Volume 26, No. 3, Art. 17 – September 2025

Bridging Qualitative Reconstructive Typologies and Quantitative Measurement: A Reflective Approach to Methodologically Sound Item Development for the Assessment of Teachers' Epistemological Beliefs in Teaching Humanities Subjects

Jana Costa & Caroline Rau

Abstract: With this manuscript, we make a methodological contribution to mixed methods research by exploring the systematic development of quantitative measurement instruments from qualitatively reconstructed typologies, using the example of teachers' epistemological beliefs in teaching humanities subjects. The qualitative, verbal database for these considerations consists of group discussions that were analyzed using the documentary method in order to create a typology.

We address the systematic and methodologically sensitive translation of qualitative typologies into quantitative measurement instruments. Through in-depth methodological reflection, we explore how the methodological principles of the documentary method are used to inform the development of survey items. We highlight the challenges of reconciling the implicit, practice-oriented nature of qualitative-reconstructive insights with the explicit, operationalized demands of quantitative frameworks, and repeatedly relate these considerations to a qualitative typology of teachers' epistemological beliefs in teaching humanities subjects. The proposed approach allows for iterative integration, offering a pathway to bridge these methodological divides. With this research, we contribute to advancing the integration of mixed methods by demonstrating how qualitatively derived typologies can inform robust quantitative analyses.

Key words: methodological reflection; documentary method; implicit knowledge; qualitative-reconstructive research; item development; epistemological beliefs; typology

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. Integrating Qualitative-Reconstructive and Quantitative Research Approaches

2.1 Objectives of integration

2.2 Integration strategy

2.3 Prerequisite for integration: Systematic reflection on methodological foundations

3. Documentary Method

4. Methodological Foundation of Item Development Based on a Qualitatively Reconstructed Typology

4.1 Developing typologies with the documentary method: Insights from a study on the epistemological beliefs of humanities teachers

4.2 From qualitatively reconstructed typologies to measurement instruments: Methodological foundations of item development

4.3 Consolidation of the ideal types

5. Discussion

In this article, we examine the methodological foundations of developing items derived from qualitatively reconstructed typologies. Central to this topic is the task of identifying the guiding methodological principles when translating these typologies into numerical data for subsequent quantitative analyses (SANDELOWSKI, VOILS & KNAFL, 2009). [1]

Extending qualitative-reconstructive research involves specific objectives, such as the generalization of findings based on representative samples and the systematic testing of correlational and causal relationships suggested by the qualitative data. Within a circular research process, quantification is viewed as a means of achieving a more comprehensive understanding of complex phenomena (e.g., JOHNSON & ONWUEGBUZIE, 2004), facilitating the systematic advancement of existing theoretical frameworks. Moreover, the findings generated through this approach can inform and open new perspectives for subsequent analyses. [2]

The quantification of qualitative data and findings has been extensively explored within mixed methods research, particularly in the development of sequential phase designs (e.g., CRESWELL & PLANO CLARK, 2011) and discussions about integration strategies (ÅKERBLAD, SEPPÄNEN-JÄRVELÄ & HAAPAKOSKI, 2021; BAZELEY, 2024; BRYMAN, 2006). In particular, content analysis methods provide a nuanced framework for examining the interplay between qualitative and quantitative approaches (e.g., DeJONCKHEERE, VAUGHN, JAMES & SCHONDELMEYER, 2024). Researchers often report on the quantification of qualitative findings, for example, when preliminary qualitative studies are conducted to inform subsequent quantitative surveys (LANGFELDT & GOLTZ, 2017). [3]

Despite significant efforts to establish strong methodological and theoretical foundations (ZHOU & WU, 2022) and to conceptualize integrative approaches within mixed methods discourses (BAZELEY, 2024), few researchers have explicitly examined the systematic integration of qualitative reconstructive typologies into numerical data for further analysis (BORGSTEDE & RAU, 2023; COSTA & TAUBE, 2024). This is surprising given the extensive body of research rooted in the qualitative-reconstructive paradigm (BOHNSACK, 2010; HINZKE, GEVORGYAN & MATTHES, 2023), including numerous studies employing the documentary method (e.g., SCHEUNPFLUG, KROGULL & FRANZ, 2016; TAUBE, 2024; TIMM, KAUKKO & SCHEUNPFLUG, 2023). The development of quantitative measurement instruments based on qualitatively reconstructed typologies generated using the documentary method remains an underexplored area of research and has not yet been systematically addressed. Consequently, these rich typologies often remain confined to the qualitative discourse and are not systematically leveraged for further studies or quantitative analyses. [4]

We seek to address this issue by exploring the systematic development of items derived from a qualitatively reconstructed typology using the documentary method. This approach is grounded in the notion that thorough reflection on the methodological and epistemological foundations, the documentary method can offer new perspectives for item development and subsequent quantitative analyses. Such reflection is also crucial for recognizing the specificities of qualitative-reconstructive research within a quantitative framework and for generating insights to guide the integration process. [5]

We begin by examining the process of integration, linking the proposed foundational ideas to the existing mixed methods discourses. We argue that a simple classification into "qualitative" and "quantitative" categories is insufficient. Instead, we propose that the methodological and epistemological specificities of the documentary method, along with the typologies it generates, must be systematically considered when developing items (Section 2). In Section 3 we introduce the core principles of the documentary method, providing the theoretical groundwork for understanding the approach. Next, we demonstrate how typologies are generated using the documentary method, drawing on a study on the "Epistemological Beliefs of Teachers in the Humanities Domain" (RAU, 2021). This typology serves as a suitable example for methodological reflection on item development. We focus on the systematic analysis of two central questions: What role do the methodological and epistemological foundations of the documentary method, including its claim to generalization through typologies, play in item development? What implications and challenges emerge when differing epistemological logics—qualitative-reconstructive and quantitative approaches—are integrated (Section 4)? Finally, we will summarize and discuss the findings (Section 5). [6]

2. Integrating Qualitative-Reconstructive and Quantitative Research Approaches

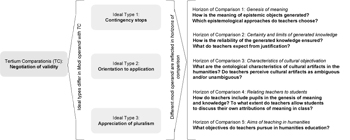

In this section, we situate the development of a measurement instrument based on a qualitatively reconstructed typology within mixed methods discourses. First, we outline the project's objectives (Section 2.1), then we detail the integration strategy (Section 2.2), and finally, we emphasize the need for deeper engagement with methodological foundations in item development (Section 2.3). [7]

The goal of the outlined approach is to develop a quantitative measurement instrument grounded in a qualitatively reconstructed typology. From our perspective, adopting a quantitative approach is beneficial because it allows an evaluation of the relational structural features of the typology using larger and, more importantly, representative samples. Our emphasis is not on replicating or verifying the qualitatively reconstructed typology; rather, we see the quantification process as contributing to systematic theory development, enabling the exploration of the typology's broader applicability through quantitative methods (BORGSTEDE & SCHOLZ, 2021). [8]

Quantitative approaches can provide deeper insights into the genesis, dependencies, and contextual embedding of typologies already suggested by qualitative data, thereby supporting the development of theoretical models. For instance, correlational patterns can be identified, modeled, and examined in their width through subsequent analyses. However, we do not consider the quantitative approach to be the definitive or sole pathway. Instead, we regard it as a step within a broader research process aimed at advancing the study of complex phenomena while systematically building on existing findings. [9]

A quantitative perspective also facilitates the analysis of effects across multiple levels and their interrelations. For example, interactions between teachers' practices and students' outcomes can be examined, allowing theoretical models to be systematically enriched and expanded to incorporate additional dimensions. [10]

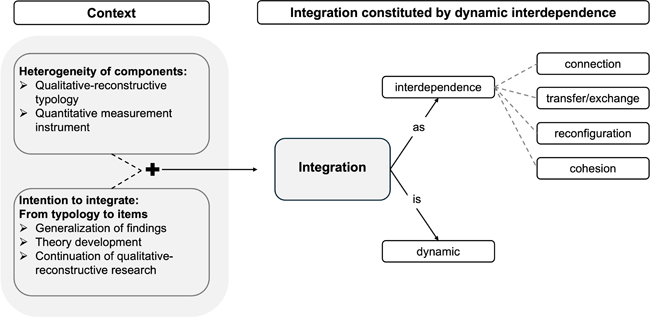

In this section, we discuss the importance of a thorough examination of the methodological specifics of the underlying typology. We argue that such engagement is essential for the advancement of qualitatively reconstructed typologies. Deep reflection on methodological foundations can foster a more integrated combination of qualitative and quantitative components. Integration has been described as being "at the heart of the mixed methods enterprise" (FIELDING 2012, p.126), highlighting the importance of articulating a clear integration strategy. We apply the constitutive dimensions of integration described by BAZELEY (2024) to this project to clarify our underlying perspective. Figure 1 illustrates how the integration process unfolds through the dynamic interplay of context, research intention, and methodological components.

Figure 1: Integration process (adapted from BAZELEY, 2024) [11]

BAZELEY described integration as a dynamic process in which individual components (in our case, the qualitatively reconstructed typology and the quantitative measurement instrument) become interdependent. This interdependence is characterized by the components being interconnected and utilized to create a new cohesive entity. In this project, the qualitatively reconstructed typology is not regarded as a conclusive result that can be directly converted into the quantitative domain. Instead, it involves a dynamic process where reflection on the methodological foundations fosters interdependence between the various components. As illustrated in Figure 1, this integration process is shaped by the contextual conditions of the study—namely, the heterogeneity of the components and the underlying intention to integrate. The constitutive elements and dimensions of the qualitative typology thus serve as the foundation for item development, guiding both the specific focus areas and the analytical methods employed within the quantitative framework. [12]

This process necessitates "communication between the parties involved" (p.229), allowing for the identification and acknowledgment of discrepancies. Accordingly, integration is not conceived as a linear transfer between methodological paradigms, but rather as a dynamic process of translation—understood as an interpretive and transformative interplay characterized by exchange, reconfiguration, and the development of cohesion between components (see Figure 1). [13]

We conceptualize item development as an intermediary step that facilitates the joint consideration of the individual components or findings within the broader research process. It creates a space for exploring convergences and dissonances between findings. Consequently, in an iterative process, divergent, paradoxical, or contradictory findings can serve as a basis for a deeper analysis, contributing to the further refinement of the qualitatively reconstructed typology and, in turn, advancing theory development. In the following analysis, we discuss the prerequisite for integration by systematically reflecting on the methodological foundations. [14]

2.3 Prerequisite for integration: Systematic reflection on methodological foundations

Recent debates within the context of mixed methods approaches demonstrate a growing awareness of methodological and epistemological challenges, along with their implications for the research process (e.g., ÅKERBLAD et al., 2021; COATES, 2021; ZHOU & WU, 2022). This has led to calls for a clearer focus on addressing methodological challenges in future research and for fostering open dialogue within the academic community (ZHOU & WU, 2022). Here, we address this call by examining the challenges involved in developing items based on existing qualitatively reconstructed typologies. These challenges become especially significant when a qualitative study is framed as an independent endeavor with a unique methodological perspective. We argue that integrating methodological reflection on qualitative methodology with the development of a quantitative measurement instrument is a prerequisite and a valuable opportunity for deeper integration. This process, however, requires a thorough understanding of the distinct methodological logics and an exploration of strategies to effectively bridge them. In doing so, we also respond to calls to systematically build on existing data within the context of mixed methods research (SCHOONENBOOM, 2023; WATKINS, 2023; WATKINS & JOHNSON, 2023). We propose extending the scope of traditional secondary data analyses to include the systematic further development of findings from existing studies. [15]

We emphasize that systematically reflecting on how qualitative findings can inform quantitative research requires careful consideration of the specific methodological assumptions and analytical steps inherent to each method. Moving beyond longstanding debates on the epistemological differences between qualitative and quantitative research, a focus on the specific evaluation and analysis procedures allows methodological connections to be identified. Based on this, the measurement instrument can be developed, while systematically addressing related challenges. In the following section, we introduce a specific analytical approach that serves as the foundation for the measurement instrument: The documentary method and the qualitatively reconstructed typology generated use the documentary method. [16]

Rooted in the qualitative-reconstructive research paradigm, the underlying principle of the documentary method is the distinction between explicit and implicit knowledge, with a particular focus on uncovering the latter (BOHNSACK, PFAFF & WELLER, 2010a; MANNHEIM, 1936 [1929], 1982 [1980]). Originally developed in Germany, the documentary method has been the subject of ongoing discussion and refinement within the German-speaking scientific community. In recent years, it has also gained increasing recognition and application in English-speaking contexts, particularly in research conducted on and within schools (HINZKE et al., 2023; SCHEUNPFLUG et al., 2016). [17]

While explicit knowledge can be directly articulated, implicit knowledge (BOURDIEU, 1977 [1972]; POLANYI, 1966) operates beneath the surface, shaping actions and decisions through ingrained values and practices (MANNHEIM 1936 [1929], 1982 [1980]). The documentary method is used to move beyond analyzing the content of what participants say and do to examine how their verbalizations and actions reflect underlying practices and implicit orientations. Within the discourse on the documentary method, scholars emphasize that a methodological premise is that individuals' verbal statements may align with, contradict, or diverge from their actions. For instance, teachers might say that fostering democratic values in students is important to them, yet their manner of speaking may reveal an authoritarian teaching style which is inconsistent with these values. [18]

The core principle of the documentary method is to uncover the discrepancy between the propositional and the performative logic by reconstructing the way in which people discuss a specific topic. The ways in which individuals engage with the same subject—or their practices—are referred to as Orientierungsrahmen [frameworks of orientation] (BOHNSACK, 2010, 2017). These frameworks of orientation can be generalized into typologies through comparative, abstracting and abductive procedures (PEIRCE, 1998; SCHURZ, 2008). Such typologies are constructed based on both intra-case and inter-case comparisons. [19]

In the context of this approach, scholars highlight the exploration of conjunctive experiences (BOHNSACK, 2017; BOHNSACK et al., 2010a; MANNHEIM, 1936 [1929], 1982 [1980])—shared experiences within communities or among individuals with similar social backgrounds and activities. These experiences are described as fostering implicit knowledge, which is expressed through collective practices and interactional patterns. To access this knowledge, group discussions are frequently employed, as they provide a dynamic setting where shared orientations and values become visible (BOHNSACK, 2010). [20]

The analytical focus of the documentary method goes beyond interpreting the explicit content (e.g., of discussions) to examine the importance that participants attach to certain topics and the underlying knowledge that shape these priorities. This methodological shift—from studying what is discussed and done to examining the how—enables a deeper understanding of the orientations of the research participants. In the following section, we outline the methodological foundation for item development based on a qualitatively reconstructed typology. [21]

4. Methodological Foundation of Item Development Based on a Qualitatively Reconstructed Typology

Qualitative and quantitative approaches are rooted in distinct epistemological logics that shape both the design of research and the interpretability of findings. These different logics come together in the process of item development. This intersection creates tensions that must be resolved in order to effectively guide item construction. The critical-reflective approach outlined in this article helps pinpoint where translation work between the different logics is necessary and where auxiliary constructs need to be developed. With this approach we highlight the importance of recognizing the different levels within the research process and their inherent logics, while continually reflecting on how they shape the concrete development of items. [22]

In this section, we introduce the typology that serves as a basis for translating abstract methodological approaches into concrete applications (Section 4.1). We then examine the methodological foundations of item development, first in the abstract and then using a concrete example from the underlying study (Section 4.2). [23]

4.1 Developing typologies with the documentary method: Insights from a study on the epistemological beliefs of humanities teachers

RAU (2020) examined the "Epistemological beliefs of humanities teachers" by developing a typology from 19 group discussions with a total of 78 teachers. To provide a foundation for the abstract methodological considerations discussed in the following section, the basic structure of the typology is outlined here. For a more comprehensive account of the study, see RAU (2020, 2021). [24]

In this article, we focus on the meaning-generative typology, which is one form of typology among others (BOHNSACK, 2010; BOHNSACK, PFAFF & WELLER, 2010b). The starting point of a meaning-generative typology is a theme that occurs across all cases and forms the core of all frameworks of orientation: The tertium comparationis (TC). The individual types within a typology reflect different ways of engaging with the TC. An individual type represents a theoretical abstraction or ideal type that transcends individual cases and integrates frameworks of orientation from various cases. Through a comparative analysis, researchers identify different comparison horizons (CH). Like the TC, researchers do not know these horizons a priori but reconstruct them through a comparative-iterative, abstracting and abductive process. The CH and the TC enable the differentiation of types that reflect distinct ways of engaging with the TC. CHs are essential for identifying the defining characteristics that differentiate one type from another (see BOHNSACK, 2010, for a detailed discussion). [25]

In this specific study, RAU (2020) reconstructed three ideal types based on teachers' narratives during group discussions. These types represent different modi operandi in dealing with validity which serve as the TC of the study. The three ideal types are distinguished by how validity is constructed and legitimized through their epistemological beliefs. The three ideal types can be distinctly characterized using five CH. The typology allows teachers' differing epistemological beliefs to be systematically captured and compared (see Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Structure of the qualitative-reconstructive typology. Please click here for an enlarged version of Figure 2. [26]

The first ideal type is defined by its reliance on interpretations rooted in a historically anchored understanding of the subject matter. This type reflects patterns in which the validity of knowledge and insights is considered stable as long as they are interpreted in historical context. A typical example is a teacher asking, "What was the author trying to convey with this poem?" In this case, the author's intent and the historical context are treated as essential benchmarks for interpreting the content of the poem. RAU described these types as dogma-oriented. Clearly, the existence of an objective truth or correct interpretation is validated by its alignment with the historical context. [27]

The second ideal type is characterized by a highly contextualized and subjective perspective on the validity of knowledge. The following patterns are included: Rather than being based primarily on its original historical context, the interpretation of educational content is centered on the context in which it is received—specifically, the individual meaning it holds for learners against the backdrop of their own lived experiences. A typical example is the question: "What does this poem offer me for my own life?" Here, the focus is placed on the personal relevance and subjective value of the content for the learner. [28]

The third ideal type is defined by a pluralistic and theoretically grounded approach to attributing validity to interpretations. This type is based on the principle that interpretations are validated within intersubjective communities of communication. This means that validity is not determined solely by individual interpretations or the original historical context, but is instead shaped by the discourses and negotiations within a community of interpreters. A typical example is the question: "How can this poem be interpreted when analyzed through a feminist theoretical lens?" Here, methodological diversity and the application of various theoretical frameworks take precedence, enabling a nuanced and reflective interpretation (RAU, 2020, 2021). [29]

4.2 From qualitatively reconstructed typologies to measurement instruments: Methodological foundations of item development

In the following section, we outline a three-step process to identify relevant aspects for developing items based on a qualitatively reconstructed typology. First, the foundational assumptions of the documentary method are presented. Next, their implications for item development are discussed, and finally these considerations are illustrated using the previously introduced typology. [30]

4.2.1 (Re-)Construction practices across layers of meaning

In qualitative-reconstructive research, the concept of construction is particularly significant in guiding the research process. Within the framework of the documentary method, this entails reconstructing the habitus (BOURDIEU, 1977 [1972]) and/or the framework of orientation—that is, the conjunctive experiential knowledge (MANNHEIM, 1936 [1929], 1982 [1980])—of the study participants. These reconstructions are then systematically consolidated into typologies by means of a methodologically controlled process. During the process of item development, researchers inevitably encounter various acts of construction and are required to reflexively engage with them. These constructive acts are performed (Section 4.2.1.1) by the study participants and (Section 4.2.1.2 and Section 4.2.1.3) by the researchers themselves. [31]

4.2.1.1 First-order constructions as constructions by the research participants

In specific data collection situations (in this case, group discussions with teachers), research participants provide insights into their practices and constructions of reality. These acts of construction by the participants become visible in verbalized form, as conversation partners articulate their bodies of knowledge and describe their self-image both explicitly and implicitly (BOHNSACK, 2010, 2017). [32]

In the present study, this can be illustrated using the example of the first ideal type, dogma-oriented contingency stop (see Section 4.1): During a group discussion, the teachers reflect on a theater visit for a performance of Franz KAFKA's "The Metamorphosis" (2025 [1915]). They criticize the production for failing to meet their expectations, and therefore deem it unsuitable for a school visit with students. Their critique is based on the claim that the director's interpretation diverged from the author's intentions, which they consider fundamental. They argue that this "incorrect" production should not be shown to students, who might, in turn, adopt allegedly incorrect interpretations of the work in their exams. [33]

This rejection stems from a discrepancy between the teachers' reading of the text which focuses on the author's intentions and the historical context, on the one hand, and the interpretive framework employed by the art director, on the other. While the teachers acknowledge the theoretical possibility of alternative readings, they do not accept them as valid interpretations of the work that align with the author's intent. One teacher underscores this position by stating that such a production could no longer be called "Kafka," thereby dismissing any interpretations not grounded in a historization-oriented approach as lacking scientific legitimacy within the humanities. [34]

4.2.1.2 Second-order constructions as (re-)constructions by researchers of constructions made by research participants

In the reconstructive research process, researchers draw on verbalized constructions of reality provided by research participants. The participants' narratives about their own practices, the contextualization of these practices, and the articulation of their relevance enable a methodologically grounded Fremdverstehen [understanding of the other]. The starting point for the researchers' reconstructive efforts is, therefore, the narratives of the participants concerning their constructions of reality (Section 4.2.1.1). According to POLANYI and his famous paradox "We can know more than we can tell," tacit and implicit knowledge is inherently difficult to articulate (1966, p.4), but it can be partially reconstructed or made explicit through careful processes of interpretation. Through the researchers' (re-)constructive efforts (Section 4.2.1.2), it becomes possible to access the participants' implicit bodies of knowledge or habitus (Section 4.2.1.1). Hence, the constructions made by the researchers are reconstructions of the constructions made by the participants (BOHNSACK, 2010; SCHÜTZ, 1971). [35]

The analysis of the aforementioned group discussion, conducted using the documentary method, revealed that the teachers adopt a distinctive approach to engaging with the meanings of cultural objectifications (CH 1)—in this case, KAFKA's "The Metamorphosis" (2025 [1915]). Based on second-order constructions by the researchers (Section 4.2.1.2), the teachers' practices and habitus can be described as follows: They generate knowledge through a historizing and mono-perspectival epistemological approach. In this process, a dogma-oriented epistemological monopoly becomes the guiding principle for their actions, as alternative interpretations or attributions of meaning are neither addressed nor discussed. [36]

4.2.1.3 Implications for item development

In the process of translating such typologies into items, researchers are consistently confronted with acts of construction across different levels. Item development itself can be understood as an additional act of construction by the researchers, which draws on the first-order constructions by the research participants (Section 4.2.1.1) as well as on the existing (re-)constructions by the researchers, or second-order constructions (Section 4.2.1.2). Consequently, we describe the advanced constructive effort associated with item development as third-order constructions by the researchers (Section 4.1.2.3). [37]

To develop clear and concrete items (Section 4.1.2.3) that connect to the lifeworld of the participants and are understood uniformly by all, it is essential to address the participants' concrete verbalized knowledge and practices (Section 4.2.1.1) while simultaneously incorporating their relation to the reconstructed bodies of knowledge as constructed by the researchers (Section 4.2.1.2). [38]

With regard to the dogma-oriented contingency stop ideal type, the underlying field of tension is as follows: Items may be constructed to directly reference specific statements from the group discussion (Section 4.2.1.1) (e.g., "If a production of Kafka does not align with the original, I see it as my responsibility to clarify this" or "I consider it important to correct potential misinterpretations of literary works during theater visits"). Alternatively, they may be formulated to more abstractly reflect the fundamental characteristics of the ideal type (Section 4.2.1.2) (e.g., "Students should interpret music, literature, and art in the context of their historical origin"). [39]

Hence, researchers have to move reflexively between the different levels of construction throughout the item development process. The constructions of the participants can serve as sources of inspiration for developing concrete items, but they must always be considered in relation to the reconstructed bodies of knowledge and the (re-)constructive efforts of the researchers. [40]

4.2.2 Implicit vs. explicit knowledge

In the documentary method, the reconstruction of implicit bodies of knowledge and habitus play a central role (BOHNSACK, 2010, 2017). In group discussions, these bodies of knowledge—arising from shared experiences—are actualized. This knowledge is not explicitly articulated but is shared among participants and implicitly expressed in conversations. These implicit, conjunctively shared bodies of knowledge differ from communicative knowledge, which is explicitly articulated and linguistically expressed (POLANYI, 1966; MANNHEIM, 1936 [1929], 1982 [1980]). The distinction between communicative and conjunctive knowledge is fundamental to item development, as a sense-genetic typology draws upon conjunctive (rather than communicative) bodies of knowledge (BOHNSACK, 2010, 2017; MANNHEIM, 1936 [1929], 1982 [1980]). Consequently, any measurement instrument aiming to capture relevant aspects of a typology must also focus on assessing conjunctive knowledge. This highlights two fundamental challenges and implications for item development. [41]

4.2.2.1 How can conjunctive bodies of knowledge, which are not reflexively accessible to respondents, be represented by items and thus explicitly elicited?

To further explore this question, it is beneficial to focus on the relationship between what is explicitly articulated and what is implicitly expressed in specific practices or habitus. For item development, the distinction between communicatively and conjunctively shared bodies of knowledge allows the core epistemological focus of the measurement instrument to be refined. Because the typology-building process was focused on the performative level—namely, the conjunctively shared bodies of knowledge or habitus—the measurement instruments also need to capture these aspects to adequately represent the typology. [42]

An analysis of the dogma-oriented contingency stop ideal type, as an example, reveals that focusing on conjunctively shared bodies of knowledge or habitus requires moving beyond solely relying on self-assessments (e.g., "It is important to me to clarify misunderstandings about literary works like Kafka's"). Self-assessments, such as those measured on a scale from "strongly disagree" to "strongly agree," assume that these bodies of knowledge are reflexively accessible and can be explicitly articulated by respondents, shifting the focus to communicative knowledge. Focusing on the level of conjunctively shared bodies of knowledge, however, requires carefully developed correspondence rules. These rules enable researchers to gain insights by querying specific practices in which conjunctive knowledge is embedded (e.g., "I would talk about flawed productions of literary works in class after a theater visit"). [43]

Furthermore, scenario-based items can be designed to address specific action situations (e.g., "Imagine you take your class to a theater performance that distorts Kafka's works. How would you respond?" Example response options: "I would criticize the theater production and convey the correct interpretation to the students," "I would accept the production as an expression of artistic freedom and not address it further;" "I would use the theater visit as an opportunity to clarify general misunderstandings about Kafka's work," etc.). By constructing such items, the researchers allow for a stronger focus on conjunctively shared bodies of knowledge and the habitus. [44]

4.2.2.2 How can items be designed in a way that allows individuals to respond by making collectively shared bodies of knowledge visible? More specifically, how can the relation between an individual's orientation and collectively shared orientations described in a typology be captured?

With this question, we draw attention to the link between item development and the relationship between individual and reconstructed conjunctively shared bodies of knowledge. This relationship must be captured in an item's formulation in order to describe shared perspectives and subsequently identify a respondent's relation to them. This means that items must incorporate particularly salient features of collectively shared bodies of knowledge. This allows individuals to establish a relationship between the collectively shared bodies of knowledge described, on one hand, and their response behavior, on the other. [45]

To identify such salient features, comparative horizons can be utilized, as they reflect differences in the conjunctively shared bodies of knowledge. In the specific context of the study exemplified here, the comparative horizons are used to structure the items around central questions, with different response patterns expected depending on the ideal type. For instance, with regard to the question about how the meaning of objects of knowledge (e.g., poems) is generated, the dogma-oriented contingency stop ideal type could be captured through items with interpretations reflecting a historizing approach (e.g., "Alternative interpretations of a poem that deviate from its historical context inevitably lead to misinterpretations"). [46]

It can be argued in this context that to represent qualitative-reconstructive typologies within a geometric space, it is not necessary to operationalize a latent construct in the sense of classical causal-analytical test theory via item response models. Rather, it involves representing theoretical abstractions (BORGSTEDE & RAU, 2023). This implies that no causal relationship between the items and the abstract construct is assumed. Instead, a logical relation of concepts derived from the theoretical foundation or abstraction exists (e.g., BUNTINS, BUNTINS & EGGERT, 2016; LEISING & BORGSTEDE, 2019). [47]

4.3 Consolidation of the ideal types

The description of conjunctively shared bodies of knowledge, along with their consolidation and generalization (including abstracting and abductive reasoning processes), is central to the development of typologies. Through intra-case and inter-case comparisons of conjunctive knowledge, homologous patterns are first identified and subsequently abstracted and specified. [48]

In an intra-case analysis, researchers compare bodies of knowledge within a single case to capture detailed differences, whereas in an inter-case comparison, they relate bodies of knowledge across different cases to identify overarching similarities and differences. Through comparative analysis, along with targeted minimal and maximal contrastive approaches—selecting similar cases (minimal contrast) or highly divergent cases (maximal contrast)—the researchers identify a tertium comparationis, or a common theme across all cases, as the starting point for a typology. Moreover, applying these methods makes it possible to develop ideal types and, in turn, to refine the typology across its comparative dimensions. [49]

Qualitative-reconstructive typologies are thus based on ideal types that differ within shared comparative horizons. These ideal types do not represent the empirically observed reality. Instead, they are a form of scientific consolidation used to analyze empirical reality (BOHNSACK, 2010, 2017; BOHNSACK et al., 2010b). [50]

When developing items, it must therefore be considered that individuals' response behavior cannot definitively determine their affiliation with a single ideal type. Rather, response patterns point to the probability of an individual belonging to a particular type, with mixed forms always expected in reality. Specifically, this means that a teacher's response behavior cannot be unambiguously classified under the dogma-oriented contingency stop ideal type. To accommodate such mixed forms, response scales should not enforce binary exclusions (e.g., yes/no) but instead, represent a continuum, such as is the case for Likert scales. To determine the likelihood of a teacher being more aligned with one ideal type or another, responses across various dimensions have to be combined. [51]

In this article, we delve into the methodological foundations of developing items grounded in qualitatively reconstructed typologies, with a particular emphasis on the application of the documentary method. With this method, we seek to uncover implicit frameworks of orientation embedded in respondents' practices. We address the challenges of systematically translating qualitative findings into quantifiable measurement instruments and underscore the importance of implementing a thoughtful and reflective methodological approach. [52]

Deeper engagement with the documentary method's foundations reveals that a linear transmission of typologies into items is not feasible. Instead, developing items and selecting quantitative analytical methods involves finding a careful balance within following fields of tension in order to effectively represent qualitatively reconstructed typologies within a geometric space:

While the documentary method focuses on reconstructing implicit knowledge, quantitative designs rely on explicit questioning. The challenge lies in designing items that capture the performative aspects (the how) rather than merely addressing explicitly stated content. This means developing items that are positioned at the intersection of implicit orientations and explicit questioning (implicit vs. explicit).

Furthermore, a typology developed through the documentary method is based on theoretical abstractions, while quantitative items necessitate concrete operationalization. Therefore, in developing items, researchers must strike a balance between the abstract qualities of a typology and the specificity required for individual items (abstract vs. concrete). Establishing appropriate correspondence rules is therefore essential to bridge the gap between theoretical models and practical measurability.

Moreover, ideal types are abstract constructs that do not directly mirror empirical reality but instead distill frameworks of orientations (ideal types vs. real types). This implies that items in quantitative operationalization should not be designed to definitively classify respondents into a specific ideal type. Instead, probabilistic models can be employed to account for hybrid forms and measure respondents' proximity to particular types (BORGSTEDE & RAU, 2023).

Finally, the assumption of latent constructs in classical test theory is in tension with the theoretical abstractions of the documentary method (latent constructs vs. theoretical abstractions). Rather than postulating causal relationships between items and constructs, the focus should shift to emphasizing logical relations between concepts (BUNTINS et al., 2016). This can be achieved through a more contextualized approach, building on the comparison horizons of a typology. [53]

Deep engagement with the methodological foundations reveals that translating qualitatively reconstructed typologies into concrete items requires an ongoing iterative alignment between the items and the typology. The process of item development and validation—for example, through respondent feedback (e.g., cognitive pretests) and expert reviews (e.g., group Delphi)—is therefore essential for exploring varying levels of abstraction, balancing tensions, and achieving an optimal alignment incrementally. [54]

Overall, this article is seen as contributing to mixed methods research by addressing three central areas of methodological development: First, we propose a reflexive and epistemologically grounded understanding of integration. Rather than assuming a linear transfer of qualitative results into quantitative formats, we conceptualize integration as a dynamic process of translation that requires critical reflection on the underlying methodological foundations and aims at mutual enrichment between research strands. We conceptualize methodologies "as not only choices of methods, but as epistemological standpoints with their own conceptual and philosophical underpinnings" (FRESHWATER & CAHILL, 2023, p.82). From this perspective, we recognize the need to first identify and address epistemological gaps that must be bridged. Our approach resonates with the concept of "reflexive integration" (OLAGHERE, 2022, p.1), emphasizing the importance of transparency and comprehensibility in methodological decisions, which then serve as the foundation for deeper reflection and analysis. [55]

Second, we demonstrate how a clearly defined methodological framework—in our case, the documentary method—can serve as a productive starting point for developing a standardized measurement instrument. This framework preserves the epistemological value of qualitative-reconstructive research and allows for systematic item construction that remains faithful to the logic of typification. Our strategy does not seek to subordinate the qualitative to the quantitative or reduce it to mere quantification, as is often framed in mixed methods research (HESSE-BIBER, 2010; LOVE & CORR, 2021). Instead, we emphasize the importance of acknowledging the inherent epistemological value of the qualitative study, positioning it as the foundation for subsequent inquiry to uphold the principles of appropriate use of qualitative data (MORSE, 2006). [56]

Third, we introduce qualitative-reconstructive approaches, particularly the Documentary Method, into the mixed methods discourse. This method offers a distinctive methodology to uncovering implicit bodies of knowledge, moving beyond explicit, surface-level data to access the deeper, practice-oriented dimensions of social phenomena. Expanding the qualitative-reconstructive perspective creates significant opportunities for future research, as corresponding typologies are prevalent within the discourse but are often underutilized for further exploration. With our framework, we aim to provide a pathway toward achieving a more nuanced understanding of complex phenomena and fostering deeper epistemological integration. [57]

Åkerblad, Leena; Seppänen-Järvelä, Riita & Haapakoski, Kaisa (2021). Integrative strategies in mixed methods research. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 15(2), 152-170, https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689820957125 [Accessed: August 22, 2025].

Bazeley, Pat (2024). Conceptualizing integration in mixed methods research. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 18(3), 225-234, https://doi.org/10.1177/15586898241253636 [Accessed: August 22, 2025].

Bohnsack, Ralf (2010). Documentary method and group discussions. In Ralf Bohnsack, Nicole Pfaff & Wivian Weller (Eds.), Qualitative analysis and documentary method in international educational research (pp.99-124). Opladen: Verlag Barbara Budrich, https://doi.org/10.3224/86649236 [Accessed: August 22, 2025].

Bohnsack, Ralf (2017). Praxeological sociology of knowledge and documentary method: Karl Mannheim's framing of empirical research. In David Kettler & Volker Meja (Eds.), The Anthem companion to Karl Mannheim (pp.199-220). London: Anthem Press.

Bohnsack, Ralf; Pfaff, Nicolle & Weller, Wivian (Eds.) (2010a). Qualitative analysis and documentary method in international educational research. Opladen: Verlag Barbara Budrich.

Bohnsack, Ralf; Pfaff, Nicolle & Weller, Wivian (2010b). Reconstructive research and documentary method in Brazilian and German educational science—an introduction. In Ralf Bohnsack, Nicole Pfaff & Wivian Weller (Eds.), Qualitative analysis and documentary method in international educational research (pp.7-40). Opladen: Verlag Barbara Budrich, https://doi.org/10.3224/86649236 [Accessed: August 22, 2025].

Borgstede, Matthias & Rau, Caroline (2023). Beyond quality and quantity: Representing empirical structures by embedded typologies. Frontiers in Education, 8, https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2023.1087908 [Accessed: September 12, 2025].

Borgstede, Matthias & Scholz, Marcel (2021). Quantitative and qualitative approaches to generalization and replication–a representationalist view. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 605191, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.605191 [Accessed: August 22, 2025].

Bourdieu, Pierre (1977 [1972]). Outline of a theory of practice (transl. by R. Nice). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bryman, Alan (2006). Integrating quantitative and qualitative research: How is it done?. Qualitative Research, 6(1), 97-113.

Buntins, Matthias; Buntins, Katja & Eggert, Frank (2016). Psychological tests from a (fuzzy-)logical point of view. Quality & Quantity, 50(6), 2395-2416.

Coates, Adam (2021). The prevalence of philosophical assumptions described in mixed methods research in education. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 15(2), 171-189.

Costa, Jana & Taube, Dorothea (2024). Bestehende Daten in der Forschung zu Bildung für nachhaltige Entwicklung neu entdecken: Qualitativ-rekonstruktive Befunde als theoriegeleitete Such- und Strukturierungsperspektive für die Reanalyse von Datensätzen. In Helge Kminek, Verena Holz & Mandy Singer-Brodwoski (Eds.), Bildung für eine nachhaltige Entwicklung im Umbruch? Beiträge zur Theorieentwicklung angesichts ökologischer, gesellschaftlicher und individueller Umbrüche (pp.187-208). Leverkusen: Verlag Barbara Budrich, https://doi.org/10.3224/84742736 [Accessed: September 12, 2025].

Creswell, John W. & Plano Clark, Vicki L. (2011). Designing and conducting mixed methods research (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

DeJonckheere, Melissa; Vaughn, Lisa M.; James, Tyler G. & Schondelmeyer, Amanda C. (2024). Qualitative thematic analysis in a mixed methods study: Guidelines and considerations for integration. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 18(3), 258-269.

Fielding, Nigel G. (2012). Triangulation and mixed methods designs: Data integration with new research technologies. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 6(2), 124-136.

Freshwater, Dawn & Cahill, Jane (2023). The role of methodological paradigms for dialogic knowledge production: Using a conceptual map of discourse development to inform mixed methods research design. In Cheryl N. Poth (Ed.), The Sage handbook of mixed methods research design (pp.79-91). London: Sage.

Hesse-Biber, Sharlene (2010). Qualitative approaches to mixed methods practice. Qualitative Inquiry, 16(6), 455-468, https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800410364611 [Accessed: August 22, 2025].

Hinzke, Jan-Hendrik; Gevorgyan, Zhanna & Matthes, Dominique (2023). Study review on the use of the documentary method in the field of research on and in schools in English-speaking scientific contexts. In Jan-Hendrik Hinzke, Tobias Bauer, Alexandra Damm, Marlene Kowalski & Dominique Matthes (Eds.), Dokumentarische Schulforschung. Schwerpunkte: Schulentwicklung – Schulkultur – Schule als Organisation (pp.213-231). Bad Heilbrunn: Verlag Julius Klinkhardt, https://doi.org/10.35468/6022-11 [Accessed: August 22, 2025].

Johnson, R. Burke & Onwuegbuzie, Anthony J. (2004). Mixed methods research: A research paradigm whose time has come. Educational Researcher, 33(7), 14-26.

Kafka, Franz (2025 [1915]). The metamorphosis. As well as the retransformation of Gregor Samsa by Karel Brand. Prague: Vitalis.

Langfeldt, Bettina & Goltz, Elke (2017). Die Funktion qualitativer Vorstudien bei der Entwicklung standardisierter Erhebungsinstrumente: Ein Beispiel aus der Evaluationsforschung in militärischem Kontext. KZfSS Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie, 69(S2), 313-335.

Leising, Daniel & Borgstede, Matthias (2019). Hypothetical constructs. In Vigil Zeigler-Hill & Todd K. Shackelford (Eds.), Encyclopedia of personality and individual differences. Cham: Springer.

Love, Hailey R. & Corr, Catherine (2021). Integrating without quantitizing: two examples of deductive analysis strategies within qualitatively driven mixed methods research. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 16(1), 64-87.

Mannheim, Karl (1936 [1929]). The sociology of knowledge. In Karl Mannheim (Ed.), Ideology and utopia. An introduction to the sociology of knowledge (pp.237-280). New York: Harcourt, Brace.

Mannheim, Karl (1982 [1980]). Structures of thinking (transl. and ed. by D. Kettler, V. Meja & N. Stehr). London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Morse, Janice M. (2006). The politics of evidence. Qualitative Health Research, 16(3), 395-404.

Olaghere, Ajima (2022). Reflexive integration of research elements in mixed-method research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 21, https://doi.org/10.1177/16094069221093137 [Accessed: August 22, 2025].

Peirce, Charles S. (1998). The essential Peirce: Selected philosophical writings (Volume 2, 1893-1913) (ed. by The Peirce Edition Project). Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Polanyi, Michael (1966). The tacit dimension. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Rau, Caroline (2020). Kulturtradierung in geisteswissenschaftlichen Fächern. Eine rekonstruktive Studie zu epistemologischen Überzeugungen von Lehrkräften. Bad Heilbrunn: Verlag Julius Klinkhardt, http://dx.doi.org/10.35468/5811 [Accessed: August 22, 2025].

Rau, Caroline (2021). Die Wissensgrundlagen des eigenen Fachs verstehen – empirische Befunde zu den epistemologischen Orientierungen von Lehrkräften geisteswissenschaftlicher Fächer. Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft, 24(1), 91-112, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11618-021-00992-y [Accessed: August 22, 2025].

Sandelowski, Margarete; Voils, Corrine I. & Knafl, George (2009). On quantitizing. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 3(3), 208-222.

Scheunpflug, Annette; Krogull, Susanne & Franz, Julia (2016). Understanding learning in world society: Qualitative reconstructive research in global learning and learning for sustainability. International Journal of Development Education and Global Learning, 7(3), 6-23, https://doi.org/10.18546/IJDEGL.07.3.02 [Accessed: August 22, 2025].

Schoonenboom, Judith (2023). The fundamental difference between qualitative and quantitative data in mixed methods research. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 24(1), Art. 11. http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-24.1.3986 [Accessed: September 16, 2025].

Schurz, Gerhard (2008). Patterns of abduction. Synthese, 164(2), 201-234.

Schütz, A. (1971). Gesammelte Aufsätze 1. Das Problem der sozialen Wirklichkeit. Den Haag: Martinus Nijhoff.

Taube, Dorothea (2024). Complexity as a challenge in teaching sustainable development issues: An exploration of teachers' beliefs. Environmental Education Research, 30(3), 361-376.

Timm, Susanne; Kaukko, Mervi & Scheunpflug, Annette (2023). Preservice teachers' professional beliefs in relation to global social change: Findings from Finland and Germany. Teaching and Teacher Education, 132, 104239, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2023.104239 [Accessed: August 22, 2025].

Watkins, Daphne C. (2023). Secondary data in mixed methods research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Watkins, Daphne C. & Johnson, Natasha C. (2023). Advancing education research through mixed methods with existing data. In Rob Tierney, Fazal Rizvi & Kadriye Ercikan (Eds.), International encyclopedia of education (4th ed., pp.636-644). Oxford: Elsevier.

Zhou, Yuchun & Wu, Min Lun (2022). Reported methodological challenges in empirical mixed methods articles: A review on JMMR and IJMRA. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 16(1), 47-63.

Jana COSTA is a postdoctoral researcher at the Leibniz Institute for Educational Trajectories (LIfBi). In her research, she explores questions of sustainability education in the contexts of informal learning, social inequality, and teacher professionalism. She is particularly interested in the potential of mixed methods approaches, including the secondary analysis of large-scale assessment data.

Contact:

Dr. Jana Costa

LIfBi – Leibniz-Institut für Bildungsverläufe

Abteilung: Kompetenzen, Persönlichkeit, Lernumwelten

Wilhelmsplatz 3, 96047 Bamberg, Germany

E-Mail: jana.costa@lifbi.de

URL: https://www.lifbi.de/de-de/Start/Institut/Personen/Person/account/2089

Caroline RAU is a research assistant at the Department "Foundations of Education" of the University of Bamberg and the managing director of the Journal for International Educational Research and Development Education. In her research, she focuses on culture-related teacher training and didactics, and on integrating and combining quantitative and qualitative-reconstructive methods.

Contact:

Dr. Caroline Rau

University of Bamberg

Faculty of Human Sciences and Education, Institute for Educational Science, Department of “Foundations of Education”

Markusplatz 3, 96047 Bamberg, Germany

E-mail: caroline.rau@uni-bamberg.de

URL: https://www.uni-bamberg.de/allgpaed/lehrstuhlteam/mitarbeiterinnen-und-mitarbeiter/dr-caroline-rau/

Costa, Jana & Rau, Caroline (2025). Bridging qualitative reconstructive typologies and quantitative measurement: A reflective approach to methodologically sound item development for the assessment of teachers' epistemological beliefs in teaching humanities subjects [57 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 26(3), Art. 17, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-26.3.4361.