Volume 24, No. 2, Art. 25 – May 2023

Situational Analysis and Digital Methods

Carrie Friese

Abstract: In this paper, I reflect upon the methodological implications of digitization and digital methods for situational analysis. I carefully read Noortje MARRES's argument for and development of what she called situational analytics. I ask how her proposal would be incorporated within a situational analysis project of digitization and funerals. I develop a provisional research design, as a kind of thought experiment, weaving my reflections on situational analysis and digital methods through an autoethnographic account of mourning in the enforced digital of the COVID-19 pandemic. I conclude with the argument that such digital methods are necessary for situational analysis to reckon with, and yet also pose a risk of erasing the embodied and affective elements of a situation. I contend that the poiesis of ethnographic research—where mediated and embodied interactions qua situations are experienced and written into language, and writing forms a necessary but always also impossible task—remains rooted in bodies and affects that are always also elements in situational analysis. We cannot lose track of those elements that also defy the digitized elements of any given situation.

Key words: digital methods; funerals; grief; situational analysis; situational analytics; autoethnography

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. Background

3. Autoethnography and Research Design

4. A Situational Analysis of Digitization and Funerals

5. Conclusion

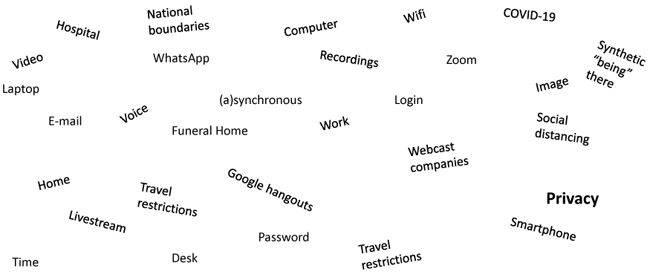

In this paper I reflect upon the methodological implications of digitization and digital methods for situational analysis, an extension of constructionist approaches to grounded theory. Rather than focusing on the practices of creating and collecting data, or coding and interpreting pieces of data, situational analysis focuses on mapping social situations based upon a range of different kinds of data (CLARKE, 2005; CLARKE, FRIESE & WASHBURN, 2018; FRIESE, CLARKE & WASHBURN, 2021). In messy maps, researchers lay out all the major actors and actants, discourses and spaces, temporalities and organizations, political economic and social cultural elements that come together in a situation of inquiry (see Figure 1 for an example of a messy map). Relational maps provide a space to consider where and how those elements come together—or don't. Here the analyst draws lines between elements, working one by one, and asking: "What is the nature of the relationship between these two elements?" Social worlds/arenas maps continue to delineate these relations, but focus on where and how different elements are bound together through patterns of commitment, partially overlapping and/or diverging in the situation of inquiry or the arena. The focus here is on the more organizational and institutional elements in a situation. Researchers use positional maps to create discursive grids of debates arising in or forming from the situation of inquiry, asking not (at first) who is articulating what position but rather how the positions themselves are articulated in discourses. These maps are thus produced as part of what we might consider analogue qualitative research, and are particularly focused on the situation as a meso-level unit of analysis. The situation of situational analysis is, ontologically, the co-constituting elements that make it up (CLARKE & KELLER, 2014). [1]

I consider questions and critiques of the situation as a unit of analysis and, relatedly, an epistemic category within digital milieu. In thinking through this question, I develop a provisional situational analysis as a kind of thought experiment. This research proposal qua thought experiment is inspired by my own experiences. I have been inspired to take this risk, in discussing the possibilities of a new project that is so personal, from Nirmal PUWAR's (2021) descriptions of and arguments for using what we carry in our bodies as the source material for our research. I think that this works very well with the grounded theory approach, which situational analysis inherits, of starting research with an interest and a curiosity rather than a specific research question. I thus weave my reflections on situational analysis and digital methods through an autoethnographic account of death and mourning in the enforced digital of the COVID-19 pandemic. [2]

To explore the place of the digital in situational analysis, I conduct a close reading and application of Noortje MARRES's (2020) "Situational Analytics." MARRES provided a methodological approach to using digital data that she has developed out of situational analysis. I extend MARRES's notion of computation muddles to also include the embodiment of such muddles, by persons who are sitting behind screens. I probe not simply screen technologies, but rather what it feels like to be at the end of that screen and the kinds of interactional muddles that result. [3]

I begin this paper with some background regarding my (lack of) experience in digital social life, before turning to two autoethnographic vignettes focused on the digitization of funerals. These vignettes are not "data" per se, but rather analytical reflections upon personal experience used in order to develop a research project. I then carefully read MARRES's argument for situational analytics, asking how this would be incorporated within a situational analysis of digitization and funerals. I conclude that MARRES provided an important approach to expand upon the infrastructural elements of situational analysis, developing the means to analyze the digital by using the digital. But I also call for a sustained focus on the poiesis of ethnographic research as well—where mediated and embodied interactions qua situations are experienced and written into language, and writing forms a necessary but always also impossible task. I would like to see the digital analyzed as not only infrastructural, but always also embodied. There is, or was, always an embodied person, sitting somewhere, behind a screen. [4]

I should start by saying that this question regarding digital methods is not an easy or comfortable question for me. I quite frankly find the digital world overwhelming; I cannot embed myself for any sustained period of time in digital worlds. I am not on Facebook or Twitter or Instagram, although did I give the first two a short-lived try. I regularly tell my students that they will need to explain Reddit or TikTok to me because I have no idea what either looks like, having given up on these types of social media some time ago. I am not a self-proclaimed luddite (yet); it is simply the case that I look on social media with about as much interest as my 96-year-old grandmother looked upon a smart phone. My qualification in addressing digital methodologies is thus rooted in my outsider status, and this is also what potentially makes my contributions unique. [5]

I also feel an obligation to engage with this question, of the relation between situational analysis and digital methodologies, as a professional sociologist and methodologist. And so I am engaging with my discomfort with digital technologies in a methodological sense, as part of the tradition of interpretative analysis and hermeneutics. To do this uncomfortable work, I drew extensively upon Noortje MARRES's (2020) critical reconstruction of situational analysis, as situational analytics, as an interpretative approach to computational settings for computational science. [6]

In her paper, MARRES critiqued the ways in which "context" in computational social science is being formalized through a focus on ritualized situations that have stable features amenable to quantitative methods—a critique that was of key concern for Adele CLARKE (2005) in developing situational analysis. MARRES (2020) argued that this focus stands in contradiction to interpretative methods, which emphasize the underdeterminacy of situations through a focus on moments of disruption in ritualized situations and the resulting repair work. She continued that this raises two related questions, regarding how to: 1. understand computational settings as contingent and 2. use computational social science to understand those settings. MARRES continued that answering these questions is important because, drawing on Karin KNORR-CETINA's (2009) concept of "Synthetic Situation," the situation is itself at risk:

"An analytic focus on stable, circumscribed situations ('flirting'; 'stop and search') implicitly or explicitly defines social life in terms of stable rituals or interactional forms, and this may put computational social science at risk of excluding from empirical analysis phenomena that look like mere contextual noise or artefacts of machinic bias: the muddles we face when finding Twitter messages littered with too many hashtags, a comment space full of advertising and spam. However, if we follow Knorr-Cetina's analysis of synthetic situations, such muddles may precisely be constitutive of the situations in which actors find themselves in computational societies" (MARRES, 2020, p.6). [7]

It is this muddle that KNORR-CETINA drew attention to, focusing on screen-based technologies. And it is this muddle that MARRES argued both formal computational science and interpretative researchers will need to seriously engage. I take this as an argument that I will need to attend to computational settings and digital methods, regardless of whether I am interested in them or not. This is not only for empirical reasons (e.g., our case studies will often include digital elements) but also for methodological reasons (e.g., digital situations are overdetermined by infrastructures). Infrastructure is an element in situational analysis generally. Meanwhile, the digital is often understood as ordinary in social studies of situations. I think that the salience of the infrastructural for digital elements therefore begs the question for situational analysis: Are digital situations unique? If so, in what ways? In order to begin to think about this question, I turn now to an autoethnographic vignette, one that will become the basis for my thinking about a research design using situational analysis and situational analytics. [8]

3. Autoethnography and Research Design

Like many people during the COVID-19 pandemic, I experienced death and the ritual of the funeral in mediated, synthetic forms. Drawing on autoethnography, I used these personal experiences to raise questions about the relationship between digital methods and situational analysis. In autoethnography, personal experience is used and analyzed as social analysis (ELLIS, ADAMS & BOCHNER, 2010). An established qualitative method in its own right, I drew upon autoethnography as another way to do reflexivity in situational analysis (MRUCK & MEY, 2019; on autoethnography and (postmodern) grounded theory methodology, see e.g., KENNEDY and MOORE, 2021; on reflexivity in qualitative research in general MRUCK, ROTH & BREUER, 2002; ROTH, BREUER & MRUCK, 2003). I focus briefly on one funeral for a friend, whom I respected very much but was not necessarily "close" to. I will be brief here, and try to speak generically, as the key point is to create a point of comparison, that made another muddle and another kind of muddle, when planning another funeral, for my father. [9]

Vignette 1: I was invited to a funeral early in the COVID-19 pandemic, when physical attendance at funerals was very limited in the UK. And so I was invited to attend this funeral online, either through livestreaming or by watching the recording of the funeral at a later date. I felt incredibly out of sorts about attending this funeral, in this manner. I recollect my cognitive processes like this: Would I have attended the funeral in person if we weren't in a pandemic? Yes. Who else would be there? I thought of all those people, put them in my mind and imagined what we would say to one another. Should I watch the livestream or the recording of this funeral? Watch the live stream; it would not mark the loss of the person if I watched a recording. I had to make this real, that this friend was gone, and so I had to, at least, be there in time—given that I was not able to be there in person. [10]

Immediately after the funeral, I wrote this in my journal:

"The sadness. How many people are having to grieve in this way? Alone, at your home office desk, in a bath robe, seeing the work on your desk as you try to take in the fact that this person is gone. Their body is in that box, that is in the centre of your computer screen, webcast." [11]

It was a muddle indeed, to be watching a funeral passively, from home and on the computer, trying to take in and make real the gravity of death through a flat screen in my home. This is a muddle made possible by digital worlds, digital worlds that I had previously stayed away from as much as possible.1) [12]

Vignette 2: My father died rather suddenly on 6 February 2021, when the UK was in lockdown. He died six days after having had heart surgery, a surgery I normally would have traveled to the United States "to be there" for. But lockdown in the UK meant I could not legally travel. My aunt, my sister and my brother would all be in Milwaukee, Wisconsin when my dad left the hospital there. I was not the only possible caregiver, and so I could not obtain a waiver to legally travel. Further, as my brother said, we did not want to risk exposing a cardiac patient to COVID-19 by my traveling internationally. I would be there for him in a better way by staying in place. And so my dad and I talked by audio and video and text messaging on WhatsApp during the time leading up to and immediately following his surgery. And he communicated his status through our family Google Hangouts group as well as to a larger group of people by e-mail. I communicated with my brother, sister and aunt in the same ways. But when my dad went into cardiac arrest, I found out by telephone. I was also told by phone that he had died. And in that week after my dad's death, almost all of our communications were by telephone. The old comfort of the phone, that technology that had always been there for us in our mediated interactions, was the one we tended to use. E-mail and Zoom were left for more formal communication and decision-making. WhatsApp and Google Hangouts were used only to ask if someone was free to talk on the phone. [13]

Because my brother and sister were in Milwaukee when my dad died, they took responsibility for organizing the funeral that had to be limited to a very small number of people who all lived locally. I could attend by Zoom. In my mind, when discussing this, I thought about my friend's funeral that was livestreamed. I imagined being a passive viewer, watching a rather professional video of my father's scripted funeral on my computer screen. I started to talk about how I guessed the funeral home could arrange that, and who we would invite. My brother interrupted me. No. That's not what he meant. My brother would do it. I interrupted my brother. Do you know how to set that up, to film it? Won't you need to be there, and not be filming? My brother interrupted me. No. I would be there by Zoom but he would rather I was the only one attending that way. This would be a small funeral and so it wouldn't be webcast. [14]

This vignette presents another kind of muddle, an interactional muddle, where the interactional form of the kind of synthetic situation we wanted to make for my dad's funeral became explicit. And, indeed, I was one of a small number of attendees, and the only person who participated by Zoom. I was digitally there, the laptop transmitting my image and voice set up on a table. I was ready to receive condolences and speak about my dad, from my desk in London. I was synthetically there for my dad's funeral, but in an entirely different way than I had been synthetically at my friend's funeral. [15]

4. A Situational Analysis of Digitization and Funerals

I have made this preliminary and messy situational map of the elements of the situation based on these experiences, where the situation is digital funerals. In making this map I asked: How might I take my experience of mourning, which was so shaped by the digital, and situate it? I used the prompts of situational analysis in order to think about the range of elements involved in this situation, and to emplace my experience socially.

Figure 1: Situational map of (my) grieving in digital societies [16]

In developing this messy map, I was struck by "privacy" as an element. Privacy was done in two different ways in the two different digital funerals that I attended. On the one hand, the more scripted and formally hybrid funeral included passwords for the attendees, and the recording was made available for a limited time. The funeral could not simply be attended by anyone, and the online participants were passive viewers. On the other hand, my father's smaller and less formal funeral was made private by limiting online attendance to me. Rather than being a passive but computationally identifiable viewer, I was a digitized person at my father's funeral. The digital was involved in two very different ways, and ideas about and practices around privacy structured this. [17]

MARRES (2020) critiqued Karin KNORR-CETINA's concept of "Synthetic Situation" (2009) for focusing on screen-based technologies, and my autoethnographic descriptions of attending funerals by webcast or Zoom would fall within this category. What this focus leaves out, according to MARRES (2020), are the infrastructures and design features of these digital situations that structure interactions. MARRES turned to situational analysis in order to gain access into these infrastructures as part of an interpretative approach to digital societies. She noted that, indeed, the infrastructural has always been a part of situational analysis. What data science makes possible is the ability to research how the digital as infrastructure is constitutive of the situation. And in the process of doing so, she further specified how and why digital situations disrupt the category of situations as a unit. MARRES argued that the digital makes new kinds of situations. She termed these "not quite situations" or "semi-situations" that occur in a "semi-field"—or what we might consider a "semi-arena":

"[The] artificial environments are explicitly designed with the purpose to render monitor-able and analys-able what happens in them. […] Computational environments like social media platforms are sufficiently 'like' other environments in society, insofar as they enable social interaction, expression and organization, yet 'they are controlled enough to facilitate intervention and manipulation of these activities, providing the artificial conditions required for the recording and analysis of these actions (Derksen & Beaulieu, 2011)' (Marres, 2017, p.53). It is in comparison to this relative artificiality of digital social life as studied in platform-based social research, that it becomes clear how, by comparison, Clarke's approach is marked by what could be called a residual naturalism" (p.7). [18]

Face-to-face interactions but also telephone calls are "natural" because they must be made into data by the researcher, by writing fieldnotes or recording an interview. What makes the digital a unique type of element in a situation that is being researched is that digital elements are always already data-in-the-making to be used by a range of actors. MARRES did not present any situational maps as such, but I think her argument matters for the ways in which I at least would make and use these maps. I interpret MARRES as saying that, in order to understand the infrastructures of digital situations, as qualitative researchers we need to engage with the digital not only as end users but also as researchers. The traditional methods of interpretative research—participant observation, qualitative interviews—allow us access to screen-based technologies but not the infrastructures that make those screen-based technologies possible. [19]

MARRES proposed an extension of situational analysis that she calls "situational analytics," rooted in a description of a research project in which researchers analyzed test drive videos of self-driving cars on YouTube. The goal of this research project was to ask if these videos could be understood as modes of evaluation regarding the introduction of something new (rather than as an analysis of a ritualized social event). The research group did this by first mapping the situational elements in a small subset of online videos. They then conducted a semi-autonomous textual analysis of a much larger group of videos using quantitative methods. However, MARRES argued that, while it was clear that the YouTube infrastructures left a mark on the videos of testing self-driving cars, the scope of the analysis did not allow them to specify this in sufficient detail. But the infrastructures also left a mark on their analysis. And this raised for MARRES the question of what level the situation of the research is constituted at: the individual video or the data set:

"While our lexicon analysis suggests that situational mapping as an interpretative method can be scaled up with the aid of automat-able, lexicon-based methods of data analysis, these methods at the same time introduce platform effects into our very delineation of the 'situation' to be interpreted" (p.10). [20]

Drawing on MARRES, it seems to me that, in order to fully understand how media architectures leave their marks, we as social researchers need to be reflexive regarding the marks left on our research itself. Infrastructures are notoriously difficult to see. As BOWKER and STAR (1999) made clear, we often cannot see infrastructures except when they break down. By using digital infrastructures to do research, research that social media has always already been designed to also do, we as researchers can begin to see how infrastructures work by asking how the digital gets imprinted upon our research. This is the operationalization of research reflexivity as research on digital infrastructures. In other words, it is not enough to note digital infrastructures in our research as an element but we need to use those infrastructures in order to see how they make the situation as a situation. [21]

I take this as the key argument MARRES (2020) was making, which situational analysts must address in order to understand the digital infrastructuralization of situations, social worlds and arenas. And so I searched YouTube for funerals. I was both surprised and not surprised to find that there are publicly available live streams and recordings of funerals on YouTube. It is therefore technically possible to study the computational settings of funerals and mourning in the same way as MARRES and her research collaborators studied test drive videos of self-driving cars. Moreover, the funeral would even be an interesting case study for such an analysis. MARRES stated that digitally mediated situations are both more disordered and more generic. The same could be said of funerals as an institutionalized way of mourning; grieving is an entirely disordering experience and yet the funeral is highly ritualized and scripted. [22]

The ethics of such a research project remains puzzling to me. But I am certain that such a project could be done, as there is already an existing field of social science and humanities researchers exploring the use of digital technologies in graveyards with QR codes, in memorializing and grieving through online social networks and recording funerals of famous people (ARNOLD, GIBBS, KOH, MEESE & NANSEN, 2017). Drawing on MARRES's intervention, I can now see that much of this literature is based on users' experiences, perspectives and practices. There is a focus on screen-based technologies, which does not take into account the computational architectures of these practices. As such, combining situational analysis with situational analytics would allow for an analysis of power that a focus on content alone cannot necessarily attend to.

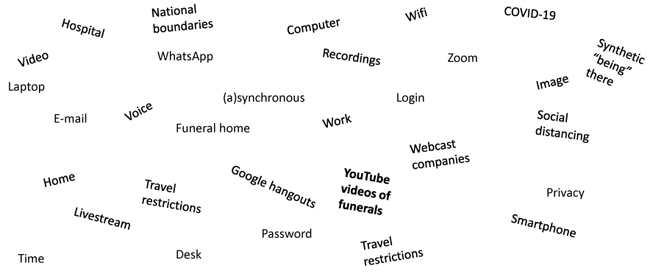

Figure 2: Situational map of (my) grieving in digital societies [23]

Adding YouTube videos to my situational map would make this type of analysis possible. It would only render one digital infrastructure visible, and one that I strategically added in order to engage in the kind of situational analytics that MARRES (2020) was developing. In other words, YouTube was not empirically present in my map. But adding these videos is a way to access the infrastructuralization of computational sciences in making the digital funeral. MARRES indeed argued that doing situational analytics involves "active curation not just of the data but of the situation under study" (p.14). We need to add elements and analyses that will allow us to surface computational infrastructures that are infamously opaque. This is entirely consistent with situational analysis and grounded theory, which both work by asking: What would I do if I added this element, or talked to this person as part of theoretical sampling? [24]

The status of these videos as publicly available on YouTube makes it possible to study YouTube's infrastructuration of digitized mourning. The digital settings of mourning presented in my autoethnographic account are not publicly available, or even recorded in the case of my dad's funeral. But watching funerals online, on YouTube, is a fundamentally different experience to attending a funeral online. Watching grief online is different from attempting to give shape and form to the physical experience that we call grief through a screen. There could conceivably be a database of no longer available recordings of funerals somewhere. And Zoom does analyse metadata from conversations held on this platform. How accessible these databases are to a researcher becomes the question. [25]

Ultimately, MARRES argued that quantification is not the key problem raised by digital methods for interpretive social sciences. Rather, it is naturalism in both computational social science and interpretive social science that is problematic. At a minimum what I think this means is that, within situational analysis, we cannot understand computational settings as equivalent to the other kinds of social settings that populate our maps. We need to ask: what kind of experiment could be conducted by using digital methods in order to surface the computational infrastructure of the situation? [26]

But in the process I think it is crucial that we also attended to the embodied and affective elements, stretching situational analysis not only along the infrastructural but also the affective. My being a digital presence at my father's funeral mattered. And it matters not only for me as a digital presence, but also as a social presence.

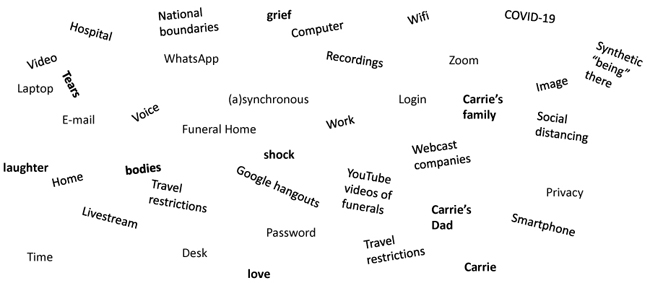

Figure 3: Situational map of (my) grieving in digital societies [27]

I understood this when I went back to my messy situational map, and remembered all of the obvious elements that I had originally left out. (It is worth saying that is something I commonly do this with these maps.) Grief makes abundantly clear the necessity to attend to the internal worlds of individual, worlds that are embodied and that struggle for expression. Grief lives in the impossible double bind of being a visceral experience that defies language—all the while also somehow urgently needing to be put into language. Grief is poiesis, and as such always defies both language and knowledge. In examining DERRIDA's understanding of the poetic, Timothy CLARK (1993) posited:

"[T]o hearken to the poetic is to attend to something, both in and beyond language, which is not 'just as it is' but whose identity is unstable, wild, impatient of definition: a mode of alterity not of sameness. It thus cannot be known: knowledge as such must be renounced if one is to perceive this creature that, unexpectedly, crosses the thoroughfares of communication, from one side to the other. The poetic moves or disturbs obliquely; its space is one in which the language of identification and exchange is traversed by what cannot be simply said or thought" (p.50). [28]

CLARK described DERRIDA's meditation on poiesis as an ode, an address or an appeal that speaks to a future that may never be, where language anticipates. "The ode may thus work performatively, giving itself as an act of dedication, worship or supplication" (CLARK, 1993, p.53). Funerals can be gatherings for doing the work of trying to make such appeals, an ode to the one now missing. Situational analysis is also a place for making such appeals, for trying to put into words those moments of presence in ethnographic research that are poetic, elusive and transitory but that move us and change us.2) [29]

I do think that situational analysis can be combined with the situational analytics that MARRES develops. It provides an important way in which digital methodologies can be integrated with both the theories and methods of situational analysis. In particular, situational analytics provide a means to surface the power of computation by making the invisible visible through research as reflexivity. This is central to the established goals of situational analysis. [30]

But I do want to hold onto the ethnographic roots of grounded theory through STRAUSS that continue to live in situational analysis. To me the ethnographic shares the double bind of the poetic, attempting to put into language that which defies language. The poetic helps us to better understand why the digitized funeral can be very challenging, as it was for me. It is hard to make real that someone you love has died, is gone forever, through a computer. What is going on here is the cognitive dissonance that digital worlds make, and that the poiesis of qualitative methods can attempt to give shape to. The ode should continue to be part of the project of situational analysis specifically, and qualitative inquiry more generally. [31]

I would like to thank Adele CLARKE for her comments on an earlier version of this paper, and for the comments and feedback from participants at the conference that led to this special issue. I would also like to thank Noortje MARRES for comments on a later version of this paper, which were crucial in helping me to refine the argument. I would also like to thank two anonymous reviewers who provided very encouraging and helpful feedback on an earlier draft of this paper. And a special thanks for the conference and special issue organizers for including me, and allowing me to develop this thought experiment. Thank you also for your incredible help in editing the paper and helping me to prepare it for publication.

1) Muddles here seem to be doing some of the analytic work that Brian MASSUMI's gestalt of the situation as its "excess" does for situational analysis. For MASSUMI (2002, p.211) naming that which makes a situation greater than the sum of its parts is "excess." The agency of the situation itself thus becomes palpable if not visible. MASSUMI (pp.209f.) further theorized, "[t]here are other ways of approaching the situation than bare-braining it. For one thing, you could try to think it. […] In other words, what is at stake is no longer factuality and its profitability but rather relation and its genitivity." The question is: What new thoughts does this nexus of productively experienced relation make it possible to think? This has been central to situational analysis, see CLARKE (2005). <back>

2) For the beginnings of my thinking regarding situational analysis and ethnographic research in this way, see FRIESE (2019). <back>

Arnold, Michael; Gibbs, Martin; Koh, Tamara; Meese, James & Nansen, Bjorn (2017). Death and digital media. London: Routledge.

Bowker, Geoffrey C. & Star, Susan Leigh (1999). Sorting things out: Classification and its consequences. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Clark, Timothy (1993). By heart: A reading of Derrida's "Che cos'è la poesia?" through Keats and Celan. Oxford Literary Review, 15(1/2), 43-78.

Clarke, Adele E. (2005). Situational analysis: Grounded theory after the postmodern turn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Clarke, Adele E. & Keller, Reiner (2014). Engaging complexeties: Working against simplification as an agenda for qualitative research today. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 15(2), Art. 1, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-15.2.2186 [Accessed: March 28, 2023].

Clarke, Adele E.; Friese, Carrie & Washburn, Rachel S. (2018). Situational analysis: Grounded theory after the interpretive turn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Ellis, Carolyn; Adams, Tony E. & Bochner, Arthur P. (2011). Autoethnography: An overview. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 12(1), Art. 10, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-12.1.1589 [Accessed: April 18, 2023].

Friese, Carrie (2019). Intimate entanglements in the animal house: Caring for and about mice. The Sociological Review, 67(2), 287-298.

Friese, Carrie; Clarke, Adele E. & Washburn, Rachel S. (2021). Situational analysis as critical pragmatist interactionism. In Dirk vom Lehn, Natalia Ruiz-Juno & Will Gibson (Eds.), The Routledge international handbook of interactionism (pp.357-368). London: Routledge.

Kennedy, Brianna & Moore, Hadass (2021). Grounded duoethnography: A dialogic method for the exploration of intuition through divergence and convergence. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 22(2), Art. 17, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-22.2.3668 [Accessed: March 28, 2023].

Knorr-Cetina, Karin (2009). The synthetic situation: Interactionism for a global world. Symbolic Interaction, 32(1), 61-87.

Marres, Noortje (2020). For a situational analytics: An interpretative methodology for the study of situations in computational settings. Big Data & Society, (7)2, https://doi.org/10.1177/2053951720949571 [Accessed: March 28, 2023].

Massumi, Brian (2002). Parables for the virtual: Movement, affect, sensation. Durham: Duke University Press.

Mruck, Katja & Mey, Günter (2019). Grounded theory and reflexivity. In Anthony Bryant & Kathy Charmaz (Eds.), The Sage handbook of current developments in grounded theory (pp.470-496). Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Mruck, Katja; Roth, Wolff-Michael & Breuer, Franz (Eds.) (2002). Subjectivity and reflexivity in qualitative research I. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 3(3), http://www.qualitative-research.net/index.php/fqs/issue/view/21 [Accessed: April 18, 2023].

Puwar, Nirmal (2021). Carrying as method: Listening to bodies as archives. Body & Society, 27(1), 3-26.

Roth, Wolff-Michael; Breuer, Franz & Mruck, Katja (Eds.) (2003). Subjectivity and reflexivity in qualitative research II. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 4(2), http://www.qualitative-research.net/index.php/fqs/issue/view/18 [Accessed: April 18, 2023].

Carrie FRIESE is associate professor in the Sociology Department of the London School of Economics and Political Science. She teaches and researches in the fields of medical sociology, science and technology studies, and animal studies using situational analysis and other relational research methods.

Contact:

Carrie Friese

London School of Economic and Political Science

Sociology Department

Houghton Street, London WC2A 2AE, UK

E-mail: c.friese@lse.ac.uk

Friese, Carrie (2023). Situational analysis and digital methods [31 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 24(2), Art. 25, https://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-24.2.4078.