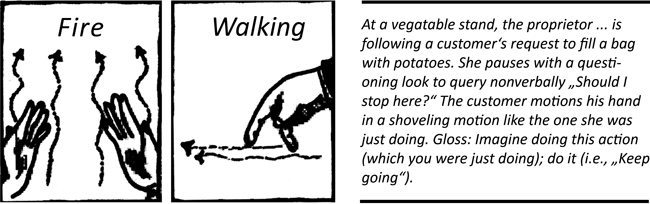

Figure 1: Iconic gestures: an own pictographic representation on the left and a narrative representation on the right (TOMASELLO,

2008, p.68) [5]

When undertaking a thorough comparison of assorted iconic manifestations, it becomes clear that quite a few of these characteristics, which could certainly be consistent with the concept of images in the narrow definition given above (panel paintings, paintings, photography), are in no way analytically generalizable. This applies in particular to:

the assumption of what is in principle a two-dimensional state and finite nature of expressive and representational pictorial forms (i.e., it must be possible to project the idea of what an image is or what comprises visual quality onto a easily visible plane without loss),

the assumption of illustratability: that it is possible to illustrate expressive and representational pictorial forms (i.e., the assumption that images, especially photographs, are characterized by being particularly concrete or faithful to nature), and

the assumption of the communicative self-sufficiency of expressive and representational pictorial forms (the notion, dismissed as "hermeneutism" by BOURDIEU [1996 [1992], p.314], that images surround their meaning like a container surrounds its contents). [6]

On Point 1, i.e., the assumption of what is in principle a two-dimensional state and static finite nature of expressive and representational pictorial forms, we can say that this assumption is not only largely appropriate for an analytical approach to panel paintings, paintings or photographs, but also extremely analytically productive (as shown by Max IMDAHL's planimetric analyses [1995], for example). Nonetheless, the diversity of media forms and iconic manifestations—a diversity which incorporates the human body gesticulating in space as much as it does the dynamic scrolling of projected digital displays—only partially reflects this assumption. Two-dimensional depictions with static external boundaries are of course also generated by scrolling social media, the back covers of magazines, ritual altarpieces (closed and opened), masks, vases, tattooed bodies, and gestures. Yet when using complex, multidimensional visual media for communication, the occasional constitutive contrast between front and back, between hidden and shown, between currently visible and still invisible (KEMP, 1998), between significant gesture and physical background (BOEHM, 2007), or between graphé3) and material visual object (MÜLLER, 2011) is not captured by looking at them from a purely planimetric perspective or as a planimetrically arranged print in an illustrated book or screenshot. Essentially, the "Materialit[y] of Communication" (GUMBRECHT, 1994) (and that potentially includes its digital state) opens up more dimensions for interpretation and more opportunities for expression with respect to the social use of images and the emergence of new iconic forms than at a merely planimetric level. [7]

Point 2 addresses the intuitive assumption of illustratability: that it is possible to illustrate (in a manner which is particularly concrete or faithful to nature) expressive and representational pictorial forms: This assumption is not only puzzled by the abstract, non-objective painting of classic modernism (GEHLEN, 1965). Moreover, with respect to genres over the course of history, the genesis of expressive and representational pictorial forms starts with the social production of what are more or less abstract graphics. The paleoanthropologist André LEROI-GOURHAN, for example, points to "tight curves or series of line engraved in bone or stone, small equidistant incisions that provide evidence of figurative representation moving away from the concretely figurative and proof of the earliest rhythmic manifestations" of "spirals, straight line, and clusters of dots [...] representing the body of the mystic ancestor or the places where the myth unfolds" (1993 [1964], p.188). The idea of an image as a depiction or even a "double of reality" (BOEHM, 1995, p.37) certainly excludes a multiplicity of other historical and socially functional iconic forms: for example, pictographs (i.e., standardizing depictions, which determine formal similarities by means of deliberate abstractions), logographs (i.e., more or less arbitrarily depicted morphemes, and ideographs (i.e., graphic depictions of complex events, relationships or other notions of order (LEROI-GOURHAN, 1993 [1964], pp.187-216, 358-408). [8]

Precisely in the case of photography, the assumption of illustratability has proved to be too narrowly defined. It is important to state that the meaning of (even) photography as social communication is by no means limited to the characteristic of what Charles Sanders PEIRCE described (and Roland BARTHES later emphasized) as indexicality, namely that photographs are "in certain respects exactly like the objects they represent" (PEIRCE, 1965, 2.159). Photography, moreover, achieves its added value as social communication through its manifold potential for being combined with other photographs—thus not (only) through the fact that it depicts something, but rather that it generates correlations for the depicted object which transcend the quality of the depiction, in other words they are symbolic. [9]

A striking example of this (and at the same time also a precursor of the recent Web 2.0 image clusters) is the consciously serial function of photography which formed the basis for Edward STEICHEN's 1951 photographic exhibition "The Family of Men" (see Plate I for an example). The formal similarities exhibited by the images shown adjacent to each other (in Plate I these are rigorous work, synchronized bodies, and same-sex protagonists) lend these image compilations a symbolic quality, which pushes the significance of the subjects' living conditions and circumstances into the background. What makes the photographs in the "Family of Men" exhibition into pictures which, according to the curators, had the rather grand aim of presenting mankind as a family, is not the indexicality of the individual photographs but the fact that their juxtaposition reveals what is supposedly archetypically human. This example shows that in term of its social functions, even photography would only be partially described by the characteristic of illustratability.

Plate I: Excerpt from the exhibition "The Family of Men" (1951). Above the pictures in this section was written: "If I did not work,

these worlds would perish ..." (THE MUSEUM OF MODEN ART, 1983, pp.76-77) [10]

Point 3 assumes the self-sufficiency of representational pictorial forms: that pictures surround their meaning, as it were, like a container surrounds its contents. This notion is connected, among other things, with modern ideas about art and our experience of art in museums. We are used to immersing ourselves interpretively in a PICASSO or in a photograph by Man RAY (BOURDIEU, 1984 [1979]; 1996 [1992]; GEHLEN, 1965). However, becoming engrossed in pictorial representations in situ presupposes that we are indeed lingering in front of them, or that they induce us to linger in front of them. In this—pragmatic—respect, George Herbert MEAD's view on gestures (another everyday iconic form) applies even to pictorial representations of autonomous art: their meaning is always derived, inter alia, from the reactions they provoke in the recipient; in other words, the fact that they catch our attention and persuade us to linger, that they "trigger the verbal process" (LEROI-GOURHAN, 1993 [1964], p.195) or an action on our part. This is significant in sociological terms too, for one characteristic of recent digital image technologies is precisely that they provide numerous opportunities for predicating observational actions of recipients. As a dynamic sequence of changing views, for instance, a blog necessarily presupposes that its recipients physically intervene in the media's visual space and scrolling process. Consequently, the recipients make adjustments to the object of their perception through their body movements and their "cognitive style" (SCHÜTZ, 1945, p.230). Wolfgang KEMP's (1992) work on art history and the media and sociological analyses conducted by Hans-Georg SOEFFNER (2014) and Horst WENZEL (2009) reveal that pictures are more than just self-sufficient carriers of the "symbolical values" and "content(s)" described in the history of ideas (PANOFSKY, 1972 [1939], p.14). Seen from the perspective of the sociology of knowledge, they are also always symbolic media-based organizational forms, each with a specific position and attitude to the viewer; they are situational to "what one individual can be alive to at a particular moment" and in a particular way (GOFFMAN, 1986 [1974], p.8), and they play a significant role in the social organization of his/her experiences of the world (and him-/herself). [11]

By comparing icons with respect to their socio-historical characteristics and aspects relevant for social communication, we can see that a "style of thinking" (FLECK, 1979 [1935], passim) focusing on the planimetry of the individual image, which is interested in pictorial veracity or purely ideographic in its aim, would ultimately only capture certain qualities of perception and meaning from among an indefinite number. Depending on the type of communication, these qualities could play a role in the way we use iconic forms of expression and depiction. This kind of thinking style would by no means be wrong, but the perspective it gives us occasionally proves to be too narrowly defined for an analysis. The consequence for image cluster analysis, particularly in the social sciences, is that valid results can only be produced by repeatedly ascertaining the nature of what is being investigated and hence the suitability of potential methods.4) [12]

3. Structural Characteristics and Methods

Two structural characteristics of recent image clusters—their ephemeral external boundaries and their dependency on the observational actions of their recipients—frequently turn out to be challenging when conducting empirical analysis. Explicating these structural characteristics (which are both discussed below), however, does not require each individual case to be either valid or complete.5) In the first instance, the function and aim of the process is simply explorative in nature: namely identifying two increasingly important everyday "standards and routines" (SOEFFNER, 2004, p.70) for communicating through image clusters, and trying out suitable analytic approaches. [13]

3.1 Principles for composition and montage

An initial ideal-type structural characteristic of digital (and possibly analogue) image clusters is that they feature ephemeral external boundaries by comparison with panel paintings, paintings or photographic prints. That means it is sometimes not possible to specify with planimetric precision where and how a cluster ends, for instance via various technical options for scrolling, via alternative available modes of representation (image tableaux, photo streams, album formats), or generally via the relationships between what is currently visible and not visible. Indeed, one of the specific features of these complexly organized visual artifacts is the fact that although they comprise far more material than our sight can take in at a particular moment, this surplus is meaningful for the communicative unity of a cluster. Whether scrolling through a blog or strolling through an exhibition (to give two very different examples), perception is not merely receptive but also productively active to at least the same degree, connecting current visual experiences with previous experiences, and the corresponding expectations with communicative units of meaning. Rather than being defined by the external boundaries of a picture's self-contained surface area, these units of meaning are determined by the composition and montage of a series of visual objects, or by modifying such objects. [14]

Through analysis, we can accordingly identify (and reconstruct) the principles of composition and montage which form the basis of selecting images for a cluster. These are the principles which the producers of an image cluster follow—not necessarily consciously, but probably with a structural goal in mind—when selecting and applying the appropriate images to form a compilation. Digital image clusters in particular are generally produced and reproduced by an unending stream of new individual images (which are "posted," "reblogged" or "shared"). Thus, as far as their meaningful and communicative coherence is concerned, they have to be materially "almost limitlessly) open" but structurally "(relatively) closed" (SOEFFNER, 2010, p.88). This how of their internal composition and montage can be socially and creatively negotiated and controlled as the typical style of a particular cluster. If we make the hermeneutic assumption that a valid analysis of everyday social communication has to be aware of and thus systematically account for the standards and routines underpinning this social communication (see above), then we must produce an image cluster analysis in this first dimension as an analysis of the how of the composition and montage of individual images, or of the "figurative principle" (MÜLLER, 2009, p.61) of its composition. [15]

From a logical research perspective, a figurative analysis has to essentially answer two questions: 1. What topics, objects and designs comprise the visual material from which a cluster is made? 2. What principles are adhered to when composing and representing the particular topics, objects and designs within a cluster? Thus, we are concerned on the one hand with reconstructing striking types of images, and on the other hand with the style-forming figures of their compilation. [16]

From a practical research perspective, a figurative analysis as the search for formal, representational or thematic visual variations and groups of variations is completed through "easy arranging and rearranging" (GOFFMAN, 1979, p.25) of the individual images. The "easy arranging and rearranging" metaphorically described by GOFFMAN refers to the continued, systematic comparison of the individual visual representations within a cluster—a technique of differentiating between and contrasting formal, representational and thematic aspects which ultimately results in categorically identifying various types of images. [17]

A figurative analysis of the blog presented in Plate II.1 can serve here as an example6). A comprehensive comparison7) of the individual visual representations swiftly allows us to categorically identify the various types of images (Plate II.2), because when the images are placed side by side, representational or thematic aspects become apparent and we can see that each group of individual representations is similar in one specific aspect.

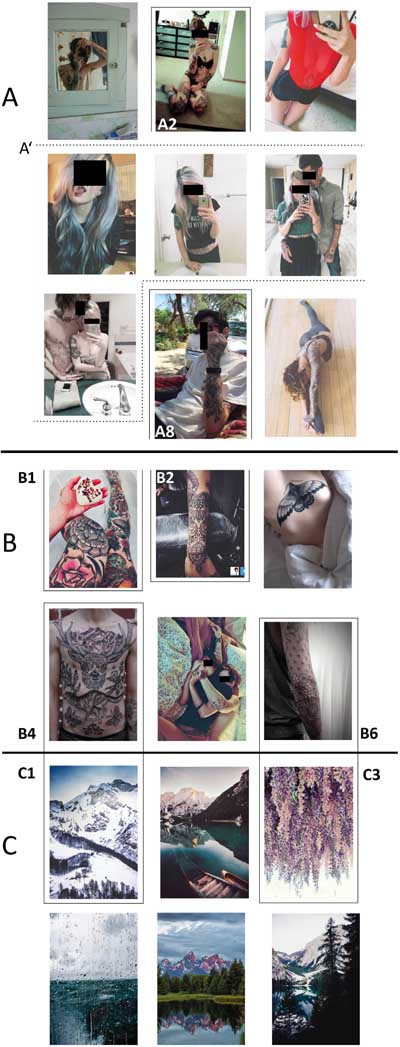

Plate II.1: Screenshots from the blog of a neo-punk follower [Accessed: June 18, 2015; URL deactivated]. Please click here for an enlarged version of Plate II.1.

Plate II.2: Categorical identification and axial connection of various image types. The representation documents the reconstruction

of formal, object-based, or thematic visual variations and groups of variations. The three most noticeable categories are

presented here: A, A', B and C. Framing B4/C1, B6/C3, A8/B2 and B1/A2 in twos reflects several of the axial connections based

on significant similarity relations.

Category A comprises portraits of people who are tattooed and/or have piercings. The sub-category A' includes pictures where the same person can additionally be seen again and again (the author and owner of the blog).

Category B comprises pictures of tattooed arms, legs and upper torsos; they are depictions of tattoos rather than portraits in the traditional sense of head-and-shoulders or three-quarter-length views.

Category C comprises landscape or nature images, which in formal terms are characterized by a specific coloring (this becomes recognizable through the compilation of images itself) and a relatively high proportion of ornamental or geometric structures. [18]

A linguistic description and consolidation of these categories is ultimately unavoidable in the research process, not just because of the necessarily discursive nature of scholarly argumentation, but also due to the fact that each reflective viewpoint—perhaps with the exception of the phenomenological epoché, which takes the opposite route—transcends its meaningful date in the direction of structured experiences.8) Nonetheless, the modus operandi for categorically identifying different types of images is to contemplate the image, for it is only when the images are viewed side by side that we can notice the aspects shared by individual representations within a cluster. Ludwig WITTGENSTEIN would describe this process of contemplating a picture to gain knowledge about it as follows: "I contemplate a face and then suddenly notice its likeness to another. I see that it has not changed; and yet I see it differently. I call this experience 'noticing an aspect'" (1958 [1953], p.193; KRÄMER, 2001). [19]

Comparatively contemplating the images is, however, not merely relevant for identifying various types of images, but also with respect to their connections to each other, i.e., in reconstructing the principle which determines their style of their composition and montage. Thus, as the comparison of images in the cluster Plate II.1/II.2 continues, similarities between the different types of images also become apparent at certain points and in recurrent aspects.9) We repeatedly find 1. formal and aesthetic similarities between images of nature from Category C and tattoo images from Category B as well as 2. thematically speaking, similarities concerning the subject between the tattoo photographs from Category B and the portraits from Category A. [20]

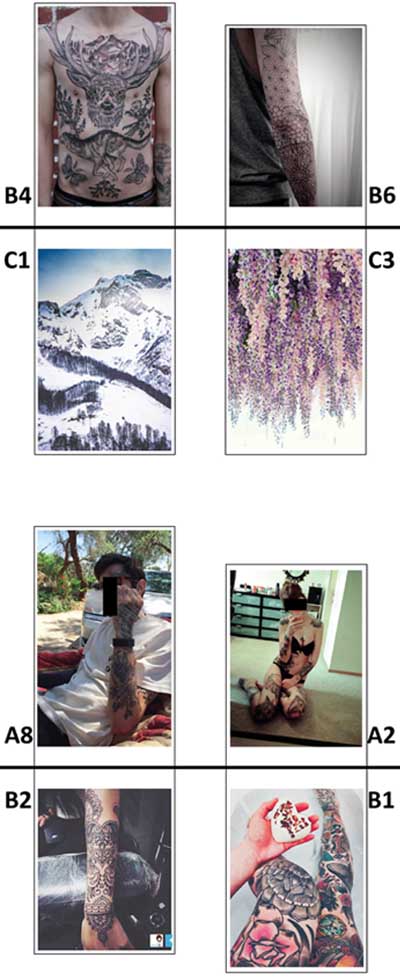

On 1: The illustrations B.6 and C.3 (Plate II.3), for example (the first a photo of a tattoo, the second a nature photo), display similarities in the sense of pronounced ornamental structures and reddish-violet coloring, and these are apparent despite their categorical differences. Similar is true of the images B.4 and C.1 (Plate II.3): in this case the homologous aspects are the mountain motif (the mountain ridge of the landscape scene could almost have been copied by the tattoo) and the wood-like structure of the light and dark contrasts.

Plate II.3: Axial connection of various image types. Excerpts from Plate II.2 [21]

Similarities of this kind are communicatively and analytically remarkable in as far as they meaningfully structure the diverse types of visual materials: however many and varied lifeworld meanings the tattoos such as those photographed (Category B) might have, the fact that they are depicted directly adjacent to, and with an aesthetic/formal elective affinity to the images of nature and landscapes in Category C means that one of the potential uses and ways of being understood is being communicatively emphasized. In the framework of the cluster, which allows us to deduce meaning, they are not (or at least not solely/primarily) understood and employed as signs or emblems with conventionalized meanings, but rather as an aesthetic of transcendential physicality in an ornament: in other words, as an ornamental allegory. [22]

On 2: The images A.8 and B.2 (Plate II.3) were classified in the categories A (portraits) and B (photos of tattoos). Nonetheless, the fact that both images prominently display the motif of a tattooed arm is a similarity which stands out beyond the differences in their categorization. The same is true of images B.1 and A.2 (Plate II.3), which share the themes of viewing one's own body through the lens of the camera and observing the human body as the medium for a tattoo. [23]

Here too, the meanings of various types of visual material are structured through significant similarities: whatever the reasons might be for reproducing photos of tattoos online (whether economic, social, artistic, or scholarly), presenting them in an iconic elective affinity and close media contiguity to the portraits of Category A makes it evident—within the semantic structure of the cluster—that the tattoos of Category B in some cases have concrete owners who can be identified via portraits and to a greater or lesser degree located in the lifeworld. And vice versa: thanks to the attested quality of their tattoos, the subjects of the portraits can be identified as members of a style community who share a particular style. [24]

The ongoing comparison of individual images in a cluster makes it possible to systematically recognize axial connections and semantic structures such as those outlined above. It is remarkable that these connections and semantic structures can be accessed even when the contemplation is just natural and spontaneous (and not just when it becomes scholarly and analytical) in frequently changing media iterations. [25]

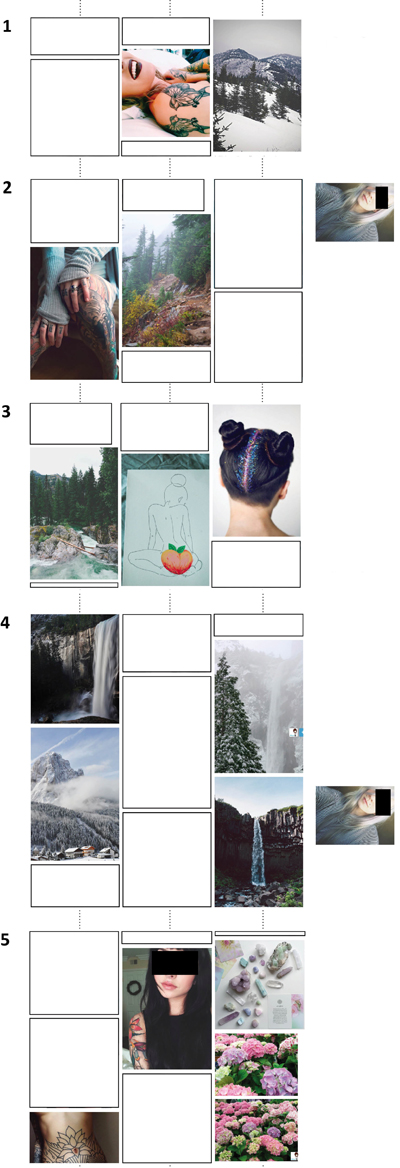

Plate II.4 exemplifies this clearly in several extracts from the original image cluster: in a series of variations, similarities between types of images evidently take center stage within a cluster. Excerpts 1 and 2, for example, once more emphasize the formal, aesthetic similarity of images showing bodies and landscapes, thereby showcasing the allegorical proximity between the tattooed body and nature. In excerpt 3 this symbolist perspective is extended to the body as a whole (hairstyle and physiognomy). In excerpts 2, 4 and 5, relevant sections of the portrait make it possible to establish relationships to specific people or to the style communities they belong to.

Plate II.4: Screenshots from the blog. Sections of the images which are beyond or on the margins of certain relevant similarity

relations have been blanked out, in order to emphasize these similarity relations. [26]

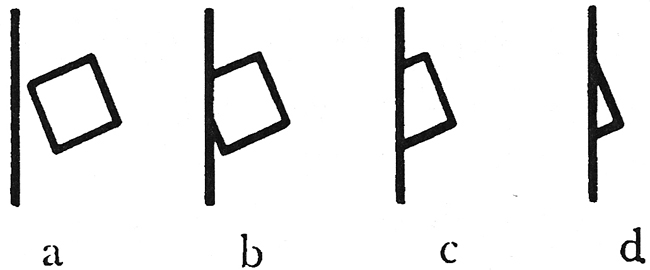

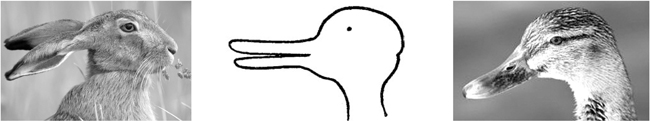

At this point, we have to imagine the communicative mechanism which is employed in these image compilations (or "hyperimages," THÜRLEMANN, 2013, p.7), and which should not be confused with the use of conventionalized signs: image clusters develop their communicative effect and meaning not by functioning like bundles of accumulated individual meanings, but rather by means of iconic similarity relations and media contiguity relations which allow these images to mutually comment on and interpret each other, as it were. Given that the perception of something, the seeing as, the apperception, is always dependent on comparing current with past experiences (BERGSON, 1991 [1896], p.164) perception can effectively be steered in certain directions via social communication—by giving explanatory pointers or presenting similar pictures (KRIPPENDORFF, 2006; SCHÜTZ & LUCKMANN, 1989). Rudolf ARNHEIM (1974 [1954]) gives a graphic example to illustrate this dependency of perception on noematic (i.e., provided from memory, suggestive language, or in the form of other pictures) objects of comparison (Figures 2.a-d): whatever the individual might think they have recognized in Fig. 2.d, such as "a triangle attached to a vertical line," as soon as we see the figure in conjunction with Figures 2.a, b and c, "it will probably be seen as a corner of a square about to disappear behind a wall." That means out of a theoretically unlimited number of potential options for perceiving and understanding the original figure, one possibility is highlighted and confirmed by clear visual similarity relations between the figures in the images. A similar point is being made with WITTGENSTEIN's "duck-rabbit" head (1958 [1953], p.194) (Fig. 3); this drawing is interpreted in different ways according to how the images are compiled, i.e., the compilation determines which of the two potential options (although strictly speaking there are an infinite number of each) for being understood and employed is actually being depicted. "The contiguous images show the beholder how a particular image should be viewed" (THÜRLEMANN, 2013, p.20; see also BAUER & ERNST, 2010; LACHMANN, 2012).

Figure 2: Graphic example (ARNHEIM, 1974 [1954], p.49)

Figure 3: WITTGENSTEIN's "rabbit-duck head" (1958, p.194; center) next to the pictures of a rabbit and a duck (my image compilation)

[27]

Whether we are dealing with such easy examples or rather with complex cluster formations like those discussed above, each compilation of images reflects a process of generating meaning—a process which counters the auratic segregation of pictures when they are hung by museums in isolation. This process is essentially based on the consciously creative structuring of options for perceiving and understanding. The question to be addressed empirically and analytically in each individual case is how we should characterize the principles and figures upon which this structuring of options for perceiving and understanding are based. [28]

Bearing this in mind (and with theoretical recourse to Max WEBER's sociology of religion), our example of the cluster in Plate II can be described in essence as a mystical and sentimental form of presenting the self. Through their dynamically arranged similarity relations, the depictions of nature, photographs of tattoos, and portraits on the blog repeatedly show how the author and owner of the blog wishes to be seen and understood: firstly, she should be viewed as the member of a distinct style community, and secondly, as an individual who—like other members of this community—thereby becomes the person s/he wants is or wants to be by designing and presenting a significant part of him-/herself—namely his/her body—as an emblematic proxy (or ornamental allegory) of a nature-loving unio mystica. When looked at from this perspective, the cluster not only possesses a style in the formal sense of having a structure for composition and assembly which is characterized by the types of images named above plus similarity relations, but in terms of content and theme it is also part of the way persons style themselves. That, however, is a specific feature of this case study. [29]

At this point I will summarize what has already been discussed: 1. the task at the heuristic heart of conducting a figurative analysis of an image cluster (such as that we have dealt with here) is to reconstruct the principles of composition and arrangement which provide the basis for continually selecting individual images and composing them to form a whole picture. Two aspects are of interest here: the semantic figure of each pictorial composition as a whole and, where applicable, the particular artistic means required to represent each semantic figure visually. From a methodological perspective, an analysis of this kind should be conducted by comparing images directly and systematically, with the aim of determining the relationships of similarity and difference which exist between the individual images in the cluster and those which, due to the particular options presented by image perception in each case, have been visually emphasized and transposed into significant semantic structures. An analytical approach of this kind should be labeled figurative (MÜLLER, 2012)10) in methodological terms: firstly because investigating an image cluster by analyzing the images assumes (with respect to the nature of what is being investigated) that both the structural sense and the meaning of a particular cluster are manifested in a succession of new material iterations, i.e., figurations (instead of generally valid conventionalized signs). Accordingly, the analytical action of continually comparing the individual images in a cluster is then implemented as a systematic acting out of structural relationships of similarity and difference, i.e., as a figurative analysis.11) [30]

2. Even if the question of how is critical to an analysis of a particular image compilation, a figurative cluster analysis focuses on the sociology of knowledge rather than on formal considerations concerning the history of style; it is about how the world, how the others, how each individual person or group is thematized and how they are interpreted by the juxtaposing of hundreds of individual images. The iconic capabilities of image compilation and its attractiveness for everyday (self-) presentation and interpretation stem from the fact that they allow aspects to be emphasized, connections to be made, and symbolic meanings to be realized which exceed the expressive potential of individual images. Bearing in mind the sheer number of empirical cluster types, we should note also that image clusters do not necessarily need (as with the cluster type discussed in the example) to display a decidedly iconic quality, i.e., one characterized by evident relationships of similarity and difference between its individual images. In terms of ideal types we can differentiate between iconic, narrative and classificatory uses for image compilations in social communication. (In Section 4 I explore this issue in more depth, that is, the above does not apply to every type of cluster, but only to iconic clusters.) [31]

3. In addition to all these peculiarities of image clusters, the general analytical principles and rules of socio-scientific hermeneutics must also be taken into account here. In particular, it is important to control the interpretative work of those who carry out interpretations. To this end, it is firstly necessary to identify one's own interpretative interest of research. Otherwise, the necessarily limited scope of the respective results cannot be marked. Secondly, the limited horizon of one's own knowledge about the pictures at hand needs to be broadened. This can be done regularly through appropriate research, for example on the iconography of the relevant images or group-specific stocks of knowledge. In addition, interpretation in research groups that are as heterogeneous as possible, i.e., composed in a multi-perspective manner, has proven to be a suitable method. [32]

If we base our analysis of digital image clusters not on photographically fixed screenshots, but rather on an observational online exploration of each cluster, the quality of perception changes considerably for the object being investigated. The static nature of the images is transformed by clicking on individual pictures and scrolling through entire compilations of images in a dynamic sequence of changing views. The digital display now shows not only visual objects, but also a theoretically remarkable reciprocity of the perceived and the perceiver; evidently the form (and hence also the socio-communicative meaning) of the iconic object is likewise generated by the observational actions of its recipients. This reciprocity of perceived and perceiver is a second structural characteristic of recent image clusters for us to analyze. [33]

The blog addressed above can once more serve as our example, but this time in its natural state, so to speak, as a digital display projection; upon opening the blog we can initially make out a depiction of something framed by the display screen. At the same time the mouse cursor and sidebar can be understood as appeals to vary or change this depiction manually. Characteristic features of digital image clusters like this are, moreover, design elements which refer the recipient to opportunities for perceiving something beyond the current field of view; thus the framing of the bottommost individual image generates not only image formats in every conceivable aspect ratio from 1:0 to 1:2, but also severs "natural subject matter" (PANOFSKY, 1972 [1939], p.14) such as things, bodies, people, or contexts in a fairly random manner. Anyone who is well acquainted with the medium will know that these framings are relatively reliable indications of other visual depictions or partial depictions which can be brought into view by making specific movements with a mouse or other device. Other symbolic references to transcendent depictions or partial depictions are image banners, which appear in individual pictures when the mouse cursor is moved over them. Like the random, format-specific framing, these banners also function as symbolic "action gaps" (GEHLEN, 1988, p.151) in constructing the routine perception of the display. That means an beholder who is used to dealing with this kind of projected display will, when perceiving these elements, "also see" the opportunities to act by clicking and scrolling (p.32). [34]

At this point we should analytically consider that contemplating a particular image always presupposes a physically active beholder; observing a picture requires not only a sensory stimulation on the part of the eye, but also productively active faculties of perception which generates attention in cooperation with memory and the current situation. This attention places the body in the right position in front of the picture and allows it to stay there for a while, thereby coordinating the eye, hand and legs, and thus it not only sees (hears and smells) but is also understood to complete complex actions of seeing and perceiving (BERGSON, 1991 [1896], pp.34, 77-132; POPPER, 1985 [1974], pp.89-91). Merely looking at a picture, i.e., directing my body towards it, is intrinsically an action. What is special about the image clusters discussed here is that several of these observational actions are symbolically pre-empted, and thereby heavily pre-structured, by the visual medium and its unique design elements. "Visual metaphors" (KRIPPENDORFF, 2006, p.166) (such as the mouse cursor, sidebar or image banner), partially cut-off framings and other possible design elements (such as an interplay between moving and static sections of images or the expectations of perceptions which are fulfilled or dashed) function as Rezeptionsvorgaben [frames for reception] (KEMP, 1998, p.187), which substantially organize the observational actions of potential recipients. What is central to the analysis in this respect and on this scale is therefore no longer the ideographically determined semantic figure of a cluster (see above), but rather the question—one that essentially concerns frame analysis or aesthetic impact (GOFFMAN, 1986 [1974]; on aesthetic impact see ISER, 1980)—of what a particular cluster does with its potential beholders, i.e., how it addresses them, which opportunities for perception or action it makes available to them, the means it uses for directing their attention, and what this in turn means for the recipients' attitude to what or whom is being seen. [35]

From a perspective like this, which addresses the processual interplay between observational actions and frames for reception, our example of the blog (among others) is presented as a dynamic, contrastive juxtaposition of a fixed profile picture on the right and an area for moving images on the left (a dynamic juxtaposition which cannot be captured by a screenshot and hence likewise cannot be reproduced in print). Depending on whether the scrolling slows down or stops altogether, depending on the manually induced focus, the profile picture containing the blog's images of nature, photos of tattoos and portraits enters a variable comparative horizon. In this contrastive reciprocal relationship between static and mobile parts of the depiction, the act of perceiving the scrolling acquires an explorative, investigative quality of reconnoitring the blog owner; the ongoing visual "games"—and here I am adapting WITTGENSTEIN's theory of "language games"—are set up "as objects of comparison which are meant to throw light [...] by way not only of similarities, but also of dissimilarities" (1958 [1953], p.50). [36]

Such visual games, meanwhile, have no intrinsic expressive value. Even if they are shown to contain something interesting or—depending on the beholder's point of view—relevant, they are not formations of signs or symbols, but rather (absolutely in the Wittgensteinian sense) a form of activity in which the recipient of a cluster first has to get involved (LACHMANN, 2012). But if the recipient does so, s/he is acting within a framework of predetermined opportunities for observation; exhausting these opportunities will result—in comparison to social encounters where one is physically present—in the relationship to his or her social counterpart (SCHÜTZ, 1945, p.552) being adjusted. When directing his or her gaze to the images of the counterpart, s/he is not reflected in the other's gazes and mimicked reactions and is not rejected by those gazes (SARTRE, 1992 [1943]); instead his or her gaze emerges from what SARTRE termed the coup d'œil [glimpse] (2014 [1943], p.294), and from the structures of mutual social orientation, changing its quality as it makes its way through the sequence of images: the gaze is no longer the medium of communicating "one's own against the other" (PLESSNER, 1970 [1941], p.45), but instead the medium for observing the other; its attitude is no longer that of a "we relationship" but rather that a "he [or she] attitude" which objectifies the counterpart (SCHÜTZ & LUCKMANN, 1974, pp.63, 72). [37]

From the perspective of frame analysis or aesthetic impact, the result of the reciprocity between the person who being perceived and the person doing the perceiving is that the ideal type or "implied"12) beholder, in the pre-structured completion of his/her observational actions, instinctively adopts a certain attitude towards the person to be observed; when going through the blog images via scrolling or clicking, s/he soon hits something, stops, changes directions, and keeps on focusing on new aspects, and is then adjusting not only his/her physical movements to fit in with the object of perception, but also the way of seeing which is adopted to capture and evaluate the thing or person to be seen, i.e., his/her whole style of observing and "knowing" (SCHÜTZ & LUCKMANN, 1974, 1989). [38]

In this respect, what becomes visible in the reciprocal structure outlined in our example's image cluster is, in other words, the symbolic, mediated organizational form of an explorative style of observing and knowing (SCHÜTZ, 1945). This style can indeed vary according to the subjective level of interest, personal acquaintance with the blogger, or degree of anonymity; the varieties of explorative attitude that can develop might tend to be appraising, investigative, or simply voyeuristic in nature. The likelihood and feasibility of these specific explorative iterations are already given by the frames for reception (in particular through the changing framing of individual images and the contrast ratio between static and moving depicted elements). [39]

In terms of the sociology of knowledge, we are dealing with a specifically mediated phenomenon of something which has always existed, even in other eras of history and in other social situations, namely ways of organizing situative options in society for perceiving one's surroundings, for taking action, and for acquiring knowledge; it is sociologically striking that in the case of the image cluster here, society's organization of particular observational actions and styles of knowing is realized not through genuinely ritual or ritualized framings and adjusted framings (as described by Gregory BATESON (1987 [1972]), Erving GOFFMAN, 1986 [1974] and others with games, art and science), but rather through the configuration of particular media artifacts (ISER, 1974; KEMP, 1992; REICHERTZ, 2007; WENZEL, 2002, 2007, 2009). In games, art or science, wherever a specifically playful, artistic or scientific attitude is performatively realized by adhering to collectively agreed and correspondingly sanctioned (i.e., ritualized) rules of the game, standards of behavior or manners of speaking, the material configuration of particular artifacts and fields of perception in architecture, film or digital image clusters predicate the "laws of its reception" (BENJAMIN, 1969 [1935], p.239) and the completion of particular guidelines for reception in the particular style of observing and knowing. [40]

There has been more or less direct reference in other contexts to this distinctive aspect of the "cultural significance" (WEBER, 1949 [1904], p.64) of technical media: Walter BENJAMIN, for instance, argued that the use of close-ups or slow motion in film predicated a critical attitude of expert appraisal among the assembled audience (an attitude which was ultimately instrumentalized for propaganda purposes by fascism) (1969 [1935]). Similarly, André MALRAUX showed that presenting art in museums and reproducing it in printed form are effectively the most effective means of the process of intellectualization (1957, p.21), for they not only spatially distance the implicit museum visitor and reader of illustrated books from any magical/religious, political or even just decorative function of art, but also confront him/her with systematic image comparisons and depictions of details, i.e., they familiarize the visitor/reader with a specifically intellectualist attitude to the work of art. A contemporary, digitalized form of the symbolic mediated organization of certain styles of observing and knowing has been adopted by Jürgen RAAB, Martina EGLI and Marija STANISAVLJEVIC (2010) for their case study of fields of perception and action in online pornography. The authors show how Internet pornography fails to deal discursively with its inherent problem of transgressing moral and ethical boundaries, instead inducing the implied recipient to differentiate, by means of the interaction between hand and eye when navigating, between legal and illegal pornography consumption and between "'clean' forms" and "'dirty'" varieties (p.206)13), i.e., adopting an attitude of moral classification. Viewed as a whole—and this is also shown in work by BENJAMIN and MALRAUX—organizing and modifying styles of observing and knowing using media is not a new phenomenon associated with digital media technologies. However, recent media developments and options for arranging and presenting images probably make it necessary for us to consider a systematic image analysis of this investigative dimension, bracketed by the fundamental premises of the classical individual picture analysis [41]

To summarize: 1. the heuristic focus of investigating an image cluster from the perspective of frame analysis or aesthetic impact is not contents, ideas, world views or self-perception, but rather the structure of the cluster's mediated field of perception and action and the frames for reception upon which this field of perception and action is "metacommunive[ly]" based (BATESON, 1987 [1972], p.183). The term Rezeptionsvorgabe [frame for reception] (KEMP, 1998, p.187) here refers to the particular design elements which induce the ideal type or implied recipient of an image cluster firstly to realize the particularly iconic structure of that cluster—the consequence described above of changing viewpoints—by means of his/her own observational actions, and secondly at the same time to appropriate a certain attitude towards who or whatever is being perceived. [42]

2. From the perspective of social sciences, interest in reconstructing these frames for reception—formulated with a nod to George Herbert MEAD—accordingly results from the "reactions" (JOAS, 1989, pp.100f., 114f.; MEAD, 1934, pp.75-77; 1987, p.206) which they generate among the recipients of an image cluster and which are structurally to be expected, i.e., the observational actions and styles of knowledge which they enable and predicate.14) Given that the structure of people's access to the world (in anthropological terms) is open in principle (GEHLEN, 1988; PLESSNER, 1975; WEBER, 1949 [1904]), and that there are consequently various ways by which we can modulate our reference to the world and ourselves in our instrumental approach to ourselves (BATESON, 1987 [1972]; GOFFMAN, 1986 [1974]; MÜLLER, 2014; SCHÜTZ, 1945; SOEFFNER, 1988, 2010; TURNER, 2017 [1969]) the significance of such frames for reception in the lifeworld (and hence also for the social sciences) lies not only in physically activating (or making passive) particular recipients but also in anticipating (in terms of technological media) certain styles of observing and knowing. [43]

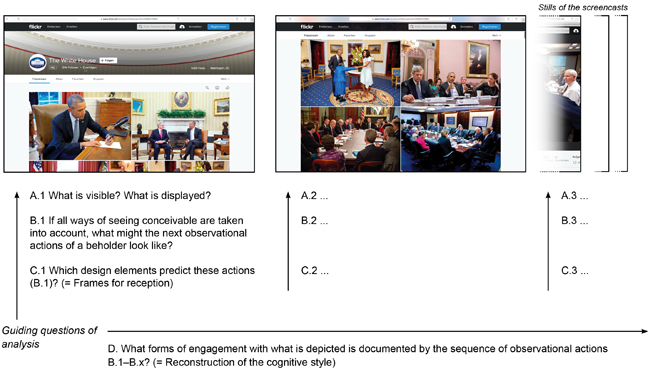

3. The mediated fleeting nature of this structure means that it is not easy to secure image clusters as data in order to conduct an investigation from the perspective of frame analysis and aesthetic impact. Transcriptions or static images can certainly only capture the interaction between the perceived and perceiving (the typical consequences for a cluster of changing viewpoints) in a highly fragmentary manner: transcriptions do not capture the graphic nature of an image, while static pictures do not reflect the observational action (i.e., the dynamic nature of the hand-eye relationship). In practical terms, this means that sooner or later the researcher will be forced to produce videographic logs of actions (SCHNETTLER & RAAB, 2008; TUMA, SCHNETTLER & KNOBLAUCH, 2013)—an "écriture performative" (WENZEL, 2009, p.259) which can capture the execution of the observations as a screencast. Such action logs are the only means of systematically detecting significant standards for reception (i.e., ones which enable and predicate particular observational actions) and conducting a step-by-step interpretive evaluation of the corresponding sequences of actions with respect to the cognitive style of paying attention to one's surroundings which is implemented by these actions. In accordance with the sequential array of observational actions and image variations, the interpretive evaluation of these action logs can be undertaken by means of a sequential analytical procedure (the individual steps of which do not need to—and indeed cannot—be spelled out here).15) Table 1 contains an overview of key heuristic questions for a sequential analytical evaluation, i.e., for forming objective potential readings, for identifying potential connections relating to action and design, and for formulating structural hypotheses.

Table 1: Key analytical questions on interpretively evaluating a videographic record of observational action. Stills are shown which

represent individual sequences of observational action. The key analytical questions are to be answered for every sequence

of action in the sense of formulating and falsifying interpretations. Key question D refers to the overall context of the

sequences of action. [44]

With figurative analysis (Section 3.1) and the analysis of frame theory and aesthetic impact (Section 3.2) along with the corresponding fundamental theories, we have two supplementary perspectives at our disposal for investigating image clusters. While the figurative analysis aims to explain the symbolism of the image compilation in question (for instance, representing world views, living standards, referencing the self or others), analyzing frame theory and aesthetic impact focuses on how styles of observing and knowing are organized by media. As mentioned above, both analytical perspectives supplement each other. [45]

4. Towards a Social Theory of Images

In Section 3.1 above I mentioned that (digital) image clusters can be compiled not only according to iconic principles, but also to narrative or classificatory ones. Methodologically speaking, we should bear this in mind with respect to the validity of figurative analyses—which are suitable for reconstructing iconic sections of the depiction, but not narrative or classificatory ones16). Yet this situation is also remarkable from a theoretical perspective, for the contrast between the potential iconic, narrative and classificatory principles/ideal types of image compilations also tells us something about the differing social functions of photography. In order to provide a sufficiently conceptual basis for describing these functions, I will first outline the three named types and principles of image compilation (Section 4.1) and then address the question of what is so specifically pictorial about iconic image clusters (Section 4.2). Finally I will describe an idiomatic (rather than indexical) social function for photography in iconic image clusters (Section 4.3). [46]

4.1 The types and principles of image compilation

Table 2 presents diagrams of the three ideal types17) of digital image compilation: with classificatory image clusters the compilation takes place according to the logic of subsumption, using conceptual or numeric criteria. That means the relevant individual images are compiled—if necessary independently from all other characteristics—with reference to their nominal affiliation with a certain theme ("profile pictures," "cupcakes," "Cuba relations"), to a certain event ("Manga Comic Con," "class trip," "at the X village festival"), or simply according to a date.

|

Type of image cluster |

Classificatory |

Narrative |

Iconic |

|

Principle of image compilation |

According to the logic of subsumption, i.e., the image compilation is determined by criteria of categorical assignability |

Sequential, i.e., the image compilation is determined by criteria of sequential coherence with respect to temporality and finality |

Iconic, i.e., the image compilation is determined by criteria of similarity/difference with respect to aiming for a deictic effect |

|

Primary socio-communicative meaning of the image compilation |

Illustrating particular circumstances

|

Representing the course of an event, an action, or a development |

Representing a particular quality of a thing or event, or an attitude |

Table 2: Types and principles of (digital) image compilation [47]

With narrative and iconic clusters, on the other hand, the qualitative interaction between the images is constitutive of an image compilation; we notice this with narrative image clusters, for instance, when the course of a social or political event or a biographical or ecological development needs to be presented. The image compilation occurs according to the criteria of sequential coherence with respect to the chronological and meaningful course of an event or development (see the example of the image cluster entitled "May 1, 2011" on the flickr page "The White House"18)). [48]

The same is true for iconic image clusters as for narrative clusters, with a key difference: the interaction between the content of their images is constitutive, but the image compilation itself once more develops an iconic quality. While the sequential arrangement of images adopts a narrative function in the case of narrative clusters (helping us to depict the course of events, actions and developments), the arrangement of images according to iconic criteria of similarity and difference develops the quality of a new, superordinate visual whole (helping us, for example, to symbolically bring social or immaterial positions to mind). An iconic cluster not only collects numerous images, as a narrative one would do, but is also an iconic entity sui generis—an image made from images which contrastively juxtaposes the things, events or people depicted, and interprets them within an iconic framework of similarity and difference. Even at the theoretical level, this autonomous pictorial quality requires a different, more abstract concept of the image than everyday language is able to provide: in a manner not dissimilar to the filmic montage of individual image sequences, the typical image cluster montage engenders iconic visual values and representational forms, which are created and structured differently to those of paintings or photographic prints. [49]

4.2 A brief digression on iconicity19)

The generally accepted hallmark of iconic depictions is their similarity relation to the things, events, people or situations they represent (BAUER & ERNST, 2010, pp.40-49). Similarity can mean illustrative similarity here, in the sense that a portrait reproduces a detailed abundance of physiognomical features. However, similarity can also exist in the sense of abstract analogies or structural homologies, as Charles Sanders PEIRCE (1965, 5.71) pointed out with his definition of the "icon." PEIRCE gives the example of a map, which resembles the territory it represents in just a few abstract characteristics: with respect to analogue relative distances, for instance, or borders between countries. Even though nation states and ships of state are totally separate entities, the ship of state as a figure of speech articulates structural homologies with respect to the social hierarchy, the need to be controlled, or the danger of sinking in both situations. [50]

The scalability of similarity relations is just one aspect to be theoretically considered. The mediated design of specific relationships of similarity and difference is even more important for the genesis of visual values (and for the theory of illustrative representational forms). The pictorial visual value of a self-portrait by Oscar KOKOSCHKA or Andy WARHOL, for example, is not determined simply by the similarity between the portraits and the body image of the portrayed person; the fact that these portraits allow us to discern something about the attitude or self-perception of the self-portraitist actually stems from the variations in form which these portraits undergo in portraying their protagonists—from the variations in proportion, contours, color impressions, or surface textures. In line with the principle of simultaneity for similarity and difference, the practical visual value and usefulness of a map is also only revealed because it resembles the territory in a few aspects—namely only in those which are of practical relevance, while all other aspects are ignored. If the depiction were authentic in every detail, it would lose its value as an aid to orientation. [51]

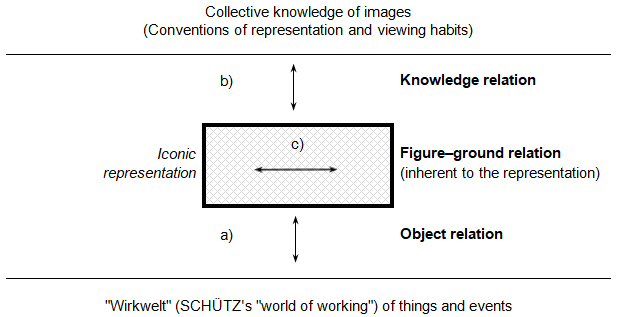

Thus varying the design of situations in the lifeworld by producing similarity relations at the same time as identifying differences allows iconic representations to highlight the qualitatively relevant aspects of a particular situation. This is true not only 1. for the object relation of iconic representation (which is by definition central to PEIRCE's semiotics), in other words for the relationship between illustrations, diagrams or metaphors of the object world. This kind of "iconic difference" (BOEHM, 2011) also proves to be representationally productive 2. with reference to adhering to or deviating from socio-cultural conventions of representation and visual habits (NÖTH, 1995, pp.126f.) as well as 3. figure-ground relations which are inherent to the representation (BOEHM, 2008, pp.19-34; SCHEMANN, 2011, pp.20-139). Thomas HOEPKER's picturesque "9/11" photography, for instance, or the apparently queer title cover of the "Männer" edition of Dummy magazine (MÜLLER & RAAB, 2014), or Max ERNST's spanking Madonna ("La vierge corrigeant l'enfant Jésus"): each of these representations foreground the special aspects of whatever political, societal or religious excerpts from life are being addressed, by first seizing societal conventions of representation and viewing habits, only to promptly deviate from them again. With recourse to the collective reserves of knowledge about images, they establish a representationally productive relationship between particular similarity relations and the comparable image representations and simultaneous experiences of difference. However, in drawings and photographs such as Edvard MUNCH's "The Kiss" or Miklos GAÁL's "Avenida Presidente António Carlos," the relationship between similarity and difference is elaborated inherently to representation in the sense of a figure-ground relation: the different forms of the individual image segments (the contrast between the detailed execution of parts of the body and the blurred facial features, and between the focused and grainy sections of the image) and aspects such as the suggested dramatic intensity of the kiss or the toy-like nature of the everyday world (once more with dramatic suggestion and repeatedly instrumentalized for the purposes of commercial advertising) come to the fore of these representations using genuinely iconic means. Thus, theoretically, we can follow on from PEIRCE, WITTGENSTEIN and BOEHM by considering that the iconic productive relationship of similarity and difference cannot only 1. be realized by means of symbolic object relations, but also (see Fig. 4), 2. with express recourse to collective reserves of knowledge about images, and 3. through figure-ground relations which are inherent to representation.

Figure 4: Modes of iconic difference [52]

Iconic image clusters potentially realize the relationship between similarity and difference in all three varieties given above: in the montage of various graphisms and mediated formats (combining, for instance, photos with drawings and sequences of moving images), the figure-ground relation takes effect once more, but this time beyond the boundaries of the individual image; in an abrupt shift between subjects, genres and styles (in a technical media montage of, for instance, tattoo photographs with representations of landscapes), the contrast between various representational conventions and viewing habits takes on an expressive value; and if—as is customary with portraits—naturalistically depicted sections (e.g., of a photographic nature) continue to be deliberately distorted by means of post-photographic coloring or images being unconventionally juxtaposed, the image-object relationship also proves to be an effective layer of expression, representationally speaking. Yet the type of image cluster which is here characterized as a relatively autonomous iconic form of expression and representation is realized not within the frame of the individual image, but rather in that of the image compilation: in the meaningful structure of an image cluster. [53]

4.3 Iconic means of the social display

The specifically pictorial nature of iconic image clusters is that just like other iconic representations they generate meaning by configuring relationships of similarity and difference, i.e., by focusing representation on the qualitatively relevant aspects of a particular situation. What differentiates such clusters from other iconic forms is the manner in which this is achieved: via image compilations. This is, however, more than a marginal note about constitutional analysis, for it tells us that photography in particular—viewed from BOURDIEU's perspective of its social functions—is by no means necessarily any different to what everyday common sense and visual philosophy long took for granted through observation and description: as the reflection of things and events, as an indication "that the things and events [they depict] must have existed" (BELTING, 2011, p.146; STIEGLER, 2009). [54]

The function of photography in iconic clusters is different, as is the way it is understood in practice: here it is used as a collectively shared means of expression which can be repeatedly arranged into new figures of expression. In this idiomatic application, the things being depicted are initially secondary, as are the events being attested to, and what it was perhaps once supposed to designate or mean individually. It all depends on which figures of expression are produced through the compilation with other photographs (or other graphic materials). This by no means excludes photographs in digital clusters which are also being used in their indexical depictive function, as profile pictures or for documenting everyday occurrences. However, for the composition and montage of pictorial figures of expression, for representing self-perceptions and attitudes to life, for self-stylizations, forming images, and announcing ideologies, they are collectively shared (reblogged, retweeted, pinned), i.e., exchanged and reproduced, as "anonymous photographs" (KELLER, 2016, p.118), in principle independently of potential indexical references, potentially ad infinitum and ubiquitously. What becomes structurally visible in these practices is the genesis or existence of a technical intersubjective reservoir of idiomatically applicable materials of expression20)—leading to the mediatization of a basic modality of social (co-)orientation: a "mediatization of seeing" (SOEFFNER & RAAB, 2004, p.254). It is namely not difficult to recognize that the iconic game with similarities and differences (with figure-ground relations, conventions of representation and object relations) is not an invention of cultural or technical media; instead it finds its anthropological basis and primary social manifestation in people's body language (as a physical figure-ground relation) (BOEHM, 2008; GOFFMAN, 1983), in the minute distinctions (BOURDIEU, 1984 [1979]) of social difference (as a representational game with conventions) and in the vestimentary and cosmetic self-portraits of everyday life (in object relations which reify ourselves) (SONNENMOSER, 2018). [55]

Thus, when we observe our social counterpart and become aware of hitherto unknown aspects of his/her behavior or character in conjunction with mimicry, gesturing and tone, or when we stylize ourselves and let a significant part of ourselves become visible via clothing and cosmetics, even at this non-technical level we are exercising the eye's capacity to differentiate, and addressing it in a mutual social exchange through a virtually endless sequence of iconic representations and performances. These performances are initially imitative, gestural and situative, then vestimentary and habitual, and ultimately—if we so desire or cannot tear ourselves away—they become mediated photographs. And so the fact that new opportunities for figuratively generating expression and elaborating relatively autonomous visual idioms are discovered in the multitude of photographs available in the media (and in their composition) may be due less to what KRACAUER (2014) and BENJAMIN (2015) described as a sentimental interest in photography, and more to the "vast social competency [to differentiate] of the eye" (GOFFMAN, 1979, p.25). [56]

For critical comments I would like to thank Anne SONNENMOSER. I am grateful to Nicola MORRIS, Dennis MOSER and Thore ZIELKE for their extensive work in preparing the English version of this article. I also would like to thank the two anonymous reviewers, and Katja MRUCK, the main editor of FQS. Finally, I am grateful to De Gruyter Publishing Company for permission to republish an expanded English version of the text and its analytical tables, plates, and figures. I am thankful to Allan GRANT for permission to republish "Fishermen Fishing for Chinook Salmon in Columbia River" (Plate 1), Alfred EISENSTAEDT for permission to republish "Tribesmen Straining at Their Oars" (Plate 1), Dimitri KESSEL for permission to republish "Yangtze River Essay: 2 Rows of Chinese Trackers, Harnassed and Bowed, River Towing a Junk up River" (Plate 1), and Wayne MILLER / Magnum Photos / Agentur Focus for permission to republish the "Railway Workers" (Plate 1).

1) This article was written within the research projects "The Visual Presentation of Self. Towards a Sociology of Personhood and Personal Probation" and "Styles of Life 2.0—On the Genesis and Structure of Lateral Sociation," both financed by the German Research Foundation. Accordingly, it should be noted, that this article is not a general introduction to the methodology of image analysis. It rather deals with recent practices of the digital montage of photographs. A first version of the now revised article was published under the title "Bildcluster. Zur Hermeneutik einer veränderten sozialen Gebrauchsweise der Fotografie" (MÜLLER, 2016). <back>

2) Translation of this and further German citations are mine. <back>

3) After the ancient Greek γράφειυ/γραφη, meaning scratch, bury, paint, embroider (KOCH, 1997, p.49). <back>

4) On methodology in general see FLECK (1986 [1935]), SOEFFNER (2004). <back>

5) Empirically speaking, assorted types of image cluster with varying structural characteristics can indeed be identified, see Section 4. <back>

6) This example is taken from a research project (see Note 1) dealing with the analysis of mediatized forms of self-presentation. This project's specific interest is about the attitude towards social life presented by individuals stylizing themselves in social media. <back>

7) The method of analysis described here is based on principles and procedures of research, comparable to grounded theory methodology in terms of epistemology. This applies in particular to the principle of permanent comparison and the axial adjustment of analysis to the theoretical knowledge and interests of the researchers. Nevertheless, the procedure described here does not lead to a grounded theory in which different cases are contrastively compared with each other (STRAUSS, 1987). The procedure of the image cluster analysis is rather a hermeneutic method of fine analysis of single cases. <back>

8) See Hans-Georg GADAMER on the notion of contemplation (1980) and Rudolf ARNHEIM's "perceptual concepts" (1974 [1954], pp.44-46), as well as MÜLLER on the same theme (2012, pp.154-155). <back>

9) Of course, neither the categorical identification of image types nor the reconstruction of their axial links are unconditional steps in the process. Visual perception, too, is a process which inevitably presumes socio-culturally acquired patterns of perception (ARNHEIM, 1974 [1954], pp.44-46; BERGSON, 1991 [1896], pp.47-63). It follows that the scientifically motivated process of identifying similarities in the image mainly is dependent on culture and positioning, and it must be carried out by a subject (the scientist). But this dependence of the process on positioning (Standortgebundenheit, MANNHEIM, 1994 [1964], p.29) is misunderstood as a fundamental problem of objectivity (compare with PRZYBORSKI & WOHLRAB-SAHR, 2010, pp.40-42). Quite apart from the Standortgebundenheit of each and any scientific knowledge, and quite apart from the fact that hermeneutics of the social sciences has (further) developed various approaches and principles for methodically checking this kind of Standortgebundenheit (i.e., the principles and routines of scepticism, of securing something as data, of extensive interpretation, of the provisional nature of results, etc.): what WITTGENSTEIN described as "noticing an aspect," plus, by extension, interpretively identifying similarities in an image only actually becomes possible thanks to the visual material amassed in a cluster—and consequently it is also materially limited by that image composition. Even when identifying similarities in an image the hermeneutic rule must apply: any interpretive statement must materially prove itself to its empirical object (GADAMER, 1988; MANNHEIM, 1994 [1964]). Being able to identify similarities in an image thus assumes 1. that the images which are arranged together indeed display certain shared qualities, whether in terms of the object being shown, the theme, or formal criteria, 2. that the individual types of images are cited in sufficient quantity, and 3. the fact (based on data) of an image composition which emphasizes commonalities or contrasts. Thus, analytically identifying similarity relations must have a qualitative, quantitative or compositional basis. In this respect, identifying visual similarities as part of a process of analytically interpreting images is anything but a subjective, arbitrary act. In point of fact, being able to identify similarities by observing the principle, rules and routines listed above results spontaneously from the structure of a particular cluster. <back>

10) On the term figuration see Oxford English Dictionary: "noun [mass noun] 1. ornamentation by means of figures or designs. Music the use of florid counterpoint: the figuration of the accompaniment comes out too strongly [count noun]: in modern music we have small ostinato figurations. 2 allegorical representation: the figuration of 'The Possessed' is much more complex. Middle English (in the senses 'outline' and 'making of arithmetical figures'): from Latin figuratio(n-), from figurare 'to form or fashion', from figura. figurative, adjective 1. departing from a literal use of words; metaphorical: a figurative expression. 2. (of an artist or work of art) representing forms that are recognizably derived from life"(STEVENSON, 2010, p.650). On figurative style analysis see MÜLLER (2009, pp.60f.). <back>

11) From a practical research perspective, a figurative analysis of this kind needs to be directed at the nature of the investigative material (and possibly at the dominant research interest too): even merely identifying the categories of various image types can tend to emphasis either the thematic and conceptual visual design elements (examples being pictures in the portrait category, pictures in the category of tattoo photographs, pictures in the category of nature depictions) or the formal and aesthetic ones (examples being pictures featuring a typical coloration or ornamentation or pictures showing a particular perspective on the body). And even the process of constantly comparing pictures (going beyond the primary identification of various images) can develop along assorted dimensions, concentrating both on the significant thematic or aesthetic similarities between different types of images and on significant dissimilarities within a type. Ultimately, Anselm STRAUSS' insight that there can be virtually no "strict instructions [...] for how to proceed in detail with all kinds of materials" (1987, p.8; MEY & DIETRICH, 2016) also holds for analytical processes of comparing pictures. It would certainly be insufficient for the process of comparing pictures to stagnate at the level of simple classification. Instead, WITTGENSTEIN's "noticing an aspect" has to serve as an opportunity for linguistically explicating the similar in the dissimilar (or vice versa, the dissimilar in the similar) and, by means of theoretical reflection, naming the pictures' meaningful relationships to each other. The multiplicity of manifestations and variations exhibited by the different similarity relations here functions not only as a verifying factor, but rather compels the falsification of already completed structural descriptions in favor of general and nascent abstract (i.e., comprehensive theoretical) formulations. <back>

12) On the analytical concept of the "implied reader" see ISER (1980, pp.60-67). The implied reader or beholder is the same hypothetical reader or beholder who has "always already thought ahead" (p.61). This concept should assist us in analytically identifying the proportion of potential text or image recipients whose attitude has already been symbolically pre-empted by the design of the text or image. <back>

13) RAAB et al. ascribe the analytical judgment-free distinction between "'clean' forms" and "'dirty' pornography" to Mary DOUGLAS. <back>

14) The statement that an artifact or social framing predicates a certain behavior (a chair predicates sitting, a red traffic light predicates stopping, a competition predicates the will to win, and image Cluster A predicates the Style X of observing and knowing), characterizes the typical purpose of a particular artifact or framing (which in society is consolidated within an artifact's design or a social framing) (KRIPPENDORFF, 2006; SCHÜTZ, 1970). <back>

15) See BOHNSACK (2009), OEVERMANN, ALLERT, KONAU and KRAMBECK (1979), RAAB (2008), SOEFFNER and HITZLER (1994), WERNET (2009). On the individual steps involved in evaluating image sequences, see in particular RAAB's analytical process (2008, pp.136-142, 156-164). <back>

16) For the analysis of classificatory clusters see also AIELLO and PARRY (2020). <back>

17) "Ideal type" is meant here entirely in the sense described by Max WEBER, namely that mixed forms are indeed found in empirical image clusters. <back>