Volume 9, No. 2, Art. 38 – May 2008

Photography as a Performance

Gunilla Holm

with Fang Huang, Hong Yan Cui, Fatma Ayyad, Shawn Bultsma, Maxine Gilling, Hang Hwa Hong, John Hoye, Robert Kagumba, Julien Kouame, Michael Nokes, Brandy Skjold, Hong Zhong, and Curtis Warren1)

Abstract: This is a study of photography as performance and as an ethnographic research and dissemination method. This project was part of a qualitative research methods course where doctoral students learned to collect and analyze visual data as well as what happens when they engage in a study of their own lives using photography as the main tool. Photographs, taken by the students, with short titles, constituted the only data. Analysis of the photographs without any text proved to be difficult. Written statements in addition to the titles complementing the photographs would have helped in creating the context for understanding the photographs and thereby more clearly communicating the intent of the photographers. The results indicate that an ethnography study based only on photographs would not be possible. Photography needs to be used together with other kinds of data. However, the making and presentation of the photographs allowed the students to construct and perform visually their identities as doctoral students.

Key words: photography, performance, visual research methods, visual language

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Underpinnings

3. Methods

4. Results

4.1 Performing being stressed

4.2 Teaching and learning to use visual methods

5. Discussion and Conclusion

Our cultures are becoming more visual as well as visually sophisticated due to increasingly advanced technology. Visual images surround us and we are used to reading visual images on a daily basis (BALL & SMITH, 1992, p.1). However, in social science research, we have only recently begun to use visual data outside of the traditional ways in anthropology and sociology to some extent. There are difficulties in using photographs as data because few are trained to do so. There are only a few universities offering research methods courses to graduate students in how to collect, analyze and present visual data. GRADY (2001, p.112) also points out that journals are interested in publishing verbal analyses of photographs but not the actual photographs. This is of course something that stifles the development of photography as performance. [1]

Performance in this context is seen as both a form of investigation and a form of representation. The researcher engages in a close collaboration and engagement with the participants in both the research and the representation. In a way this process can be seen as a co-performance (CONQUERGOOD, 1991, as cited in WORTHEN, 1998, p.1099). In addition as LEAVY (2008, p.344) points out, "performances are not read; rather they are experienced. Performances ... are open to multiple meanings, which are derived from the experience of consumption, which may involve a host of emotional and psychological responses, not just 'intellectual' ones." The audience engages in an exchange with the authors/researchers and the meaning is not controlled by the authors/researchers, but negotiated between the two. [2]

My interest in using photography in ethnographic research stems from a study in the early 90s of the schooling of teenage mothers where it became evident that the girls had much more to say than could be said in words. Thereafter I have, in several studies, given cameras to participants in order for them to photograph the way they perceive their reality. However, in earlier studies, unlike in this one, I have always used the photographs in combination with verbal data. My interest in the performative aspect of photography developed thanks to Janice JIPSON and Nicholas PALEY's book Daredevil research (1997), where research was performed in a variety of ways. In this edited book on alternative ways of presenting or re-presenting research poems are combined with art work; text is written on maps; text is not written in page wide lines but interrupted by interjecting conversations; and photographs are combined with poems or other writings. The common themes among these chapters are the performance aspect of disseminating the research as well as what counts as research. As JONES (2006, pp.66-85) describes how he arrived at performative dissemination by searching for arts and humanities based ways of presenting data, I have used photographs as ways of presenting data, not only because the photographs are interesting but also because the translation of the photographs to text could not give an equally full, lively and complex picture. [3]

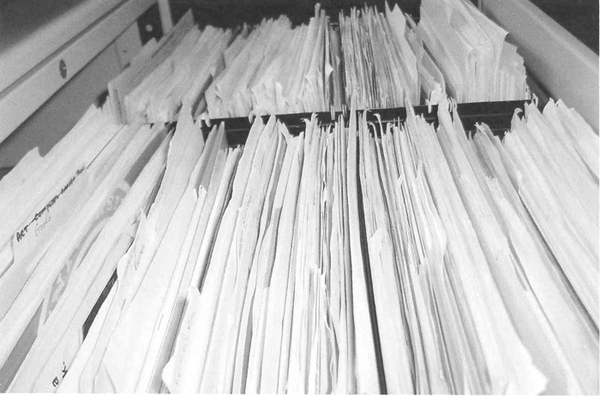

The study used here to discuss photography as performance of qualitative research data was a study of how one learns to collect visual data by using photography as well as what happens when doctoral students study their own lives as doctoral students using photography. The study was part of a qualitative research methods course where we explored ethnographic research methods. This self-study focused on using photography as the only data collection method, instead of using photographs as a supplement to textual data or as a tool for eliciting data in interviews as is commonly the case. This reflexive process made it possible for students to see the "the constructed nature of our lives" as WARREN (2006, p.318) describes performance ethnography. In this construction they ended up performing identity (NOY, 2004, pp.115-138). [4]

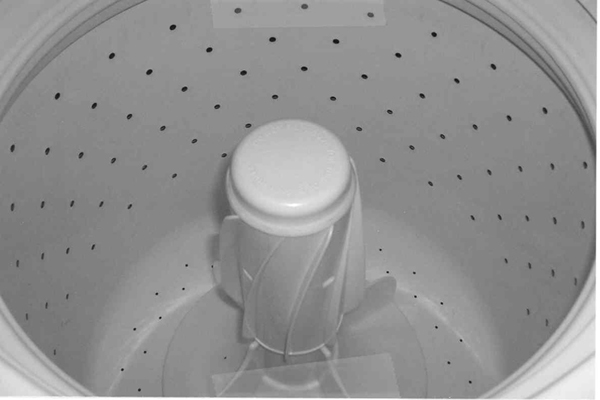

Visual methods as part of data collection in social sciences have increased in popularity in the last ten years, after having functioned for decades mainly as a tool for anthropological documentaries (see COLLIER & COLLIER, 1986) and sociological record keeping (FLICK, 2002, pp.149-150). This increased popularity can be seen in research methods textbooks where visual methods now are included as a data collection method (HATCH, 2002, pp.126-131; GLESNE, 2006, pp.63-65; FLICK, 2002, pp.134-164). Traditionally, visual methods such as photography have been used as providing illustrations to the text without actual analysis of the photographs (BANKS, 2000, p.11) or in anthropology often for documentary purposes (FLICK, 2002). Interestingly, in today's textbooks, photographs are still described as used for documentary purposes as well as for illustrations. Very little is said about photographs as actual data and hardly anything about the analysis of photographs. In most cases visual data is seen as supplementing verbal data, not the other way around. FLICK (2002) reflects on MEAD's views on cameras as tools not only as recorders, but also as making it possible to transport images of artifacts across space. MEAD also saw cameras as providing less biased recordings than observations; in addition, they can then be analyzed by others as well in their original format. [5]

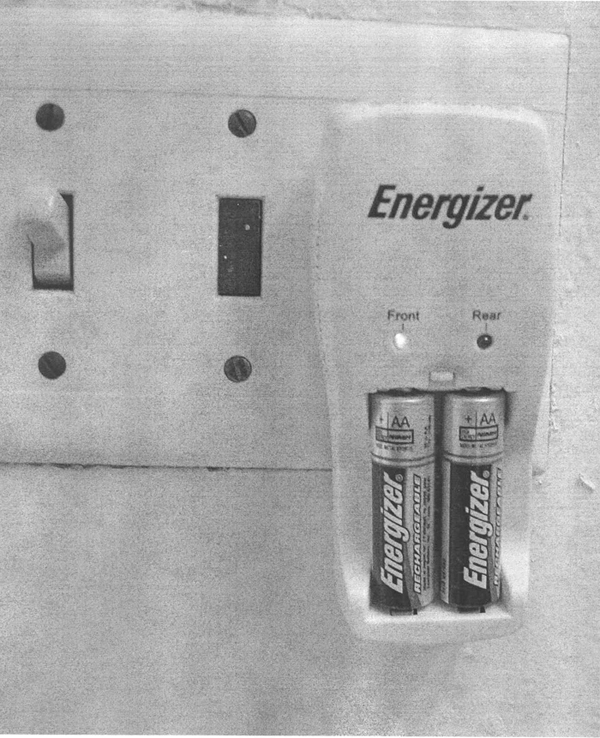

Photographs are also commonly used to elicit information in interviews. Photographs used to elicit information can be taken either by the researcher (HEISLEY & LEVY, 1991, p.257) or by the participants themselves (FLICK, 2002, p.151). The purpose of the use of photographs in interviews is not only to encourage the interviewee to tell about their everyday lives, remember past events or to unlock forgotten information, but also to reveal participants' hidden views and values. Photographs taken by the researcher tend to focus on aspects that the researcher has found interesting, incomprehensible or important in some way. Photographs taken by the participants are considered to reflect the participants' views and open a world that the researcher might not otherwise have access to or consider important (WARREN & KARNER, 2005, p.171). When participants take the photographs they make a choice about what they want to show to others. The photographs become performative. Recently Photovoice (enabling people to record and reflect their own community's strengths and concerns) has added a new dimension to the use of photographs taken by the participants in research. Photovoice has been used as part of action research as a tool for participants to express their perceptions community needs by taking photographs of the things that need improvement in their own neighborhoods (WANG, 2005). It is an effective way for researchers, and eventually policy makers, to learn about participants' views. [6]

So far, the most common types of photographs have been the ones taken by the researchers. However, many are concerned that photographs taken by the researchers influence the scene too much via his or her presence and drawing attention to her or himself by using a camera. Researchers are seen as influencing the situation due to the fact that they typically arrange the scene and participants consciously pose for the camera (BOGDAN & BIKLEN, 2003, pp.105-6; FLICK, 2002, p.152). BOGDAN and BIKLEN (2003, pp.105-6) argue that this subjective influence produces a skewed or flawed image. However, GIBSON (2005, p.3) finds that how a person presents her or himself in front of the camera is important data in itself. Researchers get to know in this way how the participants want to be perceived by others. In HOLM's (1997, pp.61-81) study of teen mothers, it was clear that the participants had a very distinct view of themselves that they wanted to convey to outsiders. They performed a highly complex identity via photographs and texts. Many argue that researchers influence all types of photographs, even if they themselves are absent, since the participants know that they take the photographs for the researchers to use in one way or another. Without being part of a study the participants would not take the photos. However, this kind of influence does not necessarily influence the content or composition of the photograph. [7]

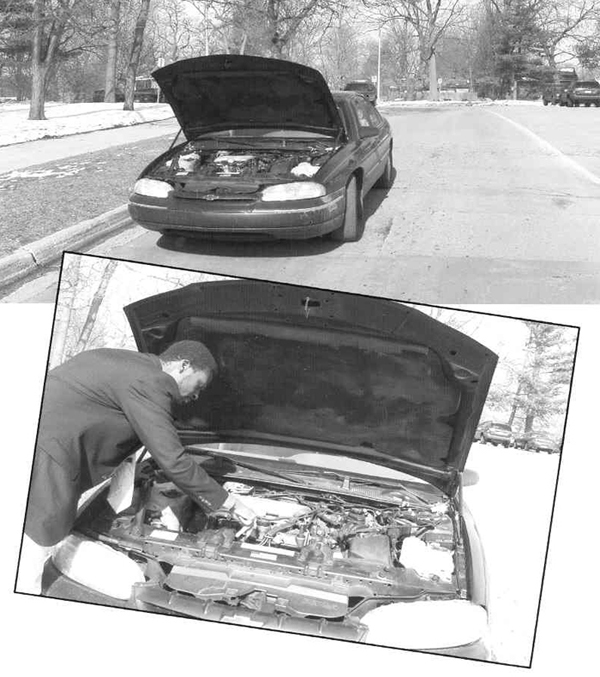

A third kind of photographs, namely pre-existing photographs, such as family photos and newspaper articles, are used in, for example, historical research. They are most commonly used to reconstruct events, relationships and rituals. However, in these cases the circumstances in which the photographs were taken as well as the photographers' intentions are unknown (PROSSER & SCHWARTZ, 1998, p.122). On the other hand, pre-existing photographs can also be used in studies of contemporary issues and situations. Participants might use pre-existing photographs from the past as a contrast to their current situation to indicate a change in their lives. As COREY (2006, p.332) states, "performance ethnography offers the possibility of the understanding of a people through ... an understanding of cultural change as a lived experience." [8]

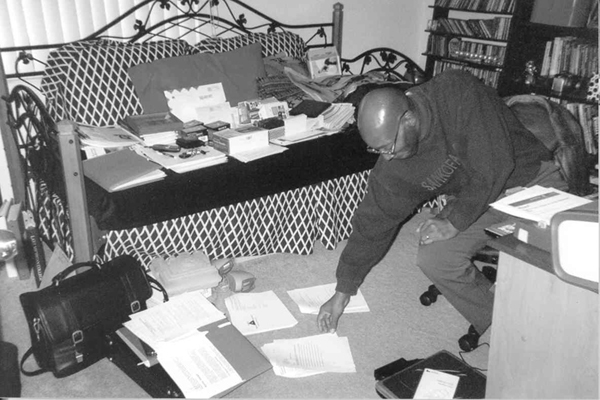

Photographs were, for a long time, seen as showing us "how things really are"; they were seen as documenting reality and the truth (see, for example, BOGDAN & BIKLEN, 2003). This has been the traditional view both in anthropology and sociology However, more recently many have argued that pictures are produced with specific intentions by both the photographer and the photographed (GIBSON, 2005, p.5). According to MCQUIRE (1998, p.47) and PINK (2005, p.13) photographs destabilize the notion of "truth" and single interpretations. Hence reality is a "negotiated version of reality" where both the researcher and the participants bring their experiences to the negotiated reality (PINK, 2005, p.20). On the other hand, even though the photographer and the photographed might have had specific purposes and intentions for a photograph, viewers might have a different interpretation than the intended of the photograph due to their own experiences in life (BERGER, 1972). In other words, how a photograph will be interpreted cannot be entirely controlled or predicted. [9]

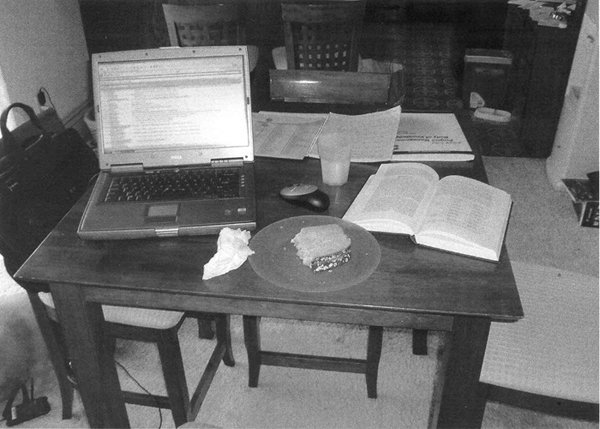

FLICK (2002, pp.149-150) sees one advantage of using photographs as being that they are available for reanalysis and that they sometimes catch things that are too fast for observers to notice. It is somewhat unclear in many cases what is meant by visual analysis and reanalysis. Reanalysis can sometimes only mean that someone else analyzes the images or that they are analyzed a second time. Often photographs are analyzed by translating the photographs into text. However, visual images can be analyzed via, for example, content analysis and semiotic analysis (VAN LEEUWEN & JEWITT, 2004, pp.1-204), or discourse analysis or a more psychoanalytic approach (ROSE, 2005, pp.100-186), but a more ethnographic approach to analysis of visual images is rare. An exception is Sarah PINK (2005, pp.1-175) who brings photographs and the analysis of them to the forefront in her book Doing Visual Ethnography. She criticizes the literature on visual research methods as being too prescriptive with regard to how visual data should be gathered and analyzed. PINK's approach is not to translate the photographs to verbal text,

"but to explore the relationship between visual and other (including verbal) knowledge. This subsequently opens a space for visual images in ethnographic representation ... In practice, this implies an analytical process of making meaningful links between different research experiences and materials such as photography, video, field diaries, more formal ethnographic writing, local written and visual texts, visual and other objects. These different media represent different types of knowledge that may be understood in relation to one another." (p.96) [10]

She further argues that the potential photographs have in their ambiguity and expressiveness has been stifled because of an attempt to be "scientific" and thereby to be objective and to generalize. [11]

In the doctoral level qualitative research methods class in this study, the professor taught about the use of visual research methods by giving the students the task of taking photographs of what it meant to be a doctoral student. Hence, in this study, it was explicitly the students' perceived reality, their own construction of their identity as a doctoral student that was of interest. The students, in many cases, chose to photograph symbols of their own reality rather than their reality in itself. Students had no familiarity with visual research methods in advance of this project. They all owned a camera, but had not had any instruction in photography. The participants in this study were 13 doctoral students in a qualitative research methods practicum. Seven of the students were international students. There were six female and seven male students. Each student brought in four to six photographs to be shared in class. All participants in the class collectively categorized and examined the entire collection of photographs for emerging patterns. The photographs were not analyzed sequentially. Two students then worked further with the professor on analyzing all of the photographs together thematically as well as analyzing separately all the photographs taken by each individual. The individual analyses were brought back to the class for the other students to confirm or disconfirm the results. Hence, each student was asked to confirm or disconfirm our interpretation of his or her photographs. This approach was used in order for students to obtain an understanding of using visual methods as a data collection method and how visual data can be analyzed and the interpretations verified. We were trying out how being immersed in the method, rather than only reading about visual methods, facilitated learning the method. [12]

It could be argued that I as the researcher and course instructor influenced the study because the participants would not have taken the photographs if I had not asked them to do so. Even though I framed the assignment I did not give them any "how-to" and "what-to-photograph" instructions and there is no detectable influence by me on the actual photographs they took. The photographs cover a wide array of topics including photos of family members, offices, travel, food, household chores, picnics, books, etc. Some are composed, while others are snapshots. In as much as possible, we attempted to follow POLLOCK's (2006, pp.325-329) advice about being co-subjects or co-performative, instead of the researcher and the researched. [13]

The informed consent was easy in this case even though it is a difficult issue in taking and publishing photographs of people. In this study, the participants were also co-researchers and adults and could give permission for using photographs of their children. They could also easily ask their spouses for permission. [14]

The photographs took on multiple meanings to some extent, since the meaning the participants gave them when taking the photos probably changed to some extent once we analyzed them in the academic setting of the classroom. The meanings shifted also to some extent, depending on whether the photographs were analyzed all together as performing a collective identity or if each individual's photographs were analyzed separately as performing an individual identity. Unlike in most cases, the photographs were analyzed without being combined with other kinds of data. We were exploring whether ROSE's statement (2005, p.10) that we need "to acknowledge that visual images can be powerful and seductive in their own right" holds up in this study. [15]

The results can be divided into two parts. First, the students' performative photographs of what it means to be a doctoral student. Second, what was learned about teaching and learning to use photography as a performative data collection, analysis and presentation method. [16]

The doctoral students performed being stressed and suffering from a lack of time through symbolic depictions of stress. This theme is expressed in a variety of ways, but it is easy to see how the photographs connect to the main theme. They show that students are stressed and tired through pictures of overflowing filing cabinets, blurry keyboards, sleeping with books on stomachs, expiring parking meters and children too tired to wait for their parents returning after evening classes.

Photograph 1: Filed

Photograph 2: Blurred vision

Photograph 3: I am waiting for my father [17]

The lack of time is also shown by undone household work such as the laundry and the dishes.

Photograph 4: Laundry? It will get done eventually!

Photograph 5:They will get done eventually! [18]

The various approaches taken to manage to do all the work is symbolized through photos depicting Vitamin C, coffee, rechargeable batteries, and alarm clocks.

Photograph 6: Allies

Photograph 7: Recharger [19]

For four of the male students who commute to campus from nearby towns, the car is portrayed as their second home. One of the students took two photographs of the inside of his car labeling them "the inside of my home."

Photograph 8: Lots of road time

Photograph 9: The inside of my home [20]

Being a poor student means having an old car that does not work consistently when needed, but, in the U.S.A., it is often close to impossible to function without a car.

Photograph 10: Julien said: "It breaks down when you most need it. I wonder if this happens only to graduate students" [21]

Many also took photos of their desks and some of their living rooms covered with their books and articles. Being a doctoral student means working on many things simultaneously.

Photograph 11: My stuff everywhere [22]

Graduate study often means being lonely, with only computers and books as dinner companions because of always having too much to do.

Photograph 12: Dell, my dining companion

Photograph 13: Killing two birds with one stone: Feeding the stomach and the brain [23]

The only visible privilege of graduate study portrayed in these photos is parking rights allowing students to park in a faculty parking lot close to the center of campus instead of in remote student parking lots.

Photograph 14: Parking privilege as a teaching assistant [24]

Overall the motivating factors for doctoral studies were dreams of a bright future and their families, symbolized by happy family photographs and a bright sky. Other than that, there were no happy photos. Interestingly, there were no photographs about relationships with other doctoral students or professors. There was no visible sense of community among students. The only communities portrayed were the family and, for some international students, their host families and some other international students. Students' lives seemed more connected to computers than people.

Photograph 15: Dreaming a future! [25]

In summary, the photographs are the students' performance of their own lives as doctoral students. In other words, the photographs do not show us "the truth," but interpretations of being a doctoral student in the U.S. [26]

4.2 Teaching and learning to use visual methods

Interestingly, we discovered that the photographs could not only be seen as a performance by a group of doctoral students, but also as individual performances. The above mentioned traits were found across the group of doctoral students, but individual students emphasized different things. For example, one international student had only pictures of his family back home and his new friends in the U.S.A. and nothing on graduate study, because it was his family and new friends that kept him going on his own and far from his family in Africa. Several of the international students who struggled with language difficulties expressed that, for them, graduate study took all their time and that they missed their families. They had no time for any kind of social life. For the American students, time with their families was important and the things neglected were the more mundane household tasks. Interestingly, the three American men who all had well paying, high status jobs did not connect their doctoral studies with their jobs in any way. An American woman was the only student who connected her job with her studies; she taught undergraduate classes as part of her job as a teaching assistant. She included photos of her students in a lab and a photo representing the fact that an empty office mailbox meant more time for her own studies. Despite the extreme stress the students conveyed, only one international student expressed direct dissatisfaction with his studies. In his case, his language skills were weak and the graduate work became too much, leading him to have no time with his family that was with him in the U.S.A. [27]

Methodologically, this approach exposed students to a new way of thinking about data collection, analysis and presentation. Many saw opportunities for the use of visual data in their planned dissertation research. It also became clear, however, that participants would have benefited from instruction and practice in taking photographs. Even though all students had taken pictures and had a basic familiarity with photography, they did not have the visual vocabulary for taking photos of, for example, absences or certain moods or approaches to life. For example, several of the international students included photographs of their families or spouses who had stayed behind in their home countries, because they missed them. . However, it still was not clear from just the pictures whether the families were present or not. American students took family photos too to indicate the importance of family. In other words, present and absent families were portrayed in a similar way. Hence, a brief text written by the participants as a complement to the photograph would have made the identity performance more complete and understandable for outside viewers and readers. Participants also need to be taught some basics about how situations can be portrayed in photography. These kinds of experiences underlined for the doctoral students the understanding that substantial training is needed in order to do good quality qualitative research using photographs as data.

Photograph 16: The three things I will not sacrifice!

Photograph 17: My husband and I

Photograph 18: Staying far from family [28]

Photographs 17 and 18 suggest that the families are absent, unlike in photograph 16 where the family is present (see HOLM, 2008, for further discussion). This is a good example of what PINK (2005, p.17) argues when she says that visual methods cannot be used separately from other methods and that they only give us the visual aspects of a culture. These photographs need verbal explanations in order for the reader to fully understand them. Interestingly, photographs 17 and 18 were pre-existing photographs, but the two students who brought in these photographs also brought in recent photographs that they themselves had taken. [29]

Hence it became evident from the pictures that clear instructions are needed for a project where participants are asked to take photographs of their own lives. The intention and instructions were for participants themselves to take photos that portrayed their lives as doctoral students. However, some chose to have others take pictures of them instead of taking the pictures themselves. Some used pictures not specifically taken for this project, but that they considered told their lives as doctoral students. However, there are subtle differences between these three different kinds of pictures and the different kinds of photographs make the analysis more complicated. On the other hand, a how-to manual most likely would have locked the students into certain ways of thinking (PINK, 2005, p.3). In this open way, students explored their own creativity and ingenuity. The results were a surprising variety of photographs. In many ways, the performance of student identities became more comprehensive thanks to the many ways that the photographs were constructed. [30]

Most students commented that once they saw the photographs of others that they got additional ideas on how to express aspects of their lives that they had not known how to express or had not thought about at the time, (like the lack of time to participate in their children's extracurricular activities, for example). Reflections on the photographs evoked new ideas for better expressing one's thoughts. For example, a commuting student suggested taking a new photograph of the same place on the road several days in a row in order to build a collage expressing the repetitive nature of the commute. Several students expressed an interest in taking photographs of their fellow students, which they had not thought of doing at the beginning. In addition, several students also pointed out that they would like to express the positive aspects and the importance of the doctoral studies for themselves as students, but no one had suggestions for how that could be done visually. One of the international students also suggested having a photograph taken of herself looking serious and confused next to a smiling and talking American student in order to express her language difficulties. In other words, time and reflections created new ideas for ways of expressing oneself visually. [31]

As DENZIN (2001, p.26) says "The meanings of lived experiences are inscribed and made visible in these performances." The students lived experiences as doctoral students are made visible in these photographs. In most cases speech and text are seen as performative, but these photographs show that photographs can be performative as well. The students in this study had to think reflexively about themselves, their values and lives as doctoral students. They constructed their identity through the photographs and then performed their identities by showing the photographs to others. The performance adds depth and variation to the qualitative research process and, in this particular case, to our understanding of what it means to be a doctoral student. Interestingly, performing identities in this way creates similarities to the way teenagers and adults create their Internet identities. Since the students asked themselves the question, what life as a doctoral student means and answered it without being asked further questions by the researcher, they could decide on what to include and exclude. As a young girl said in THOMAS' (2007, p.69) study Youth online about the identity she had created online: "It's a lot like me, but minus the things I don't like about me." In other words, the students could choose what kind of identity they wanted to construct via the photographs. [32]

Students learned to think in non-verbal terms and how to express their realities and feelings from the collective viewing and analysis of the photographs of others. They learned how photographs are perceived and interpreted differently by different people as the photographs were analyzed and discussed in class (PINK, 2005, p.69; SCHWARTZ, 1992, p.13). Certain aspects emerged as particularly difficult to portray as visual images. Absence or missed opportunities related to being a doctoral student were particularly difficult to photograph. However, this project also showed that students need training in learning a visual language because of their unfamiliarity with thinking in visual terms. Students, like others in our culture, consume visual images daily, but rarely produce them other than in the form of snapshots. In addition, we concluded that in the interpretation of photographs it is beneficial if they are accompanied by verbal descriptions clarifying the context of the photographs as well as other verbal data. In conclusion, we found that expressing what it means to be a doctoral student through photographs provided a richer set of data or in ROSE's (2005, p.10) terms, the photographs were powerful and seductive. Using only verbal data would not have provided the same thoughts about what it means to be a doctoral student as the photographs did. Thinking in visual terms was a rewarding experience, opening students' eyes to a different way of collecting data and performing the results. It further served to draw attention to the fact that both visual and verbal data are useful, but that the relationship between the two is not hierarchical. In addition, it is the relationship that often brings out the most interesting aspects and contradictions. In HOLM's (1997, pp.61-81) ethnographic study of pregnant and parenting teenage girls, the girls presented themselves verbally as unhappy and troubled, but in the photographs they took of each other they presented themselves as happy and playful. The contradiction between the two kinds of data gave a much more varied and fuller understanding of the girls than only one set of data would have given. [33]

In summary, Pink argues that we should reject "the idea that the written word is essentially a superior medium of ethnographic representation. While images should not necessarily replace words as the dominant mode of research or representation, they should be regarded as an equally meaningful element of ethnographic work. Thus visual images should be incorporated when it is appropriate, opportune or enlightening to do so. Images may not necessarily be the main research method or topic" but in relation to other aspects of the research they can contribute to the research (PINK, 2005, pp.4-5). "This approach recognizes the interwovenness of objects, texts, images and technologies in people's everyday lives and identities." (PINK, 2005, p.6) Hence, using photography, as a performative ethnographic research method, is best used together with other methods, but where photography is used for drawing attention to the visual aspects of a culture. [34]

1) This photography project was a truly collaborative project with regard to data collection and analysis. However, the students were not part of writing this article. Therefore they are listed as having worked on this project with me instead of as co-authors. <back>

Ball, Michael & Smith, Gregory (1992). Analyzing visual data. London: Sage.

Banks, Marcus (2000). Visual anthropology: Image, object and interpretation. In Jon Posser (Ed.), Image-based research. A sourcebook for qualitative researchers (pp.9-23). London: Routledge Falmer.

Berger, John (1972). Ways of seeing. London: British Broadcasting Association and Penguin.

Bogdan, Robert & Biklen, Sari (2003). Qualitative research for education. An introduction to theory and methods. New York: Allyn and Bacon.

Collier, John, Jr. & Collier, Malcom (1986). Visual anthropology. Photography as a research method. Albaquergue: University of New Mexico Press.

Corey, Frederick C. (2006). On possibility. Text and Performance Quarterly, 26(4), 330-332.

Denzin, Norman (2001). The reflexive interview and a performative social science. Qualitative Research, 1(1), 23-46, http://grj.sagepub.com/cgi/content/abstract/1/1/23 [Retrieved: October 19, 2007].

Flick, Uwe (2002). An introduction to qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Gibson, Barbara (2005). Co-producing video diaries: The presence of the "absent" researcher. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 4(3), Art. 3, http://www.ualberta.ca/~ijqm/backissues/4_4/pdf/gibson.pdf [Retrieved: March 8, 2006].

Glesne, Corrine (2006). Becoming qualitative researchers. An introduction. London: Pearson.

Grady, John (2001). Becoming a visual sociologist. Sociological Imagination, 38(1/2), 83-119.

Hatch, J. Amos (2002). Doing qualitative research in education settings. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Heisley, Deborah D. & Levy, Sidney (1991). Autodriving: A photoelicitation technique. Journal of Consumer Research, 18, 257-272

Holm, Gunilla (1997). Teenage motherhood: Public posing and private thoughts. In Janice Jipson & Nicholas Paley (Eds.), Daredevil research. Re-creating analytic practice (pp.61-81). New York: Peter Lang.

Holm, Gunilla (2008). Visual research methods: Where are we and where are we going? In Sharlene Hesse-Biber & Patricia Leavy (Eds.), Handbook of emergent methods (pp.325-341). New York: Guilford.

Jipson, Janice & Paley, Nicholas (Eds.) (1997). Daredevil research. Re-creating analytic practice. New York: Peter Lang.

Jones, Kip (2006). A biographic researcher in pursuit of an aesthetic: The use of arts-based (re)presentations in "performative" dissemination of life stories. Qualitative Sociology Review, 2(1), 66-85, http://www.qualitativesociologyreview.org/ENG/archive_eng.php [Retrieved: October, 2007].

Leavy, Patricia (2008). Performance-based emergent methods. In Sharlene Nagy Hesse-Biber & Patricia Leavy (Eds.), Handbook of emergent methods (pp.343-357). New York: Guilford.

McQuire, Scott (1998). Vision of modernity: Representation, memory, time and space in the age of the camera. London: Sage.

Noy, Chaim (2004). Performing identity: Touristic narratives of self-change. Text and Performance Quarterly, 24(2), 115-138.

Pink, Sarah (2005). Doing visual ethnography. London: Sage.

Pollock, Della (2006). Marking new directions in performance ethnography. Text and Performance Quarterly, 26(4), 325-329.

Prosser, Jon & Schwartz, Dona (1998). Photographs within the sociological research process. In Jon Prosser (Ed.), Image based research: A sourcebook for qualitative researchers (pp.115-129). London: Falmer Press.

Rose, Gillian (2005). Visual methodologies. An introduction to the interpretation of visual materials. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Schwartz, Dona (1992). Waucoma twilight. Generalizations on the farm. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press.

Thomas, Angela (2007). Youth online. Identity and literacy in the digital age. New York: Peter Lang.

Van Leeuwen, Theo & Jewitt, Carey (2004). Handbook of visual analysis. London: Sage.

Wang, Caroline (2005). Photovoice. Social change through photography, http://www.photovoice.com/method/index.html [Retrieved: July 19, 2006].

Warren, Carol & Karner, Tracy (2005). Discovering qualitative methods. Field research, interviews, and analysis. Los Angeles: Roxbury Publishing Company.

Warren, John (2006). Introduction: Performance ethnography: A TPQ symposium. Text and Performance Quarterly, 26(4), 317-319.

Worthen, W. B. (1998). Drama, performativity, and performance. PMLA, 113(5), 1093-1107.

Dr. Gunilla HOLM is a Professor of Education, Department of Education, University of Helsinki. Professor Holm's research interests are focused on qualitative research methods as well as issues in education related to race, ethnicity, class and gender. She has also published widely on adolescent cultures and on schooling in popular culture. Her publications include the following co-edited books: Contemporary Youth Research: Local Expressions and Global Connections; Imagining Higher Education: The Academy in Popular Culture; and Schooling in the Light of Popular Culture. Among her recent articles and chapters are: Visual Research Methods: Where Are We and Where Are We Going?; Urban Girls' Need to Be Heard; Teaching in the Dark: The Geopolitical Knowledge and Global Awareness of the Next Generation of American Teachers; and The Sky is Always Falling: [Un]Changing Views on Youth in the U.S.

Shawn BULTSMA, assistant professor, Grand Valley State University; Fatma AYYAD, Hong Yan CUI, Maxine GILLING, Hang Hwa HONG, John HOYE, Fang HUANG, Robert KAGUMBA, Julien KOUAME, Michael NOKES, Brandy SKJOLD, Hong ZHONG, and Curtis WARREN are doctoral students at Western Michigan University.

Contact:

Dr. Gunilla Holm

Department of Education

P.O. Box 9, 00014 University of Helsinki

Finland

E-mail: gunilla.holm(at)helsinki.fi

Holm, Gunilla (2008). Photography as a Performance [34 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 9(2), Art. 38, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs0802380.