Volume 26, No. 2, Art. 11 – May 2025

Inviting Engagement With Climate Change Education Research: An Arts-Based Knowledge Translation Approach

Tiina Kukkonen, Heather E. McGregor, Micah Flavin & Amanda Cooper

Abstract: Arts-based knowledge translation (ABKT) leverages the arts to communicate research knowledge to target audiences with the aim of deepening empathy, sparking dialogue, and inspiring research-informed policy and action within diverse research contexts. In the project we describe here, the development of an art exhibit, ABKT activities supported by an artist-researcher collaboration were used to engage a variety of education audiences with climate change. Utilizing KUKKONEN and COOPER's (2019) interdisciplinary four-phase planning framework to illuminate the outcomes of the art exhibit, this article helps to show ABKT in action. We make the framework tangible for researchers interested in arts-based approaches and share what we learned about applying ABKT to engage audiences with research in the area of climate change and ecojustice education. We conclude with suggestions for building artist-researcher partnerships and embracing playfulness in ABKT.

Key words: arts-based knowledge translation; knowledge mobilization; knowledge translation; arts-based methods; artist-researcher partnerships; arts-based co-production; climate change education

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. Project Background

3. ABKT Framework in Action

3.1 Identifying goals in relation to target audiences (Phase 1)

3.2 Selecting appropriate art genres and mediums (Phase 2)

3.3 Building partnerships to strengthen the ABKT initiative (Phase 3)

3.4 Planning methods for disseminating and tracing impact (Phase 4)

4. Learning from the ABKT Planning Framework in Action

4.1 Artist-researcher partnership-building

4.2 Adopting playful processes

5. Conclusion

What happens when artists and researchers work together to explore complex issues and disseminate research findings? This question is currently at the forefront of numerous research initiatives spanning diverse disciplines and geographic locations, such as, e.g., Art + Research at the University of Stockholm (Sweden), Artist-Researcher Collaborations at the University of Warwick (United Kingdom), the ReVision Centre for Art and Social Justice at the University of Guelph (Canada). Researchers across fields of study are increasingly seeking out artist collaborations to "expand creative practices in research" (CHAPPELL & MUGLIA, 2023, p.2), "engage and educate the general public" (GEWIN, 2021, p.515), and promote "democratized space[s]" (BOYDELL, 2020, p.77) for dialogue and knowledge co-production among artists, researchers, and communities. In this paper, we highlight one such artist-researcher collaboration that took place at a Canadian university in 2023. We, the artist-researcher team, utilize KUKKONEN and COOPER's (2019) arts-based knowledge translation (ABKT) planning framework to structure and inform our description of a co-produced art exhibition aimed at increasing engagement with research in climate change and ecojustice education. [1]

ABKT is a form of knowledge translation—also known as knowledge mobilization—which plays a crucial role in optimizing the uptake and impact of publicly funded research (COOPER, RODWAY & READ, 2018; NUTLEY, WALTER & DAVIES, 2007). It is "the process of using artistic approaches to communicate research findings" (KUKKONEN & COOPER, 2019, p.293), with the aim of making research knowledge appealing and understandable to target audiences. In recent years, researchers applying ABKT have demonstrated its potential to enhance stakeholder engagement and tap into ways of knowing that depart from conventional scholarly forms (BOYDELL, GLADSTONE, VOLPE, ALLEMANG & STASIULIS, 2012; COOPER, SEARLE, MacGREGOR & KUKKONEN, 2023; WILLIAMS, TAVARES, EGLI, MOEKE-MAXWELL & GOTT, 2023). Researchers in health, for instance, have explored the use of illustrated storybooks to communicate health-related information to children and/or caregivers (e.g., GERDNER, 2008; MUTAMBO, SHUMBA & HLONGWANA, 2021; SCOTT, HARTLING, O'LEARY, ARCHIBALD & KLASSEN, 2012). ARCHIBALD and SCOTT (2019) contended that artistic formats (e.g., storybooks, plays, songs, films, etc.) elicit emotional responses from intended audiences that "evoke different and deeper understanding" (p.1623) of the research knowledge. Thus, the power of the arts can be leveraged to deepen empathy, spark dialogue, and inspire policy and action within different research contexts (MILLER, 2024). [2]

To assist researchers in their arts-based efforts, KUKKONEN and COOPER (2019) developed a planning framework that can be applied across disciplines. The framework includes four key phases: 1. identify goals in relation to target audiences; 2. select appropriate art genre(s) and medium(s) for disseminating the research; 3. build partnerships with artists and other community members to strengthen the process and outcomes of the ABKT initiative; 4. plan methods for disseminating and tracing the impact of ABKT processes and products on target audiences (ibid.). While the four phases emerged from an analysis of cross-sector ABKT strategies, practical applications of the framework are lacking in the literature to date. In this article, we therefore aim to demonstrate the planning framework in action by using the four phases to structure our description of an art exhibition involving an artist-researcher collaboration. We make the framework more tangible for researchers and highlight what we, the artist-researcher team, learned about how ABKT engages audiences with research in climate change and ecojustice education—an area where diverse ways of mobilizing knowledge are needed to address the complexity of the climate change crisis with learners of all ages (GUNSON, MURPHY & BROWN, 2021). [3]

We begin with background information about the project (Section 2), followed by a description of our project actions organized according to the four phases of the ABKT framework (Section 3). Then, we present what we learned as researchers seeking to implement ABKT practices with artist partners (Section 4) and offer our concluding thoughts (Section 5). [4]

Our art exhibition emerged from a pilot initiative promoting knowledge mobilization by researchers in the Faculty of Education at Queen's University in Kingston, Ontario, Canada, initiated by the Associate Dean of Research, Amanda COOPER (Author 4). Collaborations between artists and researchers were funded to create innovative research experiences, products, and engagement strategies with students, faculty members, and researchers to broaden the reach and significance of social-impact research. Tiina KUKKONEN (Author 1)—a visual artist, arts educator, and arts-based researcher—was commissioned as the artist for the project. The Social Studies and History Education in the Anthropocene Network (SSHEAN) research group, including principal investigator Heather E. McGREGOR (Author 2), and Micah FLAVIN (Author 3) was then selected to work with Tiina to develop an ABKT project that would align with the goals of its research, namely, exploring inviting approaches to climate change and ecojustice education. As a starting point for this project, Heather crafted the following statement describing the foundations of SSHEAN's work, which is posted on their website:

"Our research asks how to invite and support social studies and history teachers to contribute more to climate change and ecojustice education, and what benefits this could offer for learners. Studies on the prevalence of ecoanxiety demonstrate that doom-and-gloom, fact-heavy approaches to teaching climate change in any subject area are not meeting the needs of learners, including prospective teachers (Chawla, 2020). Beyond the science of ecosystem changes, this topic of study increasingly requires sitting with deeply disturbing implications such as complicity with environmental racism (Cachelin & Nicolosi, 2022), the disproportionate effects of pollution and negative environmental impacts on racialized peoples. Attending to the emotions associated with learning about complex and intersecting crises is necessary to teach effectively, whether from a science, literacy, or historical perspective (Pihkala, 2020). This can be done by emphasizing solutions, actions, informed hopefulness, solidarity in community, and meaningful change–engaging examples of which can be found through history, civics, geography, and social studies inquiries. The arts are also well-positioned for this work, as they promote the types of imaginative, affective, and metaphorical ways of thinking and being that are needed to inspire transformation in the face of a highly uncertain future (Bentz, 2020).

We have realized that further research into these questions necessitates tools and strategies to overcome objections to climate change study from prospective learners (including teachers), such as, but not limited to, attachment to familiar curriculum, subject area silos, barriers to outdoor learning, and activities perceived as political. Thus, we are motivated to identify openings, invitations, and pathways that serve to engage the audiences for our research and pedagogical offerings in a willingness to change. We suspect this willingness to change is characterized as much by tracing new directions in which to grow (a planting of sorts), as by tracing old directions which must be left behind to decay (a composting of sorts). We maintain that an individual willingness to change, as a precursor to learning more about climate and participating in urgent climate action, depends on a recognition of our interrelatedness with other species, and a meaningful, personal narrative about the place of one's life in the connection between the past, present, and the future. That is, it depends on an evolving historical consciousness and sense of empathy." [5]

With these ideas in mind, we (the artist-researcher team) embarked on this project to explore how the arts might promote awareness of and engagement with research in climate change and ecojustice education. We exhibited the resulting products and artworks described in this article in the Faculty of Education gallery space in October 2023. In Figure 1 we provide a timeline of events associated with the project, starting with the initial planning meeting in January 2023 and ending with the most recent presentation of the project at a conference in June 2024. We use KUKKONEN and COOPER's (2019) planning framework to structure and inform our understanding of how our research, teaching, and artmaking actions mobilized knowledge in ways that fulfilled and exceeded our planning.

Figure 1: Timeline of events associated with the Change with the Earth in Mind project and art exhibition, from initial planning meeting to conference presentations. Please click here or on the figure for an enlarged version of Figure 1. [6]

3.1 Identifying goals in relation to target audiences (Phase 1)

The success of knowledge translation efforts can be supported from the outset by setting clear goals that take into consideration the target audiences for the work (COOPER, 2014). Drawing on the work of COOPER, the authors of the ABKT planning framework suggest seven potential knowledge brokering goals that researchers might consider in relation to their target audiences:

Using the arts to increase awareness of empirical research or ongoing developments on a particular topic;

Creating spaces for democratic debate and dialogue on pressing issues through making and/or appreciating artworks;

Increasing the accessibility of research through the arts, which can transcend certain cultural and language barriers;

Enhancing engagement with research content by tapping into different senses and ways of knowing through the arts;

Building capacity and support for the implementation of research, such as through professional learning and skill development in/through the arts;

Leveraging the arts as a tool for research-informed advocacy and policy influence;

Facilitating partnerships and co-production among diverse stakeholders using artistic approaches (KUKKONEN & COOPER, 2019). [7]

In the initial planning meetings for this project, we decided the goals would be to 1. foster awareness of issues and themes related to climate change education and transformation, 2. create spaces for dialogue around climate change-related questions, and 3. invite engagement with climate change themes and issues, in ways that spark personal and relational connections for audiences. [8]

From these goals emerged three questions-as-invitations to direct the art exhibit, centering around the themes of human-Earth relationships (How do you love the Earth and how does the Earth love you?), individuals' sense of readiness to enact change (What makes you feel ready to change with the Earth in mind?) and finding strength in uncertain times by looking to past knowledge, experiences, and relationships (As you move into an uncertain future, what will you bring with you from the past?). We crafted these elicit questions with educational practitioners in mind, namely teachers-in-training and instructors in the Faculty of Education. We envisioned a multimedia art exhibit comprising artworks made by members of our team as well as teachers-in-training, that would invite audiences to openly engage with the questions using their different senses and emotions. Our intention was not to communicate climate change facts or research, but to create different entry points for personal and collective reflection in/through the arts. In this way, our approach aligned with what ARCHIBALD, CAINE and SCOTT (2014) called an ambiguous-active ABKT strategy, where the aim is not to convey precise research messages, but rather to "foster critical dialogue or elicit an embodied experience" (p.318) that provokes questioning through active participation and co-creation with audiences. We therefore designed the exhibit to create an embodied experience for audiences through interactive artworks that were organized into three sections, each related to one of the three questions. Our hope was that by interacting with the artworks in the gallery space, audiences could tap into memories and feelings that might encourage them to think critically about their relationship with the Earth, willingness to change, and readiness to move into an uncertain future. In the sections that follow, we describe each of the artworks in detail and how we invited audience participation in relation to the three questions. [9]

3.2 Selecting appropriate art genres and mediums (Phase 2)

The next phase involved choosing art forms that would align with the goals of the project. KUKKONEN and COOPER (2019) outlined different artistic genres and media that researchers have used in their ABKT efforts, including visual arts (e.g., illustrations, comics, quilts), performing arts (e.g., music, drama, dance), creative writing (e.g., poetry, short stories), and multi-media (e.g., video, photography, mixed media installation). The authors stressed the importance of selecting art forms that speak to the project aims and target audiences. For example, an illustrated storybook used in the health-related ABKT examples previously described (e.g., GERDNER, 2008; MUTAMBO et al., 2021), is appropriate for communicating information to children. Other audiences may resonate more with dance (e.g., DELL, 2011) or theater (e.g., COLANTONIO et al., 2008) depending on the cultural, social, or professional context in which the research is conducted. Researchers—particularly those without arts backgrounds—should also consult with or commission a competent artist and/or curator to ensure the artistic integrity of the ABKT initiative (KUKKONEN & COOPER, 2019; LAFRENIÈRE & COX, 2012). [10]

In the case of this project, Tiina was commissioned because of her position as a professional artist and arts educator working in the Faculty of Education, with experience working across a range of visual art forms. She proposed a multimedia art exhibition geared to the target audience (i.e., teachers-in-training and instructors) and addressing the project goals (i.e., engage audiences with climate change-related questions through their different senses). Through the exhibition, audiences could interact with and contribute to the artworks presented in the space, as previously described. [11]

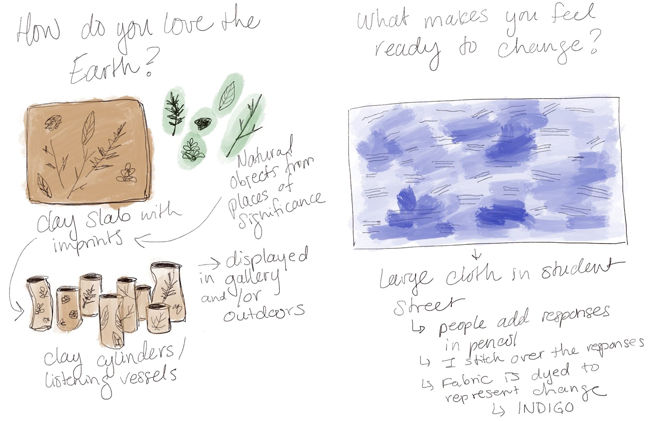

Tiina started by sketching out ideas for artworks (see Figure 2) that could relate to each of the three questions-as-invitations and include target audience participation. As the ideas emerged, she presented them to SSHEAN-affiliated researchers to receive feedback, and integrated their perspectives into the plans accordingly. For all artworks, Tiina proposed using natural and sustainable materials as much as possible to align with the climate change theme such as clay, wool, natural dyes and paints, and donated items. As the project plans progressed, two other artists were also invited to lend their respective expertise in sound design and fabric dyeing. The role of the fiber artist, Bethany GARNER, was to ensure the quality of the indigo dye use in the artworks. The sound installation was an additional exhibit component contributed by Micah FLAVIN (Author 3), SSHEAN research team member, environmental educator, and practicing artist.

Figure 2: Digital planning sketches by commissioned artist, Tiina KUKKONEN. [12]

Here we describe each of the art-making processes and artworks that were included in the final exhibition which we retrospectively identify as the channels through which ABKT occurred. We adopt the concept of channels here—rather than genres, media, mechanisms, or other terms—because we viewed the exhibition as a space where different people and ways of knowing could connect, flow into each other, and/or change directions, like the flow of water. Three channels, detailed below, were designed to engage audiences with each of the three questions-as-invitations. [13]

3.2.1.1 Clay listening devices and eco-drone

Guided by the first question-as-invitation (i.e., How do you love the Earth and how does the Earth love you?), Tiina envisioned a series of clay listening devices that audiences could use to engage in deep listening with/to/for the Earth. As a form of meditation, deep listening involves tuning into and exploring sounds and vibrations in any given environment (OLIVEROS, 2005). In this case, the concept of deep listening was adopted to help amplify awareness of human-Earth relationships. [14]

With the research team, Tiina conceived of a workshop where groups of teachers-in-training could learn about artists working with similar concepts—such as Canadian artist duo, Caitlind R.C. BROWN and Wayne GARRETT—and then create their own clay listening devices, drawing inspiration from their memories and experiences in nature (see Table 1 for the workshop outline). The resulting workshop involved teachers-in-training enrolled in an environmental education course in June 2023. The same workshop was presented to two separate groups of teachers-in-training with a total of 53 participants across the two groups. Participants were told beforehand that all clay devices would be collected at the end of the workshop for exhibition purposes (see Figure 3). Our intention was to allow broader audiences to use the listening devices to engage in deep listening with/to/for the Earth during the final art exhibition, which occurred four months after the workshop.

|

Workshop Segment |

Activities |

|

Part 1: Introductions |

With their table groups, participants were invited to introduce themselves and, if they brought in a natural object, share what object they brought in and why they had chosen that object. |

|

Part 2: How do artists address and/or encourage "change with the Earth in mind?" |

- Introducing the work of BROWN and GARRETT. Specifically, we looked at their "listening devices" that encourage audiences to engage in deep listening with their surroundings. Follow-up discussion question: How might the act of "deep listening" encourage shifts in perspective and/or actions with the Earth in mind? - Introducing the work of Indian contemporary artist, Manav GUPTA, who is known for promoting environmental consciousness and awareness of climate change through his work, such as the series of large-scale installations known as "Excavations in Hymns of Clay" made from clay pottery pieces. Follow-up discussion questions: What is the significance of clay as a medium for promoting environmental consciousness? How is meaning created/changed by displaying multiple clay pieces together versus just one? |

|

Part 3: Creating the clay listening devices |

Objective: Create a device out of clay to encourage deep listening with/for the Earth, inspired by your own connections to nature. Steps: - Roll out a slab of clay; - Imprint natural objects into the slab and use tools to create textures and designs; - Shape and enclose clay device using a score and slip technique; - Refine device as needed. |

|

Part 4: Reflection |

Participants were prompted with the following questions: - What message, thought, or feeling would you attach to your device for gallery audiences to consider? Write your response on a post-it note. - How was the experience of working with the clay and other natural materials? Was there anything that stood out to you? |

Table 1: Outline of clay workshop [15]

During the exhibition, audiences were able to handle the devices while listening to a recorded sound piece created by Micah, consisting of a droning musical composition overlaid with natural sounds (e.g., birds, waves, fire) and voice excerpts (e.g., people talking about climate change). Audiences were able to manipulate the sounds of the eco-drone, as Micah labeled it, using a musical instrument digital interface (MIDI) controller. The meditative sound of the eco-drone served to ground and hold audiences in the gallery space, while the sound bites aimed to elicit memories and associations with different natural spaces and phenomena, effectively reinforcing the theme of human-Earth relationships. To hear a sound sample of the eco-drone, please see the SSHEAN website. [16]

The use of clay was also significant for engaging audiences with this first question, as it is a material that comes directly from the Earth. The act of handling and manipulating the clay therefore created a tangible connection between the individuals' bodies and the Earth, both during the workshop and subsequent exhibition. Clay that is not glazed and fired can also be returned to the Earth. Thus, we chose a biodegradable air-drying clay with no known adverse effects on the environment. After exhibiting the works, we returned the clay back to the Earth by positioning the devices outside of the Faculty of Education and allowing the elements to reclaim the clay over time (see Figure 4).

Figure 3: Clay listening devices installed in the gallery, October 2023. Visitors to the exhibition were encouraged to use

the listening devices to interact with the eco-drone, such as by holding them to their ears like conch shells.

Figure 4: Remnants of clay devices outside on May 17, 2024. Over the winter of 2023-24, the clay listening devices which had

not been fired, were left out to the elements to disintegrate and decay. This created another ABKT installation within the larger project. [17]

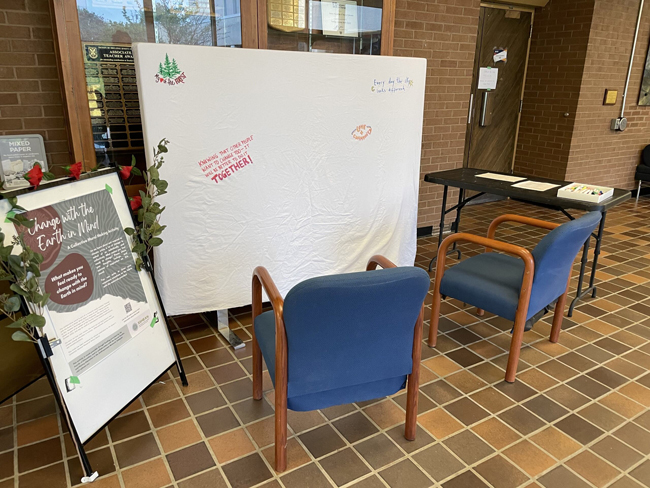

To engage target audiences with the second question-as-invitation (i.e., What makes you feel ready to change with the Earth in mind?), the team conceived of a fabric mural where teachers-in-training and others could write or draw responses to the question using fabric markers. A large piece of upcycled white cotton fabric and fabric markers were installed in a high-traffic area within the Faculty of Education, with posters describing the activity and prompting question (see Figure 5). The mural was left in the space for a period of two weeks during summer classes. After collecting the mural, the artist-researcher team observed the responses and collectively embroidered images and words that stood out as significant (see Figure 6). The fabric mural was then cinched and indigo-dyed with the help of fiber artist Bethany GARNER who has extensive technical experience in fabric-dyeing. Indigo was selected because of its history as a naturally sourced dye that has been traded and used by cultures all over the world for centuries. Like most indigo dyes used today, the dye selected for this project was synthetically produced, but molecularly identical to natural indigo. Synthetic or not, indigo is not water-soluble and must therefore undergo a chemical change process, known as reduction-oxidation, to work as a fabric dye.

Figure 5: Cotton fabric and markers installed in a public area to invite responses to the question: "What makes you feel ready

to change with the Earth in mind?"

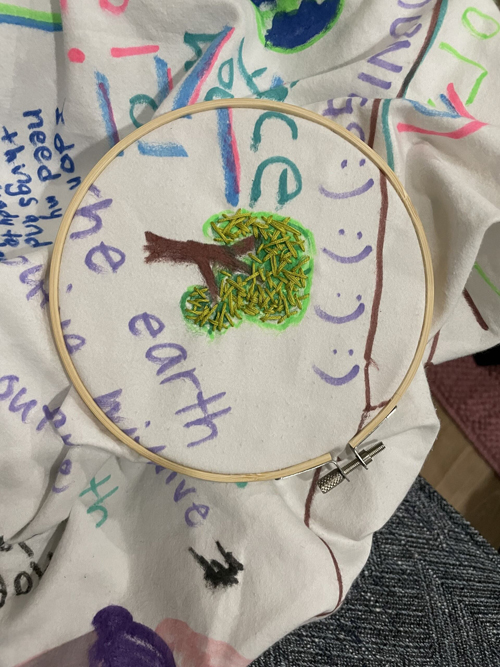

Figure 6: Research team members embroidering a drawing of a tree, contributed by a public mural participant [18]

Mural-making can encourage community-building and collective purpose, as individuals come together to design and create imagery around a common theme or cause (e.g., GERSTENBLATT, SHANTI & FRISK, 2022; PETRONIENĖ & JUZELĖNIENĖ, 2022). In this case, individuals could reflect on and add their unique responses to the question while appreciating—or even relating to—the responses of others. The process of embroidering and dyeing the mural was meant to signify change or transformation "with the Earth in mind," and the idea that all individual motivations, as illustrated in the mural, can be catalysts for positive change (see Figure 7 for completed mural).

Figure 7: Finished mural displayed in the gallery space, October 2023. The mural process included public contributions (words

and drawings), embroidery by the researchers, and a natural indigo dying process in collaboration with a fabric artist. [19]

3.2.1.3 Mixed media swamp installation

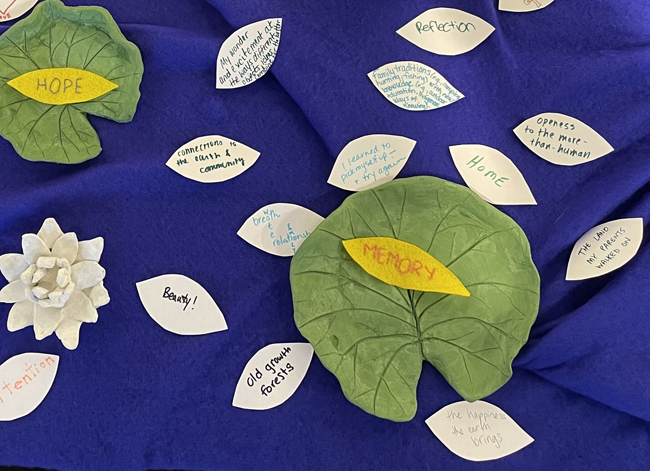

For the final question-as-invitation (i.e., As you move into an uncertain future, what will you bring with you from the past?), Tiina created a mixed media installation, The Swamp of Promise, consisting of a felt artwork—hand-felted with natural wool—hanging over the top of a collection of five clay lily pads and flowers (see Figure 8). Each lily pad was painted with eco-friendly milk paint and contained a single felt petal embroidered with a word. The installation title and five words (hope, ceremony, relationship, memory, and knowledge) represent themes that emerged from discussions with the research group, focused on the ways of knowing, being, and doing humans can draw from their individual and collective pasts as they navigate uncertainty in the face of climate change. During the exhibition, audiences were prompted to think about the knowledge, memories, relationships, ceremonies, and hopes they will carry into an uncertain future. They could then choose to write or draw their responses on a paper petal and add it to the Swamp of Promise.

Figure 8: Swamp of Promise installation and associated title cards. Please click here or on the figure for an enlarged version of Figure 8. [20]

Inspiration for the hanging felt piece also derived from meetings with the research group where we discussed the phenomenon of ignis fatuus,1) also known as will-o-the-wisp, which refers to an atmospheric light that can appear over marshlands due to the combustion of gas from decomposing organic matter. Metaphorically, ignis fatuus can mean a deceptive hope or goal, as travelers can be deceived by the swamp light in the darkness of night, mistaking it for human dwellings (OGDEN, 2022). However, the research group members were more inclined to adopt literature scholar Emily OGDEN's perspective where one can follow an ignis fatuus “for a little while without having an inflated sense of the promise it holds" (p.109), allowing the path to sustain you even if it does not last forever. The felted piece, an ignis fatuus, and the Swamp of Promise as a whole, represent the glimmers of hope, temporary or lasting as they may be that drive people forward in uncertain times. Audiences were invited to use a flashlight to manipulate the backlighting of the felt piece to create the sense of light one might see from an ignis fatuus. [21]

Together, these three channels (clay listening devices/eco-drone, fabric mural, swamp installation) created an eddy within the exhibition space, like the eddy of a river, where people and different forms of knowledge moved towards one another. In the eddy, participants could pause to notice the dominant current, such as their relationship with the earth at this time and consider whether and how to reframe their perspective in relation to the dominant current, potentially drawing on new meanings. [22]

3.3 Building partnerships to strengthen the ABKT initiative (Phase 3)

ABKT initiatives typically involve partnerships among artists and researchers, especially when researchers do not possess the artistic background required to realize the project. In many cases, however, additional partners are needed to contribute specific knowledge, skills, and resources to strengthen project outcomes (LAPUM, RUTTONSHA, CHURCH, YAU & DAVID, 2011; WATFREN et al., 2023). Our art exhibition project involved several partners—in addition to the artist-researcher team—who all contributed to different project requirements by providing funding, donating materials and space, lending expertise, and/or volunteering to participate in certain phases of the project (see Table 2 below).

|

Project Contributions |

Partners |

|

Funding |

|

|

Initial seed funding for the project |

Office of the Associate Dean, Research and Strategic Initiatives, Faculty of Education |

|

Graduate research assistant time to contribute to designing project, ethics approval process, collecting and analyzing data (mural embroidery, clay workshop observations and photographs) |

Sara KARN and Micah FLAVIN, Social Studies and History Education in the Anthropocene Network (SSHEAN) |

|

Funding to pay for the creation of the soundscape/eco-drone |

Community Initiatives Fund, Faculty of Education |

|

Materials, space, and expertise |

|

|

Sound equipment and music/sound expertise |

Micah FLAVIN, professional musician, SSHEAN member, and graduate student |

|

Fabric for mural and sewing expertise |

Soili KUKKONEN, quilter |

|

Fabric dyeing material and dyeing expertise |

Bethany GARNER, fiber artist |

|

Gallery space for final exhibition |

Arts Infusion Committee, Faculty of Education |

|

Workshop participants |

|

|

Teacher candidates needed to participate in the clay workshop

|

Rebecca EVANS, Instructor of environmental education course, Faculty of Education, and teacher candidates who self-selected |

|

Advertising |

|

|

Promoting the exhibition through the faculty newsletter and website |

Communications team, Faculty of Education |

Table 2: List of project contributions and associated partners [23]

Like other arts-based projects aimed at engaging research audiences, we found that additional partnerships and resources were key to realizing our vision for the exhibition (BALL, LEACH, BOUSFIELD, SMITH & MARJANOVIC, 2021). The project would not have materialized in the same way without all these contributions. [24]

3.4 Planning methods for disseminating and tracing impact (Phase 4)

In the final phase of KUKKONEN and COOPER's (2019) planning framework, the authors invited researchers to consider what methods and indicators they might use to trace dissemination and impact. However, notions of impact are wide-ranging and can be challenging to assess, particularly when the arts are involved (LAFRENIÈRE & COX, 2012). KUKKONEN and COOPER (2019) acknowledged the wide range of impacts that are possible in arts-based initiatives—including raising awareness of issues, shifting attitudes, and direct changes to policy and practice—and emphasized that any assessment of impact should 1. link to the original goals and target audiences of the mobilization efforts and 2. align with the artform(s) used. Five categories of impact indicators were suggested to facilitate the evaluation of ABKT efforts while recognizing that the value of ABKT lies predominantly in "the process of knowledge co-construction that occurs among researchers, participants, artists, and audiences" (p.305). [25]

Of the five impact indicator categories, we focused on three categories—reach indicators, partnership and collaboration indicators, and usefulness indicators—that align with the goals, audiences, and art forms outlined for this initiative. The other two categories (practice, program or service indicators; policy and advocacy indicators) were deemed irrelevant to this project. In Table 3, we summarize the three relevant categories and impact indicators in relation to this project.

|

Impact Categories (KUKKONEN & COOPER, 2019) |

Project Impact Indicators |

|

Reach indicators: Measure how many people a particular project, performance, or product has reached.

|

- Teachers-in-training who participated in the clay workshops (n=53) - Collaborative mural contributors (n=50+) - Gallery visitors (n=88) - Viewers of the disintegrating clay listening devices (n=unknown) - Conference presentation attendees to date (n=40) |

|

Partnership and collaboration indicators: measure processes of co-production and dissemination of ABKT with different partners - Numbers of products developed - Numbers and type of capacity building efforts - Engagement of stakeholders

|

- Clay-making workshops (n=2) - Collaborative mural making activity (n=1) - Gallery exhibition (n=1), consisting of 53 clay listening devices, 1 eco-drone, 1 fabric mural, 1 felt artwork, 5 clay lily pads - Targeted reception and lecture events (n=4) aimed at education audiences - Conference presentations (n=2) - Informal observations of audience engagement |

|

Usefulness indicators: Measure whether a target audience found the ABKT products useful |

Guestbook comments (n=23)

|

Table 3: ABKT impact categories and associated project indicators [26]

3.4.1 Impact indicators in relation to ABKT goals

3.4.1.1 Fostering awareness (Goal 1)

Because we aimed to foster broader awareness of issues and themes related to climate change education, the number of people reached through this initiative (i.e., reach indicator) was selected as an appropriate impact indicator. In total, the project reached over 200 participants, including teachers-in-training, faculty members and staff, graduate students, alumni, and members of the wider community, ranging from small children to older adults. [27]

3.4.1.2 Creating spaces for dialogue (Goal 2)

To determine if/how we created spaces for dialogue, we looked for the number and type of opportunities we offered for people to engage with climate change-related questions and co-produce knowledge by interacting with artworks and materials (i.e., partnership and collaboration indicators). These opportunities (n=4) included the two clay-making workshops with teacher candidates, the collaborative mural making activity and the gallery exhibition, all of which provided audiences the chance to manipulate materials and contribute to the exhibited artworks. We also created space for dialogue through two conference presentations with education and research audiences in June 2024 and October 2024. Photographs and narratives of the project are viewable on the SSHEAN website. [28]

3.4.1.3 Inviting engagement (Goal 3)

Examining our goal of inviting engagement with climate change themes and issues involved taking a closer look at 1. how we actively engaged stakeholders through different events in the gallery and 2. our observations of stakeholder engagement with the works (i.e., partnership and collaboration indicators). In terms of stakeholder events, we hosted two opening receptions for education students and faculty, one Homecoming reception event, and one guest lecture for a graduate class. Each event provided opportunities for the research team to discuss the aims of the project and encourage education audiences—as well as broader audiences—to engage with the questions and associated artworks. Micah also performed with the eco-drone at the two reception events to further enhance audiences' experience in the gallery. [29]

For the duration of the exhibition, Tiina, Heather, and Micah individually observed how people were interacting with the works. We then shared our observations with each other during a recorded debrief discussion at the end of the show. Collectively, we agreed that the interactive artworks allowed audiences to engage with the questions through their different feelings and senses, thus encouraging empathetic, relational, and playful types of engagement. For example, the written/drawn responses added to the Swamp of Promise offered people the chance to "share something of themselves and their values," as stated by Heather, and see connections across their own and others' responses (see Figure 9). Micah talked about how the sounds of the eco-drone opened a "sensory alley" that encouraged people to engage with climate messages in a visceral way. By pressing all the voice excerpt buttons at once on the MIDI controller, audiences would get a jumble of overlapping voices. Micah explained that in doing so, "you cannot discern what exactly they're saying, but maybe you hear the urgency in their voices and feel the overwhelm." As another example, pressing the fire sounds invoked, for some, images and feelings associated with wildfires that are becoming more commonplace and destructive across Canada due to climate change.

Figure 9: Visitor responses added to the Swamp of Promise [30]

We also observed how the gallery became a space where people of all ages could play with the complex questions and materials we presented. Like an eddy, the gallery allowed for a pause, a spin, or new vantage point. For instance, we noted how the interactive nature of the exhibition made it possible for young children—attending the show with their parents—to engage with the concepts by playing with materials like the clay devices, eco-drone, and flashlight. We saw different games emerge as adults and children moved through the room together, such as playing "I spy" with the fabric mural (e.g., "I spy a tree" or "I spy a flower"). Having children in the space also encouraged people to interact with the clay devices. While adults were often hesitant to touch the clay, children eagerly picked up and handled all the pieces, fostering a more playful and inviting atmosphere for everyone. The intergenerational audiences and interactions were not something we consciously planned for as a research team, but they nonetheless contributed to our goal of inviting engagement through personal and relational connections, as people of different ages shared their ideas, observations, and feelings with each other. Similarly to the ABKT project described by ARCHIBALD (2022), we found that including text, sound, and visuals created diverse access points for these different age groups to engage with our themes. [31]

Like other ABKT initiatives where researchers use multimedia art exhibits to engage target audiences (e.g., BRUCE et al., 2013; COLE & McINTYRE, 2004), we invited informal feedback to gauge audience experience of the exhibition (i.e., usefulness indicator). To gather feedback, we set up a guestbook in the gallery so that visitors could leave open-ended comments. Because we did not offer any specific feedback prompts for visitors to consider, we reviewed the comments (n=23) for general impressions that offered insight into the experience. While systematic coding was not used, we informally noted patterns across the comments. For example, some of the comments described the exhibition as "beautiful," "peaceful," "moving" and "inspiring." One comment articulated appreciation for the interactive components that activated all the senses, which made the experience more "fun." Two other visitors commented how the exhibition acted as a "reminder" to slow down, care, and connect. While not specific to climate change themes, these comments indicate audience engagement and positive perceptions of the exhibition. [32]

4. Learning from the ABKT Planning Framework in Action

Reflecting together as a research-artist team, here we explain what we learned about creating a strong artist-researcher partnership and remaining open to playfulness in the case of our project. We suggest these insights into the actions we took to merge our research and artist practices could be helpful to others in planning for future artist-researcher collaborations. [33]

4.1 Artist-researcher partnership-building

Partnerships are characterized by individuals sharing knowledge, setting common objectives, and agreeing on strategies to achieve those objectives (RATHI, GIVEN & FORCIER, 2014). However, merging goals and strategies can be challenging when people enter partnerships with differing values, interests, and backgrounds. In artist-researcher partnerships, the practices of artists and researchers can seem at odds with each other, prompting the need for initial and ongoing communication about how each party thinks and works (GEWIN, 2021). In the case of this project, Tiina (the artist) entered the partnership with a limited understanding of Heather's (the researcher) approach to climate change and eco-justice education, whereas Heather entered with uncertainty around the collaborative process and how Tiina's artistic practice would connect to SSHEAN's research. Thus, within the first few weeks of the partnership, Tiina met several times with Heather and the research team to become familiar with their research interests and ways of thinking, as well as share emerging ideas for the exhibition. Through these meetings, intersecting values, ideas, and practices began to materialize and inform the project. For instance, we recognized that the art-making process can be rife with risks and unknowns, just as the future is risky and uncertain in the face of climate change. Both contexts call upon individuals to contend with and even welcome the unknown in the hopes that something positive and/or constructive will come out of it. We also found that a detachment from prescribed outcomes aligned with our joint philosophies of education and approaches to teaching. As a result, our project was founded in a common understanding of the need to embrace what we do not (or cannot) know, and we allowed the process to develop intuitively instead of getting attached to intended results. [34]

While designing an ABKT exhibition on patients' narratives of open-heart surgery, LAPUM and colleagues (2011) spent over a year discussing the research, artistic content, and design of the exhibition to ensure that it truly reflected the patients and their narratives. We similarly found that we needed time to fully conceptualize and work through the different aspects of the exhibition, including our underlying values as artists, researchers, and educators. As such, the project took nearly ten months to complete from the first conversation to the final exhibition. Had we not taken the necessary time to learn about each other's work and continuously talk through our emerging goals, the project might not have captured our combined vision. Therefore, to foster mutually beneficial ABKT partnerships, we urge artist-researcher partners to consider and respect each other's points-of-view, find commonalities in practice, be flexible, and keep the lines of communication open throughout the project. This approach aligns the recommendations given by artists in GEWIN's (2021) article on productive artist-scientist collaborations, which include "doing your homework" (p.515) on each other's professional practices, fostering "a deep respect for the other's work" (p.518), and creating "two-way experiences" (p.517) that benefit both parties. [35]

4.2 Adopting playful processes

We retrospectively found that our ABKT processes and exhibition were grounded in playfulness, that is, spontaneous behavior which promotes divergent and creative thinking, characterized by a willingness to follow unknown pathways (BATESON & MARTIN, 2013). By inviting participation in the artmaking, we had to give up control over certain parts of the process which in turn illuminated new ideas and ways of thinking. For example, when we invited people to respond to our second question (What makes you feel ready to change with the Earth in mind?) on the fabric mural, we did not anticipate that a group of young dancers—participating in a weekend dance recital in our education building—would write dance-related messages on the fabric (e.g., "Slay Queen," "Dance your heart out," "Feel the beat," "From the top, make it drop") instead of responding to our prompt. After some initial disappointment, we embraced the spontaneity that comes with leaving art in a public space and inviting community interaction. While the dancers' responses were not related to our theme, they were still positive, motivational, and funny, which reminded us of the importance of humor and togetherness in times of ecoanxiety. The interplay between the different types of responses on the mural also reflected for us the diversity of approaches needed to respond to the climate crisis. It would have been simple enough to discard the mural and try again, but instead we saw an opportunity to generate meaning from this unanticipated occurrence. We therefore encourage researchers to consider embracing playful and unexpected responses to ABKT initiatives as these can lead to meaningful discoveries. [36]

Play is also recognized as an important way for people, especially children, to navigate complex issues and circumstances they encounter in the world (e.g., BROWNELL, 2022; SEOW, 2019). Through play, individuals can try out different scenarios and imagine new possibilities in a safe space without the need to produce definitive answers, which encourages exploration and risk-taking (ZOSH et al., 2017). In the context of climate change education, learners of all ages need opportunities to cope with their climate-related feelings (e.g., anxiety, fear, guilt) and imagine different pathways forward. Hence, we crafted questions-as-invitations that would elicit affective and imaginative responses, without expecting concrete solutions, and created a space where people could play with the questions and related artworks. We view this type of playful approach as being fruitful for any ABKT project that aims to engage audiences with critical issues facing society and the planet. As noted by HENRICKS (2014), "play expresses people's commitment to make and inhabit a new world. It is something we improvise together" (p.195). [37]

The four-phase ABKT planning framework (KUKKONEN & COOPER, 2019) allowed us, as artist-researcher-educators, to reflect deeply on the process of developing this exhibition, from setting initial goals to observing the potential impact of our project. Some of our actions produced ABKT outcomes, such as building a strong artist-researcher partnership and adopting playful practices that could only be seen in retrospect as a direct result of using the framework to structure our thinking. Through this analysis, we acknowledged the importance of selecting materials and processes that align with ABKT goals and audiences. In this case, incorporating artistic materials and genres that would encourage tangible and emotional connections to the Earth (e.g., clay, eco-drone) aligned with our quest to invite engagement with climate change issues. Our focus on co-creating knowledge with target audiences through participatory processes (e.g., clay workshops with teacher candidates, fabric mural-making, and interactive gallery artworks) and gallery events (e.g., receptions and guest lecture) fostered spaces for dialogue and raising awareness. Partnerships with people outside of the core artist-researcher team added additional resources and expertise (e.g., funding, materials, gallery space, artistic knowledge) that contributed to the overall success of the project, and although measuring impact was not a goal from the outset, we were able to identify three categories of ABKT impact indicators that applied to the project (i.e., reach, partnership and collaboration, and usefulness indicators) which could be expanded on in future initiatives. [38]

Perhaps the most meaningful learning, for us, derived from our team meetings where we shared knowledge of our practices, discussed emerging directions, and reflected on our observations. The commitment to shared goals and open communication led to a mutually beneficial and respectful partnership that was valued by all members of the core team. By adopting flexible and playful approaches to our processes we were able to merge our professional values and interests, as well as generate insights into the connections between art, play, and climate change education research. The results left us inspired to further investigate these connections in the future. [39]

We hope that sharing our experience can help others see the value of artist-researcher partnerships—and the ABKT planning framework (KUKKONEN & COOPER, 2019) to facilitate these partnerships—which enable the exploration of "sensory, embodied, and emotional processes" (ARCHIBALD, 2022, p.194) that are often omitted from research. Providing target audiences with opportunities to understand and connect to research knowledge in artistic ways can incite much-needed shifts in thinking and action. However, we recognize that researchers, particularly in non-arts disciplines, may have difficulty envisioning the possibilities and benefits of ABKT within their areas of study. In such cases, they may refer to the many existing examples in the global literature from disciplines such as healthcare (e.g., KUHLMANN, THOMAS, INCIO-SERRA & BLAIN-MORAES, 2024; SPAGNOL, TAGAMI, DE SIQUEIRA & LI, 2019; THÉBERGE et al., 2024), environmental sciences (e.g., CLARK et al., 2020; STILLER-REEVE & NAZNIN, 2018), and business (e.g., CACCIATORE & PANOZZO, 2021), among others (see additional examples outlined in KUKKONEN & COOPER, 2019). We urge researchers to keep in mind the importance of transcending disciplinary siloes to address complex problems in areas of critical concern (CLARK et al., 2020). In our case, the focus area was climate change and ecojustice education, but the ABKT framework we employed is adaptable to diverse contexts and aims to promote transdisciplinary thinking through artist-researcher partnerships. We described our project in depth through the framework lens to illustrate how other researchers could do the same. Ultimately, we encourage researchers and artists to work, play, and make art together with common cause. Who knows where it may lead, and that is indeed the point. [40]

1) https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/ignis%20fatuus [Accessed: March 4, 2025]. <back>

Archibald, Mandy M. (2022). Interweaving arts-based, qualitative and mixed methods research: Showcasing integration and knowledge translation through material and narrative reflection. International Review of Qualitative Research, 15(2), 168-198, https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/19408447221097063 [Accessed: March 4, 2025].

Archibald, Mandy M. & Scott, Shannon D. (2019). Learning from usability testing of an arts-based knowledge translation tool for parents of a child with asthma. Nursing Open, 6(4), 1615-1625, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/nop2.369 [Accessed: March 12, 2025].

Archibald, Mandy M.; Caine, Vera & Scott, Shannon D. (2014). The development of a classification schema for arts-based approaches to knowledge translation. Worldviews of Evidence-Based Nursing, 11(5), 316-324.Ball, Sarah; Leach, Brandi; Bousfield, Jennifer; Smith, Pamina & Marjanovic, Sonja (2021). Arts-based approaches to public engagement with research. RAND, January 11, https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA194-1.html [Accessed: March 4, 2025].

Bateson, Patrick & Martin, Paul (2013). Play, playfulness, creativity and innovation. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Bentz, Julia (2020). Learning about climate change in, with and through art. Climatic Change, 162(3), 1595-1612, https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10584-020-02804-4 [Accessed: March 4, 2025].

Boydell, Katherine (2020). Using performative art to communicate research: Dancing experiences of psychosis. LEARNing Landscapes, 13(1), 77-85, https://doi.org/10.36510/learnland.v13i1.1004 [Accessed: March 4, 2025].

Boydell, Katherine; Gladstone, Brenda M.; Volpe, Tiziana; Allemang, Brooke & Stasiulis, Elaine (2012). The production and dissemination of knowledge: A scoping review of arts-based health research. Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 13(1), Art, 32, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0014-fqs1201327. [Accessed: March 4, 2025].

Brownell, Cassie J. (2022). Navigating play in a pandemic: Examining children's outdoor neighborhood play experiences. International Journal of Play, 11(1), 99-113.

Bruce, Anne; Schick Marakoff, Kara L.; Sheilds, Laurene; Beuthin, Rosanne; Molzahn, Anita & Shermak, Sheryl (2013). Lessons learned about arts-based approaches for disseminating knowledge. Nurse Researcher, 21(1), 23-28.

Cacciatore, Silvia & Panozzo, Fabrizio (2021). Models for art & business cooperation. Journal of Cultural Management and Cultural Policy, 2, 170-199, https://jcmcp.org/articles/models-for-art-business-cooperation/?lang=en [Accessed: March 4, 2025].

Cachelin, Adrienne & Nicolosi, Emily (2022). Investigating critical community engaged pedagogies for transformative environmental justice education. Environmental Education Research, 28(4), 491-507.

Chappell, Callie R. & Muglia, Louis J. (2023). Fostering science-art collaborations: A toolbox of resources. PLOS Biology, 21(2), https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3001992 [Accessed: March 4, 2025].

Chawla, Louise (2020). Childhood nature connection and constructive hope: A review of research on connecting with nature and coping with environmental loss. People and Nature, 2(3), 619-642, https://doi.org/10.1002/pan3.10128 [Accessed: March 4, 2025].

Clark, Sarah E., Magrane, Eric; Baumgartner, Thomas; Bennett, Scott E. K.; Bogan, Michael; Edwards, Taylor; Dimmitt, Mark A.; Green, Heather; Hedgcock, Charles; Jonhson, Benjamin M.; Johnson, Maria R.; Velo, Kathleen & Wilder, Benjamin T. (2020). 6&6: A transdisciplinary approach to art-science collaboration. BioScience, 70(9), 821-829, https://academic.oup.com/bioscience/article/70/9/821/5875254 [Accessed: March 4, 2025].

Colantonio, Angela; Kontos, Pia C.; Gilbert, Julie E.; Rossiter, Kate; Gray, Julia & Keightley, Michelle L. (2008). After the crash: Research-based theater for knowledge transfer. Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions, 28(3), 180-185.

Cole, Ardra A. & McIntyre, Maura (2004). Research as aesthetic contemplation: The role of the audience in research interpretation. Educational Insights, 9(1), https://epe.lac-bac.gc.ca/100/202/300/educational_insights/2007/v11n01/publication/insights/v09n01/pdfs/cole.pdf [Accessed: March 12, 2025].

Cooper, Amanda (2014). Knowledge mobilisation in education across Canada: A cross-case analysis of 44 research brokering organizations. Evidence & Policy, 10(1), 29-59.

Cooper, Amanda; Rodway, Joelle & Read, Robyn (2018). Knowledge mobilization practices of educational researchers across Canada. Canadian Journal of Higher Education, 48(1), 1-21, https://journals.sfu.ca/cjhe/index.php/cjhe/article/view/187983 [Accessed: March 4, 2025].

Cooper, Amanda; Searle, Michelle; MacGregor, Stephen & Kukkonen, Tiina (2023). The audacity of imagination: Arts-informed approaches to research and co-production. In OECD (Eds.), Who really care about using education in policy and practice?: Developing a culture of research engagement (pp.147-173). OECD Publishing. https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/who-really-cares-about-using-education-research-in-policy-and-practice_bc641427-en.html [Accessed: March 4, 2025].

Dell, Colleen Ann (2011). Voices of healing: Using music to communicate research findings. In Juanita Bascu & Fleur Macqueen Smith (Eds.), Innovations in knowledge translation: The SPHERU KT casebook (pp.9-14). Saskatoon: Saskatchewan Population Health and Evaluation Research Unit, https://spheru.ca/publications/files/SPHERU%20KT%20Casebook%20June%202011.pdf [Accessed: March 12, 2025].

Gerdner, Linda A. (2008). Translating research findings into a Hmong American children's book to promote understanding of persons with Alzheimer's disease. Hmong Studies Journal, 9, 1-29, https://www.hmongstudiesjournal.org/hsj-volume-9-2008.html [Accessed: March 4, 2025].

Gerstenblatt, Paula; Shanti, Caroline & Frisk, Samantha (2022). One piece at a time: Building community and a mosaic mural. Journal of Community Engagement and Scholarship, 15(1), 1-14, https://jces.ua.edu/articles/10.54656/jces.v15i1.477 [Accessed: March 4, 2025].

Gewin, Virginia (2021). How to shape a productive science-art collaboration. Nature, 590, 515-518.

Gunson, Bryce; Murphy, Brenda L. & Brown, Laura J. (2021). Knowledge mobilization, citizen science, and education. Journal of Community Engagement and Scholarship, 13(3), 36-55, https://jces.ua.edu/articles/10.54656/VWXA9015 [Accessed: March 4, 2025].

Henricks, Thomas S. (2014). Play as self-realization: Toward a general theory of play. American Journal of Play, 6(2), 190-213, https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1023798.pdf [Accessed: March 4, 2025].

Kuhlmann, Naila; Thomas, Aliki; Incio-Serra, Natalia & Blain-Moraes, Stefanie (2024). Piece of mind: Knowledge translation performances for public engagement on Parkinson's disease and dimentia. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1439362 [Accessed: March 4, 2025].

Kukkonen, Tiina & Cooper, Amanda (2019). An arts-based knowledge translation (ABKT) planning framework for researchers. Evidence & Policy, 15(2), 293-311.

Lafrenière, Darquise & Cox, Susan M. (2012). "If you can call it a poem": Toward a framework for the assessment of arts-based works. Qualitative Research, 13(3), 318-336.

Lapum, Jennifer; Ruttonsha, Perin; Church, Kathryn; Yau, Terrence & David, Allison Matthews (2011). Employing the arts in research as an analytical tool and dissemination method: Interpreting experience through the aesthetic. Qualitative Inquiry, 18(1), 100-115.

Miller, Evonne (2024). The Black Saturday bushfire disaster: Found poetry for arts-based knowledge translation in disaster risk and climate change communication. Arts & Health, 17(1), https://doi.org/10.1080/17533015.2024.2310861 [Accessed: March 4, 2025].

Mutambo, Chipo; Shumba, Kemist & Hlongwana, Khumbulani W. (2021). Exploring the mechanism through which a child-friendly storybook addresses barriers to child-participation during HIV care in primary healthcare settings in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. BMC Public Health, 21(1), 508, https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-021-10483-8 [Accessed: March 4, 2025]

Nutley, Sandra M.; Walter, Isabel & Davies, Huw T.O. (2007). Using evidence: How research can inform public services. Bristol, UK: Policy Press.

Ogden, Emily (2022). On not knowing: How to love and other essays. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Oliveros, Pauline (2005). Deep listening: A composer's sound practice. New York, NY: IUniverse.

Petronienė, Saulė & Juzelėnienė, Saulutė (2022). Community engagement via mural art to foster a sustainable urban environment. Sustainability, 14(16), 10036, https://doi.org/10.3390/su141610063 [Accessed: March 4, 2025].

Pihkala, Panu (2020). Anxiety and the ecological crisis: An analysis of eco-anxiety and climate anxiety. Sustainability, 12(19), 7836, https://doi.org/10.3390/su12197836 [Accessed: March 4, 2025].

Rathi, Dinesh; Given, Lisa M. & Forcier, Eric (2014). Interorganisational partnerships and knowledge sharing: The perspective of non-profit organisations. Journal of Knowledge Management, 18(5), 867-885.

Scott, Shannon D., Hartling, Lisa; O'Leary, Kathy A.; Archibald, Mandy & Klassen, Terry P. (2012). Stories—A novel approach to transfer complex health information to parents: A qualitative study. Arts & Health, 4(2), 162-173.

Seow, Janet (2019). Black girls and dolls navigating race, class, and gender in Toronto. Girlhood Studies, 12(2), 48-64.

Spagnol, Gabriela Salim; Tagami, Carolinne Yuri; de Siqueira, Gabriella Bagattini & Li, Lin Mi (2019). Arts-based-knowledge translation in aerial silk to promote epilepsy awareness. Epilepsy & Behavior, 93, 60-64, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S152550501830787X [Accessed: March 4, 2025].

Stiller-Reeve, Mathew & Naznin, Zakia (2018). A climate for art: Enhancing scientist-citizen collaboration in Bangladesh. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, 99(3), 491-497.

Théberge, Julie; Smithman, Mélanie Ann; Turgeon-Pelchat, Catherine; Tounkara, Fatoumata Korika; Richard, Véronique; Aubertin, Patrice; Léonard, Patrick; Alami, Hassane; Singhroy, Diane & Fleet, Richard (2024). Through the big top: An exploratory study of circus-based artistic knowledge translation in rural healthcare services, Quebec, Canada. PLoS ONE, 19(4), https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0302022 [Accessed: March 4, 2025].

Watfren, Chloe; Triandafilidis, Zoi; Vaughan, Priya; Doran, Barbara; Dadich, Ann; Disher Quill, Kate; Maple, Peter; Hickman, Louise; Elliot, Michele & Boydell, Katherine (2023). Coalescing, cross-pollinating, crystallising: Developing and evaluating an art installation about health knowledge. Qualitative Health Research, 33(1-2), 127-140, https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/10497323221145120 [Accessed: March 4, 2025].

Williams, Lisa; Tavares, Tatiana; Egli, Victoria; Moeke-Maxwell, Tess & Gott, Merryn (2023). Vivian, the graphic novel: Using arts-based knowledge translation to explore gender and palliative care. Mortality, 28(3), 383-394.

Zosh, Jennifer M.; Hopkins, Emily J.; Jensen, Hanne; Liu, Claire; Neale, Dave; Hirsh-Pase, Kathy; Solis, S. Lynneth & Whitebread, David (2017). Learning through play: A review of the evidence. White paper, LEGO Foundation, https://cde-lego-cms-prod.azureedge.net/media/wmtlmbe0/learning-through-play_web.pdf [Accessed: March 4, 2025].

Tiina KUKKONEN is an assistant professor of visual arts education at Queen's University, Canada. Tiina has contributed research in the areas of early childhood development through art, artist-school partnerships, and rural arts education. She also has a keen interest in arts-based approaches to research and knowledge translation. The driving force behind her work is the desire to make visual arts and arts education accessible, relevant, and inspiring for all.

Contact:

Tiina Kukkonen

Faculty of Education

Duncan McArthur Hall

Queen's University

511 Union Street West, Kingston, Ontario K7M 5R7, Canada

E-mail: tiina.kukkonen@queensu.ca

Heather E. McGREGOR is an assistant professor of curriculum theory at Queen's University, Canada. Heather has published in a range of Canadian and international journals on topics including the history of Inuit education and curriculum change in the Canadian Arctic, decolonizing research methodologies, experiential learning, and theorizing history and social studies learning in the context of climate crisis.

Contact:

Heather E. McGregor

Faculty of Education

Duncan McArthur Hall

Queen's University

511 Union Street West, Kingston, Ontario K7M 5R7, Canada

E-mail: heather.mcgregor@queensu.ca

Micah FLAVIN is an interdisciplinary researcher, teacher, and artist based in Tiohtià:ke/Mooniyaang (Montréal, Quebec). He is interested in wetlands, contradictions, and the cultural politics of emotions.

Contact:

Micah Flavin

Faculty of Education

Duncan McArthur Hall

Queen's University

511 Union Street West, Kingston, Ontario K7M 5R7, Canada

E-mail: micah.flavin@queensu.ca

Amanda COOPER is dean of the Mitch and Leslie Frazer Faculty of Education, and a professor of educational policy and leadership at Ontario Tech University in Canada. Amanda specializes in knowledge mobilization and translation, interdisciplinary collaborations, and measuring research impact across multi-stakeholder networks in public service sectors. With her innovative research program Research Informing Policy, Practice, and Leadership in Education (RIPPLE), she aims to accelerate research impact in public service sectors via multi-stakeholder networks.

Contact:

Amanda Cooper

Mitch and Leslie Frazer Faculty of Education

Ontario Tech University

61 Charles Street, Oshawa, Ontario L1H 4X8, Canada

E-mail: amanda.cooper@ontariotechu.ca

Kukkonen, Tiina; McGregor, Heather E.; Flavin, Micah & Cooper, Amanda (2025). Inviting engagement with climate change education research: An arts-based knowledge translation approach [40 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 26(2), Art. 11, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-26.2.4313.