Volume 26, No. 2, Art. 5 – May 2025

Is a Picture Worth a Thousand Words? Member Checking Using the Sketchnoting Approach

Marie-Ann Kückmann

Abstract: The question of validity is particularly important in the context of qualitative research. There have been numerous attempts to establish or reformulate criteria for validity and procedures for increasing validity. Member checking is one example. Although member checks are frequently integrated into qualitative studies, researchers do not always describe and explain them in detail in the corresponding reports.

In this paper, I would like to contribute to the research on conducting member checks by presenting and discussing the approach of sketchnoting. I argue that there is potential (both in theory and practice) in using this means of communication: Relevant problems that might occur in the context of member checking are addressed, and the gap between transactional and transformational validity approaches is bridged. From the perspective of a process-oriented view of validity, a reflective process for participants and researchers is supported.

Key words: quality criteria; process-oriented view of validity; validation; member checking; sketchnoting; visual thinking; multimodality

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. The Question of Validity

3. The Potential of Using Sketchnoting for Validation

3.1 Principles of sketchnoting

3.2 Discussion

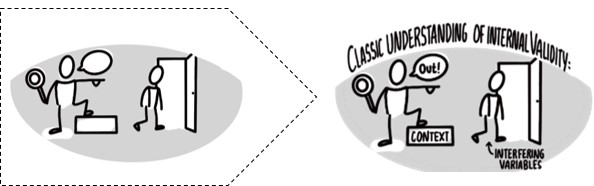

4. Examples of Using Sketchnoting for Validation

4.1 Context of the study and methodology

4.2 Discussion

5. Concluding Remarks

"In the past, qualitative researchers have fought hard for acceptance and recognition of their work; this battle has largely been won. Today, in most social science disciplines [...] qualitative epistemologies, theories, and methods are used and taught as 'mainstream' science alongside their quantitative counterparts" (Excerpt from the editors' introduction to the FQS debate on the Quality of Qualitative Research).

Qualitative social research is an umbrella term rather than a consistent approach (CHO & TRENT, 2006; FLICK, 2018 [2007]; STRÜBING, HIRSCHAUER, AYAß, KRÄHNKE & SCHEFFER, 2018). FLICK (2018 [2007]), MRUCK and MEY (2000) and REICHERTZ (2017), for example, offered a comprehensive overview of the range and development of qualitative social research. The distinction between qualitative and quantitative social research has played a significant role in the corresponding development (STIGE, MALTERUD & MIDTGARDEN, 2009). [1]

Qualitative social researchers focus upon the subjective and/or social attribution of meaning (REICHERTZ, 2017; STRÜBING et al., 2018). In other words, they "seek to unpick how people construct the world [...], what they are doing or what is happening to them in terms that are meaningful and that offer rich insight" (FLICK, 2018 [2007], p.x). Making meaning is a starting point (MRUCK & MEY, 2000, §12). Initially, the focus was on the subject and empowerment, and attention then turned to the collective discourse (REICHERTZ, 2017). Today, the focus is often on practices and artefacts and, within this, REICHERTZ perceived a new self-understanding. Accordingly, qualitative research is a communication process which requires reflecting on one's own research practice (ibid.). Quality issues have been the subject of ongoing fundamental debate (see, for example, the contributions to the FQS debate on the "Quality of Qualitative Research"). [2]

The discussion ranges from epistemological questions about the (im)possibility of cognition, associated levels of internal as well as external legitimacy, and theoretical criteria and standards (FLICK, 2018 [2007]). BREUER and REICHERTZ (2001, §9) pointed out at an early stage of the discussion that qualitative social research cannot be considered in isolation, and FLICK (2018 [2007]) identified at least three relevant contexts:

"it comes up for researchers who want to assess and ascertain their results; it becomes relevant for users of research—readers of publications, commissioners of funded research—who want to (and often have to) assess and evaluate what is presented to them as results after the funding has ended; and in the evaluation and reviewing of qualitative research, in reviewing research proposals and increasingly in reviewing manuscripts in the peer review process of journals" (p.70). [3]

FLICK distinguished between internal needs and external challenges and placed the corresponding discussions "at the crossroads" (p.3; see also CRESWELL & MILLER, 2000; LAUCKEN, 2002). Underlying internal needs and external challenges must be set off against each other:

"Here we encounter dilemmas between the need for sensitiveness for the particular strengths and features of qualitative research and the needs and interests of actors outside the community in the pure sense—which means commissioners, readers, consumers, and publishers of qualitative research" (FLICK, 2018 [2007], p.5). [4]

The relevance of such discussions is undisputed (CRESWELL & MILLER, 2000; FLICK, 2018 [2007]; HAMMERSLEY & ATKINSON, 1995 [1983]; KIENER & SCHANNE, 2001; LATHER, 1995; LINCOLN & GUBA, 1985; STILES, 1993; STRÜBING et al., 2018; WHITTEMORE, CHASE & MANDLE, 2001). Quality criteria have played a significant role in the discussion (CRESWELL & MILLER, 2000; STRÜBING et al., 2018; WHITTEMORE et al., 2001) and the distinction from quantitative social research is again relevant (FLICK, 2020; LAMNEK, 2010 [1988]; REICHERTZ, 2000; WHITTEMORE et al., 2001). There is broad consensus in quantitative social research as to how to determine whether research is of "high" quality or not. "The main criteria are objectivity, reliability and validity from experimental-statistical and hypothesis-testing research and from psychometrics [...]. Behind these is the widely used concept of 'unity-criteria' according to which all research has to be evaluated" (STEINKE, 2004, p.184). These criteria are undisputed since their primary focus lies on the quality of a measurement process and thus on the standardisation of the research situation. The focus is on a comparatively small part of the research process (FLICK, 2018 [2007]; STRÜBING et al., 2018). [5]

However, since the research process in qualitative research is not standardised to the same extent, the extent to which this can be transferred to the context of qualitative social research remains unclear (CARLSON, 2010; MISOCH, 2019 [2015]). Discussions often conclude that direct transmission is not possible because these data come from a different understanding of reality, logic of action and cognition (FLICK, 2020; MISOCH, 2019 [2015]). Various authors distinguished between two alternatives within the discussion: Thus, one can either, 1. modify or reformulate the traditional criteria (CRESWELL & MILLER, 2000; FLICK, 2020, 2018 [2007]; MISOCH, 2019 [2015]; STEINKE, 1999, 2003, 2004; WHITTEMORE et al., 2001) or, 2. develop methodologically appropriate, alternative criteria (STRÜBING et al., 2018; TRACY, 2010). For a current critical analysis of the first approach, see SCHNEIJDERBERG (2023). The third option is that researchers could turn away completely from the idea of measurement in relation to the criteria. LAUCKEN (2002, §10) argued that quality criteria could otherwise become scientific control instruments. [6]

There have been numerous attempts to produce or reformulate criteria for validity in qualitative research (WHITTEMORE et al., 2001). Consequently, there are also various procedures for enhancing validity (CARLSON, 2010). Member checking is one example. Through using member checking, a consensus between researchers and participants can be achieved. In other words, validity is achieved "when readers think 'yes, of course' in response to interpretations and claims about data and in relation to the research question driving the study" (LANKSHEAR & KNOBEL, 2004, p.364). Although member checks are frequently integrated into studies, researchers do not always explain them in detail (BREAR, 2019; BUCHBINDER, 2011; DOYLE, 2007). In addition, textual data are often validated using textual data in the context of member checking, e.g. through validation interviews (BUCHBINDER, 2011). Critical analysis requires establishing whether and to what extent it would be appropriate to use means of expression other than text to achieve a deep understanding. [7]

I argue that images, because of their specific characteristics, offer significant potential for enhancing interaction and supporting understanding between researchers and participants. As the proverbial saying a picture is worth a thousand words indicates, one can convey multiple meanings using one single image (LOBINGER, 2012). Unlike texts, which are more subject to convention and might thus be biased, images are more abstract and therefore invite a range of interpretations (KÜCKMANN, 2023a, 2023b). In general, in qualitative social research,

"visual data [currently] are in great demand. Given the technological possibilities such as recording and reproduction, visual data have become increasingly popular in social science research. [...] Today, non-textual data are frequently included in various research designs. As a result, an 'all is data' mentality has become the implicit assumption for many qualitative research projects" (MEY & DIETRICH, 2016, §1). [8]

However, representatives of the debate concerning the so-called pictorial or iconic turn (e.g. BOHNSACK, 2003, p.239; JÖRISSEN, 2014, p.124) by no means intended to play off images against textual data, but to acknowledge the best of both approaches to achieve complementary understanding (KÜCKMANN, 2023a, 2023b). Means of communication to combine both approaches such as sketchnoting are therefore required: Sketchnoting is a technique, widely used in business and education (GANSEMER-TOPF, PAEPCKE-HJELTNESS, RUSSELL & SCHILTZ, 2021), where limited numbers of lines of text are combined with simple graphic elements (KÜCKMANN, 2023a). It is a creative visual note-taking process through which individuals record, structure and stimulate their thinking as well as that of others (KÜCKMANN, 2023b). "Sketchnotes don't require special drawing skills but do require you to listen and visually synthesize and summarize ideas by using writing and drawing" (ROHDE, 2020, n.p.). To give an impression of the form of communication, I refer at this point to a poster1) on the topic which was designed using the sketchnoting approach (KÜCKMANN, 2023a). Its relevance in human communication is illustrated by numerous examples and increasingly also in the context of research. New perspectives are offered by sketchnoting regarding validation, for example (KÜCKMANN, 2023b; KÜCKMANN & KUNDISCH, 2021). In this paper, I draw on experience using this approach in an empirical qualitative study. I created sketchnote protocols during the interview situation as an approach to member checking and provided a first draft at the end of the interview (DANIEL-SÖLTENFUß, KREMER & KÜCKMANN, 2022, 2024). The validation procedure was thus part of the initial data collection, offering new perspectives on validity. [9]

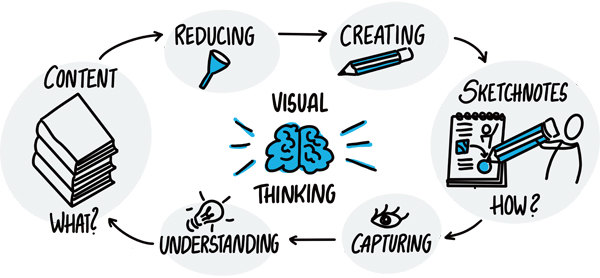

According to REICHERTZ (2019), critical questions concerning the debate on qualitative social research lead back to "the debate that has arisen from 1. the massive changes that qualitative and interpretive social research have undergone in recent years and 2. the associated, clear increase in new methodological approaches" (Abstract). REICHERTZ described qualitative methods as an art and emphasised the need to work in-depth with the methodological foundation. The emphasis is not on using a validation method for the sake of novelty, but on doing it differently for "good" reasons and using it as an opportunity for reflection (§24-30; see also REICHERTZ, 2017). [10]

In this paper, I critically analyse validity approaches in qualitative research and corresponding procedures such as member checking (Section 2). Secondly, I outline the potential of sketchnoting (Section 3) and provide insights into its practical use (Section 4). Thirdly, I discuss the procedure using a holistic approach to validity (Section 5). [11]

In qualitative research, questions of validity are pivotal (CHO & TRENT, 2006; WHITTEMORE et al., 2001; ZHAO, LI, ROSS & DENNIS, 2016). In quantitative research there is a connection between the evaluation of research and the standardisation of research situations (FLICK, 2018 [2007]). Possible interfering variables are excluded when using internal validity, and control of contextual conditions is achieved (see Figure 1). In this context, FLICK (2018 [2007]) identified the following problem: "The necessary degree of standardization is not compatible with qualitative methods or questions their actual strengths" (p.27). A reformulation of the criteria must start at an earlier stage. This emphasises the researcher's typologies and terminologies. ZHAO et al. (2016) characterised validity in this context "as it is so closely related to the fundamental understanding of knowledge and truth, [...] [as] one of the most contentious terms open for debate, deconstruction, and reconstruction" (§11). [12]

There have been attempts to do justice to the uniqueness of validity in qualitative research (BUCHBINDER, 2011; CRESWELL & MILLER, 2000; WHITTEMORE et al., 2001). According to BUCHBINDER (2011), LINCOLN and GUBA's (1985) model is the most coherent. Following this recommendation, qualitative researchers evaluate their research based on its trustworthiness. This term includes the criteria of credibility (in place of internal validity), transferability (in place of external validity), dependability (in place of reliability) and confirmability (in place of objectivity) (BUCHBINDER, 2011; REILLY, 2013). WHITTEMORE et al. (2001) provided an overview of additional validity concepts. However, REILLY (2013) emphasised trustworthiness as "the original gold standard" (p.1). Generally, it is closely linked to the extent to which the researcher's claims about knowledge correspond to reality (or the participants' constructions of reality) (CHO & TRENT, 2006; WELSH, 2002). The methods literature contains references to techniques which include, for example, member checking, triangulation, thick and rich description, peer reviews and external audits (CARLSON, 2010; CRESWELL & MILLER, 2000; SIMPSON & QUIGLEY, 2016). Yet, CRESWELL and MILLER (2000) argued that the validity claim does not refer to the data, but to the conclusions drawn from them by the researcher (see also HAMMERSLEY & ATKINSON, 1983 [1983]). Including validation procedures could, in these ways, ensure a degree of accuracy and consensus. [13]

These techniques are widely used but are less often described in detail (BREAR, 2019; BUCHBINDER, 2011; DOYLE, 2007). CRESWELL and MILLER (2000) assumed that difficulties might arise in the selection process (see also KOELSCH, 2013). CRESWELL and MILLER (2000) provided a two-dimensional framework, in which they support the classification of various procedures based on different paradigmatic assumptions and differentiate between postpositivist, constructivist and critical paradigmatic assumptions. They argued that the research perspective also differs due to the perspectives of the researchers, the participants as well as the reviewers. [14]

Member checking, also known as member validation (BLOOR, 1997; SEALE, 1999), is characterised as "the most crucial technique for establishing credibility" (LINCOLN & GUBA, 1985, p.314). As the term implies, the aim is to give participants the opportunity to review and approve the researcher's analysis and interpretation (CARLSON, 2010).

"Member checking is the process in which the researcher asks one or more participants in the study to check the accuracy of the account. This check involves taking the findings back to the participants and asking them (in writing or in an interview) about the accuracy of the report. You ask participants about many aspects of the study such as whether the description is complete and realistic, if the themes are accurate to include, and if the interpretations are fair and representative" (CRESWELL, 2005 [2002], p.252). [15]

CRESWELL and MILLER (2000) argued that choosing member checks as a validation technique illustrated a researcher's commitment to rigorous methods. I agree with CHO and TRENT (2006, p.320), who described this analysis as problematic "because it is based primarily upon a narrowly defined nature of choice connected to overlapping modes of inquiry". The authors referred to SEALE's (1999) approach and offered a holistic view of validity (and validation procedures), in which they distinguished between two approaches:

"We define transactional validity in qualitative research as an interactive process between the researcher, the researched, and the collected data that is aimed at achieving a relatively higher level of accuracy and consensus by means of revisiting facts, feelings, experiences, and values or beliefs collected and interpreted. [...] On the other hand, we define transformational validity in qualitative research as a progressive, emancipatory process leading toward social change that is to be achieved by the research endeavor itself" (CHO & TRENT, 2006, pp.321-322). [16]

Member checking can be understood in two different ways. First, "as a technique or method in making the research valid for those pursuing the 'truth' seeking purpose. In this regard, member checking is conceived of as a means to an end" (p.336). Through integrating member checking, researchers can therefore contribute to reducing misunderstandings. As such, access is facilitated to information which "already exists inside a participant's consciousness" (KOELSCH, 2013, p.170). Accordingly, "validity of the text/account is of primary importance" (CHO & TRENT, 2006, p.322). In my view, the question arises as to whether textual artefacts are the optimal instrument. [17]

In the second approach, meanings are understood as social constructions, and different perspectives on a topic lead to different meanings (CHO & TRENT, 2006). However, if this assumption is taken seriously,

"the question of validity in itself is convergent with the way the researcher self-reflects, both explicitly and implicitly, upon the multiple dimensions in which the inquiry is conducted. In this respect, validity is not so much something that can be achieved solely by way of certain techniques. [...] it is the ameliorative aspects of the research that achieve (or do not achieve) its validity. Validity is determined by the resultant actions prompted by the research endeavor" (p.324). [18]

Thus, if they include member checking, researchers support creating and/or changing "truth" (KOELSCH, 2013, p.170). It is a transformative process, which establishes "more equitable relationships between researchers and participants" (BREAR, 2019, p.945). Such interaction requires a high degree of self-reflexivity on the part of the researcher. CANDELA (2019) emphasised the importance of the interaction between researchers and participants and the participants' experience. [19]

These two approaches have advantages, but neither of them is sufficient. CHO and TRENT (2006) developed a recursive, process-oriented view of validity. Validity is seen as "a fluid process that eschews dichotomies such as practical/emancipatory and transactional/transformational" (KOELSCH, 2013, p.169). CHO and TRENT (2006) argued that the integration of specific procedures does not guarantee the validity of a study, but they are nonetheless in favour of integrating them. Therefore, using member checks contributes to, but does not ensure, validity. In the proposed framework, they differentiated "among types of member checks, i.e. 'technical (focus on accuracy, truth),' 'ongoing (sustained over time, multiple researcher/informant contacts),' and 'reflexive (collaborative, open-ended, reflective, critical),' all of which are meaningfully compatible with particular research purposes, questions, and processes" (pp.335-336). Critical reflection on member practices could follow these patterns. [20]

Descriptions of using member checks are still rather limited (BREAR, 2019; DOYLE, 2007). However, DOYLE (2007) pointed out that there are different member checking processes, i.e. "It can be either continuous, or it can occur as one event, and can be formal or informal within the context of a qualitative research study" (p.893). Additionally, it can take place with one individual participant or in a group (ibid.). Validation interviews are particularly important in this context (BUCHBINDER, 2011; CHO & TRENT, 2006; DOYLE, 2007; KOELSCH, 2013). According to BUCHBINDER (2011), the term refers to a dialogue between participants and researchers "intended to confirm, substantiate, verify or correct researchers' findings" (p.107). [21]

There are various problems in connection with validation interviews (BREAR, 2019; CARLSON, 2010). BUCHBINDER (2011) drew on an interview he conducted with researchers on this topic. He pointed out the power dynamic issues, for example.

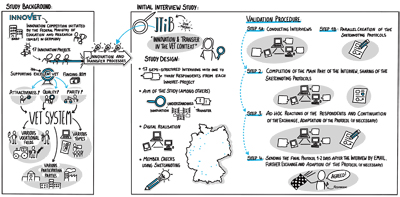

"Power is generally perceived to be clearly and dichotomously divided between the initial interview, where it lies with the interviewee, and the validation interview, where it is transferred to the interviewer. This creates conflicts around the use and abuse of power [...]" (p.115). [22]

A therapeutic dimension is a possible barrier (ibid.), as well as social desirability (REILLY, 2013). REILLY argued that participants might have difficulties working with abstract interpretations or they might not remember what they said. Additional time might be required for further interviews, which could lead to participants' resistance to the research process (ibid.; see also BLOOR, 1997). In addition, in trying to reach a consensus, researchers might have to deal with disagreements about the interpretation (REILLY, 2013). As CARLSON (2010) concluded: "Miscommunication between participants and researchers can especially arise from the unique and unpredictable nature of human dynamics" (p.1102). [23]

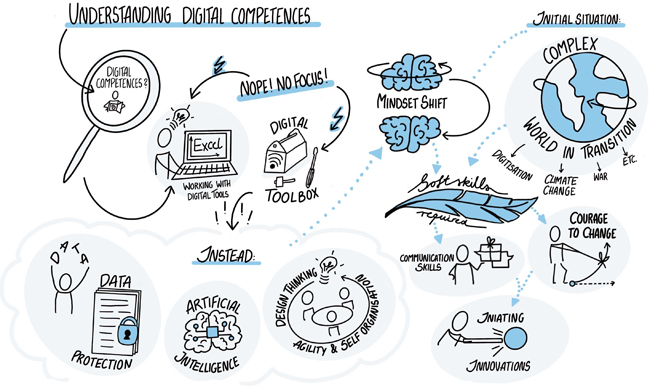

Problems can also be caused by the presentation of the data and initial findings. For example, irritations can be caused by the transcriptions (CARLSON, 2010; FORBAT & HENDERSON, 2005; KOELSCH, 2013). For this reason, DOYLE (2007) played the audio recording to the participants. The overarching aim is not to intimidate the participants, but to encourage them (CHASE, 2017). REILLY (2013) favoured "arts-based" techniques "to substantiate dimensions of the research inquiry and more closely and actively involve participants, creating personal connections [...]" (p.15). She also described the use of poems written by participants (ibid.). SIMPSON and QUIGLEY (2016, p.380) included alternative, art-based techniques such as "I‑poems" and word trees. "Through participatory research, resiliency and competency can be attributed to all participants because they have not had research conducted on them, but instead with them, creating a joint process of knowledge production" (CHASE, 2017, p.2701). [24]

In many approaches, the focus is on textual language or textual logic. Textual data generated by interviews are often validated using primarily textual data. For instance, CARLSON (2010) did not reflect upon the way in which communication occurs. I argue that language issues play a significant role, following HUBER (2001, §31), who pointed out that form, thought and action are inseparable and occur within language. Furthermore, the creation of meaning is essentially a social product. According to HUBER, knowledge cannot be separated from language, which both enables and limits cognition (ibid.). In the context of the transactional aim of gaining access to the participants' inner perspective, one might consider using different or additional forms of expression. [25]

Difficulties also arise from a transformational position (KOELSCH, 2013). Referring to HUBER (2001, §31), one could ask to what extent textual language is suitable for opening up new perspectives on the part of both researchers and participants. Following this view "qualitative researchers are encouraged to examine meanings that are taken for granted and to create 'analytic practices' in which meanings are both deconstructed and reconstructed in a way that makes initial connotations more fruitful" (CHO & TRENT, 2006, p.324). A further question is why the individual parts are separated at all. If the participant's view is understood as a process (KOELSCH, 2013), I would ask whether it is advisable to integrate member checking endeavours during data collection. CHUA and ADAMS (2014), for example, suggested real-time transcription for member checks. However, critical questions about the primacy of the textual representation remain. [26]

Is the focus on communication and promoting reflection processes or do the results take centre stage? This can be determined based on the function of the validation products. Is validity solely linked to the validation products or are the validation products themselves intended to stimulate further reflection? In other words: Are the validation products the objective or a means to an end? I view member checking as a reflexive process for both the researchers and the participants, along with KOELSCH (2013), who concluded:

"This does not mean that member checks are of little use for postmodern research; rather, I propose that the member check is an ideal way to span the transactional/transformational divide. Nevertheless, the member check needs to be reinterpreted in order to adequately address postmodern insights regarding the research process. In other words, the member check can be a reflexive process for both the researcher and the participants" (p.171). [27]

However, she did not address language issues. In the following sections, I present a member checking example (both in theory and practice) in which, firstly, the critical questions are addressed and, secondly, the gap between transactional and transformational validity approaches is bridged. My aim is to contribute to the research on how to conduct member checks by discussing my approach using sketchnoting. This illustrates why and how this specific member check practice can contribute to a reflexive process for participants and researchers. [28]

3. The Potential of Using Sketchnoting for Validation

3.1 Principles of sketchnoting

The term "sketchnoting" can also be termed "visual note-taking" (KÜCKMANN, 2023b, p.625; see also ROHDE, 2020) and its use has become increasingly varied (KÜCKMANN, 2023b). Additional purposes have emerged beyond the original conceptual visual note-taking function in which visualisations and simple textual elements are used in a similar way (graphic recording, visual facilitation etc.). The concept of sketchnoting is not limited to its visual note-taking function but is based on a holistic understanding of the term (ibid.). Certain communication principles are featured in this context, for example, pictorial and textual components, in a symbiotic relationship. At first glance, sketchnoting is determined by the inherent communicative and cognitive potential of pictures and images. For this reason, it is advisable to consider the concept of images (ibid.), as well as the distinction between general and specific images (LOBINGER, 2012). [29]

BOEHM (1994) and MITCHELL (1986) presented a conceptual understanding of general image studies (see also JÖRISSEN, 2014). While MITCHELL's (1986) approach was within the context of cultural studies and accordingly classifies pictures as objects of cultural practice, BOEHM (1994) focused on the reflexive and intrinsic value of images. In English, a distinction is made between the terms picture and image. In German, however, there is only one word, Bild. MITCHELL (1986) distinguished between graphic, optical, perceptual, mental as well as linguistic picture types (see also LOBINGER, 2012). DOELKER (2002 [1997]) emphasised general transferability or communicability as relevant characteristics of pictures (see also KÜCKMANN, 2023b; LOBINGER, 2012). [30]

In the development of meaning, SCHWABL (2020, p.108) described three essential characteristics of pictures: 1. "specific referencing", 2. "iconicity" and 3. "simultaneity".2) The latter two are particularly relevant to the context of sketchnoting. The first characteristic refers to photographs and alludes to the referencing function of pictures, whereas verbal communication is characterised by abstractions based on its indexicality (see also KÜCKMANN, 2023b). In sketchnoting, however, it is precisely the abstractions that are valuable (ibid.). A semiotic approach, in which a sign is understood to stand for something to someone, is relevant in this context. The pictorial elements in sketchnoting have a clear sign-like character. The recipients are doubtless aware that the sketchnotes refer to another meaning and that they are not a perfect reflection of reality (ibid.). This differs, for example, from the reception of visual media in the form of photographs. In sketchnotes, abstraction and specificity are in a dialectical relationship that could be described as "specific indeterminacy" (p.643). [31]

PEIRCE (1983 [1903]) distinguished between 1. an index, which is closely related to its reference (e.g. footprints or smoke), 2. a symbol, which offers a conventional meaning (e.g. traffic signs and even words) and 3. an icon, which is characterised by its physical resemblance (e.g. a smiley or photograph). In sketchnoting, the latter two are particularly relevant. The degree of similarity is indicated by iconicity and forms the second characteristic of images. (Mono-)semantic sign relations and (poly-)pragmatic sign meanings can be distinguished from each other (LOBINGER, 2012). Meaning can be generated by the use of sketchnotes (KÜCKMANN, 2023b). The figures in sketchnoting are gender and age neutral and feature an openness in order to generate the meanings of recipients within a specific context (ibid.). [32]

Simultaneity is a holistic view in which the individual elements refer to each other. Whilst texts are perceived sequentially, images can initially be perceived as a whole (SCHWABL, 2020). The same applies to sketchnoting, in which results can first be perceived as a whole without being bound to specific syntax or grammar, and then perceived step by step in an individual process (KÜCKMANN, 2023b). The perception of images does not necessarily follow a pre‑ordained course. In contrast, texts are arguably read and understood in a specific sequence. From the perspective of visual communication research, images are described "as quick shots into the brain" (LOBINGER, 2012, p.76). Increased attention, comprehensibility, memorability as well as recipients' cognitive processing can be supported by using images with a direct effect on attitudes. These advantages are often summarised as the so-called "picture-superiority-effect" (p.48). [33]

There is an extensive academic discourse on the use of visual research methods (BECKER, 2002; HARPER, 1988, 2002, 2005 [1994]; PINK, 2012, 2021 [2001]; ROSE, 2014). However, explaining this in detail, and discussing the sketchnoting technique in the context of this larger methodological literature, is beyond the scope of this article. In this paper, my explicit focus is on the principles and practice of sketchnoting. [34]

Multimodality is the most significant feature of sketchnoting (KÜCKMANN, 2023b). Multimodal messages must be distinguished from multicodal messages. The former are characterised by the fact that they address several sensory modalities, whilst the latter have several symbol systems (LOBINGER, 2012). Sketchnoting is largely determined by multicodal messages (KÜCKMANN, 2023b). However, LOBINGER (2012, p.71) pointed to an academic use of "multimodality", used to describe messages that combine several semiotic modes. In this paper, I use a broad understanding of the term. [35]

STÖCKL (2009), a linguist, emphasised that "communication is ultimately and always multimodal" (p.205). Multimodality can be emphasised as the natural mode of all communication. STÖCKL assumed that using "media and the concomitant semiotic modes employed in them we seem to be permanently 'transcribing' meaning from one medium/mode to another" (ibid.). However, "multimodal refers to communicative artefacts and processes which combine various sign system (modes) and whose production and reception calls upon communicators to semantically and formally interrelate all sign repertoires present" (STÖCKL, 2004, p.9). The differences between pictorial and textual sign modalities with regard to sketchnoting are illustrated by the following table.

Table 1: Differences between pictorial and textual sign modalities according to STÖCKL (2011, p.48). Click here to download the PDF file. [36]

As such, sketchnoting is characterised by a high degree of multimodality and is more than the sum of its parts (LOBINGER, 2012). Thus, although visual and textual modes can be distinguished from one another in terms of sign theory, they merge reciprocally, and symbiotically in the multimodal interplay. Meaning is constructed by textual and pictorial elements in a complementary way (ibid.). For instance, in Figure 1 below, pictorial signs are shown to be semantically dense and open to a range of meaning whereas the context and specific meaning are delivered by the text (KÜCKMANN, 2023b).

Figure 1: Selected visualisation from KÜCKMANN (2023a) with and without text elements [37]

The textual components locate the excerpt in the context of the debate on the "Quality of Qualitative Research" in terms of its underlying meaning. Thus, within the framework, the pictorial components could in turn be interpreted differently, depending on the individual recipients' social constructions (KÜCKMANN, 2023b). For example, there could be differences in relevant variables depending on their context. "Deeper" knowledge is constructed by synthesis (ibid.). In this sense, in my view, dynamic dialectical processes are created by using sketchnoting. [38]

The term dialectics alongside hermeneutics and phenomenology, is very widespread—especially in German-language social research, but it is far from a uniform approach. DANNER (2006 [1979]) characterised the term as the art of conducting an argument. MAYBEE (2020) stated: "'Dialectics' is a term used to describe a method of philosophical argument that involves some sort of contradictory process between opposing sides". Both authors referred to the conversational dialectic of SOCRATES and PLATO, and DANNER (2006 [1979]) emphasised the question whether the contradiction lies in human cognition or in the object itself. According to KANT (1966 [1791]), the dialectic assumes that the occurrence of contradictions is in human cognition and is closely linked to the human way of thinking (DANNER, 2006 [1979]). In HEGEL's (1952 [1807]) work, reality itself is characterised as dialectical, and he established a "system thinking" (DANNER, 2006 [1979], p.186). [39]

In a classic dialectical scheme, the following three elements can be distinguished: 1. thesis, 2. antithesis and 3. synthesis (pp.178-187). This dialectic scheme is taken up in many of the approaches mentioned above. There are three steps. The first step lies between thesis and antithesis, a second between antithesis and synthesis, and the third in the transition from a synthesis to a new thesis, whereby the dialectic process continues (DANNER, 2006 [1979].). Negation represents the driving force within the first step, which is bound to the initial thesis in terms of content. In the second step, the contradiction and opposition of thesis and synthesis strive for a "higher" resolution (p.181). Depending on the approach, the dynamics understood in this way drive both the focussed object and the thinking. Truth is understood in a dialectic understanding as not static but processual. [40]

This dialectical principle is reflected within the structural principles of sketchnoting (KÜCKMANN, 2023b). Deep reflections and high-level insights are achieved through contrasting characteristics of visual and textual language in the context of dynamic-dialectical processes on the part of producers and recipients of sketchnoting artefacts in a co-creative process (ibid.). [41]

Through using sketchnoting, reflection processes are supported and enhanced. It can support processes of mutual reflection for the researchers and participants when used in the context of member checking. From a theoretical point of view, the production perspective also has potential, as illustrated in Figure 2:

Figure 2: Production perspective of sketchnoting (p.639) [42]

A researcher's visual thinking can be stimulated by creating sketchnotes for member checking. In the context of developing visualisations, researchers have to engage actively with the content and reduce complexity. This focus on the essential elements creates a fourfold harmony between capturing, understanding, reducing and presenting content in the sketchnotes. Participants can modify the protocols during the member check and are therefore involved in the production. Thus, production and reception go hand in hand. In my view, there is an opportunity to improve exchange and understanding between those involved in the study. Researchers and participants may gain (new) insights during the discussion of the content. This represents the foundation for validation from a transformational viewpoint (CHO & TRENT, 2006). [43]

From a transactional perspective, it becomes possible to reveal and eliminate misunderstandings (ibid.). Different ways of being and seeing are arguably more likely to be accepted and expressed based on images than text alone (KÜCKMANN, 2023b). Differences in attributions of meaning can be revealed and the danger that interviewers and participants are at odds with one other can be reduced. Researchers can use the sketchnoting protocols as a bridging instrument. Transactional validity is not supported based on the validity of the validation product, but rather communication is supported by the validation product (JÖRISSEN, 2011). At this point, my approach differs from CHO and TRENT's (2006). Through using sketchnoting as a validation instrument, based on its multimodal principles, the validity of generalisation is, to a certain extent, turned on its head (REICHERTZ, 2000), since abstraction is enhanced by the generalisation. Sketchnoting is arguably a useful tool for bridging the gap between transactional and transformational validity approaches. I used this form of communication in a study, as described in Section 4. [44]

4. Examples of Using Sketchnoting for Validation

4.1 Context of the study and methodology

The project Innovations- und Transferprozesse in der Berufsbildung (ITiB) [Innovation and Transfer in the Vocational Education and Training (VET) Context] is part of the programme Zukunft gestalten – Innovationen für eine exzellente berufliche Bildung [Shaping the Future—Innovations for Excellent VET] (InnoVET) in Germany. InnoVET is funded by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research and features seventeen projects developing innovations to enhance the attractiveness and quality of the VET system (BMBF, 2019, 2021). InnoVET includes a range of vocational fields, topics and participating actors. The ITiB project is part of the accompanying research, in which we aim to understand the cognitive structures of innovation and transfer from a meta perspective. Within ITiB, we study the underlying processes of innovation and transfer, recognising innovation and transfer as social processes. In our project, we focus on the stakeholders, their interactions and interpretation processes (DANIEL-SÖLTENFUß et al., 2022, 2024).

Figure 3: Illustration in sketchnoting style (see also KÜCKMANN, 2023a). Please click here for an enlarged version of Figure 3. [45]

We conducted problem-centered interviews (PZI) (Witzel, 2000) with a sample of 33 participants, interviewing up to three representatives from each InnoVET project. The participants were selected using a purposive sampling approach, in particular, criterion sampling (MISOCH, 2019 [2015]). As they had to fulfil the criterion of responsibility in the main project, we interviewed the managers of the overarching project networks. The interview schedule had three main parts: 1. the understandings of innovation and transfer, 2. the design of innovation and transfer in the respective InnoVET project, and 3. the InnoVET network and its potential to support innovation and transfer. The order and wording of the questions were adjusted depending on the course of each interview and the interviewers ensured that all topics in the interview schedule were discussed. In the first part, there were narrative questions regarding the images and associations that came into the minds of the participants. The interviews lasted between 50 and 95 minutes and were conducted in German via a video conferencing tool3). They were recorded and transcribed by the interviewers. The data were then analysed using qualitative content analysis according to KUCKARTZ and RÄDIKER (2022). [46]

For the first part of the interviews, while a researcher conducted the interviews, the author of the present paper simultaneously prepared the sketchnotes protocols, which we discussed with the interviewees following the main part of the interview. We ensured that the participants reviewed their initial statements or our interpretations regarding their subjective definitions of innovation and transfer immediately, and reflected and commented upon their coherence. Additional narrative was generated by the protocols. The following excerpt from the interview transcript presents the beginning of such a narrative:4)

"I2: Well, so if you are still missing crucial points or if you have a hint or if you have some thoughts about individual illustrations (.), then please share them with us again. (..)

P17B1_1: Hmm (...) Hmm (...) what about with this stick figure, what is coming out of the belly? [...]

I2: I'll have to check where you are—you are probably referring to competence. [...] Well, that is... it's a way of representing competence, that is in a way 'internal' [...] it is supposed to illustrate competence [P17B1_1: Oh okay], especially digital skills.

P17B1_1: Yes, I would like to explain once again what we mean by digital competence [I2: Yes, very gladly]. It would be a great pity if we left the conversation and it didn't come up. Because I think that's one of the real pitfalls of the project, because we always have to make sure that everyone understands it correctly. Above all, of course, especially regarding the participants, we don't want to somehow (.) raise false expectations."

Figure 4: Protocol excerpt (translated from German) [47]

This excerpt was followed by extensive narratives which were part of the data set. The interview situation could be enriched and the interview was expanded accordingly. The sketchnoting protocol was then adjusted as necessary, ensuring consensus. In this example, the sketchnote (see Figure 4) was adapted as follows (see Figure 5).

Figure 5: Adaptation of the sketchnoting protocol based on the complementary narration (translated from German) [48]

In addition to the immediate adjustments, we also sent the participants the protocol within one or two days with a request to review it. In this way, the participants could check whether they agreed with the representations or whether there was a need for clarification, addition, adjustment or discussion. Further discussions were held on this basis. In the context of the present study, by using member checking, we created a consensus between researchers and participants. In this approach, consensus is based on a certain visual-reflexive saturation, indicated by a narrative coda. [49]

We used the protocols and resulting sketchnoting artefacts as a basis for initial cross-case analyses. They were analysed directly after the interviews, based on deductive and inductive categories (KUCKARTZ & RÄDIKER, 2022). The aim was to establish initial findings which were introduced into the academic discourse in a timely manner to support the research processes (REICHERTZ, 2000, 2016), and to provide further information on the category system on which the systematic evaluation of the interviews was based. It was possible to enter the (academic) discourse without compromising on quality (REICHERTZ, 2000, §72). The initial analysis offered a further reflexive basis for evaluation in addition to theoretical elaboration. The evaluation was then carried out by four researchers, one of whom was the author of the present paper and the sketchnoter. In this way, different interpretative backgrounds were included (REICHERTZ, 2016). Our research group met regularly to discuss key examples and inductive categories. We used the sketchnoting protocols as a tool for reflection, a reference point for discussion and as a case-related memory aid (REICHERTZ, 2013). Furthermore, supplementary information for subsequent case studies was provided. [50]

The next step involves critically reflecting on the descriptions, highlighting both the opportunities and the challenges of this member checking practice, and laying the foundation for examining the relationship between underlying validity assumptions and sketchnoting in validation practices. The following represents a "reflexive space" according to ZHAO et al. (2016, §2). [51]

The first step is to focus on the research relationships (BUCHBINDER, 2011). Communication quality was certainly improved. The degree of openness of the participants and the quality of the connection to the participants were improved, for example (MRUCK & MEY, 2000). The approach had direct implications for the interview situation. It was possible to share understandings with the participants directly. Participants mentioned that they therefore received something in return. The fact that the protocols were created simultaneously was significant, as the sketchnoting allowed for an immediate reaction (REILLY, 2013), which supported a more natural speaking situation (CHASE, 2017). Participants stated that their insights were valued during the interview situation itself. This supported a conducive balance of power between researchers and participants (BUCHBINDER, 2011) which had a positive effect on the degree of openness of the exchange (CARLSON, 2010). Thus, the in-process sketchnoting allowed the participants to play an active part in the research process (HOLZWARTH, 2019; REICHERTZ, 2021). In the context of our study, we created an atmosphere that was conducive to dialogue, reflected in the feedback from participants. It was possible to access or elicit further underlying meanings by moving away from a purely textual presentation. This became apparent during the study through increased and deep exchange following the main period of data collection and the researchers' perceived differences in attributions of meaning. In the present study, several misunderstandings were revealed and discussed. Thus, the aim of transactional validity was achieved using the validation practice. [52]

Participants subsequently shared with the research group that they used the sketchnoting results for their innovative project work (for example, in team meetings, presentations and dialogue at conferences). This is an example of the transformational validity of using sketchnoting. For instance, two participants stated that at a project meeting shortly after the interview, they discussed mutual understandings of innovation and transfer. The participants were sensitised to possible differences through the interview study. In the context of the study, the participants of the 17 InnoVET projects considered different understandings of innovation. The spectrum ranged from the ambition to develop something completely new to applying tried and tested procedures, on the assumption that new developments are impossible (DANIEL-SÖLTENFUß et al., 2022). The participants concluded that it would be worth discussing mutual understanding in the wider project group. They commented upon how differently people approached the question of transfer, for example. Finally, they developed transfer plans. In this respect, the participants described changes in their project work that they directly related to their participation in the interview study. [53]

Therefore, the aims of transactional and transformational validity were supported by the validation practice. The validation potential of sketchnoting was demonstrated by the study. [54]

Possible challenges include the question as to whether sketchnoting could place excessive demands on the research process, although sketchnoting does not require any prior clarification due to its experimental and playful structural principles (KÜCKMANN, 2023b). The participants accepted this communication form in the study. However, the question remains whether specific skills are required and to what extent this method is feasible for researchers. Sketchnoting is indeed easy to learn: "Sketchnoting, if seen as a methodology, provides a framework that is based on low fidelity and low complex visual outputs—everything can be depicted through combinations of dots, lines, circles, squares, and triangles" (PAEPCKE-HJELTNESS, MINA & CYAMANI, 2017, p.1). In other words, one does not need specific skills. Rather, the question arises as to whether the additional effort is worthwhile in the context of the aims of qualitative social research. I have put forward both theoretical and practical lines of argument to answer this question in the affirmative. [55]

In this paper, I discussed an innovative member checking approach using sketchnoting. I explored both theoretical and practical insights and sketchnoting's potential for supporting processes of mutual reflection. In contrast to the argument put forward by CHO and TRENT (2006), communication validity is supported by the validation product in my view. Thus, by using sketchnoting as an instrument, the validity of generalisations is, to a certain extent, turned on its head (REICHERTZ, 2000), since abstraction is enhanced by the generalisation. Through using sketchnoting, researchers can uncover misunderstandings and eliminate them. However, as reception and production go hand in hand in the approach, both researchers and participants may gain new insights as part of the discussion of the sketchnote. These insights can contribute to change and validation from a transformational viewpoint. To sum up, using sketchnoting within member checking, researchers support a holistic, process-oriented view of validity and foster the iterative-processual logic inherent in qualitative research. [56]

Embedding sketchnoting within the broader methodological literature on visual methods and comparing them with each other, as well as exploring the potential of sketchnoting in other research methods, are areas for future research. [57]

I would like to thank the anonymous reviewers of this paper for their helpful comments and suggestions which have much improved this paper. A special acknowledgement goes to Stephanie WILDE for her extensive work proofreading this paper and to all colleagues involved for their critical comments on this contribution. I would also like to thank the participants of the 20th anniversary conference of the Sektion Methoden der qualitativen Sozialforschung [Methods of Qualitative Social Research Section] of the DGS for their questions and discussions during the event.

1) I presented this poster at the anniversary conference of the Sektion Methoden der qualitativen Sozialforschung [Methods of Qualitative Social Research Section] of the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Soziologie (DGS) [German Sociological Association] in June 2023 (KÜCKMANN, 2023a). <back>

2) All translations from non-English texts are mine. <back>

3) For a critical analysis of virtual interviews see NICKLICH, RÖBENACK, SAUER, SCHREYER and TIHLARIK(2023). <back>

4) I2 = Interviewer 2, P17B1_1 = Project 17, Respondent 1, Interview 1. <back>

Becker, Howard S. (2002). Visual evidence: A seventh man, the specified generalization, and the work of the reader. Visual Studies, 17(1), 3-11.

Bloor, Michael (1997). Techniques of validation in qualitative research: A critical commentary. In Robert Dingwall & Gale E. Miller (Eds.), Context and method in qualitative research (pp.38-50). London: Sage.

Boehm, Gottfried (1994). Was ist ein Bild?, München: Fink.

Bohnsack, Ralf (2003). Qualitative Methoden der Bildinterpretation. Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft, 6(2), 239-256.

Brear, Michelle (2019). Process and outcomes of a recursive, dialogic member checking approach: A project ethnography. Qualitative Health Research, 29(7), 944-957.

Breuer, Franz & Reichertz, Jo (2001). Standards of social research. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 2(3), Art. 24. https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-2.3.919 [Accessed: January 16, 2025].

Buchbinder, Eli (2011). Beyond checking: Experiences of the validation interview. Qualitative Social Work, 10(1), 106-122.

Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (BMBF) (2019). Förderrichtlinien zur Durchführung des Bundeswettbewerbs "Zukunft gestalten – Innovationen für eine exzellente berufliche Bildung (InnoVET)". Bundesanzeiger, 17. Oktober, https://www.bmbf.de/bmbf/shareddocs/bekanntmachungen/de/2019/01/2217_bekanntmachung.html [Accessed: January 16, 2025].

Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (BMBF) (2021). Exzellenz fördern. Berufsbildung stärken: Wie die InnoVET-Projekte die berufliche Bildung in Deutschland voranbringen. Bonn: BMBF, https://www.inno-vet.de/SharedDocs/Publikationen/de/innovet/Exzellenz_foerdern_Berufsbildung_staerken.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=6 [Accessed: January 16, 2025].

Candela, Amber G. (2019). Exploring the function of member checking. The Qualitative Report, 24(3), 619-628, https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2019.3726 [Accessed: January 16, 2025].

Carlson, Julie A. (2010). Avoiding traps in member checking. The Qualitative Report, 15(5), 1102-1113, https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2010.1332 [Accessed: January 16, 2025].

Chase, Elizabeth (2017). Enhanced member checks: Reflections and insights from a participant-researcher collaboration. The Qualitative Report, 22(10), 2689-2703, https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2017.2957 [Accessed: January 16, 2025].

Cho, Jeasik & Trent, Allen (2006). Validity in qualitative research revisited. Qualitative Research, 6(3), 319-340.

Chua, Mel & Adams, Robin S. (2014). Using realtime transcription to do member-checking during interviews. IEEE Frontiers in Education Conference (FIE) Proceedings, 1-3, https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/7044251 [Accessed: January 16, 2025].

Creswell, John W. (2005 [2002]). Educational research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative Research. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

Creswell, John W. & Miller, Dana L. (2000). Determining validity in qualitative inquiry. Theory into Practice, 39(3), 124-130.

Daniel-Söltenfuß, Desiree; Kremer, H.-Hugo & Kückmann, Marie-Ann (2022). Innovations- und Transferprozesse in der beruflichen Bildung als Forschungs- und Entwicklungsgegenstand: Verständnisse, Praktiken und Gestaltung, Zeitschrift für Berufs- und Wirtschaftspädagogik, 118(4), 684-686.

Daniel-Söltenfuß, Desiree; Kremer, H.-Hugo & Kückmann, Marie-Ann (2024). Go with the flow?! Transferverständnisse und -strategien als Grundlage der Gestaltung von Transferprozessen im Kontext des InnoVET-Programms. In Kristina Kögler, H.-Hugo Kremer & Volkmar Herkner (Eds.), Jahrbuch der berufs- und wirtschaftspädagogischen Forschung 2024 (pp.182-197). Opladen: Verlag Barbara Budrich, https://doi.org/10.3224/84743054 [Accessed: January 16, 2025].

Danner, Helmut (2006 [1979]). Methoden geisteswissenschaftlicher Pädagogik. München: Ernst Reinhardt Verlag.

Doelker, Christian (2002 [1997]). Ein Bild ist mehr als ein Bild: Visuelle Kompetenz in der Multimedia-Gesellschaft. Stuttgart: Klett-Cotta.

Doyle, Susanna (2007). Member checking with older women: A framework for negotiating meaning. Health Care for Women International, 28(10), 888-908.

Flick, Uwe (2018 [2007]). Managing quality in qualitative research. London: Sage.

Flick, Uwe (2020). Gütekriterien qualitativer Forschung. In Günter Mey & Katja Mruck (Eds.), Handbuch Qualitative Forschung in der Psychologie (Vol. 2, pp.247-263). Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Forbat, Liz & Henderson, Jeanette (2005). Theoretical and practical reflections on sharing transcripts with participants. Qualitative Health Research, 15(8), 1114-1128.

Gansemer-Topf, Ann M.; Paepcke-Hjeltness, Verena; Russell, Ann E. & Schiltz, James (2021). "Drawing" your own conclusions: Sketchnoting as a pedagogical tool for teaching ecology. Innovative Higher Education, 46, 303-319.

Hammersley, Martyn & Atkinson, Paul (1995 [1983]). Ethnography: Principles in practice. London: Routledge.

Harper, Douglas (1988). Visual sociology: Expanding sociological vision. The American Sociologist, 19, 54-70.

Harper, Douglas (2002). Talking about pictures: A case for photo elicitation. Visual Studies, 17(1), 13-26.

Harper, Douglas (2005 [1994]), What's new visually? In Norman K. Denzin & Yvonna S. Lincoln (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of qualitative research (Vol. 3, pp.747-762). London: Sage.

Hegel, Georg Wilhelm Friederich (1952 [1807]). Phänomenologie des Geistes. Berlin: Akademie-Verlag.

Holzwarth, Peter (2019). Visuelle Methoden. In Ingo Bosse, Jan-René Schluchter & Isabel Zorn (Eds.), Handbuch Inklusion und Medienbildung (pp.376-382). Weinheim: Beltz Juventa.

Huber, Andreas (2001). Die Angst des Wissenschaftlers vor der Ästhetik: Zu Jo Reichertz: Zur Gültigkeit von Qualitativer Sozialforschung. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 2(2), Art. 1, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-2.2.961 [Accessed: January 16, 2025].

Jörissen, Benjamin (2011). "Medienbildung": Begriffsverständnisse und -reichweiten. In Heinz Moser, Petra Grell & Horst Niesyto (Eds.), Medienbildung und Medienkompetenz: Beiträge zu Schlüsselbegriffen der Medienpädagogik (pp.211-235). München: kopaed, https://doi.org/10.21240/mpaed/20/2011.09.20.X [Accessed: January 16, 2025].

Jörissen, Benjamin (2014). Medialität und Subjektivation: Strukturale Medienbildung unter besonderer Berücksichtigung einer Historischen Anthropologie des Subjekts. Habilitation, Fakultät für Geistes-, Sozial- und Erziehungswissenschaften, Otto-von-Guericke-Universität Magdeburg, Germany, https://d-nb.info/1054639035/34 [Accessed: January 16, 2025].

Kant, Immanuel (1966 [1791]). Kritik der reinen Vernunft. Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft.

Kiener, Urs & Schanne, Michael (2001). Kontextualisierung, Autorität, Kommunikation: Ein Beitrag zur FQS-Debatte über Qualitätskriterien in der interpretativen Sozialforschung. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 2(2), Art. 2, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-2.2.962 [Accessed: January 16, 2025].

Koelsch, Lori E. (2013). Reconceptualizing the member check interview. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 12, 168-179, https://doi.org/10.1177/160940691301200105 [Accessed: January 16, 2025].

Kuckartz, Udo & Rädiker, Stefan (2022). Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse: Methoden, Praxis, Computerunterstützung. Weinheim: Beltz Juventa.

Kückmann, Marie-Ann (2023a). Worth a Thousands Words?! Kommunikative Validierung mittels Sketchnoting als neuer Impuls im Kontext der Diskussion über die Qualität qualitativer Sozialforschung. Poster, Anniversary conference, Sektion Methoden der qualitativen Sozialforschung, Deutsche Gesellschaft für Soziologie, June 22-23, Mainz, Germany, https://soziologie.de/sektionen/methoden-der-qualitativen-sozialforschung/veranstaltungen/jubilaeumstagung-in-mainz-2023 [Accessed: January 16, 2025].

Kückmann, Marie-Ann (2023b). "Ich sehe was, was du nicht siehst ..." Zu den Potenzialen von Sketchnoting im Kontext Inklusiver Medienbildung. MedienPädagogik, 20, 619-647, https://doi.org/10.21240/mpaed/jb20/2023.09.23.X [Accessed: January 16, 2025].

Kückmann, Marie-Ann & Kundisch, Heike (2021). Denken mit dem Stift?! – Digitale Visualisierungsprozesse als Zugang zu komplexen wirtschafts- und berufspädagogischen Themenfeldern. bwp@ Berufs- und Wirtschaftspädagogik – online, 40, 1-28, https://www.bwpat.de/ausgabe40/kueckmann_kundisch_bwpat40.pdf [Accessed: January 16, 2025].

Lamnek, Siegfried (2010 [1988]). Qualitative Sozialforschung. Weinheim: Beltz.

Lankshear, Colin & Knobel, Michele (2004). A handbook for teacher research. New York, NY: Open University Press.

Lather, Patti A. (1995). The validity of angels: Interpretive and textual strategies in researching the lives of women with HIV/AIDS. Qualitative Inquiry, 1(1), 41-68.

Laucken, Uwe (2002). Quality criteria as instruments for political control of sciences. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 3(1), Art. 6, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-3.1.888 [Accessed: January 16, 2025].

Lincoln, Yvonna S. & Guba, Egon G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Lobinger, Katharina. (2012). Visuelle Kommunikationsforschung. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Maybee, Julie E. (2020 [2016]). Hegel's dialectics. In Edward N. Zalta (Ed.), The Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy, https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2020/entries/hegel-dialectics/ [Accessed: January 16, 2025].

Mey, Günter & Dietrich, Marc (2016). From text to image: Shaping a visual grounded theory methodology. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 17(2), Art. 2, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-17.2.2535 [Accessed: January 16, 2025].

Misoch, Sabrina (2019 [2015]). Qualitative Interviews. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Mitchell, W.J. Thomas (1986). Iconology. Image, text, ideology. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

Mruck, Katja & Mey, Günter (2000). Germany. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 1(1), Art. 4, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-1.1.1114 [Accessed: January 16, 2025].

Nicklich, Manuel; Röbenack, Silke; Sauer, Stefan; Schreyer, Jasmin & Tihlarik, Amelie (2023). Qualitative social research at a distance: Potentials and challenges of virtual interviews. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 24(1), Art. 15, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-24.1.4010 [Accessed: January 16, 2025].

Paepcke-Hjeltness, Verena; Mina, Mani & Cyamani, Aziza (2017). Sketchnoting: A new approach to developing visual communication ability, improving critical thinking and creative confidence for engineering and design students. Conference Paper, 2017 IEEE Frontiers in Education Conference (FIE), October 18-21. Indianapolis, USA.

Peirce, Charles S. (1983 [1903]). Phänomen und Logik der Zeichen. Frankfurt/M.: Suhrkamp.

Pink, Sarah (2012). Advances in visual methodology. London: Sage.

Pink, Sarah (2021 [2001]). Doing visual ethnography. London: Sage.

Reichertz, Jo (2000). Zur Gültigkeit von Qualitativer Sozialforschung. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 1(2), Art. 32, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-1.2.1101 [Accessed: January 16, 2025].

Reichertz, Jo (2013). Gemeinsam Interpretieren: Die Gruppeninterpretation als kommunikativer Prozess. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Reichertz, Jo (2016). Qualitative und interpretative Sozialforschung: Eine Einladung. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Reichertz, Jo (2017). Neues in der qualitativen und interpretativen Sozialforschung?. Zeitschrift für Qualitative Forschung, 18(1), 71-89, https://doi.org/10.3224/zqf.v18i1.06 [Accessed: January 16, 2025].

Reichertz, Jo (2019). Method police or quality assurance? Two patterns of interpretation in the struggle for supremacy in qualitative social research. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 20(1), Art. 3, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-20.1.3205 [Accessed: January 16, 2025].

Reichertz, Jo (2021). Limits of interpretation or interpretation at the limits: Perspectives from hermeneutics on the re-figuration of space and cross-cultural comparison. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 22(2), Art. 18, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-22.2.3737 [Accessed: January 16, 2025].

Reilly, Rosemary C. (2013). Found poems, member checking and crises of representation. The Qualitative Report, 18(15), 1-18, https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2013.1534 [Accessed: January 16, 2025].

Rohde, Mike (2020). What are Sketchnotes?. Blog, https://rohdesign.com/sketchnotes [Accessed: January 16, 2025].

Rose, Gillian (2014). On the relation between "visual research methods" and contemporary visual culture. The Sociological Review, 62(1), 24-46.

Schneijderberg, Christian (2023). Conventions of quality criteria of empirical social research. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 24(3), Art. 1. https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-24.3.3994 [Accessed: January 16, 2025].

Schwabl, Franziska (2020). Inszenierungen im digitalen Bild: Eine Rekonstruktion der Selfie-Praktiken Jugendlicher mittels der dokumentarischen Bildinterpretation. Detmold: Eusl.

Seale, Clive (1999). The quality of qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Simpson, Amber & Quigley, Cassie F. (2016). Member checking process with adolescent students: Not just reading a transcript. The Qualitative Report, 21(2), 376-392, https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2016.2386 [Accessed: January 16, 2025].

Steinke, Ines (1999). Kriterien qualitativer Forschung: Ansätze zur Bewertung qualitativ-empirischer Sozialforschung. Weinheim: Juventa.

Steinke, Ines (2003). Gütekriterien qualitativer Forschung. In Uwe Flick, Ernst von Kardorff & Ines Steinke (Eds.), Qualitative Forschung. Ein Handbuch (pp.319-331). Reinbek: Rowohlt.

Steinke, Ines (2004). Quality criteria in qualitative research. In Uwe Flick, Ernst von Kardorff & Ines Steinke (Eds.), A companion to qualitative research (pp.184-190). London: Sage.

Stige, Brynjulf; Malterud, Kirsti & Midtgarden, Torjus (2009). Toward an agenda for evaluation of qualitative research. Qualitative Health Research, 19(10), 1504-1516.

Stiles, William B. (1993). Quality-control in qualitative research. Clinical Psychology Review, 13(6), 593-618.

Stöckl, Hartmut (2004). In between modes: Language and image in printed media. In Eija Ventola, Cassily Charles & Martin Kaltenbacher (Eds.), Perspectives on multimodality (pp.9-30). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Stöckl, Hartmut (2009). The language-image-text: Theoretical and analytical inroads into semiotic complexity. Arbeiten aus Anglistik und Amerikanistik, 34(2), 203-226.

Stöckl, Hartmut (2011). Sprache-Bild-Texte lesen: Bausteine zur Methodik einer Grundkompetenz. In Hajo Diekmannshenke, Michael Klemm & Hartmut Stöckl (Eds.), Bildlinguistik. Theorien – Methoden – Fallbeispiele (pp.43-70). Berlin: Erich Schmidt.

Strübing, Jörg; Hirschauer, Stefan; Ayaß, Ruth; Krähnke, Uwe & Scheffer, Thomas (2018). Gütekriterien qualitativer Sozialforschung: Ein Diskussionsanstoß. Zeitschrift für Soziologie, 47(2), 83-100, https://doi.org/10.1515/zfsoz-2018-1006 [Accessed: January 16, 2025].

Tracy, Sarah J. (2010). Qualitative quality: Eight "big-tent" criteria for excellent qualitative research. Qualitative Inquiry, 16(10), 837-851.

Welsh, Elaine (2002). Dealing with data: Using NVivo in the qualitative data analysis process. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 3(2), Art. 26, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-3.2.865 [Accessed: January 16, 2025].

Whittemore, Robin; Chase, Susan K. & Mandle, Carol Lynn (2001). Validity in qualitative research. Qualitative Health Research, 11(4), 522-537.

Witzel, Andreas (2000). The problem-centered Interview. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 1(1), Art. 22, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-1.1.1132 [Accessed: March 10, 2025].

Zhao, Pengfei; Li, Peiwei; Ross, Karen & Dennis, Barbara (2016). Methodological tool or methodology? Beyond instrumentality and efficiency with qualitative data analysis software. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 17(2), Art. 16, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-17.2.2597 [Accessed: January 16, 2025].

Marie-Ann KÜCKMANN is an assistant professor at the Institute for Vocational Education (ibp) at the University of Rostock, Germany. In her research, she focuses on social transformation processes, inclusive media education, and teacher training in vocational education and training (VET).

Contact:

Marie-Ann Kückmann

University of Rostock

Institute for Vocational Education (ibp)

28 August-Bebel-Strasse, 18055 Rostock

Germany

E-mail: marie-ann.kueckmann@uni-rostock.de

URL: https://www.ibp.uni-rostock.de/marie-ann-kueckmann/

Kückmann, Marie-Ann (2025). Is a picture worth a thousand words? Member checking using the sketchnoting approach [57 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 26(2), Art. 5, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-26.2.4224.