Volume 9, No. 2, Art. 49 – May 2008

Narrative Acts: Telling Tales of Life and Love with the Wrong Gender

James Valentine

Abstract: This presentation provides an illustration of performative social science through the world's first project to focus on multi-media storytelling with a nationwide LGBT community for public representation and museum archiving. Where voices are unheard, hidden or suppressed, the images and representations of a community may be stereotyped and discriminatory, constructed about the community by those on the outside. LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender) people have experienced social exclusion and marginalisation, and their stories have been neglected or distorted. Their lives and loves have been characterised as wrong: mistaken in medical or moral terms. OurStory Scotland was established to research, record and celebrate the history and experiences of the LGBT community through their own words. Our approach combines action research and performative social science: it is participatory and emancipatory, developing the knowledge of a community through various modes of storytelling performance. This presentation reviews storytelling methods and themes, that have relevance for marginalised communities where disclosure may be problematic. The narrative acts that make up our stories range from one-liners, through written episodes, to oral history recordings, stories shared in group storytelling and narrative exchange, tales told with and through images, "text out" visual displays, "supporting stars" mapping support as an alternative to the conventional family tree, dramatisation and ceilidh performance. The stories challenge fixed and stereotyped identities, and reveal the centrality of storytelling to leading our lives. They also illustrate the rewards of performative action social research, both for a community researching itself and for dissemination more widely.

Key words: storytelling, narrative, performance, oral history, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, marginalised community

Table of Contents

1. Untold Stories

2. Narrative Acts as Performative Research

3. OurStory

4. The Story of Storytelling

5. Oral History as Performance

6. Narrative Exchange

7. Narratives of Narratives and Dramatic Monologues

8. Episodes

9. Performative Portraits

10. Speaking Out and Opening Up

11. OurStory Ceilidh: Storytelling with Dance and Music

12. Ever After

"If I sit down to tell a story and I'm in the right frame of mind, I can tell a story, and that's what I found really difficult when I came out. ... Because I wasn't confident, I felt as though I lost part of my personality." Margaret1)

"For many years I was married to a man who turned out to be gay and we had three kids together. During this time I regularly picked up or was picked up by women to have a one night stand with. I was really unhappy, in fact suicidal but did not know why. At the time I did not even consider the fact that I was a lesbian. I did not acknowledge what I was doing at all." Sandi

Being able to tell a story, and having the language to talk about yourself, can give you confidence and a strong sense of identity. Where you lack the words and the confidence to tell your story, you can feel as if you have lost your self. Telling your story may even be a matter of life and death. If you cannot name and narrate your identity, you may lose a sense of who you are, what you are doing and why it is worth continuing. "Stories are all we have to save us getting shredded in time and space." (CELYN JONES, 2001, p.48) [1]

Where we cannot recognise ourselves or our lives in terms of the available vocabulary and narratives, we cannot contribute our own stories to the common stock, and this in turn means that others cannot find suitable words and stories to tell their tale, resulting in a vicious circle of untold stories—a perpetuation of deficient repertoire, a muting of discourse. [2]

Where voices are unheard, hidden or suppressed, the images and representations of a community may be stereotyped and discriminatory, constructed about the community by those on the outside. LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender) people have experienced social exclusion and marginalisation, and their stories have been neglected or distorted. Their lives and loves have been characterised as wrong: mistaken in medical or moral terms. Their choice has been to understand themselves, if at all, in alien terms. [3]

This is both demoralising and isolating. If you cannot perform your story, presenting a suitable narrative of your life before others, you are denied the interactional feedback that acknowledges you as a viable actor: you lack the mirroring that reflects, affirms and vindicates identities and projected acts (STRAUSS, 1997). [4]

2. Narrative Acts as Performative Research

Performing our stories before others is not only individually significant: it contributes to the narrative repertoire of a community and its social and historical awareness. This paper reports on a project that combines action research and performative social science, developing the knowledge of a community through various modes of storytelling performance. [5]

Action research takes its cues from the community by, for and about whom the research is undertaken, with a view to developing the community's collective knowledge, which may be neglected or suppressed by the dominant knowledge of the society. Although they may draw on professional researchers, community members become co-researchers in a project that is participatory and emancipatory, with the aim of empowerment through collective self-awareness. This is an emergent process, in which the mode and direction of the research changes through the consciousness that develops during the ongoing research (TODHUNTER, 2001). [6]

Performance is central to the ways we research our stories, and to the ways we disseminate and make available our stories to others within and outwith the LGBT community. We research our lives by encouraging the performance of narrative acts in interactional settings that range from the intimate to the public. In collective performance of our stories, we develop the social and historical knowledge of the community, encourage further narrative acts, and provide an effective means of publication beyond immediate participants. [7]

Our stories are recognised as performative also in the sense that their form and content depends on the social context of their performance. Narrative acts do not take place in a vacuum. In acknowledgement of this, participants may perform their stories in a variety of arenas using a range of means of expression, so that the "same" story takes on a different quality. The point is not to seek a spurious objectivity, but to recognise the socially contextual aspect of all narrative acts. [8]

Performative research tends to produce plotted and explanatory accounts: as social science more generally, it imposes a coherence and rationality on the messy inconsequentiality of much of human life. Yet the transient and provisional nature of much of our storytelling operates against the slick and smooth summation of a life. In addition, most of our participants have led multiple lives with obligatory masks and apparent contradictions, that defy a simplistic teleological tale. In contrast to the trap sensed by the self-conscious author, whereby "your changeable personality in those years, with its often antithetical features, tempts you to grant it a later coherence that, despite its teleological truth, will be a subtle form of betrayal" (GOYTISOLO, 1989, p.128)2), our storytellers' lives are not presented in terms of a series of well-plotted acts that make up a coherent drama. This is despite the cultural pressures to conceive of life as a rehearsal leading up to self-realisation and self-expression through "coming out". [9]

It is not the task of this paper to present a typology of narratives of self, but it is worth noting that the coming-out narrative is just one, and is itself not always a simple story of heroic or tragic out-come. The outcome of coming out is not always definitive, and is not a one-off act, as we are continually faced with decisions as to how to identify ourselves in narrative and performative acts before, with and against others. Our stories provide provisional identifications that are inherently social. [10]

Identifying our enterprise in terms of OurStory emphasises the social nature of all identificatory narratives, along with the special objective of composing a shared heritage of the stories of a marginalised community. The adoption of the term "OurStory" highlights collective resistance to the definitional power of dominant classifications, that name you as "other", implying a whole discourse and predefined narratives (VALENTINE, 1998, 2002). Just as the feminist use of herstory drew attention to the implicit masculine perspective on history, OurStory draws attention to the telling of a marginalised community's history from its own standpoint, turning the tables on dominant identifications and narratives. [11]

This paper illustrates ways of enacting performative research with marginalised communities who are exploring their own stories. For researchers who want to conduct further exploration of the narrative content, the stories themselves are being made available as an archive in National Museums Scotland3), but the concern of this paper is rather to review a variety of ways of storytelling with a marginalised community. [12]

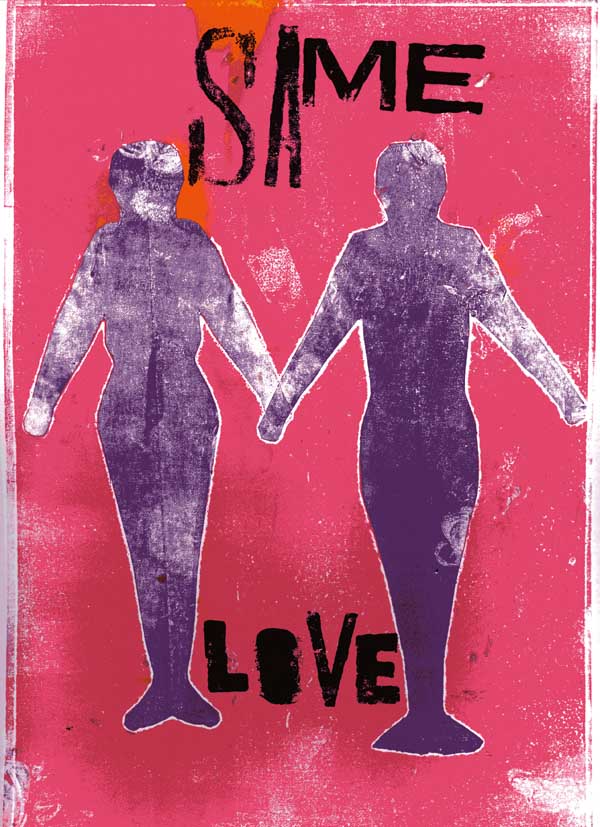

OurStory Scotland was established to research, record, and represent the history and experiences of the LGBT community in Scotland through their own words. While individual contributions may be attributed, most of our work is collectively decided and created, which entails a preference for the use of the first person plural in descriptions of our activities. OurStory Scotland was formally constituted in 2002 and was recognised as a Scottish Charity in 2004. Two major grants have been received since then, from SCARF (Scottish Communities Action Research Fund, administered by Communities Scotland) and from the Scottish Arts Council Lottery Fund for our Queer Stories project of nationwide storytelling. [13]

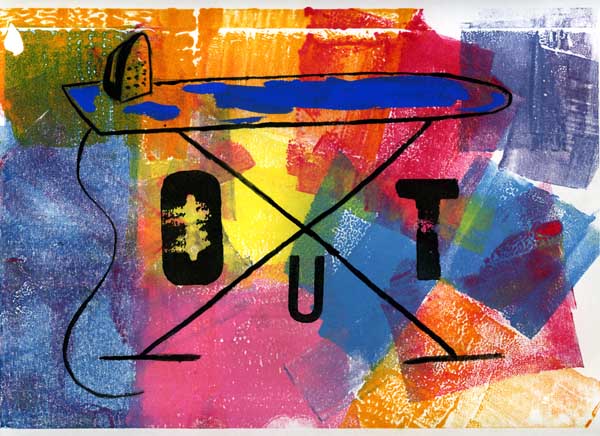

The collective, participatory and emancipatory nature of our work, that combines action research and performative social science, would not suit those researchers, or more particularly those funders, that require to know all the details of the plot and the conclusion in advance. This may make it difficult to obtain funds from conventional social science funding bodies, who may find research of this kind uncomfortably unpredictable. In contrast, the funding of our research encourages community research4), innovative methods and imaginative solutions5). These funds have enabled us to undertake storytelling throughout Scotland, and to develop new ways of storytelling on the way. [14]

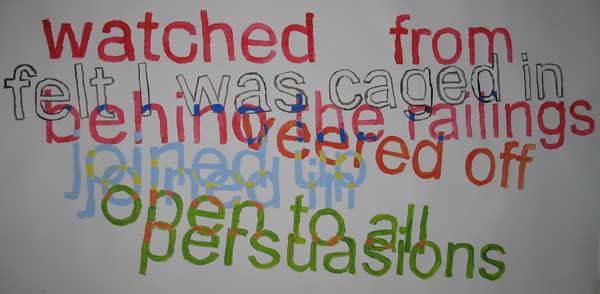

The story of how we have explored ways of storytelling is itself a narrative act that may name group or individual protagonists, indicate a trajectory, draw attention to obstacles and highlights, and suggest a conclusion that could range from happy ever after to tragedy or oblivion. This story borrows some of these features, without the ending: the stories continue to be told, and new ways of telling are constantly explored. The story of the storytelling may thus be plotted beforehand, but new characters, twists in the tale and unanticipated outcomes lead to a different account, whose conclusion is happily indeterminate: no happy ending, or rather happy no ending. [15]

The account here focuses on what has proved effective, as is appropriate to the participatory and emancipatory characteristics of action research, and provides an illustration of performative social science through the world's first project to focus on multi-media storytelling with a nationwide LGBT community for public representation and museum archiving. The storytelling methods reviewed have relevance for other marginalised communities where disclosure may be problematic, just as coming out and speaking out have been invoked for disabled and ethnic communities. [16]

The narrative acts that make up our stories comprise oral history recordings, stories shared in narrative exchange, narratives of narratives and dramatic monologues, written episodes and one-liners, visual storytelling through performative portraits, and public "speak out" events culminating in the OurStory Ceilidh. The majority of these developments were not envisaged at the outset, where we began with the intention to record and archive oral history. [17]

5. Oral History as Performance

Our first formal attempts at collecting LGBT stories followed the conventions of the oral history interview, but from the outset the social context of the interview was explicitly recognised. Our interviews take place in surroundings where the interviewee feels comfortable, often their own home, and tea and cakes are a common feature.

Illustration 1: Steph with tea and cakes

Illustration 2: Edwin with Jaffa cakes [18]

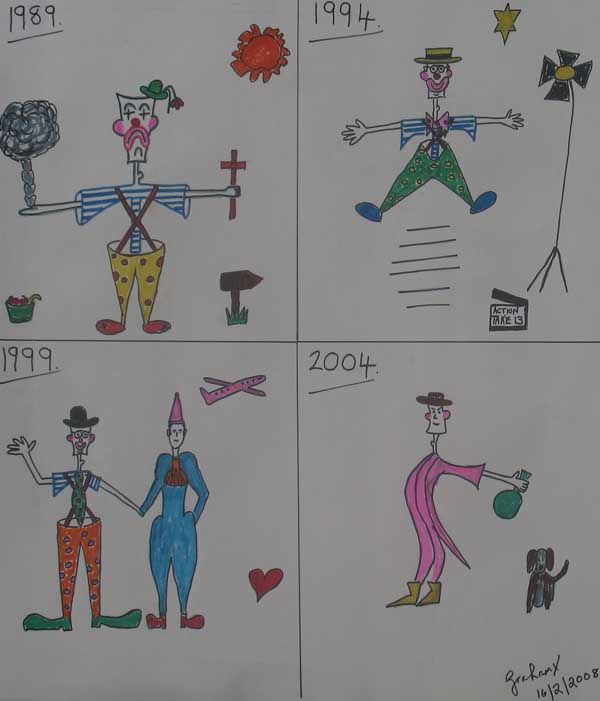

Even though many interviewees claim not to have a story to tell, prompting is in most cases minimal, as a life story develops under its own momentum. Both interviewee and interviewer are involved in a joint performance: although the interviewee is centre stage, the interviewer's gestures (silent for the sake of an uninterrupted audio recording) act as an attentive audience encouraging further narration. [19]

While the conventional model of the oral history interview may be one-to-one, many of our interviews have involved two interviewers, or an interviewer and recording monitor, and a friend of the interviewee may be present or may take part in the interview. The small group context does not appear to have inhibited the exploration of deeply personal topics, and may have provided a sense of community support. It is clear that oral history interviews are influenced by social context, and no attempt to remove or neutralise this will produce a context-free performance. Narrative acts inevitably involve presentation of self, performing for self and present or absent others. [20]

In some cases the social context of the interview has been chosen for an explicit purpose, as where two friends are interviewed together to recall common experiences, or where a couple is the subject of an interview, singly for their lives before they met, and together for their life as a couple. Again this is not to present the joint interview as truer or more profound, but simply to reflect the wish of the couple to have their shared life recorded together, and to challenge the suppression or neglect of common narratives of living and loving.

Illustration 3: Couple in garden [21]

The recording context of an oral history interview invites self-conscious performance, which lapses during a break, between the acts6). This means that what is said during a break is often of special interest, not because it is unperformed, but because it is performed differently and may include reflective remarks or tangential anecdotes considered peripheral to the main storyline. Oral historians often lament the loss of such comments off-record. In acknowledgement of this, we tell the interviewee in advance that breaks will simply start a new track on the digital recording, and that all such tracks will be erased unless we have permission from the interviewee to include them. The breaks thus still function as breaks, with greater leeway for peripheral narration, but with the opportunity to retain casual contributions that would otherwise be lost. The opening quotation from Margaret provides a telling example of a reflective comment offered during a break. [22]

Not all oral history interviews are full-scale life stories. Although we have tended to focus on lengthy interviews of several hours, we have also provided shorter opportunities for people to contribute stories from their life on record, in audio recordings in public venues, or through video recordings reminiscent of video diaries. It was originally assumed that participants would be unwilling to commit their stories to video, but the popularity of the video diary, particularly amongst younger people, has meant that many more contributions have been forthcoming than expected, especially in the social context of a public event. [23]

A collective context for oral history recordings has also been provided by group meetings, especially those directed towards reminiscence on particular themes. Themes for shared reminiscence may be suggested in advance, or at the outset by participants, or they may emerge from the handling and sharing of objects with common significance to the group, as in a reminiscence box or handling kit. We have worked with the Open Museum in Glasgow to develop a handling kit for reminiscence work with LGBT people and broader educational outreach. In the construction of the kit we have made oral history recordings on the significance of particular artefacts in people's lives. The common response to such reminiscence work is that participants find their memories are sparked by others' recollections, leading to a sharing of stories and a sense of solidarity.

Illustration 4: Reminiscence with Open Museum handling kit [24]

A further development of sharing stories is where we tell someone else's story to the group. To celebrate the opening of an exhibition of our verbal and visual storytelling at the People's Palace in Glasgow, fifty written episodes from the local area were placed in the centre of a circle of participants, from within and outwith the LGBT community. Each person chose one episode to read out to the group. In addition to hearing an episode through another's voice, further illumination was offered by participants giving their reasons for selecting that particular episode. While the expectation might be that participants would pick a tale close to their own experience, in practice most people chose a story from across the conventional borderlines that can divide the LGBT community. Their reasons for selection made it clear how they could empathise and make connections with lives that might appear very different from their own. Although this narrative exchange was not intended as an exercise in community building, that is what it became, developing a sense of solidarity around a shared history and narrative heritage.

Illustration 5: Narrative exchange at the People's Palace [25]

A real-time narrative exchange took place in Dumfries, where participants were paired off and asked to interview each other to generate a story from their life. After the exchange of stories, each person told their partner's story to the group. The creative divergence produced by retelling another's tale from memory gave a strangely liberating distance to one's own story and highlighted the provisional and performative nature of recounting our lives. [26]

7. Narratives of Narratives and Dramatic Monologues

The retelling of another's tale constitutes a narrative of a narrative. This may be deliberately undertaken to confer emotional distance or dramatic effect. Telling the story of Lynne's quilt provided both. During Lynne's illness, her friend made a quilt for her that told a visual story of key aspects of Lynne's life. At Lynne's funeral, the quilt became a focal point for a celebration of her life, and those who understood the detailed imagery explained it to others. Later a friend wanted Lynne's story to be told through the quilt at a Queer Stories performance, but feared she herself would be too upset to perform Lynne's story, and so the friend told the story of Lynne's quilt to a performer who did not know Lynne. The narrative of the narrative of the quilt's narrative of Lynne's life was told, with poignancy and dramatic power. [27]

Stories may be put together as dramatic monologues to form an effective work of theatre. In 2004 OurStory Scotland worked with 7:84 Theatre Company Scotland to create "seXshunned", which presented a series of scenes and stories from several decades of the twentieth century. We needed further stories from earlier decades, so Monte, a participant in his 80s, was interviewed about life in the 1930s—1950s. His recollections were written up, with another participant's stories from the 1960s, into a set of dramatic monologues that reiterated a phrase from Monte's story: "keep quiet" (as he had been cautioned to do about his sexuality). In the theatrical performance, the monologues were acted by others, but Monte recognised the stories as true to his own experience, with the delicious irony of the public declaration of invocations to "keep quiet".

Illustration 6: Monte in rehearsal for seXshunned [28]

Many of the scenes in our theatrical works are narratives of significant episodes told as dramatic turning points in a life story. As originally narrated they are already structured in terms of a defining moment that provides the momentum to an altered course. [29]

In a project that has engaged in many different kinds of storytelling, episodes have emerged as the single most effective method of collecting and generating stories. This is perhaps not surprising for lives that commonly feature revelations and transformations of identity. For example, the quotation from Sandi at the beginning of this paper is taken from her episode. Most of the episodes we have collected are handwritten. We have developed a printed form for submission of episodes, which explains the purpose of the contribution and the uses to which it may be put. Limited space is available for writing the episode on the form, and this ironically has meant that people are not put off by a large blank page, and of course those who get into the flow of their narration are able to continue on the reverse side of the paper. [30]

The context for writing episodes has been group storytelling or larger public events, such as Pride in Aberdeen or Pride Scotia in Glasgow and Edinburgh. In Aberdeen we hired a marquee, and displayed a selection of previous episodes to demonstrate and encourage the telling of stories. The use of a marquee prompted thoughts of telling tales in tents, with the cultural expectations of hearing one's past and future told by a clairvoyant with the use of a crystal ball and tarot cards. We adapted these conventions to present Madame Hystoria, who encouraged people into the tent and presented them with a choice of story cards that suggested potential themes for narration, such as sources of support or meeting someone significant. From a set of twelve they would choose two, and then decide which was most appropriate for them to write an episode. Where they wanted to dictate rather than write themselves, a volunteer took down their words. The OurStory Tent generated more than 60 episodes in one afternoon, along with a number of audio and video contributions and a final speak-out session.

Illustration 7: Madame Hystoria inviting into the OurStory Tent

Illustration 8: Writing episodes inside the OurStory Tent [31]

Episodes have been used in displays and exhibitions to encourage further storytelling, have featured in narrative exchange, have led to in-depth oral history recordings, and have provided material for visual storytelling that employs images and words to create a portrait in time. [32]

Visual storytelling was not originally anticipated to be a major part of the project, but the success of early trials and the support of particular artists, along with key institutions such as Dundee Contemporary Arts (DCA), convinced us of the crucial role of images in telling, publicising and generating stories. Images are employed as means of narration themselves, as well as in support of verbal storytelling, with either the words or the visuals coming first. The pictures are not static but act to convey a scene where significant action is recalled or to paint a portrait in time, that performs as or in a moving narrative. Of particular interest is the interplay of images and words, where the visual emerges from the verbal or where text comes out of pictures, to the enhancement of each. [33]

Our first attempt at visual storytelling took place at DCA Dundee and took its impetus from episodes that had already been contributed by participants, and from an exhibition of the work of RUPPERSBERG, who has worked with large print on brightly coloured background to make visual works out of text. In our storytelling venture entitled Text Out, an extract is taken from an episode, writ large and accompanied by the original episode underneath. [34]

Text Out suggests that people are coming out (or expressing something normally suppressed or silenced) through text, and also that the large text is taken out of the full text of the episode. For the viewer, it reverses a standard process of viewing, where the title is seen small underneath and the picture is viewed in full: here in a sense the title is the large print display, drawing the viewer to the fuller text beneath.

Illustration 9: Out

"I'll never forget coming out to my mum. I'd worried about it forever. I was living in Edinburgh at the time so planned a weekend to come through to Dundee to tell her. I'd never been so nervous in all my life. Saturday came and went. The knot in my stomach got bigger. I still hadn't told her. By Sunday afternoon I plucked up the courage and told her as she was doing the ironing. Her reaction wasn't as I expected. She told me she wanted me to be happy and that was all that mattered to her." Greg

Illustration 10: Behind the Railings

"In 1995 we had our first Pride march in Scotland. I wanted to be there. At first I watched it from behind the railings as the marchers came up the Mound. They waved and we waved back. But I felt I was caged in and didn't want it all to pass me by. I began walking along the pavement, parallel to the march that was going along the roadway. Gradually I matched my pace with the marchers, veered off the pavement, joined up, joined in, just before it reached the Meadows. There I was greeted by a steward—I've known her for years, and I'm sure she's straight—but who cares?—no-one should be boxed in and labelled—pride is open to all persuasions!" Jaime [35]

Text Out also encouraged a movement from verbal to visual and back to verbal, as episodes were illustrated by images and later recounted verbally (and recorded for oral history). The visual text was made to tell a fuller story. [36]

A subsequent session at DCA Dundee entitled Every Picture Tells a Story focused on the initial selection of images to tell a tale. Narrative visions were presented in photographs or through art printing, and their significance was again recounted and recorded for oral history. Symbols and imagery included scenes or occasions, for example of a significant meeting or a decisive moment, portraits of self or associates, and visions of what might be—wishes and desires that otherwise tend to be neglected in accounts of a life and yet lend it momentum and drive.

Illustration 11: Same Love

Illustration 12: Participants in Every Picture Tells a Story [37]

Narrative visions may characterise not just oneself but also others, attempting to capture defining characteristics or even to caricature. [38]

In Inverness we commissioned from artist Aileen GRAHAM caricatures of the Nessie Girls, a name chosen by a group of gay women and T-girls7), with perhaps unconscious sending up of John KNOX's "monstrous regiment of women". Permission for the portraiture was given by the participants beforehand, and they gave approval to the resultant pictures. The caricatures were informed by episodes and oral histories told by the women, so that they functioned as performative portraits of the participants, depicting them in characteristic actions and identifications. [39]

The Nessie Girls went on to become a name adopted by the participants at our culminating event in Inverness entitled Diverse Stories Day. The Nessie Girls and their friends posed in front of a display of the caricatures, accompanied by episodes that had informed them.

Illustration 13: Nessie Girls [40]

The caricatures were also copied larger than life as textile prints for display at the OurStory Ceilidh, as described below. With other portraits and the presence of the participants themselves, this public show incorporated simultaneous performances of identity. [41]

Caricature and cartoon were employed in sequence at a storyboard workshop in Glasgow, where participants were invited to create a comic strip of their lives. Stories could range from a brief episode to a reflection on a whole life. The workshop revealed ways in which a long narrative can be stripped down into a small sequence of drawings with minimal verbal explanation. For example, the stages of a relationship, with its opponents and supporters, were recounted in a sequence of four panels:

Illustration 14: Comic strip Amy [42]

Other narratives incorporated the shifting performance of self over time—for example, to portray 20 years of life through a comic strip:

Illustration 15: Comic strip Graham [43]

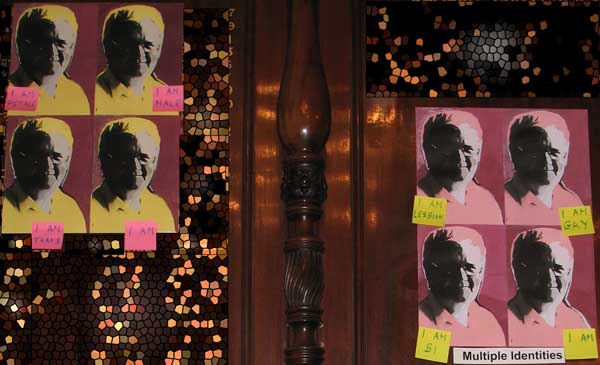

In recognition that our self-conception changes over time and according to social context, we held a workshop at DCA Dundee entitled Expressions of OurSelves. Here we celebrated multiple identities through the creation of Warhol-type screenprints. These were informed by changing or ambiguous identification expressed in episodes or oral history recordings. The variations of colour and printing allowed subtle differences to symbolise diverse identities, most notably of Steph, who had been the subject of our first oral history interview. Steph is an intersex person who enjoys multiple gender and sexual identities. Two sets of four screenprint portraits were created of Steph: one set expressed multiple defined and undefined gender identities (I am female, I am male, I am trans, I am), while the other set expressed multiple defined and undefined sexual identities (I am lesbian, I am gay, I am bisexual, I am). The two sets were printed as large-scale posters and displayed amongst the invariably male names of the Deacon Conveners in the austere Trades Hall where the OurStory Ceilidh was held. For our subsequent exhibition OurSpace, Steph's multiple portraits have been incorporated into two Chinese-style lanterns, with a subtly different screenprint for each of the four sides.

Illustration 16: Multiple identity posters

Illustration 17: Multiple identity lanterns [44]

Multiplicity is not just associated with alternative identities, but with the many masks we have adopted in our lives. [45]

Our mask workshop in Glasgow began with a discussion of the masks we have donned or felt obliged to wear in various social contexts. Blank masks, made in advance using papier mache, were painted and decorated by participants. A notable feature was the number of participants who expressed ambiguity, duality or multiplicity in the masks themselves.

Illustration 18: Mask Criz

Illustration 19: Mask Anne [46]

At the conclusion of the workshop, participants were invited to speak about the significance of their masks in front of the whole group and on film. The majority opted to enact these performative portraits, either beside or through their masks, and the results were moving and illuminating.

Video 1: Masks—Criz and Anne speaking of the significance of their masks

at the OurStory Scotland mask workshop, Glasgow, June 2007 [47]

Some participants noted that they would not have felt able to express themselves verbally in this way without the support of the visual narrative incorporated into the masks. [48]

One of the stories envisaged from the outset of our project has been the neglected narrative of sources of support for LGBT people. In a cultural and political climate where the family is often lauded as the mainstay, the other sources that LGBT individuals draw on for support are unacknowledged, underestimated or ignored. In response to this we have developed a vision of Supporting Stars. Here models of support are constructed visually, breaking away from the bloodline "family tree" structure and creating virtual maps of a range of support. We have tried two-dimensional representations, but 3-dimensional mobiles hanging from the ceiling were especially effective for conveying multiplicity of support and interconnections.

Illustration 20: Supporting Stars at DCA Dundee [49]

In an interaction between the visual and the verbal, these models of support were then recounted verbally and recorded, through audio-recording in Dundee and video-recording in Inverness. The theme of Supporting Stars gave further backing to the performers as stars of the narrative of their support networks. [50]

10. Speaking Out and Opening Up

A supportive atmosphere is vital for speaking out, and can encourage an opening up—both in the personal sense of communicative disclosure and in the social sense of affording access to a wider public. Speak out sessions have often followed a workshop on visual storytelling, where performers have developed confidence in expressing themselves in alternative ways, encouraged by other participants. A positive ambience for speaking out is also created through appropriate surroundings, including visual images created by participants and others in the community. Thus for Diverse Stories Day in Inverness, the Nessie Girls caricatures, along with the Supporting Stars constructed on the day itself, gave solidarity and support to the performers in the speak out session.

Video 2: Island in the Rain—Kimm performing at the Speak Out session

during Diverse Stories Day, Inverness, June 2006 [51]

Initially we had been advised by participants and community workers that a publicly advertised event with open access in a smaller city like Inverness would not work. Outside the larger cities the LGBT community can feel more vulnerable: mere attendance at an openly LGBT event might publicly identify people and lead to discrimination and social exclusion. In Inverness this meant that the culminating event was originally planned to be advertised only to LGBT people. After eight months of working on this project, local participants discussed this amongst themselves and made a collective and unanimous decision to open the event up to all who wished to attend, and to advertise using the local press. This would have been unthinkable at the beginning of the project. In addition, the Inverness event saw a remarkable degree of cooperation, most notably in the Nessie Girls, between different sections of the LGBT community, that has surprised volunteers and community workers elsewhere. [52]

The opening up to a wider public that was witnessed in Inverness has been an intrinsic characteristic of large-scale events and exhibitions held in Glasgow and Aberdeen. Pride events are open to all: the OurStory Tent at Pride in Aberdeen and our storytelling stall at Pride Scotia in Glasgow were both very public venues, and many of those who came across our stories were not from the LGBT community. We received positive feedback from this wider public, who could find a connection with the stories or even see a reflection of their own lives and loves. They were also able to contribute stories themselves, including the following from a 10 year old participant in the OurStory Tent in Aberdeen:

"I don't care about gay people or lezbiens because my anties a lezbien. Thank you for listnen." [53]

At the People's Palace in Glasgow, our exhibition of visual and verbal storytelling in February-March 2007 was held in the most open and frequented part of the buildings, the Winter Gardens, one of the most accessible and public art spaces in Glasgow. In a congratulatory letter from museum staff following the exhibition, it was estimated that during its six weeks the exhibition would have been viewed by 25% of the 45,000 visitors, namely more than 11,000. [54]

In early 2008 our exhibition ROUND...AB...OUT was held in the much frequented student union of Robert Gordon University in Aberdeen, fronting onto a busy street with many passers-by. The building is open to all, and accessible 7 days a week during extended hours. Yet even those who did not cross the threshold would be aware of the exhibition as, appropriate to its name, it was visible both inside and out, including window displays and murals on the outside walls. It incorporated a variety of innovative means of storytelling, including questionnaires, graffiti, dolls and plates.

Illustration 21: RoundABout plates [55]

It was not only attendance at the exhibition that was open. Evaluation was available to all, in the form of a feedback sofa: while sitting on the sofa, centrally placed to view the exhibition, people were encouraged to write comments on the sofa cover in a collective and highly public compilation.

Illustration 22: Feedback sofa [56]

Even the artworks themselves, many of which were created in LGBT friendly places that are used also by straights, were not exclusive and were contributed by people of all genders and sexualities. The crucial factor is the context, that was supportive of LGBT people's contributions and which turns about the minority/marginalised status accorded to LGBT stories by the dominant culture. The exhibition was opened by the Lord Provost of Aberdeen, and incorporated a speak out session featuring episodes collected in Aberdeen.8) [57]

Opening up space for untold stories has been a key aim of OurStory Scotland from its inception. A high point in claiming space for our stories has been our exhibition OurSpace at the Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum in Glasgow in February-March 2008.9) The Kelvingrove is the UK's largest civic museum and art gallery, and is Scotland's most visited attraction. The exhibition featured multi-media storytelling, including performative portraits created through visual storytelling, a narrative map of Glasgow indicating significant spaces in our lives and connecting with stories told elsewhere in the exhibition, and a weatherhouse showing movements in and out according to the socio-political climate.

Illustration 23: Weatherhouse [58]

Oral histories and video performances were included in the exhibition through a listening post of audio extracts, and a looped DVD of storytelling performances. The exhibition was designed:

"to provide a public space where LGBT people can find a reflection of their own lives, where other communities can gain inspiration to explore different ways of narrating and representing identities, and where everyone can understand and celebrate the diversity of lives in contemporary Scotland." (OURSTORY SCOTLAND, 2008) [59]

To announce the opening of the exhibition, there was a drumming performance by Sheboom, reputedly Europe's largest all-women drumming ensemble. The echoes reverberated around the cavernous central space of the Kelvingrove, and people viewed the opening from ground level and the balconies above.

Illustration 24: OurSpace opening Kelvingrove [60]

OurSpace was formally opened by Hilary Third of the Equality Unit of the Scottish Government. During the opening day, visitors had the opportunity to view the LGBT Reminiscence Box (Handling Kit) that the Open Museum has developed with OurStory Scotland, and to tell further stories on video, inspired by the speak out performances seen in the exhibition. In numerous narrative acts throughout the country, speaking out has not only contributed live and recorded stories but also served as a means of developing performative skills and boosting the confidence of potential storytellers for larger-scale public performance. Storytelling performance is probably the single most effective way to engage the interest of a wider public, and embodies the interplay between speaking out and opening up. The most dramatic occasion for this was the OurStory Ceilidh. [61]

11. OurStory Ceilidh: Storytelling with Dance and Music

From the beginning of 2006 we had determined to stage a culminating storytelling event in the tradition of the ceilidh. This meant we were able to make contact with potential storytellers throughout the country and encourage them to come to Glasgow to perform one night in November as part of the annual Glasgay festival, Scotland's annual celebration of queer culture. [62]

The focal point of the ceilidh was the performance by 20 storytellers from all over Scotland, telling tales from Dumfries to Stornoway, to create a magical combination of music, dance and stories, in the best tradition of the ceilidh. In this way the culminating event drew on tradition, while reinventing and subverting it artistically, and making it genuinely accessible for a diverse community.

Illustration 25: Kilted dancers at OurStory Ceilidh [63]

In accordance with the awareness we had gained of the importance of a supportive atmosphere, we commissioned Charlie HACKETT to design displays for the venue, the Trades Hall in Glasgow. He took the Nessie Girls caricatures one stage further and used them to subvert what might have been an intimidating atmosphere of the hall—a grand and somewhat austere location—that we filled with people, images and stories. The visual storytelling materials we had produced throughout the year were organised into a show of alternative portraits, pictures and stories. The serious and sombre gentlemen in the Victorian oil paintings, surrounding and looking down on the dance floor, were joined by 8 huge portraits of the Nessie Girls, the Warhol-type multiple images of Steph, and a massive tapestry-type wallhanging in Gilbert and George style, drawing upon excerpts of the stories and portraits of participants.

Illustration 26: OurStory wallhanging [64]

The visual transformation of the hall made it into a supportive atmosphere for relating stories. The storytellers performed for a variety of audiences: for themselves, for a large audience including many from the LGBT community, in memory of absent others, and in explicit reference to a present partner, taking the rare opportunity of voicing a public declaration of love in front of friends and strangers.

Video 3: OurStory Ceilidh—storytelling performance by Kath

at the OurStory Ceilidh, Glasgow Trades Hall, November 2006 [65]

In addition to the stories on stage, there was a wide range of other stories in evidence and opportunities for telling tales. Story trees were set up for participants to tie storylines, the ultimate minimal story written in one-liners on multi-coloured labels.

Illustration 27: Story tree [66]

All around the hall were displayed 150 written episodes collected throughout Scotland during the year and printed on paper of the colours of the rainbow. The rainbow theme was taken up in a specially commissioned exhibition of Rainbow Thistle watercolours by Ruth WATERHOUSE, that was later reworked in glass.

Illustration 28: Rainbow Thistle [67]

Scotland's national flower is thus portrayed in rainbow colours that symbolise LGBT diversity. At the ceilidh, the fabled origins of the thistle as a defender of the nation were re-mythologised in an LGBT version, spoken out as the Legend of the Rainbow Thistle, and offered to participants as a myth they could write for themselves. Diversity was a defining feature of the event and, through the variety of visual and verbal narrative acts, a traditional and potentially restrictive venue was reclaimed for truly diverse participation: people who do and do not identify as LGBT, with multi-ethnic and multi-national backgrounds, including tourists from abroad who professed an interest in "traditional" culture. [68]

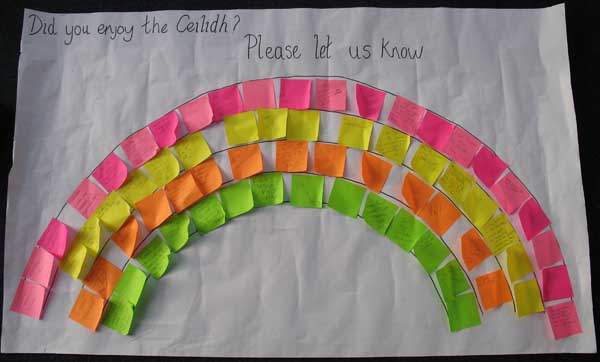

Evaluation of large-scale events such as the OurStory Ceilidh is notoriously difficult to organise, but our archivist Sarah COWIE came up with the innovative idea of an evaluation rainbow. As everyone left at the end of the ceilidh, they were invited to write a brief comment on coloured paper and stick it on the rainbow, which provided valuable concluding feedback and encouragement.

Illustration 29: Evaluation rainbow [69]

A fine way to conclude would be a positive evaluation of a culminating event. Yet this would be to distort the chronology of a continuing project. As ever, developments come after. Indeed some of the storytelling described above (reminiscence with the Open Museum, performance with masks, delineation through comic strips and display through further exhibitions) are offshoots that come after the OurStory Ceilidh. Culminations have a way of spawning further initiatives. While the project has no conclusion, conclusions of a practical nature can be offered.

An effective way of exploring the neglected narratives of a marginalised community is to combine action research with performative social science, generating and publicising a heritage of life stories through performance.

The participatory and emancipatory qualities of such research are more likely to appeal to funders of community research and access to the arts, rather than conventional social science funding bodies.

A wide and ever-expanding range of storytelling methods is available for research with marginalised communities, where disclosure has been problematic: the methods reviewed and illustrated here have proved effective with the LGBT community, and could be adopted and adapted for use with other communities.

Whichever methods are used, all storytelling has a performative aspect and no narrative act is context free: instead of searching for a spurious objectivity, a range of modes of narrative performance should be considered, that will offer diverse and potentially complementary insights.

Telling a wide range of stories from within a community, using a variety of narrative methods, reveals multiplicity, flexibility and ambiguity of identification, that challenges rigid categories and stereotypes imposed from outside, and reveals the centrality of storytelling to leading our lives. [70]

The final performance at the OurStory Ceilidh exemplified the defiance of neat classification. Nick told us his story first as a written episode in the OurStory Tent in Aberdeen:

"I once wrote a poem about myself. The last lines of the poem were ...

I've been hetero and LGBT

I'm not that I'm all that

I'm perfectly able to identify

Simply as me.

It kind of sums me up. My journey has been a fluid discovery of myself, claiming and rejecting identities, trying to find the one that fits best. Through that process I have come to realise that I have been, and therefore am, all of the labels, but mostly I'm just me.

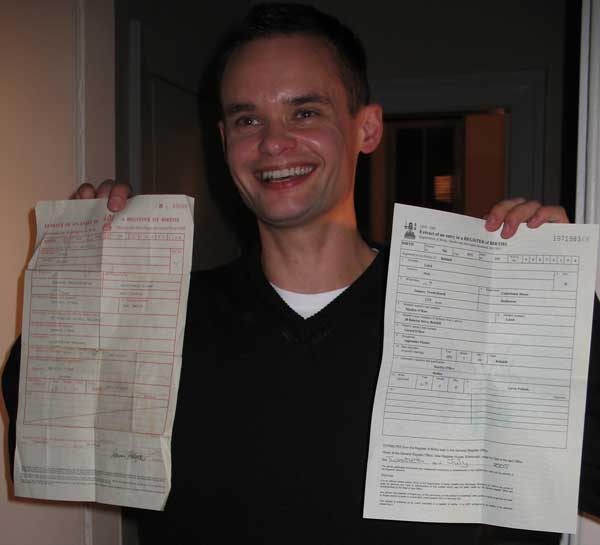

In my teens I said I was bisexual. At the age of sixteen I came out as lesbian. I had a seven year relationship with a wonderful woman but that was not the whole story, that was not the whole me. At the age of 25, I started the process of taking hormones and living and expressing my masculinity. I even have ‘male' on my birth certificate these days, but I also kept my old birth certificate. One day I'll frame them together in a picture frame and laugh at it knowing none of those birth certificates is adequate.

I'm transgender, a trans-man and I'm proud to acknowledge that. I now live with my gay male partner. People couldn't understand that at first and not just straight people. A lot of lesbian and gay folk had difficultly understanding why a gay man and a trans-man would get together, but the truth is, both my partner and I looked beyond the labels and saw each other for real. It's such a free place to be. I don't care how other people view me. I know what I like, what makes me comfortable, happy and free, and I'm not bothered what you want to call it." Nick [71]

Nick's written account was followed up by an extended oral history interview in Perthshire, and by a storytelling performance at the ceilidh in Glasgow.

Video 4: OurStory Ceilidh—storytelling performance by Nick

at the OurStory Ceilidh, Glasgow Trades Hall, November 2006 [72]

On display at the ceilidh was the picture Nick had wanted taken, holding up his female and male birth certificates and laughing between them.

Illustration 30: Nick birth certificates [73]

Nick's story has no neatly defined conclusion. It challenges identifications, declines the preordained trajectory of medical completion, and revels in the ambiguity of being all and nothing. It is emblematic of our research, that has no clear-cut ending. The story of the storytelling, like the narrative acts that make it up, should be seen as performative, provisional and to be continued. [74]

The project has been supported by Scottish Arts Council lottery funding and the Scottish Community Action Research Fund. The stories, oral histories and artworks created through the project are being archived at National Museums Scotland for a national archive of LGBT lives—the OurStory Scotland Collection, part of the Scottish Life Archive.

1) Unless otherwise stated, quotations are from life stories told to OurStory Scotland 2004-2007. <back>

2) GOYTISOLO (1990, p.261) observes that the search for a pure unstructured truth will result only in silence: "The unbridgeable distance between act and written word, the laws and requirements of the narrative text will insidiously transmute faithfulness to reality into artistic exercise, attempted sincerity into virtuosity, moral rigor into aesthetics. No possibility of escape from the dilemma; the reconstruction of the past will always be certain betrayal as far as it is endowed with later coherence, stiffened with clever continuity of plot. Put your pen down, break off the narrative, prudently limit the damage: silence, silence alone will keep intact a pure sterile illusion of truth." <back>

3) The OurStory Scotland Collection forms part of the Scottish Life Archive at National Museums Scotland. <back>

4) This is the whole raison d'être of the Scottish Communities Action Research Fund. <back>

5) The Scottish Arts Council selected our project as an example of best practice of informal learning through the arts (OURSTORY SCOTLAND, 2007). <back>

6) As in the eponymous novel by Virginia WOOLF (1941), the most interesting performances may take place "between the acts". <back>

7) The terms used are those preferred by the gay women and transgender women involved. <back>

8) ROUND…AB…OUT opened on 18 January 2008 and ran for a month. It was curated by Mark DUGUID and Charlie HACKETT. <back>

9) OurSpace opened on 2 February 2008 and ran for a month. It was curated by Dianne BARRY. <back>

Celyn Jones, Russell (2001). Surface tension. London: Abacus.

Goytisolo, Jean (1989). Forbidden territory. London: Quartet.

Goytisolo, Jean (1990). Realms of strife. London: Quartet.

OurStory Scotland (2007). Queer stories. In Scottish Arts Council (Ed.), Firing the imagination 2: Arts and community learning and development. Edinburgh: Scottish Arts Council, also available at: http://www.scottisharts.org.uk/1/information/publications/1005040.aspx.

OurStory Scotland (2008). Making space for untold stories. In Scottish Arts Council (Ed.), Information bulletin. Edinburgh: Scottish Arts Council, also available at: http://www.scottisharts.org.uk/1/information/publications/1005197.aspx.

Strauss, Anselm (1997). Mirrors and masks: The search for identity. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction.

Todhunter, Colin (2001). Undertaking action research: Negotiating the road ahead. Social Research Update, 34, 1-4.

Valentine, James (1998). Naming the other: Power, politeness and the inflation of euphemisms. Sociological Research Online, 3(4), Art. 7, http://www.socresonline.org.uk/socresonline/3/4/7.html [Date of Access: November 1, 2007].

Valentine, James (2002). Naming and narrating disability in Japan. In Mairian Corker & Tom Shakespeare (Eds.), Disability/postmodernity: Embodying disability theory (pp.213-227). London: Continuum.

Woolf, Virginia (1941). Between the acts. London: Hogarth.

Videos

Video_1: http://www.youtube.com/v/hfxLfo9GgfI?hl=en&fs=1 (425 x 344)

Video_2: http://www.youtube.com/v/oZGECn7S-M4?hl=en&fs=1 (425 x 344)

Video_3: http://www.youtube.com/v/AqiTlCOeLNE?hl=en&fs=1 (425 x 344)

Video_4: http://www.youtube.com/v/0DUDrk3mwr8?hl=en&fs=1 (425 x 344)

James VALENTINE is Chair of OurStory Scotland, based at the Mitchell Library in Glasgow, and Honorary Senior Research Fellow at the Department of Applied Social Science, University of Stirling.

Contact:

James Valentine

Dept of Applied Social Science

University of Stirling

Stirling FK9 4BQ

Scotland

E-mail: info@ourstoryscotland.org.uk

URL: http://www.ourstoryscotland.org.uk/

Valentine, James (2008). Narrative Acts: Telling Tales of Life and Love with the Wrong Gender [74 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 9(2), Art. 49, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs0802491.

Revised: 4/2011