Volume 26, No. 3, Art. 8 – September 2025

An Epistemic Framework for Integrating Configurative Systematic Reviews, Gadamerian Hermeneutics, and Reflexive Thematic Analysis

Francisco R.B. Fonsêca & Débora C.P. Dourado

Abstract: Systematic reviews follow a rigorous protocol for identifying, selecting, evaluating, and synthesizing literature. Yet, scholars frequently overlooked the need for epistemological justification when combining diverse research approaches, resulting in ambiguity around their effective integration. In this paper, we address this issue by demonstrating the shared epistemological foundations of configurative reviews, Hans-Georg GADAMER's hermeneutics, and reflexive thematic analysis—namely, a non-foundationalist stance, ontological idealism, inductive reasoning, iterative processes, and a qualitative-interpretative orientation. Building on these commonalities, we propose an epistemic framework to support the coherent integration of these methods' procedures, principles, and rationales, thereby providing a structured basis for advancing qualitative research.

Key words: systematic reviews; configurative reviews; hermeneutics; reflexive thematic analysis

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. Configurative Systematic Reviews

3. GADAMER's Philosophical Hermeneutics

4. Reflexive Thematic Analysis

5. An Epistemic Integration Framework for Configurative Reviews

6. Concluding Thoughts

In systematic reviews (SR), which are characterized as a documentary method (TIGHT, 2019), it is typically recommended that researchers follow a strict protocol for searching, selecting, appraising, and synthesizing a body of literature (WANYAMA, McQUAID & KITTLER, 2021). In simple terms, this method involves a process "[...] for identifying, evaluating, and interpreting all relevant available research for a specific research question, topic area, or phenomenon of interest" (KITCHENHAM & CHARTERS, 2007, p.3). The protocol encompasses a focused research question, clearly defined objectives, explicit criteria for literature searches, agreed-upon inclusion and exclusion criteria, and the critical assessment and synthesis of findings from documents1) (PATI & LORUSSO, 2018). [1]

Systematic reviews adhere to a structured protocol that aligns with specific methodological stages and guidelines, thereby enhancing the understanding of phenomena while ensuring scientific rigor (KUTSYURUBA, 2023). The protocol is regarded as a standardized procedure, renowned for its replicability, transparency, objectivity, and methodological robustness (TIGHT, 2019). The rationale and methodological procedures intended for the review process are systematically presented in this protocol. PATI and LORUSSO (2018) observed that traditional systematic review protocols are typically designed to address a single research question, rely on a single type of study, and employ a single method of synthesis. In recent years, many scholars have explored the integration of various research methods within the analytical procedures of SR. PATI and LORUSSO, as well as SAUER and SEURING (2023), illustrated efforts to merge research methods in systematic reviews. [2]

According to SAUER and SEURING, researchers who developed SR protocols frequently failed to provide an epistemic justification for integrating diverse research approaches, often offering limited reasoning or insufficient supporting evidence. In many cases, authors neglected to articulate the epistemic rationale underlying the combination of methods within systematic reviews. Scholars were indiscriminately blending methods without understanding how different research methods can be epistemologically combined to undertake a systematic review (AMJAD, KORDEL & FERNANDES,2023; HARDEN & THOMAS, 2005). We identify three significant consequences of neglecting this issue: 1. The absence of a solid epistemic foundation to support the use of multiple methods; 2. difficulties in understanding how knowledge is acquired and derived from SR analysis; and 3. as a result, the trustworthiness of the knowledge produced remains unverified. [3]

In this article, we do not aim to provide an all-encompassing solution for epistemically justifying mixed methods, nor do we advocate for the amalgamation of all qualitative methods within SR. Our intention is modest yet ambitious. The purpose of this paper is twofold: First, we seek to demonstrate that configurative systematic reviews, Hans-Georg GADAMER's philosophical hermeneutics, particularly as articulated in his seminal work "Truth and Method" (2004 [1960]), and the guidelines of reflexive thematic analysis, developed by Virginia BRAUN and Victoria CLARKE (2013), are grounded in a shared epistemic foundation. Our argument is that this premise underpins the potential blending of these methods We characterize the approaches as rooted in a non-foundationalist perspective and ontological idealism, marked by the use of inductive reasoning and an iterative process, and situated within the qualitative-interpretative research tradition. In doing so, we further elucidate that these methods rest upon the recognition of multiple realities, encourage deep reflection, foster openness to emergent insights, and maintain a sustained emphasis on the significance of contextually meaningful experiences. Second, we set forth a theoretical framework to support the coherent integration of these methods' procedures, principles, and rationales, thereby aiming to provide a structured cornerstone for the advancement of qualitative research. [4]

The value of integrating these methods in social science research is underscored through the presentation of three key arguments. We interpret this blending as a response to concerns raised by DENZIN and LINCOLN (2018, p.14) regarding the prevailing "anything goes" attitude in critiques of qualitative research. Drawing upon this attitude, researchers have at times applied methods or techniques indiscriminately, leading to findings that lack a robust grounding in established paradigmatic foundations, namely ontological, epistemological, methodological, and axiological considerations (GOBO, 2023). Our proposal counters the idea that qualitative research is overly flexible and subjective, advocating instead for a structured approach that promotes methodological rigor and critical reflection. It ensures that research stemming from the combination of these methods will be credible, trustworthy, and relevant for understanding social phenomena. [5]

Systematic reviews can be conceived as a hermeneutic process, as suggested by GREENHALGH, THORNE and MALTERUD (2018). Here, we reinforce the adoption of hermeneutics as both a philosophical framework and a methodological rationale for conducting SR. Hermeneutic principles are grounded in sustained engagement with a body of literature, allowing for more profound understandings to emerge gradually over time, as observed by BOELL and CECEZ-KECMANOVIC (2014) and GREENHALGH et al. (2018). Researchers drawing on hermeneutics may access interpretative insights that may not be typically attainable through systematic reviews alone, thereby enriching the depth of qualitative research and informing review processes (BRISCOE, MELENDEZ-TORRES, SHAW & COON, 2025). [6]

Reflexive thematic analysis provides Gadamerian hermeneutics with a set of methodological tools for operationalizing its philosophical principles, as we aim to demonstrate through our proposed framework. In "Truth and Method," GADAMER (2004 [1960]) did not present a method for applying his hermeneutic tenets within qualitative research (GILLO, 2021; VAN LEEUWEN, GUO-BRENNAN & WEEKS, 2017). Researchers bear the responsibility of developing methods to practice hermeneutics in a way that remains faithful to its principles (BRISCOE et al., 2025; BYRNE, 2001; WEBBER, DHALIWAL & WONG, 2023). These tools constitute a practical means for social scientists to apply hermeneutics in the analysis of social phenomena (BYRNE, 2022). [7]

In addition to this introduction, the article is structured into four main sections. In Section 2, we explain the configurative systematic review, a type of systematic review epistemically aligned with Gadamerian hermeneutics. We introduce GADAMER's philosophical hermeneutics in Section 3. The notion and phases of reflexive thematic analysis are outlined in Section 4. Together, these three sections provide a foundation for justifying and facilitating the integration of these methods. In Section 5, we present the epistemic framework and explain how its components can be combined coherently. [8]

2. Configurative Systematic Reviews

The configurative systematic review (CSR) is a specific form of systematic review method (GOUGH & THOMAS, 2017). In a manner consistent with other systematic reviews, researchers adhere to several key elements when conducting a CSR approach: 1. A predefined protocol; 2. a clearly articulated purpose; 3. a well-formulated research question; 4. established search strategies; and 5. predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Additionally, CSR entails a qualitative appraisal of the reviewed documents. This appraisal involves a nuanced analysis of the quality and relevance of the literature, taking into account factors such as research design, methodology rigor, and the credibility of the authors. Researchers incorporated these factors to promote transparency and reduce biases throughout the review process (JESSON, MATHESON & LACEY, 2011; SURI & CLARKE, 2009). The objective of a CSR is to identify, examine, and synthesize existing evidence on a particular theme or phenomenon through a comprehensive and exploratory approach that considers all relevant aspects. [9]

The CSR is consonant with interpretative methods and qualitative research traditions (EIKELAND & OHNA, 2022; OLIVER & TRIPNEY, 2017). Configurative reviews are underpinned by a relativist–idealist stance (GOUGH, THOMAS & OLIVER, 2012), one that prioritizes the collaborative construction of shared meaning. This review approach is designed to support the exploration of variations and complexities inherent in different conceptualizations, rather than to yield a singular or definitive answer. Researchers adopting CSR are particularly well-positioned to identify and analyze patterns arising from conceptual diversity (GOUGH & THOMAS, 2017), without the aim of exhaustively examining all available evidence on a given phenomenon (EIKELAND & OHNA, 2022). As GOUGH et al. (2012) noted, CR constitutes a means by which researchers contribute to knowledge through the process of theorization. Typically, this form of review is employed to clarify existing concepts or to develop new ones, with the aim of offering “enlightenment through novel ways of understanding” (p.3). Configurative reviews are employed to organize and interpret information with the aim of advancing theoretical understanding and generating conceptual insights into phenomena. In this regard, researchers use CSR to enhance awareness of an existing phenomenon and its novel manifestations, without the explicit intention of substantiating an a priori empirical claim. [10]

Although its underlying methodology is often "[...] determined (or at least assumed) [...]" in advance (ibid.), the CSR approach retains an exploratory character to address the intricacies in investigating social phenomena (ARMSTRONG, BROWN & CHAPMAN, 2020). CSR is premised on "[...] the assumption that the phenomena being studied [and reality] are multifaceted in nature" (LEVINSSON & PRØITZ, 2017, p.213). This type of review is notably advantageous for engaging with a complex and diverse body of literature, as GOUGH et al. (2012) claimed. Different approaches to studying the same issue may yield distinct interpretations of a phenomenon; hence, positioning configurative reviews as an effective tool for in-depth analysis (LEVINSSON & PRØITZ, 2017). Generally, CSR is conducted as an interpretive analysis, where concepts, their meanings, and contexts serve as the data under scrutiny (GOUGH & THOMAS, 2017). The purpose of this method is to produce a meaningful configuration that strengthens and deepens the interpretation of the phenomenon in focus (LEVINSSON & PRØITZ, 2017). [11]

The methodological design of CSR incorporates an iterative approach as a fundamental rationale (EIKELAND & OHNA, 2022; GOUGH et al., 2012). The procedures of configurative reviews are characterized by flexibility and circularity, allowing for continuous adjustments as the research progresses, whether by modifying or selecting appropriate methods (GOUGH & THOMAS, 2017). The stages of the review frequently overlap and influence one another, producing a circular process of inquiry in which evidence is interpreted through a back-and-forth movement (LEVINSSON & PRØITZ, 2017). For example, literature searches may need to be conducted in multiple cycles. Moreover, the processes of quality assessment and synthesis are closely interlinked, as the value of any individual study becomes clearer when considered in relation to others within the research corpus2). [12]

GOUGH et al. (2012) underscored that configurative reviews employ an inductive logic. Specifically, we propose that this type of review is guided by an "inductive bottom-up approach" (SHEPHERD & SUTLIFFE, 2011, p.361). This approach derives knowledge from "[...] empirical experience based upon a system of handling [...] data" (p.363). Inductive reasoning begins with the intersection of the researcher's general curiosity and the available raw data (ibid.). This intellectual curiosity plays a pivotal role in theorization, even when it does not translate into elaborating detailed questions or methods, especially when the data are allowed to speak for themselves. Adopting this perspective often involves cultivating an "unknowing" attitude, marked by openness and receptiveness to ideas, thus enabling theory to emerge from the data. The inductive reasoning inherent in CSR is intended to advance theory and introduce original viewpoints. [13]

Configurative Reviews are not wholly inductive but display a partially inductive orientation. As GOUGH et al. (2012, p.4) stressed, the method "[...] may include some components where data are aggregated.” The interpretations are derived either from "the emerging literature" or "through a sampling framework based on an existing body of literature" (p.3). Researchers conducting a CSR organize data across the included studies and aspire to produce new knowledge that transcends the sum of its parts (GOUGH & THOMAS, 2017). Theories are treated as heuristic tools, helping to contextualize findings, guide the interpretation of phenomena, and delineate empirical categories without imposing pre-established classifications. Throughout the review process, both theories and interpretations are subject to revision in response to emerging evidence (GOUGH et al., 2012). Within the configurative systematic review, researchers undertake a rigorous synthesis of findings from multiple studies, facilitating the generation of a cohesive and substantive interpretation of the existing research evidence (LEVINSSON & PRØITZ, 2017). [14]

Grasping the contextual background of a document is essential for its interpretation within configurative reviews. As BOWEN (2009) pointed out, inductive reasoning in CSR is informed by the theoretical framework within which a phenomenon is situated. Informed by the existing literature, researchers use this framework to guide the initial stages of investigation and to establish a valuable foundation for subject-matter analysis. Scholars draw on evidence from documents to enrich their interpretations, prioritizing the depth of the research process over solely relying on pre-existing concepts or theories (BRAUN, CLARKE & HAYFIELD, 2015). Having outlined the defining characteristics of configurative reviews, the following section turns to the principles of GADAMER's philosophical hermeneutics which guided our approach to document interpretation and informed our theoretical framework. [15]

3. GADAMER's Philosophical Hermeneutics

Philosophical hermeneutics constitutes one of the principal traditions within the broader field of hermeneutic thought. It is primarily concerned with the nature of meaning, understanding, or interpretation (MASON & MAY, 2020). This school of thought grapples with the fundamental challenge of determining how to attain objective interpretation, given that all meaning is inevitably mediated through the subjectivity of at least one interpreter (BLEICHER, 1980). Its principal subject of inquiry is the interpretative process, with the objective of delineating practices that remain faithful to its multifaceted nature (MALPAS, 2015). Through this process, philosophical hermeneutics enables transparency in interpretation, contributing to more reliable determinations of meaning. [16]

This school of hermeneutics focuses on examining the conditions that facilitate understanding, particularly within the context of individuals’ ongoing projects, purposes, and the interrelations they entail (BARRETT, POWLEY & PEARCE, 2011; MYERS, 2016). Philosophical hermeneutics involves a careful analysis of human understanding through the interpretation of language and its various modes of textual3) expression, situated within the specific contexts of their production (MASON & MAY, 2020; TOMKINS & EATOUGH, 2018). In essence, the objective of such hermeneutics is to clarify the interpretive circumstances under which the comprehension of a given phenomenon emerges (MALPAS, 2015). Researchers adopting a hermeneutic approach endeavor to uncover the meanings embedded in a phenomenon by attending to its linguistic, social, cultural, and historical contexts, thereby deepening their understanding of the world and human experience (CROTTY, 1998). [17]

In this article, we adopt the view that hermeneutics is a qualitative research method closely aligned with the interpretivist tradition (BARTLEY & BROOKS, 2023). Throughout the discussion, we aspire to demonstrate that the epistemological foundation of Gadamerian hermeneutics (i.e., GH) is methodologically compatible with the philosophical underpinnings of configurative review and reflexive thematic analysis (BARRETT et al., 2011; LINDÉN & ČERMÁK, 2007). GH represents a distinctive strand within the broader tradition of philosophical hermeneutics (MALPAS, 2015). It is informed by an interpretivist rather than an objectivist orientation (BARTLEY & BROOKS, 2023; VLĂDUŢESCU, 2018). As CONNOLLY and KEUTNER (1988, p.17) observed, understanding a text "[...] is not simply there, its true nature waiting to be discovered: it must be constructed in the process of reading." GADAMER (2004 [1960]) challenged the notion of a single, correct, definitive interpretation, emphasizing the ongoing and dialogical nature of the interpretive act. Meaningful engagement with a text presupposes acknowledging the intersubjective dimension of understanding and fostering thoughtful interaction with its content (GADAMER, 2005 [1977]). [18]

Gadamerian hermeneutics offers a distinctive non-foundationalist perspective within social sciences (HEKMAN, 1984). In "Truth and Method," GADAMER (2004 [1960]) reconfigured the positivist-interpretive dichotomy by proposing that understanding arises through the fusion of the interpreter's horizon with that of the text. He contended that all interpretation is inevitably shaped by prejudice and prior judgments (HEKMAN, 1984). He contested the epistemological centrality of the knowing subject, a foundational tenet of interpretive social science (HEKMAN, 1984), and rejected the idea that the meaning of a text is governed either by the interpreter's subjective impressions or solely by the author's original intentions (GADAMER, 2005 [1977]). GH legitimizes the fusion of both horizons as an integral part of the interpretation process (BARTLEY & BROOKS, 2023). The strict demarcation between the interpreter and the object stands in opposition to GADAMER's ontological and epistemological commitments, particularly the co-constitutive nature of reality and the fusion of horizons (PATTERSON & WILLIAMS, 2002). [19]

GH encompasses more than a methodological approach; it embodies a dynamic constellation of principles that guide humanity's pursuit of truth through the complexities of language, as articulated by GADAMER (2004 [1960]). From his perspective, language is an essential component of understanding. It holds a pre-interpretative status, shaping an individual's comprehension of the world even before conscious interpretation takes place (FREEMAN, 2007). As its core, every act of interpretation is mediated by language (GADAMER, 2004 [1960]). One's experiences of historicity, temporality, and existence in the world are grounded in, and constituted through, language (GADAMER, 2005 [1977]). He emphasized that the world is not self-evident; instead, it requires interpretation to be understood. In this process, language serves as a mediator between the finitude of humanity's historical existence and the world itself. Language facilitates self-understanding and individuals' interactions with others, thereby revealing itself as a universal ontological structure. Consequently, language becomes a crucial medium through which the truth of phenomena is disclosed, affirming that truth is inextricably bound to linguistic expression (GADAMER, 2004 [1960]). [20]

From the Gadamerian perspective, interpretation emerges only after the acquisition of language. As emphasized by VLĂDUŢESCU (2018), interpretation assumes a pivotal role in the GH. It begins, according to GADAMER (2004 [1960], p.298), "when something addresses us," thereby suggesting that the interpretive process is initiated when individuals are summoned or interpellated by something that calls them to understanding. For GADAMER, grasping a text's meaning necessitates the internalization of its significance; that is, individuals must construct their interpretations of the things manifested in the world. A primary criticism directed at his hermeneutics concerns its allegedly excessive subjectivity and relativism (REGAN, 2012). This raises a pertinent question: How might one avoid succumbing to pure relativism, given individuals' inherent subjectivity involved in all acts of interpretation? [21]

GADAMER (2004 [1960]) responded to such a critique by addressing a central concern in his hermeneutic system: The truthfulness of interpretation. He rejected the notion that a text possesses a single, fixed horizon of truth, positing instead that it unfolds multiple interpretative horizons (KERR, 2020). Following the Gadamerian approach, "[t]he ways to understand are not about control and manipulation but about involvement and openness, not just knowing but experiencing, not following a strict method but engaging in dialogue" (PALMER, 1969, p.216). Given that fully apprehending the author's original intent is often unattainable, interpretation is conceived as a dialogical engagement between the interpreter and the text, ultimately culminating in a fusion of horizons (BARTLEY & BROOKS, 2023). GH thus provides a framework for understanding how interpreters come to perceive reality and construct knowledge, influencing their preliminary assumptions about a given subject matter. [22]

Departing from the principles of objectivism, GADAMER (2004 [1960]) argued that the acts of understanding reality and of uncovering a truth from it emerge through the fusion of horizons. His concept of the horizon serves as a metaphor for perception and interpretation (KERR, 2020; LINDÉN & ČERMÁK, 2007; SIMMS, 2015), referring to "the range of vision that includes everything that can be seen from a particular vantage point" (GADAMER, 2004 [1960], p.301). The epistemic horizon underscores the contextual nature of knowledge and highlights the openness and fluidity inherent in both the interpreter's and the text's horizons (BARTLEY & BROOKS, 2023; PALMER, 1969). [23]

The essence of dialogue resides in the dynamic interplay of questioning and answering between horizons (GADAMER, 2004 [1960]; see also FREEMAN, 2011). The Gadamerian notion of dialectical interaction represents the reciprocal process of inquiry between the interpreter and the text (LINDÉN & ČERMÁK, 2007; MASON & MAY, 2020). GADAMER (2004 [1960], p.370) posited that dialectic "makes understanding appear to be a reciprocal relationship of the same kind as conversation." Dialogue fosters an ongoing, integrative experience and interpretive engagement (BARRETT, GOLDSPINK & ENGWARD, 2022), enabling interpreters to expand their horizons through engagement with the text (GADAMER, 2004 [1960]). He asserted that "[i]t is true that a text does not speak to us in the same way as does a Thou. We who are attempting to understand must ourselves make it" (p.370). [24]

The core premise of the Gadamerian dialogue lies in the broadening of the interpreter's horizon through interaction with the text (GADAMER, 2005 [1977]). The interpreter's initial perspective may evolve through the process of questioning and responding, thereby revealing new horizons (BARTLEY & BROOKS, 2023; SIMMS, 2015). The interpreters expand their horizons by integrating their context and historical standpoint into the text's horizon. Through the fusion of horizons, interpreters are prompted to remain open to change, a stance that not only influences their comprehension of the text but also simultaneously reconfigures the perceived horizon of the text (ibid.; see also REGAN, 2012). Such a fusion is regarded as providing legitimacy to the interpreter's conceptual framework whilst acknowledging the constitutive influence of the text itself (VLĂDUŢESCU, 2018). [25]

As GADAMER (2004 [1960]) contended, truth arises from the fusion of horizons, which remains temporary and contingent on a particular horizon. Dialogue thus facilitates the unfolding of truth rather than embodying it in itself, transcending the confines of any singular methodological approach (LINDÉN & ČERMÁK, 2007). For GADAMER (2005 [1977]), truth is not a method, but rather the outcome of dialogic engagement (REGAN, 2012). Interpretation is conceived as an ongoing dialogue, wherein provisional meanings are subject to scrutiny and continual redefinition in light of the encounter with alternative horizons (GADAMER, 2005 [1977]). [26]

In a dialogue, GADAMER (2004 [1960]) emphasized that any interpretation must acknowledge the tradition, historicity, and preconceptions embedded in both the interpreter and the text. If all interpretations can be articulated and are grounded in personal experience, then the knowledge derived from such experience may be subject to verification (ibid.). He claimed that true propositions emerge from the understanding of certain and recognized statements, as informed by the principle of "historically effected consciousness" (p.336). This mode of consciousness delineates the conditions under which comprehension occurs, as it requires the recognition of the authority of tradition (TATIEVSKAYA, 2012). [27]

For GADAMER (2005 [1977]), interpretation constitutes a form of cognition of truth that is grounded on tradition. Tradition serves as a benchmark for comprehending correctness (TATIEVSKAYA, 2012). It conveys the interests, cultural norms, preconceptions, questions, and concerns that influence interpretations and contribute to the development of knowledge (KERR, 2020; REGAN, 2012). Importantly, he did not endorse a conservative or uncritical stance toward tradition, nor did he advocate for its wholesale affirmation. While GADAMER (2004 [1960]) recognized that interpreting the world independently of tradition is unattainable, he simultaneously rejected any thoughtless attitude to it. Instead, tradition provides the means through which it may be examined, interrogated, and refined (PALMER, 1969). [28]

Similar to tradition, historicity acts as the bedrock and prerequisite for knowledge. It is an essential component in shaping people's understanding of both the world and themselves (GADAMER, 2004 [1960]). In his philosophical hermeneutics, the question of truth necessarily entails considerations of historicity (KERR, 2020). Individuals' historical situatedness and lived experiences inform interpretations, thus influencing how they comprehend texts (SIMMS, 2015). GH effectively creates novel interpretations and questions prevailing conceptualizations of phenomena, acknowledging that "things" are inseparably interwoven into the historical and temporal contexts (HEKMAN, 1984). [29]

Tradition encapsulates an "effective historical consciousness" forged within a linguistic community (GADAMER, 2004 [1960], p.337). Interpretation renders a specific subject intelligible within the boundaries of a given horizon, while preserving its distinctive significance (REGAN, 2012). The fusion of horizons inevitably occurs in the act of interpretation (BARTLEY & BROOKS, 2023). Understanding implies both interpreting the past and relating the text to the interpreter's present situation (GADAMER, 2004 [1960]). Tradition mediates the formation and transmission of meaning over time. Individuals' actions and expressions can only be adequately comprehended within their contextual frameworks. Interpretation presupposes prior knowledge or expectations concerning the subject matter of the text (ibid.). Praejudicium is recognized as an indispensable and intrinsic condition of understanding within GH (BHATTACHARYA & KIM, 2020; FREEMAN, 2007). This condition persists as a prior concept, even after the interpreter has engaged reflectively with the text (BARTLEY & BROOKS, 2023; VLĂDUŢESCU, 2018). Praejudicium refers to preconceived judgments, assumptions, biases, and prejudices inherited from either positive or negative traditions (BHATTACHARYA & KIM, 2020; GADAMER, 2004 [1960]). These preconceptions are not shaped solely by the interpreter's preferences and inclinations, but are also deeply rooted in both tradition and historicity (FREEMAN, 2007). [30]

GADAMER (2004 [1960], p.298) claimed that a primary objective of hermeneutics is to differentiate "the true prejudices, by which we understand, from the false ones, by which we misunderstand." Suspending praejudicium, he asserted, is indispensable for comprehending a text's meaning. This suspension does not imply "bracketing" one's prejudices and preconceptions but rather an acknowledgment of one's historicity (ibid.). During textual analysis, interpreters shape the meaning of a text; hence, recognizing their praejudicium is crucial for understanding the influence it exerts on their interpretations (BARTLEY & BROOKS, 2023). This acknowledgment highlights two limiting conditions in textual interpretation: 1. The impossibility of approaching a text with a completely innocent and neutral mindset; and 2. the impracticality of fully apprehending the text's horizon (PATTERSON & WILLIAMS, 2002). Consequently, interpreters are required to reflect upon their praejudicium by acknowledging these constraints (GADAMER, 2004 [1960]). Such critical engagement between the interpreter and the text is indispensable for fostering a meaningful hermeneutic dialogue (LINDÉN & ČERMÁK, 2007). [31]

GADAMER (2005 [1977]) underscored the significance of context in textual interpretation, characterizing the interpretive process as a circular movement, that is, "a movement back and forth between parts and whole" (BARRETT et al., 2011, p.184). This dynamic, known as the hermeneutic circle, is a fundamental ontological element of his hermeneutical approach (GRONDIN, 2016). In his magnum opus "Truth and Method," GADAMER drew upon HEIDEGGER's conception of the hermeneutic circle to explore what it means to be human in the world (REGAN, 2012). Although firmly situated within the Heideggerian paradigm and embracing the ontological turn in hermeneutics, GADAMER investigated the nature of understanding qua understanding (HABERMAS, 1986). In doing so, he introduced the notions of the fusion of horizons and dialogue as a question-and-answer interaction between the whole and its parts, situated within the framework of the Heideggerian hermeneutic circle (GADAMER, 1988). [32]

In a manner akin to HEIDEGGER, GADAMER employed the metaphor of the hermeneutic circle "to describe the experience of moving dialectically between the part and the whole" (KOCH, 1996, p.176). This circle reflects a dialectical interplay in which the text is understood as a "whole in light of its parts," and the parts are interpreted "in light of the whole" (LINDÉN & ČERMÁK, 2007, p.45), with interpretations being informed by foreseen elucidations (GADAMER, 1988). The hermeneutic circle symbolizes a collaborative, cyclical, iterative, dynamic, and interpretative process in which interpreter and text converge, culminating in the fusion of horizons (PATTERSON & WILLIAMS, 2002). As he articulated, this circle is "a circular relationship in both cases. The anticipation of meaning in which the whole is envisaged becomes actual understanding when the parts that are determined by the whole themselves also determine this whole" (GADAMER, 2004 [1960], p.291). Such a process deepens the interpreter's comprehension of the text (BARRETT et al., 2022). [33]

Within the hermeneutic circle, understanding a text requires the interpreter to grasp both its totality and its constitutive elements, thereby establishing a reciprocal and continuous relationship between the whole and its parts (ibid.; see also GADAMER, 1988). Assertions concerning the overall meaning of the entire text are substantiated through an understanding of its individual components (BARTLEY & BROOKS, 2023), as each element derives support and validation from the overarching structure of the whole (CROTTY, 1998). In accordance with the logic of this circle, each interpretation presupposes a dynamic oscillation between envisaging the text's overall significance and interpreting its specific passages (GADAMER, 1976). [34]

The part-whole dialectic refers to the harmonization of discrete interpretations with broader, anticipatory frameworks and is vital to effective communication. GADAMER (2004 [1960]) emphasized that social scientists ought to begin with a holistic interpretation of a text's meaning. Through critical introspection, interpretations may be refined and further elaborated. The hermeneutic process implies an evolving comprehension of the parts, accompanied by a speculative conception of the whole, which potentially reshapes the latter in light of more profound insights into the former (ibid.). Attaining a cohesive understanding requires both a detailed apprehension of the parts and an unwavering attention to the totality (BARTLEY & BROOKS, 2023). In the following section, we outline a detailed exposition of reflexive thematic analysis, exploring its alignment with the systematic literature review through a hermeneutic lens. [35]

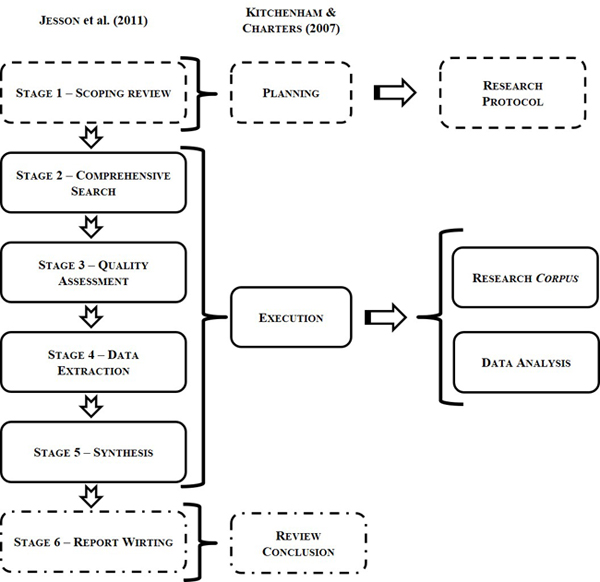

4. Reflexive Thematic Analysis

Reflexive thematic analysis (RTA) is a "theoretically flexible interpretative approach to qualitative data analysis that facilitates the identification and analysis of patterns or themes in a given data set" (BYRNE, 2022, p.1392). Its primary objective is to identify, organize, and interpret dominant patterns of meaning within a research corpus through textual analysis (BRAUN, CLARKE, HAYFIELD & TERRY, 2019). This analytic method is adaptable to a wide range of qualitative paradigms, without enforcing rigid theoretical assumptions, research questions, or specific data collection methods (CLARKE, BRAUN & TERRY, 2019). The RTA approach accommodates various philosophical orientations, foregrounding "researcher subjectivity, organic and recursive coding processes, and the importance of deep reflection on, and engagement with, data" (BRAUN & CLARKE, 2019, p.593). Such flexibility renders RTA particularly well-suited to diverse qualitative frameworks, enabling engagement with a plurality of ontological and epistemological perspectives (CLARKE et al., 2019; DE PAOLI, 2024). [36]

RTA encompasses a structured set of procedures to ensure rigorous and comprehensive engagement with the data (TERRY, HAYFIELD, CLARKE & BRAUN, 2017). The process comprises six phases: 1. Familiarizing with the data; 2. generation of codes; 3. construction of themes; 4. review of candidate themes; 5. definition and naming of themes; and 6. production of the report (BRAUN & CLARKE, 2006). It is worth underscoring that these phases ought to be conducted in an interactive, reflexive, and iterative fashion (ibid.; see also BRAUN, CLARKE, HAYFIELD & TERRY, 2017; CLARKE et al., 2019; DE PAOLI, 2024). [37]

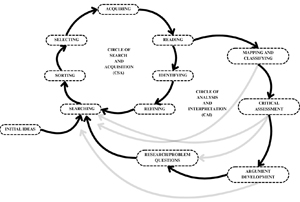

Familiarization "is about generating very early and provisional analytic ideas, and this requires being curious, and asking questions of the data" (TERRY et al., 2017, p.24). Its objective is to explore emerging ideas and identify potential connections related to the phenomenon within the data, without yet assigning formal categories (BRAUN & CLARKE, 2019). [38]

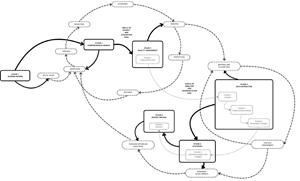

This phase requires researchers to undertake an initial engagement aimed at developing a comprehensive understanding of the research corpus (BRAUN & CLARKE, 2006). It encourages active reading, enabling scholars to discern patterns or distinctive features as they begin the preliminary analysis, rather than passively assimilating information (BRAUN et al., 2019). Through this process, researchers cultivate deep familiarity with the material, which supports the generation of more nuanced insights and a richer comprehension of the phenomenon under investigation (TERRY et al., 2017). Drawing from BRAUN and CLARKE (2020, p.331), four key strategies are central to this phase: 1. Reading the document multiple times; 2. jotting down initial thoughts; 3. identifying novel elements; and 4. formulating general questions regarding the document's intentionality. [39]

The second phase is coding. It is a systematic process of assigning clear and meaningful labels to data segments that are pertinent to the research question (TERRY et al., 2017). These segments comprise intelligible textual fragments that offer insights into specific aspects of the phenomenon (BRAUN et al., 2019). Coding should be open, recursive, and inclusive, with succinct labels applied across the dataset (BRAUN et al., 2015). Consequently, codes may evolve in their labeling or meanings, or even be discarded, reflecting the flexible and adaptive approach of the analytic process. Researchers may employ two distinct coding strategies within RTA: 1. Semantic (descriptive) coding; and 2. latent (interpretive) coding. [40]

Semantic coding is an organic, provisional, open-ended, interactive, and adaptable method of labeling that necessitates sustained engagement with the content of a given document (TERRY et al., 2017). This coding strategy captures explicit meanings embedded within significant segments of text, offering surface-level interpretations of the material under analysis (BRAUN et al., 2019). The primary aim of descriptive coding is to provide an overview of each segment, representing its meaning without yet establishing connections or patterns either within or across documents (PATTERSON & WILLIAMS, 2002). [41]

Upon completion of semantic coding, the subsequent step involves the latent coding of meaning units. These units typically consist of a set of significant sentences that convey comprehensive ideas concerning various dimensions of the phenomenon. They may range from specific conceptualizations to broader positions underpinned by interrelated claims (ibid.). A claim is defined as a statement that can be deemed true or false. Latent coding delves into the more abstract, conceptual, and implicit layers of meaning, capturing underlying ideas or assumptions that may not be overtly expressed in the text. CLARKE et al. (2019) recommended compiling a list of latent codes to systematically organize the data, facilitating the identification of patterns either within or across significant segments. This analytic process marks the conclusion of the second phase. [42]

As codes may evolve during the labeling process, they serve as the foundational elements in the development of themes (ibid.). In the third phase, researchers generate themes through a "productive, iterative, [and] reflective process of data-engagement," identifying systematic meaning clusters within the corpus (TERRY et al., 2017, p.27). Themes are abstract constructs organized around central concepts or codes (BRAUN et al., 2019; VAISMORADI & SNELGROVE, 2019). They encapsulate patterns of meaning, encompassing both explicit and implicit meanings across documents (BRAUN et al., 2019). At this phase, the analytical focus shifts from interpreting individual data items to understanding the aggregated meaning across the entire corpus (BYRNE, 2022). [43]

It is crucial to acknowledge that themes do not reside inherently within the data; instead, the researcher actively constructs them by combining, clustering, collapsing, or omitting codes to craft a coherent narrative for each theme. The commonalities shared among distinct codes facilitate their integration into potential themes or subthemes (ibid.; see also TERRY et al., 2017). Themes are categorized under thematic labels, which illuminate significant sections of the corpus by grouping diverse codes from various documents (VAISMORADI & SNELGROVE, 2019). These labels emerge from a detailed analysis aimed at generating aggregated and meaningful patterns across the coded data (BRAUN & CLARKE, 2012). [44]

Theme development is a subjective, thoughtful, and interpretive endeavor (VAISMORADI & SNELGROVE, 2019). Themes remain adaptable; they may be redefined or expanded to provide new perspectives and interpretations of the phenomenon (CLARKE et al., 2019). Themes may likewise be discarded if they fail to yield interpretative value or do not adequately address the research question (BYRNE, 2022). They should convey insightful understandings while retaining consistency and relevance in relation to the research objectives (BRAUN et al., 2015). A thematic map can assist in visualizing and conceptualizing emergent patterns among candidate themes, offering a depiction of "how different themes work together to tell an overall story about the data" (TERRY et al., 2017, p.28). Provisional thematic maps represent emergent themes and the organizing concepts that structure relationships across codes (ibid.; see also DE PAOLI, 2024). These maps furnish clarity regarding the connections between themes and the corpus as a whole, thus supporting a coherent interpretation of identified themes and subthemes (BRAUN & CLARKE, 2012). Additionally, thematic maps help prevent redundancy, thematic overlap, and inconsistencies among emerging candidate themes (BRAUN & CLARKE, 2006; VAISMORADI & SNELGROVE, 2019). [45]

The fourth phase presupposes a meticulous review and refinement of the provisional candidate themes and subthemes. It involves a critical appraisal of themes derived from the coded data items and the broader corpus to ensure a comprehensive and coherent understanding of the findings (BRAUN & CLARKE, 2020). In this process, referred to as a "quality control exercise" (TERRY et al., 2017, p.29), researchers ensure that the themes are faithfully grounded in individual data segments and resonate meaningfully with the corpus as a whole (BRAUN et al., 2015). Specific themes may require further refinement or be discarded, and the thematic map should be revised accordingly (BRAUN & CLARKE, 2013; VAISMORADI & SNELGROVE, 2019). Scholars review each theme to confirm its relevance and internal coherence, which in turn aids in constructing a compelling narrative aligned with the research question (BRAUN et al., 2019). [46]

The analytical narrative for each theme and subtheme is developed during the fifth phase, which entails defining and naming themes. This process prioritizes clarity, cohesion, quality, and analytical rigor of such a narrative (TERRY et al., 2017). The objective of this phase is "to move away from a summative position [...] to an interpretative orientation" (p.30), constructing a cohesive narrative that elucidates the nuances and variations in the meanings of themes (BRAUN et al., 2019). Clear and precise definitions of themes provide succinct summaries, ensuring conceptual consistency throughout the corpus (TERRY et al., 2017). The themes that endure this phase are retained as the permanent ones. At this phase, the synthesis process begins, confirming that the identified candidate themes effectively and succinctly capture the significant dimensions of the data (BRAUN et al., 2015). [47]

The final phase comprises the report, which narrates the overarching story emerging from the data analysis and articulates insights drawn from multiple documents. It also offers interpretations of the themes that directly address the research questions (BRAUN et al., 2019). Notably, the report is often drafted concurrently with the thematic analysis, reflecting the recursive nature of the process, wherein codes, themes, and interpretations develop and refine during the writing process (BYRNE, 2022). Furthermore, this phase delivers an interpretative synthesis of the entire corpus, identifies gaps in the literature, underscores pressing issues, and proposes directions for future research. In the subsequent section, we present a systematic framework for organizing and evaluating data within textual analysis, integrating configurative systematic review with Gadamerian hermeneutics and reflexive thematic analysis. [48]

5. An Epistemic Integration Framework for Configurative Reviews

The configurative review adheres to the structured framework established by JESSON et al. (2011, p.108). This process comprises six key stages: 1. Scoping review; 2. comprehensive search; 3. quality assessment; 4. data extraction; 5. synthesis; and 6. report writing. These stages align with the systematic review model proposed by KITCHENHAM and CHARTERS (2007), which is structured around three overarching phases: 1. Planning; 2. execution; and 3. conclusion. The sequential organization of these stages and phases is depicted in Figure 1. [49]

The first stage, referred to as the scoping review, corresponds to the planning phase. It is primarily concerned with the development of the research protocol, including the formulation of research questions, definition of search strategies, identification of relevant sources, specification of selection criteria, and quality assessment procedures. The execution phase encompasses Stages 2 through 5. Within Stages 2 and 3, several key activities are undertaken: 1. Conducting systematic searches across digital libraries; 2. applying inclusion and exclusion criteria to identify relevant publications; and 3. evaluating the quality of selected documents for subsequent analysis. The construction and analytical processing of the research corpus occur during Stages 4 and 5.

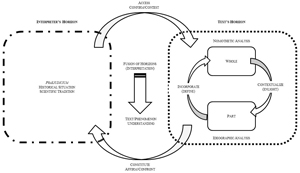

Figure 1: Stages of configurative reviews [50]

While JESSON et al. (2011) and KITCHENHAM and CHARTERS (2007) did not discuss corpus construction within the context of CR, we drew on the guidelines outlined by BAUER and AARTS (2000) to inform the methodological design of such reviews. These directives underscore the importance of representativeness, extensiveness, and relevance in corpus development. The selected documents are treated as raw data, analyzed to extract meaningful information about a given phenomenon, and to synthesize findings that respond to the review questions. In Stage 6, the focus shifts towards disseminating the findings, particularly the conclusions of the CR. [51]

The epistemic logic underpinning the CR is characterized as non-linear, iterative, reflexive, and partially inductive. This rationale aligns with the principles of Gadamerian hermeneutics and with the hermeneutic circles conceptualized by BOELL and CECEZ-KECMANOVIC (2014). These scholars described the analytical dynamics of hermeneutics as comprising two interrelated circles: 1. The circle of search and acquisition (CSA); and 2. the circle of analysis and interpretation (CAI). These circles, along with their constituent activities and interrelationships, are illustrated in Figure 2. The recursive nature of the hermeneutic process is conveyed through gray arrows, which represent the continuous "back-and-forth" movements both within and between the activities inscribed in each circle.

Figure 2: Hermeneutic circles (BOELL & CECEZ-KECMANOVIC, 2014, p.264). Please click here for an enlarged version of Figure 2. [52]

We employ these circles to connect the stages of the configurative review with GADAMER's hermeneutic philosophy. Accordingly, the circles were adapted to correspond with the six stages of the CR, thereby supporting its iterative nature. As noted by BOELL and CECEZ-KECMANOVIC (2014), understanding a document requires multiple iterations within these circles. The application of hermeneutic principles required the development of a data organization system to support textual analysis. The analytical procedures used to interpret the corpus followed the directives proposed by PATTERSON and WILLIAMS (2002), which were incorporated into the phases of RTA to guide the process of hermeneutic analysis. The systematic integration of RTA phases with CAI tasks was intended to enhance the methodological application of several Gadamerian principles and concepts. Two principles are particularly noteworthy: The "hermeneutic circle" and the "fusion of horizons." The integration of the RTA phases, the stages of the CR, and the hermeneutic circles within the proposed epistemic framework is illustrated in Figure 3. In this figure, the black boxes represent the six stages of the CR. The black arrows indicate the flow of these stages. The dark gray boxes correspond to the components of the CSA and CAI, while the dark gray dashed arrows depict the flow within these hermeneutic circles. The light gray boxes, situated within the black boxes, denote the RTA phases, and the thinner light gray dashed arrows represent the progression through these phases. [53]

Stage 1 of the CR begins with the generation of initial ideas and lays the foundation for the systematic review protocol. This stage is supposed to delineate the scope of the inquiry. Information derived from the analyzed documents at this stage provides the basis for formulating research questions, developing search strings, and establishing inclusion and exclusion criteria, quality assessment parameters, data extraction strategies, and analytical procedures for synthesis. Stage 1 occurs outside the hermeneutic circles and precedes the activities of the CSA. The protocol, along with its specific criteria and guidelines, determines the steps for progressing to Stage 2. [54]

Stage 2 takes place within the circle of search and acquisition, encompassing the full cycle of its constituent activities. They refer to searching, sorting, selecting, obtaining, reading, identifying, and refining relevant documents. The non-linear nature of the hermeneutic process permits shortcuts and flexible movements between CSA activities. Orientational reading directs the CSA activities by supporting the comprehension of the documents' content. In accordance with the guidance provided by BOELL and CECEZ-KECMANOVIC (2014), this reading mode is intended to cultivate a preliminary and holistic understanding of the phenomenon under study. Orientational reading may also indicate the need for further searches, thus enabling subsequent iterations of CSA activities and supporting the identification of previously overlooked documents. [55]

In the procedural and logical framework of the CSA, Stage 2 differs from Stage 1 in five key aspects: 1. The initiation point; 2. the objective; 3. the depth of analysis; 4. the analytical approach; and 5. the sequence of activities. Stage 2 commences with a search activity, during which the search strings developed in the previous stage are employed to retrieve documents from specific research databases, such as Scopus, Emerald, SpringerLink, and Web of Science. Following the search, the retrieved documents must be organized, a task referred to as the sorting activity. This activity involves structuring the results in a more manageable form, often by employing the ranking algorithms of the databases, which prioritize the most relevant documents at the top and the less relevant ones lower in the list. [56]

The subsequent activity involves acquiring the selected documents, which is accomplished by downloading them from the research databases for further analysis. All retrieved documents are read and categorized concurrently for analysis, reflecting the thorough nature of this stage. Studies are classified, according to defined inclusion or exclusion criteria, which guide the selection of relevant documents. Initially, researchers apply these criteria during the orientational reading of each study. Key textual components, such as the title, abstract, introduction, and conclusion, are scrutinized to determine a study's eligibility. However, when these elements do not provide sufficient clarity for classification, a full-text reading becomes necessary [57]

Additionally, Stage 2 supports the identification of new studies, terms, concepts, sources, authors, and documents pertinent to the research topic, thereby refining the search strategy. The reading process serves to enhance search methods by enabling the continual evaluation and improvement of document identification. This stage comprises searching, acquiring, reading, classifying, and selecting documents as part of its workflow. Further searches may become necessary during the reading and refinement processes. The construction of the research corpus is inherently dynamic, evolving as each relevant document is identified and added. Guided by specific criteria, the classification process in Stage 2 culminates in the selection of a refined subset of documents for subsequent analysis in Stage 3, thereby refining the initial search outcomes.

Figure 3: Integration of CR stages, RTA phases, and hermeneutic circles. Please click here for an enlarged version of Figure 3. [58]

Stage 3 operates within the circle of search and acquisition; however, unlike the preceding stage, it does not necessitate the full cycle of CSA activities. This stage begins with the analytical reading of the selected studies, each of which is subject to individual assessments based on predefined quality criteria. The objective of analytical reading is to interpret and attain a comprehensive understanding of each study's content. This reading enables a holistic apprehension of the documents, encompassing their focus, objectives, research questions, methodologies, conceptual and theoretical frameworks, empirical evidence, knowledge claims, and critical contributions (BOELL & CECEZ-KECMANOVIC, 2014). The familiarization phase of RTA unfolds during Stage 3 of the CSA, initiating interpretative engagement with the horizons of the documents through analytical reading, as illustrated in Figure 3. Familiarization culminates in an immersive reading experience designed to extract insights and establish a robust foundation for analyzing and interpreting the horizons of texts. During this phase, researchers play a pivotal role in exploring and shaping initial meanings that emerge from the interplay between their horizon and that of the documents. Stage 3 thus marks the onset of the fusion of horizons. The outcome of this stage is a refined selection of relevant publications, which will undergo further analysis in Stage 4, ultimately contributing to the development of the research corpus. Moreover, the third stage serves as the entry point to the circle of analysis and interpretation, paving the way for a more in-depth analysis and synthesis of the selected documents. It is essential to note that the six-phase process of RTA adheres to a circular approach of hermeneutic analysis, characterized by iterative movements between these phases. [59]

Within the context of the circle of analysis and interpretation, Stages 4, 5, and 6 unfold in a nonlinear fashion, allowing for flexible transitions and shortcuts between different activities. The mapping and classification activity in Stage 4 commences with the analytical reading of the final set of documents selected in Stage 3. This fourth stage is initiated through the individual reading of each document, followed by processes of comparison and contrast across the corpus. The purpose of this reading is to deepen the understanding of the material. Analytical reading is crucial for facilitating a robust and comprehensive critical evaluation. While the analytical process attends to the internal structures of each document and its interrelations, the critical assessment activity specifically interrogates the body of knowledge surrounding the phenomenon (BOELL & CECEZ-KECMANOVIC, 2014). The objective of critical assessment is to identify: 1. Lacunae within the existing literature; 2. neglected dimensions of a phenomenon; 3. inconsistencies and contradictions within individual studies and across sources; and 4. shortcomings in the previous scholarly treatments of the research problem. [60]

A critical assessment uncovers the underlying meanings within the documents and subjects them to thorough scrutiny. In doing so, new insights emerge that broaden the horizon of existing knowledge and challenge prevailing interpretations (BOELL & CECEZ-KECMANOVIC, 2014). Through this analytical activity, scholars can examine the soundness of the assumptions, arguments, and justifications articulated within the documents, with the objective of detecting and addressing novel perspectives and gaps pertinent to the research problem as outlined in the configurative review. The researcher's praejudicium plays a central role in guiding the activities of mapping, classification, and critical evaluation. The praejudicium assists in problematizing and recontextualizing the meanings embedded in the documents. These activities promote a dialogue engagement between the researchers' horizons and those of the texts, with the effect of broadening their intellectual perspectives and generating fresh insights within the evolving research corpus (BOELL & CECEZ-KECMANOVIC, 2014). [61]

The RTA phases of coding, theme development, and theme reviewing are situated within Stage 4 of the configurative review and are operationalized through the activities of the CAI. The second phase of RTA, corresponding to Stage 4 of the CR, entails the systematic assignment of codes to significant segments of the research corpus. These segments are regarded as individual parts and are grouped according to their shared meanings, thus facilitating the future organization of coherent thematic patterns. In accordance with the non-linear logic of hermeneutic inquiry, coding unfolds iteratively throughout the reading and analysis processes. Within the CAI, coding is enacted primarily through the activities of mapping, classification, and critical assessment. The coding process is partially inductive, aligning with both the methodological design of CR and the principles of hermeneutics. Stage 4 integrates both semantic coding and latent coding strategies. Orientational reading supports semantic coding, while analytical reading enables latent codification within the mapping and classification activities of the CAI. [62]

In accordance with Gadamerian hermeneutics, coding involves a dialogical engagement between the horizon of the research and that of the text. In this sense, coding embodies the rationale of the fusion of horizons. During Stage 4, the researchers' horizons, comprising their conceptual frameworks (that is, pre-understandings, traditions, and historical context), inform the selection of significant segments within the documents. Within the framework of the part-whole dialectic, these segments are constituent parts of the phenomenon's meaning, deriving from the text's context. As a code aggregates these segments, it represents a provisional whole of that meaning, foregrounding the researchers' openness to emergent insights from the text in the pursuit of a more profound understanding. [63]

The third phase centers on developing candidate themes and subthemes through the interpretive analysis of aggregated data from the coding process. In line with the Gadamerian notion of the fusion of horizons, themes (like codes) are conceived as interpretative, abstract constructs. In this regard, codes are the constituent parts of the phenomenon's meaning, while candidate themes represent a provisional whole. Subthemes, in turn, function as parts of the theme, which represents a whole in itself, reinforcing the part-whole dialectic. At this phase, a list of provisional themes is established, delineating the central organizational patterns that characterize significant aspects of the phenomenon and its various manifestations. Thematic labels serve as heuristic devices, supporting the recognition of meaningful patterns within aggregated codes. Provisional thematic maps are employed to organize the narrative implied by the candidate themes. These themes, as parts of the phenomenon's meaning, contribute to the construction of a new provisional whole articulated through the thematic map. The fourth phase involves a critical appraisal of the provisional themes and subthemes, leading to their refinement, reconfiguration, or eventual exclusion. [64]

Stage 5 builds upon the critical assessment initiated in Stage 4, focusing on synthesizing the content of the documents within the configurative review. This fifth stage involves a comprehensive analysis of existing knowledge, the processes of its acquisition and production, as well as methodological rigor and constraints articulated through the arguments presented across the selected documents. The fifth phase of the RTA, theme definition, is situated within Stage 5 of the CR. This phase marks the commencement of the synthesis process, refining the interpretation of the definitive themes that emerge from the critical assessment activity undertaken in the CAI. Theme definition adheres to a hermeneutic interpretative approach, ensuring the internal coherence and conceptual clarity of each theme. The culmination of Stage 5 lies in the development of analytical arguments through the careful organization and selection of specific themes and subthemes. Constructing an analytical narrative is instrumental in visualizing the core themes via a final thematic map. This narrative is intrinsically linked to the developing argument activity within the CAI, which underscores both the convergence and divergences in meanings across themes. Thus, it demonstrates how researchers interpret and synthesize insights through the fusion of horizons. The sixth and final phase of the RTA, reporting, corresponds to Stage 6 of the CR and culminates the CAI activity of generating new research questions or problematics, thereby paving the way for further scholarly inquiry. [65]

The epistemic proposition of integrating the RTA phases with CAI activities enhances the systematic application of Gadamerian principles, most notably the hermeneutic circle and the fusion of horizons. The RTA phases enable researchers to examine the dynamic interplay between parts and whole, thereby revealing the horizons inherent within the documents. The methodological application of these two principles in the analysis of the corpus adheres to the guidelines set forth by PATERSON and HIGGS (2005) and PATTERSON and WILLIAMS (2002). Please refer to Figure 4 for a visual representation of how these principles are implemented across the CR stages and RTA phases. [66]

Figure 4 illustrates the two horizons in the hermeneutic circle: 1. The interpreter's horizon (namely, the researchers' horizon, encompassing their praejudicium, historical context, and scientific tradition); and 2. the text's horizon (which reflects its scientific tradition, historical context, and the author's argument concerning the phenomenon). These horizons are represented as boxes with dashed lines, symbolizing that their boundaries are open and permeable rather than rigidly defined. The fusion of horizons denotes a dialogical process in which the researcher's horizon engages with and informs the interpretation of the text's meaning.

Figure 4: Dynamics of hermeneutic circles and the fusion of horizons. Please click here for an enlarged version of Figure 4. [67]

Implementing the hermeneutic method involves articulating the multiple facets of the researchers' praejudicium. The structure of understanding and conceptualization delineates the researchers' horizon, encompassing their preconceptions, prior assumptions, theoretical inclinations, and onto-epistemological positions. Together with the praejudicium, the researchers' historical context constitutes their historically situated consciousness of the phenomenon. Acknowledging the influence of this historical context encourages a critical reflection on interpretations that arise through the fusion of horizons. This structure of understanding and conceptualization underpins the analysis and synthesis of the research corpus. [68]

In the hermeneutic-interpretive tradition, the researchers' prior structure of understanding evolves through their engagement with the documents reviewed in Stages 1, 2, and 3 of the CR. This evolutionary structure gives rise to initial interpretations, supporting preliminary perspectives informed by relevant literature while remaining receptive to distinct aspects and emergent insights stemming from the epistemic horizon of the texts. Operating under the influence of this structure, the researchers' horizon accentuates specific issues while potentially overlooking others, mainly due to their praejudicium. Such a structure deepens the comprehension of the texts' horizon and elucidates how the documents articulate the phenomenon under study. In hermeneutics, interpretation unfolds as the horizon of the text is examined in concert with the researchers' evolving horizon. [69]

In light of hermeneutic circularity, a dialogue is guided by the dynamic relationship between the parts and the whole, which continuously informs and reshapes the understanding of the subject matter. Self-reflection proves essential in shaping the researchers' horizons throughout the research journey. Due to the multiplicity of possible interpretations of a phenomenon, a horizon acts as a pragmatic boundary, facilitating a focused inquiry into the more profound meaning that emerges through engagement with the text. Acknowledging the impossibility of encompassing all perspectives within a text's horizon underscores the inherently contextual and perspectival nature of knowledge. Such awareness brings to the fore essential considerations and inherent constraints when engaging with a document's horizon. Within the CR framework, historically situated horizons delineate the contours of understanding in relation to the context of a phenomenon. [70]

According to Figure 4, the fusion of horizons occurs when a researcher's horizon engages with that of the text during the reading process, revealing the praejudicium surrounding the phenomenon. This ongoing and evolving dialogue fosters critical questioning and opens pathways for interpreting the text's arguments and underlying assumptions. The researchers' interpretation is not merely a product of solipsism; rather, it is continually challenged and informed by the horizon presented within the documents. While researchers may attempt to impose their interpretations upon the text's horizon, the latter retains an inherent structure of meaning that resists such impositions. Achieving a profound understanding of the text's horizon is unattainable without reflexively engaging with the researchers' horizon, as such reflection is essential to its meaningful comprehension. The hermeneutic circle thus seeks to uncover the author's intent and to illuminate the horizon inscribed within the text. [71]

Through the hermeneutic circle, researchers engage with the part-whole dynamic, progressively refining their understanding of the phenomenon as it is interwoven into the document's content. In Figure 4, this dialectical interplay is manifested in the document's horizon. By analyzing the part-whole relationship, one attains a more nuanced understanding of the text's horizon and the phenomenon it represents. The CR comprises two cyclical phases of analysis. In the first phase, each publication is regarded as a self-contained entity, wherein the phenomenon is interpreted as an individual whole. Meaningful segments and units extracted from each document serve as its constituent parts. In the second phase, the research corpus is examined as a unified whole, enabling a more comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon. Each document is thereby perceived as illuminating a particular facet of the broader whole. The analysis unfolds in a recursive manner, oscillating between the individual parts of the documents and the collective corpus to construct a coherent and integrated interpretation of the phenomenon. Units of meaning, whether derived from singular documents or synthesized across the corpus, delineate the whole and provide contextual grounding for each component. This analytical process involves a meticulous examination of the individual elements before reassembling them into a structured and meaningful totality. [72]

Following the recommendations of PATTERSON and WILLIAMS (2002), the rationale underlying the part-whole relationship integrates both ideographic and nomothetic analyses. The ideographic approach centers on the detailed examination of individual parts, whereas the nomothetic analysis considers the whole at an aggregated level. This latter approach enriches the ideographic analysis by synthesizing multiple individual viewpoints to create a comprehensive picture of the phenomenon. The part-whole analysis begins with the interpretation of individual components, regardless of any discernible patterns that may exist. Afterwards, the nomothetic analysis identifies overarching themes or patterns that emerge from these components. Due to the cyclical nature of the part-whole relationship, the integrated insights derived from the nomothetic analysis provide a foundation for a deeper exploration of the constituent parts. This synthesized comprehension of the parts significantly informs the interpreter's initial perception of the whole, thus influencing their subsequent interpretation. Ultimately, the objective is to attain a nomothetic understanding of the phenomenon that transcends the isolated ideographic meanings of its components. [73]

The procedural logic of part-whole analysis is essential to reflexive thematic analysis, as it underpins all phases of the RTA process. Within the CR, analytical reading is guided by a hermeneutic rationale that integrates both ideographic and nomothetic levels of analysis. Individual readings and interpretations of documents highlight the distinct nature of the phenomenon as presented in each text. Critical evaluation further deepens the understanding of documents by applying these dual levels of analysis within the part-whole relationship inherent to the hermeneutic circle. From a hermeneutic perspective, optimal comprehension of meaningful units arises when they are placed within their proper contexts. To fully apprehend a text, the researcher must discern the interrelations among its parts and their integration into the whole. Reading affords access to the inherent understandings within and across documents, facilitating connections that underscore their significance within a broader context. This process highlights the uniqueness of each document, enabling a holistic interpretation of the phenomenon. [74]

This article was conceived to assist researchers in maintaining consistency and paradigmatic alignment throughout their investigations, thereby mitigating potential misapplications that may stem from insufficient knowledge or scientific imprudence. In doing so, it lays a foundational basis to address critiques directed at the often-cited "value-free" stance associated with qualitative research. We have endeavored to demonstrate that configurative reviews, GADAMER's hermeneutics, and reflexive thematic analysis share a common epistemological ground characterized by a non-foundationalist perspective, ontological idealism, inductive reasoning, iterative processes, and a qualitative-interpretative tradition. [75]

Beyond establishing epistemic congruence among these three methods, we have also delineated how they may be integrated processually, illustrating the intersections of their stages, phases, and guiding principles within the broader research process. A further contribution of this framework was to demonstrate how core principles of Gadamerian hermeneutics—specifically the hermeneutic circle and the fusion of horizons—can be operationalized within the CR e RTA, and potentially extended to other qualitative inquiries. [76]

In summary, the stages of configurative reviews align closely with the tenets of Gadamerian hermeneutics and, consequently, with the phases of reflexive thematic analysis. The partially inductive character of these methods supports the representation and analysis of textual data in qualitative-interpretivist research. These approaches foreground a data-driven, "bottom-up" process that constructs meaning directly from documentary data. These methods prioritize data analysis over a priori theoretical constructs, focusing on the identification of coherent clusters of meaning within texts. CR, GH, and RTA underscore the researcher's subjectivity and active engagement with knowledge production. This epistemic stance acknowledges multiple realities, embraces iterative analysis, fosters deep reflection, encourages openness to emergent insights, employs inductive reasoning, and highlights the importance of contextualized meaning. [77]

We would like to express our gratitude to the anonymous scholars for their time, expertise, and care in reviewing and responding to early drafts of this work.

1) Documents, whether printed or electronic, provide information or evidence (BOWEN, 2009; MORGAN, 2022), which substantiates the analysis and understanding of a phenomenon (DOLOWITZ, BUCKLER & SWEENEY, 2018). <back>

2) A corpus is a finite collection of materials chosen for specific research purposes (BAUER & AARTS, 2000). <back>

3) The term "text" holds a metaphorical significance within hermeneutics, extending well beyond its literal meaning (MASON & MAY, 2020). As MYERS (2016) noted, it encompasses not only written documents but also speech, images, symbolic representations, and diverse forms of human communication, both verbal or non-verbal. In essence, any artifact of meaning-making may be regarded as a text and subjected to interpretation in a manner analogous to that of written discourse. <back>

Amjad, Ayesha; Kordel, Piotr & Fernandes, Gabriela (2023). The systematic review in the field of management sciences. Organization and Management Series, 170, 9-35, http://dx.doi.org/10.29119/1641-3466.2023.170.1 [Accessed: May 18, 2025].

Armstrong, Paul W.; Brown, Chris & Chapman, Christopher J. (2020). School-to-school collaboration in England: A configurative review of the empirical evidence. Review of Educational Research, 9(1), 319-351, https://doi.org/10.1002/rev3.3248 [Accessed: May 18, 2024].

Barrett, Frank J.; Powley, Edward H. & Pearce, Barnett (2011). Hermeneutic philosophy and organizational theory. In Haridimos Tsoukas & Robert Chia (Eds.), Philosophy and organization theory (Vol. 32, pp.181-213). Bingley: Emerald.

Barrett, Lewis; Goldspink, Sally & Engward, Hilary (2022). Being in the wood: Using a presuppositional interview in hermeneutic phenomenological research. Qualitative Research, 23(4), 1062-1077, https://doi.org/10.1177/14687941211061055 [Accessed: January 04, 2024].

Bartley, Kevin A. & Brooks, Jeffrey J. (2023). Fusion of horizons: Realizing a meaningful understanding in qualitative research. Qualitative Research, 23(4), 940-961.

Bauer, Martin W. & Aarts, Bas (2000). Corpus construction: A principle for qualitative data collection. In Martin W. Bauer & George Gaskell (Eds.), Qualitative researching with text, image and sound: A practical handbook for social research (pp.19-37). London: Sage.

Bhattacharya, Kakali & Kim, Jeong-Hee (2020). Reworking prejudice in qualitative inquiry with Gadamer and de/colonizing onto-epistemologies. Qualitative Inquiry, 26(10), 1174-1183.

Bleicher, Josef (1980). Contemporary hermeneutics: Hermeneutics as method, philosophy and critique. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Boell, Sebastian K. & Cecez-Kecmanovic, Dubravka (2014). A hermeneutic approach for conducting literature reviews and literature searches. Communications of the Association for Information Systems, 34, 257-286, https://doi.org/10.17705/1CAIS.03412 [Accessed: September 12, 2023].

Bowen, Glenn (2009). Document analysis as a qualitative research method. Qualitative Research Journal, 9(2), 27-40.

Braun, Virginia & Clarke, Victoria (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77-101.

Braun, Virginia & Clarke, Victoria (2012). Thematic analysis. In Harris Cooper (Ed.), APA handbook of research methods in psychology (Vol. 2, pp.57-71). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Braun, Virginia & Clarke, Victoria (2013). Successful qualitative research: A practical guide for beginners. London: Sage.

Braun, Virginia & Clarke, Victoria (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 11(4), 589-597.

Braun, Virginia & Clarke, Victoria (2020). One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis?. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 18(3), 328-352.

Braun, Virginia; Clarke, Victoria & Hayfield, Nikki (2015). Thematic analysis. In Jonathan A. Smith (Ed.), Qualitative psychology: A practical guide to research methods (3rd ed., pp.222-248). London: Sage.

Braun, Virginia; Clarke, Victoria; Hayfield, Nikki & Terry, Gareth (2017). Thematic analysis. In Carla Willig & Wendy S. Rogers (Eds.), The Sage handbook of qualitative research in psychology (pp.17-36). London: Sage.

Braun, Virginia; Clarke, Victoria; Hayfield, Nikki & Terry, Gareth (2019). Thematic analysis. In Pranee Liamputtong (Ed.), Handbook of research methods in health social sciences (pp.843-860). Singapore: Springer.

Briscoe, Simon; Melendez-Torres, Gerardo J.; Shaw, Liz & Coon, Jo T. (2025). Framing systematic reviews commissioned by policymakers as a hermeneutic process: A methodological commentary. Methodological Innovations, 18(2), 114-126, https://doi.org/10.1177/20597991251329760 [Accessed: May 14, 2025].