Volume 26, No. 2, Art. 1 – May 2025

Relationship Visibility in Spaces of Networked Individualism: How Couples Navigate Contrasting Injunctive Norms of Visual Communication

Federico Lucchesi & Katharina Lobinger

Abstract: Visual communication of romantic partners on social network sites (SNSs) is tied to normative discourses addressing different reference groups. By sharing pictures of the couple (relationship visibility), partners legitimize their romantic bond, increase relationship satisfaction, or discourage alternative partners. Nevertheless, injunctive norms of visual communication on SNSs often emerge from individual-focused SNS affordances, encouraging self-centered visual sharing. Generally, SNSs are understood as sites of networked individualism where individuals relate to others while remaining focused on themselves. We examined the injunctive norms governing relationship visibility on SNSs, discussing how partners navigate the tensions between norms stemming from individual-focused SNS affordances and relational norms. We conducted 63 semi-structured pair and individual interviews with romantic partners (42 participants, 21 couples), using participatory visual elicitation techniques. In the attempt to balance individual autonomy with relational and audience expectations, we found that partners develop practices to navigate contrasting norms. Key norms concern the extent of shared visual cues, timing and selection of SNS spaces for couple pictures, volume of sharing, and rules for sensitive pictures to maintain privacy. We provide insights into the complex negotiations between individual-focused norms and relational norms of visual communication on SNSs.

Key words: visual communication; injunctive norms; social network sites; relationship visibility; networked individualism; romantic relationships; qualitative interviews

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. Social Network Sites as Sites of Networked Individualism

3. Relationship Visibility on SNSs

4. Visual Communication on SNSs and Social Norms

5. Methods

6. Results

6.1 Social network sites as individual-focused platforms

6.2 Norms of relationship visibility on SNSs

7. Discussion

8. Conclusion

To maintain their relationships, couples need to balance both relational and individual needs. This also involves using social network sites (SNSs), which are often part of the communication repertoire established by romantic partners. SNSs, increasingly visual platforms (e.g., LEAVER, HIGHFIELD & ABIDIN, 2020; SCHMIDT & WIESSE, 2019) can be understood as sites of networked individualism (WELLMAN et al., 2003), where partners can focus on the individual self while simultaneously presenting their relationships favorably to their audience(s). [1]

When visually communicating on SNSs, romantic partners must consider various social norms. Norms have been defined in various ways (e.g., CHUNG & RIMAL, 2016) but can generally be understood as customary rules that define the boundaries of social behavior, eliciting conformity mechanisms (BICCHIERI, 2005). Norms have been categorized as either descriptive or injunctive (CIALDINI, KALLGREN & RENO, 1991). Descriptive norms indicate what most people do, while injunctive norms reflect the perception of what is socially approved or disapproved (i.e., what people should do). [2]

In our work, we understand norms as frameworks adopted by individuals to determine and judge what is socially desired and acceptable—or unacceptable—in a given context (AARTS & DIJKSTERHUIS, 2003; NISSENBAUM, 2011). In the context of SNSs, norms can be seen as evaluations of acceptable practices (DETEL, 2007) that occur when communicating on these platforms. In other words, in our study we were interested in what romantic partners consider appropriate in terms of SNS use (injunctive norms) rather than actual behaviors (descriptive norms). However, such evaluations of appropriateness depend on the reference group, that is, "a group, collectivity, or person which the actor takes into account in some manner in the course of selecting a behavior from among a set of alternatives, or in making a judgment" (KEMPER, 1968, p.32). As partners must acknowledge different audiences and thus different reference groups when visually communicating on SNSs, they sometimes need to navigate contrasting norms. [3]

On the one hand, individuals may follow norms considering a generalized audience as a reference group, which includes several kinds of SNS users often being perceived as a collective. These norms of SNS use can be learned through media exposure (e.g., GEBER & HEFNER, 2019; GUNTHER, BOLT, BORZEKOWSKI, LIEBHART & DILLARD, 2006; MABRY & MACKERT, 2014) and through SNS affordances (e.g., CABIDDU, DE CARLO & PICCOLI, 2014; MAJCHRZAK, FARAJ, KANE & AZAD, 2013), which establish "the perceived range of possible actions linked to the features of the platform" (BUCHER & HELMOND, 2018, p.235). Several contextual factors can influence how a romantic partner perceives SNS affordances (CALIANDRO & ANSELMI, 2021; ISLAM, LAATO, TALUKDER & SUTINEN, 2020; ZHENG & YU, 2016). For example, researchers emphasized that SNS affordances are influenced by cultural norms, often highlighting neoliberal discourses and individual self-interest (e.g., BOYD, 2011). According to neoliberal ideology (HARVEY, 2005), social solidarity and collective ethics have been largely replaced with a stronger focus on the self and self-development (BOURDIEU, 1998 [1998]; ROSE, 1990). From this perspective, the individual is seen as a free, autonomous entrepreneur of the self who acts—also in the context of SNSs—to maximize self-value through perpetual self-care (GERSHON, 2011; TÜRKEN, NAFSTAD, BLAKAR & ROEN, 2016). While we do not explore the impact of individualization (BECK & BECK-GERNSHEIM, 2002 [2001]) on romantic relationships, we acknowledge that SNS affordances imply individual-focused norms of SNS use. [4]

On the other hand, individuals can follow norms, considering the romantic partner—and their romantic relationship—as a reference group. Indeed, norms can depend on the social pressure perceived by important individuals in one's social circle (AJZEN, 1991) or, in other words, the perception of what significant others expect1) one to do (PARK & SMITH, 2007) when communicating on SNSs. Among various types of close relationships, romantic relationships (COLLINS, WELSH & FURMAN, 2009),2) with their internal norms often stemming from shared expectations (CLARK & MILLS, 1979; SAKALUK, BIERNAT, LE, LUNDY & IMPETT, 2020), have a decisive influence on individuals' lives. In romantic relationships, norms provide order and meaning, reducing ambiguity and uncertainty (RAVEN & RUBIN, 1976), allowing romantic partners to determine and judge desirable social behavior in a particular context (NISSENBAUM, 2004). Such norms can start with normative expectations and are then communicatively constructed, continuously negotiated, or reconfirmed in social interactions (VENEMA, 2021). [5]

Individuals seek to be interdependent and affiliated with their partners (BERSCHEID & REIS, 1998) while feeling autonomous and distinctive (DECI & RYAN, 2000). However, when using SNSs, balancing these needs—being part of the "we" without sacrificing the "me" (SLOTTER, DUFFY & GARDNER, 2014)—can be challenging. Romantic partners may perceive SNSs as platforms with norms of use that focus exclusively on the "me." For instance, individuals are expected to use SNSs for self-tracking, self-optimization, or self-presentation (MAYER, ALVAREZ, GRONEWOLD & SCHULTZ, 2020). In previous investigations, researchers focused on how single individuals perceive the norms of SNS use (e.g., McLAUGHLIN & VITAK, 2012). However, there is a lack of studies regarding how partners make sense of the norms of SNS use when also facing norms stemming from shared expectations of romantic relationships. [6]

In this article, we focus on how romantic partners navigate contrasting norms of visual communication on SNSs. Partners use a vast range of visuals as part of their communication repertoires for maintaining relationships (LUCCHESI & LOBINGER, 2024a), as visual communication fulfills various social functions (LOBINGER, 2016; VAN HOUSE, DAVIS, AMES, FINN & VISWANATHAN, 2005). On SNSs, individuals are expected to adopt visual communication for presenting themselves (KRELING, MEIER & REINECKE, 2022; USKI & LAMPINEN, 2016) and for providing positive information about their romantic partners (VANDERDRIFT, TYLER & MA, 2015). Furthermore, their visual sharing strategies are often tailored to meet the perceived expectations of the imagined audience (LITT, 2012; STSIAMPKOUSKAYA, JOINSON, PIWEK & STEVENS, 2021; TAO & ELLISON, 2023), presenting a complex array of social norms for SNS users to navigate. [7]

Thus, we address the following research question: Which injunctive norms govern relationship visibility on SNSs? In this regard, we were particularly interested in how romantic partners navigate the intersection between norms stemming from individual-focused SNS affordances and norms stemming from relational expectations when visually communicating on SNSs. [8]

The article is part of a four-year research project funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF), in which we examined the norms and functions of visual communication in close relationships in Switzerland. While in the overall research we examined both friendships and romantic relationships, for the sake of this paper we focus only on romantic relationships. Through 63 semi-structured pair and individual interviews with 42 partners (i.e., 21 couples), we asked the respondents to reflect on the perceived social norms associated with their visual communication on SNSs while exploring the relational expectations tied to SNS use. [9]

The paper starts with a theoretical introduction (Section 2) defining and understanding SNSs as sites of networked individualism (WELLMAN et al., 2003). We then outline how previous researchers investigated visual relationship presentation on SNSs (Section 3) by introducing the concepts of tie-signs (GOFFMAN, 1971) and relationship visibility (EMERY, MUISE, DIX & LE, 2014), and discussing norms of visual communication on SNSs (Section 4). Subsequently, we describe our methodology (Section 5). Finally, we present our results (Section 6), discuss the conclusions (Section 7), and suggest directions for further research (Section 8). [10]

2. Social Network Sites as Sites of Networked Individualism

SNSs were described as "designed for and expected people to be individualistically minded" (JENKINS, ITŌ & BOYD, 2015, p.29). Most platforms continue to require people to enter personal information, such as first and last name, date of birth, biography, or profile picture. Some, such as Facebook, address the individual user with direct questions ("What are you thinking about?"). Similarly, platform settings, policies, and, generally, affordances are tailored to the single individual. While SNS affordances do not compel users to make individual-focused use of the platforms, they are configured in such a way that users typically perceive (see NAGY & NEFF, 2015, for a focus on "imagined affordances") as suitable for individual-focused use (BOYD, 2011). [11]

SNSs are platforms "primarily promoting interpersonal contact, whether between individuals or groups" (VAN DIJCK, 2013, p.8). However, within a networked society, maintaining ties on SNSs revolves around the mutual sharing of content—whether user-generated or found online—that pertains to personal daily experiences (BARNARD, 2016). While the function of maintaining interpersonal relationships remains central to SNSs, it is primarily based on an individualistic logic rooted in the self-presentation (GOFFMAN, 1959 [1956]) of an individual (networked) self (FUCHS, 2014) aware of algorithmically directed feeds (BHANDARI & BIMO, 2022). Through this logic, SNS users can build and cultivate networks while fulfilling individual needs for self-improvement and self-care (BAKARDJIEVA & GADEN, 2012). Such a focus on the self has even been described as "seriously narcissistic" (JENKINS et al., 2015, p.28). Acknowledging SNS use as individual-focused does not deny the relational nature of the platforms. Instead, it highlights that the maintenance of ties occurs through sharing interests, values, and experiences that are primarily individual (CASTELLS, 2014). In other words, SNSs can be used to affirm one's identity and care for one's image within a network where interpersonal relationships are maintained. [12]

Coherently, SNSs are described as sites of networked individualism (WELLMAN et al., 2003), where networks are loose, fragmented, and revolve around an individual who is always connected with others but remains focused on the self. Facilitated by the context collapses (MARWICK & BOYD, 2011) of SNSs, that is, sharing content with an audience potentially composed of people from different social spheres, "people function more as connected individuals and less as embedded group members" (RAINIE & WELLMAN, 2012, p.12) on these platforms. Understanding these perspectives is crucial for examining how romantic relationships are visually presented and potentially perceived on SNSs. [13]

3. Relationship Visibility on SNSs

One of the primary uses of SNSs is to curate a personal profile and share content that can potentially reach multiple audiences. The practice of regulating shared information to shape the perception conveyed to an audience was termed impression management (GOFFMAN, 1959 [1956]). On SNSs, impression management often focuses on the individual's self-presentation (FOX & VENDEMIA, 2016; HERNÁNDEZ-SERRANO, JONES, RENÉS-ARELLANO & CAMPOS ORTUÑO, 2022; VÖLCKER & BRUNS, 2018). However, beyond individual self-presentation, users may also choose to highlight their relationship which is a significant decision for romantic partners. Romantic partners typically aim to feel affiliated with the other (BREWER & ROCCAS, 2001), and presenting a relationship on SNSs might reflect a desire for connection and closeness (HUGHES, CHAMPIONS, BROWN & PEDERSEN, 2021). For example, partners employ so-called "tie-signs" (GOFFMAN, 1971, p.210), which are "objects, acts, expressions, or documentary statements" (p.210) that both testify to the existence of the relationship and provide details about it. Tie-signs on SNSs can take various forms, such as couple photographs, tags, relationship information, cues for expressing love and affection through comments or posts, or the interconnection between two partners' profiles through links or statuses. [14]

EMERY et al. (2014) distinguished relationship presentation on SNSs between relationship visibility (showing relationships within the visuals shared by a user) and relationship disclosure (the more generic sharing of personal details about a relationship). Researchers showed that communicating a relationship on SNSs can legitimize its existence (BEVAN et al., 2015; ROBARDS & LINCOLN, 2016) and protect it from alternative partners (KRUEGER & FOREST, 2020); can increase relationship satisfaction (BRODY, LeFEBVRE & BLACKBURN, 2016; ITO, YANG & LI, 2021; TOMA & CHOI, 2015); or become a subject for potential jealousy and negative consequences (IMPERATO, EVERRI & MANCINI, 2021; MUSCANELL, GUADAGNO, RICE & MURPHY, 2013; PAPP, DANIELEWICZ & CAYEMBERG, 2012). However, particularly with respect to romantic relationships, relationship presentation is not easily distinguishable from self-presentation. According to VANDERDRIFT et al. (2015), sharing "information about one's romantic relationship represents just another type of self-oriented information" (p.454). This is hardly surprising as psychology researchers indicated that people in romantic relationships frequently incorporate each other into their sense of self (ARON, 2003; ARON, ARON & SMOLLAN, 1992). In other words, SNSs as self-focused platforms facilitate self-presentation, but the emphasis can be on public displays of relationships that validate and present the self through the dynamic process of connecting socially with others. In this way, the individual and collective aspects of one's identity are presented in tandem (PAPACHARISSI, 2010). However, norms stemming from relational expectations are not necessarily satisfied, as relationship visibility can be read as a self-presentation act that depends merely on individual-focused norms of SNS use (CHRISTOFIDES, MUISE & DESMARAIS, 2009). [15]

4. Visual Communication on SNSs and Social Norms

In this paper, we understand visual communication as "the circulation of non-linguistic pictorial elements that feature in cultural artifacts distributed via media technologies" (AIELLO & PARRY, 2020, p.4). Indeed, visual communication does not rely solely on the content of the image (GÓMEZ-CRUZ & ARDÈVOL, 2013) and thus addressing what people do with visuals is also essential for interpreting and understanding the concealed meanings (HAND, 2022). In exploring visual communication, we go beyond the surface of visuals as presented by visual motifs (EDWARDS, 2012). In addition to the content, we consider the artifact character of visuals, including their material attributes and functions within communicative practices in the context of multimodal visual technologies and SNSs (LOBINGER, 2016; see Section 5 for more details). This approach aligns with the concept of "texto-materiality" proposed by SILES and BOCZKOWSKI (2012). [16]

Norms play a crucial role in how romantic partners decide to visually present themselves on SNSs (McLAUGHLIN & VITAK, 2012; USKI & LAMPINEN, 2016) since having control over self-presentation is considered essential to balance privacy and disclosure online (MARWICK & BOYD, 2011). On certain occasions, norms on SNSs are implicit and not explicitly discussed (HOOPER & KALIDAS, 2012) but are internalized by observing the online behavior of other users (McLAUGHLIN & VITAK, 2012). In other cases, norms can emerge from disagreements and negotiations with respect to desirable rules for the use of visuals on SNSs (e.g., LUCCHESI & LOBINGER, 2024b; USKI & LAMPINEN, 2016). Importantly, being aware of a norm does not always result in actual SNS use that respects that norm (STEIJN, 2016). [17]

According to NISSENBAUM (2004), norms vary depending on the social context in which they occur. Nonetheless, because of the context collapse of SNSs, users can reach different social contexts (e.g., friends, partners, and colleagues), and thus different reference groups for whom different norms may apply. Individuals may follow norms deemed appropriate according to the imagined audience (LITT & HARGITTAI, 2016), which refers to those they expect to be part of the audience when sharing content on SNSs. As the technical features and algorithmic configurations of various SNSs are in constant evolution (ARRIAGADA & IBÁÑEZ, 2020), this dynamic landscape further influences the ongoing transformation of norms of SNS use. [18]

Furthermore, advancements in visual technologies, such as augmented reality, artificial intelligence, filters, and lenses, expanded the possibilities for creating engaging visuals (e.g., JAVORNIK et al., 2022), influencing what is considered visually appealing or engaging on SNSs (e.g., VENDEMIA & DeANDREA, 2018). However, these advancements also created new risks and challenges, such as perpetuating unrealistic beauty standards (BONNER, MATHIS, O'HAGAN & MCGILL, 2023). Visuals play a crucial role on SNSs, especially in forming the first impressions of other users (McLAUGHLIN & VITAK, 2012). Both pictures of the self (e.g., selfies) and couple or family pictures are shared to prompt the expected engagement of the audience, offering a glimpse into the user's personal experiences and subjective points of view (TRILLÒ et al., 2023; ZAPPAVIGNA, 2016). Overall, when sharing visuals on SNSs, individuals should consider moral and aesthetic criteria (TIIDENBERG, 2020). [19]

In front of their imagined audiences, individuals try to present themselves as engaging, likable, attractive, and socially connected (YAU & REICH, 2019); thus, they carefully construct and craft their self-presentation (MARWICK, 2013). To this end, and according to norms of SNS use, authors found that it is advisable to avoid overly personal (HOOPER & KALIDAS, 2012), overly emotional and negative content (ZILLICH & MÜLLER, 2019), and oversharing in general (McLAUGHLIN & VITAK, 2012). Similarly, researchers highlighted that seeking attention, constantly commenting on or liking someone else's photos, or sharing visuals that could embarrass others should be avoided (ibid.; see also MURUMAA & SIIBAK, 2012; YAU & REICH, 2019). According to VENEMA and LOBINGER (2017), individuals should obtain consent before publishing photos depicting others. Researchers also found that users believe that striving to publish authentic content (LOBINGER & BRANTNER, 2015; USKI & LAMPINEN, 2016) and avoiding dissonance between what is posted on SNSs and how individuals present themselves outside the platform is perceived as appropriate (OLLIER-MALATERRE & LUNEAU-DE SERRE, 2018; ZILLICH & MÜLLER, 2019). Although ZHAO, GRASMUCK and MARTIN (2008) found that individuals generally prefer sharing group pictures over self-portraits, other authors (e.g., STRANO, 2008) demonstrated that self-presentation is often deemed more appropriate than showcasing relationships. In any case, individuals believe that sharing visuals should make users appealing (MANAGO, GRAHAM, GREENFIELD & SALIMKHAN, 2008), and for this reason, it is typically more accepted when users consider themselves talented photographers (LOBINGER, VENEMA & KAUFHOLD, 2020). [20]

Moreover, which visual motifs are considered suitable varies depending on the SNS used because each platform presents unique methods of incorporating visual and multimodal elements (ADAMI & JEWITT, 2016). Indeed, not only the expectations of different reference groups but also different SNS affordances can play a role in shaping users' sharing behaviors, general norms of self-disclosure on SNSs (MASUR, BAZAROVA & DiFRANZO, 2023), and norms concerning the appropriateness of various photographic styles (e.g., KOFOED & LARSEN, 2016). For example, SNS affordances designed for ephemeral and semi-private sharing are often perceived as more suitable for the dissemination of unedited, authentic imagery, reflecting a more genuine self-presentation. Conversely, SNS affordances designed for the public and those that are wide-reaching are considered appropriate for sharing carefully edited and aesthetically satisfying pictures that align with a more polished and curated self-image (SCHREIBER, 2017). Beyond these considerations, McLAUGHLIN and VITAK (2012) found that the overarching goal of visual sharing on SNSs is to offer a comprehensive portrayal of one's social life. YAU and REICH (2018) reported that it is good practice, especially for women, to reciprocate likes and compliments for online pictures. Additionally, when visuals are exchanged in private conversations, individuals should avoid sending generic visuals perceived as not crafted for a specific user (VATERLAUS, BARNETT, ROCHE & YOUNG, 2016). [21]

Finally, researchers on romantic relationships highlighted that the norms of visual communication on SNSs can change according to the relationship stage. For instance, according to FOX and ANDEREGG (2014), people believe that monitoring the visual content published by a partner is accepted during the dating phase, while tagging each other in comments and pictures is more appropriate once the relationship is established. [22]

Up to this point, researchers primarily investigated norms of SNS' (visual) use by assuming that it is based solely on norms stemming from individual-focused affordances (e.g., CHEUNG & LEE, 2010). With our research, we aim to fill this gap by considering the role played by the romantic partner and by understanding the role played by those relational norms that stem from partners' expectations. Indeed, "much of human behavior is not best characterized by an individual acting in isolation [...] actual usage (of technology) is often done collaboratively or with an aim to how they fit in with, or affect, other people or group requisites" (BAGOZZI, 2007, p.247). Romantic partners are socially committed to a relationship and participate in shared decisions that are established or inferred within the couple. Such involvement influences how individuals perceive and internalize norms because they must also respect the interdependent expectations of the romantic relationship (KOROBOV, 2024; TUOMELA, 1995). In other words, while norms of SNS use may be self-focused and depend on SNS affordances, partners also need to face norms appropriate for maintaining the social identity of their romantic relationships (POSTMES, SPEARS & LEA, 2000). [23]

Given these considerations, we aim to explore the following questions: Which injunctive norms govern relationship visibility on SNSs? How do romantic partners navigate the discrepancy between norms stemming from individual-focused SNS affordances and relational norms when visually communicating relationships on SNSs? [24]

The data used for this article were derived from a larger project in which we investigated the functions, rules, and norms of visual communication in close relationships in Switzerland3). Between September 2019 and July 2021, we conducted 63 semi-structured, in-depth interviews with 21 romantic couples (42 adults, 18-91 years old, M=36.3). The interviews were conducted in multiple languages: (Swiss) German, English, French, and Italian. Participants were selected through a selective (or purposive) sampling approach (LAMNEK & KRELL, 2016) to ensure the greatest possible diversity regarding (regional) origins, ages, educational levels, professions, relationship durations, living situations, and familial statuses. This diversity also included childless and parent couples, as well as same-sex and different-sex partnerships (see LOBINGER, LUCCHESI & TARNUTZER, 2024, for further information about participants). [25]

To understand individual and relational perspectives on the norms of visual communication on SNSs, we combined semi-structured pair interviews (LOGEMANN & EGLI, 2024; LONGHURST, 2009) with subsequent individual interviews for each partner (BLAKE, JANSSENS, EWING & BARLOW, 2021) in the methodological approach. Each interview session lasted approximately 90-120 minutes. Creative visual methods were employed to enhance respondents' verbal narration, including network drawings (HEPP, ROITSCH & BERG, 2016) and visual elicitation techniques (HARPER, 2002; JENKINGS, WOODWARD & WINTER, 2008; LAPENTA, 2011; MAYRHOFER & SCHACHNER, 2013). The respondents were invited to reflect on the role of visual communication while narrating their everyday communication repertoires. During the interviews, the participants were encouraged to share the above mentioned visual elements with the researchers while discussing their meanings and functions. The researchers captured images of the visuals shown by the participants using the research cameras. The visual data were then anonymized, securely stored, and meticulously analyzed through qualitative content analysis (KUCKARTZ, 2014 [2002]) to substantiate the findings presented in this paper. [26]

One section of each interview focused on visual communication on SNSs. Although we did not focus on specific SNSs, platforms such as Instagram, Facebook, and, to a lesser extent, TikTok were frequently mentioned as primary channels for sharing visual content. We gathered information to identify the platforms used by the participants, the typical motifs of their shared visuals, and the meanings and functions behind these visuals. In examining the norms of visual communication on SNSs, we followed the approach taken in previous communication research studies, and we relied on self-reported practices and perceptions of the respondents (SHULMAN et al., 2017). Building on this research stream (e.g., ELMORE, SCULL & KUPERSMIDT, 2017), we investigated injunctive norms by asking our respondents about their perceptions and evaluations regarding practices of SNS use and relationship visibility. This approach was successfully adopted in previous studies (e.g., USKI & LAMPINEN, 2016; VENEMA & LOBINGER, 2017). Specifically, we asked the participants to describe which visual sharing practices they deemed appropriate and why. The participants reflected on the imagined audiences of their SNS channels and the expectations of their romantic partners (reference groups). Regarding relational norms, we explored whether these norms emerged from the negotiation of explicit rules between romantic partners. [27]

Throughout this process, we have understood and treated visuals as texto-material objects (LOBINGER, 2016; SILES & BOCZKOWSKI, 2012). This means that we recognize visuals as artifacts with dual articulations. For some research questions, a detailed analysis of the symbolic message (TARNUTZER, LOBINGER & LUCCHESI, 2024)—such as the image's motif, style, or aesthetic (the textual part of the definition)—is essential. In other instances, examining how the visual object (the material part of the definition) is embedded and understood within communication practices provides profound insights into visual practices (ibid.). Ideally, a comprehensive texto-material understanding considers both aspects. [28]

When examining norms, we argue that the narration surrounding the use of visuals in specific practices and the rationale behind their perceived appropriateness or inappropriateness are particularly relevant. Although we contend that what is considered and presented as appropriate or inappropriate in visual communication on SNSs may not always align with the actual practices of participants, in this paper, the verbal reflections and self-reported practices concerning visuals—often elicited based on specific images—are prioritized more than the visual motifs themselves. [29]

To delve deeper into the respondents' experiences and opinions, the individual interview included verbal prompts that elicited narratives and introduced normative evaluations. These prompts consisted of normative statements strategically formulated to present different perspectives on contested topics. Previous researchers showed that injunctive norms can be measured by asking individuals to evaluate behaviors deemed appropriate and commonly approved by different reference groups (e.g., LAPINSKI & RIMAL, 2005; RIMAL & LAPINSKI, 2015). The verbal prompts used in our interviews were adapted from normative statements provided by respondents in an earlier project (see, e.g., VENEMA & LOBINGER, 2017, 2020) and were subsequently adapted to the context of SNSs. Additionally, several test interviews were conducted before interviewing the 21 romantic couples involved in the present study. During the interviews, positive prompts such as "I'm glad to know that my partner follows my online public sharing activity" were used alongside negatively skewed statements like "My partner has really embarrassing photos of me but it's okay because I know they will not share them with others" and observations such as "I know some people that simply share too many pictures." Overall, all the statements contained a subject, an evaluated object/practice, an evaluative tone, an (un)desirable or (in)appropriate practice, and a potential legitimization or contestation of the practice (see VENEMA, 2021 for a framework for analyzing norms). This approach was designed to prompt the respondents to reflect on and articulate their evaluations of specific issues, providing a comprehensive understanding of their perspectives on the norms of SNS use within relationships. [30]

With participant consent, all interviews were audio-recorded, manually transcribed in their original languages, anonymized, and securely stored. Two researchers independently coded the verbal transcripts using NVivo software (KUCKARTZ, 2014 [2002]), applying a hybrid approach of inductive and deductive categorization. Each case consisted of a pair interview, two individual interviews, and, in some cases, additional video interviews.4) The final step involved conducting a thematic analysis (e.g., BRAUN & CLARKE, 2006) by applying a cross-case comparison across the 21 couples to identify commonalities and divergences across data regarding norms of SNS use. In the thematic analysis, we categorized norms by examining how romantic partners commented on their own practices, the practices of others (i.e., through verbal prompts), and, especially, the evaluations of (in)appropriate behaviors regarding relationship visibility on SNSs. [31]

We aimed to identify norms regarding relationship visibility on SNSs and to understand how romantic partners navigate the intersections between individual-focused platform norms and relational norms. In the following section, we describe the findings of the interviews. First, we contextualize relationship visibility within SNSs as individual-focused platforms. We then introduce and discuss the various injunctive norms that govern relationship visibility on SNSs, highlighting the potential roles played by different reference groups. [32]

6.1 Social network sites as individual-focused platforms

Most respondents consider SNSs to be personal platforms where the focus should be on the individual. This individual focus is a critical understanding that guides and contextualizes further reflections about appropriate and inappropriate ways of visually communicating relationships on SNSs. In this case, all users have their own profile and exclusive access and are expected to use it independently of their partner. Individual usage is suggested by the platform's perceived affordances and users' beliefs regarding behaviors considered appropriate by the imagined audience. [33]

6.1.1 Relationship visibility and self-oriented visual sharing

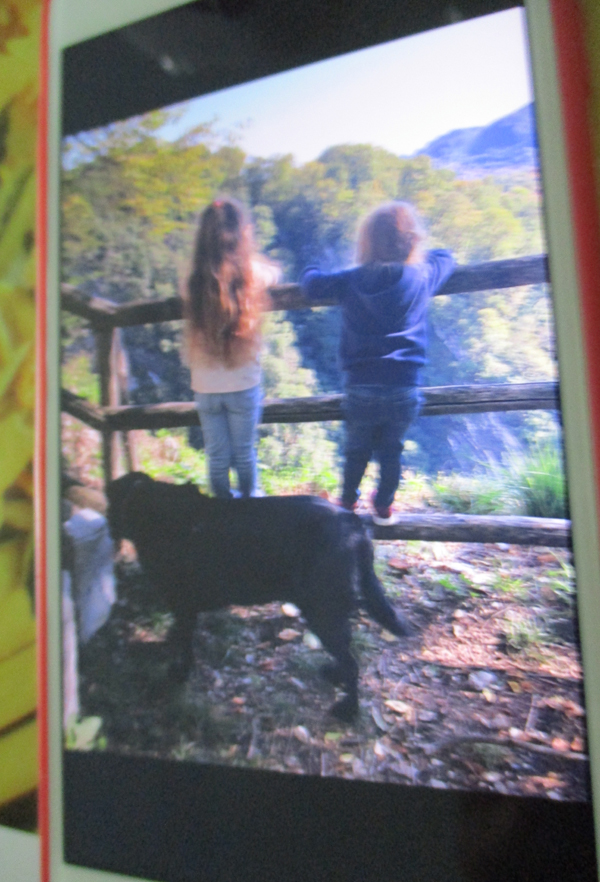

Given that SNS use is perceived as driven by individual-focused affordances, our respondents believed that appropriate visual communication should highlight the individual and their personal lives. "Social media is definitely about yourself5)" maintained Silvestro (male, 36 years old),6) "because initially, you give your name, surname, and details." Furthermore, the respondents argued that users should share only content potentially interesting to their audience, with the expectation that the imagined audience is interested in individual-related content. "If someone follows my Instagram profile, I think it's partly to see me, what I do," said Carolina (female, 19 years old). [34]

Considering SNSs as platforms for self-oriented sharing sometimes leads to contrasting opinions regarding the appropriateness of relationship visibility. In some cases, interviewees believed an SNS profile should be exclusively individual-focused. "I just think it is my profile and I do not have to show pictures of us on SNSs," said Hannah (female, 18 years old). Chiara (female, 21 years old) echoed this sentiment, emphasizing that "if I write my name, I publish Chiara." While showing us her SNS profiles during the interview, Chiara highlighted that she considers publishing photos with her boyfriend inappropriate because she believes her profile is personal and, thus, her image should be emphasized. However, it is interesting to note that among the few images she posted on her Instagram feed (Figure 1), one photograph displayed her with a friend.7) This decision might imply a different value attributed to pictures with partners and friends in reducing the centrality of self-image.

Figure 1: Chiara's Instagram feed [35]

For other respondents, focusing on oneself did not imply excluding information about the relationship or avoiding couple pictures. It was more about prioritizing oneself. "At least what I would show others about myself, well, it is more about me," explained Lucas (male, 28 years old). Additionally, even gathering information about the relationship was expected to result from an interest in the individual. "If someone follows you, searches for you, retrieves relationship information on your profile, they are doing it because they want to know something about you, about your person," said Silvestro. [36]

Many respondents highlighted the significance of including the partner in their online presence as a natural extension of their self-identity. As Tommaso (male, 33 years old) stated, "The social media profile concerns me, but part of me is also my companion, my wife. Therefore, I see no reason why not to publish photographs together." Similarly, Valentina (female, 30 years old) explained that on SNSs, one publishes photographs of oneself; thus, "if you are married or engaged, well, that is yourself." [37]

From this perspective, the decision to share couple pictures might be interpreted as a collateral effect, with the partner being reduced to one of the many elements that are part of one's personal life, and that is why it must be visually shown online. Carolina explained:

"They are part of my life [the photos with the partner], I publish them because they happened. If I went to the sea alone there is a photo of the sea. If I went to the sea with Matteo [I would publish a photo of the sea with us because] my life was about being at the sea with him." [38]

In other words, displaying the relationship on SNSs can convey a partner’s deep integration into an individual's self-identity. However, this tendency could also suggest that couple pictures are shared as part of a normative discourse emphasizing self-focus rather than the relationship itself. [39]

6.1.2 Personal autonomy in visual sharing

Our interviews confirmed that SNSs are considered individual-focused platforms, particularly regarding decisions about published content. Usually, the decision to post a couple picture on one's SNS profile should remain an individual choice. Marianna (female, 31 years old) clarified that it is appropriate to "manage my profiles myself and decide what to put on them." Partners even argued that, given the individual-focused nature of the profile, it would be inappropriate to have a say in each other's decisions. Giuseppina (female, 35 years old) explained, "I am not saying that I do not care about what he posts [her partner], but I believe it is his profile, so, essentially, he can post whatever he wants." Diego (male, 32 years old) emphasized uncompromisingly: "My page is my page, her page is her page. [...] Neither of us has the right to prevent or suggest what to post. It would be a violation of freedom." [40]

However, this belief about who should decide on sharing couple pictures can become problematic. Another norm, as reported by our respondents, is reciprocal communication. According to this norm, if one partner decides to publish a couple picture, making the relationship visible to their audience, the other partner should do the same. This norm arises from the belief that since the imagined audience of a couple often includes some of the same people, both partners should share similar relationship visibility. For example, one respondent expressed frustration with her partner's lack of couple pictures on Instagram despite her frequent posts about their relationship. This highlights a common issue: Respondents value mutual engagement on SNSs but recognize their partner's right to choose their own content. The absence of reciprocal sharing might lead to disappointment within the relationship and raise concerns about how the audience perceives this imbalance. [41]

While the respondents generally agreed that self-oriented sharing is an established norm, this does not mean it must always be adhered to. For example, Natalia (female, 29 years old) explained that although she believes SNSs are designed as individual-focused platforms where one should share the self, choosing what to publish remains "a personal choice, depending on how one wants to use them." In contrast, she and her partner Patricia (female, 40 years old) decided to use SNSs jointly. This approach does not involve sharing passwords or using shared profiles but entails a mutual decision to focus exclusively on sharing aspects of their relationship. Together, Natalia and Patricia strategically selected photos to share on their SNS profiles, ensuring a variety of content to avoid repetition among different profiles and platforms, which, again, points to platform-specific norms that imply certain images and certain image styles as being adequate. With shared contacts and friends, their curated visual content aimed to maintain their audience's engagement. However, the case of Natalia and Patricia confirms that there is often a divergence between injunctive norms and actual behaviors on SNSs. [42]

6.2 Norms of relationship visibility on SNSs

According to the respondents, various norms govern how romantic partners should visually communicate their relationships on SNSs. Although SNSs are generally considered individual-focused platforms, and relationship visibility is often seen as part of one's self-identity, romantic partners reported that visually communicating their relationship is appropriate for internally and externally confirming the relationship. Publishing couple pictures on SNSs can be helpful for "sharing particular moments, [...] for example, an important anniversary day [...] it is like celebrating together with friends who see our photos" (Diego, male, 32 years old). [43]

Relationship visibility also reflects a mutual expectation of expressing closeness and interest in each other. Giuseppina (female, 35 years old) emphasized, "the fact that he [the boyfriend] cares to show our relationship, the fact that it is important for him to publish a photo of us, is a demonstration of affection." Our interviews showed that the respondents are aware of relational norms concerning relationship visibility. According to the interviewees, romantic partners have to carefully consider the appropriate ways and timing for visually sharing their relationship on SNSs, evaluating its appropriateness not only based on SNS affordances but also considering the partner and the romantic relationship itself. Norms of relationship visibility concern the appropriate extent of visual clues that should be shared, the appropriate timing for sharing couple pictures within the relationship chronology, the appropriate SNS spaces where relationship visibility should be conveyed, and the appropriate volume of sharing. Furthermore, the participants also reported norms regarding appropriate measures and choices to adopt when sharing sensitive pictures and to keep the relationship private enough. [44]

6.2.1 Visibility in the early relationship stages

Particularly in the early stages of a romantic relationship, partners believe that the visibility of the relationship should be approached with caution. During these phases, the practice of sharing tie-signs is considered particularly appropriate. As Marianna (female, 31 years old) explained, shared visuals on SNSs "do not necessarily have to be pictures of the two of us but can also be things we have done or seen together. Automatically, even if we are not in the photo, we know." For example, Alberto (male, 25 years old) posted a picture on Instagram of two indistinguishable figures—himself and his girlfriend—relaxing in a van at the beach (Figure 2). Although it is evident that two people are present, it is not clear to the audience that they are a couple. Similarly, Fiona (female, 26 years old) underlined that sharing implicit tie-signs is considered an appropriate strategy when one partner prefers not to disclose the relationship publicly yet finds pleasure in sharing content related to moments spent together. In both cases, such shared knowledge, exclusive to the partners, strengthens their bonds by enhancing intimacy and complicity.

Figure 2: Tie-signs on SNSs [45]

6.2.2 Timing for posting couple pictures

Another injunctive norm governs the most appropriate time to post couple pictures. While using tie-signs is considered particularly appropriate at the beginning of a relationship, most respondents agreed that publishing couple pictures should only start on one's SNS profile when the relationship is well established and solid. This means that the relationship should be officially recognized and important to both partners. This norm suggests that a sufficient degree of intimacy between partners should be reached before publicly displaying the relationship on SNSs. These findings align with research on the importance of becoming "Facebook Official" to signal the beginning of a relationship online. In this sense, behavioral norms on SNSs mirror older forms of making a relationship official, such as the decision to introduce one's partner to family and friends. [46]

However, choosing the appropriate timing for publishing couple pictures can be a source of normative tension. Relational norms sometimes collide with evaluations of appropriate behavior based on SNS affordances and the imagined audience. Particularly in the early stages of a relationship, "liking or commenting is a way to show others that we are together," explained Costanza (female, 25 years old). Considering the imagined audience, sharing couple photographs early on is seen as appropriate to ward off potential suitors because SNSs are also believed to be channels used for approaching potential partners. Thus, the need for individual reassurance contrasts with the need to reach a recognized and reciprocated relational status before sharing couple pictures. [47]

According to Tommaso, posting a photograph in these early stages is appropriate because "it is nice that they see we are together. To not leave room for double meanings." Similarly, for Dreina (female, 22 years old) it was necessary "to make others understand how my relationship is going, that it is still my relationship because I know there is someone who is bothered by the fact that I have this relationship." Furthermore, in the case of a long-distance relationship, having photographs with one's partner visible to the public can help one feel more secure, thereby enhancing one's perception of the partner's closeness. In sum, the evaluation of the most appropriate time to share a couple picture varies depending on the reference group, requiring romantic partners to navigate a complex balance. [48]

6.2.3 Spaces for relationship visibility

To navigate this balance, the respondents believed the right compromise involves utilizing the ephemeral communication features of SNSs when present. For instance, on Instagram, sharing one's partner's presence on "stories"—short-lived posts that disappear after 24 hours8)—is deemed more acceptable in the early stages of a romantic relationship than posting couple pictures on the main feed, which is a permanent collection of posts visible on one's profile. This approach aligns with the idea that ephemerality implies less weight and importance of shared content, as it allows for experimentation and playfulness. Importantly, it does not remain visible and persistent on one's profile and thus in the audience's memory, reducing the social pressure associated with sharing. Continuing with the example of Instagram, it is expected that, at an appropriate later moment, the romantic relationship will also be shown on the feed, as this section is intended for the most personal pictures and close relationships. In contrast, more mundane and daily content and pictures with acquaintances of lesser intimacy are typically shared through stories. This again highlights that norms are closely linked to platform affordances. [49]

Finally, a picture of the couple can gain even more prominent visibility if shared as a profile picture. According to the respondents, this decision can indicate a reduced emphasis on personal individuality. Conversely, it may also represent the integration of the relationship into one's identity, serving as a public gesture of commitment. While this can project an image of stability and happiness to viewers, it has the potential to introduce undue pressure and set elevated expectations for the partner involved. [50]

6.2.4 Volume of shared content

The respondents also emphasized that oversharing couple pictures should be avoided, as it is considered a search for attention and can tire or annoy the imagined audience (reference group). "Posting many photographs seems to me a strong search for attention and a performance," suggested Alberto (male, 25 years old), who attributed this behavior to contemporary social norms. "In an era like this, it becomes a habit [...] a way to receive social approval, through likes, through the fact that people comment on you." In a society where, according to the respondents, individuals love to be in the spotlight, sharing too many images of one's relationship can be challenging for many users to refrain from. According to Matteo, posting relationship images "has almost become an obligation. There is no longer much privacy. In my opinion, a person who doesn't use social media much, who doesn't post much, then is also somewhat cut off." Once one starts to publish and share content related to a relationship, it can be challenging to stop, as it creates further expectations in the audience. Discontinuing such a habit would be equivalent to arousing suspicions about the status and satisfaction of the relationship. Alberto explained, underscoring the tendencies of peer surveillance by imagined audiences:

"If you continually post photos and you always do, it becomes a bit strange when maybe you no longer post photos, or you start to publish only photos of yourself. Like they would think ‘what happened, did they break up?'. You know?" [51]

In other words, posting couple pictures is also a way to avoid facing the social judgments of the audience. Users may struggle to balance and manage the different normative pressures that simultaneously require them to stop and continue sharing visuals. For this reason, it is considered advisable to limit the volume of couple pictures published on one's SNS profiles from the outset. [52]

6.2.5 Sensitivity in shared content

Among the visual content generally considered inappropriate for sharing on SNSs are images perceived as too intimate or sensitive. "There is a tacit agreement that if we go to the beach and I am wearing a thong, well, you do not take a photo and post it on SNSs," said Marika (female, 33 years old). This reasoning extends to all images that could harm the partner. "I would never share embarrassing images," explained Martin (male, 69 years old). "If the photo is simply of Gloria (his wife, female, 69 years old), then I will not pass it on to anyone else; I would not send it to anyone." [53]

Similarly, sharing family photographs where the couple is shown with children, especially young ones, is often considered unacceptable unless the identities of the minors are appropriately anonymized. Figure 3 shows an example of a photograph in which children are portrayed from behind. While the image does not represent a family picture, it serves as an illustration of a photograph suitable for sharing on SNSs. Marika commented:

"There has been a lot of talk about this problem [...] of these images being taken and used. [...] When in doubt, one should not publish. The photos I usually post do not clearly show the children; they are turned away or to the side."

Figure 3: Appropriate sharing of children on SNSs [54]

Such images are considered personal and should be kept private or shared only with individuals they trust, usually other close relationships, such as family members or close friends. These norms regarding the non-sharing of sensitive photographs usually arise from negotiations and discussions between the two partners. When one partner expresses certain concerns, the relational norm is explicitly established and will always precede the normative behavior of sharing one's personal life online demanded by SNS affordances. [55]

Norms advocating for withholding relationship visibility from SNSs do not necessarily regard only sensitive pictures. Specifically, the respondents believe that ideas of appropriateness and conventions can vary between different age groups, reflecting the distinct cultural, technological, and societal influences that each generation experiences. "Our generation is not so much about publishing our own couple pictures, as is done now," argued Lisandra (female, 58 years old). Certain respondents distanced themselves from what they describe as "pure exhibitionism" prevalent in perceived societal norms. By this, our participants do not mean that couple photos are unimportant to the relationship but simply that sharing them with an external audience is not considered appropriate. [56]

This sentiment is visually represented in Figure 4, which presents two contrasting images: On one side is Lisandra's Instagram profile, and on the other is a photograph of Lisandra and Walter together on horseback during a trip. The images from the SNS profile, anonymized to protect participants' privacy, include solo shots of Lisandra, travel and everyday life photos, and snapshots related to her work, with Walter never being depicted. In contrast, the couple photo on the right is stored in a digital album where the two partners collect all their couple photographs. They occasionally revisit these photos together, and during the interview, they expressed their intention to print them and create a physical photo album.

Figure 4: (In)appropriate sharing of couple pictures [57]

This critique, however, is tempered by an acknowledgment of the "evolution" of their perspectives on online sharing, recognizing that these might have been different in their youth. As Valentina explained,

"[n]owadays couple pictures are worth nothing, while when we were younger, I used to make the holiday album on Facebook, to publish photos. [...] Probably when you are young you spend a bit more time with the phone. Then you are no longer interested in the world seeing your photo, maybe you are more interested in keeping it for yourself, that's it." [58]

This reflection indicates a shift in priorities with age, impacting their perception of appropriate technology usage. Building on this perspective, some respondents reported that personal experiences, especially romantic ones that manifest in couple pictures, should be kept personal and shielded from the public eye of SNSs. This perspective is rooted in the belief that certain moments are sacred and should be preserved from external scrutiny or validation. This reflects concerns about the diminishing value of personal experiences when they are ubiquitously shared. [59]

Additionally, some respondents consider relationship visibility on SNSs an inappropriate practice due to risks associated with data security and control over images. They highlighted fears such as cyberbullying and loss of image control, pointing to broader apprehensions regarding networked photography. Despite the motivations behind the desire to not have couple pictures published on SNSs, when the viewpoints of the two partners are openly in disagreement, our respondents believe that the right to absence must always be guaranteed, thus adjusting the visual practices to the preferences of the partner who sets stricter boundaries. At the same time, any desire of the other partner to share more should be set aside to respect the personal autonomy of visual sharing, that is, the individual's decision-making freedom. In other words, the interviewees believe that it is necessary to consider the partner's expectations, renouncing a purely individual decision only when not doing so would be perceived as a harmful act toward the other. Overall, these concerns might suggest changing norms around privacy and sharing in the digital age, reflecting a cautious approach to online relational visibility. [60]

We investigated which injunctive norms govern relationship visibility on SNSs. Furthermore, we examined how romantic partners navigate norms arising from individual-focused SNS affordances and relational norms when visually communicating their relationship on these platforms. [61]

First, we revealed that the respondents perceive SNSs' imagined affordances (NAGY & NEFF, 2015) as "designed for and expect people to be individualistically minded" (JENKINS et al., 2015, p.29). This finding confirms that SNSs are viewed as platforms suitable for individual-focused use (BOYD, 2011), where individuals are encouraged to share information about themselves, their daily experiences, and personal interests (ROBERTS, 2014). Many studies focusing on the imagined affordance and the individualistic character of SNS were conducted approximately 10 years ago. It is noteworthy that even though SNSs have evolved significantly and integrated many new functionalities, the perceived individual character of SNSs persists. Second, the respondents described the SNSs' imagined audience and romantic partners as two separate reference groups. In their evaluations of appropriate practices, they distinguished which normative behaviors were perceived as appropriate for each reference group. These premises are essential for contextualizing the various norms of relationship visibility that emerged from our interviews. [62]

We identified several injunctive norms stemming from individual-focused SNS affordances. For example, the respondents considered it appropriate to limit the number of couple pictures shared or to share couple pictures promptly if they wanted to deter potential alternative partners. Furthermore, specific appropriate spaces for relationship visibility, tailored to certain stages of the relationship, emerged. Overall, the respondents reported that visual communication on SNSs should convey something that "their imagined audience would find interesting" (YAU & REICH, 2019, p.7). Thus, generally, when mentioning norms derived from SNS affordances, the participants considered the "imagined audience" (LITT, 2012, p.331) as an important reference group. [63]

However, our respondents expressed an ambiguous conception of the imagined audience, likely due to a lack of adequate reflection on the role of context collapse (MARWICK & BOYD, 2011). Consistent with LITT and HARGITTAI (2016), the respondents held a very abstract view of the audience, often referring to it generically as the entirety of their SNS contacts. [64]

In line with individual-focused SNS affordances, according to the respondents, relationship visibility on SNSs is an appropriate form of visual communication that revolves around the self. This finding resonates with the idea that relationship visibility is another facet of self-oriented information sharing (VANDERDRIFT et al., 2015, p.454). For the respondents, the individual focus extends beyond sharing selfies or self-portraits to include a wide range of visuals regarding personal experiences, from daily activities such as gym workouts to couple pictures portraying important life events such as first trips with a partner or weddings. This confirms that self-presentation can "take various forms, such as objects that signify personal interests or events that are part of the construction of personal memories" (SERAFINELLI, 2018, p.152). It also supports the findings of McLAUGHLIN and VITAK (2012), who showed that the overarching goal of SNS use is to present a comprehensive view of one's social life, and BARNARD (2016), who emphasized that the visual content shared on SNSs often pertains to personal daily experiences. However, BEVAN et al. (2015) suggested that important life events, such as marriage pictures, are often shared indirectly, leaving room for interpretation to avoid negative audience reactions. In contrast, the respondents in our study considered directly sharing these visuals appropriate, reflecting the belief that updates related to important life events are valued by their audiences. [65]

In our study, we went beyond confirming the presence of norms stemming from individual-focused SNS affordances. We also investigated the role of romantic relationships in relationship visibility on SNSs by exploring the presence of relational norms. The results clearly show that, although SNSs are considered individual-based platforms, relational norms exist and depend on implicit or explicit rules established within the relationship. Often, these norms are deemed even more important than those stemming from individual-based SNS affordances due to the greater significance associated with the reference group (romantic partners). Among the relational norms identified by the respondents are the need to share tie-signs in the early stages of a relationship, avoiding sharing couple pictures until both partners feel the relationship is adequately established, refraining from sharing overly sensitive or intimate photographs, and not sharing certain couple pictures to preserve the privacy of those involved or maintain a sense of uniqueness within the relationship. [66]

Overall, we confirmed that openly disclosing relationships on SNSs plays a functional role in relationship maintenance (STAFFORD & CANARY, 1991). The participants indicated that the choice to include relationship visibility in self-presentation practices was perceived as an appropriate act of relationship awareness (ACITELLI, 1993). In other words, it is an act through which the partner demonstrates "focusing attention on one's relationship [...] including attending to the couple or relationship as an entity" (ACITELLI, 2002, p.96). Translated to the SNS context, relational awareness can also mean being aware of how one's posts, comments, and likes around visual sharing might affect the relational partners and their relational expectations. Considering our results, we argue that relationship visibility is often perceived as a sign of care, confirming the result of ITO et al. (2021) on the importance of relationship visibility in generating relationship awareness and thus increasing relationship satisfaction. This also shows that relationship visibility is associated with a desire for connection and closeness (HUGHES et al., 2021). [67]

Apart from identifying several norms, we noted that sometimes the norms stemming from SNS affordances and relational norms collide, creating challenges for romantic partners in navigating and deciding which norms should take precedence. For instance, while posting couple pictures too soon is deemed inappropriate for the relationship, it is also considered necessary to ward off potential alternative partners. These two norms are per se not surprising. On the one hand, TARNUTZER (2023) found that there is optimal timing for relationship disclosures on SNSs linked to a certain level of intimacy to ensure positive reception from both the partner and the audience. Indeed, the initial public acknowledgment of a relationship on SNSs can be a critical rite of passage for its legitimization (ROBARDS & LINCOLN, 2016). On the other hand, relationship visibility is considered appropriate to convey relational assurance (COUNDOURIS, TYSON & HENRY, 2021), as it serves to communicate a commitment to maintaining a relationship. According to our results, this is particularly true for long-distance relationships and for protecting relationships from alternative partners. This confirms that relationship visibility serves to "communicate one's relationship quality and romantic unreceptiveness to others, they may discourage alternative partners from wanting to affiliate" (KRUEGER & FOREST, 2020, p.11). At the same time, our findings contrast with those of TURNER and PRINCE (2020), who argued that relationship visibility is not beneficial for romantic partners in long-distance relationships, and suggested that relationship maintenance is unrelated to online visual public sharing. [68]

In light of this, in our paper we highlighted that these norms can be conflicting, making it challenging for romantic partners to determine the most appropriate use of images on SNSs. In the case of conflict, researchers found that prioritizing relational norms might be more advisable, given the various risks and complexities associated with following audience-driven rather than partner-oriented relationship visibility (LUCCHESI & LOBINGER, 2024b; TURNER & PRINCE, 2020; ZHAO, SCHWANDA SOSIK & COSLEY, 2012). [69]

We found that norms stemming from SNS affordances dictate that the choice of what to share always lies with the profile owner. However, we also highlighted that when one partner believes that relationship visibility is inappropriate for privacy reasons, the other partner should set aside such norms to meet an implicit relational norm that satisfies the partner's expectations. This aligns with norms of relationship maintenance, which suggest that when mutual needs appear incompatible, partners should prioritize their partner's preferences over self-interest (VAN LANGE et al., 1997). Furthermore, this finding echoes a study by VENEMA and LOBINGER (2020, p.177), who found that people consider it appropriate to adapt to the preferences of the partner who sets stricter boundaries of visual sharing. In our results, this normative clash, in which partners believe it is necessary to prioritize relational norms over norms stemming from SNS affordances is also evident in the practice of reciprocal communication. Some respondents highlighted that reciprocal communication should be expected when visually sharing relationships online. In other words, if one partner frequently or intensely shares couple pictures, the other should do the same. This norm arises from the belief that the imagined audience might expect a balanced sharing of relational content within individual profiles. In previous studies, the authors reported that it is considered appropriate to reciprocate likes and comments on SNSs (YAU & REICH, 2019) and that reciprocal communication aids in maintaining stability and mitigating conflicts (BRYANT & MARMO, 2012). However, we found that in the case of relationship visibility on SNSs, the relational norm of respecting the partner's preferences regarding sharing and privacy should always be upheld, even if it sacrifices the norm of reciprocal communication. This sacrifice is not taken lightly because MUSCANELL et al. (2013) showed that a lack of relationship visibility on a partner's SNS profile can lead to negative emotions. [70]

In other cases, there is no actual discrepancy between norms referring to different reference groups but rather a complex intertwining. A striking example concerns when and where partners believe they should post the first couple picture on SNSs. The decision to opt for tie-signs in the early stages of the relationship and to reserve a specific space for couple pictures (e.g., ephemeral content) can be seen as two complementary strategies with one aim, i.e., the attempt to downplay the importance of the relationship, preventing it from being burdened with excessive meaning before it is formally acknowledged by both the partner and the audience. According to our participants, implicit tie-signs in visual content are an appropriate way to discreetly express affection. The social function behind tie-signs is not new, as LUCCHESI and LOBINGER (2024a) found that individuals use subtle visual cues to communicate affection within interpersonal communication. Furthermore, subtle references to shared experiences are considered appropriate and effective when conveyed through broader public sharing (ROBARDS & LINCOLN, 2016). Building on ROBARDS and LINCOLN's results, we also found that tie-signs are used to share "shadowed" content—information suggestive but not explicit about a romantic relationship. Tie-signs can serve as a delicate balancing act in visual sharing where even subtle relationship cues are carefully chosen to avoid explicit association with a romantic relationship, maintaining the desired level of privacy in a public setting. The inherently polysemic nature of visual communication which allows for multiple interpretations, makes it well suited for conveying tie-signs in this manner (e.g., HAND, 2012). [71]

Similar to the use of tie-signs, the selection of "spaces" for relationship visibility is crucial to achieve the same purpose. In previous studies, researchers reflected on the appropriateness of various SNS spaces with respect to the photographic styles of images. Similar to other authors (e.g., TIIDENBERG, 2020; YAU & REICH, 2019), we found that couple pictures should be aesthetically pleasing and avoid embarrassing or image-damaging content. Respecting these aesthetic standards is particularly important for content shared through permanent archiving features, such as Instagram feeds, where images become "mediated memories" (VAN DIJCK, 2007)—artifacts that construct a narrative of one's past, present, and future. In contrast, aesthetic standards are more flexible, or not required at all, when publishing couple pictures in ephemeral communication flows. This aligns with the role of features such as Instagram or Snapchat Stories as spaces for spontaneous, banal, and mundane sharing (KOFOED & LARSEN, 2016). However, we showed that this difference in appropriateness in the use of different spaces of online visibility also depends on the relationship stage, influencing whether couple pictures are better suited for ephemeral or permanent formats. Along similar lines, contrary to previous findings (e.g., BRODY et al., 2016; EMERY et al., 2014; PAPP et al., 2012; STEERS, ØVERUP, BRUNSON & ACITELLI, 2016; TOMA & CHOI, 2015), our respondents indicated that including couple pictures in profile pictures is often perceived as inappropriate. Overall, as SCHREIBER (2017) noted regarding visual communication on SNSs, these findings provide evidence that norms of relationship visibility are also strongly interconnected with the platforms' technical architecture, such as the distinction between permanent and ephemeral sharing features or the affordances tied to profile pictures and feed posts. [72]

In addition to reflecting on how norms stemming from individual-focused SNS affordances and relational norms can be seen as either conflicting or complementary, with this article we also contribute to advancing the understanding of the identified norms of relationship visibility. The respondents emphasized that oversharing couple pictures should be avoided when determining the appropriate amount of relationship visibility on SNSs. This finding aligns with previous research on visual communication in which participants cautioned against oversharing (McLAUGHLIN & VITAK, 2012). [73]

Relationship visibility should be carefully managed to avoid being perceived as redundant or inappropriate by the reference group. Furthermore, we found that older adults are more likely to consider sharing couple pictures on SNSs inappropriate. Although our study was not methodologically designed to compare different age groups, this finding warrants further investigation. This result aligns with previous research (KEZER, SEVI, CEMALCILAR & BARUH, 2016; STEIJN, 2014) highlighting that older generations disclose less information and are less motivated to use SNSs for self-presentation or self-disclosure practices. Additionally, we found that couple pictures are sometimes perceived as intimate, making their sharing on SNSs seem inappropriate. This idea aligns with the concepts of intimacy described by JAMIESON (1998) and ZELIZER (2009), who suggested that couple pictures are private and shared exclusively by the couple. This finding also supports VENEMA and LOBINGER's (2017) view that personal or intimate pictures should only be shared with trusted close relationships. However, we noticed that what is considered "intimate" does not necessarily depend on the visual motif. While a couple image might not be considered intimate based on its content, it can be understood as being intimate by the couple, for example, when referring to a personal or intimate experience or moment that should be kept private. In this case, the image might be understood as a memory object that recalls the moment and experience. Moreover, we underscored that some partners consider it inappropriate to share couple pictures online due to privacy concerns. This evaluation aligns with numerous studies in which researchers indicated that privacy concerns can reduce sharing activity on SNSs (e.g., CAIN & IMRE, 2022; YOUNG & QUAN-HAASE, 2013) and with authors who reported photo-sharing on SNSs being perceived as a risky behavior (e.g., LIVINGSTONE, 2008). [74]

Furthermore, sharing photos of one's children has become a widespread social norm on SNSs. Some authors used the term "sharenting" to denote a critical perspective on the use of children's images on SNSs (e.g., BLUM-ROSS & LIVINGSTONE, 2017), and found that sharing pictures with both partners and children is considered highly inappropriate (RANZINI, NEWLANDS & LUTZ, 2020). While researchers associated sharenting with the act of building a self-image as a parent (KUMAR & SCHOENEBECK, 2015), our respondents considered family pictures with children as part of their relationship visibility, suggesting that they see the family as an extension of their couple identity. In her work on emerging photo practices, AUTENRIETH (2018) identified different types of pictures, including "the child from behind" (p.227), whose sharing is considered a normative strategy. Our respondents confirmed that "photographing children from behind is a common anti-sharenting strategy to ensure they remain unrecognizable to unfamiliar viewers" (p.227), which is considered the most appropriate way to share couple pictures that include children on SNSs. [75]

In this article, we investigated the injunctive norms governing relationship visibility on SNSs and examined how romantic partners navigate the intersection between norms arising from individual-focused SNS affordances and relational norms. We revealed that SNSs are predominantly perceived as individual-centric platforms where romantic partners are expected to share personal experiences and self-oriented visual content. The respondents viewed relationship visibility as an extension of individual self-identity, aimed at satisfying imagined audience expectations. Consequently, partners believed that deciding whether and how to share couple pictures on SNSs should be an individual choice. However, we also showed that relationship visibility serves as a marker of commitment, care, intimacy, and relational awareness, contributing to relationship maintenance. [76]

When visually communicating their relationship on SNSs, romantic partners must navigate a complex spectrum of norms by balancing individual autonomy, relational expectations, and audience expectations. Partners are expected to adopt norms regarding the appropriate extent of visual cues to share, the appropriate timing for sharing couple pictures, the choice of SNS spaces for conveying relationship visibility, the volume of sharing, and norms and rules for sharing sensitive pictures while maintaining sufficient privacy in the relationship. While adhering to these norms, partners must consider both the affordances of SNSs and the context of their relationship. Consequently, partners often face conflicting norms, requiring them to balance behaviors that are appropriate for the relationship with those expected by the imagined audience of SNSs. Generally, when there is a clash between norms that regard different reference groups, individuals tend to prioritize relational norms over individual-focused approaches, especially when privacy concerns and the risks associated with online visual sharing are taken into consideration. This suggests a general intention to use SNSs in alignment with norms stemming from their affordances while demonstrating the capacity to prioritize relational norms in sensitive situations within the relationship. [77]

Our work has several limitations. First, the sample was based on a small and specific geographical area. In future research, authors should consider expanding the study to investigate the norms of visual communication and self-presentation in different cultural regions. Additionally, we did not examine the SNS profiles of our participants, which could have contextualized their perceived norms with actual usage practices. Researchers could adopt a mixed-methods design to deepen the understanding of the frequency of sharing couple pictures and visual tie-signs compared to self-related visual content on SNSs. This approach would also help determine the extent to which awareness of a norm results in SNS use that adheres to it. Moreover, as this article is part of a larger project on the norms and functions of visual communication, not all participants were very familiar with SNSs or used them regularly. This underscores the need for caution when making general claims that "everyone uses SNSs." The limited familiarity of some participants with SNSs likely influenced their evaluations and opinions about injunctive norms. In future studies, researchers could compare active SNS users with occasional or non-users. [78]

While for this paper we investigated injunctive norms governing relationship visibility on SNSs, we also found that awareness of a norm does not always result in adherence (STEIJN, 2016). Affordances are "functional and relational aspects which frame, while not determining, the possibilities for agentic action in relation to an object" (HUTCHBY, 2001, p.444). In future studies, researchers could compare the normative ideas reported by participants with their actual SNS usage through a longitudinal study. Another limitation is that the data were collected between September 2019 and July 2021. We must acknowledge that SNSs are platforms that continuously evolve, introducing new features and affordances (VAN DIJCK, POELL & DE WAAL, 2018). Consequently, the norms and behaviors we observed in our study may have shifted over time, even though similar findings were reported in studies conducted during SNSs' early years of popularity. For future research, authors should update the data to examine how recent changes in SNS functionalities affect relationship visibility and the navigation of norms. [79]