Volume 26, No. 2, Art. 2 – May 2025

The Use of Coding in a Situational Analysis of the Political Participation of Indigenous People in Chile's Constitutional Process

Héctor Turra Chico

Abstract: In situational analysis (SA), various procedures are available, including coding and mapping, each serving distinct purposes at different levels of the research process. In this article, I present a case regarding the uses of coding based on a research project focused on the political participation of Indigenous peoples in Chile's constitutional process. The motivation for this article stems from the challenges I encountered as a newcomer to SA.

Within the research process, coding—used alongside other techniques like mapping—played a crucial role in enabling engagement with the data and tackling analytical challenges. In the initial stage, coding helped identify various elements and discourses in the constitutional process that were essential to the project's findings. In a later stage, it assisted in redeveloping a positional map that initially did not reflect the full spectrum of discursive positions. In vivo codes also fostered interdisciplinary connections among bodies of literature in political science and education. These applications of coding can benefit other researchers, particularly those who are new to the methodology.

Key words: situational analysis; coding; grounded theory methods; situational analysis coding; situational analysis mapping

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. Situational Analysis's Relevance in Social Science Research

3. Coding and Its Application in SA Research

4. A Case of the Use of Coding in an SA Project: The Political Participation of Indigenous People in the Chilean Constitutional Process

4.1 Coding with SA mapping

4.2 Reorganizing the analysis with in vivo coding

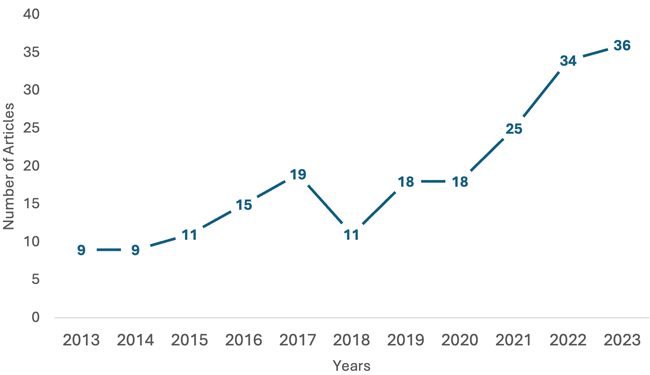

5. Discussion

6. Conclusion

CLARKE (2003, 2005) originally developed situational analysis (SA) as an extension of grounded theory methodology (GTM). A major distinction is that while in GTM coding is used as a main tool to study basic social processes (CHARMAZ, 2015a), SA encompasses a set of tools to examine the ecology of relations constitutive of situations (CLARKE, FRIESE & WASHBURN, 2018). The analytical devices of SA include four distinctive mapping techniques: Situational, relational, social world and arenas, and positional maps (CLARKE, WASHBURN & FRIESE, 2022). Situational maps focus on identifying the human and non-human elements that co-constitute a situation; relational maps aid in identifying and navigating the relations among these different elements; social worlds/arenas (SW/A) maps address the collective or institutional dimension of the situation by focusing on social worlds within arenas of commitment (CLARKE, 2005; CLARKE et al., 2018); positional maps focus on discursive positions "taken and not taken" (CLARKE, 2005, p.XXII) around controversial issues of interest. In SA, these maps are often developed with other tools, such as GTM coding and memoing, and serve to examine, synthesize, and represent different dimensions of a situation (DEN OUTER, HANDLEY & PRICE, 2013; KNOPP, 2021; VALDERRAMA PINEDA, 2016). [1]

Despite the meaningful methodological interconnections between GTM and SA, CLARKE et al. (2018) described the analytical differences between GTM and SA, stressing that "SA maps are a separate and different form of analysis from GT" (p.108). They explained that while GTM analysis focuses on the study of social action and interaction through coding, the organization of codes in categories and analytical diagrams of categories and processes, SA focuses on the ecologies of relations among different types of elements, social groupings and discourses mainly through memoing and mapping (ibid.). [2]

However, open coding strategies are beneficial in situational analysis. The benefits of coding in SA analysis include enhancing researchers' familiarity with the data both before and during mapping, fostering "relational modes of analysis" (p.107) through the concurrent examination of data alongside other practices (e.g., memoing and mapping), and organizing the data collected as it accumulates during the research. Notably, coding in SA is always tentative as it connotes that "data are open to multiple, simultaneous interpretations and codes. There is no one right reading. All readings are temporary, partial, provisional, and perspectival—situated historically and geographically" (p.26). Based on post-qualitative theories, SA authors have emphasized that researchers can use coding with other SA tools flexibly and interpretively to grapple with different analytical dimensions and with different purposes (CLARKE et al., 2018; FRIESE, SCHWERTEL & TIETJE, 2023). This approach to coding echoes SA's deconstructive emphasis as it seeks not to represent someone's truth but to disassemble data and build interpretations of the situation under study (CLARKE et al., 2018). The interpretive and deconstructive emphasis on coding in SA contrasts with more structured forms of coding stemming from positivist and post-positivist research paradigms (CHARMAZ, 2015b; KENNY & FOURIE, 2015). [3]

In this article, I use my doctoral research project to illustrate the uses of coding in SA. In my project, I focused on the political participation of Indigenous people during Chile's 2020-2023 constitutional process. This situation is relevant because Indigenous people's relationship with the Chilean state has historically been distant and openly conflictive (BOCCARA & SEGUEL-BOCCARA, 2005; CHIHUAILAF, 2018; FIGUEROA HUENCHO, 2021). However, in 2020, citizens experienced a unique political process whereby Indigenous and non-Indigenous citizens participated in a referendum to rewrite the Chilean constitution. This extraordinary situation established a new stage in the formal political participation of Indigenous people, who had salient roles during the reform process (ALVARADO LINCOPI, 2021; LONCÓN, 2023). For instance, the first body responsible for drafting a new constitutional proposal included seventeen reserved seats for Indigenous communities, and its first president was Indigenous scholar Elisa LONCÓN (SENADO DE LA REPÚBLICA DE CHILE, 2020). In the research, I focused on examining the involvement of Indigenous actors in Chile's political landscape; therefore, my questions addressed the interactions among human elements and discourses that co-constituted this participation in the Chilean constitutional process. [4]

I decided to use SA because it enabled me to examine Indigenous people's political participation as a set of relations among various elements. These elements included Indigenous and non-Indigenous groups, political collectives, international institutions and agreements, and various discourses on relevant areas of interest in their own relational ecology (CLARKE et al., 2022). I conceived the project with a critical lens (i.e., with a focus on the manifestations of power in the interactions and discourses involving Indigenous people during the constitutional process). Therefore, during the data collection and analysis, I emphasized Indigenous people's voices to shed light on their struggles and challenges when entering formal political spaces in Chile. SA facilitated the close examination of the relationships involving Indigenous actors and the discourses to deliberate Indigenous people's political participation and the recognition of their rights at play during the constitutional process (CLARKE et al., 2018). [5]

During the analysis, I was confronted with pivotal analytical decisions regarding identifying and representing the relationships among multiple human elements and discourses in SA maps. Coding was a helpful strategy for building new perspectives and providing a language to represent the complex interactions in the constitutional process. These aspects of my experience as a newcomer to SA motivated me to offer this empirical example presented here. [6]

For the remainder of this paper, I will refer to my study as a case—I will discuss the key characteristics of my application of SA and the implications of my methodological decisions to the outcome of my analysis. I will describe how different paths of initial coding—open (KENNY & FOURIE, 2015) and in vivo (MANNING, 2017)—and focused coding (CHARMAZ, 2015a) helped me become familiar with the data and overcome "analytical paralysis" (CLARKE et al., 2018 p.108). I will also discuss how coding triggered interdisciplinary connections between a body of literature in the political sciences concerning the use of emotions in political interactions and educational research literature on politicization—a learning process denoting the evolution of political concepts, practices, and identities (CURNOW, 2022). I will underscore the uses of coding as an interpretive device that facilitated the unfolding of my analyses alongside SA mapping and other SA methodological processes. [7]

The case I present in the article offers possible uses of coding within SA analysis. Following MacLURE (2013a, 2013b), I approach coding as an interpretive strategy to trigger "wonder" (MacLURE, 2013a, p.164) in qualitative research (i.e., as a flexible strategy for an unstructured exploration of the situation that can fulfill various functions, depending on the research questions and the emphases of research projects). The examples I show are in no way prescriptive, systematic, or part of a "well-wrought coding scheme" (MacLURE, 2013b, p.229). Instead, they are intended to stimulate reflection on how researchers could use coding—particularly novice researchers and newcomers to SA—to build situated interpretations sustained on the relationship between the researcher and the data (MacLURE, 2013a, 2013b). My focus on coding as an SA methodological tool is connected to a larger discussion focused on the relevance of SA in grappling with complex social phenomena. [8]

In Section 2, I address the relevance of SA in social science research and its increasing application across various disciplines as well as interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary research. Next, in Section 3, I introduce coding in qualitative research by referencing foundational literature on SA that connects coding in GTM with SA. I present an empirical example of coding based on my doctoral project (Section 4) and discuss the uses of coding and its benefits, drawing on current SA literature (Section 5). Finally, I conclude by synthesizing the primary coding applications within the research project and highlighting the relevance of these examples for novice researchers and newcomers to SA in Section 6. [9]

2. Situational Analysis's Relevance in Social Science Research

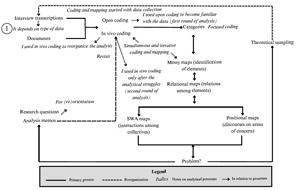

Situational analysis is increasingly applied in various disciplines. For instance, a search in the Scopus index (keywords "situational analysis" AND "Clarke" AND "map" OR "mapping" AND "relational") shows a steady increase between 2013 and 2023 in the number of articles published in English using this theory/methods package or its methodological tools (see Figure 1). Researchers often justified the use of SA mapping as helping them capture the complex interplay of actors, elements, and discourses in social phenomena studied in fields such as public health (LYNCH, HANCKEL & GREEN, 2022; PIEL, VON KÖPPEN & APFELBACHER, 2022), education (DEN OUTER et al., 2013; RUCK & MANNION, 2020), environmental sciences (ALONSO-YAÑEZ, THUMLERT & DE CASTELL, 2016; GLÜCK, 2018), and political sciences (DE SHALIT, GUTA, VAN DER MEULEN, LAFOREST & ORSINI, 2024; KALENDA, 2016).

Figure 1: Number of articles with reported use of SA methodological tools in the Scopus index between 2013 and 2023 [10]

Researchers have underscored the benefits of SA in analyzing situations that require multi-, inter-, or trans-disciplinary lenses (CHEN, 2022; KALENDA, 2016). KALENDA (2016) suggested that SA's integration of different theoretical approaches—such as symbolic interactionism (BLUMER, 1969), Foucauldian discourse analysis (FOUCAULT, 1979 [1975]), STRAUSS's (1978) social worlds theory, and science and technology studies (LATOUR & WOOLGAR, 1979), among others—offers a comprehensive approach that avoids the limitations of single-discipline perspectives on social phenomena. Furthermore, CHEN (2022) emphasized that SA facilitates avoiding hegemonic tendencies where one discipline dominates others by supporting balanced interdisciplinary cooperation. This balanced approach to examining social phenomena fosters a more equitable and effective integration of diverse scientific approaches during research projects that require more than one disciplinary lens (ibid., see also KLING, 2023). [11]

DE SHALIT et al. (2024), KALENDA (2016), and POHLMANN and COLELL (2020) also suggested that SA facilitates interdisciplinary approaches and the use of multisite data sets to examine political phenomena. For instance, POHLMANN and COLELL (2020) recognized that interdisciplinary approaches operationalized through SA mapping allowed them to elucidate how groups of actors—or social worlds—develop to collaborate and compete to maintain, deepen, alter, or shift power relationships in the interactions between a community energy movement and political stakeholders in Germany. Other researchers have claimed that SA also contributes to uncovering the discourses and silences at play in interactions in the political realm (DE SHALIT et al., 2024). Overall, researchers often referred to the usefulness of SA mapping in analyzing and representing complex political situations that require interdisciplinary lenses (ibid., see also POHLMANN & COLELL, 2020; WHITLEY, 2024). [12]

Despite these strengths, some authors lamented the lack of detailed guidance and reporting on how GTM coding can be productively used with SA (OFFENBERGER, 2023). In my search (see Figure 1), five of the thirty-six 2023 articles included analysis information, and only two articles (ATALLAH et al., 2023; WAZINSKI, WANKA, KYLÉN, SLAUG & SCHMIDT, 2023) included examples of how GTM coding can be used in SA projects. [13]

In the following section, I discuss the use of coding strategies in qualitative research and draw connections between coding in GTM and SA. I emphasize its multiple analytical possibilities (CLARKE et al., 2018; MacLURE, 2013a) and some considerations stemming from using coding with SA. [14]

3. Coding and Its Application in SA Research

Coding is an analytical process through which researchers examine the data by identifying recurring themes, categories, or concepts within a body of data (AKKAYA, 2023; CHARMAZ, 2006; SALDAÑA, 2016). The primary goal is to discern patterns of order, enabling the condensation of vast amounts of data into digestible and interpretable forms (SALDAÑA, 2016). Thus, coding serves as the crucial linkage between the data collected and the explanation of what these data mean (CHARMAZ, 2001). The procedures, types of coding, and subsequent organization vary depending on the purposes of the analysis, which are often tied to underlying theories and paradigms. [15]

MacLURE (2013a) problematized the use of coding in qualitative research by offering a non-linear distinction of coding as a classification process or to trigger wonder. A relevant critique of coding as classification—often tied to qualitative research under positivist and post-positivist paradigms—is that it can impose a rigid, hierarchical structure on data, potentially oversimplifying the richness and complexity of human experiences (ST. PIERRE & JACKSON, 2014). This type of coding risks distancing the researcher from the data, fostering an illusion of interpretive dominion (CHARMAZ, 2015b; MacLURE, 2013a). These coding practices might not fully accommodate qualitative data's fluid, dynamic nature, potentially overlooking the nuances and idiosyncrasies vital for a deeper understanding of social phenomena (ST. PIERRE & JACKSON, 2014). In contrast, when used as a process of wonder or interpretively—often meaning flexibly and reflectively (MacLURE, 2013a)—coding can accommodate this complexity, allowing researchers to balance structure and the inherent unpredictability of human experiences (CHARMAZ, 2015b; MacLURE, 2013a, 2013b). [16]

This problematization of coding as classification or wonder (MacLURE, 2013a) aids in grappling with the different coding approaches in GTM traditions. Researchers have distinguished three major GTM traditions: Classic, Straussian, and constructivist GTM, which have different approaches to coding (CHARMAZ, 2015a; KENNY & FOURIE, 2015). In all three traditions, GTM coding includes distinctive approaches to initial coding—labelling of data segments to denote a concept or area of concern—and focused coding—to identify recurrent codes—in the analytical practices (ibid.). For instance, classic GTM uses a constant comparison method for coding. It pursues objectivity through the unobtrusive discovery of grounded theory within collected data (KENNY & FOURIE, 2015), which speaks to the positivist underpinnings of this tradition (CHARMAZ, 2006; JONES & ALONY, 2011). While not seeking objectivity, Straussian GTM coding is highly systematic and rigorous (KENNY & FOURIE, 2015). In contrast, constructivist GTM coding is more interpretative, intuitive, and impressionistic than classic or Straussian GTM (CHARMAZ, 2006). [17]

In SA's foundational books (CLARKE, 2005, CLARKE et al., 2018; CLARKE et al., 2022), the authors drew connections between constructivist GTM and SA. In describing its methodological considerations, SA authors assert that both methodological processes could "work beautifully together, allowing the researcher to feature processual and/or relational analytics" (CLARKE et al., 2018, p.108). Moreover, SA foundational literature (CLARKE, 2005; CLARKE et al., 2018; CLARKE et al., 2022) redirects the readers' attention to constructivist GTM literature for guidance on coding when addressing the usefulness of coding in SA analysis. Following this orientation, I applied a constructivist GTM approach during the research project (CHARMAZ, 2008, 2015a, 2015b). [18]

CLARKE et al. (2018) suggested not including GTM codes in SA maps because the GTM focus is on conducting analyses in search of a "basic social process" (CHARMAZ, 2015a, p.403; CORBIN & STRAUSS, 2008, p.266; MORSE, 1994, p.39) and not necessarily on the ecology of relations that constitute a situation (CLARKE et al., 2018). Instead, SA authors recommended using in vivo codes—words or phrases from the participants' language as codes during data analysis (MANNING, 2017; SALDAÑA, 2016)— as one possibility to advance SA analyses—because, for example, they could shed light on the discourses at play in a situation, thus facilitating the analysis of positional maps (CLARKE et al., 2018). [19]

The use of in vivo coding was significant in my project in analyzing the discourses regarding Indigenous people's political participation and ensuring that the analysis remains somewhat grounded in participants' own words (MANNING, 2017). I focused on identifying in vivo codes to highlight the perspectives of Indigenous participants, which are often overlooked in other studies of political participation. It is relevant to point out that to maintain the attention beyond the knowing subject—a major emphasis of SA (CLARKE et al., 2018) — I complemented these analyses with other processes, such as memoing and mapping, to grapple with the relational ecology of a situation with more-than-human considerations (CLARKE, 2005; CLARKE et al., 2018; CLARKE et al., 2022). [20]

Another dimension of the discussion of coding in SA projects is the question of what data source to code. In the context of an interview regarding SA, WASHBURN, KLAGES and MAZUR (2023) recently affirmed that "part of the issue with codes is that first, oftentimes codes are based on—not always, but oftentimes—interview data and that really limits our source[s] of data" (p.8). Considering that researchers need to capture multiple data types to capture a situation of inquiry fully (CLARKE et al., 2018), WASHBURN et al. (2023) opened the door to questions regarding whether all data sources need to go through the same processes. Despite the proposition that coding can be used with different types of data such as memos, observational protocols, images, and videos (CLARKE et al., 2022), FRIESE et al. (2023) confirmed that FRIESE used coding only to scrutinize interviews in her doctoral project. They also reiterated that coding and mapping were two different analytical paths to operationalize different levels of analysis with different purposes. [21]

Despite the differences between SA and GTM's analytical processes, SA authors and users have emphasized the usefulness of coding in SA projects. First, CLARKE et al. (2018) encouraged using GTM coding to familiarize oneself with research project data. Moreover, MATHAR (2008) and WHISKER (2018) suggested that open and focused codes should not be dismissed when developing SA projects because these, alongside mapping, contribute to understanding the situation's messiness. One way of doing so is to use open and focused coding in conjunction with SA mapping in order to identify the different human and non-human elements co-constituting the situation and to elucidate some aspects of their relationships. For instance, CAXAJ and COHEN (2021) described that as part of inquiry, they reviewed "preliminary codes by organizing them in terms of situations, social worlds and discursive positions" (p.253). [22]

Yet, there is a lack of examples of coding practices in empirical SA studies. For instance, OFFENBERGER (2023) presented the use of coding in different SA projects in Germany. However, she focused on the reflections of multiple researchers regarding the use of coding and did not provide specific details of the coding forms, the codes constructed in the various projects, and how they were used in developing SA maps. Moreover, in my review of articles on SA (see Figure 1), I showed that most researchers using SA did not report details on their coding practices. [23]

4. A Case of the Use of Coding in an SA Project: The Political Participation of Indigenous People in the Chilean Constitutional Process

In this section, I will refer to the case of coding in my study by presenting the processes I applied during three analytical phases. To do so, I developed Figure 2 to introduce and synthesize the coding application in my project, underscoring its connections to other SA methodological processes. The processes presented in Figure 2 are not a systematic and fixed formula (MacLURE 2013a, 2013b) but a synthesis of my experience using coding in the project. I will then present the uses of coding focused on two themes: Coding with SA mapping and reorganizing the analysis with in vivo coding.

Figure 2: Coding application in relation to other methodological processes. Please click here for an enlarged version of Figure 2. [24]

In Figure 2, I emphasized the iterative and simultaneous application of coding and mapping, as working in this manner was crucial in triggering curiosity (MacLURE, 2013a) and finding avenues to advance my analysis. I also highlight how theoretical sampling, revisiting memos, and returning to the overarching research questions helped to overcome analytical paralysis. [25]

The examples and ideas regarding coding in SA I show in the following subsections are based on a data subset that includes interviews (n=8) and documents (n=15). My original data subset also included observations of constitutional activities. I only coded the data from the interviews and documents and analyzed the observations through memoing. The interviewees were participants of political collectives with representation in the 2021-2022 Chilean Constitutional Convention (CC), which was the responsible entity in charge of writing the first constitution proposal in 2022. The documents included the guidelines for a consultation with Indigenous people, a second document with the results of this consultation, and several news articles published at different moments of the constitutional process. In the following subsections, I delve into the uses of coding in my research project, focusing on the two themes. [26]

I started the data organization by transcribing the interviews verbatim and organizing the documents into three categories: Indigenous communities' open communications, CC documents, and written news articles. I pasted the transcriptions and original texts into individual spreadsheets, one per interview and document. In the spreadsheets, I pasted the texts, keeping one line of text in one row to identify and highlight relevant ideas. Following SA recommendations, I started the open coding when I selected the first document and after the first interview (CLARKE et al., 2018) and followed a constructivist GTM approach to open coding to identify the "chief concern of participants" (CHARMAZ, 2008, p.163). Simultaneously, I started developing different versions of messy and organized SA maps. Table 1 presents examples of quotes and initial open codes that facilitated the identification of individual and collective human actors, non-human elements, areas of interest within the situation, and discourses regarding the political participation of Indigenous people.

|

Quotes |

Open Codes |

|

"There was a political game of alliances. Indigenous representatives decided what to include, they had the support to do so." |

Political interactions between Indigenous and non-Indigenous representatives |

|

"The territorial dispute and the resistance against the elite's power." |

Indigenous territorial demands |

|

"The indigenous law system was presented as a parallel system which it was not." |

Misrepresenting the implications of Indigenous rights |

|

"The supporters [of the PS] seek a deep transformation." |

Creating conditions for negative political transformation with the PS |

|

"Their lands were taken, and many people had to emigrate to Santiago." |

Historical Indigenous struggles |

Table 1: Examples of open codes used in the initial stage of analysis [27]

The initial coding process and the simultaneous development of messy and organized maps allowed me to become familiar with the data. The initial coding and mapping facilitated the identification of categories of actors or collective human elements (CLARKE et al., 2018) that were key to understanding the situation and provided insights into the differences between these groups and how these differences played a role in their interactions. For instance, coding aided in distinguishing the commitments of Indigenous and non-Indigenous political representatives, two of the most relevant players in the constitutional process arena. On the one hand, Indigenous representatives' main commitment was to bring Indigenous communities' agendas into formal political spaces (see Codes 2 and 5 in Table 1). On the other hand, non-Indigenous commitments were concerned with applying national legislation and preventing significant alterations of the social and political status quo (see Code 4 in Table 1). I used these differences in the groups' commitments to build two distinctive social worlds in later versions of SW/A maps. [28]

After a few iterations of mapping and coding, the distinction between Indigenous and non-Indigenous representatives turned out to be more relevant, as it significantly impacted the relationships among actors and the discourses at the center of Indigenous people's participation. For instance, the competing perspectives of Indigenous and non-Indigenous groups were the foundation of the discourses about the plurinational state (PS)—a political model for the state's organization recognizing that multiple nations coexist within the Chilean territory (LONCÓN, 2023)—which played a significant role in the outcomes of the constitutional process. In the following subsection, I use the example of the PS to refer to the usefulness of in vivo coding during a particular analytical challenge. [29]

4.2 Reorganizing the analysis with in vivo coding

In a later stage of my analysis, I developed positional maps using only a data subset comprising written news pieces presenting discourses regarding the PS, which became an analytical challenge. The PS was one of the proposed political models in the constitutional process, and it encompassed the recognition of several constitutional rights for Indigenous people. When I presented the map to my supervisory committee, they rapidly identified that the maps did not represent a comprehensive range of discursive positions about the PS. The two main reasons for this feedback were the polarized perspectives presented in the news and the need to include data from different sources beyond written news to capture a full range of positions, which is encouraged in SA projects (CLARKE et al., 2018). [30]

This interaction with the data led me to a state of "analytical paralysis" (p.108), making it difficult to proceed with new versions of the map. For instance, I incorporated data from my original dataset but kept returning to similar discursive positions about the PS in new iterations of the map. At this stage, my supervisor recommended using theoretical sampling (CONLON, TIMONEN, ELLIOTT-O'DARE, O'KEEFFE & FOLEY, 2020), which included adding new documents and observing additional constitutional activities. She also suggested doing another coding round for the entire data set. [31]

I incorporated a new set of documents and observations of constitutional activities, including Indigenous communities' open written communications published in traditional and social media and additional publicly available recorded discussions about the meaning and implications of the PS. I selected these documents and activities after I revisited the research proposal to refocus on the research objectives. I used in vivo coding in the new iteration of the analysis with all the data (original data set and the additions after the theoretical sampling). This meant that I purposefully sought out participants' statements which could serve as in vivo codes. During this iteration, I identified 567 in vivo codes. I then engaged in focused coding to identify similar in vivo codes that shed light on discourses and some of the relationships among collectives that I could group as sensitizing thematic categories. I created two levels of thematic categories based on the focused coding while drafting multiple versions of positional and SW/A maps. I present some examples of these in vivo codes, the grouping categories and the general themes I identified below in Table 2.

|

Examples of In Vivo Codes |

Categories |

General Themes |

|

1. Most of us have Indigenous origins |

a) Insights into Chilean, Indigenous identity, and mestizaje |

Reclaiming an Indigenous identity |

|

2. Colonial relations have not allowed social growth 3. There are differences between Chileans and Indigenous people |

b) Social relations among Indigenous and non-Indigenous people |

|

|

4. Constitutional recognition of their [Indigenous] rights |

c) Historical struggles of Indigenous people |

|

|

5. Representatives are not attuned to Indigenous demands. 6. Indigenous reserved seats represented an Indigenous elite |

d) Issues of political representation of Indigenous people |

The representation of Indigenous interests through elected officials in the constitutional process is problematic for Indigenous and non-Indigenous citizens |

|

7. People feared that their houses could be taken because of the restitution of Indigenous land 8. The PS sought the refoundation of the state |

e) The implications of the PS trigger emotional responses |

|

|

9. Without input from Indigenous communities 10. Indigenous representatives prioritized political parties |

f) Silence of Indigenous people in formal political spaces |

|

|

11. People saw these [rights] as privileges for Indigenous people |

g) Indigenous rights are privileges |

|

Table 2: Examples of in vivo codes, categories and larger themes used to create multiple versions of SW/A and positional maps [32]

The in vivo codes turned my attention to some of the details of the interactions among different political stakeholders. For instance, I paid attention to the narratives regarding the daily struggles of CC representatives to advocate for Indigenous people in this formal political space. Focused coding allowed me to group several codes related to problematic relationships and actions regarding the political representation of Indigenous people (see Codes 5-10 in Table 2). This issue was intrinsically connected to the interactions between Indigenous and non-Indigenous political representatives I had identified in the initial coding round. This analytical avenue led me to re-focus on a SW/A map emphasizing Indigenous and non-Indigenous membership worlds. [33]

In vivo codes also provided a new language to explain the relations between these worlds. For instance, non-Indigenous politicians claimed that Indigenous representatives were "not attuned to Indigenous demands" (see Code 5 in Table 2), which helped explain how these two worlds competed for citizens' representation in the political arena. The in vivo codes provided nuanced insights into the daily activities of CC representatives and a new language to explain the relationship between social worlds. These benefits exemplify how in vivo coding aided in advancing the analysis with the SW/A maps. [34]

As for the positional maps, I also noticed that a group of in vivo codes was related to processes that led to the exclusion of Indigenous communities' voices during the articulation of the plurinational state (PS) in the constitutional proposal. For instance, Codes 5, 6 and 8 in Table 2 build the narrative that the PS was not necessarily a demand of Indigenous people but a proposal of an Indigenous elite not attuned to grassroots Indigenous demands. These narratives allowed me to focus on potential discursive silences when developing new positional map iterations. [35]

These silences appeared to be intrinsically connected to the interactions (or actions analyzed in the SW/A maps) within formal political spaces that often tuned out the perspectives of Indigenous communities. These circumstances made it difficult for some Indigenous actors to voice and include their perspectives directly in some constitutional developments, such as articulating the PS model in the 2022 constitutional proposal, creating the conditions for a discursive silence regarding Indigenous people's perspective on the political model. This silence of Indigenous communities also speaks to the more significant issues of political representation (as presented in Table 2), which were relevant dimensions of the analyses I presented in my doctoral dissertation. This is an example of the usefulness of how in vivo coding helped me reorganize the analysis after the challenges to advance with the original positional map that only included pieces of news regarding the plurinational state (PS). [36]

Additionally, the notion that "people feared that their houses could be taken because of the restitution of Indigenous land" (Code 7 in Table 2) was productive in articulating a discursive position in the positional maps concerning the PS. This code sparked questions regarding the potential effects of emotions on citizens' politicization developments, which in turn led me to study additional literature on political sciences and education. The issue of fear is connected to a body of literature on political science addressing how political discourses are used to trigger emotional responses to affect political interactions (JONES, 2020; KOSCHUT, 2019; SHAH, 2022). From an interactionist perspective, appealing to emotional responses in the political realm was a relevant dimension to articulate the processes of becoming political or citizens' politicization (CURNOW, DAVIS & ASHER, 2019), a construct developed within education research. [37]

The initial interdisciplinary connection described above also allowed me to turn my attention to identity as a salient facet of citizens' politicization during the constitutional process (ibid., see also CURNOW, 2022). For instance, the discussion about what political model best suited Chile and the arguments employed to debate different positions were intricately connected to ideas of what it means to be Chilean and its Indigenous dimension. The arguments and narratives used to discuss the PS, such as the ones emphasizing that there were "differences between Chileans and Indigenous" (Code 3 in Table 2) and that some rights "privileges for Indigenous People" (Code 11 in Table 2), were connected to the identity dimension of the conversation and sought emotional responses in the political realm (JONES, 2020; KOSHUT, 2019; SHAH, 2022). By providing a nuanced presentation of data, in vivo coding triggered my engagement with these bodies of literature, facilitating interdisciplinary connections in my research. [38]

Initial—open and in vivo—and focused coding played a significant role during the analysis stage of my SA project. Specifically, they were helpful in the identification of relevant individual and collective actors, preponderant discourses and areas of interest in the situation I attempted to construct. When done iteratively with mapping at an early stage, coding helped me to identify relevant relationships among actors and their positions concerning areas of interest, such as the relationships between Indigenous and non-Indigenous representatives when discussing the recognition of Indigenous people's constitutional rights. This was mainly due to the possibility of interacting with the data through codes, which assisted in discerning productive analytical avenues that otherwise can be difficult to read in raw data and to include in the SA maps. The experiences of using open coding in this project followed SA authors' and researchers' suggestions regarding the use of coding to become familiar with the overall collected data (CLARKE et al., 2022; MATHAR, 2008; WHISKER, 2018). This is also attuned to the research emphasizing the usefulness of this type of coding as a methodological facilitator to identify human and non-human elements, discourses and relationships among them and as a device to interrogate data prior to or parallel to SA maps (CLARKE et al., 2018; CAXAJ & COHEN, 2021; OFFENBERGER, 2023). [39]

Another relevant use of coding is related to the reorganization of SA analyses. Shifting the coding strategy, in this case, from open to in vivo coding, can also be a valuable facilitator to overcome "analytical paralysis" (CLARKE et al., 2018, p.108). In the case presented in this article, the reorganization of the analysis using in vivo coding was relevant for two reasons. First, after the paralysis triggered during the development of the first version of the positional map, the use of in vivo coding provided a more nuanced understanding of the interactions between collectives during the constitutional process that was particularly helpful in developing new iterations of SW/A maps. They also allowed me to pay attention to the silences of Indigenous People during moments of the constitutional discussion, which became a relevant area of interest in new versions of positional maps. Second, the grounded analysis through in vivo coding helped me to identify new ways to describe the research findings for both SW/A and positional maps. Similar to the ideas proposed by CLARKE et al., the grounded accounts of how participants experienced the different activities and conversations in the constitutional process provided language and ideas to construct positional maps as well as nuanced narratives to describe interactions among different collectives and the discourses at play during the political event. [40]

By paying attention to the specificities of participants' and documents' narratives and language, in vivo coding also facilitated drawing interdisciplinary connections. SA's emphasis on discourse and its implications for social practice (ibid.) allowed me to connect participants' narratives regarding fear to the literature that addresses the trigger of emotional responses in political interactions (JONES, 2020; KOSCHUT, 2019; SHAH, 2022). In turn, I connected these emotional responses and how they could be seen as a relevant dimension of citizens' politicization developments (CURNOW, 2022; CURNOW et al., 2019), a framework developed by educational researchers. This benefit of finding connections between disciplinary fields—in this case, enabled by in vivo coding—is aligned with the body of research addressing the pertinence of SA and its methodological tools to address the situation from multiple disciplinary fields (CHEN, 2022; KALENDA, 2016). [41]

This interdisciplinary connection had significant implications for the study because it established a pathway to emphasize the relevance of identity in citizens' politicization (CURNOW, 2022; CURNOW et al., 2019). Indigenous voices and struggles brought forward in the constitutional process provided a platform to discuss what it means to be Chilean, whether there is only one way to understand Chilean identity, and the implications of political models in reflecting these understandings. The debate surrounding the political model proposals and identity encompassed different arguments, including those aimed at triggering citizens' emotional responses, such as Codes 1, 7 and 11 in Table 2. These interdisciplinary analyses were sparked by the in vivo codes and the simultaneous construction of SW/A and positional SA maps. [42]

The empirical case I presented underscored coding as a device that can trigger wonder (MacLURE, 2013a) in SA projects. Open coding facilitated the preliminary identification of actors and areas of interest, which raised questions that led me to explore silences and issues of problematic political representation affecting Indigenous communities. A salient dimension of the case was the shifting of the coding strategy to in vivo coding, which aided in overcoming a period of analytical challenges during the research. In vivo codes provided grounded accounts on areas of interest, facilitating more nuanced analyses of interactions and discourses based on participants' language. The in vivo codes provided details about how some discourses about the PS affected citizens emotionally, which, in turn, impacted their political positioning during the constitutional process. In this regard, in vivo codes offered a translational language to draw interdisciplinary connections between political science and education literature. I support the idea that there is not one way of using coding in SA (FRIESE et al., 2023; WASHBURN et al., 2023); rather, it is a flexible and interpretive-oriented device that researchers can use in multiple ways to think through the complexities of a given situation (MacLURE, 2013a; FRIESE et al., 2023; WASHBURN et al., 2023). [43]

The example of coding in the project could be particularly useful to SA newcomers and novice researchers. It could encourage others to find their own analytic paths in SA projects and eventually aid in navigating analytical paralyses when delimiting the situation, identifying relevant actors and areas of interest, and building versions of SA maps. The case presented here is relevant due to the lack of empirical examples of using coding and its interpretive potential in SA analyses (OFFENBERGER, 2023; SMIT, 2006; WHISKER, 2018). [44]

I would like to thank Gabriela ALONSO-YAÑEZ, Rachel WASHBURN, and Roberta RICE for their invaluable guidance in writing this article. I also sincerely thank Katja MRUCK and the journal reviewers for their time and insightful comments.

I acknowledge the financial support I received from the Chilean National Agency of Research and Innovation (ANID), which funded my doctoral research through the Beca Doctorado en el extranjero 72210064.

Akkaya, Burcu (2023). Grounded theory approaches: A comprehensive examination of systematic design data coding. International Journal of Contemporary Educational Research, 10(1), Art. 89, https://doi.org/10.33200/ijcer.1188910 [Accessed: June 7, 2024].

Alonso-Yañez, Gabriela; Thumlert, Kurt & de Castell, Suzanne (2016). Re-mapping integrative conservation: (Dis) coordinate participation in a biosphere reserve in Mexico. Conservation and Society, 14(2), 134-145, https://doi.org/10.4103/0972-4923.186335 [Accessed: November 20, 2024].

Alvarado Lincopi, Claudio (2021). A de-monumentalizating revolt in Chile. From the whitened nation to the plurinational political community. Social Identities, 27(5), 555-566.

Atallah, Devin; Koslouski, Jessica; Perkins, Kesha; Marscio, Christine; Robinson, Rhyann; Del Rio, Michelle & Porche, Michelle (2023). The trauma and learning policy initiative (TLPI)'s inquiry‐based process: Mapping systems change toward resilience. Journal of Community Psychology, 51(7), 2943-2963.

Blumer, Herbert (1969). Symbolic interactionism: Perspective and method. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Boccara, Guillaume & Seguel-Boccara, Ingrid (2005). Políticas indígenas en Chile (siglos XIX y XX) de la asimilación al pluralismo – El caso Mapuche [Indigenous politics in Chile (XIX and XX centuries)—The Mapuche case]. Nuevo Mundo, Mundos Nuevos, https://doi.org/10.4000/nuevomundo.594 [Accessed: February 13, 2024].

Caxaj, Susana & Cohen, Amy (2021). Emerging best practices for supporting temporary migrant farmworkers in Western Canada. Health & Social Care in the Community, 29(1), 250-258.

Charmaz, Kathy (2001). Grounded theory: Methodology and theory construction. In Nei J. Smelser & Paul B. Baltes (Eds.), International encyclopedia of the social & behavioral sciences (1st ed.). (pp.6396-6399). Amsterdam: Pergamon.

Charmaz, Kathy (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. London: Sage.

Charmaz, Kathy (2008). Grounded theory as an emergent method. In Sharlene Hesse-Biber & Patricia Leavy (Eds.), Handbook of emergent methods (pp.155-170). New York: Guilford Press.

Charmaz, Kathy (2015a). Grounded theory: Methodology and theory construction. In Nei J. Smelser & Paul B. Baltes (Eds.), International encyclopedia of the social & behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). (pp.402-407). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Charmaz, Kathy (2015b). Teaching theory construction with initial grounded theory tools: A reflection on lessons and learning. Qualitative Health Research, 25(12), 1610-1622.

Chen, Jia-Shin (2022). Situational analysis as an interdisciplinary research method. East Asian Science, Technology and Society, 16(4), 537-541.

Chihuailaf, Arauco (2018). Los indígenas en el escenario político de finales del siglo XX [Indigenous people in the political scenario of the XX century]. Amérique Latine Histoire & Mémoire, 36, https://doi.org/10.4000/alhim.7255 [Accessed: March 4, 2024].

Clarke, Adele (2003). Situational analyses: Grounded theory mapping after the postmodern turn. Symbolic Interaction, 26(4), 553-576.

Clarke, Adele (2005). Situational analysis: Grounded theory after the postmodern turn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Clarke, Adele; Friese, Carrie & Washburn, Rachel (2018). Situational analysis: Grounded theory after the interpretive turn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Clarke, Adele; Washburn, Rachel & Friese, Carrie (2022). Situational analysis in practice. Mapping relationalities across disciplines. New York, NY: Routledge.

Conlon, Catherine; Timonen, Virpi; Elliott-O'Dare, Catherine; O'Keeffe, Sorcha & Foley, Geraldine (2020). Confused about theoretical sampling? Engaging theoretical sampling in diverse grounded theory studies. Qualitative Health Research, 30(6), 947-959.

Corbin, Juliet M. & Strauss, Anselm L. (2008). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (3rd ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Curnow, Joe (2022). Radical shifts: Prefiguring activist politicization through legitimate peripheral participation. Peabody Journal of Education, 97(5), 553-566.

Curnow, Joe; Davis, Amil & Asher, Lila (2019). Politicization in process: Developing political concepts, practices, epistemologies, and identities through activist engagement. American Educational Research Journal, 56(3), 716-752.

De Shalit, Ann; Guta, Adrial; van der Meulen, Emily; Laforest, Rachel, & Orsini, Michael (2024). Discursive positions on charitable sector advocacy in Canada: A situational analysis. Critical Policy Studies, 18(2), 227-246.

den Outer, Birgit; Handley, Karen & Price, Margaret (2013). Situational analysis and mapping for use in education research: A reflexive methodology?. Studies in Higher Education, 38(10), 1504-1521.

Figueroa Huencho, Verónica (2021). Mapuche movements in Chile: From resistance to political recognition. Georgetown Journal of International Affairs, May 21, https://gjia.georgetown.edu/2021/05/21/mapuche-movements-in-chile-from-resistance-to-political-recognition/ [Accessed: May 12, 2024].

Foucault, Michael (1979 [1975]). Discipline and punish: The birth of the prison. New York, NY: Vintage Books.

Friese, Carrie; Schwertel, Tamara & Tietje, Olaf (2023). On creative flexibility and its burden: An interview with Carrie Friese on doing situational analysis. In Leslie Gauditz, Anna-Lisa Klages, Stefanie Kruse, Eva Marr, Ana Mazur, Tamara Schwertel & Olaf Tietje (Eds.) Die Situationsanalyse als Forschungsprogramm (pp.39-51). Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Glück, Sarah (2018). Making energy cultures visible with situational analysis. Energy Research & Social Science, 45, 43-55.

Jones, Katherine (2020). Men too: Masculinities and contraceptive politics in late twentieth century Britain. Contemporary British History, 34(1), 44-70.

Jones, Michael & Alony, Irit (2011). Guiding the use of grounded theory in doctoral studies—An example from the Australian film industry. International Journal of Doctoral Studies, 6, 95-114, https://doi.org/10.28945/1429 [Accessed: January 21, 2024].

Kalenda, Jan (2016). Situational analysis as a framework for interdisciplinary research in the social sciences. Human Affairs, 26, 340–355, https://doi.org/10.1515/humaff-2016-0029 [Accessed: April 11, 2024].

Kenny, Méabh & Fourie, Robert (2015). Contrasting classic, Straussian, and constructivist grounded theory: Methodological and philosophical conflicts. Qualitative Report, 20(8), 1270-1289, https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2015.2251 [Accessed: January 21, 2024].

Kling, Norbert (2023). Linking situational analysis to architecture and urbanism. An interdisciplinary perspective. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 24(2), Art. 16, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-24.2.4084 [Accessed: May 15, 2024].

Knopp, Philipp (2021). Mapping temporalities and processes with situational analysis: Methodological issues and advances. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 22(3), Art. 4, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-22.3.3661 [Accessed: May 15, 2024].

Koschut, Simon (2019). Can the bereaved speak? Emotional governance and the contested meanings of grief after the Berlin terror attack. Journal of International Political Theory, 15(2), 148-166.

Latour, Bruno & Woolgar, Steve (1979). Laboratory life: The social construction of scientific facts. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Loncón, Elisa (2023). The Mapuche struggle for the recognition of its nation. Harvard Review of Latin America, April 20, https://revista.drclas.harvard.edu/the-mapuche-struggle-for-the-recognition-of-its-nation-from-a-feminine-and-decolonizing-point-of-view/ [Accessed: December 15, 2023].

Lynch, Rebecca; Hanckel, Benjamin & Green, Judith (2022). The (failed) promise of multimorbidity: Chronicity, biomedical categories, and public health. Critical Public Health, 32(4), 450-461, https://doi.org/10.1080/09581596.2021.2017854 [Accessed: November 6, 2024].

MacLure, Maggie (2013a). Classification or wonder? Coding as an analytic practice in qualitative research. In Rebecca Coleman & Jessica Ringrose (Eds.), Deleuze and research methodologies (pp.164-183). Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

MacLure, Maggie (2013b). The wonder of data. Cultural Studies, Critical Methodologies, 13(4), 228-232.

Manning, Jimmie (2017). In vivo coding. In Jorge Matthes (Ed.), The international encyclopedia of communication research methods (pp.1-2). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell.

Mathar, Tom (2008). Review essay: Making a mess with situational analysis?. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 9(2), Art. 4, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-9.2.432 [Accessed: April 7, 2024].

Morse, Janice (1994). "Emerging from the Data." Cognitive processes of analysis in qualitative research. In Janice Morse (Ed.), Critical issues in qualitative research methods (pp.23-41). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Offenberger, Ursula (2023). Situational analysis as a traveling concept: Mapping, coding and the role of hermeneutics. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 24(2), Art. 2, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-24.2.4021 [Accessed: April 7, 2024].

Piel, Julia: von Köppen, Marilena & Apfelbacher, Christian (2022). Politics in search of evidence- The role of public health in the COVID pandemic in Germany: Protocol for a situational analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(24), https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192416486 [Accessed: November 6, 2024].

Pohlmann, Angela, & Colell, Arwen (2020). Distributing power: Community energy movements claiming the grid in Berlin and Hamburg. Utilities Policy, 65, 1-14.

Ruck, Andy & Mannion, Greg (2020). Fieldnotes and situational analysis in environmental education research: experiments in new materialism. Environmental Education Research, 26(9-10), 1373-1390.

Saldaña, Johnny (2016). An introduction to codes and coding. In Johnny Saldana (Ed.), The coding manual for qualitative researchers (pp.1-31). London: Sage.

Senado de la República de Chile (2020). Ya es una realidad: escaños reservados para pueblos originarios en la convención constituyente [Already a reality: Reserved seats for originary peoples in the constitutional convention], https://tramitacion.senado.cl/noticias/pueblos-originarios/ya-es-una-realidad-escanos-reservados-para-pueblos-originarios-en-la [Accessed: January 5, 2024].

Shah, Tamanna M. (2022). Emotions in politics: A review of contemporary perspectives and trends. International Political Science Abstracts, 74(1), 1-14, https://doi.org/10.1177/00208345241232769 [Accessed: August 14, 2024].

Smit, Jakobus (2006). Book review: Situational analysis: Grounded theory after the postmodern turn. Qualitative Research, 6(4), 560-562.

St. Pierre, Elizabeth & Jackson, Alecia (2014). Qualitative data analysis after coding. Qualitative Inquiry, 20(6), 715-719.

Strauss, Anselm L. (1978). A social world perspective. Studies in Symbolic Interaction, 1, 119-128.

Valderrama Pineda, Andrés (2016). Disabilities, the design of urban transport systems and the city: A situational analysis. Universitas Humanística, 81, 281-304, https://doi.org/doi:10.11144/Javeriana.uh81.ddut [Accessed: January 22, 2024].

Washburn, Rachel; Klages, Anna-Lisa & Mazur, Ana (2023). Reflections on situational analysis and its use for analyzing visual discourses. In Leslie Gauditz, Anna-Lisa Klages, Stefanie Kruse, Eva Marr, Ana Mazur, Tamara Schwertel & Olaf Tietje (Eds.) Die Situationsanalyse als Forschungsprogramm (pp.53-66). Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Wazinski, Karla; Wanka, Anna; Kylén, Maya; Slaug, Björn & Schmidt, Steven (2023). Mapping transitions in the life course—An exploration of process ontological potentials and limits of situational analysis. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 24(2), Art. 29, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-24.2.4088 [Date of Access: June 3, 2024].

Whisker, Craig (2018). Review: Adele E. Clarke, Carrie Friese & Rachel S. Washburn (2018). Situational analysis: Grounded theory after the interpretive turn. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 19(3), Art. 35, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-19.3.3138 [Date of Access: June 2, 2024].

Whitley, Hannah (2024). Exogenous, endogenous, and peripheral actors: A situational analysis of stakeholder inclusion within transboundary water governance. Sustainability, 16(9), https://doi.org/10.3390/su16093647 [Date of Access: September 23, 2024].

Héctor TURRA CHICO is an adjunct professor at the Faculty of Education at Universidad Católica de Temuco, Chile. His main research areas include transdisciplinary collaborations involving scientists, academics, and local and Indigenous communities in Latin America, Indigenous political participation, and social learning. He applies qualitative methodologies and draws inspiration from interpretive, discourse, and critical theories.

Contact:

Dr. Héctor Turra Chico

Universidad Católica de Temuco

Rudecindo Ortega 02950, 4781312

Temuco, Chile

E-mail: hturra@uct.cl

Turra Chico, Héctor (2025). The use of coding in a situational analysis of the political participation of Indigenous people in Chile's constitutional process [44 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 26(2), Art. 2, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-26.2.4256.