Volume 20, No. 3, Art. 23 – September 2019

Theme in Qualitative Content Analysis and Thematic Analysis

Mojtaba Vaismoradi & Sherrill Snelgrove

Abstract: Qualitative design consists of various approaches towards data collection, which researchers can use to help with the provision of both cultural and contextual description and interpretation of social phenomena. Qualitative content analysis (QCA) and thematic analysis (TA) as qualitative research approaches are commonly used by researchers across disciplines. There is a gap in the international literature regarding differences between QCA and TA in terms of the concept of a theme and how it is developed. Therefore, in this discussion paper we address this gap in knowledge and present differences and similarities between these qualitative research approaches in terms of the theme as the final product of data analysis. We drew on current multidisciplinary literature to support our perspectives and to develop internationally informed analytical notions of the theme in QCA and TA. We anticipate that improving knowledge and understanding of theme development in QCA and TA will support other researchers in selecting the most appropriate qualitative approach to answer their study question, provide high-quality and trustworthy findings, and remain faithful to the analytical requirements of QCA and TA.

Key words: data analysis; qualitative research; qualitative content analysis; theme; thematic analysis

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. Theme in QCA and TA

2.1 Similarities of the theme between QCA and TA

2.2 Differences of the theme between QCA and TA

3. Some Pragmatic Aspects of Theme Development in QCA and TA

4. Conclusion

Qualitative research is a broad term encompassing different data collection and analytical approaches with the aim of providing cultural and contextual description and interpretation of social phenomenon. While there are variations between these research approaches in terms of data analysis and presentation of findings, they all contribute to both description and interpretation of phenomena (HOLLOWAY & GALVIN, 2017). QCA and TA are classified under the qualitative descriptive design. While description and interpretation are the main features of these two qualitative descriptive approaches, they are mainly suitable for researchers who prefer a higher level of description rather than an abstract interpretation. According to the international literature (VAISMORADI, TURUNEN & BONDAS, 2013; VAISMORADI, JONES, TURUNEN & SNELGROVE, 2016), QCA and TA are similar in terms of philosophical backgrounds, immersion in data, attention to both description and interpretation of data analysis, consideration of context during data analysis, and cutting across data for seeking themes. As a point of difference, within TA, a theme is considered to be latent content, but QCA researchers are free to decide between the level of data analysis when developing the category or the theme. Nevertheless, to develop a theme in both of these approaches, iterative or forward-backward movements and comparison of code clusters in relation to the whole data are required (VAISMORADI et al., 2013, 2016). Generally, during data analysis the researcher engages in a selection of the unit of analysis, subjective observation of the realities of the phenomenon, becoming an instrument for data analysis, looking for multiple realities behind the data, categorizing and finding themes from categories and through analytical insights to present an overall story line of data (CHO & LEE, 2014; CONNELLY & PELTZER, 2016; ERLINGSSON & BRYSIEWICZ, 2013). In addition, for back and forth movements between data, the researcher's previous knowledge and experiences, as well as previous research on the study phenomenon, help with building new understandings of phenomena (ERLINGSSON & BRYSIEWICZ, 2013). Moreover, the amount of effort and time spent on data analysis, as well as innovativeness, influence the quality of theme development. [1]

Themes or patterns are described as the final products of data analysis in the TA approach (BRAUN & CLARKE, 2006). Also, categories, themes and their subdivisions including subcategories and subthemes are the analytical products of data analysis using QCA (VAISMORADI et al., 2013, 2016). The decision on the development of each analytical product depends on the researcher's aim to reach descriptive (manifest content) or interpretive (latent content) levels of analysis, and the researcher's motivation in the analytical process (BENGTSSON, 2016; VAISMORADI et al., 2013, 2016). Therefore, the underlying commonality of both these qualitative approaches could be the development of the theme as the most abstract result, on the basis of rigorous coding and analyzing processes (VAISMORADI et al., 2016). [2]

"Theme" can be described as the subjective meaning and cultural-contextual message of data. Codes with common points of reference, a high degree of transferability, and through which ideas can be united throughout the study phenomenon can be transformed into a theme. In other words, a theme is a red thread of underlying meanings, within which similar pieces of data can be tied together and within which the researcher may answer the question "why?" (ERLINGSSON & BRYSIEWICZ, 2013). While a theme can be used to attend to the more implicit and meaning of data, other analytical products such as categories are related to the explicit and surface aspect of data analysis (VAISMORADI et al., 2013, 2016). Therefore, theme development can be a complex and time consuming process in comparison to the formation of categories (CONNELLY & PELTZER, 2016). [3]

The meaning of theme and related analytical products of QCA and TA has been described in previous studies (BRAUN & CLARKE, 2006; VAISMORADI et al., 2013). Some researchers have made efforts to present practical, innovative and evidenced-based instructions regarding how to develop the theme (VAISMORADI et al., 2013). Nevertheless, there is a lack of articulation about the similarities and differences of QCA and TA in terms of the theme. Therefore, our aim in this discussion paper is to address this gap in knowledge and present differences and similarities between these qualitative research approaches in terms of the theme as the final product of data analysis. [4]

In Section 1, we provide a description of the "theme" in two qualitative descriptive research approaches (HOLLOWAY & GALVIN, 2017): qualitative content analysis (QCA) and thematic analysis (TA) (BRAUN & CLARKE, 2006; VAISMORAD et al., 2013), along with our research experiences in the field of health sciences. We have taken into account current opinions about themes to strengthen our discussion and provide conclusions for multidisciplinary applications in section two. We aim to provide a brief description of the qualitative research design in connection with the main characteristics of QCA and TA (VAISMORADI et al., 2013). In the continuation of Section 2, we discuss the general features of the theme, and related similarities and differences between these two qualitative research approaches (BENGTSSON, 2016; MORSE, 2008; VAISMORAD et al., 2016), and we then suggest related practical considerations during data analysis. In Section 3, we present an overview of issues in theme development in QCA and TA, and suggest some pragmatic solutions for the improvement of the quality of data abstraction. [5]

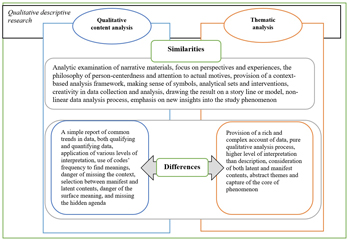

Similarities and differences between QCA and TA in terms of the theme and the process of theme development are rooted in commonalities and variations in their aims, focus, philosophical backgrounds and data analysis processes. In Figure 1 we show an overview of the comparison of QCA and TA, that is discussed in the following.

Figure 1: A general overview of the comparison of QCA and TA. Please click here for an enlarged version of Figure 1. [6]

2.1 Similarities of the theme between QCA and TA

In both QCA and TA, during the theme development process the researcher relies on the analytic examination of narrations related to social phenomena through breaking transcriptions into small units and performing data analysis. All sorts of data materials are transferred to textual format as transcription, and are read several times to achieve the sense of whole, to explore the main meaning behind the data and trace back related ideas for understanding hidden concerns in the data. Researchers bring themselves close to the data by highlighting main ideas as codes related to the phenomenon, which may lead to the theme through a constant comparison process. [7]

In the majority of qualitative descriptive approaches, the theoretical or philosophical framework and the philosophical model behind the data analysis and interpretation have not been indicated (KIM, SEFCIK & BRADWAY, 2017). The importance of sharing philosophical perspectives including "person-centeredness" and attention to actual behaviors and motivations in QCA and TA lies in the fact that researchers looking through a philosophical lens for theme development are influenced by their own judgment about the phenomenon and their ability to develop valuable and innovative knowledge. Researchers using QCA and TA can better ensure a reliable and rigorous line of reasoning that is consistent with the identity and construct of developed knowledge (THORNE, STEPHENS & TRUANT, 2016). Common philosophical perspectives in QCA and TA include similar flexibility or variability of theme development for achieving an understanding of the phenomenon. Therefore, users are encouraged to provide the required details of philosophical perspectives underpinning theme development, so that readers will be able to find rigor, reasonability, validity and comprehensiveness of the theme as the answer to the study question. [8]

A context-based framework of analysis is another similarity between QCA and TA. In theme development researchers must adhere to a systematic framework of data analysis. This shows that the they applied a stepwise process of data collection and analysis with verification strategies and checking (MORSE, 2015). Following methodical rules, along with a thorough detailed, systematic analysis and interpretation, prevents a premature closure of data analysis and can facilitate the development of findings that have not been intended to be explored and could be called the unintended theme (SCHMITT, 2005). Such a standardized approach is required from coding to theme development. A standardized verification of analytical products is ensured when researchers engage in triangulation, to ensure validation of findings in various rounds of data analysis. Furthermore, the use of a context-based, iterative framework, means that the standardized system of data analysis is not solely dependent on the linear analytic process, but personal experiences and knowledge can be incorporated, as well as personal subjectivity in favor of interpretive data analysis and innovation in theme development. [9]

In both QCA and TA, making sense of mediated factors such as linguistic symbols and underlying messages are complementary assets to the process of theme development. Symbols or metaphors are subjective meanings that individuals use in their communication with others to present their viewpoints and help others make sense of their inner world (CARTER & FULLER, 2016). QCA and TA researchers can combine meanings within data with symbols as meanings assigned by participants to their perspectives for developing the theme. The use of symbols in theme development makes readers to feel they belong to that community and the identification of each expressed idea becomes easier. A single symbol word in the theme can capture the meaning of the phenomenon more than many words (OMOJOLA, 2016). [10]

The same sets of analytical interventions with similar meanings, but under different titles, are seen within QCA and TA. While they have different terminologies, they are considered equivalent in terms of meaning in the analysis process. For instance, analytical keywords used in TA including "data corpus," "data item," "data extract," "code," and "theme" are the same as "unit of analysis," "meaning unit," "condensed meaning unit," "code," and "theme" in QCA, respectively. However, QCA researchers are free to develop the category instead of the theme; either they are willing to provide the category on the basis of the manifest content analysis or use the category development as the cornerstone for theme development (BENGTSSON, 2016; VAISMORADI et al., 2016). Briefly, categories are often used in the initial analytic phase of the study with the aim of developing a taxonomy for identifying relationships between pieces of data. On the other hand, the theme is developed in the later phase, when the purpose is to elicit meaning and essence from the data (MORSE, 2008; VAISMORADI et al., 2016). [11]

Encouraging creativity in findings is a common aspect of data analysis in both QCA and TA. In other words, creativity, intuition and innovation are crucial to data analysis and theme development. Traditional ways of thinking about objectivity and bias in standard and scientific research processes are therefore challenged (COPE, 2014). The researcher's creativity is required to deal with the empirical side of the data analysis method, to go beyond the current stance of knowledge and present relevant and creative themes in response to the research question (EVERS, 2016). [12]

The use of a storyline, map, or model for presenting the results is encouraged in QCA and TA. However, in only few studies the opportunity of graphing findings and mapping connections between categories and themes is used. The use of these strategies can facilitate understanding the whole picture of findings and judging the quality of theme development by journal reviewers and readers in relation to what is claimed by the researcher in the analysis process (VAISMORADI et al., 2016). With visual presentation relationships between and among underlying constructs can be checked, and revisions can be made, thus increasing reliability (FINFGELD-CONNETT, 2014). Further, by mapping and diagramming researchers support a valid integration, interpretation, and synthesis of findings. The importance of storyline and notes in QCA and TA has been relatively ignored, as they have often been considered the built-in part of more interpretive qualitative approaches including grounded theory methodology and interpretive phenomenology (HOLLOWAY & GALVIN, 2017). In terms of rigor, when a researcher presents the content of the theme and its structure in an understandable way, it becomes easy to find how the theme has been conceptualized during the analysis process. Even if the researcher aims at identifying or developing the theme (ELO et al., 2014), the construction of a schematic model outlining relationships between themes, their hierarchy, and connections are to be encouraged. [13]

A reiterative data analysis process has been recommended, so as to reassure the reader that the interpretation is representative of the data and the expectation of the finding as something unpredictable and innovative in data has been enhanced. Nevertheless, some commentators suggest that a non-linear effort to develop the theme and move forward and backward in the data is messy and in doing this the credibility and trustworthiness in analysis and reporting are undermined (SINKOVICS & ALFOLDI, 2012). While there must be a balance between being true to the method of theme development or going through the ladder of methodical process, there should be relatively flexible transitions between methodical stages. This suggestion is in line with the researcher's efforts to conceal the underlying meaning or essence of the data that is required for theme construction and prevent sacrificing rigor in data analysis and reporting. [14]

The importance of judging the quality of findings on the basis of new insights gained from the developed theme has been highlighted in QCA and TA. While the judgment on the quality of the study's findings is influenced by many factors (TONG, SAINSBURY & CRAIG, 2007), the developed theme can be evaluated in terms of new insights provided about the study phenomenon. For instance, whether the theme represents all aspects of the phenomenon adequately and is representative of all participants, whether there is a consideration of alternative explanations in the data and consideration of negative cases, and if the analysis encompasses participants' implicit and explicit perspectives as well as their emotions (ANDERSON, 2010). The theme should be novel, but at the same time should be truly representative of participants' experiences, views and so forth. The researcher's self-reflexivity helps with demonstrating the strengths and shortcomings of the data analysis product. Furthermore, the recognition of researchers' own beliefs and role in the research is important when evaluating authenticity of the theme. Particularly so, in nursing science, the coherence between the developed theme and its implications for knowledge, practice, policy-making and research are emphasized (TRACY, 2010). [15]

2.2 Differences of the theme between QCA and TA

Researchers using QCA focus on providing a simple, but in-depth report of commonalities and differences in the data. However, in TA it is expected that the researcher will provide a rich and complex nuanced interpretation of the data as the theme. With qualitative descriptive research in general, the researcher's aim is to uncover meanings in data and reveal hidden complexities, and provide illustrations of these complexities, which is recognized as a difficult task, especially in TA (SANDELOWSKI, 2010). It is expected that the researcher takes note of ambiguities, but also acknowledges the more overt meanings; to accomplish this, researchers must bring into play their own subjectivity, but retain sensitivity to the participants' accounting of life. While both QCA and TA researchers speak on participants' behalf through uniting their voices and simultaneously taking care of differences within their perspectives, the presentation of results as the theme may be different for the two approaches, indicating the underpinning aim of theme development and level of abstraction. Researchers using QCA may prefer to work with simplicities and overt data by going through a large amount of written materials to obtain easy-achieved classifications and manifest contents to develop categories. On the other hand, those using TA require an exhaustive and non-stop process of abstraction and in-depth analysis from the beginning to reach the theme. It is believed that high-quality qualitative research is marked by a thick description, and rich complexity of findings rather than deductive precision (TRACY, 2010). With the increase of the abstraction level in any theme development, both aesthetic and creative terminology may be used in the presentation and structure of the theme. The complexity and aesthetic aspects of the theme can motivate readers to reflect on data and relate the findings to their own personal perspectives. It is expected that readers' shared and similar experiences are sufficient to relate to the meaning of the theme and even apply it in practice. Analyzing data qualitatively and also quantifying data are possible in QCA, but in TA a purely qualitative account of data is utilized. By quantifying data in QCA, it does not mean that words and concepts are transformed into numbers for data analysis, as in the tradition of quantitative data analysis, but it can mean that the frequency of the same or similar codes in the transcription is considered important for the development of the category or the theme. It is believed that the importance of the theme is influenced by underlying codes in the entire dataset, and that something important regarding the research question can be captured (SANDELOWSKI & LEEMAN, 2012). In short, quantifying data as in QCA can be considered an intermediary step in data analysis with the aim of convergence in data and elaboration of details, which is commonly known as data analysis triangulation in mixed-method studies (PALINKAS et al., 2015; SWAN, 2013; WHEELDON, 2011). Theme construction can also be taken as an advantage in qualitative data analysis, since it helps with seeing a broad picture of the data (STOTT & Graven, 2013). [16]

Using QCA makes it possible to be descriptive, but also has the option of conducting various levels of interpretation. In comparison, TA is believed to be both descriptive and interpretative. Although the use of description and interpretation are the common features of both QCA and TA, a key difference lies in the differing level of description and interpretation (SANDELOWSKI, 2010; VAISMORADI et al., 2013, 2016). It is suggested that such variations in theme development are rooted in dissimilarities in abstraction levels between QCA and TA (VAISMORADI et al., 2016). The infinite process of interpretation starts from coding as a cyclic process; the researcher defines the level of abstraction (POLIT & BECK, 2018). The use of description in QCA does not transgress from the tradition of qualitative research, because description is required to begin interpretation. The difference between QCA and TA in terms of various levels of description and interpretation can be attributed to the emphasis in QCA of a more step-by-step method of data analysis on the background, context and thick findings under the hue of frequency of codes as a complementary to theme development. On the other hand, comparatively, TA is fundamentally an interpretative research approach, relying increasingly on the researcher's subjectivity and personal insight to interpret data for theme development. Nevertheless, the researcher of both these approaches is not exempt from providing an appropriately thick description as a matter of rigor upon which an interpretation and the theme have been developed. [17]

Conversely and in comparison to TA, a researcher conducting a QCA analysis will have considered the frequency of codes for theme development, which can enhance the possibility of missing the context, unless interpretive tools of finding significant meanings and themes are used hand in hand with code frequency. Theme development cannot work without appropriate socialization within the context and gaining experience prior to and during data collection. Some controlled de-contextualization happens in the process of data analysis through the coding process, when the researcher temporarily removes parts of the text from its original context for cross-comparisons toward developing the theme (MALTERUD, 2012). Context of data is the central part of the thick description of phenomenon and data in qualitative research. The aim with both QCA and TA is not to provide generalizable findings, but rather to provide contextualized and comprehensive understandings of the phenomena under study for possible transferability (POLIT & BECK, 2010). In other words, facilitating the transferability of findings to readers requires attention to the description of context and fitness of developed themes to the original context of the data (VAISMORADI et al., 2016). Such a fitness empowers readers to make appropriate judgments of similarity of the study context to their own environment, which is required for devising practical implications of findings. [18]

With QCA, researchers can select between manifest and latent contents, but this creates systematic concern with surface rather than hidden meanings. On the one hand, TA researchers need quite abstract themes and identification, and to capture the core of phenomenon. On the other hand, the analysis of manifest data in QCA means that some researchers stop the process of data collection and analysis when they reach categories and even sometimes introduce them as latent meanings or themes. As a criterion to evaluate the depth of analytical products, the theme or story is based on evidence in the data, with a focus on meaning rather than superficial measurement. Self-awareness and sensitivity, rather than being overemotional or self-absorbed, are the basic personal characteristics of the researcher to go beyond manifest content and make meaning from the data. Theme development depends on the interpretation of meaning and researchers must make sense of data through phrasing and para-phrasing. When researchers move to different levels of abstraction, they open the possibility of losing the meaning given to participants' experiences, especially when the focus is on hidden meanings (HOLLOWAY & BILEY, 2011; VAISMORADI et al., 2016). Placement of the theme or storyline to the participants' accounts and cross-checking by participants and peers can ensure that the researcher has developed an evidenced-based theme and captured what is claimed to be hidden in the participants' account, which is beyond manifest content. [19]

3. Some Pragmatic Aspects of Theme Development in QCA and TA

Theme development is influenced by the presence of inconsistency between analysis methods and the study aim. QCA and TA can be used to develop the theme based on an available theory and in conjunction with more interpretive approaches to develop a theory. Nevertheless, these methods alone do not develop a theory. It has been suggested that descriptive research approaches have advantages over simple coding processes whenever the research question is embedded in prior theory and can be answered through the exploration of meaning and narration construction (GLÄSER & LAUDEL, 2013). The high level of abstraction in the theme means that several basic analytic procedures have been conducted at various levels during theme development. The theme is shaped when the researcher can find recurrent ideas based on similarities and differences in the data (CONNELLY & PELTZER, 2016; GRANEHEIM, LINDGREN & LUNDMAN, 2017). While theme development in qualitative descriptive approaches is flexible, it depends on the experience and expertise of the researcher to unveil underlying meanings (MOHAMED, RAGAB & ARISHA, 2016). [20]

Theme development starts as soon as the researcher has determined the focus of the study. During coding data, interpretation and abstraction are started and progressed. Analyzing data along with data collection is an opportunity to test interconnections between codes, and to find themes that fit the data (KNUDSEN et al., 2012). In other words, similar grounds related to similar issues are found and compared until they are explained by the theme as an umbrella. Theme can further be divided into subthemes to cover the different levels of similarities and differences (INDULSKA, HOVORKA & RECKER, 2012; SNOWDEN & MARTIN, 2011; THYME, WIBERG, LUNDMAN & GRANEHEIM, 2013). [21]

Theme development is the basis of qualitative research and consideration of qualitative data analysis without the development of thematic statements as synthesizing and integrating data segments is problematic (SANDELOWSKI & LEEMAN, 2012). In addition to the analytical importance of the theme, it is the translation of participants' perspectives into the language of decision-making and practice. The developed theme is the summary of daily actions and reactions of participants when faced with certain phenomena, and can be used to design interventions in healthcare disciplines (COLORAFI & EVANS, 2016). Some believe that the theme can be emerged, if non-hypothesized and unasked questions are addressed in the stories and narrations of participants, and when there are consistent and sufficient data to justify them (MASSEY, 2011). However, theme development even in the emergent form is an active process and the researcher needs to apply active hypothesizing and probing of the data throughout analysis. If the researcher brings the theme to the data and fixes it prior to the study, for example based on the topic of the interview process, the identity of theme development is changed from an inductive to a deductive approach (ASSARROUDI, HESHMATI NABAVI, ARMAT, EBADI & VAISMORADI, 2018; MAYRING, 2014). In other words, the active role of the researcher in theme development prevents the use of emerging theme, because this implies that the theme has appeared without active thinking or attention (WARD, FURBER, TIERNEY & SWALLOW, 2013). Conclusion of the theme based on personal taste includes a manual bias introduced to data by the researcher (INDULSKA et al., 2012). [22]

Furthermore, under-development of the theme with less details or depth, and over-elaboration with many analytical distinctions placed under a higher-level of abstraction should be avoided (CONNELLY & PELTZER, 2016; WU, THOMPSON, AROIAN, McQUAID & DEATRICK, 2016) in favor of improving understanding of knowledge about a phenomenon (HOON, 2013). The underdeveloped theme with a lack of substantive support in data is the result of premature closure of data collection and analysis, lack of knowledge of data analysis, and confusion in the difference between the category and the theme (CONNELLY & PELTZER, 2016). This does not contradict the normal analytical process in which some themes may receive more support and others may receive less support from data, further work on the integration and synthesis of the theme can be conducted. Nevertheless, researchers should show that the theme is consistent and reliable across and within data, to provide an in-depth understanding of the phenomena (FLOERSCH, LONGHOFER, KRANKE & TOWNSEND, 2010). [23]

To create transparency in theme development the researcher needs to document all analytical movements from selecting units of data to developing the theme, to demonstrate the robustness of the findings (NOBLE & SMITH, 2014). In this way replication of the process is made possible, and clarity is gained regarding how inferences about the human behavior have been made (RENZ, CARRINGTON & BADGER, 2018). In this respect, the use of field notes, reflexive diaries and decision trails have been suggested to researchers (GRANEHEIM et al., 2017; WARD et al., 2013). With these tools researchers can acknowledge personal beliefs and biases that may influence the interpretation process and theme development (CONNELLY & PELTZER, 2016). The use of checklists for the evaluation of the research process, and holding discussions in an interdisciplinary team for quality appraisals, have a positive and uplifting effect on theme development (BOEIJE, VAN WESEL & ALISIC, 2011). When the theme is developed, explanations or support for it using examples from the data are needed. Provisionally, a name is given to the theme, and through forward-backward movements and review of explanations and interpretations, the researcher eventually finds a more appropriate name for it (CONNELLY & PELTZER, 2016). [24]

We have presented similarities and differences between QCA and TA in terms of theme development. As far as possible we have supported our arguments with the international literature. We drew on relevant scholarly work from a range of disciplines including the health sciences, education, and sociology, so as to gain comprehensive insight into this topic. We consider that by taking a broad international reach, we were able to strengthen our arguments and clarify the main opinions in this area. Our discussion can add to interdisciplinary discussions required to advance ideas and agreements about theme development, and reduce noted ambiguities surrounding theme development in QCA and TA. A common understanding of theme development in QCA and TA facilitates evaluating the results of data analysis, improves rigor, and leads to deeper understandings of complex human phenomena for designing interventions for education, research and practice. Lastly, researchers are then better enabled to choose the most appropriate approach to answer their study question, provide high-quality and abstract findings, and remain faithful to the analytical requirements of QCA and TA. [25]

Anderson, Claire (2010). Presenting and evaluating qualitative research. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 74(8), Art. 141, https://doi.org/10.5688/aj7408141 [Date of Access: August 28, 2019].

Assarroudi, Abdolghader; Heshmati Nabavi, Fatemeh; Armat, Mohammad Reza; Ebadi, Abbas & Vaismoradi, Mojtaba (2018). Directed qualitative content analysis: The description and elaboration of its underpinning methods and data analysis process. Journal of Research in Nursing, 23(1), 42-55, https://doi.org/10.1177/1744987117741667 [Date of Access: August 26, 2019].

Bengtsson, Mariette (2016). How to plan and perform a qualitative study using content analysis. Nursing Plus Open, 2, 8-14, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.npls.2016.01.001 [Date of Access: August 26, 2019].

Boeije, Hennie R; van Wesel, Floryt & Alisic, Eva (2011). Making a difference: Towards a method for weighing the evidence in a qualitative synthesis. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 17(4), 657-663.

Braun, Virginia & Clarke, Victoria (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77-101.

Carter, Michael J. & Fuller, Celene (2016). Symbols, meaning, and action: The past, present, and future of symbolic interactionism. Current Sociology, 64(6), 931-961.

Cho, Joung Ji & Lee, Eun-Hee (2014). Reducing confusion about grounded theory and qualitative content analysis: Similarities and differences. The Qualitative Report, 19(32), 1-20, https://nsuworks.nova.edu/tqr/vol19/iss32/2 [Date of Access: August 26, 2019].

Colorafi, Karen Jiggins & Evans, Bronwynne (2016). Qualitative descriptive methods in health science research. HERD: Health Environments Research & Design Journal, 9(4), 16-25.

Connelly, Lynne & Peltzer, Jill (2016). Underdeveloped themes in qualitative research: Relationship with interviews and analysis. Clinical Nurse Specialist, 30(1), 52-57.

Cope, Diane G. (2014). Methods and meanings: Credibility and trustworthiness of qualitative research. Oncology Nursing Forum, 41(1), 89-91.

Elo, Satu; Kääriäinen, Maria; Kanste, Outi; Pölkki, Tarja; Utriainen, Kati & Kyngäs, Helvi (2014). Qualitative content analysis: A focus on trustworthiness. SAGE Open, 4(1), 1-10, https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244014522633 [Date of Access: August 26, 2019].

Erlingsson, Christen & Brysiewicz, Petra (2013). Orientation among multiple truths: An introduction to qualitative research. African Journal of Emergency Medicine, 3(2), 92-99, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.afjem.2012.04.005 [Date of Access: August 26, 2019].

Evers, Jeanine C. (2016). Elaborating on thick analysis: About thoroughness and creativity in qualitative analysis. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 17(1), Art. 6, http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-17.1.2369 [Date of Access: June 27, 2019].

Finfgeld-Connett, Deborah (2014). Use of content analysis to conduct knowledge-building and theory-generating qualitative systematic reviews. Qualitative Research, 14(3), 341-352.

Floersch, Jerry; Longhofer, Jeffrey L.; Kranke, Derrick & Townsend, Lisa (2010). Integrating thematic, grounded theory and narrative analysis: A case study of adolescent psychotropic treatment. Qualitative Social Work, 9(3), 407-425.

Gläser, Jochen & Laudel, Grit (2013). Life with and without coding: two methods for early-stage data analysis in qualitative research aiming at causal explanations. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 14(2), Art. 5, http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-14.2.1886 [Date of Access: June 27, 2019].

Graneheim, Ulla H.; Lindgren, Britt Marie & Lundman, Berit (2017). Methodological challenges in qualitative content analysis: A discussion paper. Nurse Education Today, 56, 29-34.

Holloway, Immy & Biley, Francis C. (2011). Being a qualitative researcher. Qualitative Health Research, 21(7), 968-975.

Holloway, Immy & Galvin, Kathleen (2017). Qualitative Research in nursing and healthcare (4th ed.). Oxford: Wiley Blackwell.

Hoon, Christina (2013). Meta-synthesis of qualitative case studies: An approach to theory building. Organizational Research Methods, 16(4), 522-556.

Indulska, Marta; Hovorka, Dirk S. & Recker, Jan (2012). Quantitative approaches to content analysis: Identifying conceptual drift across publication outlets. European Journal of Information Systems, 21(1), 49-69.

Kim, Hyejin; Sefcik, Justine S. & Bradway, Christine (2017). Characteristics of qualitative descriptive studies: A systematic review. Research in Nursing & Health, 40(1), 23-42.

Knudsen, Line V.; Laplante-Levesque, Ariane; Jones, Lesley; Preminger, Jill E.; Nielsen, Claus; Lunner, Thomas; Hickson, Louise; Naylor, Graham & Kramer, Sophia E. (2012). Conducting qualitative research in audiology: A tutorial. International Journal of Audiology, 51(2), 83-92.

Malterud, Kirsti (2012). Systematic text condensation: A strategy for qualitative analysis. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 40(8), 795-805.

Massey, Oliver T. (2011). A proposed model for the analysis and interpretation of focus groups in evaluation research. Evaluation and Program Planning, 34(1), 21-28.

Mayring, Philipp (2014). Qualitative content analysis: Theoretical foundation, basic procedures and software solution, https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-395173 [Date of Access: July 5, 2019].

Mohamed, Mona; Ragab, Mohamed A.F. & Arisha, Amr (2016). Qualitative analysis methods review. Technical Report, 3S Group, College of Business, Dublin Institute of Technology, https://doi.org/10.21427/D75Z25 [Date of Access: July 5, 2019].

Morse, Janice M. (2008). Confusing categories and themes. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Morse, Janice M. (2015). Critical analysis of strategies for determining rigor in qualitative inquiry. Qualitative Health Research, 25(9), 1212-1222.

Noble, Helen & Smith, Joanna (2014). Qualitative data analysis: A practical example. Evidence-based Nursing, 17(1), 2-3, http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/eb-2013-101603 [Date of Access: July 5, 2019].

Omojola, Oladokun (2016). Using symbols and shapes for analysis in small focus group research. The Qualitative Report, 21(5), 834-847, https://nsuworks.nova.edu/tqr/vol21/iss5/3 [Date of Access: August 26, 2019].

Palinkas, Lawrence A.; Horwitz, Sarah M.; Green, Carla A.; Wisdom, Jennifer P.; Duan, Naihua & Hoagwood, Kimberly (2015). Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 42(5), 533-544.

Polit, Denise F. & Beck, Cheryl Tetano (2010). Generalization in quantitative and qualitative research: Myths and strategies. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 47(11), 1451-1458.

Polit, Denise F. & Beck, Cheryl Tetano (2018). Essential of nursing research: Appraising evidence for nursing practice. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Renz, Susan M.; Carrington, Jane M. & Badger, Terry A. (2018). Two strategies for qualitative content analysis: An intramethod approach to triangulation. Qualitative Health Research, 28(5), 824-831.

Sandelowski, Margarete (2010). What's in a name? Qualitative description revisited. Research in Nursing & Health, 33(1), 77-84.

Sandelowski, Margarete & Leeman, Jennifer (2012). Writing usable qualitative health research findings. Qualitative Health Research, 22(10), 1404-1413.

Schmitt, Rudolph (2005). Systematic metaphor analysis as a method of qualitative research. The Qualitative Report, 10(2), 358-394, https://nsuworks.nova.edu/tqr/vol10/iss2/10 [Date of Access: August 26, 2019].

Sinkovics, Rudolf R. & Alfoldi, Eva A. (2012). Progressive focusing and trustworthiness in qualitative research. The enabling role of computer-assisted qualitative data analysis software (CAQDAS). Management International Review, 52(6), 817-845.

Snowden, Austyn & Martin, Colin R. (2011). Concurrent analysis: Towards generalisable qualitative research. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 20(19‐20), 2868-2877.

Stott, Debbie & Graven, Mellony (2013). Quantifying qualitative numeracy interview data. Proceedings of the 19th Annual Congress of the Association for Mathematics Education of South Africa, https://www.ru.ac.za/media/rhodesuniversity/content/sanc/documents/P23.pdf [Date of Access: July 5, 2019].

Swan, Melanie (2013). The quantified self: Fundamental disruption in big data science and biological discovery. Big Data, 1(2), 85-99, https://doi.org/10.1089/big.2012.0002 [Date of Access: August 26, 2019].

Thorne, Sally; Stephens, Jennifer & Truant, Tracy (2016). Building qualitative study design using nursing's disciplinary epistemology. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 72(2), 451-460.

Thyme, Karin Egberg; Wiberg, Britt; Lundman, Berit & Graneheim, Ulla Hällgren (2013). Qualitative content analysis in art psychotherapy research: Concepts, procedures, and measures to reveal the latent meaning in pictures and the words attached to the pictures. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 40(1), 101-107.

Tong, Allison; Sainsbury, Peter & Craig, Jonathan (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 19(6), 349-357, https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzm042 [Date of Access: August 26, 2019].

Tracy, Sara J. (2010). Qualitative quality: Eight "big-tent" criteria for excellent qualitative research. Qualitative Inquiry, 16(10), 837-851.

Vaismoradi, Mojtaba; Turunen, Hannele & Bondas, Terese (2013). Content analysis and thematic analysis: Implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nursing & Health Sciences, 15(3), 398-405, https://doi.org/10.1111/nhs.12048 [Date of Access: August 26, 2019].

Vaismoradi, Mojtaba; Jones, Jacqueline; Turunen, Hannele & Snelgrove, Sherrill (2016). Theme development in qualitative content analysis and thematic analysis. Journal of Nursing Education and Practice, 6(5),100-110, https://doi.org/10.5430/jnep.v6n5p100 [Date of Access: August 26, 2019].

Ward, Deborah J.; Furber, Christine; Tierney, Stephanie & Swallow, Veronica (2013). Using framework analysis in nursing research: A worked example. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 69(11), 2423-2431.

Wheeldon, Johannes (2011). Is a picture worth a thousand words? Using mind maps to facilitate participant recall in qualitative research. The Qualitative Report, 16(2), 509-522, https://nsuworks.nova.edu/tqr/vol16/iss2/11 [Date of Access: August 26, 2019].

Wu, Yelena P.; Thompson, Deborah; Aroian, Karen J.; McQuaid, Elizabeth L. & Deatrick, Janet A. (2016). Commentary: Writing and evaluating qualitative research reports. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 41(5), 493-505, http://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsw032 [Date of Access: August 26, 2019].

Mojtaba VAISMORADI is a professor of nursing science at Nord University, Norway, and an associate researcher at Swansea University, UK. His main fields of studies are patient safety and medicines management using both quantitative and qualitative designs. Mojtaba is the editor of international journals in the area of health sciences and actively collaborates in international research projects. He is interested in methodological issues surrounding the qualitative research design, especially content analysis and thematic analysis, and has published articles in international journals to help with the clarification of these two qualitative approaches, and making it easier for researchers to choose between them and perform a high quality data analysis.

Contact:

Mojtaba Vaismoradi (PhD, MScN, BScN), Full Professor

Faculty of Nursing and Health Sciences

Nord University

8049 Bodø

Norway

Tel.: + 47 75517813

E-mail: mojtaba.vaismoradi@nord.no

URL: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Mojtaba_Vaismoradi

Dr Sherrill SNELGROVE is an associate professor in the Department of Public Health, Policy and Social Sciences and Dean of Academic Leadership (Research Integrity and Ethics) at Swansea University, UK. She has previously worked as a National Health Service (NHS) nurse manager and has over twenty years' experience as a lecturer and researcher. Sherrill has conducted both qualitative and quantitative research into chronic pain of older people living in the community, medication management of older people with dementia, advanced health care practice, health care professionals' experiences of stress and pedagogical research. She is one of just a few researchers at Swansea University, proficient in interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA). Sherrill has a track record in successful PhD supervision and is currently PhD supervisor to national and international students researching health and social care topics. A main role is leading on research integrity and ethics at Swansea University with a mandate to oversee and develop ethics, research misconduct and research governance procedures.

Contact:

Sherrill Snelgrove (RGN, BSc (Hons), M.Phil. PhD, PGCE, SFHEA), Associate Professor

College of Human and Health Sciences

Swansea University

Department of Public Health, Policy and Social Sciences

Singleton Campus

Wales, UK

Tel.: +44 1792 513466

E-mail: s.r.snelgrove@swansea.ac.uk

URL: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Sherrill_Snelgrove

Vaismoradi, Mojtaba & Snelgrove, Sherrill (2019). Theme in Qualitative Content Analysis and Thematic Analysis [25 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 20(3), Art. 23, http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-20.3.3376.