Volume 23, No. 1, Art. 2 – January 2022

Multilingualism and Translanguaging in Migration Studies: Some Methodological Reflections

Tetiana Havlin

Abstract: Research in the field of international migration engage a multilingual frame. Multilingualism raises a question of knowledge and meaning transferability in diverse linguistic and cultural contexts. Migration studies focusing on the transnational settings require a reflective use of languages while confronting methodological challenges at all research stages. This notion is especially valid in the case of qualitative research oriented to capturing meaning which can be lost in translation. As the first objective, in this article I reflect on language use in the research conduct in general and in migration studies in particular. I address a set of methodological challenges connected to multilingualism during data gathering, processing, and interpretation. The second objective is to approach translanguaging as one of the features of multilingual practices and as an epiphenomenon of immigration and transnationalism. I rely on a research project on immigrant agency of immigrants from the former Soviet Union (FSU), arriving in Germany between 1990-2005. I exemplify how multilingualism can be utilized in empirical research, and how translanguaging helps to understand cross-cultural experiences.

Key words: migration studies; multilingualism; translanguaging; linguistic biography; researcher positionality; qualitative research; interview method; data processing; interpretation; Russian-speaking immigrants

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. A Multilingual Research Project

2.1 Designing research through the fieldwork

2.2 Discovering multilingualism through the fieldwork

3. Multilingualism and Translanguaging in Research

3.1 Multilingualism or why we should think about de-naturalizing language in research

3.2 Translanguaging or when language boundaries can be blurred

4. Researcher Positionality and Multilingual Research

4.1 More than a researcher or how to approach one's own positionality from the reflective lens

4.2 The fieldwork and beyond

4.2.1 Data gathering

4.2.2 Data processing

4.2.3 Data interpretation

5. Conclusion

Multilingualism as one of the important features of migration studies has been brought to public attention in the last decades (BACHMANN-MEDICK & KUGELE, 2018; GOITOM, 2019; STONE, GOMEZ, HOTZOGLOU & LIPNITSKY, 2005; TEMPLE & KOTERBA, 2009). It can be explained by the following conceptual developments in this field: the growing popularity of transnationalism (AMELINA, 2012; FAIST, 2004; GLICK SCHILLER, BASCH & SZANTON-BLANC, 1992) as well as a departure from the classic assimilation framework and conceptualization of neoassimilationism (ALBA & FONER, 2017). In contrast to the assimilation approach, neoassimilationism is more tolerant of ethnicized identities, multi-cultural practices, and institutions but "within an acceptance of the dominant language and institutional fabric of the host nation-state" (GLICK SCHILLER, 2007, p.57). These developments within migration studies reflect, first of all, individual and collective immigrant practices employing such explanatory frames as multiple belongings, cultural hybridity, and multilingual experiences. From the research standpoint, different languages are omnipresent throughout all stages: beginning from fieldwork preparations to data collection, further analysis, presentation, and dissemination of results. "Intertwining of language and knowledge transfer is not coincidental" (SCHITTENHELM, 2017, p.102);1) therefore, it requires careful and reflective examination. At the same time, a critical approach to knowledge production is hardly possible without reflecting on language use and language hierarchies. For instance, being preoccupied with transnationalism for decades, it is remarkable that translanguaging as a process of blurring boundaries between languages plays a somewhat marginal role in migration studies. Separating translanguaging from transnationalism is challenging since the latter involves multiple languages and languages in contact tend to mix (WEINREICH, 1979 [1953]). [1]

Relying on these developments, in this article I intend to address two questions connected to multilingual research and translanguaging practices unraveled by such research: 1. How can multilingualism be approached and instrumentalized in the research on international migration, specifically during data gathering, processing, and interpretation? 2. What are the methodological implications and explanatory potential that deal with multilingual practices such as translanguaging in cross-cultural contexts? Answers to these questions are intertwined, since they lie in the realm of the multilingual daily practices of those who are studied (interviewees) as well as multilingual daily and research practices of those who study (a researcher or a research group). The former and the latter develop certain strategies based on their linguistic biographies and migratory experiences. Yet, as will be discussed later, these multilingual strategies are not independent of language hierarchies. In fact, a contextual and spatial use of certain languages or translanguaging illustrates an imbedded awareness of these hierarchies. [2]

The article is organized as follows: In Section 2, I sketch a case of a multilingual research project in the field of migration studies, thematizing an interdependence between research design and language use. In Section 3, I depict the phenomenon of multilingualism in the broader scholarly context, providing explanations and unraveling hierarchies in language use. Additionally, in this Section, I ruminate on a need to de-naturalize language and its relevance to reflective knowledge production, including migration studies. Further, I analyze a phenomenon of translanguaging: In which contexts people are inclined to blur boundaries between languages and what it signifies for studying the language use of immigrants. In Section 4, I discuss researcher positionality from the perspective of linguistic biography and speculate how language proficiencies of a researcher impact the research design as well as propound certain sensitivities toward language use in the fieldwork and subsequent analysis. Furthermore, I examine a set of solutions for how to deal with the multilingual practices in data gathering, processing, and interpretation. In Section 5, I conclude the article with a brief overview and position this contribution in the broader discussion on multilingual and reflective knowledge production. [3]

2. A Multilingual Research Project

In this section I focus on a project which was shaped as a multilingual one in the course of fieldwork and data processing. Specifically, I rely on the empirical study "Immigrant Agency: A Case of Russian-Speaking Immigrants and Citizens in Germany” (HAVLIN, 2020). Though I could designate the study as interdisciplinary in the field of migration studies, my professional training in sociology presents a certain disciplinary bias expressed in the theoretical, methodological, and scholarly preferences. By means of transnational methodology, I employ an international comparative perspective toward the subject under investigation as, for instance, in overcoming methodological nationalism (AMELINA & FAIST, 2012). At the same time, I tend to select examples of empirical studies which either involve the project languages (i.e., Russian, German, English) or comparable contexts (e.g., Russian-speaking communities in Germany). [4]

In this study on Russian-speaking immigrants I investigated how migration and settling processes are experienced, presented, and interpreted from the viewpoints of the people moving to and residing for the longer period in the mid-sized German cities: analyzing immigrant agency within the frame of time (long-term) and space (an urban scale). The focus of the study was a wide range of former Soviet Union (FSU) immigrants informed from the flexible ethnic boundary-making perspective (WIMMER, 2008) who moved and settled in Germany during the period between 1990 and 2005. Initiating the study in 2012 enabled me to analyze retrospectively experiences and outcomes from seven to thirty years after the initial point of migration. How to instrumentalize and operationalize the term agency emerged as one of the research challenges (GIDDENS, 1984; HITLIN & ELDER, 2007; LATOUR, 1996). Another issue was connected to an understanding of immigrant agency considering individual, collective, and structural factors which would embrace the richness of immigratory experiences of transitioning, embedding, and transnational practices. In the course of the study, multilingual practices and contextuality of language use played a pivotal role in the daily life of the research subjects, which required methodological adjustment on my part. [5]

2.1 Designing research through the fieldwork

While constructing the theory of immigrant agency, I drew support from grounded theory methodology (GTM) (CORBIN & STRAUSS, 1990) and transnational methodology (AMELINA & FAIST, 2012; GLICK SCHILLER et al., 1992), using an interpretative approach for data analysis (GADAMER, 2000 [1996]; RICŒUR, 1976). GTM was valuable in terms of incorporating changeability in the open-method research design as well as constructing a data-generated and reality-based theory of immigrant agency (CORBIN & STRAUSS, 1990, p.419). In turn, transnationalism allowed me to incorporate a continuum of experiences as emigrants, immigrants, and transmigrants while navigating between nation-states or in cross-cultural interactions. [6]

In the study, I relied on a mixed method design which included the combination of an interview method (KVALE & BRINKMANN, 2009 [1996]), real time ethnography (EMERSON, FRETZ & SHAW, 2011), video method (BANKOVSKAYA, 2016; BATES, 2018), and digital ethnography (MURTHY 2008). This combination proved to be successful: applied methods not only interacted and strengthened each other but also influenced each other (KVALE & BRINKMANN, 2009 [1996], p.8). Throughout the fieldwork phases the sampling strategy can be described in terms of "progressive sampling" based on ongoing analysis and theory building (SCHITTENHELM, 2009, p.8). I conducted the project in the period between 2012-2020 primarily in two mid-sized German cities of Rhineland-Palatinate and North Rhine-Westphalia (Xcity and Ycity respectively). Three fieldwork phases of the data collection can be distinguished which were overlapping with adjustments of methods. The first phase included 22 individual semi-structured interviews (2012/13 in Xcity, 2014/15 in Ycity). As the analysis frame stemmed out of the interview analysis, I began to address specific units, cases, or questions which emerged out of the preliminary evaluation of the interviews but which needed additional efforts to find answers elsewhere. The second phase incorporated ethnography in combination with a video recording to study immigrant cultural associations (2012/14 in the Xcity, 2015/17 in the Ycity). The third phase (2019/20) consisted of digital ethnography of immigrant retail businesses and the creation of a dataset which generated a network of interconnected immigrant grocery businesses, called in the mundane use as Russian shops, for the period between 2014-2020 (n=249 Germany-wide and across Western Europe). [7]

The mixed method research design required qualitative and quantitative data analysis. I used Atlas.ti to code the textual data (transcripts, fieldwork diaries), for generating the key elements of immigrant agency, typology building, actor-network analysis. The interpretative approach enabled me to capture an interplay between languages, individuals, and reflexivity (GADAMER, 2000 [1996], p.7). Reflexivity was understood as rooted already in language applied via a speech act and a verbal expression (p.10) as, for instance, in the case of semi-structured interviews. At the same time, reflexivity was directed to understand transferability of meaning in the multilingual settings. Further, I used Excel to construct a dataset of businesses, perform some statistical calculations (distributions of gender, age, ownership form, urban scale, etc.) and to map the business clusters. Stemming from the video recording, the iconographic evidence was scripted for the chronological reconstruction and for the analysis of micro-situative actions with the sequence and schematic analysis (ABBOTT, 1995, see Section 4.2.3 for some detailed examples on visual data interpretation). [8]

In this article, I reflect primarily on conducting interviews while making some parallels to other applied methods and their outcomes. In comparison to other methods, an interview is a profoundly language-dependent method (KVALE & BRINKMANN, 2009 [1996]), especially if contrasted with a video method (BANKOVSKAYA, 2016) which allowed me to gather iconographic evidence and required an additional instrument of analysis (ABBOTT, 1995). Out of the 22 interviews, 16 were conducted with the immigrants from the first-generation aged between 40 and 59. Other six interviews involved so-called one and a half generation or those who co-migrated as dependent children between the ages of six and fourteen (in their 20s and 30s at the time of the interview). The interview sampling criteria included such parameters as their own migration experience during the examined period; self-identification as an FSU or Russian-speaking immigrant; residence duration in Germany from seven to thirty years in the selected cities. Despite some intergenerational comparisons, the first generation builds the core sample and is the focus of the further analysis. Most of the interviewees have a university degree or were working toward it at that moment. Though there was no attempt to ascertain or represent gender differences in the depiction of immigrant agency, the fact that there is a large share of female interviewees (n=16) undoubtedly affected the material elicited at least in the case of interviews. Previously I reflected on gender and migration elsewhere (HAVLIN, 2015). [9]

The interview structure covered but was not limited to the following topics: pre-migration and postmigration experiences such as decision-making and transition; social connections and networks including familiar relations; educational and professional activities; cultural and language competencies; daily routine and housing arrangements; ties to the place of settlement (i.e., community engagement); ties to the place of origin (visits, contacts, etc.); future orientations. On average interviews lasted around three hours with the shortest of one hour and the longest of eight hours in two sessions. Later I transcribed the interviews based on the transcription rules by ROSENTHAL (2018, p.84) and anonymized them, processed by means of Atlas.ti using the grounded theory techniques of open, axial, and selective coding procedures (CORBIN & STRAUSS, 1990, p.423). During the analysis I attempted to establish the overarching patterns across the interviews which contributed to an understanding of individual agency and provided a conceptual frame to reflect on structural, collective, and networking factors. [10]

The analysis of the individual interviews allowed me to generate the key elements of immigrant agency: identity formations, language use, and actions. These elements were tested through the ethnography of migrant cultural associations and migrant businesses which contributed to an understanding of immigrant collective agency, network formations, and community engagement in the two German mid-sized cities. As a result, I instrumentalized the theory of immigrant agency by means of identity frameworks as representative agency (mélange identities, multiple belongings), language use as expressive agency as well as migration-related and postmigration actions as operational agency ranging from the entrepreneurial to free time activities. [11]

2.2 Discovering multilingualism through the fieldwork

At the initial stages of the study, language played an instrumental role. While doing the research on FSU immigrants in Germany, fluency in Russian was my implicit criterion during the interview sampling. A commonsense assumption that Russian as a lingua franca is useful for conducting interviews with FSU immigrants proved to be insufficient. Since I offered a choice between Russian and German that implicit criterion was quickly overruled by those who preferred to have a conversation in German (as a rule, the interviewees of the one and a half generation) or by those who inclined to translanguaging between Russian and German. [12]

As I proceeded with my fieldwork, I realized that my initial approach had two main methodological limitations. The first one was related to using the description Russian-speaking which would overshadow the multilingual and multicultural experiences of these people. Moreover, while observing the efforts and struggles to acquire or preserve the relevant languages, it proved to be ineffective to think of this group from the monolingual perspective. What started as the Russian-speaking interviews promptly required me to include in the fieldwork my linguistic repertoire of German, Ukrainian, English, and translanguaging. I obviously benefited from my linguistic competencies, yet, at the same time I was restrained by it (more in Section 4.1). [13]

TLOSTANOVA (2012, p.139) used the terms "transcultural tricksterism" or "transcultural tricksters" to describe the multilingual and multicultural experiences, to refer to an ability to fit changing contextual expectations.2) On the one hand, these descriptions justified experiences and activities I observed during my fieldwork. On the other hand, it required me to act as a transcultural trickster to fit the fieldwork settings. The transcultural flexibility may employ also a restraining effect which KRISTEVA called the silence of polyglots: "[...] between two [or more] languages, your [foreigner's] realm is silence. By dint of saying things in various ways, one just as trite as the other, just as approximate, one ends up no longer saying them" (2002, p.275). Keeping in mind the transcultural tricksterism as well as paradoxical silence of polyglots allow us, the researchers, to capture the complexity of immigrant expressive abilities or inabilities in the multicultural and multilingual contexts. [14]

Another methodological limitation while dealing with this group was to depict them as immigrants. Later, reflecting on their naturalization practices, I saw it as my covert attempt to cement this group in the migratory categories. In doing so, I risked reproducing narrow thinking on the complex identity frameworks and multi-local belonging. While Russian-speaking and immigrants were useful descriptions, they were some of other valid accounts as bilingual or multilingual, naturalized citizens or citizens with multiple nationalities, for instance. The closer analysis highlighted these. The flexible ethnic boundary-making (WIMMER, 2007) and multilingual flexibility proved to be more suitable to describe the immigrant agency of FSU immigrants (including also so-called Spätaussiedler [ethnic German resettlers]) in Germany. [15]

Changeability in language use made me tackle the question of multilingualism and reflect on language hierarchies in my research conduct. This led to an idea of de-naturalizing language (Section 3.1). In the majority of the cases during my fieldwork, people were indeed fluent in Russian, yet it became a mundane practice for them to switch between Russian and German (or other languages in some cases), to incline to a varying degree of language interferences or to translanguaging in more familiar or informal contexts (Section 3.2). Understanding these peculiarities of the multilingual and cross-cultural communication raised another question about translanguaging patterns. Further, I attempted to assess to what extent my linguistic biography enabled me to understand multilingual daily experiences of the researched group (Section 4.1). As a result of this heuristic process, I strove to advance a set of reflections on how to navigate multiple languages during the research conduct, specifically during data gathering, processing, and interpretation (Section 4.2). These reflections rely on a body of literature that guided my search as well as my own project to exemplify some points. [16]

One thing became certain: The multilingualism of my fieldwork shaped the research outcomes of the project. Such a stance allowed me to approach Russian-speaking immigrants through the plurality of their cultural and linguistic experiences during free time and business activities. Whereas Russian may play a role of lingua franca across this vast immigrant population, German is significant in the communication with the larger country's population but also with the offspring. In turn, translanguaging of Russian and German belonged to informal or familiar contexts, in the communication with other co-migrants or their children. Hence, the simultaneity hypothesis that assumes a compatibility of transnational and integration patterns (FAIST, 2000; FALICOV, 2005; LEVITT & GLICK SCHILLER, 2008) has proven valuable while analyzing this group. In the realm of language use this hypothesis reflects on the compatibility of multilingual orientations or deliberate everyday multilingualism. In the given case, it is striving for German proficiency, which is considered as a sign of integration and preserving the use of Russian as a feature of transnational practices. On the other hand, translanguaging creates the specific semantic field involving those who are able to decode the meaning constructed and generated in the moment. As, for instance, it was while assessing the meaning of Russaki [Russian-speaking immigrants in Germany], Termin [an appointment-arranged daily routine] or Kirche [referring to the protestant church] in the flow of the Russian conversations.3) [17]

In what follows I seek to address the methodological challenges which I faced during my project in terms of multilingualism and how to integrate it in the research strategy deliberately. I also consider what are the broader methodological implications of multilingualism and translanguaging, of reflexive language use in research and knowledge production. More details are provided on how they were addressed in the example of the outlined study. At the same time the more general question is posed: What potentials and problems do reflexive language use and multilingualism present in conducting research? [18]

3. Multilingualism and Translanguaging in Research

In Section 3, I investigate how academic conduct presents multilingualism and reflect on hierarchies related to language. I introduce some thoughts on de-naturalizing language in Section 3.1, whereas in Section 3.2 I look at translanguaging as an expression of the multilingual practices. Analyzing these practices allows me to unravel existing hierarchies of language use embedded in the daily practices of a researcher as well as research subjects. At the same time, blurring languages’ boundaries points to languaging as communication in action with its contextual and spatial manifestations. These manifestations are not necessarily compliant to the standard language or grammar-book rules, yet are directed by a set of factors influencing them. [19]

3.1 Multilingualism or why we should think about de-naturalizing language in research

The interest toward multilingualism and transferability between languages has been increasing lately. On the one hand, some critical voices are emerging across disciplines pointing out the discrepancies between research multilingual practices and monolingual dissemination (TIETZE, 2018), reflecting on translation, cross-cultural and translanguaging phenomena (CRANE, LOMBARD & TENZ, 2009). Some of these critical voices appear from the disciplines which are not primarily preoccupied with language as the core research focus but rather use language to gain or accumulate data and knowledge. The strong dependence of social science on language as a means of knowledge production requires per se mastering the linguistic expression and the critical awareness of social construction of languages. Managing the language-dependence of social science and transferability between languages have become paramount especially considering the gradual shift toward English dominance in the academic hierarchy worldwide (GORDIN, 2015). On the other hand, qualitative methodology requires the reflective analysis of language use (BARROS, 2020; ROTH, 2013; SCHITTENHELM, 2017; TAROZZI, 2013; TEMPLE, EDWARDS & ALEXANDER, 2006). Though extensively present in qualitative research, raising language awareness has not spared, for instance, quantitative (e.g., HANNA, HUNT & BHOPAL, 2008) or mixed method methodologies (e.g., HANTRAIS, 2005). [20]

Considering these developments, it is legitimate for us to ask: Why does this growing awareness of language use take place across disciplines? And why is it specifically addressed in qualitative research? To begin with: critical epistemologies (postcolonial, feminist, intersectional to name a few) have brought to the fore an ethical claim to review a status quo of knowledge production (AMELINA, BOATCĂ, BONGAERTS & WEIß, 2020; COLLYER, 2018; KNORR-CETINA & HARRÉ, 1981; TLOSTANOVA, 2015). Among other things that includes questioning language which is understood as a multi-purposeful research medium, yet as a "non-neutral" research tool (TAROZZI, 2013, §5). Another explanation connects to researcher positionality as an essential element of the research making in qualitative research. A self-reflective turn, a call for accountability and for a greater effort in self-analysis have been undermining an objective position of the researcher. Thus, researchers' subjectivities and experiences during the off-research time are perceived as an integral part of research conduct (BREUER, 2003; CREAN, 2018; TONA, 2006). Scrutinizing the researcher positionality and auto-ethnography are some of the solutions to keep researchers accountable for the knowledge they produce (AMELINA & FAIST, 2012; BRAIDOTTI & REGAN, 2017; KHOSRAVI, 2010). Later I address researcher positionality from the perspective of the linguistic biography, the cross-cultural experience, and multi-local orientations (Section 4.1). [21]

From the positionality standpoint, answering questions about what, by whom, how, by what means are substantial for the reflective knowledge production. Moreover, unreflective language use while studying social processes run the danger of reproducing the systems of domination which languages carry within them: a standard language versus an informal language (a dialect, translanguaging); a written language over a spoken one; an educated versus a naïve language;4) scientific versus mundane; a dominant language versus a subaltern one; verbal versus non-verbal. Acknowledging and dismantling these hierarchies while dealing with multiple languages means also to de-naturalize languages. For this reason, I address some hierarchies which have methodological relevance. [22]

To begin with, there is a contrast between dominant and subaltern languages. In depicting "hierarchical differentiation lines," LUTZ (2017, p.27) listed some binarities relevant for migration and gender studies: The West is prioritized over the rest, national over transnational, a majority group over minorities, men over women, a dominant language over minority languages. Following this logic, some examples would be: an accustomed language versus a gender-sensitive language; a majority language versus an immigrant language. The latter is of relevance, especially if we talk about translanguaging (more in Section 3.2). [23]

Connected to the previous dichotomy is a standard language versus its deviating, non-standard varieties. In terms of BOURDIEU, a standard language as an official language is "bound up with the state, both in its genesis and in its social uses" (2003 [1992], p.45). And as such it expresses symbolic power. This power can manifest in weaponizing language through censorship, propaganda, and disinformation which are mirrored in the mundane discourse (PASCALE, 2019, p.900). Additionally, deviations from a standard language can reveal certain class, regional, or ethnic positions. BERNSTEIN 2003 [1971] used the term sociolect to point out the structural components of language use: a combination of a class and language use. The regional linguistic nuances find their manifestations in dialects or regiolects (LEOPOLD, 2015 [1959]; SPIEKERMANN, TOPHINKE, VOGEL & WICH-REIF, 2016); whereas DIRIM and AUER (2004) depicted a combination of migration background and language as ethnolect. By the same token, translanguaging as a practical expression of multilingualism is a deviation from the standard language. [24]

A standard language as a language of education and science, as a state-promoted language opposes a mundane, naïve language use. The former inclines and continuously resists a temptation to tame or to improve a naïve language KOZLOVA & SANDOMIRSKAJA, 1996). Improvement strategies include proofreading, adjusting in accordance with grammatical, morphological and orthographic rules, polishing from undesired language interferences or just preserving accepted linguistic borrowings (e.g., an omnipresent trend to borrow from English into different languages). KOZLOVA and SANDOMIRSKAJA did an excellent study contrasting a standard (edited, educated) language with a naïve variety. The authors analyzed how editors chose an autobiographical narrative of a rural woman, who wrote her journal as she spoke, and turned it into the publishable text. In doing so, the actual biography of the woman disappeared: she had had a limited access to an education, and was illiterate for the majority of her life. Thus, the naïve writing contrasts to the sophisticated writing; the authors also captured the gap between an initial text and an edited text showing that editing can also be a form of violence, establishing the power relations between those who can master a word and those who are unable to. [25]

Another binary relation worth mentioning is verbal versus non-verbal languages. This binary is not exclusively connected to multilingualism but rather to the empirical study. In the interview-focused research, the analysis of the spoken prevails over the analysis of the unspoken. The former is transcribed and prepared for further examination; the latter plays a secondary role. Rarely can the unspoken (body language and gestures, emotions and reactions) be properly captured in a transcript; it requires an additional method, for instance, a video method (BATES, 2018) (see Section 4.2.3 for additional details). Engaging iconographic evidence serves as an attempt to mitigate the language dependence. And as such, it undermines the dominance of a verbal-to-text analysis, the "dominance of the text interpretation model" (BOHNSACK, 2003, p.241) in social science and in migration studies in particular. In the case of my project, this approach proved its effectiveness while studying immigrant agency of the free time (i.e., the hobby group cohesion and community engagement). In addition to the semi-structured interviews and ethnography, I used a video method to accumulate the iconographic evidence and the micro-situative-action and sequence analysis for its interpretation (HAVLIN, 2020, p.165). [26]

Highlighting these hierarchies and dichotomies means engaging the constructivist approach to language. The awareness of nuanced language use belongs to the process of de-naturalizing language as an objective, a "virtual and outside of time" system or as a code (RICŒUR, 1976, p.11). An attempt to de-naturalize language is comparable with earlier efforts to "de-naturalize ethnicity" (AMELINA & FAIST, 2012, p.1710) or to conceptualize a flexible ethnic boundary-making approach (WIMMER, 2007, pp.17-18). Therefore, de-naturalizing language is specifically important considering the fact that languages or dialects used to be assigned to ethnicities as one of the distinctive features. Not to overlook the link between a standard language and a nation state. Establishment and formalization of standard languages had been strongly intertwined with the nation-building processes and the rising power of nation-states during the 19th century and onwards (BOURDIEU, 2003 [1992]). To acknowledge this connection seems obvious in the light of the wide-spread critique of methodological nationalism (AMELINA, 2010; GLICK SCHILLER, 2007). Standard languages such as, for instance, English, Russian or German (the linguistic repertoire of my own research) can hardly be detached from political, economic, and social developments: first the imperial expansions and later the nation-building. Those processes had made them dominant among a wide range of other regional languages, spoken on the territory of current Germany, Russia, the UK, and beyond. Those processes granted them a status of lingua franca in their respective regions of influence or internationally (Section 2). [27]

The critical awareness of language hierarchies in knowledge production, mitigation of language dominance through a visual analysis and addressing multilingualism in its variety of expressions are some possible ways to de-naturalize languages. Some of these mechanisms I address further in Sections 4.2.1 to 4.2.3. The following subsection highlights the ways multilingualism manifests in the daily practices of the transnational and cross-cultural contexts, i.e., translanguaging and translingualism. [28]

3.2 Translanguaging or when language boundaries can be blurred

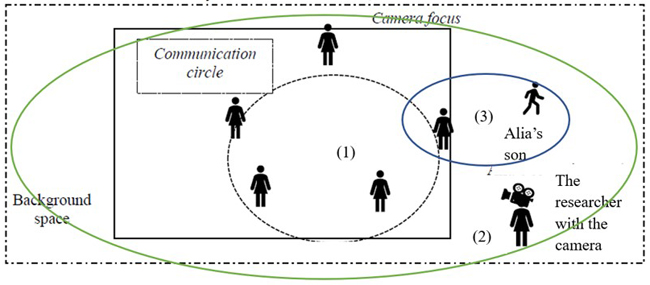

Translanguaging refers "to the multiple discursive practices in which multilingual speakers engage, as they draw on the resources within their communicative repertoires" (MARTIN-JONES, BLACKLEDGE & CREESE, 2012, p.10). While studying multilingual users, translanguaging incorporates or compares to such phenomena as code-switching, mixing languages, or language interference (AUER, 2003; BAKKER & MOUS, 1994; WEINREICH, 1979 [1953]). Translanguaging includes and, yet, exceeds them in depicting the language use in multilingual and transnational settings. The departure from language understanding as a code and the focus on translanguaging "calls into question the existence of 'languages' as identifiable, distinct systems" (MAZAK & HERBAS-DONOSO, 2014, p.699). It brings to our attention "no clear-cut boundaries between the 'languages' that people draw on" as they interact with each other (MARTIN-JONES et al., 2012, p.10). It points toward a need to think of the cross-language transferability, practically trespassing, or blurring boundaries between the standard languages. [29]

If languages are socially constructed, we have to scrutinize "communication in action" (p.11). This scrutiny may lead us to engage the translingual imagination not only in literature studies on multilingual authorship (KELLMAN, 2000) or in the context of higher education (MAZAK & CARROLL, 2016). Questioning communication in action highlights translanguaging in the daily practices of ordinary people in the transnational and multilingual contexts. The language is approached as an ongoing process, as languaging which "both shapes and is shaped by people" as they interact with each other (MAZAK & HERBAS-DONOSO, 2014, p.700). In these interactions people create and apply specific language depending on the situational use, actors involved, and institutionalization of the context. From the sociological standpoint, GIDDENS depicted the social construction of language as a social act, "the active, reflective character of human conduct" (1984, p.xvi). [30]

While dealing with the broader understanding of translingualism as a socio-linguistic phenomenon and translanguaging as an interactive process, we have to be aware of those factors which affect the occurrence of these practices. Cross-border mobility, shared language proficiencies of speakers, contextual and spatial frames, education and occupation predefine the linguistic choices and translanguaging patterns. While it is true that immigrants incline more to borrowing from the majority language of the host country into their original languages (WALTERMIRE, 2014; WEINREICH, 1979 [1953]), there is also some evidence that local or majority languages can be altered under the impact of (im)migration, technological advancement and increasing cross-cultural communication (LEOPOLD, 2015 [1959]; RODRÍGUEZ GONZÁLEZ, 2001). Specifically, the research by WEINREICH (1979 [1953]) and LEOPOLD (2015 [1959]) initially published approximately seven decades earlier illustrated a historical perspective on language interaction and on language transformations in Europe and in the USA under the impact of immigration. [31]

Shared bilingualism or multilingualism of the speakers is another factor (RESCH & ENZENHOFER, 2017; WEINREICH, 1979 [1953]). For instance, my fluency in Russian and German were essential for the interviewees to choose those or another language or to incline to translanguaging during the interviews. The following two examples illustrate that. In one case, I had an interview with Al,5) a PhD student at that time. His family was admitted into Germany in the early 1990s as Jewish refugees from Ukraine. Al was fluent in German, Russian, Ukrainian and English. Translanguaging between German and Russian emerged while talking about his migration experiences. Right away, Al asked if I spoke Ukrainian. As my reply was positive, occasionally he used Ukrainian to reflect on his pre-migration or postmigration stories related to Ukraine. Without even asking if I were English-fluent (perhaps, assuming that my university position would require it), Al added some English expressions to refer to his research and academic mobility in Germany and internationally. A contrasting example is an interview with Anoush, admitted as a Nagorno-Karabakh refugee from Armenia, who on a daily basis used German, Russian, and Armenian. While Armenian interferences never occurred during our interview, the German-Russian translanguaging was actively employed to reflect on her migratory experiences. [32]

Other factors defining language choices are connected to differentiation between the spheres (official, intimate, public, familiar) and the space of language use. In the case of multilingual speakers, language flexibility is wired into the cognitive mechanisms and depends on the social as well as spatial contexts (PURKARTHOFER, 2019). By the same token, it correlates with an understanding in which context a person can incline to translanguaging and in which it can be problematic. While talking about the context of language use, many from the sample admitted to restraining themselves from using Russian in public. This pattern emerged more frequently in the case of the one and a half generation who can blend in with their German native speaker fluency. This pattern can be explained by reluctance to expose certain cultural differences in public. Concealing proficiency in one language is not such an uncommon phenomenon, as WEINREICH described earlier experiences of Spanish-speaking immigrants in the US: "[...] who, to improve their relations with the 'Anglos' (English unilinguals), will even deny that they know Spanish" (1979 [1953], p.78). Though in a more recent study, VALDEÓN (2015) illustrated the growing confidence of speaking Spanish in public or private settings in the US. Increasing immigrant populations, openness to diversity, and normalization of transnational practices in migration-driven societies explain this change. One of the outcomes of this normalization in our case is the amount of young people who acknowledge the use of the Russian language in Germany. Thus, the Special Eurobarometer illustrates that approximately 9% of young people between ages 15 and 34 speak Russian as a mother tongue in Germany (EUROPEAN COMMISSION, 2012). [33]

An educational factor is also significant: those interviewees who were professionally trained in languages (i.e., a language teacher or a translator) differed in language attitudes from those with occupational training in other fields (also within higher education). The former group was more cautious and critical about translanguaging, paradoxically still inclining to it on a smaller scale. The latter paid less attention to the purity of the linguistic expressions or preserving the boundaries of one particular standard language, either Russian or German. With the varying degree of translanguaging in both groups, their daily reality had cross-cultural constellations expressed in their communication in action. [34]

What may seem as a random language mix has certain translanguaging patterns relevant for migration research. By means of an open, axial, and selective coding (CORBIN & STRAUSS, 1990), I analyzed which themes were covered in German. That allowed me to build five thematic clusters where the German interference emerged in a flow in the Russian interviews: 1. to relate to state agencies and institutions for bureaucratic matters, 2. to describe educational and requalification processes, 3. to reflect on labor-related issues such as a job search, job interviews, and occupational descriptions, 4. to refer to nonequivalent culture-bound concepts or German idiomatic expressions as in Schubladen denken [pigeon-hole thinking] or Zwickmühle [dilemma], 5. to describe specific social groups as Spätaussiedler [late ethnic German resettlers], Akademiker [university graduates], Sozialhilfeempfänger [receivers of social benefits] (HAVLIN, 2020, pp.123-126). Comparable patterns VALDEÓN (2015) observed in the study of the Spanish-speaking immigrants in the USA. Additionally, in their research on the language practices of FSU immigrants, ANSTATT and RUBCOV (2012) showed that the linguistic constellations within a family, the duration of stay, parental orientations and attitudes toward multilingualism as well as parental language proficiency contribute to how languages are used. [35]

Approaching language from the hierarchical perspective, multilingualism, and translanguaging reveals, on the one hand, the dilemma between the structural qualities of languages and the individual, familiar or communal use; on the other hand, interconnection between the researcher positionality and the interviewees' positionalities. Such approach illustrates also the social qualities of shared multilingualism and how it is engaged in the communication in action, finding expression among other things in translanguaging. Apart from how we assess multiculturalism or deal with language hierarchies, the positionality of a researcher plays a paramount role in research conduct, especially on such instrumental stages as data gathering, processing, and interpretation. [36]

4. Researcher Positionality and Multilingual Research

In this Section, I address researcher positionality from the standpoint of linguistic biographies, especially through the lens of the study presented in Section 2. Then I delve systematically into the multilingual practices and language hierarchies emerging during the fieldwork, during data processing, and interpretation. That is done while relying on my own research as well as benefiting from the extensive body of empirical studies in the field. [37]

4.1 More than a researcher or how to approach one's own positionality from the reflective lens

Looking at a researcher in the context of a specific project is basically to question how researcher positionality impacts knowledge production and how the researcher's background (cultural, linguistic, social) can be instrumentalized in the research (BREUER, 2003; CREAN, 2018; FEDYUK & ZENTAI, 2018; TONA, 2006). It means thinking about how the researcher's linguistic biography influences the language strategies at every stage of the research conduct or which avenues it opens for interpretation. Obviously, there is a significant difference whether it is an individual project (such as the qualification phases to acquire a PhD or a post-doctoral degree) or a collaborative project; what funds are allocated for the project, and the like. In the focus of the present methodological reflections is an individual post-doctoral project of a multilingual researcher. What started as an investigation into immigrant-centered perspectives on mobility and settlement of Russian-speaking immigrants illuminated methodological challenges of language use. For this reason, I aim at delving into the linguistic biography of the researcher while making sense of the sensibilities connected to languages. I answer the question: How has my linguistic biography shaped my research interest toward multilingualism and translanguaging? [38]

From an early age I was exposed to various languages. As I have moved along my individual, educational, and professional path, on different occasions it has included Russian, Ukrainian, English, Czech, Slovak, German, Italian; translanguaging of Ukrainian and Russian, of Czech, Slovak, and Ukrainian, of Russian and English. Additionally, I put some efforts into learning Japanese, French, and Spanish. This plethora of languages has been connected to people or familiar, intimate, professional contexts I have been involved in so far. As far back as I can remember myself, I have had continuous private lessons in Ukrainian, Russian, and later in English and German. Those attempts to master various languages were in contradiction as I thought to using Surzhyk (translanguaging of Ukrainian and Russian) in the daily communication with my family of origin. Though widely spoken in Ukraine, Surzhyk is associated with a lack of education, provincial life, and is frequently ridiculed. That is why how I spoke with my family and in my home-town was the subject of shame and secrecy as I progressed with my higher education in the regional metropole. During my university studies, to my astonishment, I discovered that there were actually some academic studies dedicated to Surzhyk (BERNSAND, 2001; DEL GAUDIO, 2015; MASENKO, 2019 [2011]). But it was not until the given research project that I started to question why translanguaging emerges in the first place and which factors foster or prevent it (see Section 3.2 for some explanations). [39]

As I started to conduct interviews, a few language-relevant questions emerged: Why do my interviewees incline to blend Russian with German (or occasionally English, or Ukrainian)? What does it have to do with my positionality? How does my linguistic biography overlap with the linguistic biographies of my interview partners? Later, it was interesting to test whether it was a random language mixing or if there were some patterns. Coming from the conventional sociological training, I was not equipped to deal with multilingualism or translanguaging. Though the empirical data highlighted the importance to look into the linguistic practices of people I interviewed and observed, it led to continuous reflection of my experiences with formal and informal languages. It made me also realize that the fact of speaking Surzhyk in my family had to do with growing up in Russian-Ukrainian hybrid spaces, having migration experiences within three generations across the Eurasian space, and relatives scattered across that area. Also, within my own core and extended family there are different modes of speaking with each other: Russian, Ukrainian, and Surzhyk; English, German, Italian, and occasional translanguaging. From this standpoint, it emerged that translanguaging had less to do with lacking education, and more with the customary habits, the transnational and spatial contexts. Similar experiences are reported by GRJASNOWA (2021) in her newly published book dedicated to the dangers of monolingualism and the power of the multilingualism in the cross-cultural contexts. [40]

Over time, I realized that my own linguistic biography—either the family-related or connected to my migratory experiences—made me incredibly sensitive to the context of language use, relevant hierarchies and prestige as well as inclinations to undermine those hierarchies or question their legitimacies. The latter has come significantly later. Such linguistic biography with a great deal of struggles, mistakes, and embarrassment has certainly made me more flexible in switching languages to pursue certain agendas, in blurring boundaries between languages if a situation required, or remaining within a certain standard language when needed. I must note that being skilled in Russian-Ukrainian translanguaging, during the interviews or in other contexts I found it challenging and tedious to maintain German-Russian translanguaging. This combination doesn't come as natural to me as does the former. [41]

So, how does this linguistic biography define me as a researcher? "An ironic transcultural trickster" as I would describe myself using the term of TLOSTANOVA (2012, p.133), whose scholarship has been dedicated to the postcolonial subjectivities on the post-Soviet space. In the earlier reflections, I made similar parallels with the people I encountered in my research (Section 2.2). From this perspective, researchers are active and passive users of their own positionalities, which impact the data gathering, processing, and interpretation of results. BREUER (2003, §13) depicted this approach to a researcher persona as "the embodied, individual, and social researcher-in-interaction," which he elaborated extensively in his article dedicated to the epistemological value of researcher positionality. Approaching researcher positionality this way acknowledges its impact on research and knowledge production. In what follows I focus specifically on three stages of the research conduct (data gathering, processing, and analysis) reflecting on multilingualism and translanguaging in the example of my own research with the Russian-speaking immigrants, relying on the relevant academic literature. [42]

This subsection is a methodological guide to address multilingualism and the researcher positionality specifically during the fieldwork. The following reflections, which I presented in the form of recommendations, emerged from primarily conducting research with an interview method complimented with ethnography and a video method. [43]

Data gathering depends obviously on the research design. A method specifically defines in which form data is collected: as an audio-recorded interview (spoken-to-text; verbal-to-transcribed); as a video-recorded iconographic evidence (video-to-videoscript, video-to-sequences); as ethnographic notes and pictures, etc. Here the focus is on language-dependent methods such as an interview. [44]

Awareness of the researcher's language proficiency may serve as enabling or limiting in conducting research with certain social groups as illustrated previously. For instance, a multilingual researcher may increase an inclination of an interviewee to language borrowing (WEINREICH, 1979 [1953], pp.71-73) or translanguaging (MARTIN-JONES et al., 2012). By the same token, a monolingual researcher may (though unintentionally) be a reason to conceal language proficiencies or cultural experiences by people with a migration background. Here an inquiry into the linguistic biography of the researched helps with this issue, even if a study is oriented on the monolingual data gathering. Immigration, the transition of linguistic barriers, and multilingual experiences could lead to the silence of polyglot dilemma, as mentioned in Section 2.2 earlier. [45]

The researcher’s position as a co-ethnic or a co-migrant is not to be taken for granted as someone hypothetically belonging to a researched immigrant group in terms of a native speaker. HOLLIDAY approached critically this term as a "widespread cultural disbelief" contributing to the native-speakerism ideology, projecting a "neo-racist meaning," and playing into a "native-non-native speaker division" (2015, p.12). Yet, if a scholar is assigned to the researched minority as a native speaker, there should be an awareness of generational and language use differences, duration and conditions of the settlement. These factors add to the continuum of attitudes between the immigrant solidarity and the immigrant rivalry (or negligence) as pointed out by TEMPLE and KOTERBA (2009) while analyzing different generations of Polish immigrants in the UK. Furthermore, despite a researcher's insider or outsider status, "each encounter brings a new negotiation of roles, and requires continuous checks and accountability on the distribution of social positions assumed in an interview" (FEDYUK & ZENTAI, 2018, p.181). These (re)negotiations may lead to continuous boundary-drawing all throughout the fieldwork (SHINOZAKI, 2012, p.1819). That obviously impacts the language constellations of the fieldwork. [46]

Since I've already mentioned on several occasions (Section 2) my transformation from a monolingual to multilingual researcher I won't elaborate any further on this matter. Perhaps, an additional point worth mentioning is related to those projects which require translation services (RESCH & ENZENHOFER, 2017). As in the case with researcher positionality, it is recommended not to neglect a positionality of an interpreter or a translator. By the same token, it is advisable not to treat translation as a primary or original text, but rather to approach it as a translated text and a translator as a mediator (SCHITTENHELM, 2017, p.105; more reflections on translation in INHETVEEN, 2012). [47]

Data processing is not only about converting one data form into another, making it more suitable for analysis (e.g., an audio-recorded interview to a transcript). Data processing is primarily about various degrees of transferability: from a speech to written text; from a dialogical situation to semantic autonomy (a matter of concern in the hermeneutics of GADAMER, 2000 [1996]; RICŒUR, 1976); from one language to another in the case of translation. It is also about transferability of meaning created simultaneously by an interviewee and by a researcher. Specifically, at this stage researchers ought to address the following questions: How do we deal with these different types of transferability? How do we mitigate the lost in translation effect? That is even more relevant if multiple languages are involved from the data gathering to the data dissemination. Below I focus on two aspects: translation and meaning, translanguaging and meaning. [48]

As word-for-word translation has proven insufficient in multicultural contexts, the translation required in such contexts is sense-for-sense. BASSNETT-McGUIRE underlined the differences in these translation strategies: "Martin Luther talked not about übersetzen but about verdeutschen, 'Germanising' ..." (2011, p.6). This type of translation highlights how foreign or different is transformed into familiar. Whereas achieving familiarity through translation is a sign of true quality, the translation of meaning in migration studies has another evaluation. While capturing foreign and explaining it, certain nuances of meaning are not supposed to be lost through this familiarization. A translator, and the same holds true for a researcher, needs to shift ground, to be open to different perspectives and cultural meanings, since a process of translation is about "shape-changing, of re-imagining an Other" (ibid.). That also means an attempt to be an Other in the multiplicity of forms and experiences. Another translation challenge is how to deal with the linguistic hybrids (PERIANOVA, 2019, p.217). Let's consider a specific example. During the interviews, one of the common ways to depict the FSU immigrants was a word Russaki used in Russian-speaking communities in Germany. To capture the meaning spectrum of this word in Russian is problematic, let alone to translate it into German or English. I applied an onion strategy: peeling layer after layer of contextual implications which the linguistic hybrid Russaki has accumulated within the studied communities in Germany (HAVLIN, 2020). [49]

Reflecting on multilingual research, SCHITTENHELM (2017, p.109) stressed the importance of preserving a sporadic language change during the data processing and later incorporating it in interpretation. A different degree of mixing, switching or language interference is a common and described phenomena, especially in the cases of bilingual or multilingual individuals (WEINREICH, 1979 [1953], pp.71-73), in multicultural and hybrid contexts (PERIANOVA, 2019, pp.217-259). This kind of dissolving of language boundaries BASSNETT-McGUIRE understood as "loss and gain" at the same time (2011, p.11). A sudden switch of languages during interviews or casual translanguaging shapes the patterns of meaning creation (Section 3.2). Therefore, it is relevant to ask: Why it appears, under which conditions, and which meaning it communicates. It highlights the researcher-researched relations; it illustrates the communication in action in the multilingual and multicultural contexts; it reveals those elements resistant or difficult for an immediate translation. For this reason, it is paramount to preserve the incidences of translanguaging in original interview transcripts, as well as including them in further interpretation. [50]

There are a range of approaches for where interpretation begins and how to process it in the course of research. Three of them are described below, and can be differentiated as sensitive, processual, and deep interpretation. For REICHERTZ, translation is already an act of interpretation. He criticized any kind of external translation services; instead, he suggested including translators in the research group (2016, p.250). This choice leads to another suggestion: The (sensitive) interpretation of the multilingual or intercultural data has to resemble "an unpacking of the precious porcelain" (ibid.) (i.e., with great care and sensitivity). For ROSENTHAL (2018, p.83), data transcription presents already an act of interpretation. In other words, how a transcript is made and by whom has significance. This points us to the processual interpretation. Further, GADAMER (2000 [1998], p.48) brought to our attention a deeper level of interpretation: the first act of meaning transfer and interpretation is already in listening. He referred to an active listening: Listening to an interviewee's narration transfers something invisible by means of language, by means of unspoken, by means of observations. If the meaning is constructed through an act of speaking and listening, it is inextricable from an understanding (pp.49-50). [51]

These interpretation types sensitive, processual, and deep don't contradict one another. They complement each other and refer to the stages of the interpretation. Thus, different layers of meaning constructions and its interpretation are embedded throughout all stages of the reflective research conduct. This also coincides with the levels of meaning constructions by a research participant, by a researcher, during the data processing which I discussed in detail elsewhere (HAVLIN, 2020, p.71). An example from the multilingual research: If during an interview translanguaging has occurred but later is not reflected in an interview transcript or it is presented as a monolingual text, a researcher has to be aware that it is an act of interpretation. A mixed use of languages has been adjusted to the rules of a standard language (Section 3.1). [52]

Finally, transferring and interpreting the mundane to scientific, what we as researchers practically are doing, faces another challenge. The knowledge of one's social world is organized in terms of relevance to one's actions and not in terms of a standard language or even less in scientific terms (SCHÜTZ, 1944). Is it possible to reduce language dependence while interpreting or presenting results? REICHERTZ (2016, p.146) suggested "to go beyond a language." What does it mean? Apart from the scientific text-formed description of reality, it is beneficial to add a visualization and graphic interpretation by means of diagrams, graphs, schemes. This may require adding, for instance, a method which generates iconographic evidence while methodological composing a project. To a certain degree, a graphic representation of qualitative data escapes the dominance of the written text and decreases a scientific depiction of the social reality primarily in the written form. In other words, it mitigates "the textuality of social reality" (BOHNSACK, 2003, p.240). [53]

Following REICHERTZ's suggestion to go beyond a language, which is also one of the ways to de-naturalize language, below I illustrate one of the attempts to reduce the language dependence. Figures 1 and 2 present a fragment of how the micro-situative-action analysis interprets the iconographic evidence acquired during the ethnography of one of the immigrant cultural associations (Section 2.1). As one of the 8-step sequences, Figure 1 depicts a discussion on individual motivation, a body posture and public appearance among the Russian-speaking members of a hobby dancing group in Xcity (the immigrant agency of the free time HAVLIN, 2020, p.165). That specific discussion took place during one of the rehearsals of the Scheherazade dancing group; it meant to empower the members to be more aware of the bodily expressivity and what level of confidence it communicates in the public context. At first glance, the picture portrays five middle-aged women in their dancing costumes engaged in a conversation. Alia, one of the participants on the right (a half way down in the pictures) seems to be distracted: her attention is divided as she looks to one side. Her glance follows something which is not in the focus of the camera.

Figure 1: A sequence of the discussion about a body posture and motivation [54]

From Alia's posture it seems apparent that there is more to the context depicted on Figure 1. Yet, what seems apparent is invisible, hidden. A situational scheme (Fig. 2) adds these missing elements of the situation, it makes visible all dimensions: 1. a communication circle of the hobby dancers engaged in the conversation; 2. an invisible researcher with the camera closely following the discussion; and 3. an invisible 6-year-old (Alia's son), bored by the lengthy rehearsal and longing for more attention, making hectic movements and loud noises. In order to show the complexity of this sequence (Fig. 1) and all the actors involved, a situational scheme (Fig. 2) reflects on the implicit and explicit multilayered interactions in the specific situation.

Figure 2: A situational scheme of the discussion about a body posture and motivation [55]

Schematically Figure 2 illustrates the underlying structure of Figure 1, its foreground and its background. At the same time, it shows the limitations of the camera focus. While looking at the sequence itself (Fig. 1), all these layers are not visible. The situational scheme together with the sequence and audio transcript provides a broader context for interpretation. It highlights such aspects as conflicting roles of a hobby dancer and a mother, child care and free time, positionality of a researcher, the standpoint limitations of observation and so on. Moreover, it extends the expression possibilities beyond a language or in combination with the descriptions as suggested by REICHERTZ (2016) or BOHNSACK (2003). [56]

With this contribution I aimed to illustrate how the focus on multilingualism and translanguaging enables epistemological possibilities to understand immigrant agency and transnational daily practices. Through my empirical study dedicated to Russian-speaking immigrants in Germany, I posed the methodological question of knowledge and meaning transferability in diverse linguistic and cultural contexts by research subjects or by a researcher. This study exemplified which theoretical and methodological toolkit I utilized to answer the question as well as to show the heuristic potential of multilingualism and reflexive language use, and why we should think about de-naturalizing language. I relied on empirical studies within the scope of comparable immigrant (linguistic) practices in transnational settings from the interdisciplinary literature, allowing me as a sociologist to navigate the language terrain that is methodologically relevant and challenging to migration studies. Conducting the research in the grounded theory tradition, the open-design research on immigrant agency required delving into the reflexive language use of research subjects as well as of the researcher. [57]

Moreover, in this article I investigated broader epistemological and methodological implications of multilingualism in the academic conduct. In doing so, language hierarchies were critically assessed: dominant vs subaltern languages, a standard language vs translanguaging, an educated vs naïve language use, spoken vs unspoken, written vs spoken. Destabilizing these hierarchies allows to de-naturalize language, to approach language use as a languaging process or communication in action rather than as a code or a system beyond the time. At the same time, de-naturalizing language means an awareness of language choices and language use during the research conduct. It requires nuanced reflection of linguistic biographies of the researched subjects as well as the researcher (reflexive researcher positionality). [58]

Further, I offered a set of methodological reflections for data gathering, processing, and interpretation while dealing with multilingual practices. The following strategies proved to be effective: paying attention to the linguistic hierarchies and questioning deviations from a standard language (translanguaging and linguistic hybrids), conceptualizing language as a process (languaging) and visualization (e.g., thinking outside of language through diagrams or schemes). Those strategies I applied in the course of my own research to de-naturalize language and mitigate the language dependence in dealing with the empirical data. [59]

With this article I contributed to the academic discussion which has become increasingly influential. This discussion highlights multilingualism in the academic pursuit, reflexive knowledge production in migration studies, and the reflexive positionality of the researcher. Overall, I addressed the problem of knowledge transferability and mitigation of a lost-in-translation effect while dealing with meanings and significance in the multilingual, transnational contexts. I stressed the significance in approaching multilingual (academic) contexts as those which are not free from linguistic hierarchies and dichotomies. From this point of view, we have to be aware of and acknowledge the way knowledge travels and is distributed around the globe (COLLYER, 2018), linguistic preferences of the academic publishing industry (SALÖ, 2017) and, related to that, local/global (in)visibility of a researcher (HANAFI, 2011). To investigate these aspects of language use in academic hierarchy and knowledge production emerges as a plausible development of the given article. [60]

Acknowledgments

I thank Jessica STOCK, John DAER, Karin SCHITTENHELM and the participants of the research workshop at the University of Siegen for commenting on an earlier draft of this article. I am also grateful to the FQS editor Katja MRUCK and two anonymous FQS reviewers for their through and generous feedback. I carry all responsibility for any flows in the article.

1) All translations from non-English texts are mine. <back>

2) The detailed account on tricksterism and tricksters, TLOSTANOVA in the co-authorship with MIGNOLO (2012) offered in the book "Learning to Unlearn. Decolonial Reflections from Eurasia and the Americas." They engaged "the contemporary understanding of the term, which is linked with yet departs from the classical mythological, religious, and folklore meaning" (i.e., God-like creatures or people with supranatural characteristics) (p.88). In the contemporary use, such features are associated with tricksters: "ambiguity, deceit of authority, playing tricks on power, metamorphosis, a mediating function between different worlds, manipulation and bricolage as modes of existence" (ibid.). <back>

3) Termin [an appointment] and Kirche [a church] are the German words which emerge occasionally in the Russian-German translanguaging in Germany. <back>

4) I derive the term naïve language from the concept naïve writing which KOZLOVA and SANDOMIRSKAJA applied to indicate the type of writing in people's documents (e.g., letters, diaries, memoires): "'People's documents' represent different types of writing. They are not written in the language of literature, without periods and commas, with orthographic and stylistic mistakes" (1997, p.8). By the same token, naïve languageis the type of language used by less educated or less language-cautious groups, where oral and written forms deviate from the normativity of educated language. <back>

5) For protecting the interviewees' identities, their names were anonymized. <back>

Abbott, Andrew (1995). Sequence analysis: New methods for old ideas. Annual Review of Sociology, 21, 93-113.

Alba, Richard D. & Foner, Nancy (2017). Strangers no more: Immigration and the challenges of integration in North America and Western Europe. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Amelina, Anna (2010). Searching for an appropriate research strategy on transnational migration: The logic of multi-sited research and the advantage of the cultural interferences approach. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 11(1), Art. 17, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-11.1.1279 [Accessed: March 10, 2017].

Amelina, Anna (2012). Hierarchies and categorical power in cross-border science: Analyzing scientists' transnational mobility between Ukraine and Germany. Working paper, Centre on Migration, Citizenship and Development (COMCAD), Fakultät für Soziologie, Universität Bielefeld, Germany, https://www.ssoar.info/ssoar/handle/document/51038? [Accessed: February 12, 2019].

Amelina, Anna & Faist, Thomas (2012). De-naturalizing the national in research methodologies: Key concepts of transnational studies in migration. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 35(10), 1707-1724.

Amelina, Anna; Boatcă, Manuela; Bongaerts, Gregor & Weiß, Anja (2020). Theorizing societalization across borders: Globality, transnationality, postcoloniality. Current Sociology, 21(3), 1-12, https://doi.org/10.1177/0011392120952119 [Accessed: October 13, 2020].

Anstatt, Tanja & Rubcov, Oxana (2012). Gemischter Input – einsprachiger Output? Familiensprache und Entwicklung der Sprachtrennung bei bilingualen Kleinkindern. In Barbara Jańczak, Konstanze Jungbluth & Harald Weydt (Eds.), Mehrsprachigkeit aus deutscher Perspektive (pp.73-94). Tübingen: Narr.

Auer, Peter (Ed.) (2003). Code-switching in conversation: Language, interaction and identity. London: Routledge.

Bachmann-Medick, Doris & Kugele, Jens (Eds.) (2018). Migration: Changing concepts, critical approaches. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Bakker, Peter & Mous, Maarten (Eds.) (1994). Studies in language and language use: Vol. 13. Mixed languages: 15 case studies in language intertwining. Amsterdam: Institute for Functional Research Into Language and Language Use (IFOTT).

Bankovskaya, Svetlana [Баньковская, Светлана] (2016). Видеосоциология: теоретические и методологические основания [Videosociology: Theoretical and methodological foundation]. Russian Sociological Review, 15(2), 129-166.

Barros, Sandro R. (2020). Babel at 35,000 feet: Banality and ineffability in qualitative research. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 21(2), Art. 17, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-21.2.3413 [Accessed: December 15, 2020].

Bassnett-McGuire, Susan (2011). Reflections on translation. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

Bates, Charlotte (2018). Introduction: Putting things in motion. In Charlotte Bates (Ed.), Routledge advances in research methods: Vol. 10, video methods. Social science research in motion (pp.1-9). London: Routledge.

Bernsand, Niklas (2001). Surzhyk and national identity in Ukrainian nationalist language ideology. Berliner Osteuropa Info, 17, 38-47.

Bernstein, Basil (2003 [1971]). Class, codes and control: Applied studies towards a sociology of language (Vol. 2). London: Routledge.

Bohnsack, Ralf (2003). Qualitative Methoden der Bildinterpretation. Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft, 6(2), 239-256.

Bourdieu, Pierre (2003 [1992]). Language and symbolic power. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Braidotti, Rosi & Regan, Lisa (2017). Our times are always out of joint: Feminist relational ethics in and of the world today: An interview with Rosi Braidotti. Women: A Cultural Review, 28(3), 171-192. https://doi.org/10.1080/09574042.2017.1355683 [Accessed: September 29, 2019].

Breuer, Franz (2003). Subjectivity and reflexivity in the social sciences: Epistemic windows and methodical consequences. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 4(2), Art. 25, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-4.2.698 [Accessed: March 2, 2020].

Collyer, Fran M. (2018). Global patterns in the publishing of academic knowledge: Global North, global South. Current Sociology, 66(1), 56-73.

Corbin, Juliet & Strauss, Anselm (1990). Grounded theory research: Procedures, canons and evaluative criteria. Zeitschrift für Soziologie, 19(6), 418-427.

Crane, Lucy G., Lombard, Melanie B. & Tenz, Eric M. (2009). More than just translation: Challenges and opportunities in translingual research. Social Geography, 4, 39-46.

Crean, Mags (2018). Minority scholars and insider-outsider researcher status: Challenges along a personal, professional and political continuum. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 19(1), Art. 17, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-19.1.2874 [Accessed: November 10, 2020].

Del Gaudio, Salvatore [Дель Гаудио, Сальваторе] (2015). Украинско-русская смешанная речь "суржик" в системе взаимодействия украинского и русского языков [The Ukrainian-Russian mixed speech "suržyk" within the system of Ukrainian and Russian interaction]. Slověne, 2, 214-246.

Dirim, Inci & Auer, Peter (2004). Türkisch sprechen nicht nur die Türken. Linguistik, Impulse & Tendenzen, 1612-8702 (Vol. 4). Berlin: de Gruyter.

Emerson, Robert M.; Fretz, Rachel I. & Shaw, Linda L. (2011). Writing ethnographic fieldnotes. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

European Commission (2012). Europeans and their languages: Special Eurobarometer 386. Report, https://data.europa.eu/data/datasets/s1049_77_1_ebs386?locale=en [Accessed: August 19, 2019].

Faist, Thomas (2000). Transnationalization in international migration: Implications for the study of citizenship and culture. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 23(2), 189-222.

Faist, Thomas (2004). The transnational turn in migration research: Perspectives for the study of politics and policy. In Maja Povrzanovic Frykman (Ed.), Transnational spaces. Disciplinary perspectives. Willy Brandt conference proceedings (pp.11-45). Malmö: Malmö University, International Migration and Ethnic Relations (IMER).

Falicov, Celia J. (2005). Emotional transnationalism and family identities. Family Process, 44(4), 399-406.

Fedyuk, Olena & Zentai, Violetta (2018). The interview in migration studies: A step towards a dialogue and knowledge co-production? In Ricard Zapata-Barrero & Evren Yalaz (Eds.), Qualitative research in European migration studies (pp.171-188). Berlin: Springer.

Gadamer, Hans-Georg (2000 [1996]). Hermeneutik – Theorie und Praxis, In Hans-Georg Gadamer, Hermeneutische Entwürfe: Vorträge und Aufsätze (pp.3-11). Tübingen: Mohr-Siebeck.

Gadamer, Hans-Georg (2000 [1998]). Über das Hören. In Hans-Georg Gadamer, Hermeneutische Entwürfe: Vorträge und Aufsätze (pp.48-55). Tübingen: Mohr-Siebeck.

Giddens, Anthony (1984). The constitution of society. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Glick Schiller, Nina (2007). Beyond the nation state and its units of analysis: Towards a new research agenda for migration studies. In Karin Schittenhelm (Ed.), Concepts and methods in migration research. Conference reader "Concepts and methods in migration research" (pp.39-72), http://sowi-serv2.sowi.uni-due.de/cultural-capital/reader/Concepts-and-Methods.pdf [Accessed: October 19, 2019].

Glick Schiller; Nina, Basch, Linda & Szanton-Blanc, Cristina (1992). Towards a transnational perspective on migration: Race, class, ethnicity, and nationalism reconsidered. New York, NY: New York Academy of Sciences.

Goitom, Mary (2019). Multilingual research: Reflections on translating qualitative data. The British Journal of Social Work, 38(3), 548-564.

Gordin, Michael D. (2015). Scientific Babel: How science was done before and after global English. London: The University of Chicago Press.

Grjasnowa, Olga (2021). Die Macht der Mehrsprachigkeit: Über Herkunft und Vielfalt. Berlin: Duden.

Hanafi, Sari (2011). University systems in the Arab East: Publish globally and perish locally vs publish locally and perish globally. Current Sociology, 59(3), 291-309.

Hanna, Lisa; Hunt, Sonja & Bhopal, Raj (2008). Insights from research on cross-cultural validation of health-related questionnaires. Current Sociology, 56(1), 115-131.

Hantrais, Linda (2005). Combining methods: A key to understanding complexity in European societies? European Societies, 7(3), 399-421.

Havlin, Tetiana (2015). Shift in social orders—shift in gender roles? Migration experience and gender roles. Current Issues in Personality Psychology, 3(3), 185-191, https://doi.org/10.5114/cipp.2015.53229 [Accessed: January 15, 2016].

Havlin, Tetiana (2020). Immigrant agency: A case of Russian-speaking immigrants and citizens in Germany. Habilitation manuscript, Sociology, University of Siegen, Siegen, Germany.

Hitlin, Steven & Elder, Glen H. (2007). Time, self, and the curiously abstract concept of agency. Sociological Theory, 25(2), 170-191.

Holliday, Adrian (2015). Native-speakerism: Taking the concept forward and achieving cultural belief. In Anne Swan, Pamela Aboshiha & Adrian Holliday (Eds.), (En)countering native-speakerism. Global perspectives (pp.11-25). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Inhetveen, Katharina (2012). Translation challenges: Qualitative interviewing in a multi-lingual field. Qualitative Sociology Review, 8(2), 28-45, http://www.qualitativesociologyreview.org/ENG/Volume22/QSR_8_2_Inhetveen.pdf [Accessed: February 5, 2020].

Kellman, Steven G. (2000). The translingual imagination. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska press.

Khosravi, Shahram (2010). "Illegal" traveler: An auto-ethnography of borders. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.