Volume 26, No. 2, Art. 4 – May 2025

When Sense-Making Doesn't Make Sense: Dervin's Sense-Making Methodology Applied to the Question of Non-Māori Librarians in New Zealand Making Sense of Māori Knowledge

Kathryn Oxborrow Vambe

Abstract: The use of DERVIN's sense-making methodology in a study of non-Māori librarians learning about and engaging with mātauranga Māori [Māori knowledge] led to a number of useful findings, but also revealed a raft of methodological challenges. These showed that DERVIN's sense-making is not the best approach to investigating majority culture individuals engaging with the knowledge of Indigenous or other minoritised cultures. There were some challenges with the gap phase of the sense-making metaphor of situation-gap-bridge-outcome. These include artificial and anticipated gaps, avoided gaps, and gaps that are fully or partially invisible to the sense-maker. Other problems included sense-makers seeing their journeys differently to that described by the sense-making metaphor, and the linearity of it. These concerns all point to the central challenge for the use of sense-making for investigating non-Māori engagement with Māori knowledge—that the framework was produced from a Western cultural perspective, and thus reflects a very individualistic view of information behaviour.

Key words: sense-making methodology; Indigenous knowledge; Māori knowledge; librarians; professional development; application of methodology

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review: DERVIN's Sense-Making Methodology

2.1 Introduction to sense-making methodology

2.2 Applications of sense-making methodology

3. Methodology: Sense-Making Life-Line Interviewing and Focus Groups

4. Limitations of DERVIN's Sense-Making for Investigating Non-Māori Librarians' Learning and Engagement with Māori knowledge

4.1 Artificial and anticipated gaps

4.2 Avoided gaps

4.3 When gaps are invisible to the sense-maker

4.4 Interviewees conceptualise their journeys differently from sense-making

4.5 The linearity of the model

4.6 DERVIN's sense-making approach influenced by a Western perspective

5. Application of sense-making methodology in my study

6. Conclusion

The sense-making methodology (SMM) of the late Brenda DERVIN and colleagues (e.g. DERVIN, 2003; DERVIN & NILAN, 1986; FOREMAN-WERNET & DERVIN, 2017) has long been a highly influential research approach. Originally developed in the discipline of communication studies, it has been widely embraced by the field of library and information studies, due to the role played by information in sense-making (e.g. KELLY, 2021). SMM was central to my own doctoral research (OXBORROW, 2020) in which I sought to investigate how non-Māori librarians in Aotearoa New Zealand learn about and engage with mātauranga Māori [Māori knowledge]1).

"The term 'mātauranga Māori' encompasses all branches of Māori knowledge, past, present and still developing. It is like a super subject because it includes a whole range of subjects that are familiar in our world today, such as philosophy, astronomy, mathematics, language, history, education and so on. And it will also include subjects we have not yet heard about. Mātauranga Māori has no ending: it will continue to grow for generations to come" (MEAD, 2016, pp.337-338). [1]

The most basic translations of mātauranga Māori are "Māori knowledge" (MEAD, 2012, p.9; see also MOORFIELD, 2011, p.102) or "traditional knowledge" (DURIE, 1997, p.7), but the concept has a much more nuanced meaning than that, as can be seen from the quote above. MEAD (2016, p.338) wrote that mātauranga Māori incorporates cultural knowledge such as tikanga Māori [the customary system of values and practices that have developed over time and are deeply embedded in the social context]. This is also reflected in the definition of MEAD (2012, p.9): "Māori knowledge complete with its values and attitudes", which I adopted for the purposes of my project. Authors have stated that mātauranga Māori is not only a repository of knowledge, but also a way of knowing (MEAD, 2016; WAITANGI TRIBUNAL, 2011). As part of the research, I also asked the methodological question of whether SMM was a suitable approach for investigating this particular topic. I was interested to note that DERVIN (1983, 1998) described the sense-making stages of situation, gap, bridge and outcome as universals of human sense making, and was keen to investigate whether the approach could be used successfully in a context that had not before been attempted. While I was able to use SMM in my research to discover important themes about the topic, I also found there were multiple problems which made it a less than optimal approach for investigating sense-making in this particular context. [2]

In this paper, I will first give a brief introduction to the methodological literature on SMM (Section 2.1), followed by reviewing a selection of SMM studies (Section 2.2). I will then explain the context of my research and the way I used SMM (Section 3), and detail the issues that meant it did not perform optimally in the context I was investigating (Section 4). Given the subject matter, it is necessary at some points to use terms in te reo Māori [the Māori language, definition from TE HUIA, 2016, p.734]. [3]

2. Literature Review: DERVIN's Sense-Making Methodology

2.1 Introduction to sense-making methodology

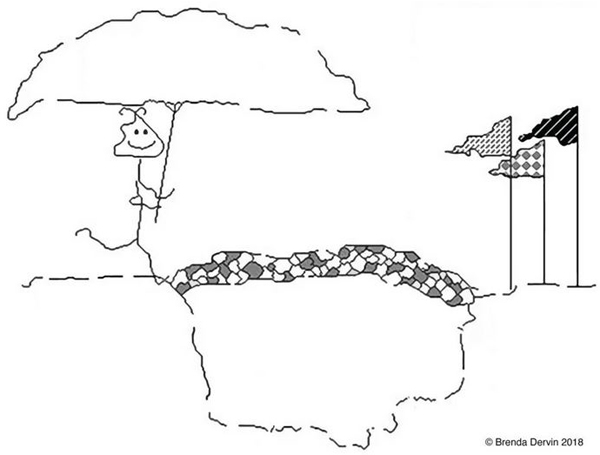

DERVIN and NILAN (1986) defined sense-making as "a set of conceptual and theoretical premises and a set of related methodologies for assessing how people make sense of their worlds and how they use information and other resources in the process" (p.20). They stated that the emphasis of the sense-making metaphor is on movement and where movement is prevented by a gap, a bridge is required to help the individual proceed to an outcome. According to DERVIN (2003), the gap is defined by the individuals rather than from any external measure, and they also decide if and when the gap has been sufficiently bridged. There are various diagrams that illustrate the sense-making metaphor, which have become increasingly complex as the methodology has developed. This is one of the most recent versions of the visual representation of the model:

Figure 1: The sense-making metaphor2) [4]

DERVIN (1999a) pointed out that the sense-making model is based on a set of key metatheoretical assumptions:

Individuals are contextualised by their circumstances and the particular moment in time that the information interaction takes place.

There are gaps between the information and knowledge people have and that which they require to be able to deal with new life situations.

The phenomenon of interest is not on the situation per se, but the individual's capacity to move forward.

There is a focus on actions rather than people, which the author calls verbing.

Individual points in time are contextualised within a person's past, present and future. [5]

Because of the emphasis on discontinuity, experts on sense-making claim that it differs from other types of information behaviour research which assume that information needs are constant (DERVIN, 2003). In an interview with KELLY (2021), DERVIN discussed her life and work and explained that one of the key motivators for sense-making was to create a methodology which makes space for people from marginalised groups to define their own sense-making, rather than to have it defined for them by the structures of power which they are subject to. To my knowledge there has been no discussion of this concept in terms of the sense-making processes of those in a mainstream or majority culture group engaging with the knowledges and cultures of Indigenous or other minoritised groups. [6]

While sense-making has been widely embraced by the fields of communication and library and information studies alike, it is not without its critics. DAVENPORT (2010) pointed out that sense-making's focus on the instance (or individual-in-situation) limits its power in terms of generalisability, despite DERVIN's (2003) claims of a new kind of generalisability. SAVOLAINEN (1993) discussed the cultural situatedness of sense-making, locating it in Anglo-European individual-orientated cultures. Some authors have also highlighted potential issues with the operationalisation of the sense-making metaphor, particularly in relation to the concept of the gap. SAVOLAINEN has suggested that individuals are not always aware of their gaps or able to articulate them, and that perceptions of the extent of a gap may vary depending on whether individuals have an optimistic or pessimistic disposition. GODBOLD (2006) highlighted the possibility that individuals can reduce the size of their gap or ignore it rather than attempting to bridge it. [7]

2.2 Applications of sense-making methodology

Because of the central place of information as a bridging device within the sense-making paradigm, SMM has been broadly applied by authors in the literature related to libraries and other information contexts as a way of understanding user behaviour, and informing the creation of more user-friendly systems. Sense-making, has been used in studies of overt searching behaviour in databases and online (JACOBSON, 1991; SARKAR, MITSUI, LIU & SHAH, 2020; SAVOLAINEN & KARI, 2006), in local government knowledge management processes (CHEUK, 2008), and to investigate how visually impaired people use a public library (CHANG & CHANG, 2010). SMM has also been used to investigate the information behaviour of librarians as well as library users. PERRYMAN (2011) used the sense-making approach alongside WEICK's (1995) theory of sensemaking in organisations to examine the work of hospital librarians in the USA. CHIU (2007) used the sense-making stages of situation, gap, bridge and outcome to investigate the socialisation of new digital librarians in American tertiary libraries. [8]

Sense-making has also found wider utility beyond the realms of library and information studies. A key area of interest has been health, with sense-making being applied to several contexts including breast cancer patient decision-making (GERIDO, 2021), nutrition-related information behaviour of adolescents (BETTS et al., 1989), and with sufferers of chronic illness (BAKER, 1998; NAVEH & BRONSTEIN, 2019). WILLIAMS, NICHOLAS and HUNTINGTON (2003) used SMM to investigate reasons why some patients were not using health information self-service kiosks in a primary care setting in the United Kingdom. [9]

Religion and spirituality have also been key areas for sense-making research, with studies including preachers' processes of making sense of a passage of scripture in order to prepare a sermon (ROLAND, 2007) and Catholic women considering a religious vocation (HICKEY, 2017). DERVIN et al. (2011) described several studies where sense-making has been used to understand spirituality, including a study of how Catholics make sense of situations where real-world scenarios and biblical teachings clashed. CHABOT (2019) noted the Christian focus of sense-making studies of spirituality and conducted a study investigating the information behaviour of New Kadampa Buddhists in Western countries. Other groups that the sense-making approach has been applied to include actors and other theatre professionals (OLSSON, 2010), academics in the process of instructional design (ROTHWELL, 2015), volunteer museum guides (FERRARA, 2017), and participants in virtual worlds (REINHARD & DERVIN, 2012). [10]

There are gaps in the current literature as regards the sense-making processes of non-Indigenous people making sense of Indigenous knowledge—extensive searching revealed little application of sense-making even to cross-cultural engagement in a more general sense. HAY (2000) combined sense-making with ethnography to investigate Arab-American diaspora and their experiences of building cultural community outside their countries of origin. HAY found that community members had different understandings of the term "diaspora", and also that younger members of the community were making concerted efforts to reconnect with their cultures of origin, having experienced a degree of assimilation. ODUNTAN and RUTHVEN (2017) and SMITH (2008) reported on studies of the information behaviour of refugees in Western countries. In a study of female Afghan refugees in San Francisco, SMITH (p.165) explained that the women faced wider "structural" gaps (language barriers and lack of understanding of the American system) alongside the type of gaps which are more commonly observed in sense-making studies, the sense of an immediate information need in a situation, which SMITH (p.159) called "experiential" gaps. ODUNTAN and RUTHVEN (2017) studied a group of refugees and asylum seekers in the UK from various countries. Their findings were in some ways very similar to SMITH's (2008) study, with a number of the gaps described coming under what SMITH categorised as structural gaps relating to UK systems of immigration, law, education and other areas. ODUNTAN and RUTHVEN (2017) found that participants' main means of bridging gaps were interactions with other people, which also echoes SMITH's (2008) findings. PARIYADATH and KLINE (2016) used the micro-moment time line interview format to interview ten individuals (including five Anglo-Americans) about a time when they had overcome a racial stereotype that they had previously held. The authors did not present their findings in the form of the stages of the sense-making metaphor, but as an internal process of individuals realising they held a stereotyped view, recognising this was inconsistent with their experience of the person they are interacting with, and adjusting their worldview to a generalised view that such a stereotype is not representative of people of a certain group. [11]

3. Methodology: Sense-Making Life-Line Interviewing and Focus Groups

In this research I sought to shine a light on how non-Māori librarians in Aotearoa New Zealand make sense of mātauranga Māori [Māori knowledge]. My research approach consisted of interviews with non-Māori librarians and focus groups with Māori librarians. Interviewees were volunteers whom I recruited via email lists and social media. They were twenty-five librarians of different ages, locations, levels of experience and various sub-sectors of librarianship. The majority of librarians identified as New Zealand European (White). I based the interviews on the sense-making life-line interview format. Instead of taking one sense-making instance and breaking it up into small steps, probing the sense-making process for each step (as with the more often described micro-moment time line interview, DERVIN, 1983, 2003), interviewees recall a series of instances across their lifetime in relation to a specific type of experience (FOREMAN-WERNET & DERVIN, 2017), in this case, learning about or engaging with Māori knowledge. I then explored each instance or selected instances with interviewees in detail, using neutral questions. Neutral questions are a type of open questions, addressing the different phases of the sense-making model (DERVIN & DEWDNEY, 1986). I modified the questions from sets provided in DERVIN's methodological writings and previous sense-making studies. [12]

I modified the interview format slightly due to the anticipated amount of time it would potentially take to question all interviewees about every single instance of learning or engagement in relation to Māori knowledge across their lifetime (FOREMAN-WERNET & DERVIN, 2017, stated that these types of interviews normally take place over the course of several days). Instead of discussing every instance given by each interviewee, where more than one or two instances of engagement were given, I invited interviewees to choose which instances they wanted to speak about in more detail (as per the example in DERVIN, 1997). This amounted to between one and three instances per interviewee. [13]

While barriers in the DERVIN sense are viewed as part of the situation (DERVIN, 1983; REINHARD & DERVIN, 2012), and helps are seen as an end point of the sense-making instance whereby the individuals in the situation have bridged their gap and this helps them to move forward (DERVIN, 2003), the kinds of barriers and helps that I was interested in were of a different type. I wanted to know about factors that helped or hindered the gap-bridging itself. DERVIN conceptualised these types of barriers and helps in part as being a part of the bridge, which can be seen more clearly in the later versions of the model (e.g. DERVIN, 2015). Thus I used specific questions to probe this alternative interpretation of helps and barriers. [14]

In addition to interviews with non-Māori librarians, I also undertook three focus groups with Māori librarians, to ask about their experiences with their non-Māori colleagues' engagement or lack of engagement with Māori knowledge. In these focus groups I did not use a sense-making interview format, but some of the questions I asked related to some of the phases of the model. Since interviewees were volunteers and many had taken a particular interest in this topic, focus group participants were able to offer a different perspective, and also to discuss the non-Māori colleagues who were not actively engaging with Māori knowledge, as well as those who were. This exposed some of the limitations of SMM for investigating the issue of non-Māori librarians learning about and engaging with Māori knowledge, as well as painting a fuller picture of the state of the profession in respect to this issue. [15]

4. Limitations of DERVIN's Sense-Making for Investigating Non-Māori Librarians' Learning and Engagement with Māori knowledge

In addressing the question of whether SMM is a suitable approach for investigating how non-Māori librarians learn about or engage with Māori knowledge, there are several factors that lead to the conclusion that it is not the best fit for addressing information behaviour in this particular context. These include the problem of artificial, anticipated or avoided gaps, the difficulty of invisible gaps, differences in interviewees' conceptualisations of their journeys, and the Anglo-American values that are central to the model. [16]

4.1 Artificial and anticipated gaps

The first problem with the sense-making model for this particular research is artificial gaps. In many cases, interviewees had not come across a situation organically where they experienced a knowledge gap. Rather, they had decided to embark on a course of study or attend a professional development event out of general interest rather than immediate need. This resonates with GODBOLD's (2006) assertion that information seeking is not always a response to a gap. In the case of formal study, this was either with the deliberate aim of extending their knowledge of a particular aspect of Māori knowledge (often the Māori language) or undertaking a general course of study where they had incidentally come to be learning about an aspect of Māori knowledge, either because it tied in with an existing interest, or it was a forced choice situation and they thought the Māori option sounded interesting. Twenty-eight sense-making instances out of the fifty-one discussed related to scenarios where interviewees undertook formal learning, with sixteen interviewees speaking about choosing to bridge a gap rather than being stopped in their tracks. This destabilised the model somewhat, by transforming the questions intended to probe the situation (i.e. the lead up to the discovery of the gap) into questions that were probing the bridge instead, because the situation and the bridge could be viewed as the same thing—though in these cases my analysis focussed on what was said about the lead up to engaging in whatever the bridge was for a particular artificial gap. This is to some extent echoed in IRVINE-SMITH's (2010) study where the central focus of problem-solving in the sense-making metaphor was not compatible with types of information behaviour displayed in their study of active and passive participants on an online discussion forum, some of whom did not have a notable gap to bridge or problem to solve. [17]

A similar issue is the anticipated gap, where individuals seek out information or knowledge "just in case" they require it in the future for helping a client. This was seen in the interviews where two interviewees sought information about Māori research methodologies in order to be prepared if any of their clients required any help in that area in the future (neither had been in a situation where they had been asked to provide help and had been unable to do so). Many of the interviewees who had undertaken courses in the Māori language had not done so to address a particular situation where it was required. [18]

These two issues above point to one of the biggest problems in attempting to use DERVIN's sense-making to characterise the information behaviour of non-Māori librarians who are learning about or engaging with Māori knowledge. Where majority culture individuals are immersed in mainstream New Zealand culture, there is rarely an unavoidable need to engage with Māori knowledge and culture as part of their lives and work. While both interviewees and focus group participants acknowledged that times are changing and Māori language and culture are a lot less marginalised than they used to be, it is still quite possible to either deliberately avoid any real meaningful engagement with the Māori world, or remain ignorant of the need to engage. [19]

This is connected to the information behaviour phenomenon of information avoidance. Many of the authors who discuss information avoidance tend to focus on the area of health information, where there is an element of fear (which is interesting, because fear was discussed by interviewees as being a real or potential barrier to engagement). A broader consideration of the phenomenon is HOUSTON's (2009) extensive taxonomy of factors leading to what they called compelled non-use of information (where the decision not to use information was unconscious). HOUSTON highlighted a number of sociocultural factors which are related to privilege, one of which is "lack of capital" (p.124), this refers to social and cultural capital as well as financial capital. Fear of the unknown is a cognitive factor, as is threat of a reduced self-image, both of which are connected to the fear and other negative emotions discussed by interviewees as potential barriers. [20]

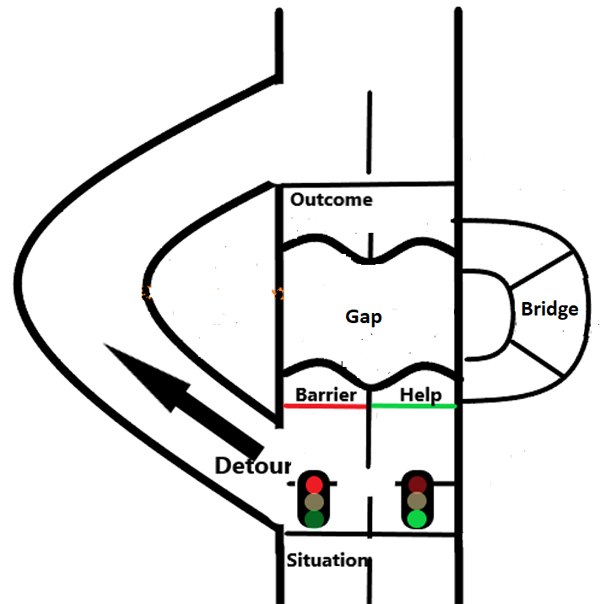

GODBOLD (2006) created a model which incorporates some aspects of sense-making and suggested that individuals can find alternative options to bridging their gaps. They can make the gap smaller by minimising their perception of the importance of the gap, or decide that a gap is too big to bridge. While none of the interviewees talked at length about attempting to avoid addressing particular gaps, some of their comments on their observations of other non-Māori, along with discussions in the focus groups, suggest that there are non-Māori librarians who are in this category. For this reason I am suggesting an addition to the sense-making model: The detour (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Sense-making framework including detour [21]

This signifies where a gap can be encountered but that sense-makers can decide instead to avoid the sense-making opportunity altogether, instead taking a detour around it and carrying on with their journey with no personal or professional disadvantage of doing so. [22]

4.3 When gaps are invisible to the sense-maker

Another issue that means sense-making is not the best approach for the context of non-Māori librarians engaging with Māori knowledge is connected to individuals not always being aware of having gaps in their knowledge, or aware of what those gaps are. This issue was borne out in the interviews in several places where interviewees spoke about how they did not know what they did not know, and how once they started engaging with Māori knowledge, they had this sudden awareness that there was a vast amount that they did not know. This point in some ways reflects the Dunning-Kruger effect (e.g. KRUGER & DUNNING, 1999) where individuals with a low level of skill in a particular area over-estimate their own ability, but once they start to learn, they become more aware of their lack of knowledge and become more accurate at evaluating their own performance. [23]

The sense-making model has no mechanism for addressing invisible gaps or how awareness of such gaps might come about, since the process is focussed on individuals and their perceived needs (DERVIN, 2003). This is consistent with the information behaviour literature more generally, with most authors presenting models which exclude scenarios where information seekers might be unaware of their own information need (SHENTON, 2007, is an exception to this). FORD (2015) stated that unknown gaps should be viewed as beyond the realm of information behaviour: "If a person comes into contact with information of which they are completely unaware and which totally bypasses them, this does not constitute information behaviour on their part" (p.19). Taking a critical librarianship view of this issue might lead to a different conclusion. Examining the structures of privilege which allow some non-Māori librarians to remain unaware of and feel no responsibility for engaging with certain knowledge, leading to the requirement for Māori librarians to do this work on top of their own roles, creating an unethical imbalance of workload, would suggest that this scenario definitely belongs within the realms of information behaviour, perhaps as an extension of HOUSTON's (2009) taxonomy. [24]

A key aspect of this is how interviewees did not have any problems because of what they did not know. This appeared frequently in the data, for twenty interviewees out of 25 in 36 instances out of 51. This points to a societal milieu where the majority New Zealand European system of culture and knowledge is privileged and Māori culture and knowledge continue to be marginalised to a point where it is still possible for non-Māori librarians not to encounter any problems because of the gaps in their knowledge. [25]

A similar issue is partial engagement with the issues: A good example of this is that several interviewees spoke about ways in which engaging with Māori knowledge, and particularly the process of constructing a mihi [speech of greeting, acknowledgement, tribute] including their version of a pepeha [tribal saying, tribal motto], helped non-Māori to feel more connected, either to Aotearoa New Zealand or to their own ancestral lands. None of these interviewees, however, spoke explicitly about the differences between their own version of a pepeha and the special whakapapa [genealogy, genealogical table, lineage, descent] significance for Māori that connects them to the atua [ancestor(s) with continuing influence, god(s)]:

"The relationship of Māori with the land

The importance of the land and the environment was reflected through whakapapa, ancestral place names and tribal histories. The regard with which Māori held land was a reflection of the close relationship that Māori had with the kāwai3) tīpuna4). The children of Ranginui5) and Papatūānuku6) were the parents of all resources: the patrons of all things tapu7). As the descendants of Ranginui and Papatūānuku and the kāwai tīpuna, Māori maintained a continuing relationship with the land, environment, people, kāwai tīpuna, tīpuna and spirits... The land is a source of identity for Māori. Being direct descendants of Papatūānuku, Māori see themselves as not only 'of the land', but 'as the land'" (MINISTRY OF JUSTICE, 2001, p.44). [26]

In this case, depth of knowledge determines the application of these concepts. The fact that focus group participants did not talk about pepeha in those terms as a help for non-Māori can also be seen as highlighting this gap. A similar unnamed gap is that the majority of interviewees spoke about Māori knowledge in a pan-Māori sense, with few acknowledging the differences in knowledge and practices between tribes, sub-tribes and extended families that experts have highlighted in the literature (DOHERTY, 2012, 2014; PROCTER & BLACK, 2014; SMITH, 1996). [27]

4.4 Interviewees conceptualise their journeys differently from sense-making

The next issue is connected to the way that interviewees conceptualised their journeys of learning about or engaging with Māori knowledge, which is in some ways connected to the ways that Indigenous knowledges differ from the often-linear nature of Western knowledge. Some interviewees found the idea of dividing up their journey into instances of learning or engagement a difficult one to understand, and some excluded what I might have expected to be key details about their journeys from their timelines. Others found the process of talking about their journey acted as a memory-jogger for them and they found themselves remembering other anecdotes and discussing them in depth during the time when we were supposed to be probing another instance, either diverting away from the original instance completely, or telling a story within a story and then returning to the original instance. Some interviewees were expecting to discuss their day-to-day work with Māori clients or knowledge and expressed frustration at the format of the questions. [28]

4.5 The linearity of the model

Interviewee 22: "I'm sorry, I'm all over the show. You'll have to really unpick [my answers]."

"... when Pākehā8) experience te ao Māori9) at various times in their lives, in various locations and in various contexts, they learn from their cumulative experiences and thus, become more postcolonial in their thinking about them" (BROWN, 2011, p.98).

Interviewees quite often viewed the trajectory of their journeys in different ways to the process outlined by sense-making. Not all interviewees saw or were able to describe their journey as being a discrete set of steps or events that led forward to particular outcomes. For some it was more of a holistic process, and small incremental incidents merged together, or in some cases a critical mass of small learnings developed into something bigger but the individual did not see them as separate from one another. This manifested as either finding it difficult to focus on talking about a particular instance or finding it difficult to answer the questions as asked, rather just continuing on with their own train of thought. BAKER (1998) experienced a similar phenomenon in their interviews with individuals with Multiple Sclerosis, who, when being interviewed about a particular flare up of the disease, in some cases brought in experiences from other flare ups as well. [29]

Along similar lines, there were several examples of interviewees talking about co-occurring instances. This happened in one of two ways. Firstly, some interviewees talked about single instances with multiple facets, e.g. starting a job with a Māori component alongside learning the Māori language. Secondly, there were interviewees who described as separate instances events or learnings that were closely connected to each other. Where such interviewees gave a short list of instances, discussing two that were related led to some repetitiveness in the discussions. This is perhaps unsurprising considering the holistic nature of Māori knowledge discussed briefly above, and the enormity of the task of engaging with an entire new knowledge system, meaning that various learnings are quite likely to come together in this way. These issues arise due to the linear nature of the life-line interview format with its focus on discrete sense-making instances which can cause problems when dealing with wide-reaching holistic knowledge systems such as Māori knowledge. Indigenous scholars such as HENDERSON (2000) and WILSON (2008) have emphasised that Indigenous knowledges and worldviews are more circular than linear. [30]

Such examples demonstrated how being an experienced interviewer, and particularly having the opportunity to be trained in sense-making interviewing, could have been beneficial. This was emphasised as important by DERVIN (1983, 2003) who also stated that interviewees need to receive some training in SMM methods prior to being interviewed, which did not occur in this case. DERVIN and REINHARD (2007) explained that this kind of training can help interviewers know how to redirect interviewees when they have strayed away from discussing a particular instance. [31]

4.6 DERVIN's sense-making approach influenced by a Western perspective

As SAVOLAINEN (1993) pointed out, sense-making is strongly reflective of mainstream American culture:

"In Dervin's theory, the basic values of American culture are interestingly reflected: the central position of individual actor, the importance of making things happen and moving forward, in spite of barriers faced, and relying on individual capacities in problem solving. ... There are no eternal standards for doing things; they are continually created and their validity contested. Thus instruments and institutions should be bent to individual needs and not the other way round" (p.26). [32]

GROSS (2023) went further, tracing the roots of sense-making to the epic poems of HOMER in Ancient Greece and thus the very beginnings of Western civilisation. While sense-making has been successfully used in other Anglo-European contexts to study information behaviour (e.g. OLSSON, 2010) and even in some studies in Aotearoa New Zealand (BENNETT, 2010; JULIEN & MICHELS, 2000; TEEKMAN, 1999), in retrospect it appears that it is not the most effective model for use in this particular scenario at the interface between Māori knowledge and non-Māori librarians. [33]

To DERVIN, one of the important factors of sense-making was that it enabled marginalised individuals to address both their own agency and the structures of oppression that they lived within, acknowledging the role of both aspects in the sense-making process (KELLY, 2021). This appears to have been used powerfully in studies of Indigenous or other minoritised community members (e.g. HAY, 2000; ODUNTAN & RUTHVEN, 2017; SMITH, 2008), but the model is not able to address the power dynamics of majority culture individuals attempting to engage with the knowledges of Indigenous or other minoritised communities. DERVIN stated in her interview with KELLY (2021) that "If you've been controlled by structure, and we all have, you never forget it" (p.197). This is less true for those of us in a majority culture group who have been controlled by structures that maintain our own comfort and privilege. Majority culture individuals are often unaware of these structures unless they have begun a process of decolonisation. The sense-making model takes the same view as FORD (2015), that is, that knowledge which a person is not aware of can pass them by and not be considered as information behaviour. Thus SMM is not designed to address gaps that are defined by the Indigenous or minoritised group concerned rather than the individual sense-maker, which is why artificial, anticipated, avoided and invisible gaps create problems for sense-making. [34]

Another difficulty with the cultural viewpoint of DERVIN's sense-making, as alluded to above, is that decisions as to whether gaps need to be bridged, how and when they should be bridged, and when a satisfactory outcome has been reached, are all determined by the individual sense-maker. This is problematic in the scenario under consideration, where historically and on an ongoing basis, Māori and other Indigenous peoples have been harmed by the mishandling of their knowledge by Western majority culture members in various ways (SMITH, 2012). This is connected to the issue of non-Māori influence as highlighted in the focus groups. Focus groups talked about how non-Māori could approach Māori knowledge in ways that reflect their non-Māori cultural mindset, and thus are not representing a fully culturally competent approach. Non-Māori interviewees largely did not raise this issue. It is another area of lack of awareness of a gap, and one which causes a potential risk to Māori customers or colleagues. Thus, within the sense-making framework non-Māori librarians might judge a gap to have been bridged, but in reality there are still gaps in their knowledge that have the potential to cause problems, thus cultural differences persist. [35]

There were a few examples of this in the interviews. An important part of engaging with Māori knowledge, highlighted by the focus groups, is having a level of humility or sensitivity around how Māori knowledge is to be approached and engaged with. One interviewee explained that an outcome of their engagement was that they were able to be more "vociferous" in discussions with a Māori colleague, which indicates that they may still have more to learn in this area. [36]

5. Application of sense-making methodology in my study

While I have given a comprehensive critique of SMM as applied to the process of non-Māori librarians learning about and engaging with Māori knowledge, it is important to note that although it was used as a guiding framework for this research, sense-making has not been applied in its purest sense. This is not uncommon in the literature, with researchers often employing sense-making among a number of theoretical frameworks (e.g. LUND & MA, 2022; OLSSON, 2010; PERRYMAN, 2011), or using different methods of analysis than the content analysis traditionally associated with communication studies methods. PARIYADATH and KLINE (2016) used grounded theory to analyse micro-moment time line interviews on how individuals worked through their personal prejudices, and presented the findings in a format that was not directly reflective of the sense-making metaphor. I am inclined to think that a stricter adherence to the methodology would not have significantly served to circumvent the most challenging of these issues, although training for myself and for the interviewees may have mitigated some of the more practical difficulties I encountered to a certain extent. [37]

In this paper, I have discussed the application of DERVIN's sense-making methodology in a study of non-Māori librarians learning about and engaging with Māori knowledge in Aotearoa New Zealand, and some of the difficulties presented by this approach for this context. DERVIN (1983, 1998) stated that the sense-making metaphor's core stages of situation, gap, bridge and outcome are universals of the human condition, and SMM was designed to account for issues of power and their impacts on the individual sense-maker within its central metaphor (DERVIN, 1999b; SAVOLAINEN, 2006). However, the power of the majority culture and its subsequent marginalisation of—and optionalisation of engagement with—Māori knowledge in the New Zealand environment are problematic for SMM. This is due to problems such as artificial, anticipated, avoided and fully or partially invisible gaps. The ability of the individual sense-maker to decide when a gap is bridged is also problematic when considering concerns of misuse of Indigenous knowledge, such as cultural appropriation. This study is the first to report such findings to my knowledge, with cross-cultural sense-making studies focussed largely on the sense-making processes of individuals in the position of being from a minoritised population, and thus with tangible knowledge gaps (HAY, 2000; ODUNTAN & RUTHVEN, 2017; SMITH, 2008). Future research may look to interrogate other sense-making and information behaviour models to discover whether they create similar challenges for majority populations engaging with Indigenous or other minoritised cultures and knowledges, and look to extend this work by creating a model that can fully incorporate the challenges discussed above in a way that SMM is not currently able to do. [38]

I would like to thank all participants in the PhD research on which this paper is based. Many thanks to my supervisors, professor Anne GOULDING and associate professor Spencer LILLEY at Te Herenga Waka, Victoria University of Wellington.

The first draft of this paper was written during a secondment to Te Manawahoukura, the research centre at Te Wānanga o Aotearoa, I am thankful for the opportunity this gave me to begin the publication journey. Special thanks go to Tara McALLISTER for your mentorship and guidance. I would also like to thank Jenny BARNETT at Te Pātaka Māramatanga, Library at Te Wānanga o Aotearoa for creating space for me to undertake the secondment.

1) All definitions are taken from http://maoridictionary.co.nz/ unless otherwise specified [Accessed: February 6, 2025]. <back>

2) Copyright: Sense-Making Methodology Institute, used with permission, https://sense-making.org/ [Accessed: November 1, 2024]. <back>

3) Line of descent, lineage, pedigree. <back>

4) Ancestors, grandparents; plural form of tipuna and the eastern dialect variation of tūpuna. <back>

5) Atua of the sky and husband of Papa-tū-ā-nuku, from which union originate all living things. <back>

6) Earth, Earth mother and wife of Rangi-nui, all living things originate from them. <back>

7) Sacred. <back>

8) New Zealander of European descent <back>

9) The Māori world (definition from TE HUIA, 2016, p.746) <back>

Baker, Lynda (1998). Sense making in multiple sclerosis: The information needs of people during an acute exacerbation. Qualitative Health Research, 8(1), 106-120.

Bennett, Lauren (2010). The New Zealand seasonal influenza immunization campaign and sense-making methodology: How library and information studies can inform government-citizen communication. Dissertation, School of Information Management, Victoria University of Wellington, Wellington, New Zealand.

Betts, Nancy; Pingree, Suzanne; Amos, Rosalie; Ashbrook, Sheila; Fox, Hazel; Newell, Kathleen; Ries, Carol; Terry, Dale; Tinsley, Ann & Voichick, Jane (1989). The sense-making approach for audience assessment of adolescents. Adolescence, 24(94), 393-402.

Brown, Micheal (2011). Decolonising Pākehā ways of being: Revealing third space Pākehā experiences. Dissertation, School of Education, University of Waikato, Hamilton, New Zealand, https://researchcommons.waikato.ac.nz/entities/publication/2f228bd3-de47-4fb5-b549-12bd7c4c7a35 [Accessed: November 1, 2024].

Chabot, Roger (2019). The information practices of New Kadampa Buddhists: From "Dharma of scripture" to "Dharma of insight". Dissertation, Faculty of Information & Media Studies, University of Western Ontario, London, Ontario, Canada, https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/6099 [Accessed: November 1, 2024].

Chang, Po-Ya & Chang, Shan-Ju Lin (2010). National Taiwan library services for visually impaired people: A study using sense-making approach. Journal of Educational Media & Library Sciences, 47(3), 283-318.

Cheuk, Bonnie Wai-Yi (2008). Applying sense-making methodology to design knowledge management practices. International Journal of Knowledge Management, 4(3), 33-43.

Chiu, Ming-Hsin (2007). Making sense of organizational socialization: Exploring information seeking behavior of newcomer digital librarians in academic libraries. Dissertation, The Information School, University of Wisconsin, Madison, Wisconsin, USA.

Davenport, Elisabeth (2010). Confessional methods and everyday life information seeking. Annual Review of Information Science and Technology, 44(1), 533-562.

Dervin, Brenda (1983). An overview of sense-making research: Concepts, methods, and results to date. Paper presented at the International Communication Association Annual Meeting, Dallas, TX, USA, May 1983, https://sense-making.org/docs/conf-workshop/1983-dervin-smm-intro-ica.pdf [Accessed: November 1, 2024].

Dervin, Brenda (1997). Observing, being victimized by, and colluding with isms (sexism, racism, able-bodyism): Sense-making interviews from a university advanced level class in interviewing. Webpage, Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA, https://web.archive.org/web/20120629032749/http://communication.sbs.ohio-state.edu/sense-making/inst/idervin97isms.html [Accessed: November 1, 2024].

Dervin, Brenda (1998). Sense-making theory and practice: An overview of user interests in knowledge seeking and use. Journal of Knowledge Management, 2(2), 36-46.

Dervin, Brenda (1999a). On studying information seeking methodologically: The implications of connecting metatheory to method. Information Processing and Management, 35(6), 727-750.

Dervin, Brenda (1999b). Chaos, order, and sense-making: A proposed theory for information design. In Robert Jacobson (Ed.), Information design (pp.35-58). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Dervin, Brenda (2003). From the mind's eye of the user: The sense-making qualitative-quantitative methodology. In Brenda Dervin, Lois Foreman-Wernet & Eric Lauterbach (Eds.), Sense-making methodology reader: Selected writings of Brenda Dervin (pp.269-292). Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press.

Dervin, Brenda (2015). Dervin's sense-making theory. In Mohammed Nasser Al-Suqri & Ali Saif Al-Aufi (Eds.), Information seeking behavior and technology adoption: Theories and trends (pp.59-80). Hershey, PA: IGI Global.

Dervin, Brenda & Dewdney, Patricia (1986). Neutral questioning: A new approach to the reference interview. RQ: Reference Quarterly, 25(4), 506-513.

Dervin, Brenda & Nilan, Michael (1986). Information needs and uses. In Martha Williams (Ed.), Annual review of information science and technology (Vol. 21, pp.3-33). White Plains, NY: Knowledge Industry Publications.

Dervin, Brenda & Reinhard, CarrieLynn (2007). How emotional dimensions of situated information seeking relate to use evaluations of help from sources: An exemplar study informed by sense-making methodology. In Diane Nahl & Dania Bilal (Eds.), Information and emotion: The emergent affective paradigm in information behavior research and theory (pp.51-84). Medford, NJ: Information Today.

Dervin, Brenda; Clark, Kathleen; Coco, Angela; Foreman-Wernet, Lois; Rajendram, Christlin & Reinhard, CarrieLynn (2011). Sense-making as methodology for spirituality theory, praxis, pedagogy, and research. Paper, First Global Conference on Spirituality in the 21st Century, Prague, Czech Republic, March 20-22, 2011, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/259742554_Sense-Making_as_methodology_for_spirituality_theory_praxis_pedagogy_and_research [Accessed: February 6, 2025].

Doherty, Wiremu (2012). Ranga framework—He raranga kaupapa. In Haemata Limited (Ed.), Conversations on mātauranga Māori (pp.15-36). Wellington: New Zealand Qualifications Authority.

Doherty, Wiremu (2014). Mātauranga ā-iwi as it applies to Tūhoe: Te mātauranga o Tūhoe [Tribal knowledge as it applies to the Tūhoe tribe. The knowledge of the Tūhoe tribe]. In Hineihaea Murphy, Carol Buchanan, Whitney Nuku & Ben Ngaia (Eds.), Enhancing mātauranga Māori and global Indigenous knowledge (pp.29-46). Wellington: New Zealand Qualifications Authority.

Durie, Mason (1997). Identity, access and Māori advancement. In Noble Thomson Curtis, Jo Howse, & Laurie McLeod (Eds.), New Zealand Educational Administration Society research conference. New directions in educational leadership: The Indigenous future (pp.1-15). Auckland: New Zealand Educational Administration Society and Auckland Institute of Technology.

Ferrara, Stephanie (2017). The information practice of volunteer guides at the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia. Information Research, 22(4), 1612, http://informationr.net/ir/22-4/rails/rails1612.html [Accessed: November 1, 2024].

Ford, Nigel (2015). Introduction to information behaviour. London: Facet.

Foreman-Wernet, Lois & Dervin, Brenda (2017). Hidden depths and everyday secrets: How audience sense-making can inform arts policy and practice. Journal of Arts Management Law and Society, 47(1), 47-63.

Gerido, Lynette (2021). The unequal burden of breast cancer: An exploration of information behaviors and racial disparities in genomic screening decisions. Dissertation, College of Communication and Information, Florida State University, Tallahassee, Florida, USA.

Godbold, Natalya (2006). Beyond information seeking: Towards a general model of information behaviour. Information Research, 11(4), Art. 269, http://informationr.net/ir/11-4/paper269.html [Accessed: November 1, 2024].

Gross, Margaret (2023). How didst thou come beneath the murky darkness?: Sense-making in light of the ancient Greeks and in the spirit of Hegel. Journal of Documentation, 79(6), 1369-1379.

Hay, Kellie (2000). Immigrants, citizens and diasporas: Enacting identities in an Arab-American cultural organization. Dissertation, The Graduate School, Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio, USA, http://rave.ohiolink.edu/etdc/view?acc_num=osu1391700209 [Accessed: November 1, 2024].

Henderson, James Sákéj Youngblood (2000). Ayukpachi: Empowering Aboriginal thought. In Marie Battiste (Ed.), Reclaiming Indigenous voice and vision (pp.248-278). Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press.

Hickey, Katherine (2017). The information behavior of Catholic women discerning a vocation to religious life. Journal of Religious & Theological Information, 16(1), 2-21.

Houston, Ronald (2009). A model of compelled nonuse of information. Dissertation, The Graduate School, University of Texas, Austin, Texas, USA, https://repositories.lib.utexas.edu/handle/2152/6896 [Accessed: November 1, 2024].

Irvine-Smith, Sally (2010). A series of encounters: The information behaviour of participants in a subject-based electronic discussion list. Journal of Information & Knowledge Management, 9(3), 183-201.

Jacobson, Thomas (1991). Sense-making in a database environment. Information Processing and Management, 27(6), 647-657.

Julien, Heidi & Michels, David (2000). Source selection among information seekers: Ideals and realities. Canadian Journal of Information & Library Sciences, 25(1), 1-18, https://journals.library.ualberta.ca/ojs.cais-acsi.ca/index.php/cais-asci/article/view/16 [Accessed February 6, 2025]

Kelly, Matthew (2021). An interview with professor emeritus Brenda Dervin. The Information Society, 37(3), 190-198.

Kruger, Justin & Dunning, David (1999). Unskilled and unaware of it: How difficulties in recognizing one's own incompetence lead to inflated self-assessments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77(6), 1121-1134.

Lund, Brady & Ma, Jinxuan (2022). Exploring information seeking of rural older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. Aslib Journal of Information Management, 74(1), 54-77.

Mead, Hirini Moko (2012). Understanding mātauranga Māori. In Haemata Limited (Ed.), Conversations on mātauranga Māori (pp.9-14). Wellington: New Zealand Qualifications Authority.

Mead, Hirini Moko (2016). Tikanga Māori: Living by Māori values (2nd ed.). Wellington: Huia.

Ministry of Justice (2001). He hīnātore ki te ao Māori a glimpse into the Māori world: Māori perspectives on justice. Wellington: Ministry of Justice.

Moorfield, John (2011). Te Aka, Māori-English, English-Māori dictionary and index (3rd ed.). Auckland: Pearson.

Naveh, Sharon & Bronstein, Jenny (2019). Sense making in complex health situations: Virtual health communities as sources of information and emotional support. Aslib Journal of Information Management, 71(6), 789-805.

Oduntan, Olubukola Olajumoke & Ruthven, Ian (2017). Investigating the information gaps in refugee integration. Proceedings of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 54(1), 308-317.

Olsson, Michael (2010). All the world's a stage—the information practices and sense-making of theatre professionals. Libri, 60(3), 241-252.

Oxborrow, Kathryn (2020). "It’s not just a professional development thing": Non-Māori librarians in Aotearoa New Zealand making sense of mātauranga Māori. Dissertation, School of Information Management, Te Herenga Waka | Victoria University of Wellington, Wellington, Aotearoa New Zealand, https://openaccess.wgtn.ac.nz/articles/thesis/_It_s_not_just_a_professional_development_thing_Non-M_ori_librarians_in_Aotearoa_New_Zealand_making_sense_of_m_tauranga_M_ori_/17148506/1 [Accessed: February 14, 2025].

Pariyadath, Renu & Kline, Susan (2016). Bridging difference: A sense-making study of the role of communication in stereotype change. In Sakilé Camara & Darlene Drummond (Eds.), Communicating prejudice: An appreciative inquiry approach (pp.1-26). Hauppage, New York: Nova Science.

Perryman, Carol (2011). The sense-making practices of hospital librarians. Dissertation, School of Information and Library Science, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, USA, https://cdr.lib.unc.edu/concern/dissertations/jd472w748 [Accessed: November 1, 2024].

Procter, Jonathan & Black, Hona (2014). Mātauranga ā-iwi—He haerenga mōrearea [Tribal knowledge—a hazardous journey]. In Hineihaea Murphy, Carol Buchanan, Whitney Nuku & Ben Ngaia (Eds.), Enhancing mātauranga Māori and global Indigenous knowledge (pp.87-100). Wellington: New Zealand Qualifications Authority.

Reinhard, CarrieLynn & Dervin, Brenda (2012). Comparing situated sense-making processes in virtual worlds: Application of Dervin's sense-making methodology to media reception situations. Convergence, 18(1), 27-48.

Roland, Daniel (2007). Interpreting scripture in contemporary times: A study of a clergy member's sense-making behavior in preparing the Sunday sermon. Dissertation, School of Library & Information Management, Emporia State University, Emporia, Kansas, USA, https://esirc.emporia.edu/handle/123456789/3349 [Accessed: November 1, 2024].

Rothwell, Susan (2015). Question-asking behavior of faculty during conceptual instructional design: A step toward demystifying the magic of design. Dissertation, information studies, School of Information Studies, Syracuse University, Syracuse, New York, USA, https://surface.syr.edu/etd/234/ [Accessed: March 2, 2025].

Sarkar, Shawon; Mitsui, Matthew; Liu, Jiqun & Shah, Chirag (2020). Implicit information need as explicit problems, help, and behavioral signals. Information Processing & Management, 57(2), 102069.

Savolainen, Reijo (1993). The sense-making theory: Reviewing the interests of a user-centered approach to information seeking and use. Information Processing and Management, 29(1), 13-28.

Savolainen, Reijo (2006). Information use as gap-bridging: The viewpoint of sense-making methodology. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 57(8), 1116-1125.

Savolainen, Reijo & Kari, Jarkko (2006). Facing and bridging gaps in Web searching. Information Processing and Management, 42(2), 519-537

Shenton, Andrew (2007). Viewing information needs through a Johari window. Reference Services Review, 35(3), 487-496.

Smith, Linda Tuhiwai (1996). Kaupapa Māori research—Some kaupapa Māori principles. In Leonie Pihama, Sarah-Jane Tiakiwai & Kim Southey (Eds.), Kaupapa rangahau: A reader (pp.47-54). Hamilton: University of Waikato.

Smith, Linda Tuhiwai (2012). Decolonizing methodologies: Research and Indigenous peoples (2nd ed.). London: Zed Books.

Smith, Valerie (2008). The information needs and associated communicative behaviors of female Afghan refugees in the San Francisco Bay Area. Dissertation, School of Communication and the Arts, Regent University, Virginia Beach, Virginia, USA, https://scholarworks.calstate.edu/concern/theses/kh04dq72t?locale=en [Accessed: November 1, 2024].

Te Huia, Awanui (2016). Pākehā learners of Māori language responding to racism directed toward Māori. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 47(5), 734-750.

Teekman, Bert (1999). A sense-making examination of reflective thinking in nursing practice. Electronic Journal of Communication/La Revue Électronique de Communication, 9(2/3/4), http://www.cios.org/ejcpublic/009/2/009210.html [Accessed: November 1, 2024].

Waitangi Tribunal (2011). Ko Aotearoa tēnei: Te taumata tuatahi [This is Aotearoa: Level one]. Waitangi Tribunal Reports, WAI262, https://forms.justice.govt.nz/search/Documents/WT/wt_DOC_68356054/KoAotearoaTeneiTT1W.pdf [Accessed: November 1, 2024].

Weick, Karl (1995). Sensemaking in organizations. London: Sage.

Williams, Peter; Nicholas, David & Huntington, Paul (2003). Non use of health information kiosks examined in an information needs context. Health Information and Libraries Journal, 20(2), 95-103, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1046/j.1471-1842.2003.00428.x [Accessed: February 6 2025].

Wilson, Shawn (2008). Research is ceremony: Indigenous research methods. Black Point: Fernwood.

Kathryn OXBORROW VAMBE, PhD, is a librarian and researcher. Originally from the UK, she has been based in Aotearoa New Zealand since 2010. In her PhD research, she focussed on how non-Māori librarians learn about and engage with Māori knowledge and she now gets to live out her learnings every day as a Senior Librarian at Te Wānanga o Aotearoa, a Māori-led tertiary institution.

Contact:

Kathryn Oxborrow Vambe

Te Wānanga o Aotearoa

Te Pātaka Māramatanga – Library

5 Heriot Drive, Porirua, Wellington 5022, Aotearoa New Zealand

E-mail: Kathryn.OxborrowVambe@twoa.ac.nz

Oxborrow Vambe, Kathryn (2025). When sense-making doesn't make sense: Dervin's sense-making methodology applied to the question of non-Māori librarians in New Zealand making sense of Māori knowledge [38 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 26(2), Art. 4, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-26.2.4309.