Volume 26, No. 3, Art. 9 – September 2025

Mobile School Cartographies: A Methodological Tool for Exploring School, Urban, and Digital Mobilities With Youth

Guido García-Bastán & Horacio Luís Paulín

Abstract: This article is based on a research project in which we analyzed young people's school experience through the lens of the mobilities paradigm proposed by SHELLER and URRY (2006). Socio-educational scholars often regard as "school-related" only that which happens within the walls of educational institutions, promoting a fragmented view of youth experience. Our research goal was to explore mobilities in the sub-worlds of youth socialization that, in an intertwined manner, shape their school experience. To this end, we designed a qualitative methodological tool—based on cartographic work—called mobile school cartographies, tailored to capture youth mobilities through territorial, school and digital realms. Throughout this paper, we approach the tool's design and implementation process, providing details on the theoretical grounding that informed our decision-making. In the discussion section, we argue that this tool is useful to move towards an integrated approach of overlapping mobilities and to account for the diversity of youth experiences addressing certain limitations inherent in methodological approaches—such as surveys, biographical methods, or ethnographic studies—commonly adopted for investigating youth mobilities.

Key words: mobilities; youth; school experience; qualitative research; cartography

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. The Mobilities Paradigm as a Theoretical-Methodological Perspective for Studying Schooling Youth

2.1 Key concepts of the paradigm

2.2 Methodological approaches to youth mobilities

3. A Tool to Capture Youth Mobilities

3.1 The design process

3.2 Description of each session

4. Discussion and Conclusions

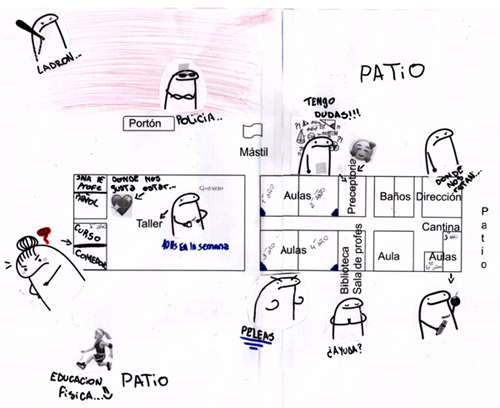

Appendix: Diversity of Students' Tackling Strategies During Workshop 1

In this article, we aim to present a methodological tool to address a range of issues concerning both the construction of study objects related to youth mobilities and the often fragmented methodological approaches used to study them. It is the result of a study carried out in the city of Córdoba, Argentina,1) in which we analyzed the youth school experience from a territorial and mobile perspective, i.e., "beyond the school gates" (SIMÓN, GINÉ & ECHEITA, 2016, p.37).2) From the beginning of our research, we sought to explore mobilities in the sub-worlds of youth socialization that, in an intertwined manner, produce their school experience. Put differently, we were interested in understanding the connections among youngsters' participation in different realms, and how these associations relate to characteristics assumed by their schooling process. [1]

Through the study of space, territory, and movement, alongside the mobilities turn, many scholars (CANZLER, KAUFMANN & KESSELRING, 2016; CRESSWELL, 2006; SHELLER & URRY, 2006, 2016) have framed mobility as a constitutive element of social practices. Thus, they challenged the ideas of space as merely a backdrop or "container" for these practices, emphasizing circulation and flows—both human and non-human—as inherent to the ontology of social life. [2]

Within our research field (socio-educational studies with adolescents and young people), assuming these premises highlight certain limitations of research, approaches traditionally are focused on processes that occur "within" school settings, and young people's experiences beyond the classroom were often overlooked (LEANDER, PHILLIPS & TAYLOR, 2010). While in recent decades mobilities came to be considered a key dimension in understanding social inequalities in contemporary capitalism (HENDEL, 2020; NAVARRETE, 2022; TAPIA, 2018), educational researchers still tend to interpret the school space or the classroom as a "container" (LEANDER et al., 2010, p.329), preventing its analysis in interaction with other areas of youth engagement. In other words, lay and academic perspectives often regard as "school-related" only what happens within the walls of educational facilities, promoting a fragmented view of the youth experience that is not conducive to exhibit the multiple constraints which affect their socialization (LAHIRE, 2007). [3]

Theoretical assumptions allowed us to identify a series of "territories" where youth mobilities occur: The urban landscape, educational facilities, and digital environments. We acknowledge that these are only analytically separable dimensions, as mobilities must be examined in their fluid interdependence. Thus, from the mobilities paradigm, we understand that places are connected to networks of relations, in the sense that no place can be considered as an "island" (SHELLER & URRY, 2006, p.209). Once this premise is accepted, we must overcome methodological challenges regarding the construction and exploration of our study objects. [4]

Methodological reconstruction and a range of methods play a key role in approaching new phenomena and understanding diverse perspectives and social experiences (DENZIN, 1994; VASILACHIS, 2009). To this end, we developed a tool called mobile school cartographies, a participatory approach to capture different "layers" of youth mobilities. [5]

The paper is organized as follows: First, we review the central premises of the mobilities paradigm to clarify some of the discussions underpinning our understanding of youth mobilities. We also refer to some issues concerning methodological approaches commonly adopted to investigate youth mobilities (Section 2). After that, we describe the development of the tool and illustrate the quality of the data it helped generate (Section 3). Finally, in the discussion (Section 4), we reflect on the tool's strengths and limitations to encourage its use in future research. [6]

2. The Mobilities Paradigm as a Theoretical-Methodological Perspective for Studying Schooling Youth

2.1 Key concepts of the paradigm

Space has been a traditional topic of interest to social thinkers. In the 1970s, scholars of the spatial turn structured a series of concepts and methods into a model suitable for operationalization in research. LEFEBVRE (1991 [1974]), for example, considered space as a constitutive element of collective life, rather than merely a static framework of it. His concept of "The Right to the City" (LEFEBVRE, 1969 [1968]) became an early reference to the close relation between urban design and the production of social inequalities, which now seems self-evident. [7]

At the dawn of this century, proponents of the then-new mobilities paradigm (SHELLER & URRY, 2006) also challenged the "immobile" mode adopted by many social scientists. They introduced a transdisciplinary framework for integrating mobilities as key factors in understanding the inequalities produced by "politics of mobility" (CRESSWELL, 2010, p.17) and "geographies of power" (SKELTON, 2013, p.470). URRY (2002) was conclusive when stating that issues of social exclusion could not be examined without identifying the complex, overlapping, and contradictory mobilities. Representatives of this paradigm were influenced by aspects present in the work of sociologists such as LEFEBVRE or SIMMEL. However, they also integrated discussions from science and technology studies and the ontological turn scholars, which allowed for the consideration of the agency of non-human actants (LATOUR, 2005) in the production of mobility flows, among their varied contributions. [8]

Various authors have explored different forms which human mobility can take: "Corporeal," "imaginative," and "virtual" (URRY, 2002, p.256); "biological," "mechanical," and "electronic" (BERICAT, 2005, p.15), alongside a range of legal, social, and temporal conditions that could enable or constrain them (SÁNCHEZ-BLANCO, 2013; URRY, 2002). Regarding the configuration of inequalities, URRY (2002) suggested that physical co-presence was necessary for the density of social capital. However, he also predicted that new forms of virtual mobility were creating a "strange and uncanny life on the screen" (p.258), which could change the understanding of co-presence. This idea progressively gained popularity, leading to the imagining of virtual, digital, or hybrid mobilities (SHELLER & URRY, 2016). [9]

In recent years, especially in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic, there has been an increased interest in digital or hybrid spaces and the production of subjectivities. SHELLER and URRY challenged diagnosis concerning the decline in sociability and a reduction of social capital due to the progressive fragmentation and growing loneliness brought about by the digitalization of everyday life. On the contrary, they stated that, in complex and multiple ways, people were appropriating technologies in everyday practices that enable connectivity and a sense of being together. [10]

Regarding youth and returning to the relationship between (im)mobilities and inequalities, ethnographers in Latin America and Sub-Saharan Africa stated that young people from lower-income backgrounds often faced obstacles exercising the right to the city due to processes of segregation and "territorial embeddedness" (BAYÓN & SARAVÍ, 2022, p.60, see also ARAMAYONA & NOFRE, 2021; GOUGH, 2008; SEGURA, 2017; VAN-BLERK, 2013). These processes result in many young people from low-income neighborhoods spending most of their time at home and engaging in solitary activities. However, as SAVEGNAGO (2020) aptly pointed out in her research about young people in Rio de Janeiro, after the massification of the accessibility to the Internet and the possibility of connecting with others through digital devices, youngsters have created a spectrum of practices occurring in "virtual mobility" environments. Thus, we might be witnessing a profound transformation in forms of youth sociability, leading to redefining their mobility and spatiality (FATTORE, FEGTER & HUNNER-KREISEL, 2021; GWAKA, 2018). [11]

At the present time, how have these ideas impacted socio-educational studies? Fifteen years ago, there was a noted lack of empirical research connecting mobility with educational experience (LEANDER et al., 2010; LINDGREN & LUNDAHL, 2010). Thereafter, this relationship has been primarily addressed with attention to migration processes and forced displacements (GAVAZZO, BEHERAN & NOVARO, 2014; MAGGI & HENDEL, 2022; YEPES-CARDONA & GIRALDO-GIL, 2023; ZENKLUZEN, 2020), but infrequently about everyday mobilities within the same city (GARCÍA-BASTÁN, 2023; TAPIA, 2023). The role of schools in producing mobility has not been thoughtfully explored (LINDGREN & LUNDAHL, 2010). This is paradoxical as, although in most of the literature researchers do not adopt an analytical perspective of mobilities, they report (directly or indirectly) a significant relationship between spatial mobility processes and inequalities in educational access (TAPIA, 2023). [12]

Moreover, there has recently been particular concern about the harmful effects of information and communication technology (ICT) (especially mobile phones) in the school environment (UNESCO, 2023). It seems reasonable to assert that the simultaneous use of smartphones and other technological devices in the classroom could lead students to become engaged in activities unrelated to schoolwork (KATES, WU & CORYN, 2018). As DI NAPOLI and IGLESIAS (2021) pointed out, mobile phones in schools constitute "a communicative link between virtual and face-to-face interactions" (p.16). Far from being mere tools, they are environments of socialization in their own right (FATTORE et al., 2021; FAY, 2007; GORDO-LÓPEZ, GARCÍA-ARNAU, DE-RIVERA & DÍAZ-CATALÁN, 2019). However, once this possibility is acknowledged, we note that what young people do in the digital world—along with the "territories" they choose to inhabit—often became of interest to researchers in cultural studies who detached this issue from the school context, concentrating on youth practices and consumption on digital platforms and apps. [13]

As we stated previously, our aim was to explore intertwined mobilities in the sub-worlds of youth socialization in relation to their school experience. This knowledge goal meant to us a methodological exploration that will be addressed after revising existing approaches to the study of youth mobilities. [14]

2.2 Methodological approaches to youth mobilities

Less than two decades ago, the relationship between youth and mobilities was not widely researched (BARKER, KRAFTL, HORTON & TUCKER, 2009). Since then, a substantial and growing body of empirical studies has been produced.3) English-speaking countries, especially the United Kingdom, is where mobility studies developed the most. Within Latin American countries, Argentina and Brazil have a more extensive body of work. There are also many studies conducted in Africa and Asia. Researchers who leaned on the mobilities paradigm and worked with youth populations have used a variety of methodological approaches. [15]

A small subset of the literature was produced applying quantitative methods, including the development of original surveys (BĄK & BORKOWSKI, 2019; COLLIN-LANGE, 2014; GROTH, HUNECKE & WITTOWSKY, 2021; MONACO, 2018; RYE, 2011) and the use of existing public datasets (PELIKH & KULU, 2018). These researchers examined the relationships between structural conditions and patterns of youth mobility among specific generational cohorts. Quantitative approaches are useful for structuring comparisons and identifying transnational differences in forms of mobility. However, as noted by MAXWELL (2012), such approaches limit researchers' capacity to trace the processes and local causal mechanisms underlying those differences. [16]

Qualitative research makes the most of the literature reviewed. Biographical studies or those based on in-depth interviews predominate (GARCÍA-BASTÁN & PAULÍN, 2016; GHISIGLIERI & CARDOZO, 2022; HUILIÑIR-CURÍO, 2018; MAGGI & HENDEL, 2022; RIQUELME-BREVIS, SARAVIA-CORTÉS & AZÓCAR-WEISSER, 2024; SIERRA & SOLANO, 2021; TAPIA, 2018). Here, mobility—especially involving migratory displacements—was reconstructed from narrations about the life experiences of a group of youngsters, allowing a diachronic and relational research perspective (KIESLINGER, KORDEL & WEIDINGER, 2020). These approaches were grounded in the narrativization of past experiences, which proves particularly fruitful to study mobilities spontaneously associated with certain significant events or biographical milestones (LECLERC-OLIVE, 2009). However, as we observed in earlier biographical research (GARCÍA-BASTÁN & PAULÍN, 2016; PAULÍN, GARCÍA-BASTÁN, D'ALOISIO & CARRERAS, 2018), they tended to be less productive when focusing on present-day quotidian mobilities. We often required specific prompts that changed the life-based focus of the interview, landing as artificially introduced issues, unrelated to the topics chosen by the young people to structure their own life story (LAINÉ, 1998). [17]

Ethnographic or observational research also constitutes a consolidated tradition in Europe, Africa, Latin America, and even Asia. In these approaches researchers primarily focused on topics such as migration (FLORISTÁN-MILLÁN & MARMIÉ, 2023; GERBAUDO-SUÁREZ, 2018; MAGGI & HENDEL, 2022; VAN-GEEL & MAZZUCATO, 2018; ZENKLUZEN, 2022), international student mobility (ALLAN & CHARLES, 2015; BERG, 2015; SANDER, 2016), and youth mobilities in rural contexts (AHARON-GUTMAN & COHEN, 2019; BARÉS, 2021; HENDEL, 2021; MARIONI & SCHMUCK, 2019; MARTÍNEZ, 2023). To a lesser extent, the daily experience of urban mobility was addressed (McAULIFFE, 2013; SÁNCHEZ-GARCÍA, OLIVER, MANSILLA, HANSEN & FEIXA, 2020; VAN-BLERK, 2013). We also found here experiences involving techniques such as "guided walks" (ROSS, RENOLD, HOLLAND & HILLMAN, 2009, p.605) or "walk-along interviews" (HEIN, EVANS & JONES, 2008, p.1276), where researchers moved along with their young informants, providing rich narratives about daily youth mobilities. Here, the limitations are linked to the scope of the observations, which were typically confined to specific, situated activity contexts—such as streets, neighborhoods, school facilities, or recreational settings like parks, playgrounds, sports clubs, and skateparks—and were often shaped by fragmented research questions. As previously noted, this focus may fail to capture the multiple and intersecting constraints which influence youth socialization (LAHIRE, 2006). Additionally, adopting these research approaches requires funding for time-consuming field trips (KIESLINGER et al., 2020). [18]

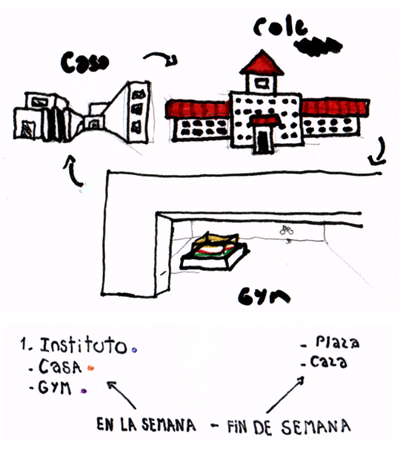

We also found varied experiences of participatory cartographic production, a knowledge co-construction strategy based on horizontal participation, dialogue, and interdisciplinarity (DEN BESTEN, 2010; RAMOS, MOVILLA, ROZO & RODRÍGUEZ, 2022). In general, these scholars emphasized the potentiality of participatory techniques for empowering populations about their local territories (ESPINEL-RUBIO & FEO-ARDILA, 2022; GARCÍA-BASTÁN, 2023; LEY & SOLORIO, 2024; MARQUES & SOUZA, 2019). The working sessions often aimed to produce sketches or territorial maps that objectify meanings related to the lived space (LEFEBVRE, 1991 [1974]). Maps provided by the research team were also frequently drawn over to locate areas of conflict or threats, as well as resources or infrastructure concerning specific issues. In some approaches, researchers incorporated digital diaries, geo-referencing technologies, photovoice or "podwalking" techniques (HAMMOND & COOPER, 2016; LEYSHON, DiGIOVANNA & HOLCOMB, 2013; SALVIDGE, 2022; SILVA, SANTOS & COLTRI, 2024; VOLPE, 2019), which in some opportunities have raised ethical debates related to participants' consent to be monitored and located or to the control over the digital information collected (HEIN et al., 2008). This last set of research is the most significant to understanding the impact of digital mobilities on youth experience. [19]

We identified interesting experiences in which researchers made adjustments to cartographic techniques for specific research goals. This is the case of HENDEL (2020) in Argentina, who introduced the tool of "danger cartographies" (p.190): Visual productions that include "illustrations, photographs, and intervened maps" (ibid.). Through this work, she explored how youth mobilities occurred in a neighborhood in the Province of Buenos Aires where their school was located, along with the limits and boundaries that signal recent transformations in practices and security policies. [20]

In Rio de Janeiro, SAVEGNAGO (2020) also designed a series of workshops to map youth urban routes from home to school and vice versa, as well as other places far from home. In these workshops, youth created designs, and stories that became inputs for subsequent focus groups. This allowed for the reconstruction of affections evoked by home (the imaginary of "protection" and "shelter") and the street ("danger" and "adventure"). As a common feature in both initiatives, we want to highlight how they linked mobility with emotionality. [21]

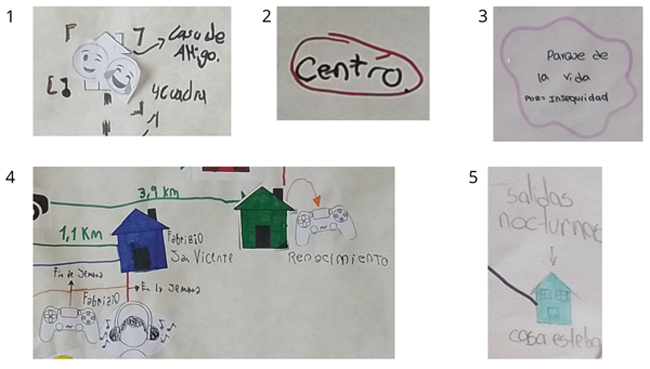

Overall, researchers applying cartographic techniques have proved their value for producing visual data that can give account for youngsters' mobility experiences. The use of these tools implies a form of expression more familiar to youth, helping to bridge linguistic gaps that can arise in intergenerational dialogue. Nevertheless, producing cartographies typically requires complementary conversational methods to avoid over-reliance on researchers' interpretations and to ensure that the meanings attributed to the visual data are grounded in participants' own perspectives (DEN BESTEN, 2010). [22]

Both the production of cartographies and the implementation of conversational approaches contributed to inform the design of our own methodological tool. However, we also recognized that the adoption of these methods—given the theoretical objectives for which they were originally developed—often fell short in integrating the multiple levels of youth mobilities that correspond to diverse and overlapping contexts of socialization. As noted in the introduction, there is limited production in which authors analyzed the urban educational or school experience from the perspective of mobilities (GARCÍA-BASTÁN, 2023; LINDGREN & LUNDAHL, 2010; TAPIA, 2023, 2025). Generally, the intersection between schooling and mobility occurred when characterizing the experiences of migrant students or those from rural areas (HENDEL & MAGGI, 2021; LIND & AGERGAARD, 2010; MARTÍNEZ, 2023; SCHMUCK, 2021; SEVERINSSON, NORD & REIMERS, 2015). GRANDA (2024) recently pointed out that qualitative studies are powerful for simultaneously understanding school, extracurricular, and community experiences. However, as intended to show in this section, we did not find specific tools for studying this relationship, and even less so to move towards an integrated approach of overlapping mobilities which can account for the diversity of youth experiences. Based on these considerations, we set out to generate a tool capable of capturing intra- and extra-school mobilities, along with those occurring in digital environments. [23]

3. A Tool to Capture Youth Mobilities

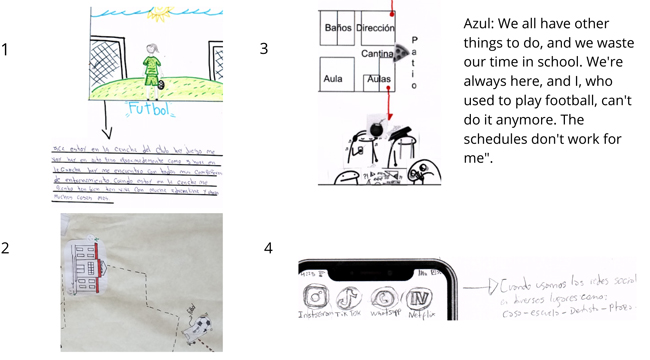

After reviewing the methodological literature on youth mobilities and outlining the main issues and limitations described in the previous section, our research team—which comprised fifteen members, including five senior researchers and ten university students—held a series of meetings to design a tool tailored to our research purposes. In earlier work involving cartographic techniques (GARCÍA-BASTÁN, 2023), we observed that exploring youth mobilities often required more than a single working session. This was partly because participants did not always engage readily with the tasks, but also because, by the end of the session—and particularly after viewing their peers' contributions—many realized how much more they could have expressed, drawn, or added to their own personal cartographies. [24]

Another key consideration in promoting diversity was the need to include a session dedicated to solitary work, allowing participants to explore their individual mobility patterns before transitioning to collective work. While group settings have strong potential to stimulate imagination and facilitate the flow of ideas through peer exchanges (BAEZA-CORREA, 2002), we also aimed to avoid limiting all participants' opportunity to reflect on their unique experiences. This approach helps mitigate what is often referred to as exclusion filters (CANALES & PEINADO, 1995)— the dynamics of power that can skew participation within group settings. [25]

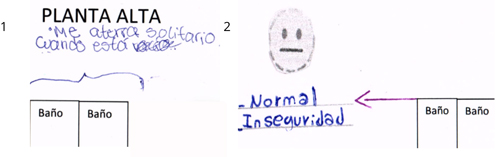

While the groups were working on their maps, the coordination team would circulate engaging in conversation and setting the pace of the task, as some groups took excessive time on details deemed irrelevant to our research questions (for instance, checking that their maps were to scale or fully coloring or decorating each of the buildings drawn). In this sense, although our time frame to work in each session was limited, we were conscious there was a risk of the tasks becoming too "school-related." Thus, we tried not to put pressure on students, even when it would lead to groups not fully completing the assignment. [26]

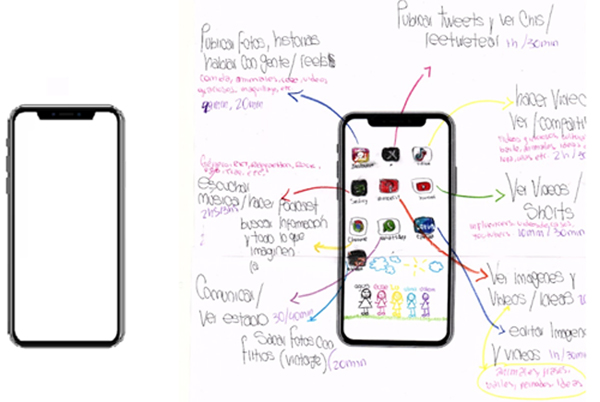

At the suggestion of the younger members of our team—university students who were closer generationally to the participants' cultural interests—the second and third sessions incorporated emojis and memes alongside the cartographies to represent students' feelings and emotions associated with their mobilities. This approach was immediately embraced by students, who demonstrated a sophisticated use of these expressive forms, many of which they were already familiar with. By the end of the session, many students asked if they could keep the unused paper emojis. Surprisingly, these resources deeply engaged the students and prompted us to reflect on the importance of considering youth aesthetics when designing methodological tools for them. [27]

As stated before, because of our theoretical assumptions, a series of mobilities needed to be explored in order to gain a deeper understanding of youngsters' experiences: Territories, school environment and digital scenarios. To this aim, we designed four different working sessions, each one adding to the table a specific "mobile layer" (see Table 1). As we said before, the first session had a propaedeutic function: It served as an introduction to the series and as a first attempt for students reflecting on their personal mobilities. Individually, students had to work on their own representation of everyday activities, identifying places in which each took place. The following three stages involved working in groups to produce a cartographic representation of, respectively, their quotidian urban mobilities, activities and movements within school facilities and, finally, digital mobilities. In this way, each of these three remaining sessions were designed considering the operationalization of: 1. "Urban (im)mobilities" (SKELTON, 2013, p.468) (displacements in a continuum between territorial embeddedness and "profuse mobility"); 2. "Mobilities of learning" and school space-related emotions (LEANDER, et al., 2010, p.346); and 3. "digital mobilities" (SHELLER & URRY, 2016, p.17) through "digital socialization environments" (GORDO-LÓPEZ et al., 2019, p.144). [28]

In designing this set of workshops, we were guided by the metaphor of a palimpsest: A surface overwritten multiple times, yet still bearing the traces of earlier inscriptions. The goal of having each group of students participate in the full sequence of workshops was to generate materials that would allow us to trace and interconnect different dimensions of mobility, ultimately reconstructing a more nuanced and layered image of school-age youth mobility experiences. This stands in contrast to the fragmented views critiqued in the previous section. To facilitate this, all cartographies were scanned and digitized, then organized into Google Drive folders categorized by school and workshop session. Each file was labeled with participants' names, which significantly simplified tracking and cross-referencing during the analysis phase.

|

Workshop session |

Aim |

Instructions/Prompts |

Materials |

|

1. Mapping Daily Life Activities |

To reconstruct a typical day distinguishing between times of the day and activities that occur in school and out-of-school time. |

Identify places visited daily, means of transportation, daily activities performed, and social interactions experienced. |

Sheets of paper and colored pencils or markers. |

|

2. Urban Mobilities |

To identify urban routes to and from school, recognizing significant spaces for youth participation. |

Create a map that includes: Places where educational, religious, sports, and leisure activities occur. Non-transited urban spaces. Routes, distances, and means of transportation. |

An A0-sized sheet of paper, colored pencils or markers, printed emojis, glue. |

|

3. Practices and Emotions in the School Territory |

To graphically represent how school spaces are used, what activities occur in each, and the emotions associated with them. |

Register on a school map: Feelings related to each space, social interactions, daily problems. |

An A3-sized school map, colored pencils or markers, emojis, glue. |

|

4. Digital Mobilities |

To map daily practices in digital environments: Activities, games, interactions, leisure activities, risks, and precautions taken. |

Intervene the image of a mobile phone indicating: Daily virtual environments (apps), practices, uses, social interactions. |

An A3-sized sheet with a printed blank mobile phone, colored pencils or markers. |

Table 1: Description of the workshop sequence carried out with each of the four groups of students [29]

During our fieldwork, considering segregation processes for low-income urban youngsters, we selected three schools from the urban periphery of Córdoba, Argentina, using a theoretical sampling criterion (SCHREIER, 2018). This was based on the fact that these types of institutions are predominantly attended by young people from peripheral neighborhoods who face greater mobility obstacles. Two of the schools were state-managed while the third was privately run.4) We worked with four groups of students aged between 16 and 17, corresponding to the 5th year of Argentine secondary school. Each group was composed of 20 to 25 people. [30]

Before initiating our intervention we conducted a brief survey with the young participants, which revealed some differences, particularly in the case of the private school compared to public (state-managed) ones. While the youth population of all three schools could generally be classified as belonging to the working class based on their neighborhoods, there were educational disparities. In the public schools, the majority of families had parents whose maximum level of schooling was secondary education (completed or not), whereas the private school reported a more balanced distribution, with an equal proportion of parents holding secondary and tertiary/university degrees. [31]

Another key difference emerged in the perception of state-provided assistance or benefits. In the public schools, half of the students reported receiving meals through a state social program available only to households with very low incomes. This program was not offered in the private school, suggesting that these students' families likely covered food expenses themselves. Similarly, there was a noticeable gap in perceptions of educational scholarships granted by the national government: Around 10% of students in the private school reported receiving this benefit while half of the students in the public schools did. [32]

These economic differences were reflected in the mobility patterns observed throughout the study, especially during the neighborhood mapping workshops (Session 2). Students from the private school reported more frequent movements related to participation in artistic, sports, recreational, and extracurricular educational activities; topics that were either mentioned less frequently or not at all by students from the public schools. [33]

During September, October, and November of 2023, we conducted the four workshop sessions with each student group (resulting in a total of sixteen sessions), which we describe below. These sessions were held no more than fifteen days apart. We requested informed consent from each participant. Additionally, the instruments, procedures, and informed consent models used received a favorable assessment from the Ethics Committee of our institute.5) [34]

A group of five research team members coordinated each workshop. The sessions began with a work prompt in separated small groups (of five or six young people), which involved the production of a map using materials provided by the research team (see Table 1). Before the end of each session, the coordination team visited the groups, conducting brief interviews about their thoughts on the work produced. These conversations, which we informally called "micro interviews" because of their relatively short duration, resembled the journalistic coverage of an event, where we briefly conversed with the youngsters about the work previously done. They were recorded and transcribed as a verbal backup for the visual data, in order not to rely exclusively on our own interpretations (DEN BESTEN, 2010). [35]

3.2 Description of each session

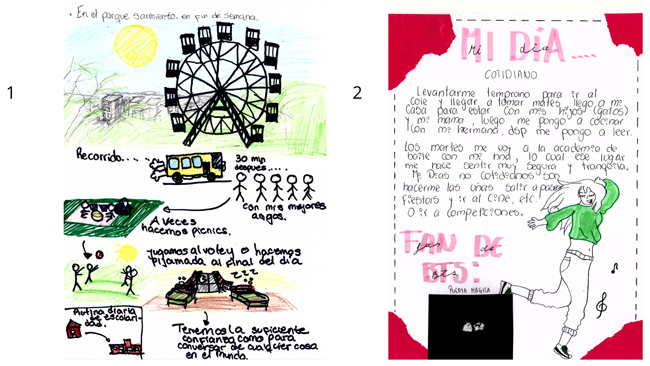

In the first workshop of the sequence, we invited young people to represent a typical day in their lives. The individual prompt asked students to identify places they visited regularly, including means of transportation, daily activities, and social interactions. Although materials (such as sheets of paper and colored markers) were provided, the prompt did not specify how the task should be approached. This open-ended instruction led to a range of creative responses, from comic-style drawings to collages. Some students even opted to provide written descriptions of their daily routines (see the Appendix). This initial task facilitated the differentiation of activities on weekdays versus weekends, as well as the mobilities associated with each one.

Figure 1: Fragment of a production from Workshop 1. Weekly activities (being at school, at home, and at the gym) and those

specific to the weekend (spending time at home or at the neighborhood playground)

Figure 2: Fragment of a production from Workshop 1. Daily transits between school, the neighborhood playground, and home.

The text reads: "I come and go between school, my house, and the playground most of the time." [36]

Although the task itself was relatively simple, as analysts, we could detect significant differences in the responses. For example, gender differences emerged: Young women tended to include more domestic responsibilities or caregiving activities, which resulted in them spending more time at home during out-of-school hours. They also frequently expressed feelings of insecurity, some noticed that they only felt safe walking home from school when being accompanied by male classmates. [37]

The outputs from this first workshop provided a broad view of daily mobility experiences, revealing interesting contrasts. For example, we observed a clear distinction between those students whose mobilities were limited to "going to school and back home" and those who engaged in a wider range of activities such as artistic, cultural, sports, or religious pursuits. This exercise also highlighted the agency of different actants shaping these experiences: From public transportation buses to the social aspects of neighborhood interactions:

"Camila: I have to take the bus everywhere.

Ignacio: For example, Guadalupe, our friend, takes the bus to the city center; she goes quite far. Me, on the other hand ... my main group of friends is from the neighborhood" (Fragment of a micro interview). [38]

In the second workshop, we focused on creating a collective map of mobility to and from school. We asked students to place their school at the center of a large sheet of paper and map out each of their daily routes, including approximate distances and means of transportation. Each group was provided with an A0 sheet of paper, printed icons (featuring various drawings such as cars, buses, traffic signals, sports symbols, emojis, and memes), as well as markers and glue. [39]

As groups of young people spontaneously formed, these cartographies allowed us to reconstruct how the activities identified in the previous workshop integrated into a more complex and dynamic map, reflecting existing social relationships. With regard to data, this activity vividly illustrated the mobility patterns of youth: By examining the distances between places, we were able to confirm processes of territorial embeddedness for some groups, while also observing a rich variety of mobilities in other cases. For example, for the first group, leisure activities were predominantly confined to the immediate territory—the neighborhood and its surroundings— likely due to factors such as "feelings of insecurity" (Figure 3, fragment 3). Additionally, homes were frequently marked as the sole locations for nighttime recreation. In contrast, other youth demonstrated a broader range of mobilities, engaging in sports, cultural, consumption, and religious activities that involved long-distance travel.

Figure 3: Fragments of maps from Workshop 2. References: 1. Listening to music at a friend's house that is four blocks away

from me; 2. The city center is crossed out because it is not considered a well-frequented place; 3. The neighborhood park

is avoided due to its insecurity; 4. Playing video games at home on weekends; 4. Esteban's house is a space for nighttime

outings [40]

In addition, integrating schools into the urban mobility framework allowed us to capture some limitations to mobility imposed by the school itself. For many young people who spend at least eight hours at school, being there was not only perceived as boring but as a clear obstacle to engaging in other activities, especially since many participants had formal or informal jobs during their out-of-school time:

"Pilar: I wake up at 5 a.m. to work at McDonald's. I'm scared even at the bus stop! After that, I go home, make lunch, then go to school, and then back home to cook for my siblings, who are many! The next day, at 5 a.m., I do it all over again.

Juliana: We waste the whole day here" (Fragment of a micro interview). [41]

During the third workshop, using iconographies, emojis, and a map of the school facilities, youngsters had to represent their activities and emotions in various spaces, providing a graphic representation of their emotional registers in each place. For our research, it was crucial to understand how students felt in different school spaces, particularly since previous studies have shown that schools are often perceived as boring and monotonous (GARCÍA-BASTÁN, 2023). Within the mobilities framework, these emotional responses can be framed as part of a broader map of mobilities, highlighting the relationship between the school and other spaces. As shown in Figure 4, the "heaviness" of spending an entire day at school was frequently linked to more appealing activities that were often restricted by the extended school day. Additionally, this feeling was connected to other forms of digital mobility within the school, such as listening to music, watching videos or spending time on social media during class. The latter could be tracked in the productions of different sessions (Figure 4), further reinforcing the complex interplay of school, leisure activities, and digital spaces.

Figure 4: 1. Fragment of a school map from Workshop 1 made by Bianca. The caption reads: "Here I am at the club's field. There

I play [football]. I go by bus and spend approximately three hours. I meet all my mates there. When I am at the field I feel

so good, so alive, with much adrenaline and many other things." 2. The map from the second session shows the distance between

the school and the football field. 3. Extract from a micro interview with Bianca's classmate, during the third workshop. She

explains to the interviewer why they chose those emojis for the classroom (aula, in Spanish). 4. Fragment of a digital map showing entertainment apps. The caption reads: "We use Social Media in diverse

places: Home-school-dentist-playground."

Figure 5: School map from Workshop 3. Emojis indicate emotions in each school space. The entrance gate, guarded by a police

officer, prevents the entry of a thief who resides in the "red zone" (dangerous zone), outside the school. [42]

Maps of their schools contained references to a diversity of experiences, feelings, and emotions: Youths' assessments of comfort of learning spaces; identification of environments where trust-based and affective-pedagogical relationships with teachers were established or spaces where they felt judged by these same adults; differentiations between leisure and sports locations, places for political participation, collective organization, areas of allowed and forbidden consumption, and even some areas with erotic and affective connotations (e.g., places where couples would go to kiss). [43]

When compared to earlier maps of the "outside world," school cartographies provide an insight into how young people perceive the school environment, often as a safer or more regulated place. This is illustrated in Figure 5, where a group depicted a thief lurking near the school grounds, implicitly framing the school as a place of relative safety. Other emotions expressed in the maps were directly linked to the organization and regulation of the school's physical space. For instance, some groups mentioned that the school bathrooms "scared them" when no adults were present (Figure 6). These cartographies are a valuable source of information about the range of emotions experienced by youngsters but, especially, how they can shift from their school mobilities to their out-of-school mobilities.

Figure 6: Fragments from school maps from Workshop 3. Inscriptions related to the school bathrooms read: 1. "I'm terrified

when it's empty;" 2. "Insecurity" [44]

In the fourth and final workshop, we explored mobility within digital environments. Each small group was provided with an image of a blank mobile phone (Figure 7) and asked to fill it in with the apps they used, the usage period of each one, and their practices of virtual sociability. This strategy emerged from extensive discussions within our team about which apps to include in the activity. Ultimately, using a blank phone template allowed us to avoid predefining the digital environment, giving participants the freedom to construct their own repertoires. As a result, we discovered a much broader array of apps and digital practices than we could have anticipated.

Figure 7: Image of the mobile phone, before and after being drawn. The group of students listed the apps used, their purpose,

and usage period. [45]

By looking at these "digital maps," we could note a constant flow of young people in digital environments. We documented a diverse set of practices, including the consumption and production of digital content, a thriving online sociability with sophisticated personal presentation strategies, and a variety of school-related uses. The latter included everything from searching for information to organizing study meetings with schoolmates outside of the "official" school time, using video-conferencing apps. [46]

This session enabled detailed descriptions of how young people use multiple apps and digital platforms, as well as the amount of time typically spent on each. When contrasted with the previous cartographies, the digital maps made it easy to visualize how urban mobilities are often layered with a strong presence in digital environments. School was no exception: In their digital maps, students revealed a complete coexistence between school-related activities and virtual mobilities. Most importantly, this final activity helped us identify youth practices that actively produce school spaces beyond the physical school grounds. A notable example was the use of videoconferencing apps for group homework, an insight we have analyzed further in relation to how digital tools facilitate and shape school-related tasks (GARCÍA-BASTÁN, D'ALOISIO, ARCE-CASTELLO, BONANSEA & SEGOVIA, 2025). These practices are often missed when researchers use methodologies focused solely on in-school contexts, which tend to highlight how digital media disrupt schoolwork (UNESCO, 2023), rather than how they enable it. Additionally, researchers relying on such traditional approaches struggle to capture practices that occur without adult supervision, an increasingly common dynamic due to the autonomy that digital platforms afford young people (LINNE, 2018):

Darío: “I'm busy with activities all day, so to meet in person to do homework, I need my parents to give me a ride. So, I prefer to meet virtually because I'm at home, I have my computer, I'm comfortable, and if I need to do something, I can do it. I don't disrupt my routine too much, especially in terms of transportation. For example, if we need to make a school presentation, we use Canva, we share access to different documents, gather on Meet [Hangouts] where we can see each other. We even have a WhatsApp group where we share information, keep each other updated, and that's it" (Fragment of a micro interview). [47]

Lastly, although our team did not initially anticipate this form of agency, several students mentioned using music apps—such as Spotify, Lark Player, and YouTube—as tools to create "the right environment to study" (Fragment of a micro interview) In this context, certain digital platforms appear to generate an "ephemeral sound space" (LASÉN-DÍAZ, 2018, p.107) that makes the immobility of daily school life more bearable. This highlights how digital cartographies can help uncover an additional analytical layer: The soundscape as a meaningful actant in youth mobilities, shaping not only physical and digital movement but also affective and sensory experiences within educational spaces. [48]

In this article, we shared a methodological tool to explore youth mobilities related to the school experience. Researchers focusing on the intersection of youth and mobility have primarily relied on ethnographic and biographical approaches to reconstruct migratory itineraries, urban mobilities, and participation in digital spaces. To a lesser extent, mobility experiences have been reconstructed from quantitative surveys. On the other hand, researchers on youth school experience have given less consideration to mobility, except for studies focused on migrant populations. [49]

Our intended purpose was to integrate various dimensions of youth mobility (urban, school-related, digital) to understand the schooling process. In this sense, unlike quantitative approaches, our tool can give account for the local causality (MAXWELL, 2012) involved in youth mobilities: Even when the purpose of this article was not to display results, the material shared shows multiple factors involved in youths’ (im)mobilities. As for qualitative techniques, we recovered the strengths of both cartographic and conversational tools in a way that can integrate visual data about different realms of youth socialization simultaneously, keeping the richness of conversational data as well. On the one hand, the sessions were explicitly designed to address mobility practices. Therefore, some of the limitations of biographical research—such as the often forced introduction of the topic into the storytelling process—were overcome. On the other hand, thanks to the palimpsest-like strategy, different levels and concepts related to mobilities could be operationalized within a more integrative approach. The organization of digital data by workshop session and participant facilitates the construction of a more complex and nuanced landscape of youth mobilities. [50]

In summary, the cartographic work we shared can be useful for researchers who aim to build their objects and research questions with a mobile perspective, avoiding the fragmentation of experiences (LAHIRE, 2007). The proposed tool was productive for exploring emerging aspects in well-established substantive fields. In this sense, we believe that even research not directly related to educational processes could benefit from incorporating the documentation of school mobilities. [51]

From a technical point of view, in comparison to strategies requiring the availability of mobile phones or Internet connection, the proposed set of tools is very cost-effective and avoids ethical dilemmas related to consent for monitoring subjects via digital apps, which could potentially provide sensitive information to corporations producing these interfaces (HEIN et al., 2008). [52]

Regarding the limitations of the tool, compared to the prolonged presence in the studied contexts ensured by ethnographic strategies or walking interviews, our approach was rather episodic or "photographic." Even though we took precautions by accessing the studied cases through trusted school agents, certain aspects of mobility remained beyond our reach, likely due to a social desirability bias, a common concern in survey-based research (KRUMPAL, 2013). While in our approach we did not seek a positivist objective truth, nor did we assume that participants were intentionally untruthful, we now acknowledge that they may have chosen to emphasize topics they believed would be less subject to adult judgment. A clear example of this was the issue of money betting in virtual casinos during school time (an activity that involves human digital and financial mobilities). Although this was a frequent concern expressed by the teaching staff of the participating schools, it did not come out as a topic during the workshops on digital mobilities. Something similar occurred with dating apps. In both cases, these kinds of environments are designed for adults. The presence of underage individuals is illegal, which might have motivated students to avoid their mention. [53]

We do not consider this a limitation of the tool itself, but rather a result of the way our work scheme was framed. The procedures created and shared in this paper are perfectly compatible with ethnographic approaches. In doing so, researchers could complement the production of graphic and conversational data with a deeper and more diachronic reconstruction of youth social experiences in context. Furthermore, producing digital maps helped us recognize the importance of considering the production of portable sonic environments (LASÉN-DÍAZ, 2018) as a factor that can shape (im)mobility experiences, e.g., reducing the "heaviness" of the immobility inherent to school settings. In this regard, the proposed tool could be expanded to include the recording of soundscapes in the maps, understanding this as another element (another actant) of many mobility practices. [54]

As stated from the beginning, we consider methodological reconstruction a key to approach new phenomena (DENZIN, 1994; VASILACHIS, 2009). In our case, it also complements the intention to include youth participation in their broader school and social experience. The development of these mobility maps, combining workshop methodology, micro interviews, and graphic production, is part of a theoretical-methodological recreation line developed by our research team, which seeks the collective construction of data with participants (PAULÍN et al., 2011). In this sense, participatory processes were developed in a framework of trust and openness that allowed the generation of graphic, visual, and conversational productions with young students, thereby producing narrative visual data that provide access to social knowledge and practices to show their perspectives in a collective production context. [55]

There are still unanswered questions with regards to the practical purposes of all participant observation in social research (MAXWELL, 2012 [1996]): How can these productions be shared within the framework of a collaborative research approach with educational communities? What other types of narrative-visual analysis could be done with this rich and multifaceted material? How could we move towards a co-analysis model that involves young people in a more active way? These are challenging aspects of social research, irreducible to technical or purely methodological discussions. Theoretically, we believe that the possibilities for transferability should be something researchers focus on, leading us to a broader scientific engagement. Overall, we consider that the type of cartographic work undertaken here has enabled the construction of shared narratives and the objectification of mobile frameworks that could offer tools for enriching both youngsters' school and civic lives. [56]

We are grateful to the anonymous reviewers for their insightful feedback which helped to improve this paper. We would also like to thank the authorities of the participating schools for granting permission to conduct our fieldwork, as well as the young participants for their engagement and willingness to take part in the proposed activities. Our gratitude also extends to the members of our research team: Florencia D'ALOISIO, María Florencia CAPARELLI, Valentina ARCE-CASTELLO, María Eugenia PINTO, María Fernanda MACHUCA, Adriana CEJAS, Natalia BONANSEA, Natasha SEGOVIA, Franco RUDA, Valentina ABASOLO, Luz DÍAZ, Julieta DELVITTO, Dalma CRUZ and Clara CAMPOS-URÁN. Finally, we would like to express our special thanks to Dr. Jessica HAZELTON, Nahiara PALACIOS, and Consuelo ANDINO for their assistance with the English revision of this article.

Appendix: Diversity of Students' Tackling Strategies During Workshop 1

Figure 8: 1. Comic-style representation of the activities during weekends; 2. Collage and narrative description of a daily routine

1) Project: "Trayectorias escolares y experiencias juveniles en la escuela (post)pandémica. Un análisis desde marcadores de generación, clase, género, y territorio" [School trajectories and youth experience in post-pandemic school. An analysis through the lens of generation, class, gender and territory]. Co-funded by Mincyt-Córdoba y SECyT-UNC. <back>

2) All translations from non-English texts are ours. <back>

3) We carried out searches in the open-access databases Scielo, Redalyc, and OpenAIex with the following tags: "mobilities AND young people,""mobilities AND youth,""mobilities paradigm AND young people," and "cartographies AND young people." In this way, nearly 1,000 results were obtained. We also searched for these tags in FQS. After removing duplicate or irrelevant results, we kept and reviewed a set of 75 articles, most of them are cited throughout this paper. <back>

4) Argentina is known for its fragmented educational system (TIRAMONTI, 2004). Although high income families often choose private education, many private schools are State-subsidized and charge very low or no tuition fees. As a result, the labels "private" and "public" do not always correspond to distinct income sectors within schools. <back>

5) Throughout this paper, participants' names have been changed to provide anonymity. <back>

Aharon-Gutman, Meirav & Cohen, Nir (2019). Refusal, circulation, refuge: Young (im) mobilities in rural Israel. Social & Cultural Geography, 20(6), 849-870.

Allan, Alexandra & Charles, Claire (2015). Preparing for life in the global village: Producing global citizen subjects in UK schools. Research Papers in Education, 30(1), 25-43.

Aramayona, Begoña & Nofre, Jordi (2021). Bandas de Barrio (neighbourhood gangs) and gentrification: Racialised youth as an urban frontier against the elitisation of suburban working-class neighbourhoods in twenty-first-century Madrid. In Ricardo Campos & Jordi Nofre (Eds.), Exploring Ibero-American youth cultures in the 21st century (pp.49-73). Cham: Palgrave McMillan.

Baeza-Correa, Jorge (2002). Leer desde los alumnos(as), condición necesaria para una convivencia escolar democrática [Reading from students, necessary condition for democratic school coexistence]. In UNESCO (Ed.), Educación secundaria. Un camino para el desarrollo humano [Secondary education. A path to human development] (pp.163-184). Santiago de Chile: UNESCO, https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000137366_spa.locale=es [Date of access: June 25, 2025]

Bąk, Monika & Borkowski, Przemyslaw (2019). Young transport users' perception of ICT solutions change. Social Sciences, 8(8), 1-17, https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci8080222 [Date of access: December 10, 2024].

Barés, Aymará (2021). Construcciones de sentido sobre el campo: Jóvenes y territorio en norpatagonia [Meanings of the countryside: Youth and territory in northern Patagonia]. Estudios Rurales, 11(24), 1-17, https://doi.org/10.48160/22504001er24.156 [Date of access: December 10, 2024].

Barker, John; Kraftl, Peter; Horton; John & Tucker, Faith (2009). The road less travelled. New directions in children's and young people's mobility. Mobilities, 4(1), 1-10, https://doi.org/10.1080/17450100802657939 [Date of access: December 10, 2024].

Bayón, María Cristina & Saraví, Gonzalo (2022). Espacios de pertenencia juvenil en contextos de desventaja: Tensiones y disputas [Spaces of belonging for youth in disadvantage contexts: Tensions and disputes]. Última Década, 30(59), 43-74, http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0718-22362022000200043 [Date of access: December 10, 2024].

Berg, Mette Louise (2015). "La Lenin is my passport": Schooling, mobility and belonging in socialist Cuba and its diaspora. Identities, 22(3), 303-317.

Bericat, Eduardo (2005). Sedentarismo nómada: El derecho a la movilidad y el derecho a la quietud [Sedentary nomads: The right to mobility and the right to stillness]. In Rosario Del Caz Enjuto, Mario Rodríguez & Manuel Saravia Madrigal (Eds.), El derecho a la movilidad: Informe de Valladolid [The right to mobility: Report from Valladolid] (pp.13-20). Valladolid: Universidad de Valladolid.

Canales, Manuel & Peinado, Anselmo (1995). Grupos de discusión [Discussion groups]. In Juan Manuel Delgado & Juan Gutiérrez (Coords.), Métodos y técnicas cualitativas de investigación en ciencias sociales [Qualitative research methods and techniques in social sciences] (pp.288-316). Madrid: Síntesis.

Canzler, Weert; Kaufmann, Vincent & Kesselring, Sven (2016). Tracing mobilities. Hampshire: Routledge.

Collin-Lange, Virgil (2014). "My car is the best thing that ever happened to me": Automobility and novice drivers in Iceland. Young, 22(2), 185-201, https://doi.org/10.1177/1103308814521620 [Date of access: December 10, 2024].

Cresswell, Tim (2006). On the move. Mobility in the modern Western world. New York, NY: Routledge.

Cresswell, Tim (2010). Towards a politics of mobility. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 28(1), 17-31.

den Besten, Olga (2010). Visualising social divisions in Berlin: Children's after-school activities in two contrasted city neighbourhoods. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 11(2), Art. 35, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-11.2.1488 [Date of access: January 7, 2025]

Denzin, Norman K. (1994). Romancing the text: The qualitative researcher-writer-as-bricoleur. Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education, 122, 15-30.

di Napoli, Pablo Nahuel & Iglesias, Andrea (2021). "¡Con los celulares en las aulas!" Un desafío para la convivencia en las escuelas secundarias de la Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires ["With cell phones in the classrooms!" A challenge for coexistence in secondary schools in Buenos Aires City]. Revista Latinoamericana de Estudios Educativos, 51(3), 11-44, https://doi.org/10.48102/rlee.2021.51.3.407 [Date of access: December 10, 2024].

Espinel-Rubio, Gladys & Feo-Ardila, Diana (2022). Territorio e identidad de resistencia en jóvenes del Catatumbo (Colombia), constructores de paces imperfectas [Territory and resistance identity in youth from Catatumbo (Colombia), builders of imperfect peace]. Investigación & Desarrollo, 30(1), 40-68, https://doi.org/10.14482/indes.30.1.303.661 [Date of access: December 10, 2024].

Fattore, Tobia; Fegter, Susann, & Hunner-Kreisel, Christine (2021). Refiguration of childhoods in the context of digitalization: A cross-cultural comparison of children's spatial constitutions of well-being. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 22(3), Art. 10, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-22.3.3799 [Date of access: January 7, 2025]

Fay, Michaela (2007). Mobile subjects, mobile methods: Doing virtual ethnography in a feminist online network. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 8(3), Art. 14, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-8.3.278 [Date of access: January 7, 2025]

Floristán-Millán, Elisa & Marmié, Cleo (2023). Navegando el gobierno transnacional de la infancia y juventud en movimiento. Una doble mirada cruzada: Harragas y aventureros entre España y Francia [Navigating the transnational government of childhood and youth in movement: A double crossed look: Harragas and adventurers between Spain and France]. Sociedad e Infancias, 7(1), 3-14, https://doi.org/10.5209/soci.87243 [Date of access: December 10, 2024].

García-Bastán, Guido (2023). Movilidades y experiencia escolar en la periferia urbana de Córdoba, Argentina [Mobilities and schooling in the urban periphery of Córdoba, Argentina]. Revista Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales, Niñez y Juventud, 21(3), 1-27, https://doi.org/10.11600/rlcsnj.21.3.5967 [Date of access: June 25, 2025]

García-Bastán, Guido & Paulín, Horacio Luís (2016). Identidades juveniles en escenarios de periferización urbana. Una aproximación biográfica [Youth identities in contexts of urban peripheralization. A biographical approach]. Quaderns de Psicología, 18(1), 35-52, https://doi.org/10.5565/rev/qpsicologia.1307 [Date of access: June 25, 2025]

García-Bastán, Guido; D'Aloisio, Florencia; Arce-Castello, Valentina; Bonansea, Natalia; Segovia, Natasha (2025). "En todo momento, en todo lugar". Movilidades digitales en la escuela secundaria ["Anytime, everywhere". Digital mobilities in secondary school]. In Silvia Alejandra Tapia (Ed.), Movilidades escolares (in)justas. Experiencias de jóvenes en escuelas secundarias de Buenos Aires, Córdoba y São Paulo [(Un)fair school mobilities. Youth experience in secondary schools of Buenos Aires, Córdoba and São Paulo] (pp.55-84). Buenos Aires: Teseo.

Gavazzo, Natalia; Beheran, Mariana & Novaro, Gabriela (2014). La escolaridad como hito en las biografías de los hijos de bolivianos en Buenos Aires [Schooling as a milestone in the biographies of the children of Bolivians in Buenos Aires]. Revista Interdisciplinar da Mobilidade Humana, 22(42), 189-212, https://doi.org/10.1590/S1980-85852014000100012 [Date of access: December 10, 2024].

Gerbaudo-Suárez, Débora (2018). Juventudes "latinoamericanas" en Buenos Aires. Luchas migrantes y configuraciones transnacionales de lo local [Latin American youth in Buenos Aires. Migrant struggles and transnational configurations of the local]. Argumentos, 15(1), 213-234, https://www.periodicos.unimontes.br/index.php/argumentos/article/view/1100 [Date of access: December 10, 2024].

Ghisiglieri, Francisco & Cardozo, Griselda (2022). Cartografía de prácticas de gobierno y subjetivación de jóvenes de sectores populares de Córdoba (Argentina) [Cartography of governance practices and subjectivation of youth from popular sectors in Córdoba (Argentina)]. Psicoperspectivas. Individuo y Sociedad, 21(2), 1-11, http://dx.doi.org/10.5027/psicoperspectivas-vol21-issue2-fulltext-2418 [Date of access: December 10, 2024].

Gordo-López, Ángel; García-Arnau, Albert; de-Rivera, Javier & Díaz-Catalán, Celia (2019). Jóvenes en la encrucijada digital: Itinerarios de socialización y desigualdad en los entornos digitales [Youth at the digital crossroads: Pathways of socialization and inequality in digital environments]. Madrid: Morata.

Gough, Katherine (2008). "Moving around": The social and spatial mobility of youth in Lusaka. Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography, 90(3), 243-255.

Granda, Indira (2024). La dimensión afectiva en la investigación de las migraciones infantiles: Metodologías bajo la lente [The affective dimension in the research of child migration: Methodologies under the lens]. REMHU: Revista Interdisciplinar da Mobilidade Humana, 32, e321835, https://doi.org/10.1590/1980-85852503880003206 [Date of access: December 10, 2024].

Groth, Sören; Hunecke, Marcel & Wittowsky, Dirk (2021). Middle-class, cosmopolitans, and precariat among millennials between automobility and multimodality. Transportation Research Interdisciplinary Perspectives, 12, 100467, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trip.2021.100467 [Date of access: December 10, 2024].

Gwaka, Leon Tinashe (2018). Digital technologies and youth mobility in rural Zimbabwe. The Electronic Journal of Information Systems in Developing Countries, 84(3), e12025, https://doi.org/10.1002/isd2.12025 [Date of access: December 10, 2024].

Hammond, Simon & Cooper, Neil (2016). Podwalking: A framework for assimilating mobile methods into action research. Qualitative Psychology, 3(2), 126-144.

Hein, Jane Ricketts; Evans, James & Jones, Phil (2008). Mobile methodologies: Theory, technology and practice. Geography Compass, 2(5), 1266-1285.

Hendel, Verónica (2020). Cartografías del peligro. Desplazamientos, migración, fronteras y violencias desde la experiencia de los jóvenes en un barrio del Gran Buenos Aires, Argentina (2018-2019) [Cartographies of danger. Displacements, migration, borders, and violence from the experience of youth in a neighborhood of Greater Buenos Aires, Argentina (2018-2019)]. Historia y Sociedad, 39, 184-212, https://doi.org/10.15446/hys.n39.82576 [Date of access: December 10, 2024].

Hendel, Verónica (2021). A lo largo de lo rural y lo urbano. Experiencias de movilidad territorial en perspectiva histórica (Gran Buenos Aires, 1930-2020) [Across the rural and the urban. Experiences of territorial mobility from a historical perspective (Greater Buenos Aires, 1930-2020)]. Revista Transporte y Territorio, 24, 149-171, https://doi.org/10.34096/rtt.i24.10231 [Date of access: December 10, 2024].

Hendel, Verónica & Maggi, María Florencia (2021). Mucho más que una elección [Much more than an election]. RUNA, 43(1), 95-112, https://doi.org/10.34096/runa.v43i1.10056 [Date of access: December 10, 2024].

Huiliñir-Curío, Viviana (2018). De senderos a paisajes: Paisajes de las movilidades de una comunidad mapuche en los Andes del sur de Chile [From paths to landscapes: Landscapes of the mobilities of a Mapuche community in the southern Andes of Chile], Chungará 50(3), 487-499, http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0717-73562018005001301 [Date of access: December 10, 2024].

Kates, Aaron; Wu, Huang & Coryn, Chris (2018). The effects of mobile phone use on academic performance: A meta-analysis. Computers & Education, 127, 107-112.

Kieslinger, Julia; Kordel, Stefan & Weidinger, Tobias (2020). Capturing meanings of place, time and social interaction when analyzing human (im)mobilities: Strengths and challenges of the application of (im)mobility biography. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 21(2), Art. 7, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-21.2.3347 [Date of access: January 7, 2025].

Krumpal, Ivar (2013). Determinants of social desirability bias in sensitive surveys: A literature review. Quality & Quantity, 47(4), 2025-2047.

Lahire, Bernard (2007). Infancia y adolescencia: De los tiempos de socialización sometidos a constricciones multiples [Childhood and adolescence: Times of socialization subjected to multiple constraints]. Revista de Antropología Social, 16(1), 21-37, https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/838/83811585002.pdf [Date of access: December 10, 2024].

Lainé, Alex (1998). Faire de sa vie une histoire. Théories et pratiques de l'histoire de vie en formation [Making one's life a story: Theories and practices of life history in education]. París: Desclée de Brouwer.

Lasén-Díaz, Amparo (2018). Disruptive ambient music: Mobile phone music listening as portable urbanism. European Journal of Cultural Studies, 21(1), 96-110.

Latour, Bruno (2005). Reassembling the social. An introduction to actor-network-theory. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Leander, Kevin; Phillips, Nathan & Taylor, Katherine (2010). The changing social spaces of learning: mapping new mobilities. Review of Research in Education, 34(1), 329-394.

Leclerc-Olive, Michelle (2009). Temporalidades de la experiencia: Las biografías y sus acontecimientos [Temporalities of experience: Biographies and its events]. Iberoforum, 4(8), 1-39, https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=211014822001 [Date of access: April 10, 2025].

Lefebvre, Henri (1969 [1968]). El derecho a la ciudad [The right to the city]. Barcelona: Península.

Lefebvre, Henri (1991 [1974]). The production of space. Oxford: Blackwell.

Ley, Judith & Solorio, Carlos (2024). Lugares ambivalentes: El espacio vivido de las juventudes urbanas en ciudades fronterizas [Ambivalent places: The lived space of urban youth in border cities]. EURE, 50(150), 1-21. http://dx.doi.org/10.7764/eure.50.150.04 [Date of access: December 10, 2024].

Leyshon, Michael; DiGiovanna, Sean & Holcomb, Briavel (2013). Mobile technologies and youthful exploration: Stimulus or inhibitor?. Urban Studies, 50(3), 587-605.

Lind, Birgitte & Agergaard, Jytte (2010). How students fare: Everyday mobility and schooling in Nepal's Hill Region. International Development Planning Review, 32(3-4), 311-331.

Lindgren, Joakim & Lundahl, Lisbeth (2010). Mobilities of youth: Social and spatial trajectories in a segregated Sweden. European Educational Research Journal, 9(2), 192-207, https://doi.org/10.2304/eerj.2010.9.2.192 [Date of access: December 10, 2024].

Linne, Joaquín (2018). Nomadización, ciudadanía digital y autonomía. Tendencias juveniles a principios del siglo XXI [Nomadization, digital citizenship and autonomy. Youth trends in the beginnings of the 21st century]. Casqui, 137, 39-52, https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=6578577 [Date of access: June 25, 2025].

Maggi, María Florencia & Hendel, Verónica (2022). Relaciones intra e intergeneracionales de jóvenes en movimiento con familias migrantes (Argentina) [Intra and intergenerational relationships of youth in movement with migrant families (Argentina)]. Revista Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales, Niñez y Juventud, 20(3), 1-24, https://doi.org/10.11600/rlcsnj.20.3.4811 [Date of access: December 10, 2024].

Marioni, Lucía & Schmuck, Emilia (2019). Jóvenes rurales: Trabajos y movilidades espaciales en una region hortícola en Argentina [Rural youth: Work and spatial mobilities in a horticultural region in Argentina]. Revista de Ciencias Sociales, 1(163), 117-130, https://www.redalyc.org/journal/153/15359603008/html/ [Date of access: December 10, 2024].

Marques, Gilda & Souza, María Celeste (2019). The perception of adult and young adult students on the river Rio Doce—Cartographies of fear. Ambiente & Sociedade, 22, e0327, https://doi.org/10.1590/1809-4422asoc0327vu19L4AO [Date of access: December 10, 2024].

Martínez, Darío Gabriel (2023). Escalas interconectadas de movilidades. Modos de habitar el espacio en una escuela secundaria agrarian [Interconnected scales of mobilities. Ways of inhabiting space in an agricultural secondary school]. Educación y Vínculos. Revista de Estudios Interdisciplinarios en Educación, 6(12), 124-139, https://doi.org/10.33255/2591/1747 [Date of access: December 10, 2024].

Maxwell, Joseph Alex (2012 [1996]). Qualitative research design: An interactive approach. Washington DC: Sage.

Maxwell, Joseph Alex (2012). The importance of qualitative research for causal explanation in education. Qualitative Inquiry, 18(8), 655-661.

McAuliffe, Cameron (2013). Legal walls and professional paths: The mobilities of graffiti writers in Sydney. Urban Studies, 50(3), 518-537.

Monaco, Salvatore (2018). Tourism and the new generations: Emerging trends and social implications in Italy. Journal of Tourism Futures, 4(1), 7-15, https://doi.org/10.1108/JTF-12-2017-0053 [Date of access: December 10, 2024].

Navarrete, María José (2022). La relación movilidades y desigualdades, aportes desde las investigaciones en ciencias sociales y humanas [The relationship between mobilities and inequalities: Contributions from research in social and human sciences]. Revista Transporte y Territorio, 26, 1-17, https://doi.org/10.34096/rtt.i26.12123 [Date of access: December 10, 2024].

Paulín, Horacio Luís; García-Bastán, Guido; D'Aloisio, Florencia & Carreras, Rafael Antonio (2018). Contar quienes somos. Narrativas juveniles por el reconocimiento [To tell who we are. Youth narratives for recognition]. Buenos Aires: Teseo.

Paulín, Horacio Luís; Tomasini, Marina; D'Aloisio, Florencia; López, Carlos Javier; Rodigou-Nocetti, Maite & García-Bastán, Guido (2011). La representación teatral como dispositivo de investigación cualitativa para la indagación de sentidos sobre la experiencia escolar con jóvenes [Theatrical performance as a qualitative research tool to explore youth's meanings of school experience]. Psicoperspectivas, 10(2), 134-155, https://doi.org/10.5027/psicoperspectivas-Vol10-Issue2-fulltext-149 [Date of access: June 25, 2025]

Pelikh, Alina & Kulu, Hill (2018). Short and long-distance moves of young adults during the transition to adulthood in Britain. Population, Space and Place, 24(5), e2125.

Ramos, Daniela; Movilla, José; Rozo, Ángela & Rodríguez, Carla (2022). El uso de la cartografía social teatral con niños y niñas de Fómeque y Choachí, Colombia [The use of theatrical social mapping with children from Fómeque and Choachí, Colombia]. Letras Verdes, Revista Latinoamericana de Estudios Socioambientales, 31, 95-114, https://doi.org/10.17141/letrasverdes.31.2022.5063 [Date of access: December 10, 2024].

Riquelme-Brevis, Hernán; Saravia-Cortés, Felipe & Azócar-Weisser, Javiera (2024). Movilidad cotidiana e interurbana en contextos de exclusión socioespacial al sur de Chile. Aportes para pensar los territorios no metropolitanos en América Latina [Everyday and interurban in contexts of socio-spatial exclusion in Southern Chile. Contributions for thinking about non-metropolitan territories in Latin America]. Revista Cuhso, 29(2), 80-108, https://doi.org/10.7770/cuhso-v29n2-art1903 [Date of access: December 10, 2024].

Ross, Nicola; Renold, Emma; Holland, Sally & Hillman, Alexandra (2009). Moving stories: Using mobile methods to explore the everyday lives of young people in public care. Qualitative Research, 9(5), 605-623.

Rye, Johan Fredrik (2011). Youth migration, rurality, and class: A Bourdieusian approach. European Urban and Regional Studies, 18(2), 170-183.

Salvidge, Nathan (2022). Reflections on using mobile GPS with young informal vendors in urban Tanzania. Area, 54(3), 418-426, https://doi.org/10.1111/area.12782 [Date of access: December 10, 2024].

Sánchez-Blanco, Concepción (2013). Infancias nómadas. Educando el derecho a la movilidad [Nomadic childhoods. Educating the right to mobility]. Buenos Aires: Miño & Dávila.

Sánchez-García, José; Oliver, María; Mansilla, Juan; Hansen, Nele & Feixa, Carles (2020). Entre el ciberespacio y la calle: Etnografiando grupos juveniles de calle en tiempos de distanciamiento físico [Between cyberspace and the street: Ethnographing street youth groups in times of physical distancing]. Hipertext.net, 21, 93-104, https://doi.org/10.31009/hipertext.net.2020.i21.08 [Date of access: December 10, 2024].

Sander, Marie (2016). Passing Shanghai. Ethnographic insights into the mobile lives of expatriate youths. Heidelberg: Heidelberg University Publishing.

Savegnago, Sabrina (2020). Mobilidades de jovens de grupos populares do Rio de Janeiro em relação à rua e a casa [Mobilities of youth from popular groups in Rio de Janeiro in relation to street and home]. CES Psicología, 13(1), 52-69, https://doi.org/10.21615/cesp.13.1.4 [Date of access: December 10, 2024].

Schmuck, María Emilia (2021). "Somos jóvenes y estudiantes del campo". Una etnografía sobre experiencias formativas y educación secundaria en el norte entrerriano ["We are youth and students from the countryside". An ethnography on formative experiences and secondary education in northern Entre Ríos]. Revista de la Escuela de Ciencias de la Educación, 1(16), 136-140, https://doi.org/10.35305/rece.v1i16.594 [Date of access: December 10, 2024].

Schreier, Margrit (2018). Sampling and generalization. In Uwe Flick (Ed.), The Sage handbook of qualitative data collection (pp.84-97). London: Sage.

Segura, Ramiro (2017). Ciudad, barreras de acceso y orden urbano [City, access barriers and urban order]. Revista Argentina de Estudios de Juventud, 11, 016, https://doi.org/10.24215/18524907e016 [Date of access: December 10, 2024].

Severinsson, Susanne; Nord, Catharina & Reimers, Eva (2015). Ambiguous spaces for troubled youth: Home, therapeutic institution, or school?. Pedagogy, Culture & Society, 23(2), 245-264.

Sheller, Mimi & Urry, John (2006). The new mobilities paradigm. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 38(2), 207-226.

Sheller, Mimi & Urry, John (2016). Mobilizing the new mobilities paradigm. Applied Mobilities, 1(1), 10-25.

Sierra, Angélica & Solano, Alex (2021). Movilidad residencial y social en barrios populares consolidados en Bogotá [Residential and social mobility in consolidated popular neighborhoods in Bogotá]. Urbe. Revista Brasileira de Gestão Urbana, 13, e20200109, https://doi.org/10.1590/2175-3369.013.e20200109 [Date of access: December 10, 2024].

Silva, Ananda; Santos, Vania & Coltri, Priscila (2024). Percepção de riscos de desastres entre alunos de escola pública: Contribuições à ciência cidadã e à aprendizagem social [Perception of disaster risks among public school students: Contributions to citizen science and social learning]. Pro-Posições, 35, e20240805BR, https://doi.org/10.1590/1980-6248-2023-0074BR [Date of access: December 10, 2024].

Simón, Cecilia; Giné, Climent & Echeita, Gerardo (2016). Escuela, familia y comunidad: Construyendo alianzas para promover la inclusión [School, family, and community: Building alliances to promote inclusion]. Revista Latinoamericana de Educación Inclusiva, 10(1), 25-42, https://doi.org/10.4067/s0718-73782016000100003 [Date of access: December 10, 2024].

Skelton, Tracey (2013). Young people's urban im/mobilities: Relationality and identity formation. Urban Studies, 50(3), 467-483.

Tapia, Silvia Alejandra (2018). "No me agrada viajar". Moverse en la ciudad como desafío cotidiano para jóvenes de barrios populares de Buenos Aires ["I don't like traveling". Moving around the city as an everyday challenge for youth from working-class neighborhoods in Buenos Aires]. Última Década, 26(48), 201-233, https://doi.org/10.4067/s0718-22362018000100201 [Date of access: December 10, 2024].

Tapia, Silvia Alejandra (2023). Juventudes, movilidades espaciales e (in)justicias educativas. Investigaciones sobre desigualdades y escuela secundaria en Argentina [Youth, spatial mobilities, and (in)justice in education. Research on inequalities and secondary education in Argentina]. Cronía, 19, 1-10, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10055877 [Date of access: December 10, 2024].

Tapia, Silvia Alejandra (2025). Movilidades escolares (in)justas. Experiencias de jóvenes en escuelas secundarias de Buenos Aires, Córdoba y São Paulo [(Un)fair school mobilities. Youth experience in secondary schools of Buenos Aires, Córdoba and São Paulo]. Buenos Aires: Teseo Press.

Tiramonti, Guillermina (2004). La trama de la desigualdad educativa [The plot of educational inequality]. Buenos Aires: Manantial.

UNESCO (2023). Global education monitoring Report 2023: Technology in education: A tool on whose terms?. Paris: UNESCO, https://doi.org/10.54676/UZQV8501 [Date of access: December 10, 2024]

Urry, John (2002). Mobility and proximity. Sociology, 36(2), 255-274.

Van-Blerk, Lorraine (2013). New street geographies: The impact of urban governance on the mobilities of cape town's street youth. Urban Studies, 50(3), 556-573, https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098012468895 [Date of access: December 10, 2024].