Volume 24, No. 1, Art. 5 – January 2023

"Bring a Picture, Song, or Poem": Expression Sessions as a Participatory Methodology

Candice Groenewald & Zaynab Essack

Abstract: Participatory research approaches in which participants are placed at the center of the research have been successfully used to facilitate research engagement and open expression. In this article we describe our experiences of using a novel, hybrid participatory methodology called expression sessions (ES) with adolescents. We specifically explain how the ES method was conceptualized and operationalized and offer reflections on the usefulness of this approach. Our study was implemented through 24 focus group discussions with 144 adolescent participants aged 12-17 years old. We found the ES method valuable to encourage active participation, facilitate open and meaningful expressions, and enhance collaborative reflection. Through the ES approach participants had the freedom to choose their most proficient ways of expression, which facilitated reflection and discussion of issues in new meaningful ways. In this article thus we present an alternative, participatory methodology that can easily be adopted by qualitative researchers and with diverse samples.

Key words: adolescents; focus groups; participatory visual methods; qualitative; thematic analysis; South Africa

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. Conceptualizing the ES Method

3. Operationalizing the ES Method

3.1 Workshopping the ES method

3.2 Gathering expressions and follow-up interviews

3.3 Ethics

4. Reflections on using the ES method

4.1 Active participation

4.2 The expression in the session

4.3 Collaborative reflection

5. Discussion and Conclusion

Appendix A: Guidelines for Expression Sessions and Shortened Discussion Guide

Appendix B: Stepwise Approach to Capture, Analyze and Interpret Data

The value of young people's voices is increasingly recognized in matters that affect them, including in research. Through meaningful engagement of youth the importance of research with rather than research on youth is emphasized—creating a space where power differentials between the researcher and participants are minimized (FOX et al., 2010). Although positivistic, quantitative methodologies have historically been favored, current approaches increasingly acknowledge the value of qualitative methodologies that explore and describe complex phenomena with richness and depth. The use of qualitative research approaches—such as one-on-one interviews and group discussions—have increased in research over time, with a mushrooming of interdisciplinary research across fields—in recognition of the complexity and multifaced nature of human behavior (BOX-STEFFENSMEIER et al., 2022; CURRY et al., 2013). Traditional approaches like interviews and focus groups have significant merit but have been described as boring and repetitive by adolescents (WILSON, CUNNINGHAM-BURLEY, BANCROFT, BACKETT-MILBURN & MASTERS, 2007). As such there is value in adapting these methods to reflect the contemporary modes of communication amongst adolescents and to be engaging and perceived as relevant to adolescents including the use of social media (GIBSON, 2022; WALKER, KING & HARTMAN, 2018) and e-platforms (MASON & IDE, 2014). [1]

Participatory research methodologies offer one such means to enhance empowering participation and to truly engage with young people by foregrounding their knowledge, experiences, and insights on a particular issue (FLETCHER et al., 2016; FOX et al., 2010). Participatory research is a catchall for research approaches (designs, methods, and frameworks) that use "systematic inquiry in direct collaboration with those affected by the issue being studied for the purpose of action or change" (VAUGHN & JACQUEZ, 2020, p.1). This is achieved by recognizing the participant as the expert on their lives and importantly, allowing them space to reflect on the issue of interest at multiple points in the research process. Of priority is the partnership between researchers and participants where research is co-constructed with those with insider knowledge and lived experience (JAGOSH et al., 2012). The participatory outputs (photos, films, poems, etc.) are used by participants to tell their own stories or describe their lived experiences (MITCHELL, DE LANGE & MOLETSANE, 2017), typically in a way that facilitates meaningful discussion that is reflexive and iterative. [2]

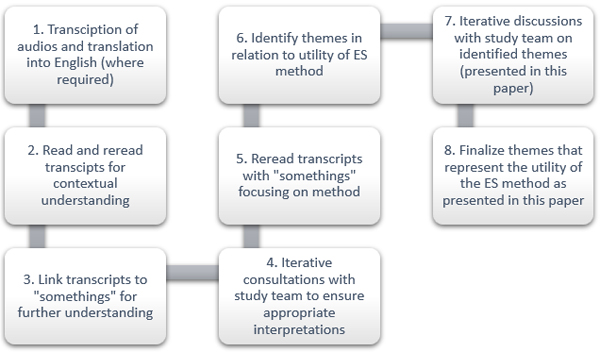

The current paper offers our experiences of using a novel, hybrid participatory methodology, which we call expression sessions (ES) with adolescents. This approach evolved from our research with adolescents over years, and our attempts to use approaches that were engaging and facilitated deeper and meaningful discussions, including about sensitive issues. Drawing on research that explored underage drinking in South Africa, we explain how the ES methodology was conceptualized and operationalized and offer our reflections on the usefulness of this approach. [3]

We begin with an overview of the development of the ES method (Section 2). Following this, we explain how we used this approach in our research (Section 3). We then offer our reflections on using the ES approach (Section 4). We conclude this paper by discussing the ES method in relation to the broader literature on participatory methodologies (Section 5). [4]

2. Conceptualizing the ES Method

The ES approach was developed as part of a mixed methods evaluation study in which we aimed to understand underage drinking and evaluate the feasibility of an underage drinking school-based intervention in low resourced communities in South Africa (GROENEWALD, ESSACK, KHUMALO, NKWANYANA & NTINI, 2018). In this study we used a quasi-experimental design with a repeated-measures approach, incorporating structured surveys and qualitative research at different timepoints. The structured surveys worked well to capture patterns in adolescents' risk behaviors and to assess the feasibility of the intervention. However, for the qualitative component we were aware of the sensitive nature of the research given that we were asking young people to essentially describe illicit behaviors and practices such as consuming and purchasing alcohol. With this in mind, we were interested in approaching the research differently, to identify innovative methodologies that would encourage participation and meaningful engagement in research activities. We also needed to identify tools that were age appropriate and that would facilitate a deeper understanding of underage drinking in these communities. [5]

As a starting point, we reflected on our experiences and consulted the literature to identify a potential research method. Over the past couple of years, we have used various traditional and participatory visual approaches with young people, including surveys (DESMOND et al., 2019; SHAH et al., 2020 ) individual interviews and/or focus group discussions (DESMOND et al., 2019; ESSACK, GROENEWALD & VAN HEERDEN, 2020; NGWENYA, SEELEY, BARNETT & GROENEWALD, 2021), photovoice (GROENEWALD, ESSACK & KHUMALO, 2018; NGIDI, KHUMALO, ESSACK & GROENEWALD, 2018), research diaries (GROENEWALD, 2016), poetic inquiry (VAN ROOYEN, ESSACK, MAHALI, GROENEWALD & SOLOMONS, 2020), cellphilms (NGIDI, MOLESTANE & ESSACK, 2021) and lifegrid research (GROENEWALD & BHANA, 2015). Thus, in thinking through our previous experiences, we considered the strengths and limitations associated with these different participatory methods with the intention to craft out an appropriate methodology. [6]

Photovoice was one of the first approaches we considered for the study. In the 1990s Wang and colleagues developed this methodology to facilitate participant engagement in research through photographic techniques (WANG, 1999; WANG & BURRIS, 1997). Participants are given cameras and asked to capture images that represent their perspectives, experiences, or knowledge in relation to research probes (PEABODY, 2013). The photovoice methodology has pioneered participatory visual research and been found valuable in studies on sensitive issues including HIV/AIDS stigma (MOLETSANE et al., 2007), gender-based violence (MITCHELL, 2011), and sexuality and relationships (HOLMAN, HARBOUR, SAID & FIGUEROA, 2016). In our own photovoice study, we explored adolescents' lived experiences of residing in a semi-rural community. We found this approach useful to unpack issues related to gender-based violence (NGIDI et al., 2018), risk behaviors (GROENEWALD et al., 2018), and prospective hopes and aspirations. The photovoice method not only encouraged open discussion and elicited visual representations, but also "facilitated a collaborative discussion of the challenges in their [adolescents'] communities which produced both individual and shared constructions of the participants' daily lives" (p.S60). [7]

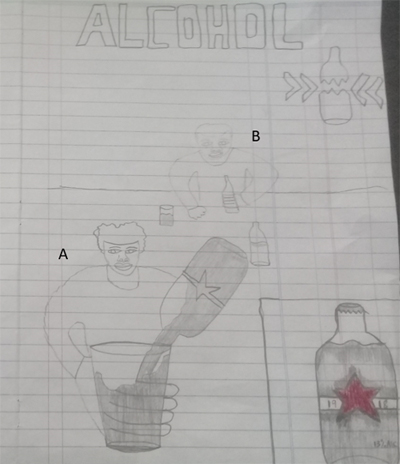

We also considered data collection through written approaches valuable to explore youth identity development and experience such as poetic inquiry or research diaries. Poetic inquiry or research poems for example, is the process of producing poems through research, which are either created by the research participants, the researchers, or collaboratively (FURMAN, LANGER, DAVIS, GALLARDO & KULKARNI, 2007; GLESNE, 1997; VAN ROOYEN et al., 2020). As JOHNSON, CARSON-APSTEIN, BANDEROB and MACAULAY-RETTINO (2017) stated, it aims to "produce meaningful, emotive, and creative texts" (§12) as an innovative representation of participants' experiences. Although still considered a growing body of work, other authors have also used poetic inquiry to explore identity development and enactment with vulnerable groups (FURMAN et al., 2007; NORTON & SLIEP, 2019). In our own work, we have found research poems useful to understand transwomen's identities and experiences of violence, rejection, agency, and social relationships (VAN ROOYEN et al., 2020). Several researchers have also reported on the usefulness of research diaries to gain insights into sensitive issues, including how participants experience and make meaning of their experiences (ALASZEWSKI, 2006; BOSERMAN, 2009; DAY & THATCHER, 2009; HARVEY, 2011; NICHOLL, 2010). Diaries present participants with a private space to talk about their experiences more freely (BOLGER, DAVIS & RAFAELI, 2003), which have been found useful in studies on youth substance use (BOSERMAN, 2009). [8]

Moreover, we have also used retrospective methods such as the lifegrid (BERNEY & BLANE, 1997; BLANE, 1996) to explore adolescent risk behaviors and the impact of these behaviors on parent-adolescent relationships (GROENEWALD & BHANA, 2015). The lifegrid is a visual tool used to construct a chronological outline of a person's lived experience (RICHARDSON, ONG, SIM & CORBETT, 2009; WILSON et al., 2007). Although produced through quantitative studies, qualitative studies have reported on the effectiveness of the lifegrid in promoting participant engagement in research interviews (BELL, 2005; HARRISON, VEECK & GENTRY, 2011; NOVOGRADEC, 2009; WILSON et al., 2007). Our own work has found the lifegrid useful in building researcher-participant rapport and enhancing depth and range of participant recall (GROENEWALD & BHANA, 2015). [9]

Against this backdrop, we were interested in developing a hybrid method that could synthesize different participatory approaches and potentially address some of the limitations of single tools that are generally associated with applicability of the method to young peoples' abilities and comfortabilities to engage. Some participants might not be comfortable or able to express themselves with words (written or spoken) or through visual content (such as photos, videos, or drawings) (BOLGER et al., 2003; GROENEWALD, 2016; NICHOLL, 2010; WOODGATE, ZURBA & TENNENT, 2017). Essentially, we reflected that participants express themselves best through different mediums. In keeping with the participatory perspective, in which we situate participants at the center of the research (BLACKBEARD & LINDEGGER, 2014), we surmised that collating various participatory methods into a flexible, hybrid methodology would encourage participants to actively participate in research. It is through these reflections that the ES methodology was conceptualized. [10]

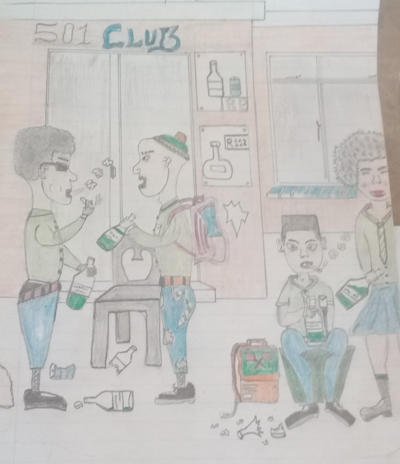

3. Operationalizing the ES Method

The implementation of the ES method was largely informed by the photovoice methodology, in which participants are asked to share their perspectives or experiences using photographs (WANG & BURRIS, 1997). Essential to this method is enhancing participant voice in both understanding social issues and identifying effective solutions to social challenges (MOLLOY, 2007). Adopting this participant-centered approach, we expanded the photovoice technique by encouraging participants to bring "something" rather than only photos or images to tell their stories. The idea of "something" was largely left open; however, we described these as

pictures: self-taken, downloaded or from magazines, staged or spontaneous;

music: including audio or lyrics to a song;

written content: including poems, spoken word poems or any form of written expression; and

art: including self-drawn or photos of drawings, sketches, or artwork. [11]

By expanding how participants could express themselves, we aimed to more closely meet the participants at their most comfortable mode of self-expression, hypothesizing that this would enhance engagement and the richness of discussions. Our intention was to motivate participants to be creative and comfortable in their responses, without feeling pressured to "do it right." [12]

3.1 Workshopping the ES method

Prior to commencing data collection, two training workshops were held. The first workshop was conducted with the research facilitators who collected the data (i.e., "data collectors"). The aim of this workshop was to ensure that the facilitators understood the aim of the study and ES method. Most of our data collectors were experienced qualitative or quantitative researchers, with some having experience in participatory methodologies. Given the innovativeness of the ES approach, we trained data collectors on participatory research principles and practices more broadly, then honed in on the specific approaches that informed the ES method. We engaged the data collectors on the research prompts and revised these as necessary based on their feedback. The following are examples of research prompts that were used:

Please bring no more than two "things" (for example lyrics to a song, a picture that you took from a magazine, a picture that you took yourself, a poem, something you have drawn or artwork that you like) that tell us about what young people (that are about your age) in your school think about alcohol.

Please bring no more than two "things" (for example lyrics to a song, a picture that you took from a magazine, a picture that you took yourself, a poem, something you have drawn or artwork that you like) that would tell us about the drinking behaviors of young people (that are about your age) in this community.

Please bring no more than two "things" (for example lyrics to a song, a picture that you took from a magazine, a picture that you took yourself, a poem, something you have drawn or artwork that you like) that describe why you think young people should not drink alcohol. [13]

A critical component of the training was role-play activities in which facilitators participated as both a data collector and as a mock participant. In this way, facilitators had the opportunity to consider the "somethings" they would share in response to the prompts, gaining insights into the potential experiences of our research participants. The training was a critical component of the process and should be tailored to the skill level of data collectors. [14]

The second series of training workshops were held with our research participants: 114 adolescents attending grades 8 to 12. During the training, the ES method and overall research topic were presented to the participants. Research prompts were shared with the participants after which an interactive role play activity was conducted to explain how the research prompts could be answered. Facilitators provided participants with examples of expressions in response to a different topic to avoid response bias (e.g., responding by using the specific examples provided by the facilitators during the training). Additionally, participants received a printed copy of the research prompts, together with guidelines on how to safely, and ethically, gather their expressions. This included detailed guidance on how to obtain informed consent from third parties (if required). Participants were allowed to participate individually or collaboratively with other participants to gather their expressions. [15]

3.2 Gathering expressions and follow-up interviews

Following the training, participants were asked to gather their expressions (respond to prompts) over a 3-day period. This time period is flexible at the researcher's discretion, but it should be long enough to ensure critical reflection and engagement with the research questions. During this time, the research team remained available to participants to address any queries. Similar to other visual and participatory methods, follow up interviews were conducted with the research participants to discuss their expressions. In our study, these were conducted through focus group discussions (FGDs) that typically consisted of 6 participants. A total of 24 FGDs were conducted with 144 participants. The FGDs also included a semi-structured guide to facilitate the exploration of issues related to research questions in more detail. The FGDs were completed by two members of the research team—one facilitator and one notetaker. [16]

To unpack their expressions, participants were asked to show and describe the expressions they compiled in relation to the research prompts. This process allowed the participants to share their expressions and the meanings they attached to these (see Appendix A). Given the FGD format, other participants were invited to share their thoughts on others' expressions, which further facilitated in-depth intergroup discussions (see next section of paper). Follow up FGDs generally lasted about 45 minutes and were audio recorded with participants' consent. [17]

The study received ethical approval from the Research Ethics Committee of the Human Sciences Research Council in South Africa (ref. no. REC2/22/11/17c). All participants were required to provide written assent and parental consent prior to participating in this study. In the informed consent process, we offered multiple consent options so that a participant could opt in/out of each process separately, including to participate, have their expression data shared in reports and other mechanisms of dissemination, and be audio-recorded. Participants were also required to sign a confidentiality agreement to keep the information discussed during the FGDs private. [18]

4. Reflections on using the ES method

Drawing on extracts from the broader study, this section describes our experiences of using the ES method with adolescents. We specifically focus on the ES method's ability to encourage 1. active participation in research, 2. subjective expressions, and 3. meaningful participant reflection. We also offer some direction for researchers who intend to use the ES approach in future studies. [19]

Following GROENEWALD and BHANA's (2015) example, we use the following conventions to illustrate extracts (quotations): square brackets "[]" contain material provided by the authors for clarification. Ellipsis points "(...)" indicate that the participants' thoughts have trailed off and uppercase letters are used to illustrate emphasis. A pause is illustrated by "(.)," interruptions are indicated by "=," and [...] indicates a break in the conversation. We used the following convention to refer to the participants: P (participant number), M or F (gender), G (grade). [20]

We used thematic analysis to analyze the transcripts and written expressions (poems, music lyrics, other) (BRAUN & CLARKE, 2006) supported through ATLAS.ti 8 (see Figure 1 and Appendix B). Following the approach in our photovoice study (GROENEWALD et al., 2018; NGIDI et al., 2018), the "expressions" were analyzed in relation to how participants made meaning of them through elicitation focus groups. In this way, we prioritized the foregrounding of participants' voice in how their "expressions" were understood and interpreted.

Figure 1: Stepwise thematic analysis approach [21]

Participatory visual methods are valuable because they prioritize participants' perspectives and experiences and encourage participants' subjective voices in (re)presenting their own stories (LUTTRELL, 2010; MITCHELL et al., 2017). In this way, participants are encouraged to actively create and represent their realities. We found that the ES method promoted active research participation. This was facilitated through an open and less prescriptive approach, in which participants were encouraged to bring or share "something" rather than a particular output (e.g., a picture or a poem). Through this flexibility, participants could identify or create any form of expression that best described or represented their experiences or perspectives, and use a mode of expression that resonated best with them. This encouraged participant agency, creativity, and a process of reflection. In their reflections on the methodology, some participants indicated that this open-ended nature of ES allowed them to consider their own skills or abilities in their expressions, simply stating "I have chosen [a] picture because I can't draw" (P3, F, G11). Others mentioned the appropriateness and illustrative properties of their expressions, for example, in the extract below, participants reflect on the spoken word poem (see below) that they shared to describe the reasons why young people should not use alcohol.

"Participant 3 reading the poem:

'Young people.

Young people think alcohol is their best choice.

Young people think that alcohol is the best way to deal with their problems.

They think that drinking makes their alcohol disappear.

They want to make themselves happy.

They try to fit in. They try to be with their friends drinking alcohol.

Young people think alcohol is the best choice.'

I wrote this poem because I wanted to encourage young people who are still at school; those who don't understand that alcohol is not a good thing. I wrote this poem so that I give them the message that alcohol is not a good thing to use for your problems to disappear. Don't think that when you have problems you will use alcohol to solve them. And when you want to be happy you shouldn't use alcohol. There are many things that you can do to become happy. You can do so many things like sports if you can do sports. You can go to church ... alcohol is not the one thing that can make you happy. You can choose good friends and be happy [...] Mostly it's pictures [Most people brought pictures]. I chose to write because I saw that writing was going to be faster, and by writing it will make them [the youth] understand what I am talking about [...]" (P6, F, G11). [22]

Self-expression (in this case through writing) was thus not only about subjective abilities or skills but also involved meaningful reflection to identify the mode of expression that would best enhance participant voice and serve as a useful message to others. This is evident in statements such as: "by writing it will make them understand what I am talking about" and "I wrote this poem so that I give them the message." This in-depth reflection on the wider implications of the mode of expression was also discussed in another FGD where participants used lyrics to a popular South African song to represent adolescents' thoughts on alcohol. For example:

"Interviewer: [...] We gave you 5 questions, right, and with those questions you were supposed to bring maybe a song ... or a picture ... or a poem. We will start with question 1; what do you have for question number 1?

P2: Lyrics to a song.

Interviewer: [...] What is the name of the song?

Participants: Sister Bethina [Laughter]

Interviewer: Sister Bethina. Okay. Can you please read ... paragraphs or 2 verses?

P2: [Singing] Sister Bethina! In the meantime! Oh! Shit! It's happening tonight in the place of the Hibiri, Hibiri, Heh bare sidl' busha bethu! S'phethe nabantwana [we have girls with us]. He bare [when they say] in the meantime. He bare! He bare sidl' ubusha bethu [when they say we are enjoying our youth] [Laughter]

[...]

Interviewer: So, you decided to bring the lyrics to a song and how do the lyrics answer the question that says, 'tell us how young people your age think about alcohol in your school'?

P4: Young people drink alcohol at school because they think they are enjoying their youth. They are enjoying ... yes. [...]

Interviewer: So, with the song and the topic, how do they relate? [...]

P2: The song says, 'we are eating our youth', so these pupils in the schools think that they are enjoying their youth days. Many young people like it [the song] and say, 'Sidl' ubusha bethu' [We are just enjoying our youth]. They are enjoying their youth day.

Interviewer: How are they enjoying it?

P2: Having fun. Controlling our lives. Controlling their [correcting herself] lives, and no one should tell us what we are doing. Drinking ...

P5: There is this line that says, 'Scel' ukubona beer phezulu' [Lift up your beers].

Interviewer: So, this line that says let us see the beer being lifted up=

P5: = That's why many people drink, of course.

Interviewer: So, how did you choose this song; to say this one is very good and will relate with question number 1? How did you arrive at that decision? Yes, p3.

P3: It relates with this theme of alcohol. [...]

P5: This song has a verse that says, 'Khona ozolahla' [then you will throw it away]. It is true because when you are drunk one is going to get lost. [Laughter]

Interviewer: So, yes ... let us talk about this one that will get lost, where is he getting lost to [Laughter]

P2: As it says, 'Khona ozolahla' [then you will throw it away] remember that earlier we said there are girls that mug boys, so there would be one [boy] who would lose control [get very drunk] and they would mug [rob] him" (F, G10). [23]

Like the previous extract, the participants' decision to use lyrics as their expression was intentional and meaningful. This particular song was important to them, not only because of the content, but also because of its high popularity in South African youth culture: "Many young people like it." The lyrics of the song were also used to describe how young people think about alcohol, and references to feeling "free" and "enjoying our youth" [Sidl' busha bethu] were made throughout the discussion. This freedom or feeling of enjoyment was associated with the use of alcohol, where participants felt that the song encouraged drinking behavior: "There is this line that says, 'Scel' ukubona beer phezulu" [Lift up your beers] ... That's why many people drink, of course." Refencing the lyrics, Khona ozolahla, which translates to "then you will throw it away," participants also described the risk associated with alcohol use. Excessive drinking was also considered to increase young people's vulnerability, where participants explained that "when you are drunk, one is going to get lost" and "there would be one who would lose control [get drunk] and they would mug him." [24]

The extracts provided in this section illustrate that the ES method encouraged participant voice by creating a platform through which participants tell their stories as well as encouraging participants to do so in ways that were most comfortable or impactful to them. In this way, participants were active narrators and illustrators of their realities. The open approach applied through the ES method facilitated this, creating a freedom of expression that led to active participation in research activities. [25]

4.2 The expression in the session

In addition to promoting active participation, we also describe the significance of ES in facilitating meaningful expressions. As is evident in the previous section, participants' responses were more than an answer to a question. Rather it represented an in-depth reflection and expression of their realities or perspectives. We offer the following example to illustrate the utility of the ES method in facilitating creative expressions of thought and experiences. [26]

In the FGD below, participants used a collection of poems and self-drawn images to illustrate the impact of alcohol on young people in their community (see Figure 2). Words, through poems, were used to express the devastating and long-lasting impact that alcohol has on youth, while the drawing provided a visual representation of their perspectives. The conversation starts with the participants reading out their spoken word poems, followed by a discussion of the text and drawings:

"P5 [reading spoken word poem 1]:

'Alcohol.

The murder of our community.

The murder to both adults and children.

The destroyer of our youth and mind.

The destroyer of our youth and future.

Alcohol.

The thing that changes one's feelings.

A thing that changes a person's behavior.

A thing that causes car accidents, that causes killing in our community.'

P4 [reading spoken word poem 2]:

'Oh! Drink.

Why do you drink, really?

It's killing our youth meaning. [how youth is defined]

Why do you drink?

Do you wanna get sick?

It causes alcoholism.

It causes sickness.

You get ... you get what I'm saying?'"

Figure 2: Representation of the social impacts of alcohol use

"Interviewer: Thank you. Who can describe these pictures and why you have decided to use them? What do they entail, these pictures?

P1: According to my point of view, this picture [Image 1] explains that many children are orphans because of alcohol. Their parents died and they don't get raised up good [/well/] by the other parents [caregivers]. So, they drink alcohol and try to forget about those bad memories that they have been tortured.

Interviewer: And what have you drawn here?

P6: The thing that we have drawn here is that we want you to realize that alcohol isn't good for our youth. It does kill and [it kills] a lot! Alcohol has been upgraded as it is now in 1 litre. Some things like that ... it does kill our youth because if you improve something in alcohol [make large quantities available], people think alcohol is good. That's what we have drawn here. [...]

P4: Yes, it's like P1 said, this man [referring to the drawing on image x] is like a kid whose parents died because of alcohol and he does think that alcohol is right so, he does drink alcohol too" (M, G10). [27]

Using the poems and drawings, the participants tell the fictional story of a young man in the community whose life has been severely impacted by alcohol abuse. The drawing displayed the intergenerational consequences of alcohol abuse and dependency. This is evident both in the way the "father," who is consuming alcohol, (marked b) is positioned behind the child who is also consuming alcohol (marked a), and participant 4's explanation that "this man [marked 'a' on the image] is like a kid, whose parents died because of alcohol [marked as b] and he does think that alcohol is also right, so he does drink alcohol too" (P4). Through this image, participants capture that social norms in their community perpetuate a drinking culture and that this has significant generational consequences. This is further supported by the poems in expressions such as "Alcohol; the murder of our community, the murder to both adults and children [...], the destroyer of our youth and future [...], that cause killing in our community" (P5). The image and text also display the influence that parental alcohol use has in promoting underage drinking. In this regard, the participants use the second poem to question youth drinking behavior, stating "we want you to realize that alcohol isn't good for our youth. It does kill and [it kills] a lot!" (P6). [28]

The creativity in participants' expressions generated a deeper understanding of their perspectives and experiences related to alcohol. In addition to facilitating greater engagement with research questions, the non-restrictive ES approach also promoted authentic expressions, drawing on the youth's own abilities to articulate and illustrate their realities. Participants were thus able to retain control over how they wanted to respond, while researchers could unpack these subjective expressions during the follow up FGDs. The ES method thus supports LITERAT's perspective that participatory visual approaches, and in our case, participatory expressive approaches, "hold the inherent potential of painting a more nuanced depiction of lived realities, while simultaneously empowering the research participants and placing the agency literally in their own hands" (2013, p.84). [29]

In addition to encouraging vivid expressions, we found that the expression itself (i.e., poems, drawings, lyrics etc.) also facilitated meaningful engagements during the FGDs. In this regard, the expressions worked as "a door opener providing concrete talking points, keeping participants attention, and allow[ing] them to take on the role of experts of their own lives" (WANG & HANNES, 2020, p.1). This is evident in the extracts provided in the previous sections of this paper, where the expressions promoted in-depth discussion of the broader context of underage drinking. The expressions allowed other participants in the group the "language" to share their own stories and perspectives, creating an intersubjective understanding of the issue. We also offer another example here to illustrate this collaborative reflection, where participants discussed the drawing that they shared in response to one of the prompts (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Representation of underage drinking practices

"P5: "Here we have drawn school children. They are in a club. They went to a club, and they are still wearing their school inform, and they are drinking alcohol. They still have their schoolbooks.

“Interviewer: Alright. And how does it answer the question why shouldn't young people drink alcohol? P2?

P2: I think that they should not drink alcohol at the wrong time because they are still young. They should focus on their studies [...]

P1: I think that even when they are in a class, they will be thinking about alcohol then after school they are going to drink. They don't think about schoolwork during school hours.

Interviewer: Oh, and then P3 why should you not drink alcohol? I see these people they are at 501, club!

P3: I see alcohol damages the mind of young people when they are still at school. It makes them to think slowly, and it doesn't only damage the mind, but it can also cause cancer in the body. And in that way, it can make a person to be violent where they can end up in jail. Like this girl that I'm seeing here, she can end up having unwanted pregnancy which will cause poverty as time goes by. And... as we see this one [pointing to picture] his eyes are red. That means he is already sick but not yet aware" (M, G12). [30]

The participants' narratives show that, in addition to illustrating the issue of underage drinking, the expression itself subsequently encouraged the co-production of knowledge and a shared narrative on underage drinking in their community. This is evident in the interactive way that participants discussed their expressions, drawing on the different characters and their own experiences and perspectives to narrate the various consequences of underage drinking. In addition to the participants' spontaneous inputs, the expression also afforded the researcher the opportunity to ask additional questions without interrupting the "flow" of the conversation. The intention is thus not only to understand what the expressions represent, but also how these expressions facilitate discussions related to the broader narrative of underage drinking. This is a particular strength of participatory and visual methodologies, that the expressions themselves both represent and encourage participant narrative as "a vehicle through which further data [are] produced" (SHERIDAN, CHAMBERLAIN & DUPUIS, 2011, p.554, also see WANG & HANNES, 2020). [31]

This paper described our perspectives on using a participatory research methodology called expressions sessions (ES). We found the ES method valuable to encourage active research participation, creative expressions, and meaningful discussions with adolescents. The visual data produced through this approach were particularly revealing of adolescents' attitudes towards underage drinking, and the effects alcohol has on young people in the community. As indicated by WANG and HANNES (2020), "images offer a different way of describing everyday activities and people's understandings of space, place, and relationships" (p.1). For the most part, visual data entailed expressions through drawings, which has been found to be a powerful approach to access adolescents' perspectives and experiences that might be difficult to put into words (GILLIES & ROBINSON, 2012). [32]

Similarly, the textual data, including poems, song lyrics, and expressive "speeches" or essays, offered vivid depictions of underage drinking and the impact of alcohol. Poetry in research has been found to be a powerful tool to capture and represent participants' experiences, especially in relation to sensitive topics (VAN ROOYEN et al., 2020). In our study, the participant-written poems bundled creative thinking and expressive insights, and stood to represent the adolescents' realities (McCULLISS, 2013). In the same way, song lyrics offered an alternative approach to represent shared experiences and perspectives and was generally used to showcase the reasons why adolescents consume alcohol. Music plays an important role in adolescent development and especially social identity (MIRANDA, 2013). Music also has the potential to influence adolescent risk behaviors, including substance use, as song lyrics may convey messages, both overtly and covertly, that encourage the use of substances (ibid.). This perspective was emphasized by the participants in our study. [33]

The value of the ES method thus related to the open approach that we applied, i.e., that participants retained control over how they responded to research prompts. Essentially, participant voice was promoted through participant choice, and this resonated in their reflections about how and why they came to use a particular expression. In this regard, participation is not restricted or dependent on a particular skill or linguistic proficiency but determined by the participant, making this methodology suitable for research with different audiences. In this way, ES is a suitable participatory approach for enhancing participant agency and engagement in the process. This openness/flexibility may also promote active involvement across different socio-economic contexts as participants can creatively draw on materials that they have access to, to tell their stories. It is also likely that the flexibility of the ES method reduced anxieties about "doing it right" or participation fatigue. [34]

The ES method thus extends research beyond traditional interviews, focus group discussions or singular response methodologies. To a large extent, the ES method creates an opportunity to address some of the challenges associated with some of these approaches, especially those related to adolescents' abilities and interests to engage in the research. For example, adolescents may find traditional interviews to be repetitive and boring (WILSON et al., 2007). A key limitation with written approaches like research diaries is the onerousness of diary writing and issues pertaining to participant literacy (BOLGER et al., 2003; GROENEWALD, 2016; NICHOLL, 2010). Similar limitations can be afforded to poetic inquiry where both research participants and investigators are required to have the ability to organize and re-organize words and experiences into expressive poems. Photovoice offers comparable challenges in that some participants might not be "familiar with the artistic or technical aspects of photography" (WOODGATE et al., 2017, §14). Like with many arts-based participatory approaches, ES raises complex ethical issues in relation to confidentiality, anonymity, and reporting—all of which must be navigated starting in the training phase. [35]

That being said, we recognize the value of each of these standalone methodologies, and as described earlier, we have used approaches such as photovoice, research diaries, the lifegrid, poetic inquiry, and traditional interviews in previous studies. Our intention is thus not to devalue the significant contributions any specific participatory approach has had within social science research. On the contrary, we maintain that in adopting the ES method, the strengths of these different approaches are amplified. This is because participants are allowed to express themselves through specific modes freely, with confidence and (potentially) invested interest. The ES method thus embraces BRADY's perspective that "[s]ometimes it is better to have more than a hammer in your toolkit ...There is more than one way to see things, to say things, and therefore to know things, each inviting different points of entry into the research equation" (2009, p.xiii; as cited in BISHOP & WILLIS, 2014, §36). [36]

To conclude, although we would certainly recommend the ES as a valuable participatory methodology, it would be remiss not to describe the potential limitations of this approach. We have used this approach with adolescent and adult samples, and although this methodology was generally well received by adolescents, we have observed mixed outcomes with adults. The ES method is an interactive methodology, which, although enjoyable for younger participants, may be perceived to be too "busy" for adult samples, especially older adults. Our experience with older adults is that they generally engage well with traditional methods, but fewer people come to sessions prepared with expressions. Like other participatory and visual methodologies, ES can be time-consuming because it produces different forms of data (textual, visual, oral) that requires additional efforts to collect, process, and analyze. We are currently conducting additional research with adult samples to assess the suitability of this approach for this population. Furthermore, it is important for researchers to consider whether this method will fit well their topic of inquiry and study timelines. However, we found ES a valuable methodology for engaging young participants on sensitive issues. [37]

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the support of the DST-NRF Centre of Excellence (CoE) towards writing this manuscript. Opinions expressed and conclusions are those of us and are not to be attributed to the DST-NRF CoE in Human Development at the University of the Witwatersrand. We acknowledge our data collection and processing team, including SINANKEKELWE KHUMALO, AKHONA NKWANYANA, MAFANATO GLADYS MALULEKA, THABO GERALD KEETSI, XOLANI NTINGA and KHANYA VILAKAZI. We also thank all stakeholders for allowing access to participants, and the latter who participated in focus group discussions. The findings are based on results from a larger study on underage drinking. Funding for the larger study was provided by Aware.org, however the paper was independently developed. Opinions expressed and conclusions are ours and are not to be attributed to the funder.

Appendix A: Guidelines for Expression Sessions and Shortened Discussion Guide

In Section 1, we present the guidelines provided to the adolescents during the training session, which were designed to assist them while they were gathering their "somethings." Participants could also consult researchers for clarity during the training sessions. In Section 2, we offer a selection of the questions participants were asked about their "somethings" during the focus group discussions.

Section 1: Guidelines for expression sessions given to participants

Thank you so much for agreeing to participate in this study. We look forward to learning more about you and what you think about certain issues that concern young people like you. For this activity we are interested in understanding what you think about alcohol use and what you think young people, like you, need to be able to avoid using alcohol. In order to help you explain your thoughts and experiences, we have developed an activity called "Expression session" in which you have been invited to bring something tangible that best describes your thoughts or experiences. This could include material like the lyrics to a song, a picture that you took from a magazine, a picture that you took yourself, a poem, something you have drawn or artwork that you like. Below we have provided some guidelines that we would like you to keep with you as you are gathering your materials.

Some important things to remember

Make sure you understand the questions.

Make sure you think about these topics before you start taking gathering your material.

Take some time to think about which material would be describe the way you feel about the topics below.

If you decide to take pictures yourself, try not to take pictures of people's faces or things that would show identifiable information of the person or places (for example, the name of a person's tavern or shop).

If you do wish to take pictures of people, please ask them to sign a consent form.

If you do wish to take pictures of places, please ask the owners to sign a consent form.

It is OK to ask someone to take a picture of you.

ENJOY the activity!

Topics for you to respond to (selected)

Please make sure that you respond to ALL the topics below. Tick off the topics you have completed in the space provided below.

|

Topics to cover |

Tick when done |

|

Please bring no more than two things (for example lyrics to a song, a picture that you took from a magazine, a picture that you took yourself, a poem, something you have drawn or artwork that you like) that would best describe who you are. |

|

|

Please bring no more than two things (for example lyrics to a song, a picture that you took from a magazine, a picture that you took yourself, a poem, something you have drawn or artwork that you like) that tell us about what you think about alcohol. |

|

|

Please bring no more than two things (for example lyrics to a song, a picture that you took from a magazine, a picture that you took yourself, a poem, something you have drawn or artwork that you like) that would tell us about the drinking behaviors of young people (that are about your age) in your community. |

|

|

Please bring no more than two things (for example lyrics to a song, a picture that you took from a magazine, a picture that you took yourself, a poem, something you have drawn or artwork that you like) that describe why you think young people should not drink alcohol. |

|

|

Please bring no more than two things (for example lyrics to a song, a picture that you took from a magazine, a picture that you took yourself, a poem, something you have drawn or artwork that you like) that describe what you think needs to be done to stop young people from drinking alcohol. |

|

Thank you for participating!

Section 2: Selected interview questions related to the ES method

Questions for discussion (feedback session)*

Tell us about your picture.

Which question does it relate to?

How does it answer the question?

Why did you take this image/picture/person etc.?

When did you decide to take this picture?

What stood out?

Was this picture/image staged, or freely taken?

Why have you chosen to speak about this picture and not the others you have chosen?

Do you have any other pictures that you would like to share?

Which question was most difficult to capture or respond to with photos?

Why?

Which question was easiest to capture or respond to with photos?

Why?

How do others feel about these pictures?

Individually, which photo(s) best represents you? Which one best represents your reality/condition?

Explain why this particular photo(s) represents you or your reality.

At the end of the discussion for each question

Take note of the similarities and differences between the pictures in terms of content, feeling, space, and representation.

*Notably, it was generally not necessary to ask all questions, but the list was provided, as probes for the data collectors to gain in-depth information on the participants items, descriptions, and interpretations.

Appendix B: Stepwise Approach to Capture, Analyze and Interpret Data

Step 1: Capturing

Following in-person data collection, audio recordings were transcribed and translated into English as required. The recordings were transcribed by the same researchers who collected the data to ensure ease of translation and better annotated transcripts using the conventions described in the paper. Upon completion of transcriptions, transcripts were subject to quality control by the project manager who evaluated the documents for readability, clarity, grammar, and appropriate translation. A conversational style of translation was followed rather than direct translation to ensure appropriate interpretation.

Step 2: Becoming familiar with transcripts

Upon completion of transcripts, researchers read and reread the documents to become familiar with the interviews and craft out any clarifying questions for data capturers. Where content was unclear, researchers consulted with the project manager and team to ensure in-depth understanding and contextual interpretation of the adolescents' narratives.

Step 3: Linking transcripts with "somethings"

During data collection, researchers linked participants' "somethings" with their interview audios by using participant numbers. This was an important step in the process to ensure better management of data during the capturing and analysis phase. For example, the audio for focus group 2 would be linked to all the "somethings" produced by the group, whereas in the transcript, participant numbers would be used to indicate the person(s) who reflected on the item(s) brought. Content was also stored in computer files by school grade of participants, gender, and group number, making it easy to locate.

Following the initial read of the transcripts during Phase 2, transcripts were reread together with the "somethings" to understand participants' description and interpretation of the items they brought. Here we were interested in understanding their alcohol use perceptions, behaviors, and practices, while also assessing how the method was operationalized.

Step 4: Conducting iterative team consultations

During this step, researchers conducting the analyses consulted with the study team to confirm whether content was appropriately understood and interpreted. This offered a space to also pose questions for clarification to the data collectors and for data collectors to add details to transcripts (as shown in the paper) to enhance the readability of the transcripts. For example, descriptions were added in square brackets "[ ]" or comments were offered for clarification.

Steps 5-8: Rereading transcripts with "somethings" focusing on method and identifying themes

While we listed these steps separate in the graph, Steps 5 and 6 occurred simultaneously. Here, we reviewed the transcripts with a particular focus on determining how the method worked, i.e., what kind of content was produced and how this approach allowed adolescents to express their views and experiences in authentic ways. Again, this was an iterative process between researchers and the project team, with discussions taking place to ensure that narratives were adequately understood and themes appropriately represented the focus group discussions. The final list of process-related themes was then developed as presented in Section 4 of the article.

Alaszewski, Andy (2006). Using diaries for social research. London: Sage.

Bell, Andrew (2005). "Oh yes, I remember it well!" Reflections on using the life-grid in qualitative interviews with couples. Qualitative Sociology Review, 1(1), 51- 67, http://www.qualitativesociologyreview.org/ENG/Volume1/Article3.php [Accessed: August 28, 2015].

Berney, Lee & Blane, David (1997). Collecting retrospective data: Accuracy of recall after 50 years judged against historical records. Social Science and Medicine, 45, 1519-1525.

Bishop, Emily & Willis, Karen (2014). "Hope is that fiery feeling": Using poetry as data to explore the meanings of hope for young people. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 15(1), Art. 9, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-15.1.2013 [Accessed: October 7, 2022].

Blackbeard, David & Lindegger, Graham (2014). Dialogues through autophotography: Young masculinity and HIV identity in KwaZulu-Natal. European Journal of Social and Behavioural Sciences, 10, 1466-1477.

Blane, David (1996). Collecting retrospective data: Development of a reliable method and a pilot study of its use. Social Science & Medicine, 42, 751-757.

Bolger, Niall; Davis, Angelina & Rafaeli, Eshkol (2003). Diary methods: Capturing life as it is lived. Annual Review of Psychology, 54, 579-616.

Boserman, Cristina (2009). Diaries from cannabis users: An interpretative phenomenological analysis. Health: An Interdisciplinary Journal for the Social Study of Health, Illness and Medicine, 13(4), 429-448.

Box-Steffensmeier, Janet M.; Burgess, Jean, Corbetta, Maurizio; Crawford, Kate; Duflo, Esther; Fogarty, Laurel; Gopnik, Alison; Hanafi, Sari; Herrero, Mario; Hong, Ying-yi; Kameyama, Yasuko; Lee, Ttia; Leung, Gabriel; Nagin, Daniel; Nobre, Anna; Nordentoft, Merete; Okbay, Aysu; Perfprs, Andre; Rival, Laura; Sugimoto, Cassidy; Tungodden, Bertil & Wagner, Claudia (2022). The future of human behaviour research. Nature Human Behaviour, 6(1), 15-24.

Braun, Virginia & Clarke, Victoria (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77-101.

Curry, Leslie A.; Krumholz, Harlan M.; O'Cathain, Alicia; Plano Clark, Vicki L.; Cherlin, Emily & Bradley, Elizabeth H. (2013). Mixed methods in biomedical and health services research. Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes, 6(1), 119-123.

Day, Melissa & Thatcher, Joanne (2009). "I'm really embarrassed that you're going to read this ...": Reflections on using diaries in qualitative research. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 6(4), 249-259.

Desmond, Chris; Seeley, Janet; Groenewald, Candice; Ngwenya, Nothando; Rich, Kate & Barnett, Tony (2019). Interpreting social determinants: Emergent properties and adolescent risk behaviour. PLoS ONE, 14(12), e0226241, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0226241 [Accessed: October 15, 2022].

Essack, Zaynab; Groenewald, Candice & van Heerden, Alistair (2020). "It's like making your own alcohol at home": Factors influencing adolescent use of over-the-counter cough syrup. South African Journal of Child Health, 14(3), 144-147, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0226241 [Accessed: October 24, 2022].

Fletcher, Sarah; Cox, Robin; Scannell, Leila; Heykoop, Cheryl; Tobin-Gurley, Jennifer & Peek, Lori (2016). Youth creating disaster recovery and resilience: A multi-site arts-based youth engagement research project. Children, Youth and Environments, 26(1), 148-163

Fox, Madeline; Mediratta, Kavitha; Ruglis, Jessica; Stoudt, Brett; Shah, Seema & Fine, Michelle (2010). Critical youth engagement: Participatory action research and organizing. In Lonnie Sherrod, Judith Torney-Puta & Constance Flanagan (Eds.), Handbook of research and policy on civic engagement with youth (pp.621-649). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Furman, Rich; Langer, Carol; Davis, Christine; Gallardo, Heather & Kulkarni, Shanti (2007). Expressive, research and reflective poetry as qualitative inquiry: A study of adolescent identity. Qualitative Research, 7(3), 301-315.

Gibson, Kerry (2022). Bridging the digital divide: Reflections on using WhatsApp instant messenger interviews in youth research. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 19(3), 611-631.

Gillies, Val & Robinson, Yvonne (2012). Developing creative research methods with challenging pupils. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 15(2), 161-173.

Glesne, Corrine (1997). That rare feeling: Re-presenting research through poetic transcription. Qualitative Inquiry, 3(2), 202-221.

Groenewald, Candice (2016). Mothers' lived experiences and coping responses to adolescents with substance abuse problems: A phenomenological inquiry. Doctoral thesis, psychology, University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, https://researchspace.ukzn.ac.za/handle/10413/14929 [Accessed: October 24, 2022].

Groenewald, Candice & Bhana, Arvin (2015). Using the lifegrid in qualitative interviews with parents and substance abusing adolescents. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 16(3), Art. 24, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-16.3.2401 [Accessed: October 15, 2022].

Groenewald, Candice; Essack, Zaynab & Khumalo, Sinakekelwa (2018). Speaking through pictures: Canvassing adolescent risk behaviours in a semi-rural community in KwaZulu-Natal. South African Journal of Child Health, 12(2, Suppl.1), s57-s62, https://journals.co.za/doi/pdf/10.7196/SAJCH.2018.v12i2.1514 [Accessed: October 24, 2022].

Groenewald, Candice; Essack, Zaynab; Khumalo, Sinakekelwe; Nkwanyana, Akhona & Ntini, Thobeka (2018). A qualitative report on learners' experiences and perceptions of the "It starts today" intervention. Johannesburg: AwARE.org.

Harrison, Robert; Veeck, Ann & Gentry, James (2011). A life course perspective of family meals via the life grid method. Journal of Historical Research in Marketing, 3(2), 214-233.

Harvey, Laura (2011). Intimate reflections: Private diaries in qualitative research. Qualitative Research, 11(6), 664-682.

Holman Emily; Harbour Catherine; Said, Rosa & Figueroa, Maria (2016). Regarding realities: Using photo-based projective techniques to elicit normative and alternative discourses on gender, relationships, and sexuality in Mozambique. Global Public Health, 11(5-6), 719-741.

Jagosh, Justin; Macaulay, Ann C.; Pluye, Pierre; Salsberg, Jon; Bush, Paula L.; Henderson, Jim; Sirett, Erin; Wong, Geoff; Cargo, Margaret; Herbert, Carol P.; Seifer, Sarena D.; Green, Lawrence W. & Greenhalgh, Trisha (2012). Uncovering the benefits of participatory research: Implications of a realist review for health research and practice. The Milbank ´Quarterly, 90(2), 311-346.

Johnson, Helen; Carson-Apstein, Emily; Banderob, Simon & Macaulay-Rettino, Xander (2017). “You kind of have to listen to me”: Researching discrimination through poetry. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 18(3), Art. 6, http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-18.3.2864 [Accessed: October 24, 2022].

Literat, Ioana (2013). "A pencil for your thoughts": Participatory drawing as a visual research method with children and youth. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 12(1), 84-98, https://doi.org/10.1177/160940691301200143 [November 15, 2015].

Luttrell, Wendy (2010). "A camera is a big responsibility": A lens for analysing children's visual voices. Visual Studies, 25(3), 224-237.

Mason, Deanna Marie & Ide, Bette (2014). Adapting qualitative research strategies to technology savvy adolescents. Nurse Researcher, 21(5), 40-45.

McCulliss, Debbie (2013). Poetic inquiry and multidisciplinary qualitative research. Journal of Poetry Therapy, 26(2), 83-114.

Miranda, Dave (2013). The role of music in adolescent development: Much more than the same old song. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 18(1), 5-22.

Mitchell, Claudia (2011). What's participation got to do with it? Visual methodologies in "girl-method" to address gender-based violence in the time of AIDS. Global Studies of Childhood, 1(1), 51-59, https://doi.org/10.2304/gsch.2011.1.1.51 [Accessed: September 20, 2021].

Mitchell, Claudia; De Lange, Naydene & Moletsane, Relebohile (2017). Participatory visual methodologies: Social change, community and policy. New York, NY: Sage.

Moletsane, Relebohile; de Lange, Naydene; Mitchell, Claudia; Stuart, Jean; Buthelezi, Thabsile & Taylor, Myra (2007). Photo-voice as a tool for analysis and activism in response to HIV and AIDS stigmatisation in a rural KwaZulu-Natal school. Journal of Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 19(1), 19-28.

Molloy, Jennifer (2007). Photovoice as a tool for social justice workers. Journal of Progressive Human Services, 18(2), 39-55.

Ngidi, Ndumiso; Khumalo, Sinakekelwe; Essack, Zaynab & Groenewald, Candice (2018). Pictures speak for themselves: Youth engaging through photovoice to describe sexual violence in their community. In Claudia Mitchell & Relebohile Moletsane (Eds.), Youth engagement through the arts and visual practices to address sexual violence (pp.81-99). Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

Ngwenya, Nothando; Seeley, Janet; Barnett, Tony & Groenewald, Candice (2021). Complex trauma and its relation to hope and hopelessness among young people in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Vulnerable Children & Youth Studies, 16(2), 166-177.

Ngidi, Ndumiso; Moletsane, Relebohile & Essack, Zaynab (2021). "They abduct us and rape us": Adolescents' participatory visual reflections on their vulnerability to sexual violence in South African townships. Social Science and Medicine, 287, 114401, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114401 [Accessed: October 15, 2022].

Nicholl, Honor (2010). Diaries as a method of data collection in research. Qualitative Methods, 22(7), 16-20.

Norton, Lynn & Sliep, Yvonne (2019). #we speak: Exploring the experience of refugee youth through participatory research and poetry. Journal of Youth Studies, 22(7), 873-890.

Novogradec, Ann (2009). The lifecourse on esophageal cancer patients traced by means of the lifegrid. Poster presented at Conference on Health over the Life Course, Ontario, Canada, October 14-16.

Peabody, Carolyn (2013). Using photovoice as a tool to engage social work students in social justice. Journal of Teaching in Social Work, 33(3), 251-265.

Richardson, Jane C.; Ong, Bie; Sim, Julius & Corbett, Mandy (2009). Begin at the beginning ... Using a lifegrid for exploring illness experience. Social Research Update, 57, 1-4, http://sru.soc.surrey.ac.uk/SRU57.pdf [Accessed: January 25, 2014].

Shah, Seema; Essack, Zaynab; Byron, Katherine; Slack, Catherine; Reirden, Daniel; van Rooyen, Heidi; Jones Nathan & Wendler, David S. (2020). Adolescent barriers to HIV prevention research: Are parental consent requirements the biggest obstacle? Journal of Adolescent Health, 67(4), 495-501.

Sheridan, Joanna; Chamberlain, Kerry & Dupuis, Ann (2011). Timelining: Visualizing experience. Qualitative Research, 11(5), 552-569.

Van Rooyen, Heidi; Essack, Zaynab; Mahali, Alude; Groenewald, Candice & Solomons, Abigail (2020). "The power of the poem": Using poetic inquiry to explore trans-identities in Namibia. Arts & Health, 13(3), 315-328.

Vaughn, Lisa & Jacquez, Farrah (2020). Participatory research methods—Choice points in the research process. Journal of Participatory Research Methods, 1(1), 1-13, https://doi.org/10.35844/001c.13244 [Accessed: October 15, 2022].

Walker, Meaghan; King, Gillian Allison & Hartman, Laura R. (2018). Exploring the potential of social media platforms as data collection methods for accessing and understanding experiences of youth with disabilities: A narrative review. The Journal of Social Media in Society, 7(2), 43-68.

Wang, Caroline (1999). Photovoice: A participatory action research strategy applied to women's health. Journal of Women's Health, 8(2), 185-192.

Wang, Caroline & Burris, Mary Ann (1997). Photovoice: Concept, methodology, and use for participatory needs assessment. Health Education & Behavior, 24(3), 369-387.

Wang, Qingchun & Hannes, Karin (2020). Toward a more comprehensive type of analysis in photovoice research: The development and illustration of supportive question matrices for research teams. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 19, 1-15, https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406920914712 [Accessed: October 15, 2022].

Wilson Sarah; Cunningham-Burley, Sarah; Bancroft, Angus; Backett-Milburn, Kathryn & Masters, Hugh (2007). Young people, biographical narratives and the life grid: Young people's accounts of parental substance use. Qualitative Research, 7(1), 135-151.

Woodgate, Roberta L.; Zurba, Melanie & Tennent, Pauline (2017). Worth a thousand words? Advantages, challenges and opportunities in working with photovoice as a qualitative research method with youth and their families. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 18(1), Art 2, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-18.1.2659 [Accessed: October 15, 2022].

Candice GROENEWALD is chief research specialist at Human Sciences Research Council of South Africa, an honorary research associate in the Psychology Department at Rhodes University and lecturer as part of the South African Research Ethics Training Initiative (SARETI) at the University of KwaZulu-Natal.

Contact:

Candice Groenewald (corresponding author)

Human and Social Capabilities Division

Human Sciences Research Council

Durban Regional Office

The Atrium, 5th Floor, 430 Peter Mokaba Ridge, Berea, 4001, South Africa

E-mail: cgroenewald@hsrc.ac.za

Zaynab ESSACK is chief research specialist at Human Sciences Research Council of South Africa, an honorary research fellow at the School of Law and Honorary Research Associate at CAPRISA, at the University of KwaZulu-Natal. She is also the co-principal investigator of the South African Research Ethics Training Initiative (SARETI) at the University of KwaZulu-Natal.

Contact:

Zaynab Essack

Human and Social Capabilities Division

Human Sciences Research Council

Sweetwaters Road, Sweetwaters, Pietermaritzburg, 4014, South Africa

E-mail: zessack@hsrc.ac.za

Groenewald, Candice & Essack, Zaynab (2023). "Bring a picture, song, or poem": Expression sessions as a participatory methodology [37 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 24(1), Art. 5, http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-24.1.3927.