Volume 24, No. 1, Art. 7 – January 2023

"I Took the Photograph Just to Show You a Little Bit of Perspective": Photo-Elicitation Interviewing With Family Caregivers in the Dementia Context

Angel H. Wang

Abstract: Photo-elicitation interviewing (PEI) is a well-known approach in qualitative inquiry. Yet existing literature lacks sufficient information on participants' perspectives on using photographs to explicate their experiences and ways in which their captured photographs can enhance understanding of the phenomenon under study, especially in the dementia context. In this article, I report on participants' experiences of partaking in the auto-driven approach of PEI in a qualitative descriptive study on family caregiving experiences to a relative living with dementia. Five family caregivers participated in the PEI process and provided 28 photographs that represented their experiences. Using thematic analysis, an overarching theme, facilitated deeper shared understandings was identified, underpinning three main themes about the participants' experiences of PEI, i.e., it 1. promoted more in-depth reflection and new perspectives; 2. enabled richer dialogue; and 3. revealed complex and otherwise hidden experiences. Findings show that PEI is an effective method for researchers to further understand the complex and multifaceted experiences involved in caring for a relative, living with dementia. Thoughtful implementation of using participant-taken photographs in interviews can provide a richer level of understanding and the means through which family caregivers can contribute to meaning-making relevant to the relational aspects of caregiving in the dementia context.

Key words: photo-elicitation interviewing; qualitative inquiry; qualitative methodology; photographs; arts-based research; dementia; family caregivers; mobile apps

Table of Contents

1. Background

2. Methods

2.1 Study design

2.2 Participants

2.3 Data collection

2.4 Ethical considerations

2.5 PEI process

2.6 Trustworthiness

3. Findings

3.1 Overarching theme: Facilitated deeper shared understandings

3.2 Theme #1: Promoted more in-depth reflection and new perspectives

3.3 Theme #2: Enabled richer dialogue

3.4 Theme #3: Revealed complex and otherwise hidden experiences

4. Discussion

5. Implications for Research

6. Conclusion

As a widely known technique employed in qualitative research, photo-elicitation interviewing (PEI) refers to the use of photographs to encourage dialogue (GLAW, INDER, KABLE & HAZELTON, 2017; SHELL, 2014). This method was first coined by researcher and photographer John COLLIER in 1957. COLLIER expanded the work of BATESON and MEAD (1942), who were the first to apply pictures as a research tool in their studies during the 1930s and 1940s, using photographs as an aid in the interview process (SHELL, 2014). COLLIER described the role of photographs as a means to jog memory, stimulate emotions, and facilitate the progression of the interview in a meaningful way. HARPER (2002) further expanded on the implementation of PEI as a research method, contending that human beings inherently respond to images and text in different ways. HARPER argued that images evoke deeper elements of human consciousness than words do because the visual processing components of the brain are older than their verbal processing counterparts. Thus, HARPER emphasized that PEI does not simply elicit more information but evokes a different kind of information. It is these deeper elements of human consciousness that can be useful for the qualitative researcher exploring the experience of dementia, family caregiving and relational caring. [1]

According to many researchers, PEI has a variety of advantages. GENOE and DUPUIS (2013) highlighted that photographs can "capture greater levels of detail about the emotional meaning of experience than words-only data collection" (p.4). COPES, TCHOULA, BROOKMAN and RAGLAND (2018) asserted that PEI can act as a trigger to memory, provide more in-depth meaning to experiences, and can evoke an emotional, multi-layered response in participants. HAGEDORN (1994) further emphasized that photographs invite open expression while maintaining concrete and explicit points of reference, encourage participants to discuss their experience, and elicite a unique return of insights that may otherwise be impossible to obtain with other methods. As such, CLARK-IBÁÑEZ (2004) stressed that photographs can become a medium of communication between researcher and participant with a dual purpose: 1. for researchers to use as a tool to expand on questions; and simultaneously, 2. for participants to provide a unique way to communicate dimensions of their lives and experiences. Consequently, PEI can allow participants to both tell and show their experiences which can produce richer data for analysis (COPES et al., 2018). Furthermore, including those photographs in the dissemination of the research can aid in telling the experiences of the participants, thereby allowing the researcher to better convey the data and the insights gained from them (ibid.). This seems particularly important when the intended audience of dissemination should also include individuals living with dementia or caring for a family member who is experiencing dementia as photographs can transcend written or spoken expressions, enabling insights to be more accessible to this population. [2]

The use of photographs in research is prevalent in the literature (e.g., JENKINGS, WOODWARD & WINTER, 2008; MACDONALD, DEW & BOYDELL, 2020); yet very little of the previous research has specifically explored the experiences of using photographs in interviews from the perspective of participants (see, for instance, EDMONDSON, BRENNAN & HOUSE, 2018; WARNER, JOHNSON & ANDREWS, 2016). Additionally, while researchers have used photographs in studies in the field of dementia research involving persons living with dementia (e.g., EVANS, ROBERTSON & CANDY, 2016; GENOE & DUPUIS, 2013; WIERSMA, 2011), I found only one study in which PEI was used with caregivers of persons living with dementia (RAYMENT, SWAINSTON & WILSON, 2019). RAYMENT et al.'s study explored the experiences of informal caregivers supporting a person living with dementia and similar to other studies, presented reflections of using PEI from the researchers' perspective. [3]

Evidently, the existing literature lacks information on participants' experiences of being involved in research that employs PEI, particularly in the dementia context. This is of particular concern given that the human experience associated with dementia is complex and multifaceted, especially considering the relational embeddedness of care that recognizes the interdependent and reciprocal nature of care in the dementia context (JONAS-SIMPSON, MITCHELL, DUPUIS, DONOVAN & KONTOS, 2022). Relational caring emerged as a philosophy of care in response to the predominant focus on person-centered care that decontextualizes and isolates individuals from their relational world (ibid.). Relational caring respects the importance of person-centeredness, embeds it deeply within relationships, and recognizes that reciprocal relationships are at the core of human wellness (ibid.). Notably, in the context of dementia care, one of the most significant relationships is that of family caregivers with their relative living with dementia. Family caregiving in the dementia context exists within complex, dynamic and multi-layered connections among personal and broader social, cultural and political levels. Thus, it will be useful for qualitative researchers to have information on what family caregivers think about using PEI to explicate such a complex phenomenon. To extend the current literature on PEI into the dementia context, I also explored the perspectives of the participants of engaging in PEI by addressing the following research question: What are family caregivers' perspectives of using photographs as a conduit for explicating their experiences of caregiving and mobile apps use? [4]

In this article, I use data from my graduate thesis research, a qualitative descriptive study of mobile application use (hereinafter referred to as app) in family caregiving in which PEI was employed, in order to explore the participants' experiences of partaking in PEI. In what follows, I first describe my graduate research study from which these data emanate (WANG, NEWMAN, SCHINDEL MARTIN & LAPUM, 2022) (Section 2.1). I then provide an illustration of the process of PEI implemented in the study (Section 2.5). Finally, I present findings regarding the participants' experiences which emerged from using this approach before discussing the benefits of integrating photographs in the research process, including gaining a better understanding of the social worlds of family caregivers in the dementia context (Sections 3-6). [5]

Despite the rapid increase in mobile app use in dementia caregiving, there is scarce research on the experiences of family caregivers of persons living with dementia who use apps to support caregiving activities. Without robust understandings of their user experiences, which encompass their perceptions, experiences, and interactions with the technology, future development of apps will not adequately address the actual needs of these family caregivers. Technologies need to be tailored to end-users' experiences and concerns to promote adoption and buy-in (MAHONEY, 2010). [6]

Since little is known about this phenomenon, I employed a qualitative descriptive approach as described by SANDELOWSKI (2000) to explore the user experiences and perspectives of family caregivers of persons living with dementia on using apps to assist with caregiving activities. Informed by the theoretical tenets of naturalistic inquiry, the overarching goal of qualitative description is to describe and enhance understanding of human experiences that are not commonly described or sufficiently understood at a manifest level (SANDELOWSKI, 2000, 2010) and thus, was the chosen methodology to meet the research purpose. Given that PEI is a method that is participatory, participant-driven and collaborative in nature with the goal to discover different layers of meaning of the participant's experience, it was chosen to not only supplement the qualitative descriptive methodology, but to also correspond with the exploration of user experience component of the phenomenon under investigation. Using this approach, I set out to understand the interplay of family caregiving and apps in the dementia context and the findings addressing this purpose have been published elsewhere (WANG et al., 2022). In this article, I describe participants' experiences while partaking in PEI to uncover how PEI enriched understandings of family caregiving and app use within the dementia context. [7]

Purposive sampling (SURI, 2011) was implemented to recruit participants who met the following criteria: self identifies as an adult child family caregiver (i.e., child or grandchild) of a community-dwelling relative living with dementia; owns a mobile device and has prior experience using apps to assist in caregiving within the last 12 months; and resides in Ontario, Canada. Five participants who identified as female, between the ages of 18 to 35 years old, participated in the study. Two participants identified as a family caregiver to a parent living with dementia whereas three participants were family caregivers to a grandparent living with dementia. The participants used apps on mobile devices such as smartphones, laptops, tablets, and smartwatches. [8]

I conducted two telephone semi-structured interviews with each of the five participants between June 2018 and January 2019. In this population, time and travel constraints are prominent; thus, offering the option of in-person or telephone interview was a strategy to encourage participation (TAO, McROY, KOVACH & WANG, 2016; WHITEBIRD et al., 2011). All five participants chose interviews via the phone. The purpose of the first interview was to gain a rich description of the participant's experiences of using apps during caregiving activities for their relative living with dementia. In the second interview, however, I used PEI to elicit deeper accounts of the participant's family caregiving and app use experiences as well as to understand their perspectives of engaging in PEI. The second interviews ranged from 30 to 60 minutes. [9]

The study was approved by the University's Research Ethics Board. Participants were informed that they could withdraw from the study at any time, to skip any questions, and/or to end the interview at any time. Written consent was obtained from participants to participate in the study and for the use of the photographs they took in any dissemination activities. Each participant was assigned a pseudonym: Abigail, Cassandra, Sierra, Nadia, and Sophia. [10]

I followed the PEI framework as described by BATES, McCANN, KAYE and TAYLOR (2017), which involves the six-step process outlined below. [11]

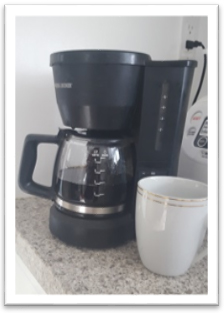

2.5.1 Step 1: Epistemological decision

First, researchers must choose an approach of PEI that is reflective of their epistemological stance (BATES et al., 2017). Since my study is underpinned by constructivism, I chose to adopt the inductive "auto-driven" approach; that is, photographs were taken by participants and used to guide and inform the interview aimed at exploring the meanings behind their photographs (CLARK-IBÁÑEZ, 2004; SHELL, 2014; TORRE & MURPHY, 2015). Furthermore, I employed the open format of the auto-driven approach, whereby participants were asked to provide photographs they felt were relevant to the phenomenon under study (BATES et al., 2017). This approach was most suitable due to a myriad of benefits it provides: 1. It encourages inclusion and active engagement of participants, 2. It promotes participants to reflect on their experiences, 3. It increases participant-led dialogue and subsequently, rich data, as well as 4. It bridges the world of the researcher and the participants (BATES et al., 2017; SHELL, 2014). Notably, in this format, participants are empowered as they are defining what is important by introducing topics and ideas that are meaningful to them, and thereby moving away from researcher-derived content (COPES et al., 2018). This notion is significant given current culture change models associated with dementia care and research, and it fits with the ethos of relational embeddedness of care (DUPUIS, McAINEY, FORTUNE, PLOEG & DE WITT, 2016; JONAS-SIMPSON et al., 2022; RYAN, NOLAN, REID & ENDERBY, 2008). By allowing participants to lead the interview, greater insight could be attained into the experience of dementia within the context of important and significant relationships (RYAN et al., 2008) from the perspective of family caregivers. [12]

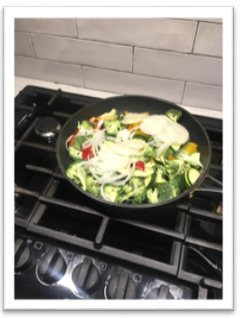

2.5.2 Step 2: Participant briefing

After the first interview, participant briefing was provided which included a detailed explanation of the photography portion of the study and a discussion of ethical considerations associated with PEI. Participants were informed that while pictures of people could be taken, no defining features could be present in the photograph. Participants were also advised that the content of photographs should not depict anything illegal, be deemed sensitive in nature, or contain information that is violating confidentiality clauses for any individual or organizations (BATES et al., 2017). The instructions given encouraged participants to exercise control over what to photograph in a manner that was representative of their experiences as minimal constraints were outlined outside of certain ethical considerations. [13]

2.5.3 Step 3: Photo collection

Participants were asked to use to their own camera-enabled mobile device for photo-taking as this approach reduces logistical issues that often arise in research involving PEI, such as unfamiliarity with other photo-taking devices (TORRE & MURPHY, 2015). They were asked to take at least five photographs that were considered meaningful and representative of their caregiving role and their experiences of using apps in care activities. Participants were given a two-week period to collect, compile, and send their photographs to my email after the first interview. [14]

In terms of practical considerations, all participants indicated that the photography activity was flexible enough to fit within their daily schedules and was suitable for the range of differing skills they possessed. Most of the participants took photographs through their smartphones whereas Cassandra opted to use a professional camera and computer software to edit her photographs. Although participants were initially concerned about the challenges of transforming abstract ideas into photographs, they were all able to provide photographs that they were willing to share and discuss. All participants shared five photographs for the interview, with two participants submitting more than five, resulting in a total of 28 photographs provided. [15]

In the interview, the photographs served as a basis of the discussion to stimulate rich accounts of the participant's user experiences with apps in caregiving. Participants were also asked about their experiences of capturing the photographs and participating in PEI. [16]

For my study, photographs were a conduit and catalyst for discussion; thus, they were not coded or analyzed (BATES et al., 2017). Instead, the dialogue associated with discussing the photographs served as the data set. All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. The thematic analysis approach (BRAUN & CLARKE, 2006; BRAUN, CLARKE & WEATE, 2016) was conducted to identify themes. I read the transcripts multiple times as a way to become immersed in the data and to begin noting initial ideas and codes. I then collated all codes into a separate document to organize similar codes together. I developed a preliminary collection of themes and subthemes after analyzing the connection and relationship between codes, between themes, and between different levels of themes. Themes were identified based on a coherent patterned meaning that had a central organizing concept. Afterwards, I met regularly with my thesis committee members to discuss and build consensus around the emergent coding framework, key themes and corresponding photographs. I reviewed, revised, and refined all codes and themes to ensure all themes were related in a coherent and meaningful way in relation to participants' experiences of PEI. [17]

Given the purposes of my study, dissemination of the photographs in this manner can act as an effective method to bring about meaningful education and change. Visual arts in the form of photography can provoke sensory experiences which can enable individuals to feel and see aspects of the human condition and thus, illuminate dimensions of the human experience (LAPUM et al., 2016). This is particularly important when illustrating the family caregiving and app use experience in the dementia context. Photographs can also make knowledge more accessible to diverse stakeholders and multiple audiences (BOYDELL, GLADSTONE, VOLPE, ALLEMANG & STASIULIS, 2012), which is helpful when disseminating research findings. The inclusion of the photographs taken by participants in my final products and dissemination activities can provide a means to share visually, the experiences and stories of family caregivers. [18]

I followed the criteria to establish trustworthiness as described by SANDELOWSKI (1986) using several strategies. For credibility, I implemented triangulation across data sources (e.g., photo-elicitation interviews, photographs and field notes) to evaluate the congruence of findings among them (ibid.). Additionally, I met with my thesis committee on a regular basis to discuss the analysis process, to ensure findings were grounded in the data and to build consensus around the findings. To address fittingness, I applied purposive sampling to ensure participant representativeness of the phenomenon and I am providing a rich description of the data with direct quotes from participants in this article (ibid.). To achieve auditability, I maintained an audit trail throughout the research process that included research decisions and activities to show how the data were collected and analyzed (ibid.). Finally, to enhance the confirmability of the findings, I engaged in reflexivity when drafting field notes and conducting journaling, where this process enabled reflections on my positionality and preconceptions throughout the research process (COLORAFI & EVANS, 2016). [19]

Based on the participants' descriptions of their experiences of engaging in taking photographs and using them in the second interview, the following overarching theme was identified: Facilitated deeper shared understandings. Underpinning the other themes, this overarching theme captures the central experience and outcome of partaking in PEI. The three themes that form the basis for this overarching theme are as follows: 1. promoted more in-depth reflection and new perspectives; 2. enabled richer dialogue; and 3. revealed complex and otherwise hidden experiences. [20]

3.1 Overarching theme: Facilitated deeper shared understandings

By having a common anchor for discussion, the photographs allowed for reflection and new perspectives, rich dialogue, and complex experiences to emerge, thereby facilitating deeper shared understandings between the participants and the researcher. In this case, that common understanding was on the complexity of family caregiving in the dementia context and I describe in further detail how PEI can produce this central outcome in the following three themes. [21]

3.2 Theme #1: Promoted more in-depth reflection and new perspectives

The act of taking photographs was not just a physical, but also a cognitive, process that involved constructing and reconstructing participants' interpretation of their experience through a visual means. The photo-taking process provided participants with time to reflect and think about what they wanted to capture in the photograph and what they wished to communicate in the interview. Participants described how the photo-taking process enabled them to reflect on thoughts, emotions, and experiences that are often intangible and difficult to articulate. As a result, they cultivated more awareness towards their relationship with their relative living with dementia, their caregiving role, and their use of apps for support. In particular, Sophia opened up about finding peace of mind with her and her family's decision to place her grandfather in palliative care when his health was declining: "I reflected on peace of mind like I wanted to feel that he was okay with what we did for him." She further explained how the photography activity allowed her to reflect in more depth on this challenging, and sometimes suppressed, aspect of her caregiving experience:

"When I look at the photos and I look at the activity, I think what was available at that time. What we could have done for him to improve his quality. We did. I felt like we did it to our best." [22]

As demonstrated in this excerpt, the photography activity supported Sophia to gain a deeper understanding of this difficult caregiving experience by providing her a time of contemplation before the interview, as she was able to prepare for, recall, and share her experiences. In addition, the process of taking photographs to illustrate their experiences enabled participants to perceive things they had always known in a new way. Sierra explained how the photography activity encouraged her to see and reflect upon her experiences as a long-distance caregiver in a different light:

"Being able to reflect on my experience in a different way ... seeing how things around me influence caregiving for my mom ... That aspect of caregiving from afar. It was beneficial to reflect on how it affects me when I'm not at home too. That's something I don't often think about." [23]

In this excerpt, Sierra elaborated on the impact of being a long-distance caregiver on her relationship with her mother when she is away from home. In these examples, the photographs allowed participants to see their own reality with a new lens, resulting in a greater and renewed understanding of their family caregiving experience for a loved one living with dementia. [24]

With regards to their experiences with apps, the photography activity offered the opportunity for more in-depth exploration which gave participants a new sense of appreciation of the impact apps had in their caregiving role and its future use. For instance, Abigail described how she gained additional insight into the role of apps in her caregiving life through the reflecting process associated with photo-taking:

"I was doing all these things that were in the pictures on a weekly basis but I never actually got time to reflect on what I was doing until I took the pictures. I was like oh! I didn't even realize this was what I do every week. It gave me a chance to reflect and gave me an opportunity to see what I am actually doing ... It made me fully reflect." [25]

To further elaborate, by taking the following photograph (Figure 1) of a birthday meal at a restaurant she took her father to, Abigail recognized how she used a transportation app to get both of them there since her father can no longer drive due to dementia: "I used Uber™ to get there and tried to get him a treat ... I didn't realize the connection until I looked at that picture. I realized that I did technically use an app to get there."

Figure 1: Birthday meal [26]

Abigail continued to emphasize that through the reflection afforded from the PEI process, she will now be more cognizant of her use of apps and try to further leverage them in her caregiving role:

"I'm going to be thinking more about what I actually use on a day to day basis. It has created awareness so that way, before I'd just do things and not think about it. But now, I'm going to put more attention on what I'm doing. I'm actually, probably, going start to use apps more if anything and research different apps." [27]

Similarly, Nadia felt that the PEI process encouraged her to reflect to a greater degree on her app use to assist with her caregiving activities and on how she could explore that aspect of her caregiving experiences further in the future:

"It definitely got me to reflect on things and look at different options with apps and technology that I just didn't even think about ... So that's definitely changed it. I didn't even think of it, to be honest, before we had these conversations." [28]

Accordingly, the photo-taking process evoked more reflection as participants were provided an opportunity to deeply contemplate their experiences, thereby resulting in the discovery of new perspectives of their lives and a newfound appreciation of the role apps play in their caregiving experiences. This reflexive effect from PEI led to richer dialogue between the participants and I, the researcher, which is described in the next theme. [29]

3.3 Theme #2: Enabled richer dialogue

Due to PEI, participants in my study led the interview discussion as they had control in deciding what to depict and discuss about their lives. The participants were able to construct meaning unbounded by the confines determined by the researcher and set the agenda for the interview through their photographs. The use of photographs enabled participants to discuss their experiences and the meanings they ascribed to them in a richer manner than had been accomplished in the previous verbal-only interview. For example, as revealed in the following exchange, Sophia recognized that the second interview allowed for photograph-oriented discussions and encouraged richer dialogue—a result she did not anticipate. Sophia remarked, "We've gone into it a lot deeper than I thought I would." She elaborated that "some of the questions really made me touch base on it. Like anything in life, right? If it's not questioned, we really don't think about it ... it's very reflective." [30]

In PEI, participants described what was in the photograph and where, when and why they took the pictures, allowing them to describe on a deeper level the symbolic significance of the photographs. The participants' photographs and accompanying explanations served as venues of metaphorical understandings of their experiences in order for them to explicate the complexities associated with being a family caregiver in the dementia context. For instance, Sierra referred metaphorically to a pair of shoes (as seen in Figure 2) to symbolize her relationship with other caregivers. She used this photograph to illustrate the importance of social connection with others undergoing the same experiences as a family caregiver: "Social media keeps you connected to other people ... they don't have to walk in your shoes because they're already walking in ones that are similar to yours."

Figure 2: Shoes [31]

Bringing together photographs and storytelling has the potential to promote richer and more in-depth dialogue by encouraging participants to consider the circumstances of events in ways they had not thought of before. Sierra described how the conversations associated with the photographs enabled her to recall emotions and ideas in more detail:

"For me, talking out loud helps me work through problems and that's why I was able to learn a lot more and explain myself, like my vague ideas more concisely and clearly and get my point across easier when I was talking. And I was able to share more of how I felt in words." [32]

Evidently, PEI allowed richer understandings to be created and deeper insight to be obtained through the discussions and analysis of photographs taken by participants. The PEI process enabled participants to be the experts on their lives, to use photographs generated by themselves, and to lead the discussion, which materialized in a more comprehensive exploration of their experiences that are most salient to them. In my study, most of the participants leveraged the use of photographs to facilitate deeper discussions about their loved one living with dementia to allow the researcher to better understand who they are as a person. Sophia presented the following photograph (Figure 3) and explanation to exemplify how the photography activity supported her to center on her grandfather's identity and personhood: "It [the photograph] really made me think of him. It really did. No matter where you are in life, what stage you are in life, dementia or not. What you love is what you love."

Figure 3: Coffee [33]

In the same vein, Nadia shared the following photograph (Figure 4) to illuminate her grandmother's love of food: "Food is always the center. When I think of her, I always think of good food, good music, and good company."

Figure 4: Food [34]

The use of photographs encouraged participants to discuss a multitude of areas within their lives, their relationships, and their use of apps, providing additional insight into the multidimensional nature of caregiving in the dementia context. Consequently, a unique glimpse into the person the participants were caring for within the context of relationship, as well as their own experiences of the caregiving life is provided. [35]

3.4 Theme #3: Revealed complex and otherwise hidden experiences

Given that participants determined what is photographed and subsequently discussed, they guided the interview and allowed the researcher to access areas of the participants' experiences that may be taken for granted, unknown or not obvious. Additionally, by going through a process of visualizing their lives and capturing that in images, participants were able to express emotions, complex experiences and tacit knowledge in a way that transcended spoken words. For example, taking photographs prompted Cassandra to uncover the tensions she felt as an "informal" family caregiver when compared to her aunt who is a "formal" caregiver as a Registered Nurse. Cassandra captured a photograph of a page in a book (this photograph is not shown due to copyright infringement concerns) depicting a highlighted quote by RATH (2015): "You cannot be anything you want to be—but you can be a lot more of who you already are." Cassandra explained how she reconciled her identity as an informal caregiver by recognizing that she can still provide quality care for her grandmother with her current abilities:

"I thought yeah, I'm not really a professional caregiver and I'm not the one that's always taking care of her and everything. And I can't be there but I'm also like I'm okay with it. Because I know that deep down, I can just be there for her and care for her." [36]

Photographs enriched participants' verbal expressions of their personal embodied realities as family caregivers, particularly when describing the impact of the changes that have occurred in their lives as a result of dementia. For example, Cassandra explained the feelings and emotions associated with navigating those changes as she discussed the meaning behind this following photograph (see Figure 5):

"It's a bunch of Polaroids and a few of my pictures to represent things that have happened in your life ... I blurred it, I edited it, because it symbolizes that she knows that she has children, grandkids, family and everything. You know how pictures represent memories right? She doesn't really remember much of it. Let's say she looks at a photograph of something in her past, she'll remember it ... but very vaguely. Like she'll forget ... When I look at it, I see myself in her shoes but not to be extreme. Because I don't really know what happens with her, but I see that when I take care of her, she really does get frustrated, not like her usual self."

Figure 5: Blurred pictures [37]

This photograph and Cassandra's explanation shows how she is making sense of the experiences of living with dementia in order to better understand and connect with her grandmother. Similarly, Abigail explained that despite the changes associated with dementia, her father had the tradition of collecting cups (as seen in Figure 6) and emphasized the magnitude of this passion:

"He never forgets to get a cup wherever he travels or when his friends come from different countries. My dad doesn't forget

to request it and to add it to the collection... he forgets a lot of things but that's one thing he doesn't forget."

Figure 6: Cups collection [38]

She highlighted that she captured the photograph of his cup collection to provide an additional visual dimension to ensure a shared understanding: "I took the photograph just to show you a little bit of perspective." These examples demonstrate how greater insight into participants' caregiving experiences was elicited by PEI, and how the photographs became the medium through which they broached the complex emotions behind upholding their loved one's personhood. Seemingly, rather than telling a static verbal story, photographs can help uncover emotions and feelings that are challenging to express in words alone. [39]

For family caregivers who are navigating the complexity associated with dementia, photographs can provide a means to think and express issues that are personal and difficult to articulate. By using photographs to describe abstract ideas, participants were able to poignantly discuss the importance of celebrating who the person was and who the person is now against a backdrop of grief and loss in the dementia context. Nadia described how the process of photo-taking enabled her to see her grandmother in a new light and to further cultivate a deeper meaning around the value of personhood:

"It makes you think. This whole activity. I remember her for how she was a few years ago or it was a gradual but kind of a quick decline ... taking the pictures let's say five years ago, they might be completely different than what I'm taking now so that was something where I felt a little saddened about but not too much. I love who she is now and I loved who she was back then ... It was nice to look at her in different lights like this. It's nice to think about her through this lens, through photography." [40]

Cassandra also described how the photography activity encouraged her to reflect, recall, and discuss the impact of dementia on her grandmother and their relationship as well as her focus on appreciating what they have right now:

"When I was little, I remember she'd take me to school, get me dressed, and everything. And seeing how much that changed, it really affects me but it's life, it happens. So we just have to accept it and work with it ... It makes me so much more thankful that she's still here with us and she still remembers us. I mean one day, I know she'll forget but just right now, we want to cherish her and everything." [41]

As showcased in both excerpts, the photographs evoked emotions and memories that might not have emerged otherwise, allowing deeper insight into complex experiences of participants such as those related to grief, loss, and personhood. Participants also noted that PEI helped unveil aspects of their caregiving experiences and their use of apps that were often overlooked. Abigail recognized an aspect of her caregiving experience that went unnoticed: using apps to communicate and connect with family members to garner social support. Abigail reacted, "Whatsapp™, Facebook Messenger™, these two are used very often ... Oh my, I didn't even think about those apps for caregiving ... I didn't tie that to dementia but I just realized that it could totally be important to that." Further on in the interview, the same form of revelation occurred when Abigail recognized how the photograph prompted her to acknowledge her use of banking apps to assist in caregiving activities which she never considered: "I'm actually surprised right now at myself that I didn't even realize that even the TD Bank™ app can tie into this." Sierra expressed similar sentiments as she recognized, through PEI, the apps that she used to address her caregiving needs that went unnoticed: "I only just realized this as I'm talking to you and thinking about it ... I've never thought about it before." PEI evoked immediate, multifaceted understandings of experiences, which helped participants to recognize aspects of their app use that went unnoticed. Seemingly, subtle and otherwise hidden areas of caregiving can be illuminated through the PEI process. [42]

While PEI has been employed in many studies, there has not been substantial information available in the literature that explicates what participants think about such an approach and the ways it enhances qualitative inquiry. Thus, my work extends previous research as I explored participants' experiences of partaking in PEI and the benefits of this method to help better understand the family caregiving experience and the role of apps when caring for a loved one living with dementia. Additionally, although researchers have focused on the benefits of PEI, my study provides further evidence on how the application of auto-driven PEI enhances our understanding of phenomena, particularly in the dementia context. [43]

Traditional verbal-only interviews can steer the participants in a pre-ordained direction based on what information the researcher decides is of priority and produce answers to researcher's questions and ideas (TORRE & MURPHY, 2015). In contrast, by employing the auto-driven approach in my study, participants were able to choose the information they wanted to share and how they wanted to represent their experiences. In this case, participants and their photographs defined the topics, enabling access to information and experiences that the researcher may not have even thought of. Researchers who used the auto-driven approach in their studies shared similar findings as this method enabled participants to have control over image creation, meaning-making, and construction of their experiences, resulting in richer, more elaborate participant narratives (BURLES & THOMAS, 2014; EDMONDSON et al., 2018; PADGETT, SMITH, DEREJKO, HENWOOD & TIDERINGTON, 2013; SHELL, 2014). RICHARD and LAHMAN (2015) also described this method to create an inherent dimension of participant empowerment as participants made their own photo choices and explained their thought processes behind those choices, thereby making the interview process more participant-directed. This approach aligns with the call for a culture change to move towards relationship-centered care in order to promote more inclusive dementia care practice and research, as well as to focus on the experiences and needs of all involved in the care context, including family caregivers (DUPUIS et al., 2016; RYAN et al., 2008). [44]

My study findings unveiled that the participants were able to fully explore and reflect more in-depth on their experiences through the use of photographs and the ensuing dialogue. Indeed, photographs helped participants present indescribable attributes of situations, phenomena and experiences as well as subtle or overlooked relationships (RICHARD & LAHMAN, 2015). PEI also encouraged participants to discuss things they viewed as normal parts of daily life which often go unnoticed (MARSH, SHAWE, ROBINSON & LEAMON, 2016) and to see things they had always known in a new light. For instance, this was particularly striking when participants, through PEI, came to realize aspects of their caregiving experiences and their use of apps that were overlooked. Furthermore, using photographs to represent and describe caregiving experiences required effort, abstract thinking, and reflexivity from participants and as a result, the reflexive effect of the use of photographs in interviews promoted discussion of thoughts and feelings that had lain dormant (EDMONDSON et al., 2018; MARSH et al., 2016). Through PEI, participants gained a new perspective of their experiences and also a greater appreciation for the role of apps in their caregiving role. This deeper awareness of the relational vastness of the role of apps adds to the current literature on how technology in the form of apps can play a role within relational caring in dementia care (JONAS-SIMPSON et al., 2022). [45]

The photographs were able to stimulate richer dialogue and introduce new dimensions of the participants' experiences that were not previously discussed in the verbal-only interview. This finding aligns with what is reported in other studies (e.g., BURLES & THOMAS, 2014; MARSH et al., 2016; SHELL, 2014; WARNER et al., 2016), which emphasized that the use of photographs as a data generation tool significantly enhanced the communicative and generative aspects of the study; communicative aspects because PEI incited participants to express and convey meaning of their experiences, and generative aspects because new understandings and deeper insight were obtained from participants through discussions and analysis of the photographs (MARSH et al., 2016; SHELL, 2014). Of note, in my study, photographs gave enlightening and personal re-interpretations of the participants' experiences as there were many occasions where seemingly mundane images, such as a pair of shoes and coffee, revealed complex narratives relating to their caregiving experiences and app use. I found that what might become habitual in terms of the day-to-day caregiving for a person living with dementia is highlighted when using photographs; in this sense, family caregivers recognize all of the work involved in their caregiving activities. As such, the photographs enabled participants to communicate their caregiving experiences in an embodied way that differs from the spoken word (MARSH et al., 2016). [46]

The use of photographs helped to further illustrate relational caring by accentuating the interdependent and reciprocal nature of care in the dementia context (JONAS-SIMPSON et al., 2022) by enabling participants to talk about complex, difficult or abstract concepts that may have otherwise remained uncovered or hidden. For example, grief and loss (LINDAUER & HARVATH, 2014) and impact of the effort needed to uphold personhood (HENNELLY, COONEY, HOUGHTON & O'SHEA, 2021) is prominent in dementia care but discussing and explaining the image of blurred Polaroids or of a cup collection provided Cassandra and Abigail with the means to portray their experiences vividly. Evidently, the photographs gave insight into difficult, emotional or otherwise sensitive issues and experiences (CLARK & MORRISS, 2017). Such issues, including grief and loss, decline in health of a loved one, and management of changes associated with dementia as discussed by the participants, can be difficult to articulate. The findings highlighted how family caregivers often used photographs as metaphors for their experiences and with the interactive use of photographs, participants felt it made describing challenging topics easier. In cases such as these, CLARK and MORRISS explained that photographs are beneficial because they can be viewed as a neutral or displaced element around which to express and advance discussion. They act "as a kind of ‘third object' around which participants and researchers can focus" (p.36), making sensitive topics less difficult to discuss and articulate. Additionally, metaphors allow the symbolic representation of an experience or emotion to serve as a "buffer zone" where the family caregiver "may safely dwell in time and space in order to discern and extrapolate the issue that may have been too uncomfortable to broach directly" (SCHWIND, 2009, p.17). [47]

By being a point of commonality, photographs supported rapport-building through bridging the distance between the participants and I as the researcher. This was accomplished as photographs can provide an objective perspective on certain aspects participants might describe as they act as an additional visual dimension of understanding (RICHARD & LAHMAN, 2015; TORRE & MURPHY, 2015). For instance, TORRE and MURPHY (2015) provided an example of a participant describing her house as having a "large room" in a study conducted by STEIGER (2008; as cited in TORRE & MURPHY, 2015, p.15). Without a photograph, this could mean very different things to different people. A photograph ensures that the researcher and the participant understand the size of the "large room" in the same way. Thus, similarly in my study, the photographs in the interviews led the participants and I toward common understandings (GLAW et al., 2017; HARPER, 2002), allowing me as the researcher to connect participants' experiences contextually to their social world (SHELL, 2014). Ultimately, by promoting more in-depth reflection and new perspectives, facilitating richer dialogue, and revealing complex and otherwise hidden experiences, PEI can lead to deeper shared understandings of family caregiving in the dementia context that may not have been accessed without the use of such an approach. [48]

Although a wealth of literature attests to the benefits of PEI, researchers need to carefully evaluate whether this technique would help them gain a deeper exploration of the phenomenon under investigation as well as to assess the feasibility of carrying out PEI. As indicated by MEO (2010), the process is time intensive, takes effort, and is more demanding than traditional, verbal-only interviews. In moving forward, researchers will have to manage the different types of ethical, methodological, and practical challenges that can emerge before, during and after photo-elicitation interviews (MEO, 2010), some of which have been discussed in this article. Tips can be provided to participants as part of the pre-briefing such as blurring techniques when they want to share an image with identifiable people and/or places that are important to their experience. [49]

Past research endeavors have also demonstrated that including photographs in the research process is suitable for use with many different populations, such as children (TORRE & MURPHY, 2015), and different lived experiences, such as living with depression (SANDHU, IVES, BIRCHWOOD & UPTHEGROVE, 2013). The current study shows how photographs can highlight and illustrate the complexity and multidimensionality involved in family caregiving in the dementia context, thereby adding to the growing literature of how PEI can be used to better understand the experiences of this particular population. Photographs should thus be included in the outputs of research as they can offer a powerful way of communicating the experiences of participants to various professional and lay groups and have the potential to reach a far greater and more diverse audience. [50]

Based on the study findings, I position PEI using participant-produced photographs as a useful approach for generating rich, holistic and multifaceted data by facilitating deeper shared understandings between the participants and the researcher. This approach enabled family caregivers to have control over image creation and meaning-making which yielded a more comprehensive discussion of their experiences and offered greater insight than could have been accomplished through verbal-only interviews. Having photographs generated by the family caregivers themselves led to a more in-depth exploration and discussion of the experiences that are most salient to them. As a result, the photographs and subsequent dialogues offered a unique and meaningful glimpse into the experiences of family caregivers that was not previously explored. Incorporating photographs in the research process when exploring phenomena can encourage researchers to obtain richer narratives as well as to better engage those they study and those they wish to reach with their work. Finally, building upon other researchers' work, I showed that PEI provides the means through which family members can contribute to meaning-making and knowledge building relevant to the relational aspects of caregiving in the dementia context. [51]

I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my thesis co-supervisors, Dr. Kristine NEWMAN and Dr. Lori SCHINDEL MARTIN, and committee member, Dr. Jennifer LAPUM for their support and guidance that helped me to flourish and grow as a researcher. It was their encouragement as well as creative and expert insights that made my Master's thesis, and this article, possible.

I am immensely grateful to the five family caregivers who participated in my study with such passion, courage, and enthusiasm. Thank you for sharing your time and experiences. A special thank you to all the individuals and organizations who helped with recruitment for this project.

I would like to acknowledge and thank the Graduate Studies at Toronto Metropolitan University, Alzheimer's Society Research Program, Canadian Nurses Foundation, Nursing Leadership Network of Ontario, and Canadian Gerontological Nursing Association for their financial support of my graduate studies.

Bates, Elizabeth A.; McCann, Joseph J.; Kaye, Linda K. & Taylor, Julie C. (2017). "Beyond words": A researcher's guide to using photo elicitation in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 14(4), 459-481.

Bateson, Gregory & Mead, Margaret (1942). Balinese character: A photographic analysis. New York, NY: New York Academy of Sciences.

Boydell, Katherine; Gladstone, Brenda M.; Volpe, Tiziana; Allemang, Brooke & Stasiulis, Elaine (2012). The production and dissemination of knowledge: A scoping review of arts-based health research. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 13(1), Art. 32, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-13.1.1711 [Accessed: January 25, 2022].

Braun, Virginia & Clarke, Victoria (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77-101.

Braun, Virginia; Clarke, Victoria & Weate, Paul (2016). Using thematic analysis in sport and exercise research. In Brett Smith & Andrew C. Sparkes (Eds.), Routledge handbook of qualitative research in sport and exercise (pp.191-205). London: Routledge.

Burles, Meridith & Thomas, Roanne (2014). "I just don't think there's any other image that tells the story like [this] picture does": Researcher and participant reflections on the use of participant-employed photography in social research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 13(1), 185-205, https://doi.org/10.1177%2F160940691401300107 [Accessed: January 25, 2022].

Clark, Andrew & Morriss, Lisa (2017). The use of visual methodologies in social work research over the last decade: A narrative review and some questions for the future. Qualitative Social Work, 16(1), 29-43.

Clark-Ibáñez, Marisol (2004). Framing the social world with photo-elicitation interviews. American Behavioral Scientist, 47(12), 1507-1527.

Collier, John Jr. (1957). Photography in anthropology: A report on two experiments. American Anthropologist, 59, 843-859.

Colorafi, Karen Jiggins & Evans, Bronwynne (2016). Qualitative descriptive methods in health science research. Health Environments Research & Design Journal, 9(4), 16-25.

Copes, Heith; Tchoula, Whitney; Brookman, Fiona & Ragland, Jared (2018). Photo-elicitation interviews with vulnerable populations: Practical and ethical considerations. Deviant Behavior, 39(4), 475-494.

Dupuis, Sherry; McAiney, Carrie A.; Fortune, Daria; Ploeg, Jenny & de Witt, Lorna (2016). Theoretical foundations guiding culture change: The work of the Partnerships in Dementia Care Alliance. Dementia, 15(1), 85-105, https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1471301213518935 [Accessed: January 25, 2022].

Edmondson, Amanda J.; Brennan, Cathy & House, Allan O. (2018). Using photo-elicitation to understand reasons for repeated self-harm: A qualitative study. BMC Psychiatry, 18(1), 98, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-018-1681-3 [Accessed: January 25, 2022].

Evans, David; Robertson, Jacinta & Candy, Allen (2016). Use of photovoice with people with younger onset dementia. Dementia, 15(4), 798-813.

Genoe, Rebecca & Dupuis, Sherry L. (2013). Picturing leisure: Using photovoice to understand the experience of leisure and dementia. The Qualitative Report, 18(11), 1-21, https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2013.1545 [Accessed: January 25, 2022].

Glaw, Xanthe; Inder, Kerry; Kable, Ashley & Hazelton, Michael (2017). Visual methodologies in qualitative research: Autophotography and photo elicitation applied to mental health research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 16(1), 1-8. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1609406917748215 [Accessed: January 25, 2022].

Hagedorn, Mary (1994). Hermeneutic photography: An innovative aesthetic technique for generating data in nursing research. Advances in Nursing Science, 17(1), 44-50.

Harper, Douglas (2002). Talking about the pictures: A case for photo elicitation. Visual Studies, 17(1), 13-26.

Hennelly, Niamh; Cooney, Adeline; Houghton, Catherine & O'Shea, Eamon (2021). Personhood and dementia care: A qualitative evidence synthesis of the perspectives of people with dementia. The Gerontologist, 61(3), e85-e100, https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnz159 [Accessed: January 25, 2022].

Jenkings, Neil K.; Woodward, Rachel & Winter, Trish (2008). The emergent production of analysis in photo elicitation: Pictures of military identity. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 9(3), Art. 30, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-9.3.1169 [Accessed: October 21, 2022]

Jonas-Simpson, Christine; Mitchell, Gail; Dupuis, Sherry; Donovan, Lesley & Kontos, Pia (2022). Free to be: Experiences of arts-based relational caring in a community living and thriving with dementia. Dementia, 21(1), 61-76, https://doi.org/10.1177%2F14713012211027016 [Accessed: January 25, 2022].

Lapum, Jennifer L.; Liu, Linda; Church, Kathryn; Hume, Sarah; Harding, Bailey; Wang, Siyuan; Nguyen, Megan; Cohen, Gideon & Yau, Terrence M. (2016). Knowledge translation capacity of arts-informed dissemination: A narrative study. Art Research International: A Transdisciplinary Journal, 1(1), 259-282, https://doi.org/10.18432/R2BC7H [Accessed: January 25, 2022].

Lindauer, Allison & Harvath, Theresa A. (2014). Pre‐death grief in the context of dementia caregiving: A concept analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 70(10), 2196-2207.

Macdonald, Diane; Dew, Angela & Boydell, Katherine M. (2020). Structuring photovoice for community impact: A protocol for research with women with physical disability. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 21(2), Art. 16, http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-21.2.3420 [Access: October 21, 2022].

Mahoney, Diane Feeney (2010). An evidence-based adoption of technology model for remote monitoring of elders' daily activities. Ageing International, 36(1), 66-81.

Marsh, Wendy; Shawe, Jill; Robinson, Ann & Leamon, Jen (2016). Moving pictures: The inclusion of photo-elicitation into a narrative study of mothers' and midwives' experiences of babies removed at birth. Evidence Based Midwifery, 14(2), 44-48.

Meo, Analía Inés (2010). Picturing students' habitus: The advantages and limitations of photo-elicitation interviewing in a qualitative study in the city of Buenos Aires. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 9(2), 149-171, https://doi.org/10.1177%2F160940691000900203 [Accessed: January 25, 2022].

Padgett, Deborah K.; Smith, Bikki Tran; Derejko, Katie-Sue; Henwood, Benjamin F. & Tiderington, Emmy (2013). A picture is worth ...? Photo elicitation interviewing with formerly homeless adults. Qualitative Health Research, 23(11), 1435-1444.

Rath, Tom (2015). You can't be anything you want to be ... Webpage, http://www.tomrath.org/can-anything-want-myth/ [Accessed: January 25, 2022].

Rayment, Georgie; Swainston, Katherine & Wilson, Gemma (2019). Using photo‐elicitation to explore the lived experience of informal caregivers of individuals living with dementia. British Journal of Health Psychology, 24(1), 102-122.

Richard, Veronica M. & Lahman, Maria K.E. (2015). Photo-elicitation: Reflexivity on method, analysis, and graphic portraits. International Journal of Research & Method in Education, 38(1), 3-22.

Ryan, Tony; Nolan, Mike; Reid, David & Enderby, Pam (2008). Using the senses framework to achieve relationship-centred dementia care services: a case example. Dementia, 7(1), 71-93.

Sandelowski, Margarete (1986). The problem of rigor in qualitative research. Advances in Nursing Science, 8(3), 27-37.

Sandelowski, Margarete (2000). Whatever happened to qualitative description?. Research in Nursing & Health, 23(4), 334-340.

Sandelowski, Margarete (2010). What's in a name? Qualitative description revisited. Research in Nursing & Health, 33(1), 77-84.

Sandhu, Amrita; Ives, Jonathan; Birchwood, Max & Upthegrove, Rachel (2013). The subjective experience and phenomenology of depression following first episode psychosis: A qualitative study using photo-elicitation. Journal of Affective Disorders, 149(1-3), 166-174.

Schwind, Jasna K. (2009). Metaphor-reflection in my healthcare experience. Aporia, 1(1), 15-21, https://doi.org/10.18192/aporia.v1i1.3059 [Accessed: January 25, 2022].

Shell, Lynn (2014). Photo-elicitation with autodriving in research with individuals with mild to moderate Alzheimer's disease: Advantages and challenges. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 13(1), 170-184, https://doi.org/10.1177%2F160940691401300106 [Accessed: January 25, 2022].

Suri, Harsh (2011). Purposeful sampling in qualitative research synthesis. Qualitative Research Journal, 11(2), 63-75.

Tao, Hong; McRoy, Susan; Kovach, Christine R. & Wang, Lin (2016). Performance and usability of tablet computers by family caregivers in the United States and China. Research in Gerontological Nursing, 9(4), 183-192.

Torre, Daniela & Murphy, Joseph (2015). A different lens: Using photo-elicitation interviews in education research. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 3(111), 1-26, https://doi.org/10.14507/epaa.v23.2051 [Accessed: January 25, 2022].

Wang, Angel; Newman, Kristine; Schindel Martin, Lori & Lapum, Jennifer (2022). Beyond instrumental support: Mobile application use by family caregivers of persons living with dementia. Dementia, 21(5), 1488-1510, https://doi.org/10.1177/14713012211073440 [Accessed: January 25, 2022]

Warner, Elyse; Johnson, Louise & Andrews, Fiona (2016). Exploring the suburban ideal: Residents' experiences of photo elicitation interviewing (PEI). International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 15(1), 1-9, https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1609406916654716 [Accessed: January 25, 2022].

Whitebird, Robin R.; Kreitzer, Mary Jo; Lewis, Beth A.; Hanson, Leah R.; Crain, Lauren; Enstad, Chris J. & Mehta, Adele (2011). Recruiting and retaining family caregivers to a randomized controlled trial on mindfulness-based stress reduction. Contemporary Clinical Trials, 32(5), 654-661.

Wiersma, Elaine C. (2011). Using photovoice with people with early-stage Alzheimer's disease: A discussion of methodology. Dementia, 10, 203-216.

Angel H. WANG is the corporate professional practice leader at a community hospital in Ontario, Canada. She received her bachelor of science in nursing and master's degree in nursing (thesis stream) from Toronto Metropolitan University, and is currently enrolled in the PhD in Nursing Program at Queen's University. Angel has experience in various roles across the nursing continuum, spanning research, education, administration, and clinical practice. She is deeply passionate about elevating nurses, nursing professional practice, and nursing scholarship to further benefit patient care as well as to enhance outcomes for nurses, organizations, and the healthcare system as a whole.

Contact:

Angel H. Wang

Queen's University

School of Nursing

92 Barrie Street, Kingston, Ontario, K7L 3N6, Canada

E-mail: angel.wang@queensu.ca

Wang, Angel H. (2023). "I took the photograph just to show you a little bit of perspective": Photo-elicitation interviewing with family caregivers in the dementia context [51 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 24(1), Art. 7, http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-24.1.3928.