Volume 26, No. 3, Art. 10 – September 2025

Co-Creating Research Design: How to Achieve Participation in Social Studies Using Traditional Methods?

Ivanna Kyliushyk, Dominika Winogrodzka & Emil Chról

Abstract: While traditional methods such as focus group interviews (FGIs) and individual in-depth interviews (IDIs) are well-established in social research, their innovative use within participatory research remains underexplored. In this article, we address this gap by introducing a co-creation research design to combine qualitative data triangulation with a participatory approach. The study involved semi-structured IDIs with middle-class Ukrainian female forced migrants, preceded and followed by FGIs with Ukrainian women experts—practitioners with both professional and personal migration experience. The initial FGI supported the participatory development of the research topic and interview guide, ensuring relevance and ethical sensitivity. The final FGI allowed the same group of experts to interpret the IDIs' findings collaboratively and discuss their practical application. This co-creative process enabled mutual learning between researchers and community actors and increased the ethical accountability and analytical depth of the study. We discuss both the potential and limitations of this approach and argue that traditional qualitative methods, when combined with participatory elements, can significantly enhance co-production of knowledge and the impact of social research. We contribute to research methodology development and encourage further adaptation of participatory strategies in qualitative inquiry by offering practical insights into the design and implementation of this method.

Key words: qualitative methods; focus group interviews; individual in-depth interviews; participatory methods; data triangulation; knowledge co-production; Ukrainian forced migration

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. Toward Participatory Research

3. Using Traditional Research Methods to Enhance Research Participation

4. The Co-Creation Research Design: Individual In-Depth Interviews Preceded and Ended With a Focus Group Interview

5. The Co-Creation Research Design: The Possibilities of Using Focus Group Interviews as Participatory Tools in Social Studies

5.1 The benefits of FGI preceding the IDIs phase

5.2 The opportunities of using FGI for concluding the IDIs phase

5.3 What challenges does the use of the co-creation research design entail?

6. Conclusion

The participatory approaches are increasingly being utilized in social research (BERGOLD & THOMAS, 2012; HACKER, 2013; McINTYRE, 2008; VAUGHN & JACQUEZ, 2020), including migration and refugee studies (BLACHNICKA-CIACEK, WINOGRODZKA & TRĄBKA, 2024; MATA-CODESAL, KLOETZER & MAIZTEGUI-OÑATE, 2020; NIENABER, OLIVEIRA & ALBERT, 2023; PINCOCK & BAKUNZI, 2021). To enhance participation in research projects, new methods (e.g., visual and art-based methods or peer research approaches) are being developed (see e.g., BAKUNZI, 2018; GILODI, RYAN & AYDAR, 2025; MORALLI, 2024; NIENABER & KRISZAN, 2023; NIKIELSKA-SEKULA & DESILLE, 2021; PIETRUSIŃSKA, WINOGRODZKA & TRĄBKA, 2023). However, attempts to integrate such an inclusive approach into traditional qualitative methods such as focus group interviews (FGIs) and individual in-depth interviews (IDIs), are less frequently undertaken (VAUGHN & JACQUEZ, 2020). [1]

We aim to provide a comprehensive understanding of the opportunities and challenges involved in integrating participatory elements into traditional qualitative research methods by bracketing the main phase of the study—IDIs—with two FGIs: One preceding and one following the individual interviews. The purpose of the first group discussion was to collaboratively develop the research topic and interview guide together with members of the group whose situation was the focus of the study, ensuring both relevance and ethical sensitivity. The second FGI, conducted with the same group, served to collectively interpret the IDIs' findings and reflect on their potential practical application. By examining this co-creation research design, we seek to elucidate the practical implications for each side of the study process—participants, researchers, and the overall impact on the quality and ethics of the data collection and analysis. Our goal is to generate insights into its applicability and effectiveness in addressing research objectives. Ultimately, we strive to encourage researchers to adopt this methodological approach in their own studies and to inspire creativity in developing innovative ways to incorporate participatory elements into traditional social research methods. [2]

At the beginning of this article, the theoretical framework of participatory research (Section 2) and different ways of using FGIs over time are introduced (Section 3). In Section 4, we outline the idea of our co-creation research design, which involves preceding and concluding IDIs with FGI. In the final Section 5, the opportunities and challenges associated with this research approach are analyzed. [3]

2. Toward Participatory Research

Since the mid-twentieth century, extensive social changes have propelled initiatives aimed at attaining social equality. Correspondingly, in the field of social research, there has been an increased emphasis on ethical considerations, especially regarding the power relations between researchers and study participants (BROWN, 2021) and the processes of knowledge production (ENRIA, 2016). As a result, participatory approaches (BERGOLD & THOMAS, 2012; HACKER, 2013; McINTYRE, 2008; VAUGHN & JACQUEZ, 2020) have been developed as a "method that enhances the power of individuals and communities through their inclusion as partners in research" (MILLAR, VOLONTERIO, CABRAL, PEŠA & LEVICK-PARKIN, 2024, p.479). The fact that the concept of inclusive studies has gained popularity has been described by NIND (2017) as a "transformation away from research on people to research with them," meaning that the aim now is to involve participants in the design and conducting of research, to represent and value their lived experience as way of knowing (p.278) instead of treating them merely as data sources (MILLAR et al., 2024). [4]

Participatory research, with its different varieties such as participatory action research (CORDEIRO, SOARES & RITTENMEYER, 2017) and community-based participatory research (DUEA, ZIMMERMAN, VAUGHN, DIAS & HARRIS, 2022) has been widely used among groups vulnerable to various forms of exclusion, e.g., children and youth (LUSHEY & MUNRO, 2015), individuals experiencing mental health challenges (CALABRIA & BAILEY, 2021), people with disabilities (GOEKE & KUBANSKI, 2012), or women (AZIZ, SHAMS & KHAN, 2011). These approaches are gaining recognition also in migration and refugee studies (MATA-CODESAL et al., 2020; NIENABER et al., 2023), due to their "engaged and inclusive nature," which provides more contextual and localized insights, leading to a comprehension of social dynamics (CORDEIRO et al., 2017, p.397). Participatory research in migration and refugee studies includes such methods as peer research approach (BAKUNZI, 2018; GILODI et al., 2025), visual methods (MORALLI, 2024; NIKIELSKA-SEKULA & DESILLE, 2021) and art-based methods (PIETRUSIŃSKA et al., 2023) such as photo-voice (CUBERO, MILDENBERGER & GARRIDO, 2024) or LEGO® Serious Play® (NIENABER & KRISZAN, 2023). The idea behind such methods is to allow participants to share information using means of expression that are relevant to them. One of the key aspects of these methods is their "hands-on" nature, which empowers people to generate information and share knowledge on their own terms (KINDON, PAIN & KESBY, 2007). [5]

Participatory methods, especially visual, creative, and co-creation approaches, are rarely used in traditional qualitative research. Engaging with such methodologies, including studies involving migrants and refugees, presents numerous challenges, spanning methodological, ethical and practical dimensions (BLACHNICKA-CIACEK et al., 2024; DAVID, 2002; KILPATRICK, McCARTAN, McALISTER & McKEOWN, 2007; MATA-CODESAL et al., 2020; PINCOCK & BAKUNZI, 2021), particularly within the context of neoliberal academia (KINT, DUPPEN, VANDERMEERSCHE, SMETCOREN & DE DONDER, 2024; MALONE, 2020; MILLAR et al., 2024). TOKOLA, RÄTTILÄ, HONKATUKIA, MUBEEN and SILLANPÄÄ (2023) suggested that such studies are time-consuming, costly, and energy-intensive, and their value is often romanticized. Social researchers may feel discouraged from implementing these methods—either as stand-alone approaches or as complementary to traditional methodologies—as they require additional effort, specific knowledge, and, often, skills. [6]

3. Using Traditional Research Methods to Enhance Research Participation

New methods and techniques are frequently sought in participatory research to achieve the intended scientific, ethical and social goals (VAUGHN & JACQUEZ, 2020). However, there are fewer examples where conventional research methods are refreshed and utilized in a creative and collaborative manner to achieve more inclusiveness in social studies. Thus, in this article, we present how the FGIs—a traditional method used in social research—can be leveraged to amplify participatory aspects. [7]

Individual interviews and group discussions are considered fundamental qualitative methods and are among the most frequently used (MAISON, 2022). In general, the objective of FGIs is to identify the perceptions, thoughts, and impressions of a selected group of individuals regarding a specific research issue (KAIRUZ, CRUMP & O'BRIEN, 2007). An FGI is conducted as a group interview that is loosely centered on the research topic (GAWLIK, 2012). Open-ended questions, limited in number, are posed to elicit views and opinions from the participants (CRESWELL, 2009). The selection of interviewees is guided by a certain homogeneity among them (HYDEN & BULOW, 2003; MORGAN, 1996). Each group comprises six to eight people (CRESWELL, 2009). Researchers—FGI's moderators—play an important and active role in facilitating group discussion and collecting data (MORGAN, 1996). Their role is not merely to guide the conversation but also to navigate the complex dynamics of group interactions. Effective moderation involves balancing the power relations within the group, ensuring that all voices are heard while preventing dominant participants from overshadowing others. The group situation acts as a strong stimulus for the interviewees. The primary goal of this method is to leverage the interactional data that emerge from the discussion among interlocutors (e.g., asking each other questions, commenting on others' experiences) to deepen the investigation and reveal aspects of the phenomenon that would otherwise be less accessible (DUGGLEBY, 2005). [8]

An essential advantage of FGIs lies in the group setting, which serves as a potent stimulus for the interviewees. It can be observed that participants in FGIs assume various roles, including initiators, who introduce new topics and help maintain the dynamism of the discussion, and regulators, who sustain the flow of the conversation (GAWLIK, 2012). The benefits of FGIs are manifold: Firstly, they enhance the engagement of those involved in the research; secondly, they provide a sense of security and help to break down barriers, thereby facilitating communication; thirdly, the responses of some speakers inspire others to contribute their own answers. Through confrontation, FGIs elicit insights that might otherwise remain unspoken or forgotten. At the same time, a notable challenge lies in the fact that participants' statements are not individualized but are instead influenced by group dynamics. Within IDIs, interviewees might respond differently. This phenomenon, termed by GAWLIK (p.134) as the "crystallization of opinions," entails the flattening and homogenization of voices. [9]

FGIs play a versatile role in research methodology, serving both as a preliminary and supplementary tool when used in conjunction with quantitative methods. Group discussions are frequently employed to refine survey instruments, gather initial qualitative insights, and complement quantitative findings. For instance, they are often used to construct questionnaires or to enhance results with direct quotations and interpretative depth. Alternatively, FGIs can also function as the primary research method, with surveys supporting sample selection or providing information on the prevalence of issues identified in the focus group (MORGAN, 1996). To date, FGIs have been employed to deepen quantitative research and explore topics. They can serve as an exploratory phase before quantitative research, study the formation of opinions within a group context, and facilitate creative processes (GAWLIK, 2012). [10]

Although FGIs are most commonly utilized as a preliminary stage in survey research (NASSAR-McMILLAN & BORDERS, 2002), we focus more on the combination of group discussions with individual interviews, as qualitative research methods. This combination is used to achieve greater depth in IDIs and a broader scope in FGIs (CRABTREE, YANOSHIK, MILLER & O'CONNOR, 1993). FGIs are often used to supplement IDIs to verify conclusions drawn from their findings and to extend the population covered by the research. The advantage of this strategy is that it allows for obtaining responses from a relatively wide group of participants in a relatively short period of time (MORGAN, 1996). Furthermore, it helps in exploring specific opinions and experiences in greater detail, as well as creating narratives relating to the continuity of personal experiences over time (DUNCAN & MORGAN, 1994). The advantage lies in first identifying the range of experiences and perspectives and then drawing on this pool to add more depth where needed (MORGAN, 1996). Some authors first obtain data from individual interviews and subsequently conduct focus groups to confirm the results (e.g., PLACK, 2006). Others initially conduct FGIs and later verify these results with data from IDIs (e.g., DICK & FRAZIER, 2006). [11]

Despite their widespread application in qualitative research (MAISON, 2022), focus groups are rarely used to enhance the participatory nature of social research. This is because the most common participatory research methods rely on dialogue, storytelling, and collective action (KINDON et al., 2007). Traditional FGIs frequently operate at the "consult" level of participation, where stakeholders offer feedback that researchers consider when making their study decisions (VAUGHN & JACQUEZ, 2020). This approach ensures that stakeholders' perspectives are included but does not fully integrate them into the core research activities, maintaining a more hierarchical relationship between researchers and participants. However, more traditional research methods can be adapted to take a more participatory approach. For example, "focus groups can be co-designed, co-facilitated, and collaboratively analyzed by community co-investigators" (p.7). By integrating co-researchers throughout these stages, the research process becomes a shared endeavor, fostering a sense of ownership and empowerment among participants. [12]

In this article, we present the co-creation research design as an attempt to rethink the use of traditional research methods in a participatory manner. Building on the understanding of participatory approach as a shift from research "on people to doing research with them" (NIND, 2017, p.278; MILLAR et al., 2024), we aim to elevate FGIs from the "consult" level to at least the "collaborate" level (VAUGHN & JACQUEZ, 2020, p.6; see also CALL-CUMMINGS & ROSS, 2022). In doing so, we aim to transform the dynamic between researchers and participants, promoting a more equitable and inclusive research process. This is based on the principle of reciprocity (NIND, 2017) and other ethical rules important to a participatory social approach. These include trust, partnership, power balance, respect, valuing experiential knowledge, empowerment, equity, and social justice (KINT et al., 2024; PIETRUSIŃSKA et al., 2023; VON UNGER, 2021). [13]

4. The Co-Creation Research Design: Individual In-Depth Interviews Preceded and Ended With a Focus Group Interview

The current article is based on research experience gathered for the qualitative component of the BigMig: Digital and Non-Digital Traces of Migrants in Big and Small Data Approaches to Human Capacities project. The study was conducted in strict adherence to ethical standards for migration studies (CLARK-KAZAK, 2021), and was approved by the Research Ethics Committee at the implementing institution. [14]

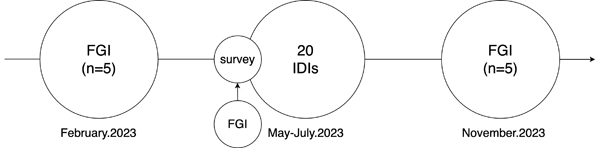

The core of our qualitative research comprised 20 in-depth, semi-structured individual interviews with Ukrainian women who are forced migrants, conducted from May to August 2023. These interviews were preceded and followed by an FGI involving five Ukrainian women experts with extensive experience in supporting migrants in Poland, and who also had experience of migration. The initial focus group took place in February 2023, exactly one year after the escalation of the Russian war in Ukraine, and the concluding FGI was organized in November 2023. Before engaging in the interviews, all participants completed a questionnaire about their situations and resources as part of the quantitative research component of the project. After completing the questionnaire conducted by the MyMigration.Academy website, participants were provided with individual summaries detailing the resources they had. The questionnaire design and feedback provided to respondents were evaluated during a separate focus group consisting of individuals with migration experience, ensuring that our research tools were sensitive to their backgrounds and current circumstances (Figure 1). Here, we focus particularly on the qualitative component of the study—individual in-depth interviews preceded and followed by a focus group interview—which we called the co-creation research design.

Figure 1: Qualitative research design in the BigMig project [15]

The IDIs phase aimed to explore how Ukrainian migrants mobilize various resources—human, psychological, social, economic and legal capital—and transform them into mobility capital (KYLIUSHYK, WINOGRODZKA & CHRÓL, 2025; WINOGRODZKA, KYLIUSHYK & CHRÓL, 2025). The participants of this stage of the study—well-educated middle-aged women (31-54 years old)—were forced to flee their homes due to the escalation of the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022, subsequently relocating to Warsaw, Poland. For almost all of the women, it was their only experience of migration from Ukraine, where they had led fulfilling social and professional lives in cities such as Lviv, Kyiv, Kharkiv, Mariupol and Chernihiv. In terms of their socio-economic situation, all of the interviewees can be classified as representative of the Ukrainian middle class, which distinguishes them from individuals in previous waves of migration from Ukraine (GÓRNY & KACZMARCZYK, 2023; KYLIUSHYK & CHRÓL, 2025). Regarding their family situations, the majority were married and had children, whom they had brought with them to Poland. [16]

The large scale of female forced migration from Ukraine to Poland (DUSZCZYK, GÓRNY, KACZMARCZYK & KUBISIAK, 2023; GÓRNY & KACZMARCZYK, 2023) created a previously unknown, new socio-political context and, consequently, a new research area. As responsible, reflective, and ethical migration researchers, we tried to prepare as best as we could, also through an appropriate qualitative research design. Therefore, we decided to precede and conclude the individual in-depth interviews with forced migrants from Ukraine with a focus group discussion involving female experts aged 32-47 who had personal experience of migrating from Ukraine to Poland, and who had worked with migrants for between one and 10 years. This included people who left Ukraine as a result of the escalation of the Russian war in 2022. Due to practitioners' previous experience, they had been creating support infrastructures in Poland for those seeking refuge. The participants of both FGIs were employed in NGOs and community organizations as coordinators of consultation points, cultural initiatives, and aid projects. Their expertise covered areas such as legal counseling, social and psychological support for women and children, cultural integration, and community organizing. Their dual role—as both migrants and professionals—provided a valuable perspective on the needs and challenges faced by Ukrainian forced migrants in Poland. Practitioners' socio-demographic profile and expertise made their invitation to participate and partially co-create the study very important to the research process. Given their many years of work in the field of migration, we refer to them in this article as experts on Ukrainian migration to Poland and adaptation in the host country. At the same time, we would like to emphasize that all participants in the qualitative study (both IDIs and FGIs) were regarded as experts, as they contributed valuable experiential knowledge to the research project. [17]

Within the co-creation research design, the first FGI, preceding the IDIs phase, focused on a comprehensive discussion about the research topic and an evaluation of the interview scenario. The meeting consisted of three main parts. In the introductory section, we provided an overview of the project framework and dedicated time for mutual acquaintances. We got to know the participants—on one hand, as Ukrainian migrants with details about their migration journeys, and on the other hand, as experts with their expertise and professional fields. The second part of the meeting was dedicated to a detailed discussion of the research topic and the thematic scope of the IDI scenario. During this part, the experts also answered questions formulated in the scenario, sharing both their professional knowledge and personal experiences. The third part of the meeting addressed practical issues—the construction of the scenario, the wording of the questions, and the language used in the research tool. All substantive comments from the FGIs participants—whether methodological, practical, or ethical—regarding the conduct of research with forced migrants were incorporated into the IDIs stage. [18]

Next, we carried out a phase of IDIs. All individual interviews, like the focus groups, were conducted in the participants' native language by Ivanna KYLIUSHYK, a Ukrainian researcher with experience of working in NGOs supporting migrants in Poland. Her professional and social experience fostered openness and facilitated thorough data collection. Before taking part in the study, all individuals were thoroughly briefed on the purpose of the project and the intended use of the data collected. With their prior consent, all interviews were recorded and transcribed, and detailed participant information was anonymized to ensure confidentiality while maintaining data authenticity. Emil CHRÓL translated the transcripts into Polish to provide access to the research material for the entire research team. Dominika WINOGRODZKA coded the collected data using MAXQDA (KUCKARTZ & RÄDIKER, 2019), in line with the project's theoretical framework and themes emerging from the interviews. [19]

The preliminary data analysis was crucial for preparing the second focus group, which aimed to present the study findings and engage the same experts in participatory data interpretation, thus concluding the qualitative study. Regarding the structure of the second FGI, we prepared a presentation outlining the preliminary results of qualitative data analysis. The presentation was divided into three parts, corresponding to the thematic blocks of questions included in the individual interview scenario. In addition to the main findings, it featured illustrative quotes to provide a deeper understanding of the data. The discussion moderator presented slides on each specific thematic area and then asked the experts for their interpretations and opinions, requesting further input to enhance the information gathered. The interviewees' extended stay in Poland allowed them to provide insights into the study results, considering the structural changes that have occurred in the country in recent years. The deliberate selection of participants ensured that the information we gathered was informed by both personal and professional experiences. [20]

Regarding additional organizational aspects related to conducting qualitative research, we would like to add that all interviewees, both for the IDIs and FGIs, had very tight schedules and limited free time. Therefore, we decided that, as a token of appreciation for their time, all participants would receive a cash voucher for use in online shopping. Regarding the location, individual interviews were always conducted at places chosen by the interlocutors that they deemed comfortable for the conversation (such as their workplace, the vicinity of their residence, or a café). For the focus groups, the first meeting was held at the headquarters of one of the largest Ukrainian organizations in Warsaw, a location familiar to the participants where they felt at ease. The second FGI took place at a university, which reinforced the sense of collaboration and emphasized the role of Ukrainian migrants as experts representing non-governmental organizations in academic research. [21]

5. The Co-Creation Research Design: The Possibilities of Using Focus Group Interviews as Participatory Tools in Social Studies

Below, we present our critical observations regarding the potential and challenges associated with our co-creation research design. This section is divided into three parts: First, we explore the advantages of using group interviews prior to the individual interviews phase; next, we examine the potential benefits of leveraging FGI to finalize the IDIs stage, and finally, we discuss the challenges inherent in implementing this research approach. [22]

5.1 The benefits of FGI preceding the IDIs phase

Conducting a group discussion with experts helped us prepare for the main phase of the study: Conducting individual interviews. The primary goal of this initial discussion was to evaluate the IDI's scenario (CALABRIA & BAILEY, 2021). This allowed us to customize the research tool to fit the specific needs of the group participating in the project—forced migrants from Ukraine. During collective consideration, the participants assessed the design of the scenario, identifying effective questions as well as areas for improvement. During the first FGI, the interviewees also contributed to improving the formulation of the questions. This helped to avoid overly complex or unintelligible concepts, as well as general or narrow wording. In doing so, we paid attention to the potential differences in linguistic habitus between researchers and participants (BOURDIEU, 1991 [1982]). We recognized that such differences could influence communication and interlocutors' comfort levels. Therefore, we deliberately adapted the language of our study to foster trust and mutual understanding. [23]

The first group discussion allowed us to gain a deeper understanding of the context in which the project was carried out, as well as the situation of the group involved in the research (CORDEIRO et al., 2017). This process helped us better identify key issues to address and adapt the scenario to the specific characteristics of the participants. During the discussions, we gained a more nuanced understanding of the various contextual situations of Ukrainian women in Poland, which was important both for the implementation of the interviews and for a publication based on the results obtained. [24]

Involving Ukrainian experts in the initial phase of preparing for individual interviews had significant ethical implications. This consideration is particularly crucial in participatory research involving individuals at risk of social exclusion or people experiencing vulnerable situations (see e.g., AZIZ et al., 2011; CALABRIA & BAILEY, 2021; LUSHEY & MUNRO, 2015), including migrants and refugees (MATA-CODESAL et al., 2020; NIENABER et al., 2023) such as Ukrainian women who were forced to migrate due to the escalation of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Consequently, conducting a preliminary group discussion with migrant experts was essential to minimize the risk of re-traumatizing these women through inappropriate or distressing questions, thereby enhancing the ethical standards of the study (CLARK-KAZAK, 2021). For this reason, which was also in line with the experts' opinion, we deliberately avoided asking direct questions about interviewees' experiences of forced migration during individual interviews. However, when women chose to speak about it themselves, we created a safe space for them to share their stories, listening attentively and respectfully. While some migrants did not raise this topic at all, others chose to share their difficult experiences with us, expressing a need for their stories to be heard. Additionally, the IDI study participants had the opportunity to choose the language in which the interview would be conducted (Ukrainian or Russian). This choice acknowledged the linguistic diversity within Ukraine, where Russian has historically been spoken by a significant portion of the population, particularly in the eastern and southern regions. For many Ukrainian women, especially those from these areas, Russian remains their primary language of daily communication, regardless of political stance. Given the context of Russia's aggression against Ukraine, sensitivity around language use was especially important; allowing participants to communicate in their preferred language fostered trust and mutual understanding, and ensured that the study was conducted with heightened sensitivity and respect for the interviewees' needs. [25]

Conducting the FGI prior to the main phase of the inquiry introduced another important ethical dimension. It enabled participants to actively engage in the project's design, express their lived experience and perspectives, and influence the study objectives and tools, thereby increasing the inclusiveness of the research process (NIND, 2017). This participatory approach not only enhanced the study's reliability but also ensured that it was more closely aligned with the actual needs and situations of forced migrants. By incorporating the perspectives and experiences of experts, the individual interviews yielded deeper and more relevant results. Consequently, we assert that a preliminary group discussion with migrant experts can provide valuable insights that researchers, particularly those who are not part of the community being invited to participate in the study, may overlook. Furthermore, in our project's case, involving experts in the research process provided them with the opportunity to influence the study's design (VAUGHN & JACQUEZ, 2020). This helped to reduce the risk of instrumentalization of participants and built their confidence in our research team and project, which in turn contributed to minimizing asymmetry in the participant-researcher relationship (BROWN, 2021; ENRIA, 2016). [26]

The instrumentalization of interviewees—meaning treating them merely as data sources—even within participatory research frameworks, was a growing concern among researchers (MILLAR et al., 2024). The authors emphasized that a participatory approach, when implemented without "ethical reflexivity" (VON UNGER, 2021, p.189) may achieve only partial effectiveness and can be tokenistic (PIETRUSIŃSKA et al., 2023). Ethical reflexivity involves approaching the research process as one with potential social and political consequences for all parties involved (VON UNGER, 2021). It entails conducting research in a manner that minimizes harm, protects participants' rights, and upholds accountability to both ethical standards and scientific aims. The notion of ethical reflexivity can be considered across three dimensions: 1. Anticipating potential ethical challenges in advance; 2. engaging in "ethics in practice" (GUILLEMIN & GILLAM, 2004, p.264) which involves attending to ethical issues as they arise throughout the research process, and 3. reflecting on the broader role of social science research in society, including current inequalities. Without deep and critical consideration of ethical practices, the participatory methods employed may merely serve as superficial gestures. Consequently, such an approach can undermine the potential for meaningful participation and social justice. [27]

Experts who participated in our study highlighted that researchers often sought help from their community organizations to find interviewees, but they rarely asked for their expertise in conceptualizing the study or developing research tools. We assert that the co-creation research design that we implemented provided participants with a sense of agency and an awareness of their impact on the project. Additionally, it enabled them to ensure that the study's quality aligns with their expertise and values. Therefore, they positively evaluated our qualitative research design for its participatory qualities. Moreover, participation in the initial focus group created a space for the FGI interviewees to reflect on refugee migration from Ukraine to Poland and to exchange thoughts with one another. As they told us at the beginning of the post-FGI conversation, participation gave them a chance to reflect on a topic present in their everyday lives—one they had neither previously noticed nor had time to consider, being immersed in the process and practical issue rather than observing it from the outside, taking into account the broader social context. [28]

The FGI also provided an excellent opportunity to inform the community about the planned study and its objectives (VAUGHN & JACQUEZ, 2020). This was important not only for disseminating information about the ongoing project but above all, for building trust and commitment among participants. Our transparency and openness in communication about the aims and objectives of the study helped interlocutors feel more informed about the project. This increased their willingness to cooperate and participate in the study (see also BLACHNICKA-CIACEK et al., 2024). We prepared condensed information about our project, which we provided to the women before inviting them to the focus group discussion. Additionally, at the beginning of the FGI, we presented our project and its main objectives. [29]

In addition to the ethical dimension, the implementation of the co-creation research design can offer practical opportunities. Experts can play an important role in identifying potential interviewees for individual interviews, particularly when hard-to-reach groups should be involved. In our case, the participants of the FGIs supported us in making contacts. This not only enabled us to reach Ukrainian women and obtain unique information but also allowed us to successfully implement the study within the planned timeframe. [30]

The FGI with experts that preceded the IDIs also served to gather knowledge that was crucial to the purpose of the study. Thus, it contributed to obtaining preliminary data on how forced Ukrainian migrants mobilize various resources—human, psychological, social, economic and legal capital—and transform them into mobility capital (WINOGRODZKA et al., 2025). This material was included in the overall analysis of the data collected during the study. It was also important when preparing a scientific article (KYLIUSHYK et al., 2025) on the multi-level factors impacting mobility capital formation among Ukrainian forced migrants in Poland. [31]

5.2 The opportunities of using FGI for concluding the IDIs phase

Conducting a follow-up group discussion with the same interviewees after completing the IDIs provided additional opportunities to enrich the research process. First, it allowed us to share the information gathered with the project participants. During the second focus session, we presented the findings from the main phase of the study. This session enabled us to reconvene with the experts, offering them insights they needed to better tailor their support to the group's needs (MILLAR et al., 2024). Additionally, presenting our research results provided an opportunity to compare them with the practical knowledge and experiences of the experts. [32]

Participants of the FGIs shared the observation that researchers seldom reached out to them at the stage of disseminating research findings, missing an opportunity to engage communities in interpreting results and ensuring that the knowledge produced was relevant and accessible to those it concerned the most. The experts willingly referred to the presented results from the IDI phase. They positively evaluated our presentation and the research findings, thereby enhancing their credibility and reliability. A key objective of the second group discussion was to supplement and collaboratively interpret the data. Involving experts in this part of the research process fostered a participatory co-creation of knowledge (NIND, 2017). This approach enabled us to draw more comprehensive and practical conclusions from our study. By soliciting practitioners' opinions on any gaps in the information, we significantly enriched the data, facilitating deeper interpretations. [33]

First, this research approach, which included data triangulation—in-depth individual interviews alongside focus group interviews and a participatory approach—allowed us to study the process of Ukrainian women mobilizing various resources and converting them into mobility capital in a comprehensive manner. While the IDIs provided us with extensive information about the factors that favor or hinder the formation of mobility capital at micro and meso levels, the participants in the FGIs, thanks to their expertise, completed the picture by identifying factors occurring at the macro level. These findings are discussed in more detail in another article that we have co-authored (KYLIUSHYK et al., 2025). [34]

Second, thanks to an FGI conducted at the conclusion of the IDIs phase, we were able to examine certain migration-related mechanisms over time, since migration from Ukraine to Poland is a dynamic process. (CHRÓL & KYLIUSHYK, 2025; GÓRNY & KACZMARCZYK, 2023; KYLIUSHYK & CHRÓL, 2025). During the second group discussion, the experts complemented the data with information on how the situation of Ukrainian migrants in Poland looked before February 24, 2022, how it looked one year after the escalation of the war, and the changes that have occurred over the past two years. In this way, we were able to capture the changing context and analyze how it affects the individual lives of female migrants in Poland. Moreover, the FGI participants combined their expert knowledge—acquired through work in NGOs supporting migrants and refugees—with their lived experiences, and compared the situation at the moment of the final focus session to what they had encountered when they first arrived in Poland. [35]

The ending FGI can provide a platform for discussing potential recommendations, which is crucial for the preparation of a policy brief after the completion of the study (see e.g., FEDYUK et al., 2024). This can have an empowering effect on participants and more broadly, on the community involved in the study (MILLAR et al., 2024; VAUGHN & JACQUEZ, 2020). Experts can offer valuable insights into the practical implications of the findings and suggest specific actions to address the identified issues. Such collaboration can develop realistic, implementable recommendations that address the actual needs of the group involved in the project. [36]

We believe that involving experts in data analysis and recommendation formulation can increase the overall engagement of the community in the study. As representatives of their group, experts can more effectively communicate findings and recommendations in a clear and acceptable manner to the community. This can enhance the likelihood of implementing recommendations and sustaining research activities in the future. Altogether, this can strengthen the potential for using FGIs in participatory research not only at the "consult" level but also at the higher "collaborate" level (VAUGHN & JACQUEZ, 2020, p.6; see also CALL-CUMMINGS & ROSS, 2022). By building collaborative and reciprocal relationships, all participants can derive mutual benefits from the research. [37]

Finally, employing such a qualitative research design, with its participatory elements, can make the relationship between researchers and participants more equitable by amplifying participants' voices and thus minimizing the power imbalances present in traditional research methods (BROWN, 2021; PIETRUSIŃSKA et al., 2023). Such approaches aim to dismantle the hierarchy in knowledge production, enabling non-hierarchical processes of knowledge generation (ENRIA, 2016; NIND, 2017). The co-creation research design can build trust and a sense of community, which consequently could lead to more open and constructive future collaborations extending beyond academic projects. Overall, this approach can strengthen cooperation between the NGO sector, which was represented by the FGIs participants, and academia, enhancing the practical value of the research results and potentially contributing to tangible social change and the improvement of specific group situations. [38]

The researcher's position also played an important role in the research process. In our study, Ivanna KYLIUSHYK acted in two roles: Firstly, as an experienced researcher and an expert on Ukrainian migration who had worked for many years in Polish NGOs supporting migrants; and secondly, as an Ukrainian migrant herself. Thus, her perspective in the study was that of an "insider" who partially shared her lived experience with the research participants (PUSTULKA, BELL & TRĄBKA, 2019). This dual position resulted in many opportunities to build relationships both with migrant experts and with those in vulnerable situations such as forced migrants. This allowed both FGIs and IDIs to be conducted in the language of the participants, which enabled greater openness and trust, and therefore, the ability to collect high-quality data. [39]

5.3 What challenges does the use of the co-creation research design entail?

Despite recognizing the numerous advantages offered by the proposed co-creation research design, we also want to highlight its risks and challenges, which must be considered during the planning and execution of the study. [40]

First of all, it is important to note that group discussions themselves have many limitations, as is well-documented in literature (e.g., GAWLIK, 2012). In addition to the challenges specific to the group interview technique, one of the primary difficulties with our methodological approach is the significantly increased workload for the research team. Organizing, coordinating, and conducting two FGIs—one before and one after the IDIs—required additional commitment to the study's implementation. We had to invest more time in preparing the first focus group, analyzing its results, making changes in the scenario of the interviews, and then reconvening with participants after completing the individual interviews. Before the second FGI, it was necessary to analyze the data from the IDIs phase, prepare a presentation for the experts, and plan the structure of the meeting. Each focus group lasted approximately three hours, including a break. After each session, we produced anonymized transcripts and detailed notes. This process was considerably more time-consuming than conducting only individual interviews, which extended the study's implementation time. [41]

Participatory research is often not only more time-consuming but also more costly than traditional research (PIETRUSIŃSKA et al., 2023). Organizing and conducting additional FGIs generated extra logistical expenses and the need for participant incentives. Although we had access to a free venue, in other cases, this might involve additional costs for renting meeting spaces and paying moderators. All these expenses must be adequately accounted for in the project budget during the planning stage, which can pose a financial challenge, especially when resources are limited. [42]

A crucial challenge for us was maintaining participant engagement throughout the entire research process. This required not only effective communication but also the building of trust and motivation among FGI interviewees to remain active and engaged at every stage of the study (BLACHNICKA-CIACEK et al., 2024). Lack of engagement can lead to participant dropout, necessitating the recruitment and onboarding of new participants, which can also impact the quality of the collected data. It was important to us that the same practitioners participated in both focus groups, and we achieved this successfully. We wanted them to be involved throughout the study. As these experts were already familiar with the specifics of our research, they were embedded in its context, having co-created it from the outset. We wanted to share the results of the IDIs with them so that they could use them in their work. This is especially important given that experts engaged in social activities are often overburdened with work and do not always have time to read academic articles. In our case, the FGI participants benefited from the presentation of results in a visual format. However, when we sent them drafts of the academic articles for feedback, a few months after the study had ended, they had not had the time to review them. [43]

Including research participants in the process of creating and interpreting research tools also means sharing control of the research process with the participants, showing respect for and confidence in their expertise and contributions to the study (PIETRUSIŃSKA et al., 2023). While participatory approaches have many advantages, they can also lead to situations where researchers must contend with criticism and even rejection of their findings. Since interviewees have a direct influence on the research process, they may question methods, assumptions, and even results, potentially leading to conflicts and difficulties in reaching consensus. Researchers must adopt a flexible and open approach (BLACHNICKA-CIACEK et al., 2024) and be prepared to handle constructive criticism and incorporate it into subsequent stages of the study. A critical or even skeptical attitude from those involved in the study can prompt researchers to re-evaluate the underlying purpose and societal relevance of their work. Engaging in such reflection—potentially even together with contributors —opens up space for a deeper understanding of the role of research within broader social contexts, ultimately strengthening the legitimacy and public value of science, in line with an approach grounded in ethical reflexivity (VON UNGER, 2021). [44]

The final challenge we want to point out is the insider position of the researcher conducting the study. Such a position in a project concerning the forced migration of Ukrainians may traumatize the researcher who has also personally experienced the situation of the Russian war against Ukraine. In such contexts, it is essential to not only provide support and enable discussions about research situations within the research team but also, whenever possible, to arrange for research supervision (GOLCZYŃSKA-GRONDAS & WANIEK, 2022). This approach ensures a comprehensive view of the research process and its associated challenges, thereby contributing to a more ethically responsible research environment. [45]

Participatory approaches are crucial in social research, including migration and refugee studies (MATA-CODESAL et al., 2020; NIENABER et al., 2023; PIETRUSIŃSKA et al., 2023). The perspective of migrants and refugees is often marginalized in academic discourse (MILLAR et al., 2024). Therefore, their inclusion not only strengthens the research process but also aligns with the ethical imperatives of social justice, providing a platform for communities at risk of exclusion to influence the research that concerns them (NIND, 2017). Participatory research fosters inclusion and provides opportunities for participants to actively engage in and contribute to the research process, ensuring that their perspectives and experiences are accurately represented and valued. We believe that incorporating participatory elements into social studies, even those based on traditional methods, offer significant benefits and enhance the overall research process. This article highlights that the triangulation of data gained from traditional methods—in-depth individual interviews with focus group interviews along with a participatory approach fosters more dynamic and inclusive research environments (ibid.). [46]

Participation in the research process is "located somewhere on the continuum between fully egalitarian work with participants as co-researchers and the limited involvement of participants as supporters or advisors" (BROWN, 2021, p.202; CALL-CUMMINGS & ROSS, 2022). Through the co-creation research design, we not only maximize the potential of FGIs and IDIs but also align with higher levels of participation. A traditional FGI typically operates at the "consult" level, where feedback from participants informs but does not drive research decisions (VAUGHN & JACQUEZ, 2020, p.6). In contrast, our approach integrates elements of the "collaborate" and "empower" levels, emphasizing shared decision-making and knowledge co-production (NIND, 2017). This shift towards collaboration and empowerment reflects a broader trend in social studies towards methods that prioritize ethical considerations and the active involvement of research participants (PIETRUSIŃSKA et al., 2023). By moving beyond mere consultation, researchers can create more equitable partnerships with participants, ensuring that their insights and experiences shape not only the outcomes but also the direction of the research itself. [47]

The co-creation research design allows for a power balance between researchers and participants, creating a win-win situation by offering numerous opportunities for both sides that strengthen collaboration and enrich the findings. The former, for instance, have the opportunity to better tailor the study to the group involved, increase the ethical standards of their project, obtain higher quality results, and achieve broader and more accurate interpretations. The latter, on the other hand, have the ability to influence study objectives and tools, and to use research results for social change. This active involvement not only empowers participants but also ensures that the research outcomes are more relevant and actionable, directly addressing the situation and needs of the communities involved. [48]

Furthermore, by involving participants in the interpretation of findings, researchers can avoid the pitfalls of misrepresentation or oversimplification of complex social issues. This collaborative process leads to more nuanced and contextually grounded interpretations that better reflect the realities of the group engaged in the study. [49]

Such an approach not only enhances the validity and depth of research findings but also facilitates ongoing dialogue between academia and actors like NGOs, fostering enduring partnerships and improving the dissemination of research outcomes. This collaboration does not end with data collection but can be effectively continued beyond this phase. For instance, participatory research often leads to the co-creation of dissemination strategies that are more effective, ensuring that the findings reach a wider and more diverse audience, including the groups invited to participate in the study (PIETRUSIŃSKA et al., 2023). In our case, the draft of the articles disseminating the research findings (e.g., KYLIUSHYK et al., 2025; WINOGRODZKA et al., 2025) was sent to experts participating in the FGIs for their feedback. Additionally, after data collection, there is an opportunity to collaboratively prepare a policy brief aimed at promoting systemic changes to improve the situation of the communities included in the research process. [50]

Moreover, the co-creation research design supports qualitative data triangulation, enriching the analysis through the integration of diverse data sources from IDIs and FGIs (KYLIUSHYK et al., 2025). This approach allows for the cross-verification of data, thereby enhancing the reliability of the research findings (LAMBERT & LOISELLE, 2008). Such a combination of empirical data allows for more comprehensive data collection and provides insights into the studied social world from various levels and perspectives, creating a more nuanced understanding of the examined social phenomena. [51]

In the neoliberal academy that creates many challenges for participatory research (CALL-CUMMINGS & ROSS, 2022; MALONE, 2020; MILLAR et al., 2024), where resource constraints and competitive funding often limit the scope for participatory methods, we demonstrate with our approach that integrating participatory elements into traditional methods remains both feasible and advantageous. By strategically including these elements into traditional research designs, researchers can navigate the demands of the neoliberal academy while still upholding the principles of inclusivity and collaboration (KINT et al., 2024). In this context, it is important to highlight the specific responsibility of publicly funded projects. When a study is financed by taxpayers, it carries a duty not only to advance scientific knowledge but also to contribute to the public good. This includes engaging with diverse communities, valuing their perspectives, and ensuring that research outcomes are accessible and meaningful beyond academia. [52]

In summary, through the example of our methodological approach, we advocate for the deliberate incorporation of participatory elements into traditional research methods. The co-creation research design not only enhances the quality and relevance of knowledge production but also builds stronger, more collaborative relationships between researchers and participants, ultimately advancing both academic inquiry and practical social impact. We hope that this article will encourage researchers to creatively use traditional qualitative methods by adopting inclusive approaches, thereby fostering the advancement of qualitative methodology in social research. In this way, we aim for social studies where research is not just conducted on or for research participants, but with them, fully recognizing their knowledge and contributions. [53]

Aziz, Ayesha; Shams, Meenaz & Khan, Kausar S. (2011). Participatory action research as the approach for women's empowerment. Action Research, 9(3), 303-323.

Bakunzi, William (2018). Working with peer researchers in refugee communities. Forced Migration Review, 59, 58-59, https://resourcecentre.savethechildren.net/pdf/refugee_community_researchers_2018.pdf [Accessed: June 25, 2025].

Bergold, Jarg & Thomas, Stefan (2012). Participatory research methods: A methodological approach in motion. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 13(1), Art. 30, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-13.1.1801 [Accessed: June 25, 2025].

Blachnicka-Ciacek, Dominika; Winogrodzka, Dominika & Trąbka, Agnieszka (2024). Enhancing benefits for peer researchers: Towards a flexible and needs-based approach to participatory research. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2024.2417380 [Accessed: June 25, 2025].

Bourdieu, Pierre (1991 [1982]). Language and symbolic power. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Brown, Nicole (2021). Scope and continuum of participatory research. International Journal of Research & Method in Education, 45(2), 200-211.

Calabria, Verusca & Bailey, Di (2021). Participatory action research and oral history as natural allies in mental health research. Qualitative Research, 23(3), 668-685.

Call-Cummings, Meagan & Ross, Karen (2022). Spectrums of participation: A framework of possibility for participatory inquiry and inquirers. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 23(3), Art. 4, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-23.3.3825 [Accessed: June 25, 2025].

Chról, Emil & Kyliushyk, Ivanna (2025). Where do you see yourself in five years? Post-migration mobility of Ukrainian war migrants. In Izabela Grabowska, Ivanna Kyliushyk & Emil Chról (Eds.), Ukrainian female war migrants mobilising resources for prospective social remittances (pp.152-188). London: Routledge.

Clark-Kazak, Christina (2021). Ethics in forced migration research: Taking stock and potential ways forward. Journal on Migration and Human Security, 9(3), 125-138.

Cordeiro, Lucina; Soares, Cassia B. & Rittenmeyer, Leslie (2017). Unscrambling method and methodology in action research traditions: Theoretical conceptualization of praxis and emancipation. Qualitative Research, 17(4), 395-407.

Crabtree, Benjamin F.; Yanoshik, Kim M.; Miller, William L. & O'Connor, Patric J. (1993). Selecting individual or group interviews. In David L. Morgan (Ed.), Successful focus groups: Advancing the state of the art (pp.137-149). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Creswell, John W. (2009). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Cubero, Aloe; Mildenberger, Lucía & Garrido, Rocío (2024). Photovoice for promoting empowerment with migrant and refugee communities: A scoping review. Action Research, 0(0).

David, Matthew (2002). Problems of participation: The limits of action research. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 5(1), 11-17.

Dick, Karen & Frazier, Susan C. (2006). An exploration of nurse practitioner care to homebound frail elders. Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioner, 18(7), 325-334.

Duea, Stephanie R.; Zimmerman, Emily B.; Vaughn, Lisa M.; Dias, Sonia & Harris, Janet (2022). A guide to selecting participatory research methods based on project and partnership goals. Journal of Participatory Research Methods, 3(1), https://doi.org/10.35844/001c.32605 [Accessed: June 25, 2025].

Duggleby, Wendy (2005). What about focus group interaction data?. Qualitative Health Research, 15(6), 832-840.

Duncan, Marie T. & Morgan, David L. (1994). Sharing the caring: Family caregivers' views of their relationships with nursing home staff. The Gerontologist, 34(2), 235-244.

Duszczyk, Maciej; Górny, Agata; Kaczmarczyk, Paweł & Kubisiak, Andrzej (2023). War refugees from Ukraine in Poland—One year after the Russian aggression. socioeconomic consequences and challenges. regional Science Policy & Practice, 15(1), 181-200.

Enria, Luisa (2016). Co-producing knowledge through participatory theatre: Reflections on ethnography, empathy and power. Qualitative Research, 16(3), 319-329.

Fedyuk, Olena; Homel, Kseniya; Jóźwiak, Ignacy; Kindler, Marta; Kowalska, Kamila; Kyliushyk, Ivanna; Lashchuk, Iuliia; Matuszczyk, Kamil & Tygielski, Maciej (2024). From temporariness to stability: A holistic approach to the employment of women covered by the special law in Poland / Od tymczasowości do stabilności: Holistyczne podejście do zatrudnienia kobiet objętych specustawą w Polsce. EUI, RSC, Policy Brief 2024/17, Migration Policy Centre, https://hdl.handle.net/1814/77175 [Accessed: June 25, 2025].

Gawlik, Katarzyna (2012). Badania fokusowe [Focus group research]. In Dariusz Jemielniak (Ed.), Badania jakościowe. Metody i narzędzia 2 [Qualitative research: methods and tools] (pp.132-135). Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN.

Gilodi, Amalia; Ryan, Louise & Aydar, Zeynep (2025). Peer research in a multi-national project with migrant youth: Re-thinking vulnerability and participatory approaches. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 26(2), Art. 16, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-26.2.4276 [Accessed: June 25, 2025].

Goeke, Stephanie & Kubanski, Dagmar (2012). People with disabilities as border crossers in the academic sector—chances for participatory research. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 13(1), Art. 6, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-13.1.1782 [Accessed: June 25, 2025].

Golczyńska-Grondas, Agnieszka & Waniek, Katarzyna (2022). Superwizja w jakościowych badaniach społecznych. O radzeniu sobie z trudnymi emocjami badających i badanych [Supervision in qualitative social research: Coping with the difficult emotions of researchers and participants. Qualitative Sociology Review, 18(4), 6-33, https://doi.org/10.18778/1733-8069.18.4.01 [Accessed: June 25, 2025].

Górny, Agata & Kaczmarczyk, Paweł (2023). Between Ukraine and Poland. Ukrainian migrants in Poland during the war. CMR Spotlight, 2(48), https://www.migracje.uw.edu.pl/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/Spotlight-FEBRUARY-2023.pdf [Accessed: June 25, 2025].

Guillemin, Marilys, & Gillam, Lynn (2004). Ethics, responsibility and "ethically important moments" in research. Qualitative Inquiry, 10(2), 261-280.

Hacker, Karen (2013). Community-based participatory research. London: Sage.

Hyden, Lars C. & Bulow, Pia H. (2003). Who's talking: Drawing conclusions from focus groups-some methodological considerations. Social Research Methodology, 6(4), 305-321.

Kairuz, Therese; Crump, Keith & O'Brien, Anthony J. (2007). Tools for data collection and analysis. The Pharmaceutical Journal, 278, 371-377.

Kilpatrick, Rosemary; McCartan, Claire; McAlister, Siobhan & McKeown, Penny (2007). "If I am brutally honest, research has never appealed to me …". The problems and successes of a peer research project. Educational Action Research, 15(3), 351-369.

Kindon, Sara; Pain, Rachel & Kesby, Mike (2007). Participatory action research: Origins, approaches and methods. In Sara Kindon, Rachel Pain & Mike Kesby (Eds.), Participatory action research approaches and methods: Connecting people, participation and place (pp.9-18). London: Routledge.

Kint, Octavia; Duppen, Daan; Vandermeersche, Geert; Smetcoren, An S. & De Donder, Liesbeth (2024). How "co" can you go? A qualitative inquiry on the key principles of co-creative research and their enactment in real-life practices. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 28(1), 87-103.

Kuckartz, Udo & Rädiker, Stefan (2019). Analyzing qualitative data with MAXQDA: Text, audio, and video. Cham: Springer.

Kyliushyk, Ivanna & Chról, Emil (2025). Ukrainian female migration in a historical perspective. In Izabela Grabowska, Ivanna Kyliushyk & Emil Chról (Eds.). Ukrainian female war migrants mobilising resources for prospective social remittances (pp.7-31). London: Routledge.

Kyliushyk, Ivanna; Winogrodzka, Dominika & Chról, Emil (2025). The twists and turns of mobility capital formation. A multi-level analysis of factors impacting capital building among Ukrainian forced migrants in Poland. Mobilities, 1-18.

Lambert, Sylvie D. & Loiselle, Carmen G. (2008). Combining individual interviews and focus groups to enhance data richness. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62(2), 228-237.

Lushey, Clare J. & Munro, Emily R. (2015). Participatory peer research methodology: An effective method for obtaining young people's perspectives on transitions from care to adulthood?. Qualitative Social Work, 14(4), 522-537.

Maison, Dominika (2022). Jakościowe metody badań społecznych. Podejście aplikacyjne [Qualitative methods in social research: An applied approach]. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN.

Malone, Aaron (2020). Migrant communities and participatory research partnerships in the neoliberal university. Migration Letters, 17(2), 239-247, https://doi.org/10.59670/ml.v17i2.805 [Accessed: June 25, 2025].

Mata-Codesal, Diana; Kloetzer, Laure & Maiztegui-Oñate, Concepcion (2020). Editorial: Strengths, risks and limits of doing participatory research in migration studies. Migration Letters, 17(2), 201-210, https://migrationletters.com/index.php/ml/article/view/934 [Accessed: June 25, 2025].

McIntyre, Alice (2008). Participatory action research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Millar, Gearoid; Volonterio, Matias; Cabral, Lidia; Peša, Iva & Levick-Parkin, Melanie (2024). Participatory action research in neoliberal academia: An uphill struggle. Qualitative Research, 25(2), 478-498, https://doi.org/10.1177/14687941241259979 [Accessed: June 25, 2025].

Moralli, Melissa (2024). Arts-based methods in migration research. A methodological analysis on participatory visual methods and their transformative potentials and limits in studying human mobility. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 23, https://doi.org/10.1177/16094069241254008 [Accessed: June 25, 2025].

Morgan, David L. (1996). Focus groups. Annual Review of Sociology, 22, 129-152.

Nassar-McMillan, Sylvia C. & Borders, Dianne L. (2002). Use of focus groups in survey item development. The Qualitative Report, 7(1), 1-12, https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2002.1987 [Accessed: June 25, 2025].

Nienaber, Birte & Kriszan, Agnes (2023). Thinking with the hands: LEGO® Serious Play® a game-based tool to empower young migrants integrating. Migration Letters, 20(3), 443-452, https://migrationletters.com/index.php/ml/article/view/2902 [Accessed: June 25, 2025].

Nienaber, Birte; Oliveira, Jose & Albert, Isabelle (Eds.) (2023). Doing action research with young migrants in vulnerable conditions. MIS-Working Paper, Université du Luxembourg, https://orbilu.uni.lu/bitstream/10993/60361/1/MIS_Working-paper_Doing-action-research-with-young-migrants-in-vulnerable-conditions_clean-version73.pdf [Accessed: February 10, 2025].

Nikielska-Sekula, Karolina & Desille, Amandine (Eds.) (2021). Visual methodology in migration studies new possibilities, theoretical implications, and ethical questions: New possibilities, theoretical implications, and ethical questions. Cham: Springer.

Nind, Melanie (2017). The practical wisdom of inclusive research. Qualitative Research, 17(3), 278-288.

Pietrusińska, Marta J.; Winogrodzka, Dominika & Trąbka, Agnieszka (2023). Researching young migrants in vulnerable conditions. Methodological and ethical guidelines based on the MIMY project. Deliverable No. 8.3. Methodological guidelines and manuals for replications in migration studies. SWPS University of Social Sciences and Humanities, https://mimy-project.eu/outcomes/public-deliverables/MIMY_870700_D8-3_Methodological-guidelines-and-manuals-for-replications-in-migration%20studies_final.pdf [Accessed: February 10, 2025].

Pincock, Kate & Bakunzi, William (2021). Power, participation, and "peer researchers": Addressing gaps in refugee research ethics guidance. Journal of Refugee Studies, 34(2), 2333-2348.

Plack, Margaret M. (2006). The development of communication skills, interpersonal skills, and a professional identity within a community of practice. Journal of Physical Therapy Education, 20(1), 37-46.

Pustulka, Paula; Bell, Justyna & Trąbka, Agnieszka (2019). Questionable insiders: Changing positionalities of interviewers throughout stages of migration research. Field Methods, 31(3), 241-259.

Tokola, Nina; Rättilä, Tina; Honkatukia, Pavi; Mubeen, Fath & Sillanpää, Olli (2023). Participatory research among youth—too little, too much, too romanticised?. In Päivi Honkatukia & Tiina Rättilä (Eds.), Young people as agents of sustainable society: reclaiming the future (pp.161–176). London: Routledge.

Vaughn, Lisa M. & Jacquez, Farrah (2020). Participatory research methods—Choice points in the research process. Journal of Participatory Research Methods, 1(1), https://doi.org/10.35844/001c.13244 [Accessed: February 10, 2025].

Von Unger, Hella (2021). Ethical reflexivity as research practice. Historical Social Research, 46(2), 186-204, https://doi.org/10.12759/hsr.46.2021.2.186-204 [Accessed: February 10, 2025].

Winogrodzka, Dominika; Kyliushyk, Ivanna & Chról Emil (2025). Mobility capital formation among forced migrants—Based on the example of Ukrainian women living in Poland due to the escalation of the Russian invasion. Migration Studies, 13(2), https://doi.org/10.1093/migration/mnaf019 [Accessed: February 10, 2025].

Ivanna KYLIUSHYK, PHD, is a political scientist and sociologist. In her work, she focuses on migration studies, particularly Ukrainian migration, with a special emphasis on Ukrainian women's mobility. She also has a strong interest in qualitative research methods. Currently, Ivanna is an assistant professor (postdoc) at the Center for Research on Social Change and Human Mobility (CRASH) at Kozminski University, where she is involved in several international and national scientific projects, including "Link4Skill," Horizon Europe 2023, no. 101132476 and the BigMig project, National Science Centre of Poland, OPUS 19, no. 2020/37/B/HS6/02342. She also contributed to the "MIMY: Empowerment Through Liquid Integration of Migrant Youth in Vulnerable Conditions” project, Horizon Europe 2020, no. 870700.

Contact:

Ivanna Kyliushyk

Center for Research on Social Change and Human Mobility,

Kozminski University

57/59 Jagiellonska Street, Warsaw, 03-301, Poland

E-mail: ikyliushyk@kozminski.edu.pl

Dominika WINOGRODZKA, PhD, is a sociologist and social researcher who focuses on youth studies, career studies, and mobility studies. She has published in leading academic journals, including the Journal of Youth Studies, the Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, and the International Journal of Social Research Methodology. She is a laureate of numerous scholarships from the National Science Centre, Poland (including SONATA BIS, PRELUDIUM, and OPUS). Her recent research projects include “MIMY: Empowerment Through Liquid Integration of Migrant Youth in Vulnerable Conditions," Horizon 2020, no. 870700, and "INSIMO: Work (In)stability and Spatial (Im)mobility from the Perspective of Young People on the Move. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic," National Science Centre, Poland, PRELUDIUM no. 2021/41/N/HS6/03681. Dominika is currently an assistant professor at the Institute of Sociology of the Jagiellonian University in Cracow.

Contact:

Dominika Winogrodzka

Institute of Sociology

Jagiellonian Univeristy

52 Grodzka Street, Cracow, 31-044, Poland

E-mail: dominika.winogrodzka@uj.edu.pl, dwinogrodzka@kozminski.edu.pl

Emil CHRÓL, PhD candidate, is a social researcher working at the intersection of sociology, anthropology, and political science. He is currently pursuing his doctoral degree at the Interdisciplinary Doctoral School of the University of Warsaw, where in his research he focuses on the changes of Ukrainian national identity in the context of war, migration, and cultural change. His academic interests include international relations, mobility, diaspora, identities, and the sociology of conflict. He has contributed as a qualitative researcher to several national and international scientific projects, e.g., "Link4Skill," Horizon Europe, no. 101132476. His most recent project is entitled: "TheseusUA: a study of changes in identity discourses and practices among Ukrainians as a reaction to Russian aggression," National Science Centre of Poland, PRELUDIUM 23, no. 2024/53/N/HS5/00353.

Contact:

Emil Chról

Center for Research on Social Change and Human Mobility,

Kozminski University

57/59 Jagiellonska Street, Warsaw, 03-301, Poland

E-mail: echrol@kozminski.edu.pl

Kyliushyk, Ivanna; Winogrodzka, Dominika & Chról, Emil (2025). Co-creating research design: How to achieve participation in social studies using traditional methods? [53 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 26(3), Art. 10, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-26.3.4381.