Volume 26, No. 3, Art. 14 – September 2025

Temporality in Ethnography of Discourse: Untangling Discursive Knots Related to English Language Teaching at a Public University in Uruguay

Patricia Carabelli

Abstract: Social scientists rarely address temporal issues explicitly, neither when defining a methodology nor when detailing results; nonetheless, aspects concerning it are an intrinsic part of social processes as the existence of subjects occurs within a plurality of times. Thus, when carrying out research to describe the aims and process of teaching English as a foreign language at a public university in Uruguay, a methodology was chosen that would enable capturing the historicity of this object of study. An ethnography of discourse in educational contexts was carried out considering JÄGER's (2003) methodological approach as it entails the development of a dispositive to analyze the complexity of historical, multilayered and contextualized discourses. In my research, I delineated aims focused on three discursive knots that happen simultaneously, at different cross-institutional levels, articulating the teaching of English: 1. The political/university knot (macro level), 2. the knowledge/know-how knot (meso level), and 3. the teaching knot (micro level). The identification of discursive threads by using different research tools (document analysis, semi-structured interviews, surveys, and classroom observations) enabled the study of diachronic and synchronic aspects concerning English teaching and knowledge. In this article, I detail methodological aspects concerning temporality while describing the research process.

Key words: temporality; ethnography of discourse; social research; research methodology; English language teaching

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. Framework

3. Literature Review: Bordering Temporality in Relation to the Object of Study

4. Methodology: Configuring a Research Dispositive

4.1 Main and specific research aims

4.2 Temporality and JÄGER's notion of discourse

4.3 Elaborating a dispositive to untangle discursive knots

4.4 Choosing and designing appropriate research tools

5. Analyzing the Data Collected: Themes, Intertextualities and Interdiscursivities

5.1 Defining categories and grouping information

5.2 Demonstrating methods of data coding and analysis

6. Overlapped and Multilayered Findings

7. Concluding Remarks

Lives are determined by temporality; beings are conceived in relation to it. Everything social or natural develops in relation to time, changing in unpredictable ways and in connection with multiple factors that affect its context. Time envelops everything and has been a matter of study and thought (ARISTOTLE, 1957 [circa 350 B.C.]. HEIDEGGER, 2001 [1927]), was the first to conceive an objective and infinite notion of time during ancient times, but not as temporality; he envisaged the common, or sometimes called "vulgar" or “ordinary” (pp.472-474; see also KELLER, 2008 [1996]) notion of time—i.e., the clock's time related to astronomical changes—as a measuring parameter made by a mathematical series of infinite components. [1]

This quantitative representation of time unfolds in a unique direction, and instants can be allocated in specific places on timelines or calendars. According to SIMESEN DE BIELKE (2017, p.292), HEIDEGGER represented this time as an infinite succession of isolated and homogeneous present times ("nows"1)), that can only be differentiated by the place they occupy in the mathematical series. In history, this notion of time, considered "absolute time" (DEMASI, 1997, p.42), is sometimes used for chronological purposes to order different events according to the date when they happened. As GEIßLER (2002, p.133) stated, "clocks were to guarantee punctuality, control of time and the standardization of conduct in relation to time." Nonetheless, there are other ways of conceiving time—and not only non-linear ones, or the cyclical ones used by sailors and farmers in relation to weather—there are complex qualitative ways used by social science researchers (BRAUN & CLARKE, 2021; GIROLA, 2011; GOKMENOGLU, 2022; GORE et al., 2021; HANNKEN-ILLJES, KOZIN & SCHEFFER, 2007; HENRY & MACINTYRE, 2024; MURILLO, 2013; SCHILLING & KÖNIG, 2020; VALENCIA GARCÍA, 2002) that imply a different kind of notion known as temporality. [2]

Social researchers intrinsically rely on inherent aspects concerning temporality to comprehend the complex narratives that give place to the realities understudy. In memory studies, aspects related to temporality are explicitly mentioned, and this is a growing field. Nevertheless, many researchers exclude its analysis when developing a conceptual framework or presenting results (CLIFT, MERCHANT & FRANCOMBE-WEBB, 2021; GEIßLER, 2002) and, hence, methodological development in the area is scarce (GOKMENOGULU, 2022). [3]

In this paper, I focus on temporality aspects that were considered while designing and carrying out an ethnography of discourse study at a Spanish-speaking university in Uruguay to describe why English is taught at this university, since when, what linguistic policies exist, how many courses are being offered and where, what functions of English are appealed to, and what curricular contents and approaches are prioritized. I begin with a description of the chosen epistemological approach as it is crucial to understand what the main concepts being used imply (Section 2). Thereafter, I detail the state of the art concerning the two fields I studied: Temporality and English language teaching in Uruguay, by analyzing what different researchers have found (Section 3). Then, I provide a detailed account of the methodology used in this investigation, as I wrote this paper to describe and illustrate how temporality issues were considered while conducting an ethnography of discourse (Section 4). In Section 5, I present some of the data found and explain how they were examined to show how temporality issues emerge at multiple levels of discourse. In Section 6, after discussing how the data were analyzed, I provide an overview of the main findings by illustrating how discourses occur simultaneously at multiple institutional levels. I conclude by summarizing the relevance of considering temporality issues in order to understand the described object of study in depth, its past, present and possible future implications (Section 7). [4]

English as a foreign language courses have been offered at the Uruguayan public university where the research took place almost since its foundation. However, researchers who carried out investigations concerning English language teaching at a local level have focused mainly on non-university settings, and little was known—from historical and situated perspectives—about the teaching of English at this university. In order to describe different aspects in relation to this practice (linguistic policies, internationalization processes, functions of English prioritized, number of courses offered, curricular aims, content and approaches), and to understand what teaching English as a foreign language at this university entails at present, and in relation to its past and future (GEIßLER, 2002; HANNKEN-ILLJES, 2007), a genealogy (BIALAKOWSKY, 2017; DEMASI, 1997; FOUCAULT, 2002 [1969]) concerning the process of development of this practice was carried out by studying discourses at different institutional levels (HIVER & AL-HOORIE, 2020; JOHNSON, 2011, 2015). [5]

From a complex qualitative research perspective in linguistics (GORE et al., 2021), and based on JÄGER's (2003) methodological approach within critical discourse analysis (WODAK & MEYER, 2003), a five-year study was carried out. The approach, which involved the development of a dispositive to examine the complexity of multilayered discourses (HIVER & AL-HOORIE, 2020; JOHNSON, 2011, 2015), was employed to analyze and describe the process which the object of study underwent since its origin. The objective of the research was to study three main discursive knots which, according to BEHARES (2011), articulate education at the university where the research took place, and hence, also involve the process of teaching English at this institution, i.e., 1. The political/university knot (macro level), 2. the knowledge/know-how knot (meso level), and, 3. the teaching knot (micro level). [6]

To carry out the research process, a "time window" (NEALE, 2021, p.120) was chosen (2019-2023), a dispositive was devised (JÄGER, 2003; JÄGER & MAIER, 2009; JOHNSON, 2009, 2011, 2013, 2015), and instruments were produced bearing in mind temporal perspectives for data collection (NEALE, 2021; SCHILLING & KÖNIG, 2020). The dispositive was designed to examine some of the multiple coexisting temporalities (GEIßLER, 2002; HANNKEN-ILLJES, 2007), periods of stability and transition—including the appearance of possible disruptive emergency situations (FOUCAULT, 2002 [1969])—regarding the process of teaching English at the chosen university. [7]

3. Literature Review: Bordering Temporality in Relation to the Object of Study

A wide range of literature was consulted in relation to the research's methodology and the object of the study. Once the latter was defined, a methodology that could capture its historicity, its stabilities and variations throughout the plurality of time had to be chosen to hermeneutically explain the complex processes which the teaching of English underwent. Although this methodology will be thoroughly discussed in the following section, it implied research and decisions in two main areas: 1. Temporality, by considering perspectives that enable diachronic and synchronic analysis when necessary (BRAUN & CLARKE, 2021; CLIFT et al., 2021; DEMASI, 1997; GEIßLER, 2002; GOKMENOGLU, 2022; GORE et al., 2021; HANNKEN-ILLJES, 2007; HANNKEN-ILLJES et al., 2007; HEIDEGGER, 2001 [1927]]; HENRY & MACINTYRE, 2024; SALDANA, 2003; SCHILLING & KÖNIG, 2020; SIMESEN DE BIELKE, 2017; THOMAS et al., 2024; VALENCIA GARCÍA, 2002), and, 2. discourse studies in which researchers focused on ways of examining complex social processes (FOUCAULT, 2002 [1969]; JÄGER, 2003; JOHNSON, 2011, 2015; WODAK & MEYER, 2003), such as ethnographies of discourse in education settings (JOHNSON, 2011, 2015). The readings and choices made in relation to the methodology based on discourse analysis theory are described in Section 4. [8]

Temporality is related to the ontological and hermeneutical functions of time in relation to the presence of beings and the nature of things in the world. KANT (2004 [1781]) first, and HEIDEGGER (2001 [1927]) later, explained how complex, dynamic and intertwined connections between present, past, and future configure beings by providing meaning and sense while nurturing historicity. This historicity constitutes subjectivity as it is related to the existence of subjects, their moments of transformation and stability from the point of origin to their death. It enables a genealogy of the subject (FOUCAULT, 2002 [1969]), a cartography or mapping of the different experiences a subject undergoes through life (NEALE, 2021), characterized by the existence of diachronicity and synchronicity concerning its history, as multiple layers of time coexist and overlap (GEIßLER, 2002; GORE et al., 2021; HANNKEN-ILLJES, 2007). Although everything undergoes processes of change at different rhythms and speeds, a diachronic perspective allows an approximation to the object of study by capturing aspects that persist or show certain stability throughout time (BIALAKOWSKY, 2017). In contrast, a synchronic approach facilitates an in-depth study of a specific moment in time, generally by selecting a time window research period where something disruptive or of specific interest has occurred (NEALE, 2021). The study of the temporality of a subject enables an understanding of some of the different processes it undergoes (CLIFT et al., 2021; DEMASI, 1997; GOKMENOGLU, 2022; SCHILLING & KÖNIG, 2020; THOMAS et al., 2024; VALENCIA GARCÍA, 2002). [9]

To understand the present situation regarding the dynamic process of teaching English as a foreign language at a public university in Uruguay, its origins and periods of stability and disruption had to be traced (DEMASI, 1997; GORE et al., 2021; HENRY & MACINTYRE, 2024; NEALE, 2021). Linguistic policies (CALVET, 1997 [1996]; JOHNSON, 2013, 2015; SCHIFFMAN, 1996) and social representations (GIROLA, 2011) related to the present, past and future of English language in the specific context had to be studied to describe the complex processes involved (GORE et al., 2021; HIVER & AL-HOORIE, 2020; THOMAS et al., 2024). HENRY and MACINTYRE (2024) mentioned that qualitative studies involving temporality are generally small-scale ones. However, my research could be considered a large-scale project since no previous institutional records describing solely the object of study existed, and the process it underwent had to be studied by using a combination of intensive data-collecting strategies (focused on the perspectives of specific English language professors) and extensive ones (covering a long period of time) (NEALE, 2021); hence, a first genealogy of the object of study, capturing its origin and change during plural times, was traced to understand its present situation, past and possible future (BIALAKOWSKY, 2017; GOKMENOGULU, 2022; MURILLO, 2013; STAEHLER, 2020; VALENCIA GARCÍA, 2002). To understand the methodology, a summary of the context where the situation under study was temporally embedded (GORE et al., 2021; NEALE, 2021) is provided. [10]

Studying Uruguay's history concerning English language uses and education was the logical starting point of the research process (THOMAS et al., 2024). At present, Spanish is the de facto language in Uruguay. Nevertheless, it is a country with plurilingual origins (BARRIOS, 2015; BERTOLOTTI & COLL, 2014; CANALE, 2015; MASELLO, 2020) as—apart from original native languages and Portuguese (that was spoken on Uruguay's border with Brazil)—migrants who settled in this state between 1860 and 1920 spoke in their native tongues (mainly Spanish, Galician, Italian, English, French and German). Nevertheless, Spanish is the common language as, between 1876 to 1877, during a dictatorship period, a nationalist movement promoted this tongue as the state's only language and thus hindering the use of multiple ones (OROÑO, 2016). Current studies indicate that, although Spanish must be used in different official instances due to laws that require this, linguistic diversity exists (BROVETTO, 2017; CANALE, 2015). [11]

In education, linguistic policies concerning foreign and second languages can be traced back in time in relation to two public systems: The national organism in charge of public education at the initial, primary and secondary levels (Administración Nacional de Educación Pública, ANEP), and the main national public university (Universidad de la República) where this research took place. Each system is independent of the other. Previous research studies and policies were investigated concerning both the understanding of the country's context and the historicity of the language under study. In the former institution, several investigations concerning English were carried out (BROVETTO & KAPLAN, 2011; CANALE, 2011, 2013, 2018; FRADE, 2017), and a commission in charge of elaborating linguistic policies was created in 2006, although English had been taught in this system since the nineteenth century. Currently, different English programs coexist, and plurilingualism is promoted regarding second and foreign languages (BROVETTO, 2017; MINISTERIO DE EDUCACIÓN Y CULTURA, 2008). [12]

In the case of the university, plurilingualism is promoted (MASELLO, 2019a) and, although languages such as English and French have been taught there since 1838—almost since its foundation (MASELLO, 2019b)—few and recent investigations have been carried out concerning English teaching in particular (CARABELLI, 2012, 2021; COUCHET, 2012; COUCHET & MUSTO, 2017; GABBIANI & MADFES, 2006; TORRES, VIERA & FEDORCZUK, 2009). To better understand the situation of the target language at both national and international levels, diverse investigations concerning this topic at university level worldwide were also analyzed (BOND, 2020; GONZÁLEZ-ÁLVAREZ & RAMA-MARTÍNEZ, 2020; LIDDICOAT, 2018). [13]

4. Methodology: Configuring a Research Dispositive

The notion of "discursive knots" (JÄGER, 2003, p.81; JÄGER & MEIER, 2009, p.47) was the fundamental construct of this research as it enabled an exploration of the complexities of the object of study. It allowed for the identification of discursive threads that configure the teaching of English at the chosen national public university. Adopting this perspective implied studying discourses produced at different historical times, by different agents, and at multiple institutional levels. [14]

4.1 Main and specific research aims

My main objective was to analyze and describe the process of teaching English as a foreign language at Uruguay's main public university, the Universidad de la República, in relation to: 1. The political/university knot, 2. the knowledge/know-how knot, and 3. the teaching knot. To achieve this, I formulated and adhered to the following specific objectives:

Identifying linguistic policies (explicit and implicit) that emerged in discourses related to English teaching at the chosen university. With this specific aim, the political/university knot and the knowledge/know-how knot, mainly related to macro institutional policies, were analyzed to answer the following questions: Why is English taught at this university and in which dependencies? When did the practices start and what were the justifications for their introduction? Did all the university's dependencies share the same justifications? Were those continuous in time or were there variations or disruptive emergency situations in relation to the policies and practices?

Collecting existing course syllabi to identify the courses offered and examine, by carrying out surveys and interviewing students and professors, how the teaching of English has been tackled at the discourse level in the dependencies of the university where English has been taught. By doing this, different discursive threads from the political/university knot and the knowledge/know-how knot were identified at the meso levels of the institution. The following guiding questions were answered: What were the learning objectives, curricular contents, and approaches outlined in the different syllabi? Which similarities and differences existed across the courses offered at the university dependencies? What functions of English were prioritized? What graduate profile did the different programs configure.

Examining if a specific approach to English language teaching is constructed in discourses of agents (students and professors) and their actions to describe some of the discursive threads related to the knowledge/know-how knot and the teaching knot at micro institutional levels. By doing so, teaching perspectives, outcomes, and the functions of English that were put into play during lessons could be identified. [15]

4.2 Temporality and JÄGER's notion of discourse

JÄGER (2003), based on critical discourse analysis theory, adopted FOUCAULT's (2002 [1969]) and LINK's (1983 in JÄGER, 2003) considerations of discourse and understood that all discourses are historical and material entities constituted by the accumulation of knowledge produced. As such, discourses are imbricated in everything we do individually and collectively, and they are developed through actions and social practices that produce and reproduce knowledge. Discourses transform over the course of history and may emerge simultaneously at different levels in intertwined and complex ways constituting the objects they refer to. Discursive practices and non-discursive practices, such as actions or events that evidence a subjacent knowledge, develop discourses. Moreover, discourses are institutionalized; and mechanisms of validation, inclusion, limitation, and exclusion exist. As JÄGER (2003, p.64) stated, "negation strategies, strategies to relativize, strategies to eliminate taboos" are used. Because of this complexity, JÄGER emphasized that a historical perspective is necessary considering the moments and contexts when discourses occur, interact and overlap. [16]

As JÄGER and MAIER (2009) detailed, discourses are made by combining infinite texts, and a "fragment of discourse" (p.47) implies a specific theme that can be found in a text or part of it (and, I would add, at a certain moment and context). Therefore, a discursive thread can be studied by analyzing fragments of discourses concerning a specific theme that may appear in many different texts produced at different moments. In this sense, by identifying and examining a discursive thread, one may study a theme's development—moments of appearance, recurrence or disruptive emergency situations related to it—from a historical (non-chronological or lineal) perspective (DEMASI, 1997; FOUCAULT, 2002 [1969]; GORE et al., 2021). [17]

Discourses are complex because they do not refer to a unique theme; they relate to many themes simultaneously and at different times. Generally, primary and secondary themes are mentioned, and multiple layers of time emerge, generating multimodal data (GORE et al., 2021). Hence, discourses include many tangled, intermixed, discursive threads that simultaneously refer to several themes at multiple times. These discursive threads constitute a "discursive knot" (JÄGER & MAIER, 2009, p.47). Studying discursive knots involves identifying specific discursive threads in the knot to untangle or separate them from other threads, based on the theme being addressed, while analyzing the interrelations at different levels. Methodologically, this was done by defining the three basic cross-temporality and institutional layers (micro, meso and macro), studying discourses by identifying and classifying key thematics (GIBSON & BROWN, 2009), and examining the intertextualities and the interdiscourses (JOHNSON, 2013, 2015) that emerge in relation to them. This is thoroughly discussed in the following section. [18]

4.3 Elaborating a dispositive to untangle discursive knots

Research dispositives must be carefully elaborated to study the complexity of discourses. As JOHNSON (2015) stated, when examining discourses, studying intertextuality is necessary as discourses do not occur in isolation; they are interconnected and influence each other's meaning. This meaning, which may be interrupted or reinforced, crosses discourses in diachronic ways, horizontally, persisting in time (for example, when people at present cite SHAKESPEARE's soliloquy "To be or not to be" [1976 (1603)] despite it being written in 1603). Yet, it also crosses discourses synchronically as discourses are heteroglossic (BAJTÍN, 1979) and have multiple meanings that can be studied at a specific moment in history (in relation to the previous example, a pianist, a computer engineer, and a material designer may understand SHAKESPEARE's soliloquy in different ways because of the multiple overlapped discourses that conform their subjectivity). Hence, as analyzing discourses is highly complex, one way of examining them is by designing specific research dispositives, bearing in mind: 1. Discursive and non-discursive practices (actions) (JÄGER, 2003; JOHNSON, 2013, 2015), 2. contexts of appearance (including different institutional layers) (JOHNSON, 2013, 2015; MADFES, 2013), and 3. temporality of discourses as meaning concerning the present, past and even future possibilities may be traced (BIALAKOWSKY, 2017; GOKMENOGULU, 2022; GORE et al., 2021; MURILLO, 2013; STAEHLER, 2020; VALENCIA GARCÍA, 2002) by using extensive and intensive (NEALE, 2021) research tools. [19]

Moreover, as discourses are supra-individual, collective symbols that characterize a situation under study and representations shared by social groups (GIROLA, 2011) must be comprehended to some extent as well. As individual and social consciousness are intertwined and imbricated with knowledge (re)produced by circulating discourses (WODAK & MEYER, 2003), they may be described by analyzing recurring themes (GIBSON & BROWN, 2009), intertextualities and interdiscourses (JOHNSON, 2015). These aspects may be studied by using discourse analysis strategies based on the identification and examination of themes, discursive threads, discursive fragments, discursive knots, discursive events, discursive contexts, planes and postures. [20]

During the research, social representations were analyzed by identifying themes—from oral and written texts and produced in specific contexts—in the different thematic threads found within the three identified discursive knots. A thematic analysis approach (GIBSON & BROWN, 2009) was chosen because it implies the identification of themes in discourses that emerge simultaneously in different layers of the institution and at diverse times. It is an approach that enables a temporal analysis of themes as it captures the changes within a broader process, within a thematic thread. This perspective enables researchers to move beyond the instant, capturing more than a moment in time and tracing narratives that emerge by unveiling specific themes in texts that are part of discourse threads. It is a way of studying how themes change, persist or are abandoned within discourses. Social representations are identified within the discourses by analyzing themes shared by many individuals as these are recurrent across multiple discourse threads. By doing so, researchers may establish cross-contextual connections between the past, present and future considering specific thematic threads that emerge and may also identify discursive knots. As JÄGER (2003, p.86) stated, there is a discursive knot when a text refers to many themes simultaneously, even if one of them is a primary theme. If this happens:

"Discursive processes should be analyzed within broader temporal frameworks to reveal their force, the density of the knot regarding certain discursive threads with other discursive threads, together with their changes, fractures, disappearance and reappearance. In other words, it will be necessary (as Foucault states) to elaborate an 'archaeology of knowledge', or, as he stated later, a 'genealogy'." [21]

To elaborate a genealogy considering the process of teaching English at the university where the investigation took place, an analysis of intertextualities and interdiscursivities (JOHNSON, 2013, 2015) was also adopted. This approach included a historical dimension by establishing the possibility of making connections between discourses that happen simultaneously at different moments, and a complex dimension by enabling associations between discourses that occur in different layers or that seem unrelated. In this sense, themes were studied considering: "Horizontal intertextualities" (JOHNSON, 2015, p.167) (establishing connections between texts that shared a common theme, and happened simultaneously in time, although they belonged to different institutional and societal levels), "vertical intertextualities" (ibid.) (studying texts with a shared theme that happened at different historical moments), and "interdiscursivities" (p.168) (that enabled the connection between institutional and social discourses that seemed unconnected). [22]

For example, when analyzing the lexis (identifying key and recurrent words related to specific themes) of a general linguistic university norm established in 2001—which stated that postgraduate students had to prove reading comprehension in one or two foreign languages to graduate from master's and doctoral programs (UNIVERSIDAD DE LA REPÚBLICA, 2001)—the theme reading comprehension was identified as a priority at the macro level of the institution. A discourse thread related to the theme reading comprehension was, hence, acknowledged. When different syllabi were collected from different university dependencies, one of the first observations at the meso-institutional level was that, out of the twenty-three identified English courses (23 out of 77 foreign language courses), eight were designated as reading comprehension courses, as they focused on the development of this skill. The theme's recurrence evidenced the existence of horizontal and vertical intertextualities in relation to reading comprehension in English, as documents were created at different moments (vertical intertextualities) and in diverse dependencies (faculties, centers or institutes) of the university (horizontal intertextualities). Finally, during several classroom observations, professors focused on teaching aspects related to the development of this same skill and both, professors and students highlighted, when interviewed, the importance of being able to read in English to access knowledge written in this language. Once again, the theme reading comprehension in English reappeared—now at the micro level—evidencing the existence of interdiscursivities, as discourses across the different levels (institutional norms, syllabi, lessons, and individual agents) include the recurring theme, thereby reinforcing its concept and its associated notions. [23]

The elaboration of the dispositive enabled the identification and examination of the following discursive threads:

Historical-institutional processes related to the teaching of foreign languages, English in particular;

social representations that circulate within and outside the institution concerning the English language;

the vitality and functions of English at an international level;

the role of English in relation to internationalization processes within universities;

norms and documents that structure the presence of English language education within the university and its dependencies;

students' entry and graduation profiles;

professors' situated discourses and approaches to language teaching during English lessons. [24]

4.4 Choosing and designing appropriate research tools

Although a time window between 2019 and 2023 was selected to establish the period and context in which the research took place, a genealogy was elaborated. Therefore, it may be considered a long-scale research project, where extensive and intensive data collection strategies (NEALE, 2021) were carefully chosen and, when necessary, elaborated. [25]

The research implied two types of data: 1. Pre-existent data, that were part of the context under study (institutional documents such as norms and regulations, course syllabi, classroom materials and resources), and 2. data generated during the research, considering its aims (through semi-structured interviews, surveys and classroom observations). Research tools were selected, designed, tested, validated and applied for each type of data as they entailed different temporal concerns (GORE et al., 2021). A few adjustments had to be made as research projects often involve iterations (ibid., see also JOHNSON, 2015; MEYER, 2003). To filter existing information, document analysis techniques were applied. [26]

In relation to document analysis, cross-institutional public documents—such as norms, regulations and publications related to English and foreign language requirements, documents that mention the implementation or existence of English language courses, and existing English courses' syllabi—were reviewed across all the university's faculties, centers and institutions. The recommendations concerning document analysis proposed by BORÉUS and BERGSTRÖM (2017) and PIÑUEL RAIGADA (2002), as well as the thematic analysis guidance provided by GIBSON and BROWN (2009), were followed during the process. This extensive, diachronic review enabled an understanding of the process the object of study underwent, as its moments of change and stability could be pictured with the data found (CLIFT et al., 2021; GOKMENOGLU, 2022; GORE et al., 2021; NEALE, 2021; THOMAS et al., 2024). For example, in relation to the research, and regarding the post-graduate norm previously mentioned (UNIVERSIDAD DE LA REPÚBLICA, 2001), a unique cross-institutional norm related to knowledge of foreign languages was established on September 25, 2001. This norm indicated that until that date, there were no general rules regarding knowledge of foreign languages; therefore, before that year, students could complete their post-graduate studies without knowing any foreign languages at all. In this sense, the establishment of the norm configured a disruptive emergency situation (FOUCAULT, 2002 [1969]), marking a moment of change within the institution in relation to knowledge of foreign languages, and the emergence of new discourses concerning them (for example, by fostering the creation of language courses or the introduction of books and articles written in other languages in the courses' recommended bibliographies). After 2001, from a diachronic perspective, a new period of stability, regarding foreign language knowledge at the macro level could be identified as no other cross-institutional norm was institutionalized (although authorities from some faculties, who have autonomy, implemented their own requirements concerning foreign language producing disruptive emergency situations also at meso-institutional levels). What is more, it is worth noting that although the institutional norm remained valid throughout the research process, it was revised in 2025 (UNIVERSIDAD DE LA REPÚBLICA, 2025), and the theme reading comprehension is no longer present in the norm, among other changes. As a result, future institutional changes related to English and foreign language teaching are anticipated. [27]

Regarding the tools used to generate new data, interview scripts included open-ended questions and were designed in accordance with DÖRNYEI's (2016) and MERLINSKY's (2006) guidelines (Table 1). Individual (professors') and group (students') interviews were conducted outside the institution via a video conference platform, using the guideline questions detailed in Table 1. Interviews were video recorded, with the interviewees' consent to facilitate their analysis. They lasted an average of forty-nine minutes.

|

Professors' Interview Guideline |

|

Students' Interview Guideline |

|

|

1. What is your experience with foreign languages? |

Extensive; macro, meso, micro levels; past and present representations; future expectations |

1. What is your experience with foreign languages? |

Extensive; macro, meso, micro levels; past and present representations; future expectations |

|

2. Considering your experience, what are the needs of students who take English language courses at the faculty you work in? |

Extensive; macro, meso, micro levels; past and present representations; future expectations |

2. What is your experience regarding foreign language learning at this university? |

Extensive; macro, meso, micro levels; past and present representations, and future expectations. |

|

3. How has your experience teaching English courses at university been? |

Extensive; macro, meso, micro levels; past and present representations; future expectations |

3. How has your learning experience been in the English course the university provides? |

Extensive; macro, meso, micro levels; past, present representations; future expectations |

|

4. Considering expectations regarding students' end of the course outcomes, how do you teach English in the courses you teach? |

Intensive; meso and micro levels; past and present representations; future expectations |

4. What do you think about the topics you have worked with during the university English courses you took? |

Intensive; meso and micro levels; past and present representations; future expectations |

|

5. What problems do you generally face during the English courses you teach? |

Intensive; meso and micro levels; past and present representations; future expectations |

5. What do you think about the resources and materials you used during the English courses you took? |

Intensive; meso and micro levels; past and present representations; future expectations |

|

6. How would you change the course if you could?

|

Intensive; meso and micro levels; future expectations in relation to past and present representations |

6. What activities carried out during the English course do you think will help you throughout your career? |

Intensive; meso and micro levels; future expectations in relation to past and present representations |

|

|

|

7. How would you change the English course if you could? |

Intensive; meso and micro levels; future expectations in relation to past and present representations |

Table 1: Semi-structured interview guidelines and corresponding temporality levels [28]

Student surveys were designed to collect data from a descriptive perspective (DÖRNYEI, 2016; LÓPEZ ROMO, 1998; SCOLLON, 2003) and contained sixteen questions (open and closed, Likert and multidimensional scales and multiple-choice items) that could be divided into three groups: 1. Items to collect demographic data from the surveyed population (micro level of analysis, describing the present situation), 2. questions to understand social representations regarding the importance of knowing foreign languages, in particular English, for their careers and future professions (macro, meso and micro level of analysis, extensive analysis related to past, present and future representations), and 3. questions related to their personal experiences in the English courses they took at the university (meso and micro levels of analysis, understanding present experiences in relation to memories and future representations). All surveys were administered by the end of the courses by sending all students a link to a Google Forms questionnaire via e-mail. There was an overall average response rate of 29.5%. [29]

Regarding sampling methods, intentional sampling (RITCHIE & LEWIS, 2003) was used during interviews, as one student and one professor from each area of knowledge of the institution were selected and invited to participate voluntarily. Furthermore, as sample heterogeneity (DÖRNYEI, 2016) was sought, students from various career paths, with different levels of English proficiency (based on self-identification of levels), and of different genders (as self-identified) were invited to participate. Regarding the sample of student surveys, its size was considered representative (ibid., see also GRASSO, 2006; LÓPEZ ROMO, 1998) as described in the table below.

|

Area of Knowledge (as specified by the university) |

Total Number of Enrolled Students |

Total Number of Students Who Completed the Survey |

Error Margin |

Level of Confidence |

Ideal Size of the Sample |

|

Social and artistic area |

323 |

88 |

9% |

95% |

87 |

|

Technology, nature and habitat sciences area |

19 |

10 |

15% |

80% |

10 |

|

Healthcare sciences area |

96 |

31 |

12% |

90% |

30 |

|

Total |

438 |

129 |

8% |

95% |

99 |

Table 2: Statistical analysis of the sample size, margin of error and level of confidence2) [30]

In addition, classroom observations were carried out to study the scenes of action (SCOLLON, 2003), the places—in this case, the English as a foreign language classroom—where actions occur (re)producing existing discourses. As every moment is unique, and yet embedded in broader contexts, to collect and study on-the-spot data, classroom observation in institutional settings methodologies were used (CID SABUCEDO, 2001; GABBIANI & MADFES, 2006; ORLANDO, 2006). These observations enabled a better description of the object of study as issues concerning its temporality emerged and could be captured on the spur: Knowledge present in different agents' discourses narrated during interviews could be visualized through emergent actions not present in discourses that erupted, showing the complexities of these multidimensional settings. To systematize the observations, structured classroom observation sheets were designed (GIBSON & BROWN, 2009) considering the aim of the study mainly at the meso and micro levels. The observation sheets focused on: 1. Learning objectives, 2. linguistic aims, 3. topics chosen, 4. English language teaching (ELT) approaches used, 5. teaching approaches concerning macro-linguistic development, 6. resources and materials used and, 7. outcomes visualized in relation to the different courses' syllabi. The duration of a single lesson was not considered a suitable criterion to study the way linguistic development is promoted. Hence, the teaching of a complete thematic unit, according to the professors' criteria, became the unit of analysis, whether it took two hours of instruction, a week or a month. Thirteen lessons were observed (of two hours each) in seven of the twenty-three existing English courses (26 hours in total), and at least one course per interviewed professor was visited. Lessons were either video or audio-recorded, with the corresponding authorization, to facilitate their analysis. Data were saved using different formats (written text, audio, and video), and the transcripts were included in the appendices of the doctoral dissertation (CARABELLI, 2023) related to this project. [31]

Ethical concerns and requirements were closely followed, as the research had approval from the Ethical Commission of the Facultad de Humanidades y Ciencias de la Educación, Universidad de la República. The safety and well-being of all participants were guaranteed and always pursued; they were informed about the project's aims, signed consent forms, and all collected data were anonymized. [32]

Throughout the research, reliability and validity criteria were considered (BORÉUS & BERGSTÖRM, 2017; DÖRNYEI, 2016; GIBSON & BROWN, 2009; MEYER, 2003), as not only were research tools piloted (MATOS & PASEK, 2008) and reliable sampling criteria used (Table 1), but the three principles of discourse analysis methodology (SCOLLON, 2003) were also followed: 1. Triangulating data obtained from document analysis, interviews, surveys, and classroom observations, 2. interviewing different actors—professors and students—to capture their perceptions in relation to English teaching at the university where the study was conducted, and 3. conducting lesson observations to compare the discourses and actions that occur in practice with those expressed in documents and by participants in interviews and surveys. [33]

Finally, the research's limitations were related to its scope, given that the object of study is broad. According to the latest student survey, the Universidad de la República has more than 135.000 students;3) therefore, the population involved was very large. Therefore, representative populations and dependencies from each of the three areas of knowledge of the university (social and artistic, technology, nature and habitat sciences, and health sciences) were selected. Nonetheless, the approach inherently led to generalizations that result in some loss of specificity. Despite this, the research is considered highly relevant as no other empirical and observational studies regarding English language teaching were conducted at this university, and it contributes to its understanding while serving as a heuristic guide for future research. [34]

5. Analyzing the Data Collected: Themes, Intertextualities and Interdiscursivities

Heteroglossia in texts exist, and social research is highly complex as it implies multiple interpretations. Nevertheless, as the research methodology chosen has proven valid (Section 4.4), a reliable description of the situation concerning the object of study could be made and several conclusions could be drawn. The data collected were (re)organized, (re)read, and (re)analyzed on various occasions throughout the research process as multiple dimensions were considered. Different color codes were used to categorize data from documents, questionnaires, interview transcripts and classroom observation forms and transcripts. Many tables were produced identifying and grouping themes and subthemes by analyzing lexis and grammatical structures that determine meaning in sentences (GIBSON & BROWN, 2009). Subsequent connections were made across texts and discourses by establishing relationships according to themes and subthemes (JOHNSON, 2015). Once the data were organized, a possible genealogy related to the teaching of English at the university where the investigation took place was traced by establishing meaningful relationships between discourses which show the steady development of the area within the university. The first course was identified, and the presence of other courses was traced in time while addressing the following themes to answer the questions posed in Section 4.1: Which explicit linguistic policies exist or have existed (and which implicit ones emerge through social representations)? Who did/do the policies affect? What functions of English are prioritized? What courses were and are being given, where, how many and what are their aims, justifications, contents and expected outcomes? Which national and international discourses do the institutional ones connect with? [35]

5.1 Defining categories and grouping information

The data were examined using different discourse analysis techniques: Analysis of themes, intertextualities and interdiscursivities. The analysis was guided by the aims and questions presented in Section 4.1, and 31 different tables were created while examining the data (they were included either in the dissertation's body or appendices). Data were categorized by looking for the following aspects: [36]

1. Social and institutional contexts where discourses are (re)produced, interpreted and appropriated (space and time of discourse (re)production; where, when and why were the identified discourse threads (re)produced so as to identify diachronic and synchronic perspectives). The time, place, participants, participants' roles and purpose of the interaction (interview, questionnaire or class observation) were carefully recorded, together with specific data that were categorized as shown in the table below (Table 3). It only displays one row out of twenty-three as one row per identified course was created.

Table 3: English language courses' formal requirements in the different syllabi (adapted from CARABELLI, 2023, p.353, Row 1, Table 1A). Please click here to download the PDF file. [37]

2. Discourse threads that emerged in texts (norms, syllabi, interview transcripts, lesson observation sheets) in relation to themes (identification of themes and subthemes using codes and sub-codes), e.g., by creating categories for discourse threads to group possible teaching approaches, as well as main and specific objectives among the different English courses, as shown in Table 4. As illustrated, some of the information found in the different syllabi falls into several categories and is included in each for subsequent analysis.

Table 4: Categorizing teaching approaches and aims found in course syllabi (adapted from CARABELLI, 2023, p.357, Row 1, Table 2A). Please click here to download the PDF file. [38]

3. Intertextual and interdiscursive connections in present and past discourses (temporality of discourses in relation to the identified themes). Horizontal intertextualities and interdiscursivities were identified, for example, by comparing data from different current course syllabi, as shown in Table 5 in relation to one of the studied categories: Textual genres.

|

Faculty, Center or Institute |

Syllabus Content Related to Textual Genres |

|

1. Faculty 1 (Reading comprehension course) |

- Presentation of diverse textual genres (abstracts, academic web pages, book reviews, calls for presentations, formal e-mails, forms) |

|

2. Faculty 2 (Reading comprehension course) |

- Analysis of diverse types of texts - Studying the English used in textual genres from the legal area: Contracts, bylaws, clauses |

|

3. Faculty 3 (Reading comprehension course) |

- Analysis of authentic academic texts from the Social Sciences area - Analysis of the academic genre. Exploration of formal and discursive characteristics present in academic texts |

|

4. Faculty 4 (Reading comprehension course) |

- Reading comprehension of scientific texts related to the area of dentistry |

|

5. Faculty 5 (Reading comprehension course) |

- Authentic academic and of general-interest texts are used throughout the course |

|

6. Faculty 6 (Reading comprehension course) |

- Authentic academic and of general-interest texts are used throughout the course |

|

7. Faculty 7 (Reading comprehension course) |

- Academic and journalistic texts are used - Formal aspects of different text types: expository, informative, argumentative, and persuasive, are analyzed during the course |

Table 5: Horizontal intertextualities in different reading comprehension in English courses' syllabi (adapted from CARABELLI, 2023, p.365, Table 3A) [39]

As shown in the table, by creating the category and grouping information from different curricular programs according to the theme textual genre, one may clearly visualize horizontal intertextualities (how textual genres are being studied currently in different courses) and interdiscourses (how discourses that are being (re)produced in different faculties share many characteristics). Vertical intertextual connections related to the research topics were mainly uncovered through bibliographic analysis. [40]

By organizing the data in this way, information was compared, patterns were identified, and different conclusions were drawn. In this case, one of the conclusions drawn from all the data gathered (not just the one in Table 5) was that during the different English courses, professors tend to use materials and resources that focus on students' careers and needs. [41]

5.2 Demonstrating methods of data coding and analysis

To illustrate how data were analyzed and treated, some examples, collected with different tools, are shown. The following table presents data collected from questionnaires, showing the degree of agreement of students concerning the statement: "The English course I took at university will benefit my career"

|

Social and Artistic Area |

Technology, Nature and Habitat Sciences Area |

Health Sciences Area |

Total |

|

I fully agree: 51 (57,30%) |

I fully agree: 8 (80%) |

I fully agree: 17 (54,84%) |

I fully agree: 76 (58,46%) |

|

I partially agree: 23 (25,84%) |

I partial agree: 1 (10%) |

I partially agree: 7 (22,58%) |

I partially agree: 31 (23,85%) |

|

I agree to some extent: 12 (13,48) |

I agree to some extent: 0 |

I agree to some extent: 6 (19,35%) |

I agree to some extent: 18 (13,84%) |

|

I partially disagree: 3 (3,37%) |

I partially disagree: 1 (10%) |

I partially disagree: 1 (3,22%) |

I partially disagree: 5 (3,85%) |

|

I fully disagree: 0 |

I fully disagree: 0 |

I fully disagree: 0 |

I fully disagree: 0 |

Table 6: Data from student surveys, closed question, relationship between knowing English and career development (CARABELLI, 2023, p.172, Table 13) [42]

Apart from the closed question shown in Table 6, where students had to mark the option they agreed most with, an open-ended question asking the reasons for their answers was also posed. The arguments provided by students were analyzed and grouped according to themes (identified by theme-related keywords), and the number of recurrences was studied to try to understand which social representations seemed to be more vital, as Table 7 shows.

|

Main Arguments Provided by Students Concerning the Relationship Between English Knowledge and Career Development |

Recurrences |

|

Access to knowledge |

36 |

|

Increased communication possibilities |

25 |

|

Access to bibliography and resources |

16 |

|

Increased studying or working abroad possibilities |

12 |

|

Academic and professional development |

9 |

|

Widening lexical knowledge related to careers |

9 |

|

Increasing work opportunities |

9 |

Table 7: Data from student surveys, open ended questions, main arguments provided by students concerning the relationship between English knowledge and career development (CARABELLI, 2023, p.173, Table 14) [43]

Recurrences in Table 7 were identified as outlined in the cases that follow. For example, a student from the Social and Artistic area stated that she understood that the fact of "having a university that proposes, and impulses English language courses evidences its commitment towards the development of students' professions." The key vocabulary (in italics) used in the sentence demonstrates that the student understands that learning English will result in "academic and professional development" (Argument 5, Table 7). [44]

A student from the social and artistic area mentioned that knowing English "is a benefit because it enables access to different kinds of materials and documents; the fact that English is a shared language enables knowledge and information exchange." Once more, the lexis chosen by the student determined that she was aligned with the argument: "Access to bibliography and resources" (Argument 3, Table 7). What is more, a student from the Health Sciences Areas stated that:

"It is necessary mainly because of the amount of information, such as articles and other literature that can only be found in English. Also, because it opens doors to learning other languages and participating, for example, in courses abroad." [45]

In this case, the student wrote an answer that provided more than one reason for his opinion. Therefore, his position was included both in Argument 3 (Table 7): "access to bibliography and resources," and Argument 4 (Table 7): "Increased studying or working abroad possibilities." [46]

Finally, a student from the technology and nature and habitat sciences area stated that knowing English will help her:

"Learn (as many of the materials used are not available in Spanish, or the most recent versions are only available in English). To publish research that I carry out. To travel and interact with foreign colleagues." [47]

Once again, several arguments were provided, showing the complexity of the topic. In this case, both Argument 1 (Table 7): "Access to knowledge," and Argument 4 (Table 7): "Increased studying or working opportunities" were selected as the student's chosen lexis referred to these meanings, evidencing that her arguments belonged to those two discourse threads. [48]

In addition, as emphasized throughout the paper regarding the plurality of time, the three chosen examples show the complexity of studying temporality because they address simultaneous planes. The discourse threads shown in these quotes evidence simultaneous aspects concerning the past, present and future of English in relation to the students' careers, as shown in Table 8.

|

Discourse Threads Showing Diverse Temporality Planes |

Arguments Provided by Students in Surveys |

|

|

|

Students' quotes

|

"English is a benefit because it enables access to different kinds of materials and documents; the fact that English is a shared language enables knowledge and information exchange."

|

"It is necessary mainly because of the amount of information, such as articles and other literature that can only be found in English. Also, because it opens doors to learning other languages and participating, for example, in courses abroad." |

"Knowing English will allow me to learn (as many of the materials used are not available in Spanish, or the most recent versions are only available in English). To publish research that I carry out. To travel and interact with foreign colleagues." |

|

Researchers' interpretation of discourse threads concerning the past |

The student understands that as many things have been either written or translated to English, knowledge generated in the past may be accessed. |

The amount of texts that have been written or translated into English is enormous. English started to be used in several international events worldwide (for example, in courses). |

Many materials used in the courses the student takes were written in English. Uruguayan researchers published some of their findings in English. People speak diverse languages, yet, English became a bridge tongue. |

|

Researchers' interpretation of discourse threads concerning the present |

Knowing English is a current need as it enables students to access the enormous amount of materials produced in this language. |

Articles and literature in English can be read because the student knows English. He/she may take courses in other countries that imply knowing English. |

Many materials are only available in English as recently published versions have not been translated into the student's first language. |

|

Researchers' interpretation of discourse threads concerning the future |

Students who learn English will be able to access knowledge and exchange information in the future. |

Knowing English facilitates future participation in study abroad programs. |

The student will have to publish some of her research findings in English and if she travels she will have to speak in English to interact with colleagues that do not speak her tongue, Spanish. |

Table 8: Planes of temporality in student survey responses [49]

In relation to the interviews, the data collected through them corroborated the data gathered in surveys. Once more, the given answers facilitated capturing the past, present and future expectations of the research participants. For example, one of the professors stated (Quote 1):

"The learning outcomes ... Well, trying to enable students to ... Well, in reading comprehension courses, to enable them to read original texts they deal with, isn't it? For them to be able to read with the least possible help, like a dictionary ... Well, nowadays, basically with the cell phone, but we want them to be as independent as possible, isn't it? And in the English 3 course, we want them to be able to speak so that they can give a talk in English, isn't it? In a university. Basically, we want them to be able to talk about things related to their profession; and also, to discuss, debate, about a variety of topics, isn't it?" (Professor 1, interviewed July 16, 2021). [50]

In Quote 1 the professor described the students' expected profile upon course completion, which enables the following interpretations concerning temporality in relation to the learning outcomes of the English courses:

|

|

Temporal Analysis of Quote 1's Meaning |

|

Researchers' interpretation of discourse threads concerning the past |

- An enormous amount of texts has been written in English. - At international university congresses, many presentations are delivered in English, alongside other languages, as participants speak diverse native tongues but need a common means of communication, and English became an international bridge language. - Many professionals from diverse linguistic backgrounds use English to discuss and debate various issues at the international level. |

|

Researchers' interpretation of discourse threads concerning the present |

- Students are learning to read and study from texts written in English. - Learners are becoming independent and fluent English readers who rely as little as possible on technology. - Students are learning to discuss and debate ideas in English. |

|

Researchers' interpretation of discourse threads concerning the future |

- Once students graduate, they will have to read several texts in English concerning their careers. - As professionals, they may be required to give presentations in English within university settings. - As graduates, they will need to discuss and debate ideas related to their careers and professions at the international level, often in English. |

Table 9: Planes of temporality in Quote 1, concerning the courses' learning outcomes [51]

In addition, data collected during classroom observations reinforced the idea of facing discipline-specific English courses, where the learning outcomes are closely linked to students' academic fields and future professional goals. Because of this, most of the materials and resources used during lessons were produced by the professors themselves, considering both institutional and students' needs. For example, in one of the lessons observed at the Faculty of Law, the professor worked on certain linguistic aspects that appeared in an English text about Federal law vs. State law. Although the students were not lawyers yet, the professor knew students faced texts related to this area since they entered university, and thus, needed to read them with autonomy. Different aspects of the students' and institutions' past, present and future, converge in every lesson, making them meaningful and relevant in relation to specific needs and interests. In this regard, another important finding was that the socio-cultural functions of the English language—particularly those related to access and production of knowledge—are prioritized at the university level. This contrasts with previous research conducted in the press and other sectors of Uruguayan society (CANALE & PUGLIESE, 2011; LÓPEZ, 2013) which highlighted the predominance of utilitarian functions of English, especially in contexts such as work, technology, diplomacy, sports, and business. [52]

6. Overlapped and Multilayered Findings

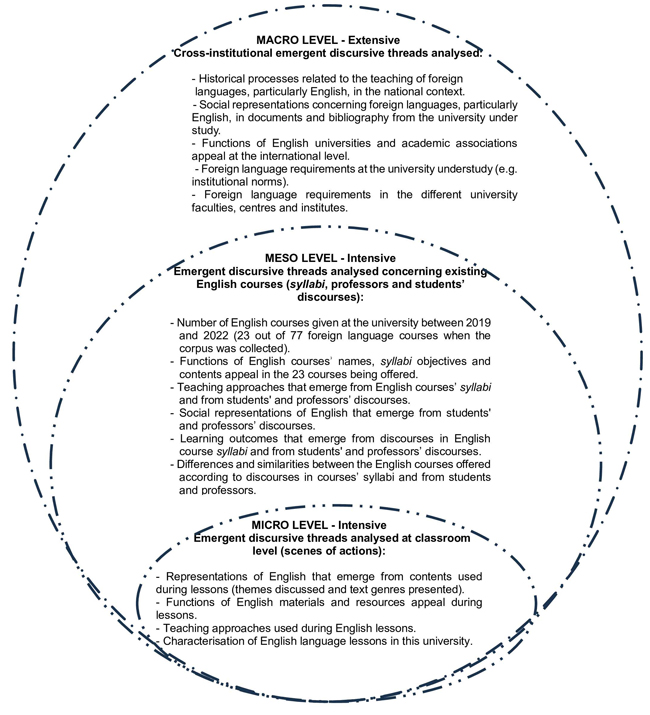

With the data presented in this article, minimal compared to the amount collected during the investigation, I illustrate the complexity of studying discourses that are heteroglossic and involve a plurality of times, as present, past and future are intertwined and interconnected at different levels of discourse. To show this in relation to the overall findings, in Figure 1, I present the discursive threads untangled from the discursive knots at the different temporal and institutional levels.

Figure 1: Discursive threads in the macro, meso and micro levels of the discursive knot concerning the teaching of English

at the university where the research took place (adapted and translated from CARABELLI, 2023, p.226, Figure 1) [53]

In Figure 1, I illustrate how discourse threads connect throughout the different levels. It represents how discourses that, at first, may seem unrelated and happening in different places (at different institutional levels), and at different times, are affecting and depending on each other. Innumerable discourses occur at the macro cross-institutional level, primarily in relation to policies and regulations, and once produced, they exhibit certain stability over time, as the rhythm of change at this macro level sometimes tends to be slower. Nevertheless, the discourse threads within this level affect discourse threads in the other two layers through intertextualities (vertical and horizontal) and interdiscursivities (in a top-down way), and vice versa, the discourses in the micro and meso levels affect the discourse threats in the macro level (in a bottom-up way) as actions produced by agents (professors, researchers, deans) in micro levels also produce effects at the macro levels. It must be noted that, although the macro level may show a degree of relative stability, disruptive emergency situations—such as the passing of a new norm or law (such as the norm created in 2001 and modified in 2025 at the referred university UNIVERSIDAD DE LA REPÚBLICA, 2001, 2025) mentioned in Sections 4.3 and 4.4)—inherently provoke many changes, resulting in both the discontinuation and production of many discourses. [54]

To understand these processes, temporal considerations across different institutional levels must be uncovered through complex qualitative inquiry. To illustrate this, the way in which the following discursive thread unfolds simultaneously across multiple level is described. Since English lessons have been given at this university almost since its foundation, there is a tradition regarding the teaching of English in Uruguay and in the institution, and at least one explicit linguistic policy concerning foreign language knowledge has been implemented (extensive macro level); thus, many English professors work at this university and several courses have been created (intensive meso level), which implies that many university students attend English lessons (the scenes of action), and professors teach the target language using certain approaches and (re)producing certain functions of the language in relation to the context they are teaching at the intensive micro level. This temporal, contextual, multilayered reality reveals how multiple discourse threads dynamically overlap in relation to the configuration of the object of study. How past, present, and future coexist had to be addressed to describe what the process of teaching English at this university implies regarding the three discursive knots and the research aims (see Section 4.1) in relation to international, national and institutional policies, access to knowledge, knowledge production and language education. Moreover, the discourses surrounding the object of study, dynamically shaping and changing its presence, happen even while researchers attempt to apprehend its reality. Changes are constantly happening within the plurality of times, and things are varying in unknown and imperceptible ways. Hence, although the research aims were hermeneutically fulfilled, and the ethnography of discourse enabled a detailed description of different aspects concerning English language teaching at the chosen university, additional research in the field will enable further understanding. [55]

Temporality is inherent to existence; yet it is not related to infinite mathematical series or astronomical factors related to regular notions of time. It implies complex, dynamic, simultaneous and overlapped historical and in-time actions (discursive and non-discursive) that affect each other, configuring the existence of subjects. Considering this—together with a variety of theories from the discourse analysis field—and with the aim of apprehending and describing, hermeneutically, different aspects concerning the teaching of English at a specific university situated in Uruguay, an ethnography of discourse was carried out. Three pre-identified discursive knots that configure this university (BEHARES, 2011) were used to delimit the research aims: 1. The political/university knot, 2. the knowledge/know-how knot, and 3. the teaching knot) and research questions (Section 4.1) could be answered. The findings referred to aspects at macro, meso and micro levels and included: Describing, from a historical perspective, the vitality and functions of the English language at international levels, outlining the situation regarding English and other foreign language usage and teaching in Uruguay and at the university where the research took place, detecting explicit and implicit linguistic policies at national and institutional levels, identifying existing English courses at the university, and analyzing their syllabi and existing justifications, contents, teaching approaches and expected learning outcomes. Some of the most important findings were that: 1. Most of the twenty-three English courses given in different university dependencies during the window period, prioritized the development of reading comprehension skills; 2. professors prepared materials and lessons focused on institutional and students' disciplinary needs; and, 3. that the socio-cultural functions of English related to access and production of knowledge are hierarchized in the different university courses. [56]

Bearing in mind JÄGER's (2003) theory regarding the existence of complex discursive knots and the elaboration of research dispositives to unveil discursive threads at different institutional layers, varied and specific research tools (surveys, semi-structured interviews and classroom observations) were designed, tested and used to collect valid and reliable data that would enable the accomplishment of the complex task. The methodology chosen was adequate as it enabled the tracing of a first cartography of the teaching of English at the chosen university (a public university in Uruguay). The complex multilayered data analysis consisted of, among other things, examining data: 1. Diachronically, or extensively (at macro and meso levels), to capture moments of change and stability (such as the creation of new English courses); and to identify disruptive emergency situations that may have altered existing orders of knowledge, power or discourse, in relation to the presence and aims in the institution (such as the appearance of the postgraduate norm (UNIVERSIDAD DE LA REPÚBLICA, 2001, 2025) in relation to knowledge of foreign languages; and 2. synchronically, or intensively (at meso and micro levels) to capture changes within the object of study itself, in the scenes of action (e.g., concerning the curricular contents being taught in the different courses). [57]

The discursive knots could be untangled, and different cross-institutional discursive threads were identified in relation to their context and temporality. These shed light on different implicit intertextual, interdiscursive and historical connections that occur simultaneously through discourses and actions of multiple agents (authorities, policy makers, professors, students and international scholars) at different levels: International, national, and at the university, in the different faculties, centers and institutions, and in the classrooms. Due to the chosen approach, and considering that social research is never exhaustive, the aim of describing the process of teaching English at Uruguay's main public university could be fulfilled. English courses have been offered at this university almost since its foundation, and many courses are currently being taught (twenty-three different ones during the research window period). The socio-cultural functions of this language that are prioritized in them show that at this university, knowledge of English is considered highly relevant to access and produce knowledge. The research also provides a heuristic guide for future visualizations of changes within this specific field and identification of new areas of research. [58]

1) All translations from non-English texts are mine. <back>

2) The statistical analysis of the sample, margin of error and confidence level was made by using the formula: n = Z2. p. q. N / NE2 + Z2. p. q. Where, n = size of the sample, Z = level of confidence, N = Population - Census, p = probability in favor, q = probability against and E = estimation error. <back>

3) https://udelar.edu.uy/portal/institucional/ [Accessed: August 12, 2025]. <back>

Aristotle (1957 [circa 350 B.C.]). Physics books I-IV (trans. by W.E.J. Wicksteed & F.M. Cornford). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Bajtín, Mijaíl (1979). Estética de la creación verbal [The aesthetics of verbal creation]. México: Siglo XXI.

Barrios, Graciela (2015). Diversidad lingüística, ma non troppo [Linguistic diversity, but not too much]. In Facultad de Humanidades y Ciencias de la Educación (Ed.), 70 años de humanidades y ciencias de la educación [70 years of humanities and education sciences] (pp.48-49). Montevideo: FHCE/Universidad de la República.

Behares, Luis Ernesto (2011). Enseñanza y producción de conocimiento. La noción de enseñanza en las políticas universitarias uruguayas [Teaching and knowledge production. The notion of teaching in Uruguayan university policies] Montevideo: CSIC / Universidad de la República.

Bertolotti, Virginia & Coll, Magdalena (2014). Retrato lingüístico del Uruguay. Un enfoque histórico sobre las lenguas en la región. [Linguistic portrait of Uruguay. An historical approach to languages in the region]. Montevideo: FHCE/CSE/Universidad de la República.

Bialakowsky, Alejandro (2017). La temporalidad y la contingencia en el "giro de sentido" propuesto por las perspectivas teóricas de Giddens, Bourdieu, Habermas y Luhmann [Temporality and contingency in the "turn of meaning" proposed by the theoretical perspectives of Giddens, Bourdieu, Habermas and Luhmann]. Sociológica, 32(91), https://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0187-01732017000200009 [Accessed: March 8, 2025].

Bond, Bee (2020). Making language visible in the university. English for academic purposes and internationalisation. Bristol: Multilingual matters.

Boréus, Kristina & Bergström, Göran (2017). Analyzing text and discourse. Eight approaches for the social sciences. London: Sage.

Braun, Virginia & Clarke, Victoria (2021). The ebbs and flows of qualitative research: Time, change, and the slow wheel of interpretation. In Bryan C. Clift, Julie Gore, Stefanie Gustafsson, Sheree Bekker, Ioannis Costas Battle & Jenny Hatchard (Eds.), Temporality in qualitative inquiry. Theories, methods and practices (pp.22-38). Milton Park: Routledge.

Brovetto, Claudia (2017). Language policy and language practice in Uruguay: A case of innovation in English language teaching in primary schools. In Lía D. Kamhi-Stein, Gabriel Díaz Maggioli & Luciana C. de Oliveira (Eds.), English language teaching in South America. Policy, preparation and practices (pp.54-74). Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

Brovetto, Claudia & Kaplan, Gabriela (2011). Language and culture: How do Uruguayan teachers of English connect to the English-speaking world?. In ANEP (Ed.), 3 FLA. Tercer foro de lenguas ANEP [Third ANEP language forum] (pp.167-176). Montevideo: ANEP/CODICEN.

Calvet, Louis-Jean (1997 [1996]). Las políticas lingüísticas [Linguistic policies]. Madrid: Edicial.

Canale, Germán (Ed.) (2011). El inglés como lengua extranjera en Uruguay [English as a foreign language in Uruguay]. Montevideo: Tradinco.

Canale, Germán (2013). Adquisición de la fonología. El inglés como lengua extranjera en estudiantes montevideanos. [Acquisition of phonology. English as a foreign language among students from Montevideo]. Montevideo: CSIC/Universidad de la República.

Canale, Germán (2015). Reseña de "Retrato lingüístico del Uruguay". Un enfoque histórico sobre las lenguas en la región [Review of "Linguistic portrait of Uruguay". An historical approach to languages in the region]. In Alcides Beretta (Ed.), Revista de la Facultad de Humanidades y Ciencias de la Educación (pp.117-122). Montevideo: Universidad de la República.

Canale, Germán (2018). A construção da aula de inglês como língua estrangeira por meio de dois artefatos curriculares [The construction of the English as a foreign language class through two curricular artifacts]. Linguagem & Ensino, 21, 97-119, https://periodicos.ufpel.edu.br/index.php/rle/article/view/15132 [Accessed: March 8, 2025].

Canale, Germán & Pugliese, Leticia (2011). "Gardel triunfó sin cantar en inglés": discursos sobre el inglés en la prensa uruguaya actual ["Gardel succeeded without singing in English": Discourses concerning English in current Uruguayan press]. In Germán Canale (Ed.), El inglés como lengua extranjera en el Uruguay [English as a foreign language in Uruguay] (pp.17-33). Montevideo: Cruz del Sur.

Carabelli, Patricia (2012). El interculturalismo en educación: reflexiones desde el aula de inglés [Interculturalism in education: Reflections from the English classroom]. In Laura Masello (Ed.), Lenguas en la región. Enseñanza e investigación para la integración desde la Universidad [Languages in the region. Teaching and research for integration from the university] (pp.19-30). Montevideo: FHCE/Universidad de la República.

Carabelli, Patricia (2021). English for academic purposes related to dentistry: Analyzing the reading comprehension process. Profile: Issues in Teacher's Professional Development, 23(2), 51-66, https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v23n2.86965 [Accessed: August 12, 2025].

Carabelli, Patricia (2023). El anudamiento discursivo en torno a la enseñanza del inglés como lengua extranjera en la Universidad de la República [The discursive knot concerning English language teaching as a foreign language in the Universidad de la República. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, linguistics, Facultad de Humanidades y Ciencias de la Educación, Universidad de la República, Montevideo, Uruguay.

Cid Sabucedo, Alfonso (2001). Observación y análisis de los procesos de aula en la universidad: una perspectiva holística [Observation and analysis of the classroom processes at university: A holistic perspective]. Enseñanza, 19, 181-208, https://gredos.usal.es/bitstream/handle/10366/70723/Observacion_y_analisis_de_los_procesos_d.pdf;jsessionid=1D1506AAE261431636E485A3B55FB24B?sequence=1 [Accessed: March 8, 2025].

Clift, Bryan C.; Merchant, Stephanie & Francombe-Webb, Jessica (2021). Time as a conceptual methodical device. Putting time to work in gendered sporting moments, memories, and "experience". In Bryan C. Clift, Julie Gore, Stefanie Gustafsson, Sheree Bekker, Ioannis Costas Batlle & Jenny Hatchard (Eds.), Temporality in qualitative inquiry. Theories, methods and practices (pp.93-110). Milton Park: Routledge.

Couchet, María Mercedes (2012). Lo elemental en el aprendizaje de una lengua extranjera: la perspectiva de los estudiantes de inglés en la universidad [The basics of learning of a foreign language: English students' perspectives at university]. In Laura Masello (Ed.), Lenguas en la región. Enseñanza e investigación para la integración desde la universidad [Languages in the region. Teaching and research for integration from the university] (pp.172-186). Montevideo: FHCE/Universidad de la República.