Volume 26, No. 2, Art. 26 – May 2025

Using Arts-Based Methods in Disability Research

Angela Dew & Louisa Smith

Abstract: The use of arts-based methods has been increasingly reported in social sciences, education, health and more recently, disability research. Arts-based research methods offer the potential for researchers and research participants to communicate what cannot be captured in words. In this paper we present a range of arts-based methods used in our research with people with disabilities and their supporters. We explore the background of arts-based methods for disability research and then present five case studies of arts-based methods we have used across our research: Found poetry, body mapping, community mapping, 3D artefacts and photovoice. In unpacking these different examples, we highlight the ways in which arts-based methods help to capture the embodied, emotional and overlapping experiences of people with disability or their supporters. Engaging with the arts-based method empowered participants with diverse experiences of disability—from intellectual disability to dementia—to make choices and determine the ways in which they engaged with the research subject and the topic. Despite some logistical, analytical and ethical challenges, arts-based methods offer disability research powerful tools for accessible engagement and knowledge translation.

Key words: arts-based research; participatory action research; qualitative research; disability; ethical considerations

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. History of Arts-Based Research Methods

3. Overview of Benefits of Arts-Based Approaches

4. Overview of Challenges of Arts-Based Approaches

4.1 Logistical challenges

4.2 Analysis challenges and potential solutions

4.3 Ethical challenges

5. Our Application of Arts-Based Methods in Disability Research

5.1 Found poetry (literary method)

5.2 Body mapping (visual method)

5.3 Community mapping (visual method)

5.4 Found objects and crafting (3D artefacts)

5.5 Photovoice (visual method)

6. Discussion

7. Conclusion

Researchers are increasingly using arts-based methods in qualitative social research. BOYDELL, GLADSTONE, VOLPE, ALLEMANG and STASIULIS in their scoping review defined arts-based methods in health research as the "... use of any art form (or combinations thereof) at any point in the research process […] in generating, interpreting and/or communicating knowledge" (2012a, §5). Arts-based research methods have become popular as ways for researchers to generate rich and descriptive data which communicate participants' subjective and embodied experiences, enhance participant control over the research process, and highlight features of lived experience which may have been overlooked or ignored previously (BOYDELL et al., 2012a; HARASYM, GROSS, MacLEOD & PHELAN, 2024; NATHAN et al., 2023). As succinctly described by Norwegian dementia researchers, MITTNER and GÜRGENS GJÆRUM (2022, p.5), "[m]utuality, reciprocity, relationality, communality, and connectivity are qualities which the arts bring into the research process". In short, researchers' use of arts-based methods fosters a research environment in which "researcher" and "participant" meet outside of these prescribed roles, instead co-creating knowledge and understanding. [1]

As sociologists and disability scholars, in this paper we explore the benefits of applying a range of arts-based methods across a variety of research projects involving people with diverse experiences of disability—from intellectual disability to dementia—and/or their supporters (family members or formal carers). People with disability report experiencing marginalisation in many aspects of their lives including engagement in research where they may be the subjects of study rather than equal contributors. [2]

We begin this paper with an overview of the history of arts-based research methods over the past four decades (Section 2). In Section 3 we describe the benefits and in Section 4, the challenges of using arts-based approaches. In Section 5, we present five arts-based methods—found poetry, body mapping, community mapping, 3D artefacts and photovoice. We use these case studies to highlight the capacity and flexibility of these methods to serve different purposes and engage a diversity of people while also telling powerful stories of disability experiences. In Section 6, we relate the challenges highlighted in Section 4 to the case study examples in Section 5 and include some guidance for disability researchers wishing to use arts-based methods. We provide a brief conclusion in Section 7. [3]

2. History of Arts-Based Research Methods

Globally, researchers have formally documented the arts as a way to communicate research results for at least 40 years (FRASER & AL SAYAH, 2011). Researchers using art to generate, as well as disseminate, research data is a more recent phenomenon with COEMANS and HANNES (2017) and WANG, COEMANS, SIEGESMUND and HANNES (2017), noting that the term arts-based research was first used in 1993 at an educational conference held at Stanford University, USA. The conference organiser coined this term to describe the use of the arts to actively engage education students in curriculum. Arts-based methods remained on the fringes of research methodology until a recent focus on these methods recognised creative ways to produce and disseminate research knowledge (BOYDELL et al., 2012a; COEMANS & HANNES, 2017). This recognition of arts-based methods may, at least in part, stem from the now widespread acceptance of more traditional qualitative research methods, which were themselves not so long ago, considered fringe. The emergence of arts-based methods is also in response to researchers identifying the limitations of using traditional qualitative methods with some participant groups including people with disability who may not be able to engage in interviews and focus groups due, for example to communication and language challenges (DEW, SMITH, COLLINGS & DILLON SAVAGE, 2018). [4]

A significant increase in the use of arts-based methods in health research over two decades was noted by COX et al. (2010) in their overview of Canadian arts-based health research. COX et al. described arts-based health research methods as being used throughout a research project including in data collection, analysis and meaning making, and dissemination. The increasingly common use of social media and information technology (IT) over the past decade has further elevated the profile of arts-based research methods as noted in a study by HARASYM et al. (2024) who used arts-based research methods with young people experiencing post-concussion communication changes. HARASYM et al. noted that "[i]n this digital age, visual and creative works quickly and impactfully communicate messages to a broad audience. Researchers are beginning to harness the transformative and translational power of the arts" (p.2). Similarly, in a narrative literature review of 25 articles reporting on the use of arts-based research methods with young people with complex psychosocial needs, NATHAN et al. (2023) described the use of social media and technology as emancipatory arts-based methods with participant empowerment and the creation of knowledge as key outcomes. [5]

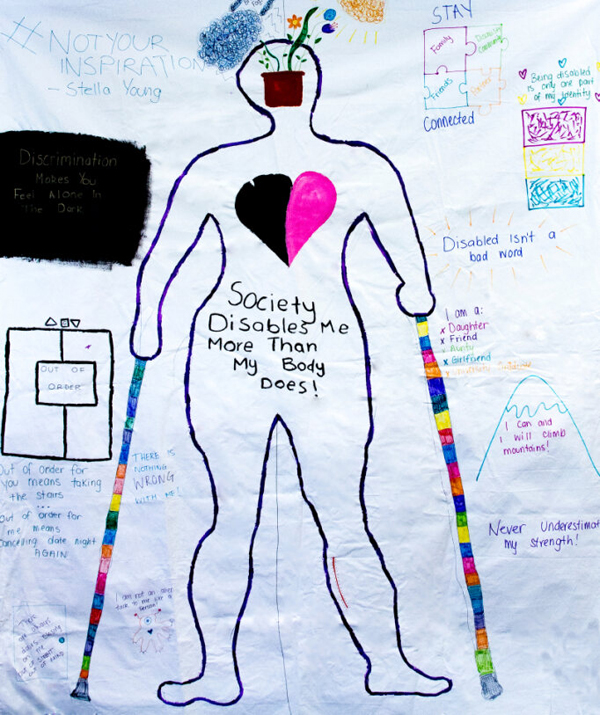

Within the contemporary context, researchers typically categorise arts-based methods under three broad headings: Visual, performative and literary (FRASER & AL SAYAH, 2011). A combination of methods may also be used within a single research project. Visual methods include the creation of still images (e.g. photovoice where participants take photos to illustrate their experience of the topic; photo-elicitation which incorporates photos into interviews to stimulate discussion; body-mapping described in detail below; murals; and drawing), moving images (e.g. videos and digital storytelling), and 3D artefacts (e.g. quilts, memory boxes, Found Objects). Performative research methods include drama, dance and music (MITTER & GÜRGENS GJÆRUM, 2022; NATHAN et al., 2023). In literary research methods, written language forms such as poetry and prose are used (COEMANS & HANNES, 2017; FRASER & AL SAYAH, 2011). [6]

Disability researchers have been relatively slow in adopting arts-based methods. This is surprising given the identified benefits of arts-based research for engaging participants whose complex communication needs or perceived cognitive capacity resulted in their exclusion from research, meaning their experiences and opinions were absent (HARASYM et al., 2024). In the last decade, a small but growing number of disability scholars have published on their application of arts-based methods with people with disability due largely to the perceived benefits (e.g. BURCH, 2022; BURNS & WAITE, 2019; MITTNER & GÜRGENS GJÆRUM, 2022; OVERMARS-MARX, THOMESE & MOONEN, 2018). [7]

3. Overview of Benefits of Arts-Based Approaches

In their scoping review of arts-based health research methods, BOYDELL et al. (2012a) identified four main benefits of using arts-based approaches as:

An opportunity to enhance research participant and audience engagement;

A way to enrich communication;

A means to make research accessible beyond the academic community;

A way of generating data beyond the scope of other methods. [8]

Additionally, BOYDELL et al. highlighted the benefits of arts-based research approaches for providing rich and detailed information about participants' subjective lived experiences which may not otherwise be recognised. Similarly, VAN DER VAART, VAN HOVEN and HUIGEN (2018) described arts-based methods as creating "multi-faceted knowledge" (§3) to generate deep insight and offer ways to give back to individual participants and communities. [9]

Researchers often use arts-based methods with marginalised groups whose views may not otherwise be represented in research. For example, COLLINGS, CONLEY WRIGHT and SPENCER (2021a) employed body mapping to explore the birth contact experiences of 12 mothers whose children were in permanent care. DE SMET, SPAAS, SMITH JERVELUND, SKOVDAL and DE HAENE (2024) and MOREIRA and JAKOBI (2021) involved people from refugee backgrounds in their research. MITTNER and GÜRGENS GJÆRUM (2022) and SMITH and PHILLIPSON (2021), SMITH, PHILLIPSON and KNIGHT (2023), and SMITH, CARR, CHESHER and PHILLIPSON (2025) conducted research with people living with dementia. Significantly for marginalised groups, researchers and participants both report that arts-based methods increase research participant control and level the power differential between them (BOYDELL et al., 2012a; BROWN, SPENCER, McISAAC & HOWARD, 2020; COEMANS & HANNES, 2017; DE SMET, SPAAS, SMITH JERVELUND, SKOVADAL & DE HAENE, 2024; HARASYM et al., 2024; NATHAN et al., 2023; VAN DER VAART et al., 2018). Importantly, COEMANS and HANNES (2017) noted that research participants said that using arts-based methods made participating both accessible and fun. According to COLLINGS et al. (2021a, p.892), some of their participants explained that

"... uninterrupted time spent in reflection on their experiences had left them with a sense of lightness and expressed surprise and pride in the beautiful images they had created. The opportunity to reflect on painful experiences in a supported and safe environment appeared to provide at the very least momentary repair." [10]

Furthermore, in an article reporting on research into the use of drama-based mental health interventions with young people from refugee backgrounds living in Belgium and Denmark, DE SMET et al. (2024, p.337) described arts-based methods as having the potential to be decolonising and strengths-based noting that these methods "up-end unequal positions of power typical of research relationships that can counter experiences of structural violence such as discrimination and stigmatization". [11]

In line with the above, researchers have noted that the use of arts-based methods is often associated with participatory, emancipatory, community-based and action research approaches frequently employed in conjunction with traditional qualitative methods such as interviews, focus groups and observations (COEMANS & HANNES, 2017; VAN DER VAART et al., 2018; NATHAN et al., 2023). In keeping with qualitative constructivist epistemologies, researchers report that arts-based methods can encourage the use of a critical lens to interrogate structural power differentials in order to influence social policy and advocate for social change (BOYDELL et al., 2012a; COEMANS & HANNES, 2017). Additionally, some scholars highlighted that arts-based methods can challenge the use of traditional colonial research methodologies. Australian historian CLARK (2022) noted that Indigenous people have always used multi-modal forms—music, dance, painting, mark making, weaving, carving—to produce and pass on knowledge within communities. Aboriginal scholars in Australia, MANNING BANCROFT (2023) and YUNKAPORTA (2023) described the cultural importance to their research of using arts-based practices as a way of both knowing and imagining. That said, non-Indigenous researchers need to take the lead from Indigenous colleagues and communities to adopt methods that will work best for Indigenous researchers and participants (DEW, McENTYRE & VAUGHAN, 2019a). [12]

Arts-based methods are recognised as highly flexible and able to be used in a variety of contexts (DE SMET et al., 2024; MOREIRA & JAKOBI, 2021; VAN DER VAART et al., 2018). For example, reporting on a meta-study of the use of arts-based interventions for social inclusion of people from refugee and asylum seeker backgrounds, MOREIRA and JAKOBI (2021) noted that the use of arts in research, while not its primary aim, can be therapeutic helping people to deal with past traumatic events and promoting human connection for both individuals and communities. Similarly, DE SMET et al. (2024) reported that the use of arts-based methods fostered participants from refugee background's positive coping strategies and promoted their wellbeing. BURCH's (2022) study in the United Kingdom involved 79 participants who identified as having an intellectual and/or physical disability creating mood boards using collage, drawing and words to tell their experiences of disability hate crimes. Similar to the experiences reported earlier by COLLINGS et al. (2021a), BURCH identified that using an arts-based method provided a therapeutic space for participants to "revisit personal experiences, prompt sensitive and supportive discussions, and present knowledge in more creative ways" (2022, p.398). Similarly, NATHAN et al. (2023) noted that several of the studies in their narrative review mentioned the therapeutic benefits of using arts-based methods with young people with complex psychosocial needs. These benefits included enhanced feelings of self-worth and self-efficacy and increased resiliency and optimism for the future. [13]

4. Overview of Challenges of Arts-Based Approaches

While acknowledging the many benefits of using arts-based methods in research, there are also challenges evident for both research participants and researchers. Research participants may feel additional anxiety due to a concern about their perceived lack of artistic ability (BURCH, 2022; COLLINGS et al., 2021a). Once fully engaged in the activity, many participants reported enjoying the experience and reflected on the benefits of the approach as freeing them up to express themselves in different ways beyond reliance on words (BAGNOLI, 2009; COLLINGS et al., 2021a; DE SMET et al., 2024; HARASYM et al., 2024). Because of the creative and deeply personal nature of artmaking, participants may feel disempowered if, due to ethics approval requirements, they are not able to be publicly identified as the artist or creator (HARASYM et al., 2024). We explore this challenge in more detail within the ethical considerations section noting the need to negotiate this with participants early in the research process as was done in the photovoice project described in Section 5. [14]

The challenges experienced by researchers included the additional time and resources often required to conduct arts-based research (HARASYM et al., 2024; NATHAN et al., 2023). DEW, TEWSON, CURRYER and DILLON SAVAGE (2021) devoted a chapter to body mapping logistics in a book edited by BOYDELL (2021). We identified decisions about which art materials to use, the physical space required to conduct the method, the accessibility of the space and method and adaptations required, the time necessary for pre-planning, implementation and dissemination, and the ongoing storage of often bulky and/or fragile arts data. While DEW et al. (2021) focused on the specific arts-based method of body mapping, many of the issues raised are common across other arts-based methods (HARASYM et al., 2024). [15]

4.2 Analysis challenges and potential solutions

Researchers have identified that the analysis of arts-based data and their incorporation with associated traditional data sources such as interview transcripts, is underdeveloped and presents specific challenges. COLLINGS, DEW, CURRYER, DILLON SAVAGE and TEWSON noted that the collection of arts-based data alongside other data sources "can present researchers with a potentially large volume of data sourced from multiple modes of interactions with research subjects" (2021b, p.57). As a result of the uncertainly about how to analyse arts-based data, researchers may focus their analysis on the written data component using established qualitative approaches (e.g. thematic or narrative analysis). The extensively cited thematic analytical framework applied to textual data developed by BRAUN and CLARKE (2006, 2013) was the most commonly used method reported in almost all disability research articles we cite. Yet often, the analysis of the visual data was overlooked or not reported (e.g. BURCH 2022). We agree with BAGNOLI and CLARK (2010) that all data sources must be incorporated into the analysis as they contribute equally to the research results. MITTNER and GÜRGENS GJÆRUM (2022) argued that ideally analysis starts during the arts-based activities and continues throughout the research as a collaboration between researchers and participants/co-researchers. They coined the term "aesthetic analysis" to describe the collective, improvised and sensory process of analysing "micro moments documented in the field" (p.16) which, MITTNER and GÜRGENS GJÆRUM said "makes it almost impossible to distinguish data generation, data analysis and research dissemination as separate phases" (p.19). [16]

ROSE (2016) was one of the first, and subsequently most cited, researchers to consider the interpretation of visual data and her work is seminal for combining visual and content analysis. Typically, textual data are first analysed using established coding techniques to group similar ideas and experiences. Visual data (e.g. photos, body maps) are then analysed by dividing each image into sections to examine and attribute meaning to each part. [17]

Specific to body mapping, ORCHARD (2017) developed an analysis method called axial embodiment whereby, similar to ROSE's approach, the data contained on a body map are divided into layers and each image, collage or text is counted across the layers and then tabulated to show the total numbers according to placement on the body map. A weakness with this method is that, by dissecting the body map into layers, continuity of use of particular images may be lost along with the temporal way in which maps are created. COLLINGS et al. (2021a) tried and abandoned applying ORCHARD's axial coding approach in their study noting that where participants placed images on the maps seemed more related to their physical proximity to certain parts of the map at the time. They instead developed a bespoke template on which they plotted images and symbols related to identified child removal transition points. [18]

Based on KOHLER RIESSMAN (2005), narrative analysis methods may also be used to analyse both text-based and arts-based data (COLLINGS et al., 2021b). An advantage of a narrative analytical approach is that participants' stories (told both verbally and through arts methods) are maintained intact rather than fractured as is common in content and thematic analysis approaches. A combined narrative, visual and content analysis approach was used in the body mapping study conducted by second author Louisa SMITH and Leanne DOWSE who applied CHARMAZ's (2006) constructivist grounded theory approach to develop themes, along with ROSE's (2016) visual content analysis approach "to articulate the depth and breadth of the young people's experiences of transition" (SMITH & DOWSE, 2019, p.1332). The application of integrated approaches to arts-based data analysis seems to offer the greatest benefit to researchers to ensure that both text and visual data are accounted for. We concur with FRASER and AL SAYAH (2011) who, more than a decade ago, identified the need for ongoing discussion about appropriate ways to analyse arts-based data in order to guide researchers. [19]

Throughout the research process, ethical considerations are paramount as they influence the development, presentation and response to a study. There are particular ethical issues important for researchers, participants and audiences involved in arts-based research (HARASYM et al., 2024; NATHAN et al., 2023). Ethical considerations are pertinent for researchers not just in planning for arts-based activities but, as noted by BOYDELL et al. (2012b, p.3) there is a "need for researchers to maintain a critical awareness of emergent ethical dilemmas throughout the process". HARASYM et al. (2024) also highlighted the need for ongoing ethics consent noting potential future impacts on participants when personal materials and details are shared in publications. NATHAN et al. (2023) warned of the potential danger of re-traumatising participants by exploring traumatic experiences through art-making. BOYDELL et al. (2012b, pp.7-13) identified five key ethical considerations in planning and conducting arts-based research:

Authorship/ownership of the work during and after its creation;

"Truth" interpretation and representation—attending to the inherent risk of audience and end-users' misinterpretation of the art-creators' intended message;

Informed consent/anonymity/confidentiality—not all arts-based research participants wish to remain anonymous and publication of images often makes this difficult. Choice about being identified as the author of the work should be respected but at the same time, discussion should occur about the long-term consequences of this decision;

Dangerous emotional terrain explored may have unintended consequences for participants, researchers and audiences;

Issues of aesthetics—the benchmark for arts-based research products is about how well they represent the issue under study and relate to its aims and context. [20]

Reflective of the third ethical consideration described by BOYDELL et al., HARASYM et al. (2024) grappled with the dilemma of preserving participant confidentiality or providing participants with the choice of being recognised for their arts-based contributions. They provided participants with consent materials specifying both how they wished to be credited (including use of their full real name) and where materials could be shared (e.g. publications, presentations). HARASYM et al. also noted that in honouring these decisions, "Ongoing reflexive dialogue is essential to authentically reflect participants' stories while maintaining privacy and anonymity" (p.13). [21]

SANTINELE MARTINO and FUDGE SCHORMANS (2018) highlighted specific ethical challenges when conducting research with people who identify as having an intellectual or learning disability. While acknowledging the need for ethical oversight to ensure participants with intellectual/learning disability understand the research aims and what their participation will entail, the authors warned that too often research ethics review processes undermine the autonomy and agency of people with intellectual/learning disability to consent to participation. SANTINELE MARTINO and FUDGE SCHORMANS suggested that ethics review committees need education about the rights of people with intellectual/learning disability to contribute to research that is about their lives, citing the disability rights mantra, "[n]othing about us without us" (§4). The authors noted that collaborative research methodologies, such as arts-based, are important avenues for recognising and valuing the active participation of people with intellectual/learning disability in research. HARASYM et al. (2024, p.13) pointed out that due to their very nature, arts-based research methods require spontaneous decisions to be made in response to what they called "ethical moments" which can occur throughout the research process. [22]

5. Our Application of Arts-Based Methods in Disability Research

In our work we have used literary and visual arts-based research methods across multiple projects with a range of people with disability and their supporters (family and formal carers) to explore a diversity of topic areas. All the research projects reported on in this section received ethics approval from relevant university human ethics research committees. [23]

5.1 Found poetry (literary method)

Found poetry is a literary method which takes existing texts including research transcripts and refashions, reorders, and presents them as poems. A pure found poem consists exclusively of these texts with the words of the poem remaining as they were found, with few additions or omissions. Decisions of form, such as where to break a line, are left up to the poem creator (WALMSLEY, COX & LEGGO, 2017). As an arts-based research method, creating found poems from interview transcripts has been used by researchers as a form of analysis (WIGGINS, 2011) and knowledge translation (MILLER, 2025), succinctly condensing key ideas or messages from the research in ways that can be communicated to a larger audience and help to engage their imagination and emotion (RICH, 2024) and incite changes in perspective (EDGE & OLAN, 2021). In our case, found poetry was used to both deepen analysis of an emotional theme and represent and share this with broader audiences in a way that enacted the emotional impact. Angela DEW and colleagues investigated access to therapy services for people with disability living in rural and remote geographic areas of Western New South Wales (NSW), Australia (DEW et al., 2013). Over five years DEW and colleagues interviewed 79 carers all of whom recounted their family member's disability diagnosis. Regardless of how long ago the diagnosis had occurred, all had detailed memories of this life-changing event which they told us as an introduction to discussing their family member's current circumstances. The research team experimented with the literary arts-based method of found poetry to represent and disseminate these diagnosis narratives. Figure 1 is a found poem collaboratively written by the research team based on a rural mother's interview transcript recalling her son's diagnosis of Down syndrome (DEW, 2019).

|

My son was born |

|

|

|

|

in a rural town |

Transferred down He may have Down's He may have Down's |

|

I didn't get told nothing |

|

|

|

|

Didn't get told the next day |

|

|

|

|

until |

|

|

|

3 o'clock |

|

I didn't know anything |

|

|

|

|

Confirmed has Down's |

|

|

|

|

got to come back down |

|

taken him away |

|

|

|

|

Incubator oxygen |

|

|

They wouldn't tell me nothing |

|

|

|

|

in a rural town |

|

Figure 1: Diagnosis found poem [24]

The poem uses words directly from the interview transcript capturing the mother's feelings of not being told anything about her son's disability, of him being taken away from her for medical treatment in the city and about finding out that he had Down syndrome. The poetic rendering is powerful, helping others connect with the experience of this mother. We used this and other found poems from study participants in training rural allied health practitioners and students. The poems helped practitioners and students understand the experience of diagnosis from the perspective of rural parents—the distress caused by withholding information, the anxiety of waiting for news, the confusion about treatment for their baby—and to reflect on their own current or future practice. [25]

5.2 Body mapping (visual method)

As noted previously, a particular strength of using arts-based methods with people with disability during data collection is reduced reliance on verbal communication and enabling participants to explore sensitive and controversial topics often difficult to articulate verbally (HARASYM et al., 2024). BAGNOLI (2009, p.547) described this as "not all knowledge is reducible to language". An example is the visual method of body mapping which both authors have used in multiple, separate research projects. Body mapping involves participants drawing or having drawn around them a life-sized outline of their body or a symbol of their body which they then decorate using drawing, painting, collage and writing to depict their experience of the research topic (BOYDELL, 2021; DE JAGER, TEWSON, LUDLOW & BOYDELL, 2016). A written account, known in body mapping as a testimonia, captures the experience depicted on the body map alongside researchers' detailed field notes explaining what the map symbols represent (GASTALDO, MAGALHAES, CARRASCO & DAVY, 2012; SOLOMON, 2002). [26]

VAUGHAN, DEW, NGO, BLAYNEY and BOYDELL (2022) used body mapping with 29 women with disability, mental distress and/or refugee background to explore their experiences of stigma and discrimination (see also VAUGHAN et al., 2025). Due to 2021-2022 Covid19 pandemic restrictions, the body mapping process was adapted to be delivered via six online workshops consisting of two, three-hour sessions involving up to five women in each and using an online facilitation guide as described in VAUGHAN et al. (2022). The online delivery meant the women created their maps in their homes, taking their time to complete their maps before sending them to the research team. Individual online interviews were then conducted for each woman to describe her map and the experiences they reflected. Participants' body maps were exhibited in three art exhibitions and a catalogue containing a visual image of each map and accompanying participant description was created. Figure 2 is one of the body maps created by participant, Cass (a pseudonym). Cass placed the statement "society disables me more than my body does" prominently in the centre of her body. In her description Cass noted "Ultimately people with disability miss out on things not because we have a disability but because people and places aren't accessible or inclusive" (VAUGHAN et al., 2025, p.17). The drawing on Cass' map of an elevator which is "out of order" and the accompanying text "Out of order for you means taking the stairs...out of order for me means cancelling date night AGAIN" vividly illustrated the impact of inaccessible environments. Alongside the depictions of exclusion, are powerful images (LGBTQA rainbow flag) and words indicating strength and resilience: "Being disabled is only one part of my identity", "I can and will climb mountains" and "Never underestimate my strength".

Figure 2: Cass' body map [27]

Second author Louisa SMITH and colleagues used body mapping with people with disability and complex support needs to facilitate the exploration of sensitive and controversial topics, including violence and abuse, neglect, trauma and gender and sexuality. In the "Lost in Transition" study (SMITH & DOWSE, 2019), which focused on transitions of young people with complex support needs, including disability, participants were asked to choose a significant life transition to body map. Rather than the more directive nature of text-based questions, this choice allowed young people to choose what and how they disclosed themselves. For example, one transgender woman re-made her body on the body map so that she could look the way she wanted to (COLLINGS & SMITH, 2021). In addition, the visual medium provided participants with ways of communicating their experiences which did not follow the linear patterns of verbal communication. For example, one participant used layer upon layer of paint, to show the way that abuse was compounded in her life but remained invisible to others (SMITH & DOWSE, 2019). SMITH and SENIOR (2021) noted that because body mapping is multimodal, the significance of the images for the participant is often only clarified after long periods of intense art making with the body mapping process itself becoming an important way of making sense of an experience. In a similar way, the body maps are large real objects which come to "stand-in" for a participant's relationships with the world. For example, one participant painted her cat's paws and got her cat to walk all over her body map to demonstrate the importance of her cat's intimacy. Another participant wanted to leave dirty footprints and mess on the map because "that's like life", and another took the map outside and drove over it with the car, to show their exhaustion. [28]

5.3 Community mapping (visual method)

Working collaboratively, Aboriginal researcher Elizabeth MCENTYRE and non-Indigenous researchers Priya VAUGHAN and Angela DEW, adapted individual body mapping to create community maps with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples with intellectual disability and family members. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures are collectivist rather than individualistic with family, community, and place central to people's lives. As noted previously, the use of arts-based research methods with Indigenous community members builds upon centuries of capturing and transferring knowledge via art-making (CLARK, 2022) and is recognised as a decolonising approach which empowers Indigenous people to describe their experiences in culturally validating ways (MANNING BANCROFT, 2023). The community-led adaptation of the method provided an appropriate and acceptable alternative group-based activity to generate research data (DEW et al., 2019a; DEW, VAUGHAN, McENTYRE & DOWSE, 2019b). We worked within local Aboriginal communities in five geographic locations in metropolitan, rural and remote areas of NSW Australia involving 26 Aboriginal participants. Participants created community maps related to their experiences of planning for disability supports and services. Participants worked collectively to draw, use collage and text to represent their geographic and cultural perspectives and the resources, supports and services available or lacking within their communities. The completed maps depicted "a visual representation of each community's identity, traditions, connections and sense of place related to being an Aboriginal person with disability" (DEW et al., 2019b, p.6). The community maps and notes from the associated group discussions were used by the researchers and participants to co-create a planning guide for use by Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal organisations to support Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island peoples with disability to make future support plans. An example of a visual from one of the rural community maps is included as Figure 3. The map depicts the coastal location and the importance of animals, fish and landscape to the community. It illustrates the range of people (e.g. the figure showing the attributes of an ideal support person and the tree showing "Our mob") and places (e.g. natural features such as rivers, and institutions such as the training centre) important to people with disability and family members from this community. The map highlights the importance of decolonising methods based on cultural responsiveness and safety in working with Indigenous people for example, understanding the impact of the colonial past on present day interactions indicated in the script "Understanding our past will help us build our future".

Figure 3: Aboriginal community map [29]

5.4 Found objects and crafting (3D artefacts)

Louisa SMITH and colleagues developed other sensory and multimodal methods with people living with dementia who do not use speech to communicate (SMITH & PHILLIPSON, 2021; SMITH et al., 2025). Working in a secure dementia facility, SMITH and colleagues co-developed personalised scarfs and blankets with people living with dementia, their care partners and care staff. After a month-long period of focused ethnography, which included detailed place based and participant observation and interaction, photographs, and interviews, SMITH and colleagues introduced a curated set of found objects which they thought might appeal to each person with dementia. These objects included fabrics, scented pouches, craft activities, toys, laminated images, and games. Through observing how people living with dementia interacted with and connected around each object, the researchers developed a collection of personalised objects. These objects were made into a scarf or blanket for each person living with dementia (see Figure 4). During the processes of developing, making and finally using the objects, SMITH and colleagues not only learnt about the participants living with dementia but also fostered new ways for them to connect to themselves, staff, family and one another (SMITH et al., 2023).

Figure 4: Example of a personalised blanket [30]

5.5 Photovoice (visual method)

Diane MACDONALD, in a PhD study supervised by BOYDELL, DEW and FISHER, used the visual arts-based method of photovoice with five women with physical disability to describe their experiences of stigma, discrimination and empowerment. One of the most well-established arts-based research methods, photovoice, involves participants taking photos of people, places or events related to the research topic (WANG & BURRIS, 1997). As a professional photographer, MACDONALD used her extensive photographic knowledge and skills to guide the women as emerging artists and co-researchers. The project demonstrated the ways in which arts-based methods can shift the power imbalance inherent in traditional research methods (DE SMET et al., 2024; MACDONALD, DEW, FISHER & BOYDELL, 2021a). The women chose to be identified in their photographs, used their real names, led presentations and exhibitions of their photos, and co-authored publications (MACDONALD, PEACOCK, DEW, FISHER & BOYDELL, 2022a; MACDONALD, VAN GIJN-GROSVENOR, MONTGOMERY, DEW & BOYDELL, 2021b). MACDONALD's work was also an example of the knowledge translation capacity of arts-based methods. Despite the impact of Covid19 pandemic restrictions, MCDONALD and the women hosted an in-person photographic exhibition and ran an online webinar. MACDONALD sought feedback from exhibition attendees about the impact of the photographs on their view of women with disability (MACDONALD, DEW, FISHER & BOYDELL, 2022b) revealing the powerful and transformative effect of arts-based methods. As described by one exhibition attendee, the photos acted to "Challenge my concept of beauty — realised that people with disability are people we tend to look away from and have difficulty treating as normal" (MACDONALD et al., 2022b, p.1024). Figure 5 is an example from co-researcher Melanie MONTGOMERY, of one of her photographs with explanatory script.

|

|

|

I like to think I'm as much of a storyteller as I am a photographer. Photography has been my passion since I was quite young, though I'm usually the one behind the lens, rarely in front. When you think of photographs of people with disability the images that come to mind are ones that evoke pity or sadness. Rarely do we see such images showcasing their power and strength as well as their vulnerability. It took a long time for me to work up the courage to take such photos and share them with the world. But in doing so I hope it sparks some passion and desire for more people with disabilities to do the same. This was my first week in the project and I eased myself into taking my self-portrait. So much so, I started off using a macro lens on one eye and slowly zoomed out. Eventually, I grew more courageous and zoomed out entirely, but this photo in particular always made me feel different somehow, vulnerable even. It pushed me on how I view myself against what others see, while also reminding me I'm different. And that's ok. |

Figure 5: Melanie's photo and description [31]

We have described and provided examples of using arts-based research methods with people with disability. As discussed, arts-based methods are increasingly recognised for the value they can add in explaining the subjective and embodied experience of research participants, facilitating choice and control as well as different modes of communication. We recognise and appreciate the power of arts-based research methods and the depth they add to our understanding of the people and topics we engage with in our research. As the case studies in this paper illustrate, introducing arts-based methods with people with disability facilitates greater levels of participation from research participants in how they represent their lives and themselves. [32]

While we are strong advocates for using arts-based methods, our use of them has involved challenges. As described in Section 4, these challenges included the logistics of assembling, transporting and storing life-sized body maps with collage and objects attached (DEW et al., 2021). Given that our research was conducted across multiple metropolitan, rural and remote locations this was often logistically difficult to arrange. To address this issue with body maps, DEW and colleagues changed the material onto which the maps were drawn from large fragile sheets of arts-paper to calico fabric which was more durable and could be folded for transportation and storage (VAUGHAN et al., 2022). We also instigated photographing the body maps in situ and leaving or returning the original maps to participants. We first did this at the behest of the Aboriginal community mapping participants who expressed a desire to keep their map so it could be added to by other members of the community (DEW et al., 2019a). SMITH and colleagues similarly photographed and left the curated set of found objects with the person with dementia as an ongoing memory aide for the participants, their family, and those working with them in residential aged care (SMITH et al., 2023). [33]

Earlier in Section 4, we described some of the analysis challenges we encountered to ensure that the important research data represented on the visual artefacts (body maps, photos and found objects) were accounted for in the analysis along with, rather than alongside, the textual data from testimonia and interviews (COLLINGS et al., 2021b). We believe more needs to be done to further develop arts-based analysis methods so that the richness, depth and often emotional complexities encapsulated in arts-data is not obscured and is fully appreciated. [34]

We have also encountered a number of ethical challenges which illustrate both the procedural challenges of obtaining ethics committee approval for arts-based research, and the practical application of ethics within our studies. We found that university ethics review committees can question the validity and rigour of arts-based methods and especially so when the research involves marginalised groups such as people with disability, ageing people, and those from Indigenous communities. Over the years and at different universities we have taken it upon ourselves to educate ethics committees about the value and robustness of arts-based methods especially when using them with people with disability who, as previously stated, may not communicate using verbal language. We have found a shift in understanding of the committees such that more recent ethics applications for using arts-based research progress more smoothly through the review system. Arts-based disability researchers can aid this education process by publishing about the methods they have used and describing ethical challenges they have encountered and overcome. We have also encountered push back from ethics committees and research funding bodies about using arts-based methods with people with cognitive impairments such as those with intellectual disability or those with dementia. As described by SANTINELE MARTINO and FUDGE SCHORMANS (2018), this concern centres on people's ability to consent to and actively engage in the arts-based research. SANTINELE MARTINO and FUDGE SCHORMANS and our research show that arts-based methods enhance rather than inhibit participation of these cohorts given the participatory and inclusive nature of art. [35]

As emerging research methods, especially within disability research, further work is required to ensure researchers describe their rationale for using arts-based methods to address their research questions and aims (FRASER & AL SAYAH, 2011), apply robust analytical methods to account for all forms of data (COLLINGS et al., 2021b), and attend to the inherent ethical issues (BOYDELL et al., 2012b; SANTINELE MARTINO & FUDGE SCHORMANS, 2018). [36]

We acknowledge and thank participants who took part in the various research projects described in this article. We also acknowledge the work of colleagues in arts-based research who have guided and influenced our work. We pay our respects to the traditional custodians of the lands on which we work, the Wurundjeri and Dharawal people and acknowledge that sovereignty of these lands was never ceded.

Bagnoli, Anna (2009). Beyond the standard interview: The use of graphic elicitation and arts-based methods. Qualitative Research, 9(5), 547-570.

Bagnoli, Anna & Clark, Andrew (2010). Focus groups with young people: A participatory approach to research planning. Journal of Youth Studies, 13(1), 101-119.

Boydell, Katherine M (Ed.) (2021). Appling body mapping in research: An arts-based method. Abingdon: Routledge.

Boydell, Katherine M; Gladstone, Brenda; Volpe, Tiziana; Allemang, Brooke & Stasiulis, Elaine (2012a). The production and dissemination of knowledge: A scoping review of arts-based health research. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 13(1), Art. 32, http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-13.1.1711 [Accessed: May 8, 2025].

Boydell, Katherine; Volpe, Tiziana; Cox, Susan; Katz, Arlene; Dow, R, Brunger, Fern; Parsons, Janet; Belliveau, George; Gladstone, Brenda; Zlotnik-Shaul, Randi; Cook, Sheila; Kamensek, Otto; Lafrenière, Darquise & Wong, Lisa (2012b). Ethical challenges in arts-based health research. International Journal in the Creative Arts in Interdisciplinary Practice,11, 1-17.

Braun, Virginia & Clarke, Victoria (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77-101.

Braun, Virginia & Clarke, Victoria (2013). Successful qualitative research: A practical guide for beginners. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Brown, Alison; Spencer, Rebecca; McIsaac, Jessie-Lee & Howard, Vivian (2020). Drawing out their stories: A scoping review of participatory visual research methods with newcomer children. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 19, 1-9, https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406920933394 [Accessed: May 8, 2025].

Burch, Leah (2022). "We shouldn't be told to shut up, we should be told we can speak out": Reflections on using arts-based methods to research disability hate crime. Qualitative Social Work, 21(2), 393-412, https://doi.org/10.1177/14733250211002888 [Accessed: May 8, 2025].

Burns, Siobhan & Waite, Mike (2019). Building resilience: A pilot study of an art therapy and mindfulness group in a community learning disability team. International Journal of Art Therapy, 24(2), 88-96.

Charmaz, Kathy (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative research. London: Sage.

Clark, Anna (2022). Making Australian history. Melbourne: Vintage Australia.

Coemans, Sara & Hannes, Karin (2017). Researchers under the spell of the arts: Two decades of using arts-based methods in community-based inquiry with vulnerable populations. Educational Research Review, 22, 34-49.

Collings, Susan & Smith, Louisa (2021). Representations of complex trauma: Body maps as a narrative mosaic. In Katherine Boydell (Ed.), Applying body mapping in research: An arts-based method (pp.27-36). Abingdon: Routledge.

Collings, Susan; Conley Wright, Amy & Spencer, Margaret (2021a). Telling visual stories of loss and hope: Body mapping with mothers about contact after child removal. Qualitative Research, 22(6), 877-896.

Collings, Susan; Dew, Angela; Curryer, Bernadette; Dillon Savage, Isabella & Tewson, Anna (2021b). Meaning-making and research rigour: Approaches to the synthesis of multiple data sources in body mapping. In Katherine Boydell (Ed.), Applying body mapping in research: An arts-based method (pp.57-66). Abingdon: Routledge.

Cox, Susan; Lafrenière, Darquise; Brett-MacLean, Pamela; Collie, Kate; Cooley, Nancy; Dunbrack, Janet & Frager, Gerri (2010). Tipping the iceberg? The state of arts and health in Canada. Arts & Health, 2(2), 109-124.

de Jager, Adele; Tewson, Anna; Ludlow, Bryn & Boydell, Katherine (2016). Embodied ways of storying the self: A systematic review of body-mapping. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 17(2), Art. 22, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-17.2.2526 [Accessed: January 14, 2025].

de Smet, Sofie; Spaas, Caroline; Smith Jervelund, Signe; Skovdal, Morten & De Haene, Lucia (2024). Reflections on arts-based research methods in refugee mental health: The role of creative exercises in nurturing positive coping with trauma and exile. Journal of Refugee Studies, 37(2), 336-355.

Dew, Angela (2019). Arts-based knowledge translation within disability research sphere. Invited keynote, Parenting Education Conference, 22-27th April 2019, Macau, China.

Dew, Angela; McEntyre, Elizabeth & Vaughan, Priya (2019a). Taking the research journey together: The insider and outsider experiences of Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal researchers. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 20(1), Art. 18, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-20.1.3156 [Accessed: May 8, 2025].

Dew, Angela; Smith, Louisa; Collings, Susan & Dillon Savage, Isabella (2018). Complexity embodied: Using body mapping to understand complex support needs. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 19(2), Art. 4, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-19.2.2929 [Accessed: May 8, 2025].

Dew, Angela; Tewson, Anna; Curryer, Bernadette & Dillon Savage, Isabella (2021). The logistics of making and preserving body maps as research data. In Katherine Boydell (Ed.), Applying body mapping in research: An arts-based method (pp.47-56). Abingdon: Routledge.

Dew, Angela; Vaughan, Priya; McEntyre, Elizabeth & Dowse, Leanne (2019b). "Our ways to planning": Preparing organisations to plan with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with disability. Australian Aboriginal Studies Journal, 2, 3-18, https://yumi-sabe.aiatsis.gov.au/sites/default/files/outputs/2024-02/agispt.20191217021677.pdf [Accessed: May 9, 2025].

Dew, Angela; Bulkeley, Kim; Veitch, Craig; Bundy, Anita; Gallego, Gisselle; Lincoln, Michelle; Brentnall, Jenny & Griffiths, Scott (2013). Addressing the barriers to accessing therapy services in rural and remote areas. Disability and Rehabilitation, 35(18), 1564-1570.

Edge, Christi U. & Olan, Elsie (2021). Learning to breathe again: Found poems and critical friendship as methodological tools in self-study of teaching practices. Studying Teacher Education, 17(2), 228-252.

Fraser, Kimberley Diane & al Sayah, Fatima (2011). Arts-based methods in health research: A systematic review of the literature. Arts & Health, 3(2), 110-145.

Gastaldo, Denise; Magalhaes, Lillian; Carrasco, Christine & Davy, Charity (2012). Body-map storytelling as research: Methodological considerations for telling the stories of undocumented workers through body mapping, http://www.migrationhealth.ca/undocumented-workers-ontario/body-mapping [Accessed: May 8, 2024].

Harasym, Jessica; Gross, Douglas; MacLeod, Andrea & Phelan, Shanon (2024). This is a look into my life: Enhancing qualitative inquiry into communication through arts-based research methods. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 23, 1-16, https://doi.org/10.1177/16094069241232603 [Accessed: May 9, 2025].

Kohler Riessman, Catherine (2005). Narrative analysis. In Nancy Kelly, Christine Horrocks, Kate Milnes, Brian Roberts & David Robinson (Eds.), Narrative, memory & everyday life (pp.1-7). Huddersfield: University of Huddersfield.

Macdonald, Diane; Dew, Angela; Fisher, Karen & Boydell, Katherine (2022b). Self-portraits for social change: Audience response to a photovoice exhibition by women with disability. The Qualitative Report, 27(4), 1011-1039, https://nsuworks.nova.edu/tqr/vol27/iss4/8/ [Accessed: May 9, 2025].

Macdonald, Diane; Dew, Angela; Fisher, Karen & Boydell, Katherine (2021a). Claiming space: photovoice, identity, inclusion and the work of disability. Disability and Society, 38(1), 98-126.

Macdonald, Diane; Peacock, Karen; Dew, Angela; Fisher, Karen & Boydell, Katherine (2022a). Photovoice as a platform for empowerment of women with disability. Qualitative Research in Health, 2, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmqr.2022.100052 [Accessed: May 9, 2025].

Macdonald, Diane; van Gijn-Grosvenor, Evianne; Montgomery, Melinda; Dew, Angela & Boydell, Katherine (2021b). "Through my eyes": Feminist self-portraits of osteogenesis imperfecta as arts-based knowledge translation. Visual Studies, 37(4), 244-256.

Manning Bancroft, Jack (2023). Hoodie economics: Changing our systems to value what matters. Melbourne: Hardie Grant Publishing.

Miller, Evonne (2025). The Black Saturday bushfire disaster: Found poetry for arts-based knowledge translation in disaster risk and climate change communication. Art & Health, 17(1), 8-23.

Mittner, Lilli & Gürgens Gjærum, Rikke (2022). Research innovation: Advancing arts-based research methods to make sense of micro-moments framed by dementia. Nordic Journal of Art and Research, 11(1), https://doi.org/10.7577/information.5065 [Accessed: May 9, 2025].

Moreira, Ana & Jakobi, Antonia (2021). Re-voicing the unheard: Meta-study on arts-based interventions for social inclusion of refugees and asylum-seekers. Journal of Education, Culture and Society, 2, 93-112, https://doi.org/10.15503/jecs2021.2.93.112 [Accessed: May 9, 2025].

Nathan, Sally; Hodgins, Michael; Wirth, Jonathon; Ramirez, Jacqueline; Walker, Natasha & Cullen, Patricia (2023). The use of arts‐based methodologies and methods with young people with complex psychosocial needs: A systematic narrative review. Health Expectations, 26, 795-805, https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.13705 [Accessed: May 9, 2025].

Orchard, Treena (2017). Remembering the body: Ethical issues in body mapping research. Cham: Springer.

Overmars-Marx, Tessa; Thomese, Fleur & Moonen, Xavier (2018). Photovoice in research involving people with intellectual disabilities: A guided photovoice approach as an alternative. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disability, 31, e92-e104.

Rich, Rebecca (2024). Found poetry, found hope: A creative and powerful method for sharing health research. Journal of Poetry Therapy, 37(4), 267-276.

Rose, Gillian (2016). Visual methodologies: An introduction to the interpretation of visual materials (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Santinele Martino, Alan & Fudge Schormans, Ann (2018). When good intentions backfire: University research ethics review and the intimate lives of people labelled with intellectual disabilities. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 19(3), Art. 9, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-19.3.3090 [Accessed: January 14, 2025].

Smith, Louisa & Dowse, Leanne (2019). Times during transition for young people with complex support needs: Entangled critical moments, static liminal periods and contingent meaning making times. Journal of Youth Studies, 22(10), 1327-1344.

Smith, Louisa & Phillipson, Lyn (2021). Thinking through participatory action research with people with late-stage dementia: Research note on mistakes, creative methods and partnerships. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 24(6), 775-780.

Smith, Louisa & Senior, Kate (2021). Mapping conversations: Body maps as relational objects in groups and dialogues. In Katherine Boydell (Ed.), Applying body mapping in research: An arts-based method (pp.18-26). Abingdon: Routledge.

Smith, Louisa; Phillipson, Lyn & Knight, Pat (2023). Re-imagining care transitions for people with dementia and complex support needs in residential aged care: Using co-designed sensory objects and a focused ethnography to recognise micro transitions. Ageing and Society, 43(1), 1-23.

Smith, Louisa; Carr, Chantel; Chesher, Isabelle & Phillipson, Lyn (2025). The meaning of home when you don't live there anymore: Using body mapping with people with dementia in care homes. Ageing & Society, 45(2), 207-232.

Solomon, Jane (2002). "Living with X": A body mapping journey in time of HIV and AIDS. Facilitator's guide. Johannesburg: REPSSI.

Van der Vaart, Gwenda; Van Hoven, Bettoma & Huigen, Paulus, P.P (2018). Creative and arts-based research methods in academic research. Lessons from a participatory research project in the Netherlands. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 19(2), Art. 19, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-19.2.2961 [Accessed: January 14, 2025].

Vaughan, Priya; Dew, Angela; Ngo, Akii; Blayney, Alise & Boydell, Katherine (2022). Exploring embodied experience via videoconferencing: A method for body mapping online. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 21(2), https://doi.org/10.1177/16094069221145848 [Accessed: May 9, 2025].

Vaughan, Priya; Boydell, Katherine; Blayney, Alise; Hooper, Ainslee; Taylor, Sue; Lenette, Caroline; Lappin, Julia & Dew, Angela (2025). “We are mirrored in your gaze”: Experiences and outcomes of stigma and discrimination for women with disability and mental distress. Disability & Society, https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2025.2470727 [Accessed: May 9, 2025].

Walmsley, Heather; Cox, Susan & Leggo, Carl (2017). Reproductive tourism: A poetic inquiry. Cogent Arts & Humanities, 4(1), https://doi.org/10.1080/23311983.2017.1371101 [Accessed: January 14, 2025].

Wang, Caroline & Burris, Mary Ann (1997). Photovoice: Concept, methodology, and use for participatory needs assessment. Health Education & Behavior, 24(3), 369-387.

Wang, Qingchun; Coemans, Sara; Siegesmund, Richard & Hannes, Karin (2017). Arts-based methods in socially engaged research practice: A classification framework". Art/Research International: A Transdisciplinary Journal, 2(2), 5-39, https://journals.library.ualberta.ca/ari/index.php/ari/article/view/27370/21374 [Accessed: May 9, 2025].

Wiggins, Jackie (2011). Feeling it is how I understand it: Found poetry as analysis. International Journal of Education & the Arts, 12(LAI 3), http://www.ijea.org/v12lai3/ [Accessed: May 9, 2025].

Yunkaporta, Tyson (2023). Right story, wrong story: Adventures in Indigenous thinking. Melbourne: Text Publishing.

Angela DEW (she/her), PhD, is professor of disability and inclusion at Deakin University, Melbourne where she is engaged in research and teaching related to people with disability and complex support needs. Angela is a sociologist with over 40 years' experience in the Australian disability sector. In her research, she seeks to understand the specific issues faced by people with disability and a range of complexities including living in rural and remote locations and coming from an Aboriginal or refugee background. Angela uses qualitative and arts-based methods within an integrated knowledge translation framework to ensure her research results in practical solutions that can be tailored to individuals and local communities.

Contact:

Angela Dew

Deakin University, Burwood Campus

221 Burwood Highway, Burwood Victoria 3125, Australia

E-mail: angela.dew@deakin.edu.au

URL: https://www.deakin.edu.au/

Louisa SMITH (she/her), PhD is a senior lecturer in disability and inclusion at Deakin University, Melbourne. She specializes in qualitative social research on disability, dementia, and complex support needs, focusing on socially isolated groups, including LGBTQ+ individuals and refugees. Her work spans sociology, disability, dementia, and policy studies, emphasizing inclusive and participatory methodologies. Currently, she leads participatory action research to co-develop resources for people with disabilities and dementia. Over the past five years, Louisa has secured over $2.5 million in grants, including a Medical Research Futures Fund grant for LGBTQ+ dementia care models.

Contact:

Louisa Smith

Deakin University, Burwood Campus

221 Burwood Highway, Burwood Victoria 3125, Australia

E-mail: louisa.smith@deakin.edu.au

URL: https://www.deakin.edu.au/

Dew, Angela & Smith, Louisa (2025). Using arts-based methods in disability research [36 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 26(2), Art. 26, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-26.2.4354.