Volume 21, No. 2, Art. 18 – May 2020

Understanding, Seeing and Representing Time in Tempography

Vibeke Kristine Scheller

Abstract: I discuss in this article how ethnographers understand, see and represent time by presenting a research study of a newly established cardiac day unit. Previous discussions of time in relation to ethnography mainly revolved around choosing an appropriate tense for writing up the text, and few studies attempted to develop a framework for conducting time-oriented ethnography in organizations, i.e., tempography. I argue that doing tempography requires considerations in several phases of the research process: how we understand time through theory; how we see time in different qualitative methods; and how we represent time in writing. I present empirical findings that illustrate different ways that time emerges in the ethnographic research process, for example, in observational accounts, through depictions and narratives that support different temporal conceptualizations, patients' stories about their trajectories and as ethnographic accounts of professional work. I contend that ethnographers need to consider: 1. methodological temporal awareness as recognition of coexisting temporal modes in qualitative data; 2. temporal analytical practices as understanding time and temporality through different theoretical concepts; and 3. multi-temporal merging as a matter of representing diverse perspectives in ethnographic writing.

Key words: time; temporality; ethnography; organization studies; time objects; temporal work; trajectories

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Analysis of Time and Temporality in the Study

2.1 Objects of time

2.2 Temporal work

2.3 Trajectories

3. Tempographic Methodology

4. Introducing Same-Day Discharge in a Cardiac Day Unit

5. Empirical Illustrations of Time in a Cardiac Day Unit

5.1 Procedure plans as objects of time

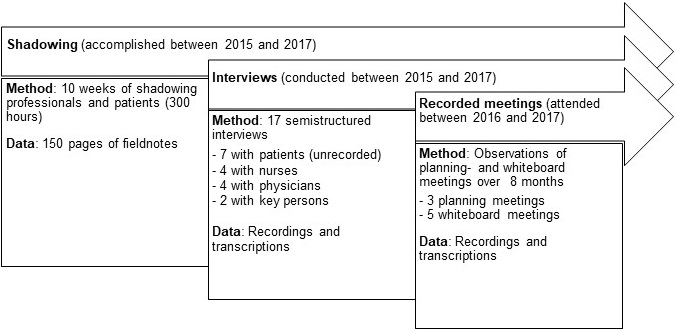

5.2 Dealing with postponements as temporal work

5.3 Professional dilemmas in patient trajectories

6. Temporal Awareness, Practices and Merging in Tempography

7. Conclusion

Throughout this article, I will discuss the implications of seeing, understanding and representing time in ethnography by presenting the process of doing tempography. Tempography is a term coined by ZERUBAVEL in 1979, which means an organizational ethnography describing socio-temporal structures in a hospital. It is therefore related to the use of the tempography concept by researchers of urban development and neighborhoods, i.e., as temporal geography (AUYERO & SWISTUN, 2009; HARVEY, 2015). However, for ZERUBAVEL (1979), tempography is not just about laying out the geography of time, but describing a setting of practiced time patterns. The role of ethnography in organizations has been debated throughout research communities, also in FQS, where BERGMAN (2003) appeals for a more explicit focus on the organization in ethnographies, i.e., what the study explains about organizations and not just a study of a phenomenon within an organization. Accordingly, I argue that researchers need to ethnographically engage with time in research projects and not just studying time within an organizational setting—for which ZERUBAVEL (1979) has been criticized (BOBYS, 1980). [1]

Ethnographers unavoidably have to choose between past and present tense when writing up, freezing their descriptions in a specific time (WILLIS, 2010). This temporal perspective has been explored by many ethnographers and debated in seminal texts such as "Time and the Other" by Johannes FABIAN (1983). For FABIAN, the freezing of studied cultures in the stasis of present tense leads to a problematic othering of the studied subjects. The present was experienced in the past by the researcher, but either written up using past or present tense, both forming temporal problems for the studied culture. Ideally, a culture's members should appear as partners in dialogue, which is an important scope for anthropologists, i.e., that they provide the studied culture with an active voice. Freezing this voice in a specific time indicates that the people of the culture become the other of the ethnographer, spatially and temporally different from them. The use of past tense assumes that the culture (or organization) no longer functions this way and that their practice is a thing of the past, whereas the use of the present tense assumes that their practice is frozen in the past and unchanged. Another significant discussion related to time and ethnography has been the paradox of studying non-linear organizational processes, but writing them up in linear research accounts (WILLIS, 2010). I argue that these discussions are insufficient in covering the challenges that researchers face, as time affects many phases in doing organizational ethnography. Throughout this article, I will discuss the different ways in which time and temporality influence the research process and add to the sparse literature on the relationship between time and ethnography. I suggest that the growing interest of organizational scholars in time and temporality emphasizes the need for more methodological discussions, rather than simply abandoning these in the black box of doing organizational studies. [2]

One of the few organization scholars writing about the relationship between time and ethnography is Patrick DAWSON (2014a, 2014b). He proposes a framework consisting of three concepts: 1. temporal awareness; 2. temporal practices; and 3. temporal merging (2014b). His suggestions focus on the ethnographer and her attitude towards the studied phenomenon:

"Temporal merging in being able to accommodate the intertwining of objective and subjective time, temporal practices in being able to use different concepts of time without trying to resolve them during the collection and analyses of data, and temporal awareness in being able to accept the paradox of time in the use of a relational-temporal perspective, all open up opportunities for greater insight and understanding in engaging in ethnographic studies on changing organizations" (p.148). [3]

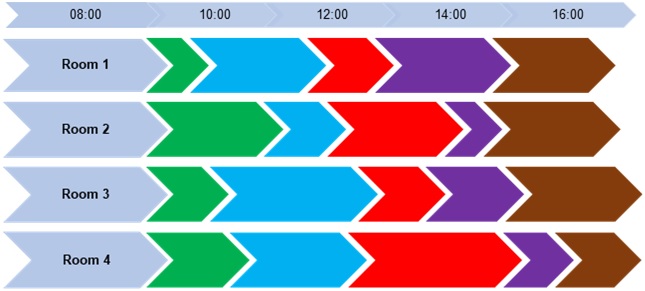

For DAWSON, the interweaving of objective and subjective concepts of time occurs in interviewees' stories about organizational change, for example, when they talk about both scheduled events and their personal and fluid experiences of time. The objective for the researcher is to represent both perspectives in ethnographic writing and explain how they coexist and contradict each other. Even though his framework mainly concerns the representational side of the research process, his concepts hold potential for thinking about temporality in ethnographic studies. Temporal awareness means accepting the paradox of time —that researchers often present change processes as linear and staged, but that they are experienced as emergent and chaotic by the participants. Undertaking temporal practices describes a research objective to use different concepts without resolving them, maintaining a variety of organizational time and temporality themes in the analysis. For example, researchers using concepts related to measured clock time as well as subjective time, e.g., that the interviewee experienced a specific period as fast or slow. Ethnographers should conduct temporal merging by focusing on intertwining objective and subjective time perspectives in organizational ethnographies, primarily concerning the re-storying of change processes. My aim is to develop DAWSON's framework, applying it to other aspects of doing ethnography, thus considering qualitative methods and their suitability in capturing temporal modes, and the significance of different conceptualizations of time and temporality for understanding organizations. In order to do so, I draw upon an ethnographic study of a newly established cardiac day unit in a Danish hospital. [4]

Typically, ethnographers conducting studies in health care have focused on a specific type of organizing, which embodies many different representations of time (GLASER & STRAUSS, 1968; ZERUBAVEL, 1979). Professional struggles to deal with illnesses and patients create temporal tensions that serve as illustrations for other kinds of organizations, e.g., the temporal space of illness (MOREIRA, 2007). I contribute to these studies and develop a framework for engaging with time and temporality in multiple ways during the ethnographic research process. Therefore, the research question that I aspire to answer in this article is: what are the organizational tempography implications of researching the coexistence of multiple time perspectives in a cardiac day unit? [5]

Accordingly, I argue that researchers who conduct tempographic studies need to consider how they understand time. To this end, I provide a mini-review in Section 2 of different theoretical perspectives on time and temporality in organizations. How researchers see time in different kinds of qualitative ethnographic data is the pivotal point of Section 3, in which I also describe the research methods, types of data and thematic analysis applied in my tempography. In Section 4, I present the empirical case. In Section 5, I provide examples of how to represent time using examples from the cardiac day unit—as time objects, temporal work and patient trajectories. In Section 6, I discuss how ethnographers are supposed to think about time by considering methodological temporal awareness, analytical temporal practices and multi-temporal merging. To conclude, in Section 7, I summarize my contribution to methodological discussions about the role played by time and temporality in the ethnographic research process. [6]

2. Theoretical Analysis of Time and Temporality in the Study

In this section, I discuss the relationship between temporality and organizational ethnography with suggestions for how to engage in analytical practices using different temporal concepts (DAWSON, 2014b). Thus, there follows a brief literature review, in which I provide examples of how scholars understand time. Researchers' understanding of the organization is shaped by the time perspective they apply to understand it. When focusing on the relationship between discourse and time (JENSEN, 2007; KOZIN, 2007; WALL, 2007), organizing becomes a matter of language evolving and representing time. When investigating socio-temporal structures (ZERUBAVEL, 1979) scholars tend to reduce organizations to collections of more or less solid orders and materials. Concentrating on practices (KAPLAN & ORLIKOWSKI, 2013; ORLIKOWSKI & YATES, 2002) makes organizational life a matter of planning and strategizing. In addition, making temporal processes the central point of research provides a focus on large-scale change processes (SCHULTZ & HERNES, 2012). In this article, I argue for coexisting time perspectives in organizations. Researchers (ADAM, 1995, 1998; NOWOTNY, 1994; WATERWORTH, 2003, 2017) have previously approached multi-temporality, but rarely from a practice-oriented perspective, which is the lens I use here. [7]

In the next three sections, I present different theoretical perspectives that form the analytical framework for understanding how time and temporality affect professional practice. My objective is to show that these analytical perspectives are the basis for engaging in temporal practices and temporal merging in the tempography of the cardiac day unit. [8]

The importance of objects of time has attracted a great deal of attention from both organization scholars (ZERUBAVEL, 1985) and within broader sociological research (BIRTH, 2012). Researchers have even characterized the relationship between objects and the human experience of time as technological acceleration, where new information technologies elevate the speed at which activity is performed (ROSA, 2013). Time objects are social structures and used by organizational members for a variety of purposes, including the coordination of actions, to facilitate collaboration and to bridge different professional attitudes towards time (YAKURA, 2002). On a very basic level, time objects become necessary even to think about time, with clocks and calendars as the classic examples (BIRTH, 2012). A central feature of time objects is that they are designed to convey specific ways of thinking about time, e.g., the clock conveying clock time and the calendar conveying event time. In a hospital context, clocks, schedules, plans and charts coexist in the ongoing care of patients and continuous coverage, which, according to ZERUBAVEL (1979), is the overall organizational principle. The patient record (which is also mentioned by ZERUBAVEL) is an example of an object that is designed to convey a specific kind of temporality, namely, the patient's story, significant events, preoccupations for future illness prospects etc., i.e., patient time. [9]

When organizational members utilize objects of time (such as schedules and project plans), they engage in practices which are crucial for the coordination, coherence and realization of organizational goals. Accordingly, temporal work has been a central theme in organization studies (KAPLAN & ORLIKOWSKI, 2013; McGIVERN et al., 2018; REINECKE & ANSARI, 2015). Temporal work is a concept that covers how actors discuss differences in their interpretations of the organization's past and present to construct a basis for future strategic plans and actions. The perspective has been popular in studies of strategy projects (KAPLAN & ORLIKOWSKI, 2013), sometimes with the additional focus on the use of boundary objects as facilitators of strategic processes (McGIVERN et al., 2018). As in strategy processes, professionals in hospitals constantly debate interpretations of specific patients and their symptoms in order to make decisions on medical plans and actions. They are continually undertaking small-scale strategy work to balance bed-management, patients' needs, procedure plans and unexpected situations. Engaging in this kind of professional practice is, in its nature, very much about temporality, moving back and forth between past, present and future. [10]

A trajectory is a specific process unfolding over time. The concept has been used by scholars to describe organizational processes: professional careers (SCHILLING, 2015); discovery trajectories (TIMMERMANS, 1999); and the management of patient experiences (STRAUSS, FAGERHAUGH, SUCZEK & WIENER, 1997). A trajectory is an organizational narrative, a series of events taking place over time (e.g., an organizational change process) or a personal experience that forms a specific story (e.g., an illness story). In organizations, the multiple trajectories of professionals cross each other (TIMMERMANS, 1998). Recently, process scholars have taken up the trajectory concept as well. HERNES (2017) suggests the temporal trajectory as the object of thinking, i.e., a form of organizational entity, which actors are constantly contesting and reconstructing. In classical health care studies, researchers have mainly used the trajectory concept to describe the social organization of hospital work from diagnosis to recovery or the possible death of the patient (STRAUSS et al., 1997). The concept is frequently invoked with reference to treatment of chronic diseases such as cancer, ischemic heart disease and heart failure. It has been used by scholars to analyze professionals' considerations of how the disease will evolve, how the patient experiences the process and how the transdisciplinary work along the trajectory is to be organized. [11]

In sum, organizational scholars have discussed time and temporality in many ways. Each of these time perspectives is important for understanding how organizations function and what they are, with a specific focus here on health care. In this article, I therefore argue that there is a need for studying how different understandings of time coexist in organizational life, an approach which I adopted for a tempography of a cardiac day unit. [12]

In this section, I explore how ethnographers see time when doing tempography using qualitative methods. It is important to highlight that "seeing" should not be understood as a realist objective—rather it is a concept describing how ethnographers are able to tap into diverse temporal modes by using different methods. [13]

In the ethnographic case study of the cardiac day unit, I focused on in-situ actions, conversations and accounts (ATKINSON & HAMMERSLEY, 1994; HAMMERSLEY & ATKINSON, 2007). I was primarily concerned with exploring day-to-day practices, making the study a subcategory of organizational ethnography (PEDERSEN & HUMLE, 2016), as it investigates the role of time and temporality for organizing. Several classical ethnographic studies have been conducted with time as a central research theme, usually emerging from a grounded theory approach (BARLEY, 1988; BIRTH, 2012; DAWSON, 2014b; GLASER & STRAUSS, 1968; STRAUSS et al., 1997; WILLIS, 2010). In this research project, I moved away from the grounded theory approach to tempography, advocating a more deliberate and theoretically informed methodology. It is important to note that this does not require settling for a specific theoretical time perspective, but rather having a research interest in time and temporality as broadly defined categories from the beginning, i.e., taking time as a key organizational principle (although often tacit and implicit) and bringing it to the forefront. For example, I initially focused on temporal practices, but the significance of patient trajectories and time objects developed as research topics throughout the study, as they were constantly debated and consulted by professionals in their daily planning. [14]

As my study progressed, a parallel objective became to discuss how different kinds of qualitative data relate to time and temporality, highlighting attention points for researchers wishing to engage in tempography. I finalized the ethnographic study between January 2015 and May 2017 (see Figure 1 for an overview). The data sources consisted of interviews, recorded meetings and field notes produced while I shadowed (CZARNIAWSKA, 2007) professionals and patients in the day unit. Shadowing, as an ethnographic method, concerns the researchers' choice to follow participants in their daily lives in order to understand their practices, and engage in conversations about their thoughts and actions. In this specific study, I followed professionals with the objective of understanding how their work tasks were performed, specifically with regards to planning and engaging in professional discussions, whereas the objective in following patients was to participate in informal conversations about their experiences.

Figure 1: Overview of ethnographic study [15]

I produced different types of data in the study (see Figure 1). From field notes as well as transcribed interviews and meetings, I obtained a range of insights into how professionals and patients experience and handle the temporal tensions arising from the introduction of same-day discharge. Patient narratives (PEDERSEN, 2009; PEDERSEN & JOHANSEN, 2012) form (more or less) linear stories connecting past, present and future, and in this way there is an inherent temporal aspect to collecting and studying narratives. In the day unit, I saw narratives appearing in two ways: 1. in interviews, and 2. in observed conversations between patients and professionals. Another data source is the observational accounts of practices (ATKINSON & HAMMERSLEY, 1994; CZARNIAWSKA, 2007; JARZABKOWSKI, BEDNAREK & LÊ, 2014). An observational excerpt forms another kind of story explicitly constructed by the researcher, who usually writes it up in a linear micro-account. Organizational practices often take place at a certain time and place, and some of them have a clear temporal quality, e.g., a process of making decisions that invokes past, present and future concerns. Depictions of objects in use (ORLIKOWSKI, 2000, 2007; ORLIKOWSKI & SCOTT, 2008) are snapshots frozen in time, yet still allowing the ethnographer to show how objects represent time and temporality, and how they are utilized in practice. For example, it is difficult for researchers to show how objects are constantly adapted by professionals by presenting depictions of project plans and schedules. However, the combination of depictions together with observational accounts provide interesting data on the role that these objects play. The different temporalities in ethnographic data are not easily separable because they coexist and affect each other continuously, as I will examine in greater detail in the analysis section of this article. [16]

After the fieldwork period ended, I conducted a thematic analysis (TA) of transcripts and field notes (CLARKE, BRAUN & HAYFIELD, 2015). The TA approach I adopted in this research project is a Big Q approach, as defined by CLARKE et al., i.e., an analytical attitude rejecting universal meaning, but emphasizing contextual knowledge. When following the TA process, researchers have to move through six analytical steps or phases: 1. familiarization; 2. coding; 3. searching for themes; 4. reviewing themes; 5. defining and naming themes; and 6. writing the report (p.230). I will highlight three of the most important steps in this process. I familiarized myself with the ethnographic data (Step 1), both during and after the fieldwork period ended, by reading and rereading transcripts and field notes while making basic analytical and reflective notes. Audio recordings were listened to, both in the transcription process and outside of this process. I undertook the coding process (Step 2) with an open thematic approach related to the research question, i.e., how did time (as a broad concept) appear in the data, e.g., as people talking explicitly about time pressure, about past times or planning for the future? When reviewing the themes (Step 3) I identified the most coherent and dense aspects of the data that told me something about the RQ, resulting in three analytical themes and later their theoretical representations (see Table 1).

|

Empirical example |

Analytical theme |

Theoretical concept |

|

"The nurses face the monitor displaying an overview of patients and consider what the status is. They are wondering why so few patients have been discharged. Has the staff in the procedure room been especially slow today?" (Field note, November 18, 2015) |

Material objects are central for scheduling |

Objects of time |

|

"A doctor reviews the background for a randomized controlled trial, as well as methods and conclusions. He then asks: 'Based on this study, what should we do with our guidelines?' Then they discuss what the implications should be for their treatment of patients in the future" (Field note, September 8, 2015). |

Decisions spans past, present and future |

Temporal work |

|

"... we have been trying to map out what the patient's trajectory through the day unit system was ... we did not really have a good overview of what the patients were told when they had the initial meeting in the ambulatory clinic ... so we used a lot of time to map this process" (Interview, doctor). |

Trajectories are essential for organizing |

Patient trajectories |

Table 1: Analytical themes [17]

I could not include all themes that emerged from the thematic analysis, e.g., the relationship between time and space—because of either lack of data density, or a weaker relevance for the research question. The three analytical themes constitute different theoretical perspectives on same-day discharge, highlighting a need for methodological implications and considerations. [18]

A key contribution from organizational tempography as a specific approach is that it brings theoretically informed concepts to the table (bringing back theory as suggested by PEDERSEN & HUMLE, 2016). These tend to be overlooked by ethnographers studying organizations, in that they mainly produce studies of time within an organizational context, rather than studying how different theoretical time concepts create organizations (BERGMAN, 2003). Accordingly, in the next section I describe the specific temporal organization in this research study—the cardiac day unit. [19]

4. Introducing Same-Day Discharge in a Cardiac Day Unit

The cardiac day unit was established in 2015 in a Danish hospital and received patients for planned or subacute procedures within two medical areas—arrhythmic and ischemic heart disease—who could be discharged to their own homes or transferred to other hospitals on the same day as the procedure. The common denominator for the admitted patients was that their trajectories were similar, i.e., short and relatively uncomplicated, rather than a shared diagnosis. When doing ethnographic fieldwork, I quickly became familiar with the daily routines and discovered how a number of planning tools, patient records and protocols supported professional work. Planning of medical procedures took place via an IT system that showed procedures (minor interventions) and operations, which were scheduled for many weeks at a time. The procedures were booked by employees in the cardiac clinic's visitation office on the basis of references from specialist doctors or from departments at other hospitals. The wall in the nursing office displayed a digital monitor, which showed an overview of planned procedures, i.e., the procedure plan. Next to this was another monitor with a patient overview—a simple table list of patients distributed to beds and rooms. The patient overview played a supporting role in the work of professionals as it reminded them of times, planned tests, attendance, and contained information about the patient's general health and specific illness. Patient records were used continuously by the staff to orient themselves using notes about history of illness etc. This record was constructed a few days before the procedure, where the patient would meet with a doctor and a nurse in the ambulatory clinic. [20]

During the initial phase of the study in May 2015, there were difficulties with accomplishing same-day discharge, which brought my attention to the tensions arising from the introduction of a shorter timeframe. At this time, the management team looked for bottlenecks and chaotic processes, and interviewed patients about their experiences. Most of the patients were very satisfied with their treatment and complemented the fast, efficient and competent care they received. However, during this period there were many discussions between professionals on where to put patients who did not fit the new discharge scheme. Planning was also complicated because of increased pressure on the different sections. This pressure travelled from section to section, e.g., if spaces were occupied in the intensive care unit it resulted in very sick patients remaining hospitalized in the emergency section, i.e., an organizational knock-on effect. This made the implementation difficult because patients who were to be moved elsewhere, in order to close the day unit during the night, put additional pressure on the other sections. It became clear that the establishment of a specialized unit with same-day discharge involved changes to deeply routinized work tasks, and was not just a case of performing tasks within a shorter timeframe. However, it was apparent that many of the difficulties related to planning, managing competing systems and synchronization between different departments, and to how patients and their trajectories were handled by professionals. [21]

5. Empirical Illustrations of Time in a Cardiac Day Unit

In this section, I provide analytical excerpts from my data that illustrate the different representations of time in the tempography of the cardiac day unit in three ways: 1. as professionals utilizing objects of time; 2. as professionals engaging in temporal work; and 3. as trajectories that are continuously reconstructed by patients and professionals. I present short empirical illustrations and not fully developed analyses, since my main aim is to show how different analytical time perspectives are connected to ethnographic methods. The excerpts are from observations and interviews that I conducted in the research process. All excerpts have been anonymized and identifying information has been removed or significantly altered. [22]

5.1 Procedure plans as objects of time

In the cardiac day unit, a monitor hangs on the wall of the nursing office, which shows the procedure plan for the specific day. The overview displays patient names, a heading that describes the scheduled procedure and their allocation to a specific procedure room ("Room" in Figure 2). Professionals can watch the real-time unfolding of events in each room, where a vertical line marks the current time and the colors indicate the phases of the procedure, e.g., green for preparation, red for knife-time (when surgery is performed) and brown for completion. The professionals utilize this plan to coordinate work activities in relation to each patient by reading the changes in color. When should the next patient be prepared for procedure, when will the patient return, are there any delays or have acute patients arrived? When the nurses look at the board, they can decode the trajectory for each patient by looking at the allotted colors on screen.

Figure 2: Depiction of procedure plan [23]

The procedure plan is a central work object in the nursing office, which I present in this interview quote from a nurse:

"... we are very much focused on the procedure plan—that it proceeds as it should. Because if it does not proceed, then it is us who must go in and explain to the patients: 'there are delays'" (Interview, nurse). [24]

The plan is consulted constantly and closely observed for unforeseen changes. If acute patients arrive, they appear as dark blue bars, indicating that they need to be squeezed into the schedule. I provide in the following field note an example of such a change and how it is handled by professionals:

"It is 11 AM and a technician calls the nursing office and explains that the medical equipment in room no. 4 has broken down. Next, all the patients' names on the monitor become dark blue and the nurses know that this means that they will be moved to other rooms. It creates many problems for today's planning. The nurses discuss which patients can be canceled. They inform the waiting patients that 'things are looking bleak', but they are still waiting to see whether the procedures can occur during the day shift. We watch the development on the monitor throughout the day. The procedures are moved further and further into the afternoon, and suddenly two procedures have been moved to after 8 PM. A nurse explains that the staff would rather work over-time to complete a few more procedures than be behind with the plan for the rest of the week" (Field note, July 9, 2015). [25]

Thus, the professionals regard the overview board as a central time object for the overall planning, but it is also important for the nurses in managing patients' expectations. The monitor displays timeframes, which organize the professionals' suppositions for the forward-looking organization of the patient trajectories. In addition, the monitor can act as an object for ongoing negotiations and discussions of these expectations. Time objects in a hospital are many: some are particularly significant for organizing patient trajectories, and some objects have a more powerful status than others. In this account, the breakdown of equipment means a reduction of clock time that is visible on the monitor. What professionals need to do for the schedule to fit again involves rearrangements and disruption of several patient trajectories, i.e., patient time. The time objects play an important role in this reorganization of hospital work. The temporality of the professionals' workday is crafted into an object that inherits two temporalities, but eviscerates the logic of the patient trajectory in favor of clock time. When researching the significance of time objects in organizations, the researcher's focus unavoidably becomes how socio-material objects and orders shape organizational life. However, I would emphasize that the field note above also points to the importance of professional work in relation to these objects. I represent time in two ways in this analysis: one is the frozen depiction of the procedure plan, and the other is the observational account of this object in use. I show how these two representations together explains how the plan's design conveys a specific type of time (here clock time), which has consequences for professional practice. [26]

5.2 Dealing with postponements as temporal work

Sometimes patients cannot be discharged, due to complications (such as excessive bleeding), the postponement of procedures or other types of delays. At the end of each day shift, the head nurse makes a patient overview plan—a central document supporting the planning of work tasks distributed across the group of nurses in the day unit. I find that the centrality of the patient overview becomes clear in this observational account, where a technical error has led to the breakdown of the monitor displaying the overview board:

"They post handwritten notes directly on the monitor, but it quickly becomes unmanageable. The screen is still not working at eleven o' clock. The head nurse calls the technicians and speaks in no uncertain terms on the phone: 'You must come and fix it urgently. We cannot work!'" (Field note, September 15, 2016) [27]

Accordingly, whenever the overall plan for placing patients falls apart, it becomes the task of the professionals to discuss and adjust the layout of the patient overview board:

"At 14:30, the head nurse prepares the plan for tomorrow. The overview board looks very messy. There are too many patients for the number of beds, because some of them have not been discharged according to plan. The head nurse is also looking at the procedure plan, which looks completely packed. She makes some suggestions on how they can organize their way out of it, even though it looks quite hopeless. She says in an ironic tone: 'you really can't squeeze the turnip any more'? Another nurse answers: 'No because no matter what we do, we lack beds for three patients.' The nurses proceed to discuss which patients can wait in the hallway if necessary; what are their psychological needs, were they displaying unusual nervousness in the initial meeting in the ambulatory clinic? They decide that it will be those patients coming in for very short procedures" (Field note, November 17, 2015). [28]

With this excerpt, I provide an example of how professionals engage in micro-strategical temporal work in which they discuss the present difficulties and interpret how patients acted in the near past, as a basis for making the right decisions on how to move forward into the near future. What the patients told the professionals during a previous meeting in the ambulatory clinic is suddenly brought into the present and used to make decisions on where to physically place them. An interesting point here is that temporal work often takes place in relation to time objects (as detailed in the first analytical section). In this empirical example, I present how time objects, i.e., overview boards, plans and patient records, support the temporal work of professionals. Temporal work and time objects are connected, but represent two very different time perspectives, namely that temporal work concerns temporality (micro-strategic processes in relation to past, present and future) while time objects concern time (structures used to map time). The observational data that I constructed represents time as small linear accounts of professionals engaging in micro-strategic practices that span past, present and future concerns. [29]

5.3 Professional dilemmas in patient trajectories

It is often crucial for patients in the day unit to pass on their personal experiences to professionals who can manage their trajectories. Generally, their personal stories are central to the way they encounter the staff whilst being admitted. Professionals have to listen to them and their anxieties, as I present in this account where a patient is surprised by the prospects of having to go through surgery:

"'I am a little surprised that the effects of my previous surgery did not last longer. They say it lasts 20 years'. The patient hopes that she will only have to undergo a small procedure as it would be tough having invasive surgery again. The patient says, 'I just thought I could put it behind me'" (Field note, November 27, 2015). [30]

The patient's previous trajectory is characterized by problematic experiences (a lengthy recovery after invasive surgery), which she considers necessary to communicate to the professionals, as she identifies them as important events. I provide another example in the following excerpt from an initial meeting in the ambulatory clinic where the patient is frustrated about waiting time:

"'I've long expressed my concern that something was wrong with my heart, but no one listened to me'. The patient is generally tired of the health care sector and has experienced many cancellations. The doctor looks at me and says: 'please note that patient names often do not appear in the IT systems—there are obviously follow-up conversations that have not been completed because of the system.' The patient complains about the amount of waiting time: 'Why should I wait so long to come here? I have called several times and complained'. The patient is sad to experience that her health is deteriorating. The patient has many physical shortcomings and becomes exhausted quite easily. The patient tells us that she previously worked with harmful materials in her youth and therefore has problems with her lungs today. The doctor listens to her, receives information about her medicine, informs her about the planned procedure and says goodbye. The doctor makes a note in the patient's record, which summarizes the situation and the illness history. The doctor explains to me that it is specifically important to make these notes for patients in same-day schemes as the professionals encountering them have a short time to get an overview of the patient's situation" (Field note, September 15, 2016). [31]

In this conversation, the doctor translates the patient's narrative into notes so that the information can be brought to bear on her trajectory in the day unit. The doctor records (Table 2) the most central events in the patient's previous trajectory, which may be of major importance for the same-day trajectory. These explain her irritation towards the hospital, her bodily discomfort and describe prior illnesses that could (potentially) have consequences for her future treatment. The doctor also tries to direct the patient's dissatisfaction with the hospital towards a system error, thereby contesting the patient's experience of her trajectory. The preparation of patient records and the translation of information to notes are central components of working with patient trajectories, because these records provide information-sharing platforms that can be accessed by many different professionals in the future, thus following the patient through time.

|

Preliminary assessment |

The patient complains of chest pain. She expresses dissatisfaction with not having been admitted before now. The patient experiences pain on a daily basis and considers her physical capabilities to be severely impacted. She has previously worked with harmful materials and has impaired lung function. |

|

Allergies, CAVE |

None |

|

Note |

Pain following light physical exertion |

|

Procedure |

Coronary catheterization, possibly balloon angioplasty |

|

Treatment plan |

There are indications of possible occlusions because of chest pain. The patient is admitted in the day unit for catheterization on November 15. |

Table 2: Example of patient record (adapted for anonymization purposes with a different layout, diagnosis, type of procedure and scheduled dates) [32]

I find it interesting that patient trajectories are supported by time objects (e.g., the patient record) and temporal work, i.e., the work done by the doctor to make sense of the patient's past in order to make strategies for future treatment. However, I argue that patient trajectories are something more than professional work supported by objects, even though this has been the dominant way that they were described in organization studies. As I show in the above account, trajectories are constantly contested and reconstructed by professionals and patients. The patients' near past and prospects for the future are crucial to how trajectories are formed, perceived and handled in hospital departments, such as the cardiac day unit. Having organizational processes as the central point of research provides the researcher with an elaborate focus on change processes. Patient trajectories make for another kind of process, one which has been discussed in health care journals for many years, but has not been given much attention by organizational scholars. I represent time here with a linear patient narrative presented to the doctor, who translates it into a plan for future medical treatment. [33]

In the foregoing analytical sections, I have shown that different time perspectives coexist in the cardiac day unit. Objects representing time support temporal work practices and trajectories intersect with both objects and practices. Sometimes the time perspectives collide and create tensions, as in the relationship between patients' trajectories and the procedure plan, where professionals have to decide on which trajectories to disrupt in order to rearrange the design of the object. So where does this multiplicity of time and temporality perspectives leave the ethnographer? What questions will be specifically important for the ethnographer to explore when doing, and writing up, ethnographic studies concerning temporality in organizations? My contribution is the development of an approach capable of handling these problems, creating methodological temporal awareness through the introduction of a multiplicity of temporal modes in qualitative data, honoring analytical temporal practices by using different concepts and establishing multi-temporal merging by highlighting the coexistence of different temporalities in organizations. I shall discuss this framework in the next section. [34]

6. Temporal Awareness, Practices and Merging in Tempography

The existing body of literature on time and ethnography provides little guidance to researchers in determining the levels of temporal presence in qualitative studies. Accordingly, in this article, I argue for several ways that researchers need to consider the role of time in research processes. This is important especially with regards to recent developments in organization studies, where researchers not just investigate temporal structures (as per ZERUBAVEL, 1979), but also intertwining practices and processes. [35]

I find the problem of time in ethnography particularly prevalent when studying temporal practices and processes (linking past, present, future), and one way to resolve this tension is specifying how different time perspectives are linked together in accounts. Another possibility for handling the temporal paradox is to videotape the work of health care professionals and play it back to them when conducting interviews. Eileen WILLIS highlights this as enabling the interviewees to engage with the "other" (2010, p.556). Videotaping medical work can of course be ethically problematic, as the professionals constantly debate sensitive issues related to the patients. The problem of freezing research accounts will continue to be a problem for ethnographers and they therefore need to embrace the frozenness of their studies as "deep slices" (p.562) of practice at a particular moment in time. I chose to write up my case description (Section 4) in the past tense and to present the excerpts from my field notes in the analysis in the present tense. The purpose was to highlight the temporal tension between what I experienced in my research process and how field notes represent deep slices of a particular moment in time. [36]

Other than accepting that ethnographic accounts are deep slices, it is important for ethnographers to think about how research is designed in linear projects—even if they are designed to study the temporal and processual nature of organizational life. The researcher follows a planned and linear trajectory that comes to an end, while the behavior of organizational members is ongoing and forever changing. I constructed Section 4 in this article (the case description) as a linear account of what happened in the day unit. Even though this is problematized by researchers such as DAWSON (2014a, 2014b), researchers must ask themselves: how can a case description ever be written down as something other than a linear account, if it is to be understood by readers and reviewers? While organizational ethnographies could benefit from more experimental approaches, researchers cannot escape linearity completely, nor should they, as that is also an inherent temporal aspect of doing ethnographic research. The objective is not to dispose of any linearity, but to make sure that other temporal representations are included. [37]

In this regard, I find DAWSON's (2014b) framework useful, but my contribution is to push his points further—to explain yet more about the significance of time in organizations and what implications the explicit temporal focus entails for ethnographers. As an example of temporal awareness, DAWSON points out that the ethnographer spends extended periods of (chronological) time in the field, which enables them to spot key events. My contribution is to apply the need for awareness directly to the use of qualitative methods in ethnography, i.e., methodological temporal awareness. Researchers need to be aware of the temporal embeddedness of qualitative methods, i.e., that interviews tend to produce linear narratives, that observations of micro-strategic practices are constructed accounts of professionals engaging in temporal work, and that depictions of time objects are frozen in time. Accordingly, the methodological choices, that ethnographers make, have fundamental implications for what kind of analysis it is possible to undertake. [38]

Temporal practices for DAWSON relate to the researcher's skills—specifically the ability to hold onto (and present) diverse conceptions of time in the ethnography. However, I find that the notion of undertaking temporal practices as a researcher (i.e., using different concepts without resolving them), which refer to objective/subjective time, is a limited suggestion. Instead, I suggest that ethnographers engage in analytical temporal practices. This would entail that they utilize different concepts to analytically explain time and temporality in organizations, i.e., practices (temporal work), processes (patient trajectories) and structures (time objects). A way to perform analytical temporal practices is to consider how different conceptions of time lead to contradictions and difficulties in an organizational setting, as I highlighted in my analysis. By taking inspiration from the processual perspective (as I do with the trajectory concept), I was able to illustrate how the past and the future are brought together in the present by organizational actors and in this way stay open to diverse conceptions of time. I find it important to point out that the ethnographer's analytical choices create specific challenges for the representation of the study and the ability to merge different perspectives. [39]

When it comes to temporal merging, as in the last part of DAWSON's framework, I ask why it should be limited to the bridging of objective and subjective approaches in representations of sense-making processes? Considering the wider variety of time perspectives taken up in recent organization studies, I suggest that researchers pursue multi-temporal merging by explicitly laying out different time representations in ethnographic writing and showing empirically how they coexist. As an example, I point to the intersection between temporal work that occur in relation to time objects in the cardiac day unit, when professionals consult the procedure plan in order to make decisions that span past experiences, present concerns and future expectations. I argue that not only the merging of linear/processual perspectives is important, but also that of structure/process perspectives. My claim is that the explicit focus on bridging objective and subjective time perspectives leads researchers to the pitfall described by BIRTH (2012)—the human need for making temporalities into objects and risking the evisceration of their logics. I have tried to avoid that by showing the connection between time objects, temporal work and trajectories, but keeping them as separate concepts with different temporal representations. I suggest that researchers engage with multi-temporal merging and make sure to integrate different time perspectives, i.e., time as social structure and temporality, in organization studies and in organizational tempography in particular. [40]

I see a limitation of the tempographic approach because researchers need to engage with time in research processes in three different ways, i.e., how they understand, see and represent time—and they are all connected and sometimes difficult to separate. Objects are used by professionals in observational accounts (e.g., the procedure plan) and patient narratives are translated into depictions of objects (e.g., the patient record). Separating them could be considered a forced exercise for ethnographers. However, in order to be comprehensive, I argue that it is important to do so. In addition, methodological, theoretical and representational choices by the researcher are rarely (if ever) made in a specific successional order, especially when doing ethnography, where inductive approaches are imperative. However, my establishment of a tempographic framework will guide scholarly reflection on how to engage with time in research projects. [41]

Lastly, I argue that temporal awareness, practices and merging need to be considered, not only in relation to carrying out tempography, but also in how researchers understand organizations, i.e., as collections of intertwining temporal structures, practices and processes. In my study, I create temporal awareness by showing how time as a social structure and temporality coexist in the cardiac day unit. By presenting how different understandings of time coexist, I will make the field aware of multiple temporalities in same-day discharge and contribute to new explanations of why it sometimes proves difficult for hospitals (and organizations in general) to change work practices and establish new timeframes for completing them. [42]

In this article, I contribute to the ethnography literature by developing a framework for researchers interested in time and temporality in organizations, i.e., tempographers. I conclude that they need to engage with the problem of time in several stages of the research process. Firstly, they must do so in methodological temporal awareness, i.e., reflecting on how time becomes apparent in different kinds of qualitative data. This awareness enables them to consider the appropriateness of a specific method to investigate time-related issues, e.g., choosing narrative interviews for detailed descriptions of time experiences. Researchers also need to become accomplished in conducting analytical temporal practices, i.e., considering how they understand time through various conceptualizations, e.g., temporal work, time objects and patient trajectories. I suggest that conducting analytical temporal practices means making the implicit theories of time embedded in organization studies explicit, and elaborating on how these theories relate to the specific research project. Lastly, I argue for a broader perspective on temporal merging (multi-temporal merging), which means not just representing subjective/objective perspectives, but also portraying time as social structure/temporal process in perspectives of organizational life. [43]

The project was co-funded by the Department of Cardiology (Hjertemedicinsk Klinik) at Rigshospitalet. A special thanks to all professionals and patients that participated in the project.

Adam, Barbara (1995). Timewatch: The social analysis of time. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Adam, Barbara (1998). Timescapes of modernity: The environment and invisible hazards. London: Routledge.

Atkinson, Paul & Hammersley, Martyn (1994). Ethnography and participant observation. In Norman K. Denzin & Yvonna S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (pp.248-261). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Auyero, Javier & Swistun, Débora (2009). Tiresias in flammable shantytown: Toward a tempography of domination. Sociological Forum, 24(1), 1-21.

Barley, Stephen R. (1988). On technology, time, and social order: Technically induced change in the temporal organization of radiological work. In Frank A. Dubinskas (Ed.), Making time: Ethnographies of high-technology organizations (pp.123-169). Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

Bergman, Manfred M. (2003). Conference essay: The broad and the narrow in ethnography on organisations. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 4(1), Art. 23, http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-4.1.766 [Accessed: January 15, 2019].

Birth, Kevin K. (2012). Objects of time: How things shape temporality. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

Bobys, Richard S. (1980). Reviewed work(s): Patterns of time in hospital life: A sociological perspective by Eviatar Zerubavel. Social Forces, 59(2), 581-582.

Clarke, Victoria; Braun, Virginia & Hayfield, Nikki (2015). Thematic analysis. In Jonathan A. Smith (Ed.), Qualitative psychology: A practical guide to research methods (3rd ed., pp.222-248). London: Sage.

Czarniawska, Barbara (2007). Shadowing, and other techniques for doing fieldwork in modern societies. Copenhagen: Liber, Copenhagen Business School Press, Universitetsforlaget.

Dawson, Patrick (2014a). Reflections: On time, temporality and change in organizations. Journal of Change Management, 14(3), 285-308.

Dawson, Patrick (2014b). Temporal practices: Time and ethnographic research in changing organizations. Journal of Organizational Ethnography, 3(2), 130-151.

Fabian, Johannes (1983). Time and the other: How anthropology constructs its object. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

Glaser, Barney G. & Strauss, Anselm L. (1968). Time for dying. Chicago, IL: Aldine.

Hammersley, Martyn & Atkinson, Paul (2007). Ethnography: Principles in practice (3rd ed.). London: Taylor & Francis e-Library.

Harvey, Daina C. (2015). Waiting in the lower ninth ward in New Orleans: A case study of the tempography of hyper-marginalization. Symbolic Interaction, 38(4), 539-556.

Hernes, Tor (2017). Process as the becoming of temporal trajectory. In Ann Langley & Haridimos Tsoukas (Eds.), The Sage handbook of process organization studies (pp.601-607). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Jarzabkowski, Paula; Bednarek, Rebecca & Lê, Jane K. (2014). Producing persuasive findings: Demystifying ethnographic textwork in strategy and organization research. Strategic Organization, 12(4), 274-287.

Jensen, Torben E. (2007). Witnessing the future. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 8(1), Art. 1, http://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-8.1.200 [Accessed: February 18, 2019].

Kaplan, Sarah & Orlikowski, Wanda J. (2013). Temporal work in strategy making. Organization Science, 24(4), 965-995.

Kozin, Alexander (2007). On making legal emergency: Law office at its most expeditious. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 8(1), Art. 12, http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-8.1.202 [Accessed: February 20, 2019].

McGivern, Gerry; Dopson, Sue; Ferlie, Ewan; Fischer, Michael; Fitzgerald, Louise; Ledger, Jean & Bennett, Chris (2018). The silent politics of temporal work: A case study of a management consultancy project to redesign public health care. Organization Studies, 39(8), 1007-1030.

Moreira, Tiago (2007). How to investigate the temporalities of health. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 8(1), Art. 13, http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-8.1.203 [Accessed: January 11, 2019].

Nowotny, Helga (1994). Time: The modern and postmodern experience. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Orlikowski, Wanda J. (2000). Using technology and constituting structures: A practice lens for studying technology in organizations. Organization Science, 11(4), 404-428.

Orlikowski, Wanda J. (2007). Sociomaterial practices: Exploring technology at work. Organization Studies, 28(9), 1435-1448.

Orlikowski, Wanda J. & Scott, Susan V. (2008). 10 Sociomateriality: Challenging the separation of technology, work and organization. The Academy of Management Annals, 2(1), 433-474.

Orlikowski, Wanda J. & Yates, JoAnne (2002). It's about time: Temporal structuring in organizations. Organization Science, 13(6), 684-700.

Pedersen, Anne R. (2009). Moving away from chronological time: Introducing the shadows of time and chronotopes as new understandings of "narrative time". Organization, 16(3), 389-406.

Pedersen, Anne R. & Humle, Didde M. (2016). Doing organizational ethnography: A focus on polyphonic ways of organizing. New York, NY: Routledge.

Pedersen, Anne R. & Johansen, Mette B. (2012). Strategic and everyday innovative narratives: Translating ideas into everyday life in organizations. Innovation Journal, 17(1), 2-19.

Reinecke, Juliane & Ansari, Shaz (2015). When times collide: Temporal brokerage at the intersection of markets and developments. Academy of Management Journal, 58(2), 618-648.

Rosa, Hartmut (2013). Social acceleration: A new theory of modernity. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

Schilling, Elisabeth (2015). "Success is satisfaction with what you have"? Biographical work-life balance of older female employees in public administration. Gender, Work and Organization, 22(5), 474-494.

Schultz, Majken & Hernes, Tor (2012). A temporal perspective on organizational identity. Organization Science, 24(1), 1-21.

Strauss, Anselm. L.; Fagerhaugh, Shizuko.; Suczek, Barbara & Wiener, Carolyn (1997). Social organization of medical work (2nd ed.). Piscataway, NJ: Transaction.

Timmermans, Stefan (1998). Mutual tuning of multiple trajectories. Symbolic Interaction, 21(4), 425-440.

Timmermans, Stefan (1999). Closed-chest cardiac massage: The emergence of a discovery trajectory. Science, Technology & Human Values, 24(2), 213-240.

Wall, Rosemary (2007). "Natural", "normal": Discourse and practice at St. Bartholomew's Hospital, London, and Addenbrooke's Hospital, Cambridge, 1880-1920. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 8(1), Art. 17, http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-8.1.208 [Accessed: February 20, 2019].

Waterworth, Susan (2003). Temporal reference frameworks and nurses' work organization. Time & Society, 12(1), 41-54.

Waterworth, Susan (2017). Time and change in health care. Leadership in Health Services, 30(4), 354-363.

Willis, Eileen M. (2010). The problem of time in ethnographic health care research. Qualitative Health Research, 20(4), 556-564.

Yakura, Elaine K. (2002). Charting time: Timelines as temporal boundary objects. Academy of Management Journal, 45(5), 956-970.

Zerubavel, Eviatar (1979). Patterns of time in hospital life: A sociological perspective. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Zerubavel, Eviatar (1985). Hidden rhythms: Schedules and calendars in social life. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Vibeke Kristine SCHELLER has a MA in working life studies and psychology from Roskilde University and a PhD in organization and management studies from Copenhagen Business School. She is currently working as a postdoctoral researcher at the Department of Organization, Copenhagen Business School. Her main research focuses are: Time, temporality and practice based research in public organizations.

Contact:

Vibeke Kristine Scheller

Department of organization

Copenhagen Business School

Kilevej 14a, 2000 Frederiksberg, Denmark

E-mail: vks.ioa@cbs.dk

Scheller, Vibeke Kristine (2020). Understanding, Seeing and Representing Time in Tempography [43 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 21(2), Art. 18, http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-21.2.3481.