Volume 22, No. 3, Art. 7 – September 2021

Architecture and Sociology: A Sociogenesis of Interdisciplinary Referencing

Séverine Marguin

Abstract: In this article, I examine the relationships between architecture and sociology through a historical lens. I provide an analysis of their cross-referencing since their respective disciplinary foundations in line with the histoire croisée [crossed history] approach. I also address the positions held by architectural researchers in sociology and by sociologists in architectural research both at the level of the disciplinary object itself—"architecture" and "society"—and at the level of the disciplines themselves: Do architectural researchers work with sociological knowledge or collaborate with sociologists and vice versa? In the reconstructed narrative, I demonstrate that, despite repeated attempts at rapprochement, collaborations did not become sustainable until the early 2010s, when—in the course of the what became known as the "design turn"—fundamental new aspects in interdisciplinary referencing could be observed, pointing to an integrative quality in both disciplines.

Key words: architectural research; design research; figurational sociology; re-figuration of spaces; sociology of science; sociology of space; spatial analysis; urban planning; urban sociology

Table of Contents

1. The Re-Figuration of Spaces and Different Disciplinary Cultures

2. How Do We Investigate Referencing Between Disciplines Empirically?

2.1 "Discipline" and "epistemic culture" as reference points for analysis

2.2 Methodical approach to a sociogenesis of referencing between architecture and sociology

3. A Sociogenesis of Referencing Between Architecture and Sociology

3.1 Architecture in sociology

3.2 Sociology in architectural research

4. The Emergence of a Segmented Field of Spatial Research?

4.1 Neighboring subdisciplines: Urban planning, urban sociology, urban design, urban studies in a state of flux?

4.2 A field of spatial research?

5. Interdisciplinarity as a Solution for the Challenging Investigation of Re-Figuration of Spaces

1. The Re-Figuration of Spaces and Different Disciplinary Cultures

In the context of this thematic issue, which is devoted to the interrelationships between what is referred to as the "re-figuration of spaces" and "cross-cultural comparison," I would like to make a specific contribution from a sociology of science perspective by focusing on the comparison of epistemic cultures. Hence, I am not aiming at a space-based comparison of cultures, but rather at investigating in an empirical manner how different academic disciplines reference each other. In this sense, in this article, I will attempt to identify specific effects of the re-figuration of spaces on the production of knowledge itself. I aim to make a theoretical contribution to the interplay between the processes of establishing disciplines and epistemic cultures in the context of interdisciplinary studies. In most analyses in sociology of science—for example, about social research (KNOBLAUCH, FLICK & MAEDER, 2005) or about migration research (BORKERT, MARTÍN PÉREZ, SCOTT & DE TONA, 2006)—the disciplinary process is conceived in conjunction with the formation of the corresponding subject-specific culture. In contrast, in this article, I will explore the influence of other disciplines on the formation of epistemic cultures in a given discipline and investigate the extent to which this paves the way for potential interdisciplinary collaborations. I am mostly interested in the spatial disciplines, specifically: What place does sociology occupy among architects? And what role does architecture play for sociologists? [1]

Urban research, urban design, urban studies, urban planning, architectural research, spatial sociology, architectural sociology, urban sociology, planning sociology, cultural geography, etc.: Specialized disciplinary branches in the field of spatial and urban research have multiplied since the early 2000s. This phenomenon is congruent with what has been designated as the spatial turn (LÄPPLE, 1991; LÖW, 2017). KNOBLAUCH and LÖW (2017) already suggested that "the results of a huge quantity of spatial studies [...] can be interpreted in terms of the spatial re-figuration of society" (p.6). [2]

I will begin this contribution by considering how the re-figuration of spaces can be indicated not only by quantity, but also by specific, disciplinary qualities of the spatial turn. I will therefore focus my analysis on the disciplinary effects and, in particular, on the relationships between architectural research and sociology. My leading hypothesis is that the theoretical and empirical challenges induced by the re-figuration of spaces are met by the creation of new relations between the disciplines. As a case of "broad interdisciplinarity" (KLEIN, 2017, p.27) at the interface between design and science, referencing the disciplines architecture and sociology entails specific questions and stakes. In order to demonstrate that these are "new" relations, I will undertake a historical analysis of this interdisciplinary referencing. [3]

I will firstly explore the interplay between the concepts of knowledge cultures and disciplines as a heuristic instrument for the sociology of science, introducing the methods of histoire croisée [crossed history] for this comparative analysis (Section 2). I will then outline the different forms of historical referencing and collaborations between architects and sociologists since their disciplinary formations. Despite repeated attempts at rapprochement, the reconstructed narrative demonstrates that collaborations have never become sustainable, and only since the early 2010s have they revealed fundamental new aspects that point to an integrative quality (Section 3). I will then present initial reflections on the emergence of a field of (human-centered) spatial research in which sociology and architecture, as well as urban planning, play a specific role (Section 4) before concluding with the potential of interdisciplinarity for spatial research (Section 5). [4]

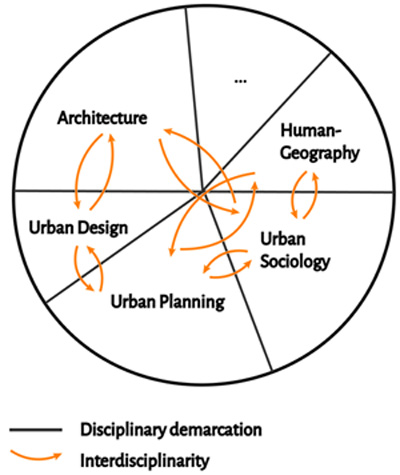

In the early 2000s, the historian SCHLÖGEL (2003) expressed this in the sheer turbulence of the spatial turn itself: "[T]he sources of the spatial turn are abundant, and the current they feed is powerful—more powerful than the dams and barriers of the disciplines" (p.12)1). My hypothesis is that, twenty years later and in the course of the re-figuration of spaces, a field of spatial research is being generated that is characterized by ambivalent dynamics: On the one hand, it is possible to observe the formation of numerous specific subdisciplines that are isolated from one another, and, on the other hand, an increasing interdisciplinarity between these same disciplines is apparent. It follows, therefore, that opposing tendencies are at work: These are demarcations that simultaneously always expose attempts to overcome and cross (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Opposing tendencies in the emerging field of spatial research [5]

2. How Do We Investigate Referencing Between Disciplines Empirically?

When structuring an academic field of spatial research, the disciplines of architecture, urban planning, and sociology are ranked centrally. How have these disciplines been interlinked historically? Or have they ignored each other completely? For pragmatic reasons, I will initially not consider human, social, and cultural geography or urban and cultural anthropology, even if these disciplines occupy an important position in the field of spatial research as well. In order to reconstruct the sociogenesis of this interdependence between architecture, urban planning, and sociology, I will employ the method of histoire croisée (WERNER & ZIMMERMANN, 2003, 2006) since it serves as an ideal tool for such a figurational sociological investigation. [6]

2.1 "Discipline" and "epistemic culture" as reference points for analysis

In the course of the modern differentiation of the science system, disciplines were established as "the primary frame of reference in scholarship and science" (HEILBRON, 2004, p.23). However, both politicians and scientists are currently challenging this position. The relevance of the concept of "discipline" in times of change in the central structures of science is being questioned:

"More recent scientific research shows that simple disciplinary classification systems are no (longer) adequate: On the one hand, a process of further differentiation into numerous subdisciplines can be observed; on the other hand, science is much more strongly characterized by multidisciplinarity, interdisciplinarity and continuous processes of fusion of disciplines" (BAUR, BESIO, NORKUS & PETSCHICK, 2016, p.16). [7]

When researchers in the anthropologically inspired field of science and technology studies (STS) claimed (micro-sociological) scientific research under the banner of laboratory studies, they neglected or even strictly rejected disciplinary categorization in terms of scientific theory or sociology:

"In parallel with the delegitimization of the disciplinary order in science policy, the study of the functioning of the academic space has also been marginalized by the new generation of sociologists of science who became dominant in the early 1980s. A central object in Robert Merton's sociology of science—university disciplines—have been largely neglected. In the 'social studies of science', which have taken over from Mertonian sociology, the study of scientific institutions has been abandoned in favour of microsociological approaches based on direct observation of local practices and the dissection of interactions between the actors (and actants) involved. The dominant orientation of science research has thus shifted from a sociology of scientific institutions to an ethnography of research sites, controversies, and networks of researchers. The dominant currents of 'social science studies' have not only mobilized ethnographic resources by focusing on effective research practices, they have simultaneously contributed to dissolving institutional and social structures in the supposed fluidity of practices, in processes of assembly and disassembly, association and dissociation, thus eliminating the structural conditions that make these practices possible" (HEILBRON & GINGRAS, 2015, p.4). [8]

But how can research into interdisciplinarity be performed without considering the structural conditions of disciplinary formation? Following HEILBRON and GINGRAS for the francophone discourse, as well as BAUR et al. (2016) and KNOBLAUCH (2018) for the German-speaking discourse, I plead for the articulation of a (possibly ethnographic) microanalysis with a structure-oriented macroanalysis, in the sense of BOURDIEU's (1984 [1979]) field-theoretical approach. "Discipline" is thus understood as "an organized form of knowledge" (FABIANI, 2006, p.15), which faces two contradictory, historical objects:

the doctrine of canonized and stable knowledge—the goal of discipline-building in this case is the reproduction of a body of knowledge or a doctrine;

the development of new knowledge within a self-limited collective. [9]

The goal of discipline-building, then, is innovation (FABIANI, 2006; HEILBRON, 2004). In this sense, by successfully integrating this "Essential Tension" (KUHN, 1977), the concept of "discipline" is "a suitable description of heterogeneous practices registered under the name of science" (FABIANI, 2006, p.15). The process of establishing a discipline is accompanied by constructing a disciplinary culture—or as KUHN (1970) described it, a "disciplinary matrix" (p.182). Disciplinary cultures are composed of three elements:

symbolic generalizations (p.183) shared by the whole collective;

belief in the validity of certain statements—a shared belief in certain truths (p.184);

values (ibid.) underpinning practice. [10]

The concept of "epistemic culture," according to KUHN and as it has been used by KNORR CETINA (2002 [1999]) and LEPENIES (1985), as well as by various research collaborations—such as the successful interdisciplinary Collaborative Research Centre 435 "Knowledge Cultures and Social Change"—"has undergone an enormous career in various scientific disciplines in the last decade" (SANDKÜHLER, 2014, p.65). Following KELLER and POFERL, I understand epistemic cultures as the "specific relationships between social actors, practices, institutional settings, and material factors in the process of generating knowledge" (2016, §17), which in many cases represent the disciplinary boundaries. However, a discipline is not simply the repository of shared faith and shared discourse; it points to solid institutional infrastructures (BARLÖSIUS, 2016) that serve as "an instrument of social control to which the ideological regulation of scientific activities belongs" (LECLERC, 1989, p.23). Therefore, it seems important to clarify three aspects of my understanding of the concept of discipline, which will be explained in more detail below:

a heterogeneity and dynamic internal development of the disciplines;

a social and institutional—sometimes conflictual—relation of the disciplines to each other in the academic field;

external factors that may have an influence on the disciplinary figurations. [11]

2.1.1 Heterogeneity and the transformation of disciplines

The professional culture of a discipline should not be conceived monolithically or statically, but instead is characterized by heterogeneity and change. In their agonistic relationships to one other, intradisciplinary relations are part of the disciplinary matrix: Disciplines such as sociology are moving structures of relations and "form a thoroughly heterogeneous or even conflictual topography within a particular academic tradition while nevertheless sharing common features that distinguish them when viewed from an external perspective" (KELLER & POFERL, 2016, §21, my emphasis). [12]

This diagnosis of plurality has been particularly well researched for the field of sociology: FABIANI (2006), for example, spoke of the "cacophony of sociology" (p.21) and PASSERON (1994) of a "Theoretical Plurality." More recent works, such as those by SCHMITZ, SCHMIDT-WELLENBURG, WITTE and KEIL (2019), showed how the field of German-language sociology with its schools and dividing lines exhibits a relational structure. In contrast, an investigation into the topography of the academic fields of architecture and urban planning is still pending (MARGUIN, 2021a). [13]

In addition to the question of their plurality, scholars in the fields of sociology of science have also researched the transformations of disciplines in depth. Without a doubt, KUHN's (1970 [1962]) theory of scientific revolution with his claim of paradigm shifts is the most widely-known work on this issue. Other important works to be mentioned in this context are ELIAS's (1982) study on scientific establishments and ABBOTT's (2001) study explaining how intradisciplinary plurality is modeled along dichotomous pairs: social structure/culture, individualism/holism, constructivism/realism, positivism/interpretation, quantitative/qualitative, basic/applied research, etc. In his theory of "fractal distinction" (p.11), ABBOTT proposed a path-dependent development in the rhythm of generations, which in turn explains the generative grammar of theoretical constructions that are (re)discovered again and again. Finally, BOURDIEU (2001) coupled the changes within the disciplinary field with external factors, be it within the scientific field or in social space. In its limited version (LAHIRE, 2006; LEMIEUX, 2011)—whether for the analysis of modern or postmodern fields of scientific or artistic production—BOURDIEU's field theory still proves highly relevant inasmuch as he modeled the interconnected embedding of fields, sub-fields, disciplines, and practices relationally (MARGUIN, 2019). [14]

2.1.2 The hierarchical space of disciplines in the academic field

Even if it is possible to pursue an intrinsic logic within disciplines, they cannot be detached from social space. They are initially anchored in the scientific field. In the model of the differentiation of modern sciences, an articulation model is implicitly assumed, in which—based on the idea of complementarity of disciplines—it is presumed that disciplines would pursue a common goal. Some still defend this MERTONian structural functionalist perspective, such as STICHWEH (1992), who asserted that the order of discipline can be thought of as a "horizontal coexistence" among "complete equals" (p.7). Many authors, however, strongly deny this (FABIANI, 2006; HEILBRON, 2004). For them, the scientific field is structured through conflicts and frictions between disciplines contingent upon power relations and hierarchies: Each discipline "demarcates areas of academic territory, allocate[s] privileges and responsibilities of expertise, and structure[s] claims on resources" (LENOIR, 1997, p.58) and, in this sense, has a potentially conflicting relationship to other (neighboring) disciplines (BOURDIEU, 2001). [15]

It is particularly striking to observe how members of disciplines with contrasting epistemic cultures demarcate their respective disciplines from each other—and in turn contribute to the process of discipline creation, that is "a definable circle of scientific actors in a specific field of research develops a specific way of producing, evaluating, and circulating knowledge and in doing so differentiates itself from other (likewise scientific) actors" (KELLER & POFERL, 2016, §17). In the case of spatial and urban research, such mechanisms of distinction and demarcation manifest themselves clearly through the multiplication of specific sub-branches within existing disciplines such as urban research, urban development, urban design, urban studies, urban planning, architectural research, spatial sociology, architectural sociology, urban sociology, planning sociology, and cultural geography. [16]

2.1.3 External factors and the process of creating disciplines

In this "series of structural interlocking [where the laboratory is defined as [a] social microcosm, [...] itself located in a space with other laboratories constituting a discipline, [...] itself located in a space, also hierarchical, of disciplines" (BOURDIEU, 2001, p.68), it is important to consider the last related level, namely, that of the social space in which the field of scientific production is embedded:

"Alongside the issue of the internal differentiation of science, the issue of how science and other social fields are related [...] arises at the macro-level [...]. A whole line of research is therefore devoted to establishing the extent to which knowledge production is autonomous and to what extent knowledge production is influenced by external logics. The fact that other social fields strongly influence science is demonstrated, for example, by the diffusion of so-called 'Mode 2 science' or 'transdisciplinary research' [...], which no longer asks questions based on the disciplinary state of the art of research, but both defines research questions in cooperation with external institutions and at least partly validates research by using criteria defined outside science" (BAUR et al., 2016, p.13). [17]

Current changes that affect the scientific field as a whole—such as economization (MÜNCH, 2016; WEINGART, 2008), projectification (BAUR, BESIO & NORKUS, 2018), and social referencing in the sense of public sociology (BURAWOY, 2005; TREIBEL, 2017)—demonstrate that a new "societal contract" (WEINGART, 2008, p.477) between the university and society has been negotiated. These external factors have a decisive effect on the development of the disciplines and should therefore be taken into account. [18]

In the special case of the interdisciplinarity between social sciences and design disciplines I deal with in this article, such problems prove to be particularly explosive. This bold collaboration massively challenges our respective understanding of knowledge and science and their relationship to society and even more fundamentally to reality. How do we want to generate knowledge? For whom? For what purpose? There is a disciplinary divide of views along the line between basic research, theory, and analytical thinking in sociology and applied research, practice, and synthetic thinking in architecture (MARGUIN, 2021a, 2021b). The design turn (MAREIS, 2010; SCHÄFFNER, 2010)—defined as the integration of the design disciplines into natural sciences, humanities, or social sciences—resonates with actual research policy debate such as mode 2 or triple helix:

"A change of perspective is currently taking place in various scientific disciplines under the buzzwords of design. The natural sciences have become the pacemaker of a development that is not only about analyzing the world to understand it, but which has gone on to redesign it from scratch using digital media, biotechnology, and nanotechnology" (DOLL, 2016, p.11). [19]

The design-based disciplines, with their strong application-oriented and future-oriented focus, indeed offer clear advantages for the "problem-solving" or for the drive for innovation that is connected to the idea and the requirements of "knowledge society" (HEILBRON & GINGRAS, 2015, p.6). The clash between design and science raises urgent questions with regard to the régime de savoirs [knowledge regime] (PESTRE, 1997, 2003) that the academic field should regulate—and especially regarding the idea of autonomy of science. Does such a rapprochement between design and social science compel the establishment of a new knowledge regime that advocates performative transdisciplinarity and could itself lead to the erosion of the disciplinary regime (HEILBRON, 2004)? It is in such a field of tension that the narrative of the rapprochement between architecture and sociology can currently be found (MARGUIN, 2021a, 2021b). I would like to explain "legitimate from illegitimate references, forming traditions and [canonizations]" (KELLER & POFERL, 2016, §20) between the disciplines from a historical standpoint in order to put the current narrative into perspective, quite in the sense of a sociogenesis (BOURDIEU, 2013 [1972]; ELIAS, 2006a [1983]). [20]

2.2 Methodical approach to a sociogenesis of referencing between architecture and sociology

My approach to reconstructing the sociogenesis of the interdependence or demarcation between the disciplines of architecture and sociology is inspired by figurational sociology, which I combine with a field-theoretical framework. BOURDIEU and ELIAS "share some common theoretical assumptions and [...] draw similar methodological consequences from these theoretical assumptions" (BAUR, 2017, p.43), insofar as both authors argued for a process-oriented sociology in order to take into account possible burdens from the past as well as expectations for the future in the analysis of current conditions:

"The weakness of many theoretical and empirical studies confined in their temporal focus, however, lies in the fact 'that they have lost their connection with the past as well as with the future' (Elias, 2006b, p.401). Instead, sociologists should also look at the past—and not only because it is interesting in itself [but also because] 'it help[s] to create a greater awareness of contemporary problems and especially of potential futures' (Elias, 2006b, p.407). Only when looking at the past can one analyse the relation between the macro- and micro-level, the long-term evolution of contemporary processes, the changes in the balances of power and functional equivalents as well as 'the play and counter-play of long-term dominant trends and their counter-trends' (Elias, 2009 [1977], p.27; Treibel, 2008)" (BAUR & ERNST, 2011, p.125). [21]

In the following section, I will present the methodical approach underlying the reconstruction of the history of relations between the disciplines of architecture and sociology. For this purpose, I will first make use of the histoire croisée method, which is able to provide specific tools for such a process-sociological investigation—as a complement to ELIAS, who gave no precise methodological instructions. As a toolbox, histoire croisée is particularly relevant in that it provides the tools needed to analyze mutual referencing and addressing, as well as interactions between different cultural entities. [22]

2.2.1 The histoire croisée approach

The histoire croisée approach was developed in the field of comparative and transfer studies. Much more than a hermetic confrontation or the pursuit of one-sided mediations between different cultural entities—be they countries, fields, or cultures—histoire croisée is concerned with how these entities have been constituted in relation to one another or interwoven with one another: "'Histoire croisée' associates social, cultural, and political formations, generally at the national level, that are assumed to bear relationships to one another" (WERNER & ZIMMERMANN, 2006, p.31). As a relational approach, histoire croisée concentrates on the connections that are materialized or projected in the social space between different historically-grown formations. The approach was developed within the French historical and social sciences in response to the limitations of comparative and transfer studies and has been mostly used for Inner-Western comparison so far—it could be interesting to evaluate the pertinence of this approach for North-South comparisons by linking it to the debates on decentering and delinking (MIGNOLO, 2007, 2014), but that is not possible in the scope of this article. [23]

The aim of histoire croisée is to address the deficit in reflexivity due to a lack of control over important self-referential loops and to offer a methodical toolset. Before I present this in more detail, I will briefly outline the main focuses of histoire croisée. The starting point of histoire croisée is the work on the categories of analysis, which in comparative studies are usually regarded as "invariable":

"Given the pitfalls of asymmetric comparisons—postulating a similarity between categories on the basis of a simple semantic equivalent, without questioning the often divergent practices encompassed by them—or negative comparisons—evaluating a society based on the absence of a category chosen because of its relevance to the initial environment of the researcher—great care is called for in assessing the analytical impact of the categories used. Such care can be exercised through systematic attention to the categories in use, in the dual sense of categories of action and of analysis" (WERNER & ZIMMERMANN, 2006, p.44). [24]

According to WERNER and ZIMMERMANN, empirical objects are historically situated and consist of multiple interwoven dimensions. They are always changing, sometimes unstable and sometimes very solid. For this reason, it is necessary to historicize the moving categories of analysis, which is why the (social-scientific) approach is unequivocally called crossed "history." Here, the method meets the principles of sociogenesis expressed by ELIAS (2006b [1969]). Histoire croisée is considered a multidimensional approach,

"that acknowledges plurality and the complex configurations that result from it. Accordingly, entities and objects of research are not merely considered in relation to one another but also through one another, in terms of relationships, interactions, and circulation" (WERNER & ZIMMERMANN, 2006, p.38). [25]

Be it as an inherent crossing of the objects themselves, a crossing of (scientific) perspectives in the constitution of the object or a crossing of standards, attention is paid to the specific speaker positions (BOURDIEU, 1990 [1987]). In order to do justice to these efforts, the approach contains five specific important methodological dimensions: the position of the observer, the scale of comparison, the object of comparison, the potential conflict between the synchronic and diachronic logics, and interactions between the objects of comparison (WERNER & ZIMMERMANN, 2006). The first methodological dimension of histoire croisée is the position of the observer and his or her integration into the field or research. The debate about positionality or location is longer in social research: How should one's subjectivity as a researcher be dealt with? To this end, three sub-dimensions of subjectivity have been distinguished in German-language debates in the social and historical sciences (BAUR, 2008; BAUR & ERNST, 2011): partiality—which must be avoided—perspectivity (outsider perspective), and Verstehen [understanding] (insider perspective). In this context, WERNER and ZIMMERMANN (2006) criticized the fact that comparative studies often assume an outsider perspective, in which the point of view is ideally placed equidistantly to the objects in order to produce an apparently symmetrical view. However, as WERNER and ZIMMERMANN pointed out,

"scholars [are] always, in one manner or another, engaged in the field of observation. They are involved in the object, if only by language, by the categories and concepts used, by historical experience or by the pre-existing bodies of knowledge relied upon. Their position is thus off center" (p.34). [26]

It is therefore a matter of taking into account the asymmetry of the starting point: In my case, as an "internal ethnographer of science," this question is particularly explosive and entails specific methodological challenges (MARGUIN, RABE & SCHMIDGALL, 2019). What is special about histoire croisée is that it addresses the fact that the researcher belongs to one of the cultures or fields being studied. In my case, this means that, as a French sociologist, I perform research on the relationship between German architecture and sociology. Beyond a certain detachment, a reality check regarding potential ignorance and assumptions about otherness is advocated in this approach, or in other words, a reflective way of dealing with one's own cultural affiliation and all associated self-evidence. The second methodological dimension of histoire croisée concerns the scale of comparison. This does not refer to the temporal "comparison scale" [...], which can be used to determine the "before," "after," or "at the same time" (BAUR, 2005, p.113), but rather to the different spatial, institutional, and organizational levels at which the comparison is carried out (HOERNING, 2021).

"Whether situated—to take but a few examples—at the level of the region, the nation-state, or the civilization, none of these scales is absolutely univocal or generalizable. They are all historically constituted and situated, filled with specific content, and thus are difficult to transpose to different frameworks" (WERNER & ZIMMERMANN, 2006, p.34). [27]

Here, the proponents of histoire croisée first call for "break[ing] with a logic of pre-existing scales to be used 'off the shelf,' as is often the case for national studies" (p.42), pleading instead for a "multiscopique approach" (REVEL, 1996, p.26). The scales are constituted by, with, and against each other:

"This is the case, for example, of the make-up of the category of the unemployed in Germany between 1890 and 1927. Constructors of this category act, simultaneously or successively, on different levels: municipal, national, even international, in such a manner that these varying scales are in part constituted through one another. These scales could not be reduced to an external explicatory factor but rather are an integral part of the analysis. Thus, from a spatial point of view, the scales refer back to the multiple settings, logics, and interactions to which the objects of analysis relate" (WERNER & ZIMMERMANN, 2006, p.43). [28]

In my case, the analysis unfolds on a scale of the (national or German-speaking) academic field, of the discipline as an independent field (architecture, urban planning, and sociology), of the institutions—including universities (such as Technische Universität Berlin [TU Berlin]), schools (such as Faculty IV: Planning Building Environment), departments (such as Department of Sociology), and chairs and research areas (such as Chair for Sociology of Planning and Architecture)—of research projects (such as the Collaborative Research Center [CRC] 1265 "Re-Figuration of Spaces"), and of individual researchers. Focus is placed on the interdependence and mutual effects of these different scales. The third methodological dimension of histoire croisée is the object of comparison. Here, one should take care that the object is not assumed to be "given" in the compared fields:

"This raises the problem of the historical and situated constitution of the objects of the comparison. To avoid the trap of presuming naturalness of the objects, it is necessary to pay attention to their historicity, as well as to the traces left by such historicity on their characteristics and their contemporary usages" (p.34). [29]

In my case, I am concerned with the question of the disciplines themselves, the constitution of which is to be considered historically and situationally. This concept of "architectural research" is relatively controversial and diverse. Can one even speak of a discipline in this case? Or a field of research? These are some of the research questions that I will explore below without assuming their existence a priori. The fourth methodological dimension of histoire croisée is an awareness of the potential conflict between the synchronic and diachronic logics: If a comparison involves more of a synchronous perspective, a transfer is related to a diachronic perspective. In the case of histoire croisée, there may be a variation between the two logics in the analysis depending on the reference between the objects of research. BAUR's (2005) considerations are helpful here as they offer a concrete methodological approach to the interrelationship between past, present, and future. In her work on Verlaufsmusteranalyse [social pattern analysis], BAUR encouraged the creation of an Ereignismatrix [event matrix] in the process-oriented analyses:

"The basic task consists of compiling data in such a way that all events or actions required for data analysis are precisely dated and ordered chronologically, spatially and in terms of content and of level of analysis. I call such a data set [...] 'event matrix'. An event matrix can be a simple spreadsheet, a complex database or even a networked collection of texts. In order to be able to create the event matrix at all, it is necessary for researchers to know exactly which time layers, action spheres, analysis levels, and spaces they are addressing with their research question" (p.113). [30]

This enables researchers to structure their data sets and keep track of events. With the help of the matrix, they should be able to compare the results from different columns of the event matrix with each other:

"Researchers submit the variable-related approach to a temporal comparison. By stringing together cross-sections of single moments in their mind, they move on to longitudinal analysis. They can determine whether ratios, the composition of dominant characteristics, etc. change. [...] [Researchers can also] compare the results of different rows of the event matrix with each other. In doing so, researchers compare different case histories with each other. This way of reading the event matrix is typical for sequence analysis" (p.122). [31]

This approach makes it possible to systematically investigate complex, process-related issues. However, it can also be disadvantageous in terms of compartmentalizing the facts and hiding their relationships to each other. This brings me to the fifth methodological dimension of histoire croisée, namely that of interactions between objects of comparison. The strength of the approach lies in directing the focus to precisely this point.

"An additional difficulty stems from the interaction among the objects of the comparison. When societies in contact with one another are studied, it is often noted that the objects and practices are not only in a state of interrelationship but also modify one another reciprocally as a result of their relationship" (WERNER & ZIMMERMANN, 2006, p.35). [32]

Thus, this raises the question of how both (forming) objects are related and correlated. The aim is to follow the back-and-forth between the cultures studied and to consider their mutual consequences for one another. In histoire croisée, researchers analyze the role of discourses and institutions, but also the concrete practice of relevant actors as mediators or translators between the cultures subject to research. The approach illuminates the potential (dis)symmetries shaping the relationships between the entities studied (WERNER, 1997). In this sense, the question of reciprocity moves to the center of considerations. WERNER (2007) explained this using the example of scientific exchange between France and Germany in order to emphasize two aspects of the intersection, namely the direction and the weighting, which are to be considered in the analysis:

"On the one hand, the problem of symmetry can be viewed from the perspective of reciprocity. It should be noted that although the transfer of science between Germany and France always took place in both directions during the period in question, the weight and main directions of the transfer constantly shifted, depending on the subject and situation. Even though scientists on both sides were usually involved, reciprocity only existed to a certain extent. Giving and taking, phases of attention to the scientific production of the neighboring country and phases of isolation or ignorance changed frequently. [...] A closer look also reveals that the interweaving is not symmetrical, but rather binds 'unequal' parts together. The corresponding organizations as well as the participating disciplinary communities are rather unequally distributed, the initiatives for contacts and closer connections usually start from one side or the other" (pp.384-385). [33]

2.2.2 Mixed-method research design

How should such an ambitious research approach be executed empirically? Which data are needed or made available in order to reconstruct the sociogenesis of the interdependence or demarcation between the disciplines of architecture and sociology historically? This requires a historical analysis of the longue durée [long-term social processes] in order to identify potential patterns in the sense of "regularities of social action or interactions in groups and the change of these regularities" (BAUR, 2005, p.21). In line with BAUR and ERNST (2011), the following analytical steps are required: The starting point and scope of the analysis must be defined. In my case, the process of the (institutional) disciplinary formation of architecture and sociology in the German-speaking world is an appropriate one. For architecture, the process of discipline formation began between the fifteenth and sixteenth century (KOSTOF, 1977), while, for sociology, this period is deemed as the late nineteenth century (LEPENIES, 1981; MOEBIUS & DAYÉ, 2015; SCHÄFERS, 1995). The process must be subdivided into significant subperiods (HERGESELL, 2018; HERGESELL, BAUR & BRAUNISCH, 2020):

"However, a process-orientation is central to figurational sociology, meaning that researchers have to analyse the sociogenesis of a figuration, a figuration's becoming, change, and ending. Ideally, this would mean that the relation of figuration and individuals is reconstructed at several points in time and linked" (BAUR & ERNST, 2011, p.132). [34]

BAUR (2005, 2017) noted that periodization represents one of the greatest challenges in that it constitutes an essential interpretation of the researcher. The periodization of the interdisciplinary collaboration between sociology and architecture is also one of the contributions of this article, in which the review of different literature makes it possible to determine key elements and turning points in the respective disciplinary figurations. Data should be selected for each subperiod. In my case, lacking other data, I used both the historical literature on architectural research and on the spatial question in sociology as a central source of analysis. Here, I paid special attention to the individual mediators who, as authors, formed an important interface. I also used process-generated data, such as newspaper articles from journals of architecture. [35]

In addition, I conducted qualitative interviews with both active and emeriti "passeurs" between the two fields. Due to the fact that I am currently conducting a scientific ethnographic study within the framework of the interdisciplinary CRC 1265 "Re-Figuration of Spaces" at TU Berlin (MARGUIN, 2021a, 2021b; MARGUIN & KNOBLAUCH, 2021), this university forms a privileged case of field access and is at the center of my investigation. Hochschule für Technik Stuttgart was added as a supplement to the Berlin case based on available sources (GRIBAT, MISSELWITZ & GÖRLICH, 2017). I am aware of the disparity of such a patchy data situation. However, it allows me to formulate initial hypothetical referencing narratives between the disciplines. [36]

3. A Sociogenesis of Referencing Between Architecture and Sociology

In this socio-historical investigation, I address the mutual referencing between the disciplines of architecture and sociology. In other words, I deal with architecture (research) in sociology and sociology in architecture (research) and their interrelationships. I make these references at two levels:

at that of the disciplinary object;

at that of the disciplines themselves. [37]

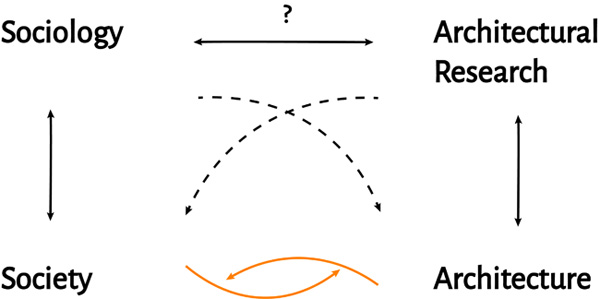

Sociology is the study of society, while architecture (research) is the study of architecture. As a result, it is first necessary to determine the extent to which social facts have played or play a role in architecture (research), or to what extent architectural facts do so in sociology, and how such interests are accompanied by references to the knowledge of the other discipline (be they theoretical or methodological). Furthermore, in this investigation I explore the active participation of architects in the field of sociology, or that of sociologists in the field of architecture (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Instances of multiple referencing between architecture and sociology [38]

Only by taking into account such cross-references, which have shaped the respective epistemic culture of each discipline, is it possible to comprehend the background of the interdisciplinary collaboration between the two disciplines. Analyzing the data collected here leads to the development of a narrative of failure and a double asymmetry that characterizes the rapprochement between the two disciplines. In the historical analysis, the articulative role of urban planning as a discipline can be clearly recognized. [39]

Two subperiods are revealed in the history of the referencing of architecture in sociology, with the spatial turn as a pivot point:

The first subperiod, which extends from the founding of sociology to the 1990s, is characterized by a sporadic and implicit reference to architecture (DELITZ, 2010).

In contrast, the second, starting in the 2000s, points to an explicit reference by sociology to architecture that adopts timid institutional features. [40]

This periodization corresponds to the evolution of the concept of both "space" and "materiality" in the field of sociology. Here, it is important to bear in mind that even though it might increase, the interest shown in architecture within sociology represents a highly specific niche among German-speaking sociologists and has not reached a larger audience (SCHMITZ et al., 2019). Therefore, the next two paragraphs deal primarily with this niche. [41]

3.1.1 Twentieth century: Architecture as a marginal sociological topic

DELITZ (2009) wrote a comprehensive literature review on how classical authors in German and French sociology treated architecture:

"The history of architectural sociology is quickly told: With the exception of a few approaches critical of architecture and ideology in the 1970s, there was no explicit sociology of architecture. There was no independent discipline, no relevant monographs, no conferences, etc. And this applies above all to classical sociology in the founding phase of this still young discipline" (p.12). [42]

DELITZ's hypothesis was that the subject of architecture is only treated "implicitly" in sociological discourses. DELITZ quoted DURKHEIM and the connection he drew between social morphology and the social substrate (1895), but also his disciple MAUSS, who, in his study of the Eskimo, presented the structuring role of architecture (2008 [1905]). She mentioned LEVI-STRAUSS' study of Bororo society, in which he showed the hierarchical social structure through the spatial arrangement of the village (1958). Beyond the Rhine, SIMMEL stated the following in his studies of the metropolis as a new world, which can be understood as a sociology of the built "skin" of society (1992 [1908]):

"Every permanent socialization is based on a structural 'fixation': architectures are 'pivot points' of social relations, for instance, they perpetuate a religious community. According to Simmel, social superordination and subordination also fundamentally require architecture [Simmel, 1992 (1908), p.472]. Simmel's second, diagnostic perspective can be understood as the sociology of the built 'skin' of society: The specific kind of socialization can be recognized in the architectural form, such as the rationalism of modernism in the straight streets and houses" (DELITZ, 2009, p.14). [43]

The works of ELIAS (2006b [1969]) on Versailles as a mirror of hierarchical society or BENJAMIN (1991 [1982]) on passages as the most important architectural innovation of the nineteenth century and testimony to the latent mythology of a society must also be mentioned in this context. Texts by KRACAUER (1990 [1927]) on the "Weißenhofsiedlung" in Stuttgart, by BLOCH (1995 [1955]) on the Bauhaus, and by PLESSNER (2001 [1932]) on the Bauhaus city of Dessau also exist. What such classical works have in common in relation to architecture is that they understood architecture exclusively as an "expression" or "mirror" of society. [44]

In the second half of the twentieth century, LEFEBVRE (2000 [1974]) with the production of space (also HOERNING, 2021), BOURDIEU (1999 [1993]) with the site effect, and FOUCAULT (1994 [1982]) with the power of space all made their mark, each of them touching on the topic of space and architecture. Although the relationship between the architectural and the social is thought of as more interwoven and relative, the works from this period dealt with the question of space and architecture on a predominantly "metaphorical" level (DELITZ, 2010, p.87). In his literature review on the concept of space in anthropology, NIEWÖHNER (2014) reached similar conclusions: He illustrated how classics of anthropology initially understood space as a "biophysical territory and material living space" (p.15), in other words, as a determining environment—in LEVI-STRAUSS (1958), for example—and how this structuralist and deterministic anthropology metamorphosed into a symbolic and interpretative anthropology in the period from the 1960s to the 1970s and onward. NIEWÖHNER (2014) aptly described the process as a dematerialization of the spatial question, which makes any reference to the constructed merely symbolic: "However, the material of the environment is no longer granted the power of explanation. It appears as a carrier of symbolism and meaning, but no longer contributes to the understanding of human action and cultural orientation" (p.17). In summary, DELITZ (2009) and NIEWÖHNER (2014) put forward a similar thesis, namely that social research, be it in sociology or in anthropology, has not addressed materiality for quite some time and has therefore shown little fundamental interest in architecture. Some authors attribute this lack of interest to a certain "anti-aestheticism":

"The fact that there was no systematic architectural sociology may perhaps have been due to the fact that sociology (as the Freiburg sociologist Wolfgang Essbach puts it) saw itself taken by art and technology into a 'jam'. For Essbach, this is the reason for a far-reaching course-setting of sociology, in which all 'things' are banned from the area of the social and the view of sociology. Sociology gives itself its basic concepts in an 'anti-aesthetic and anti-technical attitude'. It purifies the actual social from things (and thus also from architecture) by grasping it as pure interaction, interrelation, communication" (DELITZ, 2009, p.12). [45]

Thus far, such a narrative helps to understand the absence of architecture in sociology up to the spatial turn. However, it conceals some challenges: Where should the contributions from the field of urban sociology be located? Do they, perhaps, instead form an interface between the fields of architecture and those of sociology or planning? This is certainly the case from the 1970s onward, when an increasing number of sociologists sought to contribute to urban analysis parallel to the development of critical geography. In this context, a rapprochement developed between sociologists and architects, and the discipline of urban planning emerged as a result (I will elaborate on this in the following section). However, this approach remains very local, anchored in the field of urban planning, and (for now) not rewound into the general field of sociology. Here, it would be interesting to explore the question of the extent to which this type of author from the field of sociology is marginalized. An asymmetrical relationship can be assumed in the connection between the fields, to which I will return later. [46]

3.1.2 Formation of differentiated subdisciplines: The birth of spatial, architectural, and planning sociology

Since the year 2000, some scholars in sociology have embraced the concept of space and placed it at the heart of their social questioning (LÖW, 2001). A shift in focus has occurred, which is described as a spatial turn (LÄPPLE, 1991; LÖW, 2017). Parallel to this—the discourses promote each other—one can observe a material turn (MILLER, 2005) in some subfields of sociology. These turns represent the start to the second subperiod of a new referencing to architecture in sociology. This new relationship can be observed both at an epistemic and at an institutional level. [47]

At the epistemic level, the change can be identified in the development of a new concept of space, which is now thought of as relational (LÖW, 2001). With her theory of a relational space, LÖW focused, on the one hand, on the physical-material arrangement of objects, artifacts, and persons leading to spatial constitution (spacing) and, on the other, on the process of synthesis, in which the spatial arrangement is synthesized cognitively. This theoretical impetus has led to many studies in which the very constitution of space is observed, with a view to architecture (BAUR & HERING, 2017; EDINGER, 2015; FRANK, 2009). Parallel to this, there is also talk of a material turn (MILLER, 2005), which makes a more obvious reference to architecture: "Research is seeking through a revival of the processual, relations and practical-theoretic thinking of the early twentieth century to reintroduce materiality and thus also material space into social and cultural analyses" (NIEWÖHNER, 2014, p.19). Buildings are not only understood as symbol carriers, but are also included in the analysis as interacting objects: "In this explicit sociology of architecture, the built environment itself is primarily the object of sociological observation: in form, phenomenality, materiality, expressivity; and this always with regard to society and social life" (DELITZ, 2019, n.p.). [48]

The cultural and sociology of knowledge discourses that have developed around the Darmstadt School (BERKING, 2012; BERKING & LÖW, 2008; FRANK, 2009; STEETS, 2015) gradually referred to architecture and the built environment in an increasingly explicit manner, as did the actor-network theory (ANT) discourses (ASH, 2016; FARÍAS & WILKIE, 2016; YANEVA, 2009). Interestingly, the (classical) critical, urban-sociological discourses, which stand in line with HÄUSSERMANN, KRONAUER, and SIEBEL (2004), continue to eschew any references to architecture or to the built environment—which actually still represents the mainstream in German-speaking sociology, where space is understood as a social space and materiality is not addressed (SCHMITZ et al., 2019). [49]

At the institutional level, there are timid signs of a process of institutionalization manifesting itself through the formation of new subdisciplines. From the two sections of the German Sociological Association—"Urban and Regional Sociology" and "Cultural Sociology"—the Working Group on Sociology of Architecture was founded in 2007, which has since organized annual workshops and conferences. In this context, a network of young urban sociologists, spatial sociologists, architectural sociologists, and scholars from other social science disciplines was established in 2008 ("City, Space, Architecture. Sociological and Social Science Perspectives") (DELITZ, 2019). The working group maintains a media presence via an extensive website with literature, announcements, etc. In the last two decades, several chairs with an explicit spatial reference have also been renamed or newly established—at TU Berlin and TU Darmstadt, for instance. It is questionable whether this cautious institutional development will be consolidated. Sociology of architecture remains a niche subject within German-language sociology. For the permanent formation of a (new) subdiscipline, much more is needed (HEILBRON, 2004):

the formation of an intellectual practice with disciplinary aspirations;

the creation of chairs, journals, and professional associations at the institutional level;

the elaboration of a narrative on the history of the discipline. [50]

In the case of architectural sociology, no discursive apparatus, such as a journal, exists, and, above all, there is no critical mass of active researchers. It is worth pointing out that the position of architecture in mainstream sociology constitutes a research gap that still needs to be addressed. [51]

3.2 Sociology in architectural research

In order to reconstruct the sociogenesis of the interdependence or demarcation between the disciplines of architecture and sociology, I will now look at how sociology has been historically referenced in architectural research: To what extent have social facts played or continue to play a role in architectural research? Were or are sociologists to be found in the field of architecture? First of all, a note on terminology: In this section, I address the academic discipline of architecture and, in particular, the place of sociology within that discipline’s research activities. In this sense, the term "architectural research" implies this narrow focus, which is, moreover, increasingly used within the discipline for the purpose of the scientific method (KURATH, 2015). However, it would be anachronistic to speak of "architectural research" for the earlier phase. Therefore, in the following argumentation, I will use the term "architecture" instead. [52]

The starting point of my study was the disciplinary formation of architecture during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries (KOSTOF, 1977), which, as a new division of labor between architects and building guilds, gave architects a professional specification via the maîtrise of drawing (FORTY, 2000). Interpreting the collective historical literature, the secondary sources, and the expert interviews leads to the differentiation of five subperiods in the referencing of sociology in architecture. The hinge points follow a periodization common to the history of architecture (NERDINGER, 2012). [53]

3.2.1 Prior to the twentieth century: A dearth of social facts

Historically, architecture was located between engineering sciences and art:

"In the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, following the example of what happened in Italy, the Fine Arts were gradually associated with the Liberal Arts: the architect thus acquired the status of intellectual and artist. The architect is therefore both a scientist, through his knowledge of geometry and engineering, and a humanist, through his knowledge of ancient tradition. It is important to note that it is expressed in the drawing which, for Alberti, is the link between architecture and mathematics" (JACQUES, 1986, p.3). [54]

The controversy surrounding the classification of architecture "between academies and polytechnics" (DOLGNER, 2013, p.137) has been closely connected to the academicization of the subject. In the nineteenth century, this polarization was intensified by industrialization, the acceleration of knowledge production, and the scientification of the construction sector. At the same time, it was problematized as an urgent, indissoluble interdependence:

"Without scientific direction, the artist falls into the daring and the adventurous; without the artist's eye and feeling for art, the scholar escapes the material for contemplation, and the sensual imagination and representation are also lacking" (PHILIPP, 2012, p.124). [55]

In this dual structure between beauty (the artist) and utility (the engineer), the discourse developed around the task of architecture (JACQUES, 1986). Until the beginning of the twentieth century, no reference was made to the "social" or to "society."

"The description of the social had been less of a problem in the nineteenth century, mainly because architects and critics had had fewer aspirations for a 'social' architecture. Apart from the limited discussions that took place round concepts of utility, convenience, and 'fitness', [...] the principal nineteenth century critical theme connecting architecture to social relationships concerned the quality of labour that went into making works of architecture. [...] Architecture was the embodiment of work, and the extent to which it expressed the vitality and freedom of those who had built it was the measure of its social quality" (FORTY, 2000, p.104). [56]

Until the twentieth century, architects therefore generally thought that the social quality of architecture lay in its production, in the particular quality of the productive relations between the workers involved in its execution. Thus, the social was not thought of in terms of the people who used and experienced architecture, but far more in terms of those who created it. [57]

3.2.2 1910s-1960s: The architect as a social engineer

From the early twentieth century onwards, isolated voices from the field of architecture became audible in reaction to the acute problem of pauperization in the large cities. Architects gradually felt mobilized by a social task:

"Where architectural modernism diverged from nineteenth-century ideas about the social content of architecture was in looking for social expression in its use, as well as in its production. [...] The ideal raised by European modernism was that architecture might give expression to the collectivity of social existence, and more instrumentally, improve the conditions of social life" (p.105). [58]

Architecture and the city are a "perpetual laboratory" (DÜWEL, 2012, p.153) in which a new society is created. Early-twentieth-century architects concluded that architecture could shape social conditions. In this respect, designing architecture and the city equates designing society. Social problems can or should be solved by architecture. Against the ruthless, profit-seeking entrepreneurial activity, "[a]rchitects [are] advocates of what is good and true. [...] Better architecture should create a city worth living in and thus a society as peaceful as it is happy" (p.154). This would be an interesting opportunity to continue investigating the extent to which the perception of or interest in the "social question" on the part of architects was also influenced by the sociological Marxist discourses of the time. [59]

Starting in the 1920s, various architectural schools and movements—be it Neue Sachlichkeit [New Objectivity], Neues Bauen [New Building] and Bauhaus in German-speaking countries, or the European movement led by LE CORBUSIER and GROPIUS called the Congrès Internationaux d'Architecture Moderne (CIAM) [International Congresses for New Building]—stood for a new paradigm of architecture and urban design characterized, among other things, by a new relationship to society. This paradigm revealed a shift from architecture as an expression of the individualities of some members of society toward architecture as a representation of society as a whole. Architects were assigned a social responsibility, a social task. This is particularly visible in the Athens Charter, which was drawn up in 1933 at the 4th CIAM in Athens as part of the topic "Functional City" and subsequently published by LE CORBUSIER in 1941. In it, the question is posed as to whether architecture and urban design can respond to the existing chaos in the city, which is expressed in human problems (§71) and which is "based on [the] accumulation of private interests that has grown incessantly since the beginning of the machine age" (§72 of the Charter, LE CORBUSIER, 1984 [1941], p.199):

"The core of the demands was the spatial separation of the four functions housing, leisure, work, and transport in urban planning, i.e., a systematic subdivision of the city into spatially separated functional areas. This objective of a so-called functional city, which had already been taken into account in E. Howard's garden city model, has often led to a rigid allocation of function and space in post-war urban planning" (HEINEBERG, 2017, p.137). [60]

Two clues within the context of my search for possible references to sociological discourses can be discerned here.

The first is the use of the metaphor of the "organism" to designate the city: Is this a reference to contemporary sociological works, such as the perspective of DURKHEIM (1895)? GEDDES was most influential at this time for debates on the city as an organism with his book "Cities in Evolution" (1915), in which he developed his ideas of the city as an organism drawing on knowledge from biology and DARWIN's findings (VERNOOS, 2018).

The second is the implementation of clear methods. The discussions at the 4th CIAM were based on comparative international urban planning. Surveys were carried out in 25 different cities using a standardized template (using the same scale, the same symbols, and the same colors for the same functions) (GEORGIADIS, 2014). [61]

Were sociologists involved? This does not seem to be the case. Instead, the survey was carried out by architects and planners:

"Dutch architect and urban planner Cornelis Van Eesteren was responsible for the working method and the form of the cartographic urban analyses of the fourth congress. [...] He was one of the few trained and experienced urban planners in the organization" (WEISS, HARBUSCH & MAURER, 2014, p.15). [62]

VAN EESTEREN's methods constituted "traditional practices of surveys and town planning exhibitions" (CHAPEL, 2014, p.30). The only innovation that potentially indicated an influence of sociological thinking was the following:

"The architects used a zoning model that was no longer only morphological or functional, that is to say linked to public or private land use, but also social—for it differentiated between the social classes residing in different districts of the city. This social zoning model was implicit in the urban project of modern architects such as Le Corbusier. But as far as we know it had never before featured so explicitly on analytical maps drawn by modern architects" (p.31). [63]

As a consequence, only indirect references to sociological theories and methods can be found within these central movements for the time being. According to FORTY (2000), two theoretical challenges were associated with the paradigm of architecture shaping society. The first was to identify a conceptualization of society that can be useful for architects:

"Within architectural discourse, the two most regularly occurring conceptions of 'society' have been those contained in the notion of 'community' and in the dichotomy between 'public' and 'private'. The appeal of these to architects over other models of society can be explained by the ease with which they can be given spatial equivalents, thus holding out the prospect for architects and urbanists to evaluate, and even quantify, buildings and spaces in social terms. Other concepts of society—as a nexus of economic relationships, as a dialectic between individuality and collectivity (as in the work of the German social theorist Georg Simmel), or as a structure of myth—were less attractive for architects because they conceived society not as a thing, but as a dynamic, and so were harder to translate into built or spoil equivalents" (p.105). [64]

Concepts embraced by the architects included the community concept of TÖNNIES (1887) and the idea that society consists of communities (DAL CO, 1990 [1982]) and, after the Second World War, ARENDT's dichotomy between public and private (1998 [1958]) and "her views on the demise of the 'public' in political and social existence" (FORTY, 2000, p.105). For both concepts, architects were able to find spatial equivalences quite easily. The second challenge was to find compatibility between the motives of use and those of aesthetics. Undoubtedly, the great merit of modern architects is to transcend the previously established KANTian distinction of aesthetics as a category in which purpose and utility have no place:

"The majority of German aesthetic philosophers succeeding Kant accepted the embargo upon 'use' as constituent of aesthetics judgement. [...] Almost all nineteenth-century architectural theorists within the German tradition treated use as lying outside the aesthetic. [...] The result of this long-running embargo upon purpose and use in the aesthetics of architecture was that when, in the 1920s, architects [...] found themselves wanting to present architectural modernism not as an art dedicated to traditional aesthetic ends, but to social ends, they found the vocabulary of architecture singularly lacking in words to describe what they hoped to achieve" (FORTY, 2000, pp.106-107). [65]

During the 1920s, the advocates of Neues Bauen, such as the Bauhaus members, succeeded in integrating concepts such as "objectivity" and "practicality," which had previously been excluded from the aesthetic judgment. FORTY quoted TAUT (1929, pp.8-9), a representative of Neues Bauen:

"Beauty originates from the direct relationship between building and purpose ('Zweck'). [...] If everything is founded on sound efficiency, this efficiency itself, or rather its utility ('Brauchbarkeit') will form its own aesthetic law [...]. The architect who achieves this task becomes the creator of an ethical and social character; the people who use the building for any purpose will, through the structure of the house, be brought to a better behaviour in their mutual dealings and relationship with each other. Thus, architecture becomes the creator of new social observances ('gesellschaftliche Formen')" (FORTY, 2000, p.108). [66]

The program of such "socialized architecture" (ibid.) came to an end with the collapse of the Weimar Republic and the exile of the representatives of Neues Bauen and the Bauhaus school. Since the 1920s, they had attempted to replace the prevailing history of building forms grounded in art history with "plan history," which combined architecture with sociology and construction engineering (TEUT, 1967, p.11). With their exile, these efforts ended and the idea of plan history was not further developed. During the Nazi era, architecture took a traditionalist turn (ibid.). The discipline gained a prominent position within the German system of science and German society because of its important political function. Officially, Nazi architects opposed Bauhaus teaching and represented a classicist style—for political buildings—or functionalist style—for industrial, army, and sports buildings (WEIHSMANN, 1998, p.42). Next to the monuments of power and the modest residential and farmhouse buildings based on dead or dying traditional forms, which they conceptualized and rebuilt after the so-called Baufibel [building bible], a central architectural and planning objective was the establishment of a designated Raumforschung [spatial research] or Raumordnung [spatial planning] in which (possibly non-university) planners, architects, and sociologists participated (KLINGEMANN, 1996, 2009; MÜNK, 1993). Although the scope of this article is too limited for this purpose, but it would be extremely relevant to take a closer look at developments such as "the eradicating sociology" (ROTH, 1987, p.370) by German Reich sociologist WALTHER, who drew up a social cartography of the Hamburg slum areas in preparation for the social-hygienic redevelopment of areas and its (implicit or unspoken) influence on the urban planning discourses in the post-war period. After the Second World War, architecture was primarily dedicated to the basic provision of housing and workplaces (KORTE, 1986, p.14). Despite the denazification initiated by the Allies and vivid public debates—for example, about the architect SCHMITTHENNER—many former Nazi networks remained stable (DURTH & GUTSCHOW, 1988; NERDINGER, 2009). As architecture historian NERDINGER (2009) wrote:

"In the years 1945 to 1949, planning emerged everywhere in Germany, in which projects and concepts from the Nazi period lived on in more or less clear form. [...] In many offices and bureaus, planning and drawing continued according to the old patterns and building bibles [Baufibel] which was partly due to a continuity of personnel and attitude, but also to the fact that hardly any information about architecture in other countries was available" (p.381). [67]

The International Building Exhibition in 1957—which was directed by Bauhaus architect GROPIUS, who had returned from exile—linked up with the legacy from the 1930s about the functional city and sounded the victory for functional architecture after a decade of discussions and disputes about the principles that should guide the reconstruction of destroyed cities (NERDINGER, 2009). In the case of larger construction projects, it is remarkable how they adhered to the belief that architecture can shape social conditions. It is interesting to note that both architecture and sociology were occupied by social functionalism in the next post-war period. However, depending on the subject, the dominance of their objects is primarily regarded as follows: While architects thought that architecture can shape society, sociologists believed that architecture is the mirror of society. Finally, it is true that even if the architects sporadically made use of social theories and accorded the social question a central position in their practice, no institutional or individual rapprochement between the disciplines existed at the time. The evolution of the term "user" provides an interesting starting point for our analysis in order to understand what role people played for post-war architects. It confirms the professional identity of architects as social engineers who build for, not with, the people addressed by their designs:

"Unknown before about 1950, the term ['user'] became widespread in the late 1950s and 1960s [...]. The term's origins coincide with the introduction of welfare state programmes in Western European countries after 1945. [...] What the 'user' is meant to convey in architecture is clear enough: the person or persons expected to occupy the work. But [...] the 'user' was always a person unknown—and so in this respect a fiction, an abstraction without phenomenal identity. The 'user' does not tolerate attempts to be given particularity: as soon as the 'user' starts to take on the identity of a person, of specific occupation, class or gender, inhabiting a particular piece of historic time, it begins to collapse as a category" (FORTY, 2000, p.312). [68]

Architects built—unreflectedly—for an "average" person who did not even exist, who was projected and imagined from the position of the (bourgeois-educated) architect. This was to change completely from the 1960s to the 1970s and thereafter. Note also that this statement applies only to the Federal Republic of Germany. The developments in the understanding of architecture both in the time of National Socialism and in the GDR remain blind spots in the reconstruction of this narrative. I will close these gaps at a later point in my research. [69]

3.2.3 1960s-1970s: The flowering of socio-critical architecture

Over the course of the 1960s, parallel to social change, architects themselves challenged their own power over society. Not only should architects plan the society of the future, but also deal with society as it stood and reflect on their own roles: "The architect deals with objects of immediate importance for social life and is therefore more 'susceptible' to criticism by the existing society than the free artist or engineer" (POSENER, 1975, p.8). The larger urban projects of modernity, which evinced initial difficulties as far as the development of spatial segregation and demarcation was concerned, were subject to increasing criticism. In his book The Architecture of the City, Italian architect ROSSI (1984 [1966]) sharply critiqued almost all aspects of the Athens Charter, pleading for a different understanding of sociality and society:

"Rossi's critique of 'naive functionalism' is an important part of his argument that the architecture of a city consists of generic types in which its social memory is preserved. [...] [But] function alone is insufficient to explain the continuity of urban artefacts" (FORTY, 2000, p.192). [70]

Social theories were employed to understand the social context. The teachings of the Frankfurt School, and Marxism, provided inspiration, but systems theory and cybernetics proved particularly illuminating (GRIBAT et al., 2017). At the same time, however, pioneers of pragmatic schools such as PRICE or JOEDICKE also moved into the center of the debate, pleading for an action-oriented understanding of the social, understanding architecture as "an active social act of action determined by the interaction of people, environment and technology" (HERDT, 2017, p.286). From today's perspective, they are regarded as pioneers of the ANT and STS approaches currently popular among architects. The use of such—even if heterogeneous—social-theoretical considerations had consequences for both disciplines: firstly of a reflexive nature, and secondly of a methodological one. In fact, awareness of architecture as a social practice that is also socially positioned and must be reflected upon as such was on the rise at that time: "Questioning the social conditions of architecture was the keyword for a way of thinking and an approach to architecture and the city that stigmatized every unfounded design as a one-sided aestheticization and denial of social problems" (HERLE in GRIBAT et al., 2017, p.100). [71]

Against the backdrop of the critical zeitgeist of the 1960s, however, action and, above all, the overriding position of the architects themselves as deus ex machina were sharply criticized and rejected. In the Berlin critical theoretical journal of architecture, ARCH+, the editorial staff's statement from 1975 on an article by POSENER (1975), in which the architect talked about his own bourgeois origins and reflected on them in the analysis, was typical of the period:

"It is also unusual for Arch+ to bring into conversation the significance that such a personal moment has in the discussion about planning practice and theory. We [the editors] want to underline how important it is for materialism to include one's own social situation in the analysis of the circumstances of building and urban planning, precisely because it is the basic for the discussion about the optical perspectives of professional practice in this area. If we understand the debates about this as a movement merely mediated by individuals, the example of Julius Posener characterizes a starting position to be taken seriously" (REDAKTION DER ARCH+, 1975, p.10). [72]

The architects should develop a critical and open approach to their own positionality and thereby be able to put their subjective attitude into perspective. As a consequence, this subperiod was also characterized by methodological debates about the necessary rationalization and scientification of architecture. It was no longer possible to just focus on aestheticization: architecture needed method (KURATH, 2015). This tendency can be observed clearly in the fields of design:

"This also applies to the fields of design and art, in which around 1960 an intensive examination of scientific concepts and supposedly rational, objectifiable working methods took place parallel to the rise of computer-aided information and communication technologies. In this context, the Hochschule für Gestaltung (HfG) Ulm should be emphasized, where an exploitation of scientific knowledge and procedures in design work was encouraged between 1953 and 1968" (MAREIS, 2019, p.325). [73]

Specifically in the field of architecture, this was also tangible among students. Outraged by the evaluations of professors based on aesthetic criteria at the time, students increasingly demanded comprehensible criteria for the evaluation and examination of their projects (GRIBAT et al., 2017, p.63). This socio-critical turn in architecture thus resulted in a certain rapprochement between architecture and sociology. However, this was achieved by incorporating sociology into the field of architecture as an auxiliary science. This approach can be observed at different levels. [74]