Volume 25, No. 1, Art. 9 – January 2024

Making Sense of Data Interrelations in Qualitative Longitudinal and Multi-Perspective Analysis

Agnieszka Trąbka, Paula Pustułka & Justyna Bell

Abstract: In this article, we address data interrelations that social researchers face when working with qualitative data collected through in-depth interviews with longitudinal (QLR) and multi-perspective (MPR) research designs. Revisiting data from four different research projects and building on the proposal by VOGL, ZARTLER, SCHMIDT and RIEDER (2018), we present the 4C model of complexities within data interrelations. Specifically, the broader pool of data allowed us to cross-investigate how interview data may contradict, correct, complement, or be confluent with what the researcher has gathered from another interview conducted at a different point in time (longitudinally) or with another study participant (multi-perspective approach). Using different forms of transitions (e.g., transitions to adulthood, migratory transitions, transitions to parenthood) as a common analytical thread, we argue that revealing inherent inconsistencies in the data reflects the complex and ever-changing nature of reality and that making sense of these inconsistencies often enriches interpretations.

Key words: qualitative data analysis; multi-perspective research (MPR); qualitative longitudinal research (QLR); transitions; motherhood; migration; in-depth interviews

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. Methodological Features of MPR and QLR Research Designs and Data Analysis

3. Studies, Methods and Data Analyses

4. Findings: 4C Data Interrelations Model

4.1 Confluence

4.2 Complementing

4.3 Course correction

4.4 Contradiction

5. Discussion and Conclusions

One of the evident developments in social sciences' methodology is a substantial proliferation of qualitative longitudinal research (QLR), which entails interviewing the same individuals more than once (e.g., McLEOD, 2003; NEALE, 2019; NEALE & DAVIES, 2016; SALDANA, 2003; THOMSON & HOLLAND, 2003; VOGL & ZARTLER, 2021), as well as multi-perspective research (MPR)1) which involves interviewing more than one person from a predefined relational unit, such as a family, peer group, or professional setting (e.g., DUNCOMBE & MARSDEN, 1996; HEAPHY & EINARSDOTTIR, 2013). There are also emerging studies in which a combination of both designs can be found (PUSTUŁKA et al., 2021; VOGL, ZARTLER, SCHMIDT & RIEDER, 2018). The continuing advancement of such methodologies has engendered a growing interest in the dilemmas researchers may face at different stages of their projects' implementations and reporting. While strategies pertaining to certain aspects of QLR and MPR—e.g., ethics or participant recruitment—have been addressed by the literature at large (e.g., BRYMAN & BURGESS, 1994; PUSTUŁKA, BELL & TRĄBKA, 2020; WILES, CROW & PAIN, 2011), less attention has been given to the context of data analysis, i.e., working with data collected through these approaches. Therefore, in this article we focus on what we call data interrelations, which indicate situations that researchers may encounter when analyzing empirical material from interviews conducted with one person at different points in time (QLR) or with different persons from a specific unit (MPR). More precisely, a data interrelation is a relationship between two data excerpts from different interviews within a single project. [1]

Acknowledging that there are differences between QLR and MPR designs, we focus here on the aspects that connect the two, namely the question of interrelations between data that are not found in single-interview designs, because MPR and QLR inherently need to contend with the issue of (mis)alignment of the narratives collected through two interviews. Thus, we do not delve into details of data analysis in the case of QLR and MPR, but instead we propose a meta-level discussion on the interpretations of various configurations of findings coming from two datasets. [2]

Unlike previous methodological debates which largely had concentrated on a single-topic (e.g., HUGHES, HUGHES & TARRANT, 2022; VOGL & ZARTLER, 2021), e.g., detailing what to do when divergence occurs in couple interviews (HERTZ, 1995; MORGAN, ELIOT, LOWE & GORMAN, 2016), we are interested in the broader research themes that a priori have to do with fast-paced changes in people's lives in the modern world. These are typified by studies dedicated to various kinds of transitions, such as transitions to adulthood, mobile transitions/transitions of migrants and transitions to motherhood. We center on these topics because we argue that QLR and MPR designs are particularly fitting for studies of the temporal or relational dynamics of certain phenomena. [3]

In this article we offer a spectrum of analytical approaches that researchers can reflect upon when they need to bring together and interpret data from interviews conducted at different points in time or with different persons. As our main contribution, we provide insights into four possible relationships between data from different interviews, as well as possible translations of these relationships by the researchers in the process of data analysis. We call this proposal a 4C model and demonstrate how it criss-crosses the aspect of alignment between stories from two interviews and the need for researcher reflection in the face of these data (mis)alignments. Enriching the three-pronged model by VOGL et al. (2018), the "four Cs" are specifically denoted as confluence, complementing, course correction and contradiction. More broadly, through this paper we wish to encourage analytical reflexivity as a prerequisite for fully benefiting from longitudinal, multi-perspective and combined (multi-perspective longitudinal) qualitative research designs. Finally, we directly contribute to the topical debate on methods for researching processual social phenomena, such as transitions or sudden crises, as QLR and MPR are particularly fitting for grasping the dynamics of social realities. [4]

We proceed with an integrative presentation of QLR and MPR, together with opportunities and challenges associated with these designs, especially at the data analysis and interpretation stages of the research process (Section 2). Subsequently, we present the four studies from which data were sourced for this article (Section 3). The 4C model is presented in the "Findings" (Section 4), with each of the Cs separately (Sections 4.1-4.4) illustrated with data examples, our reflections and interpretative efforts. Finally, the discussion and conclusions (Section 5) reiterate our contributions and their potential implications for the research practice. [5]

2. Methodological Features of MPR and QLR Research Designs and Data Analysis

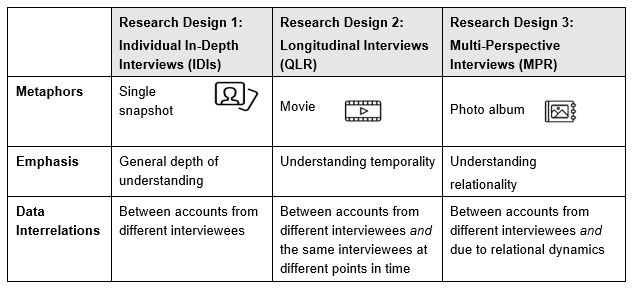

As noted above, a single interview with an isolated study participant is analogous to a snapshot, a valuable preview of the present, an interpretation of the past and the projection of the future at a particular point in life. Metaphorically, repeated interviews with the same participant over time can be imagined as a movie (NEALE, 2019), and we propose to conceptualize multi-perspective interviews with several members of the same unit as a photo album of the phenomenon acquired from different interviewees' perspectives (see Figure 1). Each of these designs serves a different purpose and brings up various challenges. In the case of the presented studies of transitions, the QLR and MPR seemed a suitable choice in offering nuanced pictures of relational and temporal dynamics. Therefore, in this section, key characteristics, use cases and previously made contributions regarding QLR and MPR designs are discussed.

Figure 1: Comparing individual in-depth interviews, longitudinal and multi-perspective research designs [6]

Longitudinal and multi-perspective interviews emerged in social research through slightly different routes. QLR has had a long tradition in anthropology as ethnographic studies in the discipline imply long stays and returns to the field (e.g., LYND & LYND, 1929, O'REILLY, 2012). Multi-perspective accounts, although codified as such only recently (KENDALL et al., 2009; VOGL, SCHMIDT & ZARTLER, 2019), have been used to map differences in (married) couples (HERTZ, 1995) and, to an extent, to initially mirror a survey method for a small unit, particularly focusing on decision-making in consumer research (WOLGAST, 1958). [7]

For MPR, DUNCOMBE and MARSDEN (1996, p.114) challenged the assumption that an individual is a sufficient analytical unit to examine relational dynamics. Hence, studies on "joint matters" such as family practices, socialization and intergenerational transfers or relations, gender orders and family budgets, often involve two or more people from one family, household or kinship structure (e.g., MORGAN et al., 2016). In the frames of typical MPR designs, several perspectives offered by members of a couple, child(ren) and their parent(s) and/or grandparent(s), relatives or friends in various peer or intergenerational matrices are collected. [8]

One could argue that the main interpretative difference between MPR and QLR comes down to the level of possible "conflict" between the perspectives of the involved individuals offered separately versus over time. This issue is especially clear in romantic dyads studied as a site of strain (HERTZ, 1995). Depending on their preferences and project resources, researchers may favor joint interviews (or the combination of individual and joint interview setup) over individual in-depth interviews (IDIs) (POLAK & GREEN, 2016). In multi-perspective interviews, participants may worry about the researcher's disclosure of information gathered across a unit (HEAPHY & EINARSDOTTIR, 2013). Simultaneously, interconnected interviewees who participate in research together with their significant others or family members, may have a tendency to create a harmonious vision and a united front in terms of presenting their relationship in positive terms (ibid.). Nevertheless, interviewing people separately can somewhat offset ethical fears, arguably granting stronger assurances about privacy and confidentiality than joint interviews (VOGL et al., 2018). [9]

For longitudinal interviews, scholars have argued that processual phenomena which include inherent change of status, situation, position or place, should reflect the pre- and post-reality of an individual's path (HOLLAND, THOMSON & HENDERSON, 2006; MILLER, 2007). Placing this "change" at the center, QLR is indispensable when researching transitions. It has been used in family studies (e.g., to track transitions to parenting; COLTART & HENWOOD, 2012; HOLLAND, 2011; MILLER, 2007; NEALE & DAVIES, 2016; VOGL et al., 2019), youth studies (e.g., to inform research on transitions to adulthood; HENDERSON, HOLLAND, McGRELLIS, SHARPE & THOMSON, 2006; KOGLER, VOGL & ASTLEITHNER, 2022; WORTH, 2009) and migration research (e.g., MULHOLLAND & RYAN, 2022; RYAN, LOPEZ RODRIGUEZ & TREVENA, 2016). All transformative adaptations to a new place of residence or a new social role, as well as transitions in a life course, are processual in nature (NEALE, 2019). This renders them prone to temporal change (justifying longitudinality) and may necessitate input from other involved individuals (justifying multi-perspectivity). Thus, these issues warrant tailored designs that equip researchers with the capacity to grasp their inherent complexity. [10]

The 21st century, particularly since 2010, has witnessed an unprecedented interest in both QLR and MPR designs, with numerous efforts invested in the systematization and codification of participant recruitment, the temporality of interviewing (e.g., spacing of waves/orders and simultaneity of interviews) and the ethical standards they call for (e.g., confidentiality) (HOLLAND 2011; McLEOD, 2003; NEALE, 2019; SALDANA, 2003; THOMSON & HOLLAND, 2003). The analytical processes concerning longitudinal and multi-perspective interview data, which lie at the center of our contribution, remain the most scarcely documented aspect of the research process for both designs (MORGAN et al., 2016; NEALE, 2019; SALDANA, 2003; THOMSON & HOLLAND, 2003; VOGL et al., 2018). Writing about separate interviews with dual-earner couples, HERTZ (1995, p.441) clarified the main dilemma by asking: "Once separate interviews are conducted, how does the researcher create a composite picture? In other words, how do we take the differences in [the] accounts to build a fuller account?" Similarly, in QLR, researchers may be faced with non-matching accounts of the same event told at different points in time, which engenders the challenge of creating a composite reel from several temporally distant accounts (NEALE, 2019). [11]

While the challenge of interpretation applies to all research designs, the epistemological questions in QLR and MPR differ slightly. Using MPR inherently acknowledges that social researchers need to grapple with the dynamics of interpersonal bonds (MORGAN et al., 2016; VOGL et al., 2019). A dataset attached to a relational unit makes it possible to discern which components or traits of a "joint matter" belong to an individual and which are collectively aligned and irreducible to single-perspective accounts (VOGL et al., 2018). In the frames of recursive interviewing, researchers look primarily at individuals, underlining that "participants are invited to review the past, update previous understandings, and re-imagine the future through the lens of the ever-shifting present" (MCLEOD, 2003; NEALE, 2019, pp.100-101). Under constructionism, drawing on multi-perspective or longitudinal data is not perceived as an analytical search for a "more objective" truth on how (different) people see certain things (at different points in time) but rather as a potentiality for richer insights into complex modern lives (BOJCZYK, LEHAN, McWEY, MELSON & KAUFMAN, 2011). [12]

As VOGL et al. (2018) pointed out, the main challenges of multi-perspective and longitudinal accounts arise not from the data collection but from the data analysis. This is also supported by HUGHES et al. (2022) when they wrote about the internal and external challenges of continuous, collective and configurative engagement with data during qualitative secondary analysis. On the one hand, for data analysis it is crucial when individual accounts can be used for comparison (BEITIN, 2008) of coherent and diverging perspectives on certain issues within a relational unit (POLAK & GREEN, 2016) or over time. On the other hand, researchers need to offer explanations for the discrepancies and inconsistencies that would otherwise "tarnish" the interpretation. In terms of temporal analysis, LEWIS (2007) and VOGL et al. (2018, p.178) enumerated three types of changes that can be traced in longitudinal studies. The first concerns narrative change in individual stories across time, the second acknowledges alterations in participants' (re)interpretations of experiences or feelings described earlier, and the third indicates that a new researcher's reinterpretation could emerge after a series of interviews. [13]

Such disagreements in people's accounts, as McCARTHY, HOLLAND and GILLIES (2003) suggested, should be appreciated because they mean that interviewees are less bounded by pre-existing scripts and may reveal challenges (e.g., changing values) that a given context entails, whether openly or tacitly. In the recent attempt at codification of contrasting stories in MPR and QLR, VOGL et al. (2018) identified 1. convergence, 2. complementing and 3. contradiction in their model. Along these lines, we identified interrelations in longitudinal and multi-perspective data at the meta-level. We present more and less coherent data interrelations and we strongly argue that "uneasy" data interrelations, although more challenging for an interpreting researcher, can pave the way to more in-depth interpretations of the studied phenomena. Following NEALE (2019, p.101), we showcase how "uncovering these intricacies and changes in perception is vital if the interior logic and momentum of a life are to be understood." Our contribution extends the discussion by presenting the types of data interrelations within the 4C model. Moreover, we broaden the thematic scope of the research taken into account to encompass the dynamism of transitions. [14]

3. Studies, Methods and Data Analyses

The empirical material used in the analysis came from four research projects focused on young adults (Table 1). Thematically, the studies explored different kinds of transitions within individual biographies, either focusing on developmental shifts, such as transitions to motherhood and to adulthood, or on structural changes, such as migration. They are also linked by the methodological framework of a qualitative longitudinal study (NEALE, 2019), with two employing multi-perspective designs. All projects were approved by the relevant research ethics committees at the implementing institutions. [15]

Following the chronological order of data collection, the first study "Psychological and Social Consequences of Multiple Migration in Childhood and Youth" (S1) covered two waves (W1, W2) of interviews with young adults of different nationalities who have experienced multiple migrations in childhood. Participants in W1 (n=53) were recruited purposefully to gather persons who have experienced at least two international migrations lasting at least three years during their school years. They were, however, diversified in terms of other characteristics such as nationality, age, family situation and countries of residence (PATTON, 1990). The study's main goal was to map the long-term biographical consequences of multiple international mobility experiences in childhood and youth (TRĄBKA, 2014). Follow-up interviews (n=20) were not part of the initial research agenda (RYAN et al., 2016) and they took place approximately 10 years after W1, focusing on persons who were in their early adulthood during W1. [16]

The second research project entitled "CEEYouth: The Comparative Study of Young Migrants from Poland and Lithuania in the Context of Brexit" (S2) spanned five waves of synchronous (semi-structures IDIs) and asynchronous interviews (HOUSTON, 2008; RATISLAVOVÁ & RATISLAV, 2014) to investigate how young migrants in the United Kingdom (UK) (from 19 to 35 years old) cope with the uncertainty and unfolding risks connected to Brexit (TRĄBKA & PUSTUŁKA, 2020). Although the project was focused on Poles and Lithuanians, only the interviews with Polish migrants were revisited for this article. The sampling was a mix of convenience (through social media and personal networks of the research team) and purposive sampling to recruit interviewees who had lived in the UK at least a year before the Brexit referendum and diversified in terms of their education, professional and family situation as well as place of residence. [17]

The third study (S3) entitled "GEMTRA: Transitions to Motherhood Across Three Generations of Polish Women" leveraged a dual longitudinal and multi-perspective design (PUSTULKA & BULER, 2022). For the former, it spanned two data collection waves: the pre-transition wave of interviews with pregnant women and a post-transition wave with them as mothers. This was dictated by general standards in researching transitions-to-motherhood, as used in seminal work by MILLER (2007). With regards to multiperspectivity, intergenerational participation of different women from the pregnant woman's family (mother, grandmother, mother in-law) was elicited due to the context of intergenerational and social change in motherhood and mothering in Poland (PUSTULKA & BULER, 2022). A purposive qualitative sampling procedure in the format focused on a homogeneous sample (PATTON, 1990) relied on a variety of recruitment methods, including researchers' personal networks, social media advertisements and project-leaflets in places frequented by expectant mothers (e.g., OB-GYN praxes, gyms with prenatal classes; PUSTULKA & BULER, 2022). Data were collected via semi-structured in-depth interviews with additional supplementary techniques (i.e., genograms, lifelines, activity cards; McGOLDRICK, GERSON & PETRY, 2020). [18]

Similarly, the fourth project, entitled "ULTRAGEN: Becoming an Adult in the Times of Ultra-Uncertainty," also follows a qualitative multi-perspective and longitudinal research design (PUSTULKA et al., 2021), dictated by the project's main research question on tracking transitions intergenerationally. Notably, only W1 of interviews had been completed and analyzed when the data for this article were being analyzed. Methods of data collection again relied on semi-structured in-depth interviews, as suitable in light of the larger research team of six interviewers (LOUBERE, 2017). As in S3, young adults (aged 18 to 35; n=35) and one parent of each (n=35) were interviewed separately. Recruitment of participants was based on purposeful qualitative selection rooted in maximum variation sampling (PATTON, 1990), accounting for several criteria. In the case of young adults, the key factors were living in a larger city, gender, education and age. The criteria monitored for their parents included gender and socioeconomic status, with a recruitment firm commissioned by the principal investigator to prevent sampling bias.

|

Title of the Project |

Dates |

Participants |

Main Theme/Type of Transition |

Design2) |

Waves3) |

|

Psychological and social consequences of multiple migration in childhood and youth (S1) |

2010- |

Young adults of different nationalities who experienced multiple migrations in childhood and youth |

Transitions to adulthood; mobile transitions (migration) |

L |

W1: 53 (2010-2012) W2: 20 (2021) |

|

CEEYouth: The comparative study of Poles and Lithuanians in the context of Brexit (S2) |

2018- |

Young Poles living in the UK for at least three years |

transitions to (migration) |

L |

W1: 41 (2019) W5: 28 (2021) |

|

GEMTRA: Transitions to motherhood across three generations of Polish women (S3) |

2018- |

Pregnant women (W1)/mothers of newborns (W2) & their mothers and grandmothers |

transitions to |

MP & L |

W1:58 W2: 42 (2021) |

|

ULTRAGEN: Becoming an adult in the times of ultra-uncertainty (S4) |

2021- |

Young adults and their parents |

transitions to adulthood |

MP |

W1:704) (2021) |

Table 1: Overview of the research projects [19]

In all four studies, the majority of the interviews from 2020-2021 were conducted online due to the COVID-19 pandemic. They were in Polish, except for S1 where English and Polish were used. All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed. The analytical proceedings presented in this article followed the strategy implemented by the authors in previous endeavors, with thematic analyses pertinent to various types of transitions generally prevailing in our past engagements with data. For this paper, the focus is on particular challenges or interesting points of inquiry that can spark a discussion about the research process. Then, the data drawn from the four above-described studies were first re-analyzed at the meta-level of repeated first-cycle coding (SALDANA, 2013) performed in the respective S1-S4 studies. In the second step, we returned to the material and focused on different interrelations between the parts of data and their implications for interpretations, especially as viewed through the prism of longitudinality or multi-perspectivity. They were subsequently collaboratively discussed in-depth, with emphasis on the data analysis approaches when questions or doubts in terms of interpretation arose. The final step included extrapolation, cross-validation, and ultimate collaborative case selection. [20]

In developing and nuancing methodological reflection, this approach of revisiting multiple studies and re-analyzing them with fellow researchers from a meta-perspective has proven both fruitful and robust. On the basis of the analyzed interrelations across S1-S4 and their respective research designs, following validations, four types of interrelations that constitute the 4C model (confluence, complementing, course correction and contradiction) were identified. [21]

4. Findings: 4C Data Interrelations Model

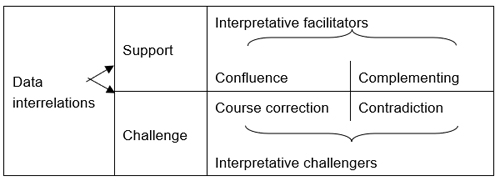

The analysis of the data interrelations revealed four main patterns that called for different strategies during the data analysis. As such, they are recounted from the perspective of the researcher engaging with the empirical material. In terms of the general relation between materials collected in QLR and MPR, the data can broadly "support" or "challenge" the story (e.g., version of the events, explanation, attitude) found across two different accounts (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: 4C model of data interrelations [22]

For the data that were coherent, mutually supportive accounts were categorized under a stronger interrelation called confluence and less-aligned, yet not completely convergent stories were put under the complementing data interrelation. From the perspective of the researcher, confluence and complementing can be seen as facilitators of interpretations. The second set of data interrelations includes course correction and contradiction, which operate more as interpretative challengers. While the latter indicates major data discrepancies, the former refers to a situation when certain interpretative adjustments are needed in the face of dissimilarity. Each data interrelation from the 4C model will now be discussed in detail, with concrete examples and interpretations. [23]

Confluent narratives characterize the interviews with data interrelations that indicate alignment, either between different interviewees (multi-perspective) or over time (longitudinal). During data analysis, the researcher does not need to grapple with distilling meanings from diverging stories and confluence echoes that accounts—multi-perspective or longitudinal—flow together and share a more or less pronounced junction. There are various reasons why the confirmation effect occurred in the discussed research designs. In a multi-perspective setting, confluence seemed connected to proximity relationships between those interviewed. The study participants appeared to have had discussions about a given issue or experience prior to being probed by the researcher for their accounts of the matter. As an example, in the mother-daughter pair consisting of Kamila and Ilona, the educational choices and transitions of the daughter were narrated in a very similar manner, with the mother's account offering little-to-no new information about the daughter's pathway.

|

"I was confident in my educational choices. I chose a high school that had high A-level results in Biology. It was one of the best-ranked schools [...]. I have wanted to be a veterinarian since I was little [...]. It is something I have held dear since childhood; it comes from my heart. Every time we visited mum's friends, my first question would be if they had pets. I had no interest in humans, just animals. I am pursuing this [...] and spend time with pets or research them whenever I can. [...] At one point, I discovered that there are more programs beyond veterinary sciences, so I ultimately chose animal engineering" (S4, Kamila, 21, daughter, W15)). |

"She was highly confident with [her educational choices]. She had good grades, so she was able to choose a school among the better ones. She had this thing, which happens rarely. When she was born, she immediately had this inherent love for animals. The moment she started speaking, she kept talking about pups and kitties. She initially wanted to be a veterinarian but decided to go for animal engineering. Everything she wants and likes to do relates to animals [...]. This has been going on for years" (S4, Ilona, 52, mother, W1). [24] |

The researcher received supporting information of what was happening in Kamila's educational life. The affirming narratives in this pair also extended to other themes, for instance, when the interviewees discussed temporary work and relationships. No alternative stories were acquired, but the interpretations could focus on the relationship between the interviewees. Specifically, it can be said that Kamila's life was well-known to her mother, who also supported her decisions. In multiple interviews with confluent general findings, it is easier to discern deeper and shared meanings, in this case, about a biographical emanation of the daughter's inborn and nurtured disposition. Hence, from an MPR stance, confluence in data interrelation can increase conviction about family processes beyond single events, illustrating patterns of communication, intergenerational interpersonal relations and views on social phenomena, such as transitions to adulthood. [25]

In a longitudinal plan, confluence occurs most often in cases of linear biographies when participants fulfill their plans and goals whilst their attitudes are not changing significantly. This is the case for Nora, who was newly pregnant and about to turn 30 during the initial interview:

"Somehow, I had already decided that I would like to, well, until I was 30, I gave myself time to experience life [...] and do various silly things [...]. In my 30s, I wanted to have a house. I wanted to have a nice job in which I would be able to grow and feel fulfilled" (S2, Nora, 29, W1). [26]

Nora also spoke about her and her partner's decision to settle down in the UK despite Brexit, with the aim of securing their stay by applying for a residence permit and then citizenship, alongside a plan to buy property. During the second interview, approximately six months later, Nora returned to the same themes, confirming that despite being very critical towards Brexit, the couple applied for settled status and planned to buy a house. She also considered an extramural degree to gain extra qualifications that would enable her to work in British schools, which was in line with her plan expressed during the first interview. During the final interview, held approximately two years after the first one, Nora was living in a new house, was working as a teacher and was newly pregnant with her second child. Although she mentioned the challenges of early motherhood during the COVID-19 pandemic, she summed up:

"Like I told you before, I am trying not to be stressed about Brexit [...]. I'm fine for now. I have the right to permanent residency here. I have the right to work. I've done my diploma nostrification and qualifications that entitle me to work here at the school" (S2, Nora, 30, W4). [27]

While subsequent interviews brought new information on the changes in Nora's life, the themes, attitudes, plans and motivations remained interconnected and in accord with what had been said previously. For a researcher working with confluence in longitudinal data, such as in the case of Nora, the empirical material can serve a similar purpose as in the above-presented MPR case. A trajectory or an event discussed at a subsequent/repeated interview is not "a mystery," and the researcher can carry out a meta-analysis of factors that led to fulfillment of the previously set out plans. [28]

In the next type of data interrelation, the researcher identifies the narratives that offer context and complementary explanations. These are particularly valuable when the topics are sensitive or, as with the ensuing example, when one person from the interviewed family is reluctant to discuss a certain topic. Magda, a highly educated professional with a lot of focus on scientific expertise in her mothering practices, was surprisingly curt and decisive about not vaccinating her baby:

"rejected the idea of vaccinations immediately after birth. I think it's a good decision. Several kids the same age as mine got sick in December, and I think it was because vaccinations harmed them. I'm more focused on immunity, but actually, I do not want to talk about it" (S3, Magda, 31, W2). [29]

With Magda's direct statement and swift subject change, the researcher did not elicit additional information on the significance of this behavior. This made the single interview quite puzzling with regard to the inconsistencies between Magda's surprising anti-vax ideals, on the one hand, and her otherwise centralized dedication to raising her child based on frequently reviewed scientific research and expert advice. Beyond this short excerpt, Magda underlined doctor check-ups and a careful selection of activities and toys for her child. The explanation that complemented the story came from Magda's mother who was interviewed within this MPR:

"My daughter's close friend had her son diagnosed with autism right after vaccination. [...] You probably also heard many similar stories. [The boy] was developing excellently, and then, at six months old, they vaccinated him. He is now autistic. Apparently, the doctor admitted it was the result of the vaccine. Magda knows this case very well. She was right there when it happened and saw the challenges regarding care and home-schooling. She even baby-sat him, so it was heart-wrenching for her. She cannot move on. She spoke to the boy's mother and made her decision about not vaccinating my grandson. [...] We discuss it at length almost every week because I think she should reconsider. [...] The topic cost her a lot of friends because she kept fighting about it, and people ridiculed her, pushed her out of mother-toddler groups, and so on. I do not think she admits to it anymore" (S3, Daniela, 62, W2). [30]

An interview with her mother makes Magda's mothering vision not only much more coherent for the researcher who can recognize the multi-layered complexities of contemporary mothering beyond just "boxing" the interviewee in as an "anti-vaxxer." The complementary account of Magda's mother shed light both on the contexts of individual experiences and on intergenerational relations. We learned that Magda had been ostracized because of her choice, which explains her reticence towards broader disclosure. The initial data interrelation with significant inconsistency benefits from complementing, thus preventing the researcher from making assumptions or misunderstanding the motivations behind the practices within transitions to motherhood. [31]

A different level of disclosure and detail between a young adult named Ela (22) and her mother, Irena (41), came from another multi-perspective dyad. Regarding the dynamic process of the transition to adulthood, both interviewees discussed the daughter's recent shift towards housing independence. The mother concisely reported conflicts:

"We had a stormy period which I think was exacerbated by my divorcing Ela's father and her health issues. We fought a lot and did not have a good relationship when she was growing up. [...] She quickly decided to move out not long after her exams. [...] She rented a flat in another town and found a job. [...] What she heard from us was that she needed to work if she decided against education. Maybe she felt pressured. [...] The moment she moved out, our relationship completely transformed and became much better, truly" (S4, Irena, 41, mother, W1). [32]

At first glance, the narrative shared by Ela is concurrent with her mother's account, as she confirmed the perceived pressure and the quick nature of her experience of transitioning out of her parents' home. However, the complementing account from the daughter revealed important contextual explanations, specifically concerning intergenerational dynamics around Ela's educational failure and sexual orientation. These remained completely silent in Irena's account, whether intentionally or subconsciously:

"My experience of leaving home happened at a very strange moment. There was this pressure for me to move out from home right after my failed A levels. [...] I had some tensions with my mum, and she emphasized that I should move out and become independent, given that I wasn't in education. [...] Once I passed the exams, the decision [...] was immediate. However, it was driven by the fact that I started a relationship with someone. [...] My father learned that I was in a (homosexual) relationship, which, at least from my perspective, meant that he just showed me the door. [...] My girlfriend and I had practical support from both sets of our parents, but it was just so fast, meaning that they just saw us together and decided that we would have it easy as a duo, so I was directed to the door" (S4, Ela, 21, daughter, W1). [33]

From the researcher's perspective, the accounts in the complementing data interrelation may not have been as mutually aligned as the ones discussed for the confluence pattern, but they were also not antithetical. In most cases, one interview (longitudinal) or interviewee (multi-perspective) offered additional information that could not have been gained from a different methodological design. The following excerpts from Daniel's life story illustrated this phenomenon in QLR. To introduce some context, Daniel, an American, spent a significant part of his childhood in Japan and Singapore. He and his brother grew up in the on-the-move setting caused by his father's jobs requiring frequent international relocations. When his father's assignments were over, the family returned to the US. Daniel went to a local high school but was very nostalgic about Japan and dreamt about returning to his beloved Tokyo. In the first interview, Daniel explained postponing his project of studying in Japan because of his father's terminal illness:

"I didn't study abroad. My dad got sick when I was in high school and he died when I was a junior in college. So I didn't want to study abroad. I mean I wanted to, but I just couldn't. I couldn't go overseas knowing that my family was going through so much in the US. I just decided that it wasn't important at that time" (S1, Daniel, 31, W1). [34]

As time passed, Daniel's mother began to recover from grief, and he began to go back and forth between the US and Japan but finally decided to stay close to his family.

"I came back in July for what was supposed to be an extended, one-month vacation, and there was too much going on here for me to justify going back to Japan right away. Opportunities started to present themselves, as well as stuff with my family that I wanted to be a part of" (S1, Daniel, 31, W1). [35]

Similar to the case of Magda, the initial interview only brushed over explanations for certain pathways that can be read as not necessarily consistent with the otherwise strong mobility desires of the interviewee. In the second interview, conducted nine years later, Daniel revealed more information about his motivations and disclosed crucial family reasons behind his decisions:

"When I left Tokyo to come back to the US, I had a return ticket that I didn't use. It was a very clear choice that I was going to stay in the US. [...] My younger brother, who was a recovering addict, was having a lot of health and mental issues, and without me there, I don't think that would've changed the way it did [...] This was a big deal like ten years ago, I don't know if we talked about it, I don't remember?

No, you've mentioned that you wanted to be close to your family [...].

I don't think any of us were comfortable, we didn't know how to talk about it. Another thing was that I didn't want to get into that discussion because it used to really upset me too, because I didn't have a real understanding of addiction at that point either" (S1, Daniel, 31, W2). [36]

The second interview illuminated Daniel's choice to forgo living in the US. From a researcher's perspective, it did not lead to changing the interpretation of Daniel's first narrative. Rather it complemented the first account in a way that fostered the process of making sense of a biographical path that the interviewee has embarked on. In essence, like in the cases of Magda and Ela, the data analysis can be more fine-tuned regarding explanations for the interviewee's decision, be it in relation to mobility, education or parenting. [37]

For all multi-perspective and longitudinal cases, complementing data interrelations additionally revealed a meta-level of the family dynamics that the researcher would not have been able to access with just one interview. In Daniel's case, the longitudinal design also introduced him to becoming the protector and source of support in his family after his father's death, the imposed role he was still struggling with during the first interview. For Ela, it revealed a family turmoil about her sexual orientation that the interview with her mother concealed. Finally, the complementing data interrelations in Magda's and Daniel's cases demonstrated the embeddedness of individuals in broader social networks and their very strong influence. While uncovering these intricacies clearly required greater attentiveness from the researchers, the resulting knowledge and insights increased the comprehensiveness of the analysis. [38]

Data interrelations grouped under course correction illustrate evolution or modifications in the interviewees' plans that do not contradict previously obtained information but rather account for structural and/or unpredictable factors that take place in people's lives due to external influences, especially socio-political crises. For instance, several interviews from S2 shed light on the evolving reactions of Central and Eastern European (CEE) migrants to the Brexit referendum and the subsequent period of negotiations and prolonged uncertainty. For instance, Monika, a young Pole who has been living in the UK for six years, described in her first interview how the referendum impacted her sense of belonging:

"Before Brexit, everything was okay, but since the referendum, I started to feel insecure. I can no longer say 100% that this is home. [...] If it turns out that I have to decide to leave, then so be it. I'm just starting to think that way anyway—that it is not permanent, what it is now. However, I would not despair if the time came for me to leave" (S2, Monika, 28, W1). [39]

However, after six months (at W2), Monika lost some of her skepticism towards her future in the UK and mentioned that she was considering buying property with her partner. After another six months, at W3, she was already living in their new home:

"We decided that if we had our own house, then we would be sure that we definitely have a place to live in, and no one would tell us that our contract was expiring. We will have something of our own, something secure. [...] We already have this house, so we have a big loan to pay back. Hence, it won't be easy to pack up and leave. In a way, we have put down roots (here)" (S1, Monika, 28, W3). [40]

In the last interview of the study, Monika reflected on her overall reaction to the Brexit process and said: "I was so scared about what would happen when Brexit becomes a reality." However, when it actually happened, Monika "had not noticed any changes" (W5), especially as she was preoccupied with the effects of the pandemic. This case may serve as an example of how slightly dissonant data from different points in time offer a more nuanced and in-depth picture of people's reactions to "unsettling events" (KILKEY & RYAN, 2021), represented here by Brexit. Whereas immediate reactions may be highly emotional and reflect a sense of radical disruption, the passage of time makes people adapt to new circumstances and normalize different risks. This slow-paced evolution cannot be tracked without a longitudinal design. While re-interpretation of data from previous interviews is typical for longitudinal studies (LEWIS, 2007; VOGL et al., 2018), we call course correction and contradiction discussed below "interpretative challengers" (see Figure 2), as they indeed require re-interpreting data from previous interviews to a greater extent than confluence and complementing. [41]

Course correction is the least tangible interrelation for multi-perspective interviews. It entails circumstances that can be assumed to affect interviewees without them necessarily knowing about it, with the researcher learning about it by analyzing multi-perspective accounts. In S3 and S4, the "blind spots" likely to warrant a course correction for a given interviewee had to do with the effects of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic crisis and its long-term implications. For example, in one mother-adult daughter dyad, it required 33-year-old Marta, who had recently become a mother, to readjust her plans about childcare, although she was only vaguely aware of it during the interview. Marta was, in fact, expecting that her parents would babysit her son so that she could go back to work, at least part-time. Unbeknownst to Marta, her mother revealed in her interview that she would not be taking on any childcare duties because she was scared that her grandson and his parents might be afflicted with communicable diseases. In that sense, while the researcher may draw on Marta's interview to formulate an assumed trajectory of her return to work, MPR allows for an interpretative course correction, indicating that her plans will not be fulfilled. [42]

A similar situation in S4 was noted concerning 28-year-old Mieszko, who, during his interview at W1, talked about his upcoming plans, being convinced that his mother would finance his start into housing independence. However, the interview with his mother, while accounting for why Mieszko may have this particular expectation of support, allowed us to deduce that the planned pathway will not be achieved.

"My husband and I had savings set aside for when the kids decided to buy an apartment, so they would get a down payment from us. The pandemic compelled me to spend this money [...] to survive, [...] to not go into debt. It nightmarishly changed my plans, but also those of my kids, because [...] more than 70% of our turnover dropped. [...] This is the only thing that the pandemic has turned upside down for me, the plans related to the kids and their apartments [...], as I would not be able to do it anymore. It is not just going to be postponed for later. I would not be able to raise the money for the kids after all" (S4, Anna, 49, W1). [43]

From a researcher's perspective, despite the lack of data on housing/financial challenges to independence being present in Mieszko's account, his mother's interview proved that a course correction in his transition to adulthood would be inevitable. With S4 leveraging both MPR and QLR, course correction data interrelations, such as the one above, can make the researchers more attuned to what to follow up on in subsequent waves. [44]

The last data interrelation traces accounts from interviews that contradict one another. This clearly poses the biggest challenge for the process of data analysis, particularly if the findings have already been partially reported based on one wave of longitudinal research or for one cohort, e.g., for all young adult respondents in MPR. In contrast to course correction, contradictory data interrelation is most pronounced in the narratives collected from two (or more) persons. However, it may also appear in longitudinal schemes, particularly when the time span between interviews is very long, as was the case in S1. Interviews with Dustin illustrated this phenomenon. During W1 conducted in 2012, Dustin, who had spent his childhood and youth moving internationally because of his father's international career, was studying in NYC. Asked about his attitude towards his parents' country of origin (Lebanon), he firmly declared reticence:

"If there was one place on earth that I didn't feel at home—it was Lebanon. Lebanon felt like (being …) in chains, like in prison. [...] I couldn't leave when I wanted to, couldn't go out with friends [...] I didn't know the language. So home [the US] was always in my imagination" (S1, Dustin, 22, W1). [45]

In line with this preference, Dustin studied in Canada and the US. While the second interview in 2021 confirmed that he was living in the US, Dustin's attitude towards Lebanon and his family heritage has shifted considerably:

"I would still consider myself very close to my family. I go back to see them maybe twice a year. I haven't been able to come back for over a year at this point, because of COVID. But I call my family on a weekly basis, I feel very close to them" (S1, Dustin, 31, W2). [46]

Dustin's relations with his family of origin changed, and his vision of the past was reworked. Although at the age of 22, he stated that Lebanon made him feel like he was "in prison" and his relationship with his mother was not particularly close, nine years later, he claimed that he had always been close with his family. Such inconsistencies, namely, undermining previous results with newer ones, constitute a challenge for data interpretation but may also prompt further and more in-depth analysis. In this interview, the researcher asked Dustin how he perceived the changes in his attitudes towards Lebanon and his family heritage. Being self-reflective and open, he explained:

"No one thing happened [...] But I think maybe halfway through my time in New York maybe I started to feel a longing for a sense of belonging at some level [...] That part of moving around so much, it gave me a longing to feel anchored in a set of traditions and also the Middle Eastern food, the food that my grandmother, my mom used to prepare for me, there is a familiarity and warmth there [...] keeping a connection to language, food, people, that allows me to feel a little bit more anchored in my life as well" (S1, Dustin, 31, W2). [47]

The two seemingly contradictory interviews elucidate the process of identity construction and the evolving need to belong. However, the choice to confront an interviewee with inconsistencies or contradictions is by no means straightforward, as the researcher must take into account ethical concerns (NEALE, 2019) and make a decision right on the spot, thereby influencing the data available for the analysis. As a result, it may well happen that a researcher does not confront the interviewee with his/her previous declarations and will have to make sense of the inconsistencies on his/her own. It also takes place in the multi-perspective scheme where ethical guidelines are clearer on intra-confidentiality and advise against confronting one person in the dyad/unit with what another interviewee has said. [48]

However, in the data collection reliant on multi-perspectivity, contradictory accounts show how stories or visions differ in the narratives set side-by-side during an analytical process. The first example demonstrates how two members of one family evaluate their bond differently:

|

"We have a good relationship. It may not be super-affectionate, but I like spending time with my mum. She's a very interesting person with lots to say. She knows a lot, creates a good atmosphere and cooks good food [...] I would say it's quite a solid bond" (S3, Marianna, 35, daughter, W2). |

"Our relationship is complicated [...] She never talks about herself or says very little. It's very hard to drag something out of her, [...] so this bond is very shallow. I help her a lot [...] but it would be hard to call it a close bond. [...] I'd maybe even say that we are emotionally, affectionately close, but it's not like we can spend time together and talk, you can forget about that" (S3, Edna, 56, mother, W2). [49] |

Discovering this type of data interrelation does not, in any way, invalidate the results of the qualitative study but guides attunement to meaning-making at an individual level, being entangled in the broader social/familial setting. Through data analyses, the researcher can offer a fine-grained interpretation as to why the perceptions of an issue or situation are that different. Hence, the case of Marianna and Edna pointed to the turbulence at the core of women's difficult relationships with their mothers, especially during transitions to motherhood. [50]

When two members of the family dyad were interviewed, the discrepancies were also interesting with regards to wider transitions and life plans rather than just evaluations. In the following example, a young adult, Julia, and her father, Piotr, differed when it came to visions of the relational futures of the younger respondent. Julia was quite ambivalent about having children and expressed skepticism about modern gender orders and trust in men as fathers:

"I'm not sure about having kids, I'm not convinced about birthing them. [...] Looking at it as a woman, I can see that it is difficult to plan a moment when having a child is worth it [...] It's difficult in terms of career and it is also hard physically. The gender division of roles does not convince me (to go for it) because I know a man can say one thing but, in a society, it would mean that I'd have to self-sacrifice fully for a child [...] I've been reading a lot about the fact that women are not feeling happy after motherhood. If I ever decided to give birth to my own child, then this would have to be a one-time thing" (S4, Julia, 20, W1). [51]

By comparison, her father believed that he had been a good male role model resulting in ascribing a standard and traditional procreative plan to Julia:

"I think my daughter wants kids. She wants a wedding, and she wants kids. She wants to have a man who will give her stability, support, and help. [...] As a father, I was a role model for her, someone to rely on, and she wants the same figure. [...] She would like to have this normal family. [...] She did not witness this classic marriage and normative family (at our home), so I believe she craves it" (S4, Piotr, 47, W1). [52]

From our perspective, the contradictions in the data were both difficult to unpack and extremely useful as a way to argue for a stronger presence of complex and qualitative research designs in lieu of surveys, which would likely not allow for divulging such matters and individual reasonings that contribute to broader social change in intergenerational attitudes. [53]

Much has been achieved recently in the field of complex qualitative research designs, giving rise to a growing scope of knowledge base that explores the challenges of analyzing and interpreting the cross-cutting levels, sources, and timepoints of the collected data (HOLLAND 2011; HOLLAND et al., 2006; HUGHES et al., 2022; KENDALL et al., 2009; McCARTHY et al., 2003; McLEOD, 2003; NEALE, 2019). However, with a few exceptions (VOGL et al., 2018), the challenges of analyzing data from QLR and MPR have not been discussed side-by-side through a joint methodological lens at the meta-level. In the existing literature, the pivotal point of such a juxtaposition was aimed at searching for means of data cohesion in situations where narratives appear inconsistent or even clashing. This is where we contribute by codifying the 4C data interrelations and extending the proposal of VOGL et al. (2018). [54]

While data interrelations, including inconsistencies, exist in every dataset, in this article we propose a way to systematize them by identifying interpretive facilitators (confluence and complementing) and intervening challengers (course correction and contradiction) present in the analytical process. Data excerpts are showcased in individual responses and recollections understood as "actively produced version(s) of the reality" that can, in turn, have various effects on people's lives (BOTTORFF, KALAW, JOHNSON, STEWART & GREAVES, 2005, p.572; see also HERTZ, 1995). We discern alignment between what HEAPHY and EINARSDOTTIR (2013, p.53) underlined in the sentiment that "several stories can be told about any relationship" in multi-perspective interviews, and its close mirroring in what NEALE (2019) has postulated about longitudinal stories and recollection of an event that changes as time goes by (see also KENDALL et al., 2009). To that end, we extend the discussion about qualitative, interviewing-based research designs by focusing on ontological and practical similarities of data analysis for QLR and MPR, rather than only addressing their inherent differences. We recognize that this aspect has a temporal frame of unfolding stages within the research process we have discussed elsewhere (PUSTULKA et al., 2019), in the sense that research aims and implementation procedures for QLR and MPR are markedly different, yet the issues encountered during data analysis may be jointly codified for both designs through the prism of 4Cs, interpretive facilitators and challengers. [55]

Researchers must acknowledge that certain social concepts situated at the meta-level of sequences and meanings rather than just facts are difficult to understand from a single-view, time-bound perspective (DUNCOMBE & MARSDEN, 1996; NEALE, 2019). Providing examples from our research projects, we strongly argue that data interrelations produce multi-layered, rich insights into social phenomena, especially those that are dynamic in nature, such as transitions. For instance, conducting MPR on transitions to motherhood and complementing a young mother's perspective with the one of another family member allows us to obtain a more nuanced understanding of this phenomenon. Along the same lines, QLR dedicated to young migrants' reactions to Brexit enables us to go beyond initial, emotional responses and follow interviewees' changing attitudes. On the whole, we argue that our proposal for understanding different data interrelations may inform other analyses of data that pertain to various types of dynamic social realities and transitions, beyond the examples of transitions-to-adulthood, mobile transitions and transitions-to-motherhood appraised here. [56]

We should highlight that the aim of introducing the MPR or QLR designs is not to validate or confirm the data we have obtained in the initial interview, but rather to gain a broader or more nuanced picture of the studied phenomenon, especially in the contexts of relational and temporal shifts. Through the examples from the research projects, we have demonstrated that data interrelations may range from confluence to contradiction. However, rather than being daunted by the inherent complexities that engender inconsistencies and discrepancies, we should take advantage of unpacking them to better understand the social world of the interviewees (VOGL et al., 2018). [57]

With the 4C model, we aimed at elevating the point of inquiry to a more comprehensive level, giving space for generalizable theoretical and methodological advancements within the process of data analysis. We hope that the data interrelations and intricacies we presented can become useful for other social scientists, particularly those interested in transitions and similar dynamic phenomena. We believe that the 4C model may become a departure point for further research on the strategies of dealing with diverse data interrelations, in particular those contrasting or contradicting each other. [58]

S1 was funded by the Priority Research Area Society of the Future under the program "Excellence Initiative – Research University" at the Jagiellonian University in Krakow.

S2 was supported by National Science Centre Poland under Daina 1 Scheme, Project No. 2017/27/L/HS6/03261

S3 was funded by the National Science Center Poland under Sonata 13 Scheme, Project No. 2017/26/D/HS6/00605.

S4 was funded by the National Science Center Poland under Opus 19 Scheme, Project No. 2020/37/B/HS6/01685.

1) In the literature the terms multi-perspective and multiple perspective research are used for this design. In this article, they are treated as synonyms. <back>

2) Longitudinal, Multi-Perspective <back>

3) Number of interviews <back>

4) S4 is an ongoing project that relies on qualitative longitudinal and multi-perspective design in its WP2 component. However, for the purpose of this article, only W1 data collected in 2021 were re-analyzed. <back>

5) Quotations (anonymized and translated from Polish where necessary) are described according to the following scheme: Number of the research project, S1, S2, S3, S4; pseudonym; age at the moment of the first interview; wave of the interview; being a child or a parent in case of multi-perspective studies. <back>

Beitin, Ben K. (2008). Qualitative research in marriage and family therapy: Who is in the interview?. Contemporary Family Therapy, 30(1), 48-58.

Bojczyk, Kathryn E.; Lehan, Tara J.; McWey, Lenore M.; Melson, Gail F. & Kaufman, Debra R. (2011). Mothers' and their adult daughters' perceptions of their relationship. Journal of Family Issues, 32(4), 452-481.

Bottorff, Joan L.; Kalaw, Cecilia; Johnson, Joy L.; Stewart, Miriam & Greaves, Lorraine (2005). Tobacco use in intimate spaces: issues in the study of couple dynamics. Qualitative Health Research, 15(4), 564-577.

Bryman, Alan & Burgess, Bob (Eds.) (1994). Analyzing qualitative data. London: Routledge.

Coltart, Carrie & Henwood, Karen (2012). On paternal subjectivity: A qualitative longitudinal and psychosocial case analysis of men's classed positions and transitions to first-time fatherhood. Qualitative Research, 12(1), 35-52.

Duncombe, Jean & Marsden, Dennis (1996). Can we research the private sphere?. In Lydia Morris & E. Stina Lyon (Eds.), Gender relations in public and private: New research perspectives (pp.141-155). London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Heaphy, Brian & Einarsdottir, Anna (2013). Scripting civil partnerships: Interviewing couples together and apart. Qualitative Research, 13(1), 53-70.

Henderson, Sheila J.; Holland, Janet; McGrellis, Sheena; Sharpe, Sue & Thomson, Rachel (2006). Inventing adulthoods: A biographical approach to youth transitions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Hertz, Rosanna (1995). Separate but simultaneous interviewing of husbands and wives: Making sense of their stories. Qualitative Inquiry, 1(4), 429-451.

Holland, Janet (2011). Timescapes: Living a qualitative longitudinal study. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 12(3), Art. 9, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-12.3.1729 [Accessed: December, 10, 2023].

Holland, Janet; Thomson, Rachel & Henderson, Sheila (2006). Qualitative longitudinal research: A discussion paper. London: South Bank University Press.

Houston, Muir (2008). Tracking transition: Issues in asynchronous e-mail interviewing. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 9(2), Art. 11, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-9.2.419 [Accessed: July 30, 2023].

Hughes, Kathryn; Hughes, Jason & Tarrant, Anna (2022). Working at a remove: Continuous, collective, and configurative approaches to qualitative secondary analysis. Quality & Quantity, 56, 375-394.

Kendall, Marilyn; Murray, Scott A.; Carduff, Emma; Worth, Allison; Harris, Fiona; Lloyd, Anna; Cavers, Debbie; Grant, Liz: Boyd, Kirsty & Sheikh, Aziz (2009). Use of multiperspective qualitative interviews to understand patients' and carers' beliefs, experiences, and needs. BMJ, 339, b4122, https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b4122 [Accessed: December 13, 2023].

Kilkey, Majella & Ryan, Louise (2021). Unsettling events: Understanding migrants' responses to geopolitical transformative episodes through a life-course lens. International Migration Review, 55(1), 227-253, https://doi.org/10.1177/0197918320905507 [Accessed: December 13, 2023].

Kogler, Raphaela; Vogl, Susanne, & Astleithner, Franz (2022). Plans, hopes, dreams and evolving agency: Case histories of young people navigating transitions. Journal of Youth Studies, https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2022.2156778 [Accessed: December 13, 2023].

Lewis, Jane (2007). Analysing qualitative longitudinal research in evaluations. Social Policy and Society: A Journal of the Social Policy Association, 6(4), 545-556.

Loubere, Nicholas (2017). Questioning transcription: The case for the systematic and reflexive interviewing and reporting (SRIR) method. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 18(2), Art. 15, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-18.2.2739 [Accessed: July 30, 2023].

Lynd, Robert S. & Lynd, Helen Merrell (1929). Middletown: A study in modern American culture. New York, NY: Harcourt Brace and Company.

McCarthy, Jane Ribbens; Holland, Janet & Gillies, Val (2003). Multiple perspectives on the "family" lives of young people: Methodological and theoretical issues in case study research. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 6(1), 1-23.

McGoldrick, Monica; Gerson, Randy & Petry, Sueli (2020). Genograms. Assessment and treatment. New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Company.

McLeod, Julie (2003). Why we interview now—reflexivity and perspective in a longitudinal study. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 6(3), 201-212.

Miller, Tina (2007). "Is this what motherhood is all about?": Weaving experiences and discourse through transition to first-time motherhood. Gender & Society: Official Publication of Sociologists for Women in Society, 21(3), 337-358.

Morgan, David L.; Eliot, Susan; Lowe, Robert A. & Gorman, Paul (2016). Dyadic interviews as a tool for qualitative evaluation. The American Journal of Evaluation, 37(1), 109-117.

Mulholland, Jon & Ryan, Louise (2022). Advancing the embedding framework: Using longitudinal methods to revisit French highly skilled migrants in the context of Brexit. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 49(3), 601-617, https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2022.2057282 [Accessed: July 30, 2023].

Neale, Bren (2019). What is qualitative longitudinal research?. London: Bloomsbury Academic Publishing.

Neale, Bren & Davies, Laura (2016). Becoming a young breadwinner? The education, employment and training trajectories of young fathers. Social Policy and Society: A Journal of the Social Policy Association, 15(1), 85-98, https://doi.org/10.1017/s1474746415000512 [Accessed: July 30, 2023].

O'Reilly, Karen (2012). Ethnographic returning, qualitative longitudinal research and the reflexive analysis of social practice. The Sociological Review, 60(3), 518-536.

Patton, Michael Quinn (1990). Qualitative evaluation and research methods. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Polak, Louisa & Green, Judith (2016). Using joint interviews to add analytic value. Qualitative Health Research, 26(12), 1638-1648.

Pustulka, Paula & Buler, Marta (2022). First-time motherhood and intergenerational solidarities during COVID-19. Journal of Family Research, 34(1), 16-40.

Pustułka, Paula; Bell, Justyna & Trąbka, Agnieszka (2020). Questionable insiders: Changing positionalities of interviewers throughout stages of migration research. Field Methods, 31(3), 241-259.

Pustułka, Paula; Radzińska, Jowita; Kajta, Justyna; Sarnowska, Justyna; Kwiatkowska, Agnieszka & Golińska, Agnieszka (2021). Transitions to adulthood during COVID-19: Background and early findings from the ULTRAGEN project. Youth Working Papers, 4, 1-65, https://swps.pl/images/STRUKTURA/centra-badawcze/mlodzi-w-centrum/dokumenty/Working-Paper_Final_201221.pdf [Accessed: December 19, 2023].

Ratislavová, Kateřina & Ratislav, Jakub (2014). Asynchronous email interview as a qualitative research method in the humanities. Human Affairs, 24(4), 452-460.

Ryan, Louise; Lopez Rodriguez, Magdalena & Trevena, Paulina (2016). Opportunities and challenges of unplanned follow-up interviews: Experiences with Polish migrants in London. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 17(2), Art. 26, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-17.2.2530 [Accessed: July 30, 2023].

Saldana, Johnny (2003). Longitudinal qualitative research: Analysing change through time. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press.

Thomson, Rachel & Holland, Janet (2003). Hindsight, foresight and insight: The challenges of longitudinal qualitative research. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 6(3), 233-44.

Trąbka, Agnieszka (2014). Being chameleon: The influence of multiple migration in childhood on identity construction. Studia Migracyjne – Przegląd Polonijny, 3, 87-105.

Trąbka, Agnieszka & Pustułka, Paula (2020). Bees & butterflies: Polish migrants' social anchoring, mobility and risks post-Brexit. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 46(13), 2664-2681, https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2020.1711721 [Accessed: December 19, 2023].

Vogl, Susanne & Zartler, Ulrike (2021). Interviewing adolescents through time: Balancing continuity and flexibility in a qualitative longitudinal study. Longitudinal and Life Course Studies, 12(1), 83-97, https://doi.org/10.1332/175795920X15986464938219 [Accessed: December 19, 2023].

Vogl, Susanne; Schmidt, Eva-Maria & Zartler, Ulrike (2019). Triangulating perspectives: Ontology and epistemology in the analysis of qualitative multiple perspective interviews. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 22(6), 611-624, https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2019.1630901 [Accessed: July 30, 2023].

Vogl, Susanne; Zartler, Ulrike; Schmidt, Eva-Maria & Rieder, Irene (2018). Developing an analytical framework for multiple perspective, qualitative longitudinal interviews (MPQLI). International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 21(2), 177-190, https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2017.1345149 [Accessed: July 30, 2023].

Wiles, Rose; Crow, Graham & Pain, Helen (2011). Innovation in qualitative research methods: A narrative review. Qualitative Research, 11(5), 587-604.

Wolgast, Elizabeth H. (1958). Do husbands or wives make the purchasing decisions?. Journal of Marketing, 23(2), 151-158.

Worth, Nancy (2009). Understanding youth transition as "becoming": Identity, time and futurity. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 40(6), 1050-1060.

Agnieszka TRĄBKA is an assistant professor and a deputy director in the Institute of Applied Psychology at the Jagiellonian University. She is a migration researcher with a background in sociology and psychology. Her main research interests include migrants' belonging and place attachment, identity, mobility in early adulthood.

Contact:

Agnieszka Trąbka

Institute of Applied Psychology, Jagiellonian University

Łojasiewicza 4

30-348, Kraków, Poland

E-mail: agnieszka.trabka@uj.edu.pl

URL: https://ips.uj.edu.pl/instytut2/pracownicy/agnieszka-trabka

Paula PUSTUŁKA is an assistant professor and head of the Youth Research Center at the SWPS University of Social Sciences and Humanities in Warsaw. She is a sociologist specializing in qualitative, multi-sited and multi-perspective longitudinal research in youth studies, migration research and sociology of families and intimate life.

Contact:

Paula Pustułka

Youth Research Center/ SWPS University in Warsaw

Chodakowska 19/31

03-815 Warszawa, Poland

E-mail: ppustulka@swps.edu.pl

URL: https://swps.pl/paula-pustulka

Justyna BELL is a senior researcher at the Norwegian Social Research-NOVA, Oslo Metropolitan University. She is a sociologist specializing in qualitative research. Her main research interests include migration, labor market attachment and family studies.

Contact:

Justyna Bell

Norwegian Social Research-NOVA

Oslo Metropolitan University

Stensberggata 26

0170 Oslo, Norway

E-mail: jubell@oslomet.no

URL: https://www.oslomet.no/om/ansatt/jubell/

Trąbka, Agnieszka; Pustułka, Paula & Bell, Justyna (2024). Making sense of data interrelations in qualitative longitudinal and multi-perspective analysis [58 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 25(1), Art. 9, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-25.1.4115.