Volume 24, No. 1, Art. 12 – January 2023

Challenges of Multimethod and Mixed Methods Designs in Museum Research

Jennifer Eickelmann & Nicole Burzan

Abstract: In this article, we draw on two research projects on museums to present how we combined qualitative and quantitative methods (e.g. semi-structured interviews, non-standardised observations, focused ethnographies, ethnographic observations and conversations; standardised surveys and observations), which designs we used, and which opportunities and challenges we encountered. Given today's pluralised museum landscape, the research involved questions of whether and to what extent museums are oriented to offering experiences and which role museum guards play beyond their security function. We show how combining different methods can be particularly fruitful for examining fields characterised by a range of tensions from different perspectives. On the one hand, this allows us to grasp the (conflictual) interplay of different dimensions (actors, exhibition aesthetics, concepts, discourses), and on the other hand, we can broadly situate our objects of research and interpretations. The first challenge we discuss is the temporality of the empirical procedure, including questions of how linear and iterative approaches as well as procedures running in parallel and sequentially can be integrated. Secondly, we ask to what extent findings from different approaches and museums can be compared with each other during the analysis—broadly or deeply, with regard to the number of museums or dimensions.

Key words: museum; mixed methods; multimethods; temporality; comparability; inequality; power; method addition; method integration; situating

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. Two Empirical Research Projects in Museums

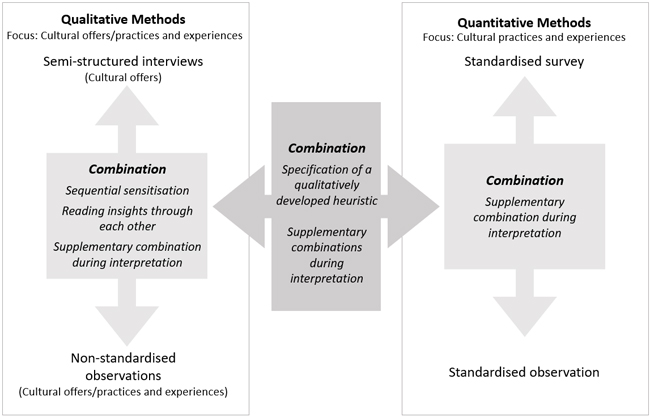

2.1 Dramaturgy of the event-oriented museum

2.2 On the role of museum guards

3. Plurality of Methods: Opportunities and Challenges Using the Example of Museum Research

3.1 Making complex tensions visible through plurality of methods

3.2 Optimising reflection on the researcher's role through plurality of methods

3.3 Conflicting temporalities as a challenge

3.4 Comparability as an impediment to method integration

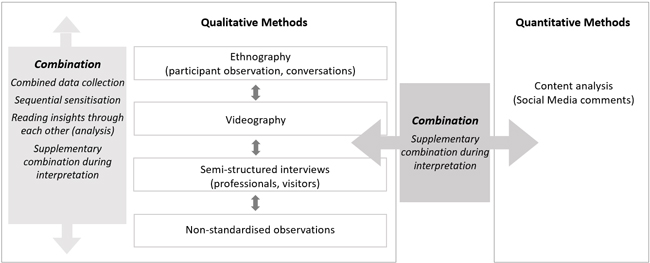

4. Conclusion

In this article, we discuss research methods we used in museums, which we understand as cultural institutions and organisations as well as media of knowledge communication (BENNETT, 1995; MACDONALD, 2011; NIELSEN, 2017). Here, researchers find themselves in a field that is increasingly differentiated and varies greatly in terms of, for example, genres, themes, modes of design and visitor profiles. An art exhibition, staged in terms of a white cube aesthetic, and a scenographic interactive exhibition on knights or dinosaurs represent quite different ways of conveying knowledge and culture. And museums are also complex as organisations insofar as different demands have to be reconciled: economic, political, legal concerns as well as subject-specific, aesthetic, pedagogical and, with growing digitisation, also media-technological aspects (HENNING, 2006). Furthermore, in the context of contemporary social debates, exhibitions should be attractive to highly heterogeneous visitors—just think of discourses on the diversity of artists or discussions on the restitution of objects appropriated in colonial contexts (SARR & SAVOY, 2018). [1]

Closely linked to our focus on the sociology of social inequality, we are interested in the potential reproduction of social and societal inequality that may occur in museums (BOURDIEU & DARBEL, 1991 [1966/1969]). We consider mixed and multimethod approaches to be rewarding, especially from the perspective of our museum research, which is characterised by a focus on inequality and power relations, how they change and how they are embedded in complex figurations of conditions. With the help of specific combinations of different perspectives and points of view, central tensions (and also conflicts) can be illuminated, and at the same time it becomes possible to identify reciprocal conditionalities. Inequality and power relations in museums, as well as the tensions that ensue, comprise different dimensions, and we have identified the following as relevant: The level of actors in the field (including museum managers, museum guards and the public), the level of exhibition aesthetics (including spatial and object-related stagings and offers of activities) and the level of museum concepts and discourses (including specific organisational concepts for museums as well as debates on the changing social functions of museums). As we will see below, mixed and multimethod approaches can be particularly productive here, especially because researchers can use them to illuminate a certain perspective, a specific process or a concrete event from different angles in order to gain insights into relationships, associations and configurations of conditions (UPRICHARD & DAWNEY, 2019). Thus, an exhibition's aesthetic and the opportunities for participation or exclusion associated with it are experienced quite differently from the researcher's perspective before the underlying concept has been discussed with those responsible, and it is viewed differently again, for example, after the role of the museum guards has been illuminated. Our multi-perspective approach is based on the conceptual assumption that the actors in the field, particular exhibition aesthetics and underlying museum concepts and discourses are constitutively related to each other without necessarily corresponding causally or linearly. For example, a curator's specific position on the issue of art and inclusion can be elaborated into an opinion (first dimension), but this can by no means be unidirectionally transposed into an exhibition aesthetic or even the practices of museum visitors (second dimension). This is also due to the fact that the conception of exhibitions (i.e. our third dimension) is tied to further organisational aspects (e.g. security concepts), which can stand in a conflictual relationship to the curator's artistic or educational position. Even if the dimensions we focus on are constitutively related to each other, numerous and differing tensions and frictions arise in the context of participation and inclusion imperatives. We consider a multimethod approach appropriate for exploring these areas. [2]

In this article, we first present the empirical approach we employed in two research projects on museums including which methods we used and how we combined them (Section 2). We then discuss the opportunities and challenges associated with these combinations and how we dealt with them (Section 3). Key terms on the side of opportunities are, firstly, being able to grasp the complexity of the tensions in a museum by not only viewing tensions and frictions from one perspective, but looking instead at specific constellations involving different actors and organisational processes. Secondly, it is possible to enhance reflections during the research process by relating a specific insight to additional perspectives. We use this procedure to situate and further develop temporal findings. On the side of challenges, the temporality of the empirical procedure and the comparability of data and findings should be mentioned. With regard to temporal aspects, in addition to access restrictions specific to the field, linear and iterative approaches as well as procedures running in parallel and sequentially must be brought together coherently. With regard to comparability, our intention is, among other things, to ascertain the extent to which findings derived from different methods in one or several museums can be compared during the analysis. We consider the differentiation and pluralisation of museum genres and concepts to be one of the field-specific challenges, making it necessary to decide reflectively between breadth or depth of comparison (ALEXANDER, 2020). Finally, we draw some conclusions on the merits and limitations of mixed and multimethod research in museums and conclude with an outlook (Section 4). [3]

2. Two Empirical Research Projects in Museums

2.1 Dramaturgy of the event-oriented museum

In the first project, funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) [German Research Foundation] from 2014 to 2017 and in cooperation with Diana LENGERSDORF (University of Bielefeld, Germany), we investigated the question to what extent museums of different genres can today be described as event-oriented or experience-driven. Our focus included the question to what extent exhibitions (among other things through their aesthetics) are designed as entertainment and multi-sensory emotional experiences, and what consequences this has for changed opportunities to participate, but also for visitor's (distinctive) behaviour or practices.1) We identified the interplay between, on the one hand, the perspectives of museum managers and specific exhibition stagings, and those of the public on the other. [4]

In three museums (one art museum, one history museum and one museum of the history of technology) in Germany we employed different methods in each:

Non-standardised observations of the exhibition situation and the practices of cultural reception associated with it: During multiple visits, we gained an overview of the experiential character of the exhibitions. How are objects staged, what can visitors do, but also which boundaries are set? What do the visitors actually do? The field protocol was not divided into separate sections for different aspects of our question (e.g. exhibition design, visitor behaviour); instead, we recorded their intersection (e.g. how a visitor reacts to a certain staging).

Semi-structured interviews with six heads of museums and departments as well as curators: In the interviews, we employed different narrative questions, and from them we learned something about the idea of the museum and its organisation, about the exhibitions, about the positioning of the museum in the museum landscape and about the interviewees' experiences from their professional perspective.

Standardised observations of visitors: We observed visitor behaviour on different days of the week, at different times and in different weather conditions at five fixed observation points per museum. A total of 1,946 people were observed (between 107 and 171 people per observation point). By means of this rather rare instrument for quantitative research (technically, systematic field observation, which may take a quantitative or qualitative form; VAN MAANEN, 1982) and by positioning ourselves at stations with different characteristics (e.g. with or without a hands-on object, at a more or less central location in the exhibition), we were able to investigate, for example, what visitors look at and for how long, whether they use hands-on stations and how they interact with their fellow visitors. In this way, we were able to monitor which effects are achieved with intentional measures designed to steer visitors' attention.

Standardised surveys of the visitors at the end of their visit: 349 respondents took part in the three museums on different days of the week and at different times. They were asked, among other things, about their social situation, their experiences with museum visits, their motive for visiting, their visiting behaviour (e.g. whether they read texts providing information) and for an evaluation of their visit. [5]

We also visited other museums once or several times, sometimes as part of events, took photographs (and thus also archived aspects of exhibitions) and wrote protocols. These visits were not only exploratory, but we also used them to expand our comparative horizon. To this end, we visited as varied museums as possible (including Science Centres which are borderline cases as there is no agreement about whether they are museums at all due to not having a museum collection in a strict sense). In the course of both research projects, we visited 63 museums in twelve countries (Europe, Asia and the USA) and completed a total of 139 protocols. In seven museums in German-speaking countries (in addition to the three that were intensively studied) we conducted a semi-structured interview with staff in leadership positions. We also explored and included the museums' public relations material as found on their homepages or exhibition flyers. The analytical strategy for the data in the qualitative strand—in both projects—was based on grounded theory (CORBIN & STRAUSS, 2015), the quantitative data was analysed with standard statistical, predominantly descriptive methods. [6]

Sampling: In studying three museums more intensively, we were not aiming for statistical representativeness, nor did we follow theoretical sampling (ibid.) in the strict sense. Instead, these are exploratory individual case studies (YIN, 2014). By, firstly, comparing different museum genres (art museum, cultural history museum and technical history museum), where we suspected different forms and extents of orientation towards providing experiences, and, secondly, through supplementary observations in numerous other museums, we were able to cover a broad spectrum of museums and to identify typical figurations of conditions. Within the museums, we were also able to achieve a satisfactory spread of cases for the standardised data collection by varying the days of the week and times of day. Given the number of cases (observations per observation point, respondents per museum), however, we were only able to investigate differentiated subgroups to a limited extent. [7]

We applied sequential and parallel designs (Fig. 1). Within the qualitative strand combinations were realised through 1. sequential sensitisation. Observations resulted in specific follow-up questions for the semi-structured interviews, e.g. on certain forms of staging, and in part vice versa.

Figure 1: Mixed methods design in the project "Experience-orientation in the Museum" [8]

During 2. data analysis we also interpreted data in the light of preliminary interpretations of other data. Together with the knowledge of the interviewees' understanding of experience, this allowed us to see certain forms of staging in a different light. For example, after one observation we were irritated by the way that opportunities for visitor activities were rather unobtrusive, e.g. listening stations were rather hidden. However, the museum director explained that visitors discovering the objects for themselves was precisely part of the concept for offering experiences. Finally, we made 3. complementary combinations of statements, usually when interviewees spoke about their intentions and observers reported specific exhibition situations. Within the quantitative strand, we were also concerned with complementary combinations with reference to the visitors: for example, satisfaction with an exhibition cannot be directly observed, while less reflective aspects of the visit (e.g. how long was someone in room X?) can hardly be inquired about. Finally, we firstly realised the mixed methods combination of qualitative and quantitative data sequentially by generating qualitative hypotheses which we specified quantitatively in a second step. For instance, we qualitatively established a hypothesis about directing attention to certain objects and stagings which could then be operationalised in the standardised observation. It was confirmed that attention was directed as postulated. Secondly, we also made (parallel) supplementary combinations, since the quantitative findings related more directly to the visitors than the qualitative ones. [9]

The substantive findings are not the focus of this paper, however, substantive and methodological concepts are generally closely linked, so we want to present some substantive findings here to aid a more comprehensive overall understanding (BURZAN & EICKELMANN, 2022).

We were able to clearly elaborate and hone the explication of the trend towards offering experiences, which had previously only been viewed as a heuristic anchor point: Among other things, it became visible through the staged contextualisation and aestheticisation of objects and various activity options—in the exhibition and/or in the supporting programme. However, museum managers vehemently rejected a superficial "Disneyization" (BRYMAN, 2004).

This trend is accompanied by various types of tension and conflicts of interest. On the one hand, museum managers oriented themselves towards concepts of visitor participation and emphasised their visitors' sovereignty, while on the other hand they clearly directed their visitors in terms of space and time. Furthermore, museum managers often found themselves in a permanent dilemma between the core brand of their institution and economic, pedagogical and funding policy requirements.

In terms of opportunities for social distinction, experience-oriented exhibitions are ambivalent. Some opportunities have disappeared (e.g. being quiet as behaviour displaying familiarity with museums), but others have been added (e.g. confident handling of electronic hands-on stations). According to our findings, cultural practices that are most distinctively connected to particular classes (relative to others) are harder to grasp empirically than one might assume from the pertinent literature (e.g. BOURDIEU, 2005 [1979]; BOURDIEU & DARBEL, 1991 [1966/1969]). [10]

2.2 On the role of museum guards

In the second project, which was funded by the Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (BMBF) [Federal Ministry of Education and Research], 01JK1603, from 2016 to 2019, we studied the guards in museums as an interface between museums and their visitors. Our interest in this topic partially stemmed from our previous museum project. During our on-site observations we regularly talked to the guards and discovered that they not only had a lot to tell us about the visitors, since their job definition is to observe visitors, but we also learned something from them about the background to the exhibition concepts. Secondly, we noticed that despite the interest in interactions in the museum, we had hardly any knowledge about how guards mediate between the exhibition and the visitors, for example when they discipline them or encourage them to look or try things out. So we extended our inquiry to include the questions: To what extent does the transformation of museums also affect the role of the guards? What specific role do they play within the hierarchical museum structures in the context of participatory and inclusive concepts, and how do they combine delivering services with security tasks? Against the backdrop of the increasing orientation towards experiences in the museum field and commensurate activity offers in exhibitions, we asked: Have the supervisory staff evolved from (mostly male) guards to entertainers? From the perspective of inequality theory and power analysis, we also focused on the tensions arising here: For example, friction can result if there is a clash because museum managers claiming the prerogative on interpretation without envisaging any mediating functions in the broader sense for the guards, who in real interaction situations are then confronted with visitors' questions on knowledge issues. Another example for friction is situations in which guards are supposed to simultaneously balance security and service functions (e.g. promoting a good atmosphere, helping with hands-on stations). This perspective is particularly well suited to elaborating the (a)synchronicities in the transformation of museums (and also their stability). Again, we combined different levels: the perspectives and professional practice of the guards, interactions with the visitors, the visitors' perspectives as well as museum managers' conceptual intentions, in order to be able to bring the previously mentioned types of tension into view. [11]

Methods: In this project, we primarily chose an ethnographic approach (for museums: MACDONALD, GERBICH & OSWALD, 2018). With this approach we already embraced methodological pluralism, since both observations and conversations were conducted and recorded. For this purpose, Jennifer EICKELMANN repeatedly accompanied the guards in two museums in their work over several months—a more security-oriented art museum and a museum of technical history where the guards' service-providing functions were also important (21 protocols referring to 62 guards). The main topics of the conversations were biographical information, tasks/self-perception of their work, attitudes/knowledge of the visitors as well as organisational aspects. In one open-air museum we also conducted a focused ethnography KNOBLAUCH, 2005) over several days. In addition, we also collected the following data:

ten observation protocols from a visitor's perspective, completed by a student assistant (Isabelle SARTHER) (dimension: practices),

15 short semi-structured interviews with visitors who had just visited an exhibition with many hands-on stations, some of which were assisted by guards (dimension: visitors' experiences),

eight semi-structured interviews with museum managers and, since the guards were mainly employed by an external service provider, with so-called object managers (dimension: museum concept),

videography in the two museums on a total of five days at seven observation points (approx. 165 hours of recordings) with which we focused on real interaction situations between the guards and the visitors (dimension: guards' practices and perspectives).2) [12]

In addition, we also included the observation protocols of the visits to the other museums mentioned above. The quantitative element in this project consisted of a standardised content analysis. We analysed 104 visitors' comments on three museums of different genres (art, technology and open-air museum) on three digital platforms (Facebook, TripAdvisor, Google Reviews) for the years 2013 to 2018, where visitors (also) mentioned the guards. [13]

By employing these different methods, in this project we aimed to include different actors as well as different analytical dimensions (organisational concepts, attitudes/positioning, practices/interactions) of our research question. [14]

In order to give the depth of our empirical approach priority over breadth, we undertook a focused contrasting comparison between two specific museums, similar to the first project. In doing so, we contrasted a museum of technical history, in which the guards are specifically deployed for knowledge transfer and encouraging participation, with an art museum where the guards' conceptual location is exclusively in the realm of security. We also included other museums in order to be able to systematise the breadth of our findings to a limited degree. Within the museums, we selected cases (and from the videography: observation points) on the basis of diversity and contrast. In the content analysis of the social media comments, the number of cases is comparatively small and therefore we just offer a spotlight on the visitors' perspective, but the 104 comments referencing guards, which were manually selected from a total of 2,282 text comments (as opposed to images), comprise the total population for the period under consideration.

Figure 2: Mixed methods design in the project on museum guards [15]

In this project (Fig. 2), we primarily used parallel combinations, and in some cases data collection already constituted a combination in itself, for example when observations and conversations were conducted at the same time during the ethnography. Furthermore, during the analytic process we considered it important to interpret data in the light of (preliminary) findings from other data so that we could position single perspectives in relation to other perspectives. This was particularly relevant for the comparison of museum managers and guards, who at times seemed to live in opposing professional realities. It also allowed us to reflect on our role as researchers in the field—which, for example, was very different for the ethnographer building a relationship with the people in the field than for the student team member who entered the exhibition as a simple visitor. During this process, we also introduced subordinate sequential elements, for example when as a result of initial interpretations we set a new focus for the next field visit. Finally, supplementary combinations were also used in this project in the overall interpretation of findings that initially stood on their own. This also applies, for example, to the results from the quantitative content analysis, which we used to supplement specific visitor perspectives. [16]

In the literature on mixed and multimethod designs, authors list different numbers and names of designs and their criteria to describe the nature and logic of the combination. For example, weightings and sequences are important, but sometimes also more substantive criteria like transformative design as one of six designs in CRESWELL and PLANO CLARK (2017), compared to five designs in TEDDLIE and TASHAKKORI (2009), or the discussion of seven primary and further secondary dimensions in SCHOONENBOOM and JOHNSON (2017). According to our own systematisation (BURZAN, 2016), the aspects of a sequential or parallel approach, the particular phase of integration and thus also the strength of the respective combinations between methods, data and/or findings were in the foreground in our projects. The question of which methods have a higher weight than others, if any, was of lesser importance. This is because whether a certain method is more or less important at a certain point depends on the particular aspects of our research question, so this cannot be decided for the study as a whole. For example, videography was comparatively less well-suited to gaining an overview of different perspectives on guards and their tasks. However, what we could show better with this method than with any other was how, in their everyday professional practice, guards were able to pragmatically resolve the supposed contradiction between security and service tasks, which was often emphasised in the conversations (for example, there was a pattern of adding service-related information or suggestions after a restrictive conversation). This is connected to an important methodological finding from both research projects in general: When researching complex contexts, it is often crucial to also explore the situative framings. It is actually surprising that although technologically-supported data collection is being increasingly employed in visitor research (e.g. eye tracking or the use of process-produced data in museums' digital offerings: KIRCHBERG & TRÖNDLE, 2015) and openness towards non-standardised methods is also increasing in some cases, the individual is often still considered the sole actor (an exception is e.g. VOM LEHN & HEATH, 2016; see also the consideration of the situation in REITSTÄTTER & FINEDER, 2021). [17]

Here, too, we would like to succinctly summarise some of our findings (BURZAN & EICKELMANN, 2022; EICKELMANN & BURZAN, 2022).

In art museums, the focus is generally on guards' (rather distance-creating) security tasks, in museums of other genres they are also often involved in (closeness-creating) service tasks. In addition to providing basic information (e.g. for orientation) and creating a good atmosphere, this also involves sharing knowledge in a broader sense (e.g. also experiential or anecdotal knowledge) or providing support at hands-on stations. When the main focus is on security tasks, these other tasks are largely delegitimised, which in turn is supported by a strong hierarchisation of expert and other forms of knowledge.

However, guards in all museums are confronted with a dilemma between security and service, partly because visitors today expect that they can touch and try out many things, and also because regulations have become more heterogeneous. The ensuing problems in security-focused museums are obvious. But even in museums where a service orientation is also desired, guards faced many hurdles in acquiring the basic skills for these tasks and receiving recognition for them. Guards' function as a closeness-creating interface in the context of the transformation of museums is therefore often either not recognised or there are considerable (also organisational and financial) challenges to realising this potential.

The problems identified can be understood as typical for the range of tensions arising in museums in transition. [18]

3. Plurality of Methods: Opportunities and Challenges Using the Example of Museum Research

In discussing our combinatory designs above we already indicated the possibilities that arise from our plural methodological approach, but we would like to further systematise them here. The fundamental goals of mixed and multimethod designs—even before specific goals of individual designs such as exploration or increased depth are defined—are, on the one hand, to increase the complexity of the inquiry (FIELDING, 2009) and, on the other hand, to be able to better reflect on one's own role and perspective as a researcher (HESSE-BIBER & JOHNSON 2015; TASHAKKORI & TEDDLIE, 2010). This can also be seen explicitly with reference to our museum research. [19]

3.1 Making complex tensions visible through plurality of methods

When researchers are interested in fields characterised by a range of tensions, the complexity of their research increases when different actor positions, substantive dimensions, spatio-temporal processes and their (discursive) contexts are examined from different angles. The challenges of mixed methods, especially the comparability of different methods, data and findings, mean that if the scope for situating and focusing on interactions is broad, then the aim will not be to achieve greater validity of results. What can be achieved, however, are both additive and wider-ranging integrative combinations or interconnections. The latter are by no means exclusively about obtaining a more coherent picture of the research object, but partly about opposite effects, such as its defamiliarisation and being provoked by partial results: "[...] mixed methods may confuse, split, fracture, trouble, or disturb what is (thought to be) studied" (UPRICHARD & DAWNEY, 2019, p.22). Our research in museums can serve as a tangible example for how addition and irritation can be made relevant in research practice. Here we were able to consider different genres (which did not always prove to be the central line of differentiation), different actors (various professionals, guards, visitors) and different dimensions (with respect to the cultural offering: exhibition principles or visitor concepts for example; with respect to cultural consumption: visitor expectations or distinctive behaviour for example). We found it possible to establish the following combinations of perspectives and contexts:

Different perspectives are related to each other: For example, we were able to elaborate that the concepts for visitor participation held by those responsible for the exhibition do correspond in principle with the visitors' expectation that they can try out many things in the museum, but in practice a great deal of friction arises due to the fact that additional aspects also play an important role. Starting with ongoing security rules for exhibits, these include incorporating a spatial and temporal steering of the visitors into the orientation towards experiences (e.g. spatially indicating highlights or structuring time with hands-on stations). Another example is that, especially in art museums, curators and guards mutually deny each other's expertise, which, among other things, makes a cooperative division of labour more difficult. Curators rely in particular on their exclusive specialist knowledge, while guards lay claim to expertise for the visiting situation, which the curators have little knowledge of. In particular for our elaboration of (situational as well as institutionalised) processes of demarcation, it was revealing to put the different perspectives into relation to each other. Already when preparing for data collection, care should be taken to lay the groundwork for capturing such mutual relations in the ensuing analysis, for example through suitable topics in interview guidelines. We found it especially important to be able to contextualise the views of professionals and guards that they expressed in interviews and informal conversations through our observations—for example, if premises are arranged in such a way that management and guards hardly ever meet.

By using a partially sequential approach, we were able to direct our attention to questions that it would not have been possible to consider in a purely parallel design. After our non-standardised observations and conversations we could then select positions for the standardised observations and videography so as to optimise data collection, for example in relation to the following questions: How do visitors react to stagings designed to direct their attention? Which activity offerings do they use, e.g. more at the beginning or towards the end of a chronologically ordered walk through the exhibition? At which points in the exhibition are interactions between guards and visitors more likely to be expected? Can we determine from these in which context restrictive or service-oriented interactions take place? The sequential approach thus is interrelated with new or in-depth questions and by using it researchers can find indicators for the appropriate sampling (e.g. of observation points).

More generally, we can say that as far as possible we looked at phenomena in the light of different contexts—already in individual analyses, but also in the overall interpretation of partial results. This allows researchers to both change and hone their interpretation when comparing different contexts and perspectives, and not only in a complementary way. Here is a further example: After observations in one museum, activity offerings (as part of the orientation towards experiences) seemed to us to be rather moderately pronounced in the permanent exhibition, for example, when looking at hands-on stations; apparently the activities were rather shifted towards workshops and other events. In the interview with the museum director, however, it turned out that his understanding of experience also consisted in visitors making discoveries for themselves, the possible experience was not presented on a plate obvious to all. Correspondingly, listening stations were somewhat hidden. But when visitors discovered them, this was part of the visit experience. In the light of this information, we were able to further refine our definition of experience by including the component of individual discovery as part of visitors' affective engagement. We would not have achieved this more complex understanding of orientation towards experience through observation or interviews alone. When using quantitative methods, given the standardisation of instruments and survey situations, certain contexts are already predetermined to a greater extent than with qualitative methods. But this can also be taken into account in the overall interpretation. [20]

3.2 Optimising reflection on the researcher's role through plurality of methods

Using mixed and multimethods provides researchers with a further key opportunity: the possibility to reflect on their role and thus on their own situatedness in a more multi-layered way. As researchers, we inevitably entered the field with certain characteristics and presuppositions which would become clearer to us when we were confronted with other views (e.g. whether or not an exhibition is perceived as interesting or well-staged and which standards apply). Furthermore, we were also perceived in specific ways depending on the type of data collection, e.g. as researching academics or as simple (fellow) visitors. Depending on the method and role, we were seen varyingly as interested parties or troublemakers. For example, videography, which involved us less in the survey situation as researchers, was sometimes perceived as more disturbing than ethnographic shadowing, during which Jennifer EICKELMANN was able to establish a (specific) relationship with the guards. At the same time, she also had to disappoint expectations that we would potentially be able to directly improve their work situation through our research. By collecting and analysing data in a team, we also supported corresponding reflections on, or establishing situatedness of, the researcher role. In one example, the student assistant in the visitor role had perceived a guard as quite unfriendly or at least gruff towards other visitors. In the ethnographic observation, the same guard was described as friendly and service-oriented. In this way, multi-perspectivity is not only achieved through teamwork, but also through the fact that the ethnographic observation (the researcher accompanies the guard and establishes a relationship) is embedded in a different context than the observation by the student assistant in the role of the visitor (the researcher is one visitor among many who are present for a short time). Did the different assessments of the guard reflect socially desirable behaviour on her part in the context of data collection, different standards for what friendly means among team members, or just fluctuations in the guard's daily form? Here it became clear that the specific relationship between researchers and the field to be researched depends on different factors, which can now be brought into focus. Especially by comparing different observation and conversation protocols, we finally arrived at the interpretation that the guard was friendly towards visitors whom she perceived as interested and appreciative, while she was distant towards those who, according to her, behaved "as if they were in an amusement park" (field protocol, 2019, November 19, line 247). Our interpretation was that a normative attitude towards the public was being expressed rather than social desirability towards the researchers or different perceptions of the researchers, which we could empirically substantiate in this way. [21]

In summary, we found the combination of several methods to be very fruitful for our research. It has to be said, however, that the described procedure involving sequential data collection and especially context-comparative interpretations requires time—more time than researchers usually have available in a funded research project. This brings us to the challenges of methodologically plural research. In relation to such issues of research pragmatism, in the following section we elucidate two aspects in particular, namely the challenges posed by the temporality of the empirical procedure and by the comparability of data and findings. [22]

3.3 Conflicting temporalities as a challenge

One important difference between quantitative and qualitative research is the temporal sequencing of the research steps. In terms of ideal types: In more linear quantitative research, researchers already conceptualise which questions they want to clarify or which hypotheses they want to test and how they operationalise the relevant issues for measurement before commencing data collection. In qualitative research, the principle of openness applies which means that at least certain prioritisations and the order of certain tasks remain open for longer and, in research practice, data collection and analysis are iteratively intertwined (BAUR, 2019). [23]

When using parallel designs, these differences can be less important. Viewed in relation to the videography, the timing of the analysis of the social media comments on guards, for example, was not quite so central; at best, we could already sensitise ourselves to some extent to different expectations on the part of the visitors by analysing the comments. But even with parallel designs, a basic comparability must already be ensured, for example, by finding a suitable form to include in both the guides for interviews with museum professionals and in standardised categories for observations the question whether social distinction in BOURDIEU's (2005 [1979]) sense is still relevant in museums today. The situation is even more difficult in the case of sequential elements. On the one hand, there was much to be said for planning the standardised interviews and observations quite late in the research process, in order to be able to explore specific research questions with qualitative thoroughness beforehand. For example, if the intention is to investigate the extent to which respondents are experience-oriented, the concept of experience-orientation must be well defined beforehand, which was not possible in relation to museums with recourse to the state of research alone. An important element of the combination was therefore precisely to conduct the exploratory qualitative part first. However, this also meant that we had no self-collected overview data on the visitors in the specific museum for quite a long time at the start of the research project. Incidentally, there are already dilemmas in the phase antecedent to field access: in planning this, we would ideally already have had information which only emerged during our investigation. For example, we discovered there were two different staff representatives, but we could only address them after we had found out they existed. This point had not been raised during two preliminary discussions about our cooperation with the museum. [24]

Sequences (even in the qualitative strand) are not always freely chosen, and the ordering of steps of data-collection and analysis can have consequences for which data can be obtained. Opportunities for conducting longer interviews also depend on the people in the field. And once an interview has been conducted with a museum director, for example, she will usually not be spontaneously available for repeated longer conversations. For other forms of data collection, longer preparation time is needed, be it for pre-tests (we had to revise the standardised observation recording sheet several times in order to reduce demands on the observers, but still to cover central aspects of the observation) or for working on relationships in order to gain access to interesting contrasting cases (e.g. among the guards) in a snowball system. [25]

Over the years of our research in museums, we thought several times: if we had known this beforehand, we would have proceeded differently, we would have set other temporal or substantive priorities. Such thoughts cannot be prevented and are indeed characteristic of the field, which itself is not static. Some years ago, for example, in the interviews we repeatedly asked museum professionals how they felt about digital public spheres and social media presence, but it was impossible to foresee the massive expansion of these areas during the coronavirus pandemic. This refers to fundamental considerations about viewing the temporality of that which is being researched and the temporality of studies as related to each other—e.g. museums change as units of research, and linear processes between exhibition conception, implementation and consumption, for example, cannot be assumed without further ado (ABBOTT, 2001). As a principle of our methodologically plural approach, we have certainly learnt with regard to temporality that the distinction between parallel and sequential design elements can sometimes be a simplification. As a rule, in both cases one must usually be aware that for a (later) combination, sequences or at least considering the sequence of different steps and thus temporal structuring are unavoidable. Even in the case of research steps that are primarily sequential in research practice but not substantively—which needs to be distinguished first—it should not be forgotten that specific methods have their specific temporalities. If researchers attempt a synchronisation of different procedures, they may also produce friction. The balance between (on the qualitative side) openness and this structuring remains a challenge. However, actively considering the temporal implications of research is preferable to naive neglect as an approach. [26]

3.4 Comparability as an impediment to method integration

In this section we relate the aspect of comparability—which should be prepared for in data collection—to the phases of data analysis and overarching interpretation. Even taking a single museum as a case, we are dealing with different actors and substantive dimensions. A basic comparability is given because the data is always related to the same museum (similar to case studies in organisational research in general), be it in detail about museum concepts, exhibition staging, working conditions or visitor satisfaction. Nevertheless, the researcher must decide whether data and findings are related to each other in such a way that they could in principle contradict each other, or whether they relate to different contexts or are complementary in content. [27]

One example is the visitors' assessments of the guards in an art museum. In our standardised survey, we allowed open answers for this assessment question and categorised them afterwards. Of the visitors surveyed, 67% gave positive ratings (e.g. friendly, helpful; the other categories were negative, neutral and ambivalent). In the content analysis of the social media comments referring to guards at the same museum, only 41% of mentions were positive. It is not possible to say that one of the two results is more valid than the other. In view of the fact that there was no explicit incentive to evaluate the guards on the platforms, which meant that there were hardly any neutral evaluations (such as inconspicuous), and considering the limited attention span typically exhibited by users of digital platforms, rather polarised assessments are to be expected. In this context, it is actually remarkable that positive assessments were made in at least 41% of the cases. So although we are dealing here with the same phenomenon in terms of content (visitors' assessments of guards), we are dealing with different and thus not directly comparable contexts. Alternatively, we could say that researchers seek to explain contradictions in findings on the same phenomenon by considering the different contexts of the findings. Particularly with the mixed methods combination of quantitative and qualitative methods, the fact that researchers working with quantitative methods often aim to abstract from specific contexts also comes into play. Thus, the respondents to the standardised survey were implicitly asked to create a kind of average of possibly different experiences with different guards, and specific situative reasons for positive or negative assessments were not recorded. In contrast, a qualitative analysis of a video showing an interaction between a guard and a visitor is better suited for researchers to examine the situative constellation in detail, including non-verbal aspects. However, these qualitative findings cannot be linked to information on the frequency of positive/negative interactions and thus cannot be directly combined with the information from the quantitative survey or the content analysis. Qualitative sampling is not designed to count frequencies; moreover, this comparison is no longer only about different contexts of a phenomenon, but rather about different phenomena (evaluation of guards vs. interaction dynamics between guards and visitors). [28]

The question of comparability can also be linked to the discussion about the possibility of triangulation for convergent validation (DENZIN, 2012; MERTENS & HESSE-BIBER, 2012; MORGAN, 2019). In the discussions on this topic, the hurdles for validation have been repeatedly pointed out, which in our view are not least due to the limits of comparability just described. However, these limitations can be put into perspective with regard to our research: Important insights can be gained precisely by tracing these limits of comparability in specific cases, as we have indicated in the example above. For instance, the focus on complementary aspects of the question is honed if one can show more clearly through the social media comments than through the survey results which diverse—and sometimes contradictory—expectations of guards are associated with the ratings. Ideally, the guards should be courteous, helpful and competent, but at the same time not disturb or even control the self-determined visit. [29]

In connection with the search for comparability, with our principle of reading-of-insights-through-one-another (BARAD, 2007; UPRICHARD & DAWNEY, 2019) we start at an earlier point in the research process, long before the combination of partial findings that stand alone. Even during the analysis of individual data, we address the question of situatedness and comparability so that, as far as possible, we do not arrive at just a supposed comparability of partial findings. Furthermore, as mentioned above, our problematisation of comparability or our dealing with different comparison lines during the research process has led to an increased awareness of the mixed methods potentials, especially for questioning the supposed unambiguity of boundaries of the phenomena under study. During this procedure we were aware of the multiplicity of conditions that are relevant for our research questions. If we understand systematic comparisons in this way, we can use them as an instrument to diffract the alleged phenomenon in the sense of widening the scope and figuring out multiple interferences as well as handling irritating and confusing findings (and therefore the alleged phenomenon) at a certain time in the process. However, this principle cannot be applied equally to all combination goals of different mixed methods designs (e.g. not for generalisations). [30]

A next level of questioning comparability is reached when not only different actors and aspects in one museum are examined, but also museums of different genres are compared. One challenge here is to distinguish between different findings due to different effect factors or due to different research contexts. For example, do exhibition stagings differ systematically according to the museum genre? Are paintings exhibited differently from dinosaurs or everyday objects that belonged to emigrants and immigrants? Or is field access more difficult in a museum, and can one, for example, only get in touch with an object manager working for the external service provider under the supervision of the museum's public relations manager? Both can also be combined, for example if museums of certain genres systematically have higher access barriers than others. Of course, mono-methodological researchers also encounter these challenges, because this problem is not least connected with sampling, namely how close one can get to the ideals of random selection (quantitative) or theoretical saturation (qualitative). However, the challenge is even greater in methodologically plural research because, given always-limited resources, one has to ask oneself whether to go broad or deep with one's study. A multitude of museums and a multitude of different data collection methods then means, for example, that fewer resources remain for sequential approaches and intensive interpretations. If one restricts oneself to a few contrasting cases, the problem of comparability mentioned above becomes particularly acute. In our study, which was basically designed to be exploratory and iterative in developing and examining hypotheses in the sense of grounded theory, we were also unable to resolve the dilemma. However, we dealt with it by supplementing the few contrasting cases, which we researched intensively, with numerous other cases in which we then no longer employed the full breadth of our methods. We used these contrasts to check the consistency of previous findings and to situate irritations in the further research. [31]

We believe that our methodological reflections on museum research can be useful for methodologically plural researchers in general and especially for researchers addressing the interrelation of different analytical levels of organisations. In addition to the general complexity, other methodologically relevant aspects can also be found in other organisations. One example is the different relationships between people within the 18 organisation, especially at different hierarchy levels, and also between people and objects in the field and the researchers. It is necessary to build trust before embarking on data collection, and in this context it is not irrelevant in which order one applies specific methods (e.g. in order not to appear as an emissary of the employer to people lower in the hierarchy such as guards). An important strategy here is to plan enough time for trust-building access to the field. The problem of comparability arises again in data analysis when findings from expert interviews with staff higher up in the organisational hierarchy are to be compared with ethnographic conversations or standardised interviews with staff lower down in the hierarchy. In this case, we found the principle of reading insights through each other to be very helpful, even though this means reflecting on and acknowledging the limits of comparability when using different methods and data. Another example is the economic pressure that museums, like other organisations, face. For research, this means capturing different (a)synchronicities in the development of the organisation. Some concepts, ideas and practices are primarily an expression of the brand—in museums this is exhibiting art and culture. In others we find reactions to economic pressures—e.g. at least some exhibitions are designed especially for a mass market audience. For multi- and mixed methods research, it is relevant here to situate such dynamics of (a)synchronicity as a substantive finding on the effects of different methods, each of which is used to elaborate specific dimensions and perspectives. [32]

With multi- and mixed methods research, researchers can contribute to mapping the relations within their research objects, understood as complex expanses of tensions, and examining which configurations of conditions they contain. In this way, the interplay and, if necessary, the dynamics between different dimensions and perspectives present in the field can be considered, contexts can be compared, findings can be supplemented and thus a more complex view can be achieved in an overarching interpretation. Reflecting on the researcher's role, which differs according to the various methods employed, also contributes to taking different perspectives on the research object. We have seen how these principles can be made fruitful with regard to relations of inequality and power and, more precisely, practices of distinction and participation as well as (challenges of) interpretive prerogative in the museum field, when different dimensions and their tense interrelationships are taken into account. By using mixed and multimethod approaches researchers are able to view the research field or the research object museum as a spectrum in which actors, exhibition aesthetics, museum concepts and discourses are intertwined constitutively and also contentiously. In our view, it makes sense to ensure that the method mix does not only include actor-centred methods, but also procedures that allow researchers to focus on the interaction between people or between people and objects in situations. [33]

But such combinations are also accompanied by challenges and limitations. In particular, we have shown that aspects of temporality and comparability play a role here. Sequences have to be chosen reflectively; this not only applies to sequential designs but also refers to the limits to integrating linear (quantitative) and iterative (qualitative) methods. The question of the comparability of the same—or different?—phenomena in different contexts is particularly relevant in a very differentiated field of research such as museums. Here, too, there are challenges in reconciling findings from quantitative methods, where researchers work with standardisations precisely because they seek to abstract from specific contexts, and from qualitative methods, where the respective context is explicitly considered as part of data collection. A central strategy for reflecting on comparability is to include situations and interactions or practices to a greater extent than, for example, attitudes and behaviours of individual actors. Researchers must also decide between the breadth and depth of their approach and reflect on the boundaries that arise in the process. [34]

With the challenges mentioned above, we would like to reiterate that quantitative and qualitative research not only differ in their procedures, but also in their methodologies. Underlying (non-)linear and (non-)standardised procedures are principles of empirical research with different epistemological foundations and certainly also different validity criteria. Proponents of mixed methods research sometimes tend to neglect such differences when the practical combination works (CRESWELL, 2015). However, on the basis of our material, we were able to show how the differences between the method strands always have an impact on the level of practical combinations and ultimately on the research object itself and therefore need to be managed. Mixed methods are thus fruitful for reflecting on comparability within these boundaries and thus making the best possible use of the potential of combinations. [35]

We close with an outlook. During the Covid-19 pandemic, museums around the world had to close temporarily. In this situation, the increasing utilisation of digital formats in museums can be observed, not only as tools for visitors on-site, e.g. at digital hands-on stations, but also for presenting the museum to digital (platformed) publics. Examples are guided tours that can be taken from home with video conference tools, where the guide can be a human curator or even a robot. With the help of an app styled on a dating portal, users decided whether they liked digital copies of exhibits from the Badisches Landesmuseum in Germany. The app thus offered incentives for a later visit on-site and at the same time gave museum managers the opportunity to collect process-produced data on the public's preferences. The management of the Uffizi Gallery in Florence invited TikTok influencers to produce videos for the platform at the museum and so to become curators, although the involvement of algorithms must also be taken into account. These are only a few examples of the digital transformation of museums (as is also occurring in other areas of life). It is obvious that additional methods or the reformulation of existing methods are necessary in order to research these developments together with the influence of aspects of media technology (and the companies providing them), not only qualitative or quantitative content analysis of data from the internet, but also combined methods with which it becomes possible to capture certain dynamics over time, e.g. when users of digital offers later visit the museum live and are then interviewed. This makes it all the more important to keep an eye on the opportunities and limits of multi- and mixed methods research. [36]

1) BOURDIEU's (2005) model of social space is a prominent example of an approach in which lifestyles are not conceived of as independent of social positions, but as a differentiated element in social space by means of which distinction conflicts are fought out. In their work "The Love of Art. European Art Museums and their Public", BOURDIEU and DARBEL (1991 [1966/1969]) analysed this cultural distinction using the example of museum visits. Consequently, the museum visit can be considered a pronounced practice of distinction, despite the egalitarian rhetoric present in the museum field, although the diversification of museums and their publics puts the empirical analysis of distinction in museums to a hard test. <back>

2) Due to ethical concerns related to the challenge of anonymising the data, we only used the video data in internal analytical workshops. We worked with anonymised stills in academic presentations. <back>

Abbott, Andrew (2001). Time matters. On theory and method. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Alexander, Victoria D. (2020). The sociology of the arts. Exploring fine and popular forms. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Barad, Karen (2007). Meeting the universe halfway. Quantum physics and the entanglement of matter and meaning. Durham: Duke University Press.

Baur, Nina (2019). Linearity vs. circularity? On some common misconceptions on the differences in the research process in qualitative and quantitative research. Frontiers in Education, 23(4), https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2019.00053 [Accessed: December 07, 2022].

Bennett, Tony (1995). The birth of the museum: History, theory, politics. London: Routledge.

Bourdieu, Pierre (2005 [1979]). Distinction. A social critique of the judgement of taste. Abingdon: Routledge.

Bourdieu, Pierre & Darbel, Alain (1991 [1966/1969]). The love of art: European museums and their public. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Bryman, Alan E. (2004). The disneyization of society. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Burzan, Nicole (2016). Methodenplurale Forschung. Chancen und Probleme von Mixed Methods. Weinheim: Beltz Juventa.

Burzan, Nicole & Eickelmann, Jennifer (2022). Machtverhältnisse und Interaktionen im Museum. Frankfurt/M.: Campus.

Corbin, Juliet M. & Strauss, Anselm L. (2015). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Creswell, John (2015). A concise introduction to mixed methods research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Creswell, John & Plano Clark, Vicki (2017). Designing and conducting mixed methods research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Denzin, Norman K. (2012). Triangulation 2.0. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 6(2), 80-88.

Eickelmann, Jennifer & Burzan, Nicole (2022). Das Museum im Spannungsfeld von musealer Deutungsmacht und Publikumsorientierung. Zur Scharnierfunktion von Museumsaufsichten. Zeitschrift für Kulturmanagement und Kulturpolitik, 8(1), 175-207.

Fielding, Nigel (2009). Going out on a limb. Postmodernism and multiple method research. Current Sociology, 57(3), 427-447.

Henning, Michelle (2006). Museums, media and cultural theory. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

Hesse-Biber, Sharlene & Johnson, R. Burke (Eds.) (2015). The Oxford handbook of multimethod and mixed methods research inquiry. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kirchberg, Volker & Tröndle, Martin (2015). The museum experience: Mapping the experience of fine art. The Museum Journal, 58(2), 169-193.

Knoblauch, Hubert (2005). Focused ethnography. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 6(3). Art. 44, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-6.3.20 [Accessed: March 14, 2022].

Macdonald, Sharon (Ed.) (2011). A companion to museum studies. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Macdonald, Sharon; Gerbich, Christine & Oswald, Margareta von (2018). No museum is an island: Ethnography beyond methodological containerism. Museum & Society, 16(2), 138-156, https://doi.org/10.29311/mas.v16i2.2788 [Accessed: November 11, 2022].

Mertens, Donna M. & Hesse-Biber, Sharlene (2012). Triangulation and mixed methods research: Provocative positions. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 6(2), 75-79, https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689812437100 [Accessed: November 11, 2022].

Morgan, David L. (2019). Commentary—after triangulation, what next?. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 13(1), 6-14, https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689818780596 [Accessed: November 11, 2022].

Nielsen, Jane K. (2017). Museum communication and storytelling: Articulating understandings within the museum structure. Museum Management and Curatorship, 32(5), 440-455.

Reitstätter, Luise & Fineder, Martina (2021). Der Ausstellungsinterviewrundgang (AIR) als Methode. Experimentelles Forschen mit Objekten am Beispiel der Wahrnehmung von Commons-Logiken. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 22(1), Art. 6, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-22.1.3438 [Accessed: December 7, 2022].

Sarr, Felwine & Savoy, Bénédicte (2018). The restitution of African cultural heritage. Toward a new relational ethics. Report, https://www.unimuseum.uni-tuebingen.de/fileadmin/content/05_Forschung_Lehre/Provenienz/sarr_savoy_en.pdf [Accessed: December 7, 2022].

Schoonenboom, Judith & Johnson, R. Burke (2017). How to construct a mixed methods research design. Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie, 57, 107-131.

Tashakkori, Abbas & Teddlie, Charles (Eds.) (2010). The Sage handbook of mixed methods in social & behavioral research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Teddlie, Charles & Tahakkori, Abbas (2009). Foundations of mixed methods research. Integrating quantitative and qualitative approaches in the social and behavioral science. Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Uprichard, Emma & Dawney, Leila (2019). Data diffraction: Challenging data integration in mixed methods research. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 13(1), 19-32, https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689816674650 [Accessed: November 11, 2022].

Van Maanen, John (1982). Varieties of qualitative research. Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

vom Lehn, Dirk & Heath, Christian (2016). Action at the exhibit face. Video and the analysis of social interaction in museums and galleries. Journal of Marketing Management, 32(15-16), 1441-1457.

Yin, Robert K. (2014). Case study research design and methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Dr Jennifer EICKELMANN is assistant professor at the Faculty of Cultural and Social Sciences, FernUniversität in Hagen. She holds a PhD in media studies from the Institute of Media Studies of the Ruhr-University Bochum and was a long-standing research assistant in the field of social inequality and sociological museum research at TU Dortmund University. In her research, she focuses on the intersection of gender/queer media studies and the cultural sociology of social inequalities. She further develops transdisciplinary perspectives on digital cultures with a special focus on digital transformations of subjection as well as of cultural institutions, affective publics and digital forms of defiance and violence. She is co-editor of the open access book series "Digitale Kultur" [Digital Culture], Hagen University Press.

Contact:

Jun.-Prof. Dr. Jennifer Eickelmann

FernUniversität in Hagen

Fakultät für Kultur- und Sozialwissenschaften

Universitätsstraße 47

D – 58097 Hagen

E-Mail: jennifer.eickelmann@fernuni-hagen.de

URL: https://www.fernuni-hagen.de/digitale-transformation/index.shtml

Dr Nicole BURZAN is professor of sociology at the Faculty of Social Sciences at TU Dortmund University. Her research interests are social inequalities, especially from a cultural sociological perspective, sociology of time, and empirical methods/mixed methods. Fields of application are e.g. middle classes, mobility of academics, landlords, musical taste and museums. From 2017 to 2019 she was president of the German Sociological Association. Since 2020 she is (founding) dean of the Faculty of Social Sciences. She is co-editor of the book series "Standards standardisierter und nichtstandardisierter Sozialforschung" [Standards of Standardised and Non-Standardised Empirical Social Research], Beltz Juventa.

Contact:

Prof. Dr. Nicole Burzan

TU Dortmund

Fakultät Sozialwissenschaften

Emil-Figge-Str. 50

D – 442221 Dortmund

E-Mail: nicole.burzan@tu-dortmund.de

URL: https://su.sowi.tu-dortmund.de/

Eickelmann, Jennifer & Burzan, Nicole (2023). Challenges of multimethod and mixed methods designs in museum research [36 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 24(1), Art. 12, http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-24.1.3988.