Volume 26, No. 2, Art. 14 – May 2025

"Look it up on the Web": Approaches to the Analysis of Clip-Based Knowledge Communication

Bernt Schnettler, Tom Kaden & Lisa Voigt

Abstract: Knowledge, especially useful knowledge, is increasingly disseminated and acquired through short videos clips circulating on the internet or distributed via social networks. This contributes to a significant transformation of individual and social stocks of knowledge. Digital media proliferation and its subsequent pervasive utilization have served as crucial catalysts for this development with the boundaries increasingly blurring between everyday contexts, work environments, and institutional spheres. This has lasting consequences for the social distribution of useful knowledge. These clips thus promote a shift away from the previously dominant oral and text-based forms of knowledge-sharing, which are complemented, and sometimes even completely replaced, by audio-visual formats. Clips serve as easily accessible and ubiquitous sources of knowledge, used both by laymen to solve their everyday problems and by experts seeking swift assistance for specific difficulties. Focusing on Instagram, in our ongoing study, we examine clip-based audio-visual communication from a perspective grounded in the new sociology of knowledge. We use a combination of qualitative methods, namely genre analysis as a corpus-based method and sociological hermeneutics as a case-analytical approach. With this research, we aim to provide results that contribute to the overarching sociological question of how social stocks of knowledge change through visual communication.

Key words: visual sociology; social media; sociology of knowledge; social stock of knowledge; Instagram; YouTube; communicative constructivism; genre analysis

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. Audio-visual Communication and the Changing Social Distribution of Useful Knowledge

2.1 The social distribution of useful knowledge

2.2 Genre analysis and communicative constructivism

2.2.1 Analyzing communicative genres

2.2.2 Visualization of knowledge communication

2.3 Sociology of digitalization

2.4 Instagram-clips as our research object

2.5 Research on knowledge communication via video clips in social media

3. Data and Analytical Approach

3.1 Methodological challenges

3.2 Research example

4. Preliminary Conclusion and Desiderata for Follow-Up Research

In this paper, we address a problem related to the social distribution of knowledge. We start with the observation that the modalities through which we acquire and disseminate knowledge are undergoing substantial changes in the contemporary era. This phenomenon can be attributed to a profound shift in the currently prevailing communicative modalities. In the 21st century, new audio-visual forms of communication have emerged alongside traditional verbal and written modalities, contributing to a substantial transformation of the communicative "budget" (LUCKMANN, 1988, p.282),1) understood as the totality of all societal forms of communication.2) This development is significantly influenced by the pervasive use of digital platforms and social media which, in addition to face-to-face communication, account for a rapidly expanding proportion of the overall human communication modalities. It would be a gross oversimplification to claim a devaluation of direct communication in favor of mediated forms, as the latter do not entirely replace existing verbal and written communication modalities. Instead, they complement and add to the existing ones. Nonetheless, substantial shifts in the communicative budget are evident. In light of these considerations, in the present study we seek to elucidate the primary facets of visual knowledge communication catalyzed by clip communication. [1]

In our current research, we focus on video clips that can be referred to as a "minor film genre." We concentrate on the commonly used, asynchronous forms3) of short video sequences in everyday life. Such clips are recorded, shared, or uploaded online for various purposes and are viewed by the most diverse audiences. Their forms and functions are equally varied, and the distinctions between knowledge transmission in terms of information delivery and persuasion, between the need for communication and self-presentation, and between the pursuit of recognition or acknowledgment—in short, between aesthetics, entertainment, or informational needs—are not always clearly delineated. Therefore, we turn our attention to a specific aspect related to the suitability of video clips as a means of communication of knowledge. [2]

We are interested in all types of knowledge. However, for the sake of clarity and concision, we will center here on one subtype only. In this study, our primary emphasis is on content categorized as general knowledge, or more precisely, useful knowledge and knowledge of recipes. In the ambit of the new sociology of knowledge, a distinction is made, both typologically and concerning its social distribution, between "general knowledge that is evenly distributed, and specialized knowledge that exhibits a role-specific, and thus uneven distribution" (SCHUTZ & LUCKMANN, 1973, p.312). Furthermore, in terms of its genesis and structure, we can distinguish different levels of complexity: "Between the basic elements of the stock of knowledge and its specific component contents, routine knowledge occupies a middle position" (p.105). This routine or habitual knowledge can be further categorized into three forms: Skills are defined as "habitual, functional unities of bodily movement (in the broadest sense) as have built upon the fundamental elements of the usual functioning of the body" (p.107), such as breathing and swallowing. Useful knowledge, in turn, constitutes the subsequent level of complexity: "There is a province of habitual knowledge which concerns skills, but which no longer really belongs to the usual functioning of the body. We will term this useful knowledge" (ibid.). This category encompasses a wide range of activities, from the rudimentary task of chopping wood to the more complex undertaking of playing the piano. Knowledge of recipes, finally, "is indeed no longer associated with the basic elements of the stock of knowledge immediately concerning skills. But it is still 'automated' and 'standardized'" (ibid.). The ensuing discussion will primarily focus on the domains of skills and knowledge of recipes, asking how the dissemination of these forms of knowledge changes through clip communication. [3]

We are witnessing that video clips are increasingly used as mediated vehicles for knowledge dissemination and acquisition. However, a considerable scope of forms exists, from simple, quickly recorded, and rapidly circulated fragments of raw footage to very complex, elaborately produced, edited, and highly estheticized short films. Just as their forms vary widely, clips are used for very different types of knowledge. This ranges from simple tips, tricks, and instructions for recurring everyday problems (such as cleaning the drain—see below—, frying an egg, or sewing a button) to the search for solutions to specific, less frequently occurring technical problems, such as "Replacing the ink cartridge for the Epson WF 2760," where one can draw on video clips to find a solution. More complex variants include clips offering advice on issues related to highly specific areas of knowledge, such as medical questions like the search for "Autistic Spectrum Disorder in Trisomy 21" or legal problems as "Compliance with the withdrawal period in distance selling." In any case, what is presented as "knowledge" through a clip is conveyed in a sequentially developing audio-visual format particularly suitable for step-by-step solutions and indexical explanations—following the credo: "Show, don't tell." [4]

This raises questions that we will examine from the perspective of the sociology of knowledge and culture, for example, to what extent do such video clips reinforce the idea of supposed universal availability and unrestricted access to knowledge as an influential guiding fiction for action in everyday life? (see "Georgina's law," Section 4.3, §62). We address these questions as part of an ongoing research project, and the current article is based on our recent investigations into visual knowledge communication with video clips initiated at the University of Bayreuth. Using a combination of qualitative methods, we include analyses of fragments from our growing corpus of videographic data. In our study, we use a combination of ethnomethodological sequence analysis with the analysis of communicative genres and sociological hermeneutics. In terms of methodology, we thereby explore how to blend hermeneutical analysis and genre analysis when analyzing web-based video data. The objective of this research is to provide insights into the ways in which digital visual media impact the social distribution of useful knowledge. [5]

We will commence by examining audio-visual communication and its impact on the social distribution of useful knowledge, emphasizing the shift from text-based to clip-based knowledge dissemination (Section 2.1). Subsequently, we will introduce our theoretical framework, focusing on the sociology of knowledge, genre analysis, and communicative constructivism (Sections 2.2-2.3). This will be followed by an analysis of Instagram as a platform for knowledge communication and the role of short video clips in shaping social interaction and information dissemination (Section 2.4). We will then review existing research on video-based knowledge communication in social media and identify gaps in the current literature (Section 2.5). Thereafter, we will outline our methodological approach, including corpus-based genre analysis and case-based sociological hermeneutics while discussing key methodological challenges in studying digital video content (Sections 3-3.1). We focus on the sequential and multimodal structure of video clips, exemplified by an in-depth examination of an Instagram reel providing cleaning instructions (Section 3.2). This leads to a discussion of the broader implications of clip-based knowledge dissemination, particularly concerning knowledge accessibility, social legitimation, and changing expert-layperson dynamics. Finally, we conclude by summarizing our findings and outlining future research directions in the study of digital knowledge communication (Section 4). [6]

2. Audio-visual Communication and the Changing Social Distribution of Useful Knowledge

2.1 The social distribution of useful knowledge

It is necessary to further elucidate the conceptual and theoretical framework within which this research is embedded. We assume that the social distribution of knowledge is of central importance to social theory because the distribution of knowledge concerns core aspects of the structure and articulation of modern societies. The structure and articulation of the social stock of knowledge in a given society are considered crucial factors in determining the society type and serve as the basis for comparing different societies. The question arises as to how the subjective stocks of knowledge (SCHUTZ & LUCKMANN, 1973) relate to the social stocks of knowledge. To answer this question, it is essential to consider both its content and form. More specifically, this brings the communicative construction of knowledge (KNOBLAUCH, 2020) into focus. [7]

In this section, we will examine the role played by the increasing use of audio-visual forms in the area of informal knowledge communication. We cannot consider the entire breadth of the whole social stock of knowledge because a comprehensive examination would exceed our available scope. Visual and audio-visual forms of communication are currently employed in nearly all domains of formal and informal knowledge distribution. At the outset, the formal variants of visual knowledge communication will be set aside, although there is an increasingly prevalent use of visual and audio-visual forms of knowledge in the field of education.4) Instead, we will take an exemplifying look at the possible spectrum of clip-based knowledge communication. This exploration aims to provide initial thoughts to answer the question of the specific changes arising from the clip-fueled visualization of knowledge communication for the structure of social knowledge distribution. [8]

With our ongoing research questions and the guiding interest of our study we focus on the transformations caused by audio-visually communicated useful knowledge. In our project, we analyze short video clips that convey such practical knowledge graphically and vividly, and we aim to clarify how its prolific usage may modify the social distribution of knowledge. [9]

Questions revolve around changes in societal knowledge distribution. Does it lead to a democratization of knowledge? Does a delegitimization of expertise occur? Does it affect expert-lay relations and, if so, to what extent? These questions cannot be fully answered yet due to the nascent stage of empirical research in this domain. While video clips are becoming increasingly prevalent in the realm of online knowledge communication, the present study primarily focuses on qualitative shifts. Through video clips, performative visuality in knowledge communication becomes a ubiquitous mass phenomenon. The spectrum of clips as vehicles for societal knowledge communication is correspondingly broad, ranging from basic everyday knowledge to highly specific specialized domains of expert knowledge. [10]

Building on a description of clip-based knowledge visualization, we 1. explore how the sequentiality of the clips favors the transmission of processual knowledge, considering the dimension of two different temporalities, internal and external. The sequentiality of the video clip refers to the domain of internal temporality, while the domain of external temporality encompasses the contexts of production and reception. Both contexts somehow envelop the core of internal temporality, which previously played the pivotal role when forms of knowledge transmission remained tied to co-presence in social situations.5) Furthermore, we 2. analyze the shifts occurring in the stocks of knowledge themselves, i.e., at the level of objectifications, and how these affect typical configurations of actors (e.g., "seekers" vs. "advisers"). Finally, we 3. ask how, in terms of normativities, the knowledge disseminated through clips is established, legitimized, and competes or is involved in digital evaluative logics against "canonical" disciplinary or specialized stocks of knowledge. [11]

It should be noted that the visualization examined here does not solely relate to aspects of pictoriality. The examined development occurs within a broader cultural transformation that is commonly referred to as "digitalization."6) However, the fact that knowledge is disseminated at an accelerated pace through platform communication over technical networks is only marginally relevant. Rather, for a sociological examination rooted in the sociology of knowledge and culture, it is imperative to consider the tensions between digitalization and re-analogization. This is evident, for example, in life hacks or repair tutorial clips that empower users to repair devices with their own hands, which otherwise could only be fixed by specialists. [12]

Similarly, the ubiquitous distribution and relatively low-threshold accessibility of useful knowledge can generate conflicts oscillating between "knowledge democratization" and "digital expropriation." There is an evident elective affinity between the notion of a "democratization of knowledge" in the sense of free availability, and the open access movement in science. Nevertheless, while open access pertains to scientific knowledge only, the former encompasses a more extensive scope, extending to a wider array of knowledge types. The prospect of digitalization is frequently linked to the facilitation of access and the assurance of information availability for all individuals. [13]

We use the term "digital expropriation" to refer not only to the risks of knowledge being covertly extracted or systems profiting from our inputs but, more fundamentally, to the loss of control over the very tools through which we must operate in the digital sphere. Put succinctly, new software versions routinely devalue our existing user expertise and coerce us to engage in unwanted learning efforts. In this sense, digitalization does not merely entail an increase in the volume, density, and acceleration of communicative exchanges but also a broader shift from textual to visual modes of representation, as well as from spoken and written language to more visual and acoustic forms of communication. In asserting that "[t]he presence of the image is primarily asemic," SRUBAR (2017, p.421) alluded to communication transcending the conventional limits of sign usage. We argue that audio-visual clip communication facilitates the advancement of expression and comprehension beyond conventional sign usage by incorporating asemic or pre-semic forms of understanding. [14]

2.2 Genre analysis and communicative constructivism

Our analyses are based on the intensive collaboration between sociological research and pragmatic linguistics at the University of Bayreuth since 2009, particularly in the field of multimodal conversation analysis. The academic hub for this collaboration is our video analysis laboratory, where data sessions have been held weekly since 2011. Within this setting, an interpretive culture has evolved, drawing on genre analysis and ethnomethodology. We combine approaches from communicative constructivism (KNOBLAUCH, 2020) with sociological hermeneutics (SOEFFNER, 2004).7) [15]

The structure and social distribution of knowledge are established themes in phenomenologically grounded social theory (SCHUTZ & LUCKMANN, 1973). As LUCKMANN (1984) has argued, significant modifications in the structure of individual and social stocks of knowledge can be observed as communication changes from direct to indirect, mediated forms. The proliferation of electronic online communication has been instrumental in precipitating these transformations. This applies to both the subjective acquisition of knowledge and its individual and social use, profoundly impacting societal knowledge distribution as a whole. [16]

2.2.1 Analyzing communicative genres

The theory of communicative genres asserts that communication genres are historically and culturally specific, socially constructed solutions to communication problems that address the intersubjective experiences of the lifeworld (LUCKMANN, 1986). Of course, not all human communication follows pre-existing patterns. But in contrast to "spontaneous" communicative acts, communicative genres arise to deal with recurring communicative problems. These patterns and forms, which are typically embedded within institutional contexts, facilitate both mutual understanding and interpretation. They provide a framework for orientation within the rapidly changing flow of communication. Following LUCKMANN (1986), we refer to these forms and patterns as communicative genres. Communicative genres shape and pre-organize communicative action, and they constitute "the more or less self-evident and binding foundation for the initiation of 'natural' human organisms into an 'artificial' historical-social world" (LUCKMANN, 2002, p.158). By guiding interactions along more or less predetermined patterns, genres help synchronize and coordinate participants' interactions and mutual activities, directing them into habitual, reliable, familiar, and predictable trajectories (KNOBLAUCH, 1995, pp.162ff). [17]

Based on these assumptions, a corresponding qualitative method was developed, known as genre analysis (GÜNTHNER & KNOBLAUCH, 1995). Genre analysis is fundamentally interpretative and inherently comparative. This corpus-based method of data collection is used to empirically examine the structure of communicative processes at three distinct levels: Internal, external and the intermediate level of interactive realization. (For a recent comprehensive overview of genre analysis, see WILKE [2022, Chap.3], and the contributions in KNOBLAUCH & SINGH [2023].) [18]

2.2.2 Visualization of knowledge communication

Within sociolinguistic and social scientific genre research, we build on works in visual sociology of knowledge (RAAB, 2008) and visual knowledge (LUCHT, SCHMIDT & TUMA, 2013). Our research is closely related to studies on AI-supported or audio-visual knowledge construction (PELTZER, 2021; RAAB, 2023), the everyday integration of the intertwining of digital communication and face-to-face activities analyzed in neighborhood contexts (MÉLIX & CHRISTMANN, 2022; SINGH & CHRISTMANN, 2020), and social uses of online media communication (AYASS, 2014) as well as interaction and visuality. Direct connections also emerge with research on the transformation of communicative budgets (MEYER & QUASINOWSKI, 2022) and digital relationship initiation (as part of the theory of social worlds, see ZIFONUN, 2016), to which our analysis can contribute complementary results. The empirical analyses are placed in the broader context of an empirically grounded sociological reconstruction of the transformation of current forms of sociality under the influence of processes of digitalization and de-digitalization (ENDRESS, 2017). [19]

We discuss a problem addressed by communicative constructivism (KNOBLAUCH, 2020), concerning the visualization of knowledge (see SCHNETTLER, 2007, 2017). Visualizations have become an integral part of everyday life and are widely used in ordinary social communication. The focus is on examining how visualizations intervene in the interactions between individuals and how they enable and foster new forms of interaction, social relations, and knowledge (MÜLLER & SOEFFNER, 2018). The approach pursued here is related to the theory of communicative genres (KNOBLAUCH & SCHNETTLER, 2010) and the sociology of visual knowledge (SCHNETTLER, 2007). We have presented some initial empirical analyses on this topic, including the visualization of knowledge communication with performative genres (SCHNETTLER & KNOBLAUCH, 2007), the analysis of short image clips (SCHNETTLER & BAUERNSCHMIDT, 2019) and studies on the role of visual rhetoric in processes of social transformation (SCHNETTLER, SÁNCHEZ SALCEDO, DIESSELMANN & HETZER, 2021). [20]

2.3 Sociology of digitalization

WEBER-SPANKNEBEL (2023) examined the phenomenon of sociality in the context of technology and digitality, incorporating FINK's theory (1970). Sociality is understood as a culturally shaped, experiential, intergenerational, and educational practice that focuses on sharing relationships with the world. The author highlighted the creative nature of technology from a social phenomenological perspective and emphasized digitality as a transformative process with specific characteristics. Clear distinctions between digitality and digitization are cautioned against, with digitality considered a general dimension enabling altered perceptions of self and the world. KLEMM and STAPLES (2018) also contemplated digitization. They discussed the integration of digital media into various life domains and stressed the gap between theoretical debate and practical integration. The authors outlined five considerations, including 1. the visualization of societal interaction orders through digital transformation, 2. the reinforcement of embodied experiences of the relationship between self and sociality through digitization, 3. advocating for an unbiased observation of digitization effects to avoid premature judgments, 4. using sociological classics as starting points for investigating the societal effects of digitization, and 5. the necessity of refraining from an artificial outdoing competition, as societal changes are not yet fully realized. [21]

SEYFERT (2024) focused on digital transformation and the need for a fundamental redesign of sociological theories. His theory of algorithmic sociality (TaS) is introduced to capture the diverse and heterogeneous forms of relationships in times of digital transformation. In TaS, the mutual relationship between algorithmic objects and human subjects, is emphasized as a central aspect. He presented this theory as a basis for empirical investigations and aimed to strengthen sociology in researching society in times of digital transformation. [22]

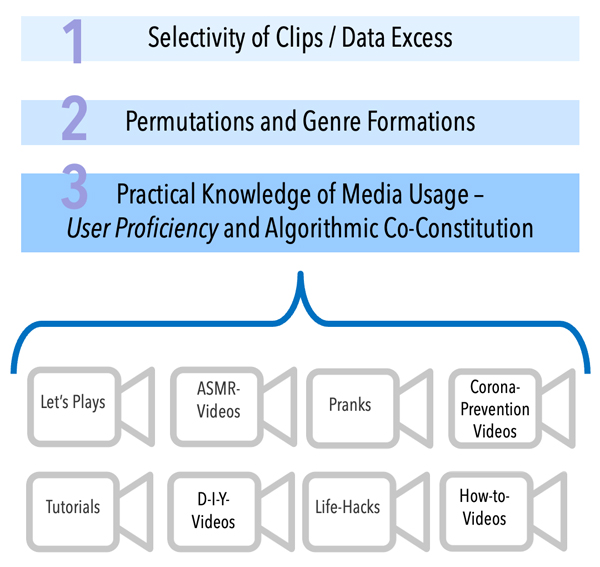

As an interim conclusion, it can be noted that despite the breadth of the research topic, research regarding platforms like Instagram is scarce in comparison to its societal impact. While all authors explore different aspects of digital transformation and its impacts, the examination of the transformation of sociality through audio-visually communicated knowledge still has considerable research gaps. [23]

In the field of the sociology of digitalization, general social-theoretical accounts emphasize the category of knowledge and its effects on digitalization. According to NASSEHI's perspective (2024), digitalization involves the emergence of patterns in data through the quantification of various social facts. It has profound and society-changing effects, primarily manifested in the understanding of various regularities. When reintegrated into social life, these regularities impact users and producers of digital communication infrastructure, such as social media platforms. [24]

From a critical sociological standpoint, ZUBOFF's (2019) account of platform capitalism highlighted knowledge, specifically the disparity between user and platform owner knowledge, as a key factor contributing to widespread social inequality and the potential for manipulation. This perspective was shared by other proponents of the so-called "techlash" literature, including BRIDLE (2018) and LANIER (2013). [25]

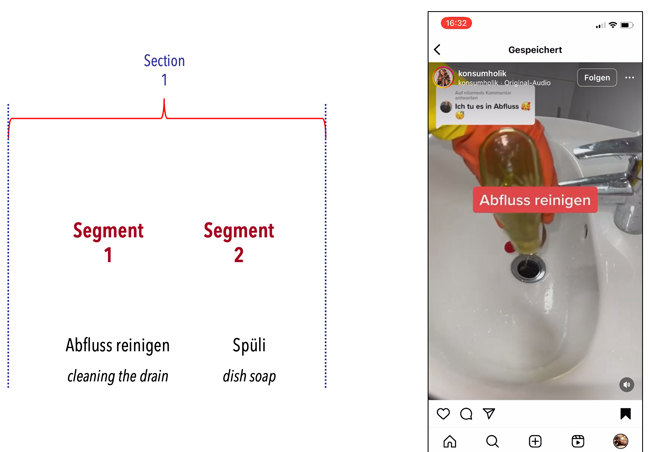

Beneath the overarching social theory and society-wide impacts of digitalization, numerous studies focused on the effects of digitalization on knowledge structure, development, and distribution across various social fields. Within sociology itself, digitalization instigates multiple shifts, as articulated by the author of a textbook on digital sociology:

"The digital, then, presents an essential new site for the negotiation, contestation, and imagination of different ways of understanding society. It raises many troubling but important and relevant questions: Who is capable of social inquiry? Who owns the means of its production and distribution? What constitutes usable data? What techniques of intervention can sociology employ? What relationships between researchers and research subjects should we strive for?" (MARRES, 2017, p.40). [26]

This questioning of established knowledge orders through digitalization was mirrored in various other social fields. Summarizing the state of research on the public sphere and its interlinkage with democracy, politics, and media, NEUBERGER et al. (2023) identified an epistemic crisis brought about by media differentiation, with digital media playing a significant role. Other studies compiled a growing body of literature focused on the rise of false information online (HA, ANDREU PEREZ & RAY, 2021; TSFATI et al., 2020). [27]

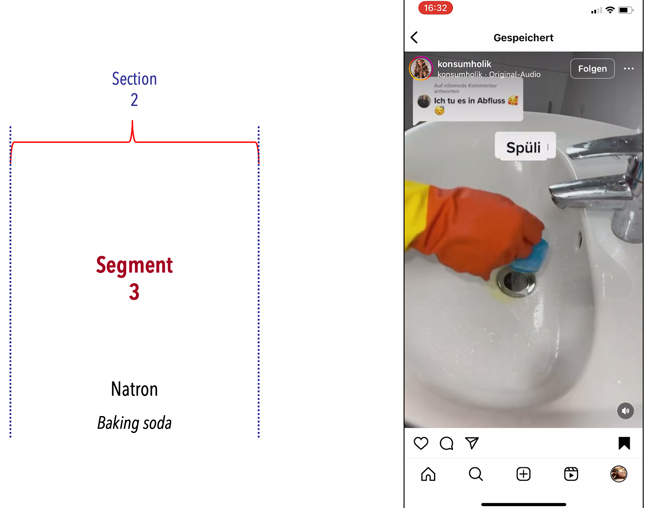

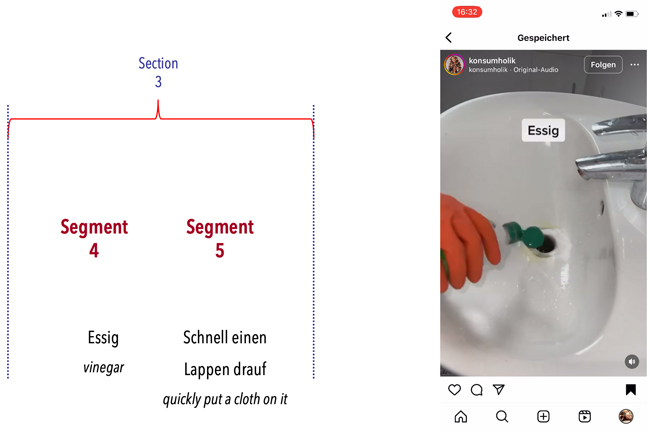

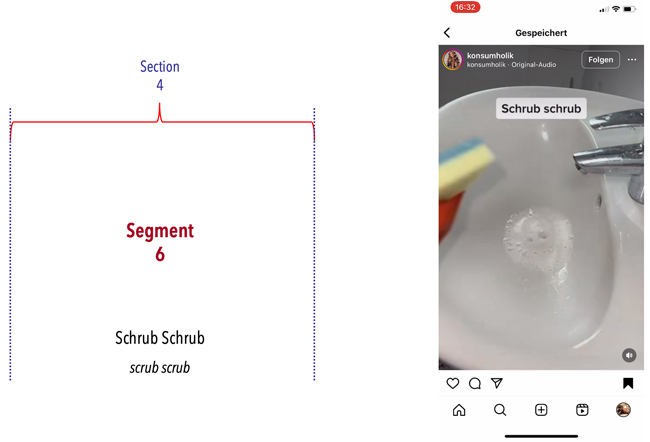

2.4 Instagram-clips as our research object

Instagram is a social media platform for sharing photos, videos, and stories. Unlike primarily text-based platforms such as Twitter and Facebook, Instagram is centered around visual content. Founded in 2010, the platform allows users to upload photos or videos. The content displayed on a user's Instagram feed is influenced by an algorithm that analyzes user behavior, including interests in specific topics, interactions such as likes and comments, frequency of use, and the number of followed accounts. Despite these insights, the exact functioning of the algorithm and the frequency of its adjustments remain unclear. [28]

In the current article, we focus on the spectrum of DIY videos on Instagram. Instagram's primary video format is reels which allows users to create and share short, creative videos. Various editing tools are available such as audio options from the Instagram music library, original audios, AR effects, timers, an align function for seamless transitions, and playback speed controls. After recording, users can edit their reels by adding titles, hashtags, and tags. The Explore section enables users to discover reels and interact with them through likes, comments, and shares. Featured reels are selected public reels highlighted by Instagram.8) [29]

The home page, known as the feed, displays posts based on recency and is influenced by both the algorithm and the accounts the user follows (BETTENDORF, 2020). Users can also search for specific topics or people. When a keyword is entered in the search bar, a list of suggestions appears. If the desired account is not found, the search can be expanded. In addition to personalized suggestions, which mostly consist of reels and video posts, users can filter by accounts, non-personalized accounts, audios, tags (hashtags), locations, and reels. [30]

Instagram structures social interaction through asynchronous networking, algorithmic control, and user-generated content (FERRARA, INTERDONATO & TAGARELLI 2014, pp.22ff.). The platform functions as a "mosaic of communication spaces" where different actors provide content for their respective audiences (ETIENNE & CHARTON, 2024, pp.4-7). Instagram effectively employs persuasive techniques to engage users, including its emphasis on visual content, interactive features, and evolving engagement tools, which collectively enhance user motivation and behavior (AMEER, NURULHUDA & HARRYIZMAN, 2023). [31]

Instagram's network structure follows the principle of "preferential attachment": Users with high levels of networking are more likely to gain new connections, leading to the formation of topical communities around shared interests (FERRARA et al., 2014, pp.27-29). A clear distinction exists between active content creators and passive consumers. Influencers act as communicative hubs, interacting with their followers in a largely asymmetrical manner: Influencers serve as content providers while followers primarily act as recipients (ETIENNE & CHARTON, 2024, pp.8ff.). They cultivate relationships with their audience by adopting roles such as "friend," "inspirational expert," or "community leader." Instagram's interface and features, such as tagging, Q&A tools, and personalized content, facilitate these interactions (RICHTER & YE, 2024). [32]

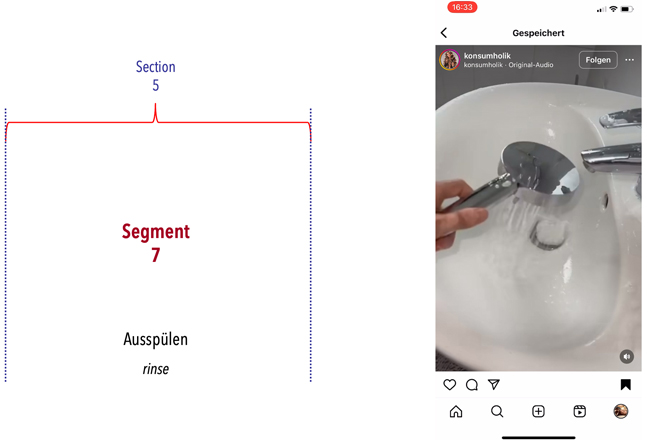

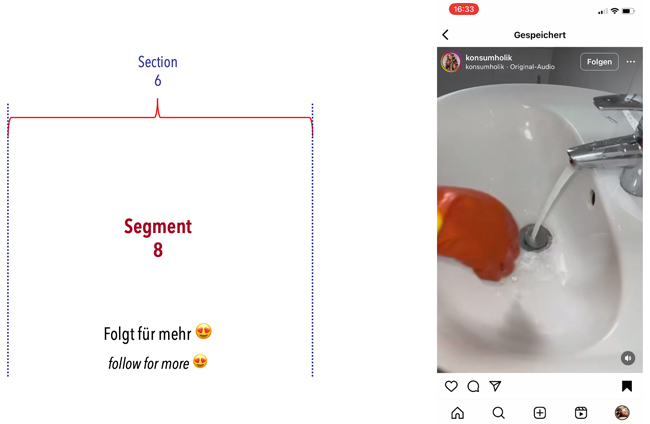

A central mechanism for structuring content on Instagram is social tagging. Hashtag distribution follows a power-law pattern, where a few popular tags dominate while the majority see limited use (FERRARA et al., 2014, pp.28-30). This reinforces algorithmic visibility dynamics and helps establish trends. Consequently, Instagram not only influences digital communication but also restructures social relationships. Algorithm-driven visibility, one-sided networking, and visual content create an interaction space where attention is a key resource (ETIENNE & CHARTON, 2024, pp.22ff.). [33]

LEAVER, HIGHFIELD and ABIDIN (2020) provided an extensive overview of Instagram's visual culture as shaped by its technical features as well as various economic, social and platform effects. The authors point out that Instagram's culture has shifted from being about unique artistic expression to a more standardized "template" of visual content. This includes popular aesthetic styles such as filters, curated feeds, and polished imagery that follow certain trends. The authors also observe offline effects in that Instagram's visual culture extends beyond the digital realm, influencing how physical spaces are designed. Restaurants, museums, and public places are increasingly being crafted to be "Insta-worthy," encouraging users to take and share aesthetically pleasing photos. [34]

Beyond increasing reach, Instagram offers monetization options such as sponsored posts and advertisements. This encourages strategic content optimization, often leveraging emotional engagement through humor, provocation, or, particularly, aesthetic visuals (ETIENNE & CHARTON, 2024, pp.19ff.). Instagram's culture has evolved from unique artistic expression to a more standardized template of visual content, characterized by popular aesthetic styles such as filters, curated feeds, and polished imagery that follow specific trends. While niche content creators can succeed within specialized communities, the most popular accounts typically feature a diverse range of topics (FERRARA et al., 2014, pp.32ff.). The platform thus balances community-driven self-organization with algorithmic popularity mechanisms, ultimately determining content visibility and reach. [35]

2.5 Research on knowledge communication via video clips in social media

Overall, research on clip-supported knowledge communication still has significant gaps, stemming from the volatility with which new clip forms emerge and disappear. This volatility makes it challenging to examine their impact on individual and social stocks of knowledge. [36]

Initial research on internet and social media clips focused on attempts at typologies (GEIMER, 2021) and methodological questions (TRAUE & SCHÜNZEL, 2021). Previous studies concentrated on specific youth- or subculture-related, as well as subjectification-related aspects of clip communication (REICHERT, 2012; TRAUE, 2013) or the role of social media as a means of visual biographical performance and biography work (BRECKNER & MAYER, 2023). Clips have been sporadically analyzed in health prevention (REINBOLD, 2023) or explainer videos (BROSZIEWSKI, GRENZ, LÖFFLER & PFADENHAUER, 2020). KADEN (2021) provided crucial insights into the societal effects of targeted meme campaigns. Recent research also considered new approaches to performative genres conveying religious (DIX, 2021) or scientific knowledge (HILL, 2022) and projective genres (AYASS, 2020). [37]

From a systematic perspective, three different contexts can be distinguished conceptually: 1. the context of the production or creation of the video clip, 2. the content of the clip itself and its intra-media context, and 3. the context of use or reception (see Section 2.1, §10). Empirically, production, content, and usage are closely intertwined. An early seminal example of research demonstrating this interconnectedness is the study on vernacular video creation by SÁNCHEZ SVENNSSON and TAP (2003). In their study, they revealed how nurses in an intensive care unit used self-produced short instructional video-clips tagged to the medical devices to teach each other how to use them properly. In the existing studies, researchers have engaged with social media content on various levels, without, however, consolidating these levels. In some studies, researchers have concentrated more on 1. the production level. In other studies, they have limited the inquiry to the media level and delved into analyses of 2. media content. In the analysis of social media content, DIY videos are part of multiple classification schemes. In this section, we provide an overview of various genre-based content classifications and discuss their strengths and weaknesses (FALTESEK et al., 2023). Finally, researchers in other studies have directed their attention to 3. the level of users and their interactions with content, as well as potential feedback loops arising from platform capabilities. [38]

GROSS and JORDAN (2023) presented various perspectives on the integration of machine learning (ML) into reality. The contributions reflected the dominant role of ML in artificial intelligence and emphasized the challenges for an adequate understanding of AI in social, humanistic, and philosophical contexts. Difficulties in grasping the meaning of data generated by ML were highlighted, as well as the ideological tendencies and societal problems that ML applications can reproduce. The emphasis was on theoretically challenging aspects of ML to create an expanded understanding and new perspectives in dealing with ML-based technology. [39]

Similarly, WOLF (2022) analyzed TikTok, highlighting that the platform not only served as a successful social media platform for video-based microformats but was increasingly used for informal learning. He examined the reception of various video formats on TikTok in the context of personal learning, with a particular emphasis on microformats in explainer videos compared to YouTube. TikTok was considered a microlearning platform that, despite challenges in structuring content, enables low-threshold and engaging learning for adolescents. [40]

Likewise, BUCHER, BOY and CHRIST (2022) addressed the role of platforms in knowledge dissemination with a focus on science communication via YouTube. The authors examined the interaction between media offerings and media reception, particularly in the context of YouTube videos as forms of science communication. The analysis of 400 selected videos resulted in a typology of science videos, illustrating the evolution of audio-visual formats under the conditions of the internet and digitization. BUCHER et al. emphasized the shift of science communication to internet platforms and identified new actors such as "science influencer" (p.215). They also underscored the increased importance of YouTube as an information source for scientific topics. The choice of video type, attention control, and the nature of the conveyed knowledge influence the effectiveness of audio-visual knowledge dissemination. Relevance to the topic, entertainment value, personalization, and video quality were identified as crucial factors for the impact of science videos. The authors highlighted the transformation of science communication through YouTube while concurrently mentioning challenges regarding evidence and dealing with misinformation. As new actors like "science influencers" were identified in his study, GRÜNWALD (2021) pointed out various occasions for communication in Instagram Stories. He emphasized that these stories not only serve communication about one's own body but also enable diverse communication opportunities on other topics. The microformat Instagram Stories is considered by him an experimental field for cultural negotiation processes, whether regarding one's own body or related to external references to current cultural and political developments. [41]

3. Data and Analytical Approach

The objective of our research is twofold: First, to typologically reconstruct relevant genre predecessors of clip-based knowledge visualization, and second, to create two contrasting corpora. The first corpus, designated "advice communication," is derived from freely available online clips that contain practical tips, tricks, and hacks for useful everyday knowledge. The second corpus, "specialized knowledge," will comprise clips that pertain to areas of expertise protected by higher access barriers and more extensive formal prerequisites. The ensuing discourse will focus exclusively on the former type. [42]

The present study employs a data sampling that adheres to the principles outlined in genre analysis (LUCKMANN, 1986) as a corpus-driven qualitative method. This involves the collection of a large number of typical instances, their transcription, identification, and the description of recurring structural features. However, our ongoing study does not restrict itself to an analysis of content only; it introduces two innovative elements: First, from a methodological perspective, examining knowledge communication clips offers a chance to test the combination of corpus and case analysis, as advocated in other works (SCHNETTLER, 2019). Second, we supplement the analysis of content with an exploration into the contexts of generation and use through focused ethnographies (KNOBLAUCH, 2005). In the current report of our ongoing study, we limit our discussion to a preliminary exploration of the content. Subsequent detailed, fine-grained data analyses will be tied back to questions regarding general sociological theory. [43]

This integrated approach is designed to address the distinctive challenges posed by the sheer volume, volatility, and rapid modulation of platform communication content. It can be regarded as an effort to establish new methodologies in qualitative research in domains significantly influenced by big-data- and AI-driven methodological advancements. [44]

In the following discussion, we focus on how the dissemination and acquisition of knowledge are altered by the extensive use of video clips. Such short audio-visual clips permeate our everyday communication. In many situations where people would have previously asked someone else for advice or consulted an encyclopedia, they now quickly search the internet (see "Georgina's law," Section 4.3, §62). It is noteworthy that there is a rapidly growing number of such video clips offering practical advice and useful knowledge. [45]

In our theoretical sampling, we confronted serious methodological challenges when attempting to compose a reasonable data corpus due to the heterogeneity, abundance, and strong dynamics of change inherent in the phenomenon under study:

The number of video clips used for knowledge dissemination is growing rapidly, posing a significant problem of data excess and selectivity.

While some identifiable sub-genres have already emerged (see Fig. 1), their appearance and disappearance are characterized by the same speed as the transformation and emergence of new derivatives and variations. The dynamics of the diversification/homogenization processes of knowledge itself are closely linked, but further exploration is needed.

As further challenges for empirical research, there is a need to consider both aspects of human action—in terms of practical media usage knowledge—and its combination with technical selection logics (algorithms). [46]

The platform-based dissemination through algorithmically shaped click logics involves user practices on the production and usage sides, bringing their own action competencies in dealing with the clips into play and thereby embedding them in a tension field of dehumanization or humanization dynamics.

Figure 1: Genre spectrum and methodological challenges of internet video clips [47]

At the current state of our ongoing research, we notice three preliminary observations:

Diversity of functions: Knowledge clips fulfill a wide range of functions, ranging from conveying information, self-presentation, and self-staging to targeted advertising, behavior influence, and propaganda9). A functional differentiation along these various communicative purposes and tasks that such clips fulfill is not easy to accomplish, as there are often mixtures and complicated overlays. Besides the enormous abundance and apparent ubiquity, this functional underspecification poses the greatest empirical challenges for a sociological analysis of clips as carriers of knowledge communication.

Diversity of forms: What could be described as video clips for knowledge dissemination also varies widely on the phenomenal level (see Fig. 1) and includes video tutorials, explanatory videos (such as those studied by BROSZIEWSKI et al., 2020), life hacks, etc., posted by "normal users." However, it also extends to semi-commercial videos like hauls, to instructions produced by companies or institutions (instructions for property tax), to online learning videos (at the other end of the spectrum), or episodes of Telekolleg reused on YouTube (whose content may even lead to formal educational certificates or diplomas).

Reflexive concept of knowledge: In a theoretical and systematic perspective, it should be noted that we adopt a very broad concept of knowledge. The perspective of the new sociology of knowledge (BERGER & LUCKMANN, 1966), is not substantial, but is sociologically reflexive: Knowledge is what is socially considered as knowledge, which is why we want to focus on the differentiation of various types of knowledge. Heuristically, a rough distinction can be made between a) everyday knowledge and b) specialized knowledge. [48]

From our growing research corpus, the following example is subjected to exemplifying fine-grained analysis. This analysis has a primarily exploratory character and is intended to generate further in-depth insights. In line with an iteratively cyclical research approach (STRÜBING, 2014, p.49), the understandings gained from these analyses will be corroborated and substantiated in subsequent research steps through a systematic expansion of case analyses. Ultimately, recursive structural aspects will be worked out in a further step. [49]

The following video clip, in terms of the specificity of the knowledge it conveys, is situated at the lower end of the complexity spectrum. We will inspect in detail this data fragment belonging to the category of useful everyday knowledge that originates from Instagram and is part of a reel focusing on cleaning tips and aid with organizing everyday activities.

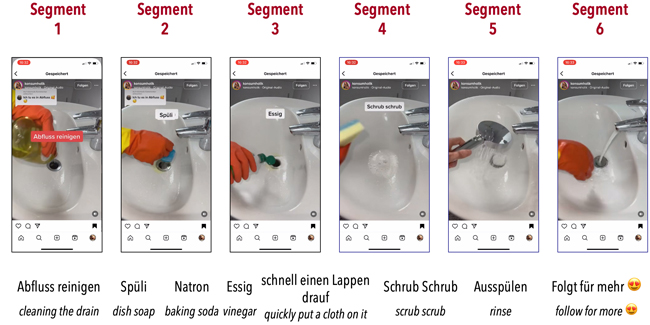

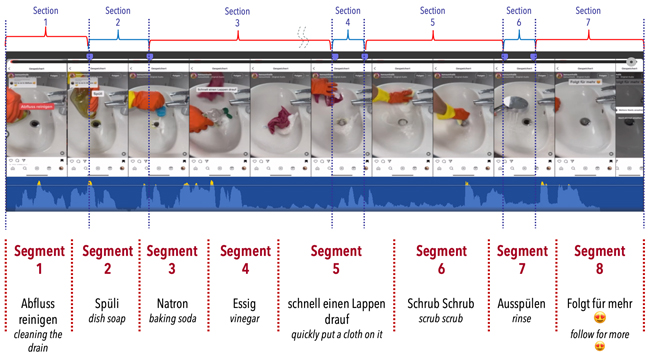

Figure 2: Segment structure of the investigated first research example schrubb-schrubb [scrub scrub] [50]

The 11-second vertical video starts immediately upon clicking, showing a close-up of a white sink. A drainage apparatus is situated approximately centrally within the confines of the frame, while components of a single-lever mixer are discernible in the upper right corner. The label Abfluss reinigen [cleaning the drain] is displayed in white letters on a red background in the center of the image. At the frame's upper-left corner, we can discern that the blogger with the name "Komsumholik," who counts 95,600 followers, has posted this content in response to a comment from "nilomed" with the sentence Ich tu es in Abfluss [I put it in the sink], accompanied by two smiley emojis. From the accompanying text, we learn that this is a repost. The original post came from TikTok and was posted by a user named "Arya.lifestylee," who supposedly has 300.7k followers and specializes in "Cleaning & Home," according to her profile description. Thus, the clip is part of a larger series. [51]

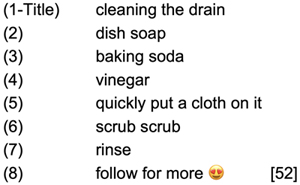

The clip displays the distinct characteristics of a recipe. Organized through the use of overlays and cuts, it is segmented into the following components:

In the video we observe, at an accelerated playback speed, a hand in a red household glove with a yellow shaft using various

cleaning agents to clean a sink. In the following discussion, we will thoroughly examine the clip's composition. Therefore,

we draw a conceptual distinction between sections and segments. Both unfold sequentially and are closely related but not identical: Sections represent components of film technique or aesthetics,

whereas segments refer to the elements of the cleaning action depicted in the clip.

Figure 3: Composition of sections and segments in the video clip under scrutiny. Please click https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15181929 to access the video. [53]

We observe that the clip is played at an accelerated velocity and is underlaid by instrumental music that is characterized by a cheerful and carefree timbre. In the following analysis, we will examine the sequential unfolding of the cleaning actions in closer detail: In the first segment, we see a bottle of common household dish soap positioned with its nozzle directed upside down towards the drain. Subsequently, a thin stream of the detergent is dispensed into the sink with vigorous circular motions. The overlay reading Abfluss reinigen [cleaning the drain], which functions as the title of the entire clip, disappears, and is replaced by the word Spüli [dish soap] as the textual label in this initial subsequence. Spüli is an abbreviation of the technical term Handgeschirrspülmittel [manual dishwashing detergent]. More precisely, it is a deonym, i.e., a genericized trademark, deriving from a brand name (similar to the German brand Tempo for tissues).

Figure 4: Section 1. Please click https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15181944 to access the video. [54]

The second segment opens with a hard cut. With an unchanged camera position, we see the hand that previously gripped the dish soap bottle, and whose individual fingers were visible in the upper-left corner, in a different arm position. The hand, now protruding from the left center into the frame, holds a small, bluish-transparent measuring cup, similar to the type used for measuring laundry detergents. The cup is filled with white powder, and with similar circular motions, the powder is poured into the drain.

Figure 5: Section 2. Please click https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15180267 to access the video. [55]

In the third segment, again separated by a hard cut, the previously fist-like gripping hand appears slightly lower, left-center in the frame, now holding an open bottle of vinegar essence. Its content is poured into the drain in circular motion, resulting in initial foaming in the drain. As the gloved right hand lifts the bottle, moving out of the frame to the left, the left hand, unprotected by a glove, extends into the frame. It retrieves a lilac-colored cloth or a crumpled mini towel and places it on the drain, covering it.

Figure 6: Section 3. Please click https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15181982 to access the video. [56]

In the fourth segment, also separated by a hard cut, neither one of the hands is visible in the frame. Instead, we observe white foam flowing out from the overflow and pouring over the cloth (actually, this segment is cut again at second 5, as evident from the foam, apparently serving the purpose of strong temporal compression). Another cut follows. The gloved hand is now visible in the upper-left corner of the frame, grasping the cloth and extracting it, along with some adhering foam, from the basin and the frame. [57]

In the fifth segment, the back of the hand is turned downward, and the hand, gripping a yellow scrub sponge reinforced with a blue scrubbing pad with three fingers, is presented to the camera with a functionally irrelevant hand rotation before being lowered toward the drain with a rapid hand movement, leading to quick cleaning movements throughout the basin. This is accompanied acoustically and with text overlays with the colloquial and onomatopoeic expression schrubb-schrubb [scrub scrub], reminiscent of popular refrains from well-known children's toothbrushing songs or humorous hand hygiene instructions. We observe that the clip is imbued with a humorous and infantilizing quality in this particular instance. Nevertheless, it must be noted that, in general, the content maintains a high degree of factuality and, most notably, is remarkably concise.

Figure 7: Section 4. Please click https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15181999 to access the video. [58]

The sixth segment is also initiated by a hard cut. The left hand, without a glove but holding a sprayer, enters the frame from the left, cleaning the sink and drain with running water. The sprayer is pulled out of the frame to the left. After another hard cut, we see the right hand with a glove retracting. A wide stream of water flows from the previously closed faucet, and the plug is in the drain, its slightly tilted position corrected by the hand before it swiftly rises to press the single-lever mixer, ending the water flow. The hand quickly withdraws, and the overlay Folgt für mehr [follow for more] appears, additionally verbalized.

Figure 8: Section 5. Please click https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15182007 to access the video. [59]

The last segment serves as a coda and comes equipped with the genre-typical seriality markers Folgt für mehr and the "smiling face with heart-eyes emoji," which apparently conveys the meaning of "overjoyed, in love, grateful, or admiring" and syntactically serves here as a conclusion. After 11 seconds, the entire clip finishes, when the system-generated buttons weitere Reels ansehen [view more reels] and Noch einmal ansehen [watch again] appear.

Figure 9: Section 6. Please click https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15182023 to access the video. [60]

In addition to the detailed, fine-grained sequential analysis previously outlined, two further observations regarding the simultaneous qualities depicted in this clip merit emphasis: First, it is quite evident that this is a clean sink, showing no dirt or blockages, clearly indicating the instructional or demonstrative nature of the video clip. Second, from a cinematographic perspective, the clip is distinguished by its notable audio-visual-text redundancies. The demonstration is performed visually, accompanied by succinct labels textually, the entire procedure being replicated verbally through voice-over. In essence, this constitutes a triplicated presentation of an information chain: Via video, text, and audio. [61]

4. Preliminary Conclusion and Desiderata for Follow-Up Research

At this juncture, it is premature to draw definitive conclusions which limits the extent to which the findings reported here can be generalized. However, the present study has identified several salient points that merit further inquiry. The analyzed example offers insights into potential genre-specific characteristics of clips used for the dissemination of informal knowledge which will be subjected to further scrutiny in subsequent research steps. Beyond the content focused on in this analysis, the contexts of creation and usage will also be examined. At this stage, three points can be noted:

The visualization devices and procedures that we have reported, as well as the observed redundancies, serve as a point of departure for further research. Undoubtedly, additional empirical research is needed to elucidate the role of video clips in the digital processes of social distribution and acquisition of knowledge.

The analyzed material raises questions related to semiotics, specifically addressing the limits of semiotization. While the videos' content can be analyzed linguistically, their contextual relevance as carriers of knowledge communication transcends the limits of verbalization/textualization. In the medium of video, the pre-significant or asemic becomes a meaningful vehicle of knowledge because the proverbial comprehensibility of the illustrated solution pathways enables reception that extends beyond that of verbalized recipe instructions. The audio-visual medium has the capacity to leverage the full range of visual stimuli, offering a multitude of avenues for processing knowledge. These avenues include repeated viewing, pausing, and cross-referencing with other knowledge sources in text, images, or conveyed by present members acting as third parties, or forms of shared reception. These modes of engagement facilitate novel forms of knowledge acquisition. The multimodality of the clip is a crucial source for an accessible acquisition of knowledge. In some cases, obstacles considered significant hurdles in the medium of textual communication are easily overcome. A prime example would be Turkish cooking instructions or Korean repair guides for inkjet printers. In both cases, the application of the demonstrated solutions by non-Turkish or non-Korean speakers can succeed, overcoming linguistic and cultural barriers. This addresses two desiderata for research: The question of the global transformation of social knowledge distributions and a focus on a problem in interpretative social research known as the overdetermination of the signifying.

Video clips contribute to the visualization of knowledge communication and promote what we want to be termed as "Georgina's law": The everyday notion that there is an answer on the net to anything one seeks to know.10) Video clips play a crucial role in establishing this everyday idea of universal accessibility to knowledge as a strong guiding fiction when it comes to retrieving knowledge resources. The internet and social media act as a universal library of problem-solving explanations where you can find, with a quick search and a few mouse clicks, illustrative and easily understandable teaching material to help with current issues. Questions of accessibility fade into the background in favor of user-centered efforts to search and sort through an overwhelming abundance of results. While hurdles such as knowledge behind paywalls or videos being too long or in languages one does not understand still exist, the first can be quickly skipped, and the latter is becoming increasingly mitigated by AI and automated translation. It can be assumed that such hurdles to knowledge dissemination and acquisition are generally being significantly reduced. [62]

Open questions remain that need to be explored through further research: 1. What influence does this fiction of unlimited, universal accessibility exert on the ways knowledge is acquired? 2. Are there specific knowledge domains that are favored by the described transformations while others fade into the background? 3. Does this process imply a change in the ways knowledge is socially derived (SCHUTZ & LUCKMANN, 1973)? How does it affect, for example, the relationship between experts and laypeople (or teacher-student relationships)? Do the boundaries shift between knowledge and non-knowledge, or knowledge that may be generally known and arcane knowledge that only a few possess? How does this change the legitimation and verification of knowledge resources? Who determines whether a particular piece of knowledge can claim validity? Are new testing and correction procedures being established? Could there even be a reversal in the production of knowledge, as analyzed by RAHMSTORF (2023) for Wikipedia ("first edit, then argue")? [63]

We are grateful to the anonymous reviewers and the FQS special issue editorial team for their constructive feedback on an earlier version of this text.

1) All translations from non-English texts are ours. <back>

2) The term communicative budget refers to "to the whole of the communicative dimension of social life [...] The communicative 'budget' of a society consists of different kinds of communicative processes, the difference being not only one of content but also one of form. Much of the 'budget' can only be estimated. It is loosely structured and contains 'spontaneous' communicative processes. But its most important part has the substantially more rigorous structure of a system. It consists of the field of communicative genres" (LUCKMANN, 1989, p.162). <back>

3) Synchronous forms of audio-visual distance communication, as conducted through Zoom, Skype, Google Meet, or other technologies, are not the primary focus here. In the period following the pandemic, it has become evident that digital video communication practices, which have been extensively promoted and widely established throughout society, exert an indirect influence on asynchronous forms of digital communication. This influence can be observed in the formation and consolidation of "ways of seeing" (RAAB, 2018, referring to BERGER, 1972), which also shape the production and interpretation of asynchronous visual communication. Furthermore, the analytical distinction between synchronous and asynchronous forms is not always empirically clear-cut. For instance, synchronous Zoom presentations can be recorded, stored, and accessed asynchronously, thereby transforming from one type to another. <back>

4) A growing body of evidence demonstrates an expanding reliance on visual and audio-visual methods for knowledge transfer in educational institutions (BAUER & STOECK, 2024). One of the earlier iterations of this genre is the German educational television series "Telekolleg," launched in 1965, which can be considered a precursor to today's flourishing forms of audio-visually supported knowledge transmission. Originally supported by the Bavarian Broadcasting Corporation and the Free State of Bavaria, "Telekolleg" operates as a specialized institution in the secondary education sector. As a state-recognized facility, it provides the curriculum for the vocational advancement school (Telekolleg I) or the technical college (Telekolleg II), allowing enrolled Telekolleg students to pursue part-time studies and take the vocational school or technical college entrance examination through the Zweiter Bildungsweg [Second Education Pathway] (SCHNETTLER, TUMA & SOLER SCHREIBER, 2010). Today, in formal learning contexts, massive open online courses (MOOCs), virtual classrooms, e-learning platforms, online tutorials, training videos, and podcasts are increasingly used for knowledge communication. Further distinctions can be made between instruments used in conjunction with other teaching and learning methods and those that function entirely independently. <back>

5) Conversational asymmetry is considered one of the constitutive conditions for communicating knowledge in face-to-face situations as demonstrated by LUCKMANN and KEPPLER (1991). For further insights into instruction, see also BROSZIEWSKI (2019). <back>

6) According to the terminology employed by KNOBLAUCH, "'digitization' is the transformation of analogous into digital characters; while the term 'digitalization' emphasizes the social use of digital data" (2020, p.242; our emphasis). <back>

7) In 2011, we established the doctoral program Kommunikative Konstruktion von Wissen [Communicative Construction of Knowledge] in Bayreuth in collaboration with Karin BIRKNER and colleagues from conversation analysis (BIRKNER, AUER, BAUER & KOTTHOFF, 2020), intercultural German studies, modern German literature, and media studies. It serves as an interdisciplinary workshop and is dedicated to a qualitative research approach that engages in theory-building from empirical research. Research projects that have emerged from this program included GROSS's (2018) analysis of doctor-patient conversations, SINGH's (2019) video study on knowledge communication in sports, REBSTEIN's (2019) videography of migration events, and DIX's (2021) genre analysis of sermons. <back>

8) https://about.instagram.com/blog/announcements/introducing-instagram-reels-announcement. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764219869402 [Accessed: March 12, 2025]. <back>

9) As evidenced by KADEN’s (2021) study on Russian meme propaganda, visual elements played a pivotal role in the realm of digital visual communication. <back>

10) Georgina was an elderly woman who resided in a small town in a rural region of Latin America. Born and raised in an era preceding her country's industrialization, she raised eight children in the most basic of conditions. Well into her eighties, nearly blind, but living in a different era, she continued to take a lively interest in the innovations of modernization, albeit indirectly. When asked by her children or grandchildren how to solve a particular problem, she would typically respond with the instruction ¡búscalo en internet! [Look it up on the internet!]. <back>

Ameer, Fathima Musfira; Nurulhuda, Ibrahim & Harryizman, Harun (2023). Exploring the persuasive design elements of instagram. Journal of Information and Technology Management (JISTM), 8(33), 297-319.

Ayaß, Ruth (2014). Media structures of the life-world. In Michael Staudigl & George Berguno (Eds.), Schutzian phenomenology and hermeneutic traditions (pp.93-110). Dordrecht: Springer.

Ayaß, Ruth (2020). Projektive Gattungen. Die kommunikative Verfertigung von Zukunft. In Beate Weidner, Katharina König, Wolfgang Imo & Lars Wegner (Eds.), Verfestigungen in der Interaktion. Konstruktionen, sequenzielle Muster, kommunikative Gattungen (pp.57-82). Berlin: De Gruyter.

Bauer, Angela & Stoeck, Janine (2024). Kinderleicht erklärt?! Die Adressierung von Kindern in krisenbezogenen Erklärvideos am Beispiel eines "Checker Tobi"-Videos. In Alexandra Flügel, Annika Gruhn, Irina Landrock, Jochen Lange, Barbara Müller-Naendrup, Jutta Wiesemann, Petra Büker & Astrid Rank Eds.), Grundschulforschung meets Kindheitsforschung reloaded (pp.311-321). Bad Heilbrunn: Julius Klinkhardt.

Berger, John (1972). Ways of seeing. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Berger, Peter L. & Luckmann, Thomas (1966). The social construction of reality. A treatise in the sociology of knowledge. Garden City, NY: Anchor.

Bettendorf, Selina (2020). Instagram-Journalismus für die Praxis. Ein Leitfaden für Journalismus und Öffentlichkeitsarbeit. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Birkner, Karin: Auer, Peter; Bauer, Angelika & Kotthoff, Helga (2020). Einführung in die Konversationsanalyse. Berlin: De Gruyter.

Breckner, Roswitha & Mayer, Elisabeth (2023). Social media as a means of visual biographical performance and biographical work. Current Sociology, 71(4), 661-682, https://doi.org/10.1177/00113921221132518 [Accessed: March 26, 2025].

Bridle, James (2018). New dark age. Technology, knowledge and the end of the future. London: Verso.

Brosziewski, Achim (2019). Belehrung. In Bernt Schnettler, René Tuma, Dirk vom Lehn, Boris Traue & Thomas Eberle (Eds.), Kleines Al(e)phabet des Kommunikativen Konstruktivismus. Fundus Omnium Communicativum (pp.57-62). Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Brosziewski, Achim; Grenz, Tilo; Löffler, Klara & Pfadenhauer, Michaela (2020). Erklärvideos. Ein wissenssoziologischer Zugang. IFS Working Papers, 1/2000, https://phaidra.univie.ac.at/detail/o:1101429 [Accessed: March 26, 2025].

Bucher, Hans-Jürgen; Boy, Bettina & Christ, Katharina (2022). Audiovisuelle Wissenschaftskommunikation auf YouTube. Eine Rezeptionsstudie zur Vermittlungsleistung von Wissenschaftsvideos. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Dix, Carolin (2021). Die christliche Predigt im 21. Jahrhundert. Multimodale Analysen einer kommunikativen Gattung. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Endreß, Martin (2017). Sicherheitsbedürfnis, Risikobereitschaft und Digitale Praxis. Ambivalente Vergesellschaftungstendenzen. In Gerhard Banse, Ulrich Busch & Michael Thomas (Eds.), Digitalisierung und Transformation. Industrie 4.0 und digitalisierte Gesellschaft (pp.37-46). Berlin: Trafo Wissenschaftsverlag.

Etienne, Hubert & Charton, François (2024). A mimetic approach to social Influence on Instagram. Philosophy and Technology, 37(2), 1-37.

Faltesek, Daniel; Graalum, Elizabeth; Breving, Bailey; Knudsen, ElseLucia; Lucas, Jessica; Young, Sierra & Varas Zambrano, Felix Eduardo (2023). TikTok as television. Social Media + Society, 9(3), https://doi.org/10.1177/20563051231194576 [Accessed: March 26, 2025].

Ferrara, Emilio; Interdonato, Roberto & Tagarelli, Andrea (2014). Online popularity and topical interests through the lens of Instagram. In Association for Computing Machinery (Ed.), HT 2014, Proceedings of the 25th ACM Conference on Hypertext and Social Media (pp.24-34). New York, NY: ACM.

Fink, Eugen (1970). Erziehungswissenschaft und Lebenslehre. Freiburg: Rombach.

Geimer, Alexander (2021). YouTube-Videos und ihre Genres. In Alexander Geimer, Carsten Heinze & Rainer Winter (Eds.), Handbuch Filmsoziologie (pp.1417-1430). Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Groß, Alexandra (2018). Arzt/Patient-Gespräche in der HIV-Ambulanz. Facetten einer chronischen Gesprächsbeziehung. Göttingen: Verlag für Gesprächsforschung, http://www.verlag-gespraechsforschung.de/2018/pdf/ambulanz.pdf [Accessed: March 27, 2025].

Groß, Richard & Jordan, Rita (Eds.) (2023). KI-Realitäten. Modelle, Praktiken und Topologien maschinellen Lernens. Bielefeld: transcript, https://doi.org/10.1515/9783839466605 [Accessed: March 26, 2025].

Grünwald, Jan (2021). Instagram-Stories als Bildverstärker und Kommunikationsanlass. In Peter Moormann, Manuel Zahn, Patrick Bettinger, Sandra Hofhues, Helmke Jan Keden & Kai Kaspar (Eds.), Mikroformate. Interdisziplinäre Perspektiven auf aktuelle Phänomene in digitalen Medienkulturen. München: kopaed.

Günthner, Susanne & Knoblauch, Hubert (1995). Culturally patterned speaking practices: The analysis of communicative genres. Pragmatics, 5(1), 1-32, https://doi.org/10.1075/prag.5.1.03gun [Accessed: March 26, 2025].

Ha, Louisa; Andreu Perez, Loarre & Ray, Rik (2021). Mapping recent development in scholarship on fake news and misinformation, 2008 to 2017: Disciplinary contribution, topics, and impact. American Behavioral Scientist, 65(2), 290-315.

Hill, Miira (2022). The new art of old public science communication. Milton Park: Routledge.

Kaden, Tom (2021). Autoritative Macht und politische Einflussnahme. In Peter Gostmann & Peter Ulrich Merz-Benz (Eds.), Macht und Herrschaft. Zur Revision zweier soziologischer Grundbegriffen (pp.107-131). Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Klemm, Matthias & Staples, Ronald (Eds.) (2018). Leib und Netz. Sozialität zwischen Verkörperung und Virtualisierung. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Knoblauch, Hubert (1995). Kommunikationskultur: Die kommunikative Konstruktion kultureller Kontexte. Berlin: De Gruyter.

Knoblauch, Hubert (2005). Focused ethnography. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 6(3), Art. 44, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-6.3.20 [Accessed: March 26, 2025].

Knoblauch, Hubert (2020). The communicative construction of reality. Milton Park: Routledge.

Knoblauch, Hubert & Schnettler, Bernt (2010). Sozialwissenschaftliche Gattungsforschung. In Rüdiger Zymner (Ed.), Handbuch Gattungstheorie (pp.291-294). Stuttgart: J.B. Metzler.

Knoblauch, Hubert & Singh, Ajit (Eds.) (2023). Kommunikative Gattungen und Events. Zur empirischen Analyse realweltlicher sozialer Situationen in der Kommunikationsgesellschaft. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Lanier, Jaron (2013). Who owns the future?. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster.

Leaver, Tama; Highfield, Tim & Abidin, Crystal (2020). Instagram: Visual social media cultures. Cambridge: Polity.

Lucht, Petra; Schmidt, Lisa-Marian & Tuma, René (Eds.) (2013). Visuelles Wissen und Bilder des Sozialen. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Luckmann, Thomas (1984). Von der unmittelbaren zur mittelbaren Kommunikation (strukturelle Bedingungen). In Tasso Borbé (Ed.), Mikroelektronik. Die Folgen für die zwischenmenschliche Kommunikation (pp.75-84). Berlin: Colloquium.

Luckmann, Thomas (1986). Grundformen der gesellschaftlichen Vermittlung des Wissens: Kommunikative Gattungen. In Friedhelm Neidhardt, M. Rainer Lepsius & Johannes Weiß (Eds.), Kultur und Gesellschaft (pp.191-211) Opladen: Westdeutscher Verlag.

Luckmann, Thomas (1988). Kommunikative Gattungen im kommunikativen "Haushalt" einer Gesellschaft. In Gisela Smolka Koerdt, Peter M. Spangenberg & Dagmar Tillmann-Bartylla (Eds.), Der Ursprung von Literatur. Medien, Rollen, Kommunikationssituationen zwischen 1450 und 1650 (pp.279-288). München: Fink.

Luckmann, Thomas (1989). Prolegomena to a social theory of communicative genres. Slovene Studies, 11(1-2), 159-166, https://doi.org/10.7152/ssj.v11i1.3778 [Accessed: March 26, 2025].

Luckmann, Thomas (2002). Der kommunikative Aufbau der sozialen Welt und die Sozialwissenschaften. In Thomas Luckmann (Author), Hubert Knoblauch, Jürgen Raab & Bernt Schnettler (Eds.), Wissen und Gesellschaft. Ausgewählte Aufsätze 1981-2002 (pp.157-181). Konstanz: UVK

Luckmann, Thomas & Keppler, Angela (1991). "Teaching". Conversational transmission of knowledge. In Ivana Markova & Klaus Foppa (Eds.), Asymmetries in dialogue (pp.143-165). Hertfordshire: Harvester Wheatsheaf.

Marres, Noortje (2017). Digital sociology. The reinvention of social research. Hoboken: Wiley.

Mélix, Sophie & Christmann, Gabriela B. (2022). Rendering affective atmospheres: The visual construction of spatial knowledge about urban development projects. Urban Planning, 7(3), 299-310, https://doi.org/10.17645/up.v7i3.5287 [Accessed: March 26, 2025].

Meyer, Christian & Quasinowski, Benjamin (2022). Conversational organization and genre. In Svenja Völkel & Nico Nassenstein (Eds.), Approaches to language and culture (pp.125-155). Berlin: Mouton De Gruyter.

Müller, Michael R. & Soeffner, Hans-Georg (Eds.) (2018). Das Bild als soziologisches Problem. Herausforderungen einer Theorie visueller Sozialkommunikation. Weinheim: Beltz Juventa.

Nassehi, Armin (2024). Patterns. Theory of the digital society. Berlin: Wiley.

Neuberger, Christoph; Bartsch, Anne; Fröhlich, Romy; Hanitzsch, Thomas, Reinemann; Carsten & Johanna Schindler (2023). The digital transformation of knowledge order: A model for the analysis of the epistemic crisis. Annals of the International Communication Association, 47(2), 180-201, https://doi.org/10.1080/23808985.2023.2169950 [Accessed: March 26, 2025].

Peltzer, Anja (2021). Filmische Wahrheit und soziologische Methode. In Oliver Dimbath & Carsten Heinze (Eds.), Methoden der Filmsoziologie (pp.179-208). Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Raab, Jürgen (2008). Visuelle Wissenssoziologie. Konstanz: UVK.

Raab, Jürgen (2018). Sehweisen. Zur sozialwissenschaftlichen Interpretation räumlicher Sinnkonstitutionen in der visuellen Kommunikation. In Martin Endreß & Alois Hahn (Eds), Lebenswelttheorie und Gesellschaftsanalyse: Studien zum Werk von Thomas Luckmann (pp.76-98). Köln: Herbert von Halem.

Raab, Jürgen (2023). Good pictures—Bad pictures: Image ethics of moral collectives. In Stefan Joller & Marija Stanisavljevic (Eds.), Moral collectives. Theoretical foundations and empirical unsights (pp.183-20). Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Rahmstorf, Olaf (2023). Wikipedia: Die rationale Seite der Digitalisierung. Entwurf einer Theorie. Bielefeld: Transcript, https://doi.org/10.1515/9783839458624 [Accessed: March 26, 2025].

Rebstein, Bernd (2019). Das fremdkulturelle Vermittlungsmilieu. Ein videographischer Beitrag zur Soziologie sozialer Welten. Weinheim: Beltz Juventa.

Reichert, Ramon (2012). Make-up-Tutorials auf YouTube. Zur Subjektkonstitution in Sozialen Medien. In Pablo Abend, Tobias Haupts & Claudia Müller (Eds.), Medialität der Nähe. Situationen – Praktiken – Diskurse (pp.103-118). Bielefeld: transcript.

Reinbold, Judith (2023). Persuasive Mittel in Corona-Präventionsvideos. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Richter, Vanessa & Ye, Zhen (2024). Influencers' Instagram imaginaries as a global phenomenon: Negotiating precarious interdependencies on followers, the platform environment, and commercial expectations. Convergence, 30(1), 642-658, https://doi.org/10.1177/13548565231178918 [Accessed: March 26, 2025].

Sánchez Svensson, Marcus & Tap, Hans (2003). Alarms. Localization, orientation, and recognition. International Journal of Human-Computer-Interaction, 15(1), 51-66.

Schnettler, Bernt (2007). Auf dem Weg zu einer Soziologie visuellen Wissens. Sozialer Sinn, 8, 189-210.

Schnettler, Bernt (2017). Digitale Alltagsfotografie und visuelles Wissen. In Thomas S. Eberle (Ed.), Fotografie und Gesellschaft. Phänomenologische und wissenssoziologische Perspektiven (pp.241-255). Bielefeld: transcript.

Schnettler, Bernt (2019). Die konträren Logiken von Korpus und Fall: Plädoyer für eine Integration. In Ronald Hitzler, Jo Reichertz & Norbert Schröer (Eds.), Kritik der Hermeneutischen Wissenssoziologie (pp.126-135). Weinheim: Beltz Juventa.

Schnettler, Bernt & Bauernschmidt, Stefan (2019). Bilder in Bewegung. In Michael Müller & Hans-Georg Soeffner (Eds.), Das Bild als soziologisches Problem (pp.197-208). Weinheim: Beltz Juventa.

Schnettler, Bernt & Knoblauch, Hubert (Eds.) (2007). Powerpoint-Präsentationen. Konstanz: UVK.

Schnettler, Bernt; Tuma, René & Soler Schreiber, Sebastian (2010): Präsentation – Demonstration – Rezeption: Visualisierung der Wissenskommunikation. In Hans-Georg Soeffner (Ed.), Unsichere Zeiten. Herausforderungen gesellschaftlicher Transformationen. Verhandlungen des 34. Kongresses der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Soziologie in Jena 2008 [CD-Rom]. Wiesbaden: VS.

Schnettler, Bernt; Sánchez Salcedo, José Fernando; Dießelmann, Anna-Lena & Hetzer, Andreas (2021). Kampf der Bilder für den Frieden? Evidenzherstellung und visuelle Rhetorik in Kolumbien vor und nach der Demobilisierung der FARC. In Oliver Dimbath & Michaela Pfadenhauer (Eds.), Gewissheit. Beiträge und Debatten zum 3. Sektionskongress der Wissenssoziologie (pp.831-844). Weinheim: Beltz Juventa,

Schutz, Alfred & Luckmann, Thomas (1973). The structures of the life-world. Evanston: Northwestern University Press.

Seyfert, Robert (2024). Die Theorie algorithmischer Sozialität (TaS). Österreichische Zeitschrift für Soziologie, 49(1), 23-46, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11614-023-00535-1 [Accessed: March 26, 2025].

Singh, Ajit (2019). Wissenskommunikation im Sport. Zur kommunikativen Konstruktion von Körperwissen im Nachwuchstraining. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Singh, Ajit & Christmann, Gabriela B. (2020). Citizen participation in digitised environments in Berlin: Visualising spatial knowledge in urban planning. Urban Planning, 5(2), 71-83, https://doi.org/10.17645/up.v5i2.3030 [Accessed: March 26, 2025].

Soeffner, Hans-Georg (2004). Auslegung des Alltags – Der Alltag der Auslegung. Zur wissenschaftlichen Konzeption einer sozialwissenschaftlichen Hermeneutik. Stuttgart: UTB.

Srubar, Ilja (2017). Typus, Zeichen und Bildpräsenz. In Thomas Eberle (Ed.), Fotografie und Gesellschaft. Phänomenologische und wissenssoziologische Perspektiven (pp.411-423). Bielefeld: transcript.

Strübing, Jörg (2014). Grounded Theory. Zur sozialtheoretischen und epistemologischen Fundierung eines pragmatistischen Forschungsstils. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Traue, Boris (2013). Bauformen audiovisueller Selbst-Diskurse. In Petra Lucht, Lisa-Marian Schmidt & René Tuma (Eds.), Visuelles Wissen und Bilder des Sozialen. Aktuelle Entwicklungen in der Soziologie des Visuellen (pp.281-301). Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Traue, Boris & Schünzel, Anja (2021). YouTube und andere Webvideos. In Alexander Geimer, Carsten Heinze & Rainer Winter (Eds.), Handbuch Filmsoziologie (pp.1363-1375). Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Tsfati, Yariv; Boomgaarden, Hajo G.; Strömbäck, Jasper; Vliegenthart, Rens; Damstra, Alyt & Lindgren, Elina (2020). Causes and consequences of mainstream media dissemination of fake news. Literature review and synthesis. Annals of the International Communication Association, 44(2), 157-173, https://doi.org/10.1080/23808985.2020.1759443 [Accessed: March 26, 2025].

Weber-Spanknebel, Martin (2023). Das Teilen der Welt. Sozialität unter Bedingungen von Technik und Digitalität. In Marc Fabian Buck & Miguel Zulaica y Mugica (Eds.), Digitalisierte Lebenswelten. Bildungstheoretische Reflexionen (pp.107-127). Berlin: J.B. Metzler.

Wilke, René (2022). Wissenschaft kommuniziert. Eine wissenssoziologische Gattungsanalyse des akademischen Group-Talks am Beispiel der Computational Neuroscience. Wiesbaden: Springer VS